Abstract

This study presents the first application of machine learning (ML) to detect and map mowed tidal wetlands in the Chesapeake Bay region of Maryland and Virginia, focusing on emergent estuarine intertidal (E2EM) wetlands. Monitoring human disturbances like mowing is essential because repeated mowing stresses wetland vegetation, reducing habitat quality and diminishing other ecological services wetlands provide, including shoreline stabilization and water filtration. Traditional field-based monitoring is labor-intensive and impractical for large-scale assessments. To address these challenges, this study utilized 2021 and 2022 Sentinel-2 satellite imagery and a time-series analysis of the Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI) to distinguish between mowed and unmowed (control) wetlands. A bidirectional Long Short-Term Memory (BiLSTM) neural network was created to predict NDVI patterns associated with mowing events, such as rapid decreases followed by slow vegetation regeneration. The training dataset comprised 204 field-verified and desktop-identified samples, accounting for under 0.002% of the research area’s herbaceous E2EM wetlands. The model obtained 97.5% accuracy on an internal test set and was verified at eight separate Chesapeake Bay locations, indicating its promising generality. This work demonstrates the potential of remote sensing and machine learning for scalable, automated monitoring of tidal wetland disturbances to aid in conservation, restoration, and resource management.

1. Introduction

Tidal wetlands are among the most significant and most threatened ecosystems in the Chesapeake Bay watershed [1], offering vital services such as wildlife habitat, shoreline stability, and improved water quality [2]. Human activities, such as repeated mowing to create better viewsheds or improve shoreline access for pedestrians, are reducing habitat quality and limiting the ability of wetlands to both provide shoreline erosion protection and filtration of stormwater pollutants. The phenomenon is such that the latest Logic and Action Plan for 2023–2024 (CBP 2023) from the Chesapeake Bay Program’s (CBP) Wetlands Workgroup identified increased awareness of the negative impacts of tidal herbaceous wetlands mowing (“wetland mowing”) as one of its goals [3]. Figure 1 illustrates a mowed herbaceous tidal wetland. Monitoring these disruptions across a large geographic region presents substantial challenges, particularly with traditional field-based surveys, which are time-consuming and expensive. Remote sensing technologies, combined with machine learning techniques, provide a scalable and effective approach for identifying anthropogenic disturbances across large landscapes. This study represents the first attempt to apply machine learning algorithms to satellite-derived vegetation indices to detect and map mowed tidal wetlands of the Chesapeake Bay in Maryland and Virginia.

Figure 1.

An example of a mowed herbaceous tidal wetland (E2) composed primarily of Distichlis spicata (Saltgrass) in the front yard of a home on Virginia’s Chesapeake Bay.

Previous research has shown that remote sensing and machine learning may be used to map and monitor wetlands, but there are still issues in reliably recognizing fine-scale anthropogenic disturbances like mowing. Classifiers such as Random Forest (RF) and Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs) have been successfully used to assess wetland vulnerability and land cover changes at Khinjhir Lake (a Ramsar wetland in Thatta District, Sindh Province, Pakistan, 100 km from Karachi), but they are primarily concerned with broad-scale land use and climate-driven impacts rather than localized anthropogenic activities [4]. Similarly, integrating the Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI) time-series with Dynamic Time Warping (DTW) has improved within-wetland vegetation classification and methane emission estimations in large-scale land surface models, despite not explicitly targeting physical disturbances such as mowing [5]. RF models have also been used to map Wetland Intrinsic Potential (WIP) in river floodplains, although they rely significantly on static topographic inputs and have low temporal resolution for disturbance detection [6]. Meta-analyses suggest a strong dependence on standard machine-learning approaches, with minimal use of deep-learning models capable of dealing with complicated spatial-temporal data [7]. Ensemble ANN techniques have increased wetland cover classification accuracy, but they frequently ignore temporal vegetation dynamics, which are crucial for detecting seasonal disturbances [8]. Furthermore, RF-based inundation modeling and ArcticNet’s convolutional neural networks (CNNs) for wetland categorization emphasize the necessity for large, labeled datasets and typically lack sensitivity to short-term events such as mowing [9,10]. CNNs have been used to extract historical wetland data from maps, but these efforts are geared toward cartographic digitization rather than real-time disturbance detection [11]. Recent deep-learning work employing physically informed features has enhanced spatial wetland mapping, but it is still constrained by its emphasis on hydrological predictors rather than plant status across time [12]. More sophisticated deep learning frameworks, such as ResNet paired with Temporal Optimized Features (TOFs), show promise for mapping coastal wetlands and assessing restoration, but they need huge, region-specific training datasets and extensive temporal data processing [13].

