Abstract

As official terms included in the International Council on Monuments and Sites (ICOMOS) documents, archaeological site parks have gradually emphasized the establishment of sustainable management frameworks for archaeological sites open to the public and enhancing public experiences. The management frameworks should be closely related to the goals of the United Nations and other international conventions on sustainable development. However, they lack implementation strategies to promote archaeological site protection and provide responsible tourism. This research adopts a multi-case study approach to analyze the management of representative archaeological site parks in the United States, Japan, and China to develop a framework for the sustainable management of archaeological site parks. Various values, heritage tourism activities, and public perceptions of each park are examined based on cross-case analysis, which identifies principal elements and strategies for the sustainable management of archaeological parks. The principal elements reflect the archaeological parks’ intrinsic value, utility value, and other values. The strategies are closely related to the design of heritage tourism activities and are in alignment with the UN’s sustainable development goals. The theoretical and practical contributions of this research include the reflection and explanation of the sustainable management practices of archaeological site parks in different national and cultural contexts, considering public perceptions. The proposed framework and strategy integrate management guidelines, theoretical knowledge, and practical experience of public archaeological site parks. The outcomes of this research provide a reference for the study of archaeological parks and the management of heritage landscapes.

1. Introduction

As precious, fragile, and non-renewable cultural heritage shared by humankind, archaeological site parks are an essential part of the heritage system of a nation’s culture. This intrinsic value is interpreted as the essential significance or meaning of cultural heritage [1], reflecting how it protects itself in a continuous regeneration process and a dynamic environment [2]. The intrinsic value is closely related to the intangible value of the heritage [3]. Archaeological site parks are defined as “the link between scientific research and the public, and it can be termed as a definable area, distinguished by the value of heritage resources and land related to such resources, having the potential to become an interpretive, educational and recreational resource for the public, which should be protected and conserved” [4]. Salalah Guidelines for the management of public archaeological site parks were published in 2017 [5]. These guidelines introduces the key considerations for managing archaeological site parks, such as conservation and preservation, interpretation and education, and visitor services and facilities, for effective archaeological parks management.

Nevertheless, despite the fact that some countries prioritize the intrinsic value protection of site resources and the quality of heritage tourism, the complexity and trade-offs involved in the management activities of archaeological site parks may lead to various challenges if diverse management techniques and sustainable management practices are absent [6]. With global cultural heritage conservation transitioning from “static preservation” to “dynamic and sustainable governance” [7], the management paradigm of archaeological site parks urgently needs to balance sustainability and public participation more effectively.

The literature on the management of archaeological site parks is growing, with many studies mentioning protecting World Heritage sites [8], thereby guiding those involved in conserving site resources. Early research on managing archaeological site parks focused on legislative management at the macro level, including the conservation guidelines and best practices within archaeological sites [9]. As research on the management of archaeological site parks deepened, it concentrated on themes such as the management of site values [10], presentation management [11], heritage tourism management [12] and visitor management [13]. With the increasing uncertainty of the external environment, the vulnerability of the integrity of site resources and the significance of archaeological culture has been heightened. The management of archaeological site parks has gradually shifted from protecting physical heritage to incorporating cultural and humanistic dimensions [14]. The importance of public participation in sustainable management has slowly been recognized [15]. The multiple roles of archaeological site resources at the national, regional, and community levels are being valued, with recent emphasis on promoting sustainable development goals [16].

Despite recognizing the importance of sustainable management planning by the managers of archaeological site parks, few studies have integrated public perception and value of the sites when deciding which management goals to prioritize. Moreover, most previous studies on the sustainable management of archaeological site parks have focused on specific ancient sites and concentrated on the mono-management dimension [17,18]. It is, therefore, necessary to study multidimensional sustainable management practices across regional and cultural contexts, deconstruct multidimensional representations of sustainable management of archaeological site parks, and propose an inclusive sustainable management framework that incorporates public perspectives. This framework aims to achieve a balance in management strategies and improve local management practices at the sites.

This research investigates the cultural values and practices, activities and public perception of successful archaeological site parks to identify strategies for sustainable archaeological site park management. Three cases were selected from the United States, Japan, and China based on the criteria of the historical significance, the importance of their scale and unearthed cultural relics, their preservation and utilization through the national park model, the typicality of development and utilization, and the emphasis on scientific research, education, and recreational function. All cases have outstanding performance in demonstrating heritage preservation and developing cultural heritage tourism that has received global attention. To emphasize the unique integration of heritage conservation with contemporary tourism development and highlight the role of public perceptions in shaping sustainable heritage management, this research aims to address the following research questions:

RQ1. What values are essential for heritage preservation?

RQ2. What heritage tourism activities prevail in archaeological site parks?

RQ3. How can public perception be used to improve heritage tourism activities to achieve sustainable management?

2. Literature Review

2.1. Heritage and Archaeological Site Parks

Heritage is what humanity has inherited from history [19] and it encompasses the tangible and intangible aspects of cultural identity passed down from previous generations, including traditions, beliefs, artifacts, monuments and historical sites [20]. Archaeological heritage refers to the physical remains of past human activity, such as ancient structures, artifacts, and landscapes, which hold significant historical, cultural, and scientific value [21]. Archaeological heritage plays a crucial role in preserving and understanding the collective human experience, providing insights into our shared history, identity and cultural diversity. These assets serve as tangible links to the past and connect present-day societies with their ancestors and predecessors. Archaeological heritage offers educational inspiration and reflection opportunities, fostering community continuity and belonging [22]. Public archaeological site parks provide opportunities for education and interpretation and allow visitors to learn about the history, culture, and daily lives of past civilizations through direct engagement with archaeological sites, artifacts, and exhibits [23]. Hands-on experience fosters a deeper understanding and appreciation of our shared heritage, promoting cultural awareness and historical literacy. Also, public access to archaeological site parks promotes preservation and conservation by raising awareness about the value and significance of these sites. When people experience and connect with archaeological site park remains firsthand, they are more likely to support efforts to protect and maintain them for future generations [24]. Additionally, archaeological site parks can stimulate local economics by attracting tourists, creating jobs, and supporting small businesses in surrounding communities [25].

2.2. Heritage Tourism in Archaeological Site Parks

Heritage tourism consists of activities and concepts people can focus on to discover a place’s history and unique characteristics. Heritage tourism is responsible for preserving and restoring the historical or cultural structures that are elements of the tourism resource [26]. These include all types of activities on the Recreation Activity Spectrum [27], such as daily outdoor recreation, sightseeing, recreation, and leisure activities. They are a way to make the public aware of the value of cultural diversity and a powerful tool for cultural heritage conservation and sustainable development.

The relationship between tourism and archaeological site park management is delicate, requiring a balance between conservation and accessibility [28]. Tourism plays a crucial role in preserving archaeological parks by providing essential findings for research, maintenance, and interpretation [29]. Archaeological sites such as Pompeii in Italy, Machu Picchu in Peru, and the Great Wall of China have utilized ticket revenues and tourism programs to ensure the continuous maintenance and restoration of the sites. They have also employed digital technologies to enrich the tourism experience for visitors, reduce direct contact with the sites, and preserve their integrity [30,31,32]. However, the excessive introduction of new tourism activities or the expansion of existing ones at historical sites may generate a variety of negative consequences. Different case studies have demonstrated the various harms caused to cultural heritage sites by visitors and their related activities, including the physical degradation of the sites themselves [33] and the loss of site value and authenticity due to the proliferation of infrastructure [34]. Managing tourism within these parks presents challenges, such as preventing damage to delicate structures and minimizing the impact of visitor’s activities. Thus, managing tourism within archaeological site parks involves careful planning, infrastructure development, visitor education, and collaboration with local communities [35]. By fostering sustainable tourism practices, archaeological site park management can safeguard these sites’ integrity and offer enriching experiences for visitors, thereby ensuring their preservation for future generations to appreciate and learn from [36]. Simultaneously, the rapid development of heritage tourism also brings risks, such as the phenomenon of “overtourism” or indirect damage to heritage. These risks are related to social, economic, and cultural impacts, which also provoke restrictions on the rights to visit and enjoyment of cultural heritage. Therefore, it is necessary to readjust tourism methods based on public perception to reduce unsustainable issues.

