Abstract

The study explores the concept of the X-Minute City, an evolution of the 15-min city paradigm, as an operational tool for sustainable urban regeneration in Europe. Starting from the goal of ensuring daily accessibility to key services within 5–20 min on foot or by bicycle, the research analyses how this proximity model can respond to contemporary environmental, social, and infrastructural challenges. Through a comparative approach between Amsterdam and Milan, chosen for their regulatory and cultural differences, the study combines documentary analysis, urban policy evaluation, and the construction of a grid of multidimensional indicators relating to proximity, sustainable mobility, spatial reuse, and social inclusion. In conceptual terms, the X-Minute City is understood here as a flexible and governance-oriented extension of the 15-min city, in which proximity is treated as an adaptive temporal band (5–20 min) and as an infrastructure of multilevel urban governance rather than a fixed and universal design rule. The findings highlight that in the Netherlands, the model is supported by a coherent and integrated regulatory framework, while in Italy, innovative local experiments and bottom-up participatory practices prevail. The analysis demonstrates that integrating the X-Minute City with multilevel governance tools and inclusive policies can foster more equitable, resilient, and sustainable cities. Finally, the research proposes an adaptable and replicable framework, capable of transforming the X-Minute City from a theoretical vision to an operational infrastructure for 21st-century European urban planning. The limitations of this predominantly qualitative, document-based approach are discussed, together with future directions for integrating spatial accessibility modelling and participatory methods.

1. Introduction: From the 15-Minute City to the X-Minute City

Contemporary urban planning is at a crucial crossroads, called upon to respond to a multitude of complex, systemic, and interconnected challenges. These include increasing socio-spatial inequality, climate urgency, the ecological transition, aging infrastructure, and the growing demand for quality urban life. In this context, European cities are called upon to reinvent themselves by adopting new spatial development models that transcend the centre-periphery dichotomy and foster proximity, resilience, and inclusion [1,2].

Within this context, this study introduces the concept of the X-Minute City as a scalable and adaptive evolution of the 15-min city paradigm. Unlike the fixed temporal frame proposed by [3], the X-Minute City adopts a flexible range (5–20 min) that adjusts to the morphological and functional diversity of urban contexts. More specifically, the X-Minute City is conceived here as a proximity framework in which different time thresholds correspond to different combinations of services, densities, and user needs: shorter ranges (around 5–10 min) are associated with everyday functions such as basic retail, local green spaces, primary education and neighbourhood health services, while longer ranges (15–20 min) refer to more specialised functions, workplaces, cultural facilities or intermodal hubs. Rather than prescribing a single universal value, the model emphasises the contextual calibration of time–distance relations according to urban morphology, transport options, and the differentiated capabilities of residents (children, elderly people, persons with disabilities, low-income households). Unlike existing proximity-based or polycentric accessibility models, which primarily focus on spatial optimisation or time–distance efficiency, the X-Minute City is conceptualised here as a governance-oriented framework. In this sense, proximity is framed as an adaptive temporal band (5–20 min) whose effectiveness depends on institutional capacity, policy coherence, and participatory governance and the X-Minute City functions not as a spatial performance model, but as an analytical and operational lens for understanding how proximity is embedded within planning systems, regulatory frameworks, and urban regeneration policies.

It also expands the model from a spatial vision to an operational framework, linking proximity to multidimensional indicators of governance, mobility, reuse, and inclusion. This allows residents to access a full range of essential services on foot or by bicycle, within a time frame ranging from 5 to 20 min, including work, education, healthcare, culture, commerce, recreation, and quality public spaces [4,5,6].

In this perspective, the X-Minute City is not simply a rebranding of the 15-min city, but an attempt to frame proximity as a governance infrastructure and as an analytical lens for urban regeneration. By explicitly integrating indicators related to spatial justice, land-use restructuring (e.g., brownfield regeneration, redistribution of services) and socio-ecological transition, the concept connects proximity-based planning to broader debates on the “right to the city”, climate neutrality and post-carbon/post-growth urbanism.

Application of the X-Minute City is highly interdisciplinary and requires the integration of tactical urban planning tools, participatory planning, data-driven governance, and user-centred urban design [7]. The goal is not only to improve the spatial and functional efficiency of cities, but also to build resilient communities and inclusive public spaces, fostering forms of interaction and social cohesion.

Proximity, as outlined in the ‘15-min city’ framework, refers to the spatial arrangement of resources, services, and amenities such that they are readily accessible within a short travel time. This paradigm fosters a sense of community belonging and social cohesion by shortening the distance citizens must travel to meet their daily needs, thereby reshaping urban life [8,9].

Proximity is not merely about physical distance but also involves the organization of urban space to facilitate social interactions and community engagement. According to contemporary studies, proximity results in diverse social interactions, a greater sense of belonging, and improved overall well-being of residents [10,11]. For instance, research indicates that neighbourhoods designed around the principles of proximity tend to encourage walking and cycling, which in turn fosters healthier lifestyles and reduces reliance on motor vehicles [12,13].

Proximity also plays a crucial role in addressing social inequalities within urban environments. By ensuring that essential services are evenly distributed across neighbourhoods, the ‘15-min city’ model can mitigate disparities in access to necessary facilities, particularly for marginalized communities [14,15]. It has been argued that to achieve inclusiveness, urban planning must prioritize proximity, thereby preventing the socio-spatial segregation that often accompanies urban growth and gentrification [16].

Proximity, understood as spatial but also relational accessibility, is directly linked to the concept of the right to the city [17] and translates into policies that recognize the value of neighbourhood life, functional diversity, and community as key elements of urban quality. In this sense, the X-Minute City represents a paradigm shift: from a city model centred on automobile mobility and functional zoning to a hybrid, decentralized, and polycentric urban ecosystem capable of enhancing local resources, reducing energy dependence, and promoting new sustainable lifestyles [18].

This study analyses the concrete application of the X-Minute City model in two different European urban contexts: Milan (in Italy) and Amsterdam (in the Netherlands). The selection of these two cities responds to the desire to explore how different regulatory frameworks, planning systems, and urban governance models influence the capacity to incorporate, adapt, and implement proximity-based strategies. Amsterdam is characterized by a systemic and cohesive approach, supported by advanced regulatory tools, consolidated co-planning practices, and a strong focus on active mobility and climate neutrality [19]. Milan, on the other hand, shows greater administrative fragmentation but stands out for its growing experimental vitality and the emergence of bottom-up local initiatives that reinterpret the proximity paradigm in a creative and participatory way [6,20].

Through a systematic comparison between the two case studies, the research aims to highlight the Enabling conditions, structural barriers, and innovative practices that can facilitate the adoption of the X-Minute City model as a strategic lever for sustainable urban regeneration. The objective is twofold: first, to contribute to the scientific debate on the future of European cities; second, to propose a replicable and adaptable framework capable of guiding decision-makers, urban planners, and administrators in designing more liveable, equitable, and resilient cities.

Within the outlined framework, this research addresses three main questions:

- (1)

- How can the X-Minute City model be operationalized through multidimensional indicators that capture spatial, social, and governance dimensions of proximity?

- (2)

- How do different institutional and cultural frameworks, represented by Amsterdam and Milan, shape the implementation of proximity-based strategies?

- (3)

- To what extent can this model be transferred or adapted to other European urban contexts?

We therefore hypothesise that the effectiveness of proximity policies depends not only on spatial design but on the coherence between governance structures, mobility systems, and participatory mechanisms. The novelty here lies in treating proximity as an infrastructure of governance, measurable through contextual indicators rather than a universal time metric. The analysis is structured around four thematic pillars—proximity and accessibility to services, sustainable mobility, reuse and regeneration of spaces, civic participation and social inclusion—which together constitute the operational dimensions of the X-Minute City and provide the analytical hierarchy for the comparative assessment.

