Abstract

Target 3 of the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework commits nations to protecting and conserving at least 30% of the world’s terrestrial and inland water areas and coastal and marine areas by 2030 (30 × 30). There can be significant overlap with Indigenous and traditional territories (ITTs) and protected areas. We explore if and/or how ITTs are currently recognized and reported as contributors to national protection targets by analyzing whether these territories are counted as standalone conservation areas, integrated into government-led protected and conserved area networks or systems, or neither, in 18 countries. Our analysis reveals critical linkages between tenure regimes, ITTs and their recognition in reporting to global area-based conservation databases. Legal recognition of tenure rights, particularly ownership and stewardship rights, emerged as the strongest predictor of whether ITTs are formally being accounted for in these databases. Our findings also reveal that the contribution of ITTs to national protection targets not only depend on tenure type but also on governance rights, despite the way it is reported. We categorize systemic barriers and opportunities that have implications for the contribution of ITTs to 30 × 30 goals.

1. Introduction

Indigenous Peoples and Local Communities (IPs and LCs) steward 36% of the world’s Key Biodiversity Areas [] and some 22% of the Brazilian Amazon—regions marked by exceptional ecological health and significantly lower deforestation rates compared to non-Indigenous territories [,,,]. Indigenous and traditional territories (ITTs) intersect about 40% of terrestrial protected areas and ecologically intact landscapes []. Their customary ways of life, refined over millennia, position IPs and LCs as indispensable partners in halting biodiversity loss [], assuming that no harmful practices are incorporated over time. While most ITTs are held under customary or community tenure systems, in many countries, these tenure systems lack legal (i.e., titled) recognition [,], and IPs and LCs are at risk of external pressures to their land such as land conversion and development encroachment, among others [].

The United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples [] states that “Indigenous peoples have the right to the lands, territories and resources which they have traditionally owned, occupied or otherwise used or acquired” and that “States shall give legal recognition and protection to these lands, territories and resources”. However, national legal frameworks have in the past failed to formally recognize IPs and LCs rights and efforts over their lands and territories and in area-based conservation []. In addition, where tenure is not secured, governance on land and/or resources within that land may be subject to terms set by landowners or the government [].

In 2022, 196 nations committed to the Convention on Biological Diversity’s (CBD) Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework (GBF), which included protecting at least 30% of terrestrial and inland water areas, and coastal and marine areas by 2030—the “30 × 30” protection target []. Defining which lands and water bodies qualify towards this target is thus critical, with protected areas (PAs) or other effective area-based conservation measures (OECMs) serving as primary pathways.

The path to adopting Target 3 of the GBF was marked by debates over the role of ITTs in CBD discussions. Early drafts of Target 3 (e.g., []), like its predecessor Aichi Target 11 [], only included reference to protected areas and OECMs as means to achieving these targets. During final negotiations at the 15th meeting of the CBD Conference of Parties (COP15), the phrase “recognizing indigenous and traditional territories, where applicable” was inserted into the final text of Target 3 of the Global Biodiversity Framework []. This addition introduced ambiguity as to whether ITTs are considered by the parties to the CBD to represent a ‘third pathway’ (alongside protected areas and OECMs) in achieving this Target, particularly with the qualifying words ‘recognizing’ and ‘where appropriate’. Reference to “recognizing indigenous and traditional territories, where applicable” was separate to another, more explicit clause at the target’s conclusion: “recognizing and respecting the rights of indigenous peoples and local communities, including over their traditional territories”. The late inclusion of this text in the GBF left little room for clarification, resulting in ongoing debate over whether ITTs constitute a ‘third pathway’ (equivalent to protected areas and OECMs in their contribution towards Target 3) or if they merely inform the designation of existing measures (e.g., [,,,,]).

The final text for Target 3 of the GBF as adopted by the parties [] was:

Ensure and enable that by 2030 at least 30 per cent of terrestrial and inland water areas, and of coastal and marine areas, especially areas of particular importance for biodiversity and ecosystem functions and services, are effectively conserved and managed through ecologically representative, well-connected and equitably governed systems of protected areas and other effective area-based conservation measures, recognizing indigenous and traditional territories where applicable, and integrated into wider landscapes, seascapes and the ocean, while ensuring that any sustainable use, where appropriate in such areas, is fully consistent with conservation outcomes, recognizing and respecting the rights of indigenous peoples and local communities, including over their traditional territories.[emphasis added]

This ambiguity has highlighted critical knowledge gaps, including if and/or how ITTs are currently recognized and reported as contributors to national area-based protection targets.

Future negotiations under the CBD would benefit from information around those gaps. The important role of Indigenous protected areas for biodiversity conservation is well accepted [,], and studies have been conducted to assess overlaps of ICCAs or other Indigenous territory types with protected areas [,], aspects of the governance of Indigenous territories and PAs [,] and the equity of IPs and LCs in PAs []. However, no assessment has been made on how countries account for these areas in their national and global reporting of area-based conservation measures (if they do).

This research is therefore guided by the following three research questions:

- What tenure regimes govern ITTs in area-based conservation? To be able to understand how ITTs are recognized and if they are considered as an area-based conservation measure at the national level, we needed to explore the tenure regimes in which ITTs are registered and operate. Tenure rights would also inform the resource access, use, management, exclusion and alienation rights ascribed to the land and to IPs and LCs and the agency they hold in relation to area-based conservation.

- How are ITTs recognized, reported and accounted for as area-based conservation measures toward Target 3 of the GBF? We explore if and how ITTs are accounted for as an area-based conservation measure in a country and therefore reported globally to the World Database on Protected Areas (WDPA) or World Database on Other Effective Area-based Conservation Measures (WD-OECM) to derive commonalities (or differences).

- What barriers and opportunities influence ITT inclusion in national area-based conservation accounting that contribute towards Target 3 of the GBF? We explore other barriers and opportunities recorded by a subset of countries.

To address these questions, our study investigates country-level approaches to ITT inclusion in 18 countries, analyzing whether these territories are counted as standalone conservation areas, integrated into government-led protected and conserved areas network or systems, or neither. Emphasis on reporting government-managed protected areas alone risks under-reporting progress towards Target 3, overlooking community-governed lands ([], see also [,] for privately protected areas). Our findings aim to inform global guidelines for auditing and reporting ITT conservation efforts, particularly given the emphasis of the GBF on equitable governance []. We did not conduct qualitative assessments of the areas in relation to their ultimate contribution to biodiversity conservation.

We define ITTs per the GBF’s Target 3 language as lands stewarded, governed or held by Indigenous Peoples and Local Communities (IPs and LCs), encompassing territories historically termed Indigenous lands, Indigenous and Community Conserved Areas (ICCAs) or customary areas [,,]. ICCAs are defined as territories and areas conserved by Indigenous Peoples and Local Communities. ICCAs and ITTs are sometimes used interchangeably; however, ITT was coined from CBD discussions, while ICCA was coined from IPs and LCs framing. The other relevant distinction is that ICCAs are Indigenous territories recognized as related to conservation, while it may not be the case for ITTs. We distinguish between ITTs recognized as territories and those formally reported as contributing towards national or global protection targets (e.g., 30 × 30, as per reporting to the WDPA or the WD-OECM).

In this paper, we use the term Indigenous Peoples and Local Communities (IPs and LCs) as a collective term, adopted from the CBD negotiation process to refer to diverse, unique and distinct groups of people who have different relations to land, culture and resources. While the grouping of IPs and LCs is done for a pragmatic reason, we are cognizant of the different connections and relations that these groups have to land and resources, and this grouping is not adopted to take away from this connection. This research arrives at a critical juncture, where nations must now demonstrate progress toward the 30 × 30 target, yet lack consensus or consistency on integrating IPs and LCs governed lands into national reporting mechanisms. By understanding these recognition and reporting approaches, we provide insights to align conservation policy with the rights and realities of the stewards of some of the world’s most biodiverse lands and water areas.