2.3. Sustainable Management of Archaeological Site Parks

The “Salalah Guidelines for the Management of Public Archaeological Sites” emphasize the need for a sustainable management system for archaeological sites, monuments, and landscapes [37]. Currently, research on the sustainable management of archaeological site parks focuses on aspects such as the balance between site protection and development [38], financial support mechanisms [39], public participation [40], and the dissemination of cultural values [41]. However, the contradiction between site protection and tourism development remains prominent, with various challenges such as limited public participation, lack of policy support, and uneven economic stimulation. Sustainable tourism practices aim to minimize adverse environmental and cultural impacts while maximizing the benefits for local communities. This includes initiatives such as promoting responsible tourism behavior, implementing eco-friendly infrastructure, and supporting local businesses. Community engagement is essential for ensuring that tourism development aligns with the needs and aspirations of residents, fostering a sense of ownership and pride in their cultural heritage. Moreover, providing high-quality visitor experiences involves maintaining the integrity of attractions, offering authentic cultural interactions, and delivering exceptional hospitality services. Continuous monitoring, evaluation, and adaptation ensure that tourism management strategies remain effective and responsive to changing circumstances. By embracing these principles, destinations can achieve sustainable growth, preserve their unique identity, and enhance the overall quality of the visitor experience.

Since the perceptions of the value of archaeological site parks are not static, sustainable management must understand the intrinsic value [42] of the site in linking the historical with the contemporary. Additionally, the intrinsic value generates other utility values that people recognize according to the changing context. In other words, the history and culture of a particular heritage, produced, created, or recognized by people over a long time, help us to acknowledge our roots and identity, form the basis of its intrinsic value [43], make a particular place unique [44], and serve as further tools and arguments for its conservation. Therefore, identifying and determining the site’s historical and cultural values is a vital part of linking the site’s resources to conservation and utilization practices and helps to fundamentally link the intrinsic value of the site to a sustainable management system for the archaeological site park [45]. Roszczynska-Kurasinska measured the intangible value of urban parks and found that the concept of intrinsic value can be transformed into a specific variable that can be used to measure and explain different preferences and visions for the development of park spaces and the better planning and management of heritage sites [46].

Furthermore, the intrinsic value of cultural heritage can be expressed through complex social values [47]. Social value is localized based on local belonging, cultural identity, collective memory, and everyday interactions between people and heritage sites [48]. It has become an integral part of heritage integrity and sustainability. When discussing social value concerning archaeological site parks, it is crucial to recognize that archaeological remains are not just a passive representation of the past but an active factor through which messages and meanings are created and transformed. The case of Matera [49] shows how the concept of intrinsic value contributes to understanding why some places radiate energy, mobilize communities, and promote local sustainable development.

2.4. Public Perception

Public perception is the best snapshot of the effectiveness of sustainable management and involves human feelings, perceptions, emotions, behaviors, and environmental psychology [50]. Public experiences and perceptions include three structural dimensions: functional, emotional, and social [51]. The functional dimension primarily focuses on the extent to which tourists’ practical and functional needs are met at a tourist destination or cultural heritage site. This includes the accessibility of transportation, the completeness of facilities, the availability of information, and the quality of services [52]. The emotional dimension focuses on tourists’ emotional experiences and psychological feelings during travel, including their emotional connection to the destination, satisfaction, pleasure, and sense of belonging [53,54]. The social dimension focuses on tourists’ social interactions and community participation during travel, including interactions between tourists and local residents, communication with other tourists, and understanding and respect for the local social and cultural context [55]. Public perceptions have a significant impact and relevance in understanding the motivations and interests of the public [30]. They also indicate the public’s satisfaction with the destination [56], which is essential for the image of the heritage site.

As visitors to archaeological site parks, the public is the direct perceiver and feedback of heritage tourism and management activities in the parks, as well as the beneficiary, implementer, contributor, and contemporary witness of sustainable management activities. The existing research has shown that conservation awareness can be enhanced by improving the tourist experience, leading to a more positive attitude toward conservation. Nian et al. investigated the behavioral intentions of visitors to Sanqingshan National Park toward heritage conservation and found that good experiences and perceptions positively affected conservation intentions and could further increase conservation intentions, which is of great significance for the sustainable development of cultural heritage and the management of heritage sites [57]. Gkoltsiou and Paraskevopoulou assessed the perceptions of the key stakeholders, including tourists, and provided guidelines and methods for landscape management in historical parks. These contents also provide reference and inspiration for archaeological site parks. Hossein Mousazadeh studied the case of the World Heritage Site of Qanats in Persia and, based on public perceptions, developed an integrated model that influences the behavior of tourists, officials, and locals to ensure the sustainable conservation of these valuable underground heritage sites, which provides public support and financial resources for the sustainable management of underground heritage [58].

Promoting sustainable management is not only the task of the archaeological site park but also relates to the public experience and perception. Public experience and perception can be used as an engine for the success of the tourism industry and can provide a course of action and regulatory framework for heritage managers [12]. Normative theory and visual research methods were employed to measure the perceived crowding of the public at the Tulum archaeological site. The results indicate that a scientifically defined visitor management framework enhances the quality of the visitor experience. Identifying and managing excessive visitor numbers is conducive to balancing the dual tasks of resource conservation and high-quality tourism, thereby promoting the sustainable development of the site and its heritage [59].

Understanding the public’s perception is helpful for the management of archaeological site parks. Heritage management plans must include tourism sustainability and visitor management strategies, enhance the public experience, and adjust management policies through sensitive interpretation and presentation methods. In short, responsible tourism and sustainable management of archaeological site parks should fully consider public perception to enhance social, economic, and cultural well-being.

2.5. Summary

In summary, the conservation of the characteristics and values of archaeological sites is the core of the management of archaeological site parks, involving the integration and management of conflicts between intrinsic and utilitarian values (mainly historical, cultural, and social values). Actions to protect cultural heritage must focus on the characteristics and particularities of the place [60], achieving a balance between site integrity and sustainable tourism. Public perception about the parks should also be taken into account when developing sustainable management frameworks or strategies. These can be used to introduce innovative solutions for archaeological site parks to ensure their vitality, sustainability, and other positive social impacts. Hence, this study reviews the practices of archaeological site parks in different cultural contexts, focusing on the effective management of values and heritage tourism, and develops a sustainable management framework and strategies incorporating public perspectives.

3. Research Methods

3.1. Why Case Study Method Is Used

This study aims to develop a framework guiding the sustainable management of archaeological site parks based on understanding sustainable management practices and public perceptions in different cases. Multiple case studies were examined to understand current situations and practical phenomena in real-life settings, using various data collection methods to obtain information on one or more case entities (people, groups, or organizations) [61]. This allowed the research to explore the complexity and richness of the phenomenon under investigation and compare its multiple perspectives and facts. This approach also facilitates microscopic insights into the causal relationships between subjects’ motives, behaviors, and consequences in typical cases [62]. Moreover, multiple cases can enhance the credibility and reliability of the research. Specifically, cross-case comparisons based on numerous cases are used to identify possible relationships between the cases [63] to ensure the robustness of findings is more explanatory [64]. Multiple cases can increase the transferability and applicability of research by showing how the findings can be relevant to different contexts and scenarios.

3.2. Case Selection

Three cases from the United States, Japan, and China were selected to learn from various cultural practices and sustainable management components [65] and promote managers’ understanding of the diversity of values and all forms of management of archaeological sites. The selected cases are Chaco Culture National Historical Park in the United States, Yoshinogari Historical Park in Japan, and Daming Palace National Heritage Park in China. Specifically, Chaco Culture National Historical Park in the United States symbolizes North American indigenous culture. It is renowned for its unique architectural style, cultural commemorative significance, and astronomical observatories. Listed as a World Heritage site in 1987, the park helps people understand its historical value and enhances cultural heritage protection awareness through stargazing activities, tribal life, archaeological research, and educational programs. Yoshinogari Historical Park in Japan is on the most prominent site of the Yayoi period under the national park model in Japan. It was established to preserve and utilize its unique and outstanding cultural heritage. In recent years, the number of foreign visitors to Yoshinogari Historical Park has increased by 200% annually, and the park has played a more significant role in the international dissemination of Japanese culture. Daming Palace National Heritage Park in China is the most famous royal palace complex from the prosperous Tang dynasty, known as the “Palace of a Thousand Palaces”. It was one of China’s first national archaeological site parks and was inscribed on the World Heritage List in 2014. During the Spring Festival in 2024, the park received approximately 516,000 visitors. The park has been recognized for its achievements in site interpretation, cultural heritage, and environmental beautification, especially in the harmonious coexistence of cultural heritage protection and urban development.