The paper is structured as follows. Following this Introduction (Section 1), Section 2 details the methodological framework adopted to operationalize the X-Minute City model, combining documentary analysis, comparative evaluation, and indicator-based assessment. Section 3 presents the comparative analysis of Amsterdam and Milan, illustrating how different governance and planning cultures interpret the proximity paradigm. Section 4 summarizes the main findings, followed by a critical discussion. Section 5 concludes with policy recommendations and future research directions aimed at enhancing the applicability and transferability of the X-Minute City framework in European urban contexts.

2. Methodological Framework for Comparative Analysis

For the purpose of this study, the cities of Milan and Amsterdam are selected as case studies not only for their European relevance but also for their heterogeneity in terms of administrative systems, planning cultures, and institutional structures [21]. This comparison allows us to explore how the proximity paradigm is adapted, reformulated, or reinterpreted depending on local contexts.

To address the research questions, a qualitative and integrated methodology was adopted, based on three main analytical dimensions: documentary analysis, systematic comparison of urban policies and practices, and the construction of a grid of multidimensional indicators. The choice of an interdisciplinary approach responds to the need to go beyond a mere spatial or technical interpretation of the city, to instead grasp the complex interrelationships between social, institutional, cultural, and territorial dynamics that influence the effectiveness of urban policies [22]. Given the diversity of data availability and planning cultures in the two national contexts, the study is explicitly designed as an exploratory, comparative and mainly qualitative analysis, in which indicators translate documentary and policy evidence into a structured but interpretative evaluation rather than into a fully standardised spatial accessibility model.

The first phase of the research involved an in-depth documentary analysis, which included consultation of a wide range of sources: scientific literature, urban plans, regulatory instruments, and strategic documents at the local, national, and European scales. This led to the construction of a theoretical and normative framework capable of clarifying the operational meaning of urban proximity and its connections with key concepts such as sustainability, resilience, sustainable mobility, and spatial justice [3,14]. The analysis also allowed us to reconstruct how urban policies in Milan and Amsterdam are already moving, even implicitly, toward forms of polycentric and integrated planning.

The second phase focused on a comparative analysis of urban policies and practices in the two contexts under study. This phase examined not only the design content of urban policies, but also the decision-making processes, the relationships between public and private actors, and the institutional mechanisms implemented to promote proximity and urban regeneration. Specifically, we examined cases of strategic interventions, co-planning experiments, social inclusion tools, and active mobility policies, such as bike lanes, 30-km zones, and extended pedestrian areas. In parallel, we reconstructed the governance networks involved in urban planning: municipalities, metropolitan authorities, neighbourhood cooperatives, environmental agencies, third-sector organizations, and organized citizens, analysing how these networks influence the implementation of the X-Minute City principles [23,24].

The third and final component of the methodology involved the construction of a grid of multidimensional indicators aimed at systematically and comparably measuring the impact of the X-Minute City model in relation to the three fundamental dimensions of urban sustainability: social, environmental, and economic [1].

Through this 3-phased methodological framework, the study aims to contribute to the scientific and technical debate on post-pandemic urban planning, providing analytical and interpretative tools to guide urban transformations towards more balanced, equitable, and sustainable forms [6]. The multilevel perspective adopted here allows for a reading of the city as a complex space, where norms, practices, cultures, and expectations intertwine, and where urban change can only emerge through a continuous negotiation between strategic visions and local adaptations [25].

Overall, the methodological design moves from (1) the construction of a conceptual and regulatory framework, to (2) a structured qualitative comparison along the four thematic pillars of the X-Minute City, and finally to (3) a synthesis in the form of an indicator grid and policy recommendations. This stepwise approach is intended to retain the richness of context-specific narratives while providing a coherent analytical structure.

The adopted methodology is structured into several phases, each with specific objectives and tools, as summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary diagram of the methodology adopted.

2.1. Document Analysis

Alongside the academic literature, regulatory and strategic documents at the European and national levels were examined, useful for understanding the public policies and regulatory constraints that influence the possibility of developing multifunctional and accessible neighbourhoods [1,26]. The corpus of documents includes, for both cities, statutory land-use and mobility plans, climate and resilience strategies, official monitoring reports, as well as independent evaluations and research studies produced by universities, think tanks and professional organisations. Documents were selected according to three main criteria: (i) substantive relevance for proximity, sustainable mobility, urban regeneration or social inclusion; (ii) formal status (approved plans and strategies or widely recognised policy frameworks); and (iii) temporal relevance, privileging materials produced in the last decade while still considering earlier documents when necessary to reconstruct longer-term trajectories. Particular attention was also paid to international case studies of urban regeneration and proximity-oriented projects. For example, in Paris, the 15-min city program integrated the distribution of local services with the creation of green spaces and cycle/pedestrian paths; In Berlin, interventions in the Pankow district have combined the reuse of abandoned industrial areas with the development of soft mobility infrastructure; similar experiences in Scandinavian cities have demonstrated how proximity can be interpreted in a polycentric manner, enhancing community engagement and social inclusion [24]. These examples have allowed us to identify replicable solutions, effective governance tools, and participatory strategies, providing a point of reference for subsequent comparative analysis.

All documents were read and coded using a thematic grid corresponding to the four pillars of the X-Minute City model (proximity and accessibility; sustainable mobility; reuse and regeneration of spaces; civic participation and social inclusion). For each city, convergences and divergences between municipal documents, academic literature and independent reports were identified, with the aim of triangulating information and avoiding reliance on single institutional narratives. Where available, quantitative information (e.g., length of cycling networks, distribution of services, socio-territorial indicators) was incorporated into the qualitative coding and used to support the subsequent indicator assessment.

The documentary analysis, therefore, provided the conceptual basis for the construction of the multidimensional indicator grid and supported the design of subsequent research phases. It allowed us to interpret the X-Minute City not only as a theoretical model, but as an operational paradigm, whose application depends on the specific regulatory, institutional, and socio-cultural characteristics of different urban contexts [22].

2.2. Comparative Evaluation Method

The comparison between the two case studies of Milan and Amsterdam is based on a structured qualitative approach that aims to explore how the X-Minute City model is interpreted, adapted, and applied in two urban contexts profoundly different in terms of urban planning culture, governance, and regulatory framework. The goal is not to produce a standardised measurement or ranking of cities, but rather to construct a critical and comparative reading capable of highlighting specific characteristics, best practices, and potential for adapting the model to different European contexts.

The method is divided into three main steps:

- Internal analysis of each city: using the developed indicator grid (Table 2), each city is analysed with respect to the four identified thematic areas (proximity and accessibility, sustainable mobility, reuse of spaces, participation and inclusion). For each area, documentary and project evidence is collected, with particular attention to planning tools, public policies, and local initiatives.

Table 2. Indicator Grid—Case Study: Amsterdam.

Table 2. Indicator Grid—Case Study: Amsterdam. - Comparison between the two contexts: the results of the two analyses are compared to highlight similarities, differences, strengths, and weaknesses. The comparison is based on a qualitative, descriptive, and reasoned analysis, rather than a rigid scoring system. This approach also allows us to consider those soft aspects (cultural, participatory, institutional) that often escape quantitative measurement but are essential for assessing the effectiveness of complex urban strategies.

- Evaluation summary: the main elements that emerged are summarized through textual diagrams and synoptic tables, which summarize the practices adopted, the enabling conditions, and the critical issues encountered for each key area. This summary is not intended to provide a final evaluation, but to identify evolutionary trajectories and potential for replication of the X-Minute City model, taking into account the structural differences between the two cities.

