Abstract

Eco-cities have become global initiatives in recent years. This paper aims to discuss the construction, evolution and future of eco-city movements in China, especially in areas with abundant ecological resources. Extant literature emphasizes that sustainable development is the purpose of an eco-city. However, in the spatial practice of ecological modernization, many European and American countries develop ecological construction at a slower pace, resulting in sustainable ecological outcomes. Those countries developed ecological practices at a smaller scale, aiming to achieve green towns with zero carbon emission. In contrast, the construction of China’s eco-cities typically involves building new cities in outer suburbs with a larger scale and faster speed. This has led to the rapid construction of so-called ecological cities without sustainable development. In this context, this paper starts from the perspective of political economy and conducts qualitative research on the Shanghai Dongtan Eco-city as a case study. It analyzes the motivation and practical measures of different actors by examining the planning, design and construction process of Dongtan Eco-city during 1998–2024. The results suggest that gaining national political priority through the intervention of international actors and foreign investment is the key to the local pilot ecological city project. This paper further analyzes the differences between the planning concept and the actual practice of Dongtan Eco-city, critically discussing the “Eco-city as the enclave of ecological technology.” This is driven by the integration of eco-city construction and the local government performance appraisal system. Consequently, the pursuit of economic returns redirected Dongtan’s sustainability experiment into a form of green-branded retirement real-estate development between 1998 and 2012. From 2012 to 2024, Chongming’s development model continued to evolve, as the project was reframed from a real-estate-led eco-city paradigm toward an “ecological island” agenda articulated in the language of sustainable development.

1. Introduction

In the 21st century, environmental issues have become the focus of global attention. Faced with environmental pressures, most of countries and regions are seeking “best practices” in urban development to alleviate environmental crises. In this context, the contradictions caused by China’s rising economic power and its responsibility for climate change are becoming increasingly prominent. Consequently, ecological modernization and eco-city movements in China came into being and were widely discussed [1,2,3,4,5]. Since then, more than 300 eco-city projects aiming for sustainability and green environments have been initiated [6].

However, there is still a gap between vision and reality in the practice of eco-city construction. On one hand, China’s environmental problems have not eased and have even worsened through many spatial experiments for the purpose of eco-modernization in the past decade. In particular, air pollution, water pollution and waste pollution have brought increasing hazards to the public’s daily life. Although temporary compulsory improvement measures (such as Beijing “APEC Blue,” etc.) have been implemented, it is undeniable that the effect of alleviating the environmental crises was limited.

On the other hand, in the enterprise storytelling of realizing rapid urbanization and enhancing competition, the eco-city has become a local urban space development and governance strategy. This is because an eco-city, designed for alleviating environmental pollution according to the high standards suggested by foreign consultants, serves as an effective slogan and measure. It can not only promote GDP and investment but also attract high-income and highly educated middle-class groups [1,4,5]. Yet, the more practical issues of the “eco-city upsurge” are at the forefront, that is, the land price and housing price of eco-cities are rising, and excessive Chinese real estate construction has led to the coexistence of “prime land” and “ghost towns” [7,8].

Given the fact that there is no acknowledged case of “best practices” in eco-cities around the world so far, although there have been many ecological pilot initiatives, such as Masdar Solar City in Abu Dhabi (known for being self-sufficient in renewable energy), New Songdo City in Korea (known as a leading smart city), and more than 200 eco-cities with the declaration for sustainable ecology but driven by land finances, examples in China include Shanghai Science and Technology City, Wuxi Zhongrui Eco-city, Sino-French Wuhan Eco-city and Shenzhen International Low Carbon City [3,9,10,11,12].

Large-scale construction of eco-cities in China has been rapidly promoted with the slogan “to alleviate the environmental crisis.” Moreover, the Chinese government has never offered a precise definition or a binding urban planning standard for eco-cities. Within the process of constructing eco-cities, we often see several “happy actors,” such as the central government, local government, foreign consultants, foreign clean technology companies, and the middle class, even if the eco-cities eventually fail.

Therefore, it is necessary to answer the following questions: For whom were eco-cities built? How were they built? Moreover, can an envisioned eco-city be a space designed under discourses? If so, why is there no successful eco-city in China? Additionally, to alleviate the environmental crisis caused by rapid urbanization, it is urgent for China to mitigate or solve its ecological problems. However, the space development led by the local government through top-down planning strategies, as corporate storytelling, eventually led to large-scale eco-city constructions. On one hand, such large-scale construction that is intended to solve the crisis has led to a greater crisis; on the other hand, the “eco-city” turns out to be an ecological scam and a game of capital accumulation.

Based on this view, from the perspective of “Post-Planning Assessment” and “Technology City,” this research critically comments on the Shanghai Dongtan Eco-City, a local ecological practice that first gained international reputation but failed to be implemented in reality, and asks the questions mentioned above. Furthermore, a series of case studies on eco-cities show that the mainstream ecological development in China is combined with the values of ecological modernization, and the goal of economic growth is promoted first, while environmental and social equity issues are largely ignored [3,10,13,14].

From the perspective of political economy and Actor-Network Theory (ANT), this paper analyzes the case of Shanghai Dongtan Eco-city, whose planning started in 2003. This paper further sorts out the actor relationship and examines the operational mechanism of space development in China.

This paper is organized as follows: Section 2 reviews the relevant literature on ecological modernization and green urbanism under the current environmental crisis, planning discourse power movement and eco-city practice, the circuit of capital theory, and the technology city; Section 3 summarizes the human geography and construction process of the Shanghai Dongtan Eco-city and the introduction of the Shanghai Dongtan Eco-city planning text; Section 4 analyzes the actor relationship in the Dongtan Eco-city project and conducts a controversial review; Section 5 and Section 6 discusses the construction process and takes the “Eco-city for whom” as the central axis to critically reflect on China’s eco-city construction; and Section 7 offers conclusions.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Ecological Modernization and Ecological Urbanism

Under the crisis of climate change and oil depletion, many countries around the world have implemented experimental projects to achieve a low-carbon economy1 (e.g., Masdar in Abu Dhabi, the smart city of Songdo in South Korea, the Sino-Dutch Shenzhen low-carbon eco-city, and the Sino-Singapore Tianjin eco-city) [7,13,15,16]. In this context, green urbanism, green liberalism, and market environmentalism have emerged. In 2008, Obama launched a green economy strategy and green stimulus plan, which further led to an increase in the ecological modernization of urban space experiments, including the development of technologies adapted to climate change, the transformation of the built environment, or economic reform towards a low-carbon economy [7].

In terms of eco-city construction, in 1972, the United Nations Conference on the Human Environment published a declaration on the human environment, which mentioned that human settlement and urbanization should be planned. Some public eco-environment organizations have emerged to explore the concept and meaning of eco-cities. For example, the urban eco-organization initiated by Rebuild cities in balance with nature (1987) and Ecocity Berkeley: Building Cities for a Healthy Future (2006) aim to recreate the city based on the principle that “the smaller urban planning, the higher the urban quality of life”. These initiatives advocate for the coexistence of nature and environment, promoting modes of walking, cycling and mass transit for the general public [17,18].

In the 1990s, Our Common Future officially proposed sustainable development theory and a development model. In 1992, Agenda 21 proposed to focus on ecological and sustainable development. In 1997, the Kyoto Protocol proposed to control carbon emissions [19]. In the 1980s, the concept of eco-city construction was introduced to China; it was rapidly developed and practiced, with as many as 200 eco-city construction projects across China. However, it is regrettable that China’s eco-city theory construction and planning system is still in its infancy, with repetitive construction and numerous problems [1,14,20].

