Abstract

For several years now, urban planning practices have been marked by the proliferation of catchwords, serving as kinds of brands that promote the idea of easy, ready-made, one-size-fits-all ways to tackle planning problems. Among the most recent is the ‘15-Minute City’—sometimes presented as a saving ‘solution’ to the settlement issues of our time. This article develops a multifaceted discussion of the uncritical use of the 15-Minute City urban model through ten main objections. In a nutshell, these objections emphasize, first, the unavoidable contextual dimension of places when planning for proximity: urban conditions vary greatly in terms of space, society, and local economic and political settings—as forms and patterns of urbanization around the world may be incommensurable. Second, they challenge the idea that representing urban problems in contemporary urban regions, and their planning treatment, can be simplified to the neighborhood scale alone—cities are not just neighborhoods. Third, they point out that the principles of proximity in organizing urban settlements are not new, but deeply rooted in the history of urban planning, both in theory and practice. The ahistorical—and forgetful—dimension of contemporary urbanism, together with its branding rhetoric, emerges as one of its main issues, as well as one of its paradoxes and aporias. After a section reviewing the core of the current debate on the 15-Minute City model, the main body of the article discusses each of the ten objections in detail, grounding them in specific examples. In its final section, the article concludes by embracing a perspective of ‘openness of the city,’ where urban planning is not reduced to simple and quick formulas, but accepts the complex, historical, contextual, intrinsically political, and conflictual nature of ‘making urbanism,’ and its inevitable partiality.

1. Introduction: Ten Objections

One of the most disarming aspects of the uncritical rhetoric surrounding the 15-Minute City is the belief, or assertion, that this is ‘a new idea’ and that it can act as a universal ‘solution’ to the problems of the contemporary city. The beginning of the third millennium has opened up an ambiguous season of “urban planning as slogan” [1] (p. 176), in a communicative drift of town-planning discourse [2] (pp. 88–90), which often indulges in agendas marked by superficial headlines, between clichés, fascination, self-promotional rhetoric, advertising and seductive modes of visual representation to capture consensus. Among these rhetorics, proximity has found paroxysmal development, understandably fueled by the pandemic and post-pandemic mood, having its most effective “fashionable label” [3] in the 15-Minute City.

Proximity criteria are a long-standing classic in urban planning. For example, in 1942, Sert’s Can our cities survive? [4] established them in the section titled “Toward the neighborhood unit”: “If one examines the housing projects constructed during the last twenty years (1920–1940), it will be observed that in some cases there has been recognition of the need of devoting the available land to community uses. In these projects all the necessary community services have been installed. […] A dwelling cell would not be complete without these community services, which extend its functions. Such a project would form a whole or a unit” (pp. 68–70). The following page of the book shows the image of a “borough unit” commented considering various proximity relationships, measured in terms of minutes (5 to 15) for access to different facilities and services.

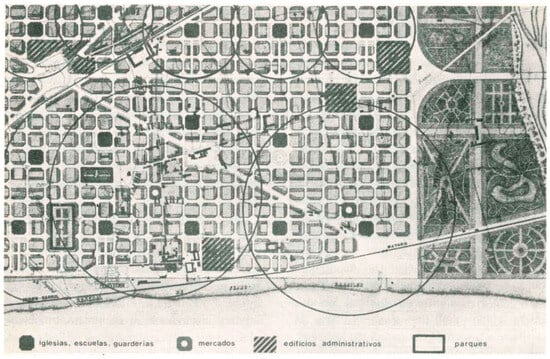

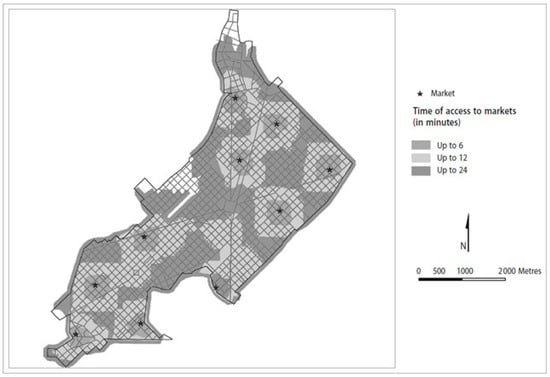

Almost one century earlier, in Ildefonso Cerdà’s plan for Barcelona (see Section 3.1), the choice in favor of a grid layout was made precisely to achieve territorial equality and homogeneous distribution, according to proximity criteria, of the main urban services and facilities so that all inhabitants could benefit from them without disparities [5] (p. 101). “For [Cerdà], urbanism was a tool to diminish the differences in the living conditions of the various social classes, particularly in Old Barcelona. The population’s health and education achieved through service provision throughout the urban network introduced a perception of a modern way of living. Then, his proposal implied regularly distributing basic services throughout the Expansion section” [6] (pp. 128–129). Their location, analytically recreated in a GIS environment representation [6], shows the isochrones in minutes of access to services, according to the three-level hierarchy proposed by this plan (neighborhood level: school, church, barracks; district level: market; sector level: urban park, hospital, administrative services).

Today, Barcelona is very different from how Cerdà imagined it at the time, especially in terms of the degree of building saturation in its blocks—a densification that was not at all envisaged in the initial project. However, it is the versatile urban layout designed by Cerdà in the mid-19th century that today allows for the reinterpretation of its potential in the form of superblocks (superilles). These become distributed ‘cores’ of public space, mainly for pedestrian and local use, through the aggregation of nine modules. This transformation shifts outward, into the street space, the collective-use potential that originally distinguished the interior spaces of the city blocks.

In the decades that followed, this aspect of urban planning, namely the treatment of the local scale of settlements according to performance criteria of proximity, continued to be explored in numerous major urban planning experiences, for instance, those of Ebenezer Howard, Clarence Perry, John Henry Forshaw, and Patrick Abercrombie, to name just a few of the leading figures behind very famous projects (see Section 2.1). But in all these cases, proximity was only one of the aspects that the urban planning project took on and promoted (see Section 3.2), with the strong awareness (second objection) that the city plan could not be resolved within the dimension of the neighborhood alone.

The city is not—only—neighborhoods. And, as far as the city project is concerned (third objection, strictly connected to the previous one), the city is not the paratactic assembly of its neighborhoods [7].

The emergence of ‘sustainability’ in all its forms and dimensions, and the pervasive and ‘metabolic’ nature of its challenge, bring the widespread quality of the urban habitat and its fine grain back to the forefront—and with them the principle of ‘proximity’ to living environments. All this, combined with the demands of social inclusion and citizens’ involvement, has led to the development of a ‘second-level’ architecture of urban plans, concerning their local dimension. A focus on the local has now become commonplace, almost a cliché in contemporary urban planning. A drive to actively involve inhabitants and encourage them to participate in decisions affecting their own living environments is now the norm—an edifying commitment—in every urban planning initiative. This focus often intersects and interacts with the small administrative geography itself. Today, in cities, we are witnessing a strengthening of the role of their subdivision in local sub-municipal ‘districts’ and ‘boroughs’ as entities close to citizens that offer space—including institutional space—for the development of urban policies rooted in the local context. The content of urban planning and its action are thus being redefined in relation to the multiple local environments that can be identified within the urban settlement.

However, this is only one aspect of the challenges that contemporary ‘exploded’ cities pose to urban planning [8,9,10,11,12]. Contemporary urban regions have become ‘cities of cities’ [2,13], which—in their expanded dimension of ‘metropolitan archipelagos’ [14]—strongly ask the project about a possible syntax capable of interpreting the different local environments and urban landscapes which make up the urban as a regional manifestation according to a system of qualifying relationships, an overall hypothesis of urban re-composition and restructuring, and a framework of priorities that tentatively organizes and guides the regeneration action towards a vision—i.e., a narrative construct grounded in space that allows defining a structural-strategic architecture for the planning action (see Section 3.3).

The fourth objection refers to the fact that rethinking the existing city and planning a new one is not the same matter. More precisely, reorganizing an existing urban settlement according to proximity criteria and establishing a new settlement from scratch, adopting these same principles are quite different problems.

Referring to the first of these two very different situations (fifth objection), the issue—afar from a simplifying formula for public communication—inevitably becomes contextual and conditioned by the specificity of the local situation. The 15-Minute City may be reframed as a 10-, 20-, 30-, or x-Minute City, depending on the opportunities of each context, the diversity of initial conditions, and the context-specific interpretation of proximity principles (see Section 3.4). The project often tends to result in a mechanism oriented to rebalance the services provision and environmental performance offered by each neighborhood or local urban piece, and in emphasizing the role of detailed systems for measuring and monitoring parameters and indicators relating to each urban area, which can guide urban planning measures.

Sometimes, certain ‘classics’ of post-World War II city design, such as the idea of the ‘civic center,’ seem to regain relevance [15]. In the second case—urban settlements of new foundation—the echoes of the lesson of Barcelona continue to resound strongly.

