Abstract

Addressing the urban–rural income disparity and fostering coordinated urban–rural development pose critical challenges for China in pursuit of its common prosperity strategy during its new phase of development. Regional integration emerges as a pivotal policy tool, which is extensively utilized to facilitate regional development coordination and significantly contributing to overall regional economic growth. This study delves into whether the implementation of regional integration policies generates a common prosperity effect, thereby reducing the disparity in income levels between urban and rural regions. Utilizing city-level panel data spanning from 2000 to 2019 within the Yangtze River Delta region, we treat the expansion of regional integration as a quasi-natural experiment and employ a time-varying Difference-in-Differences model to identify the integration’s common prosperity effect. Furthermore, we leverage mediation effect models to unravel the mechanisms through which integration influences the urban–rural divide in income. Our findings reveal that the expansion of integrated regions contributes to narrowing the urban–rural income gap with these results remaining robust across multiple tests. Urbanization and marketization are pivotal mechanisms driving the reduction in the urban–rural income disparity in integrated regions. Additionally, heterogeneity analysis uncovers significant spatial and temporal variations in the urban–rural income gap narrowing effect of integration expansion. Specifically, over time, the effect transitions from a significant negative impact to an insignificant positive one, while spatially, significant negative effects are observed in Jiangsu and Zhejiang provinces, contrasting with insignificant positive effects in Anhui province. This study offers fresh perspectives on the nexus between regional integration and the urban–rural income disparity, laying a scientific groundwork to evaluate the impacts of urban agglomeration integration and optimize policies aimed at fostering regional integration and coordinated urban–rural development.

1. Introduction

Since the 21st century, the global inequality landscape has undergone novel transformations. Notably, the rise of emerging economies has narrowed the economic disparity between developing and developed nations. Paradoxically, concurrent with rapid economic development, intra-national inequality has intensified [1]. As an influential developing country, China has witnessed a notable urban–rural income gap alongside its rapid economic growth, which stands as a prominent feature of income inequality within the country [2]. Since 2012, China’s urban–rural income gap has entered the descending phase of the inverted-U trend [3], experiencing a steady narrowing over the past decade. Specifically, the disparity in per capita income between urban and rural areas has narrowed with the ratio decreasing from 3.10 in 2012 to 2.39 in 2023 [4]. However, when examined on a global scale, this ratio still remains comparatively high, and regional disparities continue to persist [5,6]. Moreover, in the present and foreseeable future, China’s economic growth rate is decelerating, accompanied by intensifying pressures from structural unemployment and shrinking fiscal space, which further complicate the endeavor to bridge the income disparity between urban and rural areas. In response to this backdrop, China has embarked on a new strategic objective of fostering common prosperity, aiming to balance sustainable economic growth with equitable income distribution to tackle the contradiction of imbalanced and inadequate development. Within this framework, narrowing the urban–rural income gap and promoting coordinated regional development are highlighted as core elements [7]. Hence, narrowing the income gap between urban and rural areas through fostering coordinated urban–rural development not only poses major challenges for China in the new development stage but also constitutes essential facets in the transition toward inclusive and sustainable growth paradigms, as well as the realization of the vision of common prosperity, carrying important practical and policy implications. Regional integration development represents a significant potential pathway to narrowing the gap. Typically, regional integration is accompanied by accelerated economic growth and the free flow of various production factors, which contribute to enhancing production efficiency, expanding employment opportunities, and diversifying income sources for both urban and rural residents. These factors collectively constitute one of the keys to optimizing income distribution between urban and rural. The Yangtze River Delta (YRD) region stands out as a prime example of integrated regional expansion. As one of China’s most economically developed and densely populated regions, the YRD region has undergone significant economic expansion and urban development in recent decades. However, it has also faced issues of intra-regional inequality and disparities between urban and rural areas. Thus, conducting an empirical study on the common prosperity effect of integrated regional expansion in the YRD is of utmost importance. This study aims to explore whether and how integrated regional expansion strategies can contribute to narrowing the urban–rural income gap and promoting coordinated urban–rural development. By addressing these research questions, this study seeks to provide valuable insights and policy recommendations for fostering common prosperity.

2. Theoretical Background

In the process of regional development, space emerges as a crucial element with regional progress being achieved through the transformation and reconstruction of diverse spaces to maximize economic benefits. The theory of spatial production emphasizes that space is a vital dimension of social production, playing a significant role in promoting regional development and providing a useful perspective for theoretical analysis. This theory views spatial production as the process of space being developed, utilized, and reshaped, wherein economic, political, cultural, and other diverse factors remold space, leading to its commercialization and capitalization, which contribute to advancing regional urbanization [8]. However, in the pursuit of profit, capital is driven by continuous expansion and accumulation, inevitably leading to resource concentration and spatial differentiation. Specifically, capital tends to flow more readily to areas with higher rates of return, such as economically developed regions with well-established infrastructure and abundant human resources [9]. This agglomeration effect promotes economic growth in these areas but may also induce an urban siphon effect, suppressing development opportunities in surrounding areas, thereby resulting in spatial inequality and unbalanced regional development. Furthermore, the theory of spatial production posits that the production of regional space involves not only the operation of capital logic but also the distribution and exercise of power [10]. This aligns with the perspective of geographical political economy, which contends that the distribution of political power influences regional unbalanced development [11]. In such unbalanced development, certain areas may garner more development opportunities and resources due to their possession of greater political and economic power. This inequality in the distribution of political power and resources further exacerbates regional unbalanced development. The urban-bias theory also points out that top–down development policies centered on large cities concentrate political power in urban groups, causing economic and social resources to flow unreasonably into urban areas, leading to unbalanced development between urban and rural regions [12]. Overall, under the operational logic of capital and power, regional development is influenced by the interactive evolution of institutional and spatial structural factors such as economics and politics. Socio-economic activities within and between regions produce different spatial effects, resulting in a convergence or divergence in regional development. Promoting coordinated regional development necessitates eliminating unfavorable institutional factors, facilitating rational and orderly flows and the optimal allocation of production factors such as capital, labor, and technology within regional spaces, and optimizing the interaction mechanism between institutions and space. Therefore, in studying regional and urban–rural development, it is necessary to attempt to open the “black box” of the impact of institutions on regional economic development. This will be conducive to formulating scientific and reasonable regional development policies, serving as a catalyst for harmonizing regional economic and social development.

Against the backdrop of the complexity and multidimensionality of global income distribution inequality, inequality in income distribution is prominent at various levels, including regions, urban and rural, and individual level. China has made strategic arrangements to solidly advance common prosperity, focusing on bridging the urban–rural income inequality and using coordinated regional development as a breakthrough to narrow income distribution disparities through reducing regional development gaps, thereby fostering common prosperity for all. As an important institutional arrangement for the central government to coordinate regional development, regional integration involves the interconnected development of various regions in production, distribution, and governance, inevitably impacting market resource allocation and political power distribution within the integrated region, thereby affecting the flow of urban and rural factors and policy development orientation. According to the theory of flow space [13], regional integration contributes to forming networks through cross-regional flow and connectivity, enhancing market accessibility, facilitating factor mobility, optimizing the market-oriented mechanism for urban and rural development, and impacting the bridging of the urban–rural income gap. Building on strengthened economic ties among regions, regional integration is actively expanding into areas such as transportation, entrepreneurship and employment, public services, and social security, contributing to people-centered urbanization and promoting urban development, thereby impacting the income gap.

Based on the aforementioned theoretical background, this study focuses on the interaction between institutional factors and regional socio-economic spaces in regional development. It explores the impact of regional integration and the pathways through which such impact occurs.