This comparative approach, therefore, allows us to provide a dynamic and contextualized vision of the model’s adoption, useful not only for understanding the specific cases analyzed but also for providing strategic guidance for other European cities intending to undertake similar proximity-oriented urban regeneration processes.

2.3. Indicators

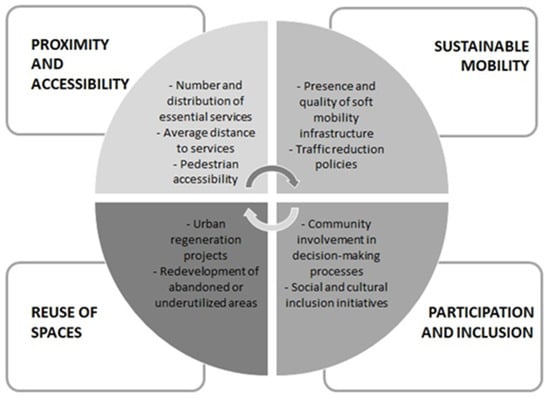

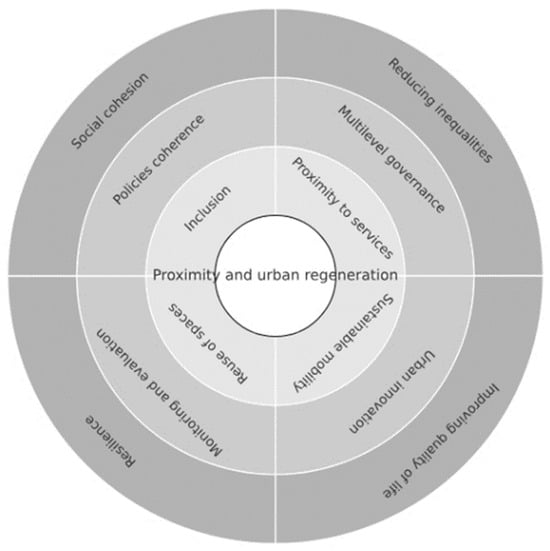

The selected indicators were organized around four key thematic areas, which form the basis for the comparative assessment between the two case studies and reflect the key dimensions of the X-Minute City model (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Indicator grid showing thematic areas and operational criteria. Source: Authors’ elaboration.

The first area concerns proximity and accessibility to essential services, a central dimension for the X-Minute City. The analysis focuses on the spatial distribution and ease of access, within a 5–20-min walking or cycling radius, to services such as education, healthcare, local retail, administrative services, and public spaces. This axis allows us to assess the degree of functional self-sufficiency of neighbourhoods and the level of integration between housing and services.

The second area concerns infrastructure and policies for sustainable mobility, with a focus on the quality and continuity of active mobility networks, the spread of public transport, and the adoption of integrated strategies to reduce private car traffic. Road safety measures, intermodality, and equitable accessibility to urban mobility are also considered.

The third area analyses the reuse and reactivation of underutilized spaces, a crucial element for sustainable urban regeneration. The study evaluates strategies for converting abandoned industrial areas, unused public buildings, urban voids, and informal spaces, observing how these are transformed into places of active proximity, capable of hosting social, cultural, or environmental functions, generating public value and strengthening local identity.

Finally, the fourth area concerns civic participation and social inclusion, a fundamental cross-cutting dimension for assessing the democratic quality of urban transformation processes. The study analyses the level of citizen involvement in decision-making, the accessibility of urban policies, and the ability of strategies to respond to the needs of vulnerable groups, such as migrants, the elderly, young people, and people with disabilities. From this perspective, the X-Minute City is not just spatial organization, but also social and spatial justice.

The integration of these four areas allows for the construction of a comprehensive evaluation model, capable of capturing the complexity of urban processes and guiding policy choices toward coherence between sustainability, operational effectiveness, and social legitimacy. Figure 1 summarizes the indicator grid, highlighting how each thematic area is translated into operational criteria for assessing the degree of implementation of the X-Minute City model. The grid organises indicators for qualitative assessment; it does not represent measured values.

Each indicator was assessed on a five-point qualitative scale ranging from very low to very high. Scores were assigned based on documentary evidence, policy analysis, and, where available, quantitative data (e.g., density of services, kilometres of cycling paths, number of co-planning initiatives). Operationally, the scale is defined as follows: 1 = Very low (no consistent policy or practice identifiable); 2 = Low (fragmented or pilot initiatives with limited coverage); 3 = Medium (significant but still partial and uneven implementation); 4 = High (well-developed policies and infrastructures, with some remaining gaps); 5 = Very high (systemic and consolidated implementation across the city). To ensure comparability between cities, all indicators were normalised to the same spatial scale (municipal level) and validated through cross-checking between at least two independent sources per indicator. The resulting assessment should therefore be read as a semi-qualitative and interpretative evaluation, rooted in documented evidence but not equivalent to a fully standardised quantitative index. It is intended as a transparent and replicable framework that can be adapted and refined in future applications, including with more detailed GIS-based and statistical analyses. The indicator grid is not intended as a normative scoring or performance-ranking tool, but as an analytical framework that enables systematic comparison across institutional, spatial, and governance dimensions. The qualitative assessment reflects documented policy orientation and implementation capacity, rather than subjective judgments of “success”.

3. Comparative Evaluation of the X-Minute City in Amsterdam and Milan

The comparative analysis between Milan and Amsterdam represents the heart of the research, as it explores how the X-Minute City model can be interpreted and applied in urban contexts with profoundly different histories, urban planning cultures, and governance. Although both cities face common challenges such as environmental sustainability, mobility, and quality of urban life, how they integrate the principles of proximity and multifunctionality of spaces varies significantly.

A crucial aspect that distinguishes the two cases is the way in which the concept of the 15-min city, and its evolution into the X-Minute City model, is received and communicated. In Milan, the 15-min city paradigm is explicitly adopted and promoted as a strategic framework for urban planning and regeneration [28]. Numerous initiatives and policies directly reference this model to guide urban development towards greater accessibility and multifunctionality at the neighbourhood scale.

In contrast, Amsterdam does not formally use the term 15-min city or X-Minute City in its planning and public communication documents, but in fact applies its founding principles. The Dutch city bases its urban strategy on an integrated vision of proximity, sustainable mobility, and regeneration, developed over decades of systemic and participatory planning [20]. In this sense, Amsterdam represents an emblematic example of how the principles of the 15-min city can be incorporated into a consolidated governance approach, without necessarily adopting the term or the rhetoric itself.

This difference in approach also reflects their different cultural and institutional traditions: Milan tends to promote an explicit and innovative narrative to foster more participatory and bottom-up urban transformation, while Amsterdam relies on more consolidated and systemic planning, with a focus on long-term tools and integration between different levels of governance [21].

The comparison between these two cities thus highlights the different ways in which the X-Minute City model can be translated into concrete policies, highlighting both the opportunities for innovation and the potential challenges associated with specific governance, regulatory, and urban planning contexts. The following sub-sections explore each case study in greater detail, followed by a direct comparison that highlights their commonalities and divergences.

3.1. Amsterdam: A Systemic Approach to Sustainability and Integrated Governance

Amsterdam is a prime example of a city that has adopted a systemic and integrated approach to sustainable urban planning, translating the principles of the X-Minute City into concrete and coordinated policies. While not explicitly referring to the term 15-min city model in any planning or policy documents, the Dutch city has developed an operating model that embodies the values of proximity, accessibility, and sustainability.