Among the latter, the Chinese case of the Xiong’an New Area (see Section 3.5) shows how the city of proximity can also play an ideological and political role, as a manifesto for a new urban/social order. “The ideology of the neighborhood” [16] (p. 84) is something that Italian urban planning critically experienced after World War II (see Section 3.6) through the reconstruction period and the Ina-Casa initiative since the early 1950s. This case also serves as a warning that a simplistic and misunderstood correlation between (spatial) neighborhood and supposed (social) community (this is the sixth objection) can cause neighborhood self-sufficiency aims to generate counteracting effects of exclusion and segregation. The point of the discussion carried out in paragraph 3.6 is to argue that any ‘neighborhood policy’ cannot be presented superficially, detached from the specific settlement, historical, and social context in which it takes shape and form.

However, sometimes (seventh objection) measures for the city of proximity produce paradoxical effects, in the opposite direction to the desired objectives. For instance, it happens that in the redesign of the use of urban space—in particular, open space for public use—even through attractive, catchy forms of tactical urbanism, diverse dynamics may arise that undermine the positive results expected from such interventions, or at least highlight conflicts unforeseen at the time the ‘solution’ was adopted, which was supposed to be unquestionably good and progressive for everyone. This is the topic exemplified and deepened in Section 3.7.

But perhaps the main remark to the city of proximity (this is the eighth objection) criticizes the idea that it is possible today to recreate and pursue a renewed identity relationship between space and society, which until a few years ago was completely confuted in terms of the disjunction that characterizes contemporary urban living. If radicalized, the idea of neighborhood and local community appears slippery, in a historical phase of urban societies that, despite the pandemic contingency, has now internalized the decoupling between space and society in the practices of life of individuals, in the variety of trajectories and in the heterogeneity of the places where practices take shape and form on a daily basis in the urban field. This point is discussed in Section 3.8.

The issue that urges the planning project for cities, therefore appears to be (ninth objection) that of strengthening opportunities for subjects’ multiple belonging to the urban field, rather than that of rooting identity in the place—promoting, on the contrary, the overcoming of physical and symbolic boundaries (see Section 3.9). That is to say (tenth objection), equipping a variable geography of the city that is accessible, available, and open to all its potential inhabitants and practices, working on all dimensions of the urban project, of which the 15-Minute City and proximity represent only one aspect in a more complex framework (see Section 3.10).

Taking a step back, the following Section 2 provides a critical review and discussion of some significant recent contributions concerning the 15-Minute City, and some methodological details and explanation about the features of this contribution and its research design. Then, Section 3, devoted to results and discussion, explores, in ten insights, the issues raised in this first section. They work as a sort of 10-file deepening to show how the city project cannot be reduced to the mosaic of countless proximity bubbles according to a simple salvific recipe. The concluding fourth paragraph closes by contrasting the uncritical use of urban models based on proximity with a wider perspective of openness of the city.

2. Materials and Methods: Literature on the Background and Research Design

Alongside case-driven applications of the 15-Minute City framework [17,18,19,20,21,22] and earlier 20-, 30-, x-Minute policy formulations [23], a substantial strand of scholarship interrogates the model itself. These contributions—often in dialogue with one another—advance critiques, trace genealogies, assess the outcomes of urban plans and policies tested so far, and highlight limits, cautions, and opportunities. This section focuses on that critical strand, synthesizing its recurrent observations into three thematic clusters: (i) genealogy, (ii) social exclusion, and (iii) proximity—three themes that resonate with the ten objections at the center of the paper.

2.1. About the Genealogy

As noted in the first section of this paper, the idea of the 15-Minute City does not emerge out of nothing. A number of authors have reconstructed its genealogy, underlining what Mouratidis [24] calls an ‘overstatement’ of its originality. The long historical trail includes Ebenezer Howard’s Garden City in the UK, Clarence Perry’s neighborhood unit in the US, Walter Christaller’s Central Place Theory, Christopher Alexander’s notion of neighborhoods as units of co-living within the city, Jane Jacobs’s reflections on mixed uses and proximity as keys to local vitality, and Torsten Hägerstrand’s time geography; as well as the conceptualizations and experiments of New Urbanism, Léon Krier’s ‘city within the city,’ and Jan Gehl’s city for people. Despite their differences, these theories and practices share, to varying degrees, an attention to the small scale of the neighborhood, to the mix of uses, to dense spatial and social relations, and to the vitality and livability of places [23,24,25,26].

Turning to the more recent past, Gower & Grodach [23] show that the ‘20-Minute City’ was already present in mid-1990s policy documents from Portland (Oregon) and Shanghai, later spreading over the years by dozens of other administrations in variants such as 15-, 30-Minute, etc. Regardless of the specific time threshold chosen, the emphasis remains on chrono-urbanism [17], whose aim is to bring everyday places and services closer in space—and therefore in time.

The collective genealogical effort is not an end in itself; it also helps avoid repeating past mistakes. In this regard, Khavarian-Garmsir et al. warn against possible drifts toward physical determinism, which the 15-Minute City would share with past planning movements, and which lead to “setting goals without specifying how or by what means they will be achieved” [27] (p. 1). At the same time, genealogy is also useful for identifying what is new about the 15-Minute City. According to Mouratidis [24], the key novelty compared to the past lies in the concept’s capacity to communicate to a broad public beyond the circle of specialists—in short, its branding power. Urban branding is anything but neutral, as Gower & Grodach [23] remind us, noting that it can often produce disparities and exclusions of groups considered ‘not on-brand.’

2.2. On Social Exclusion

The issue of social exclusion is articulated in the literature on the 15-Minute City along at least three lines. First, the difficulty of transforming particularly complex contexts. Working on the application of 15-Minute City on Bogotá, Guzman et al. [26] observe how ‘good intentions’ clash with entrenched segregation, uneven basic infrastructure, and acute socio-economic disparities—a policy based solely on the proximity of services “might fall short” (p. 1) if it is not integrated into a broader strategy.

Second, some seeds of exclusion can be found in the model’s very premises. The ‘15 minutes’ time is calculated for reaching services on foot or by bicycle, yet this assumption does not account for differences among people—ultimately privileging certain mobility capacities and, thus, certain bodies over others. Indeed, Mouratidis notes not only that walking or cycling on flat terrain or uphill is not the same, but also that speeds vary and, above all, that not everyone wants to or can walk or cycle at all. This raises the question of whether walking and cycling, taken as the fundamental modes of the 15-Minute City, are “inclusive enough” [24] (p. 5)—a critical concern for a model that identifies inclusion as one of its core values [20].

Third, several authors express concerns about potential negative consequences of implementing the 15-Minute City model. These scientific concerns are deeply distinct from the conspiracy theory that sparked protests and headlines in several countries between 2023 and 2024 [28,29,30]. Regarding the conspiracy theory, from Canada to Spain and, especially, the UK i.e., [31,32,33,34,35], in the wake of opposition to COVID-19 lockdowns, the popularization of the 15-Minute City was framed in conspiratorial terms—as a technocratic attempt to curtail individual freedom by controlling people’s movements and actions. In one notable case, Oxford City Council removed the term ‘15-Minute City’ from its local plan because it had become “toxic” in local debate [35]. This is the paradoxical flip side of a popular concept. To defuse conspiratorial narratives, several authors [29,30] emphasize work on policy acceptability and on forms of participation and collaboration that do not amount to “mere pretexts to co-opt stakeholders into accepting predetermined policy outcomes” [30] (p. 120). Returning to more reliable critical considerations, for example, if neighborhoods become more autonomous and self-sufficient, residents may have less incentive to move across different areas of the same city, limiting interactions and thus increasing compartmentalization [29,30,36]. On another front, because the 15-Minute City model relies on greater neighborhood digitalization, benefits may favor those equipped with the technologies needed to access digital services, while excluding those who lack the skills or financial means to use such devices [37]. Finally, there is a heavy concern about the induction of social and environmental gentrification: if a neighborhood becomes more mixed-use and livable, then—if not supported by careful public regulation—it becomes fertile ground for rising property values and, consequently, higher housing costs, displacing lower-income residents and preventing the arrival of new ones [29,30,37,38,39].

2.3. About Proximity

Since proximity is at the core of the 15-Minute City model, it is unsurprising that it also sits at the heart of critical scrutiny. If, from a social justice perspective, authors stress that proximity-only policies are not enough [26] to improve urban livability, further reflections focus on proximity per se. Several authors consider that the definition of proximity is rather fuzzy, both in theoretical foundations and in policy documents and evaluation tools.

Conceptually, Guzman et al. [26] stress that proximity does not coincide with distance-time alone; rather, it is a sum of different factors including perceptions, diversity of services, and transport conditions.