2. Materials and Methods

To address gaps in understanding how ITTs contribute to Target 3 of the GBF, we conducted a review of tenure regimes, their national recognition as mechanisms either as Indigenous or traditional lands and/or as protected or conserved areas, and global reporting of these territories in 18 countries—Australia, Belize, Bolivia, Brazil, Canada, Colombia, Ecuador, Gabon, Guatemala, India, Indonesia, Jamaica, Kenya, Mexico, Peru, South Africa, the United States of America and Zambia. To accomplish this, we developed questions related to the different types of tenure, how lands are registered in the selected countries and governance of these lands (See Box A1). To select sample countries, we pre-identified those that could present a variety of approaches to ITTs in respect to area-based conservation measures. We also considered the presence of The Nature Conservancy (TNC) or its partners—specifically, national or regional offices with IPs and LCs experts to ensure credibility and facilitate access to reliable information and data from country teams. Data was collected through qualitative reviews of national- and subnational-level legislation, such as acts, laws, decrees, bills and policies. We also reviewed peer-reviewed publications and grey literature on aspects of tenancy, protected area management, etc. Finally, we reviewed data in the WDPA and WD-OECM databases. Virtual consultations were also conducted with the in-country point of TNC staff who work directly with IPs and LCs; these include conservation specialists, policy experts, community specialists, etc. Data collected through the data collection matrix (Box A1) and the virtual consultation was analyzed using content analysis, where we gathered themes and emerging connections. This information was then summarized in a table (Appendix B, Table A1). Descriptive statistics was also applied to provide quantitative data for the themes emerging from the qualitative data collected.

While our non-random sampling design limited statistical analysis, the strategic selection of 18 countries across six continents captures critical geographic, socio-economic, tenure and governance diversity. This approach enables comparative analysis of tenure recognition mechanisms, offering empirically grounded insights into how varied legal and cultural contexts shape conservation outcomes and global reporting.

To answer our research questions, we developed an analytical matrix with the following components (See Appendix A, Box A1 for more details):

- Tenure: Legal recognition (titled vs. customary), registration processes and rights frameworks.

- Governance: IPs and LCs decision-making authority in biodiversity conservation.

- Recognition: Formal and informal recognition of lands to contribute to biodiversity conservation.

- Reporting: National criteria for designating ITTs as protected areas or OECMs.

- Barriers and opportunities.

Table 1.

Tenure regimes for Indigenous Peoples and Local Communities and the definitions [].

Table 2.

Bundle of rights (tenure rights) over the territory and definitions [].

We define recognition as the formal or informal acknowledgment of Indigenous and traditional territories (ITTs) by governments, and in the context of Target 3, ITTs are also recognized as contributors to area-based conservation. For the purposes of this analysis, for an ITT to be ‘formally’ recognized, it requires legal instruments (e.g., land titles, statutes) that explicitly designate ITTs as conservation areas. In contrast, ‘informal’ recognition derives from customary systems or traditional governance practices, often lacking state-sanctioned documentation.

Reporting refers to the inclusion of ITTs in either the World Database on Protected Areas (WDPA) or the World Database on Other Effective Area-based Conservation Measures (WD-OECM). Governments or authorized NGOs submit geospatial and tabular information to these registries, which are then publicly accessible via the Protected Planet platform (https://www.protectedplanet.net/) [].

Tenure security is defined as the legal right to ownership, demonstrated by the level of certainty that a person or community’s rights to land will be recognized by others and protected by law [,,,]. Formal tenure security is often recognized by issuing of a land title deed or land decree. In other countries, customary lands are registered by the government and held in trust by the government on behalf of the communities; thus, communities enjoy exclusion rights over their lands (e.g., for the case of Kenya, see [,]). The registration of customary lands is a pathway for community lands receiving a communal title deed for the land as a form of security. However, the majority of community land is customarily held and is often not registered or recognized by the government.

3. Results

3.1. Tenure Regimes, Tenure Rights and ITTs

Our analysis reveals critical linkages between tenure regimes, Indigenous and traditional territories and their recognition in reporting to the WDPA and WD-OECM. Across the 18 countries studied, ITTs operate under three distinct tenure regimes with direct implications for conservation accounting (see details in Table 3). These include the following:

Table 3.

Representation of tenure regimes and rights for area-based conservation in 18 countries (see Appendix B, Table A1 and Table A2 for the comprehensive table).

- State/Public Lands: While governments retain ownership (either as state land, crown land or public land), IPs and LCs exercise partial governance rights. Our results showed IPs and LCs have either holder rights (4/18 countries), manager rights (10/18 countries) or user rights (5/18 countries). These arrangements—evident in co-management models (e.g., Zambia Game Management Areas or Kenya’s Forest Areas)—enable IPs and LCs participation in conservation on state/public lands but rarely confer decision-making power over the designation as protected and conserved areas.

- Indigenous Territories and Community Lands: These lands are often regarded as customary or collectively Indigenous/community-governed lands (termed ITTs, ICCAs, or communal lands) that are held in trust by the state for IPs and LCs. Countries vary on how ITT tenure relates to Protected and Conserved Area (PCA) designation. There is also variation within countries (e.g., by subnational governments). Our results showed that only 10 of the surveyed countries hold formal legal titles granting full ownership rights (e.g., alienation, transfer rights) to IPs and LCs. Other models encountered operate under hybrid regimes that is registered as private lands, including but not limited to lands under IPs and LCs ownership. This occurs in 8 out of the 18 countries surveyed.

- Private Lands: These refer to lands that have a land title deed and are legally registered as private lands, including but not limited to lands under IPs and LCs ownership. This occurs in 8 out of the 18 countries surveyed.

The three categories of tenure regimes outlined above are the well-known tenure categories as described by the IUCN []. Table 3 portrays the diversity of tenure regimes and tenure rights encountered in target countries, as well as the diversity of approaches within countries. For instance, while some lands in Peru are owned by the state, with IPs and LCs having holders rights over the lands, the same country contains lands under the ownership of IPs and LCs, whereby IPs and LCs have owner and manager rights. Additionally, in Zambia, IPs and LCs rights vary, including user and management rights on customary held lands, as well as user rights on crown land, as land is customarily held and not owned by local communities in Zambia.

3.2. ITTs Recognition, Reporting and Accounting for Area-Based Conservation

These tenure regimes not only vary with tenure rights, as shown above, but they also intersect with diverse governance regimes (see Table 4). We reviewed data from WDPA/WD-OECM databases for the 18 countries in our study to understand how lands with different tenure regimes were governed and how these are nationally reported to WDPA/WD-OECM. Table 4 below shows the three types of tenure regimes (State, Communal (IPs or LCs) and Private lands) that had different governance regimes (state, private, communal or shared, as described by IUCN), and thus different countries reported these lands differently.

Table 4.

Tenure regimes, governance regimes and the designation and reporting of lands to WDPA or WD-OECM by different countries. IUCN Cat = IUCN Protected Area Management Categories [].

Table 4 illustrates how land tenure and the governance regime influence national recognition of lands and the reporting of lands to global databases. For example, in Australia, Indigenous Protected Areas (IPAs) blend state recognition with traditional ownership (or exclusive rights holdings), whereas in Kenya, registered and titled community lands are nationally recognized, while unregistered and untitled community lands in which community conservancies are established for the purpose of wildlife protection rely on informal agreements vulnerable to state oversight. Crucially, of the 18 countries surveyed, we find that tenure security directly predicts reporting outcomes: secure/titled ITTs (state-recognized or private) are more likely to appear in WDPA and WD-OECM datasets as IPs and LCS contributions than insecure/untitled customary lands. Specifically, there were 1054 (out of the 88,066) records in WDPA and WD-OECM by June 2025 for the 18 countries in our study [], which are reported explicitly as a full or partial IPs and LCs contribution (i.e., owned or governed, at least partly, by IPs and LCs—see Appendix C). Over 90% of those explicitly reported IPs and LCs contributions to WDPA/WD-OECM are with nationally recognized collective (Indigenous/communal) or private tenure types (see Table A3 in Appendix C), and only 10% are areas with less secure tenure. Overall, the data shows that clear ownership rights have a direct correlation with lands recognized by national databases and thus reported to global databases of protected areas and OECMs as an IPs and LCs contribution.

