Abstract

Rural areas exhibit a high prevalence of poverty. As significant progress in poverty reduction has been achieved, research on rural livelihoods has transitioned from a focus on poverty eradication to preventing poverty recurrence and fostering development. Development resilience, which has emerged as a pivotal research area in poverty governance, is a crucial metric for assessing rural households’ long-term capacity to avoid falling back into poverty, considering the multi-dimensional aspects of poverty and welfare dynamics. Utilizing data from the Academy of Agricultural Sciences, this study investigates the impact of land inflow on rural household’s development resilience (RHDR). Findings reveal that land inflow significantly enhances RHDR, a conclusion that holds after extensive robustness checks. Mechanism analysis shows that while land inflow initially imposes a financial burden, it eventually acts as an exogenous driver and causes labor force return and economies of scale, boosting RHDR over time. This effect is more pronounced among non-vulnerable households, those with abundant water resources and strong collective awareness. Therefore, it is recommended to refine land inflow systems, reduce barriers to land resource flow, and implement targeted support for vulnerable groups during the initial stages of land inflow to effectively promote rural revitalization through land transfer.

1. Introduction

Small and medium-sized rural households are the main group of agricultural management and also the “high incidence area” of poverty. While the “anti-poverty” campaign in China and poverty control efforts in other countries have effectively mitigated absolute poverty among peasant households, the persistent issue of multidimensional poverty remains prevalent []. The 2023 Global Multidimensional Poverty Index (MPI) report by the United Nations Development Program (UNDP) reveals that 25 countries have reduced the incidence of multidimensional poverty by half over the last 15 years. Nonetheless, out of the 6.1 billion individuals included in the report, 1.1 billion remain impoverished, with 84% of them residing in rural regions, underscoring the persistent challenge of poverty alleviation in rural areas []. The reason lies in that the goal of addressing absolute poverty often emphasizes short-term external subsidies and material aid, neglecting the multifaceted nature of poverty [,]. While income is a crucial factor, elements such as educational opportunities, health standards, and access to public services are equally essential in poverty governance []. Recent studies on rural households’ livelihoods have shifted towards the concept of multidimensional poverty; evaluation systems largely emphasize constructing indicators of multidimensional poverty vulnerability [,,,,,]. These indicators assess rural households’ capacity to resist risks and organizations’ ability to secure external resources during crises [,]. However, they overlook rural households’ intrinsic motivation for development, leading to a lack of sustained measurement effectiveness [,,]. The situation is very likely to occur: rural households often demonstrate strong short-term resilience, yet the long-term risk of reverting to poverty remains, challenging the sustainability of their capacity to prevent return to poverty [,,,]. In this context, rural household development resilience (RHDR) is used as a measure of rural household long-term risk resistance, self-organization and endogenous development dynamics [,], which is of great significance for its in-depth study in the fields of effective governance of multidimensional relative poverty and enhancement of smallholder development potential and has gradually attracted the attention of academic circles. Furthermore, how to effectively improve RHDR has also become an important direction of current policy efforts.

The land circulation strategy, as a fundamental component of agricultural production, significantly influences rural households’ agricultural management, employment patterns, and risk mitigation strategies, thereby playing a crucial role in rural households’ survival and advancement [,]. The Chinese government places considerable emphasis on land circulation, continually enhancing related systems and policies through exploration and pilot initiatives []. The household contract responsibility system, introduced alongside economic reforms, dismantled the “dual rights” barriers in land ownership. This system enables rural households to access collective land ownership for contracting and management rights, thereby freeing up agricultural labor and facilitating poverty alleviation and prosperity. As societal focus on market economy reforms intensifies, land circulation rights are progressively relaxed []. In 2004, the State Council (SC) issued the Decision on Deepening Reform and Strict Land Management (DDRSLM), which allowed the legal transfer of rural collective construction land use rights. This policy enabled rural households to adjust their land use according to their actual needs []. Since the new era, the Chinese government has attached great importance to land circulation and regarded it as an important starting point for winning the fight against poverty and consolidating the effective link between poverty alleviation achievements and rural revitalization []. After the registration and certification movement aimed at “confirming the right and issuing iron certificates” to rural households, the “separation of three rights” of collective ownership of land, rural households’ contracting right and management right, and the extension of 30 years after the expiration of farmland contracting right have further ensured and consolidated rural households’ land rights and interests, and the land circulation market has flourished [,]. By 2020, 1239 counties (cities and districts) and 18,731 towns and townships across the country have established rural land management right transfer service centers. The area of household contracted cultivated land transfer nationwide exceeds 555 million mu, exceeding 30% of the contracted land []. There is no doubt that land circulation has become an important part of the livelihood strategy of rural households. As a key step to expand agricultural scale management and develop modern agriculture, land inflow has become the main channel for more and more farmers to develop advantageous industries and realize poverty alleviation and prosperity [,,]. Many rural households have formed cooperatives independently or in collaboration with others, pooling the land resources to achieve large-scale operations through collective efforts [,]. Data from the China Rural Management Statistics Annual Report (2018) indicates that by the conclusion of 2018, cooperative organizations had acquired 121 million mu of land, surpassing the combined land acquisitions of enterprises and other entities []. As a necessary path to promote the appropriate-scale operation of agriculture and the development of modern agriculture, land inflow has also become an important part of rural households’ livelihood strategies.

With the deepening of the general trend of land transfer, the discussion on the effect of land inflow on poverty reduction has intensified; therefore, will it have an impact on RHDR? Theoretically, on the one hand, risk resistance is an important element of RHDR, which measures the buffer capacity of rural households when they encounter risks. Land inflow is essential for rural households to transition to modernized agriculture and establish new agricultural management entities. Previous studies have extensively examined its income-generating impact [,,,,], suggesting that land inflow can boost the income of rural households [,,], thereby improving their resilience to risks []. However, for small and medium-sized rural households, the high rental cost of land inflow can also cause a large debt burden, which in turn weakens their risk resistance []. On the other hand, land transfer, as a commercial endeavor, can stimulate rural households to enhance their network connections through self-organization and developmental capabilities []. Large-scale operations are pursued through land acquisition to achieve economies of scale and mitigate the burden of land rental expenses. Consequently, rural households are incentivized to acquire agricultural expertise to enhance the enduring profitability of land management, thereby bolstering their long-term developmental capacity. However, at the same time, the increase in natural risk exposure brought about by the scale of land management will also bring more uncertainty to rural households. In addition, some scholars have discussed land inflow’s policy effects, social security, physiological health, etc., which may have an indirect impact on RHDR [,]. It can be seen that the theoretical impact of land inflow on RHDR is more complex and worthy of in-depth study, and the specific impact mechanism has not yet been discussed by the relevant literature. This paper will try to answer the above questions and put forward relevant suggestions on how to better play the role of land transfer in poverty reduction in rural areas.

