Abstract

Edible green infrastructure provides a pathway to enhancing food security and advancing sustainability in underprivileged Sub-Saharan communities. This study explores the potential of modular living wall systems (LWSs) with African Vegetables (AVs) to enhance food security and provide ecosystem services in the Melusi informal settlement, Tshwane, South Africa. This research investigated the socio-cultural perceptions surrounding the opportunities and challenges of outdoor modular living walls with African Vegetables to sustainably enhance the household food security of marginalized South African urban communities. Data were captured using a mixed-methods approach that involved semi-structured questionnaires, focus group interviews, and photo-elicitation. The analysis was conducted quantitatively with SPSS and qualitatively with Atlas.ti software. Key barriers to urban agriculture identified include high maintenance costs, pest control issues, spatial constraints, exposure to extreme weather, and limited access to water and fertilizers. The Melusi community strongly supported LWSs with AV crops, valuing their space-saving and biophilic benefits. Success, however, depends on low-tech, cost-effective, modular systems made from recycled materials and incorporating nutrient-dense, compact crops. This study highlights the potential of LWSs to enhance food security, promote economic growth, and support climate-resilient livelihoods in urban underprivileged settings.

1. Introduction

Global challenges like food security, climate change, poverty, and rapid urbanisation are fundamentally interconnected, demanding innovative systemic solutions such as sustainable urban food production [1,2]. Edible green infrastructure is increasingly recognized for its potential to address climate change and public health concerns, particularly in developing countries with more prevalent severe food insecurity [3,4]. A holistic, socially just approach to global food systems is crucial for sustainability [5,6]. Malnutrition, hunger, and poverty are closely linked [4], with food insecurity disproportionately affecting women and impacting 690 million people annually [7]. Compounding this, food systems are a major driver of greenhouse gas emissions [7], underscoring the need to reduce food waste and improve agricultural sustainability to achieve food security within planetary boundaries [8].

We argue that edible green infrastructure (EGI), as a system-wide approach, can make a meaningful contribution to advancing sustainable development, which is currently perceived as vague, non-urgent, and exacerbating inequality [9]. Food security and nutrition are indicative of poverty [4], with repercussions for people in terms of health and well-being, gender equality, responsible consumption, and for cities in terms of economic growth, sustainability, climate action, and land preservation [10]. Against this background, this study examines the contribution of EGI to improve livelihoods.

Research on socio-cultural perception related to green infrastructure has increased in the literature over the past couple of decades. Green space availability has emerged as one of the most significant environmental factors associated with physical and mental health outcomes in urban neighborhoods [11]. Where perception studies aligned with ecosystem services have been conducted on municipal open space systems [12]; public green spaces [13,14]; health clinic gardens [15] and urban foraging [16], fewer studies focus on edible green infrastructure or green wall systems specifically. The research examines the perceptions of stakeholders in an informal settlement regarding the implementation of modular living wall systems incorporating African Vegetables. The central research question driving this study is: What opportunities and challenges do outdoor modular living walls, which produce African Vegetables, present for sustainably enhancing the household food security of underprivileged urban communities?

This study provides an overview of the opportunities and challenges faced by a marginalized community in the City of Tshwane, South Africa, in growing African Vegetables (AVs) in modular living wall systems (LWSs). The findings provide a foundation for advancing sustainable urban agriculture as part of a greater quest for more sustainable development and living.

1.1. Living Walls as a Potential Urban Agriculture Solution at a Household Scale

Living wall systems (LWSs) are vertical planting platforms integrated into a building’s façade [17], consisting of structural components supporting plants rooted in a growing medium and sustained by a dedicated water system [18]. Living walls provide ecosystem services that address key urban challenges and advance sustainable development objectives [15]. These benefits, derived from the natural environment, also support human well-being [19]. Specific services identified by research include cooling [18,20,21], air purification [19], noise reduction [20], carbon dioxide absorption and oxygen production [20] and biodiversity enhancement [21]. Additionally, LWSs have been argued to provide biophilic value, improved urban aesthetics, and enhanced mental well-being [22].

The benefits of LWSs integrated as EGI in urban agricultural practices to provide provisioning ecosystem services through directly supporting urban food production have only recently emerged in research [23,24,25]. Edible green infrastructure is a planned, multifunctional natural network that not only provides the widely recognized ecosystem benefits of green infrastructure, but sustains and enhances local food production in urban environments [26].

Urban small-scale food production holds potential for enhancing household food security, but also presents challenges related to income, health, and well-being. Raj et al. found that urban agriculture benefited communities by demonstrating a strong correlation between vegetable consumption, gender, and income; however, it had not yet succeeded in fostering healthy eating behaviours among youth [27]. However, small-scale urban agriculture has the potential to improve gender equality by engaging local communities and empowering women as subsistence producers [28,29]. By utilizing vertical spaces, these agricultural innovations help women overcome traditional land access barriers while contributing to household food security and personal economic agency. However, these initiatives must adopt a systemic approach to make a meaningful contribution to food security, economic growth, and gender inequality, as poverty and inequality restrict access to nutritious food. Edible LWSs could support climate action by reducing greenhouse gas emissions, food miles, and waste [30]. These edible living walls also optimise underutilized urban spaces, lessen reliance on conventional agriculture, and enhance biodiversity [21,31]. While research highlights the potential of edible LWSs as EGI, studies on their adoption within communities remain limited. Concerns often revolve around high costs and maintenance [32] along with skepticism about their actual food output and quality [33].

1.2. Modular Living Walls with Leafy African Vegetables in Low-Income Communities

To overcome the cost and maintenance barriers, modular LWSs should be developed to meet local needs, offering a more cost-effective and space-saving solution, particularly vital for developing countries. These systems can be highly resilient, making them ideal for vertical gardening in developing countries due to their low-tech nature and ability to withstand interruptions in utility supplies [25,34]. In South Africa, these systems, which mostly feature planting trays or bags affixed to vertical structures [17,35], are widely used for their aesthetic benefits [36]. The modularity allows for off-site pre-growing and simple replacement, offering both practical and aesthetic appeal. Effective deployment necessitates carefully integrating the wall structure, water harvesting capabilities, irrigation methods, and optimal plant selection [35,37].

The need for LWSs to improve cost efficiency, reduce maintenance and carbon footprint [38], has been pressing. Such developments and improved design would enhance resilience to support edible urbanism [39]. A six-month experimental study comparing two modular LWSs and nine AVs [34] developed a framework for LWSs, building on previous research to improve cost-effective installation and maintenance [40,41]. Key recommendations include using locally sourced, recyclable materials, prioritizing lightweight and robust components, flexible sizing, and accessible heights for maintenance, as well as ensuring optimal sunlight exposure while addressing crop contamination in polluted areas [34]. The irrigation system should use low-tech solutions, such as drip or wick systems, with harvested water as the primary source.

Further attention to crops can advance LWSs. Given the stresses from shallow soil, the limited adaptability of plant species, and specific light, wind, and water requirements, selecting suitable plant species is crucial [42]. Additionally, crops must be resilient to extreme weather events, such as heatwaves, droughts, storms, and floods, as climate change intensifies these conditions [3,43].

In response, the exploration of AVs as living wall crops has been shown to provide agricultural alternatives that enhance diets [43,44]. African Vegetables, native or well-adapted to African climates and soils, are integral to local culture and cuisine and offer opportunities for developing nations by diversifying food production [45]. Their high nutritional value, low input requirements, and resilience to harsh conditions make them valuable for mitigating the effects of climate change on agriculture [45,46].

Integrating AVs into agricultural systems supports multiple sustainability objectives [43]. Specifically, considering their horizontal footprint compared to conventional soil-based agriculture, modular LWSs with selected AVs show potential to enhance household food security by achieving higher biomass yields, taking up a small space in dense urban environments [34]. Their feasibility for improving household food security can be further enhanced by locally manufactured modular LWSs that use drought-tolerant AVs irrigated by a drip system using harvested water, reducing energy use and transportation needs [6,25,34], all supporting a lower carbon footprint [26,34,39,47]. This approach supports edible urbanism as a system, advocating for integrating agriculture, nature, and ecology within urban design [39].

1.3. Production and Consumption of Leafy African Vegetables

Edible green infrastructure can increase health and well-being by making alternatives available, but these alternatives must be physically and socially accessible [48]. Consumption is strongly influenced by access and awareness. Households with access to vegetable gardens or fresh produce markets show higher consumption rates [49]. Furthermore, familiarity with AVs and their nutritional benefits has been shown to increase their use [50].

However, supply-side barriers and preferences persist. In South Africa’s Northwest province, limited crop availability was a key barrier to vegetable consumption [50]. A trend rooted in the post-colonial displacement of native crops has led to exotic vegetables being preferred over AVs, contributing to the neglect of the latter [51].

Logistical and demographic factors also play a critical role. Infrastructure has a modest but meaningful positive impact on the quality of life for low-income urban households; notably, electricity is required for cold storage and shows a strong correlation with well-being [52]. Concurrently, water limitations can trigger adaptive physiological responses, while extensive drought impairs crop performance [53], underscoring the importance of selecting water-wise crops for production in densely populated, low-income communities. Additionally, evidence suggests nuanced, multifaceted demographic effects such as age and gender on food perceptions, with socio-economic factors (e.g., location, education, occupation, and income) playing a particularly robust role in shaping nutritional preferences [54].

Another factor impacting the uptake of AVs is the productivity challenges from climate variability, soil salinity and acidity, pests, diseases and inefficient agricultural practices [55]. Research and genetic improvement efforts focus on exotic crops, leaving AVs underexplored [56]. In South Africa, AVs are primarily traded informally or foraged [57]. Factors influencing AV acceptance include availability due to seasonality [58] and accessibility [57], recipe accessibility and ease of preparation [58], taste [59], and the location of consumers, with a higher acceptance amongst rural communities [60] and visual appeal [61].

This study offers further insight into LWSs with AVs as a potential sustainable urban agriculture alternative, specifically examining their lived and perceived performance and appeal for potential adoption by local communities. Living wall systems with AVs offer a compact, high-density cultivation option that is well-suited to the space constraints of densely populated urban settlements. Furthermore, the focus on AVs is crucial for providing a culturally relevant food source that directly addresses dietary diversity and food security prevalent in informal settlements. Thus, by combining the space-efficient benefits of LWSs with the food security benefits of AVs, the study proposes a sustainable approach to enhancing household food security. Considering the socio-cultural uptake of these systems and crops, provides a unique contribution to understanding systemic sustainability and small, practical steps to operationalize it [62].

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area and Site

The study focuses on Gauteng, South Africa’s most urbanized and densely populated province, as the research context. Tshwane was selected as the study area for its significant urbanization challenges, including poverty, unemployment, and poor education and health, exacerbating food insecurity [10,63]. These socio-economic factors make Tshwane a representative area for studying food insecurity in urbanized regions of sub-Saharan Africa. Tshwane, located in a monsoon-influenced humid subtropical climate zone (Cwa), receives an annual rainfall of approximately 580 mm and temperatures range from a minimum of 5 to 7 °C and a maximum of 28 to 30 °C [64,65].

