Abstract

Understanding how long-term local climate zone (LCZ) dynamics interact with rapid urbanization and land surface temperature (LST) changes is essential for sustainable planning in megaregion-scale urban clusters. In this paper, we propose a multi-feature local sample transfer method to obtain LCZ maps from 2000 to 2020 in the Guangdong–Hong Kong–Macao Greater Bay Area (GBA) and then analyze spatiotemporal changes in LCZs and their impacts on surface thermal environments. Results show the following: (1) The proposed multi-feature local sample transfer approach significantly improves the efficiency of long-term LCZ mapping by greatly reducing the effort required for sample acquisition. (2) The built types (LCZ1–10) increased by 1.34% overall, with large low-rise (LCZ8) showing the greatest expansion (4.72%). The compact low-rise (LCZ3) was the only built type to decline, decreasing by 2.02%. (3) Urbanization has produced a contiguous warming core that expands outward from the central metropolitan zones, thereby promoting the UHI coalescence. (4) Dense trees (LCZA) and large low-rise (LCZ8) exerted the strongest influence on LST. Large low-rise (LCZ8) consistently exhibited the highest warming contribution in Foshan, Zhongshan, and Dongguan. In coastal cities including Shenzhen, Hong Kong, and Macao, the largest LST increases occurred when water (LCZG) areas were converted to bare rock or paved (LCZE) or cs (LCZ1–10). Overall, the results highlight the strong coupling between urbanization and surface heating, providing critical insights for urban climate adaptation and integrated land-use planning in rapidly urbanizing megaregions.

1. Introduction

Amid accelerating global warming and urbanization, land cover changes and intensified human activities have exacerbated urban heat island (UHI) effects, posing increasing threats to public health, urban livability, and socioeconomic sustainability. The UHI effect refers to the phenomenon that urban centers exhibit higher temperatures than suburban or rural areas. However, the complexity of urban–rural systems and the difficulty of defining their boundaries [1] introduce substantial uncertainties in quantifying UHI intensity. Moreover, describing thermal differences solely based on geographic location (urban vs. rural) overlooks critical surface characteristics—such as land cover, urban morphology, and function—that govern local climatic variations [2]. To address these limitations, Stewart and Oke proposed the local climate zone (LCZ) system, a land-cover-based system specifically designed for urban climate and UHI studies.

LCZs are spatial units ranging from several hundred meters to a few kilometers in horizontal extent, characterized by internally homogeneous surface cover, structure, materials, and human activity [1]. Compared with conventional land-cover classifications, LCZs provide a more detailed representation of both built and natural surface types. Built LCZs are distinguished by factors such as building height, surface fraction, spatial arrangement, and vegetation cover, while land-cover LCZs are classified primarily by vegetation height and coverage ratio. Thus, LCZs not only provide a standardized framework for describing UHI effects but also capture the spatial variations in human-modified landscapes. By reflecting the complexity and diversity of urban climates and surface characteristics, the LCZ framework has been widely applied in urban thermal environment studies [3,4,5].

Recent advances in remote sensing and computational technologies have further stimulated interest in long-term LCZ analyses, a research frontier that bridges urban climatology and landscape ecology [6,7,8]. Rather than focusing solely on the spatial distribution of LCZs at a single time point, these studies emphasize multi-temporal and multi-decadal dynamics and their climatic implications. Time-series LCZ datasets enable researchers to quantify urban expansion patterns, track the evolution of the UHI effects, and provide scientific evidence for climate-adaptive urban planning.

Most existing single-date LCZ mapping based on remote sensing data has primarily relied on the WUDAPT (World Urban Database Portal Tools) framework [9,10,11] and other supervised classification approaches [12,13,14,15]. Multi-temporal LCZ mapping is commonly conducted by repeating single-date mapping at different time points, with independent training samples for each [6]. However, due to the relatively large number of LCZ types and the substantial samples required, manual sample selection for each time point is both labor-intensive and time-consuming. This limitation makes the approach difficult to apply in large-area or multi-temporal mapping, particularly when samples are unavailable for certain periods. Furthermore, it constrains accurate and consistent classification of time-series imagery in an automated manner. Consequently, automatic or transferable sample acquisition methods that reduce manual effort are essential for effective time-series LCZ mapping.

Previous single-date studies examining the relationship between LCZs and land surface temperature (LST) can be broadly categorized into three groups: (i) descriptive analyses of LCZ–LST relationships [16], (ii) cross-city comparative studies [17], and (iii) correlation analyses between UHI intensity and surface indicators (e.g., building height, impervious surface fraction) within LCZs [18]. However, such single-date analyses fail to capture dynamic changes and reveal the driving mechanisms of LCZ–LST relationships during urbanization. Long-term analyses are therefore essential for a more comprehensive understanding of the spatiotemporal evolution of urban thermal environments.

Despite growing interest, long-term studies on LCZs and LST have predominantly focused on the spatial composition of LCZs. Previous research has examined temporal changes in the spatial configuration of LCZs within individual cities and performed basic statistical comparisons of LST across LCZ types at different times [10,19,20]. However, these studies generally lack rigorous quantitative analysis, limiting their capacity to accurately characterize intra-urban variations in LCZs and LST. To address this gap, the present study conducts a comprehensive quantitative assessment of the spatiotemporal dynamics of LCZs and their relationship with LST, aiming to elucidate the influence of LCZ transformations on UHI intensity.

The Guangdong–Hong Kong–Macao Greater Bay Area (GBA), one of the world’s four major bay areas, holds an important strategic position in both China’s and the global economy. Rapid urbanization has led to extensive land-cover transformations, converting large areas of cropland and coastal wetlands into built-up land. These transformations have induced ecological imbalance and environmental challenges, particularly the intensification of UHI effects [7,21,22]. In the process of advancing ecological civilization, adopting a “people-centered” development paradigm and balancing economic growth with environmental protection have become key priorities for the high-quality development of the GBA. Accurately assessing and mitigating the UHI effects has remained a critical concern in territorial spatial planning and urban development. Notably, in July 2022, seventeen Chinese governmental departments jointly issued the National Climate Change Adaptation Strategy 2035, which emphasizes that, under conditions of significant global warming, the GBA faces concentrated climate risks with pronounced cascading effects. The strategy calls for strengthening ecological spatial regulation and coordinating urban greening to mitigate UHI impacts. Therefore, investigating land-cover changes and the UHI effects in the GBA is crucial for implementing context-specific strategies to promote regional sustainable development.

This study has two primary objectives: to develop a robust multi-temporal LCZ classification method for detecting change in the GBA and to investigate its relationship with concurrent LST dynamics.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

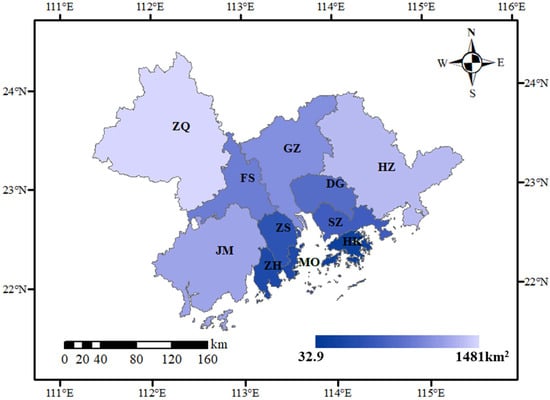

The GBA is located in South China and consists of nine mainland cities in the Pearl River Delta—Shenzhen (SZ), Guangzhou (GZ), Foshan (FS), Zhongshan (ZS), Dongguan (DG), Zhuhai (ZH), Huizhou (HZ), Jiangmen (JM), and Zhaoqing (ZQ)—together with the Hong Kong (HK) and Macao (MO) Special Administrative Regions (Figure 1). Over the past two decades, the GBA has emerged as one of China’s most economically dynamic and industrially active regions, as well as one of the fastest urbanizing regions globally. Climatically, the GBA experiences abundant solar radiation, high humidity, and distinct seasonal variations, with a humid subtropical monsoon climate that brings hot, wet summers and mild, dry winters. Topographically, the region is dominated by low-lying plains, with areas above 500 m elevation accounting for only about 3% of the total land area [23]. Consequently, the influence of elevation on LST can be reasonably neglected in analyses of the regional surface thermal environment.

Figure 1.

Overview of the study area and the area of each city.

