Abstract

Understanding cultivated land use transition (CLUT) requires analytical frameworks capable of capturing the interconnected changes in production inputs, land use structure, and multifunctional outcomes. However, existing CLUT studies often rely on fragmented metrics that separately examine dominant or recessive transitions, limiting their ability to reveal the internal mechanisms of land use transition. Therefore, this study developed an integrated “factor-structure-function” analytical framework based on the theory of induced technological innovation. An evaluation system was constructed to operationalize the proposed framework, and Zhejiang Province—a rapidly urbanizing region in southeastern China, was selected as an empirical validation case to demonstrate its analytical value. The results showed that the integrated framework not only identified temporal and spatial patterns of CLUT, but also revealed internal trade-offs and synergies among factor substitution, structural reconfiguration, and functional transition that were not detectable using conventional CLUT metrics. In particular, the framework highlighted unique regional transition pathways driven by different modes of factor substitution. By connecting factor inputs, output structures, and land functions within the integrated framework, this study offers a practical tool for diagnosing CLUT and serves as a methodological guide for future CLUT research in rapidly urbanizing regions.

1. Introduction

Since the turn of the 21st century, the acceleration of urbanization and industrialization has led to unprecedented global land use/land cover changes. The spatial expansion and contraction of different land use types and the transformation of landscape patterns have represented the most direct spatio-temporal dynamics of human-dominated land use transition processes [1,2]. To scientifically elucidate these spatio-temporal relationships, research on land use transition (LUT) has attracted growing academic attention [3,4]. The LUT concept originated from the “Forest Transition” hypothesis and the study of national land use morphological changes, which refers to the spatial pattern of land use types affected by the regional economy to form a general pattern of expansion or contraction [5,6]. With ongoing scholarly research, LUT has proven instrumental in uncovering how land use in specific regions evolves during the course of socio-economic development, such as in landscape configuration, structural composition, management practices, and functional services. These insights provide a solid theoretical basis and evidence-based policy support for sustainable land resource management [7,8,9,10].

Cultivated land is an indispensable natural resource that supports human survival, ecological support, and agricultural activities. It is worth emphasizing that cultivated land is not only the most vulnerable type of land use in rural systems, but its utilization mode is also highly correlated with the stage of socio-economic development [11,12,13], making cultivated land use transition (CLUT) a focal issue of common concern to academic circles and policymakers. In fact, CLUT is a core component of LUT, extending LUT concepts to describe long-term turning points in cultivated land use morphology [14,15]. Most of the existing mainstream research on CLUT proceeds from two core perspectives, namely cultivated land use dominant transition (CLDT) and cultivated land use recessive transition (CLRT) [16]. CLDT involves changes in the quantitative structure and spatial pattern of cultivated land, while CLRT refers to changes in characteristics that are not easily directly observable in the short term, such as soil quality, property rights, management models, stakeholder attributes, and ecosystem services. Research findings based on these two perspectives have laid a solid foundation for understanding CLUT. With the deepening of CLUT research, scholars have come to recognize that CLDT and CLRT are not entirely independent, as their interaction has driven the transition in cultivated land utilization [3,7,17,18]. An increasing number of studies have begun to incorporate quantitative indicators of both dominant (represented by the spatial morphology of cultivated land, e.g., land use conversion, grain planting ratio [14], landscape pattern [19], fragmentation index [20]) and recessive perspectives (represented by the ecological and economic functions of cultivated land, e.g., agricultural production cost [21], economic efficiency [22], environmental carrying capacity [23], ecosystem services [24]) into integrated frameworks to comprehensively characterize the land use transition process [14,17,24,25]. However, two key challenges remain alongside these insights.

Firstly, most studies still treat CLDT and CLRT as independent research objects, failing to capture their inherent interactive and mutually reinforcing relationships [17,18]. For example, changes in cultivated land factor inputs and management practices not only significantly alter the quantity and structure of cultivated land output, but also affect the trade-offs and synergies among the various ecosystem services provided by cultivated land [26,27,28,29]. Analyzing these two transitions in isolation, thus, results in an incomplete and fragmented understanding of CLUT dynamics, overlooking the systemic nature of the transition process. Secondly, the quantitative characterization of CLUT remains inadequate at present. Most studies rely on qualitative descriptions or quantification based on a single indicator, lacking a comprehensive evaluation system capable of fully capturing the multi-dimensional and multi-layered nature of the transition process, which greatly limits the accuracy of spatiotemporal analysis of CLUT. These gaps highlight the need for a more integrated framework to fully understand CLUT’s multi-dimensional changes and interrelationships.

