Abstract

Urban regeneration is often presented by those responsible as an unquestionable success story. Barcelona’s transformation from the mid-1980s, with its great Olympic momentum and successive attempts to maintain its international status, is perhaps one of the most widely publicized and celebrated. Among the operations, the waterfront stands out as one of the most significant regeneration efforts due to their territorial scope, social implications, and economic impact. In this text, we want to challenge this official success story with other untold stories: the stories of the preexisting spaces that have been erased, the people who have been displaced, and the industrial heritage that has been destroyed. There are hardly any memories left, and the regeneration projects seem to be built on a previous emptiness. The discourses of success are often accompanied by maps that conceal the process of change and, at the same time, present the regeneration projects as disconnected from other spaces and processes. Maps appear as artifacts with great limitations in their capacity to represent complex and time-delayed processes and, at the same time, have enough power to legitimize urban regeneration as beneficial to all. However, maps can also be powerful tools for changing the way regeneration processes are told and who tells them, thus revealing what has been hidden.

1. Introduction

How many maps, in the descriptive or geographical sense, might be needed to deal exhaustively with a given space, to code and decode all its meanings and contents? [1] (p. 85)[1]

Urban regeneration is often presented by those responsible as an unquestionable success. Barcelona’s transformation from the mid-1980s, with its great Olympic momentum and successive attempts to maintain its international status, is perhaps one of the most widely publicized and celebrated. Among the operations, the waterfront transformation stands out as one of the most significant regeneration efforts due to its territorial scope, social implications, and economic impact.

In this text, we want to confront this official success story with other untold stories: the stories of the preexisting spaces that have been erased, of the people who have been displaced, and the industrial heritage that has been destroyed. There are hardly any memories left, and the regeneration projects seem to be built on a previous emptiness. The discourses of success are often accompanied by maps that conceal the process of change and, at the same time, present the regeneration projects as disconnected from other spaces and processes. For instance, the maps do not show where the displaced people went, where the investments came from, where the profits are directed, and who are the new inhabitants attracted by the projects.

Maps appear as artifacts with great limitations in their capacity to represent complex and time-delayed processes and, at the same time, with enough power to legitimize urban regeneration as beneficial to all. However, maps can also be powerful tools for changing the way regeneration processes are told and who tells them, revealing what has been hidden.

The methodology proposed in this article is grounded in Doreen Massey’s relational conceptualization of space, which understands space as dynamic and constituted through a multiplicity of trajectories, stories, and interconnections across different scales. Building on this framework, we critically examine the limitations of traditional cartographic language in capturing such complexity, particularly in the context of Barcelona’s waterfront redevelopment. To do this, we must consider those elements that official history has not considered in order to propose a more complex reading of that process, which has obvious consequences for the formation of the current space.

In this way, maps can also render visible that which has been displaced, destroyed, or forgotten, offering alternative readings of urban transformation processes. Thus, maps can also serve as counter-hegemonic tools against top-down redevelopment initiatives, capable of reconfiguring how regeneration processes are visualized and narrated. Our proposal is to develop a cartographic framework that makes visible the causes and consequences of urban change. We focus on the hegemonic discourse surrounding the transformation of Barcelona’s waterfront, contrasting it with the experiences of those who were displaced, the destruction of cultural heritage, and the erasure of collective memory. Maps, in this view, are not merely technical tools but powerful instruments capable of revealing relational geographies, exposing spatial injustices, and including the voices of those who have inhabited, contested, and been affected by processes of spatial restructuring.

To develop these ideas, this article is structured in three parts. First, we discuss how the transformation of Barcelona since the mid-1980s has been presented as an exemplary case of urban strategy that many cities in Europe and America have taken as a reference. We focus on waterfront redevelopment as one of the privileged strategies of urban “regeneration” processes. Second, we unveil how that official story of success overlooked what previously existed underneath, as if the new redevelopments had been built on nothing. There were other stories that were not told, such as those of the people who used to live there before, the resistances that existed, the collective memories that have struggled not to be erased. In Section 3, we turn to the power of maps. They have been used most of the time to justify the erasure of the past and omit spatial relations beyond the city, but here, we aim to redefine maps as powerful instruments for uncovering and sharing those untold stories. For this, we have designed an overlapping framework of layers that reveals the complexity and diversity of space that the hegemonic discourse so easily covers.

2. Barcelona’s Stories of Success

2.1. Urban Regeneration Strategies

At the beginning of the 1970s, in many European metropolitan areas, unexpected trends began to emerge: industries were leaving central spaces towards metropolitan rings, new tertiary activities were concentrating in central areas and the population tended to move to outer suburban areas. These new trends were immediately declared as a crisis of inner cities [2], marked by several negative processes: a halt in demographic growth, economic stagnation, and the abandonment or visible degradation of significant urban areas.

The crisis of the industrial city led to significant changes in urban form and functions and, consequently, in the way cities were analyzed and managed. The new emphasis on city competitiveness, the ways to achieve it, the renewed role of private agents, and the economic strategies to promote growth were signs that substantial changes were occurring in planning and, more generally, in urban policy: from regulation to growth promotion, from a managerial to an entrepreneurial approach [3]. But despite the apparent changes motivated by those new circumstances, it has been remarked that the conception of the city and the objectives pursued by those who lead it would have remained nevertheless immutable: this was about “keeping the machinery well-oiled”, in Peter Hall’s words [4], or about defining new horizons while maintaining the “same ideology”, in Harvey’s terms [5].