The GBA provides an ideal setting for LCZ studies, encompassing 14 LCZ types ranging from compact high-rise (LCZ1) to water (LCZG), forming a relatively complete framework. Rapid urbanization has driven intense LCZ transitions, offering dynamic scenarios for observing the evolution of the land surface thermal environment. Moreover, Shenzhen is fully urbanized, while Hong Kong and Macao, as highly urbanized special administrative regions, pose challenges for traditional urban–rural classification methods in quantifying UHI effects. The LCZ framework, however, can accurately capture the internal structure and thermal characteristics of such built environments, enabling a more rigorous examination of the interactions between urban morphology and climate.

2.2. Sen + Mann–Kendall Analysis of LST Trends

The Sen trend analysis is a robust non-parametric statistical method used to detect trends in time-series data. By calculating the median of the sequence, it effectively reduces the influence of outliers, making it suitable for long-term trend detection [24]. However, the Sen method alone cannot determine whether the observed trend is statistically significant. The Mann–Kendall (MK) test, another non-parametric approach, is widely used to assess the significance of trends in time-series data. It does not require the data to follow a normal distribution and is insensitive to outliers and missing values, making it well-suited for long-term climatic or environmental analyses. Long-term LST data are often affected by atmospheric conditions, sensor noise, and cloud-related disturbances. Although seasonal averaging (e.g., summer mean LST) can mitigate these effects to some extent, anomalies may still remain. Therefore, to enhance the robustness against noise and improve the reliability of the trend detection, the Sen’s slope estimator and the Mann–Kendall significance test were combined to analyze LST trends from 2000 to 2020. The combined Sen + Mann–Kendall trend analysis was conducted in MATLAB (v2024) as follows [25,26].

The Sen’s slope () was calculated using:

where and represent the LST values in years and , respectively, and Median() denotes the median operator. A positive value of indicates an upward trend in LST, while a negative implies a downward trend.

For a time-series , the Mann–Kendall statistic is computed as:

where

The null hypothesis () assumes that the data are randomly distributed with no significant trend, while the alternative hypothesis () assumes a monotonic upward or downward trend.

When the sample size , the significance test is directly based on the statistic . At a given significance level , if , the null hypothesis is rejected, indicating a significant trend. Conversely, if , is accepted, indicating no significant trend. When , approximately follows a normal distribution, and the standardized test statistic is computed as:

where the variance of is given by:

Here, is the number of data points, is the number of tied groups in the dataset, and represents the number of data points in the ith group of ties. At a given significance level , if , the null hypothesis is rejected, indicating a statistically significant trend. Otherwise, is accepted, implying that the trend is not significant.

The Sen + Mann–Kendall method provides a robust and widely accepted framework for detecting, quantifying, and assessing the statistical significance of long-term LST trends under noisy environmental conditions. This combined approach minimizes the influence of outliers and data irregularities, ensuring reliable interpretation of temporal thermal variations across complex urban and climatic settings.

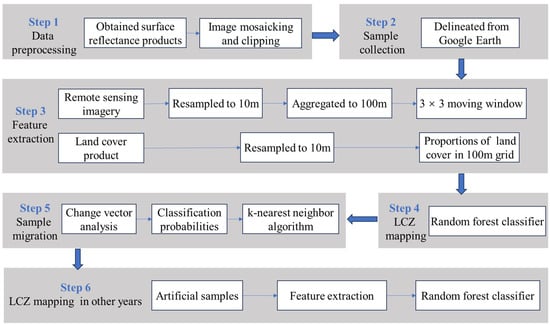

2.3. Multi-Temporal LCZ Mapping Based on Multi-Feature Local Sample Transfer

Due to the diverse LCZ types and the vast spatial extent of the GBA, obtaining sufficient training samples for LCZ mapping is a labor-intensive and time-consuming task, posing challenges for long-term LCZ mapping in the region. Therefore, ensuring mapping accuracy while addressing the issue of sample acquisition is critical for multi-temporal LCZ mapping in the GBA. To tackle this challenge, a multi-feature local sample transfer method based on land-cover classification products and remote sensing imagery was proposed using MATLAB v2024 (Figure 2). This approach reduces reliance on extensive manual sample collection, enhances mapping automation, and facilitates accurate and consistent multi-temporal LCZ mapping in the GBA.

Figure 2.

The proposed framework for multi-temporal LCZ mapping.

(1) Grid design and data preprocessing: A spatial resolution of 100 m effectively captures homogeneous urban fabric units—such as residential areas, industrial zones, parks, or water bodies. If the resolution is too coarse, a single pixel may mix multiple land cover types (e.g., buildings, water, and vegetation), making it unrepresentative of any specific physical surface property. Conversely, if the resolution is too high, it introduces substantial redundancy and results in classification units that are considerably smaller than the spatial scale of physical processes influencing temperature. Moreover, the 100 m resolution aligns naturally with the 30 m resolution of Landsat imagery, conceptually clear and computationally efficient aggregation. As a result, the 100 m resolution has been widely adopted in numerous studies [11,27,28]. Based on existing studies and multiple tests, a spatial resolution of 100 m was adopted for LCZ mapping in the GBA. To minimize the influence of clouds and atmospheric disturbances, atmospherically corrected surface reflectance data (Landsat 5_SR and Landsat 8_SR) with low cloud cover in 2000, 2005, 2010, 2015, and 2020 were acquired from the USGS. All images were mosaicked and clipped to the GBA boundary.

(2) Sample collection (2020): Training samples for 2020 were delineated based on the high-resolution imagery from Google Earth. After careful visual inspection and cross-validation, 2876 samples were obtained, with 75% used for training and 25% reserved for accuracy assessment.

(3) Feature extraction (2020): Two groups of features were designed to comprehensively characterize LCZ patterns:

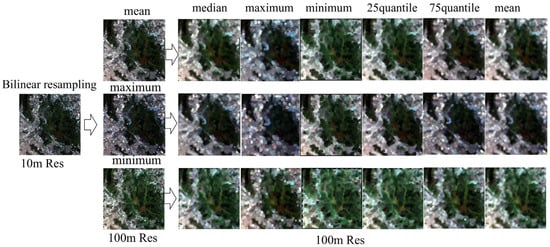

➀ Remote sensing imagery: All nine multispectral and thermal infrared bands of Landsat 8_SR (30 m resolution) were linearly resampled to 10 m. To enhance spectral information and improve classification performance, the images were aggregated to 100 m resolution by computing zonal mean, maximum, and minimum values within each LCZ grid cell. Additionally, a 3 × 3 moving window was applied to derive six contextual statistics (mean, median, maximum, minimum, 25th percentile, and 75th percentile) to incorporate contextual information (Figure 3). Adjacent pixels in remote sensing imagery exhibit strong spatial autocorrelation, and exploiting a moving window to extract local contextual information can more effectively capture land surface features [29]. Among various window sizes, the 3 × 3 window is widely adopted due to its optimal balance between computational efficiency and the capacity to characterize local patterns [30]. Notably, the most classic and fundamental convolution kernels in image processing are designed based on the 3 × 3 neighborhood structure [31].

Figure 3.

Features extracted from satellite imagery.

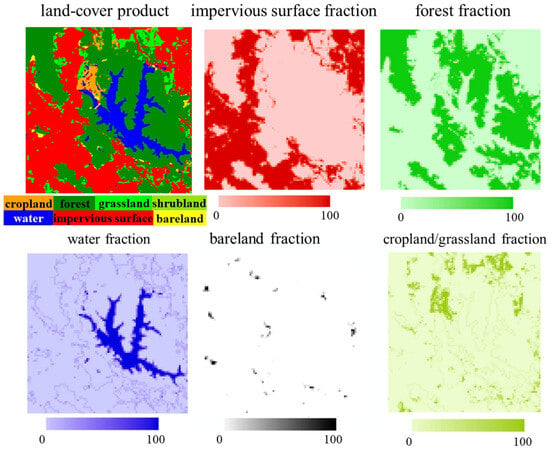

➁ Land cover product: The 30 m land cover product based on Landsat 8_SR was resampled to 10 m. Within each 100 m grid, the proportions of impervious surfaces, forest, water, bareland, and cropland/grassland were calculated to provide land cover composition information (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Features extracted from Land cover product.

(4) LCZ mapping: Given the robustness to noisy data and strong performance in pixel-based LCZ classification, the random forest classifier was employed for LCZ mapping using the features above and the manually labeled training samples.