Emerging economies were considered to be the new culprit in the man-made environmental crisis, and China’s rapid urbanization has led to severe damage to the natural environment. Eco-city best practices were seen as solutions to climate change, and ecologically conceptualized cities were used as an experiment to solve environmental crises, connecting cities directly to the crisis, and then planning new urban areas as test sites for resolution to specific crises [7]. Existing implemented projects outside China are commonly discussed in two types. First are greenfield, master-planned eco-city new towns (e.g., Masdar, Songdo), typically characterized by large-scale infrastructure packages, technology-led narratives, and strong state–corporate involvement. These projects are often evaluated through the lens of promised versus delivered sustainability performance, where scholars note tensions between technological demonstration, real-estate logics, and everyday socio-spatial life. Second are incremental eco-districts and urban retrofits, which tend to pursue sustainability through policy instruments, public transport, building standards, and socio-technical transitions embedded in existing urban fabrics. Across both clusters, the literature emphasizes that “implementation” should be treated as a long-run political-economic process (rather than a one-off planning moment), in which eco-city visions are translated into selectively built infrastructure, governance routines, and marketable place-branding strategies [6,10,11].

From the perspective of political ecology, the development of an eco-city is not done through an authoritarian government that imposes the concept of “do not waste” on enterprises or citizens; instead, it is achieved by enhancing the grassroots accumulation of civic awareness and civil society through active deliberative participation. However, eco-city practices in emerging economies have led to higher energy consumption, more cars and roads, and even green-grabbing (encroachment on farmland and ecologically sensitive areas). An ideal eco-city does not seem to exist [21,22,23].

2.2. Discourses Flow and Capital Accumulation in China’s Eco-Cities

Pow and Neo pointed out that the assemblage of a host of mobile policy networks and “quick-fix” urban policy solutions construct a world of fast policy transfer [9]. In this process, international planners, city consultants, and activists all play essential roles in policy and knowledge flows. For example, the narratives of “good livable eco-cities” and “good cities in Asian,” along with international competitiveness rankings, show that such “best practices” city rankings that resemble industry standards have gradually become the goal pursued by the ruling elites. At the same time, a city is no longer independent but is influenced by other places [24]; in the context of ecological modernization, the formulation of environmental policy becomes the free discourse of this relationship.

Moreover, the spread of planning policy discourse is not mere technical dissemination, but also involves transfer, interpretation, and adaptation. The elites of planners who spread their planning ideas have a particular impact on large-scale urban projects in major cities. Rapid urbanization economies, such as China and India, have a strong desire for modernization and development, leading to transnational urban sustainability practices; planning expertise loops between home and other countries [3]. More details on China’s practice are revealed, in order to compare with other cities (e.g., eco-city, livable cities, city best practices, etc.), and to show and market the city on the global stage, where many cities gradually absorb the policies of eco-cities. At the same time, because the discourse on the best practices of an eco-city is in the international planning consultancy stage, the invitation or their direct entry into China’s eco-city planning practice is the result of the global market economy. In addition, the Chinese government and international planning and design agencies were trying to embed themselves in global networks through the construction of eco-cities, gaining opportunities to showcase their achievements on the international stage, and stimulating investment.

The circuit of capital theory, including the primary, secondary, and the tertiary circuit of capital, suggests that capital accumulation stems from productive factors. Because of the excessive accumulation of investment in the urban built environment, investors have turned into social investors that are focused on education and health benefits. In terms of China’s reforms and opening up, the government has promoted the construction of various factories, earning a large amount of foreign exchange and realizing capital accumulation. However, during the outbreak of the economic crisis in 2008, the promulgation of the Chinese government’s 4 trillion yuan stimulating fiscal policy made China miss the opportunity in industrial shift to third-world countries and to adjust its industry [25,26].

So far, the emergence of China’s university towns, development zones, sustainable cities, smart cities, and eco-cities [27,28,29,30], was the reality that the primary and secondary circuits of capital and infrastructure construction were simultaneous. Through development and urbanization under government directives, the development of industrialization is promoted, which will stimulate employment and GDP growth. This process even appeared as the tertiary circuit of capital, for example, land financialization.

However, in the process of infrastructure construction, government capital liabilities were increasing. According to the China Government Investment and Investment Platform Annual Report 2015, the Chinese government’s debt from local government financing platforms in 2009 increased from 5.26 trillion yuan to 24 trillion yuan in 2015, accounting for 35.1% of the GDP in 2014. Moreover, because debt in many places is hidden, in some areas, the local debt is two to three times the size of government statistics [31].

In this context, the local government further pushed the primary and secondary circuits of capital to a larger scale, from building infrastructure to building cities, such as the dramatic growth of eco-city projects, in order to stimulate production materials through the construction of new cities, and increase capital accumulation in the primary circuits of capital. The construction of a city could drive the infrastructure of the new city itself and between the cities, promote the secondary circuits of capital, and shape the capital urbanization and even land financialization (the tertiary circuit of capital).

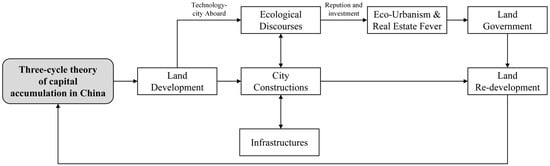

The six steps are shown in Figure 1. The first step is for local governments to increase land prices through land development; the second step is to raise the discourse through foreign consulting companies and attract foreign investment and domestic political priorities; the third step is to carry out secondary development of land (real estate development) through specific marketing strategies, such as eco-branded green real estate, smart city, etc.; in the fourth step, local governments profit from land finance; and in the fifth and sixth steps, the second wave of land development and land redevelopment are carried out. In this process, the capital accumulation of the first loop is based on unsustainable land development, especially the fourth step. The real estate-oriented development strategy, whether finding solutions for ghost towns or successfully attracting the middle class, is the key to the continued operation of the development logic.

Figure 1.

Development logic of China’s urban construction. Source: drawn by the authors.

Although many urban construction projects in recent years have eventually become ghost towns, since local governments will rarely go bankrupt, the same real estate development logics are still adopted by the local governments. There are several reasons behind this phenomenon. First, after the tax-sharing system was implemented in 1994, the financial power became concentrated in the central government, and the power of affairs was decomposed downwards. Without sufficient funding but facing rigid demands (for development), many local governments are expanding their debts. Second, soft budget constraints have led to further expansion of debt, that is, local financing platform companies shoulder economic responsibility, government responsibility, and responsibility for public asset investment construction. Local financial platforms can be insured by local governments, but the central government bears no responsibility for providing a financial safety net for local governments. Third, the local government’s debt operation is irrelevant to the performance evaluation and income of local officials. Moreover, the frequent promotion and transfer of government officials and debts do not undermine the officials; instead, they make the debt repayment obligations the responsibility of the next government officials [32].

2.3. Eco-City as a Technology City for Urban Technology

The environmental crisis brought about by climate change has prompted the discussion on the benefits of ecological modernization and clean technology-guided technological fixes in regard to green capitalism and eco-urbanism. However, as a strategy of ecological modernization and urban green governance, the eco-city has become a part of China’s spatial fix under the relationship flow of policy discourse. Combined with the circuit of capital theory, it is not a continuous process.

Technology is part of a contemporary eco-city initiative that typically uses a variety of green socio-technical solutions designed to reduce environmental impact and transform cities into low-carbon cities. It envisages various intelligent technology systems (e.g., smart grids, digital communication technologies) to construct modern eco-cities, as well as the control and sensing of the operation of eco-cities, from urban infrastructure (energy distribution, garbage collection, integrated transportation systems) to public life (public services, information management).

However, the role of socio-technical systems and solutions in eco-city initiatives in terms of ideas, concepts, and practices remains low. Based on spatial fixes on new city construction [33], Caprotti proposed a “technical fix,” that is, the discourse on the transition to green capitalism and the assemblage of public demand to adapt to climate change [7]. However, in a study on the interaction between technology and the planned urban environment, technology cities are planned and developed in conjunction with large-scale technology and industrial projects [34]. Their development can be traced back to the garden city of the 19th century, the interwar initiatives of the new deal, the modernist cities of the Cold War, and postmodernism that emphasizes the use of coordinated technology and community concepts.