The study site was the Melusi informal settlement near a disused, water-filled quarry west of Tshwane [66]. Melusi was selected due to its high population density, lack of formal planning and infrastructure, and widespread poverty, with residents lacking access to essential services such as electricity, water, and sanitation. The settlement consists of densely packed dwellings with narrow, unsurfaced roads and informal housing structures made from corrugated iron, wood, plastic sheeting and other salvaged materials (Refer to Figure 1). These conditions expose residents to flooding, dust, and extreme heat [66]. Melusi’s population grew from approximately 27,000 in 2011 to around 40,000 by 2023 [67].

Figure 1.

The study area, the Melusi informal settlement, located in Tshwane, in the Gauteng province of South Africa. (a) The Melusi informal settlement features densely grouped dwellings built from corrugated iron, timber, plastic coverings, and various reclaimed materials with narrow, unpaved streets. (b) Melusi residents are exposed to flooding, dust and extreme heat. (Source: Botes, 2024 [68]).

2.2. Research Design

An inductive, exploratory research approach was employed, as limited research is available on the perceptions of South African communities regarding Living Wall Systems (LWSs) and African Vegetables (AVs). This approach enables the collection of foundational data to inform future research through a mixed-methods approach [69]. The mixed-methods approach comprised semi-structured questionnaires and semi-structured interviews with focus groups. The initial stage of the research (2023) used photo-elicitation to introduce unfamiliar concepts. Subsequently, the researchers built a LWS and planted AVs in 2024 at the local youth centre to provide the community with a practical, familiarizing example of growing AVs in a LWS. The integrated qualitative and quantitative data collection and analysis enabled more robust and comprehensive results [70].

2.3. Sample Size

To ensure the representativeness of the community during the 2023 data collection period, the study area was stratified into three distinct geographic regions: the central area, the eastern area, and the western area of the settlement. An equal number of participants aged 18 and older were then randomly selected from the main thoroughfares of each of these three regions over a three-day period during April and May 2023. The Living Wall System (LWS), built on-site and planted with African Vegetables (AVs), served as a practical example for the study. Subsequent data collection in 2024 focused on youth, involving staff participants from the community youth centre and Early Childhood Development (ECD) centres—which care for children from birth up to four years of age [71]. These centers were selected because previous research indicates that a child’s eating preferences are significantly influenced by their family, ethnic, and social environments [72]. Therefore, youth centre and ECD staff were considered key indicators of community perceptions, with focus groups held at the youth centre, and semi-structured interviews held following purposive sampling of ECD staff. Seven of the eight Early Childhood Development Centres (ECDs) in Melusi participated in the semi-structured interviews, and seven youth centre staff members attended the focus groups. This sample size was deemed representative of the Melusi community, as only one ECD chose not to participate.

2.4. Data Collection

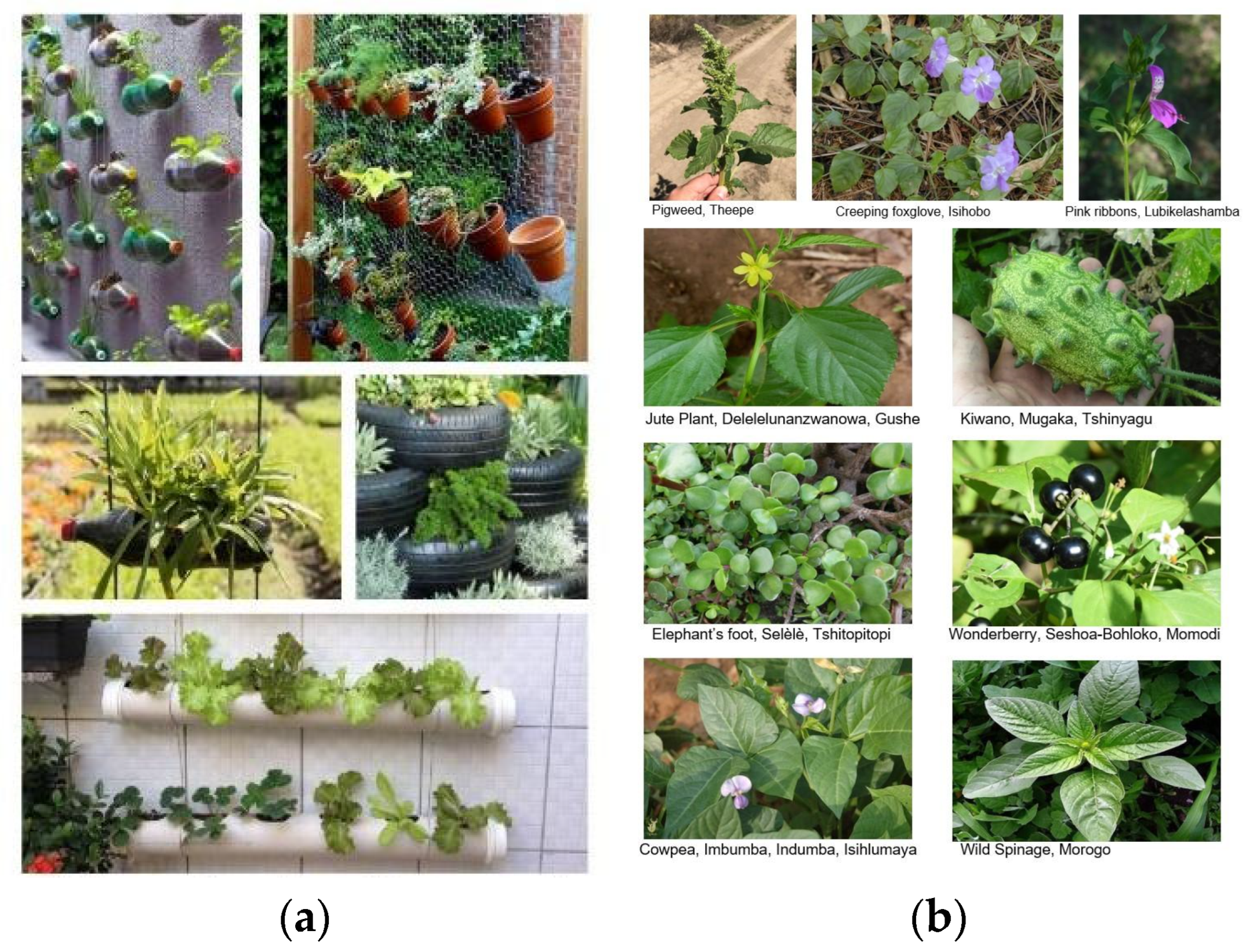

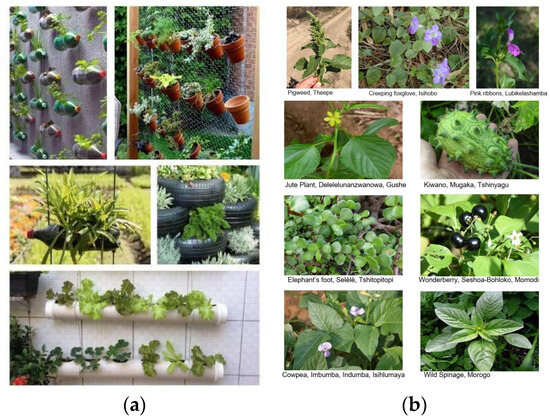

Data on the Melusi community’s perceptions of AVs and LWSs were collected over a two-year period. The first stage involved semi-structured questionnaires on 3 and 17 May 2023. The questions were categorized into biographical information to enhance understanding of any links between the participants’ backgrounds and their involvement in urban agriculture, as well as their openness to cultivating crops in outdoor living walls, and their consumption of vegetables and AVs (refer to Supplementary Materials File S1 for the questionnaire). The researchers explained LWSs and AVs through photo-elicitation, depicting LWSs and AVs in comparison to exotic vegetables and conventional food production (See Figure 2). To mitigate bias and avoid an immediate positive response toward LWSs and AVs, the researchers first provided verbal explanations when participants indicated unfamiliarity with the concepts. The photos were then shown to supplement these explanations. The LWS images featured a range of interventions, primarily utilizing recycled materials common in informal settlements. The AV photos included nine species familiar to the geographic area. The survey questions were posed in an open-ended and neutral manner, while the subsequent focus group discussions allowed for multiple perspectives to be discussed.

Figure 2.

The photo-elicitation documents illustrating living wall systems (a) and African Vegetables (b) to the Melusi community during the 2023 surveys. (Source: De Kock, 2023 [73]).

Data collection techniques included open-ended questions to gather qualitative data (reasons and motivations) and closed-ended questions to obtain quantitative data (functional information and facts). Biographical inquiries were designed as closed-ended questions, consisting of six items that sought details on age range and gender, country of origin, duration of residency in South Africa, as well as professional and income classifications. Inquiries about urban agriculture (UA) and participants’ willingness to cultivate vegetable crops in living walls featured five closed-ended questions regarding their personal engagement in UA, the advantages and obstacles of growing vegetables in living wall systems (LWSs), their main difficulties in practising UA, and whether they purchased vegetables from stores. Open-ended questions explored participants’ involvement in UA, their reasons for participating, and the variety of vegetables they cultivate.

During the second stage of the study, on 24 April 2024, the research team, in collaboration with the staff of the Melusi Youth Centre, established two modular LWSs and planted AV seedlings (see Figure 3). The LWSs were constructed by dry-stacking bricks made from a polystyrene aggregate and cement mixture. Black seed trays with an 8-litre capacity were fitted into the openings between the bricks. To ensure sufficient aeration, these trays were filled with a potting soil, river sand, and perlite soil mixture in a 1:4:1 ratio [34].

Figure 3.

The living walls at the Melusi Youth Centre feature a low-tech, locally developed outdoor system that utilises interlocking lightweight blocks composed of a mixture of recycled polystyrene aggregate and cement. African vegetable seedlings were planted in black seed trays that hold the growth medium and the plants. The living walls were not irrigated. (Source: Botes, 2024 [68]).

This construction approach enabled direct community involvement in installation and maintenance, leading to more informed responses during focus groups and semi-structured interviews. Due to the study’s autumn timeframe, crop selection was limited to cool-season vegetables. Based on criteria including seasonality, seedling availability from the research organization, and the youth centre staff’s familiarity with the crop, non-heading Chinese cabbage (Brassica rapa subsp. Chinensis) was selected as the representative African Vegetable (AV). This crop is commonly grown and sold in the study area and the informal settlements of the Vhembe District, Limpopo province, South Africa [74]. The Chinese cabbage in the LWS was manually watered and maintained by the youth centre staff following construction. Researchers conducted weekly visits to monitor for issues such as pests and diseases.