Further, a review of the WDPA and WD-OECM databases showed the similarities of entries of ITTs inclusion in the national network of protected areas, and, therefore, reporting to WDPA are (1) state formal recognition or acknowledgement of ITTs as lands that contribute to biodiversity conservation; (2) land demarcation, which is delimited spatial boundaries; (3) ITT tenure over the land that is known and clarified; and (4) the IPs and LCs governance status over the area is known. While some of these elements were not the main focus of this study, they are important to take into account to understand how different countries report to WDPA or WD-OECM. Our study did not investigate consultation approaches used by the state with IPs and LCs over the inclusion of their lands on national networks of protected or conserved areas. Considering the principles of Free, Prior and Informed Consent (FPIC) with IPs and LCs underlies implementation of the GBF; this and the above elements would be of interest to explore in more detail in further studies.

Based on the above elements, we grouped IPs and LCs in relation to their contribution to the Global Biodiversity Framework Target 3 into the following four levels (described below and summarized in Table 5):

Table 5.

Levels of national recognition and reporting of ITTs to WDPA or WD-OECM.

Level 1 (Full Contribution): ITTs with formal land title deeds (e.g., Kenya’s titled conservancies, Brazil’s Indigenous Protected Areas) are reported to WDPA, where they are managed for conservation and considered a protected area. These territories benefit from robust legal frameworks, full governance rights of IPs and LCs, and alignment with IUCN protected area management categories. The key elements for this level include:

- Recognition: A national legal framework exists to support recognition of IPs and LCs in area-based conservation.

- Reporting: IPs and LCs governance or management efforts are reported in WDPA or WD-OECM as either protected areas or OECMs, where IPs and LCs lands are clearly listed in WDPA/WD-OECM.

- Tenure: IPs and LCs have full tenure or are working towards tenure recognition, e.g., lands are registered but still in the process of getting the land title deeds finalized.

- Governance: IPs and LCs have governance and management rights and agency to support area-based conservation.

Level 2 (Hidden Contribution): These are areas that, despite IPs and LCs’ stewardship, states designate these as state protected areas, governed by the government or privately protected areas. The key elements for this level include:

- Recognition: There is no national legal framework to support recognition of IPs and LCs in area-based conservation. In some cases, ITTs are customarily held, not registered (hence, not titled, i.e., no land title deed) and thus not formally recognized. In other cases, tenure overlaps with government protected areas; hence, lands are not recognized as IPs and LCs lands.

- Reporting: Given that tenure is unresolved, IPs and LCs governance or management efforts are concealed. In such cases, the areas are reported under state protection (e.g., national parks) or as private protected areas.

- Tenure: IPs and LCs do not have tenure, but efforts may exist to support IPs and LCs tenure. In some cases, IPs and LCs have designated lands or demarcated lands, but they are not full owners, just holders of the land (in these cases, the state owns the land).

- Governance: IPs and LCs may have governance and management rights and agency to support area-based conservation, although they have to consult with the tenure holders. There are cases where IPs and LCs are part of state-constituted management committees.

Level 3 (Potential Contribution): These include customary held ITTs (e.g., Indonesia’s hutan adat; Myers et al. 2017 []) that are not considered by the government as area-based conservation measures due to legal ambiguities regarding tenure. In other cases, the existing legal framework does not support ITTs as contributors to area-based conservation (e.g., as an Indigenous peoples reserve for Indigenous peoples (IPs) in isolation, where biodiversity conservation is a by-product and not a primary or secondary objective). The latter is an example of an area that could potentially be recognized as an OECM with an ancillary biodiversity conservation objective. Currently, Indigenous peoples in these isolated reserves have their culture rights guaranteed by national laws, but their contribution to biodiversity conservation is often sidelined, precluding WDPA eligibility []. The key elements of this level include:

- Recognition: There is a legal framework that recognizes IPs and LCs’ contribution to biodiversity conservation, but this framework may not recognize an ITT as an area-based conservation measure. This may happen in cases where IPs and LCs lands are customarily held or when the law is silent about overlaps between an IP land with an already established protected area. In other cases, while IPs reside on the land, their current circumstances do not allow them to acquire tenure (e.g., involuntary isolated Indigenous groups with temporary status).

- Reporting: IPs and LCs governance or management efforts are not reported in WDPA/WD-OECM (despite conservation intention and potential). In some cases, IPs and LCs do not see the benefits of their lands voluntarily contributing to a national target and prefer to not have their lands counted towards the national target. In other cases, the IPs and LCs lands do not fall in the protected area or OECM category and hence do not currently fit the national legal categories of protected lands and are thus not reported.

- Tenure: IPs and LCs have full tenure or are working towards tenure recognition, e.g., lands are registered but still in the process of getting the title deeds finalized; in some cases, IPs and LCs hold customary or traditional tenure.

- Governance: IPs and LCs have governance and management rights and agency to support area-based conservation.

Level 4 (Hindered Contribution): Absent legal frameworks, states retain governance, excluding the agency of IPs and LCs. Contested territories face political barriers (e.g., Canada’s Indigenous Protected and Conserved Areas (IPCAs) awaiting federal recognition). Key elements of this level include:

- Recognition: There is no national legal framework to support recognition of IPs and LCs in area-based conservation.

- Reporting: IPs and LCs protection efforts in terms of governance or management are neither recognized nor reported.

- Tenure: IPs and LCs do not have tenure over the lands, and there are no or little efforts to support the tenure recognition of IPs and LCs by the state, or tenure overlaps with state protected areas.

- Governance: IPs and LCs do not have governance of lands, or governance rests with other parties, e.g., the government.

It is important to note that these levels are not mutually exclusive within a single country, as they can exhibit multiple levels concurrently.

3.3. Barriers and Opportunities That Influence the Inclusion of ITTs in National Area-Based Conservation Accounting Towards Target 3

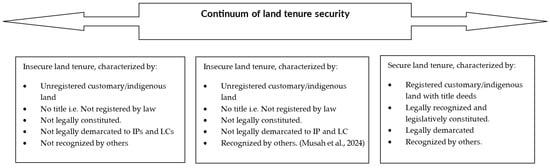

From the data collected, we identified that tenure security is one key determinant for the recognition and reporting of ITTs to WDPA/WD-OECM. We note that most of the ITTs reported were either under customary or communal tenure or Indigenous tenure, of which the majority of these tenure types do not have formal legal recognition (insecure). This implies that in many cases, for land to count towards the national system of protected area, they need to be recognized by the state through a legislative or administrative framework (e.g., in Kenya, for community lands—which are customary held—to be recognized as conservancies and included in the national count, these lands need to be registered through official channels and then counted). In many cases, recognition through a legislative framework implies a link to tenure security and thus lands with registered customary lands or with legal titles. Many ITTs mainly fall under customary tenure/community land (with the exceptions of registered customary lands, as outlined above) and are often not officially recognized by the state, nor are they protected through legal frameworks. Thus, tenure security occurs across a continuum for ITTs within the sphere of area-based conservation (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Representation of the continuum of tenure security for ITTs within the sphere of area-based conservation [].

To portray these cases, we present case studies from three countries (Australia, Peru and Kenya), on three continents, representing a mix of IPs and LCs tenure regimes (Box 1). These case studies illustrate a continuum of approaches in the three geographies, which may result from political contexts in the countries.

Box 1. Case studies from Australia, Kenya and Peru highlighting the complexities of ITTs across the four recognition reporting levels outlined in Table 5.

Case Study: Indigenous Protected Areas and Other Mechanisms for Indigenous Ownership and Management of Protected Areas in Australia.

Australia became a federated nation in 1901; however, most of the powers associated with land and thus conservation remained the domain of the state and territory governments. At the time of signing the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD), Australia’s protected area estate was largely made up of combinations of national parks, nature reserves and other protected area categories on public land designated by each of the states and territories, and in some cases, the Federal Government, where they had jurisdiction []. Following Australia becoming a signatory to the CBD, a more coordinated approach to expanding the protected area estate was initiated. The concept of a ‘National Reserve System’ (NRS) was developed, which would include the collection of public, private and Indigenous lands managed by different agencies and including different governance arrangements.