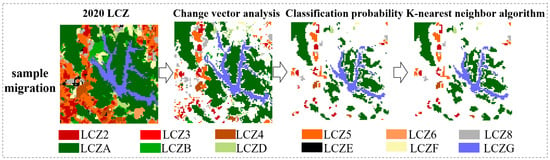

(5) Sample migration: To minimize manual labeling efforts in the large-area and multi-temporal mapping, a sample transfer method was designed. Change vector analysis was applied to remote sensing features from image bands and land cover products between two time points to identify changed pixels [32]. Classification probabilities were then used to assess image reliability, ensuring that only pixels located in unchanged areas with high confidence in time point 1 were transferred as training samples for time point 2 [33]. Finally, representative samples were selected using the k-nearest neighbor algorithm [34] (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

The sample migration framework.

(6) LCZ mapping in other years. Following sample transfer, additional samples were manually added to underrepresented LCZ types to ensure a balanced dataset. The feature extraction procedures for other years were consistent with those of 2020. LCZ maps were automatically generated using a random forest classifier, and independent testing samples were randomly selected from regions outside the training sample areas to ensure spatial independence.

2.4. Analysis of the LCZ Dynamics and LST

To comprehensively examine the relationship between LCZ dynamics and LST, two complementary metrics were employed using MATLAB v2024: the LCZ Contribution Index (LCZCI) and the LCZ transition matrix. The LCZCI, adapted from the concept of land contribution index [35,36], quantifies the relative contribution of each LCZ type to the UHI effects by integrating its mean surface temperature and areal proportion within the city. It is defined as:

where denotes the mean LST of LCZ type i, M is the mean LST of the entire city, and represents the proportion of the city area occupied by LCZ type i. The LCZCI range is determined by two factors: first, the range of temperature extremes—the maximum temperature difference between the coldest LCZ (e.g., water (LCZG)) and the hottest LCZ (e.g., large low-rise (LCZ8))—sets the basic variation; second, area normalization, which standardizes contributions across LCZ types of different scales, confines the index to a quantifiable and comparable numerical interval. Positive LCZCI values indicate that a type acts as a heat source, exacerbating the UHI effects, while negative values indicate a cooling effect. This formulation enables quantitative comparison of the relative contributions of different LCZ types to regional heat island dynamics.

To further assess the thermal impacts of LCZ conversions, a 14 × 14 LCZ transition matrix was constructed to evaluate the net impact of LCZ conversions on LST changes in the GBA. Based on LCZ maps from 2000 to 2020, LCZ transition maps were generated, and the mean LST change was calculated for each transition type. To isolate the effect of LCZ conversions, the mean LST of unchanged LCZs (diagonal elements) was subtracted from each corresponding row. Consequently, the resulting matrix entries represent the net LST impact of each transition: positive values denote warming effects, negative values indicate cooling effects, and empty cells correspond to transitions that did not occur.

The combined use of LCZCI and the LCZ transition matrix thus provides an integrated framework for quantifying both the steady-state and dynamic thermal contributions of different urban forms. This approach enables a deeper understanding of how LCZ composition and transformation influence long-term urban thermal environments.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. LCZ Mapping Accuracy and Spatiotemporal Characteristics of LCZ Changes

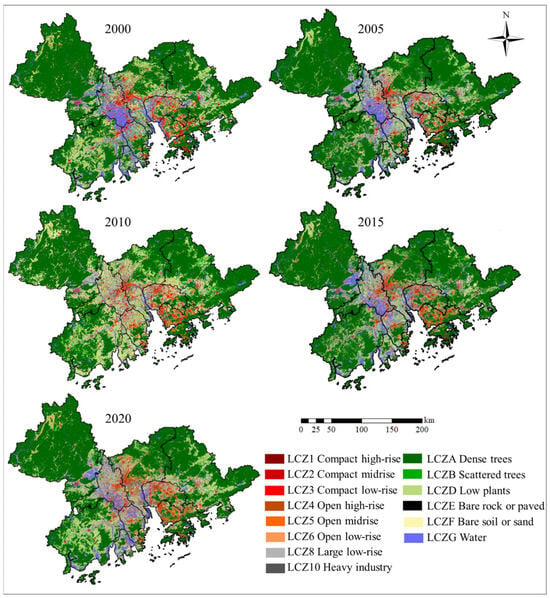

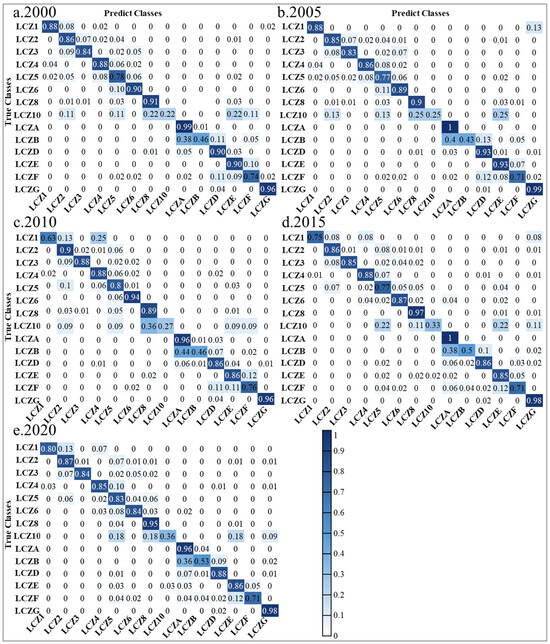

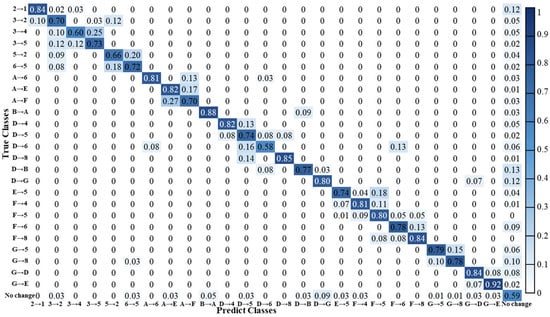

Using the proposed multi-feature local sample transfer method, LCZ maps of the GBA were generated for 2000, 2005, 2010, 2015, and 2020 (Figure 6). The overall accuracies were 85.12%, 85.03%, 85.13%, 85.28%, and 85.02%, respectively, with corresponding Kappa coefficients of 0.837, 0.826, 0.837, 0.839, and 0.836, indicating stable and reliable classification performance across all time points. The confusion matrix diagrams for the LCZ classifications from 2000 to 2020 are presented in Figure 7. In the GBA, 13 LCZ types were identified, which theoretically allow for 156 (13 × 12) possible transition types. However, only 25 transition types occurred frequently. To evaluate the change detection performance, 30 validation samples were randomly selected for each transition type between consecutive periods. The change detection reached an overall accuracy of 76.47% and a Kappa coefficient of 0.76 (Figure 8), demonstrating reliable performance in identifying spatiotemporal LCZ transitions.

Figure 6.

LCZ classification for the GBA from 2000 to 2020.

Figure 7.

Confusion matrix diagrams for LCZ classification from 2000 to 2020.

Figure 8.

Confusion matrix diagrams for the pixel-level change transitions from 2000 to 2020 (Numbers and letters correspond to different LCZ categories. For example, the number 1 represents LCZ1, and the letter A corresponds to LCZA).

A total of 2509 samples were manually collected for LCZ mapping in 2020. Only 202, 192, 197 and 203 supplementary samples were required for 2000, 2005, 2010 and 2015, respectively, accounting for less than 10% of the manual labeling effort in 2020. This substantial reduction underscores the high efficiency and transferability of the proposed sample transfer strategy for multi-temporal LCZ mapping.

To examine the spatiotemporal evolution of LCZs in the GBA, the proportional area changes in each LCZ type from 2000 to 2020 were calculated (Figure 9). Overall, built types (LCZ1–10) expanded by 1.34% over the 20-year period. Among these, LCZ8 (large low-rise) showed the largest increase (4.72%), followed by open built types (LCZ4, LCZ5 and LCZ6). In contrast, LCZ3 (compact low-rise) was the only built type to decline, decreasing by 2.02%. For land-cover types (LCZA–G), low plants (LCZD) exhibited the largest reduction, shrinking by 9.32% of the total GBA.

Figure 9.

LCZ area changes from 2000 to 2020 (%).