From a theoretical perspective, the theory of induced technological innovation provides an important lens for understanding CLUT dynamics. As relative scarcity and prices of production factors change, agricultural systems tend to substitute scarce inputs with more abundant alternatives, triggering subsequent adjustments in land use structure and functional outcomes [30,31]. This mechanism implies that cultivated land use transition is not a collection of isolated changes, but a connected process linking factor inputs, structural configuration, and multifunctional performance. However, few existing CLUT studies have translated this theoretical logic into an integrated analytical framework capable of systematically organizing indicators and diagnosing transition pathways. To address this gap, this study developed an integrated “factor–structure–function” analytical framework for cultivated land use transition. The framework conceptualized CLUT as a process driven by induced factor substitution, mediated through structural reconfiguration, and manifested in multifunctional outcomes. An evaluation system was constructed to operationalize the framework, and Zhejiang Province, China, was selected as an empirical validation case to demonstrate its analytical value. Specifically, the objectives of this study were as follows: (1) clarify the conceptual logic of cultivated land use transition from a “factor–structure–function” perspective; (2) develop a comprehensive indicator system for quantifying CLUT within this framework; and (3) illustrate how the framework enhances the diagnosis of transition mechanisms and pathways in a rapidly urbanizing context.

2. Methodology and Materials

2.1. Theoretical Framework

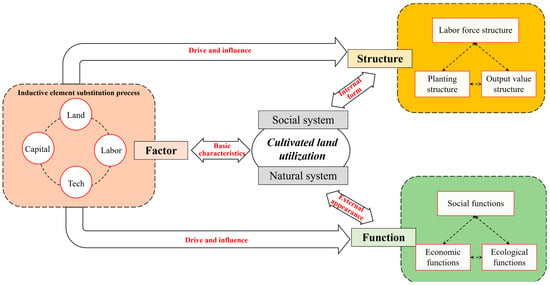

Cultivated land utilization refers to the activities of agricultural operators in exploring, developing, and managing cultivated land through production factor inputs. It essentially reflects social–natural system interactions in a specific region. According to the theory of induced technological innovation, the growth of agricultural productivity is partly driven by the continuous advancement of modern agricultural technology [32]. During the process of social and technological development, the relative prices of production factors in cultivated land utilization will experience continuous fluctuations. As relative prices and total production costs change, agricultural business entities may tend to replace scarce, expensive factors with abundant, cheaper alternatives and adopt technologies that conserve scarce resources [30,31]. Drawing on the theory of induced technological innovation and related land system transition studies, this study conceptualizes CLUT as a dynamic process, in which changes in relative factor endowments induce adjustments in land use structure and, subsequently, transformations in land use functions. This theoretical grounding ensures conceptual consistency across framework components and provides an analytical basis for linking factor inputs, structural characteristics, and multifunctional outcomes.

In this framework, CLUT is decomposed into three interrelated subsystems: the factor subsystem, the structure subsystem, and the function subsystem. Rather than treating these dimensions as independent or parallel components, the framework emphasizes their sequential and interactive relationships within the cultivated land use system. The factor subsystem represents the input conditions of cultivated land use, including labor, capital, and technological inputs (Figure 1). Changes in factor availability—particularly under conditions of labor outmigration and rising production costs—may induce substitution between labor and capital or technology, thereby altering production modes. Indicators within this subsystem were selected to capture both the scale and intensity of key production inputs, reflecting factor endowment conditions in a comparable manner across regions and time periods. The structure subsystem describes how cultivated land use is organized spatially and functionally, including cropping composition, land use intensity, and management patterns. Structural adjustment is regarded as a mediating process through which factor substitution is translated into observable changes in land use organization. Indicator selection in this subsystem prioritizes structural attributes that are sensitive to factor-driven adjustments while maintaining data continuity and comparability. The function subsystem reflects the multifunctional outcomes of cultivated land use, encompassing production, as well as ecological and socio-economic functions. Functional change is interpreted as the cumulative outcome of adjustments in factor inputs and land use structure. By incorporating multiple functional dimensions, the framework allows potential trade-offs and synergies among cultivated land functions to be systematically examined.

Figure 1.

The theoretical framework of “factor-structure-function” of cultivated land utilization.

It should be noted that this study aims to address the fragmentation issue in existing research, which tends to isolate the analysis of cultivated land dominant type transition and cultivated land functional transition, by means of this integrated framework. In doing so, it provides a holistic analytical tool for exploring the sustainable transition path of cultivated land utilization against the backdrop of rapid urbanization.