The Dutch regulatory framework is strongly oriented toward sustainability and accessibility, supported by policies that promote cycling and public transportation as alternatives to private cars. Over the years, the city has developed a strong culture of urban sustainability, in which the integration of ecological solutions and the promotion of proximity are central aspects of public policies. Local policies favour the redevelopment of brownfield sites and the reuse of underused buildings and public spaces, in line with the idea of a city that is both liveable and sustainable. Amsterdam has invested extensively in active mobility infrastructure (bike paths, pedestrian walkways) and multifunctional public spaces that allow citizens easy access to essential services. Furthermore, the city has developed advanced monitoring mechanisms, using smart technologies to collect real-time data on traffic, pollution, and accessibility to services. This data allows local authorities to continuously adapt planning policies, ensuring that citizens’ needs are consistently met [29].

The main characteristics of the Dutch model include:

- Integrated urban plans that emphasize the multifunctionality of urban spaces and the connection between housing, work, and essential services within a few minutes, supported by clear and sustainability-oriented regulations;

- Highly developed soft mobility infrastructure, with an extensive cycling network, bike-sharing services, and efficient and widespread public transport, which significantly reduces the use of private cars;

- Urban regeneration strategies that prioritize the reuse of abandoned spaces and the transformation of industrial areas into mixed neighbourhoods, integrating residential, commercial, cultural, and green spaces;

- Active citizen involvement through structured participation processes, ensuring genuine social inclusion and collaborative governance between institutions, citizens, and the private sector.

In particular, the Environmental Vision Amsterdam 2050 explicitly invokes the concept of 15 minutenstad as a long-term strategic goal, envisioning a city where services, green spaces, and public spaces are redistributed so that they are accessible exclusively by public transportation, active mobility, and pedestrian zones [27].

As shown in Table 2, Amsterdam presents a systemic model of proximity, with strong integration between planning, sustainable mobility, and participatory governance. Proximity is operational and monitored through territorial and digital indicators. The high scores attributed to Amsterdam in the indicator grid are the result of converging evidence from statutory plans, monitoring reports and independent evaluations, rather than of a single subjective judgement.

3.2. Milan: An Experimental and Participatory Approach

The Lombardy Region was one of the first European regions severely impacted by the COVID-19 health emergency, which imposed prolonged restrictions and radically changed urban habits. During the lockdown, many Milanese residents experienced daily life confined to their own neighbourhoods, strongly highlighting the importance of functional proximity as a factor in resilience and quality of urban life.

In this context, the Municipality of Milan interpreted the crisis brought by the pandemic as an opportunity to redesign the city’s spaces, times, and functions, anticipating the transition to the 15-Minute City paradigm. The Milan 2020 Adaptation Strategy [28], developed through a public call open to citizen contributions, represents one of the first systemic responses to the issue of urban proximity. It proposes a strategic reorganization of public spaces, mobility, and services to foster a new balance between private life, work, and accessibility to common goods [6].

The Milan 2020 Strategy is based on two complementary dimensions: a spatial dimension, which aims to reorganize neighbourhoods to ensure equal access to essential services and restore secondary roads to pedestrians and cyclists; and a temporal dimension, centered on a Territorial Timetable Plan aimed at desynchronizing urban time and flow, facilitating flexible work arrangements, and reducing crowding on public transport. The document, conceived during an emergency, triggered a broader rethinking of the relationship between space, time, and urban practices, catalysing a new vision of a polycentric, sustainable, and inclusive city.

The planned operational actions include strengthening local public services; expanding the time slots of public and private services; promoting digitalization and local collaboration; strengthening local health services; and supporting neighbourhood retail networks and local deliveries. In subsequent years, Milan has progressively incorporated the principles of the 15-Minute City into a polycentric system of urban policies, planning tools, and local experiments [28].

The city is configured as a dynamic laboratory, in which the vision of the X-Minute City is interpreted according to a pragmatic and adaptive approach, consistent with the morphological and institutional complexity of the Milanese context. A distinctive element of the Milanese case is the centrality of civic participation: associations, neighbourhood networks, and active citizens are involved in co-design and shared governance processes, generating bottom-up experiences of collaboration between the public and private sectors. From this perspective, proximity takes on a value not only spatial, but also relational and community-based, strengthening the link between environmental sustainability and social cohesion.

Among the most significant initiatives, namely the concrete interventions and programs through which the Municipality of Milan has tested the principles of the 15-Minute City, are:

- Milan 2020—Adaptation Strategies, cited above, promoted sustainable mobility, the redevelopment of public spaces, and the network of neighbourhood services [28].

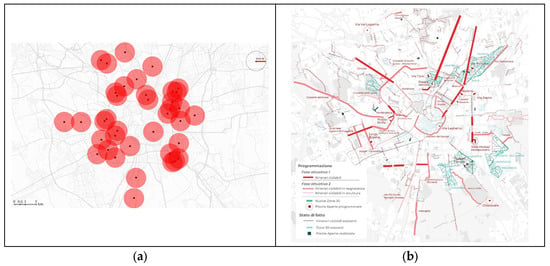

- Open Squares is a project aimed at transforming street intersections and residual spaces into meeting places and local social gatherings. The program’s objectives are: rethinking neighbourhood streets and squares as places of social interaction, vitality, and gathering; increasing the safety of citizens, pedestrians, and cyclists, with particular attention to children, the elderly, and people with disabilities; repurposing existing public spaces through low-cost, highly participatory urban furnishing and decoration projects; fostering collaboration between citizens and public administration, promoting the shared management of common goods (Figure 2a).

Figure 2. Two main projects and plans in Milan. (a): Proposals for ‘Open Squares’ in Milan. Source: The report ‘Piazze Aperte: A Public Space Program for Milan. Retrieved from: https://www.comune.milano.it/aree-tematiche/quartieri/piano-quartieri/piazze-aperte (accessed on 20 November 2025). (b): Planned intervention for walkability and cyclability in the city of Milan. Source. Comune di Milano, 2020. Retrieved from: https://www.sporteimpianti.it/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/Milano-Strade-Aperte.pdf (accessed on 20 November 2025).

Figure 2. Two main projects and plans in Milan. (a): Proposals for ‘Open Squares’ in Milan. Source: The report ‘Piazze Aperte: A Public Space Program for Milan. Retrieved from: https://www.comune.milano.it/aree-tematiche/quartieri/piano-quartieri/piazze-aperte (accessed on 20 November 2025). (b): Planned intervention for walkability and cyclability in the city of Milan. Source. Comune di Milano, 2020. Retrieved from: https://www.sporteimpianti.it/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/Milano-Strade-Aperte.pdf (accessed on 20 November 2025). - Open Streets is a tactical urbanism program aimed at temporarily converting urban arteries into pedestrian and cycle areas, promotes safety, sustainability, and shared use of public space. The project accelerates the urban regeneration already underway before the COVID-19 pandemic, with pilot interventions in the Lazzaretto and Isola neighbourhoods, where streets were temporarily pedestrianized, sidewalks widened, 30-km zones established, existing cycle paths were connected, and public spaces were freed up for outdoor living; (Figure 2b). Both images illustrate tactical interventions that operationalise proximity and active mobility at the neighbourhood scale.

- Public Space. Design Guidelines, a manual produced by the City of Milan together with AMAT, NACTO, and Bloomberg Associates, was designed with the 15-Minute City vision in mind to guide the transformation of mobility and the use of public spaces. The document clarifies innovative interventions, such as cycle paths, tactical urban planning, bicycle parking management, and urban drainage systems.

- The call for proposals Mi15—Spaces and services for a 15-min Milan [20] supports local projects aimed at improving access to essential services and encouraging socio-cultural activities with strong local roots.

- Resilient Neighbourhoods is a program aimed at strengthening social cohesion and urban sustainability through public space regeneration, support for local communities, and the promotion of sustainable mobility and local services [20].

- BikeMi is an initiative to strengthen the bike-sharing system to improve neighbourhood connectivity and reduce private car use by integrating cycling and access to urban services within 15 min.