Joss and Molella further proposed urban technology as an analytical perspective, which regards the eco-city as a manifestation of the perpetual practice of the 21st century city, which is shaped by the dual challenges of global climate change and rapid urbanization [35]. And the global eco-city phenomenon is based on the unique characteristics of the new city and advanced green technology [35]. The planning and construction of Caofeidian Eco-city and Tianjin Eco-City in China are based on technical methods and define the essence of an eco-city with critical clean technology applications. Taking the method of Science and Technology Studies (STS) and analyzing it from the perspective of the technology city is conducive to identifying various forms and functions of urban technology.

Joss and Molella summarized the contradiction between concepts, structures, and ideologies that combine the ideals of modern technology and industry [35]. If an eco-city is seen as a manifestation of the perpetual practice of the 21st-century city, it is shaped by the dual challenges of global climate change and rapid urbanization. However, if the current green technology of the eco-city is not implemented, the ecological resources become a one-time consumption of green real estate and land development. Whether the development logic of ecological commodification as a selling point can ensure the continuous operation remains a concern.

In the following, the practice of Shanghai Dongtan Eco-city is taken as a case to explore the construction of China’s eco-city, as an eco-technology-oriented city, as well as the relationship between different actors and related contradictions and structural problems.

2.4. Implemented Eco-City Projects in China: Differentiated Pathways and Recurrent Patterns

China provides one of the world’s most intensive contexts of eco-city experimentation, with eco-city, low-carbon city labels adopted across hundreds of projects and policy pilots [1,9,14].

Yet, scholarship repeatedly cautions against treating China’s eco-cities as a single model. Instead, empirical studies differentiate multiple pathways: (1) joint-venture eco-cities (e.g., Sino-Singapore Eco-City), (2) large-scale domestic greenfield new towns that mobilize eco-city branding to restructure peri-urban land and infrastructure investment, and (3) policy-driven programs such as low-carbon city pilots and eco-civilization demonstration agendas that reshape local targets and evaluation frameworks [1,9,12,15,35].

Existing research shows three pathways: First, eco-city delivery is often tied to state entrepreneurialism and land-based accumulation, where eco-city discourse and indicator systems are used to attract investment, and legitimize large-scale land development [7,9]. Second, many projects exhibit techno-managerial governance, “urban technology” packages are positioned as the main route to sustainability [7,12,35]. Third, comparative research on cases such as Shanghai and Tianjin stresses hierarchical experimentation, in which the developmental outcomes of eco-city projects are strongly shaped by central-local relations, administrative rescaling, and the changing balance between demonstration politics and market feasibility [7,8,21].

To respond to calls for more project-centered assessments of implemented eco-city initiatives, Dongtan is used as a critical case of developmental sequencing. Rather than treating Dongtan as a single “failed eco-city”, this paper positions it as a representative trajectory in which an internationally branded, demonstration-oriented masterplan is followed by selective implementation and subsequent functional reorientation and narrative rebranding, from an eco-city vision to an elderly care development and, more recently, an “eco-island” framing.

3. Methodology

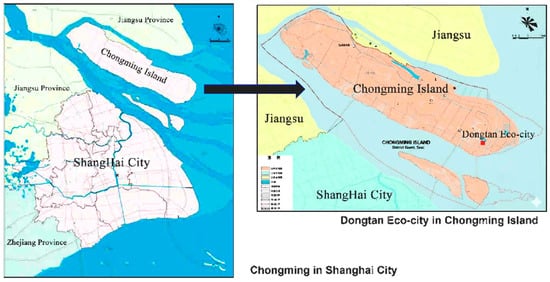

This research adopted a qualitative method utilizing secondary and field research data. This study scope focuses on the Dongtan area in Chongming district of Shanghai, at the mouth of the Yangtze River (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

The location. Source: drawn by the authors based on “Shanghai Chongming District Master Plan and Land Use Plan (2017–2035)”.

The data adopted are sourced from: (1) official profiles and reports; (2) participant observation; (3) semi-structured in-depth interviews.

In terms of participant observation, it can provide a more accurate understanding of the true situation and functional relationship between the structure of local society and various factors in the social culture through long-term contact and understanding the interviewee [36,37]. The authors observed different actor groups involved in (or affected by) Dongtan eco-city development, participated in their daily routines and work settings when feasible, and documented observations in fieldnotes. These records were subsequently organized into written memos that captured recurring events, interactions, and tensions relevant to the project’s evolution.

In terms of semi-structured in-depth interviews, this part of the data consists of 27 semi-structured interviews conducted between 2017 and 2022 (Table 1). The interviewees included local residents and farmers in Chongming District, planners related to planning of Dongtan eco-city, scholars, and real estate developers/intermediaries, etc. Interview recruitment combined purposive sampling (to ensure coverage of key stakeholder categories) and snowball sampling (to access additional informants through existing networks in planning circles and local communities). Snowballing was facilitated by introductions from acquaintances in urban planning and locally embedded social ties, which increased cooperation and supported the successful completion of in-depth interviews. Each interview lasted approximately 30–60 min. Interviews followed a semi-structured guide organized around core themes in China’s eco-city development (e.g., planning rationales, implementation bottlenecks, governance arrangements, and shifting project imaginaries). The interviewer used follow-up and probing questions to clarify causal sequences, elicit concrete examples, and explore divergent interpretations while maintaining alignment with the study’s main analytical questions. All interviews were transcribed verbatim and compiled into a case database.

Table 1.

interviewees’ profile.

In terms of coding and thematic analysis, the research process involved identifying and labeling meaningful segments of the interview transcripts. These segments pertained to key themes including planning ambitions, land and financial mechanisms, regulatory constraints (notably ecological protection requirements), technological adoption, operational challenges, demographic shifts, and discourses surrounding project “success or failure.” Nonetheless, due to the constrained sample size (27 interviewees), the subsequent analysis prioritized a direct interpretation of the Dongtan project’s developmental trajectory, foregoing the construction of a more extensive coding framework or discrete analytic categories.

In terms of the mitigating researcher bias and strengthening credibility, this study uses several strategies to reduce potential researcher bias, enhanced the reliability and interpretive rigor of the qualitative analysis. First, interview accounts were cross-checked by data triangulation against fieldnotes and official documents to avoid crelying on single-source narratives. Second, we contrasted perspectives that were retained rather than forced into a single storyline, and disconfirming evidence was actively sought. Third, the researchers use the verbatim transcripts and illustrative quotations, which helped anchor claims in the empirical record and limited over-interpretation.

In the in-depth interview, the researcher draws up a semi-structured interview outline based on the structure and themes of eco-cities in China, and discusses in-depth content with tracking questions, expands the width of the interview with exploratory questions, and focuses on the main axis of the research step by step, and puts forward some sharper questions at an appropriate stage to achieve more in-depth discussion. After the interview, the researcher will transcribe the content of the interview into a verbatim manuscript and organize it into the case database.

4. Transformation from Dongtan Eco-City to Part of Chongming World-Class Eco-Island

Chongming Island, positioned as a “world-class ecological island” in the Shanghai Urban Master Plan (2000–2020), is the third largest island in China. The Dongtan Eco-city Initiative was born around 2000, when China and Britain expressed willingness to cooperate in developing Chongming Dongtan into the first sustainable eco-city in the world. The Chongming Eco-Island Project was originally a policy experiment for Shanghai’s world-class ecological island, and also an exploration of “best practices” based on sustainable development. This represented an upsurge of construction after the “industrial zone fever,” the “university town fever,” the “eco-city fever,” and the “smart city fever” [27,38]. This trend essentially constitutes a fever of eco-commercialization or green commercialization.