2.2. Study Area

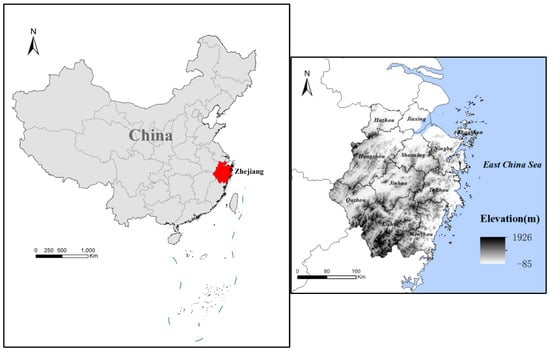

Zhejiang Province (27°02′–31°11′ N, 118°01′–123°10′ E) is located on China’s eastern coast, covering an area of 105,500 km2 and administered by 11 prefecture-level cities (Figure 2). As one of China’s most urbanized and economically dynamic provinces, Zhejiang’s per capita GDP has increased more than 60-fold over the past four decades. In contrast to its strong economic performance, the province has relatively scarce agricultural resources. According to data from the Third National Land Survey Bulletin of Zhejiang Province (2021) https://tjj.zj.gov.cn/art/2021/12/3/art_1229129205_4815828.html (accessed on 10 November 2025), approximately 74.6% of Zhejiang’s area consists of mountains and hills. Additionally, the province’s cultivated land area totals 1.2905 million hm2, accounting for only 1.01% of China’s total cultivated land. The quality of its cultivated land is also lower than the national average. Given these characteristics, Zhejiang Province has undergone significant cultivated land use transition since the 21st century against the backdrop of limited agricultural resources and rapid socio-economic development, making it an ideal case for studying China’s agricultural modernization, and for validating the framework proposed in this study.

Figure 2.

Location of the study area.

2.3. Evaluation System for Diagnosing Regional CLUT

Based on the above theoretical framework (Figure 1) and relevant empirical research [33], this paper constructed a “factor-structure-function” evaluation system to quantify regional CLUT characteristics. The system includes 3 target layers and 12 sub-indicators (Table 1), with weights determined via the expert scoring method. Notably, this study consulted five experts from Zhejiang University, Zhejiang University of Finance and Economics, and Zhejiang University City College. All interviewees hold doctoral degrees and possess extensive theoretical knowledge and practical experience in the field of cultivated land protection. We collected weight scores assigned by these five experts for each indicator, and determined the final weights for the evaluation system using the arithmetic mean [34]. The Cultivated Land Use Transition Index (CLUTI) was used to quantify CLUT across periods, calculated as follows:

Table 1.

The coupled evaluation system of cultivated land utilization state in this study.

2.4. Methodology

2.4.1. Data Collection

This study explores CLUT dynamics in Zhejiang since the 21st century, with the following two core considerations: (1) analyzing the latest cultivated land use status to provide practical guidance; and (2) accounting for key policy milestones (e.g., the 2006 Cultivated Land Requisition-Compensation Balance Policy and 2012 18th CPC National Congress land protection strategies) that impact CLUT. Five time points (2000, 2006, 2012, 2018, 2024) were selected for analysis.

The data used included the two following aspects: The socio-economic datasets were mainly from The Statistical Yearbook of Zhejiang Province for the relevant years, the database of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations database (FAO, https://www.fao.org/faolex/zh/), and the relevant statistical yearbooks of cities in Zhejiang Province. In terms of natural resource datasets, some data, such as NDVI values, were mainly from the Chinese Academy of Sciences Resource and Environmental Science Data Center (RESDC, https://www.resdc.cn/Default.aspx). For missing values, the average of values from adjacent years was used for imputation. All indicators were normalized using the min-max normalization method before being substituted into Formula (1).

2.4.2. Exploratory Spatial Data Analysis

Exploratory Spatial Data Analysis (ESDA) is a visual analysis of spatial data interaction based on spatial correlation to mine the potential relationships of data distribution [35]. The overall change trend of cultivated land use transformation can be used to test the spatial agglomeration characteristics of cultivated land use transition in Zhejiang Province according to global spatial autocorrelation analysis, which reflects the similarity of unit attribute values in adjacent regions according to Global Moran’s I index.

where xi and xj are the cultivated land use transition indices in regions i and j, respectively; is the average of the cultivated land use transition index by region; and Wij is a spatial weight matrix (adjacency of spatial units). If regions i and j are adjacent, then Wij = 1; otherwise Wij = 0. The value of Global Moran’s I index is between −1 and 1, and there is a positive correlation when I > 0, and a negative correlation when I < 0.

Local Moran’s I can check the heterogeneous changes in data computation and reveal the degree of correlation between spatial units and adjacent units at the attribute value level. The calculation formula is as follows:

According to the calculation results of Local Moran’ s I index, when Ii > 0, HH/LL indicates that the attribute values of the spatial unit are higher/lower than those of the surrounding cities, and the comprehensive spatial difference is small; when Ii < 0, LH/HL indicates that the spatial units with lower/higher attribute values are higher/lower than those of the surrounding cities, and the comprehensive spatial difference is larger.

2.4.3. Standard Deviational Ellipse

The Standard Deviational Ellipse (SDE) is a quantitative statistical method used to describe the spatial distribution of features [19]. It captures the overall spatial pattern through the lengths of its major and minor axes and the location of its centroid. The azimuth angle indicates the dominant directional trend, the major axis reflects the degree of dispersion of the spatial elements along that direction, and the center of gravity represents the relative position. The calculation formula of SDE is as follows:

where represents the azimuth angle of the ellipse (°), which is the angle formed clockwise by true north and the long axis; (, ) are the coordinates of the weighted centroid; , are the spatial locations of the features; is the weight assigned to point i; , are the coordinate deviations of each point from the weighted mean center; and and are the standard deviations along the and axes, respectively.

