Abstract

Understanding a community’s place attachment is vital for effective land-use planning and disaster risk management that aligns with local needs and priorities. This study examines the methodologies employed to grasp these values, emphasising the significance of meaningful participatory approaches. It sheds light on the challenges encountered due to COVID-19 restrictions, which prevented direct face-to-face engagement with community members. To address this issue, researchers devised “digital walking tours” as an alternative to traditional walking transect methods, aiming to investigate the relationship between place attachment and perceptions of the landscape in Patreksfjörður, a small fishing community in the Westfjords, during the pandemic. The evaluation of this method demonstrated its suitability for conducting comprehensive and cost-effective community consultations. Participants expressed enjoyment and found the technology (online video calls and StreetView imagery) user-friendly and engaging. To further enhance the method, several recommendations are proposed, including the integration of virtual tours with in-person methods whenever feasible, incorporating additional sensory input, adopting a slower pace, and offering more opportunities for participants to divert to personally significant locations. Other contextual considerations encompass the use of participants’ native language and the facilitation of digital walking tours with pairs or small groups of participants.

1. Introduction

Climate change is expected to cause increased precipitation and greater risks of mudslides and avalanches in Iceland [1], with an identified high risk in this research study’s location of interest, Patreksfjörður [2]. In the context of the increasing uncertainty and risks driven by climate change and weather variability, a small population in a remote area can be more vulnerable to shocks due to being further from assistance in difficult terrain, with limited connectivity and resources [3]. The additional social and economic vulnerabilities in the region make it essential to protect the community’s resources and existing capital (for example, machinery, transportation, and buildings) and continue to improve resilience [4]. Local voices and local knowledge have a vital role in preparation for, and responses to, natural disasters of the kind described above [5]. Place attachment serves as a vital theoretical framework facilitating the exploration and comprehension of a community’s risk assessment [2]. This tool aids in identifying both the vulnerabilities and strengths within a community, elucidating their reactions to interventions aimed at disaster mitigation. Consequently, this study delves into the correlation between place attachment and the perception of environmental threats while also examining the community’s response to adaptation measures implemented in the specific case study location. Notably, these measures involve the installation of substantial avalanche protection barriers near residential areas within the community.

This paper introduces a study conducted within the scope of CliCNord (Climate Change Resilience in the Nordic Countries; see clicnord.org). The focus of the CliCNord project has been on investigating the challenges encountered by small and remote communities in coping with climate change-induced natural hazards. In the selected case study areas, we investigated how the local population understands its own situation, how it handles adverse events and builds capacity, and under what circumstances it needs help from the established system and civil society organisations [2]. The project used a conceptual framework with place attachment as the main theoretical approach and qualitative methods and tools. Place attachment is defined as the affective bonds people have with places, developed in relation to social, physical, or functional aspects [6]. Social dimensions relate to social bonds, including networks and relationships, as well as the caring and trust within these. Physical aspects centre on the relations between physical and environmental characteristics such as infrastructure, the built environment, and nature. Functional aspects relate to the uses or attributes of a place to support individual goals or activities and include natural resources and the local labour markets [2]. Place attachment is also of importance to the concept of place disruption, caused by physical changes to the landscape by both human and non-human actors, for example, damage or evacuation due to natural hazards or interventions to the environment such as avalanche defences [7,8].