Once the AV crop was ready for harvest after four weeks, the participants, comprising staff from the ECD and youth centres, were purposively selected for data collection. Data collection involved focus groups at the youth centre and semi-structured interviews (refer to Supplementary Materials File S2 for the Question list) with ECD staff members on 27 May 2024 to gather participants’ opinions and experiences by posing carefully developed questions [75]. The survey was structured to collect data across seven key areas. Biography details captured staffing numbers, meals provided, daily attendance, age ranges, spoken languages, and operating hours (during school terms and school holidays). Questions on current infrastructure and living conditions assessed the availability, source, and consistency of electricity and water, as well as food storage methods and appliances, pest issues, and waste disposal/recycling processes. The health and well-being section explored local environmental challenges (dust, flooding, heat), cleaning product usage, leisure activities, access to and use of open green spaces, and observed local biodiversity. Food security inquiries focused on school meal provision (including vegetable content) and children’s consumption of breakfast and dinner at home. Economic factors investigated vegetable sourcing, the presence of local fresh produce markets, and the community’s willingness to dedicate time and funds to a vegetable garden. The section on urban food production assessed existing knowledge and interest in growing African Vegetables (AVs) using Living Wall Systems (LWSs), encompassing nutritional knowledge, preparation, maintenance (including the use of pesticides/fertilizers), and willingness to consume AVs or utilize community gardens. Finally, a section on opportunities and barriers evaluated the installation and maintenance of AVs in LWSs, covering successes, failures, user reactions, staff/learner experience, comparisons to commercial vegetable growth, preferred future gardening methods, and the feasibility of using the harvest in meal preparation. All interviews and focus groups were recorded with the participant’s consent.

The study adhered to the ethical protocols of the University of Pretoria (Reference EBIT 28/2023, dated 20 April 2023, and EBIT 11/2024, dated 2 April 2024).

2.5. Data Analysis

The study involved quantitative and qualitative analysis. The semi-structured questionnaires provided quantitative data, which were analyzed using descriptive methods to identify patterns, summarize data, and examine frequencies and inferential methods to explore trends and relationships among variables [34,70]. Questionnaire responses were manually coded and transferred into a Microsoft Excel (v16.0) spreadsheet, and numerical values corresponding to responses were entered. The data were imported into IBM SPSS Statistics (v28.0.1.0) for statistical analysis. The study employed a Pearson correlation coefficient test to analyze the relationships between demographic factors and the community’s perceived opportunities and challenges. A 95% confidence interval (p < 0.05) was applied to assess statistically significant correlations [10].

Interview transcriptions were completed using Microsoft 365 (v2405) and manually verified for accuracy before being coded in Atlas.ti (v24) software. The qualitative data from semi-structured interviews and focus groups were first deductively analyzed to generate the first set of codes using thematic analysis to identify patterns and themes aligned with the theoretical framework and research questions [76,77]. This was followed by refining and merging the initial codes during the second coding cycle and logically grouping them to derive themes.

3. Results

The study’s findings are structured to address the research question and are presented under three themes. First, participants’ demographic characteristics, living conditions, and environmental context are outlined. Next, the perceived opportunities and challenges related to African vegetable consumption, cultivation, and the use of living walls as EGI are presented.

3.1. Characteristics of Living Conditions of Study Participants

Table 1, Table 2 and Table 3 summarize the descriptive statistics for the 2023 interviews. The sample group reveals significant socio-economic vulnerability, with the majority of participants (59%) being unemployed. Of those employed, a large majority (81%) reported earning less than the minimum hourly wage of $1.40 (ZAR 25.42) as of 2023 [77]. The sample was heavily skewed toward female respondents (73%). The majority (66%) of the sample group were younger adults aged 20 to 39, with smaller proportions aged 40 to 49 (18%) and 50 or older (9%).

Table 1.

Income distribution of the sample group interviewed in 2023.

Table 2.

Age composition of the sample group interviewed in 2023.

Table 3.

Gender composition of the sample group interviewed in 2023.

Only 7% were under 20, as individuals under 18 were excluded from the study. Melusi’s ECDs serve 15 to 150 children, with 2 to 30 staff members per centre. None reported access to electricity or potable water, and 60% of participants noted a lack of green space. While most ECDs provide two meals daily, staff were uncertain about children’s evening meals. Significant environmental challenges include dust, heat, and flooding. No statistically significant correlation was found between demographic factors (age and gender) and socio-economic status (profession) on vegetable preference.

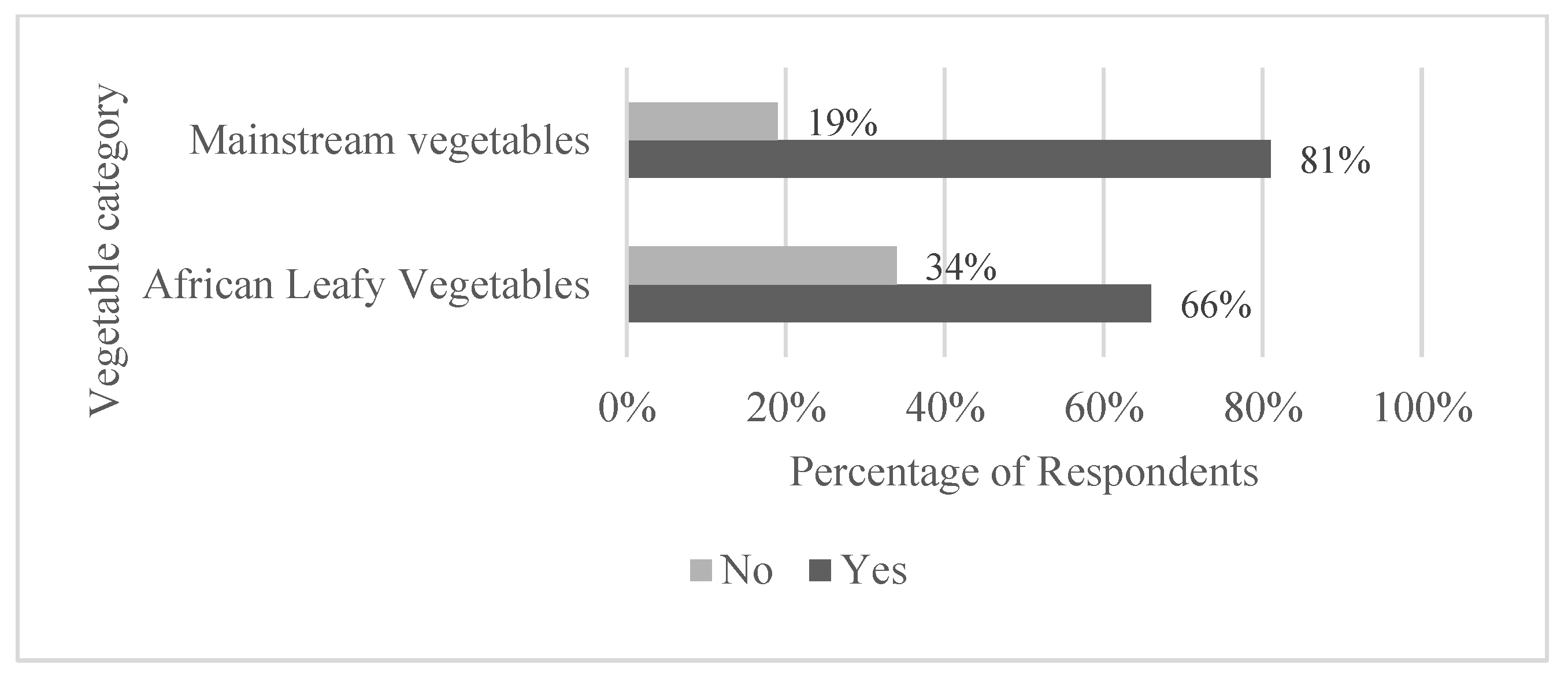

3.2. The Melusi Community’s Opportunities and Challenges Concerning the Consumption and Cultivation of African Vegetables

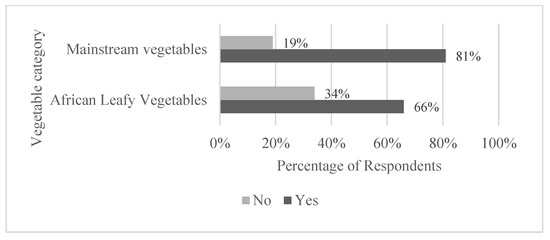

From the interviews and focus groups we verified that vegetables are a crucial component of the meals provided, with 90% of ECDs and youth centres including them daily. Nearly all respondents (94%) consume vegetables, with 66% purchasing from shops and 34% from markets or vendors, while ECDs and youth centres mainly sourced vegetables from local gardens. Over half of the ECDs and youth centres (60%) were familiar with AVs. However, mainstream vegetables were preferred, with 81% of respondents consuming them compared to 66% consuming AVs (refer to Figure 4). Staff from ECDs and youth centres indicated that most of the youth are open to eating AVs.

Figure 4.

Preferences for the consumption of African leafy Vegetables and conventional vegetables as identified by the Melusi community members from the interviews in 2023.