3. Results

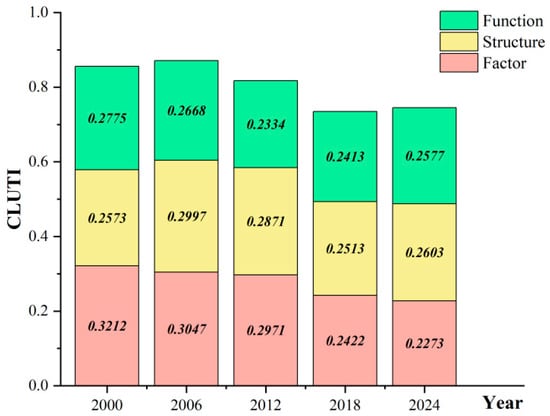

3.1. Temporal Dynamic Characteristics of CLUTI in Zhejiang Province

Based on the proposed “factor-structure-function” framework, the temporal dynamics of the cultivated land use transition index (CLUTI) in Zhejiang Province were calculated for the years 2000, 2006, 2012, 2018, and 2024. As shown in Figure 3, the overall CLUTI exhibited a fluctuating downward trend, from 0.8560 in 2000 to 0.7348 in 2018, and followed by a slight increase to 0.7453 in 2024. Examination of the three framework components reveals differentiated temporal trajectories. The factor component declined continuously over the study period, decreasing from 0.3213 in 2000 to 0.2273 in 2024. In contrast, the structure and function components showed fluctuating trends, with moderate rebounds observed in the later stage. Between 2018 and 2024, the structure component increased from 0.2513 to 0.2603, while the function component rose from 0.2413 to 0.2577.

Figure 3.

Dynamics in the CLUTI of Zhejiang Province from 2000 to 2024.

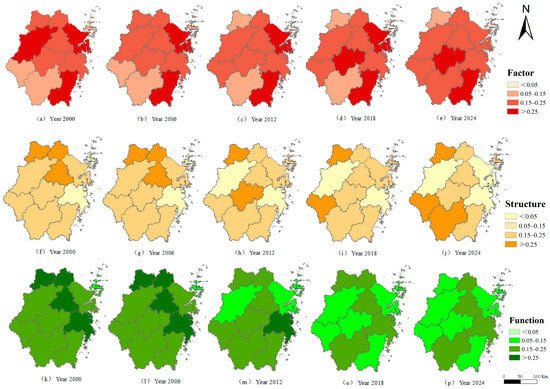

3.2. The Spatial Pattern of CLUTI in Zhejiang Province

The spatial distribution of CLUTI and its factor, structure, and function components at the prefecture-level city scale is presented in Figure 4. Three color schemes are used to illustrate the spatial patterns of the framework components across the five observation years. The factor and structure components exhibited broadly similar spatial patterns, characterized by relatively higher values in northern Zhejiang, and lower values in central and southern regions during the early 2000s. Cities including Huzhou, Jiaxing, Hangzhou, Shaoxing, and Ningbo recorded comparatively higher scores in both components at the beginning of the study period. Over time, the scores of these cities declined to varying degrees, while increases were observed in cities such as Jinhua, Quzhou, and Lishui. The function component displayed a distinct temporal–spatial trajectory. After reaching higher values around 2006, the overall functional scores declined in subsequent periods. This pattern is consistent with the temporal variation in the CLUTI reported in Section 3.1.

Figure 4.

Spatial pattern of the CLUTI in Zhejiang Province from 2000 to 2024.

