Between Memory and Everyday Life: Urban Design and the Role of Citizens in the Management of the Memorial Park “October in Kragujevac”

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Forming the Collective Memory

1.2. Šumarice Memorial Park—A Site of Memory Bearing Witness to the Past

1.3. Participation and Its Limitations in the Local Context

1.4. Current Management of the Memorial Park October in Kragujevac

2. Materials and Methods

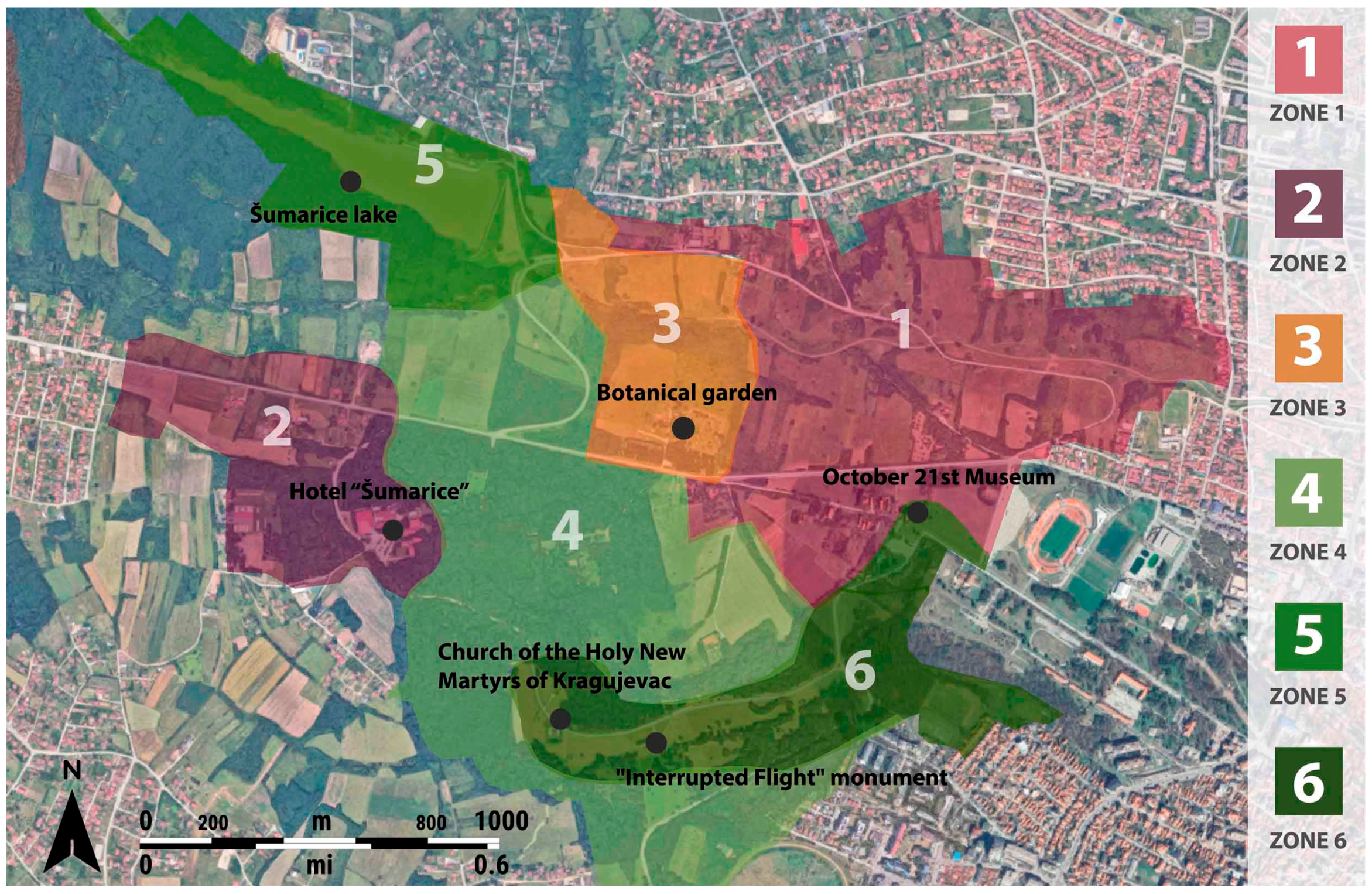

2.1. Research Area

2.2. Methodological Framework

2.3. Data Collection

2.3.1. Critical Analysis of Primary Sources

2.3.2. Survey-Based Data Collection

2.3.3. Survey Structure

3. Results

3.1. Interpretation of Available Historical Records

3.1.1. Content and Design of the Memorial Park

3.1.2. Management of the Memorial Park

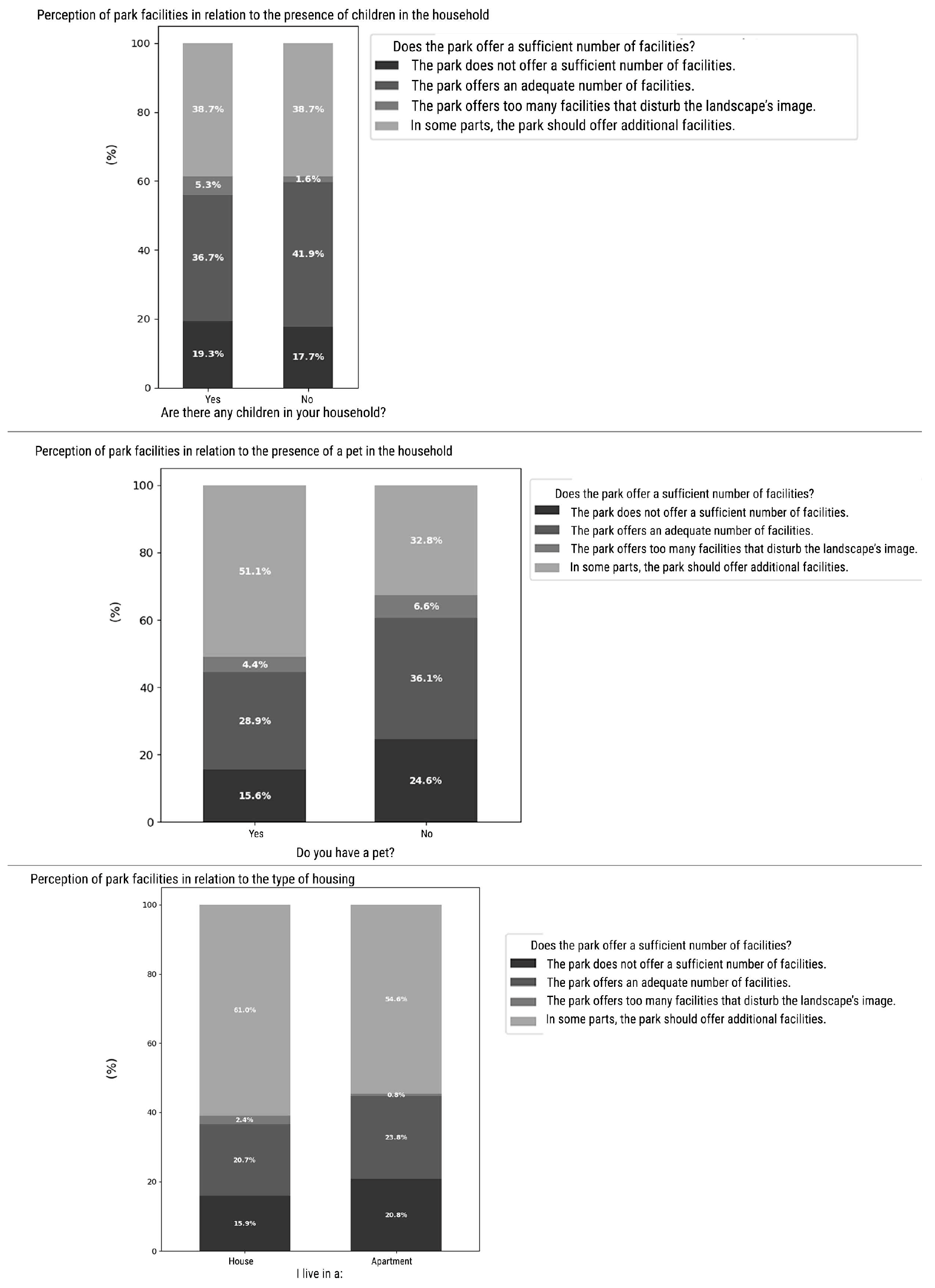

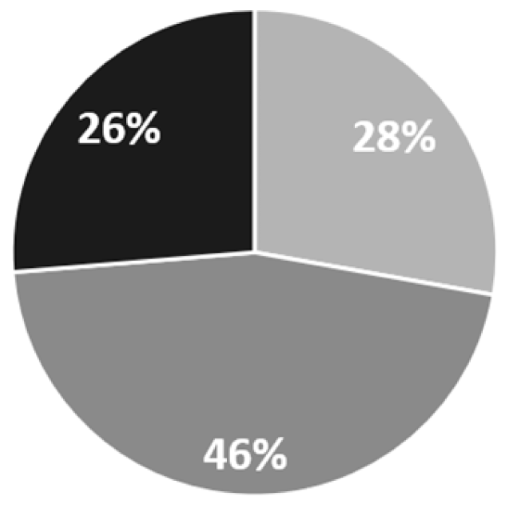

3.2. Survey Results

3.2.1. Current Perception of the Memorial Park by Users

3.2.2. Visions in the Near Future and the Need for Additional Content

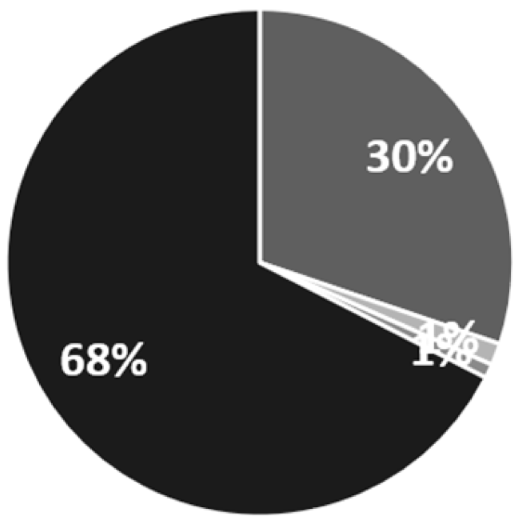

3.2.3. Users’ Willingness to Participate

4. Discussion

4.1. Survey Findings

4.1.1. Balancing Preservation and Activation

4.1.2. Management Structures and Participatory Potential

4.2. Everyday Use and Symbolic Preservation

- Greenery should be of great importance and deserves great attention, not only as an element of the landscape and landscape, but as part of the integrated Green System in the city, which is a response to the ecological needs of the city in terms of reducing heat extremes, influences activities in terms of the choice of transportation, recreation and rest, and also represents the basis for the development of biodiversity in the city. Greenery fosters interaction among people from diverse social backgrounds within the memorial park, thereby promoting social integration. The further development of the Botanical Garden should contribute to the new development cycle in the development of the memorial park October in Kragujevac.