The Dongtan eco-city project originated in 1998. Shanghai Industrial Investment Co., Ltd. (SIIC) purchased 85 km2 of land in Dongtan for 2.8 billion RMB. The Dongtan project was envisioned to be a large-scale development integrating wetland protection and ecological development, including the construction of sightseeing spots and modern agricultural park. In April 2001, SIIC established a subsidiary named SIIC Dongtan subsidiary. Since then, Dongtan project has been one of the primary businesses of SIIC.

In November 2002, Shanghai Municipal Planning Administration (SMPA) officially approved the Shanghai Chongming Dongtan Overall Structure Plan (“Dongtan Plan”) reported by SIIC. SIIC first hired McKinsey (a consulting company) to conduct a comprehensive evaluation of the project design practices submitted by different design and engineering companies and finally chose ARUP company (a UK design company). The president of ARUP then visited Shanghai to negotiate details with the SIIC [15]. In 2006, SIIC, ARUP, HSBC, and the UK Investment Bank signed a cooperation agreement for sustainable development capital financing. In 2007, Dongtan Eco-City was named “Greenwasher of the Year” by Ethical Corporation magazine [39].

On 19 January 2008, British Prime Minister Brown visited Shanghai to attend the signing ceremony of the Memorandum of Understanding on the Design, Implementation, and Financing of China’s Sustainable Eco-City Project at the Shanghai Urban Planning Exhibition Center. At the same time, Peter Head, the head of ARUP China, submitted the Dongtan Eco-City Master Plan. According to this memorandum, China and the UK would cooperate in developing Chongming Dongtan as the world’s first sustainable eco-city.

However, although China and Britain signed the memorandum, the Dongtan Eco-city project ultimately failed [21]. “As far as I know, it was put on hold indefinitely, and the SIIC did not inform ARUP” (P9, Shanghai, 2020). “The latest development permit for the Dongtan project was issued in 2006, and the validity period of the Construction Land Planning Permit of different regions is set by the local authorities and is generally six months to one year”(G1, Shanghai, 2018).

As for the reasons behind the indefinite delay of the Dongtan project, although SIIC never gave answers, other evidence related to planning and construction may offer insights. Not only would its positioning for building high-end residential buildings on wetlands damage the ecologically sensitive Yangtze River estuary, but its financial plan for a new town with 500,000 people was also considered infeasible. Whether due to political tensions, financial issues, or environmental challenges, with the departure of Ma Chengliang in 2008 (the president of SIIC Dongtan Branch), the Dongtan Eco-city project was put on hold indefinitely2.

In 2010, SIIC began to adjust the location of the Dongtan project, aligning with the Chongming Ecological Island Construction Outline (2010–2020), and the requirements of the Shanghai Municipal Party Committee and the municipal government for the development of Dongtan. SIIC upgraded the Dongtan Company, which is responsible for the development of Dongtan into a directly managed enterprise, and invested heavily to fully start Dongtan’s infrastructure projects.

“The first phase of the infrastructure project started construction in 2012. Meanwhile, six roads and 19 bridges, such as Dongtan Avenue (12 km long), were completed and opened to traffic on 1 May 2014. In addition, The first phase of commercial housing around Dongtan area was delivered, and the second phase started construction.”(P9, Chongming, 2020)

The commercial housing mentioned above by the interviewee became the elderly community for the land development of the Dongtan, which covers an area of about 180 hectares and can accommodate more than 10,000 elderly people. As interviewee G1 said: “The construction land planning permit for the Chongming Dongtan Community CCRC Phase I project has been issued. The authorized land user is Shanghai Industrial Pension Development Co., Ltd. The location of the land is the Dongtan start-up area, with a land area of 68,070.6 square meters.”

At this point, Dongtan Eco-City is no longer feasible in development. Dongtan Eco-city became the predecessor of the Dongtan elder community, a new property project for the elderly. This is the so-called “take the land first, and change the plan later.” In 2012, in line with the Shanghai Civil Affairs Bureau’s promotion of the ecological old-age community project and the pilot construction of an “ecological old-age care” demonstration base, the eco-city was transformed into an old-age community3 (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

The Public Garden Reduced to Vegetable Land and sold out but uninhabited Elderly Community Phases I. Source: photos by the authors.

In terms of Dongtan eco-city, beyond “gap between vision and implementation,” Dongtan’s shortcomings can be better understood as the outcome of interacting policy, technological, and demographic constraints. First, wetland conservation governance constituted a hard boundary condition for urbanization. The project was conceived adjacent to ecologically sensitive wetlands, and its approval process was entangled with concerns over ecological disturbance, producing higher regulatory uncertainty and delays that undermined financial and institutional commitment over time. In practice, conservation-oriented positioning did not eliminate development incentives; rather, it created a persistent tension between ecological safeguarding and land-based accumulation. Second, the issue was less whether “eco-city technologies” were theoretically available than whether an integrated socio-technical system was feasible under local fiscal, governance, and behavioral conditions. Dongtan’s proposed technical city package relied on high up-front capital, stable cross-departmental coordination, and long-term operational governance. However, the project encountered misalignments between imported planning scripts and local everyday practices, which discounted core low-carbon components and gradually re-centered the project as green-branded property development. Third, demographic restructuring on Chongming altered the demand base and directly challenged the planned population scale. Long-term out-migration to Shanghai and the resulting aging/labor shortages meant that projecting a large new-town population was institutionally and economically unrealistic; this demographic reality helped explain why the eco-city vision was later rearticulated into an elderly community and eco-island agenda. In this sense, demographic shifts were not merely a background variable but an active constraint shaping what kinds of “ecology” projects could be sustained, for whom, and through which development model.

By 2016, the project included the old-age community and extended as an essential part of the ecological island (specifically, the modern agricultural area). This comprised the Shanghai old-age community (with a total area of about 166.7 hectare), Dongtan Wetland Park (6.5 square km2), and Dongtan Modern Agricultural Planting Area (one of the bases of the “rice bag” and “vegetable basket” programs). In 2015, Chongming Dongtan completed 2133.3 hectares of rice, 1333.3 hectares of vegetables, and 80 hectares of aquaculture, with a grain output of 15,000 tons.

However, in the name of green development, Dongtan Eco-city is once again becoming a part of the Chongming Eco-island strategy. Chongming was upgraded from a county to a district in 2016. Han Zheng (former secretary of the Shanghai Municipal Party Committee) emphasized that Chongming’s change from the county to district is an important measure to optimize the urban layout and promote the coordinated and sustainable development of urban and rural areas and regions in this city. In other words, this also marks the change in Chongming’s planning into the direct jurisdiction of Shanghai, which is also regarded as a symbol that “the whole country vigorously promotes green development and economic transformation” (G1,2021).

What is more, the eco-island translates the development of Chongming into “ecology+”, that is, “Good ecology can add all kinds of industries, social construction, and lifestyle, and integrate ecological civilization construction into all aspects and the whole process of economic, political, cultural and social construction.” In July 2021, the Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences and China Agricultural Green Development Research Association released the China Agricultural Green Development Report 2020. As one of the first batch of agricultural green development pioneer areas in China, Chongming has a development index of 90.01, ranking first for two consecutive years.

5. Critical Analysis from the ANT Viewpoints in 1998 and 2024: Divided Allies

Urban planning has brought unsustainable practices, such as issues in transportation, housing, energy, economic development, natural habitats, and public participation, despite attempts to use the eco-city framework to achieve sustainable urban development [40]. Extant research has mostly viewed experimental urban places as enclaves, eco-cities in a vacuum environment (e.g., Tianjin Eco-City), urban practices that seek environmental and economic sustainability (e.g., De Jong, Korea), or zero-carbon emissions eco-tech cities (e.g., Masdar, Abu Dhabi) [4,7,8,41,42,43].