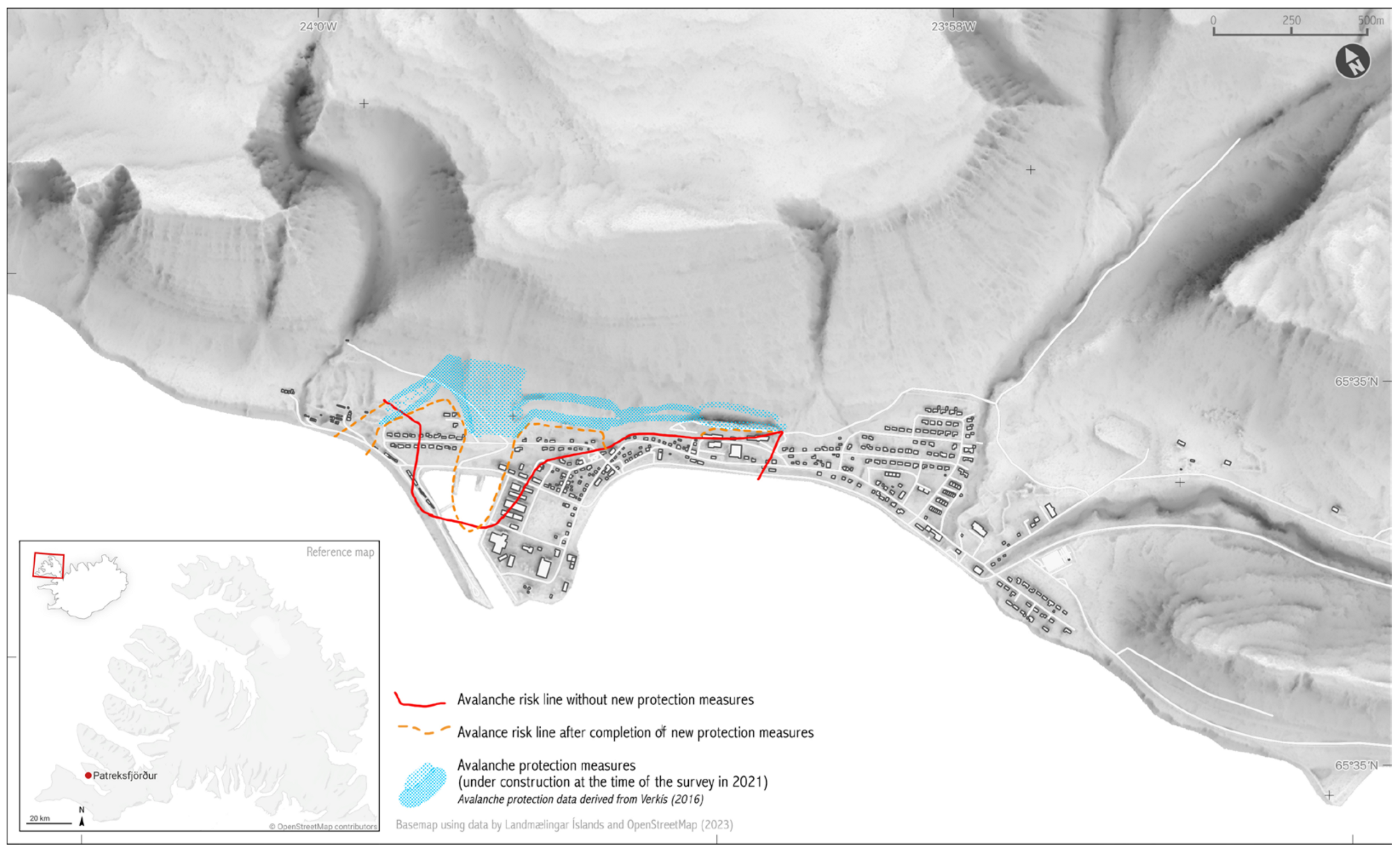

The study for this paper was conducted in Patreksfjörður, a small fishing community with 740 inhabitants [9] in the Westfjords of Iceland (Figure 1). Building on the overall conceptualisation of the CliCNord project, the overall aims of this research were to understand the nature of place attachment in this community and to investigate whether and how individual and collective place attachment is connected to their perceptions of climate change, as well as the associated risks and adaptations to the built environment. While an assessment of all three aspects of place attachments—social, physical, and functional—was envisaged, there was a clear focus on the physical aspects and the built environment. During the past few years, avalanche barriers have been constructed in Patreksfjörður (see Figure 1). It can be expected that the ongoing climate crisis will lead to the construction of more adaptation infrastructure in Iceland, such as avalanche barriers. Hence, it is essential that planning processes and community consultations take place attachment into account to minimise place disruption.

Figure 1.

A map of the research location showing avalanche risk areas and the location of avalanche protection measures.

The main focus of this paper is on sharing methodological insights and experiences of this qualitative study. Involving participation from residents of the town was complicated by the conditions of the COVID-19 pandemic, such as limits on gathering and social distancing. The challenge of conducting a qualitative study during the COVID-19 pandemic created an additional research aim to devise and test “digital walking tours”. This method was based on established walking transect methods conducted using various online communication tools and adapted to create an engaging experience while also gathering the required data. The findings and discussion of this final research aim, of how to go about “remote” qualitative research with the meaningful participation of a community, are the focus of this paper, which is based on Master studies research conducted by the first author (<anonymised ref>). Regarding the theoretical approach and results in terms of place attachment in the case study sites, we refer to other publications of the CliCNord project. One publication outlines the theoretical framework and shows the strong place attachment of the locals to their community [2]. The other CliCNord publication provides information about another methodological approach, namely photo voice [10].

2. Materials and Methods—Exploring Place Attachment during the COVID-19 Pandemic

The study identified qualitative methods as the best way to investigate the research questions relating to place attachment and risk perception in the community of Patreksfjörður. While other studies into place attachment often conduct large-scale surveys using Likert scales or ratings of statements relating to a community’s local environment [11,12], this approach can easily produce misleading or reductive results since they are subject to interpretation by the respondents and simplify the representation of a human experience to a number or simple statement, obscuring the complex networks of social and ecological systems that are involved in the day-to-day life of individuals and communities.

Interviews can be used to draw out more complex narratives and experiences of a place, and those that take place in situ and involve stimuli other than the questions asked by the researcher—i.e., outdoors and moving within the environment—can result in a richer impression of peoples’ experiences of a place [13,14,15]. Transect walks involve walking along a route through an environment of research interest and, in the social sciences, talking with (or interviewing) participants and allowing for direct observation and real-time interaction with the physical space. This method is seldom applied but has been found to be suitable for investigating the human relationship with the environment, including understanding place attachment [16]. A series of transect walks of Patreksfjörður was initially planned for the research study, but the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic made it difficult to arrange in-person qualitative research due to its face-to-face nature. The methodology was developed to take an online format, and the resulting method devised by the researchers was the “digital walking tour” method, which is described in detail in Section 2.

At many points during the pandemic, digital technology became the dominant form of social interaction for many people [17], and the use of digital walking tours allowed community participation in the research despite the restrictions put in place to reduce social contact and the spread of disease. Small, tight-knit communities were particularly vulnerable to COVID-19 due to limited healthcare facilities and the older average age of inhabitants, among other social factors [3]. The recommendations in the literature advising how to carry out online research during the pandemic were applied, for example, by making in-person visits to the study location, remaining flexible, using a simple approach, and learning lessons from the experience for engagement with communities as the pandemic progresses and evolves [17].

The flexibility inherent in online methods for scientific research has been reported as resulting in increased participation and being more inclusive [17]. Several additional benefits relating to this particular online method were also considered. One advantage is that the online method uses virtual interactive panoramas (hereafter referred to by the commonly used term “street view”), which do not change from one day to the next. This means that the weather conditions are controlled, and since the focus of the research—perceptions of the environment and regional environmental changes—could be affected by changing weather, one advantage of the virtual method was that all participants would see the same conditions during their interview, which would be unlikely to occur in the case of repeated in-person walking transect interviews. Using street view also meant that several other variables could be controlled without inconveniencing people. The interview could take place at any time of day and did not incur any costs to the researcher or participant other than the time taken. The starting point and route taken during the interview could be easily replicated without inconveniencing participants who live in different areas, offering another element of control. At the same time, deviation from the planned path is possible, as participants can ask to go along different streets if they want to point out some salient features or a special place.