- Increasing urban mobility by building new bicycle and pedestrian paths, new pedestrian access points in Memorial Park, and rental points for electric vehicles: Segways, electric scooters, bicycles, etc., is also a necessary element to achieve the connection between Memorial Park and the city. The construction of a new Visitor Center and several bus parking lots to accommodate different groups of visitors would significantly improve the functioning of the park.

- A scientific comprehensive approach should be maintained in the assessment of valuable regional resources, but a mechanism must be developed that also recognizes the need to adapt certain areas under greenery to people, enabling basic catering services but preserving the emotion of the victims. The key is to achieve a high degree of integration of place memory, culture, art, and recreation.

- Develop a wider network of tourist trails and road paths, considering the regional and international aspects of the famous places dedicated to the victims of the First and Second World Wars.

- Establish professional management that will ensure a sustainable model of financing the maintenance of the space, which will ensure private–public cooperation, the participation of citizens, artists, experts, historians, and others in the maintenance of the memorial park.

- High-quality new construction development and landscape design of memorial spaces based on contemporary world principles would be made possible by the adoption of the proper national regulations for the development of special urban regulation plans for protected cultural heritage, including guidelines for defining protective zones with the mandatory participation of citizens and pertinent stakeholders.

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | Articles 41, 42, 43, 44, 61, 62, 63, 64, 65, 66, and 67 of the Rulebook guarantee citizens the right to participate in two stages of the decision-making process during the preparation of urban and spatial plans. However, although citizens are formally granted the opportunity to submit comments, the participation described within the legal framework does not entail dialogue, workshops, or any form of proposal-making; the feedback on citizens’ suggestions is limited to one of the following responses: “accepted,” “not accepted,” “partially accepted,” or “not applicable.” |

References

- Lewicka, M. Place Attachment, Place Identity, and Place Memory: Restoring the Forgotten City Past. J. Environ. Psychol. 2008, 28, 209–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djukić, A.; Stupar, A. Brief Insight into Historical Urban Transformations: Design of Public Spaces vs. Myth, Ritual and Ideology. Spatium 2001, 7, 19–23. [Google Scholar]

- Zerubavel, E. Time Maps: Collective Memory and the Social Shape of the Past; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2003; ISBN 978-0-226-98152-9. [Google Scholar]

- Djukic, A.; Vlastos, T.; Joklova, V. Liveable Open Public Space—From Flaneur to Cyborg. In CyberParks—The Interface Between People, Places and Technology: New Approaches and Perspectives; Smaniotto Costa, C., Šuklje Erjavec, I., Kenna, T., de Lange, M., Ioannidis, K., Maksymiuk, G., de Waal, M., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 38–49. ISBN 978-3-030-13417-4. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, O.; Garde-Hansen, J. Geography and Memory: Explorations in Identity, Place and Becoming; Palgrave Macmillan memory studies; Palgrave Macmillan: Basingstoke, UK, 2012; ISBN 978-0-230-29299-4. [Google Scholar]

- Boyer, M.C. The City of Collective Memory: Its Historical Imagery and Architectural Entertainments; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1994; ISBN 978-0-262-02371-9. [Google Scholar]

- Heath-Kelly, C. Memorial Sites: Siting and Sighting Memory. In Handbook on the Politics of Memory; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2023; pp. 216–227. [Google Scholar]