- Urban Gardens and Green Spaces is a project that allows for the recovery of abandoned or degraded areas. The assignment of the area where a shared garden can be created takes place through the signing of an agreement between a non-profit association and the Municipality in which the space is located. The agreement has a minimum duration of one year and a maximum of three years.

These experiences, summarized in Table 3, combine urban regeneration, sustainable mobility, and local services, contributing to the construction of a more accessible, liveable, and collaborative city.

Table 3.

Main initiatives in Milan with the X-Minute City model.

Alongside these experimental initiatives, Milan has developed a series of structural planning and governance strategies that consolidate the proximity paradigm from a long-term perspective. Among the main ones are:

- The Milan 2030 Land Use Plan (PGT), which incorporates the principles of proximity and multifunctionality, while adapting its application to existing economic and regulatory constraints; the Plan places public space at the centre of the city’s urban regeneration process.

- The Sustainable Urban Mobility Plan (SUMP) aims to integrate public transportation, cycling, and pedestrianization, promoting a structural reduction in reliance on private cars. The Plan aims to ensure high accessibility to the city by promoting active mobility and restoring public spaces to the shared use of all users, ensuring adequate health, safety, and environmental quality.

- The Air and Climate Plan, adopted in 2020, is a tool for integrated actions aimed at improving air quality, mitigating climate-altering emissions, adapting to the effects of climate change, and pursuing social equity and health protection goals.

- The Neighbourhood Plan, which emphasizes the multicentric and micro-identity nature of the city as an essential element for its transformation.

- Urban regeneration projects in the Bovisa, Lambrate, and Giambellino neighbourhoods, where the redevelopment of abandoned industrial areas fosters the creation of multifunctional public spaces and local services.

- Active mobility initiatives, with the expansion of the cycle path network, the expansion of limited traffic zones, and awareness campaigns on the use of sustainable transport.

- Local participatory processes, promoted by civic networks and neighbourhood associations, aim to influence urban planning decisions through co-design and shared governance practices.

Despite the progress made, the city of Milan still presents significant socio-territorial inequalities in the distribution of local services and infrastructure.

A study conducted by Scenari Immobiliari [30] highlights how peripheral and semi-central areas are disadvantaged in terms of accessibility to services within 15 min, while central and para-central neighbourhoods exhibit greater functional density and a higher level of accessibility to educational, cultural, and commercial functions. This geography of proximity reflects the dynamics of the real estate market and the historical concentration of economic opportunities, confirming the close relationship between land value and the provision of urban services.

In support of this evidence, Milan’s indicator grid (Table 4) offers a multidimensional interpretation of the city in relation to the four main areas of implementation of the X-Minute City: proximity and accessibility to services, sustainable mobility, reuse and regeneration of spaces, civic participation, and social inclusion.

Table 4.

Indicator grid—case study: Milan.

The analysis reveals a transitional framework, characterized by widespread but not yet fully systemic experimentation. In terms of proximity and accessibility to services, Milan performs well in the historic centre and semi-central neighbourhoods, supported by plans and tools such as the Air and Climate Plan and the PGT Milano 2030. However, functional gaps persist in the suburbs, where distance from essential services and the lack of neighbourhood public spaces reduce daily usability. Regarding sustainable mobility, the Open Streets program and the expansion of the cycling network have contributed to a progressive expansion of active routes, but administrative fragmentation and infrastructural discontinuity hinder full modal integration. The reuse and regeneration of spaces is experiencing lively experimentation, from the railway yards to BASE Milano, in which the third sector and civic networks play a growing role, although the processes remain slow and complex from a management perspective. In terms of civic participation and social inclusion, Milan presents a network of dynamic local practices (Neighbourhood Workshops, Collaboration Agreements), which, however, often remain episodic and not yet integrated into a stable, multilevel governance system.

The grid summary confirms that Milan is in a phase of experimentation and transition toward the X-Minute City. Proximity policies are fragmented but innovative, supported by bottom-up participatory processes and a growing institutional commitment to promoting spatial equity and environmental sustainability [6]. Overall, the city is configured as a laboratory of proximity, in which space, time, and social relations represent the three main axes of urban transformation.

However, structural critical issues remain: the fragmentation of metropolitan governance, the uneven distribution of services, and the still unequal participation of social groups. Thus, there is a need for strengthening inter-institutional coordination and the adoption of shared monitoring metrics. Addressing these challenges will be essential to consolidate Milan as a model of an adaptive, equitable, and resilient city, capable of transforming the paradigm of proximity into a real opportunity for collective well-being and urban cohesion. For this reason, the medium and low scores assigned to some thematic areas in Table 4 should therefore be read as indicative of a transitional condition, where innovative practices coexist with persistent structural constraints.

3.3. Comparison of the Two Cities

The comparison between Milan and Amsterdam highlights two profoundly different approaches to implementing the X-Minute City model. The differences concern not only the maturity of urban policies or spatial organization, but are also reflected primarily in regulatory frameworks, governance models, and the degree of strategic integration between different planning levels.

Amsterdam represents a consolidated benchmark for integrated and sustainability-oriented urban planning. A long tradition of territorial governance, supported by a clear regulatory system and strong institutional capacity, has enabled the coherent integration of the principles of functional proximity, sustainable mobility, and inclusive urban regeneration [31].

Dutch urban policies operate within a framework of vertical coherence, between the national, regional, and local levels, which ensures the consistent application of sustainability, accessibility, and quality of life objectives. In this context, proximity is not just a planning objective, but a daily urban practice, enabled by a solid infrastructure system and institutionalized participatory mechanisms.

Milan, by contrast, is in a more experimental and adaptive phase. Despite having launched numerous urban regeneration and sustainable mobility initiatives, the city still lacks a unified strategic vision capable of fully integrating the proximity paradigm at the metropolitan scale. The complex and multilevel Italian regulatory framework makes it difficult to build truly coordinated urban governance. However, Milan stands out for the vitality of its social innovation processes, with bottom-up practices and local experiments that actively involve citizens, neighbourhood networks, and third-sector organisations. This approach, though heterogeneous, represents a form of local adaptation of the model, capable of enhancing the participatory and relational dimension of the city.

In summary, the comparison between the two cities confirms that the effectiveness of the X-Minute City model depends on the ability to mediate between strategic vision and local adaptability. Sustainable urban regeneration requires a dynamic balance between centralized governance and widespread participation, as well as regulatory coherence and operational flexibility. In this sense, the Dutch experience demonstrates the value of a systemic strategic design, while the Milanese experience highlights the power of social innovation and community experimentation [32].

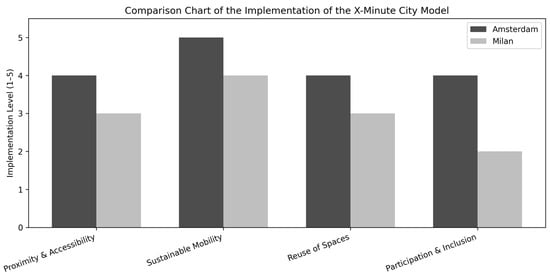

To complete the comparison, a multidimensional evaluation grid was developed that allows us to qualitatively and interpretatively measure the degree of implementation of the X-Minute City model in the two cities. The evaluation is based on the four strategic areas deemed fundamental to the model’s functioning, including proximity to services, sustainable mobility, reuse of underutilized spaces, and civic participation and social inclusion. Each area has been assigned a level of development on the same five-point qualitative implementation scale (Very low, Low, Medium, High, Very high) described in Section 2.3. The analysis is based on an examination of planning documents, a comparison of policy instruments, and an observation of ongoing urban practices.