In all 11 cities of the GBA, the increase in compact built types (LCZ1–3) was consistently smaller than that of open built types (LCZ 4–6). This pattern indicates that new developments were less frequently arranged in dense configurations, reflecting the region’s emphasis on livability, human-centered planning, and residential comfort. Over the past decade, the nine inland cities were designated as National Forest Cities and National Garden Cities, supported by strict forest protection policies and a regional strategy to establish a GBA forest city cluster. As a result, the reduction in dense trees (LCZA) across all GBA cities was much smaller than that of low plants (LCZD), with Huizhou’s dense trees (LCZA) decreasing by only 0.73%. These findings indicate that urban development in the region has been accompanied by effective forest vegetation protection and ecological environment improvement.

Guangzhou, Shenzhen, and Dongguan—major inland first-tier and emerging first-tier cities—experienced the most significant economic growth and urban expansion, with open high-rise (LCZ4) areas increasing by 5.18%, 9.04%, and 7.84%, respectively. In contrast, Zhaoqing, a third-tier city with weaker regional economic influence, showed the smallest growth in built types (LCZ1–10) (4.34%). Due to high population density and limited land availability, Macao and Hong Kong exhibited the greatest urban compactness, with compact high-rise (LCZ1) areas expanding more than in any inland city. In addition, the construction of the Zhuhai–Macao artificial island resulted in the largest reduction in water (LCZG) area proportion in Macao (12.64%).

Foshan, Dongguan, and Zhongshan recorded the largest increases in large low-rise (LCZ8)—14.89%, 14.30%, and 14.07%, respectively—corresponding closely with their strong industrial expansion. Foshan benefited from Guangzhou’s economic spillover and reported the second-highest gross industrial product growth after Shenzhen. Dongguan and Zhongshan also expanded their industrial land due to their relatively high industrial output shares. Urban master plans further reinforced this pattern. Foshan was designated as a major manufacturing base, while Dongguan aimed to become a national center for information technology and light manufacturing, with major industrial clusters in Changping, Tangxia, Mayong, and Shatian. Zhongshan’s development strategy emphasized high-tech and modern manufacturing within a “clustered development structure”. Consequently, Foshan, Dongguan, and Zhongshan exhibited the most substantial growth in large low-rise (LCZ8) areas throughout their urban development.

In contrast, Zhaoqing, a third-tier city emphasizing cultural tourism and ecological conservation, had the smallest increase in built types (LCZ1–10) (4.34%). Despite a 1.82% decline in dense trees (LCZA) from 2000 to 2020, forest coverage remained at 78.98%—the highest in the GBA—providing strong cooling through shading and evapotranspiration.

3.2. Spatial and Temporal Trends of LST

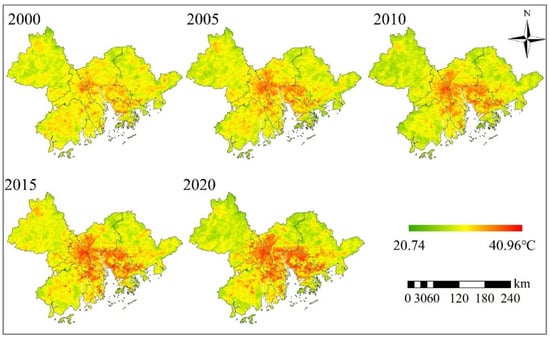

To minimize the influence of atmospheric conditions, cloud contamination, and other sources of uncertainty, summer mean LSTs from 2000 to 2020 were employed to characterize long-term thermal variations (Figure 10). LST data were derived from the EOS-Aqua MODIS 8-day composite product (MYD11A2, the MYD11A2 was acquired from the United States Geological Survey (USGS) EarthExplorer. This product is generated and maintained by the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) and distributed through its Level-1 and Atmosphere Archive & Distribution System (LAADS) Distributed Active Archive Center (DAAC) in Greenbelt, MD, USA), which provides daytime observations at approximately 13:30 local time. The MYD11A2 LST data were selected because it is an officially validated dataset developed by the United States Geological Survey with well-documented accuracy and excellent long-term temporal consistency. In contrast, although Landsat satellites provide thermal infrared data at a higher spatial resolution, sensor differences across the Landsat series can compromise the consistency and accuracy of long-term LST records. Moreover, the GBA experiences frequent summer rainfall and persistent cloud cover, resulting in substantial data gaps when deriving summer-mean LST from Landsat—often leaving many pixels as missing values. The 1 km spatial resolution of MODIS LST means each LST pixel may encompass approximately 10 × 10 LCZ pixels, thereby introducing the potential for mixed-pixel effects, where a single LST value aggregates the thermal signatures of multiple LCZ types (e.g., built-up areas, vegetation, and water). To address this, we employed a widely adopted NDVI-based LST downscaling method [37,38,39] in calculating the LCZCI and restricted LCZ–LST analyses to LCZ patches with sufficient spatial extent to ensure statistical robustness. While the resolution mismatch inevitably constrains pixel-level precision, these methodological steps substantially reduce mixed-pixel bias and allow us to robustly characterize the systematic relationships between LCZ types and LST at the regional scale.

Figure 10.

Average summer daytime LST from 2000 to 2020.

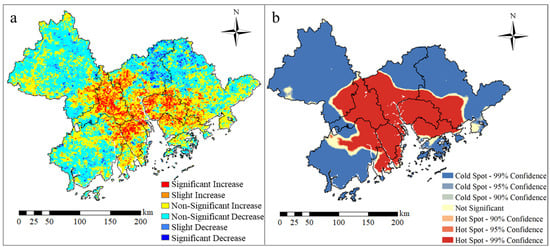

To investigate the spatiotemporal trends of LST in the GBA, the Sen + Mann–Kendall method was employed to quantify long-term LST trends from 2000 to 2020 (Figure 11a). As shown in Figure 11a, the triangular central GBA exhibited a statistically significant warming trend, whereas the surrounding regions showed a slight cooling tendency. The change in the central part of the GBA with a significant increase is mainly due to the large-scale distribution of built-up areas [40,41]. Based on summer noon air temperature observations from 2000 to 2020 at four meteorological stations in the GBA (Hong Kong International Airport, Macao International Airport, Guangzhou Baiyun International Airport, and Shenzhen Bao’an International Airport), all stations exhibited a consistent warming trend, in line with the increase in LST. Among them, Hong Kong International Airport experienced the largest rise, from 29.19 °C to 29.69 °C. From 2000 to 2020, LST increased significantly across all four major bay areas (San Francisco Bay Area, SFBA; New York Bay Area, NYBA; Tokyo Bay Area, TBA; and GBA), with coastal core cities serving as hotspots of thermal expansion. In terms of urban heat island clustering, the four city clusters exhibit distinct spatial patterns: the nuclear ribbon pattern (SFBA and NYBA), the multi-core sectoral pattern (TBA), and the triangular regional expansion pattern (GBA) [42]. These differences likely reflect factors related to urban expansion and natural conditions. Notably, the GBA experienced the most pronounced warming, associated with rapid urbanization and industrialization in recent years. To further explore the spatial distribution of these trends, global spatial autocorrelation analysis was performed using Moran’s I index. The resulting Moran’s I value (0.49), together with the associated Z-score (1722.83) and p-value (<0.001), indicates a strongly positive and statistically significant spatial clustering of LST trends. Based on this pronounced clustering pattern, a hotspot analysis was subsequently conducted (Figure 11b). In Figure 11b, red areas denote hot spots, representing statistically significant clusters of LST increases, whereas blue areas denote cold spots, corresponding to clusters of significant LST decreases. The spatial distribution of hotspots in the GBA is closely linked to the industrial characteristics and urban structures of individual cities [43]. Shenzhen, as a hub of high-tech industries and corporate headquarters, exhibits intense thermal loads from dense glass-clad high-rises, continuously operating data centers, and high-density developments on reclaimed land. Adjacent Dongguan, with its widespread industrial factories and informal “urban villages”, forms extensive contiguous heat islands. Foshan and Zhongshan’s manufacturing clusters release substantial industrial heat, compounded by expanding urban areas. Guangzhou’s new towns connect with these heat islands of Foshan and Dongguan, forming a giant thermal cluster. In contrast, cold spots occur in northern Huizhou’s forests, southern Jiangmen’s coastal wetlands, and Zhuhai’s outer islands, where shading, evaporative cooling, and sea–land breezes sustain lower temperatures. This spatial configuration suggests that urbanization has produced a contiguous warming core that expands outward from the central metropolitan zones, thereby promoting the UHI coalescence. These findings highlight the necessity of prioritizing hotspot areas—particularly in Guangzhou and Shenzhen—in land surface thermal environment planning to mitigate further UHI merging and intensification.

Figure 11.