In planning and policy terms, in their cross-sectional analysis of policy documents from about thirty 15-, 20-, 30-, x-Minute contexts, Gower and Grodach [23] demonstrate that proximity is often measured inconsistently or not measured at all—thus functioning primarily as a claim and slipping into branding (see Section 2.1). In other cases, policy documents even misunderstand its meaning [40]. This limit is compounded by the weak statutory weight found in some institutional settings, which undermines implementation [23].

In terms of evaluation tools, Knap et al. [41] point to a current lack of methods for measuring proximity. Mouratidis [24] further urges reflections on how close—and to what—it is meaningful to be, recognizing the spatial and economic impossibility of being close to everything, a perspective that risks devolving into a veritable ‘proximity syndrome’ [42].

2.4. A Methodological Note

This critical article is based on a qualitative research design that combines the analysis of contemporary references and sources—i.e., scientific literature, planning documents, and policy reports—with urban planning literature fundamentals, archival sources, historical plans and their commentaries. Both recent and historical materials are mobilized to construct an array of arguments and case studies articulated across time and space, grounding the ten objections announced in Section 1 and discussed in Section 3. The aim of this work is to place the current debate on proximity-based planning methods within a wider and longer trajectory of urban thinking and practice, according to a more accurate problematization and awareness of these issues.

As a preliminary remark to the following section, given that the structure of this article is normative, and that this is not a contribution based on experimental data but rather one of a critical and qualitative nature, the Results and Discussion are necessarily part of a single textual development. The materials and planning experiences discussed in Section 3, referring to theoretical and practical sources in contemporary urban planning and its history, represent the ‘evidence’ to be considered as the results of this article. Their discussion in each individual subparagraph produces the critical findings of the work, as specifically argued, providing arguments in support of the ten objections formulated in the introductory section.

3. Results and Discussion: Beyond Fashionable Recipes

3.1. At the Metric Foundations for Urban Welfare and Proximity Performance

The core concepts under the 15-Minute City label, like proximity, functional variety, spatial compactness, and accessibility, are meaningful but not new in urban planning [43]. Instead, they reflect a long-standing lineage of thought that has influenced city-making practices over time.

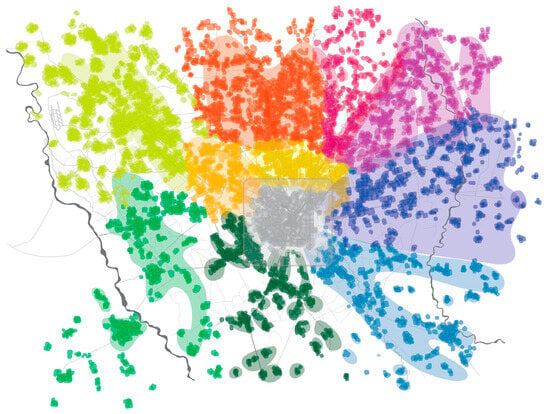

One of the earliest and most iconic examples can be found in Ildefons Cerdà’s mid-19th-century plan for expanding Barcelona [44]. Since Ildefons Cerdà had lived in Barcelona for many years and served as a municipal councilor [45] (p. 176), Barcelona became the practical case study for applying his urban theories, as explained in his foundational work Teoría General de la Urbanización. His major innovation involved the design of streets and blocks, based on two essential dimensions: movement and stasis [46] (p. 26). However, compared to the grid plans of other cities such as New York, Philadelphia, and Buenos Aires, in the case of Barcelona the orthogonal grid came to symbolize a vision of territorial equality [46] (p. 22). To embody the idea of territorial parity and unlimited replicability [42] (p. 9), this spatial arrangement effectively reflects the principles behind Cerdà’s theories, which remain relevant and traceable in today’s concept of the city of proximity (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The distribution of services in the Plan Cerdà. From left to right, the legend reads: (i) churches, schools, barracks; (ii) markets; (iii) administrative buildings; (iv) parks [47].

Cerdà conceived the man of his time as “active, enterprising, daring, ready to sacrifice everything to carry out his business, capable of traveling enormous distances in a short time and transmitting news, instructions, and orders around the world in a matter of seconds” [45] (p. 143). Despite having been written in the mid-19th century, this description remains strikingly pertinent to contemporary conditions—and certainly not only to men. Cerdà proceeded by observing people’s primary needs and going back to the very definition of urban planning as “a set of actions that tend to create a grouping of buildings and regulate their functioning, as well as designating the set of principles, doctrines, and rules that must be applied so that buildings and their grouping, instead of repressing, weakening, and corrupting the physical, moral, and intellectual faculties of the man who lives in society, contribute to promoting his development and increasing both individual and public well-being” [45] (p. 82). The extreme synthesis of his thought, “a group of buildings that promote individual and social well-being through a set of rules and principles,” seeks to facilitate social interactions through an efficient communication system based on a grid layout, a system whose decentralizing effect Cerdà recognized in contrast to radial, center-focused designs. Furthermore, Cerdà knew that the isotropy of the chessboard could not achieve egalitarianism without an equitable distribution of urban services [46] (pp. 22–23). The placement of facilities followed a rigorously defined metric logic, which guided their distribution across the expanding fabric of the city: a group of blocks forms a neighborhood served by a school, a church, and a barracks; four neighborhoods form a district, which corresponds to a market; the higher unit, the sector, consists of 400 blocks and is equipped with two urban parks, a hospital, administrative buildings, and industries. The entire city consists of 1200 blocks and is equipped with two large suburban parks, a slaughterhouse, and a cemetery [48] (p. 129).

Cerdà’s vision not only anticipated but also laid the groundwork for many of the principles that underpin today’s 15-Minute City framework [6]. The 15-Minute City represents a contemporary reinterpretation of long-established ideas about equitable access, functional diversity, and spatial organization. As highlighted by Pallares-Barbera et al. [6] (p. 133) in their study about the efficiency evaluation of Cerdà’s service layout by analyzing his regular spatial pattern (Figure 2), “his proposal changed the way in which people thought about urban space and introduced the idea of changing people’s behavior by modifying public space”. Furthermore, recent studies have shown that Barcelona’s compact urban form and accessibility-focused planning, especially Cerdà’s street layout, promote walkability and neighborhood vitality [49].

Figure 2.

The isochrones for access to markets in the study by Pallares-Barbera et al. [6] on the Plan Cerdà.

As already underscored in Section 1, although more than 150 years passed, Cerda’s plan forms the basis of the Superilles program of today, where the focus is not on individual dwellings, but on the intervias (in clusters of 3 × 3 city blocks removed from traffic), which form urban cells integrated into a larger mosaic of the road network, renewing the topicality of these enduring principles for the sustainability of cities.

3.2. Not Only Community Planning

Rather than functioning as autonomous or exhaustive models, the principles implied by the 15-Minute City formula have historically operated within broader and more complex design frameworks deeply rooted in specific contexts, in time and space. Among the most significant examples, the County of London Plan, 1943 [50], and the following Greater London Plan, 1944 [51] emerged in response to the specific challenges of post-war reconstruction, combining a strict local vision, rooted in the recognition of communities, with a metropolitan one: “Their intention was not just to replace old buildings with new, but to reconsider the social ideology of the County as a microcosm for how the nation might be reimagined” [52] (p. 1).

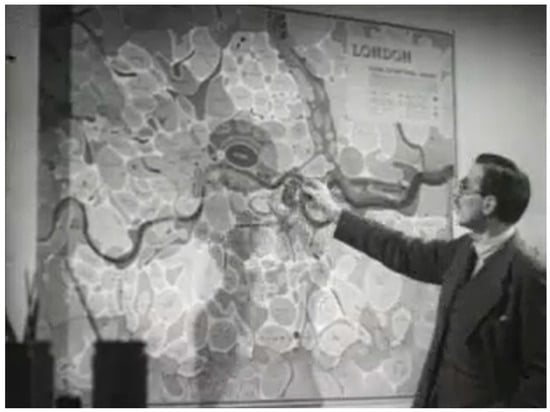

With the County of London Plan, Abercrombie and Forshaw advanced a polycentric strategy, advocating for the development of smaller, self-sufficient urban units, drawing upon the historical model established by Ebenezer Howard’s Garden City movement [53]. “It seems to us that the solution to the problem lies in re-planning these communities: keeping what is good, replacing what is bad,” declared Abercrombie [54]. They acknowledged that envisioning future urban expansion as concentric around a single central nucleus was no longer tenable, as such a model risked replicating the uncontrolled peripheral sprawl characteristic of the pre- and inter-war periods.