2. Literature Review

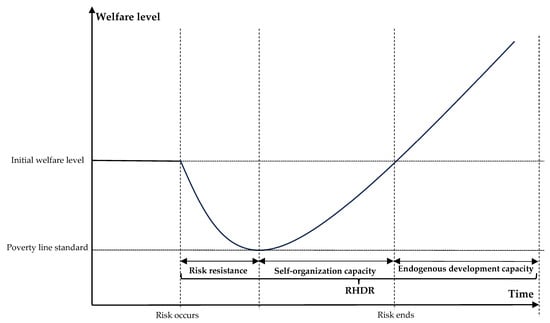

Development resilience, stemming from the concept of resilience [,], denotes the capacity of individuals, families, or other entities to sustain a heightened state of well-being and prevent descending into poverty following exposure to diverse stressors and multiple shocks []. In the existing poverty research fields, poverty vulnerability (PV) and household development resilience (HDR) are both important concepts in the field of household livelihood research. Prior to the introduction of HDR, research in the multidimensional poverty domain primarily focused on PV indicators. While HDR shares a forward-looking and dynamic nature with PV indicators, its emphasis differs. PV assesses the likelihood of a family descending into poverty in the future, concentrating on predicting poverty in advance and the self-protective capacity of individual families when faced with risks [,]. However, HDR encompasses not only the prediction of poverty occurrence but also the capacity of individual families to prevent a recurrence of poverty over an extended period. It assesses the resilience of households not only at the onset of a crisis but also their capacity for self-adjustment during the event and their intrinsic capability for post-event development to prevent reversion to poverty in a longer period [,]. Based on this basic concept, Speranza et al. (2014) categorize HDR into three dimensions: risk resistance, self-organization capacity, and endogenous development capacity []. Among them, risk resistance highlights rural households’ capital as a buffer against potential risks. Self-organization capacity pertains to the ability to borrow and mobilize external resources when exogenous risks surpass internal defenses. Endogenous development capacity emphasizes self-learning and skill cultivation post-risk, aiming to enhance long-term risk resistance and self-organization, thereby preventing poverty recurrence. This framework, which also incorporates factors such as livelihood capital, external risks, and social environment, has served as a primary model for subsequent research on assessing and examining HDR [,,]. The HDR framework, in comparison to the preceding vulnerability analysis model, offers enhanced research dimensions and sophistication. However, due to its recent introduction, the research framework of HDR lags significantly behind that of PV in terms of maturity. Currently, investigations into household livelihood strategies, focusing on absolute poverty or multidimensional poverty, predominantly adhere to the PV framework [,,,,]. Only a few scholars consider development resilience as the primary livelihood objective of rural households, with their investigations encompassing topics such as new urbanization [], relocation [], targeted poverty alleviation [], consumption support [], and agricultural insurance []. However, there remains significant scope for exploration in the research field directly related to the endogenous influencing factors of farmers. With the effective management of extreme poverty in many regions in the 21st century, research on farmers’ livelihoods has transitioned from alleviating poverty to preventing it. Enhancing the resilience of vulnerable groups in family development has emerged as a critical contemporary concern.

A more vivid explanation of RHDR is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

A more visual division of RHDR. The figure is derived from the research conducted by Speranza et al., Barrett and Cissé et al. [,]. The Figure was inspired and based on the research conducted by Speranza et al. (2014), Barrett and Constas (2014), and Cissé et al. (2020) [,,]. This figure elucidates the diverse facets of RHDR actions across various stages of exogenous risks, aiming to enhance readers’ comprehension of RHDR.

Another body of literature relevant to this topic has examined the impact of land circulation on poverty reduction. Initially, when the primary goal was to reduce absolute poverty, research predominantly explored the effect of land circulation on increasing income for rural households. Many studies concluded that land circulation had a significant positive impact on income growth for peasants living in absolute poverty [,,,,]. Since the early 21st century, academic research on the poverty reduction impact of land redistribution in developing countries has transitioned towards a multidimensional poverty framework, as significant progress has been made in alleviating absolute poverty [,,,,,,]. Among them, part of the research examines the impact of land circulation on poverty reduction among rural households through a multidimensional poverty lens, focusing on addressing poverty vulnerability. Specifically, the study explores how land transfer initiatives can help alleviate educational poverty, facilitate the rational flow of urban and rural elements, and enhance social protection measures [,,]. Certain scholars employ the A-F method and entropy method to develop composite multidimensional poverty indicators for distinct poverty manifestations. They extensively analyze the impact of land circulation on alleviating relative poverty across various dimensions, including economic, individual, environmental, and social protection [,,]. However, both PV and composite indicators focus on the prediction and assessment of poverty occurrence in advance, without considering the organizational strength and endogenous development motivation of rural households at the time of poverty occurrence and for a long time after poverty occurrence, making it difficult to make a more comprehensive analysis of the poverty reduction effect of land circulation from the perspective of multidimensional poverty. The ongoing reform of land “separation of three rights” and the evolving land transfer market in China have brought about various challenges. Zhang et al. (2024) examined inter-provincial land disputes (LDI) in China and noted that rapid urbanization exacerbates land disputes, leading to spatially clustered conflicts []. Moreover, unchecked expansion of the land market can deplete the labor force, contributing to non-point source pollution in agriculture []. These are not conducive to the long-term development of land management.

Focusing on land transfer as a specific method, land outflow is acknowledged as an effective approach for poverty reduction and income enhancement. Previous studies have primarily examined how land outflow facilitates the expansion of non-agricultural employment [], narrows the income disparity between agricultural and non-agricultural sectors [], addresses poverty through education [], promotes the efficient allocation of urban and rural resources [], and highlights that farmers can free up agricultural labor by engaging in land transfer to generate rental income and surplus earnings, thus serving as a key pathway to poverty alleviation and wealth accumulation. Conversely, research on the poverty reduction effects of land inflows has been comparatively limited. Initially, only a few scholars noted that land outflows could enhance agricultural production value [,] and optimize the agricultural industrial structure [], thereby fostering wealth growth. However, as research has progressed, the focus has increasingly shifted to the poverty reduction potential of land inflows. Some scholars point out that land, as the most familiar business field and the most basic livelihood asset of farmers, has more obvious long-term benefits to vulnerable farmers than the single rent income brought by land outflow and has more lasting income increase benefits [,]. There are also scholars noting that land acquisition contributes not only to wealth accumulation but also serves as a critical safeguard for farmers’ food security [], facilitating poverty alleviation and laying the groundwork for sustainable future development [,]. Furthermore, land acquisition is essential for achieving economies of scale and advancing modern agriculture. Unlike short-term aid, it offers enduring benefits akin to the adage “teaching a person to fish is better than giving them fish” [].

To summarize, although the literature has studied the poverty reduction effects of land transfer in different poverty reduction target periods and has made relevant studies on the income-generating and poverty-reducing effects of different modes of land transfer, the indicators for poverty analysis are dominated by a single wealth-generating income and a multidimensional poverty index, which are difficult to reflect the ability of farmers to prevent the return of poverty for a longer period of time after encountering risks and do not have durability. Focusing on the different methods of land transfer, the existing literature also mostly studies the poverty reduction effect from the perspective of land outflow and seldom discusses the impact of land inflow on RHDR and its mechanism of action. In view of this, this paper tries to reveal the impact relationship and impact path between land inflow and RHDR at this stage, and the marginal contributions of this paper are as follows: firstly, it adopts the 2012–2021 household panel data of the Academy of Agricultural Sciences to explore the positive relationship between land inflow and RHDR and focuses on analyzing the heterogeneity of the effects of the two on different groups, which provides a diversified perspective for a comprehensive understanding of the micro-effects of land transfer. Secondly, unlike the vast majority of the previous literature that focuses on a single dimension of income or vulnerability, this paper explores the impact mechanism of land inflow on RHDR through theoretical analysis, combined with empirical research, thereby effectively complementing the existing literature on RHDR. These findings have significant policy implications.