A new category of protected area was introduced—Indigenous Protected Areas (IPAs)—and a new program to encourage IPAs was developed in the mid-1990s. IPAs have been a large success, based on the take up and land area included in the NRS. There are 91 IPAs, more than 104 million hectares of land comprising more than 50% of Australia’s NRS and 6 million hectares of sea covered by the IPAs (as of early 2025) []. These occur in some of Australia’s most intact ecological landscapes, such as the central deserts and northern savannas, and are a critical pathway for Australia to follow national and international policies and achieve set targets [,].

IPA declaration is a voluntary process, typically instigated by the Australian Government calling for expressions of interest from eligible Indigenous organizations to be part of a consultation process (e.g., []). IPAs are contractual agreements between the Australian Government and an Indigenous organization [], where that organization has ownership, exclusive rights or some other formalized management arrangements over land or sea. While IPA designation is not formalized through legislation, its recognition stems from the ‘other effective means’ component of the protected area definition []. Financial resources are provided from the Australian Government to the Indigenous groups for protected area management and Indigenous ranger positions.

For the Australian Government to approve the declaration of an IPA, extensive consultation needs to be undertaken to ensure the Indigenous community is in agreement for such a declaration. This is often done through processes to identify values, assets and future ambitions—be they ecological, cultural or socio-economic—often through Healthy Country Planning (e.g., []).

There are a range of mechanisms for the involvement of Indigenous Australians in the management of other types of protected areas, such as the transfer of ownership of some national parks to Indigenous groups and the development of formal co-management (joint management) arrangements []. Legislation and policy related to joint management varies between Australian states and territories, but all jurisdictions have at least some process to provide roles for Aboriginal peoples in public protected area governance and/or management, but this may not be applied consistently within jurisdictions []. Co-management arrangements for marine protected areas are less advanced but increasing, as is the development of Sea Country Indigenous Protected Areas [,].

Indigenous ownership of freehold or pastoral land, often the result of land purchase, has seen the application of permanent conservation covenants, a mechanism typically associated with privately protected areas [,,,,].

Case Study: Kenya’s Conservancy Model as a Pathway to Achieving 30 × 30 Targets.

Kenya’s Wildlife Conservation and Management Act (2013) provides a legislative foundation for community-led conservation, enabling Indigenous Peoples and Local Communities (IPs and LCs) and private landowners to establish wildlife conservancies alongside state-managed protected areas (e.g., national parks, reserves). These conservancies—defined as lands dedicated explicitly to wildlife conservation []—must undergo a rigorous registration process with the Kenya Wildlife Service (KWS), including ecological assessments, community consultations, and compliance with land use regulations. There are three types of conservancies based on tenure and governance: (1) private conservancies on private land tenure; (2) group conservancies on private land, with individual landowners forming a group to manage the land; and (3) community conservancies established on community land []. Communities are the governing group for community conservancies, including for the management of their lands. Few community lands are registered with the government and have legal title deeds, while the majority are not yet registered but held in trust by the county government on behalf of the communities []. Registered and titled community lands have all rights to the land, including alienation rights; however, the decision-making process is lengthy and cumbersome.

Despite the country legally recognizing the role of IPs and LCs in conservation, progress towards Kenya’s 30 × 30 targets remains uneven and unclear on the contribution to the country’s national protected and conserved areas network. According to the Kenya Wildlife Conservancy Association’s State of the Conservancies report, as of 2024, only 38 of the 257 conservancies nationwide are registered with KWS, and just 21 of 115 community conservancies on customary lands are reported to the WDPA []. This disparity stems largely from tenure insecurity, as the government reports lands with a clear tenure regime to avoid double reporting or lands taken up by external parties. This is to say that titled community and private conservancies that have clear tenure and governance regimes (Level 1, Full contributions) are often reported; but 82% of community conservancies (94/115) operate on untitled customary lands, relegating them to Level 3 (potential contributions), as these conservancies are not registered with KWS and thus are not officially recognized nationally as contributing to the country’s protection target and thus are not reported to WDPA by state agencies.

Kenya’s legal framework, including the Community Lands Act (2016), recognizes IPs and LCs’ rights to govern and conserve their lands. However, unclear tenure regimes complicate reporting and national contribution to the protected area network. In Kenya, national reported lands are as follows:

1. Titled community lands (18% of cases) and private lands are reported to WDPA as protected areas.

2. Co-managed public lands grant IPs and LCs stewardship rights but retain state ownership.

3. Customary tenured conservancies remain excluded due to lack of formal titles.

Kenya has achieved 13.97% terrestrial protection against its set national target of at least 30% (set in July 2024, as of January 2025). Closing this gap requires integrating conservancies on untitled customary land, which could add ~82% of currently unreported community lands. This case underscores the critical role of tenure security in equitable conservation. By resolving tenure barriers, Kenya could set a global precedent for leveraging Indigenous and local stewardship to achieve biodiversity goals.

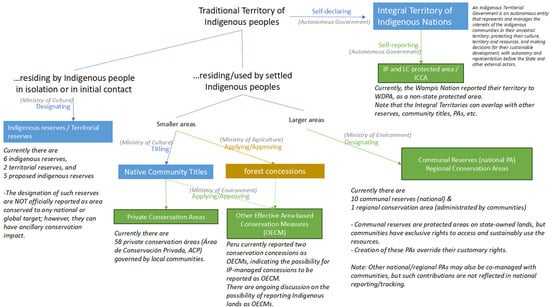

Case Study: Diverse and Evolving Ways of IPs and LCs Contributing to Global Biodiversity Framework 30 × 30 Targets in Peru.

The Constitution of Peru and various laws, such as the Law on the Right to Prior Consultation (No. 29785)) and the Forest and Wildlife Law [,], acknowledge the rights of Indigenous peoples over their ancestral lands and natural resources. These laws ensure that Indigenous Peoples and Local Communities are consulted on projects that may affect their lands and resources, and recognize the role of Indigenous Peoples and Local Communities in managing and protecting these areas.

Peru’s National System of Natural Protected Areas by the State (SINANPE) includes three types of areas that are (or can be) managed and governed by Indigenous Peoples and Local Communities: Communal Reserves, Regional Conservation Areas and Privately Conserved Areas. Communal Reserves and some Regional Conservation Areas are designated by the national and regional governments, respectively, for large areas of customary Indigenous lands that are not titled to individual communities. Neighboring Indigenous communities co-manage these protected areas and can use the resources under the management plans. Currently, there are 10 Communal Reserves (out of 77 National protected areas) and 1 (out of 32) Regional Conservation Areas that are co-managed by Indigenous communities (Level 2—Hidden Contribution) []. For Indigenous and peasant communities who want to include (part of) their titled lands in SINANPE, the only option so far is to go through a rigorous process to register as Private Conservation Areas with the National Service of Natural Areas Protected by the State []. Currently, SINANPE contains 57 (out of 139) Private Conservation Areas that are governed/managed by Indigenous and local communities [], which means that, in total, around 2.5% of the ~2000 IPs and LCS communities in the Peruvian Amazon have their titled land officially recognized and reported to the area-based conservation target (Level 1—full contribution). In comparison, about 15% of communities are within protected area buffer zones. Discussions are taking place in Peru among government agencies, IPs and LCs, and civil society regarding recognizing Indigenous territories or conservation zones within community lands as OECMs (Level 3—potential contribution) [,].

The Peru government reports all areas in the SINANPE to the WDPA. It also reported two conservation concessions to WD-OECM. Although these two concessions are not community-managed, it indicates the possibility for community-managed forest concessions (for conservation, ecotourism and non-timber forest products) to be registered and reported as an OECM []. In addition, the Autonomous Territorial Government of the Wampis Nation reported their traditional territory—Wampis Territory (Iña Wampisti Nunke)—to the ICCA registry and to WDPA as a “non-state protected area” []. The Traditional Territory covers a large area under a mix of tenure arrangements and designations (PAs, titled community lands, etc.) per national system and is not recognized as a whole by the national government.

Peru also has large Indigenous reserves/Territorial reserves for Indigenous peoples in isolation or first contact, designated and administered by the Ministry of Culture based on Law No. 28736 (2006). While they are not part of SINANPE or reported to WDPA/WD-OECM (thus Level 3/4, potential/hindered contribution), such designations introduce restrictions on activities such as logging, mining and extractive industries, hence are likely ancillary conservation [].