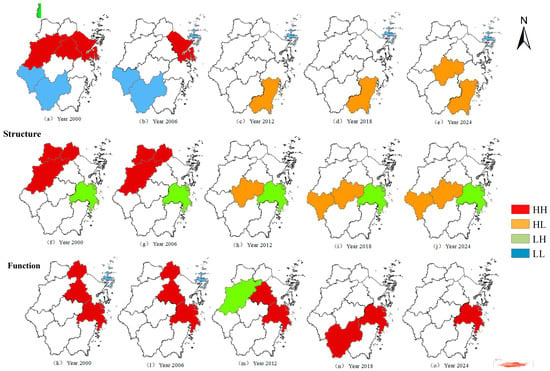

3.3. The Spatial Agglomeration Characteristics of CLUT

To further clarify the spatial pattern of cultivated land use transition and its dynamics, this study conducted a local spatial autocorrelation analysis and obtained Local Indicators of Spatial Association (LISA) cluster maps of cultivated land use transition. These maps reflected the spatial distribution patterns and differentiation changes in the four patterns—“High-High” (HH), “Low-Low” (LL), “High-Low” (HL), and “Low-High” (LH)—in the process of cultivated land use transition (Figure 5). On the whole, the cultivated land use transition in Zhejiang Province exhibited two similar characteristics across different components. On the one hand, the number of non-significant areas was greater than that of significant areas, and the number of areas showing the “High-High”, “Low-Low”, “High-Low”, and “Low-High” patterns was relatively small; on the other hand, the spatial agglomeration of cultivated land use transition in Zhejiang Province showed a trend of “weaker in the south and stronger in the north” over time, and the spatial scope of high-value agglomeration was constantly moving northward. Specifically, Hangzhou, Shaoxing, and Ningbo, in northern Zhejiang Province, exhibited HH clusters in terms of the factor component in 2000. However, over more than two decades of development, Jinhua, in central Zhejiang, and Wenzhou, in southern Zhejiang, gradually became “regional high points” with the HL cluster type. The same applied to the other two components: in the course of Zhejiang Province’s development, the high-level agglomeration areas of cultivated land use structural transition and functional transition have shifted from the cities in northern Zhejiang to Quzhou, Lishui, and Wenzhou in southern Zhejiang.

Figure 5.

Local spatial correlation maps of cultivated land use transition.

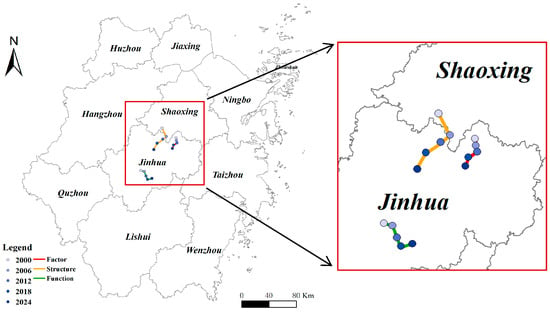

3.4. Changes in the Gravity Center of CLUT

The migration paths of the gravity centers of cultivated land use transition components were examined using the Standard Deviational Ellipse (SDE) method, as illustrated in Figure 6. The gravity center of the factor component shifted from northern Zhejiang toward the southwest over the study period, with a cumulative movement distance of 18.866 km. The structure component exhibited a similar migration direction, with a total displacement of 43.087 km between 2000 and 2024, moving from the northern part of Shaoxing City to within the spatial boundary of Jinhua City. The gravity center of the function component was initially located in central Jinhua City, and followed a more complex trajectory, shifting eastward from 2000 to 2006 and 2018 to 2024, and southward between 2006 and 2018, with a total movement distance of 25.406 km. Overall, the migration trajectories of the three components indicate a gradual spatial shift in factor input, structural configuration, and functional performance from northern Zhejiang toward central and southern regions.

Figure 6.

Path of gravity center of cultivated land use transition.

This trend can largely be attributed to the regional development strategies implemented by Zhejiang Province since the early 21st century. On the one hand, Zhejiang Province was among the first in China to implement the Intra-provincial Cultivated Land Requisition-Compensation Balance Policy. This policy explicitly stipulates that any cultivated land occupied for construction purposes must be offset by an equivalent area of newly reclaimed cultivated land within the province [36,37]. However, in practice, within Zhejiang Province, the requisitioned land has predominantly consisted of high-quality prime cultivated land, located in the urbanizing plains of northern Zhejiang, which historically supported stable grain production. In contrast, the compensatory cultivated land has mainly been developed in central and southern regions—such as Quzhou and Lishui—from previously unused hillsides, barren slopes, or low-quality cropland. These newly added plots are constrained by challenging topography (mountainous and hilly terrain), low soil fertility, and inadequate irrigation infrastructure [38,39]. On the other hand, as early as 2003, the Zhejiang Provincial Government launched the “Mountain-Sea Coordination Project,” aiming to encourage mutually beneficial cooperation between developed coastal counties and 26 underdeveloped mountainous counties to jointly advance common prosperity. By breaking down regional barriers to factor mobility and facilitating two-way, complementary flows of capital, technology, markets, and labor, this initiative has also effectively promoted the southward shift of high-value agglomeration areas in cultivated land utilization [40].

4. Discussion

4.1. Differentiated CLUT Pathways Revealed by the Integrated Framework

Under the integrated framework proposed in this study, the overall CLUTI exhibited a modest downward trend over the study period. In many conventional quantitative CLUT assessments, such a decline is typically interpreted as a generalized deterioration in cultivated land use performance. However, analysis at the “factor-structure-function” level indicates that this aggregate trend masks substantial internal restructuring, manifested through pronounced trade-offs and synergies among the framework indicators. One illustrative example concerns factor substitution dynamics. Although agricultural labor input declined sharply over the past two decades, this reduction was partially offset by increased capital and technological inputs, such as the expansion of agricultural machinery use. As a result, while the overall score of the factor component decreased, internal trade-offs within the component were indicative of a transition from labor-intensive to technology- and capital-supported cultivation systems, rather than a uniform deterioration of factor conditions.

By explicitly linking factor inputs, land use structure, and multifunctional outputs within a unified analytical framework, the proposed approach enables these internal adjustment processes to be systematically identified. Importantly, the results suggest that regions exposed to broadly similar external drivers—including urban expansion, labor outmigration, and policy-induced land reallocation—may nonetheless exhibit differentiated factor substitution patterns and internal reconfiguration processes. On this basis, three analytically distinguishable cultivated land use transition pathways can be identified, as detailed below.