Hence, these archaeological site parks were chosen because of their significance and archeological value in their countries, together with their outstanding universal values and extraordinary qualities. They also share certain commonalities, such as promoting sustainable management under international guidelines and charters and domestic conservation and development policies. In addition, the three parks also emphasize responsible heritage tourism as a way to realize the integrated functions of archaeological site parks in research, recreation, and education. Meanwhile, the cases provide evidence for contrasting comparisons in cultures, economic scales, and statuses of World Heritage backgrounds.

The background and description of the three archaeological site parks are presented in Table 1. The three cases represent archaeological site parks with different economies, funding systems, and indigenous or historical cultures.

Table 1.

Case descriptions of the archaeological site parks.

3.3. Data Collection and Analysis

Qualitative data were collected through several sources and methods, including first-hand data from site visits, secondary data collected on relevant websites, and document analysis. To answer the research questions, the data collection and analysis was carried out in the following steps:

- To answer RQ1, the authors searched the three parks’ management systems and official websites and reviewed the related literature to analyze archaeological site parks’ historical, cultural, and social values;

- To answer RQ2, the authors visited, examined, and documented the activities of sustainable tourism and management practices in the three archaeological site parks in the field and summarized and comparatively analyzed them based on a literature review;

- To answer RQ3, the authors read the public review comments of the three archaeological site parks on TripAdvisor and analyzed the public’s perceptions and experiences using KH-CODER software. Based on the analyses of RQ1 and RQ2, we came up with a set of strategies to promote the sustainable management of the archaeological site parks.

Data were collected through several public websites, as shown in Table 2. The public review comments of Chaco Culture National Historical Park, Yoshinogari Historical Park, and Daming Palace National Heritage Park were collected on TripAdvisor. Chaco Culture National Historical Park had 768 reviews, Yoshinogari Historical Park had 355 reviews, and Daming Palace National Heritage Park had 103 reviews (as of 15 June 2024).

Table 2.

Sources for the case data collection.

TripAdvisor was selected for the review comment collection since it is one of the world’s largest travel review platforms, with reviews available in 28 different languages. The website uses strict moderation mechanisms to eliminate review spam, including an automated detection system, a user reporting mechanism, and a human moderation team. In data analysis, the following steps were adopted to ensure the reliability of the data and reduce the impact of bias on the analysis results: (1) excluding comments that were too brief or repetitive and (2) filtering out reviews with extreme ratings (e.g., only 1 or 5 stars) and empty content. The review comments were then exported to KH Coder software to perform a unified word process. Word-to-word collinear relationship graphs were generated after repeatedly adjusting the co-occurrence network diagram to set the minimum number of occurrences.

Public perception data were collected from the open-access platform TripAdvisor, as shown in Table 3. TripAdvisor is the world’s largest travel guide platform, with over 1 billion reviews and the opinions of nearly 8 million businesses. The site is considered one of the largest online shared comment travel databases. In addition to comments, users also report their demographic characteristics, travel characteristics, and ratings on the performance of various tourist attractions, hotels, and restaurants [66]. TripAdvisor’s reviews are categorized by tourists’ ratings on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = terrible and 5 = excellent).

Table 3.

Sources for collections of public perception data.

This study used the content analysis software K.H. Coder to interpret the high-frequency words of the reviews of the three archaeological site parks on TripAdvisor’s travel platforms and conduct a semantic network co-occurrence analysis to explore the public’s mixed perceptions.

4. Results

The following sections provide the analytical results in terms of the historical, cultural, and social values, heritage tourism activities, and public perceptions of the three archaeological site parks. In order to facilitate identification and comparative analysis, the names of the cases are mainly based on the official website and search platform.

4.1. Values Addressed by the Three Archaeological Site Parks

4.1.1. Value Addressed in Chaco Culture National Historical Park, US

Chaco Park was a thriving regional center for the ancestral Pueblo people from 850 to 1250 CE (Common Era), with approximately 4000 archaeological sites representing more than 10,000 years of human cultural history [67]. It preserves the environment of Indigenous culture and promotes Indigenous history and culture. The natural landforms of the park are unique, creating an ancient environmental legacy and a wide variety of ecological zones under the influence of the climate, which is of local significance. This diversity may account for a long history of human occupation, at least 7000 years in Chaco. The park employs a variety of conservation treatments for the long-term protection and scientific study of these fragile resources while still allowing the public to explore and study them, increasing their understanding of Native American history and Indian culture. It can be seen that Chaco Park has rich cultural, historical, and social values. As a combined natural and cultural site, preserving Chaco Cultural and Historical Park also involves the protection of the surrounding ecosystem, promoting the maintenance of ecological balance and sustainable development.

4.1.2. Value Addressed in Yoshinogari Historical Park, Japan

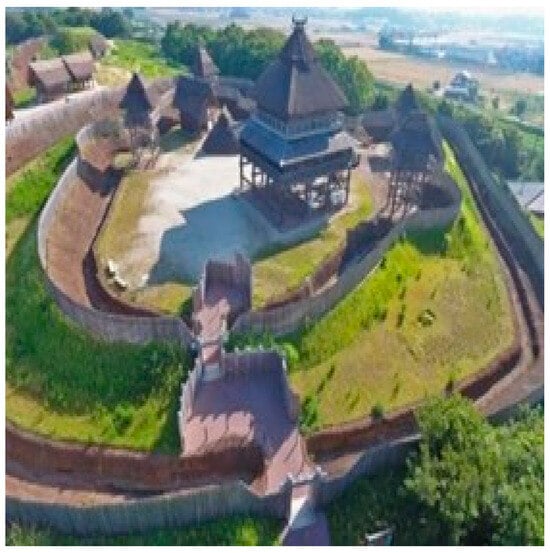

The Yoshinogari site is a large-scale ring-trench settlement site from the Yayoi period (a long period of 700 years) in Japan. It is of great cultural, historical, and social value as it reveals the beginnings of the early primitive state of Japan [68]. Yoshinogari Historical Park is a national park of monumental significance that was built for the preservation and active use of archaeological sites. It preserves the surrounding rich natural environment and the site as a whole, respecting the role of these archaeological sites and historical places in contemporary society. It also builds a space that the public can easily use to promote public understanding of the site’s culture and recognition of its value. Yoshinogari Park has become a significant place for promoting national culture and a stronghold for transmitting cultural information from Japan to the world by creating an overall landscape with the atmosphere of the Yayoi era, as shown in Figure 1 and Figure 2.

Figure 1.

Yoshinogari site. Source: the Yoshinogari Historical Park’s official website (https://www.yoshinogari.jp).

Figure 2.

Key-shaped entrance of Kitanaikaku. Source: the Yoshinogari Historical Park’s official website (https://www.yoshinogari.jp).

4.1.3. Value Addressed in Daming Palace National Heritage Park, China

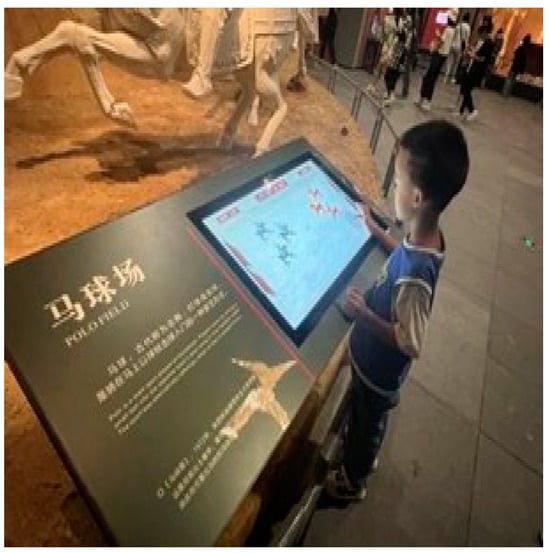

The Daming Palace National Heritage Park is the most representative palace site of the Tang dynasty. It also has significant cultural, historical, and social value. It is grand in scale and complete in structure. It was the political, cultural, and economic center of the Tang dynasty for more than 200 years and had great cultural and historical value [69]. Daming Palace National Heritage Park is one of the earliest archaeological site parks built in China. It adheres to the principles of archaeological research as the basis and site protection and presentation as the main body. It protects all the material elements related to the site value, landscape, environment, and potential site area in a holistic and flexible way. This protection method based on authenticity and integrity improves the environment inside and outside the site area, resolves the contradiction between site protection and urban development, and simultaneously provides the public with an educated, open-air public cultural space. (Figure 3 and Figure 4).