- Nora, P. Between Memory and History: Les Lieux de Mémoire. Representations 1989, 26, 7–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, N. Cast in Stone: Monuments, Geography, and Nationalism. Environ. Plan D 1995, 13, 51–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffiths, H.M. Enacting Memory and Grief in Poetic Landscapes. Emot. Space Soc. 2021, 41, 100822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomanić, B. Mass Shootings in Kragujevac during and after World War II (1941–1945). Testimonies and Memorization. Istorija 20. Veka 2020, 1, 83–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jorgić, K. The Kragujevac Massacres and the Jewish Persecution of October 1941. Serbian Stud. J. N. Am. Soc. Serbian Stud. 2013, 27, 79–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trifunović, V. Građenje Kragujevca od 1945. do 1965. Godine [Construction of Kragujevac from 1945 to 1965]; Udruženje “Kragujevac naš grad”; Ustanova kulture “Koraci”: Kragujevac, Serbia, 2019; ISBN 978-86-86685-76-6. [Google Scholar]

- Mitrović, M.; Tomić, R.; Klaić, S. Idejni Projekat Za Spomen Park u Kragujevcu [Conceptual Design for the Memorial Park in Kragujevac]. [Unpublished Architectural Design, Internal Archive PE Urban Planning—Kragujevac, Kragujevac, Serbia]. Projektbiro, Belgrade, Serbia, 1955.

- Mitrović, M.; Tomić, R. Generalni Plan Uređenja Spomen Parka u Kragujevcu [General Plan for the Development of the Memorial Park in Kragujevac]. [Unpublished Urban Plan, Internal Archive PE Urban Planning—Kragujevac, Kragujevac, Yugoslavia]. Projektbiro, Belgrade, Yugoslavia, 1966.

- Thomas, S.; Herva, V.-P.; Seitsonen, O.; Koskinen-Koivisto, E. Dark Heritage. In Encyclopedia of Global Archaeology; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 1–11. ISBN 978-3-319-51726-1. [Google Scholar]

- Zakon o Kulturnom Nasleđu, [Law on Cultural Heritage], “Official Gazette of the RS”, No. 129/2021. Belgrade, Serbia. Available online: https://pravno-informacioni-sistem.rs/eli/rep/sgrs/skupstina/zakon/2021/129/11/reg (accessed on 15 September 2025).

- Mulderig, B.; Carriere, K.R.; Wagoner, B. Memorials and Collective Memory: A Text Analysis of Online Reviews. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 2025, 64, e12827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assmann, A. Erinnerungsräume: Formen und Wandlungen des kulturellen Gedächtnisses; C.H. Beck Kulturwissenschaft; Beck: München, Germany, 2006; ISBN 978-3-406-50961-2. [Google Scholar]

- Čolić, N.; Dželebdžić, O. Praksa Participativnog Planiranja u Srbiji—Stanje i Perspektive [The Practice of Participatory Planning in Serbia-Current Situation and Future Perspectives]. In Proceedings of the International Scientific-Professional Conference 14th Summer School of Urbanism, Bijeljina, Bosnia and Herzegovina, 31 May–2 June 2018; Serbian Town Planners Association and Republic Geodetic Authority: Bijeljina, Bosnia and Herzegovina, 2018; pp. 105–111. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.; Edelenbos, J.; Gianoli, A. Identifying Modes of Managing Urban Heritage: Results from a Systematic Literature Review. City Cult. Soc. 2024, 36, 100560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colomer, L. Participation and Cultural Heritage Management in Norway. Who, When, and How People Participate. Int. J. Cult. Policy 2024, 30, 728–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnstein, S.R. A Ladder Of Citizen Participation. J. Am. Inst. Plan. 1969, 35, 216–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burns, D.; Hambleton, R.; Hoggett, P. The Politics of Decentralisation: Revitalising Local Democracy; Public policy and politics; Macmillan: Basingstoke, UK, 1994; ISBN 978-0-333-52163-2. [Google Scholar]

- Fung, A. Varieties of Participation in Complex Governance. Public Adm. Rev. 2006, 66, 66–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macintosh, A. Characterizing E-Participation in Policy-Making. In Proceedings of the 37th Annual Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, Big Island, HI, USA, 5–8 January 2004; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2004; p. 10. [Google Scholar]

- Haddad, N.A.; Fakhoury, L.A. Towards Developing a Sustainable Heritage Tourism and Conservation Action Plan for Irbid’s Historic Core. Archnet-IJAR 2016, 10, 36–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pravilnik o Sadržini, Načinu i Postupku Izrade Dokumenata Prostornog i Urbanističkog Planiranja [Rulebook on the Content, Manner, and Procedure for the Preparation of Spatial and Urban Planning Documents, “Official Gazette of the RS”, No. 32/2019 and 47/2025], Belgrade, Serbia. Available online: https://www.paragraf.rs/propisi/pravilnik-o-sadrzini-nacinu-postupku-izrade-dokumenata-prostornog-urbanistickog-planiranja.html (accessed on 15 September 2025).