In contrast, this paper presents a novel application of a Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) neural network to NDVI time-series data taken from Sentinel-2 imaging, which is specially tailored to capture the distinct temporal patterns associated with mowing episodes in tidal wetlands. Unlike earlier systems that depend on static predictors or single-date imaging, our LSTM-based algorithm uses the temporal dimension to detect abrupt decreases and slow recoveries in vegetation indices, which are indicators of mowing disturbance. This technique enhances sensitivity to short-term and cyclical vegetation changes, enabling scalable and automated monitoring of anthropogenic impacts throughout the Chesapeake Bay region. Despite current limitations related to training sample size and data quality, our preliminary results demonstrate the feasibility of this technique for informing targeted conservation efforts and regulatory interventions aimed at protecting emergent tidal wetlands or for validating proper management of restored wetlands, at the desktop.

2. Data Preparation

Applications of machine learning that are successful rely significantly on the caliber and organization of input data. Data preparation for this project included creating time-series vegetation measurements, determining training and testing locations, and establishing the geographical boundaries of the study region. The study focused on herbaceous tidal wetlands whose substrate is regularly submerged and exposed by tides, known as estuarine intertidal emergent wetlands (E2EM) as per Cowardin, L. M. (1979) [14,15].

Spatial information from the National Wetlands Inventory (NWI) [16] and the National Land Cover Database (NLCD) [17] was used to define the study regions. The NWI gives comprehensive mapping of E2EM wetlands, whereas the NLCD offers 20 land cover categories at 30 m spatial resolution for the whole United States. This study specifically focused on land cover class 95—Emergent Herbaceous Wetlands—areas where perennial herbaceous vegetation accounts for greater than 80% of vegetation cover and where soil or substrate is periodically saturated with or covered with water. Although both datasets are widely used in environmental applications, they have known limitations in terms of classification accuracy. The NLCD is estimated to be 90% accurate [18], while the accuracy of the NWI may be below 80% [19] according to some studies. Despite these limitations, they were the best available datasets for defining the spatial extent of herbaceous E2EM wetlands in the Chesapeake Bay region as a whole.

This delineation process culminated in the spatial intersection of the NLCD and NWI data using the specialized “Intersect” tool in ArcGIS (version 3.4), creating a resultant polygon shapefile that represented only those areas categorized by both systems. This combination was essential to filter out confounding variables, particularly by carefully selecting NWI codes that avoided frequently submerged or naturally non-persistent tidal habitats. Such non-persistent areas exhibit low spectral values that could easily be mistaken for the spectral signature of mowed sites during the subsequent Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI) analysis. Functioning as a vital pre-filter, this intersection ensured the computationally demanding temporal machine learning analysis was restricted exclusively to the persistent herbaceous E2EM wetlands, which are the specific habitat of regulatory and ecological concern.

Sentinel-2 multispectral satellite imagery from the European Space Agency (ESA) served as one of the main data sources for monitoring and tracking vegetation health and change. At spatial resolutions of 10 to 60 m, the Sentinel-2 network of Earth-observing satellites provides multispectral imaging in 13 spectral bands [20]. Sentinel-2 is ideally suited for time-series research of dynamic ecosystems such as tidal wetlands because of its high return frequency. Eight different Sentinel-2 tiles covering the Chesapeake Bay region were used to gather imagery for this study from 2021 to 2022. A selection of 56–63 photos per tile was obtained by excluding images with more than 30% cloud cover (Table 1). Images used (after filtering) in Table 1 refers to the number of Sentinel-2 Level-2A scenes retained for each tile after applying the scene-level cloud-cover filter. This study used Sentinel-2 image tiles T18SUJ, T18SUH, T18SUG, T18SUF, T18SVJ, T18SVH, T18SVG, and T18SVF to cover the entire Chesapeake Bay region.