The online method was also judged to be more inclusive, for example, by including former residents of Patreksfjörður or those temporarily living elsewhere, older participants, those with limited mobility, and people with young children. The online method allows the interview to continue for as long as it takes to cover the route without participants needing access to facilities, struggling with the physical challenge of walking or standing for long periods, enduring cold weather, or requiring childcare. During data collection, a number of events could have hampered face-to-face research. Through November–December 2021, there was a national increase and the highest peak in COVID-19 cases since the beginning of the pandemic, along with the re-introduction of COVID-19 restrictions, including wearing masks and limits on gatherings [18]. There was also an outbreak of COVID-19 in Patreksfjörður, resulting in businesses and schools closing for five days at the time the research was conducted. Nonetheless, the research was not interrupted.

Overall, the virtual option was a more controlled methodology than in-person walking methods, more convenient and inclusive for participants, and very easily replicated. Most importantly, it was resilient to the impacts of the pandemic and enabled qualitative research to be carried out with meaningful community participation.

Recent advancements in digital tools and methods for qualitative research, particularly during the pandemic, have significantly influenced research methodologies. The COVID-19 pandemic necessitated a shift towards remote work and digital engagement, impacting organisational cultures and research practices. For example, a study on the Finnish Defense Forces highlighted how remote work influenced leadership challenges and the development of trust within the organisation, showcasing the broader impacts of digital tools on organisational dynamics [19].

A study conducted in Northern Ghana explored how migration affects culturally embedded and subjective perceptions of habitability, revealing its impact on adaptive capacity and well-being in the face of environmental change [20]. This research highlights the complex relationship between environmental shifts and community resilience, emphasising the need for adaptive strategies that account for cultural contexts.

A study on public psychogeography emphasised the role of emotional and behavioural interactions in urban environments in promoting community climate resilience. By fostering place attachment and encouraging sustainable urban living through the aesthetic appreciation of spontaneous urban plants, this study underscores the importance of integrating emotional and social dimensions into resilience-building efforts [21].

Incorporating digital tools into qualitative research has expanded the scope of participatory methodologies. The use of such tools for community engagement has become particularly relevant in the context of place attachment and community resilience. During the pandemic, home-based hobbies, such as craft-making, served as a means of social survival and agency, offering a unique perspective on how individuals maintained a sense of place and attachment to their communities despite physical isolation [22]. A study focusing on Mediterranean rural areas demonstrated the potential of digital and creative tools to support food cultural heritage, which in turn fosters community engagement and resilience [23].

Additionally, the adaptation strategies of Indigenous reindeer herders and Pomor fishermen in the Russian Arctic, as they face climate change, provide valuable insights into the interplay of social and environmental factors shaping traditional livelihoods. This study highlights how traditional knowledge and practices are being adapted to new environmental realities, illustrating the resilience and adaptability of these communities [24].

Our paper builds upon these recent developments by utilising digital tools to conduct qualitative research on place attachment in the context of environmental change. This approach not only allows for the exploration of new dimensions of place attachment but also contributes to the evolving discourse on community resilience in the face of global crises.

2.1. Digital Walking Tour Methodology

The design of the digital walking tour method involved adapting methods that would be used in commonly accepted qualitative research methods in combination with the use of freely available technology. The design of the digital walking tour method is described in detail below.

2.1.1. Tools and Accessibility

The virtual tour uses three main online tools: Street views via the Icelandic online map Já.is (www.ja.is); the video communication software Zoom for video calls (www.zoom.us); and automatic transcription (inbuilt software in Zoom). The online mapping website Já.is was chosen as it has more street view coverage than other online maps, which do not cover the southern Westfjords in detail. Since there is high-quality street view data on this site for our case study location and almost universal internet usage, this methodology could be applied easily.

For application of this method in other contexts, street view coverage outside population centres and in other parts of the world can be inconsistent. There are several different mapping sites that, at the time of writing, could be used for applying this method in other research locations, including Google Maps (https://www.google.com/maps), Mapillary (https://www.mapillary.com/), and Kartaview (https://kartaview.org/landing). These are open-source and allow users to contribute imagery, which can create a democratic and diverse street view map. Any space could be mapped as a “street” view, including routes on water, as images geo-tagged with coordinates to locate them on the map. Therefore, if the researcher is able to visit the study location at least once, it is possible to upload their own images and create their own route and virtual tour, making open-source map sites a useful tool in contexts where street view data is not available.

2.1.2. Interview Setup and Ethical Considerations

An invitation and pre-interview information were sent through email to ensure that it was easy to locate the paper trail for each participant, and Zoom calls were scheduled at the convenience of participants. Interviews took place between 27 October 2024 and 12 November 2021. Automatic transcription was set up in the Zoom account settings.

At the start of each call, verbal consent was obtained from participants for recording and automatic transcription prior to beginning the walking tour. Screensharing the street view in full screen gave a bigger image on the participant’s computer, and closed captions created by the automatic transcription were not visible to participants during the interview so as not to distract participants from the more important visual input of the street view images. At the end of every interview, the recording and a text file of the transcription were automatically downloaded by Zoom into a dated text file. Some corrections to errors in the transcription were necessary, especially for Icelandic words and place names, but automatic transcription was overall helpful and saved time. The technical side of the virtual tour was tested with a non-resident volunteer who was able to give feedback about the use of street view and Zoom and test the automatic transcription.

Ethical approval was obtained for the study in August 2021, and the research follows the ethical guidelines of the University Centre of the Westfjords [Suðurgata 12, 400 Ísafjörður, Iceland]. Verbal consent was obtained for the recording of the interviews, and participants were informed that the video recordings and transcriptions would be deleted after the data analysis was complete. Participants were informed of their right to withdraw from the study at any time, and contributions were anonymised.