3. Literature Review and Research Hypotheses

Following the historic achievement of eradicating rural absolute poverty, China has embarked on a new journey, establishing the realization of common prosperity for all people as a pivotal strategic objective for national development. Achieving common prosperity is of paramount importance for ensuring social equity, fostering sustainable economic growth, and realizing long-term national security [14]. This strategy aims to comprehensively narrow income disparities among regions, between urban and rural areas, and among different social groups, thereby fostering a more balanced and harmonious social development landscape. In this context, bridging the urban–rural gap has undoubtedly emerged as a crucial component and core focus in advancing the process toward common prosperity. Currently, the urban–rural disparity manifests in multiple and complex dimensions, primarily concentrating on four key areas: infrastructure development, basic public service provision, residents’ income levels, and social governance capabilities. Among these, the income disparity between urban and rural areas stands out prominently, serving as a major bottleneck that constrains integrated urban–rural development and undermines social equity and justice, because the existence of a significant disparity between urban and rural areas in China represents one of the prevalent social issues [15].

For the purpose of our study, having a clear understanding of the current academic discussions on the determinants of the urban–rural income gap is very necessary. The determinants of the urban–rural income gap have been a focal point of academic interest. Numerous studies have examined this topic from multiple perspectives, including economic growth, income redistribution, institutional policies, and the provision of public goods and infrastructure. These studies have taken into account factors such as the level and quality of economic development [16,17], foreign direct investment [18,19], taxation [20,21], social security expenditures [22], urban-biased policies [23], and transportation [24] and communication infrastructure [25,26], yielding a wealth of research findings.

Although numerous studies have pointed out that the urban–rural income gap is the result of the combined action of multiple factors, existing studies seem to be confined to the institutional economics thinking framework to examine the function of economic, political and cultural systems, ignoring the spatial production and dynamic evolution process of urban and rural development [27]. In accordance with the spatial production theory, the essence of integrated urban–rural development is a spatial production process, which hinges on the rational allocation of spatial resources of diverse elements such as economy, politics, population, technology, and natural endowments by different agents and the facilitation of the joint enjoyment of spatial benefits. Therefore, it is essential to examine the spatial interaction behaviors of different agents and multiple elements between urban and rural areas in the research on the urban–rural income gap. Notably, with the advancement of regional integration, the trends of dynamic spatial expansion and cross-regional cooperation, exemplified by regional dynamically interconnected networks such as urban agglomerations and metropolitan areas, have increasingly reshaped the original market and economic pattern. Recent researches also indicate that regional integration will enhance interconnectivity on a broader scale, fostering greater connectivity between urban and rural areas and benefiting the development of urban–rural integration [28,29]. This will exert a profound impact on the coordinated economic and social development of urban and rural areas as well as the variation in income gap. In fact, regional integration policies have been widely adopted globally as crucial policy tools to weaken barriers to factor mobility, narrow regional development gaps, and promote coordinated regional development.

Extensive research studies have been conducted to discuss the role of regional integration in promoting economic growth and narrowing development gaps. Most studies concur that regional integration exerts a positive influence on the economic growth of the entire region. For instance, a study on the 2004 enlargement of the European Union found that regional integration stimulates economic vitality in new member states, manifesting in improved economic conditions such as labor mobility, trade and investment, and enterprise production [30]. Some scholars also found that increasing the degree of economic integration can promote the cross-border spillover of knowledge among countries or regions, thereby increasing the accumulation of human capital and physical capital, improving productivity and facilitating economic growth [31,32]. Some scholars who studied the integration of the Yangtze River Delta urban agglomeration in China found that the mechanisms by which regional integration promotes economic growth mainly lie in the economic connection mechanism, industrial division mechanism, market unification mechanism, and factor aggregation mechanism with varying impacts on city members of different locations, sizes, and batches [33,34,35,36]. However, other studies have indicated that the economic impact of a unified market on regional integration development should not be considered in isolation. Instead, the quality of regional governance and the efficiency of institutional coordination may have a crucial impact on economic growth, resulting in the limited role of regional integration in economy and different impacts on different indicators [37].

While regional integration fosters economic growth in the aggregate, there exists divergence regarding whether it simultaneously promotes balanced regional development and reduces inequality. One strand of research argues that regional integration not only drives economic expansion but also potentially benefits less affluent regions the most, facilitating economic convergence with richer areas through unified markets, technology diffusion, transfer payments, and trade cooperation, thereby narrowing inter-regional development disparities [38,39,40]. Conversely, other studies have observed that while regional integration mitigates inter-regional inequality, intra-regional inequality intensifies, particularly in regions with lower economic development levels [41]. Furthermore, scholars have noted that intra-regional inequality demonstrates significant spatial heterogeneity, manifesting as developmental disparities between metropolitan areas and intermediate and peripheral regions, while the diffusion effects of regional integration have not been fully realized [42,43]. Additionally, some research argued that different aspects of regional integration may exert distinct impacts on intra-regional income inequality [44]. One study found a significant correlation between political integration and income inequality, whereas economic integration exhibits a non-linear effect on income inequality, presenting an inverted U-shaped relationship [45]. However, there are also findings indicating that economic integration has no impact on income inequality [46].

Overall, the research findings concerning the economic growth and balanced development impacts of regional integration display a differentiated landscape. The inquiry into whether regional integration, while fostering overall benefits, can propel balanced regional development and narrow income disparities necessitates profound exploration. Additionally, there is room for deepening the relevant research: Firstly, most studies on the relationship between regional integration and income disparities focus on income gaps between sovereign nations or transnational regions and between cities with insufficient attention paid to urban–rural income gap. Secondly, relevant research primarily emphasizes correlations, lacking in-depth studies on the underlying mechanisms. Thirdly, the current literature largely views regional integration as a composite of economic, market, and political integration across multiple domains without recognizing it as a dynamic process involving spatial expansion and horizontal deepening. Studies that do consider integration expansion examine only single instances of expansion [33,34], neglecting the heterogeneity of gradual expansion and spatiotemporal impacts, which may compromise the accuracy of research conclusions. These aspects will be thoroughly explored and expanded upon in the present study.

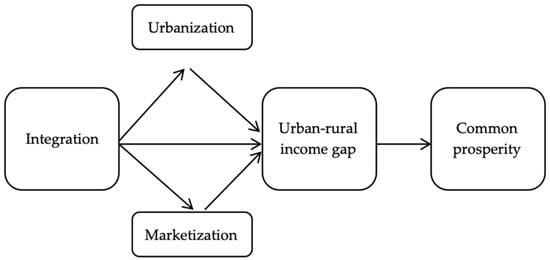

The regional integration of the YRD was elevated to a national strategy of China in 2019 and was endowed with significant implications for radiating and driving the coordinated development within the region. Its regional integration encompasses multiple fields such as scientific and technological innovation, infrastructure construction, ecological environment, and public services. Moreover, it improves the integration level deeply through multiple means such as coordinated planning, joint institutional innovation, and market-oriented operation, making it one of the regions with the most dynamic economic development, the highest degree of openness, and the strongest innovation capacity in China and a model region for China’s regional integration development. Additionally, it earlier established the “Yangtze River Delta Urban Economic Coordination Council” under the leadership of local governments to coordinate the affairs of regional integration expansion, and the gradual expansion of regional integration is typical. Therefore, based on the existing achievements, this research formulates the following three research hypotheses (and the logical framework for the following empirical analysis of this study is illustrated in Figure 1):

Hypothesis 1:

Cities that integrate into the Yangtze River Delta (YRD) regional integration can significantly narrow the urban–rural income gap.

Hypothesis 2:

Urbanization and marketization serve as the driving mechanisms through which YRD regional integration influences the urban–rural income gap.

Hypothesis 3:

The impact of the expansion of the YRD regional integration on the urban–rural income gap exhibits heterogeneity in both time and space.