Table 1.

Sentinel-2 tiles used in this study, their dimensions, and the number of images retained after filtering.

The Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI) [21] was calculated for all Sentinel-2 images. NDVI is a remote sensing-derived metric that quantifies the density and health of live green vegetation. It is computed using the formula:

where and represent surface reflectance values of a pixel in the Red and NIR (near infrared) bands, respectively. Healthy, photosynthetically active vegetation strongly absorbs visible red light and reflects NIR light, resulting in higher NDVI values. In contrast, areas with sparse or stressed vegetation exhibit lower NDVI values. NDVI values range from −1 to +1, with higher values representing denser and healthier vegetation cover. The NDVI time-series for each site captured seasonal growth cycles as well as disturbances such as mowing, which result in sharp, sudden declines in NDVI followed by gradual recovery as vegetation regrows.

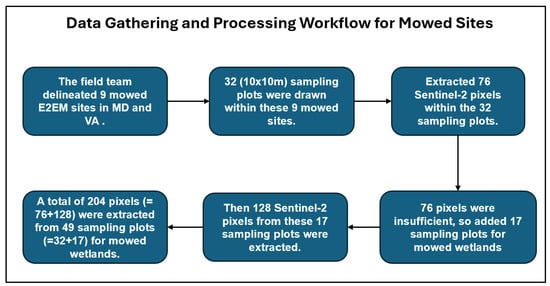

The mask file created using NWI and NLCD datasets was then used to extract NDVI pixels from herbaceous E2EM wetlands for subsequent processing and analysis. The NDVI image processing workflow, demonstrated in Figure 2, primarily illustrates the project’s iterative response to resource limitations rather than a conventional scientific pipeline. Due to budgetary constraints, initial field verification was restricted to sampling only 32 plots (10 × 10 m) of mowed wetlands, yielding an insufficient quantity of 76 Sentinel-2 pixels for robust model training. To address this critical shortage, a strategic adjustment was made: an additional 17 mowed E2EM plots were identified and secured through cost-effective desktop analysis using historical, ultra-high-resolution imagery, affording the model 128 supplementary pixels. This approach, detailed in the diagram, ultimately resulted in a combined training sample of 204 pixels, and included separate analyses for sites located in Virginia (VA) and Maryland (MD), reflecting the regional scope of the study area within Chesapeake Bay.

Figure 2.

This flowchart illustrates the multi-stage collection process used to generate the final training dataset.

For the control samples needed to balance algorithm training, an equivalent number of 204 Sentinel-2 pixels were collected from unmowed, natural E2EM herbaceous wetlands in both Maryland and Virginia, exclusively via desktop analysis using historic Google Earth Pro imagery. These control plots were strategically selected from within wetland preserves, such as Hart Miller Island (MD), Blackwater National Wildlife Refuge (MD), and Saxis Wildlife Management Area (VA), ensuring they accurately represented genuinely undisturbed E2EM wetlands, even though they were not field-delineated. This combination of mowed and unmowed samples provided the final training dataset for the subsequent time-series analysis.

3. Machine Learning Technique

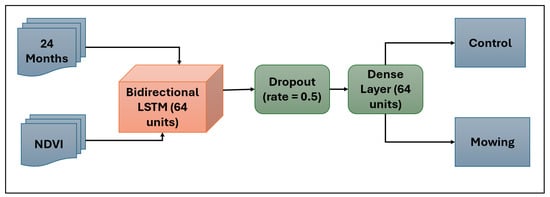

A Bidirectional Long Short-Term Memory (BiLSTM) [22,23] neural network, designed to categorize mowing and control tidal wetlands, served as the main machine learning technique used in this investigation. Recurrent neural networks (RNNs) of the BiLSTM type are intended to evaluate time-series by identifying relationships across time. BiLSTM networks handle information both forward and backward via a sequence, allowing the model to use both past and future context, in contrast to normal neural networks that process each input independently. As such, they are adept at identifying intricate temporal patterns. To identify mowing events, which are defined by abrupt drops in NDVI values followed by a slow recovery, the BiLSTM model was used for NDVI time-series data in this study. Figure 3 displays the BiLSTM model’s design.