- Meerkerk, J. Understanding the Governing of Urban Commons: Reflecting on Five Key Features of Collaborative Governance in Zero Waste Lab, Amsterdam. Int. J. Commons 2024, 18, 397–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallance, S.; Carlton, S.; Hoddinott, W. Urban Governance: Public Space Management and “What’s in Common”. Urban Des. Int. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Generalni Urbanistički Plan “Kragujevac 2030”, [The General Urban Plan of Kragujevac 2030], “Offical Gazette of the City of Kragujevac”, No. 24/23. Kragujevac, Serbia. Available online: https://kragujevac.ls.gov.rs/tekst/57457/generalni-urbanisticki-plan-kragujevac-2030.php (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- Odluka o Održavanju Javnih Zelenih Prostora [Decision on the Maintenance of Public Green Areas], “Offical Gazette of the City of Kragujevac”, No. 39/20. Kragujevac, Serbia. Available online: http://demo.paragraf.rs/demo/combined/Old/t/t2021_01/KG_039_2020_003.htm (accessed on 10 September 2025).

- Odluka o Preuzimanju Prava i Dužnosti Osnivača Nad Ustanovom Spomen Park “Kragujevački Oktobar” u Kragujevcu [Decision on the Transfer of Founding Rights and Obligations over the Institution “Memorial Park October in Kragujevac], “Offical Gazette of the City of Kragujevac”, Nos. 33/09, 34/10 and 11/18. Kragujevac, Serbia. Available online: http://demo.paragraf.rs/demo/combined/Old/t/t2018_05/t05_0061.htm (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Brkić, S.; Đorđević, N.; Davidović, J.; Kamber, L.; Popivoda, M.; Babić, K.; Stojilović, M. Spomenica: Spomen-Park “Kragujevački Oktobar (1953–2016)” [Memorial Book: The Memorial Park “October in Kragujevac” (1953–2016)]; The Memorial Park “October in Kragujevac”: Kragujevac, Serbia, 2016; ISBN 978-86-80947-44-0. [Google Scholar]

- Committee for the Establishment of the Memorial Park to the October Victims. Zapisnik Sa Sednice Odbora Za Izgradnju “Spomen Parka” u Kragujevcu [Minutes from the Meeting of the Committee for the Establishment of the “Memorial Park” in Kragujevac]. [Unpublished Minutes, Historical Archives of Šumadija, Kragujevac, Serbia, Lib. Cat. Spomen Park, Box I-IV. Loc. 4.2.92] 1953.

- Andrejević-Kun, Đ.; Krstić, A.; Stojanović, B. Izveštaj Stručne Komisije: Predlog Za Podizanje Spomen Parka Oktobarskim Žrtvama u Kragujevcu [Report of the Expert Committee: Proposal for the Establishment of a Memorial Park to the October Victims in Kragujevac]. [Unpublished Report, Historical Archives of Šumadija, Kragujevac, Yugoslavia, Lib. Cat. Spomen Park, Box I-IV. Loc 4.2.92] 1952.

- Martinović, M. Exhibition Space of Remembrance: Rhythmanalysis of Memorial Park Kragujevački Oktobar. SAJ-Serbian Archit. J. 2013, 5, 306–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preiser, W.F.E. Post-occupancy Evaluation: How to Make Buildings Work Better. Facilities 1995, 13, 19–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, I. Post-Occupancy Evaluation—Where Are You? Build. Res. Informat. 2001, 29, 158–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Lee, J.; Jiang, B.; Kim, G. Revitalization of the Waterfront Park Based on Industrial Heritage Using Post-Occupancy Evaluation-A Case Study of Shanghai (China). Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 9107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Wang, S.; Wang, Z.; Chen, G. Contemporary Demands of Scenes in Urban Historic Conservation Areas: A Case Study of Subjective Evaluations from Foshan, China. Buildings 2024, 14, 2837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- City&Me | Instagram, Facebook, TikTok. Available online: https://linktr.ee/cityandme (accessed on 14 October 2025).

- People’s Council of Kragujevac Region. Rešenje o Eksprorpijaciji u Korist Države FNRJ Uz Zakonsku Naknadu Za Potrebe Opštine Kragujevac, a u Cilju Izvršenja Regulacionog Plana Grada i Podizanja “Spomen Parka” [Decision on the Expropriation in Favor of the FNRY with Legal Compensation for the Needs of the Municipality of Kragujevac, with the Aim of Implementing the Urban Regulation Plan and Building the “Memorial Park”]. [Unpublished Document, Historical Archives of Šumadija, Kragujevac, Yugoslavia, Lib. Cat. Spomen Park, Box I-IV. Loc 4.2.92]. 1956.

- Petrović, Z. (Ed.) Vodič kroz Spomen-Park Kragujevački Oktobar [Guide to the Kragujevac October Memorial Park]; Spomen-Park Kragujevački Oktobar: Kragujevac, Serbia, 2012; ISBN 978-86-80947-37-2. [Google Scholar]

- Directorate for Urban Planning and Construction Kragujevac. Kragujevac 1974–1977: Izmena i Dopuna GUP-a [Kragujevac 1974–1977: Amendment of the General Urban Plan]. [Unpublished Urban Plan, Internal Archive, PE Urban Planning—Kragujevac, Kragujevac, Yugoslavia] 1973.