Figure 1.

Mechanisms of integrated regional expansion impacting common prosperity.

The possible marginal contributions of this paper are as follows. (1) In terms of research perspective, exploring the impact of regional integration on the urban–rural income gap enriches the existing research on the urban–rural income gap. (2) In terms of research content, not only does it study the overall effect and potential mechanism of action of the expansion of the integrated region on common prosperity but also conducts an in-depth study of the heterogeneous effects in time and space, enhancing the comprehensiveness and depth of the research and providing abundant empirical evidence and policy implications for government departments to formulate practical policy recommendations. (3) In terms of research methods, based on the panel data of the Yangtze River Delta, taking the expansion of regional integration in the Yangtze River Delta as a quasi-natural experimental object, a time-varying Difference-in-Differences model is constructed to identify the common prosperity effect of integration, and a series of robustness tests are carried out to ensure the credibility of the research.

4. Methodology

4.1. Study Area

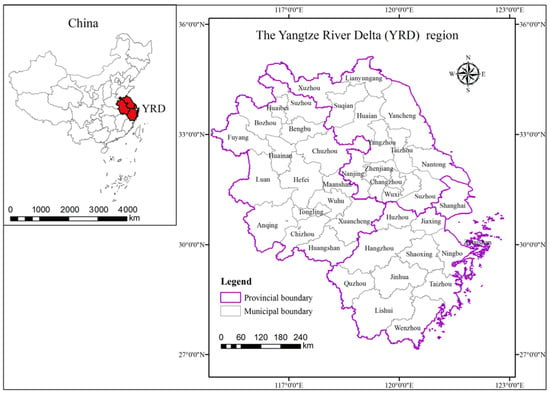

As China’s regional development strategies advance, urban agglomerations have emerged as critical vehicles for economic and social progress. The Yangtze River Delta urban agglomeration, situated in China’s eastern coastal area (as depicted in Figure 2), encompasses Shanghai Municipality, Jiangsu Province, Zhejiang Province, and Anhui Province. This agglomeration not only epitomizes China’s economic and social development but also constitutes one of the cornerstone regions underpinning the nation’s economic growth. With an area comprising merely 2.1% of China’s total landmass, it ranks as the sixth largest urban agglomeration globally, contributing approximately one quarter of the country’s total economic output and industrial added value. Economic growth constitutes the foundational pillar for achieving common prosperity, and the rapid economic growth in the Yangtze River Delta has led to elevated income levels for both urban and rural residents. In 2023, urban and rural residents in the Yangtze River Delta earned RMB 68,800 and RMB 30,700, respectively, significantly surpassing China’s national averages of RMB 51,800 and RMB 21,700. When examining the income ratio between urban and rural residents, the Yangtze River Delta’s is 2.24 and lower than the national average (2.39). However, this disparity remains relatively high globally. As one of the most densely populated urban agglomerations worldwide, the notable urban–rural income gap not only restricts economic and social development but also increases social instability. Furthermore, this region exists notable variations in policy environments, industrial structures, and location conditions among different cities. Conducting empirical research on the Yangtze River Delta can provide richer insights for developing countries striving to achieve coordinated urban–rural development.

Figure 2.

Location map and administrative divisions of the Yangtze River Delta.

The urban–rural income gap is the result of a multifaceted interplay of complex factors. With the advancement of modern technology and the intensification of urban connections, the competitive and cooperative relationships among cities during the integration process have emerged as one of the significant factors influencing urban development and the evolution of the urban–rural income gap [47,48]. This phenomenon is equally prominent in the Yangtze River Delta. This study aims to explore the impact of integration on the urban–rural income gap. In practice, the government-led integration of urban agglomerations is a dynamic and intricate process that is primarily characterized by the co-evolution of spatial expansion and integration deepening within the region. Specifically, on the one hand, the central government promotes the coordination of local interest relationships and guides institutional improvements through planning. On the other hand, local governments, as participants and drivers of integration, engage in integration development based on “cost–benefit” analyses to achieve higher-quality development for themselves. Both entities achieve the coordinated evolution of “spatial expansion and level deepening” within urban agglomerations through complex mechanisms. However, the planning-based integration process also exhibits phenomena of integration area disorganization.

In response to the above consideration, this study defines regional integration from the perspective of local government cooperation. Especially, the “Yangtze River Delta Cities Economic Coordination Conference”, an official organization promoting integration among local governments, serves not only as the primary negotiation body for urban cooperation but also expands the scope of integration through phased and gradual expansion, providing a valuable research perspective for this study. In fact, as an organization implementing central government macro policies and promoting deeper cooperation, the Yangtze River Delta Cities Economic Coordination Council has always been a pivotal entity in driving the synchronous evolution of spatial expansion and deepening integration levels within the Yangtze River Delta integrated region [33,34,35].

4.2. Empirical Model

This paper aims to measure the effect of common prosperity associated with the expansion of the Yangtze River Delta integration region. However, in the empirical analysis, there are some obvious biases in conclusions drawn from direct comparisons of urban–rural income gaps either pre- and post-integration within the same city or between integrated and non-integrated cities [49,50]. The Difference-in-Differences method is a classical approach to overcoming such estimation biases. The standard DID model assumes the uniform timing of policy implementation across the treatment group and a constant intervention status throughout the observation period. However, in the real world, many policies differ in terms of both timing and spatial coverage, and some individuals may even change their treatment status within the observation period. Considering the gradual process of regional integration expansion and the research approaches and methods employed in existing studies [35,51], this paper adopts a time-varying Difference-in-Differences model to measure the common prosperity effect of regional integration expansion. The basic model was constructed as follows:

This is a two-way fixed effect model. Compared with the standard Difference-in-Difference model, the time-varying DID replace the interaction term with a treatment variable that varies over time and across individuals. Among them, is used to distinguish between different individuals. is used to distinguish different time periods. is the income gap between urban and rural, which will be defined with greater precision in the subsequent paragraphs. represents a series of control variables that vary over time and across individuals. is the random disturbance term, while and are the fixed effects of city and time, respectively.

To further examine the mechanisms through which the expansion of region influences common prosperity, the mediating effect models were employed, taking into account theoretical mechanism analysis and data availability. Here, is the mediating variable, and the remaining variables have the same meaning as in Equation (1).

If is significantly non-zero and there is a significant difference between and , then it can be concluded that serves as an effective mediator. Whether functions as a complete mediator or a partial mediator can be determined by referring to existing research [52].

It is noteworthy that in the robustness check section, this study not only alters the estimation method and replaces the measurement of the dependent variable but also introduces a Spatial Durbin Model (SDM) for analysis, taking into account the spatial spillover effects.

As in Equation (4), W represents the spatial weight matrix, used to express spatial or economic distances between different cities; when the model is specifically utilized later on, more detailed explanations will be provided.

4.3. Variable Description and Data Specification

(1) Explained variables. The notable urban–rural income gap in China is the important part of regional imbalanced development as well as a crucial factor constraining the pursuit of common prosperity, which is characterized by the ratio of disposable income per capita of urban and rural households. In this regard, the present study selects the ratio of urban to rural residents’ disposable income as an indicator of urban–rural income disparity and as a proxy for the level of common prosperity. A lower urban–rural income ratio signifies a higher degree of common prosperity. Despite adjustments made to the statistical criteria for urban and rural residents’ income since 2013, these adjustments have not led to significant discontinuities in the indicator, and thus, the data used in this study remain unadjusted.