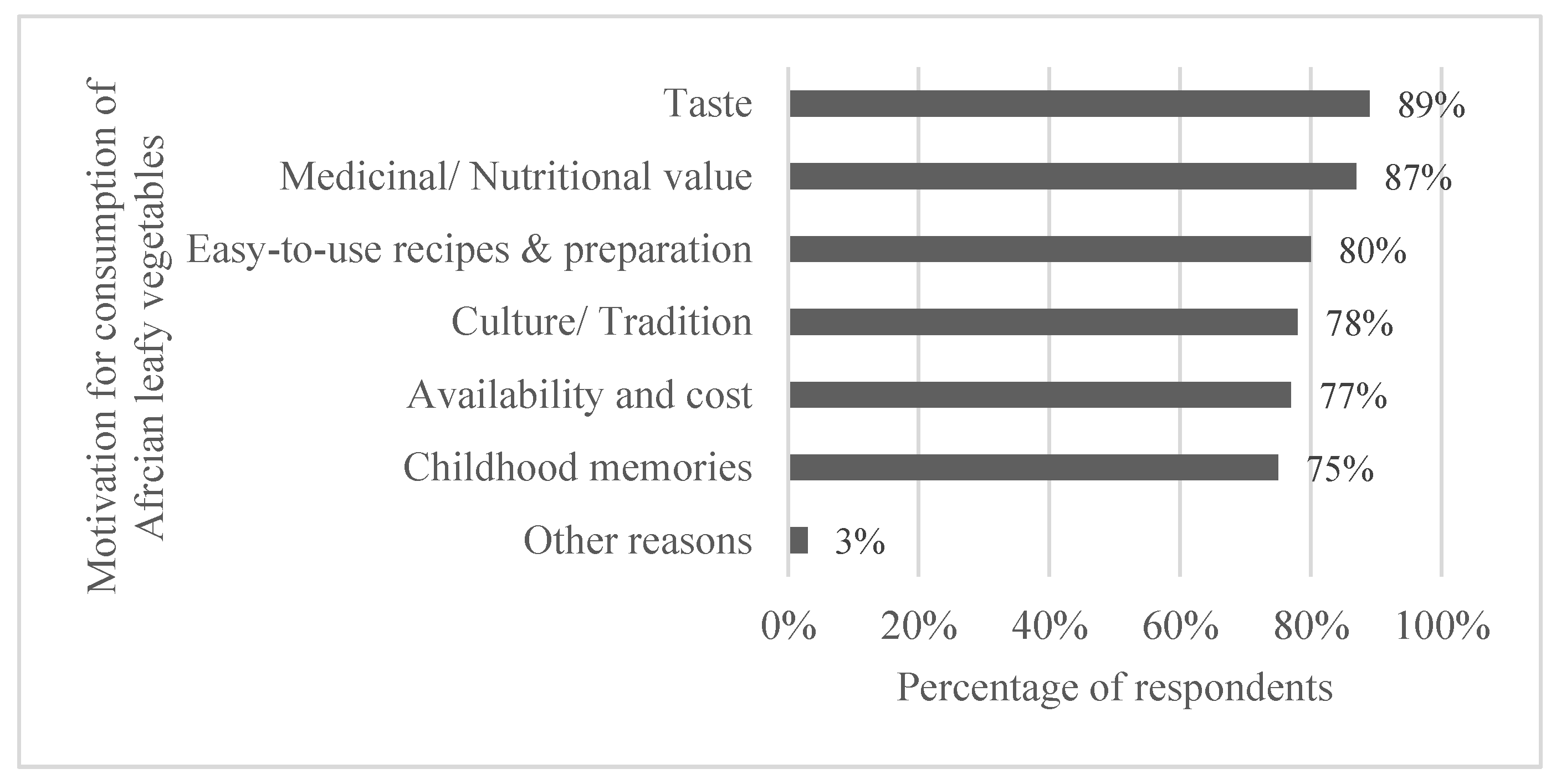

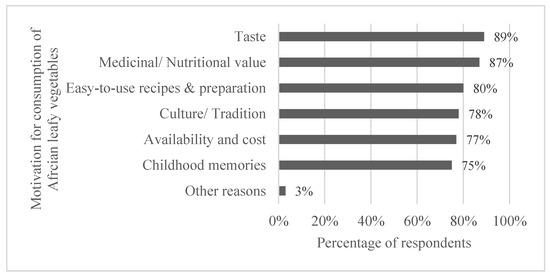

From the interviews, we verified that the conventional vegetables consumed included tomatoes, green beans, pumpkin, butternut, beetroot, cabbage, carrots, and spinach. African leafy vegetables mentioned during interviews included morogo (African spinach, made from amaranth, cowpea, and pumpkin leaves), gushe (Jute mallow), tseepe/thepe (Amaranth), spider plant (African cabbage), blackjack, and moringa. Motivations for consuming AVs included their nutritional value (87%), ease of preparation (80%), cultural significance (78%), affordability (77%), and associations with childhood memories (75%) (See Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Motivation for consuming African leafy vegetables as identified by the Melusi community members based on the interviews in 2023.

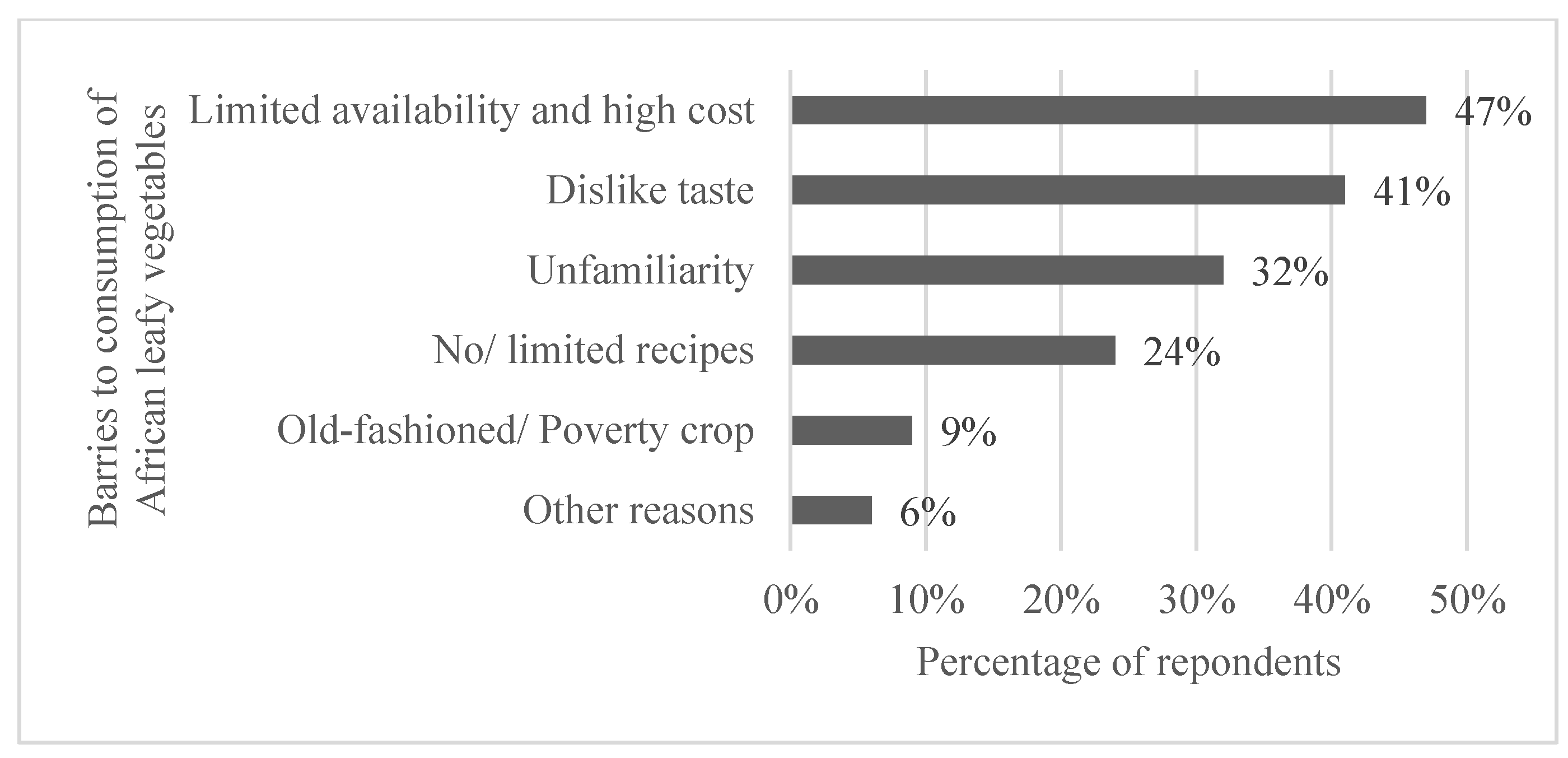

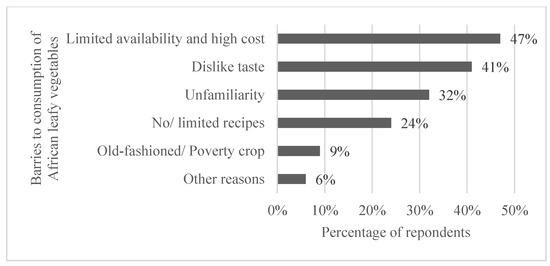

From interviews conducted with the community in 2023, we verified that barriers to AV consumption included cost and limited availability (47%), taste preferences (41%), a lack of familiarity (32%), and insufficient knowledge of preparation methods (24%). Smaller proportions of respondents avoided AVs due to perceptions of them as “old-fashioned” (9%) or for other reasons (6%) (refer to Figure 6). The ECDs and youth centres cited restricted access to recipes and limited availability as key obstacles.

Figure 6.

Barriers to consuming African leafy Vegetables as identified by the Melusi community members based on the interviews in 2023.

Over half of the community (55%) interviewed engaged in urban agriculture, primarily growing mainstream crops like spinach and cabbage, with fewer cultivating AVs. A Pearson correlation analysis comparing the frequency of participants across income categories who cited economic reasons (to sell vegetables) for growing vegetables showed a statistically significant negative relationship between household income and gardening for profit (r = −0.220, p < 0.05). This indicates that lower-income households exhibit higher motivation based on the economic benefits derived from vegetable sales.

Additionally, 75% of ECDs and youth centres were familiar with urban agriculture.