However, Dongtan, as an eco-city project that started in 2004, was planned and constructed by ARUP, then transformed into an elderly community in 2012, and extended as an essential component of the ecological island. This part attempts to review the development of Dongtan in the past 15 years, selecting the Dongtan Eco-city stage (1998–2008) and Dongtan Development Zone (2010–2022) as the focus.

Firstly, the eco-city has become a new concept for slogans and local marketing. From the perspective of individual actors, the new space development strategy has triggered the third wave of “eco-city fever” after the “development zone fever” and “university town fever.” For developers and consultants, the construction of commercial projects and the planning and design of new towns are highly profitable industries. Therefore, the central and foreign, central and local developers and consultants built rapport quickly.

Secondly, in the Post-Eco-City era, the eco-city project, as infrastructure, expanded the project volume and became a world-class ecological island. As most interviewees say, the Dongtan eco-city project failed in sustainable practice, but this urban-rural project was reborn as a new project named “community pension project” and linked to the Chongming world-class ecological island.

This section aims to represent the actor networks, clarify the participation motivation of various actors, and categorize the actors in the process of eco-city and Chongming ecological island construction into four levels: the state, the local government, the consultant company, and the individual actors.

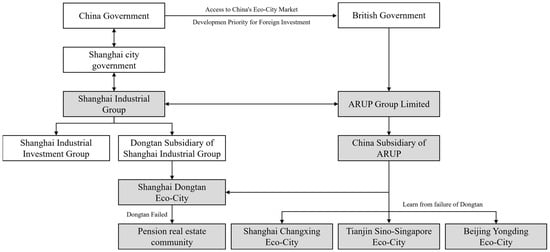

5.1. Actors Network of Eco-City in 1998–2012

The Dongtan eco-city project, as the earliest eco-city experiment in China under the background of China’s land policy transformation, with a planning-design area of 23 km2, explored the feasibility of an urban development model in which all actors achieve a win-win, eco-friendly, and economically sustainable outcome. According to fieldwork, the Dongtan Project was a win-win situation in the 2000s, the network of actors in Dongtan eco-city project is as Figure 4 shows. How could this large-scale urban construction be realized from planning concept to practice, involving stakeholders such as foreign-funded enterprises, state-owned enterprises, local governments, and developers pursuing their financial interests?

Figure 4.

Network of Actors in Dongtan Eco-city Project. Source: drawn by the authors.

Firstly, for national actors, the trend of the new international “best practice” of eco-city and the influence of planning discourse represented by foreign multinational design companies have become the best field for the Chinese government to face the environmental crisis and demonstrate its determination to the international community. Former London Mayor Kenneth Livingstone praised Dongtan for its groundbreaking work that led to a more sustainable future. Additionally, foreign governments are actively involved in deepening cooperation through China’s ecological practices, thereby promoting the export of their eco-tech industries [44].

“The reason that Shanghai Dongtan eco-city project, which is the world’s first eco-city model developed under Sino-British cooperation, has received international attention is mainly due to the attention of the Chinese and British high-level officials. Chinese President Hu Jintao and British Prime Minister Tony Blair re-raised the Dongtan Eco-city Project in London in 2006. Moreover, other actors SIIC and ARUP signed a cooperation framework agreement.”(G2, Shanghai, 2018)

“I remember that the British want to help and encourage China push the construction of an eco-city of the same type in Dongtan in the UK”(P3, Shanghai, 2017)

Furthermore, the British also provided China with (then worth) US$100 million to help China cope with climate change and introduce energy-efficient technologies [15]. To experiment with sustainability in Dongtan is both a financing model for China’s eco-cities and a business strategy that ARUP adopts to determine eco-city models and actively seek new possibilities for cooperation.

In terms of the Shanghai Municipal Government, as the leader of the Dongtan Eco-City, it hoped to use Dongtan to acquire more competitive advantages and promote the Shanghai World Expo through the construction of the Dongtan Eco-City. On the other hand, because China’s urban space development has moved from incremental planning to stock planning, it sought to find new urban construction land finance.

Secondly, in terms of local government and SIIC, they are two sides of Shanghai’s development, with the same goal and deep binding. It took four years to obtain land from 1998. However, considering the national nature reserve in Dongtan, the Shanghai government did not approve the development project in Dongtan until 2002. This process is more complicated than imagined, as Peter Head, director of ARUP, recalled: “Shanghai government wanted to develop Chongming Island, and the Beijing government (central government) was concerned because it poses a threat to wetlands [15]. However, the central government indicated to the Shanghai government that if the development plan does not focus on land development, it will not affect the sustainability of the land and will not affect the ecology. It can be developed” [45].

In addition, “The prerequisite for development is that Chongming Island is positioned as a world-class ecological island. It will be more forward-looking to carry this out all the time, especially in a current political and economic context.” (G1, Shanghai, 2019). The latter also left an opportunity for the re-development of Shanghai Dongtan. After the ecological heat retreated [38], a new development experiment was born again [46].

Thirdly, in terms of the design unit ARUP and developer SSIC, Dongtan Eco-city is a window for capital accumulation and the right to speak. It is also an investment opportunity to seize China’s eco-city fever. As an interviewee from a planner in SIIC said: “The West creates global warming, and the Eastern countries are increasingly actively looking for solutions for us. The scale and ambition of the Dongtan Eco-city Project in Shanghai, if effective, will be a beacon and how the world will achieve a low-carbon future”. Local developer SIIC expects to increase the land price and surrounding housing prices through the development of Dongtan, resulting in substantial financial returns and long-term reputation (also see Figure 2).

ARUP, as a consultancy company with discourse in international eco-city planning and design, officially opened the market for China’s eco-city design through the creation of Dongtan eco-city from 2005 to 2009; ARUP signed eco-city project development agreements and contracts in Changchun, Changsha, Changxing, Chongqing, Huzhou, Qingdao, Tangshan, Wuhan, Wuxi, Zhengzhou, and Zhuzhou [47]. In addition, Peter Head, head of ARUP China, is the engineering director of the planning and development of Dongtan Eco-city and Langfang Wanzhuang Eco-city. Because of his international reputation in China’s ecological practice, he was nominated by Time Magazine as one of 30 world environmental heroes in 2008. In the same year, he won the Sir Frank Whittle Award from the Royal Academy of Engineering to recognize his contribution to a society that promotes sustainable development.

The Dongtan eco-city project formed a co-constructed network of stakeholders including financial institutions (HSBC, financial loan provision), design consulting companies (Sustainable Development Capital Law Firm, SDCL; Rider Levett Bucknall) and real estate management institutions (Shibang), etc., namely, which would jointly create a better sustainable development plan for Dongtan, but primarily to meet their respective interests. Dongtan project had many designs, consulting and service projects for these affiliated actors. Hald’s field research mentioned conflicts among different actors and the ecological dream as an unrealistic utopian experiment in a vacuum environment [45].

“SIIC stated that their main concern is social and environmental sustainability, while ARUP is more concerned with economic sustainability; however, the project has not shown the possibility of eco-city sustainability in terms of Dongtan eco-city and the elderly community.”(P9, Shanghai, 2020)

“The property developers in Dongtan are very enthusiastic, but their priority is to enhance the profitability of Dongtan, that is, to build high-quality ecological housing and a pleasant environment related to an eco-city to attract more wealthy middle class, rather than how to ensure sustainable development.”(L6, Chongming, 2019)

From this point of view, the person in charge of a real estate agency also expressed great confidence and enthusiasm for the major development and construction when selling the house to me.

“The development of Dongtan has led to a rapid increase in house prices, from 1000 yuan per square meter in 2002 to 30,000–40,000 yuan per square meter in 2017. Correspondingly, the land price has also risen. Whether or not the Dongtan project is finally finished, the SIIC owns the land, so the worst situation can also earn financial profits from land transfers.”(L6, Chongming, 2019)

Moreover, ARUP also has the reputation of benefiting from Dongtan; it not only can carry out more eco-city projects in China but also participate in other types of architectural design (e.g., Beijing TV station design). “SDCL an investment consulting firm that specializes in providing services for large-scale sustainable development projects, is responsible for the feasibility analysis of financial structures in Dongtan. However, the irony is that the financial infeasibility of Dongtan is the main reason for the stranding of Dongtan Eco-city Project.” (L6, Chongming, 2019).