Figure 3.

Tourists learn about Daming Palace’s history. Source: the Daming Palace National Heritage Park’s official website (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Daming_Palace).

Figure 4.

Immersive tour experience. Source: the Daming Palace National Heritage Park’s official website (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Daming_Palace).

4.2. Heritage Tourism Activities Arranged by the Three Parks

4.2.1. Heritage Tourism Activities in Chaco Culture National Historical Park, US

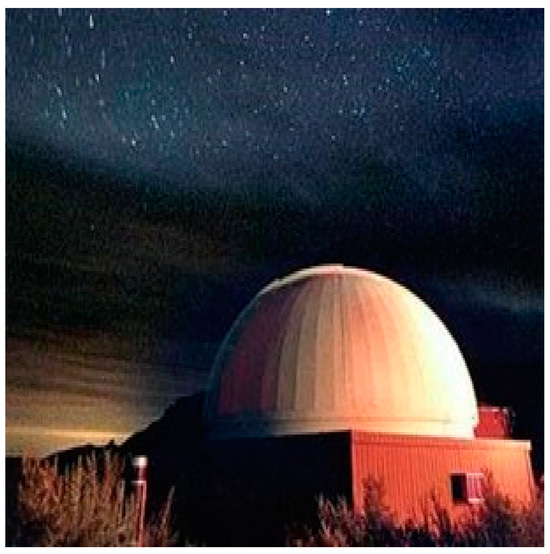

The Chaco Culture Park aims to enhance public understanding of Chaco’s rich history and cultural heritage through various educational and recreational activities tailored to the park’s unique setting. Through immersive experiences, such as guided field trips and ranger-led programs, visitors, especially younger generations, can actively engage with the historical and natural treasures of the region. The park offers a network of trails and bike paths that allow visitors to explore numerous Chaco sites while experiencing the area’s diverse wildlife and serene environment. Camping facilities provide opportunities for rugged outdoor experiences amidst petroglyphs, cliff dwellings, and stunning desert landscapes.

Furthermore, as an International Night Sky Park, Chaco Culture Park collaborates with the International Astronomical Union to establish light control zones, preserving the pristine night sky for stargazing enthusiasts. This initiative allows visitors to marvel at the same celestial wonders observed by the Chaco people thousands of years ago and safeguards the nocturnal ecosystem and surrounding natural environment.

During the guided tours, volunteers and guides prioritize environmental conservation and encourage responsible visitor behavior while sharing insights into the park’s historic structures and cultural landscapes. This integrated approach ensures that visitors not only gain knowledge but also develop a deeper appreciation for Chaco’s cultural and natural heritage while contributing to its preservation, as shown in Figure 5 and Figure 6.

Figure 5.

Chaco great house at night. Source: the Chaco Culture National Historical Park’s official website (https://www.nps.gov/chcu/index.htm).

Figure 6.

Chaco Observatory. Source: the Chaco Culture National Historical Park’s official website (https://www.nps.gov/chcu/index.htm).

4.2.2. Heritage Tourism Activities in Yoshinogari Historical Park, Japan

The Yoshinogari Historical Park has been meticulously designed to blend the natural splendor of its surroundings with heritage tourism development, creating an immersive environment that accurately portrays the Yayoi era. Through careful zoning and preservation efforts, the park successfully recreates scenes from the past, offering visitors a glimpse into ancient life.

Utilizing scientific planning, the park presents interactive displays and activities that allow guests to engage with and understand the Yayoi people’s way of life. Activities such as crafting earthen flutes, wood drilling for firemaking and constructing kokutama enhance visitors’ understanding and appreciation of the era while immersing them in its ambiance. Staff dressed in Yayoi-era attire further enhance the authenticity of the experience, providing guidance and support throughout visitors’ participation.

Moreover, Yoshinogari Historical Park boasts excellent recreational amenities, including an experience hall, a lawn plaza, and an amusement park, catering to the needs of the public. As a result, the park has evolved into a hub for disseminating Japanese history and culture. Its cultural ambiance, distinct architecture, and open spaces exemplify the commitment to sustainable development, benefiting the archaeological site, the local community, and heritage tourism initiatives within the park, as shown in Figure 7 and Figure 8.

Figure 7.

Recreation space. Source: the Yoshinogari Historical Park’s official website (https://www.yoshinogari.jp).

Figure 8.

Great Yayoi field. Source: the Yoshinogari Historical Park’s official website (https://www.yoshinogari.jp).

4.2.3. Heritage Tourism Activities in Daming Palace National Heritage Park, China

The Daming Palace National Heritage Park boasts rich historical and cultural significance, albeit with limited natural resources. To enhance its appeal and functionality, the park underwent a regeneration process focused on restoring its environment and landscape. This transformation involved constructing green spaces and planting trees, thereby creating an open and lush setting that harmonizes humanistic and natural ecology. This approach beautified the park and catalyzed cultural and tourism development.

Additionally, the Daming Palace Ruins Museum plays a pivotal role in educating visitors about the site’s history and value through innovative digital interpretation and displays. It offers various activities, such as relic restoration, archaeological site simulations, and the Tang costume experiences, to cater to diverse interests and needs, including scientific research, education, and recreation. Moreover, a digital technology experience center within the park hosts immersive cultural activities, such as film screenings, theatrical performances, and traditional song recitals, allowing visitors to delve deeper into the rich cultural heritage of the Daming Palace.

Furthermore, the park collaborates with the local community to organize vibrant performances and shows reminiscent of the Tang dynasty and folk culture. These events entertain and serve as a platform for fostering community engagement and appreciation for environmental conservation and heritage preservation. By involving local residents in the protection and management of the site, the park aims to instill a sense of ownership and pride while ensuring its long-term sustainability.

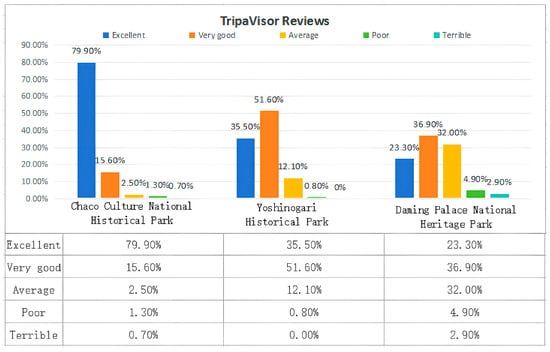

4.3. Public Perceptions of the Three Archaeological Site Parks

To understand the public’s experience and perceptions after visiting the archaeological site parks, the authors read the public reviews of the three archaeological site parks on TripAdvisor and analyzed the public perceptions using KH-CODER software. These three parks have received positive public feedback. The public experience at Chaco Culture National Historical Park in the United States was 95.5 percent positive, with 79.9 percent excellent and 15.6 percent very good. In comparison, Yoshinogari National Historical Park in Japan was 87.1 percent positive, with 35.5 percent excellent and 51.6 percent very good. At Daming Palace National Heritage Park in China, it was over 60 percent excellent and very good (Figure 9). The analysis and research reveal that in the archaeological parks of the three countries, domestic tourists form the majority of visitors, and there is a common demand for recreational and educational functions. However, differences in visitor types also lead to varying public perception tendencies. Chaco Culture National Historical Park, as an International Night Sky Park, attracts a significant number of international visitors. Daming Palace National Heritage Park in China mainly draws local residents, with its large free areas serving as a logical urban leisure space. In Japan, Yoshinogari National Historical Park has a high proportion of family tours thanks to its emphasis on heritage education and the organization of family-oriented activities. Overall, visitors felt that their visit experience was worthwhile. The successful archaeological site parks of the three countries could learn from each other concerning sustainable management activities to improve management capacity.