3. Theoretical Analysis and Research Hypothesis

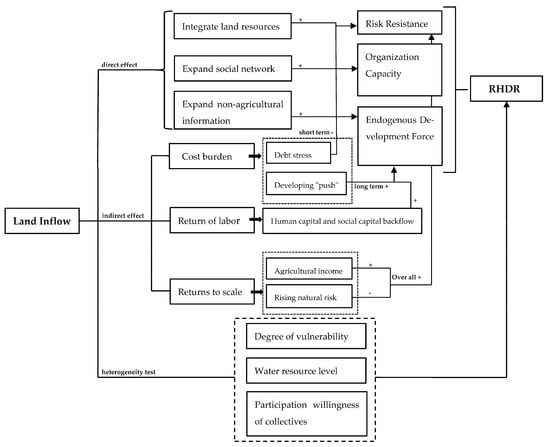

3.1. Direct Effects of Land Inflow on RHDR

Firstly, in the dimension of risk resistance, as land flows in, rural households can effectively consolidate their land resources, integrating fragmented and dispersed plots into cohesive units and carrying out large-scale operation, which not only reduces the cost of land management but also effectively improves the efficiency of agricultural machinery and contributes to the increase in agricultural production and income []. This will help to improve the welfare level of rural households and promote the enhancement of risk resistance [,]. Secondly, self-organizing ability is also an important part of RHDR. Land inflow, as a social resource transaction, enhances rural households’ neighborly relations and social networks during market inquiries and negotiations []. This expansion and strengthening of social ties enable them to access additional resources and support when confronted with external shocks, thereby increasing organizational capacity []. Finally, endogenous development capacity represents a crucial factor in ensuring the long-term welfare sustainability of rural households [,]. This capacity is evidenced by the ability of rural households to engage in self-directed learning following disruptive events. It is underpinned by the household’s reservoir of skills and knowledge, information obtained from diverse sources, and access to educational and training opportunities [,]. The substantial influx of land in urban and rural regions plays a crucial role in agricultural management by fostering commercial transactions, knowledge acquisition, and interactive communication among various stakeholders. This process empowers rural households to transcend the confines of rural settings, enhancing their exposure to information, comprehension of non-agricultural markets, and awareness of policy trends []. It also fosters rural households’ exposure to advanced science, technology, and market management practices, thereby enhancing rural households’ motivation for self-directed learning and endogenous development capacity. Analyzing the direct effects of land inflow reveals a significant positive impact on RHDR across these dimensions. Consequently, we propose hypothesis 1, which will be explored in subsequent chapters.

Hypothesis 1.

Rural households’ participation in land inflow contributes to their household development resilience.

3.2. Analysis of the Mechanism of Action of Land Inflow Affecting RHDR

3.2.1. Land Inflow, Cost Burdens and RHDR

The input cost of land inflow, including rental expenses and initial investment in scale management, such as machinery, seeds, and fertilizer, is always a key consideration for inflowing households. Small and medium-sized rural households, especially in rural areas, experience significant challenges in accessing and investing capital for land acquisition and production expansion. Despite the Chinese government’s efforts to promote inclusive financial services for these households, limited capital and high repayment risks hinder their access to affordable loans []. Consequently, the “impossible triangle” of financial inclusion is evident []. As a result, small and medium-sized rural households frequently prefer utilizing family assets or external staff transfers for financing. Regardless of the method of borrowing chosen, this strategy temporarily depletes the household’s available assets, consequently lowering its capacity to withstand risks. In the framework of HDR, the ability to withstand risks is paramount. Initially, the land inflow may diminish RHDR by imposing a greater financial burden related to land acquisition. Nevertheless, in the broader scope of rural household development, the expenses incurred from land inflow may serve as a catalyst for enhancing their self-development capabilities. Rural households must improve agricultural efficiency to repay initial debts or cover early input expenses. This necessitates proficiency in advanced management strategies, expansion of business operations and distribution networks, strategic farmland planning, and enhancement of agricultural mechanization. In the process of learning, their long-term endogenous development capacity—a key aspect of RHDR, strengthens. In summary, while the additional costs from land outflow have mixed effects on RHDR, rational households should thoroughly consider these financial pressures before acquiring land, ensuring that they are adequately prepared to endure the “pain period”. This is consistent with the Intertemporal Choice Theory (ICT) and would attenuate the adverse effects. Moreover, the Chinese government, which is attaching more and more importance to the development of the “Three Rural Areas”, will provide necessary financial subsidies and technological support tailored to rural households’ needs []. For example, in 2016, the Chinese government initiated a pilot program for mortgage loans on land management rights. This program allows rural households in designated areas to mortgage a portion of their farmland usage rights to access necessary funds, thereby addressing the challenges of limited and costly financing faced by agricultural operators []. In skills training, the 14th Five-Year Plan for Promoting Agricultural and Rural Modernization, released by the Chinese government in 2022, explicitly mandates the cultivation of over 1 million high-quality farmers []. This initiative encompasses various measures such as central agricultural subsidies (e.g., cultivated land protection subsidies, agricultural machinery purchase and application subsidies, wheat “one spray three prevention” subsidies), involvement of agricultural colleges and universities, collaboration with leading enterprises, and other training programs []. By 2023, 750,000 high-quality farmers will be cultivated nationwide []. These supports will also help households navigate the “pain period”, reducing the negative effects associated with land acquisition costs. Thus, we propose hypothesis 2.

Hypothesis 2.

The cost burden due to land inflow, while weakening risk resilience upfront, is conducive to rural household development resilience in the long run.

3.2.2. Land Inflow, Labor Returns and RHDR

Another consequence of land inflow is the return of laborers from outside the household. The increasing expansion of non-agricultural sectors driven by rapid urbanization has led to a rise in rural-urban migration among rural laborers in China. Consequently, rural land is frequently left fallow or deserted due to inadequate labor resources []. As the Chinese government promotes large-scale agricultural operations, an increasing number of rural households are venturing into land rental businesses. Rural households may face challenges in promptly adjusting their agricultural machinery and resources to meet the increased demand for labor due to the delayed adjustment and acquisition of fixed assets, such as agricultural machinery, in response to the expansion of land and the scale of production. Therefore, family members who have left for employment may be enticed to return to fulfill the labor requirements of the growing land management sector. On one hand, individuals engaged in non-farming work outside their homes typically possess advantages in age, physical fitness, expertise, interpersonal management abilities, and social networks compared to those involved in general family labor. Consequently, when these non-farming workers return to rural households from off-site employment, they bring with them a wealth of mobilizable high-quality human resources and enhanced social capital. This inflow ultimately bolsters the self-organizational capabilities of rural households. On the other hand, increased competition, improved professional skills, and the demands of urban relocation in non-agricultural sectors drive workers to boost their expertise, personal qualities, and overall knowledge, thereby enhancing their human capital. As a result, when labor returns due to agricultural needs, this enriched human and social capital will also benefit local agricultural production sectors. This, in turn, enhances their self-organizing ability and endogenous development capacity, which further contributes to the improvement of RHDR. From an opportunity cost perspective, labor returning from non-farm employment to agriculture may forgo non-farm income. However, agriculture, being a familiar domain for farm households, presents lower business risks compared to non-farm work. Additionally, skilled labor can enhance agricultural income. This will, to some extent, offset the welfare decline caused by the loss of non-agricultural income. Compared to short-term benefits, RHDR prioritizes long-term enhancements in preventing a return to poverty []. That means a family’s capacity for self-development is pivotal in averting poverty recurrence. Overall, the reintegration of labor into agriculture significantly bolsters RHDR. This effect is mainly reflected in the improvement of organizational and endogenous development capacity. Thus, we propose hypothesis 3.

Hypothesis 3.