The delineation of territorial units into communities ranging from 6000 to 10,000 inhabitants related to the elementary school [50] (p. 9) reflected an acknowledgment of the significance of pre-existing local social structures, regarded as an essential precondition for the formulation and implementation of any meaningful reconstruction strategy [50] (p. 21). “Living together, they can enjoy many advantages. Living in communities is the basis of our plan”, stated Forshaw [54]. In doing so, they reflected on the historical morphology of London, noting that merely two centuries prior, the city comprised a constellation of villages interspersed with open countryside, while the urban core remained relatively compact. However, as the metropolis expanded, these discrete settlements gradually coalesced, ultimately forming the vast and undifferentiated sprawl that characterized London in their time. The fundamental issue they observed was that London had developed without the guidance of a coherent plan; their ambition was to rectify this through the introduction of a comprehensive and forward-looking planning framework. The neighborhood and community scale represented only one of several interrelated spatial dimensions addressed by the plan (Figure 3). In this context, the conceptualization of London as a “traffic machine” placed significant emphasis on reorganizing the entire road network to alleviate congestion, segregate high-speed long-distance traffic from local circulation, and protect local communities from through-traffic; where through-roads already existed, alternative routes were introduced to mitigate their impact [50] (p. 49). Subsequently, under the reorganization of the road system, the plan restructured the functional spatial distribution by transcending the physical constraints imposed by the industrial zones. Following this, considerable attention was devoted to the open space system, assigning quantitative standards proportionate to the resident population. This approach facilitated the integration of individual green areas into a coordinated park system, enabling their conceptualization and management as a cohesive and interconnected whole [50] (p. 38). Moreover, to maximize the collective benefits of the Thames riverbank, the plan advocated extending both the length and number of publicly accessible sections, designating these areas as open spaces or locations for non-industrial development.

Figure 3.

A frame from the film The Proud City. A Plan for London [55] showing the table “London social and functional analysis” of the London County Plan of 1943.

Mort [56] (p. 151) noted that “In Abercrombie’s case competing accounts of the urban future struggled for ascendancy, often within the same planning statement and within his own social personality: monumental civism versus community-minded programs, a grandiose urban aesthetic as opposed to an intense localism, state-driven schemes versus more commercially nuanced expansion.” Abercrombie and Forshaw’s approach balanced local community needs with metropolitan scale challenges, addressing fragmented growth through coordinated spatial and infrastructural strategies.

3.3. Needed Sensemaking Planning Frameworks

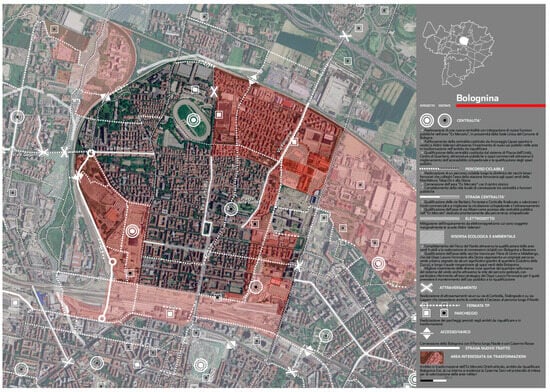

In the Italian context, the 2008 Bologna Structural Plan [57] provides a compelling example on the third objection discussed in Section 1. It is a plan that shows particular attention to the articulation of the city at the neighborhood level, which is reflected in the design mechanism of the so-called “Situations”: 34 spatial aggregations through which to pursue “the objective of improving the local livability of the territory” (Regulatory Framework, Art. 37). “In order to structure local choices, the plan [recognizes] situations, giving them the name with which the inhabitants identify those same parts of Bologna. The situations refer to […] parts of the municipal area which are regarded as ‘cohesive’ from a morphological and/or functional point of view and in terms of their landscape and environment, where a selected series of actions […] is capable of bringing about improvement to general living conditions and of meeting the fundamental standards of urban quality” [58] (pp. 55–56)—in the subsequent 2021 Master Plan of the city, this same tension is reflected in the 24 tables of “Local Strategies for Quality.”

However, the Situations (Figure 4) are only one of the tracks of the planning action of the 2008 Structural Plan, while its fundamental framework resides in seven Figures of Restructuring—the so-called “Seven Cities” shaped by the plan as its main content. “The image of the 7 Cities […] interprets the processes of urbanisation, demonstrating its territorial breadth; it identifies a strategy that is capable of being implemented […]; it proposes perceptible forms by relating the strategy to the physical space. The Cities are the recognition of the existence of new urban forms […], extensive areas of the city with their own existing or potential integrity and quality, where different and varied blends of population, fixed or transient, express their way of living […]. The Cities are territorial forms that seek to emphasise differences which are already present and ‘highlight’ strategies that are developed in different ways in space, in time and in relation to people concerned, […] crossing administrative and territorial divisions and community boundaries. […] [The Structural plan] is therefore a fundamental interpretative framework for a composite series of urban planning works and actions […]. It seeks to consolidate the medium-long term vision through a wide-ranging process of consultation […]. It emphasises the importance of building up a shared image of the territorial area, which is clearly anchored to the spaces to be redeveloped” [58] (pp. 52–54).

Figure 4.

One of the 34 “Situations” from the Regulatory Framework of the Structural Plan of Bologna (2008).

In the Seven Cities of Bologna, echoes of Reyner Banham’s “ecologies” can be recognized—the ‘comprehensible unities’ able to interpret the qualifying relations between space and society, geography and history, and provide a grasping and generative understanding of late 1960s Los Angeles, “that had for many decades defied the attempts of visitors and residents to characterize it in any unified sense” [59] (pp. xvii–xviii). “However, there is something more in the Seven Cities of Bologna […]. They are not only ‘sections’ of current features, but also ‘projections’ of possible and desirable evolutions. This projective dimension is so crucial that the Seven Cities make […] the form of the project” (Infussi in [60], p. 86).

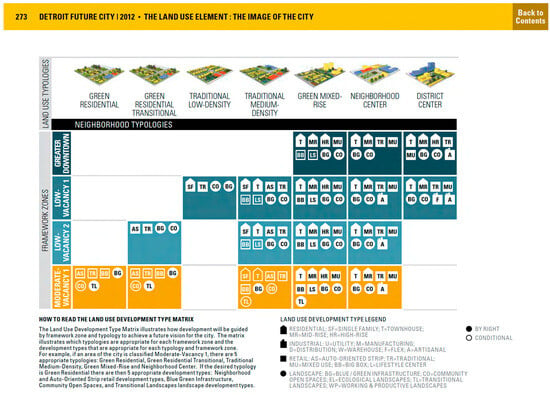

Shaping city’s ‘ecological’ bodies in the manner of Banham is only one way to exemplify the role and need of sensemaking planning tools in framing a vision, moving beyond the view of an indifferent mosaic of urban local entities at the neighborhood level. For instance, the well-known ‘Detroit Future City’ Strategic Framework Plan [61] offers another notable example in this effort. Confronted with the city’s shrinkage, this plan aimed to foster a new vision for Detroit, turning the perception of inevitable and hopeless decline into an opportunity for change toward a different and better future. The plan is made by combining five different lines of action—i.e., “The planning elements”: “The economic growth element” (subtitled “The equitable city”), “The land use element” (The image of the city), “The city systems element” (The sustainable city), “The neighborhood element” (The city of distinct and regionally competitive neighborhoods), and “The land and buildings assets element” (A strategic approach to public assets).

Therefore, this plan also reflects and treats the neighborhood level robustly. Still, it is structured around a vision conveyed in The Land Use Element, which serves as a key to understanding the general logic of urban reframing. The strategic proposal basically hinges on three elaborations: the current land use (Existing: Current land use, p. 267); the scenario of land use in a future perspective of 50 years (Proposed: 50-year land use scenario, p. 268); and the table of Framework zones (p. 234), i.e., the map of abandonment and urban voids, which acts as the real trigger and keystone of the whole urban planning operation. The latter is the medium that activates the mechanism of transition from the current to the scenario condition.

Concerning the maps of the current state and the scenario to 2050, it is interesting to underline the distance that distinguishes the entries in the legend of these two tables—the arid mediocrity of the former, the articulate variety of the latter; a distance that is indicative of the pursued process of liberation from the previous condition that the plan promotes, through a city reshaping process that composes together traditional and new urbanscapes. The mechanism is governed by a matrix (pp. 273–276) which links each “framework zone” to specific “land use typologies” designed to guide the transition (Figure 5). These land use typologies, conceived as demonstrative samples of the desired urban landscape, are themselves composed of variable combinations of elements drawn from an abacus of urban materials, referred to as “land use development types.” A caption in the document makes clear this way of working: “The Land Use Development Type Matrix illustrates how development will be guided by framework zone and typology to achieve a future vision for the city. The matrix illustrates which typologies are appropriate for each framework zone and the development types that are appropriate for each [land use] typology and framework zone” (p. 273). Further, a diagram (at p. 222) synthesizes—visually, once again—the whole mechanism.

Figure 5.

‘Detroit Future City’ Strategic Framework Plan of 2012: the matrix which manages the transition from each “framework zone” to specific “land use typologies” towards the 2050 land use scenario of the city.