It was David Harvey who summarized the diversity of strategies adopted by cities in his 1989 seminal paper [3]. Among them, the more intense exploitation of the particular advantages derived from their location or existing resources, or the creation of the necessary physical or social infrastructures. This required significant expenditures in the form of applying new technologies, finding ways to attract business initiatives, investments in the training of qualified labor force, improvement of communication infrastructures, etc. In other words, all those attributes that could be distinctive of a competitive city and thus shape its positioning in the market. At the same time, the search for a distinct position in the spatial division of consumption emphasized the enhancement of the quality of life to strengthen the city’s attractiveness through the improvement of the physical environment, cultural innovation and the construction of new attractions or leisure spaces. The production of the city’s image was here a key element. As Harvey put it, “Above all, the city must appear as an innovative, interesting, creative, and safe place to live or visit, to be and consume” [3]. All combined, it gave rise to the frantic interest in carrying out flagship projects that served both to promote and to communicate the renovations carried out. Many times, these flagship projects have been associated with the organization of mega-events, which have been a necessary strategy to justify massive public investments, as it was the Barcelona case.

2.2. Barcelona’s Model of Olympic Transformation

Barcelona’s deindustrialization in the 1970s stemmed from a combination of the economic crisis and the relocation of industries to the metropolitan outskirts. Meanwhile, new tertiary activities gradually replaced the displaced industries in the city’s central areas [6]. However, the 1970s represented more than just an economic turning point; the city also grappled with demographic decline, rising unemployment, and the political challenges of the democratic transition.

The collapse of the “unlimited growth” hypothesis—central to the “desarrollista” urban policies—along with the recognition that industrialization was no longer the engine of urban development, prompted a swift redefinition of urban policy goals. By the late 1980s, Barcelona embraced a “new” urban policy. This approach expanded traditional municipal roles—such as public works, urban planning, and service provision—to include strategies addressing the impacts of the economic crisis while fostering growth and finding innovative ways to “reinvent the city”. Among these strategies were the organization of the 1992 Olympic Games, the implementation of a “new urbanism” focusing on design-centric projects, and explicit efforts to enhance and disseminate the city’s image.

Hosting major urban events is a frequently used revitalization strategy, as it concentrates significant resources from various sources within a relatively short period. In Barcelona, with the historical precedents of 1888 and 1929—used to naturalize a similar new event—the 1992 Olympic Games were presented as a pretext, an excuse, a platform, and a unique opportunity. City leaders often stated that if the 1992 Games had not existed, they would have had to invent them [7]. In this case, the Olympics served as a strategy to address the lack of incentives from both private initiatives and public facilities. They provided a means to unlock investments in critical infrastructure deficits, including arterial road networks, sections of the ring roads, port expansion, airport terminal restructuring, and telecommunications infrastructure. Additionally, the Olympics became a powerful tool to boost Barcelona’s international visibility, as well as a catalyst for strengthening social cohesion and the sense of belonging to the city.

Alongside this, the “new urbanism” aimed to reinforce the city’s attractiveness and improve its international positioning. The new public spaces that were inaugurated during the 1980s were internationally acclaimed pieces of design. In addition to small-scale projects, there were “large projects”, such as Battery Park in New York, the Docklands in London, and, in Barcelona, the Olympic Village and other Olympic areas. New urbanism played a pivotal role in changing the city’s image through the creation of new spaces or the renovation of old ones, effectively projecting a new and attractive vision of the city while erasing negative associations with a declining industrial city [8].

2.3. Barcelona’s Olympic Waterfront

As mentioned above, in the processes of urban restructuring, the production of the city’s image becomes a central element in revitalization strategies; therefore, it is easy to find a large number of images related to revitalization as a global process—images intended to show, above all other considerations, a ‘revitalized city’. As the Italian geographer Giuseppe Dematteis pointed out, images of the physical transformation of the city were especially relevant in this context: “the most effective urban images—internal and external—are those that take the form—designed or discursive—of a project for the physical transformation of the city” [9].

New built spaces constitute a primary communication element, especially relevant in urban regeneration strategies. The American geographer Briavel Holcomb noted the notable tendency towards homogeneity in the new constructed spaces in revitalized cities (‘the standard revitalization apparatus’). The ‘trophy collection’ to which all cities aspire, according to the perfectly assumed American standard in Europe, would consist of elements such as a downtown shopping center, new office towers, a restored historic district, a waterfront park, etc., to which ideally some distinctive element should be added, relatively easy to achieve in quantitative terms: the largest aquarium in the world, the largest shopping center in the world [10].

Waterfront redevelopment has emerged as a key strategy, particularly through brownfield land requalification [11], with the Olympics frequently serving as a prime opportunity to implement it. The intersection of these two phenomena—Olympic urbanism and waterfront regeneration—has been termed the “Olympic Waterfront” by Pinto and Dos Santos [12].

Among the nine cases of Olympic waterfronts analyzed by these authors, Barcelona stands out as both a pioneer and one of the most successful examples. This was been a huge, complex, and long-term project. Like many other historical cities, Barcelona had a complex relationship with the sea. Throughout history, being located by the sea was both beneficial and threatening, which initially left an empty strip along the coastline. Over time, this void was usefully repurposed for essential transport routes and heavy infrastructure [13]. Thus, from the mid-19th century onward, the railway connected Barcelona to other coastal cities but inevitably created a barrier that physically separated the industrial urban fabric from the sea. On the other hand, along all Barcelona coastline (from Barceloneta to what is now the Forum), shantytowns began appearing on the beaches at the end of the 19th century, with the arrival of people to work for the 1888 Exposition. This included the settlements of Somorrostro and Pekín, located on public land and enclosed by industries, the railway, and the sea, where 1200 shanties were recorded in 1914. During the 1920s, a string of shantytown clusters began to consolidate all along the coastline (Somorrostro, Bogatell, Mar Bella, Pekín, as well as Trascementiri in Poblenou and Camp de la Bota), reaching their maximum expansion by the mid-1950s. All these settlements were not fully eradicated until the Olympic development works were carried out.

Gradually, all this “waste of land” came to be perceived as an economic loss. In pre-Olympic Barcelona, one of the most commonly repeated slogans associated with the city’s major transformation emphasized the importance of “opening the city to the sea”, underscoring the urgency of reclaiming the waterfront for a city that had historically “turned its back on the sea”. Catalan architect Joan Busquets captured this sentiment eloquently in his work on the urban evolution of the city: “The reworking of Barcelona’s urban form depended to a large extent on the forging of an open, well-defined relation with the sea. The pride of a city that had always aspired to be the capital of the north-western Mediterranean came into its own” [14].