Land inflow increases rural household development resilience by facilitating the return of labor from outside the household.

3.2.3. Land Inflow, Returns to Scale and RHDR

Rural households engage in land inflow primarily to increase the scale of their agricultural production and management, aiming to achieve economies of scale. Amidst swift urbanization, large-scale agricultural operations have become pivotal in the modernization of agriculture. The notion of “moderate scale operation” was first introduced by the Chinese government in 1987 in the No. 1 document of the Central Government, establishing a fundamental policy directive for guiding agricultural progress. Rural households integrate scattered plots by flowing into the land, which provides convenience for large-scale mechanized operations and rational planning of sowing and fertilizer layout, thus reducing unit agricultural costs and increasing unit yield [,]. These advantages will invariably enhance the welfare level of rural households, which in turn will promote RHDR. However, large-scale land inflow heightens rural households’ exposure to natural risks, particularly affecting small and medium-sized rural households. These households often lack the financial resources to quickly enhance their risk-resistant infrastructure, thereby diminishing their capacity to withstand such risks. On the upside, China’s government understands the importance of agricultural risk protection for large-scale farm operations and insists on working on the issue. The Chinese government prioritizes agricultural risk management for rural households. Following the 2016 revision of the Regulations on Agricultural Insurance (RAI), the 2019 Guiding Opinions on Accelerating High-Quality Development of Agricultural Insurance set a target for agricultural insurance penetration (premiums/agricultural output value) to reach 2.5% by 2030 []. The central government provides financial subsidies covering 16 major crop categories, with a subsidy rate of 40–45% in central and western regions []. Additionally, innovative financial tools like “Insurance + Futures” are actively piloted, with 457 projects launched by 2022, extending to 31 provinces. The insurance coverage for the three major staple crops—rice, wheat, and corn—exceeds 70% []. Over time, as land acquisition progresses and with the continuous expansion of government support, rural households will enhance management strategies, implement early warning systems for farmland risks, and develop infrastructure like vegetable greenhouses to bolster resilience. This will undoubtedly amplify the positive effect of large-scale gains, weaken the negative effect of natural risks, and generally contribute to RHDR. We can therefore formulate hypothesis 4.

Hypothesis 4.

Land inflow increases rural household development resilience by realizing returns to scale.

3.3. Heterogeneity Analysis

The preceding section extensively explores the impact of land inflow on RHDR and delves into its underlying mechanisms. In this section, we will analyze the varied effects of land inflow on RHDR with diverse characteristics within the pairs.

3.3.1. Analysis of the Heterogeneous Effect of Land Inflow on the Developmental Resilience of Households That Are or Are Not Vulnerable

Although poverty eradication has eliminated absolute poverty, there are still vulnerable rural households, mainly manifested as formerly poverty-stricken households. China’s formerly poverty-stricken households, as a group of households that have already met the standard of “two no worries and three guarantees”, have met the needs of daily standard production and life, but their development ceiling is low due to problems such as lack of professional skills, knowledge and experience, lack of capital, and historical legacy. As a necessary path for rural households to modernize agriculture, whether land inflow can reach an appropriate scale is an important factor in determining whether the scale of planting can be brought into full play to realize additional benefits. Compared with non-vulnerable rural households, vulnerable rural households are at a disadvantage in terms of their own capital, so it is difficult to achieve the scale of land use efficiency. Moreover, historical factors such as weak education and restricted social networks hinder their ability for long-term developmental learning. This leaves them lagging behind in agricultural skills and management experience. Consequently, these limitations impede the potential positive impact of land inflow on RHDR. We can therefore formulate hypothesis 5.

Hypothesis 5.

Compared with vulnerable households, land inflow has a stronger uplift effect on the household development resilience of non-vulnerable households.

3.3.2. Analysis of the Heterogeneous Effects of Land Inflow on RHDR at Different Water Resource Levels

Water availability is crucial for agricultural production. In Southwest China, rural households’ access to timely and adequate water resources is a key indicator of the region’s social security level. Rural households with abundant water resources can more effectively manage land reclamation, irrigation, and crop planning, thereby maximizing the benefits of agricultural scale and enhancing household income. Moreover, increased levels of social security within a region can potentially empower rural households to better protect the health of their workforce and allocate resources towards land management, agricultural infrastructure, risk mitigation, and optimized planting strategies. This can maximize the benefits of land resources, boost agricultural income, improve resilience against external natural risks, and enhance rural households’ self-sufficiency. Because robust human capital and adequate financial resources further facilitate rural households in unlocking their potential for self-improvement, thereby fostering a “Matthew effect” where the stronger become even stronger. We can therefore formulate hypothesis 6.

Hypothesis 6.

Land inflow has a stronger uplift effect on rural household development resilience in areas where they are located that are rich in water resources.

3.3.3. Heterogeneous Effects of Land Inflow on RHDR with Different Levels of Participation Willingness in Collective Organizations

Collective organizations, including cooperatives, trade associations, mutual aid organizations and so on, are important forms of cooperative organizations to which rural households have access in their daily lives. Theoretically, when rural households engage in cooperatives, trade associations, and other village organizations, they are exposed to a more diverse and complex network of individuals and resources and broaden their social network, dismantling information barriers within their community []. In this way, more resources can be obtained and their organizational capabilities can be improved. Secondly, cooperatives and mutual aid organizations, as professional and service-oriented forms of collective organizations, will bring more learning opportunities for rural households. When farmers participate in agricultural inputs, transportation, processing, storage, and marketing of agricultural products, they gain access to technology and information pertinent to agricultural operations and acquire knowledge in agricultural production and management. This process facilitates the rapid accumulation of human capital and elevates their long-term development capabilities. Finally, active participation in village cooperative and mutual aid organizations exemplifies a broader sense of responsibility. Farmers who exhibit greater responsibility tend to manage their land inflow and subsequent agricultural activities—such as sowing, planting, transportation, processing, storage, and sales—more effectively. All of these enhance the positive impact of land inflow on RHDR. We can therefore formulate hypothesis 7.

Hypothesis 7.

Land inflow has a stronger uplift effect on the household development resilience of farmers who are actively involved in collective activities.

The research approaches are shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

The theoretical analysis diagram.

4. Materials and Methods

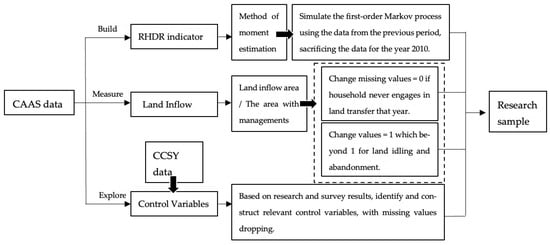

4.1. Data Sources

This study utilizes survey data from the Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences (CAAS), spanning the years 2011, 2012, 2013, 2015, 2018, and 2021. The sample includes 1517 households surveyed over three years, 882 over four years, and 351 over five years. Initial data from 2011 consisted mainly of cross-sectional data. As RHDR indicator construction necessitates omitting the initial period data, the core variable indicators cover 2012 to 2021. Due to a reduced sample size in 2013, the 2015 sample uses 2013 as the preceding period; if 2013 data are unavailable, 2012 serves as the alternative. Samples missing key variables were excluded, resulting in an unbalanced panel dataset with 3445 observations from 2012 to 2021. This dataset was then matched with county-level macroeconomic data from the China County Statistical Yearbook (CCSY), corresponding to the households’ locations, to form the final research sample. Data cleaning, index construction, modeling regression and other work were completed by Stata 18 statistical software.