3.4. Proximity as a Place-Based Planning Strategy Context Depending

Since the early 2000s, and with renewed emphasis following the COVID-19 pandemic, numerous urban plans have adopted proximity-based criteria, articulated through temporal thresholds of 10, 15, 20, 30, or x minutes, as foundational elements in the design of spatial strategies. Yet, these benchmarks highlight the intrinsically contextual nature of proximity, which resists standardization and exposes the limitations of applying fixed temporal formulas across heterogeneous urban and territorial conditions.

In Portland, proximity principles are outlined in the third strategy of the Portland Plan of 2012 [62], titled Healthy Connected City (p. 73), and are reinforced by the 2035 Comprehensive Plan (2020). At the local scale, the aim was to enhance human and environmental health by developing safe and complete neighborhood centers that ensure residents have equitable access to essential services, such as grocery stores, schools, parks, and public transportation, within a 20-minute walk, thereby fostering active lifestyles and reducing reliance on private vehicles (p. 76). At a broader scale, neighborhoods function as the fundamental nodes within a green urban network, comprising multiple interconnected systems. These include “habitat connections” that link natural areas, “greenways” designed as pedestrian and bicycle-friendly green streets and trails connecting shared neighborhood amenities, and “civic corridors”, major roads and public transit routes that interlink neighborhoods with one another and the city center, while simultaneously accommodating stormwater management and other nature-based solutions [62] (p. 78).

However, the Portland Plan explicitly states that “one size does not fit all” (pp. 4 and 94–95), emphasizing the need for tailored planning responses across the city’s diverse districts. Each district in Portland presents distinct challenges, shaped by its specific topography, natural features, historical period, and how it was developed and integrated into the urban fabric. Some neighborhoods have been part of Portland’s jurisdiction for over 160 years, while others have been annexed or established in the past thirty years. Recognizing this spatial and historical diversity, the plan provides a comprehensive framework of actions, policies, and strategies that reflect and support each community’s unique cultural identities, historical legacies, and environmental contexts.

To implement the Complete Neighborhood (CN) model (Figure 6), the plan uses Geographic Information Systems (GIS) to analyze walkable catchment areas and identify service gaps through the development of a 20-minute neighborhood index. This index includes indicators such as the accessibility index, which assesses access to amenities, goods, and services within walking distance. A neighborhood scoring 70 or above on a 0–100 scale is classified as relatively complete [62] (p. 128). The goal is for 90% of residents to meet all their daily needs, excluding work, within a 20-minute walk or bicycle ride. The index accounts for topographical and geographical factors like rivers, steep gradients, highways, and intersections that could hinder pedestrian mobility. It also considers elements that improve walkability, such as sidewalk quality and presence, signage, route diversity and connectivity, access to frequent, high-quality public transportation, and proximity to key service and activity nodes [25] (p. 10).

Figure 6.

The Complete Neighborhood model in the Plan of Portland of 2012.

This approach embodies a context-specific operationalization of proximity principles, emphasizing adaptive spatial strategies tailored to the unique characteristics and needs of each neighborhood. Rather than applying uniform standards, the city adopts a flexible, place-based approach that responds to the diverse historical, spatial, and social characteristics of its neighborhoods. By integrating tools like GIS and the 20-minute neighborhood index, Portland operationalizes proximity in a way that is both data-driven and locally responsive, offering a valuable opportunity to reflect on how proximity principles must be interpreted and applied concerning specific local contexts.

Similarly, Melbourne’s 20-Minute Neighbourhoods—Creating a more liveable Melbourne policy (Figure 7), embedded in Plan Melbourne 2017–2050 [63], advances the idea of ‘local living’ by promoting access to essential services, community hubs, and public transport within a 20-minute walk or cycle (20-Minute Neighbourhoods, p. 22).

Figure 7.

The 20-Minute Neighbourhood diagram in Plan Melbourne 2017–2050.

The concept of 20-minute neighborhoods is based on providing 17 essential urban and social functions accessible within each neighborhood’s boundaries. At the center of this spatial model is the Neighbourhood Activity Centre (NAC), a structural element that serves as the focal point of the neighborhood. NACs are multifunctional spaces that accommodate a variety of urban activities, including recreation, retail, public services, education, and employment. They are designed to be community hubs that promote social interaction and civic engagement (20-Minute Neighbourhoods, pp. 24–25). While the Plan does not prescribe an explicit spatial dimension for these neighborhoods, it implicitly defines their scale by a 20-minute travel radius, whether by walking, cycling, or using local public transport, from residents’ homes. Accounting for typical walking speeds, pauses at intersections, and non-linear routes, this corresponds to approximately 800 m—half a mile.

However, this approach tried to move beyond a generic advocacy for walkable environments by providing concrete, actionable indicators for implementation.

Further research into the physical delineation of NACs [64] highlighted the need for evidence-based metrics, particularly those related to the built environment, with a focus on indicators such as density and spatial configuration. The findings of Gunn et al. [64] underscore that both built environment characteristics and residential density surrounding NACs play a crucial role in shaping travel behavior, particularly in promoting walking as a mode of transport. High-walkability (HW) NACs are distinguished by significantly higher levels of street connectivity, destination diversity, and residential density, compared to low-walkability (LW) NACs, which exhibit markedly lower values across these indicators (p. 10).

In this case, too, spatial analysis conducted within a GIS framework proved essential for assessing walkability and for revealing spatial patterns associated with the built environment’s features. These evidence-based insights have played a key role in shaping planning policies and urban design guidelines that encourage healthier, more equitable, and sustainable communities. Implementation has predominantly occurred at the neighborhood level, often through pilot projects, as exemplified by cases such as Croydon South, Sunshine West, and Strathmore. These pilot initiatives underscored the importance of bottom-up approaches and co-planning practices as effective means to identify context-specific challenges and to foster the long-term engagement and commitment of local communities in the planning process [25] (p. 16). The goal is not to create uniform conditions everywhere but to develop contextually responsive urban forms that address local needs and spatial opportunities.

Both cases of Portland and Melbourne plans show that proximity, as a planning principle, cannot be reduced to fixed temporal or spatial formulas, but must instead operate as a flexible and context-specific framework.

3.5. Creating Urban Proximity from Scratch, and Its Ambiguities

Retrofitting proximity, diversity, and accessibility into established contexts often demands incremental interventions, strategic densification, and sensitive transformation, rather than wholesale redesign. On the contrary, in planned urban extensions or entirely new towns, these principles can be directed from the beginning, guiding comprehensively the spatial configuration, infrastructure, and land use distribution.

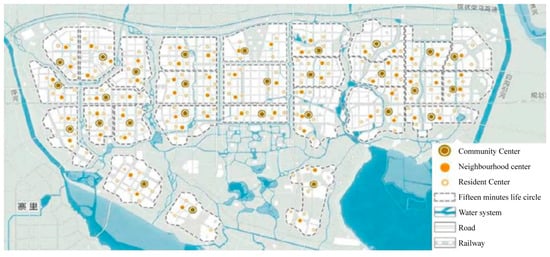

A noteworthy example is provided by the Xiong’an New Area, a state-level new city project located approximately 100 km southwest of Beijing, in Hebei Province (China). At the 19th Party Congress in 2017, President Xi Jinping emphasized relocating Beijing’s non-capital functions through the coordinated development of the Jing-Jin-Ji region, with Xiong’an New Area as a high-standard model city. In response, national and provincial authorities jointly developed the Xiong’an Plan, which culminated in the 2018 Guideline for the Planning of Hebei Xiong’an New Area. The document defines its strategic role, development goals, and implementation timeline, with full completion envisioned by 2035 and international prominence targeted by 2050.

Here, the proximity principles have been incorporated into the foundational planning vision, fully integrating spatial and functional criteria from the outset. The selection of Xiong’an’s location, near one of China’s largest freshwater reservoirs, known as the “Pearl of North China,” was framed as an opportunity to create an ecological and livable city where water and urban elements coexist in harmony. Beyond the rational–scientific planning [65], the site holds historical and symbolic importance, rooted in patriotic stories from the Sino-Japanese War and traditional cultural principles such as feng shui. These layers of meaning were strategically mobilized alongside technical and scientific criteria to legitimize the location choice and reinforce the project’s cultural resonance [66] (p. 5). While the master plan shapes the settlement into three main longitudinal functional strips, at the same time the urban layout is subdivided into 28 cells according to the “15-minute life circle principle” (Figure 8). Each cell is structured as a hierarchical system composed of three levels, corresponding to different scales of service provision and spatial organization. The Base unit is defined by a 5-min walking radius—approximately 300 m—and is primarily residential, accommodating around 400–500 inhabitants; it includes a mix of land uses, with small-scale commercial functions integrated into the layout. The 10-min Compound neighborhood unit extends to a 500-m radius and serves 5000–6000 inhabitants; it incorporates green spaces, such as a park, and a portion of the area’s public service facilities. The 15-minute Livable and Workable community spans a 1000-m radius and is designed for 20,000 to 50,000 inhabitants; it incorporates second-tier facilities and a substantial concentration of employment opportunities, fostering a balanced and self-sufficient urban environment.