- City Assembly of Kragujevac. Odluka o Proglašenju Memorijalnog Prostora Spomen-Parka u Kragujevcu Za Kulturno Dobro [Decision on the Declaration of the Memorial Area of the Memorial Park in Kragujevac as a Cultural Heritage Site], “The Official Gazette of the Šumadija and Pomoravlje District”, No. 18/79. Kragujevac, Yugoslavia. 1979.

- Assembly of the Socialist Republic of Serbia. Odluka o Utvrđivanju Nepokretnih Kulturnih Dobara Od Izuzetnog Značja i Od Velikog Značaja [Decision on the Designation of Immovable Cultural Assets of Exceptional and Great Importance]. “The Official Gazette of Socialist Republic of Serbia”, No 14/79. Belgrade, Yugoslavia. 1979.

- Directorate for Urban Planning and Construction. Generalni Urbanistički Plan Kragujevac 2000 [General Urban Plan Kragujevac 2000]. [Unpublished Urban Plan, Internal Archive PE Urban Planning—Kragujevac, Kragujevac, Yugoslavia] 1980.

- City Assembly of Kragujevac. Generalni Urbanistički Plan Kragujevac 2005 [General Urban Plan Kragujevac 2005], “The Offical Gazette of City of Kragujevac”, No. 13/91. Kragujevac, Yugoslavia. 1991.

- City Assembly of Kragujevac. Generalni Plan Kragujevac 2015 [General Urban Plan Kragujevac 2015], “The Offical Gazette of City of Kragujevac”, No. 3/05. Kragujevac, Serbia and Montenegro. 2005.

- City Assembly of Kragujevac. Plan Generalne Regulacije “Centralni Gradski Park Šumarice” [General Regulation Plan “Central City Park Šumarice”], “The Offical Gazette of City of Kragujevac”, No. 24/19. Kragujevac, Serbia. 2019.

- Federal People’s Assembly. Uredba o Ustanovama Sa Samostalnim Finansiranjem [Regulation on Self-Financed Institutions], “The Official Gazette of Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia”, No. 51/53, Belgrade, Yugoslavia 1953.

- Committee for the Establishment of the Memorial Park to the October Victims. Izveštaj o Radu Odbora Za Izgradnju Spomen-Parka u 1954 Godini [Report on the Work of the Committee for the Establishment of the Memorial Park in 1954]. [Unpublished Report, Historical Archives of Šumadija, Kragujevac, Serbia, Lib. Cat. Spomen Park, Box I-IV. Loc. 4.2.92] 1954.

- Memorial Park “October in Kragujevac”. Statut Ustanove Spomen-Park “Kragujevački Oktobar [Statute of the Institution Memorial Park “October in Kragujevac”]. “The Official Gazette of the City of Kragujevac”, No. 36/22. Kragujevac, Serbia. 2022.

- Burghardt, R.; Kirn, G. Yugoslavian Partisan Memorials: Hybrid Memorial Architecture and Objects of Revolutionary Aesthetics. Signal 2014, 3, 98–131. [Google Scholar]

- Spasić, I.; Backović, V. Gradovi u Potrazi Za Identitetom [Cities in Search of Identity]; Univerzitet u Beogradu-Filozofski fakultet, Institut za sociološka istraživanja: Belgrade, Serbia, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Kirn, G.; Burghardt, R. Jugoslovenski Partizanski Spomenici: Između Revolucionarne Politike i Apstraktnog Modernizma. JugoLink Pregl. Postjugoslovenskih Istraživanja 2012, 2, 7–20. [Google Scholar]

- Kirn, G.; Burghardt, R. Yugoslavian Partisan Memorials: The Aesthetic Form of the Revolution as a Form of Unfinished Modernism. In Unfinished Modernization: Between Utopia and Pragmatism; UHA/CCA, Croatian Architects’ Association: Zagreb, Croatia, 2012; pp. 84–95. ISBN 978-953-6646-24-1. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. Recommendation on the Historic Urban Landscape. UNESCO Publishing. Paris, France. Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/document/160163 (accessed on 15 September 2025).

- UNESCO The HUL Guidebook: Managing Heritage in Dynamic and Constantly Changing Urban Environments; a Practical Guide to UNESCO’s Recommendation on the Historic Urban Landscape. UNESCO Publishing. Paris, France. Available online: https://www.hulballarat.org.au/resources/HUL%20Guidebook_2016_FINALWEB.pdf (accessed on 15 September 2025).