It is important to note that the observed differences between Amsterdam and Milan are not solely attributable to governance arrangements. They are also deeply influenced by structural factors such as urban morphology, historical development trajectories, institutional continuity, and welfare regimes. Amsterdam benefits from a historically compact and polycentric urban structure, supported by long-term planning stability, whereas Milan’s proximity policies represent a more recent, policy-driven effort to retrofit accessibility within a more fragmented and socio-spatially uneven urban fabric.

Figure 3 summarizes the results: Amsterdam shows high levels in all areas, confirming a systemic and coherent approach, while Milan presents more heterogeneous results, with strengths in sustainable mobility and weaknesses in proximity to services, space reuse, and civic participation. The figure thus highlights the tension between a consolidated and uniform model and an experimental and adaptive approach, underscoring the importance of combining long-term strategies with local initiatives to promote equity, sustainability, and urban well-being. It is important to note that Figure 3 visualises interpretative scores derived from the indicator grid and should be read as a heuristic representation of relative strengths and weaknesses rather than as a precise quantitative measurement.

Figure 3.

Implementation levels of the X-Minute City model in Milan and Amsterdam. Source: Authors’ elaboration.

4. Findings and Discussion: Interpreting the X-Minute City

The comparative analysis between Amsterdam and Milan highlights very different approaches to adopting the X-Minute City paradigm. Amsterdam stands out for its high level of maturity in all four strategic areas of the model. The city combines high accessibility to services with well-integrated sustainable mobility and systematic urban regeneration processes. The continuous cycling network, over 850 km, combined with efficient public transport, ensures rapid and safe travel, while GIS tools and monitoring systems support urban planning and resource management.

The reuse of abandoned spaces for cultural, residential, and commercial purposes, such as Buiksloterham and NDSM Wharf, reflects a circular strategy that integrates urban innovation and social cohesion [33]. Participatory processes are formalised and institutionalized, ensuring citizen involvement and the inclusion of vulnerable groups. As highlighted in Table 5, Amsterdam presents a systemic and coherent approach across all strategic areas: from proximity to services to sustainable mobility, the reuse of spaces, and civic participation.

Table 5.

Summary of comparative results and implications of the X-Minute City model.

Milan, on the other hand, demonstrates a more fragmented and experimental approach. Proximity to services is high in the city centre, but decreases in the suburbs, where pilot initiatives seek to rebalance the distribution of services. Sustainable mobility is expanding thanks to cycling networks, limited traffic zones, and projects such as Strade Aperte (Open Streets), but integration between different means of transport and urban governance remains less structured [26].

The reuse of spaces also follows a discontinuous path: projects such as Scali Milano and Cascina Nascosta demonstrate creativity and social innovation but lack strategic coordination at the metropolitan scale [34]. Civic participation, while growing thanks to neighbourhood workshops and Collaboration Agreements, remains episodic and unsystematic [1]. Table 5 shows a clear overview of these strengths and weaknesses, showing how Milan boasts local excellence but lacks a systemic approach and participatory governance.

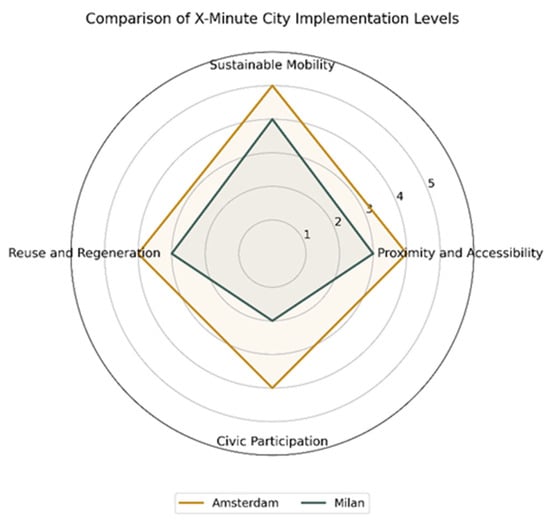

The radar representation in Figure 4, on the other hand, immediately captures the overall profile of the two cities. Amsterdam achieves high and uniform values across all strategic areas, confirming the model’s ability to function in an integrated manner. Milan displays a more uneven profile, with localized strengths but weaknesses at the metropolitan scale and in civic participation. These findings highlight how the replicability of the X-Minute City model requires careful adaptation to the institutional, spatial, and cultural contexts of individual cities.

Figure 4.

Comparative radar of the X-Minute City in Amsterdam and Milan. Source: Authors’ elaboration.

In summary, the findings underscore that the effectiveness of the X-Minute City depends on the combination of infrastructure, governance, and civic participation. Amsterdam represents an advanced example of systemic integration between services, sustainable mobility, reuse of urban spaces, and social inclusion, while Milan demonstrates how a bottom-up and experimental approach can foster innovation and resilience, while requiring more coherent strategies. Table 5 details the operational characteristics of each city, while Figure 4 a radar diagram based on qualitative scores derived from the five-point implementation scale and should be interpreted as an illustrative comparison, not as an exact statistical measurement.

The comparative analysis highlights that the success of implementing the X-Minute City model depends not solely on the intensity of interventions in each area, but on the ability to integrate infrastructure, governance, and civic participation. Amsterdam represents a case in which systemic planning, coordinated resource management, and formalized participatory processes create a resilient and replicable urban ecosystem. The continuity between sustainable mobility, accessibility to services, and the reuse of abandoned spaces suggests that the adoption of circular and data-driven strategies facilitates social cohesion and urban innovation.

Milan, on the other hand, demonstrates how innovation can emerge even in fragmented contexts, thanks to local experiments and bottom-up initiatives. However, the discrepancies between the centre and the periphery, combined with still episodic participatory governance, indicate that without strategic coordination, best practices risk remaining isolated. This highlights the need for more integrated planning tools, capable of harmonizing local projects and metropolitan visions, and of consolidating participatory processes that systematically involve citizens and institutional stakeholders [26].

From the perspective of urban regeneration theory, these results suggest that the X-Minute City can be understood as a specific configuration of broader processes of spatial restructuring and socio-ecological transition. In Amsterdam, proximity-oriented policies contribute to a systemic redistribution of functions and public spaces, supporting compactness, mixed-use development and circular land-use practices. In Milan, proximity emerges through more incremental forms of reuse and tactical interventions, often led by civic actors, which nonetheless open up opportunities for rebalancing long-standing central–peripheral inequalities. In both cases, the X-Minute City framework provides a lens through which debates on the right to the city, spatial justice and climate-neutral urbanism can be operationalised in concrete redevelopment strategies and governance arrangements.

Another aspect concerns the adaptability of the X-Minute City model to different urban contexts. Amsterdam’s experience shows how replicability is favoured by stable institutional contexts and strong administrative capacity, while Milan highlights the importance of flexibility and experimentation in generating urban innovation. This suggests that cities intending to adopt the paradigm must balance top-down and bottom-up approaches, calibrating strategies based on available resources, urban density, and local participatory culture.

The discussion here emphasises how the X-Minute City model requires not only sectoral interventions but an integrated and adaptive vision capable of combining technological innovation, urban regeneration strategies, and participatory governance, taking into account local characteristics and metropolitan-scale possibilities. The indicator-based framework proposed in this study is intended as a first step in this direction: it systematises policy and planning evidence across the four pillars of proximity, mobility, reuse and participation, while remaining open to enrichment through more detailed spatial and socio-economic analyses.

It is worth highlighting that Amsterdam benefits from a historically compact, polycentric, and network-based urban structure that naturally supports proximity. On the other hand, Milan presents a more fragmented morphology, shaped by post-industrial expansion, railway infrastructures, and socio-economic polarization. Moreover, Amsterdam’s proximity outcomes are not solely the result of recent policies, they are strongly supported by long-term planning culture, compact morphology, and institutional continuity. Conversely, Milan’s case is framed as a policy-driven attempt to retrofit proximity within a more complex and uneven spatial structure. This contrast strengthens the comparative value of the study and reinforces the argument that the X-Minute City should be understood as a context-dependent governance framework, not a one-size-fits-all spatial model.