Figure 8.

Xiong’an New Area (2018): the cells that subdivide the new urban area according to the ‘15-minute life circle principle’.

This model aligns with the government’s response to the specific dynamics of modernization and urbanization in China. Since the reform and opening-up in 1978, China’s distinctive governance model has evolved in tandem with rapid urban transformation, generating new spatial configurations and administrative challenges as urban residents increasingly engage in mobile and cross-regional behaviors [67]. In this context, the government has sought more effective strategies for urban management, leading to the emergence of the “life circle” concept, an approach influenced by Western theories such as collaborative governance and reinforced by domestic planning practices. As Hou and Liu [67] (p. 10) note, “the basic life circle is the basis of the system. It refers to the basic unit of residents’ daily life. In urban communities, the citizens’ daily life is mostly home-centered and within the scope of a 15-minute walking distance. The main business in such areas is to reshape the public facilities inside the community and mobilize the enthusiasm of residents to participate in building the community life circle.”

Since 2010, the Chinese government has shifted focus from mere expansion to enhancing urban quality through strategies promoting livability, sustainability, and smart infrastructure. Efforts include the development of low-carbon and smart cities, supported by advances in technology and evolving social needs. In the post-pandemic era, priorities such as public health, safety, and digital infrastructure—particularly 5G, AI, and data centers—are central to improving quality of life. These initiatives are expanding beyond major cities to medium and small urban centers, and Xiong’an New Area exemplifies this future-oriented urban vision, integrating ecological, technological, and cultural innovation from its inception.

Xiong’an New Area is envisioned as a strategic urban initiative aimed at relieving Beijing of its non-capital functions, rebalancing the spatial structure of the Jing-Jin-Ji region, piloting new development models for high-density areas, and fostering innovation-driven growth, particularly in science and technology [68]. In fact, beyond the emphasis on proximity principles, the project for Xiong’an New Area also exemplifies a new generation of science and technology-driven urban development in China. Moreover, it is developed as “a test lab for technology innovation and green urbanization, and it has received high-profile political endorsement from President Xi Jinping” [69] (cited in [68], p. 2).

Xiong’an New Area is a model shaped by a rich ideological background, embodying specific socio-political and spatial ambitions that underpin the planning of a new city. Unlike other Chinese cities, which expanded through a more incidental and developer-driven process focusing on rapid economic growth and globalization, Xiong’an is designed as a “template of high-quality development” with a clear political significance under Xi Jinping’s governance [66]. As Stokols pointed out, the 15-minute city principles are not merely technical planning tools but are intricately linked to Xi’s ideological program. They facilitate the transformation of urban spaces into symbols and instruments of broader political, ecological, and social narratives, serving as a material manifestation of the new era of governance that prioritizes high-quality development, ecological sustainability, and social stability. In other words, the Xiong’an masterplan is a kind of manifesto that adopts the 15-minute city principles, structuring neighborhoods into accessible and integrated zones equipped with comprehensive social infrastructure. This approach aligns with its broader ideology enhancing the quality of life and promoting social equity within a planned and sustainable urban environment.

3.6. When (Spatial) Neighborhood and (Social) Community Do Not Coincide

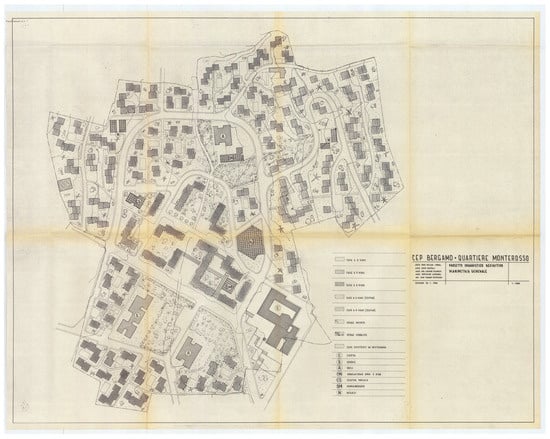

The quartiere (neighborhood) emerged as a particularly significant design concept in Italian urban planning in the decades immediately following World War II. Even at that time, within the specific historical and contextual circumstances of Italy, the concept, alongside its potential progressive qualities, exhibited aporias, limitations, and contradictions.

The Ina-Casa Plan and its two seven-year cycles (1949–1963) were perhaps the most significant experience in architecture and urban planning in the context of social housing policies in Italy—or at least one of them, together with those that developed in the 1960s and 1970s, with the establishment of PEEP, Piani per l’Edilizia Economica e Popolare (Law no. 167/1962) and the Piano decennale for housing of 1978 [70].

“And it was said almost immediately that the concept of quartiere would be the key to urban planning as a whole” [71] (p. 192). “From the very first phase of work, the plan developed a ‘neighborhood policy’ in all medium and large cities, grouping interventions into large residential centers, conceived as organic complexes […]. They were designed as unified urban complexes […] equipped with all the facilities and collective services necessary to ensure their self-sufficiency and functional autonomy” [72] (cited in [71], p. 192, note 6). However, what proved problematic in the quartiere was the assumption that, with its shared facilities and ambitions for autonomous urban unity, it could effectively “foster the gradual formation of bonds of community and solidarity” capable of bringing about “the gradual transformation of family groups into an organic community” [72] (cited in [71], p. 194). Fueled by cultural influences imported from Anglo-Saxon countries, the idea of turning neighborhoods into communities proved to be a false hope that was soon betrayed, as Ludovico Quaroni [73] already stigmatized at the time.

According to Marcello Fabbri, if “the function of these neighborhoods was also to welcome, in an ‘intermediate’ environment, the first wave of migrants heading for the city,” coming from a rural condition, the ideology that animated them was a means for a policy in which “the planning tools imported from European social democratic organicism gave shape to a requirement imposed by Catholic reformism.” “The importation of ‘Neighborhood Unit’ theories […] translated into Italian served to surrogate society with a series of inter-personal and inter-family micro-relationships that were intended to prevent people from seeing beyond the fence [of the quartiere], the world, the classes, and the relations of production” [16] (pp. 87, 84). The quartiere, “in turn, divided into ‘neighborhood units,’” became a distancer, “a filter between the ‘community’ and the city” [74] (p. 259).

In 1957, the so-called quartieri coordinati (coordinated housing districts, CEP) were created, promoted by the Ministry of Public Works through the newly established Comitato di coordinamento dell’Edilizia Popolare (Coordination Committee for Social Housing). The report from the meeting of the Coordination Committee on 25 October 1957 cited in [75] (pp. 31–32), which set out operational guidelines for the various institutional bodies involved in implementing the program, provides a clear summary of the “neighborhood ideology” that took shape in Italy during those years; it is worth quoting verbatim, as follows: “The Social Housing Coordination Committee aims to harmoniously merge, under the guidance of the Ministry of Public Works […] the executive activities of the main public housing construction agencies […] with the aim of creating neighborhoods capable of autonomous life, that is, urban formations capable of satisfying all the material and spiritual needs of their inhabitants and creating environments conducive to the development of harmonious coexistence, under the spirit of our Christian civilization. The idea behind these neighborhoods logically stems from the consideration that the home is a decisive and fundamental element in the spiritual formation and development of the human personality, both within the family and within the community: it is not enough, therefore, for a home to ensure that the family’s basic right to shelter is satisfied; above all, it must offer an environment that, internally, meets all the needs of domestic life and, externally, encourages the free unfolding of social activities. This implies that public housing cannot be reduced to the mere aggregation of buildings into more or less notable complexes, but must, in any case, be rationally organized to facilitate and enhance the essential functions of human coexistence. It is also evident that each of these neighborhoods, while conceived as an autonomous entity, must simultaneously be understood as a vital element of the whole city and the broader territory, forming an inseparable economic and social unit. This, in essence, constitutes the urban and social rationale for the concept of coordinated housing districts (quartieri coordinati)” (Figure 9).

Figure 9.

The ‘Monterosso’ coordinated housing districts (quartiere coordinato) in Bergamo (1960) [75].

3.7. About the Paradoxes of Pretty Urbanism

In the review of cases collected by Carlos Moreno to illustrate good practices inspired by the 15-Minute City model in chapter 12 of his 2024 book [22] there is “Milan: Living in Proximity”. Moreno recognizes the origins of Milan’s focus on proximity in the years immediately around the COVID-19 pandemic: “Milan was one of the cities hit the hardest by the pandemic but is also a remarkable example of resilience and creativity in its response to the crisis. […] Proximity was a central aspect of Milan’s strategy for recovering from pandemic. The city focused on creating living and working spaces that are closer to each other, reducing reliance on long-distance travel and promoting livelier, more dynamic neighborhoods. This approach continues to strengthen social ties, improve residents’ quality of life, and stimulate local economic activity” [22] (p. 152). It seems like a rather encomiastic picture.