Overall, the recognition of Indigenous territory and rights, as well as their contribution to conservation in Peru, is still evolving (Figure 2). Despite ongoing efforts, several barriers impact the effective protection and reporting of IPs and LCs lands in Peru. Challenges include inadequate legal recognition of Indigenous land rights, limited resources for community management and disputes over land tenure []. These issues can hinder the recognition and effective management of these areas.

Figure 2.

Possible pathways of recognizing Indigenous land and reporting to the World Database on Protected Areas (WDPA) in Peru (blocks in blue: designations of recognized Indigenous lands; blocks in green: designations reported to the WDPA).

4. Discussion

4.1. Tenure Security and Reporting Mechanisms as Drivers of 30 × 30 Progress

Achieving the ambitious Target 3 of the GBF requires equitable governance frameworks that extend beyond state-owned and solely governed protected areas. Studies show that IPs and LCs steward at least 45% of global lands through customary or traditional tenure systems []. Yet, in many cases, these territories remain under-recognized in national area-based conservation accounting and, therefore, not incorporated in related global protected and conserved area databases []. Tenure security provides a key pathway for local and Indigenous communities to voluntarily participate in area-based conservation and to be included in national systems of protected and conserved areas [].

Critically, legal recognition of tenure rights, particularly ownership and stewardship rights, emerged as the strongest predictor of whether IPs and LCs lands are formally being accounted for in the WDPA or WD-OECM, as has previously been shown in other studies at a national level (e.g., []). For instance, in the 18 countries we assessed, over half the lands are formally recognized (through issuing of land title deeds or communities registering their customary lands with the government). Ten surveyed countries where Indigenous peoples or communities have full tenure rights of their lands and seven surveyed countries with private tenure were formally recognized and were reported to the World Database on Protected Areas (WDPA) compared to territories reliant solely on customary tenure. For Indigenous lands, full ownership rights correlated with direct reporting to WDPA (10/18 countries), whereas partial rights (e.g., holder or manager) resulted in inconsistent reporting (7/18 countries). Conversely, territories reliant solely on customary tenure may be reported to WDPA but they are often reported as state/public lands. This disparity underscores how insecure land tenure can jeopardize the agency of IPs and LCs and potentially biodiversity outcomes, as unrecognized lands can face heightened risks of land conversion and are not able to demonstrate the long-term conservation intent and permanence required for recognition as a protected area or OECM (e.g., [,]).

Our findings, however, reveal that the contribution of IPs and LCs to percent coverage elements of national and global protection targets not only depends on tenure type but also on governance rights, despite the way it is reported in these databases (i.e., as ITTs or PA or OECM). The IUCN report on Indigenous and Community Conserved Territories and Areas (ICCAs) overlapping with protected areas shows that they may occur in all four protected area governance types (i.e., state/public, private, communal or shared) [] indicating that there is room for enhancing the participation of IPs and LCs in decision making.

Across the 18 countries assessed, IPs and LCs held holder rights (4 countries), manager rights (10 countries) or user rights (4 countries) on state-owned lands, enabling collaborative governance despite state ownership (e.g., co-management agreements in Kenya, Indonesia and Australia). Evidence suggests that 26% of terrestrial protected areas globally overlap with ICCAs; while, in some cases, the overlap and the designation of a protected area in an ITTs is consensual, in others, it generates land dispossession from IPs and LCs or other state interventions []. Countries like Canada, India and Peru exemplify pathways to reconcile these overlaps through shared management frameworks. However, progress on co-management agreements remains uneven.

4.2. Barriers to Reporting and Policy Implications

Based on our findings, we categorize systemic barriers and opportunities that have implications for IPs and LCs contributions to 30 × 30 goals. These are as follows:

- Legal Paradox: Customary tenure systems lack parity with statutory land rights in most nations, excluding ITTs/ICCAs from WDPA reporting (e.g., community forests in Indonesia, untitled conservancies in Kenya and India’s community reserve on community land are not reported).

- Inconsistent Designations: National interpretations of “protected or conserved area” vary widely. Belize designates Indigenous-governed state lands as national parks (e.g., Rio Blanco) (Hidden contribution of IPs and LCs to Target 3 of the GBF), while Brazil and Australia include and report Indigenous territories as formal protected areas within their national system of protected areas [,].

- Political Resistance: The duality between state and sovereign Indigenous territories [] still plays out in the inclusion and participation or not of IPs and LCs in the governance, management and monitoring of PCAs or the consideration of those ITTs in the national networks of PCAs, which all have consequences for the reporting to the WDPA.

- Reporting Actors and Structure: WDPA and WD-OECM do not currently contain all information pertaining to protected areas and OECMs. For instance, tenure is not among the information shown on the Protected Planet website, while governance is not always reported by governments or other data providers. A point to consider that is relevant to the contribution of ITTs is that data providers to both databases can be government actors and other individuals or organizations (e.g., NGOs, international secretariats, etc.). For instance, the self-declared Wampis nation in Peru is not recognized within Peru’s national protected area system, while still being recognized and included in WDPA reporting.

Addressing these challenges would require a significant level of political will, with consequent policy measures in place and the establishment of transparent dialogue channels with IPs and LCs. Firstly, countries should also adopt rights-based approaches to recognize lands as IPs and LCs territories, protected areas or OECMs through conducting a Free Prior and Informed Consent (FPIC), (voluntary) inclusion of Indigenous and traditional territories within a country’s national system of protected and conserved areas and expediting registration and legal recognition of (customary) land tenure for ITTs.

Secondly, the development of a standardized reporting system for ITT governance and tenure types to align with WDPA or WD-OECM submission processes could support better understanding of ownership/governance of reported lands. We propose that these areas are then reviewed through the four-tiered classification lens we outlined in this paper. We argue that the use of the four tiers would elicit IPs and LCs contribution in a fairer and more transparent fashion. An additional measure would be that countries prioritize governance models that resolve historical overlaps, as seen in Australia’s Indigenous Protected Areas. The IUCN’s new guidance on overlapping ICCAs and protected areas [] could be a good starting point to provide guidance on dealing with overlapped areas.

However, we suggest that the management category (i.e., IUCN protected area management category) or type of measure (protected area, OECM, or ITT) entitled to ITTs should be flexible to accommodate the views of individual IPs and LCs groups and national circumstances. Failure to address these priorities risks perpetuating the exclusion of IPs and LCs—stakeholders who already steward much of the earth’s biodiversity—from the very frameworks designed to safeguard it. The global heterogeneity of tenure systems precludes one-size-fits-all mandates for recognizing Indigenous and traditional territories in conservation reporting. Instead, locally tailored pathways, developed through partnerships between states, Indigenous Peoples and Local Communities, are essential to align conservation targets with cultural sovereignty and ecological stewardship. Rigid global criteria risk marginalizing customary systems that already sustain biodiversity.

Our findings provide new insights into the challenges of the reporting of ITTs in conservation databases and complement those reviewing successes, challenges and lessons from Indigenous protected and conserved areas [,] and challenges and opportunities that the new Global Biodiversity Framework may pose for ICCAs (e.g., []).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.L., C.H. and J.F.; Methodology, C.L., C.H. and J.F.; Data collection and analysis, C.L. and S.Q.; Writing—Original Draft Preparation, C.L.; Writing—Review and Editing, C.L., C.H., J.F. and S.Q. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

No new data was created in this research.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to acknowledge the technical support received from regional and country staff of The Nature Conservancy in 18 of the selected country sites, including Australia, Belize, Bolivia, Brazil, Canada, Colombia, Ecuador, Gabon, Guatemala, India, Indonesia, Jamaica, Kenya, Mexico, Peru, South Africa, the United States of America and Zambia. We thank four anonymous reviewers for helpful comments on an earlier version of this manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Data Collection Matrix

Box A1. Data collection Matrix.

1. Tenure

(a) What type of tenure (title) exists for IPs and LCs lands and territories in the country?

(b) How are IPs and LCs lands registered, and how do they operate to support the protection of biodiversity through area-based conservation?

(c) What type of tenure exists for IPs and LCs lands (as owners, holders, managers or users)?

(d) What rights do IPs and LCs have to land and resources (based on Access, Use, Management, Exclusion, Alienation rights)?