5. Conclusions and Policy Implications

The comparative findings enrich the broader debate on the 15-min city as a driver of post-carbon and post-growth urbanism [35,36]. By analysing two contrasting planning cultures, the study demonstrates that the X-Minute City is less a universal design recipe and more a governance framework for proximity, contingent upon institutional capacity and civic culture. This follows with recent calls for integrating circular economy principles [33] and digital governance into proximity-based urbanism. Therefore, the presented framework is intended primarily as a diagnostic and monitoring tool to support proximity-oriented urban regeneration strategies across diverse European contexts.

Amsterdam confirms its position as a mature case of systemic implementation of the model, supported by stable multilevel governance, a coherent regulatory framework, and a consolidated tradition of integrated planning. The city demonstrates how proximity can function as a permanent civic infrastructure, capable of combining sustainable mobility, social inclusion, and environmental quality [19,37].

Milan, by contrast, follows a more experimental and incremental approach, in which the X-Minute City model translates into widespread practices of urban and social innovation. Local regeneration initiatives, participatory workshops, and the adaptive reuse of abandoned spaces outline a transition toward a bottom-up, local city of proximity, where collaboration between citizens, institutions, and local networks becomes crucial for change [38]. Despite structural limitations and fragmented governance, Milan shows signs of growing capacity to promote more inclusive and territorially balanced urban policies.

The main contribution of this research lies in the transformation of the X-Minute City from a conceptual vision to an operational analysis tool, through a grid of multidimensional indicators that allows measuring the degree of implementation of the model in different urban contexts. This methodology offers a replicable approach that integrates spatial, social, and governance aspects, representing a significant advance in the literature [22]. By explicitly linking proximity to questions of spatial justice, land-use restructuring and socio-ecological transition, the framework also contributes to bridging proximity-based planning with debates on urban regeneration and the right to the city.

In summary, the study provides an empirical and theoretical basis for guiding future urban regeneration strategies, highlighting how the model’s success depends on the ability to build synergies between local policies, collaborative governance, and civic participation. Table 5 summarizes the comparative results and operational implications, offering a quick reference for understanding how differences between urban contexts influence the effectiveness of the X-Minute City.

5.1. Policy Recommendations

The research findings highlight the need to transform the X-Minute City from an urban ideal into an institutional and strategic architecture of contemporary European planning. This requires a profound rethinking of the relationship between space, citizenship, and governance, in which proximity is recognized as a guiding principle of public action [37].

A first step is to integrate the concept of proximity into urban and regional planning, translating it into measurable and verifiable accessibility criteria. Proximity must be conceived as an urban right, guaranteeing every citizen access to services, green spaces, sustainable mobility, and participation opportunities within a fair timeframe.

At the same time, it is essential to build multilevel governance capable of overcoming decision-making fragmentation and promoting synergies between institutional actors, local communities, and the private sector. The case of Amsterdam demonstrates how interinstitutional cooperation and coordination between urban, environmental, and social policies are crucial to ensuring the effectiveness and continuity of the city’s transformation [34,39].

The adaptive regeneration of underused spaces represents another strategic dimension. These places, if reinterpreted as shared resources, can become catalysts for proximity and cohesion, hosting mixed functions and community services. To achieve this goal, flexible reuse policies must be promoted, supported by tax incentives, innovative financial instruments, and public–private partnerships.

Sustainable mobility and civic participation are two interconnected dimensions of the paradigm. Investing in active mobility infrastructure and integrated transport systems is essential to ensuring accessibility and reducing environmental impact [40]. Likewise, citizen participation in decision-making processes must become a structural component of planning to ensure inclusiveness, transparency, and a sense of belonging.

Finally, research emphasizes the importance of developing dynamic monitoring and evaluation tools, based on updated territorial indicators and open data, to measure the real impact of proximity policies. From this perspective, the X-Minute City can serve as an operational framework for integrated urban policies capable of guiding the ecological and social transition of European cities [41]. Table 6 summarizes the proposed policy framework across local, metropolitan, national, and EU scales. While this study focuses on two large metropolitan contexts, many of the policy recommendations are also relevant for small and medium-sized cities. In smaller urban systems, basic forms of everyday proximity are often already present, but they tend to remain implicit and are not systematically monitored or linked to regeneration strategies. Applying the X-Minute City framework in such contexts would mean tailoring time thresholds and service bundles to smaller catchment areas, strengthening local governance capacities and making explicit the contribution of proximity to demographic resilience, local economies and ecological transition. At the same time, the smaller scale can facilitate more direct participation and experimentation, provided that adequate institutional support and financial tools are available.

Table 6.

Operational recommendations and governance levels.

While this study focuses on two large European metropolitan contexts, the X-Minute City framework is conceived as scalable and adaptable. In medium-sized cities and smaller urban systems, everyday proximity is often already present but remains implicit and weakly institutionalised. Applying the framework in such contexts would require recalibrating time thresholds and service bundles, while strengthening local governance capacities and participatory mechanisms. Similarly, in non-European planning systems, the framework can function as a diagnostic and governance-oriented tool rather than as a prescriptive spatial model.

5.2. Future Research Perspectives

The main contribution of this research is the proposal of a replicable and adaptable methodological framework capable of assessing how cities translate the concept of proximity into concrete policies and practices. This approach opens up new theoretical and applicative perspectives, in line with the European objectives of sustainability, climate neutrality, and social inclusion [42].

One of the most promising developments concerns the extension of the indicator grid to different urban contexts, both in Europe and globally, to test its transferability and scalability. At the same time, it will be important to further explore the role of digital technologies and urban data in proximity governance, exploring how urban analytics tools and participatory platforms can strengthen the effectiveness of urban policies and improve citizen engagement.

Equally relevant is the investigation of the intersection between proximity, spatial justice, and ecological transition. In this context, the X-Minute City model can be a tool for reducing territorial inequalities, fostering community resilience, and supporting urban strategies geared toward environmental, social, and cultural sustainability.

Figure 5 summarizes the research’s final framework, presenting the proximity city as an operational infrastructure for urban regeneration. At its core is the idea of the city as a space where proximity becomes a guiding principle, around which the model’s four pillars are structured—accessible services, sustainable mobility, adaptive reuse of spaces, and civic participation—and the enabling conditions that ensure its effectiveness, such as multilevel governance, technological innovation, and coherence between local, national, and European policies [41]. The outer band of the diagram highlights the expected impacts, from reducing spatial inequalities to improving the quality of urban life, from resilience and climate neutrality to social cohesion and a sense of belonging [42]. The diagram schematically organises the four pillars, enabling conditions, and expected impacts of the X-Minute City model. It is a conceptual visualisation and does not represent empirical data.

Figure 5.

Multilevel circular diagram illustrating the final framework of the research. Source: Authors’ elaboration.

This research confirms that proximity is not just a spatial dimension, but a principle of urban justice and social cohesion, capable of guiding the transformation of cities towards more sustainable, inclusive, and resilient models. The proposed framework thus provides a concrete reference for future urban regeneration studies and practices, offering an operational and cultural perspective for 21st-century European cities.