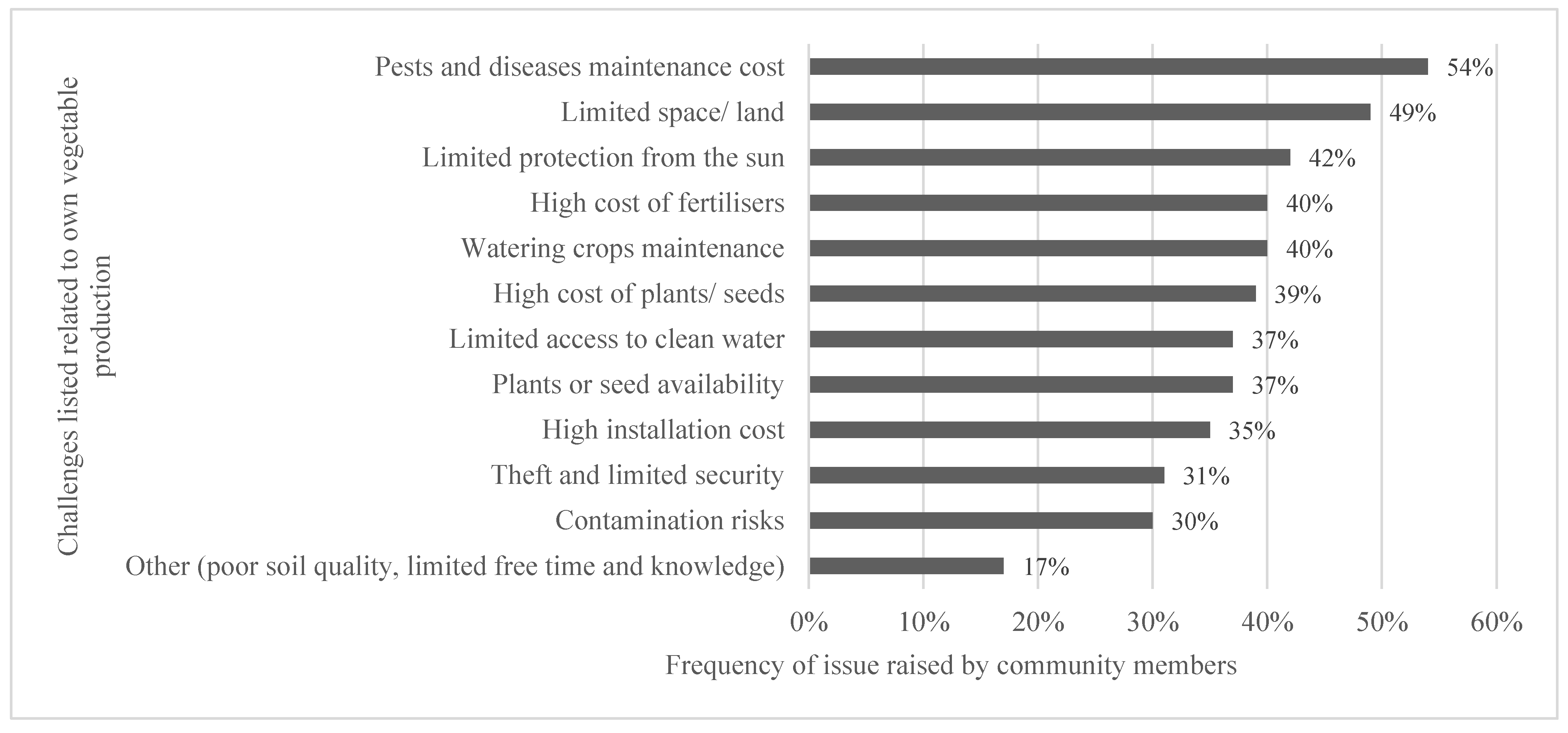

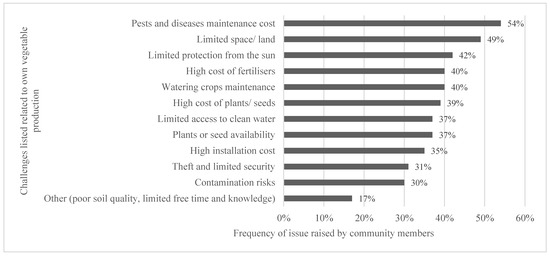

Community members identified high costs and resource management as the chief obstacles to cultivation. High maintenance costs (54%) were cited as the main barrier, stemming primarily from expenses related to pest control, fertilizers and water. Following this were physical constraints such as limited space and the need for sun protection. Further challenges included the cost and availability of seeds, as well as security and contamination risks (refer to Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Main challenges to the cultivation of their own vegetables identified by Melusi community members during 2023.

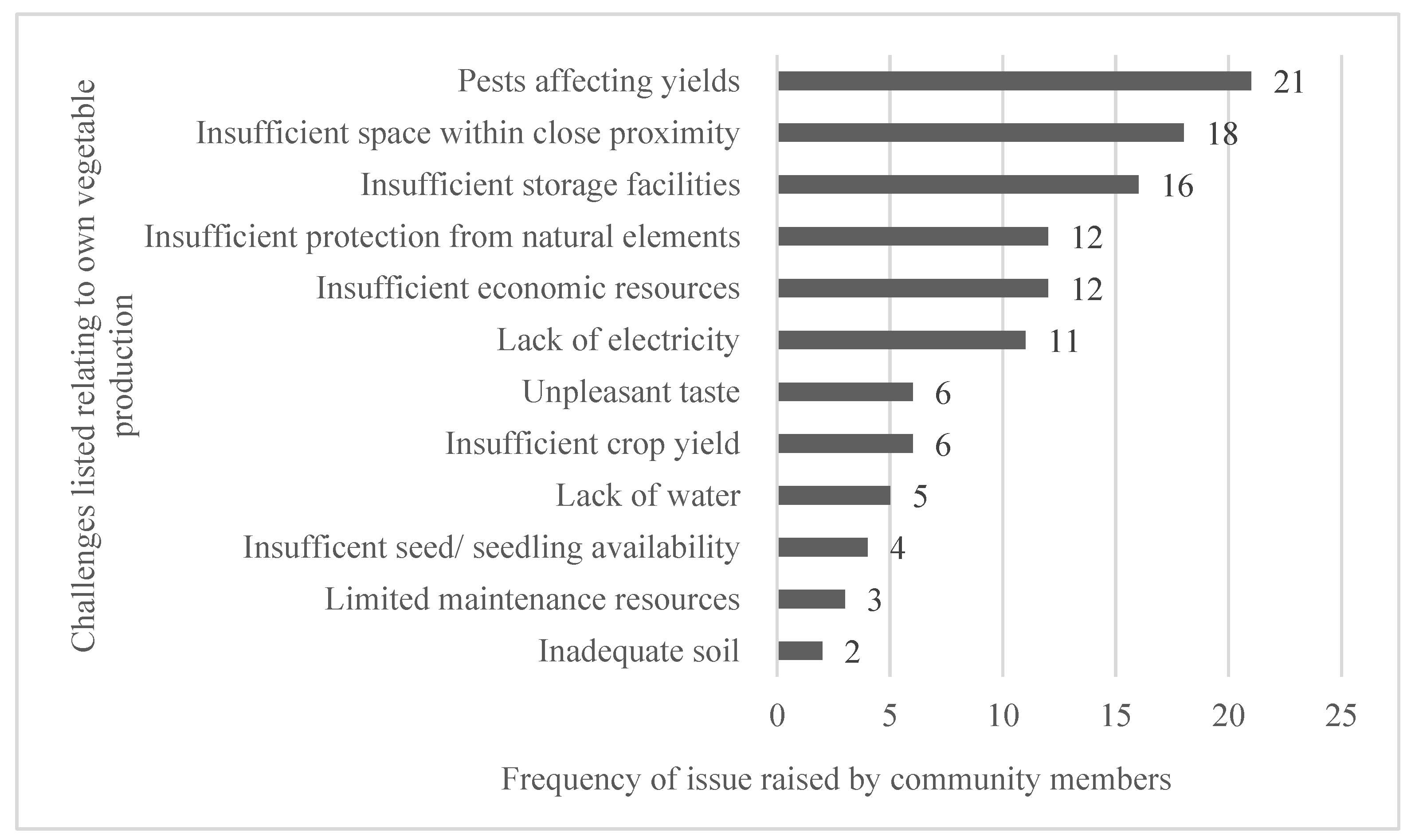

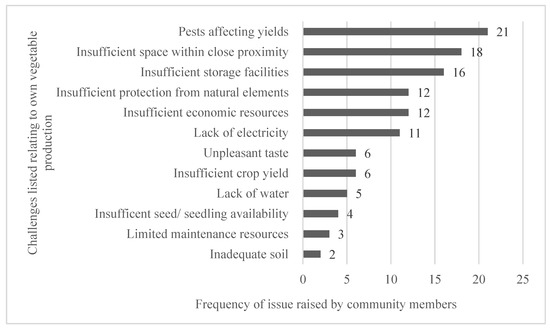

Early Childhood Development Centres (ECDs) and youth centres echoed concerns about pests, budget limitations, inadequate sun protection, and limited space. Additional challenges listed by ECDs included a lack of refrigerated storage, environmental factors such as flooding and a lack of access to electricity (refer to Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Main challenges to the cultivation of African leafy Vegetables identified by Melusi Early Childhood Development and Youth Centre staff during the focus groups in 2024.