(a) Spatial distribution of LST trend and (b) hotspot analysis from 2000 to 2020.

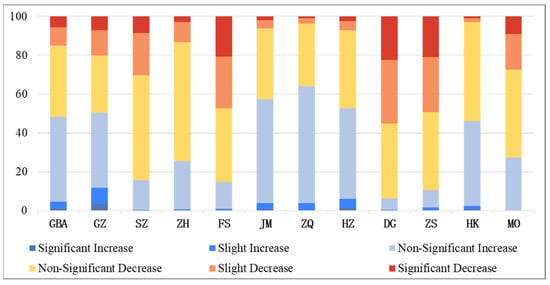

To quantitatively analyze the characteristics of the LST trends, the area proportions of different trend categories were calculated for each city (Figure 12). Overall, 51.72% of the GBA exhibited an increasing LST trend, among which 5.48% showed a highly significant increase, 9.37% showed a moderately significant increase, and 36.87% experienced a slight increase. Meanwhile, 48.23% of the area showed decreasing LST trends, including 43.56% with a slight decrease and 3.72% with a moderately significant decrease. These results indicate that approximately half of the GBA has undergone warming over the past two decades, although most warming was statistically insignificant, which is consistent with that of previous studies on the GBA [42,44,45].

Figure 12.

Area proportions of LST trend categories from 2000 to 2020 (%).

At the municipal scale, highly industrialized cities such as Dongguan, Zhongshan, and Foshan were dominated by warming trends, with warming areas accounting for 93.74%, 89.39%, and 85.22% of their total land area, respectively. The proportions of significantly increasing LST areas in these cities were 22.4%, 20.83%, and 20.73%, respectively. In contrast, Zhaoqing and Jiangmen exhibited the largest cooling areas, accounting for 64.05% and 57.33% of their total land area. Notably, Zhaoqing contributed the largest share of cooling areas across the entire GBA (36.27%), underscoring its important role in moderating the regional thermal environment. However, because Zhaoqing has the largest land area in the GBA, its warming area accounted for 18.97% of the total regional warming—second only to Huizhou, which had the highest proportion at 18.99%. Therefore, despite its strong cooling contribution, Zhaoqing’s role in the intensification of the GBA’s UHI effects cannot be ignored.

3.3. Relationship Between LCZs and LST

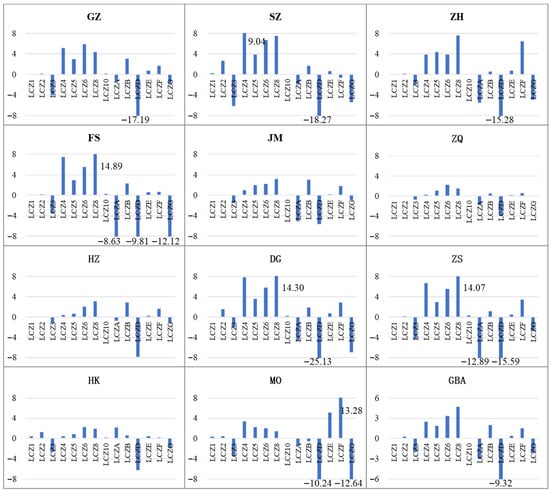

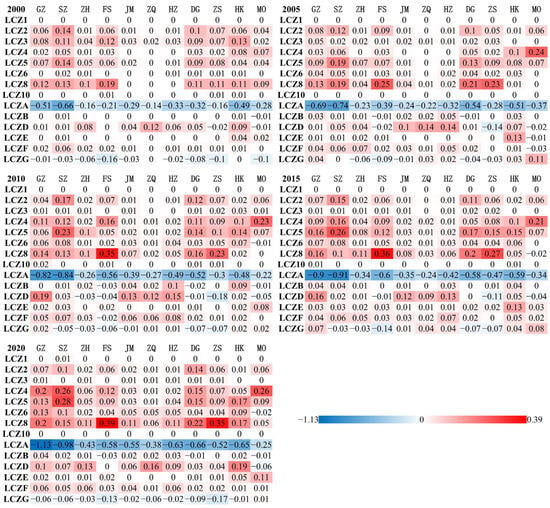

LCZCI values were calculated for each city in the GBA from 2000 to 2020 (Figure 13). Positive LCZCI values (red) indicate LCZ types that intensify the UHI effects—the darker the red, the stronger the warming impact. Conversely, negative LCZCI values (blue) indicate LCZ types that mitigate the UHI effect, with darker shades representing greater cooling capacity.

Figure 13.

LCZCI values from 2000 to 2020 (Color intensity denotes the LCZ contribution to the UHI effects. The darker the red, the stronger the warming impact. Conversely, the darker the blue, the stronger the cooling impact).

Overall, the impacts of LCZs on the UHI effects showed certain similar patterns from 2000 to 2020. First, all built types (LCZ1–10) exhibited contribution indices above zero, indicating that these types enhanced UHI intensity. Built-up areas are the primary locations of human activities and major sources of anthropogenic heat. With impervious surfaces dominating these zones and possessing low specific heat capacity, they experience greater surface heating under solar and anthropogenic energy inputs [4,5]. As a result, built types (LCZ1–10) constitute the primary contributors to UHI effects. Among land cover types (LCZA–G), only dense trees (LCZA) showed negative contribution indices, demonstrating their strong cooling effects through shading and evapotranspiration [46]. Forests in all bay areas produced a cooling effect, with temperature reductions below 0 °C, and the effect was most pronounced in the SFBA [47]. This is attributed to its Mediterranean climate, the high transpiration efficiency of deep-rooted native forests, and the multi-centered urban layout that channels cool air through valley corridors into the city. Moreover, dense trees (LCZA) consistently had the lowest contribution indices, while large low-rise (LCZ8) exhibited the highest values in most cities, suggesting that these two LCZ types exerted the most pronounced impacts on the UHI effects. This finding is consistent with that of previous studies on the GBA [7,40,48]. The cooling effectiveness of water (LCZG) is significantly lower than that of dense trees (LCZA), a finding consistent with studies conducted in the other three major global bay areas [42]. This indicates that, at the urban agglomeration scale, forest ecosystems provide more pronounced cooling services than water bodies. This difference primarily stems from the integrated ecological functions of forest vegetation in urban environments. Dense tree canopies effectively intercept solar radiation through shading, while continuous transpiration dissipates large amounts of heat. Together with their extensive spatial coverage, these processes jointly contribute to temperature reduction at the regional scale. In contrast, the cooling capacity of water bodies is more strongly constrained by their spatial extent—water (LCZG) covered less than 10% of the study area, whereas dense trees (LCZA) exceeded 55%. This magnitude difference limits the ability of water bodies to develop an effective cooling network within the built-up areas, unlike the contiguous distribution of forests, thereby constraining their overall effectiveness in mitigating the UHI effects. In addition, compact high-rise (LCZ1) and heavy industry (LCZ10) had contribution indices close to zero, likely due to their limited spatial extent in the region.

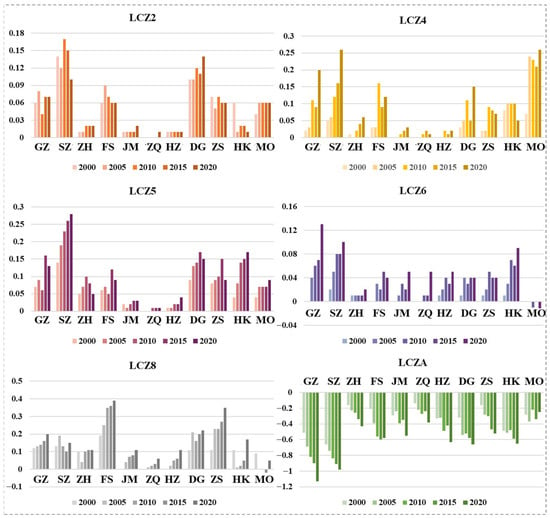

Temporal variations in LCZCI were also evident between 2000 and 2020. To highlight major trends, LCZ types with strong thermal effects—compact mid-rise (LCZ2), open high-rise (LCZ4), open mid-rise (LCZ5), open low-rise (LCZ6), large low-rise (LCZ8), and dense trees (LCZA)—were selected for further examination (Figure 14).

Figure 14.

Temporal Trends in LCZCI values for LCZ types with strong thermal effects.