(2) Explanatory variables. A city’s accession to the Coordination Council also represents a crucial path to integrating into the Yangtze River Delta, reflecting the comprehensive level of the city’s participation in the integration process. Drawing on existing studies [33,34,35,51], we introduce an explanatory variable in the form of a dummy variable, which is labeled “integration into the Coordination Council.” This variable is assigned a value of 1 if a city joins the Coordination Council in year t and 0 otherwise. Specifically, the cities that joined in 1997 include Wuxi, Ningbo, Shanghai, Yangzhou, Hangzhou, Shaoxing, Nanjing, Nantong, Changzhou, Huzhou, Jiaxing, Zhenjiang, Zhoushan, and Taizhou; the city that joined in 2003 is Taizhou; the cities that joined in 2010 are Hefei, Yancheng, Ma’anshan, Jinhua, Huaian, and Quzhou; the cities that joined in 2013 are Xuzhou, Wuhu, Chuzhou, Huainan, Lishui, Wenzhou, Suqian, and Lianyungang; and the cities that joined in 2018 are Tongling, Anqing, Chizhou, and Xuancheng.

(3) Control variables. Based on relevant research [33,34,35,36], we selected the following control variables. The industrial structure may affect the urban–rural income gap by facilitating labor mobility, altering marginal returns to factors, and increasing employment income. In this study, this indicator is measured by the proportion of the primary industry in GDP (inds1) and the proportion of secondary industry in GDP (inds2). The level of economic development in cities constitutes the foundation for urban–rural income distribution. We used the logarithm of GDP per capita (lngdp) to characterize cities’ economic development level. Opening up to the outside world can accelerate urbanization through technology transfer, factor mobility, and industrial development, thereby influencing the urban–rural income gap. This indicator is measured by considering both foreign trade dependence and foreign investment dependence with the former measured by the ratio of total import and export volume to annual GDP for each city (dieport) and the latter by the proportion of foreign investment in GDP for each city (dfinv). Good transportation facilities are crucial for promoting factor mobility, strengthening the economic ties, and increasing employment income. The condition of transportation facilities is measured by the logarithms of road mileage (lnroad), expressway mileage (lnhroad), and total passenger transport volume (lnp). The imbalance in the regional structure allocated by the government is a key factor influencing the widening urban–rural income gap, involving the government’s focus and its allocation efficiency of various resources within and outside the system. For this key variable, this study uses the logarithm of government public fiscal expenditure (lngovexp) as a measure. Labor force is an important production factor for regional economic development. For this indicator, we considered population density (popdensity) and the scale of college students (lnu). Regions with higher population density contribute to increased labor supply, expanded market size, and increased consumer demand, while high-quality labor can stimulate economic growth drivers such as knowledge dissemination and technological innovation, potentially impacting the urban–rural income gap. In this study, population density is measured by the number of people per unit area, and the scale of college students is represented by the number of students enrolled in regular higher education per 10,000 people.

(4) Mediating variable. This study argues that urbanization and marketization are important mechanisms through which regional integration affects the urban–rural income gap. Urbanization serves as a significant impetus for regional economic growth and exerts a profound influence on the urban–rural income gap [15,53]. Especially, well-managed urbanization can promote welfare effects by facilitating the transfer of rural labor force, fostering complementary collaboration between industry and agriculture, extending infrastructure, and promoting the equalization of public services [54]. In this study, urbanization is measured by the urbanization rate, which is calculated using demographic indicators to determine the proportion of the urban population to the total population. Marketization represents an effective mechanism to dismantle barriers to factor mobility between urban and rural areas and facilitate the orderly and rational flow of various resources across these regions [33,34]. Especially for developing economies, advancements in the marketization process are conducive to promoting market integration and fair competition, leveraging the scale effects of a unified large market, and exerting a significant impact on the urban–rural income gap. In this research, the level of marketization is measured according to the methodology proposed by Wang et al. [55].

Given the availability and authoritativeness of data, the data used in this paper are sourced from statistical yearbooks, statistical bulletins, and other official publications of China, Jiangsu, Zhejiang, Shanghai, Anhui, and relevant cities. Meanwhile, this study takes into account various interfering factors, including the different timing of cities’ entry into the coordination mechanism, the uneven impact of the COVID-19 pandemic outbreak in 2019 on the urban–rural income gap, and the construction of the common prosperity demonstration zone in Zhejiang Province initiated in 2021. Hence, the study period selected for this paper is from 2000 to 2019. The data processing conducted in this paper mainly encompasses the following aspects. ① Based on the administrative divisions of 2010, the city data involving administrative division adjustments were estimated using county-level adjustment data. ② Economic data were benchmarked against the year 2000 and adjusted using GDP indices, retail price indices for commodities, and fixed asset investment price indices for the raw data (provincial data were used as substitutes for missing city indices). ③ For partially missing data, estimations were made with reference to historical annual growth rates. ④ The total import and export volume priced in USD was converted into RMB using the annual average middle exchange rate of RMB against USD and then divided by nominal GDP to obtain the level of openness to the outside world for that year. The simple descriptive statistics for all variables are presented in Table 1. Prior to the formal analysis, the present study conducted an examination of the issue of multicollinearity among various variables including both treatment and control variables base on a simple regression model. Calculations revealed that no such issue existed (Mean VIF = 3.45). The calculation and estimate results in this paper were all obtained by Stata 17.

Table 1.

Variable description and descriptive statistics.

5. Empirical Results Analysis

5.1. Benchmark Model Results

The benchmark model estimation reveals (Table 2) that the coefficient of the explanatory variable is significantly negative regardless of whether no control variables, some control variables, or all control variables are included. These results indicate that cities’ participation in integrated regions can significantly narrow the urban–rural income gap. Namely, the integrated development of urban agglomerations facilitates the advancement of China’s common prosperity strategy. In fact, the significant contribution of urban agglomeration integration to economic growth has been confirmed by numerous studies [33,34,36]. As a cooperation and exchange mechanism for urban coordination, the expansion of the Coordination Council and the associated infrastructure interconnection [56,57], accelerated factor mobility [34,35], deepened industrial division of labor [56,58], and coordinated innovative development [59] all contribute to narrowing the urban–rural income gap by promoting economic growth, increasing the incomes of urban and rural residents, accelerating population mobility, and generating employment and income effects. In other words, this paper quantitatively verified that the expansion of urban agglomeration integration is conducive to promoting common prosperity.

Table 2.

Regression results of the benchmark model.

5.2. Robustness Tests

(1) Replacement of the estimation model. Although in the baseline model, this study has already controlled for individual and time effects to minimize the impact of omitted variables as much as possible, there are situations where analysis of three-dimensional or even higher-dimensional data is required. Drawing on existing research [60], and out of prudence, this paper employs linear regressions with multiple fixed effects to further verify the robustness of the conclusions; we only consider those unobserved variables that vary across individuals but remain constant over time to see if they have a significant impact on the results. The results indicate (Model 1 in Table 3) that the coefficient of the explanatory variable remains significantly negative, and the magnitude of the estimated coefficient remains unchanged (compared to Model 6 in Table 2). Therefore, the regression results from the baseline model are reliable.

Table 3.

Robustness test results.

(2) Altering the measurement method of the dependent variable. The income gap between residents can be characterized by various indicators, and residents’ consumption levels are more influenced by income scale [61,62]. In this regard, this paper adopts the absolute difference in urban–rural income to estimate the level of urban–rural income disparity and includes its natural logarithm in the baseline model. The results show (Model 2 in Table 3) that the coefficient of the explanatory variable is also significantly negative, demonstrating the robustness of the regression results from the baseline model.

(3) Considering sample comparability. In the socialist market economy with Chinese characteristics, both central and local governments have significant impacts on regional economic and social development. Especially, their differences in political status and economic functions significantly influence factor agglomeration and the evolution of the urban–rural income gap [63,64]. Given the special political status, economic functions, and urban–rural structures of municipalities and provincial capitals, especially their greater power in resource allocation due to uneven policy resources, further empirical tests were conducted excluding cities such as Shanghai, Nanjing, Hangzhou, and Hefei (Column 3 in Table 3). The results found that the coefficient of the explanatory variable was also significantly negative, further verifying the robustness of the baseline model.