2. Governance

(a) Who has a say on how these lands are governed (based on the below governance regime)?

- ○

- Governance by government/State.

- ○

- Shared governance.

- ○

- Private governance.

- ○

- Governance by local communities.

- ○

- Governance by Indigenous peoples.

- ○

- Governance by Indigenous Peoples and Local Communities.

- ○

- Multiple governance.

3. Recognition

(a) How are ITTs recognized to contribute to area-based conservation (formal/informal recognition)?

- ○

- If formally recognized, what regulatory framework supports this recognition?

(b) Are ITTs recognized as part of the national protected area system/network in your country?

4. Reported towards 30 × 30 target

(a) Are ITTs considered protected areas (as reported in WDPA), OECMs (as reported in WD-OECM) or ICCAs (as reported in the ICCA registry)?

- ○

- If protected areas, what IUCN protected area management category are they assigned?

(b) Under what conditions do the recognized ITTs count to contribute to area-based conservation?

(c) Who or what government or non-government entity reports these lands and territories to WDPA/WD-OECM?

5. Conservation management regime

(a) Do IPs and LCs have the agency/are they entitled to set management directions and develop management plans/other instruments?

6. Biodiversity management and compliance

(a) How are ITTs reporting on their biodiversity conservation outcomes and to who?

7. Finance

(a) What are any existing finance sources and other means of support for ITTs?

8. Barriers

(a) What are the barriers to ITTs contributing to 30 × 30?

9. Opportunities

(a) What are the highest value changes needed to see recognition of ITTs towards 30 × 30?

Appendix B

Table A1.

IPs and LCs tenure rights and the corresponding national rights.

Table A1.

IPs and LCs tenure rights and the corresponding national rights.

| Tenure Regimes | IPs and LCs Associated Tenure Rights | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Owners | Holders | Managers | Users | |

| State/public land tenure | - | Canada—crown land with designated use, some are co-management with the state Peru—Indigenous reserves and territories to protect IPs in isolation USA—as trust lands for native American nations India—under the Scheduled Tribes and Other Traditional Forest Dwellers | Australia—native title on crown land Indonesia—co-management with the state and with a 35-year management permit Jamaica—co-management agreements with community groups managed by NGOs Kenya—co-management agreements on public land, e.g., state forests Guatemala—in multiple-use area USA—co-steward of federal lands USA—tribal conservation districts Zambia—communities can co-manage on state lands through the forest act and the wildlife act Belize—govt enters into 5-year co-management agreement on management of national parks Brazil—as extractive reserves and as reserves for sustainable development project Peru—as communal reserves South Africa—co-management with the state, e.g., forest resources | Australia—non-exclusive native title on Crown land Gabon—communities have customary use rights to public land, e.g., forests USA—traditional territories and ceded lands with access to hunt, fish, etc. Belize—access and use of natural resources on state land Peru—user rights on state land such as Indigenous reserves and territories Peru—as conservation concessions |

| Indigenous peoples and local community land tenure | Australia—with a conservation covenant on freehold land or as IPA designated with federal government Colombia—Indigenous territories and Afro-descendants communities with legal tenure title Indonesia—communal lands Kenya—titled and registered community lands can operate as community conservancies Belize—consent agreement with 41 Maya communities under customary tenure Ecuador—collective lands with titles Bolivia—native community lands—legally recognized with certification Peru—as native community land titles USA—as restricted fee lands/non-trust lands Mexico—as private parcels Ejido lands | Canada—Indigenous title Brazil—Indigenous lands legally demarcated and constituted territories Australia—exclusive native title as IPA or national park, Aboriginal freehold India—as a community reserve on community land—exclusive rights vary per state Guatemala—holders as community forests Mexico—community lands with collective tenure and as Ejidos on common lands Ecuador—Indigenous lands, Afro-Ecuadorian collective territories | Australia—non-exclusive native title, Indigenous land (Aboriginal land) India—as a community reserve on community land Zambia—manager of wildlife and forest through community forest management groups and the wildlife act South Africa—IPs and LC can participate on communal lands as biodiversity management areas, biodiversity agreements, conservation management areas, conservation management agreements and biodiversity partnership area Kenya—unregistered community lands can operate as community conservancies held in trust by the state Indonesia—as village forest, community partnership and community-managed forest | Brazil—traditional communities user rights Zambia—traditional user rights apply Colombia—Black community lands users of forest according to traditional practices |

| Private land tenure | Gabon—individuals or communities have a right to own land—no legislation guiding area-based conservation on private land Jamaica—on forest management area and privately managed Kenya—can participate as group conservancies or conservancies on private land Guatemala—legal titles through cooperative and family-owned forest USA—as Alaska native corporation lands USA—as fee simple lands South Africa—as communal property associations on private lands Australia—through a conservation covenant on freehold title | India—community reserve on private land—exclusive rights vary | India—community reserve on private land | |

Table A2.

IPs and LCs tenure and tenure rights in relation to the level of contribution and reporting to national 30 × 30 reporting.

Table A2.

IPs and LCs tenure and tenure rights in relation to the level of contribution and reporting to national 30 × 30 reporting.

| Country | Tenure That Supports Area-Based Conservation for IPs and LCs | National Legal Framework That Recognizes ITTs in Area-Based Conservation | Ways in Which ITTs Are Nationally Recognized in Legislation and Contribute to Area-Based Conservation Efforts | What Bundle of Rights Do IPs and LCs Have to Contribute to Area-Based Conservation | Level of IPLC Contribution to 30 × 30 | Recognized ITTs That Are Not Yet Contributing to 30 × 30 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gabon | None for IPs and LCs specifically; the Constitution stipulates that every individual or community has the right to own land; however, Ordinance 005/PR/2012 of 13 February 2012 established the land ownership regime in Gabon, but it only governs individual land ownership through the land registration procedure; there are no specific property acquisition procedures for IPs and LCs | No existing legislation in Gabon | None mentioned | User—IPs and LCs have access rights | Hindered contribution | Unclear at the moment |

| Kenya | Freehold customary tenure on community land Freehold and leasehold on private land Co-management agreements on public/state land | Yes– Community Land Act CAP 287 Wildlife Conservation and Management Act, 2013 | As wildlife conservancies As group ranches As community forest associations or as local managed marine areas (LMMAs) | As owners of community wildlife conservancies, as owners of private conservancies, as co-managers of forest reserves with the state and local managed marine areas | Full contribution if IPs and LCs have registered their community lands or have a communal title over their community lands Full contribution if IPs and LCs have private land title | Unregistered community lands that have customary tenure, i.e., lands within Level 3 contribution |

| South Africa | Community lands, i.e., communal or traditional lands under traditional chiefs Private lands—communal property associations | National Environmental Management Biodiversity Act 10 of 2004 Contract law Informal agreement National Environmental Management Protected Areas Act (Act 57 of 2003) Traditional Leadership and Governance Framework Act of 2003 | Community lands that are registered to support area-based conservation operate as biodiversity management areas; biodiversity agreements, conservation management agreements; and biodiversity partnership areas | User rights on community lands Owner on private lands | Hidden contribution on community lands, as no category supports ITTs lands on its own or governance by IPs and LCs to be formally recognized and reported within national systems; hence, ITTs need to partner with state or private entities Full contribution on private lands where IPs and LCs enter into agreements with state/private entities and have land titles, e.g., Babanango Game Reserve | |

| Zambia | Customary tenure on community land Statutory tenure on state/crown land (leasehold) | Land is customary held by communities; no formal documentation on customary land; however, the law allows for co-management rights with the state, i.e., Wildlife Act, 2015 Forest Act, 2015 | As community partnership parks As game management areas Community forest management groups | User and management rights User rights on statutory tenure on crown land | Hidden contribution—as ITTs on customary lands, the tenure is not formally recognized, and hence, they often partner with the state or with private entities, e.g., NGOs | |

| India | Community land Private land | Yes Wildlife Protection Act, 2002 | Community reserve on community land or private land | Yes Managers of community reserves, though they are not reported in WDPA | Potential contribution—the land tenure as ITTs in the form of community reserves have not been reported to WDPA so far It is also likely that lands are not recognized as ITTs but rather as lands that are volunteered for wildlife protection given that the village/state oversee the management of these lands | The reporting system on WDPA is unclear if reporting is only based on state land, as there is no indication of ITTs lands reported; it is likely that the ITTs are Level 3 contributions |