Figure 3.

Bidirectional LSTM model classifies 2-year NDVI time-series data (Month, NDVI) into Mowing and Control classes.

NDVI measurements across 24 time steps, as 24 months of vegetation monitoring throughout the two-year period from 2021 to 2022, made up each input sample of the training data. These sequences shed light on the dynamics of the vegetation at certain points in the Chesapeake Bay area. When vegetation was removed from mowed wetlands, NDVI values usually decreased dramatically before gradually increasing as the vegetation came back. Control wetlands, on the other hand, showed regular seasonal variations devoid of sudden shifts.

To understand the differences in vegetation dynamics between the two classes, the temporal NDVI patterns of both mowed and control wetlands were included as part of the training data analysis. The mean NDVI values for each training sample over the 24-month research period are displayed in these time-series charts. Control sites showed smoother, cyclical seasonal variations, whereas mowed sites showed sharp declines in NDVI followed by a slow rebound. Figure 4 illustrates this contrast and offers visual confirmation of the different temporal patterns that were employed to train the BiLSTM model.

Figure 4.

Mean NDVI values over time for mowed and control wetland sites. “Mean” represents the NDVI at each time step.

The model’s capacity for generalization was assessed using a 5-fold cross-validation procedure. The data set was split up into five equal folds. Four folds were employed for training and one-fold was set aside for validation in each cycle. Each fold served as the validation set once during the five iterations of this procedure. Cross-validation results were averaged to reduce potential bias and offer a trustworthy measure of model performance.

To maximize the model’s performance, four hyperparameters were adjusted. These included the batch size, which specifies the number of samples processed simultaneously; the learning rate, which determines the magnitude of parameter updates; the number of epochs, which indicates the number of times the model cycles through the training data; and the number of BiLSTM units, which regulate the network’s ability to learn complex patterns. To minimize overfitting and strike a balance between model complexity and training efficiency, hyperparameter adjustment was crucial. Finally, one 64 BiLSTM unit was trained for 200 epochs with an exponential learning rate decay and early stopping. The corresponding training and validation learning curves are provided in the Supplementary Materials (Figures S1 and S2).

In addition to the primary BiLSTM model, three baseline models were implemented for comparative evaluation: a Random Forest (RF) classifier, a Convolutional Neural Network (CNN), and a Multilayer Perceptron (MLP). To ensure a fair comparison, RF, CNN, MLP, and BiLSTM were trained using the same input variables, specifically the per-pixel Sentinel-2 NDVI time series spanning 2021–2022 and represented as 24 monthly NDVI values (24 time steps). These models were selected based on their demonstrated success in prior wetland and environmental classification studies. For example, Mahdianpari et al. [24] employed RF for multi-source SAR-based wetland mapping with high accuracy, while Pouliot et al. [25] showed that CNNs effectively capture spatial complexity in Landsat-based wetland classification. Similarly, Zhang et al. [26] applied MLPs combined with morphological attributes for coastal wetland mapping using Sentinel-2 imagery. While these models are well-established for spatial classification tasks, they lack mechanisms to model temporal dependencies, which limits their ability to detect dynamic changes such as mowing. By comparing these non-temporal baselines with a BiLSTM—a model specifically designed to capture sequential patterns in time-series data—this study highlights the advantages of using temporally-aware architectures for disturbance detection in tidal herbaceous wetlands.

The NDVI time-series data and associated labels were preprocessed before training to meet the BiLSTM network’s input specifications to fit the model’s input. Two years’ worth of monthly NDVI measurements for each site were represented by the data, which were organized into sequences of 24-time steps. The vegetation status—mowed or controlled—was observed at the last time the step was used to give labels. As a result, the BiLSTM model was able to learn from both previous and upcoming steps in its classification process. Additionally, labels were transformed into a categorical format that could be used for tasks involving multi-class categorization.