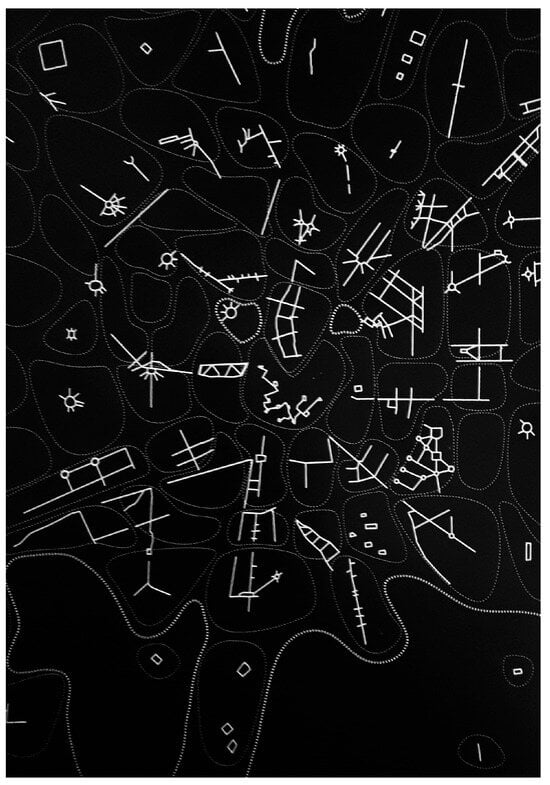

In Milanese urban planning, an approach marked by the narrative of proximity had already been established a decade earlier, characterizing the city’s political message since the 2012 urban plan and then in the subsequent 2019 plan. The image that the municipal administration has focused on is that of “Milan of neighborhoods” (Milano dei quartieri). This slogan is the title of a section of the General Report of the 2019 urban plan, and “One city, 88 neighborhoods to call by name” is one of the claims that shape the vision pursued by it. In particular, the interpretative construct that conveyed this message was the NILs—Local Identity Nuclei (Nuclei di Identità Locale); a cognitive and descriptive matrix of the city, representing it as an aggregation of urban entities at the local scale, potentially endowed with distinct community identities (Figure 10). It is worth noting that the drawings embodying this representation in the plan closely resemble those presented by Forshaw and Abercrombie in their County of London Plan, specifically in the table “London social and functional analysis,” produced seventy years earlier.

Figure 10.

The NILs—Local Identity Nuclei (Nuclei di Identità Locale) and systems of local centralities in a drawing by Nicola Russi for the 2012 Master Plan.

The panel of urban initiatives and policies that led to planning action focusing on proximity and neighborhoods in Milan is quite complex [42] (pp. 13–19), but the first explicit mention of the 15-Minute City is found in the Adaptation Strategy prepared by the Municipality in April 2020, a document responding to the pandemic that was open to proposals and public participation. The following year, the 15-Minute City was a key part of the electoral program of mayoral candidate Giuseppe Sala for his second term. This is the context that includes also the Open Squares program (Piazze Aperte), with the first implementations inaugurated in the fall of 2018, and then relaunched in 2019 in a second edition with a call entitled “Open Squares in every neighborhood.” “Topophilia, chrono-urbanism, and chronotopia—all key ingredients of the 15-Minute City—are present and visible in this program, which is now setting an example for the world,” Moreno emphasizes [22] (p. 157). Further, among the exemplary realizations he mentions the case of the “whale-shaped piazza in front of Tommaso Ciresola school in via Spoleto.”

This case of tactical urbanism is worthy of further examination and brief discussion. The square is located in the NoLo district, within NIL no. 20 (Loreto-Casoretto-NoLo), as defined by the 2019 Urban Plan. NoLo stands for North-Loreto and, emulating the nicknames of famous ‘underground’ neighborhoods (i.e., SoHo in New York), is an invented toponym. This is a place branding idea, dating back to 2013, by three designers to promote a semi-peripheral and popular neighborhood northeast of Milan’s Central Station [76,77]. This district was progressively colonized by small—and then bigger—cultural events and activities, ‘creative class’ happenings, and leisure-time opportunities. It has become a ‘cool’ underground neighborhood of the city—the Fuori Salone (Salone del Mobile) has occupied an abandoned warehouse there since 2018, and Politecnico di Milano has opened one of its OffCampus locations, where to “rethink the notion of urbanity and social living.”

The tactical square mentioned by Moreno has become an iconic symbol of the neighborhood. What was once an anonymous and dangerous intersection has become a welcoming public space where children can exit school, and everyone can enjoy their free time. Parents are pleased that the school entrance and exit now provide a safe area for children. However, people complained about the loss of parking spaces, and kiss & ride opportunities. The tactical square has revitalized an ugly crossroads, making it a pleasant and lively place. But in the evenings and at night, users of the square disturb the peaceful rest of residents. The neighborhood has become attractive, full of trendy initiatives—a cool spot in the city. Nonetheless, the rise of food and drink venues has reduced the variety—what we might call the ‘biodiversity’—of local businesses, making it harder for traditional retail shops, especially proximity stores, to survive: the opposite of what the 15-Minute City aims to achieve. Additionally, real estate prices are climbing—from 2700 euros per square meter in 2017 to 4200 five years later.

Contemporary urban planning needs to overcome the appealing but superficial messages of ‘pretty and cool’ urbanism [78,79] conveyed by trendy communication in a “political use of emotional rhetoric” [80] (p. 20). The city of proximity is not a smooth ride, but a complex challenge full of issues to address—and certainly not an easy ‘solution.’

3.8. Contemporary Urban Practices and People/Space Mismatching

While the concept of Local Identity Nuclei (see Section 3.7) started developing in Milanese urban planning regarding the municipal scale plan, a few years earlier, focusing on the metropolitan area, a study promoted by the Province of Milan titled La Città di Città. Un Progetto strategico per la regione urbana Milanese (The City of Cities. A strategic project for the Milanese urban region, 2006) had taken shape.

In line with other contemporary experiences, the study identified a variety of settlement patterns in the Milanese urban region, leading to its interpretation as a ‘city of cities’ (see Section 1 and Section 3.3) (Figure 11). However, one of the main insights from this and other research on the functioning of large contemporary cities was the ‘expanded’ use of the region by their ‘populations,’ based on multiple diagrams of their spatial practices.

Figure 11.

Milan Urban Region as a ‘City of Cities,’ from the Strategic Project ‘City of Cities’ for Milan Urban Region, Province of Milan, 2006.

While sociologist Guido Martinotti had already effectively stylized the multifaceted nature of urban populations since the end of the last century, distinguishing between residents, commuters, city users, and businessmen [81], the study on the Milan Urban Region further extends the significance of the notion of “city of populations”: “the concept of a city of populations represents one of the underlying components in the process of formulating the Strategic Project of the Province of Milan […]. The term populations is used to refer to the different forms of implicit or explicit, voluntary or necessary, groupings to which the citizens of a community and its inhabitants in general belong, by virtue of the practices in which they are actors each day (practices being that which each individual does and the multiple uses they make of the environment connected with those actions). An inhabitant’s membership of a population group is usually not exclusive; it is momentary and partial. Each individual acts (and can be represented), as the occasion arises at different time of the day or week, according to their activities, as a commuter, motorist or cyclist, professional, art lover, etc. These actions involve a changing and plural relationship with the city and the region. […] The distinguishing feature which multiple urban populations have in common is movement. […] The movement of urban populations contributes to structure the city, consisting not just of places, but also of flows” [82] (pp. 91–92). This passage highlights how metropolitan inhabitants are characterized by belonging to multiple populations and by constant movement, and how these features disrupt the traditional identity-based relationship between space and society in territorial practices.

These characteristics undermine urban planning that is intended to revolve around the notion of the neighborhood, especially when the aim is to recognize a relationship of identity correspondence with a supposed stable community. What emerges in the use of regional space of the urban are rather ‘communities of practices’ [83], understood as structures that are “not intrinsically stable and yet subject to non-random changes”: they are “fluid, open, subject to processes of change in their very identity” [84] (p. 59), set within a general framework of relationships that can be described as a qualifying “disjunction” between space and society in their traditional connections [84] (pp. 23–45).