| Australia | Private land Exclusive native title Non-exclusive native title Indigenous land (Aboriginal land) Crown land with application of native title rights | Act of Parliament at the state (subnational) level Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (EPBC Act) Native Title Act 1993 | Application of a conservation convent on private land Indigenous protected areas (IPAs) | IPs have rights through private lands as owners or through exclusive native title as holders; as users in non-exclusive native title; as holders in Aboriginal freehold; as managers on native title on crown land (national park) | Full contribution—if owners or holders | |

| Indonesia | Community tenure Customary forest | Ministerial decree no 17 of 2020 Article 5 Basic Agrarian Law of 1960 Law no 5/1967 article 17 Law no 41/1999 article 34 and article 37 Constitutional Court decision no 35/PUU-X/2012 of May 2013 | Customary forest, village forest, community forest, community partnership, community-managed forest; it is unclear if these systems are considered for area-based conservation as opposed to just for conservation | Yes Managers of co-managed forests | Potential contribution—while the forests are recognized by law, it is unclear if they are also recognized as land counting towards area-based conservation in Indonesia; these lands are also not reported to the WDPA; the tenure of these lands is unclear as between the state/community | It is unclear if community forests would be considered to contribute to area-based conservation, although recognized by law; it is unclear if they are not counted because of the scale of these lands, i.e., too small to be counted |

| Jamaica | It is unclear the state of IPs in Jamaica; also, the term community is not applied widely in Jamaica, hence most land is considered either family land or private land, aside from state land; no legislation that is specific to IPs and LCs tenure | No legislation that is specific to IPs and LCs tenure; however, there are co-management agreements with community-based organizations or non-government organizations | None mentioned; only co-management agreements on state land are mentioned | Yes As co-managers of protected areas, e.g., forest reserves; community land not reported in WDPA | Hindered contribution—no specific IPs and LCs tenure that is recognized in Jamaica and more so that supports area-based conservation; communities participate through co-management agreements through community-based organizations; it is unclear how communities benefit from area-based conservation | |

| Belize | No specific IP tenure Government-owned lands that overlap with IP claimed land | None mentioned, as IP lands are not recognized | None | Yes, through governance (sometimes co-management) of national protected areas, e.g., parks but owned by government; reported in WDPA but under state with IP governance | Hidden contribution | |

| Bolivia | Some peasant native Indigenous Territories (Territorio[s] Indígena Originario Campesino[s]/TIOC[s]) such as the Isiboro Sécure National Park and Indigenous Territory (TIPNIS) | Law No. 1715 in 1996 Decree No. 727/10 Bolivian Constitution 2009, Article 403 recognizing TIOCs | Native community land (Peasant Native Indigenous Territories/Territorio Indígena Originario Campesino [TIOC]) | Yes, they are owners of the land and territories; those IPs and LCs lands are not reported to WDPA (unless with national PA designations), but some are reported to the ICCA registry | Full contribution for specific cases, such as Isiboro Sécure National Park and Indigenous Territory (TIPNIS), which was originally designated as a national park (in 1965) and later (in 1990) recognized as Indigenous land, which makes it a full-contribution case Potential contribution; most TIOCs are not reported as protected areas yet (as some lands overlap with protected areas, hence official count on how to deal with overlaps is not yet clarified) | Native community land (Peasant Native Indigenous Territories/Territorio Indígena Originario Campesino [TIOC]) |

| Brazil | Demarcated Indigenous lands; Quilombos (communities formed by African slaves that fled farms and other places of forced labor during colonial and imperial periods) | Brazil 2006 National Protected Areas Plans Brazil 2016 NBSAP | Indigenous lands; Quilombos are not yet reported to WDPA | Yes, they are part of national system of protected areas IP are holders of IP lands | Full contribution for Indigenous lands; potential contribution for lands such as Quilombos, which are not reported as PA but have potential to be reported as OECMs; hindered (for IPLC lands not titled yet) | Quilombos are recognized and included in the national protected area system as it is, per Brazil National Biodiversity Strategies and Action Plans (NBSAPs), but not yet in WDPA |

| Colombia | Resguardo Indigena (Indigenous reservation) Tierras de las Comunidades Negras (Black community lands) | Decreto 2372 de 2010 (art. 14) Decreto 1384 de 2023 Ley 70 de 1993 | As Indigenous reserve for IP lands As ICCAs and community conserved area for community land | IP are owners of their land but not included in the national system of protected areas; also, governance is by government with community participation | Hidden contribution | Indigenous reserves and Black community lands out of existing PAs |

| Ecuador | Territorios Indigenas (Indigenous Territories) Socio Bosques Comunitario Territorios (community forest partner territories) Afroecuatorianos Zonas Intangibles (Afro-Ecuadorian intangible areas) | Ecuador Constitution, Ley forestal y de conservación de áreas naturales y vida silvestre (https://faolex.fao.org/docs/pdf/ecu67393.pdf accessed on 3 March 2025). | As community protected areas in the National System of Protected Areas As non-state PAs reported through ICCA | IPs and LCs are holders/owners of the land but not included in the nation system of protected areas; PA designations and Indigenous territory designations can overlap; Indigenous territories within the national PAs are reported to WDPA as state PAs | Full contribution (community PA) Hidden contribution (territories overlapping with state PAs) Potential contribution | Indigenous reserves and community lands out of existing PAs |

| Guatemala | Tierras comunales (community forests) Municipal Communal (municipal community forests) | Not recognized | Not mentioned | IPs are holders of the community forest but not recognized; some community forests overlap with protected areas, but IP contribution is not counted in such cases for 30 × 30 | Hindered contribution | |

| Mexico | Ejido lands (community lands) | Article 59 of the Ley General del Equilibrio Ecológico y Protección al Ambiente National Political Constitution of the United States of Mexico | Ejido lands (community lands) | Yes, they can voluntarily register with the National Commission of Protected Areas (CONANP) to register portions of their community lands as Voluntary Conservation Areas; they are also part of the national system of protected areas through a certificate issued by the ministry of environment and natural resources | Full contribution as OECMs | |

| Peru | Comunidad nativa (native community land title) Comunidado campensino (peasant community land title) Territorio tradicional indigena (Indigenous traditional territory) Reservas indigenas (Indigenous reserves) Reservas Territoriales (territorial reserves) | Law 26834 Supreme Decree 038-2001-AG Presidential Resolution 144-2010-SERNANP (Repealed) Presidential Resolution 199-2013-SERNANP Laws allowing the creation of Private Conservation Areas, 1997, 2001, 2010 and 2013 | Some titled community lands are registered as ACP Área de Conservación Privada (private conservation areas) governed by local communities Traditional territories can, in some cases, be designated as Communal Reserves, which are part of the national PA system (in which case they are state lands and governed by SERNANP and co-managed with communities) Traditional territories declared by Indigenous autonomous governments can, in some cases, be reported to WDPA through ICCA registry | Titled land recognized through privately protected areas—owner Traditional territory through communal reserves—manager Traditional territory overlapping with state PAs—user Traditional territory through ICCA—a mix of owner, user, customary manager and lack of rights | Full contribution (for local community-governed private protected areas; Indigenous territories reported through ICCA); hidden contribution (for PAs co-managed by communities); potential contribution (Wampis nations lands as potential contribution) | Indigenous reserves and territorial reserves are not contributing to 30 × 30, as they are currently classified as culture protection, not nature protection |