4.2. Model Design

4.2.1. Benchmark Regression Model

According to the above hypotheses, this paper sets up the following two-way fixed effect model for subsequent empirical analysis:

where represents RHDR at moment t; represents household i’s intensity of land inflow at moment t; represents a set of control variables, including individual resident characteristic variables, relevant household characteristic variables, and regional characteristic variables; and and control for individual and time fixed effects of households, respectively; represents the randomized perturbation term; , and represent the constant term, the core explanatory variable coefficients, and the control variable coefficients, respectively.

4.2.2. Intermediate Test Model

In addition, in order to verify the path of action between land inflow and RHDR, the following model was used to analyze the mediation mechanism, drawing on existing studies:

where is the mechanism variable, and the rest of the variables have the same meaning as in Equation (1). In the case that coefficient and coefficient are significant, it indicates that variable has a mediating effect in it. When the coefficients and are significant, and the coefficient is not significant, it means that the mechanism variable plays a full mediating role; when the coefficients , , and are significant, it means that the mechanism variable plays a partial mediating role, and both of the above can explain to a certain extent that land inflow engaged in by the farm household has a role in their HDR through the mediating variable.

4.3. Variable Settings

4.3.1. Explained Variable

The explained variable is the Rural Household Development Resilience (RHDR). According to the concept of HDR proposed by Barrett and Constas (2014) based on poverty vulnerability [], RHDR reflects the ability of rural households to avoid falling back into poverty in the long run after facing a variety of risky shocks, and the measurement of RHDR is referenced to the moments estimation method proposed by Cisse and Barrett (2018) for estimating household developmental resilience [], adopting stochastic dynamic welfare changes to measure this ability: referring to the literature on poverty traps, it will be assumed that changes in rural household welfare follow a nonlinear dynamic path [], and the developmental resilience will be measured by utilizing the conditional moments function of welfare to predict the path of changes in household welfare and thus measure its developmental resilience. First, assume that the rural household welfare function obeys a first-order Markov process, and the model is set as follows:

In Equation (4), i stands for different households, t stands for time, and the subscript M stands for the expectation equation; is the household’s welfare, while is the household welfare at the moment of the previous period time node t − 1; based on this, it is necessary to additionally add household economic, social, and demographic characteristic variables () in the first-order Markov equation, and according to the existing literature, in order to make the estimation results of the household welfare function more accurate, one should try to choose the household characteristic variables that do not have large fluctuations in time. Therefore, drawing on the study of Vaitla et al. [], the household characteristic variables are selected as the sex of the head of the household, age, marital status, and household size, whether or not it has debt, and whether or not it has ever engaged in the activity of land transfer, etc.; j is the number of steps of the equation’s higher-order centroidal distance, and with reference to the poverty trap theory’s typical S-shaped dynamic characteristics, the order of the higher-order center distance of j is set to 3 [], as well as the coefficients to be estimated for the welfare equation, which is an unobservable random perturbation term in the model.

Secondly, after setting the household welfare function, the conditional expectation estimation of household welfare for household i at time t, , can be estimated using the zero-mean assumption of the random error term, i.e., E [] = 0:

Using V to represent the variance and referring to the second-order center distance estimation method of Just and Pope (1979) [] and Antle (1983) [], the squared term of the predicted value of the first-order center distance residuals is used to represent the second-order center distance, and the estimation method is specified as follows:

Also based on the assumption of a zero mean for the random error term, the conditional variance of household welfare for household i in period t can be estimated as:

Based on the above equation, the conditional variance of the family welfare function as well as the predicted value of the conditional expectation can be obtained, and further the family welfare of family i in period t can be estimated. Based on the research framework of Barrett and Constas (2014) [], it is assumed that the distribution of family welfare obeys the Poisson distribution [], and thus HDR can be defined as the probability that household i’s household welfare is higher than a specific amount in period t. The specific equation is set as follows:

In Equation (8), is the probability cumulative density function. With reference to the World Bank’s measurement index for the poverty standard and considering the specific way of data statistics, this paper selects the amount of per capita monthly consumption of the household as the measurement index of the household welfare function and takes the logarithmic form of the amount of per capita monthly consumption. In order to reduce the prediction bias, in the measurement of the household consumption, the purchase of large fixed assets such as agricultural machinery, agricultural vehicles and productive expenditures are removed, since the occurrence of such consumption or expenditure in the time dimension is contingent and requires additional consideration of depreciation. The threshold PL for the household welfare indicator, on the other hand, is based on the setting of the 2015 World Bank poverty line, i.e., the poverty line standard of USD 1.9 (2011 PPP) per capita daily consumption per household, which is converted into annually comparable data based on the annual average US dollar exchange rate and the residential price index (CPI). Finally, the specific measurement of household development resilience is as follows: firstly, Equations (4) to (7) are estimated using a generalized linear model (GLM) to obtain the conditional expectation and the conditional equation, and then the probability that the household’s welfare level is higher than the standard of the poverty line is calculated by using the conditional expectation and the conditional variance in Equation (8), which is ultimately used in this paper to measure the RHDR.

4.3.2. Explanatory Variable

The primary explanatory variable is the land inflow of the rural household, quantified by land inflow intensity. Under the Chinese government’s “separation of three rights” reform—distinguishing land ownership, contracting rights, and management rights—the right to flow into land and achieve large-scale operation falls within the scope of management right. Consequently, this is calculated as the ratio of the current year’s land inflow area to the area with management rights. The proportions of land outflow and inflow for the current year are determined, with missing values for non-participating samples set to 0. Based on survey data and analysis, some land inflow intensities exceed 1 due to factors like seasonal fallow, idle cultivation, and independent wasteland rental. These instances are adjusted to 1 to mitigate the impact of outliers on estimation results. In this way, it can not only smooth the influence of extreme values of samples on the estimation results, but also avoid the loss of samples.

The construction process of the research sample is shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

The construction of the research sample.

4.3.3. Control Variables

Drawing on existing studies [,,], control variables are selected at three levels: household head characteristics, household characteristics and regional characteristics; at the individual level, gender, age and marital status of the household head; at the household level, labor capital and social capital owned by the household, as well as the dependency ratio of the household and the degree of reliance on agricultural production; and at the regional level, the industrial structure and fiscal revenue and expenditure of the county to control for the impact of regional differences on the estimation results. The main variables and descriptive statistics of this paper are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Description of main variables and results of descriptive statistics.

5. Results

5.1. Benchmark Regression Analysis

Firstly, we verify the effect of land inflow of rural household on its HDR, and in order to ensure the accuracy of the regression results, we use stepwise regression method to conduct the baseline regression analysis. The regression results are shown in Table 2 and Table 3. Column (1) does not put any control variables and does not add any fixed effects. Column (2) and Column (3) add individual fixed effects and year fixed effects in turn, while Column (4), Column (5) and Column (6) add control variables at the individual level of the head of the household, at the level of the rural household, and at the level of the region where the farmer is located in turn, based on Column (3). The coefficients of the core explanatory RHDR on the variable land transfer are all significantly positive, indicating that land inflow by rural household enhances RHDR. These results support the conclusions of theoretical analysis. Through land inflow, farmers can effectively integrate existing land resources and expand social networks [,]. Non-agricultural information can also be collected effectively in consultation with traders in the non-agricultural sector. These respectively contribute to the improvement of their risk resistance, organizational capabilities and endogenous development capabilities. Hypothesis 1 is proved.

Table 2.

Benchmark regression results.