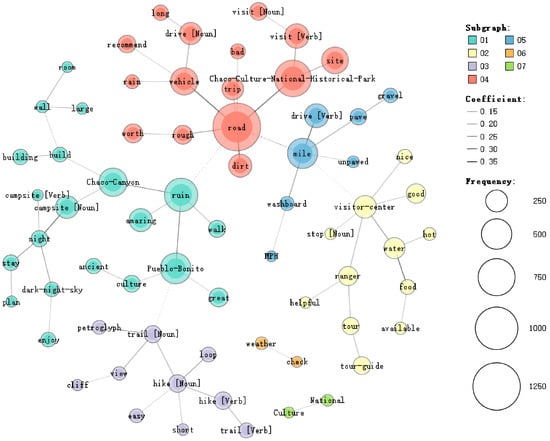

Figure 10.

Chaco Culture National Historical Park’s collinear network diagram.

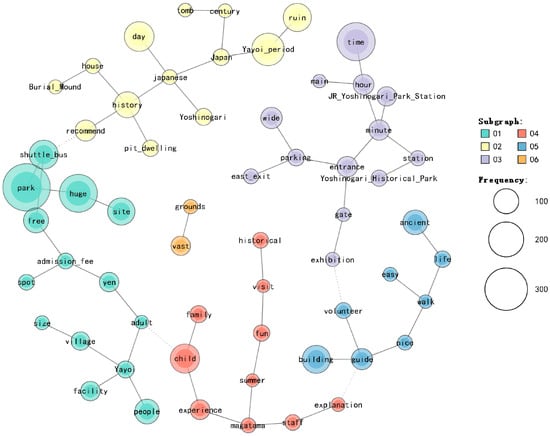

Figure 11.

Yoshinogari Historical Park’s collinear network diagram.

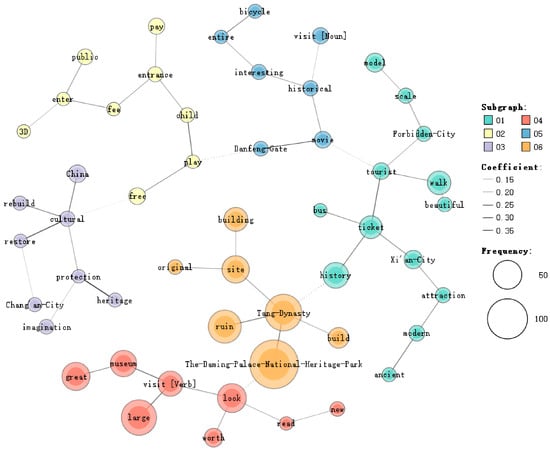

Figure 12.

Daming Palace National Heritage Park’s collinear network diagram.

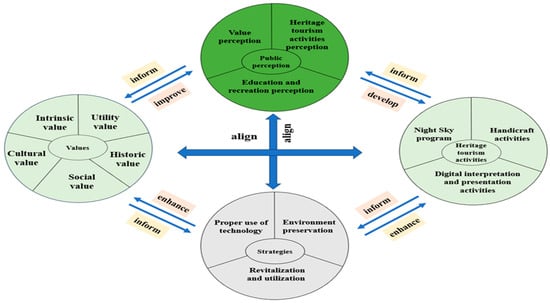

Figure 13.

Framework for the sustainable management of archaeological site parks.

To enhance the comparative analysis of the three archaeological site parks, the authors also followed public mixed perceptions through co-occurrence network analysis of Chaco Culture National Historical Park, Yoshinogari Historical Park, and Daming Palace National Heritage Park. At the same time, by comparing the public perception of the three national parks, it can be seen that cultural differences among different countries also affect the public’s perception of archaeological site parks. Understanding these key factors is important for improving sustainable management. For example, historical awareness, cultural values, social customs, and economic and political backgrounds, as well as media promotion, all serve important roles. Understanding these differences can help better manage and promote archaeological site parks and facilitate cultural exchange.

4.3.1. Public Perceptions in Chaco Culture National Historical Park, US

In terms of value perception, with Chaco Culture National Historical Park as the core, the building and wall of the park are considered by tourists to be large enough to show and reflect the culture of the time. Visitors think these sites are ancient and impressive and enjoy their time there. Nevertheless, the poor road conditions also made them feel the inadequacies of the journey.

In terms of heritage tourism activity perceptions, the terms associated with the roads are “gravel”, “bad”, and “dirty”, indicating that visitors perceive the Chaco as less accessible and convenient. Therefore, most tourists choose to drive to the scenic spot, that is, visit and stay to facilitate the tour. It shows that the level of service the infrastructure provides needs to be improved, and the traffic may become a factor limiting the arrival of tourists. When entering the park, it is recommended to hike along its elaborate loop for a personal experience of the cultural heritage. However, it should be considered whether hiking is suitable for all ages and whether different tour routes should be designed according to different age groups. In addition, tourists believe that the explanation of Chaco Culture National Historical Park is indispensable. With a private tour guide or a complimentary explanation by the ranger, tourists can gain a deep understanding of Chaco’s history and culture, improving visitors’ experience.

In terms of education and recreation perception function perception, the night sky activity as a unique experience has been widely loved and paid attention to by everyone. The night sky experience in the park’s Pueblo Bonito, ruin, and Chaco Canyon is a great attraction for visitors. Visitors are willing to spend time here camping and have a night watching the stars, enjoying a series of night sky-themed activities.

4.3.2. Public Perceptions in Yoshinogari Historical Park, Japan

In terms of value perception, with the “park” as the core, connecting “huge”, “site”, “ruins”, “history”, “century”, “vast grounds”, etc., visitors understand that Yoshinori is a large-scale ancient site from the Yayoi period to the present and have a strong perception of its cultural and historical value. Based on the terms “burial mound”, “house”, “rice”, “tomb”, “Yayoi period”, and “Japan”, visitors learn about the history of the ancient Japanese people in Kyushu by visiting pit houses and tombs that recreate the living environment of the Yayoi period. It shows the characteristics of the Yayoi period of Japan and promotes the Japanese national culture.

In terms of heritage tourism activity perceptions, with “time” as the core, tourists generally drive to Yoshinori, believing the park’s parking lot is spacious and convenient. The park has a general admission fee, with complimentary admission on certain days and events. With clear signs in the park, it is recommended that tourists utilize the free buses in Yoshinori Park. The bus route connects various facilities in the park. In addition, visitors commented highly on the park’s volunteers, guides, and explanation services. On the park roads, the signs are uniformly designed through the image of the mascot, which makes the image of the character IP more profound.

In terms of education and recreation perception function perception, with “child” as the core, the related words are “magatama”, “facilities”, and “Spot”, indicating activities in Yoshino life museum, especially the production of gougatama, are very popular with children and families. Enthusiastic staff and volunteers teach visitors how to make magatama. It is a good place for children to learn history and culture and play happily. In addition, Yoshinori Historical Park has Yayoi Great Field and ancient Plant Hall, a place for public participation and experience activities in the park occasionally, especially in the summer. Visitors consider Yoshinori suitable for families to take children to play, but they should be careful to repel mosquitoes and avoid the heat.

4.3.3. Public Perceptions in Daming Palace National Heritage Park, China

In terms of value perception, the Daming Palace National Heritage Park is the core connection point, and its closely related words include Tang dynasty, which is mentioned up to 83 times, “history”, “museum”, “ruin”, and “site”. It shows that tourists clearly understand the historical and cultural value of Daming Palace through sightseeing. The associated adjectives are “great”, “beautiful”, and “worth”, which are complimentary to the archaeological site park. Daming Palace combines history and culture with modern life, attracting tourists to learn and carry forward traditional culture.