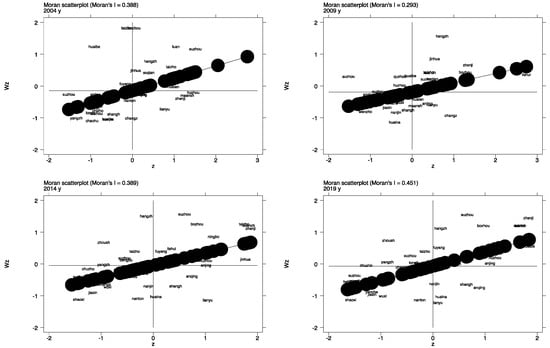

(4) Considering spatial spillover effects. Firstly, we calculated the Moran’s I, which is a crucial indicator for measuring spatial autocorrelation. Figure 3 presents the Moran’s I maps for four representative years spanning from 2000 to 2019. It can be observed that there exists positive spatial autocorrelation within the region, which generally intensifies over time. The Moran’s I increased from 0.388 in 2004 to 0.451 in 2019. However, it should be noted that this index does not solely represent spatial autocorrelation; additional methods are necessary for verification and comprehensive consideration. The Spatial Durbin Model (SDM) is employed as a supplementary robustness check [65]. Initially, a spatial weight matrix (W) is constructed, and a 42 × 42 adjacency matrix is generated for the 42 cities in the YRD, comprising both the control and treatment groups. The elements of this matrix are binary with a value of 1 assigned if two cities are adjacent and 0 otherwise. The main diagonal elements are all set to 0, as a city cannot be adjacent to itself. This adjacency matrix is then standardized to obtain the spatial weight matrix. The specific computational results of the SDM are presented in Model 4 of Table 3 (for ease of comparison, only some simple yet crucial results are shown). It is evident that a positive spatial spillover effect exists (rho = 0.373, p < 0.01), indicating that the urban–rural income gap in a city is influenced not only by its own integration into the YRD development but also by the integration of its adjacent cities. The direct effect accounts for only about 20% of the total effect, suggesting that the spatial spillover effect is pronounced.

Figure 3.

Moran scatter plot of urban–rural income gap of cities in YRD (2004, 2009, 2014 and 2019).

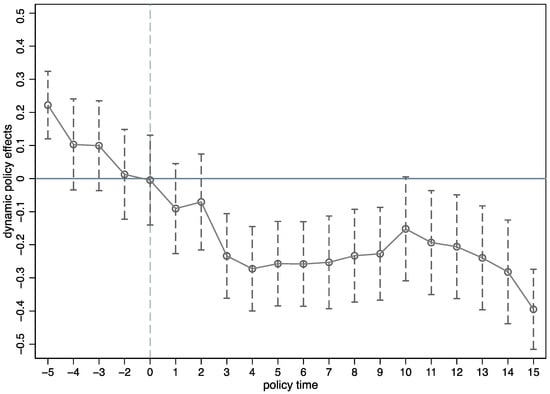

(5) Parallel Trends Test. The satisfaction of the parallel trends assumption by the sample data is a prerequisite for the reliability of the estimation results from the Difference-in-Differences model [33,59]. The parallel trends assumption necessitates that the outcome variable exhibits comparable or parallel time series characteristics between the treatment and control groups prior to the policy implementation. These can ensure the randomness and exogeneity of the policy treatment and prevent estimation bias due to systematic differences between the two groups before the policy intervention. This study employs the time-varying Difference-in-Differences model, which also necessitates a parallel trends test. According to the ideas and methods of existing research [35,49], we conducted such a test with the results presented in Figure 4. In the period prior to the policy implementation, there was no significant difference in the urban–rural income gap between the two groups (cities that joined and did not join the Coordination Council), as evidenced by the 95% confidence interval encompassing zero. However, following the policy implementation, the urban–rural income gap in the treatment group (cities that joined the Coordination Council) was lower than that in the control group. This pattern became increasingly evident and significant particularly after the third year of joining the Coordination Council. Therefore, the data in this study satisfy the parallel trends assumption, and the conditions for applying the time-varying Difference-in-Differences model are met. The empirical findings demonstrate high credibility and robustness; in other words, Hypothesis 1 has been substantiated.

Figure 4.

Parallel trends test results.

5.3. Mechanism Analysis with the Mediating Effect Model

Empirical studies reveal that cities’ accession to the integrated region can lead to a reduction in the urban–rural income gap, which undoubtedly contributes to the realization of the goal of common prosperity. From the perspective of applying theoretical guidance to practice, scientifically identifying the driving mechanisms through which integration affects the urban–rural income gap is of great significance for underpinning the formulation and implementation of relevant policies. Taking into comprehensive consideration the influencing factors, in light of the reality that China’s economic and social development remains in the stage of rapid industrialization and urbanization, along with the accelerated improvement of the socialist market economy, this paper focuses on exploring the specific driving mechanisms of urbanization and marketization therein.

(1) Urbanization. Numerous studies [14,15,53,54] have indicated that urbanization exerts multifaceted effects on both economic growth and income distribution. The rural–urban migration during the urbanization process and the resulting convergence in factor returns between rural and urban areas constitute one of the significant mechanisms for narrowing the urban–rural income gap. However, the Chinese dual economic system is characterized by significant rural–urban segmentation, such as economic promotion strategies based on urban bias and stringent household registration systems, which has constrained rural–urban migration and the urbanization process. This represents one of the crucial factors contributing to the large urban–rural income gap in China. The deepening integration of urban agglomerations not only provides job opportunities for urban residents through industrial transfers and accelerates the urbanization process but also enhances residents’ income growth and the level of urbanization by driving population mobility on a larger scale. Therefore, it is of research value to explore whether the expansion of integrated regions can influence the urban–rural income gap by promoting urbanization, using the urbanization rate as a mediating variable. According to the research results (Table 4), the coefficient of the explanatory variable in Model 1 is significantly negative, indicating the presence of a mediation effect of integrated regional expansion on the urban–rural income gap. The significant positive effect of the explanatory variable on the mediator in Model 2 suggests that integrated regional expansion can significantly enhance the urbanization rate of cities. Specifically, urban agglomeration integration provides more space for industrial relocation and transformation in developed cities, while less developed cities achieve rapid urbanization and industrialization by undertaking industrial transfer from developed cities [66]. These processes contribute to the increase in urbanization levels by attracting population migration from rural to urban areas both within and between cities. The coefficient of the mediator in Model 3 is significantly negative, indicating that the urbanization process can significantly narrow the urban–rural income gap. That is, urbanization exhibits a mediation effect on the influence of integrated regional expansion on the urban–rural income gap. Overall, rural–urban population mobility during the urbanization process not only enhances urban and rural income levels through the economic growth effect but also affects factor spatial allocation and narrows the urban–rural income gap through agglomeration, feedback, and radiation effects [67,68].

Table 4.

Regression results of the mediating effect models.