5.2. Robustness Test

5.2.1. Replace Explanatory Variable

In order to verify the robustness of the regression results, replace the construction mode of explained variable. Specifically, using whether or not the rural household was engaged in land inflow activities in the year as a new measure of land inflow. To be specific, if the rural household performed land inflow work in the year of the interview, a value of 1 is assigned, and vice versa, a value of 0 is assigned. The regression results after replacing the explanatory variable are shown in Table 3, Column (1). The coefficient of whether or not the rural household was engaged in land inflow is positive and significant, consistent with the findings of the previous benchmark regression. Hypothesis 1 is proven again.

Table 3.

Robustness test results.

Table 3.

Robustness test results.

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Replace Explanatory Variable | Replace Benefit Metrics | Replace Poverty Line Criteria (2300 CNY/year) | Replace Poverty Line Criteria (USD 2.15/day) | PSM Regression (1:1 Neighbor Caliper Matching) | PSM Regression (Kernel Matching) | |

| Land Inflows | 0.045 *** | 0.1 *** | 0.06 *** | 0.068 *** | 0.079 *** | 0.066 *** |

| (0.008) | (0.011) | (0.011) | (0.012) | (0.023) | (0.012) | |

| Head-Level Control Variables | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Household-Level Control Variables | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Area-Level Control Variables | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Individual | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Year | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Constant | 0.954 *** | 1.017 *** | 1.094 *** | 0.946 *** | 1.031 *** | 0.966 *** |

| (0.036) | (0.037) | (0.035) | (0.037) | (0.103) | (0.037) | |

| Observation | 3016 | 3016 | 3016 | 3016 | 941 | 3004 |

| R-squared | 0.302 | 0.334 | 0.699 | 0.323 | 0.36 | 0.301 |

Note: Standard errors are in parentheses; *** p < 0.01.

5.2.2. Replace Benefit Metrics

In this paper, when estimating the coefficients of characteristic variables by using Equation (4), large fixed asset expenditures like farming machinery and vehicles are excluded from welfare consumption. This adjustment aimed to enhance the accuracy of estimation results due to the sporadic nature of such expenditures over time and the necessity to account for depreciation. In a robustness analysis, these expenses were reintroduced and regressed against key explanatory variables. The results, presented in column (2) of Table 3, indicate a notably positive coefficient for the core explanatory variable, land inflow, consistent with prior regression outcomes, thereby reaffirming the testing of hypothesis 1.

5.2.3. Replace Poverty Line Criteria

In estimating RHDR using Equation (8), we used the poverty line standard of USD 1.9 (2011 PPP) per capita daily consumption per household. To verify the robustness of the results, the welfare threshold of USD 1.9 per person was updated to align with China’s 2011 poverty line of CNY 2300 per capita income (2011 PPP) and the World Bank’s 2022 poverty line of USD 2.15 per capita consumption per day (2017 PPP). These thresholds were adjusted using relevant consumer price indices and exchange rates to recalculate household development resilience. Table 3 presents the findings, with columns (3) and (4) showing the regression results for RHDR and land inflow of rural household under the CNY 2300 income standard and the USD 2.15 consumption standard, respectively. The core explanatory variables exhibit significantly positive coefficients at both thresholds, corroborating previous findings and affirming the robustness of the study’s conclusions.

5.2.4. PSM Regression

According to the descriptive statistical analysis of land inflow, it can be seen that the number of rural households involved in land inflow is less than half of the overall sample size. There is reason to suspect that rural households involved in land inflow may be in special livelihood characteristics. In other words, different characteristics of the rural households in the specific land transfer behavior decision-making may exhibit sample self-selective behavior, so that the estimation of the results is biased. In order to test the existence of this genetics problem, PSM regression is taken to solve the aforementioned problem. The PSM regression was designed to match rural households with land inflow to a control group with similar characteristics and then form a new study sample with the original experimental group. Finally, regression analysis was performed on the new research samples to test the robustness of the research conclusions. Utilizing methodologies from prior research, 1:1 neighbor caliper matching and kernel matching techniques are employed for regression matching in the following manner: the experimental group comprises samples subjected to land inflow, while the control group consists of samples not involved in land inflow. The matching process utilizes baseline regression control variables as covariates. Additionally, 1:1 neighbor caliper matching uses a caliper width of 0.05. The matching results are shown in Table 4 and Table 5. In 1:1 neighbor caliper matching and kernel matching, the covariates of the matched samples show standard deviations of less than 10%. All t-test results do not reject the null hypothesis of no systematic difference between the treatment groups, suggesting successful sample matching. The regression results after matching are shown in Table 3. Column (5) displays the results following 1:1 neighbor caliper matching, and Column (6) presents the results following kernel matching. The positive and significant coefficients of land inflow in both columns align with prior research, affirming the robustness of the study findings.

Table 4.

1:1 Neighbor caliper matching results.

Table 5.

Kernel matching result.

5.3. Endogeneity Test

Although the research hypotheses of this paper have been tested through a series of robustness tests to prove the positive correlation between land inflow and RHDR, the causal relationship still has endogeneity problems due to the existence of reverse causation, omitted variables, measurement bias, etc. Therefore, to address the above reasons, this paper adopts a two-stage instrumental variables regression for reverse causation and Oster bounds test for omitted variables, respectively, to test for the possibility of endogeneity problems in the regression results.

5.3.1. Two-Stage Instrumental Variables Regression

To address the reverse causality of rural households’ participation in land transfer and their HDR, drawing on the ideas of Xiao and Luo (2023) and Zhou (2024), etc., two-stage instrumental variable regression was used for testing. The ratio of families participating in land transfer in the villages where the local families are located is selected as an instrumental variable [,]. On the one hand, farm households’ economic decisions are often shaped by social factors, particularly neighborhood dynamics. The concept of “peer effect” suggests that a higher presence of land transfer activities within a village can lead to increased market activity. This can result in households influencing each other’s decisions regarding land transfer, ultimately increasing the likelihood of participation in such transactions. On the other hand, the overall land transfer rate within a village does not directly impact the individual resilience of farmers. The unique characteristics of individual farmers do not directly influence the collective land transfer behavior of their village. Therefore, the instrumental variable meets the exogeneity criteria by being uncorrelated with the model’s error term. The regression results are shown in columns (1) and (2) of Table 6. The instrumental variable two-stage regression results exhibit positive and statistically significant findings, consistent with the baseline regression results. Moreover, the Cragg–Donald Wald F-value and Kleibergen–Paap rk Wald F-value stand at 9.523 and 9.245, respectively, surpassing the critical value of the Stock–Yogo test at the 15% significance level. The instrumental variable weak identification test was passed.

Table 6.

Two-stage regression result.

5.3.2. Oster Bounds Test

When selecting control variables for the causal pathway, omitted variables are unavoidable. These omissions can lead to endogeneity issues, hindering the model’s ability to consistently estimate the coefficients of key explanatory variables related to land inflow. To enhance the robustness of our study’s findings, we conduct the Oster bounds test on the estimation model to assess potential bias from omitted variables. The test results are shown in Table 7, and from the results, the model passes the test under both tests, indicating that the endogeneity problem due to omitted variables has a negligible effect on the consistent estimation of the model, and that the estimated coefficients of land inflow are very robust, consistent with the previous conclusions.

Table 7.

Oster bounds test result.