2.1.3. Design and Sample

The route taken in the digital walking tours was based on a preliminary walk around Patreksfjörður. The route took in places that had been highlighted as important during the preliminary walk with a resident of the town, but participants were encouraged throughout the walk to choose significant places that were not covered by the route chosen by the interviewer and to change or rotate the view at any point.

A narrative accompanied the online walk, based on a typical semi-structured interview. The narrative provided a structure that could be replicated in every interview while allowing participants to elaborate. The aim was to elicit participants’ perceptions of the place where they live, so open questions were asked that allowed participants to make personal reflections on their experience of the places they visited. The narrative was designed to create an engaging experience for the participants, beginning by asking them to imagine arriving on the edge of town after a long journey away from Patreksfjörður. The intention was to bring the participant into the street view environment, provoke some suspension of disbelief, and prompt thoughts, memories, attitudes, and behaviours related to different parts of the town. These were all of interest in relation to the research questions relating to place attachment and perceptions of regional change. To start with a neutral topic to ease into the interview and avoid introducing bias, the first question was, “What three words come to mind when you arrive in Patreksfjörður?” In addition, at the end of the walking tour, participants were asked directly whether anything would cause them to leave the community. Ex-residents were asked why they left and whether they would consider moving back into the community.

Eleven participants took part in the digital walking tours; they were recruited through existing contacts within the community, snowball sampling, and public appeals for participants, including the distribution of posters via local social media groups. A total of nine interviews took place: seven interviews with individuals and two interviews with couples. Interviews lasted between 40 and 94 min, with an average interview length of 52 min. The age range was roughly 20–70 years, and there was a ratio of eight women to three men. There were seven residents and four ex-residents, eight Icelandic and three non-Icelandic.

2.1.4. Limitations

Qualitative research cannot provide a truly objective representation of a community [25], but it can provide a deep insight into the real lived experience of the participants and a richer understanding of the research topic than can be gained through broad quantitative methods, and this is acknowledged as an inherent advantage of this kind of study. In addition to general limitations often associated with qualitative research (such as the language used and the representativeness of the sample), some limitations were recognised that were specific to the method used: accessibility and the age of the street view photographs. The opportunity to test a new method was viewed as having greater potential to contribute to future research than relying on methods that are known to be effective, and these limitations were considered to be outweighed by the advantages of trialling the online method. These limitations and how they were mitigated and justified are discussed below.

The question of whether the method is accessible due to the need for digital literacy or internet access is an important criticism of all online research designs [17]. Overall, there is good internet connectivity in Iceland, and although digital literacy should be considered seriously in any online research design, in this research context, it was considered not to be a barrier to participation. In terms of physical accessibility, this method allows participants with limited mobility to take part, removing the potential barriers associated with walking, such as distance, challenging terrain, or bad weather.

Photographs in the available street view date from 2013 and 2017, before the avalanche barrier construction began (Figure 2), and this was considered a potential drawback to the method. Since the research topic involved the participants’ responses to the changes made to the built and natural environment, it was also considered that it could add an interesting slant to the research. Participants would be able to compare their mental image of the present-day reality in Patreksfjörður with the image of the past presented to them in the street view, potentially providing a prompt for any latent or salient opinions or other perceptions.

Figure 2.

Contrast between street view imagery (2017) and a view of the same street at the time the research was conducted (2021). Sources: (Left) www.ja.is; (Right) photograph by the author.

In Patreksfjörður, the availability of ‘street view’ imagery is limited primarily to areas accessible by car. Walk-only precincts or pedestrian paths are often not covered by street view-capturing devices, which poses a limitation for digital walking tours. This is less critical in this case study due to the small and compact size of the town, but it can be a limitation of this method in many small rural communities.

Recording the route was considered to present a view of the streets and surroundings as they look in the present day. This would not have allowed deviation from the route, however, which is possible when using street view. It was decided that this was an important strength of the method, as it allows some flexibility and better reflects a real transect walk, and so this option was rejected for the study.

2.1.5. Researcher Bias and Reflexive Practice

The researcher’s “outsider” perspective is likely to have some influence on the data collected. It should, therefore, be acknowledged that the interpretation of the data captures a different understanding than would be derived by a local, but as the Icelandic proverb says, “Glöggt er gests augað” (“Clear is the guest’s eye”)—an outsider may observe details that would not be perceived by a community insider. Following the reflexive approach recommended by other research into place attachment [26], a summary of findings was sent to participants in January 2022. Participants were asked whether they were satisfied with the interpretation of the data overall and were given the opportunity to provide additional feedback, which was considered in the final presentation of the findings.