This ambitious, decades-long undertaking began with the renovation of ‘Port Vell’ (Inner Harbor) and the Moll de la Fusta project, which served as the commercial centerpiece of the transformation. These initiatives replaced port and storage functions with leisure, hotel, and commercial spaces, mirroring similar redevelopments of former port areas, such as the iconic case of Baltimore. Together, they marked the initial phase of a more than two-decade-long process to completely revitalize the waterfront.

This transformation demanded substantial infrastructural investments, including burying the railway line that once ran parallel to the coast, treating wastewater that had previously been discharged directly into the sea, creating and stabilizing new beaches, and enhancing road and pedestrian access.

The Olympic Games further accelerated progress, resulting in the creation of a new neighborhood in Poblenou (Vila Olímpica), the construction of a marina, and the addition of prominent new landmarks to Barcelona’s skyline, including the two Olympic towers. Notable developments included constructing a promenade and extending Diagonal Avenue to the sea, cutting through the industrial fabric of Poblenou, which was already undergoing transformation as part of the 22@ project.

Later, a new mega-event in 2004, the Forum of Cultures, culminated this transformation by extending redevelopment along the coast to the edge of the Besòs River.

Today, from Barceloneta to the Forum, a nearly 5 km-long promenade enables visitors to walk along the coastline directly beside the beach. This transformation has been widely recognized as an economic success. The former industrial and informal settlement area, once divided by the railway, has evolved into a vibrant and dynamic hub, integrating residential spaces with economic, leisure, and tourism activities [12].

3. Other Stories to Be Told: Displaced, Destroyed, and Erased

Another way to tell the same story is to highlight that this now highly valuable and attractive central land was once an extensive area of industries, workers’ housing, and shantytowns. The “opening of the city to the sea” thus involved a deliberate and gradual clearing of the coastline.

What was presented as a major urban improvement project intended for the benefit of its residents and attract new economic activities, also concealed an underlying ambition to increase the value of industrial and marginal land to the benefit of investors. Since 1965, plans had existed to repurpose the area following the gradual abandonment of factories (Motor Ibérica and Foret had already relocated to the Zona Franca, and La Maquinista was inactive) and to revalorize the land closest to the sea. However, these plans (Plan de la Ribera) were not implemented at the time due to the strong opposition they faced [15].

But this latent ambition of capital eventually materialized through the later redevelopment of the waterfront, particularly via the plan for the construction of the Olympic Village (1986). The industrial lands of Poblenou were designated for the construction of the Vila Olímpica, which housed athletes during the 1992 Olympic Games. This residential complex was designed to later become homes for middle- and upper-class residents. On the eve of the Games, this was a very rapid redevelopment, achieved in few years and managed by a public–private partnership. Today, while it is known that the area was once an industrial hub, it is less well-known that it was inhabited by a working-class population [16].

These fast changes to the urban landscape were undertaken with little regard for preserving the industrial past, current activities, and residents, nor was there any effort to acknowledge or safeguard the memory of the thousands of people who had lived for years in the space between the railway tracks and the sea. As is often the case, this transformation was achieved through a systematic erasure—both physical and symbolic—of what previously existed, reinforcing the notion that there was nothing worth valuing, conserving, or even remembering. This greatly diminished criticisms and resistances, which only emerged and became visible after the losses had mostly occurred, by which point it was, in many ways, too late.

3.1. Displaced by Capital’s Seafront Conquest

With the underground railway came social emptying on both sides of the tracks: the shacks that still remained on the beach and the workers’ housing and small workshops in Poblenou.

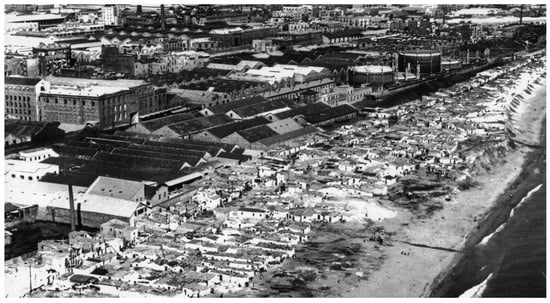

By the mid-20th century, there were around 2400 registered shacks along Barcelona’s coastline, housing some 15,000 people (Figure 1). These shacks embodied the collective imagination of unknown, marginal, and dangerous spaces. From the 1950s onwards, plans were set in motion to eradicate informal housing [17]. A significant number of shantytown settlements were thus gradually eradicated, and their residents were relocated to distant housing estates, most of which were unfinished and lacked necessary services. Between 1960 and 1975, several social housing developments were built on the outskirts of the city, where many former shantytown residents were rehoused.

Figure 1.

The shacks of Somorrostro by the seaside (Source: Icaria. URL https://projecteicaria.blogspot.com/, accessed on 18 April 2025).

However, over time, with the uncontrollable rise in housing prices in the metropolitan center, some of these housing estates began to move toward becoming central areas themselves, and their populations faced the threat of displacement due to the advancing frontier of gentrification. Nonetheless, their strong stigma (stemming from their role as spaces hosting unwanted activities and individuals from the center) might serve as a form of protection, leaving them in a kind of “permanent temporariness” [18].

Today, the site of the Somorrostro shacks hosts new marina facilities, and on the other side of it, Nueva Icaria beach serves as a thoroughfare for tourists heading to restaurants, nightclubs, and bars in the Olympic Port.