6. Discussion

6.1. Mechanism Analysis

Firstly, in hypothesis 2, the logarithm of the top three household liabilities in the survey year serves as a measure of household debt burden. This variable is then included as the mediating variable in the mediation test model. The regression outcomes are presented in columns (1) and (2) of Table 8, and indicator M1 is the logarithmic form of the top three household liabilities. The coefficient associated with the primary explanatory variable of land inflow on debt burden in Column 1 exhibits a significant positive relationship, indicating that the inflow of land initially increases the financial burden on families because families have to pay rent for the inflow of land. Especially for small and medium-sized rural households, who do not have strong social networks and clan relationships, negotiation is more difficult []. In addition, there are seedlings, fertilizers and agricultural equipment needed for large-scale operation. This is also consistent with the previous analysis. According to Barrett and Constas et al.’s study of the HDR resistance dimension [,], it can be argued that land transfer will adversely affect HDR in the early stage by increasing the financial burden of households and thus weakening resistance. However, the coefficients for debt burden and land inflow in Column 2 exhibit significant positive associations with RHDR. This suggests that while land inflow may initially diminish the household’s risk-resistant ability, the ensuing development pressure fosters the household’s intrinsic motivation for development, ultimately bolstering RHDR over time, because the household’s endogenous development ability is also an important component of RHDR [,]. Compared to resistance, it is also a core indicator of long-term ability to prevent poverty []. In particular, the Chinese government has been pushing forward the mortgage reform of land management rights and its efforts in continuously cultivating high-quality farmers. The resulting welfare effect will further offset cost pressures. Therefore, it is probable that the enduring improvement in household development capacity resulting from cost pressures outweighs the risk-resistant ability decline. This validates hypothesis 2.

Table 8.

Test results of mediation mechanism.

Secondly, utilizing the ratio of labor force working outside the rural household to those remaining at home in the surveyed year as a dynamic indicator of measuring labor force outside. The regression results in columns (3) and (4) of Table 8, and the index M2 is calculated from Labor Force away/Labor Force at Home. They reveal that the coefficients of land inflow on the outgoing labor force ratio exhibit a statistically significant negative relationship. In the subsequent stage of the mediation regression model, both the regression of RHDR and the outgoing labor force ratio demonstrate negative significance. Notably, the regression coefficients associated with land inflow remain consistently positive and statistically significant throughout the analysis. It is shown that land inflow promotes the return of labor and thus the RHDR and is a partially mediated effect. As highlighted earlier, rural households adjust their labor allocation by reallocating resources from external employment to accommodate the demands of large-scale land influxes []. The external workforce possesses superior physical fitness, specialized expertise, and extensive social connections, offering advantages in social engagement, managerial proficiency, and knowledge acquisition. Their reintegration can notably bolster the organizational and endogenous developmental capabilities of rural households. This helps to improve RHDR, and hypothesis 3 is proved.

Finally, the per capita income from grain cultivation during the surveyed years serves as an indicator of whether agricultural production has achieved scale effects following land inflow. Grain cultivation is the primary livelihood for local farmers who have experienced land inflow, making it a reliable measure of land income levels. Additionally, the return of laborers to their hometowns due to land inflow has increased family labor inputs, with labor costs being a significant component of agricultural production. Thus, per capita grain income effectively measures whether land inflow has generated returns to scale. According to the regression results in Table 8, columns (5) and (6), indicator M3 is calculated from Per Capita Farm Income/100,000, and the coefficient of land inflow intensity on household per capita grain income is significantly positive. Furthermore, the regression coefficients for second-stage RHDR on both per capita grain income and land inflow are also significantly positive. The results of this part of mediating effect provide strong support for the previous analysis. On the one hand, large-scale inflow of land is easier to achieve scale efficiency and increase grain income, which is conducive to improving rural households’ risk resistance [,]. On the other hand, although the expansion of land management scale will expand the exposure of natural risks, this negative effect is limited by financial assistance means such as the Chinese government financial subsidies, high-quality agricultural insurance and innovative financial instruments represented by “insurance + futures” [,]. This mediation path is generally conducive to enhancing RHDR, thereby confirming hypothesis 4.

6.2. Heterogeneity Test

For hypothesis 5, hypothesis 6 and hypothesis 7, the hypotheses are tested using split-sample regression. First, whether the rural household is a poverty-removing household or a former file-setting card poor household is used as the main criterion of whether it is a poverty-removing household or not. The sub-sample regression results in Table 9 reveal distinct outcomes for non-formerly poor households and formerly poor households in columns (1) and (2), respectively. The coefficient in column (1) is statistically insignificant, while the coefficient in column (2) demonstrates a significant positive relationship. This proves that the effect of the intensity of land inflow on the RHDR exists in two groups with heterogeneity. It has a certain threshold effect on the relatively vulnerable rural households, such as poor households with filing cards. This is consistent with the theoretical analysis above, because of historical problems or development orientation, vulnerable rural households are at a disadvantage in their own capital endowment, self-learning ability and risk prevention strategies. This limits both the area of land they flow into and the effectiveness of land management, as well as the upper limit of their self-learning. These factors make the lifting effect of land inflow on their HDR less likely. This also shows that, compared with non-vulnerable rural households, they need exogenous support to enable them to successfully survive the “pain period” of land inflow [], so as to achieve economies of scale and self-development. Hypothesis 5 is proved.

Table 9.

Heterogeneity test results.

Secondly, using “whether rural households can normally drink water throughout the year” as the classification criterion for the level of water resources availability of rural households. The regression results are shown in columns (3) and (4) of Table 9. The coefficients of the core explanatory variables in columns (3) and (4) are all positive and significant, but the absolute value of the coefficient in column (3) is larger than that in column (4), which indicates that there is a heterogeneous effect of land inflow on RHDR in the two groups of samples. This also provides supporting evidence for the important role of water resources in land circulation. On the one hand, water resources are an important element of agricultural development, and households in areas with perfect water conservancy infrastructure can better carry out scale management of land and realize scale income. On the other hand, water resources are also related to the health level of the household labor force. A healthy labor force means that farmers have better learning ability and agricultural management level, and thus can be at an advantage in the future development of land management. Therefore, rural households in areas rich in water resources are more likely to play a role in promoting RHDR through land inflow. Hypothesis 6 is proved.

Finally, “Is the female head of the household a member of a cooperative/business association/mutual aid organization” is used as a categorical variable for the participation of rural households in different collective organizations. Because the general situation in rural areas is that men in the household are more engaged in production and management work and have less time to participate in collective organizations and activities in the village. So compared with men, women’s participation can more accurately reflect their participation in collective organizations. And participation can more accurately reflect the strength of the willingness of rural households to participate in village collective organizations. The sub-sample regression results are presented in Table 10, specifically in columns (5) and (6), illustrating the varied impacts of land inflow on the RHDR. Given the limitation of utilizing solely cross-sectional data for the year 2021, this regression does not employ a two-way fixed effects model. Robust standard errors are employed, clustered at the household level. The coefficients of the primary explanatory variables in columns (5) and (6) demonstrate positive and statistically significant associations. But the absolute value of the former is greater than the latter, indicating a heterogeneous impact of land inflow on RHDR across the two samples. Specifically, rural households actively engaged in collective organizational activities exhibit a more pronounced positive effect. This is consistent with the theoretical analysis of the previous question, because households with strong collective consciousness have broader social networks and richer learning opportunities. Land inflows can be better utilized to reduce poverty and support their own long-term development []. They are also more responsible and tend to be “intensive” in land management. This helps them improve their HDR. This finding supports hypothesis 7.

Table 10.

Regression Results Comparing Land Transfer Methods.