This machine learning system showed a reliable and scalable method for the automatic identification of mowing disturbances in emerging tidal wetlands using time-series satellite images by integrating BiLSTM architecture, thorough data preparation, and rigorous cross-validation.

4. Results

This section first summarizes model performance on the internal test set and then presents the spatial variation and regional mapping results across the Chesapeake Bay.

4.1. Model Performance Evaluation

Four different models, namely RF, CNN, MLP, and BiLSTM, were trained to evaluate the performance. The BiLSTM model showed good classification performance on the internal validation data during training and testing. Figure 5 illustrates the accuracy and confusion matrix of all these models using the testing data. Eighty percent of the dataset was utilized for training, while twenty percent was allocated for testing after training. The BiLSTM model’s overall accuracy on this held-out test data was 97.5%. It outperformed the other 3 models in the categorization of the test data. Only two control sites were incorrectly labeled as mowing sites, and the algorithm accurately recognized almost all occurrences of both mowed and control wetlands.

Figure 5.

Confusion matrix and test accuracy for all four models evaluated on the 20% test dataset. The BiLSTM model outperformed others, showing correct classifications of control (38) and mowed sites (40), with two control sites misclassified as mowed.

4.2. Spatial Variation and Regional Mapping Results

The trained model was subsequently assessed on eight independent Sentinel-2 images as test sites, which were not part of the training or initial validation process, in addition to the internal test set. These sites represent different regions within Chesapeake Bay and exhibit varying vegetation dynamics. The model’s predictions across these independent sites are summarized in Figure 6. The findings show that different test sites had different percentages of projected mowed and control areas. For example, site T18SUH showed a predicted mowing rate of 0.82%, while site T18SVF had a higher predicted mowing rate of 10.53%. These variations may reflect differences in site conditions, mowing intensity, or model generalization performance.

Figure 6.

Predicted classification results for eight independent test sites, showing the proportion of mowed (blue) and control (orange) wetlands, along with corresponding NDVI time-series plots for each site.

The eight classified images were then combined into a comprehensive mosaic that covered the entire bay (Figure 7). Across the Chesapeake Bay, a total of 211,962 pixels were identified as mowed E2EM wetlands, equivalent to 21.2 km2 or 5237.7 acres. Of these mowed wetlands, 11.5 km2 were in Virginia and 9.4 km2 in Maryland. Afterwards, a classification accuracy assessment was performed by randomly generating 1000 reference points evenly distributed across the bay. Historical ultrahigh-resolution imagery was then used in Google Earth Pro to evaluate and label each reference point as either mowed or controlled. A confusion matrix was constructed using these labeled reference points and is presented in Table 2.

Figure 7.

Spatial distribution of mowed tidal wetlands (E2EM) across Chesapeake Bay.

Table 2.

Classification confusion matrix constructed using 1000 reference points.

The confusion matrix reveals that 63 reference points were correctly classified as mowed wetlands, while 317 points were mistakenly classified as mowed but were controls. In contrast, 22 reference points were classified as control but were mowed, and 598 points were correctly classified as control wetlands.

Using this matrix, the user’s accuracy and producer’s accuracy for mowed wetlands, the overall accuracy of the classification, and the Kappa index, were calculated, as shown in Table 3. The user’s accuracy for mowed wetlands was 16.58%, indicating the probability that a pixel classified as mowed wetland represents mowed wetland on the ground. The producer’s accuracy was 74.12%, representing the likelihood that a mowed wetland on the ground was correctly classified by the algorithm. The overall accuracy of the classification was 66.1%, reflecting the general performance of the classified image, which includes both mowed and control wetlands. The Kappa index, which measures the agreement between the reference and the classified data beyond chance, was 15.33%, indicating that this particular classification is 15.33% better than a random classification.

Table 3.

Classification Accuracies.

5. Discussion

The spatial map shown in Figure 7 illustrates the widespread distribution of predicted mowing activity across the tidal emergent wetlands of both Maryland and Virginia. Notably, higher concentrations of mowed E2EM wetlands are observed in the lower Eastern Shore, southern Maryland, and the northern reaches of the Virginia coast, areas that also have high proportions of privately owned shoreline properties. This spatial insight reinforces the need for targeted outreach and conservation efforts in regions where mowing disturbances are most prominent.