| Canada | Crown land with designated use—co-management with the state Indigenous title on Indigenous Protected and Conserved Areas (IPCAs) | Indigenous legal systems Section 35 of the Canadian Constitution protects Indigenous rights IPCAs struggle with recognition from the crown government as a form of protected area Common law—peace treaties and agreements, e.g., Yukon territory agreement, Nova Scotia agreement, Newfoundland/Labrador agreement | IPCAs—Indigenous protected and conserved areas Conservancies with First Nations Parks—with partnership between Indigenous nations and the federal/provincial/territorial governments—can be as parks, heritage sites, reserve or national marine conservation area reserve IPCAs with crown designation | IPCA—Indigenous rights as holders of the land Indigenous rights within crown lands (right to hunt, fish, trap, etc.) Managers—co-management rights of protected areas and partnership agreements | Potential and hidden contribution—some IPCAs are recognized, but they do not count towards the nation’s 30 × 30 due to difficulties with the crown governments regarding titling While some IPCAs are recognized by law, in practice, they do not contribute to area-based conservation, as conflicts between Indigenous nations and provincial/federal states exist on tenure and tenure rights over the lands and perceived impact on economic growth within these states vs. indigenous rights Full contribution—for IPCAs that are designated | Many IPCAs are struggling to be recognized by the state due to underlying title and rights issues, distrust of crown decision-makers, conflicting land visions, among others |

| USA | Trust lands for Native American nations Co-steward of federal lands Tribal conservation districts Traditional territories on ceded land Restricted fee lands/non-trust lands (private) As Alaska native corporation (private) As fee simple lands (private) | Various legal frameworks exist— Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act of 1971 1975: Indian Self-Determination and Education Assistance Act (ISDEAA) 1994: Tribal Self-Governance Act amended ISDEAA 2004: Tribal Forest Protection Act 2021: USDA and Department of Interior (DOI) issued Secretarial Order (S.O.) 3403 2022: Forest Service “Strengthening Tribal Consultation and Nation to Nation Relationships” action plan | As natural areas, wilderness, conservation easement | IPs have rights through private lands as owners or through trust lands as holders, co-stewardship as managers, access rights through traditional territories | Full contribution if private land with title Potential contribution for lands that are recognized by law but not reported; these include tribal conservation districts, trust lands and traditional territories that are not reported | The USA reported to WDPA, but it is not party to the CBD; the USA had its own target through a program known as America the Beautiful, aimed at 30 × 30 protection, though not associated to the CBD |

Appendix C. Identifying IPs and LCs Contributions in WDPA and WD-OECM

We used the attributes “OWN_TYPE”, “GOV_TYPE” and “MANG_AUTH” of the WDPA and WD-OECM database to identify area-based conservation that is reported as IPs and LCs contributions. Specifically, we considered two sets of criteria to identify full IPs and LCs contributions in WDPA/WD-OECM:

(1) Explicit full IPs and LCs contributions, including those areas with either Governance by Indigenous Peoples and Local Communities, or Ownership by Indigenous peoples of communal, i.e., (GOV_TYPE IS “Local communities” OR “Indigenous peoples”) OR (OWN_TYPE IS “COMMUNAL”).

(2) Explicit partial IPs and LCs contribution, including records that have either shared governance or joint ownership, and with “Indigenous/Communal” as Management Authorities, i.e., (GOV_TYPE IS “Joint governance” OR “Collaborative governance” OR “Government-delegated management” OR “Not Reported”) OR (OWN_TYPE IS “Multiple ownership” OR “Joint ownership” OR “Not Reported”) AND (MANG_AUTH CONTAINS “commun”,”comun”,”indig”,”first nation”).

Records meeting these criteria are listed in the Tab of “IPLC_in_WDPAWDOECM” summarized in the table below.

Table A3.

Designations under which IPs and LCs lands are reported as full or partial IPs and LCs contributions in WDPA/WDOECM and their tenure regimes.

Table A3.

Designations under which IPs and LCs lands are reported as full or partial IPs and LCs contributions in WDPA/WDOECM and their tenure regimes.

| Designations of IPs and LCs Contribution as Reported to WDPA/WD-OECM | No. of Reported Areas | Coverage of Reported Areas (km2) | Tenure Regime |

|---|---|---|---|

| Australia | 98 | 874,200.75 | |

| Indigenous Protected Area | 98 | 874,200.75 | Indigenous/communal |

| Belize | 10 | 346.82 | |

| National Park | 5 | 210.69 | State |

| Private Reserve | 2 | 53.69 | Private |

| Wildlife Sanctuary | 3 | 82.45 | unknown |

| Brazil | 720 | 1,134,730.32 | |

| Historical and Cultural Heritage Site | 1 | 2816.32 | Indigenous/communal |

| Indigenous Area | 700 | 1,128,244.17 | Indigenous/communal |

| Indigenous Reserve | 19 | 3,669.83 | Indigenous/communal |

| Canada | 89 | 132,220.48 | |

| Conservation Zone in Regional Land Use Plan | 45 | 35,925.14 | Multiple |

| First Nation Settlement Land | 2 | 4090.46 | unknown |

| Habitat Protection Area | 9 | 2836.85 | Multiple; State; unknown |

| Heritage Conservation Zone in regional land use plan | 13 | 137.07 | unknown |

| Indigenous and Territorial Protected Area | 2 | 19,216.14 | State |

| Land Use Exclusion Zone in Indigenous Land Use Plan | 1 | 976.87 | unknown |

| Protected Area—Far North | 4 | 8807.42 | State |

| Protected Through Indigenous Land Claim Agreement | 1 | 272.64 | State |

| Protected Through Indigenous Land Claim Agreement—Heritage Resource | 1 | 1375.82 | State |

| Territorial Park | 4 | 11,433.43 | State |

| To Be Determined | 5 | 35,556.62 | Joint/multiple; State |

| Traditional Conservation Area | 1 | 8471.96 | State |

| Wildlife Conservation Area | 1 | 3120.06 | State |

| Colombia | 3 | 301.92 | |

| Community Conserved Area | 1 | 1.35 | Indigenous/communal |

| ICCA | 1 | 215.79 | Indigenous/communal |

| Indigenous Reserve | 1 | 84.77 | Indigenous/communal |

| Ecuador | 3 | 3802.88 | |

| Community Protected Area | 1 | 54.95 | Indigenous/communal |

| Living Forest of Sarayaku | 1 | 1426.26 | Indigenous/communal |

| Living Forest of Sarayaku (non-state protected area) | 1 | 2321.66 | Indigenous/communal |

| Guatemala | 2 | 1.61 | |

| National Park | 1 | 1.50 | State |

| Private Natural Reserve | 1 | 0.11 | Indigenous/communal |

| Kenya | 62 | 32,450.50 | |

| Community Conservancy | 13 | 1124.07 | Communal or Private |

| Community Forest Reserve | 11 | 1020.15 | Communal |

| Community Nature Reserve | 27 | 30,017.33 | Communal or Private |

| Community Wildlife Sanctuary | 1 | 222.53 | Communal or Private |

| Group Ranch | 1 | 66.42 | Communal or Private |

| Locally Managed Marine Area | 9 | - | Communal or Private |

| Peru | 63 | 17,211.69 | |

| Private Conservation Area | 62 | 3759.69 | Indigenous/communal |

| Wampis Territory (non-state protected area) | 1 | 13,452.00 | Indigenous/communal; Multiple |

| USA | 4 | 389.29 | |

| Conservation Easement | 1 | 0.13 | State |

| Natural Area | 2 | 16.85 | State |

| Wilderness | 1 | 372.31 | State |

| Grand Total | 1054 | 2,195,656.25 |

NB: No explicit contributions from IPs and LCs was listed in the remaining 8 countries, i.e., Bolivia, Gabon, Guatemala, India, Indonesia, Jamaica, Mexico and South Africa.

References

- WWF; UNEP-WCMC; SGP/ICCA-GSI; LM; TNC; CI; WCS; EP; ILC-S; CM; et al. The State of Indigenous Peoples’ and Local Communities’ Lands and Territories: A Technical Review of the State of Indigenous Peoples’ and Local Communities’ Lands, Their Contributions to Global Biodiversity Conservation and Ecosystem Services, the Pressures They Face, and Recommendations for Actions. 2021. Available online: https://wwfint.awsassets.panda.org/downloads/report_the_state_of_the_indigenous_peoples_and_local_communities_lands_and_territor.pdf (accessed on 2 April 2025).

- Krogh, A. State of the Tropical Rainforest. The Complete Overview of the Tropical Rainforest Past and Present; Rainforest Foundation: Oslo, Norway, 2021; Available online: www.rainforest.no/en (accessed on 2 April 2025).