3.3. The Melusi Community’s Opportunities and Challenges Concerning Using Living Walls as Edible Green Infrastructure

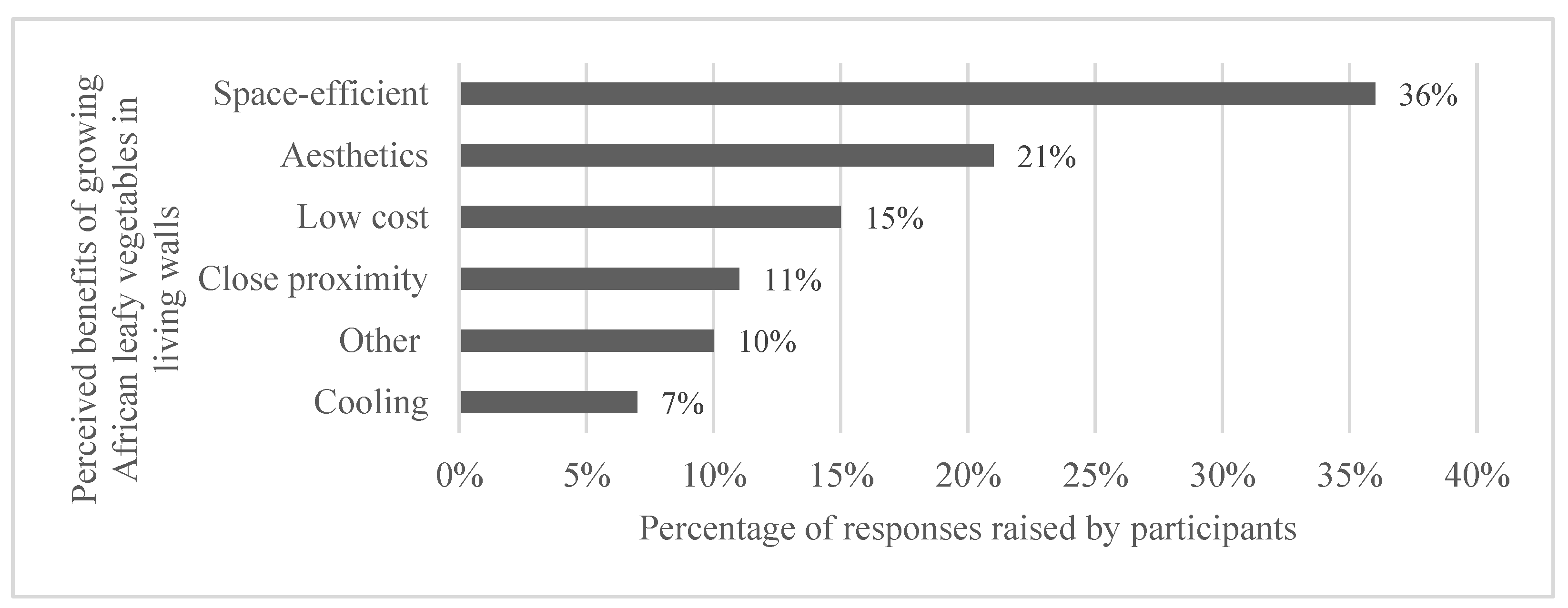

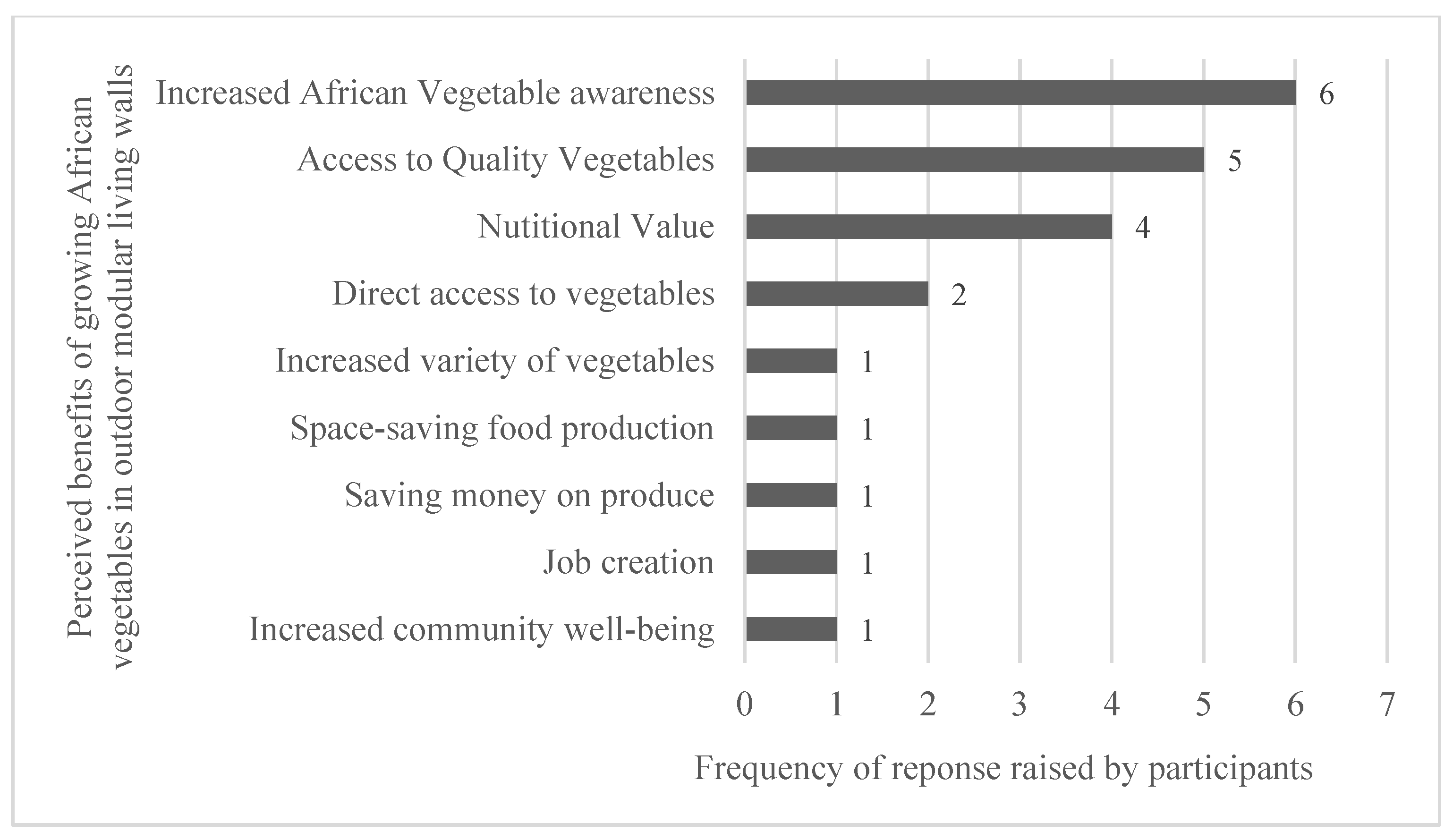

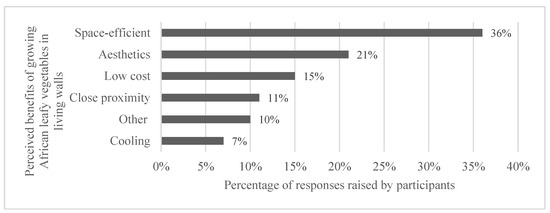

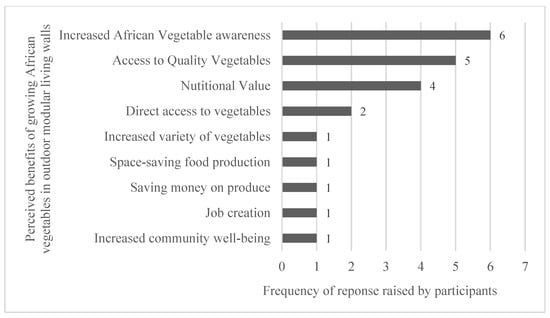

From the interviews with the community, we verified that most participants (72%) expressed interest in using LWSs as EGI for urban agriculture. However, participants raised concerns about the suitability of LWSs for certain crops, such as corn, which they deemed too large for the system. Additional reservations included the high implementation costs associated with LWSs. In contrast, participants favouring LWSs highlighted space-saving as the most significant advantage, a benefit also emphasized by ECDs (See Figure 9). Other benefits listed by participants include protection from animals, enjoyment, saving time and water, and the opportunity to use recyclable materials. Other benefits noted by ECDs and youth centres included the aesthetic appeal of LWSs and their positive impact on the well-being of staff and children through interaction with the system (See Figure 10).

Figure 9.

Opportunities identified by the community members from the interviews in 2023, related to the cultivation of African leafy Vegetables in outdoor modular living walls.

Figure 10.

Opportunities for cultivating African leafy vegetables in outdoor modular living walls that were frequently highlighted by the Melusi Early Childhood Development and Youth Centre staff during their focus group discussions.

4. Discussion

The findings confirm that vegetables are a fundamental component of the diet in Early Childhood Development (ECD) centres, youth centres, and among residents. Vegetable consumption is nearly universal (94%), and vegetables are a daily staple in 90% of meals at ECD and youth centres. While mainstream vegetables dominate consumption, familiarity with African Vegetables (AVs) is moderate. The motivation for consuming AVs is high, driven primarily by their nutritional value, ease of preparation, and cultural significance, suggesting a strong foundation for promoting their consumption. The high vegetable consumption rate highlights the community’s established dietary need for vegetables. As the findings did not show a correlation between demographic factors and vegetable preference, it suggests that interventions should target broad community efforts rather than being narrowly focused on specific age or gender groups.

While vegetables are widely consumed, there is a clear preference for mainstream crops (81%) over AVs (66%). This finding is critical as AVs are nutrient-dense and are better adapted to local climates [45,46]. The study identifies strong motivating factors for AV consumption, including their perceived nutritional value (87%), ease of preparation (80%), cultural significance (78%) and childhood memories (75%). The importance of cultural affirmation and childhood activities coincides with the motivations behind adult practices in foraging for wild plants in smaller towns in South Africa [16]. These positive associations provide a strong cultural foundation for creating greater meaning around food consumption and health, which could be aligned with educational campaigns. Cilliers et al. [15] posit that the involvement of multiple stakeholders in community gardens has potential for “the co-production of knowledge that could lead to social learning on aspects such as the cultivation of nutritious food.” Such co-production practices and deeper ways of knowledge sharing are argued to have greater potential for sustainability transformation [62], because they strengthen social outcomes such as a sense of belonging and environmental stewardship [78]. However, these motivations are tempered by significant barriers, rooted in both practical and socio-cultural factors. The most pressing obstacles are cost and limited availability (47%), followed by taste preferences (41%), a lack of familiarity (32%), and a lack of knowledge about preparation (24%). The fact that ECDs also mentioned limited access to recipes and availability suggests a systemic supply and information gap. These concerns—particularly regarding availability, taste, and the need for more accessible recipes and simplified preparation methods—are well-corroborated by existing literature [57,58,59,60,61]. Socio-cultural factors also hinder households from consuming and cultivating ALVs. These stem primarily from cultural stigmatization and knowledge transmission gaps. Although minimal, the perception of ALVs as “old-fashioned” (9%) suggests a need to reframe their image as modern, healthy, and culturally relevant. More significantly, the declining transmission of indigenous knowledge about these vegetables threatens their continued use, potentially creating a self-perpetuating cycle of reduced cultivation and consumption. Addressing these barriers through supporting local AV vendors, developing low-cost recipe dissemination, and integrating AVs into ECD menus will be crucial for increasing consumption patterns.

Urban agriculture is a common practice (55% participation), yet it mainly focuses on mainstream crops. This preference aligns with the economic findings: the statistically significant negative correlation between household income and vegetable gardening profitability (r = −0.220, p < 0.05) seemingly confirms that lower-income households are more motivated by the economic benefits of gardening. This suggests that for many participants, urban agriculture is a vital activity that supplements income or reduces costs, driving the choice toward familiar and commercially viable crops. The additional livelihood benefits of urban agriculture should, nonetheless, not be underestimated as a further motivation. In Atteridgeville, South Africa, a study by Van Averbeke [74], illustrated that the contribution to total household income and food security of the different types of farming found in their study was generally modest. Conversely, the study highlighted important livelihood benefits derived, including reduced social alienation and the prevention of family disintegration associated with urban poverty. Our study reveals a general practice of urban agriculture (and a strong preference for vegetables) across income groups, which aligns with studies on urban foraging, indicating that foraging was not limited to poorer households [16], indicating that these practices represent additional co-benefits unrelated to income.

The most dominant barrier to cultivation is high maintenance costs (54%), particularly for pest control and fertilizers. This challenge is exacerbated by limited space and poor environmental conditions (e.g., flooding, inadequate sun protection), the severity of which is intensified by climate change [79]. Both community members and ECDs also face logistical issues, such as limited access to water, fertilizer, and, for centres, a lack of refrigerated storage and electricity. Interventions must prioritize low-cost, sustainable pest management solutions and explore initiatives such as LWSs to overcome space limitations [80]. Additionally, integrating AVs into LWS provides a resilient solution for delivering valuable ecosystem services.

The Melusi community’s high interest in LWSs as EGI (72%) represents a substantial opportunity. The primary advantages identified by both community members and ECDs were space-saving and protection from animals. This directly addresses the identified major physical barrier to urban agriculture: limited space [81].

However, high implementation and maintenance costs, as well as concerns about the suitability of LWSs for certain crops (such as corn), pose initial reservations. To capitalise on this interest, pilot projects demonstrating low-cost, modular, and adaptable LWS designs using recyclable materials, such as the ones conducted in this study, are needed. Showcasing the aesthetic and well-being benefits, as noted by ECD staff, can further motivate adoption beyond purely practical concerns. LWSs could potentially enable AV cultivation in the space-constrained, challenging environments of marginalized sub-Saharan communities.

Limitations of This Study

A primary limitation of this study is the absence of a control for comparison between living wall systems and alternative food production interventions aimed at food security. Future research should attempt to incorporate a control group, specifically including traditional urban agriculture, to allow for a direct comparative assessment of living wall systems against other viable food security strategies.

Furthermore, the limited sample size of 100 respondents and 7 ECDs may not adequately represent the population’s variability or permit generalizability outside of this community. We recommend that future studies utilize broader sampling methods, encompassing multiple communities and statistically representative participant pools, to enhance the findings’ transferability.

Furthermore, the photo-elicitation method used in the 2023 survey—showing participants curated images of LWSs and AVs—may have positively influenced responses, despite measures taken to mitigate interviewer and social desirability bias. Crucially, the physical example of the LWSs and AVs in the 2024 survey provided participants with a valuable hands-on understanding of the concepts, their installation and maintenance, which was also discussed in focus groups to allow for multiple perspectives to be raised.