(2) Marketization. Research on the influencing factors of the urban–rural income gap has shown that the unbalanced factor allocation between urban and rural areas, as well as the impeded flow of factors such as labor, are the fundamental mechanisms leading to the widening of the urban–rural income gap. Therefore, scholars hold that the free flow of factors under the guidance of the market mechanism is a core measure to promote economic growth and narrow the urban–rural income gap [33,69]. Constrained by institutional factors such as prominent administrative separation and the GDP tournament in China, there is significant market segmentation within and between cities, resulting in unreasonable phenomena such as a decline in factor allocation efficiency and a widening of the urban–rural income gap. The profound connotation of the integration of urban agglomerations lies in strengthening cooperation among cities. In particular, the deepening of industrial division of labor and the connection of transportation facilities all bring about the mutual opening of markets among cities, and the emergence of related positive effects also promotes the improvement of the urban marketization level. Therefore, this paper takes marketization as a mediating variable to explore whether the expansion of the regional integration can affect the urban–rural income gap by promoting marketization. As shown in the research results (Table 4), the coefficient of the explanatory variable in Model 4 is significantly negative, indicating the existence of a mediating effect of the expansion of the integrated region on the urban–rural income gap. The significant positive effect of the explanatory variable on the mediating variable in Model 5 demonstrates that the expansion of the integrated region can significantly boost the marketization level of cities. In fact, the integration cooperation based on the Coordinating Council is a process from the shallow to the deep, from specific matters to institutional arrangements. With the improvement of cooperation systems among cities and the weakening of administrative barriers, under the combined effects of a larger integrated market, convenient factor mobility, and competitive market demands, both the marketization level and systems of cities have been remarkably enhanced [33,34,35]. Certainly, the elevation of the market integration level resulting from joining the coordinating committee, to some extent, validates the scientific nature of the definition of the integration process in this paper. The coefficient of the mediating variable in Model 3 is significantly negative, suggesting that the improvement of the marketization level can significantly narrow the urban–rural income gap; that is, the marketization plays a mediating role in the impact of the expansion of the integrated region on the urban–rural income gap. Overall, the marketization during the integration process not only promotes faster economic growth in cities but also narrows the urban–rural income gap through the optimal allocation of resources.

In summary, based on empirical tests of mediation effects, the increase in urbanization rates and the enhancement of marketization levels resulting from cities’ participation in integration contribute to narrowing the urban–rural income gap. This implies that Hypothesis 2 has been validated as correct. This also points out the direction for cities to achieve common prosperity in the process of integration, namely, by establishing institutions conducive to urbanization and marketization while strengthening urban cooperation. The relatively low contribution rates of urbanization and marketization to the impact of integration area expansion on the urban–rural income gap also reflect the objective realities of low-quality urbanization and the need for improvement in marketization institutions.

5.4. Heterogeneity Tests

In general, municipal regional economic development is indeed influenced by a multitude of factors, including location, policy, and resources, whose heterogeneity has been thoroughly substantiated in numerous academic studies [13,14]. From a temporal perspective, as the process of regional integration advances, changes in the urban–rural income gap may exhibit distinct trends. On the one hand, integration may enhance overall economic efficiency and residents’ income levels by optimizing resource allocation and promoting collaborative industrial development, thereby contributing to narrowing the urban–rural income gap. On the other hand, integration may also lead to a concentration of resources in urban areas, exacerbating the urban–rural economic disparity. Especially in the initial stages of integration, due to the preferential allocation of various policies and resources, cities may gain more development opportunities and advantages, while rural areas may lag behind. However, over time, the deepening of the integration process may gradually mitigate this disparity, achieving balanced growth in urban and rural incomes through measures such as integrated urban–rural development and the equalization of public services. From a spatial perspective, heterogeneity in impacts may equally exist. Due to differences in natural conditions, economic foundations, and industrial structures, different regions may vary in their responsiveness and adaptability to integration. For instance, some regions may more easily benefit from the integration process due to their advantageous geographical locations and strong economic foundations, thereby achieving rapid growth in urban and rural incomes. In contrast, other regions may face greater challenges and difficulties due to poorer natural conditions and weaker economic foundations. Additionally, the industrial structures of different regions may also exert different influences on the integration process. Some regions may have modern agriculture, high-tech industries, and other dominant industries, which typically have higher added value and employment absorption capacity, contributing to narrowing the urban–rural income gap. Conversely, other regions may be dominated by traditional industries, which often have lower added value and limited employment absorption capacity, making it difficult to effectively drive economic development in rural areas. The expansion of an integrated region may exert heterogeneous impacts on the urban–rural income gap both over time and across space. Consequently, when devising integration strategies and policies, it is vital to fully account for regional and urban–rural disparities and adopt targeted measures to ensure balanced income growth and common prosperity. This study, therefore, empirically examines the temporal and spatial heterogeneity in the impact of the expansion of the Yangtze River Delta integrated region on the urban–rural income gap.

5.4.1. Temporal Heterogeneity

Urban development, macroeconomic policies, and other factors are all in the midst of complex and dynamic evolutionary processes. For the Yangtze River Delta, which boasts a high level of economic development and an early start in industrial restructuring, the dynamic evolution of urban agglomeration development is particularly significant. Especially after the shock of the 2008 global financial crisis, it is imperative to reassess the stability of the conventional export-oriented urban development paradigm. Concurrently, this process was accompanied by shifts in macroeconomic policies, such as the 2010 “Regional Planning for the Yangtze River Delta Region”, which aimed to better lead China’s economic transformation and development by strengthening urban cooperation. This section takes the critical juncture of 2010 as a time boundary and compares the effects of urban–rural income disparities resulting from the expansion of integrated regions between the two periods: 2000–2010 and 2011–2019.

The results of Model 1 and Model 2 in Table 5 indicate a trend of transition from a significant negative effect to a non-significant positive effect in related impacts. Generally, promoting the synergistic evolution of the regional expansion and regional integration level of the Yangtze River Delta integration is a gradual process. With the improvement of urban development levels, the increase in the number of integrated cities, and the deepening of urban cooperation, it also faces more competition and requires deeper institutional reforms for support. This may be an important mechanism leading to the transformation of the expansion effects of the integrated region. Specifically, (1) although the increase in cities participating in the Coordination Council can expand the market scale, the cooperative competition based on the “cost–benefit” comparison among cities also requires governments to bear cooperation costs. The increase in the number of cities due to expansion is accompanied by the emergence of negative integration effects and an increase in cooperation costs, such as the resurgence of local protectionism, intensified competition for factors, and heightened administrative barriers. These factors result in a loss of resource efficiency and increased difficulty in integrated development [70]. (2) During the gradual expansion of the Yangtze River Delta integration, cooperation among members of the Coordination Council does not completely exclude other cities. The development effects of newly joined cities are more driven by the “incremental” cooperation of integration institutions. However, with the deepening of regional integration, urban consultation and cooperation have gradually shifted from focusing on specific affairs, information exchange, and common market development toward institutional reform. Consequently, the difficulty of reforming incremental institutions has rapidly increased, and the marginal challenges in city cooperation have intensified [35].

Table 5.

Regression results of heterogeneity test.

5.4.2. Spatial Heterogeneity

Under the combined influence of complex factors, the development of urban agglomerations in China exhibits significant imbalances. In the case of the Yangtze River Delta, not only does the development gap between the “core and periphery” remain consistent, but there is also notable heterogeneity in the development status across different provinces. During the gradual expansion process centered on Shanghai, does this event exert significantly different effects on the urban–rural income gap in different cities? To address this question, this paper focuses on comparing the impact of the expansion of regional integration on the urban–rural income gap in cities of Jiangsu, Zhejiang, and Anhui, aiming to identify the existence of significant spatial heterogeneity. The empirical results are presented in Models 3 to 5 in sequence.