3. Results: Assessment of the Digital Walking Tour Method

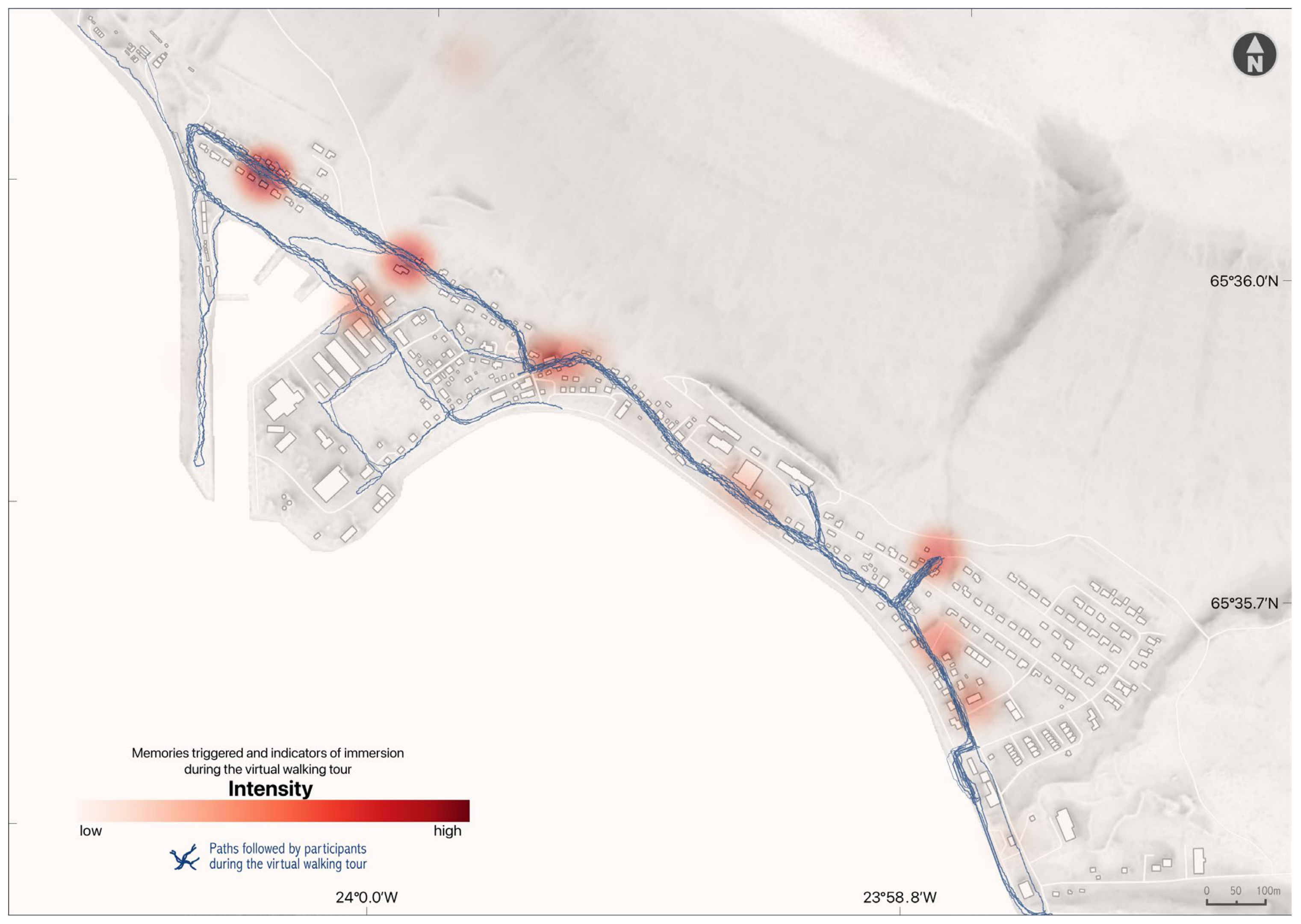

Evaluation of the method was conducted in two ways: first, by analysing indicators of a participant’s level of involvement in the interviews, and second, through a participant survey after the interviews had been completed. During the interviews, comments or reactions that indicated that participants were emotionally connected with the experience were noted, coded by topic, and geo-coded. Indicators of emotional connection included when participants recalled memories that were triggered by visual cues, comments on the environmental conditions or other observations of the imagery during the walk, disagreement about where the route was going or redirection of the route, and so on. The data were then applied to a basemap of the town so that it was possible, for example, to show which locations were associated with indicators of engagement with the digital walk or which locations were associated with different topics.

Participants were also asked directly about the experience at the end of the interview, but responses to this question tended to be generally positive and non-specific. In order to add to the analysis of the method, a post-interview questionnaire was sent to all participants. This was used to verify whether the data about the method taken from the interviews was interpreted correctly, to check assumptions (such as the ease of use of technology and preferred language), gain better insights into the experience of the participant, and understand how it could have been improved. The questionnaire was anonymous to encourage honest feedback, and it was translated into Icelandic to allow participants to say anything for which they might not have found the words in English during the interviews. It was sent to all eleven participants one month after the interviews were completed and received ten responses. Best practices for future use of digital walking tours in other research or community consultation work were drawn out of the responses.

3.1. Interview Data: Engagement with the Digital Walk

A total of 71 segments were coded as showing participant engagement in the street view experience. These fell into three categories: triggered memories, noticing environmental conditions, and giving directions. Participants recalled personal memories about different locations. These were sometimes related to the research topic but were often about social occasions they remembered that were associated with particular buildings or streets, for example. In total, 48 segments were coded as memories. Participants referred to many small but significant events and light-hearted memories that often evoked a sense of nostalgia, such as: “The shop over there […] that is the first place that I actually tasted machine ice cream for the first time. So I have a lot of good memories there”.

Participants noticed the weather or other environmental conditions in the street view imagery, making observations like: “It’s really low tide as well, we can see on the boat”. At times, they made comments that related to the subject they were already talking about or helped to explain the content or location of what they were saying (“Behind where they are drying their laundry up there”), but often comments were made as asides or distractions, interrupting themselves to say, for example, “Oh, that’s my car”.

Participants were encouraged to divert the route when they wanted, and some gave more directions than others. Participants gave directions since they did not have control of moving through the street view, so this was captured in the transcription, as in the following instructions: “Also the harbour is always full of life—oh here we can turn right […] Yes, and then before the red house we can turn left”. Variation in the route was documented (Figure 3), with some diversions within both the local and the wider area. Feedback on this aspect also came from the post-interview survey.

Figure 3.

Indicators of engagement with the digital walking tour, and routes taken by participants.

The coding system made it possible to show a thematic map of the locations where any coded segments occurred. It was found that the majority of coded segments relating to indicators of engagement and involvement in the virtual tour were concentrated along the walking tour route (Figure 3). These indicators are marked on the heatmap in red according to reference points, and most of these are located along the walking route rather than further afield, possibly showing that visual cues triggered the participant’s engagement in the interview.