While demographic factors did not significantly impact the current findings, the data analysis primarily relied on descriptive statistics and Pearson correlations. Future studies should incorporate multivariate analysis to effectively account for potential confounding factors, such as income, gender, and education.

Additionally, future research should endeavor to measure and quantify the total impact of living wall systems utilizing African vegetables within African communities. This should encompass variables such as biomass yield and the nutritional profile of the AVs, alongside co-benefits such as passive cooling and air quality improvements.

5. Conclusions

This research explored the community’s perceptions of adopting outdoor modular living wall systems with African Vegetables in cultivation as part of edible green infrastructure in the Melusi Informal Settlement, Tshwane. The findings provide valuable insights into the challenges and potential benefits of integrating African vegetable cultivation into Living Wall Systems for low-income households.

The statistically significant negative correlation between household income and urban agriculture profitability suggests that economic benefit is a key motivator for lower-income households’ engagement in urban agriculture. Yet, the greater livelihood benefits of community gardens must not be underestimated. The important cultural connection between African Vegetables and their association with childhood can be leveraged to create greater cultural meaning around food consumption and health. The study highlights significant barriers to both consumption and cultivation in underprivileged communities. To address taste and related consumption, future studies could incorporate participatory workshops where participants and specifically community elders work together to document, adapt, and share traditional AV recipes. This could celebrate and formalize local culinary heritage, ensuring that knowledge about utilizing AVs is shared for improved consumption and cultural integration.

Regarding cultivation, despite a general community interest in urban agriculture, participation is limited by a focus on conventional crops and the reality of severe practical constraints. The foremost obstacle is economics, centered on high maintenance costs driven by the necessity of pest control, fertilizers, and water. This is compounded by significant physical and resource constraints, including extreme weather, lack of essential services like water and electricity, limited access to green open spaces, and insufficient sun protection. Furthermore, institutional stakeholders, like ECDs and youth centers, face additional issues with refrigerated storage and budget limitations. Ultimately, successful adoption and scaling of African vegetable cultivation in this setting require interventions that simultaneously address cost reduction, particularly for installation and maintenance inputs, space-efficient solutions like LWSs, and improved access to affordable, high-quality seeds.

The Melusi community supports integrating urban agriculture through LWSs with compact AV crops and values LWSs for their space-saving, cultural and biophilic benefits. While there is considerable interest in using innovative urban agriculture interventions, such as LWSs, due to their perceived benefits, reservations remain regarding implementation costs and suitability for all crops. Success requires low-tech modular designs, such as those implemented as part of this study.

This study offers valuable insights into the Melusi community and its specific youth facilities, which could provide a basis for testing hypotheses on crops and installations in other contexts. Future research should assess the sustained impact of the LWS intervention on household food security, dietary diversity, socio-economic and livelihood benefits, along with the continued acceptance and cultivation of AVs. Furthermore, such research should extend to other Sub-Saharan African communities and include other community facilities, such as clinics and places of worship. Additionally, future research could compare communities that benefit from access to LWS intervention with control groups that do not have access to these, in marginalized urban settings. This will allow for the identification of common facilitators and barriers to adopting LWSs and improving the generalizability of the findings.

Further studies are needed to identify suitable AVs for LWS projects and their potential contribution to food security and nutrition, considering their environmental adaptability and cultural heritage value. This research provides a valuable foundation for planning and implementing modular LWSs and AV cultivation in African urban communities. By addressing these recommendations, future studies can contribute to more effective and inclusive solutions that incorporate cultural meaning and facilitate knowledge sharing for achieving sustainable urban agriculture in vulnerable communities.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/land14122423/s1, File S1: Questionnaire to understand the Melusi community’s perceptions and utilisation of vertical food production and traditional African vegetables; File S2: Focus Meeting Questions: Melusi community’s experienced opportunities and barriers of living walls with local vegetables for food security.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization; methodology; software; validation; formal analysis; investigation; resources; data curation; writing—original draft preparation, K.L.B.; methodology; writing—review and editing, C.A.B.; visualization, K.L.B.; funding acquisition, K.L.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the University of Pretoria’s Scholarship of Teaching and Learning (SoTL).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the guidelines of the Faculty of Engineering, Built Environment, and Information Technology at the University of Pretoria (reference numbers EBIT/28/2023 and EBIT/11/2024, approved on 20 April 2023 and 2 April 2024).

Informed Consent Statement

All participants were informed about the purpose of the study and possible means of dissemination of the results. Participation was voluntary, with consent and all participants remained anonymous.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to ethical reasons.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AVs | African leafy Vegetables |

| ECDs | Early Childhood Development Centres |

| EGI | Edible Green Infrastructure |

| LWSs | Living Wall Systems |

| SDGs | Sustainable development Goals |

| UA | Urban Agriculture |

References

- UNEP. Cities and Climate Change. Available online: https://www.unenvironment.org/explore-topics/resource-efficiency/what-we-do/cities/cities-and-climate-change (accessed on 3 November 2025).

- Lopez, A.; Aguilar, M.; Vlez, J.S.; Pineda, E.F.; Ordoez, G.A. Design of a vegetable production model: Z-farming. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2019, 1418, 012013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO; IFAD; UNICEF; WFP; WHO. The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2018. In Building Climate Resilience for Food Security and Nutrition; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Siddiqui, F.; Salam, R.A.; Lassi, Z.S.; Das, J.K. The Intertwined Relationship Between Malnutrition and Poverty. Front. Public Health 2020, 8, 453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herrero, M.; Thornton, P.K.; Mason-D’Croz, D.; Palmer, J.; Bodirsky, B.L.; Pradhan, P.; Barrett, C.B.; Benton, T.G.; Hall, A.; Pikaar, I.; et al. Articulating the effect of food systems innovation on the Sustainable Development Goals. Lancet Planet. Health 2021, 5, e50–e62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Botes, K.L.; Breed, C.A. Traditional African vegetables in modular living walls: A novel approach towards smart cities. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2022, 1101, 022051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. Sustainable Development Goals. Ensure Sustainable Consumption and Production Patterns. Available online: https://www.fao.org/sustainable-development-goals/goals/goal-12/en/ (accessed on 3 November 2025).

- Steffen, W.; Richardson, K.; Rockström, J.; Cornell, S.E.; Fetzer, I.; Bennett, E.M.; Biggs, R.; Carpenter, S.R.; de Vries, W.; de Wit, C.A.; et al. Planetary boundaries: Guiding human development on a changing planet. Science 2015, 347, 1259855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sengupta, M. Transformational change or tenuous wish list?: A critique of SDG 1 (‘End poverty in all its forms everywhere’). Soc. Altern. 2018, 37, 12–17. [Google Scholar]

- Botes, K.L. The Performance of Traditional African Vegetables in Urban Outdoor Modular Living Wall Systems for Food Security in Gauteng, South Africa. Ph.D, Thesis, University of Pretoria, Pretoria, South Africa, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Braubach, M.; Egorov, A.; Mudu, P.; Wolf, T.; Ward Thompson, C.; Martuzzi, M. Effects of Urban Green Space on Environmental Health, Equity and Resilience. In Nature-Based Solutions to Climate Change Adaptation in Urban Areas: Linkages Between Science, Policy and Practice; Theory and Practice of Urban Sustainability Transitions; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017; p. 187. [Google Scholar]

- Wessels, N.; Sitas, N.; Esler, K.J.; O’Farrell, P. Understanding community perceptions of a natural open space system for urban conservation and stewardship in a metropolitan city in Africa. Environ. Conserv. 2021, 48, 244–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manyani, A.; Shackleton, C.M.; Cocks, M.L. Attitudes and preferences towards elements of formal and informal public green spaces in two South African towns. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2021, 214, 104147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abass, K.; Appiah, D.O.; Afriyie, K. Does green space matter? Public knowledge and attitude towards urban greenery in Ghana. Urban For. Urban Green. 2019, 46, 126462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cilliers, S.S.; Siebert, S.J.; Du Toit, M.J.; Barthel, S.; Mishra, S.; Cornelius, S.F.; Davoren, E. Garden ecosystem services of Sub-Saharan Africa and the role of health clinic gardens as social-ecological systems. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2018, 180, 294–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garekae, H.; Shackleton, C.M. Urban foraging of wild plants in two medium-sized South African towns: People, perceptions and practices. Urban For. Urban Green. 2020, 49, 126581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Köhler, M. Green facades—A view back and some visions. Urban Ecosyst. 2008, 11, 423–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radić, M.; Dodig, M.B.; Auer, T. Green Facades and Living Walls—A Review Establishing the Classification of Construction Types and Mapping the Benefits. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez, G.; Perini, K. Nature Based Strategies for Urban and Building Sustainability; Butterworth-Heinemann: Oxford, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Goel, M.; Jha, B.; Khan, S. Living walls enhancing the urban realm: A review. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 38715–38734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collins, R.; Schaafsma, M.; Hudson, M.D. The value of green walls to urban biodiversity. Land Use Policy 2017, 64, 114–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Söderlund, J. Living Green Wall Trials in a Hot Dry City Climate. In The Emergence of Biophilic Design; Söderlund, J., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 165–186. [Google Scholar]

- Nagle, L.; Echols, S.; Tamminga, K. Food production on a living wall: Pilot study. J. Green Build. 2017, 12, 23–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leininger, C.P. Food Producing Facades Key to a Sustainable Future. J. Des. Plan. Aesthet. Res. 2023, 2, 15–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botes, K.L.; Breed, C.A. Outdoor living wall systems in a developing economy: A prospect for supplementary urban food production? Acta Structilia 2021, 28, 143–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, A.; Escobedo, F.J.; Cirella, G.T.; Zerbe, S. Edible green infrastructure: An approach and review of provisioning ecosystem services and disservices in urban environments. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2017, 242, 53–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raj, S.; Raja, S.; Dukes, B.-A. Beneficial but Constrained: Role of Urban Agriculture Programs in Supporting Healthy Eating Among Youth. J. Hunger Environ. Nutr. 2017, 12, 406–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdias Rodias Paul, N. Urban agriculture and women’s empowerment: An analysis based on female producers in the Talangaï market gardening belt in Brazzaville (Republic of Congo). Adv. Res. Econ. Bus. Strategy J. 2024, 5, 72–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadebe, L.B.; Mpofu, J. Empowering Women through Improved Food Security in Urban Centers: A Gender Survey in Bulawayo Urban Agriculture. Afr. Educ. Res. J. 2013, 1, 18–32. [Google Scholar]

- Skar, S.L.G.; Pineda-Martos, R.; Timpe, A.; Pölling, B.; Bohn, K.; Külvik, M.; Delgado, C.; Pedras, C.M.; Paço, T.A.; Ćujić, M.; et al. Urban agriculture as a keystone contribution towards securing sustainable and healthy development for cities in the future. Blue-Green Syst. 2020, 2, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larcher, F.; Battisti, L.; Bianco, L.; Giordano, R.; Montacchini, E.; Serra, V.; Tedesco, S. Sustainability of Living Wall Systems Through An Ecosystem Services Lens. In Urban Horticulture: Sustainability for the Future; Sustainable Development and Biodiversity; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 31–51. [Google Scholar]