The results indicate that Jiangsu and Zhejiang exhibit significant negative effects, while Anhui displays a non-significant positive effect. That is, the higher the level of economic development, the stronger the effect of the urban–rural income gap resulting from the expansion of the integrated region. (1) Cities in Anhui, located on the periphery of the Yangtze River Delta integrated region, generally have a lower level of economic development and a significant development gap compared to core cities such as Shanghai with a clear gradient in industrial structure. During the process of integration, while urbanization and industrialization have been promoted through accepting the industrial transfer, there may also be phenomena such as the outflow of high-end factors, which is a key factor contributing to the non-significant effect on the urban–rural income gap. (2) During the study period, the economic development level of cities in Jiangsu and Zhejiang that joined the Coordination Council was relatively high within the Yangtze River Delta, and industrial transformation began earlier. With the deepening of integrated cooperation, these cities have been able to achieve the aggregation of high-end factors and the transfer of low-end industries during the expansion of regional integration, thereby accelerating industrial transformation and promoting higher-quality urbanization. Improvements in urban industrial quality and the deepening of integration can significantly contribute to narrowing the urban–rural income gap. Consequently, the results of spatial heterogeneity suggest that the formulation and implementation of macro policies should be tailored to local conditions. These findings indicate that the temporal and spatial heterogeneity of the common prosperity effect mentioned in Hypothesis 3 exists within the Yangtze River Delta integrated region covered by this study.

6. Conclusions

Considering the context of China’s proactive endeavors to enhance the development paradigm of the “19 + 2 Urban Agglomerations” and expedite the advancement of common prosperity, this study conceptualizes the enlargement of the YRD Urban Economic Coordination Council as a quasi-experimental setup that approximates natural conditions. This framework allows for a quantitative examination of the impacts and mechanisms through which such regional integration expansion influences the urban–rural income gap. Utilizing the YRD as an illustrative case, this paper embarks on a systematic exploration of the ramifications and underpinning mechanisms of regional integration’s expansion on the urban–rural income disparity.

Drawing upon China’s ongoing efforts to bridge the urban–rural income gap and the deepening of regional integration practices, our findings reveal that the expansion of integration within the YRD significantly contributes to narrowing this income disparity. Cities that have integrated into this region have seen a reduction of 0.095 in the urban–rural income ratio, which is equivalent to 24% of the standard deviation of this indicator. Furthermore, we have also found that the integration of the YRD has a positive spatial spillover effect on promoting common prosperity. This implies that as the integrated urban agglomeration expands, it not only narrows the urban–rural income gap locally but also exerts a positive influence on the urban–rural structure in surrounding areas. This conclusion carries dual significance: it not only offers strategic guidance for other regional integration initiatives within China but also stands as a valuable reference for developing nations striving to foster deeper regional integration.

The mechanistic tests conducted in this study underscore the pivotal role played by factors such as accelerated urbanization and heightened marketization during the integration process in mitigating the urban–rural income disparity; the proportion of the mediating effects contributed by the two factors to the total effect is approximately 10% and 15%, respectively. Furthermore, a comprehensive heterogeneity analysis underscores the temporal and spatial variations in the effect of regional integration’s expansion. These findings imply that policies aimed at achieving coordinated urban–rural development through integration must adapt to evolving circumstances and be tailored to local contexts.

Collectively, this research contributes to the existing studies by providing empirical evidence and theoretical insights into the intricate relationship between regional integration and the urban–rural income disparity with implications that extend beyond China to the broader global context of developing nations.

7. Discussion

Cities should prioritize enhancing their level of integration. The empirical research demonstrates that joining urban agglomeration integration is a pivotal mechanism for narrowing the urban–rural income gap within cities. However, further heterogeneity tests highlight that regional integration development cannot solely rely on paper agreements. Practical collaborations, such as institutional reforms, infrastructure improvement, and industrial cooperation, are essential to enable underdeveloped regions to better leverage the spillover effects of urban agglomeration development. Specifically, underdeveloped cities should fully integrate into the urban agglomeration’s integrated market and aggregate high-quality innovation factors while further optimizing their urban development environment and increasing their connection density with developed cities. By undertaking technology transfers from developed cities, enhancing the spatial spillover of factors, and improving urban marketization systems, these cities can achieve high-quality development within the context of integration.

In the process of integration, it is imperative to consider the potential negative consequences of this integration. Regional development disparities are a prevalent global phenomenon, and the heterogeneity observed in the economic prosperity effects of urban agglomeration integration, as identified in this study, requires further attention and research in order to prevent the emergence and accumulation of new disparities. Additionally, when examining spatial spillover effects, this study found that the integration of the YRD region has a positive spillover effect on reducing the urban–rural income gap among neighboring cities. The focus of integration should not only be on strengthening cooperation among cities and facilitating the free flow of factors across a broader scope to maximize scale effects but also on constructing coordinated development pathways that promote the emergence of positive spillover effects on a larger scale. Efforts should be directed toward guiding large cities to transfer resources to neighboring cities in a rational and orderly manner through industrial relocation, joint park development, and enclave economic models, thereby achieving expanded resource sharing, deepened urban cooperation, the effective allocation of factors such as labor, and optimization of the urban–rural income distribution structure.

Cities also ought to consider reasonably delimiting the spatial scope of urban agglomeration integration zones. Under the constraint of the “spatial decay” rule governing factor mobility and urban cooperation, there may exist an “optimal boundary” for the spatial scope of urban agglomerations. The escalating cooperation costs associated with a sharp increase in the number of cities are significant factors constraining the unlimited expansion of urban agglomerations, often limiting the sustainable development capacity of rural–urban migrant populations. Studies based on spatial spillover effects have found that as the scope of urban agglomerations expands and the distance from central cities increases, the spatial spillover effects decrease significantly [35,36,68,71]. Therefore, the spatial scope of urban agglomerations should be reasonably and scientifically delimited to establish an “optimal boundary” based on regional development endowments and actual conditions. Policy makers should consider promoting the coordinated development of the breadth and depth of urban agglomeration integration on this basis. Leveraging the efficiency-guiding effect of the market’s “invisible hand” and actively exerting the regulatory role of the government’s “visible hand” is essential to better balance market and government forces [33,35]. This involves implementing targeted policies through multiple measures to promote the high-quality development of urban agglomerations and coordinated urban–rural integration.

Certainly, this research admits room for enhancement. Urban agglomeration integration, a dynamic and multifaceted evolutionary process, influences the urban–rural income gap through a variety of factors. Our study primarily focuses on the impact of joining the YRD Urban Economic Coordination Council on this gap, neglecting subsequent specific actions such as city cooperation. Furthermore, the evolution of the urban–rural income gap is influenced by complex factors and manifests in diverse ways; our analysis measures this gap solely from an income perspective, which constitutes a somewhat simplistic approach. Due to limitations in data availability and research scope, the quantitative research on certain theoretical mechanisms requires further deepening. As relevant data accumulate and improve, addressing these issues will be crucial for future in-depth exploration and research. Additionally, although the empirical section of this study has elaborated on the necessity and rationale for selecting data spanning from 2000 to 2019, given the dynamic nature of the urban–rural income gap or indicators of common prosperity, exploring avenues to optimize the research design to incorporate a longer and more updated time frame represents a worthwhile direction for future endeavors.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.L. and W.W.; methodology, M.L. and W.M.; software, M.L.; validation, M.L., W.W. and W.M.; formal analysis, M.L.; investigation, M.L. and Y.J.; resources, W.W.; data curation, Y.J.; writing—original draft preparation, W.W.; writing—review and editing, M.L.; visualization, W.M. and Y.J.; supervision, M.L.; project administration, M.L.; funding acquisition, M.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities, grant number B230207051.