Therefore, it is suspected that the Dongtan project indeed harms the national nature reserves in Shanghai under the cover of environmental protection and ecology; in essence, it is a means of land speculation and place marketing.

Fourthly, regarding the construction of eco-cities, as a “playing for keeps” game, whose interests would be damaged? While excluded from the above win-win network, what became of the excluded construction workers, residents, and farmers? Apart from the above actors, marginal populations and nonhuman actors are essential cornerstone of this network. The project proposal stated that no farmers would be forced to relocate during the eco-city construction. However, almost all respondents specializing in urban planning mentioned that “due to the lack of public participation, the planning process merely informed farmers or residents to view the public announcement results after the planning had concluded”. For instance, one interviewee stated: “Many people in Chongming County have gone to Shanghai to drive taxis. Few people stay on the island for employment. Also, Dongtan Eco-City is very remote. There are not many people going there. I know little about the eco-city there.” (L1, Chongming, 2018)

However, regardless of whether specific residents, farmers, and construction workers were negatively affected, they were generously subsidized as stakeholders in the Dongtan development process. Hald and Xie discussed the exclusionary effects of eco-cities in their studies [6,45]. In contrast, this paper argues that the current Dongtan Eco-city has been transformed into an elderly community, emphasizing the class nature of pension real estate. Among local residents, there are supporters, particularly those holding household registration in Chongming District. In this wave of development, all residents who own houses are to be resettled, with each family receiving three houses (one for the elderly, one for young couples, and one for their children) while receiving compensation for the land acquired. One local fruit trader interviewed explicitly mentioned the following: “Chongming people believe in local government. We will not force the government for money. If the government has money, it will compensate us.” There are also opponents. One noted: “What is the nature of ARUP and SIIC? They are enterprises that need economic profits. Look, Shanghai Dongtan Eco-city is designed with a population of 500,000. Look at the number of people living in Chongming Island now, which is 100,000 less than ten years ago (implying the projected numbers are inflated). I participated in one of the sub-projects that year. As a native of Chongming, I think this is too unrealistic. Chongming is primarily a rural area. It serves as Shanghai’s ‘vegetable Basket’ and may be the first choice for rural weekend vacation in the future. but an eco-city of 500,000 people, if nothing else, will talk about its impact on the environment. How can it be ecological and sustainable?” (P9).

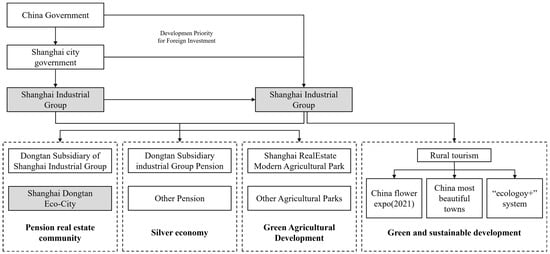

5.2. Actors Network of the Changing Eco-City in 2012–2024

In 2010, it was widely acknowledged that “the Dongtan eco-city project had failed.” Real estate development in Dongtan area has stagnated, even as real estate markets in other cities in full swing. As the interviewee P10 noted, China’s real estate development has gone through four stages.

In the first stage, when the Asian Financial Crisis broke out in 1996, China’s imports and export, foreign direct investment (FDI) were significantly affected. Stimulated by policies from the Chinese government between 1996 and 1998, housing construction became a new economic growth point and a consumption hotspot.

In the second stage, the subprime mortgage crisis in the United States in 2008 led to a global economic crisis. To stimulate the declining economy, the Chinese government allocated four trillion RMB (approximately $558.184 billion) to invest in infrastructure construction. Furthermore, the Central Bank relaxed real estate regulations and lowered interest rate on personal mortgage, causing the real estate market to surge.

In the third stage, the inventory of commercial housing in China reached more than 620 million square meters in 2014. In August 2015, the Shantytown (Penghuqu) Renovation Plan was launched, leading to another boom in the real estate market. A large number of abandoned residential areas in all cities (especially third-and fourth-tier cities) were rebuilt, triggering a sharp rebound in real estate development. This period is also considered the “bubble stage” of Chinese real estate.

In the fourth stage, the China Central Economic Work Conference in 2019 formally put forward the policy that “houses are for living, not for speculation” alongside comprehensive purchase restriction. In this context, the overheated market began to cool down, and the sales volume dropped sharply (see Figure 1).

What is the future of Dongtan and Chongming? At this juncture, the development of the Chongming Dongtan area began to transform (see Figure 5). First, the Shanghai Social Welfare Bureau (SSWB) advanced a community designed for the elderly. Since 2010, SSWB has been planning an Elderly Community to provide for the elderly in Shanghai. The total construction area of this Elderly Community, named Shangshi Ruici Garden, is about 1 million square meters with an investment of 15 billion RMB (about $2.28 billion). Construction of the first phase started at the end of 2014. Subsequently, a number of health care and medical aesthetics projects, such as Guohua Ecological Rehabilitation Center, Shangshi Dongyi Sanatorium, Samantha (2019), CITIC Pension (2018), and Taibao Home, are under construction.

Figure 5.

From Dongtan Eco-city to Chongming Eco-island Project. Source: drawn by the authors.

Second, although the residential plan of Shanghai Dongtan Eco-city accommodating 500,000 people failed, there are still some follow-up developments, such as Shangshi and Fengyuan (which are primarily villas) and Shanghai Beach single-family villas. Third, the initial development of the old-age community was not ideal. With the re-initiation of the Chongming Low-carbon Eco-island in 2014, some projects sprang up rapidly, such as Chongming Dongtan Ecological Park, Shangshi Agricultural Park and Holiday Park, East Lake Tourist Area, Ma Shang Club, etc. On the whole, elderly care, eco-housing, and a green and sustainable agricultural economy are the three directions outlined in the Development Outline of Chongming’s World-class Eco-island (2021–2035), which points out that the Shanghai government will develop Chongming island to provide health care and specialized medical rehabilitation services for the elderly.

6. Towards Ecological and Economic Sustainability: From Eco-City to Eco-Island

As a traditional agricultural area on the edge of the mega-city Shanghai, Chongming Island has experienced a long-term migration to Shanghai. This has caused a shortage of local labor and led to the abandonment of extensive farmland. However, strict Chinese land use regulations stipulate that reserved farmland had no economic value until the Dongtan Eco-city project presented an opportunity to change land use and attract investment to the island. As Chinese technocrats often assert, “Problems in development should be solved by development;” thus, the sustainability of Chongming island depends on its economic development. Chang pointed out that: “Sustainable development means environmental protection, but we already have a good environment [21]. The natural conditions here are very good, but everyone wants to leave the island (go to Shanghai)… Now, most people who stay on the island are the elderly and children… We need new industries or businesses to come to the island. We must attract new investment, so that we can have better development, which is the only thing that can make this island sustainable. Therefore, we use the environment to attract eco-enterprises. Building an eco-city or an eco-island is our plan and hope. Sustainable development is for a developed place. For rural areas outside such a big city, like Chongming, economic development is needed before sustainable development.”

This viewpoint aligns closely with the remarks of an interviewed technocrat (P9): “In the past, Chongming sold vegetables; the Eco-city sold fresh air; now, it is selling the rural lifestyle. But if it becomes too modernized, why would we Shanghainese (who don’t even regard Chongming as truly Shanghainese) come here?”