Regarding heritage tourism activity perceptions, Daming Palace has high traffic accessibility. When entering the park to visit, the pedestrian road and bus are combined to facilitate visitors in planning the tour time and route reasonably. The park is composed of areas of complimentary entry and tolled entry. The restored buildings and sites in the park and the free cultural relics protection display area are important resources to attract the public. While the 3D film display showing the history of Daming Palace has attracted more attention from the public, children are more willing to play in the science and technology interactive area. The public’s overall impression of the park’s basic services, such as “service center” and “tour guide” is relatively low.

In terms of education and recreation perception function perception, the public uses “ancient” and “modern” to describe the building, ruin, and Danfeng Gate of Daming Palace National Heritage Park, which shows the combination of ancient architecture and modern technology. Through the combination of ancient architecture and modern technology, the public has a higher perception of the palace complex, the site display area, and the unique historical pattern within the park. Modern technologies are employed in Daming Palace National Heritage Park, providing visitors with an immersive experience of the ancient Tang civilization through on-site reconstruction.

4.4. Summary

Despite their different development histories, heritage characteristics, and management approaches, all three cases emphasize sustainable management and show common features in terms of sustainable social, cultural, and environmental development. Considering the above-discussed results and analysis, the key elements for sustainable management drawn from the archaeological site parks practice in the United States, Japan, and China are discussed in Section 5.

5. Discussion

The decision of the three countries to preserve the past through their parks and make them available for public enjoyment in the present constitutes a socio-ethical and cultural choice that contributes more broadly to the achievement of sustainable development goals. Their approach to sustainable management informs the cultural practices of other fragile natural or cultural archaeological sites. Overall, values and culture are the core concepts and components of archaeological sites. The sustainable preservation of archaeological remains with an emphasis on authenticity and integrity is a crucial operation and the most critical aspect of managing such sites. Another key factor for the success of archaeological site parks is the focus on visitor experience perception. The management of archaeological site parks is responsible for ensuring that visitors have satisfying and enjoyable experiences, considering accessibility, comprehensibility, and sustainability.

5.1. Principle Elements of Archaeological Site Park Sustainable Management

Our findings suggest that the sustainable management concepts of these three archaeological site parks share common features despite their historical backgrounds and different social development needs. The case studies in the three parks resulted in the identification of three key elements and strategies to manage archeological parks.

5.1.1. Deeper Understanding of the Intrinsic and Utility Values of the Archaeological Site Parks Is a Key Element for Sustainable Management

The vitality of these three archaeological site parks comes from their ability to make lasting contributions to contemporary and future societies. On the basis of the scientific protection of archaeological sites, park managers have thoroughly analyzed the suitability of the values of the sites to the development needs of contemporary and future societies. The management practices have closely linked archaeological sites to sustainable development through their values. By doing so, archaeological sites are not isolated, static, and purely historical concepts. Therefore, while paying attention to the historical, cultural, and social value of archaeological site parks, it is also necessary to focus on their intrinsic and practical value to better carry out heritage tourism activities and improve the perception of the public. It is necessary to establish scientific sustainable management objectives that extract the understanding of the values and characteristics of individual archaeological sites in order to develop tourism activities, linking them to contemporary social development.

5.1.2. Development of Heritage Tourism Activities Is the Strategic Focus of Sustainable Management

The three archaeological site parks have a well-established model for developing heritage tourism. They have nourished sustainable tourism by considering archaeological sites, surrounding communities, natural resources, and other elements that can create tourism space in an integrated manner. Meanwhile, the three parks also promote sustainable management through diverse heritage tourism activities, such as night sky activities, handicraft activities, and digital interpretation and presentation activities. These heritage tourism activities have established an organic connection between the archaeological site parks and the public.

5.1.3. Considering Public Perception Is Another Key Principle of Sustainable Management

Public perception reflects visitors’ overall experience of archaeological site parks and directly provides feedback on the parks’ performance regarding functionality and services. The functional dimension can be assessed by analyzing visitor comments, including the infrastructure, educational activities, recreational experiences, and management services. For example, visitors’ evaluations of transportation convenience, facility completeness, and activity diversity directly impact the parks’ effectiveness in their functional design and operational management. Within the framework of sustainable management, the role of the functional dimension is crucial. It affects visitors’ satisfaction and willingness to revisit while providing clear directions for improvement to park managers. Therefore, park managers should consider the functional dimension an essential tool for assessing and optimizing management practices. By continuously improving infrastructure and service quality, the overall visitor experience can be enhanced, promoting archaeological site parks’ sustainable development. In summary, enhancing the sustainable management of archaeological site parks through public perception is a very important principle.

5.2. Strategies of Archaeological Site Parks’ Sustainable Management

5.2.1. Environmental Preservation to Improve Public Perception

This strategy is derived from analyzing public perceptions of the Chaco Culture National Historical Park case, where the dark night environment is considered a valuable and essential natural resource. Where possible, ensure that qualified and well-recognized international experts in the relevant fields assist in implementing dark sky projects for the effective conservation of natural habitats, public environmental education, and the promotion of astrotourism. The results of the Chaco case study bear this out.

The concept of darkness as a guide and providing recreational experiences for visitors under the stars at night is a course of action for the sustainable management of archaeological site parks. Park management works with a variety of agencies to take full advantage of the environment and resources of archaeological site parks to plan dark night-themed events. These activities, including camping, hiking, photography, music, painting, astronomical interpretation, social media interaction, and other activities, provide the public with a sustainable recreation system and educational opportunities while achieving environmental protection.

5.2.2. Public Participation Activities to Promote the Revitalization and Utilization of the Site

From the analysis of the public perception of the Yoshinogari Historical Park case, we learned the value of promoting the revitalization and utilization of sites and designing highly participatory and interactive activities. These activities are conducive to protecting and promoting the diversity of cultural expressions of archaeological sites and meeting the differentiated and diversified cultural needs of the public. However, they also enable the public to engage at a deeper level of tolerance and dialog with site culture. For example, Yoshinogari Park held a series of handcraft experience activities, such as hook jade making and mascot-related thematic activities, which enabled the public to acquire knowledge and understand history through experience and interaction and achieved the purpose of teaching and having fun. Public participation activities bring the cultural content of history into contemporary life and are a continuation and extension of the site’s values and functions.

5.2.3. Proper Use of Technologies to Improve Public Appreciation and Understanding

The analysis of the Daming Palace National Heritage Park case shows that using digital technologies can activate the rich cultural connotations of archaeological sites. The immersive experience enabled by technology has prompted the public to shift their focus from the physical form of the site to understanding the spirit of the site and discovering its value in contemporary society. This has enhanced the cultural resilience of archaeological sites in the midst of change. Using technologies can make the public feel the authenticity and integrity of the archaeological site and promote the development of the archaeological site from a “momentary” cultural attraction to a public cultural space with an “eternal” cultural contagion, which is conducive to the sustainable management of archaeological site parks. However, while acknowledging the use of digital technology, it is also necessary to reflect on the relationship between digital technology and archaeological sites to better realize “the presentation of the past, the identity of the place, and the education of the future”.

5.2.4. Effective Management Entities Are Responsible for Implementing Governance

Implementing effective governance of archaeological site parks is crucial for promoting the environment, public participation, and the use of technological means. Firstly, it is essential for a comprehensive management plan to balance tourists’ needs and the site’s protection. Community participation is to be encouraged to enhance cultural identity and foster a sense of responsibility. Educational research can raise public awareness of site values. Secondly, clarifying the legal framework and securing financial support is important. This can be achieved by establishing an effective legal enforcement system, ensuring that governance has a legal basis. Funds can thus be raised through diversified means, prioritizing protection and maintenance and promoting sustainable management. Furthermore, consistency in implementing governance needs to be maintained, regardless of the type of management entity. Different countries have different management entities and institutions implementing strategies: some are national institutions, some are private institutions, and some are mixed governance.

5.3. Proposed Framework of Archaeological Site Park Sustainable Management

By integrating the principle elements and implementation proposals for these strategies, a framework for the sustainable management of archaeological site parks based on public perception and taking into account values and heritage tourism activities was developed, focusing on the economic sustainability of archaeological site parks, as shown in Figure 13.