The first pathway is a factor substitution-led pathway, in which rapid labor outflow constitutes the primary driver of transition, followed by structural reconfiguration and functional adjustment. This pathway is exemplified by peri-urban areas in northern Zhejiang, where cultivated land use has shifted from traditional grain production toward facility-based, leisure, or high-value agricultural activities, accompanied by a growing emphasis on economic and social service functions.

The second pathway is a structure-optimization-oriented pathway, characterized by targeted factor inputs—particularly capital and appropriately scaled machinery—supporting adjustments in cropping patterns and land management organization. This pathway is illustrated by mountainous regions in central and southern Zhejiang, where the development of specialty and ecological agriculture has enhanced both economic performance and ecological service functions of cultivated land.

The third pathway is a stability-oriented pathway, in which relatively stable factor conditions support balanced land use structures and functional outcomes. In some coastal regions, land transfer and farmland consolidation have facilitated intensive grain cultivation systems that maintain food security functions while supporting moderate income growth.

These pathways are not mutually exclusive, but represent ideal typical configurations of “factor-structure-function” interactions. The ability to disentangle such configurations constitutes a key contribution of the integrated framework, as differentiated transition pathways would remain largely indistinguishable under conventional CLUT assessments that rely on aggregate indices or single-dimensional indicators. In this sense, the framework reveals that similar overall CLUT trends may conceal fundamentally different internal transition logics.

4.2. Policy-Relevant Insights from Differentiated CLUT Pathways

Identifying differentiated cultivated land use transition pathways helps interpret regional CLUT dynamics in a policy-relevant, yet analytically grounded, way. Rather than assuming uniform responses to external pressures, the integrated framework indicates that policy priorities may differ depending on the dominant transition pathway observed in a region.

In regions following a factor substitution-dominated pathway, declining labor inputs are mainly offset by increased reliance on capital and technology. In such contexts, policy attention may focus on improving input–use efficiency and ensuring that agricultural technologies are well matched to local production conditions. Simply expanding capital is unlikely to be effective without corresponding improvements in technological suitability and management capacity. The experience of Hangzhou, where smart agriculture and tailored mechanization services have been promoted, illustrates how factor substitution can support efficiency-oriented intensification.

For regions characterized by a structure-led transition pathway, changes in cropping composition and land management organization play central roles. Policy efforts in these areas may, therefore, emphasize land use structure optimization, appropriate scale management, and coordination between production and marketing. Such measures can strengthen structurally driven transitions without relying heavily on additional factor inputs.

In regions dominated by functional rebalancing pathways, economic gains are often accompanied by trade-offs with food security or ecological functions. Here, policy considerations may give greater weight to coordinating multiple land use functions. Analytical insights from the framework suggest that instruments such as differentiated subsidies, functional zoning, or ecological compensation may help address these trade-offs more effectively than single-objective productivity enhancement.

Overall, the integrated framework links pathway-specific transition dynamics with differentiated policy considerations. Rather than offering direct policy prescriptions, it provides an analytical basis for aligning policy focus with the underlying mechanisms shaping cultivated land use transition in different regional contexts.

4.3. Methodological Contribution of the Proposed Framework

This study contributes methodologically to cultivated land use transition (CLUT) research by providing an integrated analytical framework that conceptualizes transition as a coherent process of factor substitution unfolding through structural adjustment and functional transformation. By explicitly linking factor inputs, land use structure, and multifunctional outcomes, the framework establishes a systematic logic for interpreting how changes in factor availability propagate through cultivated land systems. This integration enables internal trade-offs and synergies to be examined as components of a unified transition process, rather than as isolated indicator movements.

Building on this integrated logic, the framework enhances the ability to identify differentiated CLUT pathways. Instead of relying solely on aggregate transition scores, it reveals how distinct configurations of factor substitution, structural reorganization, and functional rebalancing may underlie similar overall CLUT trends. This pathway-oriented perspective allows CLUT dynamics to be interpreted in terms of how transition unfolds, thereby improving diagnostic clarity without requiring strong causal assumptions.

Taken together, these contributions position the proposed framework as a complementary methodological advance that strengthens the analytical coherence and interpretability of CLUT assessments. Rather than replacing existing approaches, the framework provides a transferable tool for pathway-oriented diagnosis that can be applied across diverse regional contexts to support more nuanced analysis of cultivated land use transition.

4.4. Limitations and Future Prospects

Several limitations of the proposed framework should be acknowledged. First, while the framework conceptually recognizes feedback mechanisms among factor inputs, land use structure, and functional outcomes, the empirical implementation primarily captures these relationships in a static and unidirectional manner. Future research could incorporate dynamic or system-based modeling approaches to better represent reciprocal interactions and temporal feedback loops. Second, the framework relies largely on secondary statistical data and remote sensing indicators, which may constrain the representation of certain biophysical and management-related processes. Data imputation procedures, while necessary for maintaining temporal continuity, may also smooth short-term variability in some indicators. In addition, the use of exploratory spatial methods emphasizes pattern identification, rather than causal inference.