- Ginzarly, M.; Houbart, C.; Teller, J. The Historic Urban Landscape Approach to Urban Management: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2019, 25, 999–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandarin, F.; Van Oers, R. The Historic Urban Landscape: Managing Heritage in an Urban Century; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Pereira Roders, A.; Bandarin, F. (Eds.) Reshaping Urban Conservation: The Historic Urban Landscape Approach in Action; Creativity, Heritage and the City; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2019; Volume 2, ISBN 978-981-10-8886-5. [Google Scholar]

- Rao, K. A New Paradigm for the Identification, Nomination and Inscription of Properties on the World Heritage List. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2010, 16, 161–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| No. | Question 1 | X * | Question 2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 01 | Are there any children in your household? | X | Do you think the park offers enough facilities (**)? |

| 02 | Do you have a pet? | X | Do you think the park offers enough facilities? |

| 03 | Do you live in a house or an apartment? | X | Do you think the park offers enough facilities? |

| 04 | Do you live in the immediate vicinity of the Kragujevac October Memorial Park? | X | Which facilities would you like to have at the location? * Multiple answers possible |

| 05 | Are there any children in your household? | X | Which facilities would you like to have at the location? * Multiple answers possible |

| 06 | Do you think the park offers enough facilities? * Only for respondents who think that the park does not offer enough facilities or that certain parts lack sufficient facilities | X | There is no need to change anything—the existing condition should be preserved (Likert scale: 1—strongly disagree, 5—strongly agree) |

| 07 | Do you live in the immediate vicinity of the Kragujevac October Memorial Park? | X | Would you be willing to participate as a member of a working group in planning, decision-making, and management? |

| 08 | What is your highest level of education? | X | Would you be willing to serve as a member of a working group involved in the processes of planning, decision-making, and management? |

| The Steering Board | The Supervision Board | The Head | Museum service | Expert council | Museum “21 October” | Program Councils |

| Gallery service | Artistic council | Gallery “Bridges of the Balkans” | Artistic Council of the event | |||

| Construction, development, and maintenance service | ||||||

| No. * | χ2 | p-Value | Cramer’s V | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 01 | 3.770 a | 0.387 | 0.189 | There is no statistically significant correlation. weak association |

| 02 | 0.128 a | 0.988 | 0.035 | There is no statistically significant correlation. very weak correlation |

| 03 | 0.422 a | 0.936 | 0.063 | There is no statistically significant correlation. very weak association |

| 04 | - | - | - | Due to the response format (multiple choice), the chi-square test is not applicable; a graphical analysis was conducted as the basis for concluding. |

| 05 | - | - | - | Due to the response format (multiple choice), the chi-square test is not applicable; a graphical analysis was conducted as the basis for concluding. |

| 06 | - | - | - | Due to the response format (multiple choice), the chi-square test is not applicable; a graphical analysis was conducted as the basis for concluding. |

| 07 | 5.370 a | 0.497 | 0.159 | There is no statistically significant correlation. weak association |

| 08 | 9.566 a | 0.654 | 0.173 | There is no statistically significant correlation. weak association |