6.1. Whose Eco-City? The Technological Fix

This research states that the planning and design of Dongtan Eco-City were based on the eco-technology of new city planning. The space adjacent to the Dongtan ecological wetland was selected for development. The plan emphasizes that it will not affect the surrounding wetlands and agro-ecology. The new city was also envisioned as a “zero-carbon city” due to the allocation of green technology. From the perspective of urban technology, Dongtan Eco-city is a separate environmental space that exists in the form of an ecological urban enclave; it is an urban system within a self-contained entity supported by green environmental technology.

The Dongtan Eco-city Project expected to realize low-carbon energy through the carefully design of “underground garbage treatment systems; integrated water treatment systems (wastewater, rainwater, groundwater); extensive zero-carbon public transportation systems; improved soil quality; restoration of wet green ecological corridors; and microclimates.” Moreover, the Dongtan Ecological Indicator System was established, and the “Dongtan Experience” of the eco-city development model was promoted as the National Eco-City Model [48]. However, the eco-enclave of Dongtan Eco-city finally turned into a “planning on the wall” eco-slogan, which raised many questions.

First, Dongtan is an agricultural area, yet its development goal was framed as an ecological sustainable city based on ecological modernization. ARUP’s proposed pedestrian-oriented traffic design contradicts the prevailing preference for automobile usage among Chinese population. In addition, the ecological structure of the eco-city did not consider economic and financial realities, nor did it assess the environmental vulnerability of Dongtan. The concept of a “technology city” or European-style eco-city reflects a natural scientific landscape envisioned by Western Europe and the United States in the 1930s. Consequently, the post-modernist architecture fails to reflect the culture design elements of Shanghai and Chongming Island. At the same time, the slogan of “Dongtan Eco-City, Better Life”, which resonates with the spirit of the Shanghai World Expo, is inconsistent with the future urban imagination (characterized by modernization, motorization, and intelligence) promoted by China’s rapid growing economy [35]. Therefore, the disconnect between foreign consulting companies and local Chinese conditions eventually resulted in an enclave-type eco-city, becoming a separate geographical space incompatible with the surrounding environment.

Secondly, the Chongming Ecological Island Plan was approved in 2010. However, different planning and management departments, such as National Eco-city Standard (2004), the Ecological Administrative Region (2007), Caofeidian’s Eco-Index System, and the Eco-city Development Index System (2011), failed to reach a consensus on the understanding of ecology. The ambiguous ecological standards and indicators raise doubt about whether the ecosystem of Dongtan Eco-city and Chongming island can interact positively. In particular, after ten years of the Dongtan project, construction began in 2014 on the land designated for the elderly community project, covering a total area of 2 square kilometers. There are growing concerns regarding the ecosystem of Chongming Island, specifically whether the emission reduction effects achieved by applying green technology can truly offset the carbon emissions generated during the repeated construction processes in Dongtan.

Third, Dongtan Eco-city is positioned as a model of an international eco-city and is also a product of techno-urbanism and modernism. It seeks to achieve this by formulating an indicator-oriented green urban technology system. The planning of Dongtan Eco-city puts forward the following main principles: (1) protecting the wetland environment; (2) improving the quality of life and creating a desirable lifestyle; (3) creating an accessible city; (4) rooting Chinese culture in urban texture; (5) managing the use of resources in an integrated way; (6) remaining committed to carbon neutrality; (7) using management to achieve long-term economic, social and environmental sustainability; (8) creating a whole, active and developing community [49].

This sustainable framework system has been applied to subsequent developments such as Caofeidian, Tianjin Eco-city, and Shenzhen Pingdi Eco-city. Field investigation found that similar planning discourses appear in their respective propaganda slogans. Essentially, the focus is on how to solve the problems of energy, water, waste, transportation, ecosystem, and social and economic development in the design of the project and create a sustainable development system that combines the built environment, economy, and society. This encompasses healthy ecosystems, biodiversity, supportive built environment, environmental planning of resource conservation and pollution prevention, and economic planning for ensuring economic growth, private profit, market expansion, economic stability and efficiency, and equity. It also included local reliance, inclusion/consultation, empowerment, participation, social accountability, and appropriate technology [48]. In short, Dongtan has become a model for China and other developing countries to develop similar cities.

It seeks to achieve a harmonious coexistence between the city and nature through purely technical means. On one hand, it proposes to build an ecological town with a population of 100,000 and a large-scale old-age real estate community. On the other hand, it envisions an ecologically harmonious urban environment respectful of natural and local agro-ecosystems, this appears to be a contradiction. In this process, the provincial government obtained land finance through land development; SIIC acquired substantial land reserves. and ARUP secured economic returns. The middle class received a return on investment from the development of Dongtan Eco-city, and local farmers received large-scale subsidies for demolition and land requisition. Thus, the construction of the ecological city has achieved a win-win situation for all participants.

Dongtan Eco-city was once projected to be the first purpose-built eco-city globally, dedicated to becoming a model for Chinese cities and the developing world [48]. Although it lagged behind Sun City (referencing the retirement community model), it ultimately failed (Southern Weekend). Dongguan has not become a template for China’s future urban design. Nevertheless, it became the successful precursor to the Tianjin Eco-city, helping China to explore best practices in eco-city planning. It also served as a global pilot for Arup and other companies to explore future urban self-sufficiency models and the concept of the technology city.

The eco-city plan has been transformed into an old-age community and is now part of the eco-island plan. However, the planning and the first phase of development of the Dongtan Eco-city have stimulated significant enthusiasm for green buildings and influenced the goals of other sustainable urban development projects in China. In particular, the design of Dongtan Eco-city followed the “comprehensive urbanism” method, considering environmental, social, and economic aspects to create a sustainable community; specifically, the spatial layout, environment, transportation, and infrastructure of Dongtan were carefully planned [48]. However, due to the lack of public participation, external actors (acting as essential participants), imposed excessive tasks upon Dongtan Eco-city. The ambiguous positioning regarding “whose eco-city” it blurs the city’s function as a consumer and distributor of goods and services, which also signifies the failure of Dongtan’s ecological commercialization.

6.2. One-Time Ecology? After Green Real Estate and Ecological Commercialization

Regardless of the validity of the eco-city’s technologically orientation strategy, the planned ecological approach in the practice of Dongtan Eco-city, specifically zero-carbon transportation and green energy construction, has been compromised. It slowly evolved into a green real estate development characterized by “mountains and waterfronts,” emphasizing a superior living environment and quality of life within a green ecological setting. This shift appeals to middle-class consumers.

First, in terms of planning and practice, the green gentrification of the countryside utilized natural elements (such as mountains and waterfronts) as ecological assets, extending from the urban area to the suburbs. Green gentrification is grounded in green governance, perpetuating the concept of replacing old or disorganized landscapes, improving green public assets, and enhancing urban landscapes. Dongtan Eco-city is not only a man-made environment but also a socio-ecological process. Urbanization shares a direct and intimate relationship with the transformation of nature, where natural ecology serves as an indispensable part of the urban process [50,51].

Through urban planning and design, the Dongtan Branch of SIIC transformed the green resources into consumable assets. By shaping an image of purity, safety, health, and ecology, and aligning with emerging real estate development, the project attracted the middle class who enjoys waterfront consumption and recreation. To the middle class, the eco-city appears to be a green real estate community featuring a waterfront environment, a pristine ecological landscape, energy-saving system, and a leisure lifestyle with green trails free from traffic congestion. However, this represents a middle-class eco-city utopia rather than a genuine model of ecological sustainability.

Second, in the context of green gentrification, ecology has become a commodity. The green commodification of the suburbs has replaced the living environments and employment opportunities of farmers in the lower socioeconomic class with the leisure and consumption spaces of the middle class, which has produced social exclusion and isolation effects. Whether or not this is ecologically sustainable is also debatable. Specifically, green gentrification will often lead to social exclusion and isolation, such as green assets crowding out other public services and community needs, displacing vulnerable ethnic groups, and destroying original flora, fauna, and old urban textures [51]. These issues might also be highlighted in the further construction of Dongtan.