While the mosaic classification provides useful spatial insight, the external validation metrics in Table 3 indicate important limitations in the universality of the mapped product for estimating mowing extent. Specifically, the user’s accuracy for mowed wetlands (16.58%) and the Kappa index (15.33%) suggest that a substantial fraction of pixels classified as “mowed” do not represent mowed wetlands on the ground, which can bias both the apparent spatial distribution and area statistics derived from the map. This is consistent with the confusion matrix, where 317 reference points were mistakenly classified as mowed but were controls, compared to 63 correctly classified mowed points. One contributing factor is that NDVI-only temporal signals can be subtle for light or partial mowing and can also be confounded by other wetland dynamics, which may produce NDVI patterns that resemble mowing. In our broader project documentation (https://cbtrust.org/wp-content/uploads/Wetlands-Mowing-Final-to-CBT-1.27.25.pdf, accessed on 15 January 2026), we noted that some irregularly flooded wetlands were easily mistaken for mowed wetlands because their NDVI trends appeared similar, which aligns with the observed false-positive tendency in the external validation. In addition, any mask-related errors that introduce non-target pixels into the candidate wetland extent (or omit true tidal emergent wetlands) can further increase false positives and reduce the reliability of mapped area estimates.

This also helps explain the discrepancy between the high internal test accuracy in Figure 5 and the lower external validation performance. The internal test set is drawn from the same curated training framework and therefore may not capture the full regional variability in wetland conditions and mowing intensity across the Chesapeake Bay, whereas the external validation samples a broader and more heterogeneous set of wetlands where NDVI trajectories and wetland-mask errors may differ from the training data.

Notwithstanding these encouraging outcomes, there are still limitations. The training dataset represented only a small fraction of the total wetland area within the study region, restricting the model’s ability to generalize to all areas. Furthermore, reliance on the NLCD and the NWI to define wetland locations introduced potential inaccuracies, and errors in these datasets may have led to mislabeling in both training and validation data, potentially affecting model accuracy. Lastly, variability in classification accuracy across the eight test sites suggests a need for further site-specific calibration and localized studies to improve model performance.

Another aspect to consider is that the relatively small size and limited geographic diversity of the training data restrict the ability of the model to generalize the predictions to broader areas. Furthermore, potential inaccuracies in ancillary datasets, such as the National Land Cover Database (NLCD) and National Wetlands Inventory (NWI), may introduce labeling errors that affect model performance, particularly at the resolution needed to identify homeowners’ mowing of emergent tidal wetlands on their property. Future work should focus on expanding the training dataset to include more diverse sites, improving the quality and accuracy of spatial data, and further refining the model through hyperparameter tuning and site-specific calibration. Remote sensing-based monitoring has the potential to provide an effective, scalable, and affordable tool for wetland conservation and management in the Chesapeake Bay region and other vulnerable ecosystems globally, as machine learning techniques continue to progress and more extensive datasets become available. Use of more accurate and reliable wetland classification data, such as the Virginia Tidal Marsh Inventory, which offers higher accuracy, could potentially improve classification accuracy, at least in Virginia.

Nevertheless, the study successfully demonstrated the feasibility of using BiLSTM neural networks in combination with Sentinel-2 NDVI time-series data to detect mowing activity in tidal wetlands. The distinct temporal signatures associated with mowing events, those characterized by abrupt declines followed by a gradual recovery in NDVI, were effectively captured and classified by the model. These results highlight the potential for applying machine learning and remote sensing approaches to support scalable and automated wetland monitoring and management efforts.