From 2000 to 2020, the contribution indices of open high-rise (LCZ4), open mid-rise (LCZ5), open low-rise (LCZ6), and large low-rise (LCZ8) generally increased. According to the analysis of LCZ area changes during this period, these four LCZ types constitute the dominant types of newly developed built-up areas during urbanization. Their expanding spatial extent thus amplifies their thermal influence [48], resulting in rising LCZCI values. Across all cities, the increase in compact mid-rise areas remained below 3%, and consequently, their contribution indices did not exhibit a pronounced upward trend. Regarding dense trees (LCZA), although total area decreased to varying extents across GBA cities, the canopy closure and vegetation density increased, enhancing the cooling effects via shading and evapotranspiration [49,50]. This resulted in gradually lower contribution indices for dense trees (LCZA), indicating an increasingly strong mitigation effect on the UHI phenomenon. Jiangmen, Zhaoqing, and Huizhou generally exhibited lower contribution indices for most built types (LCZ1–10), suggesting weaker thermal impacts of urban development. In contrast, Guangzhou and Shenzhen displayed the highest absolute LCZCI values for most built types (LCZ1–10), highlighting the strong influence on UHI intensity. Notably, large low-rise (LCZ8) consistently exhibited the highest contribution indices in Foshan, Zhongshan, and Dongguan, reaching 0.39, 0.35, and 0.22 in 2020, respectively. This finding highlights that large low-rise (LCZ8) has become a major driver of UHI intensification in these cities. Large low-rise (LCZ8), a typical industrial zone, exhibits pronounced thermal effects due to the combined influence of its physical form, anthropogenic heat emissions, and material properties [51,52]. Its large roofs and pavements create extensive horizontal surfaces that absorb solar radiation efficiently, while low-rises are unable to provide effective shade to prevent direct sun exposure. Industrial processes (e.g., smelting, injection molding), dense freight traffic, and continuously operating air-conditioning units further increase heat load. Additionally, common materials such as asphalt, concrete, and metal roofing panels store heat during the day and release it slowly at night, creating a sustained “heater” effect. Thus, a systematic strategy is recommended for mitigating UHI effects. First, strictly control industrial land expansion and set appropriate minimum floor area ratios and greening requirements for new sites. Second, promote green retrofits of existing industrial zones by mandating high-albedo roofs and significantly reducing impervious surface coverage. Third, establish a multi-tiered ecological cooling system, including protective forest belts along park boundaries and continuous green ventilation corridors within the parks. By combining land-use regulation, factory retrofitting, and ecological infrastructure development, this approach provides a practical and measurable framework for comprehensive UHI mitigation in industrial areas. To further analyze the influence of dynamic LCZ transitions on LST, change matrices were constructed to quantify the thermal responses associated with inter-category transformations (Figure 15).

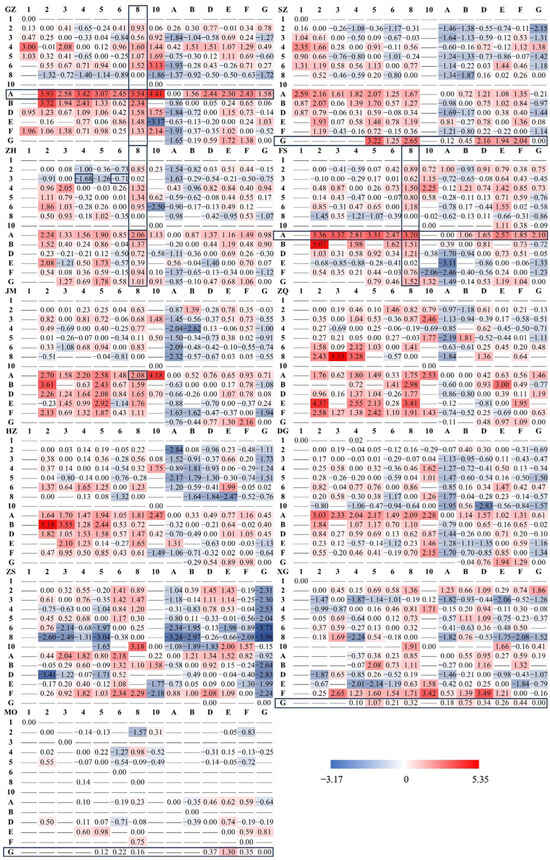

Figure 15.

The Impact of LCZ Changes on LST (Numbers and letters correspond to different LCZ categories. For example, the number 1 represents LCZ1, and the letter A corresponds to LCZA Key transition types are highlighted with bold outlines; color intensity denotes the magnitude of LST change, with red indicating significant warming and blue indicating significant cooling; blank cells represent transitions that did not occur during the study period).

Overall, LCZ transitions produced varying degrees of LST changes across the GBA. First, for conversions from land cover types (LCZA–G) to built types (LCZ1–10), more than 70% of these changes resulted in LST increases. Of the four meteorological stations, only Guangzhou Baiyun International Airport experienced an LCZ transition, from low plants (LCZD) to open high-rise (LCZ5). However, it showed the smallest temperature increase of just 0.16 °C. This phenomenon may be related to shading effects from high-rise buildings or the formation of local wind corridors, and it also highlights the limitations of meteorological station data, where the small sample size constrains accurate attribution of temperature change mechanisms. When dense trees (LCZA) were converted to other types, LST generally increased, with the largest rises occurring when they were transformed into built types (LCZ1–10). In Guangzhou and Foshan, these conversions resulted in temperature increases exceeding 2.45 °C. In addition, when other LCZ types were converted to large low-rise (LCZ8), more than 80% of these transitions led to warming, with all cases in Guangzhou, Zhuhai, and Foshan exhibiting warming. Furthermore, within built types (LCZ1–10), conversions to open high-rise (LCZ4) or open low-rise (LCZ6) generally resulted in slight LST reductions. For example, in Zhuhai, transitions from compact low-rise (LCZ3) to open high-rise (LCZ4) and open low-rise (LCZ6) decreased LST by 1.68 °C and 0.71 °C, respectively. This suggests that, under similar residential space demand, prioritizing open high-rise (LCZ4) and open low-rise (LCZ6) may help alleviate localized heat accumulation.

However, the thermal impacts of LCZ transitions varied significantly among cities. In Guangzhou, Shenzhen, and Zhuhai, over 40% of LCZ transitions caused LST changes greater than 1 °C, whereas in Macao, less than 5% exceeded this threshold. This indicates that LCZ transitions exerted stronger thermal influence in major mainland cities but had limited effects in Macao. In coastal cities such as Shenzhen, Hong Kong, and Macao, all conversions from water (LCZG) to other LCZs increased LST, with the greatest warming observed when water (LCZG) areas were replaced by bare rock or paved (LCZE) or built types (LCZ1–10). In Shenzhen, for example, converting water (LCZG) to open mid-rise (LCZ5) raised LST by 3.22 °C, emphasizing the essential role of water (LCZG) in mitigating UHI effects in coastal environments. For coastal cities such as Shenzhen, Hong Kong, and Macao, water bodies provide continuous cooling through sea–land breezes and substantial evaporation [52,53,54,55]. Once these water bodies are reclaimed and converted into impervious surfaces, their inherent cooling function is not only completely lost but also replaced by strong heat-retaining surfaces. This transformation obstructs the inland penetration of cool marine air via sea breezes, while the newly added impervious areas heat up rapidly under solar radiation. The resulting thermal effect compounds with the pre-existing urban heat environment, leading to significant LST increases. Shenzhen and Hong Kong exhibit significantly greater LST increases following the conversion of water (LCZG) to impervious surfaces compared to Macao. This difference is closely linked to the distinct urban development patterns, prevailing wind conditions, and urban morphologies of the three cities. Both Shenzhen and Hong Kong have undergone rapid and intensive urban expansion, with large-scale land reclamation giving rise to dense clusters of high-rise buildings that severely obstruct the dominant southeast monsoon and sea-breeze circulations, thereby reducing urban ventilation efficiency. Moreover, the dense arrangement of tall buildings and extensive impervious surfaces continuously releases stored heat, compounded by anthropogenic heat from air conditioning systems and other sources, further intensifying the UHI effects. In contrast, constrained by its limited land area, Macao has experienced more modest urban expansion and retains a higher proportion of open areas within its built environment, and thus results in relatively smaller LST increases. In Guangzhou, Zhuhai, Foshan, and Jiangmen, both the loss of dense trees (LCZA) and the expansion of large low-rise (LCZ8) contributed substantially to LST increases, with Guangzhou and Foshan experiencing the strongest warming. When dense trees (LCZA) were converted to other LCZs in these cities, LST increased by more than 1 °C on average.