Intrinsic value, denoting the inherent worth and significance of archaeological sites rooted in their cultural, historical, and aesthetic dimensions, forms the bedrock of heritage preservation efforts. Archaeological site parks, serving as custodians of cultural heritage and historical narratives, embody intrinsic value that transcends utilitarian considerations, underpinning their importance as repositories of tangible and intangible heritage. Safeguarding this intrinsic value is paramount for ensuring the authenticity, integrity, and enduring relevance of archaeological sites as invaluable cultural assets that embody the collective memory and identity of societies. This cross-case analysis demonstrates that archeological parks hold intrinsic value in urban settings that transcend mere utility considerations, embodying a multitude of benefits that extend beyond their functional purpose. In addition to the protection function, archeological parks serve as dynamic spaces that contribute significantly to the socio-cultural, environmental, and economic fabric of cities. To fully realize the intrinsic values of the sites, it is essential to understand and extend the utility values of the archeological parks, whether it is to provide a platform for social interactions and recreational pursuits (as at Yoshinogari Historical Park), offer a range of ecosystem services that bolster ecological resilience (as at Chaco Culture National Historical Park), or enhance property values, attracting investment, and stimulating local economic activity (as at Daming Palace National Heritage Park). Thus, the values of the sites serve as the fundamental starting point for sustainable management.

The nexus between intrinsic values and heritage tourism activities within the realm of archaeological site park management is a nuanced and critical relationship. Heritage tourism activities, as integral components of archaeological site park management, wield considerable influence on the preservation and presentation of intrinsic value within these sites. The design of tourism activities within archaeological site parks necessitates a nuanced approach that considers both the intrinsic and utility values of these heritage sites. By intertwining these dimensions, tourism activity design can effectively balance the preservation of the sites’ intrinsic value with the facilitation of visitor experiences and the promotion of sustainable tourism practices. All three case studies demonstrate the preservation of this intrinsic value is paramount for safeguarding the cultural significance and authenticity of archaeological sites, ensuring their enduring relevance and resonance with visitors. Utility value, on the other hand, pertains to the functional and practical benefits that visitors derive from their experiences within archaeological site parks. This includes factors such as recreational opportunities, educational resources, interpretive facilities, visitor amenities, and economic contributions to local communities. The utility value of archaeological site parks encompasses the tangible benefits that visitors obtain from their visits, ranging from leisure and intellectual enrichment to economic stimulation and community development.

As shown in the framework, in the design of heritage tourism activities within archaeological site parks, it is hence essential to strike a delicate balance between preserving the intrinsic value of the sites and optimizing their utility value to enhance visitor experiences and support sustainable tourism practices. Key strategies for integrating intrinsic and utility values in tourism activity design were extracted from this cross-case analysis: environment preservation, revitalization, and utilization, and using technologies. Implementing environment preservation that prioritizes the conservation of archaeological sites and minimizes environmental impacts, such as the dark sky program at Chaco Culture National Historical Park, can ensure tourism activities align with preserving the intrinsic value of the park. Similarly, diverse heritage tourism activities should be designed, such as incorporating handicraft activities, cultural events, performances, and workshops that celebrate the heritage and traditions associated with archaeological sites, enriching visitor experiences and fostering a deeper appreciation of the intrinsic value of these cultural treasures. The restoration of cultural relics and kite-making workshops at Yoshingari Historical Park demonstrate the link between heritage tourism activities and intrinsic values. The development of technologies, especially digital interpretation and presentation activities and immerse technologies, such as virtual reality, provides an innovative way for visitors to explore ancient ruins and historical landscapes, get a sense of how the sites might have looked in their original state, or have an interactive learning experience in a dynamic and engaging way. Technology can transport visitors back in time to experience key historical moments or events that took place at the archaeological site. All three case studies provide solid evidence of the advantages of using technology for tourism activity design.

The critical item of the framework is the consideration of public perception. The findings suggest that public perception is a valuable tool for evaluating the alignment of tourism activities with the intrinsic value of archaeological site parks. The information on public perception is available via major trustworthy websites, and hence, low in cost for data collection. The real-time response of public perception can provide suggestions for perfecting existing activities and creating new activities. Public perception, including visitor feedback and review, when analyzed appropriately, can provide valuable insights and identify opportunities for enhancement. Hence, by leveraging public perception as a tool for evaluating the alignment of tourism activities with the intrinsic and utility values of archaeological site parks, archeological parks can use a combination of different strategies to ensure that visitor experiences are meaningful, educational, and respectful of the site’s cultural and historical importance.

In the framework of sustainable management, efforts are also made to present the connection between public perception and management decisions. The public’s perception, attitude, and behavior toward heritage parks can affect management decisions, which, in turn, influence the public’s experience. Public participation can promote scientific decision-making, provide diversified perspectives for management decision-making, help managers have a more comprehensive understanding of public needs and perceptions, and formulate more scientific policies. Therefore, we recommend timely responses to public comments; adopting rational suggestions; encouraging public participation in the protection, interpretation, and supervision of the heritage parks; developing more comment platforms; designing scientific survey questionnaires, etc.; and creating a collaborative and shared atmosphere.

It is challenging to evaluate the alliances and effects of the activities. Using public perception, the effectiveness of the service and the park management provided can thus be evaluated. Also, the real-time response of public perception can provide suggestions for perfecting existing activities and creating new activities. Taken as a whole, the archaeological site park is a complex, complete, and integrated system with many dynamic and combinable subsystems. Each subsystem can be managed with different methods, tools, meanings, and multidimensionality in order to maintain sustainability and, at the same time, continuity and consistency throughout the park and focus on aspects that are essential for the long-term management of the archaeological site parks.

6. Conclusions

By applying cross-case study methods, this study analyzes the historical, cultural, and social values, heritage tourism activities and sustainable management practices, and public comments of three representative archaeological site parks from the United States, Japan, and China that are conducive to achieving the goals of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. It proposes a set of strategies to promote their sustainable management in the context of sustainable development. Despite the different site qualities and cultural contexts of the three cases, this paper provides, through synthesis and comparison, a conceptual framework capable of observing how archaeological site parks can be managed sustainably.

The proposed framework balances the comprehensive value of the economy, society, and culture [3], highlights the interplay between the protection and utilization of archaeological site parks, and increases investment through diversified funding sources. It can help control costs effectively through budget management, resource sharing, and technology application. Economic benefits can be enhanced through heritage tourism development, cultural and creative industry development, and educational research activities. The management strategy of archaeological site parks can be adjusted in combination with community participation and benefit sharing [50], sustainable development [37], international cooperation [35], risk management [5], and other policies, achieving a win-win situation between cultural heritage protection and economic benefits.

The main conclusions of this paper are as follows: The system of archaeological site parks is considered one of the best forms of management that balances the conservation and use of natural and cultural heritage. Its cultural richness and sustainable management provide new knowledge and insights for the promotion of cultural diversity, the general well-being of the public, and the sustainable development of societies. Based on the detailed study of three cases, this research identifies important elements, key principles, and strategic priorities for sustainable management. A framework to manage archeological site parks sustainably is proposed accordingly.

This sustainable management framework and strategies for archaeological site parks can be upgraded and implemented at archaeological sites around the globe, as the sustainable management framework provides the foundation and guarantee for sustainable development. The findings of this paper provide the following practical insights into the sustainable management of archaeological site parks. Firstly, the strategies are a review and reflection on the implementation of sustainable management practices in archaeological site parks, as well as an integration of the existing theoretical and knowledge base, and it is expected that these strategies will provide useful references for the research and practical management of archaeological site parks. Secondly, this paper focuses on sustainable heritage tourism and finds that heritage management practices embedded in cultural landscapes can provide positive opportunities for heritage tourism activities in archaeological site parks, which is in line with the World Heritage Convention’s objectives for practical development. Again, the sustainable development of cultural heritage is a global concern that affects all humanity. These cases involve cultural heritage of universally outstanding value, whose positive, dynamic, and reflexive adaptations to global change provide useful insights into sustainable management and whose outcomes can inform and inspire each other to promote the cultural diversity and sustainable development of cultural heritage globally.