6. Conclusions

This exploratory study demonstrates the potential of combining remote sensing data with advanced machine-learning techniques to monitor anthropogenic disturbances in emergent tidal wetlands. By analyzing NDVI time-series derived from Sentinel-2 imagery, the BiLSTM model effectively classified mowed and controlled wetlands. The model achieved a high classification accuracy of 97.5% on the internal test dataset, with only minor misclassifications, and showed promising generalization capabilities when applied to eight independent test sites within the Chesapeake Bay region. Despite these encouraging results, several limitations need to be addressed before the methodology can be applied in operational monitoring or regulatory contexts. However, this study performs excellently as a foundation for further optimization for developing a functional machine learning system to identify key locations and coordinate outreach and conservation efforts to maintain the natural integrity of Chesapeake Bay.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/land15010193/s1, Figure S1: Training and validation learning curves (accuracy and loss) for the BiLSTM model trained on the 204 labeled NDVI time-series samples. The validation curves follow the training curves during convergence, and no persistent widening gap is observed between training and validation loss. This figure is provided as evidence to support training reliability and assess potential overfitting under the limited sample size. Figure S2: Training and validation learning curves (accuracy and loss) for the CNN baseline model trained on the same 204 labeled NDVI time-series samples. Similar to Figure S1, the validation trends broadly track the training trends during optimization, providing an additional reference for assessing convergence behavior and overfitting. This figure is included to substantiate the reported accuracy with corresponding training dynamics.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.H., C.W. and X.H.; Methodology, M.H. and X.H.; Software, M.H. and C.W.; Validation, M.H., S.A.-N., C.W. and X.H.; Formal analysis, M.H. and C.W.; Investigation, M.H. and C.W.; Resources, C.W., A.S.d.B. and X.H.; Data curation, M.H., S.A.-N. and C.W.; Writing—original draft, M.H.; Writing—review & editing, M.H., C.W., A.S.d.B., M.B., L.W.M. and X.H.; Visualization, M.H., C.W., A.S.d.B. and X.H.; Supervision, C.W. and X.H.; Project administration, C.W., A.S.d.B., M.B., L.W.M. and X.H.; Funding acquisition, C.W., A.S.d.B., M.B. and L.W.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research is part of the project “Understanding and Addressing the Impacts of Wetland Mowing to Facilitate Meeting the Chesapeake Bay Wetland Enhancement Goals,” funded by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and awarded to Clean Streams, LLC, with grant administration provided by the Chesapeake Bay Trust under Assistance Agreement No. CB96374201.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the authors.

Acknowledgments

We thank Pam Mason, Lead Scientist of the Chesapeake Bay Program Goal Implementation Team (GIT), and the entire GIT committee for providing valuable data and guidance throughout the implementation of this project. Additional data acquisition, processing, and analysis were supported by the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) National Land Imaging (NLI) Program under Grant No. G23AP00683.

Conflicts of Interest

Alexi Sanchez de Boado was employed by Clean Streams, LLC., Mark Burchick and Leslie Wood Mummert were employed by Environmental Systems Analysis, Inc. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Chesapeake Bay Program. Wetlands Action Plan; Chesapeake Bay Program: Annapolis, MD, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Maryland Department of the Environment. Wetlands and Waterways Protection Program. Available online: https://mde.maryland.gov/programs/water/wetlandsandwaterways/pages/index.aspx (accessed on 20 December 2025).

- Chesapeake Bay Program. Logic and Action Plan for 2023–2024, the CBP Wetlands Workgroup (WWG); Chesapeake Bay Program: Annapolis, MD, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Aslam, R.W.; Shu, H.; Naz, I.; Quddoos, A.; Yaseen, A.; Gulshad, K.; Alarifi, S.S. Machine Learning-Based Wetland Vulnerability Assessment in the Sindh Province Ramsar Site Using Remote Sensing Data. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazbeck, T.; Bohrer, G.; Shchehlov, O.; Ward, E.; Bordelon, R.; Villa, J.A.; Ju, Y. Integrating NDVI-Based Within-Wetland Vegetation Classification in a Land Surface Model Improves Methane Emission Estimations. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halabisky, M.; Miller, D.; Stewart, A.J.; Lorigan, D.; Brasel, T.; Moskal, L.M. The Wetland Intrinsic Potential tool: Mapping wetland intrinsic potential through machine learning of multi-scale remote sensing proxies of wetland indicators. EGUsphere, 2022; unpublished work. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jafarzadeh, H.; Mahdianpari, M.; Gill, E.W.; Brisco, B.; Mohammadimanesh, F. Remote Sensing and Machine Learning Tools to Support Wetland Monitoring: A Meta-Analysis of Three Decades of Research. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 6104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Zhang, P.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, J. Improving wetland cover classification using artificial neural networks with ensemble techniques. GISci. Remote Sens. 2021, 58, 603–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaeri; Karimi, S.; Saintilan, N.; Wen, L.; Valavi, R. Application of Machine Learning to Model Wetland Inundation Patterns Across a Large Semiarid Floodplain. Water Resour. Res. 2019, 55, 8765–8778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Z.; Von Ness, K.; Loisel, J.; Wang, Z. ArcticNet: A Deep Learning Solution to Classify Arctic Wetlands. 2019; unpublished work. [Google Scholar]