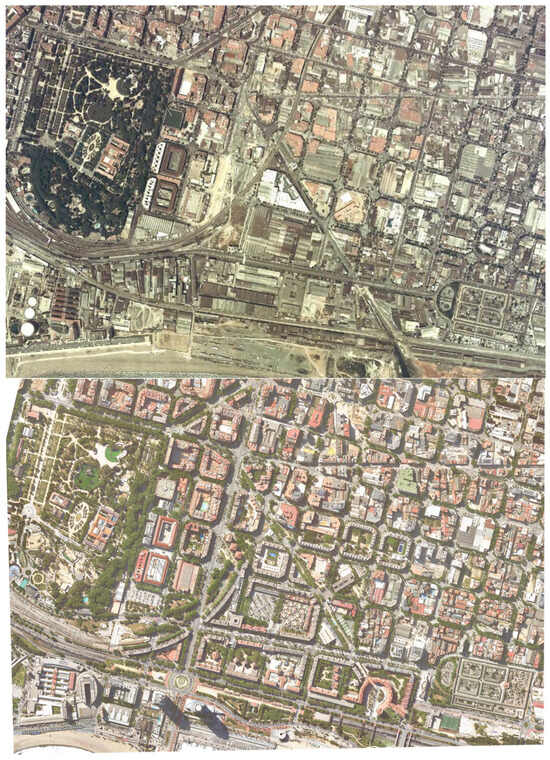

Analyzing the erased industrial past of the area (Figure 2), the architect and anthropologist Gabriela Navas undertook the exercise of “identifying what architecture allows to be hidden”, seeking traces of the past within the present-day construction [15]. Among the preserved buildings, only one chimney stands out—a chimney isolated from a late 19th-century industrial complex (Can Folch) on Icaria Avenue, restored with a plaque that highlights it as a “testimony to the industrial past of the neighborhood”. Other preserved sites include the women’s prison, the old lazaretto (Quarantine House), now the Hospital del Mar, the former barracks repurposed as part of the UPF Ciutadella campus, and the water reservoir, now a library of the same university. The shopping center called “el centre de la Vil.la” now stands on the former site of a water treatment plant.

Figure 2.

Above, aerial view of the Icaria neighborhood (1987) before its disappearance [19]. Below, current view from Google, 2024.

In all senses, the area was always a “backyard” territory of Barcelona, which, with the Olympic Games, shed its state of unsanitariness and marginality. The Olympic project boosted land profitability and contributed to channeling the revaluation of the waterfront.

Over the past 20 years, the process of real estate speculation and investment has intensified in both the 22@ district and Barceloneta, driven by the city’s tourism pressure. Additionally, the area around the Forum has been transformed into a venue for massive music festivals.

When reflecting on the city today, few traces of its past remain. These territories have been stripped of their physical and social vestiges, leading to a state of “collective amnesia” [16].

3.2. The Battle for the Preservation of Industrial Heritage

Poblenou, historically the most important industrial district of Barcelona, underwent systematic dismantling as a result of the 1992 Olympic Games. Urban planning schemes prioritized redevelopment over preserving the local economy. The absence of a consistent policy to safeguard industrial heritage, including facilities and buildings of undeniable historical value, prompted considerable protests from experts and neighborhood movements [20]. Extensive efforts, mobilizations, and resources were dedicated to denouncing the complete disappearance of the industrial heritage of the former Icaria neighborhood within Poblenou, where interventions promoted by the Barcelona City Council led to the destruction of a significant number of operational businesses and factory buildings.

According to Mercè Tatjer, a leading expert in Barcelona’s industrial heritage, the 22@bcn Plan, approved in 2003, significantly accelerated the transformation of the industrial fabric. Until then, much of it had remained operational, hosting industrial activities alongside numerous small businesses in large factory complexes built between the mid-19th and mid-20th centuries [20]. These structures ranged from warehouses to extensive factory complexes, showcasing a remarkable diversity of architectural styles and functions. They supported a wide array of productions, from traditional textiles to modern consumer goods, as well as creative industries like design, artistic creation, editorial production, and graphic arts. However, only a minimal portion of this industrial heritage was preserved—around 30 elements, most of which were isolated chimneys. Criticisms regarding the demolition of this heritage, alongside the construction of the Olympic Village (including the destruction of economic activity, a lack of public housing, and an elitist project vision), garnered little media attention amid the widespread Olympic euphoria.

Similarly, in the port area, the transformation of the Inner Harbour (Port Vell) into a leisure and commercial zone resulted in a series of high-rise constructions for hotels and offices, along with the creation of a marina at the former Barceloneta docks. Once again, emblematic facilities and buildings of patrimonial significance were demolished, with very few exceptions—only two buildings were repurposed for new uses. Socially significant spaces, such as the chiringuitos of Barceloneta and the Sant Sebastià baths, were sacrificed under the objective of expanding and opening the city’s beaches.

In recent years, new redevelopment initiatives, such as the construction of the luxury W Hotel, known as Hotel Vela (2010), have drastically altered the traditional seafront landscape. This towering building, located within the Port Authority’s jurisdiction, was controversially granted private access to the beach, marking a significant transformation of Barcelona’s maritime skyline [21].

3.3. Reclaiming Collective Memory

Over the years, numerous initiatives have successfully reclaimed and preserved the memories of many lost and destroyed spaces. In recent years, there has been a significant number of books, reports, academic articles, and exhibitions dedicated to both the barracas and the industrial heritage of Poblenou. One noteworthy contribution is the collective work edited by Tatjer and Larrea [22] which brings together academic research, photographs, historical sources, maps, and testimonies. This initiative received substantial support from the University of Barcelona and the Museum of History of Barcelona (MUHBA), integrating historical, anthropological, and geographical perspectives.

In addition to documenting what has disappeared, some initiatives have strived to give a voice to the protagonists. Recovering the memory of the years of barraquisme was expressed through a citizen petition that gathered almost one hundred of neighborhood, social, and cultural organizations, as well as more than 800 individuals from various professional fields. The petition called for making the memory of Barcelona’s main barraques neighborhoods visible and honoring their residents through a series of commemorative plaques. The plaque installed at Somorrostro reads: “The shantytown of Somorrostro extended over more than a kilometer of coastline, from the Hospital del Mar to the mouth of the Bogatell. Thousands of people lived in fragile shacks on the sand, at the mercy of storms. Somorrostro existed from the late 19th century until it was urgently demolished in June 1966, just days before a naval exercise attended by dictator Francisco Franco. Along Barcelona’s coastline, from Barceloneta to Besòs, many shantytown settlements arose between the factories, the train tracks, and the sea. Those who lived here, hardworking people, contributed their effort to the growth of the city. Barcelona pays tribute to them.” [23].