There are limitations to this study. It uses a multiple case study approach, and the theoretical generalization of the resulting ideas and conclusions may be somewhat limited. The analysis of public perception in this study primarily relies on online review data, which are subject to self-selection bias, and the representativeness of the online review sample has not been systematically verified. This limits the comprehensiveness of the results. Future research will expand the sample size, collect more online and offline comments, and combine them with tourist classification to gain a deeper understanding of the factors and behaviors that affect tourist perception. Moreover, this paper uses large-scale archaeological site parks in three countries as a cross-case study endowed with significant values and whose management in their respective countries has a higher priority than other heritage sites. Therefore, the feasibility of sustainable management measures for archaeological site parks of different site types and local scales needs to be further explored. While this study has proposed strategies for sustainable management, the associated economic strategies have not yet been fully developed, and the proposed strategies need to be further validated. Therefore, there are several possible future research directions, such as an in-depth study of each of the implementation proposals for these strategies, with a focus on the economic sustainability of archaeological site parks and sustainability impact assessment.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.X.; methodology, T.L. and F.J.Y.; software, Y.H. and S.L.; validation, Y.X., T.L. and F.J.Y.; formal analysis, Y.W.; investigation, Y.X.; resources, Y.X.; data curation, Y.X.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.X. and Y.W.; writing—review and editing, T.L., F.J.Y. and P.Z.; visualization, Y.X.; supervision, F.J.Y.; project administration, Y.X.; funding acquisition, Y.X. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Social Science Foundation Project of China (Fund project host: Yueting Xi), grant number 19BKG047.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, FY, upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the editors and anonymous reviewers for their valuable time and effort in reviewing this manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Ebejer, J.; Staniewska, A.; Srodulska-Wielgus, J.; Wielgus, K. Values as a base for the viable adaptive reuse of fortified heritage in urban contexts. Muzeol. A Kult. Dedicstvo-Museol. Cult. Herit. 2023, 11, 41–72. [Google Scholar]

- Bucher, B.; Kolbitsch, A. Coming to Terms with Value: Heritage Policy in Vienna. Herit. Soc. 2019, 12, 41–56. [Google Scholar]

- Kubontubuh, C.P.; Martokusumo, W. Meeting the past in the present: Authenticity and cultural values in heritage conservation at the fourteenth-century Majapahit heritage site in Trowulan, Indonesia. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2020, 26, 469–479. [Google Scholar]

- ICOMOS. 2015. Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/en/news/1256 (accessed on 18 February 2025).

- Salalah Guidelines for the Management of Public Archaeological Sites. Available online: https://www.icomos.org/images/DOCUMENTS/Charters/GA2017_6-3-3_SalalahGuidelines_EN_adopted-15122017.pdf (accessed on 18 February 2024).

- Abdelkader, A. Archaeological Sites’ Management, Interpretation, and Tourism Development—A Success Story and Future Challenges: The Case of Bibracte, France. Heritage 2021, 4, 2261–2277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pranskūnienė, R.; Zabulionienė, E. Towards heritage transformation perspectives. Sustainability 2023, 15, 6135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasoolimanesh, S.M.; Jaafar, M.; Ahmad, A.G.; Barghi, R. Community participation in World Heritage Site conservation and tourism development. Tour. Manag. 2017, 58, 142–153. [Google Scholar]

- Eman, H.; Cooper, C. An assessment of sustainable tourism planning for the archaeological heritage: The case of Egypt. J. Sustain. Tour. 2002, 10, 514–535. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Y.; Rollo, J.; Esteban, Y.; Tong, H.; Yin, X. Develop a comprehensive assessment model of social value with respect to heritage value for sustainable heritage management. Sustainability 2021, 13, 13373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.-Y.; Li, Y.-Q.; Ruan, W.-Q.; Zhang, S.-N.; Li, R. Influencing factors and formation process of cultural inheritance-based innovation at heritage tourism destinations. Tour. Manag. 2024, 100, 104799. [Google Scholar]

- Mousazadeh, H.; Ghorbani, A.; Azadi, H.; Almani, F.A.; Zangiabadi, A.; Zhu, K.; Dávid, L.D. Develop sustainable behaviors for underground heritage tourism management: The case of Persian Qanats, a UNESCO world heritage property. Land 2023, 12, 808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janianton, D.; Yusuf, M. Effects of perceived value, expectation, visitor management, and visitor satisfaction on revisit intention to Borobudur Temple, Indonesia. J. Herit. Tour. 2022, 17, 174–189. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J.; Zhao, X.; Wang, H.; Yan, J.; Yang, D.; Xie, K. Portraying heritage corridor dynamics and cultivating conservation strategies based on environment spatial model: An integration of multi-source data and image semantic segmentation. Herit. Sci. 2024, 12, 419. [Google Scholar]

- Yunming, K.; Lin, B. Public participation and city sustainability: Evidence from Urban Garbage Classification in China. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2021, 67, 102741. [Google Scholar]

- Tao, Y.H.; Lin, P.H. Analyses of Sustainable Development of Cultural and Creative Parks: A Pilot Study Based on the Approach of CiteSpace Knowledge Mapping. Sustainability 2023, 15, 10489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alazaizeh, M.M.; Hallo, J.C.; Backman, S.J.; Norman, W.C.; Vogel, M.A. Value orientations and heritage tourism management at Petra Archaeological Park, Jordan. Tour. Manag. 2016, 57, 149–158. [Google Scholar]

- Timothy, D. Ancient Monuments in the Countryside: An Archaeological Management Review; English Heritage Publishing: Swindon, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Timothy, D.J. Cultural Heritage and Tourism: An Introduction; Channel View Publications: Bristol, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Timothy, D.J.; Boyd, S.W. Heritage Tourism; Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Howard, P.F. Heritage: Management, Interpretation, Identity; A&C Black: London, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Gallaga, E.; Trujillo, J.; Andrlic, B. Archaeological Attractions Marketing: Some Current Thoughts on Heritage Tourism in Mexico. Heritage 2022, 5, 567–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fafouti, A.E.; Vythoulka, A.; Delegou, E.T.; Farmakidis, N.; Ioannou, M.; Perellis, K.; Moropoulou, A. Designing Cultural Routes as a Tool of Responsible Tourism and Sustainable Local Development in Isolated and Less Developed Islands: The Case of Symi Island in Greece. Land 2023, 12, 1590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alazaizeh, M.M.; Ababneh, A.; Jamaliah, M.M. Preservation vs. use: Understanding tourism stakeholders’ value perceptions toward Petra Archaeological Park. J. Tour. Cult. Change 2020, 18, 252–266. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, Q. Archaeological Tourism, World Heritage and Social Value: A Comparative Study in China. Herit. Soc. 2023, 16, 157–181. [Google Scholar]

- Timothy, D.J. Making sense of heritage tourism: Research trends in a maturing field of study. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2017, 25, 177–180. [Google Scholar]

- Boniface, B.; Cooper, C. The Geography of Travel and Tourism; Heinemann Ltd.: London, UK, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Hassan, T.H.; Almakhayitah, M.Y.; Saleh, M.I. Sustainable Stewardship of Egypt’s Iconic Heritage Sites: Balancing Heritage Preservation, Visitors’ Well-Being, and Environmental Responsibility. Heritage 2024, 7, 737–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Assaf, A.; Albalawneh, A.; Majdalawi, M.; Nowar, L.A.; Kabariti, R.; Hjazin, A.; Aljaafreh, S.; Hammour, W.A.; Diab, M.; Haddad, N. Local Communities’ Willingness to Accept Compensation for Sustainable Ecosystem Management in Wadi Araba, South Jordan. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeremy, H. The Roman Street: Urban Life and Society in Pompeii, Herculaneum, and Rome; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Ursula, T.-S.; Richard, L.B.; Salazar, L.C. (Eds.) Machu Picchu. Unveiling the Mystery of the Incas; Yale University Press: London, UK, 2005; Volume 100, pp. 590–591. [Google Scholar]

- Arthur, W. The Great Wall of China: From History to Myth; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Harold, K. Destruction, mitigation, and reconciliation of cultural heritage. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2017, 23, 538–555. [Google Scholar]

- Muhammed, M.; Boussaa, D. Cultural heritage tourism as a catalyst for sustainable development; the case of old Oyo town in Nigeria. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2023, 29, 21–38. [Google Scholar]

- Participative Co-Creation of Archaeological Heritage: Case Insights on Creative Tourism in Alentejo, Portugal. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0160738319301471 (accessed on 18 February 2025).