Despite these limitations, the framework provides a flexible and extensible foundation for CLUT analysis. Future studies could enhance its robustness by integrating finer-scale biophysical indicators, longitudinal micro-level data, and complementary analytical techniques. Such extensions would further strengthen the framework’s capacity to diagnose cultivated land use transition pathways across diverse regional contexts.

5. Conclusions

This study proposed an integrated “factor-structure-function” analytical framework, which aims to conceptualize CLUT as a coherent process of factor substitution that unfolds progressively through structural adjustment and functional transformation. Using Zhejiang Province as a validation case, the results demonstrate that modest declines in aggregate CLUT indices may conceal substantial internal restructuring, characterized by pronounced trade-offs and synergies among framework components. On this basis, the framework enables the identification of differentiated CLUT pathways, revealing that regions exposed to similar external pressures may follow distinct transition logics.

Beyond empirical findings, the primary contribution of this study lies in its methodological advancement. The proposed framework enhances analytical coherence and interpretability by shifting CLUT assessment from aggregate description toward pathway-oriented diagnosis, thereby complementing existing dominant–recessive or index-based approaches. In this sense, the framework provides a methodological reference for aligning cultivated land development and conservation priorities in sustainable decision making, particularly in rapidly urbanizing regions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.L. and S.Z.; methodology, Z.Q. and M.W.; validation, Z.Q. and M.W.; formal analysis, Z.Q. and M.W.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.L.; writing—review and editing, Y.L., and C.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Zhejiang Provincial Philosophy and Social Science Planning Project of China, Grant No. 24NDJC321YBMS, the Exploration Project of Zhejiang Provincial Natural Science Foundation, Grant No. 24D010026 and The National Natural Science Foundation of China, Grant No. 42401120, No. 42501322.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Turner, B.L.; Lambin, E.F.; Reenberg, A. The emergence of land change science for global environmental change and sustainability. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2007, 104, 20666–20671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lambin, E.F.; Veldkamp, A. Key findings of LUCC on its research questions. Glob. Change Newsl. 2005, 63, 12–14. [Google Scholar]

- Long, H.L. Theorizing land use transitions: A human geography perspective. Habitat. Int. 2022, 128, 102669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Yu, L.; Du, Z.R.; Liu, Z.; Qi, Y.; Liu, T.; Gong, P. Toward sustainable land use in China: A perspective on China’s national land surveys. Land. Use Policy 2022, 123, 106428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mather, A.S. The forest transition. Area 1992, 24, 367–379. [Google Scholar]