Data Availability Statement

We have provided a detailed introduction to the data sources. Of course, data will be made available on request.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our gratitude to the journal editors and anonymous reviewers for their valuable suggestions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Chancel, L.; Piketty, T. Global income inequality, 1820–2020: The persistence and mutation of extreme inequality. J. Eur. Econ. Assoc. 2021, 19, 3025–3062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.X.; Jv, Y.Q. Revisiting income inequality among households: New evidence from the Chinese Household Income Project. China Econ. Rev. 2023, 81, 102039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Wang, F.; Chen, J.; Zhang, Y. The income gap between urban and rural residents in China: Since 1978. Comput. Econ. 2018, 52, 1153–1174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- China Statistical Yearbook (CSY). 2024. Available online: https://www.stats.gov.cn/sj/ndsj/2024/indexch.htm (accessed on 19 November 2024).

- Zhang, W.; Bao, S. Created unequal: China’s regional pay inequality and its relationship with mega-trend urbanization. Appl. Geogr. 2015, 61, 81–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Zheng, X.; Wang, Y.; Bi, G. A multidimensional investigation on spatiotemporal characteristics and influencing factors of China’s urban-rural income gap (URIG) since the 21st century. Cities 2024, 148, 104920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S. Understanding China’s road to common prosperity: Background, definition and path. China Econ. J. 2023, 16, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, L. Bodies, visions, and spatial politics: A review essay on Henri Lefebvre’s The Production of Space. Environ. Plan. D Soc. Space 1995, 13, 609–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mace, A. Spatial capital as a tool for planning practice. Plan. Theory 2017, 16, 119–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gottdiener, M. A Marx for our time: Henri Lefebvre and the production of space. Sociol. Theory 1993, 11, 129–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheppard, E. Geographical political economy. J. Econ. Geogr. 2011, 11, 319–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradshaw, Y.W. Urbanization and underdevelopment: A global study of modernization, urban bias, and economic dependency. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1987, 52, 224–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castells, M. Grassrooting the space of flows. Urban Geogr. 1999, 20, 294–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Hu, X. The common prosperity effect of rural households’ financial participation: A perspective based on multidimensional relative poverty. Front. Public Health 2024, 12, 1457921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y.; Wang, M.; Zhu, Y.; Huang, X.; Xiong, X. Urbanization’s effects on the urban-rural income gap in China: A meta-regression analysis. Land Use Policy 2020, 99, 104995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Q.; Li, Y.; Si, H. Digital economy development and the urban–rural income gap: Intensifying or reducing. Land 2022, 11, 1980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, T.; Han, J. The effect of industrial structure adjustment and economic development quality on transitional China’s urban–rural income inequity. Front. Environ. Sci. 2023, 11, 1084605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.H.; Kang, K.H. The interaction effect of tourism and foreign direct investment on urban–rural income disparity in China: A comparison between autonomous regions and other provinces. In Current Issues in Asian Tourism: Volume II; Routledge: London, UK, 2021; pp. 204–217. [Google Scholar]

- Song, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, B.; Su, J. The influence of foreign direct investment on the urban–rural income gap: Evidence from China. Kybernetes 2022, 51, 466–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Piesse, J. Inequality and the urban–rural divide in China: Effects of regressive taxation. China World Econ. 2010, 18, 36–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Q.M.; Wei, Y.M. Distributional impacts of taxing carbon in China: Results from the CEEPA model. Appl. Energy 2012, 92, 545–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- YU, L.R.; LI, X.Y. The effects of social security expenditure on reducing income inequality and rural poverty in China. J. Integr. Agric. 2021, 20, 1060–1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Tan, S.; Yang, S.; Lin, Q.; Zhang, L. Urban-biased land development policy and the urban-rural income gap: Evidence from Hubei Province, China. Land Use Policy 2019, 87, 104066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, H.; Zhao, P.; Hu, H.; Zeng, L.; Wu, K.S.; Lv, D. Transport infrastructure and urban-rural income disparity: A municipal-level analysis in China. J. Transp. Geogr. 2022, 99, 103292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.A.; Alam, K.; Taylor, B. Measuring the concentration of information and communication technology infrastructure in Australia: Do affordability and remoteness matter? Socio-Econ. Plan. Sci. 2020, 70, 100737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Yin, Z.; Pang, S.; Li, Z. Does Internet development affect urban-rural income gap in China? An empirical investigation at provincial level. Inf. Dev. 2023, 39, 107–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Yang, R. Production and reconstruction mechanism of consumption spaces in urban fringe areas under capital intervention: Evidence from Guangming town in Shenzhen. J. Rural Stud. 2024, 108, 103307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McFarland, C.K.; Grabowski, E.H. Local employment impacts of connectivity to regional economies: The role of industry clusters in bridging the urban-rural divide. Econ. Dev. Q. 2022, 36, 317–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Chen, Z.; Hu, B.; Zhu, D. Do Regional Integration Policies Promote Integrated Urban–Rural Development? Evidence from the Yangtze River Delta Region, China. Land 2024, 13, 1501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, A.B. The May 2004 enlargement of the European Union: View from two years out. Eurasian Geogr. Econ. 2006, 47, 635–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Holod, D.; Reed III, R.R. Regional spillovers, economic growth, and the effects of economic integration. Econ. Lett. 2004, 85, 35–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boix, R.; Trullén, J. Knowledge, networks of cities and growth in regional urban systems. Pap. Reg. Sci. 2007, 86, 551–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.L.; Li, P.X.; Li, L.X. Government cooperation, market integration and economic performance of city cluster: Evidence from the Yangtze River Delta urban economic coordination committee. China Econ. Q. 2017, 16, 1563–1582. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Liu, N.Q.; Wu, Y. Can the enlargement in Yangtze River Delta boost regional economic common growth. China Ind. Econ. 2017, 6, 79–97. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Yan, D.; Sun, W. The Economic Growth Effect of Urban Agglomeration Integration Promoted by Government Cooperation: An Empirical Study Based on the Yangtze River Delta. Nanjing Soc. Sci. 2023, 3, 40–51. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Han, J.; Gao, M.; Sun, Y. Research on the measurement and path of urban agglomeration growth effect. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pomerlyan, E.; Belitski, M. Regional integration and economic performance: Evidence from the Eurasian Economic Union. Eurasian Geogr. Econ. 2024, 65, 627–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bornschier, V.; Herkenrath, M.; Ziltener, P. Political and economic logic of western european integration A study of convergence comparing member and non-member states, 1980–1998. Eur. Soc. 2004, 6, 71–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crespo Cuaresma, J.; Ritzberger-Grünwald, D.; Silgoner, M.A. Growth, convergence and EU membership. Appl. Econ. 2008, 40, 643–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos-Paulino, A.U.; DiCaprio, A.; Sokolova, M.V. The development trinity: How regional integration impacts growth, inequality and poverty. World Econ. 2019, 42, 1961–1993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beckfield, J. Remapping inequality in Europe: The net effect of regional integration on total income inequality in the European Union. Int. J. Comp. Sociol. 2009, 50, 486–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezcurra, R.; Rodríguez-Pose, A. Does economic globalization affect regional inequality? A cross-country analysis. World Dev. 2013, 52, 92–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charron, N. Diverging cohesion? Globalisation, state capacity and regional inequalities within and across European countries. Eur. Urban Reg. Stud. 2016, 23, 355–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iammarino, S.; Rodriguez-Pose, A.; Storper, M. Regional inequality in Europe: Evidence, theory and policy implications. J. Econ. Geogr. 2019, 19, 273–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beckfield, J. European integration and income inequality. Am. Sociol. Rev. 2006, 71, 964–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busemeyer, M.R.; Tober, T. European integration and the political economy of inequality. Eur. Union Polit. 2015, 16, 536–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, K.R. Globalisation, competition and the politics of local economic development. Urban Stud. 1995, 32, 213–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, D.; Sun, W.; Li, P.; Liu, C.; Li, Y. Effects of economic growth target on the urban–rural income gap in China: An empirical study based on the urban bias theory. Cities 2025, 156, 105518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]