Other significant initiatives in this regard include the urban guide Barraques/BCN, published by MUHBA, featuring a map of the main shantytown areas of the city, as well as various reports and press articles and media reports [24]. Among these, the award-winning documentary Barcelona, ciutat de barraques (2010) stands out for amplifying the voices of those who experienced this reality [25].

The testimony of the barraquistes has also given rise to innovative exercises in alternative mapping centered on their accounts and their use of space (Font-Casaseca and Benach, 2024) [17].

On the other hand, the memory of Poblenou is carefully preserved through the neighborhood’s historical archive, which remains highly active and serves as a vital resource for both researchers and residents. Nevertheless, its residents continue to face significant challenges, as demonstrated, for example, by the work of BCNUEJ. Their research links investments in urban greening to increasing social and economic inequalities, rising property values, and the displacement of working-class residents and historically marginalized communities. Their documentary The Green Divide explores these dynamics across six cities, identifying Barcelona’s Poblenou as one of the most critical cases. It highlights the massive gentrification driven by redevelopment initiatives such as the 22@ project, which has provoked ongoing protests and resistance from long-time residents. The voices and testimonies featured in the documentary underscore these challenges and the resilience of the affected communities [26].

4. Unveiling Layers: Insights and Perspectives for Shaping the Future

Thinking about the future depends largely on how we analyze and represent the present. In urban planning, visualization and cartographic representation play a crucial role. As Cosgrove highlights, urban space and cartographic space are inseparable [27]. Mapping typically precedes planning, as maps are expected to objectively reveal and define the foundational parameters upon which plans and projects are formulated, assessed, and implemented. This makes mapping more descriptive than prescriptive, focusing on capturing, visualizing, and analyzing spatial data to support planning decisions.

However, urban mapping has long struggled to effectively represent the multiple meanings and experiences associated with a single place [28]. The process of translating the material world into cartographic form requires selecting, simplifying, classifying, and converting reality into a graphic language. This inevitably produces a representation that is limited and partial compared to the true complexity of urban life. Consequently, urban maps depict only a fraction of what occurs in a given space, omitting other experiences, phenomena, and relationships. This issue is particularly pronounced in cities, where the density of elements, interactions, and temporal shifts makes simplification especially problematic. Furthermore, urban space presents both physical complexity—such as verticality, varied land uses, and diverse building typologies—and social complexity, which complicates efforts to accurately capture the diverse characteristics of urban populations.

While maps are useful in illustrating certain aspects of urban environments, they inevitably obscure others. The process of mapping a city is always selective, shaped by choices that determine which aspects of urban life are emphasized and which remain invisible. Moreover, the static nature of maps tends to reinforce fixed ideas about places, creating a sense of permanence that may not reflect reality. This is particularly evident when representing urban peripheries, which maps often portray as homogeneous or empty spaces. Such representations fail to capture their internal complexity or acknowledge the historical, social, and economic forces that have shaped them. Additionally, maps frequently overlook the effects of urban regeneration projects on local populations. As a result, spatiality, temporality, relationality, and change remain critical challenges for urban mapping. Questioning the linearity of time in cartographic representations is an important way to challenge the assumption that urban regeneration projects are universally beneficial [29].

The limitations of maps in representing dynamic processes, relationships, and changes are especially relevant today, as many global challenges—such as migration, climate emergencies, and capital flows—have strong temporal dimensions that require methodologies capable of capturing movement, trajectories, and transformations [30]. The need to disrupt the static, linear nature of traditional cartography and Geographic Information Systems (GIS) goes beyond analytical concerns—it is also a deeply political issue. By incorporating a more complex spatial and temporal perspective into mapping practices, scholars and practitioners can move beyond rigid representations that often obscure power asymmetries and structural inequalities. This approach fosters more nuanced, reflective, and politically engaged forms of spatial knowledge production.

4.1. Massey’s Spaces as a Simultaneity of Stories So Far

Building on Massey’s theory, the ways in which we conceptualize and represent space and time have significant implications [31]. Central to our argument is the claim that urban mapping plays a crucial role in regeneration processes by shaping which aspects, memories, structures of a territory are made visible, and which are obscured, often reinforcing dominant narratives. By depicting regeneration zones as vacant, degraded, or underutilized, mapping can erase the social and historical processes that have shaped these spaces, legitimizing top-down interventions that disregard existing residents and their lived experiences. Massey outlined three fundamental principles that challenge the static, enclosed view of space that dominates traditional cartography: (1) space is always the product of practices, relationships, connections, and disconnections; (2) space is the condition and possibility of multiplicity; and (3) space is always under construction, in a constant state of transformation. While the idea of places as closed, homogenous, and static entities may seem outdated, Massey argued that this perspective remains deeply ingrained and often goes unquestioned.

Even those who embrace Massey’s dynamic and relational view of space often rely on maps that are built on opposing, static premises. This reflects the enduring dominance of the Cartesian, absolute conception of space in urban planning. Rigid, static maps remain widely used due to their convenience in representing spatial problems and solutions, despite their limitations in capturing complexity, relationships, and dynamic processes.

For instance, Söderström’s analysis of zoning plans—a key urban planning tool—illustrates how mapping practices reduce the city to material objects or individuals treated as objects [32]. This approach categorizes people into social types, functional roles (living, working, traveling, recreating), or standard needs (comfort, noise regulations, household goods), shifting planning from social reform toward a more technocratic management of urban space.

In 2005, Massey highlighted the immense challenge of adopting an alternative conceptualization of space—not only in the social sciences but also in political engagement and everyday life. Rather than directly confronting this challenge, she argued that society tends to rely on “evasive imaginations” to avoid doing so [31].

She identified two such evasive tendencies.