- Grainger, A. National land use morphhology: Patterns and possibilities. Geography 1995, 80, 235–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambin, E.F.; Meyfroidt, P. Land use transitions: Socio-ecological feedback veersus socio-economic change. Land Use Policy 2010, 27, 108–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Defries, R.S.; Foley, J.A.; Asner, G.P. Land-use choices: Balancing human needs and ecosystem function. Front. Ecol. Environ. 2004, 2, 249–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.Q.; Xiang, P.C.; Cong, K.X. Research on early warning and control measures for arable land resource security. Land Use Policy 2023, 128, 106601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verburg, P.H.; Crossman, N.; Ellis, E.C.; Heinimann, A.; Hostert, P.; Mertz, O.; Nagendra, H.; Sikor, T.; Karl-Heinz, E.; Golubiewski, N. Land system science and sustainable development of the earth system: A global land project perspective. Anthropocene 2015, 12, 29–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Jin, X.B.; Xu, W.Y.; Zhou, Y.K. Evolution of cultivated land fragmentation and its driving mechanism in rural development: A case study of Jiangsu Province. J. Rural. Stud. 2022, 91, 58–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, X.F.; Xie, B.G.; Lu, R.C.; Zhang, X.M.; Xie, J.; Wei, S.Y. Spatial–Temporal Differentiation and Driving Factors of Cultivated Land Use Transition in Sino–Vietnamese Border Areas. Land 2024, 13, 165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, X.F.; Shao, Y.J.; Li, Y.H.; Liu, Y.S.; Wang, Y.S.; Wei, X.D.; Wang, X.F.; Zhao, Y.H. Cultivated land quality improvement to promote revitalization of sandy rural areas along the great wall in Northern Shaanxi Province, China. J. Rural. Stud. 2022, 93, 367–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, T.; Fu, S.; Zhang, X.; Wu, G.; Hu, H.; Tian, J. Assessing Cultivated Land–Use Transition in the Major Grain-Producing Areas of China Based on an Integrated Framework. Land 2022, 11, 1622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiang, W.; Liu, A.; Cheng, S.; Kastner, T.; Xie, G. Agricultural trade and virtual land use: The case of China’s crop trade. Land Use Policy 2013, 33, 141–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, H.L.; Qu, Y. Land use transitions and land management: A mutual feedback perspective. Land Use Policy 2018, 74, 111–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, W.H.; Wang, H.Y.; Luo, L.; Shi, Y.; Sui, Y.F.; Wu, L.; Zhang, B.B.; Yu, Q. Spatiotemporal impact of cultivated land use transition on grain production: Perspective of interaction between dominant and recessive transitions. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2026, 117, 108170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, Y.; Zhan, L.; Wei, C.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, J. Interactive transition of cultivated land and construction land during china’s urbanization: A coordinated analytical framework of explicit and implicit forms. Land Use Policy 2024, 138, 107049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, F.; Deng, S.; Wu, D.; Liu, W.; Bai, Z. Research on the spatiotemporal evolution of land use landscape pattern in a county area based on CA-Markov model. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2022, 80, 103760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, H. Spatiotemporal analysis of land use changes and their trade-offs on the northern slope of the Tianshan Mountains, China. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2022, 10, 1016774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, H.; Xie, H.; He, Y.; Wu, Z.; Zhang, X. Assessing the impacts of land fragmentation and plot size on yields and costs: A translog production model and cost function approach. Agric. Syst. 2018, 161, 81–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.; Sun, Z.; Guo, H.; Weng, Q.; Du, W.; Xing, Q.; Cai, G. An assessment of urbanization sustainability in China between 1990 and 2015 using land use efficiency indicators. Npj Urban Sustain. 2021, 1, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, S.; Liu, Q.; Han, S. Spatial-temporal evolution of coupling relationship between land development intensity and resources environment carrying capacity in China. J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 301, 113778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, X.; Liao, F.; Liu, Z.; Wu, G. Spatial–Temporal Characteristics and Driving Mechanisms of Land–Use Transition from the Perspective of Urban–Rural Transformation Development: A Case Study of the Yangtze River Delta. Land 2022, 11, 631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Li, X.; Xia, X. Temporal-spatial pattern and driving factors of cultivated land use transition at country level in Shaanxi province, China. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2022, 194, 365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiironen, J.; Riekkinen, K. Agricultural impacts and profitability of land consolidations. Land Use Policy 2016, 55, 309–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, J.K.; Ren, C.C.; Wang, S.T.; Zhang, X.M.; Stefan, R.; Xu, J.M.; Gu, B.J. Consolidation of agricultural land can contribute to agricultural sustainability in China. Nat. Food 2021, 2, 1014–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiang, W.L.; Tan, M.H.; Yang, X.; Li, X.B. The impact of cropland spatial shift on irrigation water use in China. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2022, 97, 106904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, Y.; Meng, J.J.; Zhu, L.K.; Han, Z.Y.; Ma, Y.X. Characterizing land use transition in China by accounting for the conflicts underlying land use structure and function. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 349, 119311. [Google Scholar]

- Song, X.Q.; Wang, X.; Li, X.Y.; Zhang, W.N.; Scheffran, J. Policy-oriented versus market-induced: Factors influencing crop diversity across China. Ecol. Econ. 2021, 190, 107184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, X.L.; Chen, J.; Zuo, C.C.; Wang, X.Q. The cropland intensive utilisation transition in China: An induced factor substitution perspective. Land. Use Policy 2024, 141, 107128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, X.Q.; Wu, Z.F. Modelling and mapping trends in grain production growth in China. Outlook Agric. 2013, 42, 255–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, Y.F.; Wang, M.J.; Zou, Y.N.; Wu, C.F. Mapping trade-offs among urban fringe land use functions to accurately support spatial planning. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 802, 149915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lyu, Y.; Sheng, L.; Wu, C. Improving land-cover-based expert matrices to quantify the dynamics of ecosystem service supply, demand, and budget: Optimization of weight distribution. Ecol. Indic. 2023, 154, 110515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, S.D.; Fang, B.; Cui, C.; Huang, S.H. The spatial-temporal pattern and path of cultivated land use transition from the perspective of rural revitalization: Taking Huaihai Economic Zone as an example. J. Nat. Resour. 2020, 35, 1908–1925. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lichtenberg, E.; Ding, C.R. Assessing farmland protection policy in China. Land Use Policy 2008, 25, 59–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Li, X.; Liu, Y. Cultivated land protection and rational use in China. Land Use Policy 2021, 106, 105454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.X.; Li, J.F.; Dong, Y.L. Telecoupling effects of requisition-compensation balance on regional grain productivity: Evidence from the Yangtze River Urban Agglomerations. Appl. Geogr. 2025, 168, 103434. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, C.Y.; Song, C.Q.; Ye, S.J. Provincial-level effectiveness of China’s arable land requisition-compensation balance policy, 1999–2019. Land Use Policy 2023, 131, 106733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.S.; Zhu, Y.W.; Wu, Y.; Wang, X.L.; Zhang, W.W. The Population Flow under Regional Cooperation of “City-Helps-City”: The Case of Mountain-Sea Project in Zhejiang. Land 2022, 11, 1816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.