A limitation of this study lies in the primarily qualitative assessment of indicators. Future research could apply GIS-based accessibility modelling and participatory mapping to quantify the proximity gap between neighbourhoods. Furthermore, comparative longitudinal studies could assess how the X-Minute City evolves over time in response to policy and behavioural change. In this sense, the indicator grid developed here should be seen as a first, analytically transparent step that can be progressively refined and complemented with more detailed spatial, statistical and participatory methodologies, including in small and medium-sized cities and in non-European contexts.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.P. and M.A.; methodology, F.P.; formal analysis, F.P.; investigation, M.A.; resources, F.P. and M.A.; data curation F.P. and M.A.; writing—original draft preparation F.P.; writing—review and editing, M.A.; visualization, M.A.; supervision, F.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The dataset is available on request from the authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- UN-Habitat. World Cities Report 2020: The Value of Sustainable Urbanisation; United Nations Human Settlements Programme: Nairobi, Kenya, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- OECD; European Commission. Cities in the World: A New Perspective on Urbanisation; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Moreno, C.; Allam, Z.; Chabaud, D.; Gall, C.; Pratlong, F. Introducing the “15-Minute City”: Sustainability, Resilience and Place Identity in Future Post-Pandemic Cities. Smart Cities 2021, 4, 93–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gehl, J. Cities for People; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Mehaffy, M.W.; Salingaros, N.A. Design for a Living Planet: Settlement, Science and the Human Future; Sustasis Press: Portland, OR, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Pinto, F.; Akhavan, M. Scenarios for a Post-Pandemic City: Urban Planning Strategies and Challenges of Making “Milan 15-Minutes City”. Transp. Res. Procedia 2022, 60, 370–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bibri, S.E. A Novel Model for Data-Driven Smart Sustainable Cities of the Future: The Institutional Transformations Required for Balancing and Advancing the Three Goals of Sustainability. Energy Inform. 2021, 4, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casarin, G.; MacLeavy, J.; Manley, D. Rethinking Urban Utopianism: The Fallacy of Social Mix in the 15-Minute City. Urban Stud. 2023, 60, 3167–3186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Costa Braga França, J.G.; de Oliveira, I.K.; de Oliveira, L.K. Spatial Accessibility of Bakeries and Supermarkets in Belo Horizonte, Brazil. J. Geogr. Res. 2022, 5, 16–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caselli, B. From Urban Planning Techniques to 15-Minute Neighbourhoods. A Theoretical Framework and GIS-Based Analysis of Pedestrian Accessibility to Public Services. Eur. Transp./Trasp. Eur. 2021, 85, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vale, D.; Lopes, A.S. Accessibility Inequality Across Europe: A Comparison of 15-Minute Pedestrian Accessibility in Cities With 100,000 or More Inhabitants. npj Urban Sustain. 2023, 3, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Zhen, F.; Kong, Y.; Lobsang, T.; Zou, S. Towards a 15-Minute City: A Network-Based Evaluation Framework. Environ. Plan. B Urban Anal. City Sci. 2022, 50, 500–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colaço, R.; de Abreu e Silva, J. Does the 15-Minute City Promote Sustainable Travel? Quantifying the 15-Minute City and Assessing Its Impact on Individual Motorized Travel, Active Travel, Public Transit Ridership and CO2 Emissions. Netw. Spat. Econ. 2025, 25, 139–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Luo, S. A Study on the Current Situation of Public Service Facilities’ Layout from the Perspective of 15-Minute Communities—Taking Chengdu of Sichuan Province as an Example. Land 2024, 13, 1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khavarian-Garmsir, A.R.; Sharifi, A.; Abadi, M.H.H.; Moradi, Z. From Garden City to 15-Minute City: A Historical Perspective and Critical Assessment. Land 2023, 12, 512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pozoukidou, G.; Angelidou, M. Urban Planning in the 15-Minute City: Revisited Under Sustainable and Smart City Developments Until 2030. Smart Cities 2022, 5, 1356–1375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lefebvre, H. Writings on Cities; Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Pinto, F.; Sufineyestani, M. Key Characteristics of an Age-Friendly Neighbourhood. TeMA J. Land Use Mobil. Environ. 2018, 117–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gemeente Amsterdam. Amsterdam Circular Strategy 2020–2025; Gemeente Amsterdam: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Comune di Milano. Piano di Governo del Territorio—Milano 2030; Comune di Milano.: Milan, Italy, 2022.

- Bertolini, L.; Le Clercq, F. Urban Development without More Mobility by Car? Lessons from Amsterdam, a Multimodal Urban Region. Environ. Plan. A 2003, 35, 575–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talen, E. City Rules: How Regulations Affect Urban Form; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Pierre, J. The Politics of Urban Governance; Palgrave Macmillan: Basingstoke, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Foster, S.R.; Iaione, C. The City as a Commons. Yale Law Policy Rev. 2016, 34, 281–349. [Google Scholar]

- Healey, P. Urban Complexity and Spatial Strategies: Towards a Relational Planning for Our Times; Routledge: London, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Vale, D.S. Transit-Oriented Development, Integration of Land Use and Transport, and Pedestrian Accessibility: Combining Node-Place Model with Pedestrian Shed Ratio to Evaluate and Classify Station Areas in Lisbon. J. Transp. Geogr. 2015, 45, 70–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gemeente Amsterdam. A New Vision for a Growing City; Gemeente Amsterdam: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Comune di Milano. Milano 2020: Strategia Di Adattamento; Comune di Milano.: Milan, Italy, 2020.

- Gemeente Amsterdam. Zero-Emission Mobility in Amsterdam: Implementation Agenda 2023–2026; Gemeente Amsterdam: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Valtolina, G. Milano, La Città Dei «Quindici Minuti»: Ecco La Raggiungibilità Dei Servizi Secondo i Quartieri. Corr. Della Sera 2020. Available online: https://milano.corriere.it/notizie/cronaca/20_ottobre_02/0203-milano-acorriere-web-milano-cdcdce98-047a-11eb-952f-bb62f0bc5655.shtml (accessed on 20 November 2025).

- OECD. The Governance of Land Use in the Netherlands: The Case of Amsterdam; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Moreno, C. The 15-Minute City: A Solution to Saving Our Time and Our Planet; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2024; ISBN 978-1-394-22814-0. [Google Scholar]

- Calisto Friant, M.; Reid, K.; Boesler, P.; Vermeulen, W.J.V.; Salomone, R. Sustainable Circular Cities? Analysing Urban Circular Economy Policies in Amsterdam, Glasgow, and Copenhagen. Local Environ. 2023, 28, 1331–1369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bovaird, T.; Loeffler, E. From Engagement to Co-Production: The Contribution of Users and Communities to Outcomes and Public Value. Voluntas 2012, 23, 1119–1138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruno, M.; Monteiro Melo, H.P.; Campanelli, B.; Loreto, V. A Universal Framework for Inclusive 15-Minute Cities. Nat. Cities 2024, 1, 633–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixeira, F.; Silva, C.; Seisenberger, S.; Büttner, B.; McCormick, B.; Papa, E.; Cao, M. Classifying 15-Minute Cities: A Review of Worldwide Practices. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2024, 189, 104234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajer, M.; Dassen, T. Smart About Cities: Visualising the Challenge for 21st Century Urbanism; PBL Netherlands Environmental Assessment Agency: Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Comune di Milano. Mi15—Spazi e Servizi per Una Milano a 15 Minuti; Comune di Milano: Milan, Italy, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Gemeente Amsterdam. Omgevingsvisie Amsterdam 2050: Environmental Vision Amsterdam 2050; Gemeente Amsterdam: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Abdullahi, U.; Adnan, A. Sustainable Urban Mobility: Lessons from European Cities. Glob. J. Eng. Technol. Adv. 2024, 21, 157–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. Building Better Cities for a Green and Inclusive Recovery; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- C40 Cities. 15-Minute Cities: A Toolkit for City Leaders; C40 Cities Climate Leadership Group: London, UK, 2022; Available online: https://www.c40knowledgehub.org/s/topic/0TO1Q000000UEx5WAG/15minute-cities (accessed on 15 September 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.