Converting space into time: This is evident in classical development theories and grand narratives of progress. In this framework, spatial diversity is reduced to a single, linear sequence, leaving no room for alternative trajectories. For example, “underdeveloped” countries are positioned within a fixed developmental timeline that denies them agency to define their future. This linear interpretation disconnects spaces from one another, concealing the structural causes of inequalities and reinforcing rankings based on development indicators. Over time, this thinking has legitimized centuries of exploitation and domination while shaping everyday perceptions of global disparities.

Viewing space as timeless: Here, space is treated as a passive backdrop where events unfold. This perspective detaches space from the actors and processes that actively shape it through movement and interaction. The culmination of this logic is the conflation of space with the map itself—a mindset dating back to classical colonialism. Colonial maps often depicted subjugated territories as voids, erasing their historical depth and silencing the lived realities of their inhabitants. Efforts to decolonize cartography emphasize restoring Indigenous place names and ancestral memories to challenge these historical erasures [33].

In response to these reductive views, Massey defended a unified concept of space-time, where both dimensions are mutually constitutive. Space, as a social dimension, is inseparable from temporality—it is the realm of multiple trajectories. Likewise, time depends on space, as transformations and change unfold within spatial contexts.

By embracing this relational approach, scholars and practitioners can work toward mapping practices that move beyond static, reductionist representations to recognize the fluid, interconnected, and contested nature of spatiality.

4.2. The Power/Agency of Maps

Despite their limitations, urban mapping is conventionally regarded as stable, accurate, and an unquestionable reflection of reality. The prevailing assumption is that if a survey is quantitative, objective, and rational, it must also be true and neutral. This perception reinforces the legitimacy of future plans and decisions, unmasking underlying power dynamics and biases. This leads to a fundamental problem with urban cartographic representations, their perceived transparency and accuracy once they have been created obscure the processes, and decisions made to select and prioritize which stories, bodies, and pasts will be represented.

Wood and Fels argue that the power of maps lies in their effectiveness [34]. For Söderström, cartographic processes create a specific visual technology that exerts power through a dual mechanism of efficacy [32]. First, an internal efficacy allows complex realities to be translated into simplified representations through a series of technical processes and decisions. Second, an external efficacy legitimizes these representations as authoritative, professional, and scientifically constructed visions of the world [35]. In urban planning and management, the external efficacy of maps is reinforced by the technical complexity of their production, which remains the domain of professionals trained in architectural drawing, urban terminology, and specialized design. This expertise enables maps to serve as persuasive tools, convincing non-experts, such as policymakers and citizens, of the legitimacy of urban policies.

From a critical cartography perspective, the power of maps has also been analyzed at two levels. First, there is external power, exercised by those who commission maps to serve their own interests. Second, there is internal power, through which cartographers themselves contribute to the authority of maps by shaping their construction and design [36]. These dynamics highlight how maps are not merely neutral representations but rather instruments that actively shape perceptions of space, influence decision-making, and reinforce existing power structures.

Scientific cartography’s inability to capture the complexity of urban space has at the same time opened new possibilities for urban mapping. Following Corner, maps have “agency” because of their double-sided analogous and abstract character [37]. First, maps are often perceived as true and objective representations of reality due to their direct correspondence with the physical landscape. Like shadows cast on the ground, they translate real-world features onto paper through geometric projections, allowing users to trace routes and visualize spaces. We trust in maps because they are useful when we need them. However, their very nature is inherently abstract, shaped by selection, omission, and generalization, revealing other geographies that remain unavailable to human eyes. Thus, mapping typically precedes planning because it is assumed that the map will objectively identify and make visible the terms around which a project can be developed.

But as it has been argued, the “agency” of mapping also lies in their potential for uncovering realities previously unseen or unimagined, even across seemingly exhausted grounds [37]. A more optimistic, creative view of mapping shows that “mapping unfolds potential; it re-makes territory over and over again, each time with new and diverse consequences.” [37] p. 213. Here, we turn to the power of maps to redefine them as powerful instruments for uncovering and connecting those other stories, times, and presences.

4.3. Layers

Since the discipline of urban planning was founded, the characteristics of urban space have primarily been represented by means of visual abstraction and reduction using thematic maps as urban layers to describe functions, spaces and buildings graphically [38]. Historically, the concept of layered spatial analysis in urban planning emerged through thematic mapping in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, and it was used by pioneers in planning, such as Geddes, Howard or Le Corbusier as a method to conceptualize urban complexity in a structured abstraction. Adding or removing layers enhances the visualization of relationships between spatial elements or time periods. This results in thematic maps that reduce the diverse range of information on the maps to the key aspects. With the advent of Geographic Information Systems (GIS), these historical layering principles evolved into dynamic, data-driven decision-making tools. GIS and digital twin cities allow planners to digitally overlay diverse spatial datasets to conduct advanced spatial analyses and real-time urban monitoring and predictive modeling [39,40].

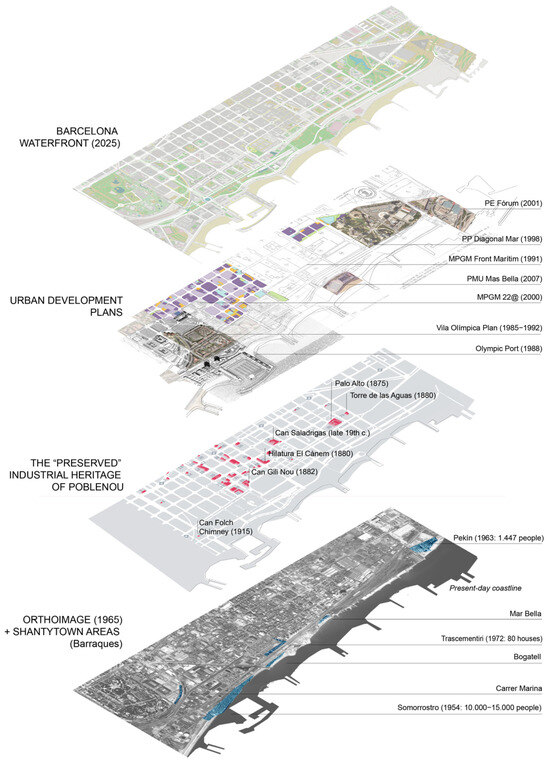

Our proposal is to use the potential of an overlapping framework of layers (Figure 3) to reveal the complexity and diversity of space below and beyond the places where redevelopment takes place. spaces that the hegemonic discourse so easily covers. The inclusion of historical layers is often missing in urban mapping and planning [41]. This results in a simplified historical narrative that overlooks individual agency, ideological influences, and the impact of visual instruments.