3.2. Post-Interview Survey

Ten out of eleven participants completed the post-interview survey (six residents and four non-residents). Seven completed the survey in Icelandic and three in English. One participant reported their age as 19–30, four were aged 30–49, and five were aged 50–70. Regarding the ease of technology use during the interviews, participants were asked to rate it on a five-point Likert scale. Nine out of ten participants rated it as 5 (very easy), while one participant rated it as 4. When asked about the most enjoyable aspect of the digital walk, participants mentioned the novelty of the experience, how it evoked memories, and how it stimulated new perspectives and thoughts about the area. Overall, participants expressed that the virtual tour provided a fresh outlook on familiar surroundings, stating, “[A] new experience seeing very familiar surroundings from a different perspective. Definitely different memories come back when doing a virtual tour rather than the real walk”.

When asked about their preference for an in-person walk or a digital walk, participants were divided. When considering the participants’ place of residence, one non-resident and two residents preferred a real walk, while three non-residents and four residents favoured the digital walk. Participants provided a mix of reasons for their preferences, including practical considerations and enjoyment of the novelty of the method. For instance, one participant remarked, “It is different to see the town in pictures and it gives possibilities and space to interpret feelings and opinions without influence from the town”. Responses also highlighted participants’ recognition of the method’s usefulness for conducting research, with comments such as, “I like walking and walking around the town a lot, but this technique is very nice and is very suitable for projects like this”.

Participants who preferred a real walk emphasised the physicality and absorption in nature that can only be experienced in person. One participant mentioned, “I would like to go on a real walk with you and take time to chat and also stop for a coffee, on a real walk we could stop at small details and zoom into them, have a closer look”. Other participants pointed out the health benefits of outdoor walks, particularly in the context of the pandemic, stating, “It is healthier to go on a real walk, and because people are spending so much time at home now, I think we should use every opportunity to get out of the house”. Additionally, some participants felt that their views and experiences could be better conveyed by being physically present in the environment, as one participant explained, “The story becomes clearer when I’m there”.

When asked about feeling the sense of taking a “real walk” during the virtual tour, participants rated their experience on a Likert scale from 1 to 5, with 1 indicating “not at all” and 5 indicating “it felt very real”. The average response was 3.9, lower than other ratings. Participants also provided suggestions for enhancing the sense of reality, such as incorporating sounds of the town and walking along different routes. Other suggestions included participating as a group, discussing additional topics, speaking Icelandic during the walk, and walking in silence. Participants offered their own ideas for improving the walk, such as utilising Virtual Reality technology, introducing scents of the environment, and moving at a slower pace.

Participants’ opinions varied regarding the length of time taken for the interview. Half of the respondents considered it an appropriate duration, four participants desired a little more time, and one participant preferred significantly more time. Some participants expressed that the route and interview topics felt limiting, indicating a desire to explore other locations. One participant expressed: “I would have chosen a bit [of an] other path than we followed. I could feel how I was directed to places the guide wanted me to [say] something about. I had been looking forward to go[ing] to other places. And when we were in the neighbourhood, I [felt there] was not enough time left to go there”. Participants were asked if there were any additional locations they would have liked to visit during the virtual tour. Three participants responded “no”, while two did not provide a response. The remaining five responses offered a range of locations within and around the town, some of which were not feasible to explore using street view. Finally, participants were asked to rate their level of engagement during the interview by indicating whether they felt inspired to discuss the town and its surroundings and share their memories. The average response on a five-point scale was 4.4, indicating a high level of inspiration.

4. Discussion

Combining the findings from the survey and observations of participants’ level of engagement and involvement in the digital walking tours allows some lessons and improvements to be drawn from this pilot study for future research.

Comments about the conditions in the street view suggested that some participants became deeply involved in the experience. The statements categorised as indicators of engagement often were not qualified as being virtual by saying, for example, “in the picture”; they were simple statements of fact (e.g., “It’s low tide”; “Oh, that’s my car”). This suggests that the data collected comes from a participant who is fully involved and comfortable with the experience. Instructions given by participants to divert the route or change the view were coded as relevant to the level of engagement. There were mixed results between participants; some participants gave many directions, and some gave none. The spatial information related to these results supports the idea that what the participants saw in the street view images were the dominant stimuli for the data that was gathered, as the memories and engagement indicators appear to closely follow the main route that was taken. This demonstrates the importance of the visual stimulus for eliciting insights into the life of a community, as the method provoked thoughts and memories that are assumed to be connected to what they saw.

The density of engagement indicators within the town might also suggest that in the wider environment, people have less densely located “special places”. It would be interesting to see the contrast with elicited memories from an in-person walk in this respect. Overall, the ability to present the data resulting from this research in thematic maps supports that the methods used (digital walking tours with coding analysis and mapping) can draw out place-based information, which could be useful in contexts such as land-use planning [27].

The general outcome of the post-interview survey was positive. One participant did not respond to the survey, and it is possible that the non-response could indicate a negative experience; if this was the case, their feedback could have been the most useful for making improvements. A positive response from 10 out of 11 participants is encouraging in terms of the suitability of this method for future research. Responses from participants indicated that the most enjoyable aspects of the walk were that they were able to re-visit places, that pleasant memories were triggered, and that it was a novel experience. Participants also stated that the interview made them consider new or different perspectives, suggesting that this method could be used as a way of exploring subjects that people do not usually talk about in their day-to-day lives or to trigger discussion of subjects that are otherwise latent. Every participant responded that the technology was easy or very easy to use, and there were no technical issues during the research. All participants stated that the interview was the right length or that they would have preferred to talk for longer. The average length of the interview was 52 min, which suggests that an hour is an acceptable amount of time to schedule for the digital walking tour.

Feedback from participants indicated that they had a good insight into the motivation behind the digital walk for research purposes, and they could see the value in using this method in order to save time and avoid distractions or bias. Some responses indicated that participants would have enjoyed both a virtual and a real walk, but this survey question forced them to choose one option, reflecting some ambivalence. In-person methods such as transect walks, in combination with digital walks, could provide deeper insights and break down barriers inherent in the computer screen, which could help form a good rapport with participants.