Therefore, UHI mitigation strategies based on LCZs should be tailored to the specific characteristics and spatial dynamics of each city. For Guangzhou, Shenzhen, and Zhuhai, the thermal impacts of LCZ transitions should be carefully managed. For coastal cities such as Shenzhen, Hong Kong, and Macao, preserving water bodies is critical for maintaining cooling capacity. Meanwhile, in Guangzhou, Zhuhai, Foshan, and Jiangmen, strict control of deforestation and industrial land expansion is essential to alleviate regional heat accumulation.

4. Conclusions

In this study, we derived LCZ classification maps by a multi-feature local sample transfer method in the GBA from 2000 to 2020. We then systematically investigated the LCZ spatiotemporal changes and LST trends and quantitatively analyzed the LCZ change impacts on surface thermal environments based on the LCZCI and the LCZ transition matrix.

Our findings suggested that the proposed multi-feature local sample transfer approach can be used to achieve long-term LCZ mapping efficiently. LCZ maps for 2000, 2005, 2010, 2015, and 2020 achieved overall accuracies of 85.12%, 85.03%, 85.13%, 85.28%, and 85.02%, respectively, with change detection accuracy reaching 76.47%.

From 2000 to 2020, the total area of built types (LCZ1–10) in the GBA increased by 1.34%, with large low-rise (LCZ8) showing the largest growth of 4.72%. In contrast, compact low-rise (LCZ3) was the only category to decrease, at 2.02%. Foshan, Dongguan, and Zhongshan experienced the most pronounced increases in large low-rise (LCZ8), at 14.89%, 14.30%, and 14.07%, respectively, whereas Zhaoqing exhibited the smallest growth in built area, at 4.34%. LST changes exhibited a contiguous warming core expanding outward from the central metropolitan zones, promoting the coalescence of UHIs. Dongguan experienced the largest and most pronounced warming area, followed by Zhongshan and Foshan.

Large low-rise (LCZ8) and dense trees (LCZA) emerged as the most significant contributors to the UHI effects. Open high-rise (LCZ4), open mid-rise (LCZ5), open low-rise (LCZ6), and large low-rise (LCZ8) areas have increasingly amplified the UHI effects over time, whereas dense trees (LCZA) have progressively enhanced their cooling effect. LST generally increased when dense trees (LCZA) and water (LCZG) were converted to other LCZ types and when other types were converted to large low-rise (LCZ8). Conversely, transitions from other built types to open high-rise (LCZ4) or open low-rise (LCZ6) resulted in slight decreases in LST. Large low-rise (LCZ8) consistently served as the primary driver of UHI intensification in industrial cities such as Foshan, Zhongshan, and Dongguan. In coastal cities, including Shenzhen, Hong Kong, and Macao, the largest LST increases occurred when water (LCZG) areas were replaced by bare rock or paved (LCZE) or built types (LCZ1–10). To systematically mitigate UHI effects, cities should adopt differentiated spatial management strategies. Foshan, Zhongshan, and Dongguan should focus on intensive industrial land redevelopment, strictly limit new industrial developments, promote green infrastructure retrofits, and establish multi-tiered ecological cooling systems with protective forest belts and ventilation corridors. Shenzhen, Hong Kong, and Macao should protect and restore existing water bodies to maintain their natural cooling function as regional “cold sources”. Guangzhou, Zhuhai, Foshan, and Jiangmen should restrict conversion of forests to industrial or high-intensity uses, prioritizing the conservation of connected forest corridors and ecological patches to reinforce their role as peripheral cooling buffers.

It should be noted that, because the GBA is dominated by low-lying plains, this study excluded elevation as a factor in analyzing LST variations. This choice improves analytical clarity for the GBA but also introduces both opportunities and limitations when extending the method to other geographic regions. The strength of this approach lies in the generalizability of the LCZ framework and its associated thermal environment models, making it particularly effective for megacity regions with relatively flat terrain—such as the Yangtze River Delta. However, in mountainous cities with pronounced topographic gradients, such as Chongqing, elevation and slope become dominant controls on LST. In such settings, our method should be integrated with terrain-correction models to ensure robust interpretation. Therefore, while the approach demonstrates strong transferability in flat regions, its application in complex terrain requires appropriate model adaptation and additional topographic data adjustments.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.L. and D.W.; methodology, Y.L. and D.W.; software, Y.L. and D.W.; validation, Y.L. and D.W.; formal analysis, Y.L. and D.W.; investigation, Y.L. and D.W.; resources, Y.L. and D.W.; data curation, Y.L. and D.W.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.L. and D.W.; writing—review and editing, Y.L. and D.W.; visualization, Y.L. and D.W.; supervision, Y.L. and D.W.; project administration, Y.L. and D.W.; funding acquisition, Y.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Science Foundation Research Project of Wuhan Institute of Technology of China under Grant K2024033.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Stewart, I.D.; Oke, T.R. Local Climate Zones for Urban Temperature Studies. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 2012, 93, 1879–1900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, I.D.; Oke, T.R. Classifying urban climate field sites by “local climate zones”: The case of Nagano, Japan. In Proceedings of the Seventh International Conference on Urban Climate, Yokohama, Japan, 29 June–3 July 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Zou, Q.; Yang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Bai, Y.; Wang, J. Variation in community heat vulnerability for Shenyang City under local climate zone perspective. Build. Environ. 2025, 267, 112242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, F.; Cao, Y.; Sun, X.; Zou, B. Study on the contributions of 2D and 3D urban morphologies to the thermal environment under local climate zones. Build. Environ. 2024, 263, 111883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Wang, C.; Yang, H.; Ma, Z. How do morphology factors affect urban heat island intensity? an approach of local climate zones in a fast-growing small city, Yangling, China. Ecol. Indic. 2024, 161, 111972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Yang, J.; Yu, W.; Yu, H.; Xiao, X.; Xia, J.C. Spatial effect of urban morphology on land surface tempature from the perspective of local climate zone. Remote Sens. Appl. Soc. Environ. 2024, 36, 101324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, J.; Zhou, S.; Chung, L.C.H.; Chan, T.O. Evaluating land-surface warming and cooling environments across urban–rural local climate zone gradients in subtropical megacities. Build. Environ. 2024, 251, 111232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, J.; Ren, C.; Li, X.; Chung, L.C.H. Investigate the urban growth and urban-rural gradients based on local climate zones (1999–2019) in the Greater Bay Area, China. Remote Sens. Appl. 2022, 25, 100669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bechtel, B.; Alexander, P.J.; Beck, C.; Böhner, J.; Brousse, O.; Ching, J.; Demuzere, M.; Fonte, C.; Gál, T.; Hidalgo, J.; et al. Generating WUDAPT Level 0 data—Current status of production and evaluation. Urban. Clim. 2019, 27, 24–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Cai, M.; Ren, C.; Bechtel, B.; Xu, Y.; Ng, E. Detecting multi-temporal land cover change and land surface temperature in Pearl River Delta by adopting local climate zone. Urban. Clim. 2019, 28, 100455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xi, Y.; Wang, S.; Zou, Y.; Zhou, X.; Zhang, Y. Seasonal surface urban heat island analysis based on local climate zones. Ecol. Indic. 2024, 159, 111669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Li, Y.; Du, Y.; Wang, Y.; Liu, J.; Yang, L.; Huang, J. How to classify microclimates more validly and finely? A novel method for mapping local climate zone (LCZ) on micro-scales. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2025, 120, 106165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liua, S.; Shi, Q. Local climate zone mapping as remote sensing scene classification using deep learning: A case study of metropolitan China. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2020, 164, 229–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vavassori, A.; Oxoli, D.; Venuti, G.; Brovelli, M.A.; Siciliani De Cumis, M.; Sacco, P.; Tapete, D. A combined Remote Sensing and GIS-based method for Local Climate Zone mapping using PRISMA and Sentinel-2 imagery. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. 2024, 131, 103944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Q.; Ran, L.; Zhang, Y.; Guan, Q. Integrating geographic knowledge into deep learning for spatiotemporal local climate zone mapping derived thermal environment exploration across Chinese climate zones. ISPRS J. Photogramm. 2024, 217, 53–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Xu, Y.; Yang, J.; Wu, Z.; Zhu, H. Remote sensing of urban thermal environments within local climate zones: A case study of two high-density subtropical Chinese cities. Urban. Clim. 2020, 31, 100568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Middel, A.; Myint, S.W.; Kaplan, S.; Brazel, A.J.; Lukasczyk, J. Assessing local climate zones in arid cities: The case of Phoenix, Arizona and Las Vegas, Nevada. ISPRS J. Photogramm. 2018, 141, 59–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nassar, A.K.; Blackburn, G.A.; Whyatt, J.D. Dynamics and controls of urban heat sink and island phenomena in a desert city: Development of a local climate zone scheme using remotely-sensed inputs. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. 2016, 51, 76–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandamme, S.; Demuzere, M.; Verdonck, M.; Zhang, Z.; Van Coillie, F. Revealing Kunming’s (China) Historical Urban Planning Policies Through Local Climate Zones. Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 1731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, M.; Das, A. Assessing the relationship between local climatic zones (LCZs) and land surface temperature (LST)—A case study of Sriniketan-Santiniketan Planning Area (SSPA), West Bengal, India. Urban. Clim. 2020, 32, 100591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Wang, M. Multi-scale analysis of surface thermal environment in relation to urban form: A case study of the Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macao Greater Bay Area. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2023, 99, 104953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Wang, Y.; Chen, T. Spatiotemporal Impacts and Mechanisms of Multi-Dimensional Urban Morphological Characteristics on Regional Heat Effects in the Guangdong–Hong Kong–Macao Greater Bay Area. Land 2025, 14, 729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yujiao, D.; Yaodong, D.; Jiechun, W.; Jie, X.; Weisi, X. Spatiotemporal characteristics and driving factors of urban heat islands in Guangdong-Hong Kong-Marco Greater Bay Area. Chin. J. Ecol. 2020, 39, 2671–2677. [Google Scholar]