Figure 3.

Overlapping layers in Barcelona’s waterfront redevelopment. Source: Compiled by the authors. Data source, from top to bottom: 1. Topographical map from the Geoservices of the Barcelona City Council Spatial Data Infrastructure 2. Urban Development Plans for Poblenou, from Barcelona Urban Information Map. Available online: https://ajuntament.barcelona.cat/informaciourbanistica/cerca/en/ (accessed on 14 March 2025) 3. “The industrial Heritage of Poblenou”, by El Globus Vermell. Available online: https://elglobusvermell.org/serveis/difusion/el-patrimonio-industrial-del-poblenou-barcelona/ (accessed on 14 March 2025) 4. ref. [22] and Orthoimage from the Geoservices of the Barcelona City Council Spatial Data Infrastructure.

Other layers, other maps, can reveal how temporality not only unfolds over time, but it is also present in the landscape of today, below and beyond, at other scales. Moreover, recognizing this temporality could play a pivotal role in designing a fair and inclusive space for all. Below, it relates with the metaphor of the palimpsest, where the present landscape is not only a kind of constant overlapping of physical layers and traces of tangible and ephemeral memories to be explored anew in each historical moment, just as in every urban journey [42], or rather an erasure that always leaves traces of what was there before [43], but it also can offer new meanings to existing elements. As Kobayashi points out, “landscape is a process totalized, a work-in-progress and a collection of human activity in a material setting which includes both its history and its potential” [44] p. 41.

Moreover, linking these memories to other places not only helps to integrate local narratives but also connects the micro-histories of transformed spaces to broader socio-spatial processes along time. The complex relationships between spaces and times should be integrated not only into the explanation but also into their representation. However, to articulate a dynamic and relational understanding of space, maps must creatively explore alternative ways of representation beyond traditional cartographic conventions. Our proposal highlights the need to create maps that not only serve as base maps for future developments but also point to the causes of spatial transformations, the relational dynamics inherent in all urban processes, and the lived experiences of those who witnessed and participated in these changes.

5. Conclusions

What we have sought to demonstrate in this text is the unjust and socially exclusive nature of urban regeneration that tends to disregard pre-existing conditions. Plans are often drawn on the map over what already exists, erasing it abruptly and creating the illusion that transformation is imposed upon a void.

Here, we have examined the hegemonic discourse on the transformation of Barcelona’s waterfront, comparing it to the stories of those who were displaced, the heritage and landscape that were destroyed, and the memory and urban ways of life that were erased.

We argue that proper and fair urban planning for residents must take into account all pre-existing elements in its design. Achieving the goal of “a city for the many, not the few”, as referenced in the title of the book by British geographers Pile, Massey, and Thrift [45] (or its counterpart Cities for People, Not for Profit by critical urban theorists Brenner, Marcuse, and Mayer [46]), requires visual tools that incorporate these considerations. Our proposal for a “framework of layers” to support future plans aims to contribute precisely in this direction.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.B. and N.F.-C.; methodology, N.B. and N.F.-C.; writing—original draft preparation, N.B. and N.F.-C.; writing—review and editing, N.B. and N.F.-C.; visualization, N.F.-C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This publication is part of the R&D&I project “Spaces of Resistance and Survival Networks in Urban Margins” (REDSIST) PID2021-126786OB-I00, funded by MCIN/AEI/10.13039/501100011033/ FEDER, EU.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author(s).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Lefebvre, H. The Production of Space; Blackwell Publishing: Oxford, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, P. The Inner City in Context; Gower Publishing: Aldershot, UK, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Harvey, D. From managerialism to entrepreneuralism: The transformation in urban governance in late capitalism. Geogr. Ann. 1989, 71, 3–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, P. Cities of Tomorrow; Basil Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Harvey, D. The Urbanization of Capital; Basil Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Ferrer, A.; Nello, O. Barcelona: La transformació d’una ciutat industrial. Pap. Regió Metrop. Barcelona 1991, 3, 11–30. [Google Scholar]

- Maragall, P. Refent Barcelona; Planeta: Barcelona, Spain, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Benach, N. Producción de imagen en la Barcelona del 92. Estud. Geogr. 1993, LIV, 483–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dematteis, G. Immagine e identità urbana: Metafore spaziali ed agire sociale. CRU Crit. Razion. Urban. 1995, 3, 88–93. [Google Scholar]

- Holcomb, B. City make-overs: Marketing the post-industrial city. In Place Promotion: The Use of Publicity and Marketing to Sell Towns and Regions; Gold, J.R., Ward, S., Eds.; John Wiley and Sons: Chichester, UK, 1994; pp. 115–131. [Google Scholar]

- Maliene, V.; Wignall, L.; Malys, N. Brownfield regeneration: Waterfront site developments in Liverpool and Cologne. J. Environ. Eng. Landsc. Manag. 2012, 20, 5–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, P.J.; dos Santos, G.L. Olympic Waterfronts: An Evaluation of Wasted Opportunities and Lasting Legacies. Sustainability 2022, 14, 1968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fábregas Riverola, I.; Sabaté Bel, J. Bonitas vistas frente al mar. Quad. Recer. Urbanisme 2017, 7, 62–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busquets, J. Barcelona: The Urban Evolution of A Compact City; Nicolodi: Rovereto, Italy, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Grup de Treball d’Etnologia de l’Espai Públic de l’Institut Català d’Antropologia. Pla de la Ribera: El Veinat Contra la Dictadura. 2006. Available online: https://www.antropologia.cat/estatic/files/Pla%20de%20la%20Ribera%20INFORME%20FINAL%20-%202006.pdf (accessed on 14 March 2025).