The lower mean response of 3.9 out of 5 to the question relating to how “real” the walk felt indicates that the digital walk could have been richer on a sensory level. The most popular suggestion for improving the sensory experience of the digital walk was to hear an environmental soundscape, which could be done using field recordings in the research location that could be played at key points during the interview. Three responses indicated a feeling of being rushed, and these participants’ feedback suggested they did not feel they could opt to go to other areas in the town. One recommendation resulting from this finding is not to rush the route or the interview. Variations in this regard, as well as how involved participants were in the process, could be an indicator of how comfortable different participants were in the interview setting. This could be due to individual differences or a reflection of how well the researcher was conducting the interviews. It could, for example, reflect the level of confidence or comfort on the part of the researcher, which improved with familiarity with the methodology.

Participants should be encouraged to divert the route to places that are meaningful to them. On the other hand, while it is worth consulting with participants about the route taken, it is likely that due to issues of control, resource limitations and individual preferences, there will always be some shortcomings affecting either the replicability of the method or the satisfaction of the participants.

Other Considerations

Some participants expressed that they would have preferred to conduct the digital walking tour in Icelandic, and carrying out the interviews in the participant’s first language would be preferable in order to get closer to their lived experiences. Some participants spoke other languages as their mother tongue in this study, and integrating this into the method would be dependent on the budget and resources of different researchers. In two of the interviews, the participants took part in pairs. From the researcher’s point of view, it could be of benefit to find more participants who are willing to take part as a small group because a pair or group may begin to discuss issues or memories amongst themselves, agreeing with or contradicting each other, which allows the researcher to step back from controlling the narrative and gain different insights. This occurred in the two paired interviews of this study and is an established benefit of focus group interviews [25].

5. Conclusions

The findings and discussion of this study suggest that digital walking tours can offer an inclusive and cost-effective means of investigating values, perceptions, and knowledge held by communities relating to urban and rural landscapes and regional environmental change. This method was well-suited to this research topic and was especially useful during the COVID-19 pandemic, where the use of “remote” methods enabled the research to be carried out with meaningful community participation. While digital walks lack the full sensory immersion and spontaneity of physical transects, they offer unique advantages, such as the ability to engage participants regardless of their physical location, control over environmental variables like weather conditions, and greater inclusivity for those with mobility limitations. The recollection of personal memories during the digital walks supports the results from the post-interview survey, suggesting that the method can elicit the perspectives that were of interest. The place-based memories triggered by the visual stimulus of the street view were important to the investigation of place attachment as they illustrate the affective and cognitive elements of the place attachment framework and provide rich place-based data about community values relating to specific locations. For future research, it can be noted that the method could be improved by combining virtual tours with in-person research methods such as transect walks, allowing the virtual tour to take a relaxed pace, and reminding and encouraging participants to make diversions to meaningful locations. In addition, the addition of a soundscape or audio soundtrack relevant to the research location could add to the sensory experience. The results may also be improved by using the first language of participants and conducting virtual tours with small groups or pairs of participants.

This method has several advantages that make it well-suited to qualitative, place-based research, especially as a way of carrying out participatory qualitative research during a pandemic. This demonstrates that, while not immersive in the virtual reality sense, digital walks can still facilitate deep engagement with the environment in a way that is both methodologically sound and contextually relevant. It is suggested as an effective method for gaining a rich understanding of a community’s place attachment and valued places, which could be used by planners to improve the design of adaptations aimed at protecting communities. It can also augment the consultation process and reduce associated costs. As the method requires minimal resources, it is a cost-effective method for improving approaches to participatory emergency, community development, land use and other spatial planning, or any other sector in which community values are at stake or where stakeholders and/or rights-holders should be involved in planning processes.

The findings of this research offer valuable insights into the tools and approaches that can facilitate a more comprehensive understanding of perceptions of local landscapes, as well as the values and importance associated with them. Specifically, the utilisation of digital walking tours has demonstrated its effectiveness in understanding various forms of place attachment and their meaning. Moreover, this study has presented important lessons for the application of digital walking tours in future research endeavours. The outcomes of this research indicate that digital walking tours can serve as a viable method for conducting survey mapping of landscape values, enabling the extraction of the meaning of places, value systems, perceptions of vulnerabilities and other indicators of place attachment. These outcomes can be used to provide substantial place-based data for informed decision-making in planning contexts. The tools and methods used in this study require limited resources, thereby presenting a cost-effective means of gaining profound insights into the priorities of communities and their inhabitants. By engaging with the complexity and quality of meaning that the landscape and local environment hold for local populations, planners and developers can improve risk communication, as advocated by Emmel et al. [14]. By incorporating approaches such as the one introduced here, climate change mitigation or other hazard reduction infrastructure developments are better aligned with the comprehensive requirements, concerns, and aspirations of entire communities, including individuals who may not be directly influenced by such transformative processes.

Author Contributions

M.K. acquired the funding for the overarching CliCNord project. M.K. was in charge of conceptualising place attachment and the selection of case study sites. The research questions and analysis plan were agreed upon by all authors. F.S. undertook all analyses with additional input from B.D.H. B.D.H. created the maps. F.S., B.D.H. and M.K. drafted the manuscript. All authors provided substantial critical input to improve the manuscript, and all authors approved the final draft. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The research in this paper is a part of the Climate Change Resilience in Small Communities in the Nordic Countries (CliCNord) research project that has received funding from the NordForsk Nordic Societal Security Programme under Grant Agreement No. 97229.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article cannot be made available by the authors due to ethical considerations. Anonymity is assured to the participants of the study, and given the small size of the village, sharing the interview transcripts would allow conclusions to be drawn about individuals.