Third, treating the original natural ecology as a commodity creates a dilemma. It involves a “one-time sale,” attached to a permanent residential product (with 70 years of property rights); thus, the maintenance of the original natural ecology becomes a problem. If the population exceeds the ecological capacity, is Dongtan Eco-City still an ideal new eco-city? The author interviewed a scholar engaged in the study of biodiversity and ecological vulnerability, whose research focuses on the impact of seawater flooding on Chongming Island’s soil salinity and biodiversity. In his actual follow-up monitoring, he found: “The real result is not as hypothetical as flooding of the sea will affect soil salinity and biodiversity. Because of the special topography of Chongming Island and the subtropical maritime monsoon climate zone, soil salinity and biodiversity are more susceptible to local vegetation. The first problem brought about by the massive construction of the Dongtan eco-city is that the vegetation is broken, the biodiversity is weakened, and the subsequent ecological footprint caused by population convergence will inevitably affect the local ecosystem.”

Transforming from a technological eco-city into technological agricultural district, the area increasingly resembles an agricultural or food landscape, typical of a mega-city rather than the traditional countryside. For farmers and migrant workers, both housing prices and the general cost of living remain prohibitively high.

6.3. A Great Leap Forward or Perspective Design: Towards an Ecological “Green” Commodity Frontier

Following policy reforms such as the tax-sharing system introduced in the mid-1990s, local governments have, to a certain extent, become corporate-like entities driven by development imperatives and local government performance evaluations. After China acceded to the WTO in 2001, fierce competition urged cities (especially coastal towns) to strive to become landmark regional centers with global influence, aiming to attract FDI and position themselves as regional hubs for multinational corporations [52]. The development momentum of China’s eco-cities is increasing, which has aroused the interest of the public and private sectors. Eco-cities have also become an essential battleground for urban competition, serving as a key green development strategy after 2012.

The competition between the Chongming government and the Shanghai municipal government has led to the accelerated construction of infrastructure and real estate. In this process, different departments lack policy coordination. Despite official concealment of the environmental impact on agricultural land, wetlands, and the island environment, the currently deteriorating ecological environment in Chongming leads to speculation that the construction of Dongtan Eco-city has done more harm than good regarding the protection of the island ecosystem.

Wu and Zhang suggested that local government corporate storytelling includes two aspects: the cities’ competing for a dominant position, and the state’s attempts to supervise and control the city [53]. In the ecological practice of Dongtan, the Shanghai Municipal Government obtained political priority, establishing the Dongtan model as a national highlight and a case study for eco-cities among local governments. However, following the “political earthquake” in Shanghai in 2006 (when Chen Liangyu, secretary of the Municipal Party Committee, was arrested), Tianjin Eco-City replaced Dongtan in obtaining political priority at the national level.

Although the Chinese government encourages the development of eco-cities, there are no strong economic incentives to encourage enterprises to invest in them. From Dongtan Eco-city to the Dongtan Elderly Community, and finally to becoming a part of the Chongming World Eco-Island (a frontier base of agricultural research and development, production and tourism), the capital accumulation logic of the government and state-owned enterprise developers has remained consistent: to attract FDI and financial interests using a “green” image and to promote the development of the Dongtan area.

However, the concept of planning practice has shifted from a “sleeping town” for the middle class to (1) the pension estate provides pension service and pension care, and (2) Chongming World Eco-Island. With increased profit margin, the economic sustainability of the Dongtan Block has dramatically improved. On one hand, municipal leaders are eager to maximize the significant economic benefits of land development. Improving performance and seeking promotion are the inherent impulse driving local government leaders in China to pursue urban entrepreneurialism [54,55].

On the other hand, as the central government’s strategy shifts from a growth priority to more “people-oriented” growth and ecological civilization, performance evaluations may be evolving. Therefore, entrepreneurial cities may not simply aim at economic growth or maximizing income. In this case, local governments can carry out ecological restoration, instead of pursuing growth at all cost [56,57]. Specifically, this process reflects the multi-scale governance of Shanghai municipal government in coordinating the planning of Chongming Ecological Island with the political agenda of national ecological civilization construction [58].

Although Dongtan Eco-city has lost its political priority, the provincial government’s subordinate, SIIC, actively strives to eliminate external adverse effects. Even with the destruction of local political ecology, under the flexible budget system, the development of cities by local governments and the central government remains insulated from bankruptcy.

From the perspective of urban political ecology, the change in the Dongtan development model represents the flexibility of local government power at the rural level. It is also the result of complex interaction among actors involving a series of political and pragmatic efforts, seeking potential developmental opportunity by adapting to the logic of China’s urban construction. This evolution signifies the integration of land interests and political interests into a shared vision of development [59] (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Transformation of Nature.

This research uses “commodity frontier” to conceptualize the dynamic process through which capital extends accumulation by opening up, reorganizing, and revaluing socio-ecological space so that new forms of “nature” can be rendered legible, investable, and exchangeable. This concept is especially useful for eco-city analysis because it emphasizes not only nature as a saleable asset, but also frontier-making as an evolving boundary process: the lines separating ecology from development, conservation from construction, and public environmental values from private rent opportunities are repeatedly redrawn.

In Dongtan, this study develop a concept of “green commodity frontier” to capture how successive development phases mobilize “green” narratives to create new investment rationales and to repackage local wetlands/agricultural landscapes into marketable “green” assets. This transformation unfolds in three stages. First, during the Chongming Dongtan Eco-city in 2000s, actors attempted to leverage Shanghai and its hinterland to produce or surpass the local (Chongming) residential commodity boundary. Second, after 2010, the eco-city project transformed into an elderly community to designed to attract the urban senior market by capitalizing on the favorable environment. Third, after 2014, the construction of Chongming Ecological Island, which was driven by the political agenda of “ecological civilization,” redraw the ecological commodity boundary. It successfully regained political priority through ecological agriculture and rural revitalization. Chongming has thus become a pilot area for the national ecological civilization demonstration zone.

The transformation of Chongming Dongtan (1998–2024) represents the progression from a premium eco-enclave to sustainable urbanism. It serves as a “green” commodity frontier that promotes capital accumulation in Chongming. By adjusting, adapting and identifying policy niche, actors at various scales utilize the city and its hinterland to transcend local commodity boundaries. Consequently, the space itself naturally becomes a commodity and a strategic choice for local capital accumulation. This process ultimately breaks through the framework of uneven development, allowing Chongming to gain new opportunities for development.

Although benefiting from the needs of state intervention and environmental protection actions, the transformation of the Dongtan area currently promotes sustainable capital accumulation and regional development. Could the Dongtan area and Shanghai’s Chongming Island fundamentally facilitate the logic and structure of urban development?

7. Conclusions: From Partial Eco-Utopia to the Holistic Ecological Practice

In China’s ecological practice, the movement of eco-city policies and discourse has been misappropriated as entrepreneurial place marketing and over-accumulation of primary and secondary circuits of capital. This top-down construction of the urban landscape represents a form of one-time ecological commodification consumption designed to satisfy various actors, often sacrificing the dynamic processes of the local ecosystem. This outcome is not simply the result of a failure in eco-city construction under the Chinese technology-city strategy. Rather, it is the result of the financial “soft budget constraint” system under China’s tax-sharing framework, as well as the tension between the country‘s short-term performance appraisal system and the needs of long-term ecological construction. Mainstream land interests and development imperatives have influenced the trajectory of the Dongtan area across its changing stages: (1) Dongtan as an eco-city demonstration site; (2) a real estate area serving as old-age communities; and (3) a demonstration area for modern agriculture, rural revitalization and ecological civilization. We found that during the development period from 1998 to 2010, the prevailing logic was driven by profitable housing and the illegal occupation of land for commercial development. In this context, green commercialization posed a continuous threat to green space. However, from 2010 to 2022, green commercialization evolved into a result of green space and sustainability.