7. Further Analysis: Heterogeneous Effects of Different Land Transfer Methods on RHDR

The literature remains divided on the poverty reduction impacts of the heterogeneity in land transfer modes, specifically land inflows and outflows. And few studies have rigorously compared these modes within the framework of farm household endogenous development (HDE). This section delves into this issue. Unlike the immediate goals of income enhancement and poverty alleviation, the essence of farm household HDE is to sustain welfare above the poverty threshold over the long term. Therefore, comparative analyses of land transfer modes should not only assess short-term welfare changes but also examine their effects on risk tolerance, self-organization, and the endogenous development dynamics of households.

7.1. Different Ways of Working and Operating Under Different Modes of Land Transfer

Secondly, the development of new agricultural management entities is crucial for modernizing agriculture and is a key focus of current agricultural policy. Land inflow is essential for forming these new management bodies, enabling farmers to achieve appropriate scale and systematic operations that align with contemporary development trends. This approach is supported by policies such as agricultural land subsidies, skills training, vocational education, and infrastructure development for agricultural risk management. Non-farm employment among farmers primarily results from land outflow [,,]. Since the reform and opening, the household contract responsibility system and advancements in land rights have led many farmers to rent their land and seek urban employment or engage in non-farm entrepreneurship. However, unprecedented changes over the past century have seen the demographic dividend diminish as population and labor force numbers peak and decline. Economic growth has decelerated, and global supply chain vulnerabilities, exacerbated by international conflicts and industrial restructuring, have intensified structural employment challenges [,,].

Amid declining returns in the non-farm job sector, an increasing number of workers are opting for new employment forms characterized by low skill requirements, flexible hours, and primarily manual labor. Notably, many of these workers are highly educated, reflecting a trend of educational attainment exceeding job requirements. Farmers, due to limited education and insufficient experience and skills, face heightened market risks in non-agricultural employment []. Compared to recent graduates, farmers lack advantages in physical capability, age, and professional skills, exacerbating their weak competitiveness during job market adjustments [,]. Consequently, they encounter reduced job market welfare and heightened unemployment risks. At this juncture, the benefits of non-farm employment following land outflow are negated by increased employment risks compared to land inflow, diminishing the risk tolerance of households experiencing land outflow.

7.2. Analysis of the Role of Heterogeneous RHDR with Different Earnings Patterns

Lastly, compared to the autonomous management and self-financing of farmers’ households following land inflow, the stable and reliable rental income resulting from land inflow is more likely to reinforce farmers’ ideological reliance on “waiting, wanting, and relying”. Through land inflow, rural households can expand their production scale and management, becoming independent in procuring crop raw materials, conducting agricultural production, managing sales, and handling product transportation. In contrast to land outflow, land inflow entails increased production scale and management, necessitating the replacement of equipment, procurement of agricultural raw materials, recruitment of human capital, and other initial investments in time, capital, and management costs, all while facing the pressure of rental obligations. Farmers are compelled to enhance their professional knowledge and management skills due to rising rent and financing costs, aiming to generate revenue and achieve profitability promptly. This external pressure acts as a catalyst for boosting their internal development momentum. Engaging in various business, management, and sales activities leads to the accumulation of information and experience, broadening social networks, and enhancing self-competence. Consequently, rural households are not only driven to enhance their self-organizational capacity but also experience a pull effect towards self-improvement. While households acquiring land may initially face a decline in welfare, the long-term outcome is a significant enhancement in their self-development capabilities and internal drive for growth. This, in turn, contributes to strengthening the resilience of their family development. Conversely, the steady income from leasing out land, coupled with the absence of pressure to enhance self-organizational skills and internal drive, hinders the long-term improvement of RHDR.

7.3. Other Supporting Evidence

A comprehensive analysis of rural households’ welfare creation and risk exposure under various land transfer methods, alongside trends in the land transfer and labor markets, reveals heterogeneous effects on RHDR. The welfare gains and risk exposure associated with land inflow surpass those of land outflow, significantly enhancing RHDR. Next, additional evidence will be presented to support land inflow and land outflow in the benchmark regression, PSM regression, and replacement of explanatory variables regression. In the benchmark regression, the explanatory variables include the intensity of land outflow and land inflow, calculated as follows: the intensity of land outflow is determined by the ratio of the area of land outflow by rural households in the current year to the total contracted land area, while land inflow is measured by the ratio of the area of land inflow in the current year to the area of land under use rights. To calculate the land outflow and inflow ratio of rural households in the current year, we first determine the ratio of the land inflow area to the land area with use rights in the current year. Any missing values for samples not involved in land transfer are replaced with 0, and outliers are smoothed out. This approach aligns with the methodology outlined in the preceding section. The analysis distinguishes between individuals engaged in land inflow or outflow activities, assigning a value of 1 to those involved and a value of 0 to those not engaged in such activities. The PSM regressions are performed using 1:1 neighbor caliper matching and kernel matching, respectively. The regression results are shown in Table 10; columns (1) and (2) are the baseline regression results, columns (3) and (4) are the 1:1 proximity caliper matching results, columns (5) and (6) are the kernel matching results, and columns (7) and (8) are the regression results after changing the explanatory variables. The regression results show that the coefficients of land inflow are all positively significant, the coefficients of land outflow are either positively significant or insignificant, and the positively significant coefficients are smaller than those of land inflow. This indicates that land inflow has a better effect on RHDR than land outflow.

8. Conclusions and Recommendations

8.1. Conclusions

Utilizing unbalanced panel data from the 2012–2021 CAAS research, this study empirically investigates the relationship between land inflow and RHDR. The findings indicate that land inflow enhances RHDR, a conclusion supported by various robustness and endogeneity tests, which include replacing explanatory variables, replacing benefit metrics, replacing poverty line criteria, PSM regression, two-stage instrumental variables regression, and the Oster bounds test. At the same time, we also deeply study the mechanism of land inflow affecting RHDR. Through theoretical analysis and empirical analysis of the mediation benefits test model, we find that while land inflow initially diminishes developmental resilience due to higher input costs, it ultimately boosts resilience through endogenous incentives, labor return, and the scale effect of agricultural production. The study also examines the varied impacts of land inflow on RHDR. Sub-sample regression results indicate that land inflow is particularly beneficial for non-profile households, those with abundant water resources, and those more inclined to engage in collective activities. Further analysis investigates the differential effects of various land transfer methods on RHDR, and land inflow enhances RHDR more significantly than land outflow. This conclusion has also undergone robustness tests such as changing explanatory variable measurement methods and PSM regression.

8.2. Policy Recommendations

Based on the above findings, this paper makes the following policy recommendations:

First, the significant role of land transfer in enhancing RHDR should be emphasized, and the role of land transfer in increasing income and reducing poverty should be better leveraged. Through theoretical and a series of empirical studies, this research has confirmed the conclusion that land inflow can significantly promote Rural Household Development Rate (RHDR). Meanwhile, in the further discussion section, evidence has also been provided indirectly indicating that land outflow can also promote RHDR, with only differences in the magnitude of the effects between the two. Therefore, the government should consciously improve the relevant systems to promote land transfer, clarify the relevant land rights, and lower the threshold for land transfer. For example, China has implemented the reform of “separating the three rights of rural land” to clarify relevant land rights and carried out the “pilot project of mortgaging the right to operate rural land” to continuously activate the value of land, truly applying land rights to poverty alleviation and prosperity. In addition, attention should also be paid to the fact that rural households are in a vulnerable position during the process of activating land factors and relaxing land property rights. The division of their land-related rights should be more explicit and specific to prevent them from being damaged by rights violations.