3.9. Bridging the City, Shortening Distances

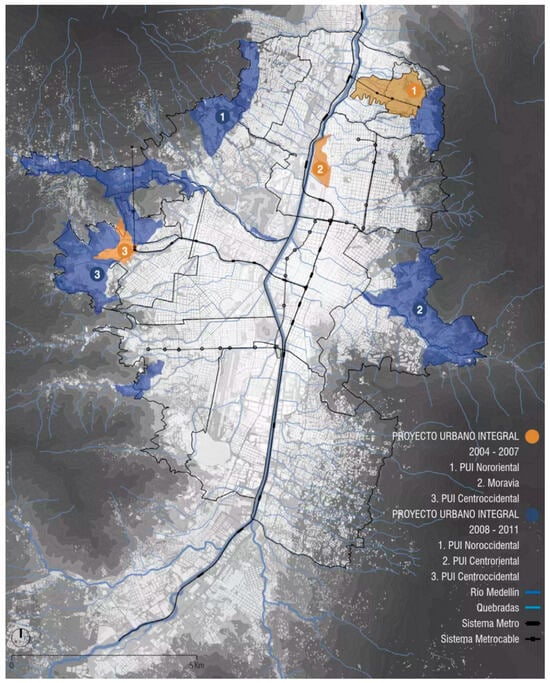

The resilient urban transformation of Medellín, Colombia, over the past three decades is often associated with the principles of the 15-Minute City [22,85]. This experience cannot be reduced to a search for proximity within individual neighborhoods. On the contrary, Medellín’s transformation unfolded across multiple scales, primarily seeking to reduce the physical, cultural, and symbolic distances separating the city’s most peripheral and informal settlements from the rest of the metropolitan area. In a city sprawled through isolated informal settlements and scarred by the violence of drug cartels, the aim was not to make each neighborhood self-sufficient but rather to open marginal areas to urban life while equipping them with infrastructure and services. In this sense, physical interventions—carried out in a highly fragmented topography—were complemented by social, cultural, health, and economic programs targeting the most disadvantaged groups. Medellín thus emerged as an international example of urban innovation and social inclusion, demonstrating that proximity can also be understood as the creation of connections across fragmented territories.

On the one hand, the civil conflict of the 1940s–1960s and the economic crisis of the 1970s–1980s triggered large-scale rural-to-urban migration. Medellín’s population quadrupled, from 350,000 to 1.5 million between 1951 and 1985—and today numbers nearly 2.6 million—with new arrivals settling on the steep mountainsides of the city in informal settlements largely lacking infrastructure and basic services [86]. On the other hand, between the 1970s and the early 1990s Medellín became notorious as the “murder capital of the world” [87], effectively governed by the violence of narcotrafficking and its paramilitary structures. In the early 1990s, the dismantling of the cartel, combined with a broader constitutional and legislative reform process in Colombia [88], created the enabling conditions to envision a different future for the city. Early slum-upgrading programs that legalized land tenure and introduced participatory processes paved the way for Medellín’s first Land Use Plan of 1999 and the elaboration of the Strategic Plan for Medellín and its Metropolitan Area 2015 (1995–1997). For the first time in the history of the city, public institutions, the university, the private sector, and several social organizations collaborated on the Strategic Plan to set out a long-term transformation [89]. Crucially, the Strategic Plan did not treat informality as an anomaly to be eradicated but as a condition to be integrated through targeted and incremental actions.

The operationalization of these principles—later known as ‘social urbanism’ [86,89]—took shape through the Integral Urban Projects (Proyectos Urbanos Integrales), launched in the early 2000s (Figure 12). These projects focused on the most vulnerable informal settlements. The pilot project in the city’s northeastern zone—coordinated by the public agency Empresa de Desarrollo Urbano, like all the other Integral Urban Projects—became emblematic for its actions on transport infrastructure, public spaces, housing improvements, social facilities, and strong resident participation [89]. The Integral Urban Projects thus pursued a dual aim: connecting informal districts with the rest of the city and simultaneously improving their internal conditions.

Figure 12.

Medellín Integral Urban Projects [90].

Connections to the city were made possible by large-scale investments in public mobility infrastructure [91]. The most iconic intervention has been the Metrocable, an aerial cable-car system inaugurated in 2004 and integrated with the existing metro network, which was expanded in parallel, as well as with a citywide Bus Rapid Transit system—a combination then proliferated in Latin American contexts, as La Paz, Bogotá, Curitiba, and many others [92]. Importantly, Metrocable stations were designed not only as transport nodes but also as high-quality public spaces, around which sports facilities, libraries, schools, and cultural centers were clustered. As Porqueddu observes, “The Metrocable can be considered as a significant example of an open-ended design strategy, as it sets the base for an incremental upgrade of the existing informal settlements rather than overlapping comprehensive plans over their territories” [93] (p. 239).

A distinctive feature of the Medellín case was the continuity of urban policies across different administrations [89]. Despite political differences, successive municipal governments since the early 2000s consistently pursued the integration of informality, the reduction of territorial inequalities, and the improvement of urban livability. Unsurprisingly, Medellín has received wide international recognition and is part of the global C40 network.

Yet the city remains fragile. Poverty and inequality persist, and criminal groups continue to exercise partial control in some areas. As Jorge Melguizo, former director of the city’s culture and social development programs, put it: “Medellín is still a laboratory” [87].

In sum, through its incremental and capillary transformations, the Medellín case is meaningful to move beyond a reductive interpretation of the 15-Minute City as a collection of self-sufficient neighborhoods. Here, proximity has been pursued on a broader scale, through the bridging of spaces and communities long disconnected from the rest of the city.

3.10. Making the City Accessible and Open

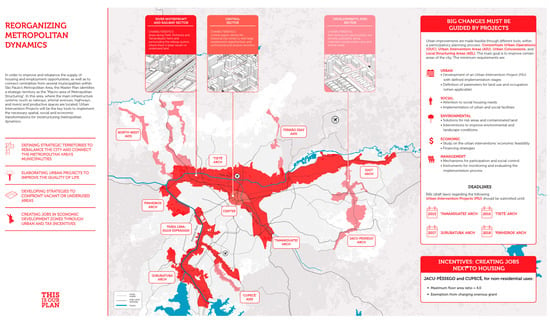

A relevant planning document of the 2010s that works on the idea of openness in the city—beyond the uncertain fate of the operation, following the change in political orientation in the municipal administration—is the Plano Diretor Estratégico do Município de São Paulo (PDE, Strategic Master Plan of the Municipality of São Paulo), Brazil, approved on 31 July 2014, which outlines the city’s prospects to 2030 [94].

The 2014 PDE marks a significant shift in urban policy, representing a societal pact towards social justice, promoting more rational use of environmental resources, improving quality of life, and fostering social participation in decisions about the future [95]. Rooted in the principles of the City Statute (Estatuto da Cidade, Law 10.257/2001), the plan embraces the concept of ‘right to the city’ framing urban space as a collective good and planning as a tool to counter exclusionary development patterns. The central goal of the Plan is to promote a more human-centered and spatially equitable urban structure by addressing persistent socio-territorial disparities. The Plan results from a comprehensive revision of the 2002 framework and exhibits a level of complexity that involved the updated Zoning Law (2015), the Regional Plans (2016), and the Building Code (2016) [94].

Departing from geometrical and abstract spatial layouts, the Plan is structured according to a decentralized and reticular logic, privileging connectivity over hierarchy. “The overall form of urban structure derives from medium- and high-capacity mobility network […]. After having abandoned the preconceived schemes, such as the radiocentric, the polynuclear and the linear, which dominated the urban proposals for São Paulo in the 20th century, the shape of the grid itself […] expresses the potential flows of the distribution of uses in the actual city. […] Far from conventional geometries, a rhizome organizes the 2014 Master Plan”—i.e., the PDE [94] (p. 19). Within this framework, a key strategic orientation is the implementation of transit-oriented development (TOD) and a polycentric urban structure, which aims to concentrate housing, employment, and services along major public transportation corridors.

In doing so, the PDE defines five Perímetros de Incentivo ao Desenvolvimento Econômico (Perimeters for Economic Development Incentives) within predominantly residential zones, strategically located along major roads and public transport corridors, where planning and fiscal incentives are applied to promote non-residential uses such as commerce, services, and public facilities. This spatial strategy, through such injections of functions aimed at local rebalancing, seeks to counter the entrenched dynamics of peripheral expansion and mitigate socio-territorial inequalities [96] (p. 44).

Additionally, in response to the chronic shortage of adequate and well-located housing, the Plan significantly expanded the area designated as Zones of Special Social Interest (ZEIS), doubling their extent to prioritize the production of social housing. Alongside this spatial reconfiguration, the Plan established a dedicated and permanent funding mechanism to support investment in housing of social interest. Furthermore, it introduced the Solidarity Quota (Cota de Solidariedade), a regulatory instrument requiring large-scale real estate developments to dedicate 10 percent of their built area to social housing provision. These combined measures aim to foster a more socially balanced and inclusive urban fabric, mitigating spatial inequality and promoting diversity within the city [95] (pp. 18–19). To promote democratic governance, the Plan institutionalizes participatory mechanisms, such as Planos de Bairro (Neighborhood Plans) and deliberative councils, that enhance civil society’s role in the formulation, implementation, and oversight of urban development policies, fostering informed civic engagement [95] (pp. 66–67).