- Navas Perrone, M.G. Utopía y Privatopía en la Vila Olímpica de Barcelona. Ph.D. Thesis, Universitat de Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Font-Casaseca, N.; Benach, N. Márgenes urbanos: Ideas para cartografiar «el lugar más allá del lugar». In Cartografías Críticas de las Periferias Urbanas; Canosa, E., García Carballo, A., Eds.; Tirant Humanidades: Valencia, Spain, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Benach, N. En las fronteras de lo urbano: Una exploración teórica de los espacios extremos. Scr. Nova Rev. Electrón. Geogr. Cienc. Soc. 2021, 25, 11–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caballé, F. Desaparece el barrio de Icària, nace la Vila Olímpica. Biblio 3W. Rev. Bibliogr. Geogr. Cienc. Soc. 2010, 15, 9. [Google Scholar]

- Tatjer, M. Diez años de estudios sobre el patrimonio industrial de Barcelona. Scr. Nova Rev. Electrón. Geogr. Cienc. Soc. 2008, 12, 140. [Google Scholar]

- Tatjer, M.; Tapia, M. Ciutat i port, un debat necessari. Biblio 3w Rev. Bibliogr. Geogr. Cienc. Soc. 2013, 18, 1049. [Google Scholar]

- Tatjer, M.; Larrea, C. Barraques: La Barcelona Informal del Segle XX; Museu d’Història de Barcelona-Ajuntament de Barcelona-Institut de Cultura: Barcelona, Spain, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Ajuntament de Barcelona. Barcelona Recupera la Memòria dels Barris de Barraques. Dossier de Premsa 25 de Novembre del 2014. Available online: https://ajuntament.barcelona.cat/premsa/wp-content/uploads/2014/11/1411xx_Placa-Somorrostro.pdf (accessed on 14 March 2025).

- Carnicer, A.; Grimal, S.; Tatjer, M. Barraques/BCN. Guia d’Història Urbana. 2011. Available online: www.museuhistoria.bcn.cat (accessed on 14 March 2025).

- Carnicer, A.; Grimal, S.; Barraques. La Ciutat Oblidada, (Documental). 2010. Available online: https://www.ccma.cat/3cat/barraques-la-ciutat-oblidada/video/2333059/ (accessed on 14 March 2025).

- Bougleux, A.; The Green Divide. Urban Struggles for Environmentall Justice. BCNUEJ. ICTA-UAB. 42 min. 2024. Available online: https://www.bcnuej.org/the-green-divide/ (accessed on 14 March 2025).

- Cosgrove, D. Carto City. In Else/Where: Mapping New Cartographies of Networks and Territories; Abrams, J., Hall, P., Eds.; University of Minnesota Press: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Jung, J.-K.; Elwood, S. Qualitative GIS and Spatial Research; SAGE Publications Ltd.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Font-Casaseca, N.; Rodó-Zárate, M. From the margins of Geographical Information Systems: Limitations, challenges, and proposals. Prog. Hum. Geogr. 2024, 48, 03091325241240231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, M.W. GIScience III: Questions of time. Prog. Hum. Geogr. 2022, 46, 1431–1438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massey, D. For Space; Sage Publications Ltd.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Söderström, O. Paper Cities: Visual Thinking in Urban Planning. Ecumene 1996, 3, 249–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose-Redwood, R.; Blu Barnd, N.; Lucchesi, A.H.; Dias, S.; Patrick, W. Decolonizing the Map: Recentering Indigenous Mappings. Cartogr. Int. J. Geogr. Inf. Geovisualization 2020, 55, 151–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, D.; Fels, J. The Power of Maps; The Guilford Press: Guilford, NY, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Söderström, O. Des Images pour Agir: Le Visuel en Urbanisme; Payot: Paris, France, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Harley, J.B. Deconstructing the map. Cartogr. Int. J. Geogr. Inf. Geovisualization 1989, 26, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corner, J. The Agency of Mapping: Speculation, Critique and Invention. In The Map Reader, 1st ed.; Dodge, M., Kitchin, R., Perkins, C., Eds.; John Wiley and Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2011; pp. 89–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinrich, A.J.; Marguin, S.; Million, A.; Stollmann, J. (Eds.) Handbook of Qualitative and Visual Methods in Spatial Research, 1st ed.; Transcript Verlag: Bielefeld, Germany, 2024; Volume 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batty, M. Big data, smart cities and city planning. Dialogues Hum. Geogr. 2013, 3, 274–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kitchin, R.; Young, G.W.; Dawkins, O. Planning and 3D Spatial Media: Progress, Prospects, and the Knowledge and Experiences of Local Government Planners in Ireland. Plan. Theory Pract. 2021, 22, 349–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolen, J.; Renes, H.; Hermans, R. (Eds.) Landscape Biographies: Geographical, Historical and Archaeological Perspectives on the Production and Transmission of Landscapes; Amsterdam University Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Golda-Pongratz, K. Creación de lugar desde el palimpsesto urbano. Estud. Escèn. 2019, 44, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Río Fuentes, C.D. Palimpsestos: Las Huellas del Tiempo en la Arquitectura; Trabajo Final Project, E.T.S. Arquitectura, Universidad Plitécnica de Madrid: Madrid, Spain, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi, A. A Critique of Dialectical Landscape. In Remaking Human Geography; Kobayashi, A., Mackenzie, S., Eds.; Unwin Hyman: Boston, MA, USA, 1989; pp. 164–184. [Google Scholar]

- Amin, A.; Massey, D.; Thrift, N. Cities for the Many Not the Few; Policy Press: Bristol, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Routledge. Cities for People, Not for Profit. Critical Urban Theory and the Right to the City; Brenner, N., Marcuse, P., Mayer, M., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).