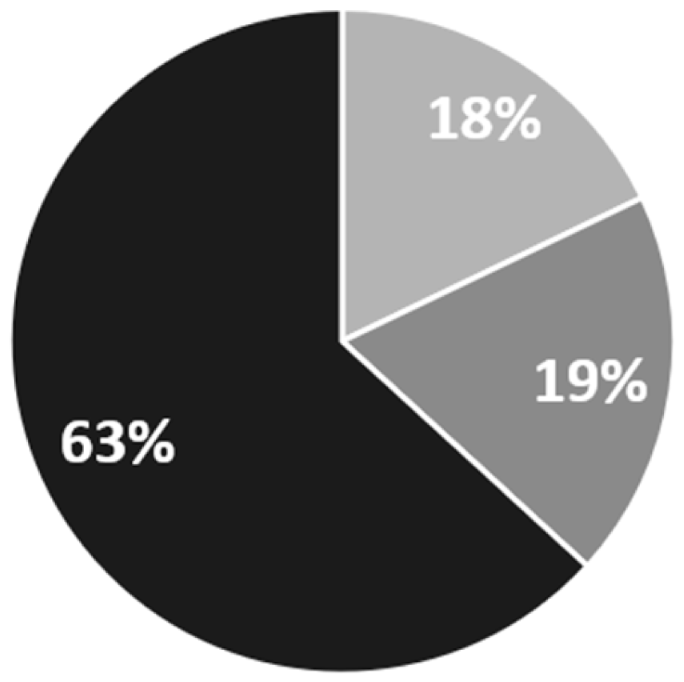

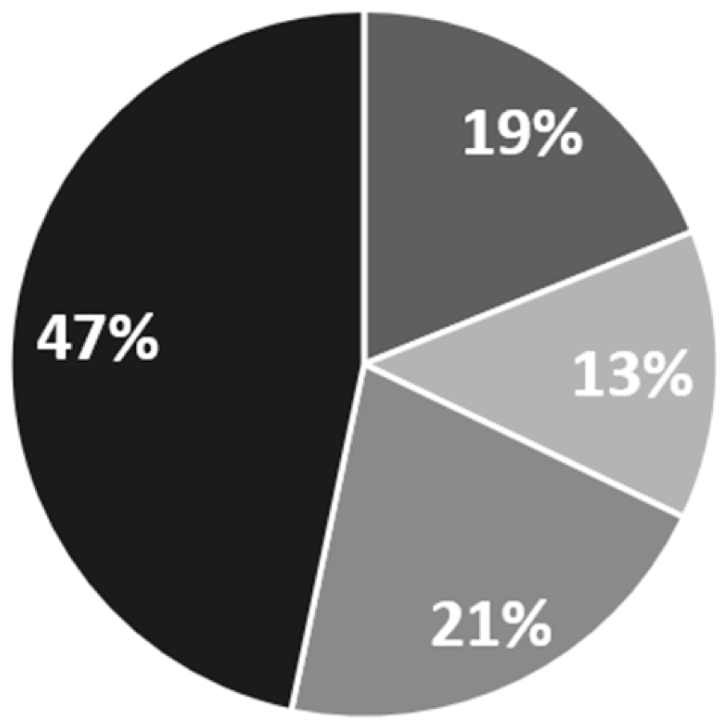

| No. | Chart |  |  |  |  |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 01 |  | The park does not offer a sufficient number of facilities. | The park offers too many facilities that disturb the landscape image. | he park offers an adequate number of facilities. | In some areas, the park should offer additional facilities |

| 02 |  | The park is insufficiently equipped. | The park is over-equipped—the number of benches and other street furniture disrupts the landscape image. | The park is adequately equipped. | In some areas, the park should be better equipped. |

| 03 |  | Disagree | Don’t know | Agree | - |

| 04 |  | - | Don’t know | No changes are needed | Some changes are needed |

| 05 |  | Contributes moderately | Does not contribute much | Does not contribute at all | Contributes greatly |

| 06 |  | No additional facilities are needed. | Don’t know | Additional facilities are needed | - |

| 07 |  | No additional facilities are needed. | Don’t know | Additional facilities are needed | - |

| 08 |  | No additional facilities are needed. | Don’t know | Additional facilities are needed | - |

| 09 |  | No additional facilities are needed. | Don’t know | Additional facilities are needed | - |

| 10 |  | No additional facilities are needed. | Don’t know | Additional facilities are needed | - |

| 11 |  | No additional facilities are needed. | Don’t know | Additional facilities are needed | - |

| 12 |  | The proposed improvement of facilities disrupts the image of the memorial park | Don’t know | The proposed improvement of facilities enhances the image of the memorial park | - |

| 13 |  | The proposed improvement of facilities disrupts the image of the memorial park | Don’t know | The proposed improvement of facilities enhances the image of the memorial park | - |

| 14 |  | The proposed improvement of facilities disrupts the image of the memorial park | Don’t know | The proposed improvement of facilities enhances the image of the memorial park | - |

| 15 |  | The proposed improvement of facilities disrupts the image of the memorial park | Don’t know | The proposed improvement of facilities enhances the image of the memorial park | - |

| 16 |  | The proposed improvement of facilities disrupts the image of the memorial park | Don’t know | The proposed improvement of facilities enhances the image of the memorial park | - |

| 17 |  | The proposed improvement of facilities disrupts the image of the memorial park | Don’t know | The proposed improvement of facilities enhances the image of the memorial park | - |

| 18 |  | - | The park would be better maintained if it had more facilities, and consequently more users who would contribute to its upkeep | The park is not adequately maintained | The park is adequately maintained |

| 19 |  | Yes, I am willing to participate, but to a limited extent | No, because I believe that citizens are not qualified to participate | No, because I believe that without political support, citizens’ wishes cannot be recognized | Yes, I am willing to participate |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Djukic, A.; Jović, E.; Stefanović, J.; Mandić, L.; Trifunović, V. Between Memory and Everyday Life: Urban Design and the Role of Citizens in the Management of the Memorial Park “October in Kragujevac”. Land 2025, 14, 2273. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14112273

Djukic A, Jović E, Stefanović J, Mandić L, Trifunović V. Between Memory and Everyday Life: Urban Design and the Role of Citizens in the Management of the Memorial Park “October in Kragujevac”. Land. 2025; 14(11):2273. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14112273

Chicago/Turabian StyleDjukic, Aleksandra, Emilija Jović, Jovana Stefanović, Lazar Mandić, and Veroljub Trifunović. 2025. "Between Memory and Everyday Life: Urban Design and the Role of Citizens in the Management of the Memorial Park “October in Kragujevac”" Land 14, no. 11: 2273. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14112273

APA StyleDjukic, A., Jović, E., Stefanović, J., Mandić, L., & Trifunović, V. (2025). Between Memory and Everyday Life: Urban Design and the Role of Citizens in the Management of the Memorial Park “October in Kragujevac”. Land, 14(11), 2273. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14112273