- Tafahomi, R.; Nkurunziza, D.; Benineza, G.G.; Nadi, R.; Dusingizumuremyi, R. The Assessment of Residents’ Perception of Possible Benefits and Challenges of Home Vertical Gardens in Kigali, Rwanda. Sustainability 2024, 16, 3849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Q.; Yue, Y.; Hu, D. Residents’ Attention and Awareness of Urban Edible Landscapes: A Case Study of Wuhan, China. Forests 2019, 10, 1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botes, K. Living walls: Upscaling their performance as green infrastructure. Acta Structilia 2024, 31, 43–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manso, M.; Castro-Gomes, J. Green wall systems: A review of their characteristics. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2015, 41, 863–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vosloo, P. Living walls and Green Facades: A case study of the UP Plant Sciences Vegetated Wall. Archit. S. Afr. 2016, 80, 42–55. [Google Scholar]

- Law, C.M.Y.; Law, H.Y.; Li, C.H.; Leung, C.W.; Pan, M.; Chen, S.; Ho, K.C.K.; Sham, Y.T. Data-Driven Approach for Optimising Plant Species Selection and Planting Design on Outdoor Modular Green Wall with Aesthetic, Maintenance, and Water-Saving Goals. Sustainability 2025, 17, 3528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aljehani, A.; Isaifan, R.J. The Economic and Environmental Payoff of Green Roofs and Vertical Forests in Urban Air Pollution Mitigation. Urban Plan. Constr. 2025, 3, 79–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, A.; Cirella, G.T. Edible Urbanism 5.0. Palgrave Commun. 2019, 5, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perini, K.; Rosasco, P. Cost-benefit analysis for green façades and living wall systems. Build. Environ. 2013, 70, 110–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Lu, Y.; Wong, N.H.; Poh, C.H. The true cost of “greening” a building: Life cycle cost analysis of vertical greenery systems (VGS) in tropical climate. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 228, 437–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bustami, R.A.; Beecham, S.; Hopeward, J. The Influence of Plant Type, Substrate and Irrigation Regime on Living Wall Performance in a Semi-Arid Climate. Environments 2023, 10, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mabhaudhi, T.; Chimonyo, V.G.P.; Hlahla, S.; Massawe, F.; Mayes, S.; Nhamo, L.; Modi, A.T. Prospects of orphan crops in climate change. Planta Int. J. Plant Biol. 2019, 250, 695–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mabhaudhi, T.; Chimonyo, V.G.P.; Modi, A.T. Status of Underutilised Crops in South Africa: Opportunities for Developing Research Capacity. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shayanowako, A.; Morrissey, O.; Tanzi, A.; Muchuweti, M.; Mendiondo, G.; Mayes, S.; Modi, A.; Mabhaudhi, T. African Leafy Vegetables for Improved Human Nutrition and Food System Resilience in Southern Africa: A Scoping Review. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mwadzingeni, L.; Afari-Sefa, V.; Shimelis, H.; N’Danikou, S.; Figlan, S.; Depenbusch, L.; Shayanowako, A.I.T.; Chagomoka, T.; Mushayi, M.; Schreinemachers, P.; et al. Unpacking the value of traditional African vegetables for food and nutrition security. Food Secur. Sci. Sociol. Econ. Food Prod. Access Food 2021, 13, 1215–1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botes, K.L. Traditional African Vegetables: Living walls. Afr. J. Landsc. Archit. 2022. Available online: https://www.ajlajournal.org/articles/traditional-african-vegetables-living-walls (accessed on 1 February 2025).

- Dissanayake, D.H.G.; Maredia, K.M. (Eds.) Home Gardens for Improved Food Security and Livelihoods; Routledge: London, UK, 2020; pp. 1–28. [Google Scholar]

- Xaba, T.; Dlamini, S. Factors associated with consumption of fruits and vegetables amongst adults in the Alfred Duma Local Municipality, Ladysmith. S. Afr. J. Clin. Nutr. 2021, 34, 72–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cloete, P.C.; Idsardi, E.F. Consumption of Indigenous and Traditional Food Crops: Perceptions and Realities from South Africa. Agroecol. Sustain. Food Syst. 2013, 37, 902–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mabhaudhi, T.; Chibarabada, T.P.; Chimonyo, V.G.P.; Murugani, V.G.; Pereira, L.M.; Sobratee, N.; Govender, L.; Slotow, R.; Modi, A.T. Mainstreaming Underutilized Indigenous and Traditional Crops into Food Systems: A South African Perspective. Sustainability 2018, 11, 172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Komives, K.; Whittington, D.; Wu, X. Infrastructure Coverage and the Poor. A Global Perspective; World Bank Publications: Washington, DC, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Molina-Montenegro, M.A.; Zurita-Silva, A.; Oses, R. Effect of water availability on physiological performance and lettuce crop yield (Lactuca sativa). Int. J. Agric. Nat. Resour. 2011, 38, 65–74. [Google Scholar]

- Mushi, E.; Alphonce, R.; Waized, B.; Muhanga, M.; Khalili, N.; Rybak, C. Influence of consumer socio-psychological food environment on food choice and its implications for nutrition: Evidence from Tanzania. Front. Nutr. 2025, 12, 1589492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tadele, Z.; Bartels, D. Promoting orphan crops research and development. Planta Int. J. Plant Biol. 2019, 250, 675–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Opabode, J.T. Sustainable Mass Production, Improvement, and Conservation of African Indigenous Vegetables: The Role of Plant Tissue Culture, a Review. Int. J. Veg. Sci. 2017, 23, 438–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faber, M.; Oelofse, A.; Van Jaarsveld, P.; Wenhold, F.; Jansen van Rensburg, W. African leafy vegetables consumed by households in the Limpopo and KwaZulu-Natal provinces in South Africa. S. Afr. J. Clin. Nutr. 2010, 23, 30–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merchant, E.V.; Odendo, M.; Ndinya, C.; Nyabinda, N.; Maiyo, N.; Downs, S.; Hoffman, D.J.; Simon, J.E. Barriers and Facilitators in Preparation and Consumption of African Indigenous Vegetables: A Qualitative Exploration From Kenya. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2022, 6, 801527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taruvinga, A.; Nengovhela, R. Consumers’ Perceptions and Consumption Dynamics of African Leafy Vegetables (ALVs): Evidence from Feni Communal Area, Eastern Cape Province, South Africa; IPCBEE: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Gido, E.O.; Ayuya, O.I.; Owuor, G.; Bokelmann, W. Consumer Acceptance of Leafy African Indigenous Vegetables: Comparison Between Rural and Urban Dwellers. Int. J. Veg. Sci. 2017, 23, 346–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregory, P.J.; Mayes, S.; Hui, C.H.; Jahanshiri, E.; Julkifle, A.; Kuppusamy, G.; Kuan, H.W.; Lin, T.X.; Massawe, F.; Suhairi, T.A.S.T.M.; et al. Crops For the Future (CFF): An overview of research efforts in the adoption of underutilised species. Planta Int. J. Plant Biol. 2019, 250, 979–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abson, D.J.; Fischer, J.; Leventon, J.; Newig, J.; Schomerus, T.; Vilsmaier, U.; von Wehrden, H.; Abernethy, P.; Ives, C.D.; Jager, N.W.; et al. Leverage points for sustainability transformation. Ambio 2017, 46, 30–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breed, C.A.; Du Plessis, T.; Engemann, K.; Pauleit, S.; Pasgaard, M. Moving green infrastructure planning from theory to practice in sub-Saharan African cities requires collaborative operationalization. Urban For. Urban Green. 2023, 89, 128085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engelbrecht, C.J.; Engelbrecht, F.A. Shifts in Köppen-Geiger climate zones over southern Africa in relation to key global temperature goals. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 2016, 123, 247–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SA Weather Service. Regional Weather and Climate of South Africa: Gauteng; SA Weather Service: Centurion, South Africa, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- SAPRIN. Battling the Elements: Melusi’s Struggle Under the Watchful Eye of GRT-INSPIRED. Available online: https://saprin.mrc.ac.za/newsletter/April/Melusi.pdf (accessed on 30 November 2024).

- SAPRIN. South African Population Research Infrastructure Network (SAPRIN). Available online: https://saprin.mrc.ac.za/grtinspired.html#:~:text=It%20is%20estimated%20that%20approximately,the%20release%20of%20Census%202022 (accessed on 10 June 2024).

- Botes, K.L. (University of Pretoria, Pretoria, South Africa). Photographs of the Melusi Informal Settlement in Pretoria. Personal Photo. 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Silva, E.A. The Routledge Handbook of Planning Research Methods; Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Almalki, S. Integrating Quantitative and Qualitative Data in Mixed Methods Research--Challenges and Benefits. J. Educ. Learn. 2016, 5, 288–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atmore, E.; van Niekerk, L.-J.; Ashley-Cooper, M. Challenges facing the early childhood development sector in South Africa. S. Afr. J. Child. Educ. 2012, 2, 120–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mokone, S.M.; Manafe, M.; Ncube, L.J.; Veldman, F.J. A comparative analysis of the nutritional status of children attending early childhood development centres in Gauteng, North-west and Limpopo province, South Africa. Afr. J. Food Agric. Nutr. Dev. 2022, 22, 19353–19369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Kock, M. Research Report. Master’s Thesis, University of Pretoria, Pretoria, South Africa, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Van Averbeke, W. Urban farming in the informal settlements of Atteridgeville, Pretoria, South Africa. Water SA 2007, 33, 337–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leedy, P.D.; Ormrod, J.E. Practical Research: Planning and Design, 11th ed.; Always Learning; Pearson Education: Harlow, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Bingham, A.J. From Data Management to Actionable Findings: A Five-Phase Process of Qualitative Data Analysis. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2023, 22, 16094069231183620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Department of Employment and Labour. National Minimum Wage Report 2023; LPC: London, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Kiss, B.; Sekulova, F.; Hörschelmann, K.; Salk, C.F.; Takahashi, W.; Wamsler, C. Citizen participation in the governance of nature-based solutions. Environ. Policy Gov. 2022, 32, 247–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chari, F.; Ngcamu, B.S. Climate change and its impact on urban agriculture in Sub-Saharan Africa: A literature review. Environ. Socio-Econ. Stud. 2022, 10, 22–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Payen, F.T.; Evans, D.L.; Falagán, N.; Hardman, C.A.; Kourmpetli, S.; Liu, L.; Marshall, R.; Mead, B.R.; Davies, J.A.C. How Much Food Can We Grow in Urban Areas? Food Production and Crop Yields of Urban Agriculture: A Meta-Analysis. Earth’s Future 2022, 10, e2022EF002748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viljoen, A.; Bohn, K.; Howe, J. Continuous Productive Urban Landscapes: Designing Urban Agriculture for Sustainable Cities; Elsevier: Oxford, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).