- Sen, P.K. Estimates of the Regression Coefficient Based on Kendall’s Tau. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1968, 63, 1379–1389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, A.; Zhang, M.; Chen, E.; Zhang, C.; Han, Y. Impact of seasonal global land surface temperature (LST) change on gross primary production (GPP) in the early 21st century. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2024, 110, 105572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cano, D.; Cacciuttolo, C.; Haller, A.; Rosario, C.; Guerra, J.C.; de Oliveira, G.G. Spatio-temporal tendencies of urban land surface temperature on the Andean piedmont under climate change: A case study of Metropolitan Lima, Peru (1986–2024). Remote Sens. Appl. Soc. Environ. 2024, 36, 101378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, P.; Zhang, L.; Yu, P. The marginal effect of landscapes on urban land surface temperature within local climate zones based on optimal landscape scale. Urban. Clim. 2024, 57, 102110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, W.; Wu, Q.; Qi, J.; Li, J.; Zhu, S.; Qiu, B. Spatiotemporal dynamics of land surface temperature and its drivers within the local climate zone framework. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2025, 133, 106859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haralick, R.M.; Shanmugam, K.; Dinstein, I. Textural Features for Image Classification. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man. Cybern. 1973, 3, 610–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, C.; Han, D.; Im, J.; Bechtel, B. Comparison between convolutional neural networks and random forest for local climate zone classification in mega urban areas using Landsat images. ISPRS J. Photogramm. 2019, 157, 155–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holobar, A.; Zazula, D. Multichannel Blind Source Separation Using Convolution Kernel Compensation. IEEE Trans. Signal Process. 2016, 55, 4487–4496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, R.D.; Kasischke, E.S. Change vector analysis: A technique for the multispectral monitoring of land cover and condition. Int. J. Remote Sens. 1998, 19, 411–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yager, R.R. On the specificity of a possibility distribution. Fuzzy Set Syst. 1992, 50, 279–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajadell, O.; Garcia-Sevilla, P.; Dinh, V.C.; Duin, R.P.W. Improving Hyperspectral Pixel Classification with Unsupervised Training Data Selection. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2014, 11, 656–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bala, R.; Prasad, R.; Yadav, V.P. Quantification of Urban Heat Intensity with Land Use/Land Cover Changes Using Landsat Satellite Data Over Urban Landscapes. Theor. Appl. Clim. 2021, 145, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Q.; Huang, J.; Yang, X.; Fang, C.; Liang, Y. Quantifying the seasonal contribution of coupling urban land use types on Urban Heat Island using Land Contribution Index: A case study in Wuhan, China. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2018, 44, 666–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, K.V.; Khandelwal, S.; Kaul, N. Downscaling of Coarse Resolution Land Surface Temperature Through Vegetation Indices Based Regression Models; Ghosh, J.K., Da Silva, I., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2020; pp. 625–636. [Google Scholar]

- Pu, R.; Bonafoni, S. Thermal infrared remote sensing data downscaling investigations: An overview on current status and perspectives. Remote Sens. Appl. Soc. Environ. 2023, 29, 100921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, W.; Chen, Y.; Zhou, J.; Wang, J.; Liu, W.; Voogt, J.; Zhu, X.; Quan, J.; Li, J. Disaggregation of remotely sensed land surface temperature: Literature survey, taxonomy, issues, and caveats. Remote Sens. Environ. 2013, 131, 119–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Yin, Y.; An, H.; Lei, J.; Li, M.; Song, J.; Han, W. Surface urban heat island and its relationship with land cover change in five urban agglomerations in China based on GEE. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 82271–82285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, M.; Wang, Y.; Xia, B.; Huang, G. Surface temperature variations and their relationships with land cover in the Pearl River Delta. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2020, 27, 37614–37625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Guan, Y.; Wu, X.; Zhang, J.; Li, R.; Lin, K.; Wang, Y. Revealing the dynamic effects of land cover change on land surface temperature in global major bay areas. Build. Environ. 2025, 267, 112266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, L.; Zhao, Y. Optimizing local climate zones to mitigate urban heat risk: A multi-models coupled approach in the context of urban renewal. Build. Environ. 2025, 282, 113282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, X.; Gao, F.; Liao, S.; Liu, Y.; Chen, W. Spatiotemporal evolution patterns of urban heat island and its relationship with urbanization in Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macao greater bay area of China from 2000 to 2020. Ecol. Indic. 2023, 146, 109817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, P.Y.; Chun, K.P.; Mijic, A.; Mah, D.N.; He, Q.; Choi, B.; Lam, C.K.C.; Yetemen, O. Spatially-heterogeneous impacts of surface characteristics on urban thermal environment, a case of the Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macau Greater Bay Area. Urban. Clim. 2022, 41, 101034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, M.; Li, M.; Liu, H. Optimizing cooling efficiency of urban greenspaces across local climate zones in Wuhan, China. Urban For. Urban Green. 2025, 105, 128691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, B.; Hussey, O.; Alexander, S. Quantifying highway expansion impact on urban heat island effect in San Francisco bay area. Cities 2026, 169, 106555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Yang, J.; Ma, S. Dynamic Changes of Local Climate Zones in the Guangdong–Hong Kong–Macao Greater Bay Area and Their Spatio-Temporal Impacts on the Surface Urban Heat Island Effect between 2005 and 2015. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Meng, Q.; Zhang, L.; Hu, D. Evaluation of urban green space in terms of thermal environmental benefits using geographical detector analysis. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. 2021, 105, 102610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masoudi, M.; Tan, P.Y.; Liew, S.C. Multi-city comparison of the relationships between spatial pattern and cooling effect of urban green spaces in four major Asian cities. Ecol. Indic. 2019, 98, 200–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, B.; Pan, J. How do 2D and 3D urban morphology impact spatial patterns of thermal environment? A nested multi-scale local climate zone perspective. Build. Environ. 2026, 288, 114014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Yang, C.; Zhou, W.; Liu, L.; Wang, C. Assessing heat-related health risk based on the hazard–exposure–vulnerability framework in Shenzhen, China: A block-level local climate zone perspective. J. Clean. Prod. 2025, 534, 147036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Shen, Y.; Fu, W.; Zheng, D.; Huang, P.; Li, J.; Lan, Y.; Chen, Z.; Liu, Q.; Xu, X. How does 2D and 3D of urban morphology affect the seasonal land surface temperature in Island City? A block-scale perspective. Ecol. Indic. 2023, 150, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Gao, J.; Zhao, J.; Guo, F.; Bai, J.; Wang, Z.; Zhu, P. Applicability of local climate zones in assessing urban heat risk—A survey of coastal city. Cities 2025, 164, 106068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Zhang, Y.; Zhu, E.; Che, Y.; Wu, Y. Segregation of sea breezes and cooling effects on land-surface temperatures in a coastal city. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2025, 118, 106017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).