- Ståhl, N.; Weimann, L. Identifying wetland areas in historical maps using deep convolutional neural networks. Ecol. Inform. 2022, 68, 101557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Neil, G.L.; Goodall, J.L.; Behl, M.; Saby, L. Deep learning Using Physically-Informed Input Data for Wetland Identification. Environ. Model. Softw. 2020, 126, 104665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, L.; Lu, Y.; Tan, Q.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, Q. Precise mapping of coastal wetlands using time-series remote sensing images and deep learning model. Front. For. Glob. Change 2024, 7, 1409985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subcommittee, W. Classification of Wetlands and Deepwater Habitats of the United States; Federal Geographic Data Committee: Reston, VA, USA, 2013.

- Cowardin, L.M. Classification of Wetlands and Deepwater Habitats of the United States; Fish and Wildlife Service, US Department of the Interior: Washington, DC, USA, 1979.

- U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. National Wetlands Inventory (NWI): Download Wetlands Data. Available online: https://www.fws.gov/program/national-wetlands-inventory/wetlands-data (accessed on 20 December 2025).

- Multi-Resolution Land Characteristics (MRLC) Consortium. National Land Cover Database (NLCD). Available online: https://www.mrlc.gov (accessed on 20 December 2025).

- Wickham, J.; Stehman, S.V.; Sorenson, D.G.; Gass, L.; Dewitz, J.A. Thematic accuracy assessment of the NLCD 2019 land cover for the conterminous United States. GISci. Remote Sens. 2023, 60, 2181143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Finlayson, C.M.; Spiers, A.G. (Eds.) Global Review of Wetland Resources and Priorities for Wetland Inventory; Supervising Scientist: Canberra, Australia, 1999.

- NASA Earthdata. Sentinel-2 Multispectral Imager (MSI). Available online: https://www.earthdata.nasa.gov/data/instruments/sentinel-2-msi (accessed on 20 December 2025).

- Huang, S.; Tang, L.; Hupy, J.P.; Wang, Y.; Shao, G. A commentary review on the use of normalized difference vegetation index (NDVI) in the era of popular remote sensing. J. For. Res. 2021, 32, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Huo, X.; Shao, K. Temperature Time Series Prediction Model Based on Time Series Decomposition and Bi-LSTM Network. Mathematics 2023, 11, 2060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Zheng, H.; Wang, L.; Hellwich, O.; Chen, C.; Yang, L.; Liu, T.; Luo, G.; Bao, A.; Chen, X. A joint learning Im-BiLSTM model for incomplete time-series Sentinel-2A data imputation and crop classification. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2022, 108, 102762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahdianpari, M.; Salehi, B.; Mohammadimanesh, F.; Motagh, M. Random forest wetland classification using ALOS-2 L-band, RADARSAT-2 C-band, and TerraSAR-X imagery. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2017, 130, 13–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pouliot, D.; Latifovic, R.; Pasher, J.; Duffe, J. Assessment of Convolution Neural Networks for Wetland Mapping with Landsat in the Central Canadian Boreal Forest Region. Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, A.; Sun, G.; Ma, P.; Jia, X.; Ren, J.; Huang, H.; Zhang, X. Coastal Wetland Mapping with Sentinel-2 MSI Imagery Based on Gravitational Optimized Multilayer Perceptron and Morphological Attribute Profiles. Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.