Acknowledgments

We would like to extend gratitude to all the individuals who took part in the research. We would like to express our gratitude to the reviewers for their valuable comments and suggestions. Their insightful feedback has significantly contributed to the improvement of this manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Bannan, D.; Ólafsdóttir, R.; David Hennig, B. Local Perspectives on Climate Change, Its Impact and Adaptation: A Case Study from the Westfjords Region of Iceland. Climate 2022, 10, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kokorsch, M.; Gísladóttir, J. “You Talk of Threat, but We Think of Comfort”: The Role of Place Attachment in Small Remote Communities in Iceland That Experience Avalanche Threat. Reg. Environ. Chang. 2023, 23, 150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. Policy Implications of Coronavirus Crisis for Rural Development. Available online: https://read.oecd-ilibrary.org/view/?ref=134_134479-8kq0i6epcq&title=Policy-Implications-of-Coronavirus-Crisis-for-Rural-Development (accessed on 13 July 2024).

- Amundsen, H. Illusions of Resilience? An Analysis of Community Responses to Change in Northern Norway. Ecol. Soc. 2012, 17, art46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bird, D.K.; Gísladóttir, G.; Dominey-Howes, D. Different Communities, Different Perspectives: Issues Affecting Residents’ Response to a Volcanic Eruption in Southern Iceland. Bull. Volcanol. 2011, 73, 1209–1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewicka, M. Place Attachment, Place Identity, and Place Memory: Restoring the Forgotten City Past. J. Environ. Psychol. 2008, 28, 209–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihaylov, N.L.; Perkins, D.D.; Stedman, R.C. Community Responses to Environmental Threat: Place Cognition, Attachment, and Social Action. In Place Attachment; Manzo, L., Devine-Wright, P., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2020; pp. 160–176. ISBN 9780429274442. [Google Scholar]

- Devine-Wright, P.; Howes, Y. Disruption to Place Attachment and the Protection of Restorative Environments: A Wind Energy Case Study. J. Environ. Psychol. 2010, 30, 271–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statistics Iceland Population by Localities, Sex and Age. Available online: https://px.hagstofa.is/pxen/pxweb/en/Ibuar/Ibuar__mannfjoldi__2_byggdir__Byggdakjarnar/MAN030102.px/table/tableViewLayout2/ (accessed on 13 July 2024).

- Lyons, A. “These Pictures Are Me”: Using Photovoice to Investigate the Impact of Place Attachment on Community Resilience. Master’s Thesis, University Center of Vestfjörður, Ísafjörður, Iceland, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Ariccio, S.; Petruccelli, I.; Ganucci Cancellieri, U.; Quintana, C.; Villagra, P.; Bonaiuto, M. Loving, Leaving, Living: Evacuation Site Place Attachment Predicts Natural Hazard Coping Behavior. J. Environ. Psychol. 2020, 70, 101431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, T. Planning for Place: Place Attachment and the Founding of Rural Community Land Trusts. J. Rural. Stud. 2021, 83, 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingold, T.; Lee, J. Ways of Walking: Ethnography and Practice on Foot; Ashgate: London, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Emmel, N.; Clark, A. The Methods Used in Connected Lives: Investigating Networks, Neighbourhoods and Communities; National Centre for Research Methods: Southampton, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson, J.S.; McClelland, A.G. Walking Methodologies. In International Encyclopedia of Human Geography; Elsevier: Oxford, UK, 2020; pp. 207–211. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, J.; Jones, P. The Walking Interview: Methodology, Mobility and Place. Appl. Geo. 2011, 31, 849–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Köpsel, V.; De Moura Kiipper, G.; Peck, M.A. Stakeholder Engagement vs. Social Distancing-How Does the COVID-19 Pandemic Affect Participatory Research in EU Marine Science Projects? Marit. Stud. 2021, 20, 189–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The Directorate of Health and The Department of Civil Protection and Emergency Management COVID-19 in Iceland—Statistics. Available online: https://island.is/en (accessed on 13 July 2024).

- Kähkönen, T. Remote Work in the Finnish Defence Forces: Employees’ Experiences of Changes in Organisational Culture. Sec. Def. Quart. 2024, 48. Available online: https://securityanddefence.pl/pdf-176071-99039?filename=Remote%20work%20in%20the.pdf (accessed on 13 July 2024). [CrossRef]

- Janoth, J.N.; Abu, M.; Sakdapolrak, P.; Sterly, H.; Merschroth, S. The Impact of Migration on Culturally-Embedded and Subjective Perceptions of Habitability in a Context of Environmental Change: A Case Study from Northern Ghana. Erdkunde 2024, 78, 35–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, J.; He, W.; Zheng, Y. Awareness of Spontaneous Urban Vegetation: Significance of Social Media-Based Public Psychogeography in Promoting Community Climate-Resilient Construction: A Technical Note. Atmosphere 2023, 14, 1691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kouhia, A. Crafts in the Time of Coronavirus. M/C J. 2023, 26. Available online: https://journal.media-culture.org.au/index.php/mcjournal/article/view/2932 (accessed on 13 July 2024). [CrossRef]

- Del Soldato, E.; Massari, S. Creativity and Digital Strategies to Support Food Cultural Heritage in Mediterranean Rural Areas. EuroMed J. Bus. 2024, 19, 113–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konnov, A.; Khmelnitskaya, Y.; Dugina, M.; Borzenko, T.; Tysiachniouk, M.S. Traditional Livelihood, Unstable Environment: Adaptation of Traditional Fishing and Reindeer Herding to Environmental Change in the Russian Arctic. Sustainability 2022, 14, 12640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longhurst, R. Semi-Structured Interviews and Focus Groups. In Key Methods in Geography; Clifford, N., French, S., Valentine, G., Eds.; SAGE: London, UK, 2016; pp. 143–156. [Google Scholar]

- Manzo, L.C.; Pinto de Carvalho, L. The Role of Qualitative Approaches to Place Attachment Research. In Place Attachment; Manzo, L., Devine-Wright, P., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2020; pp. 111–126. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, G.; Raymond, C. The Relationship between Place Attachment and Landscape Values: Toward Mapping Place Attachment. Appl. Geogr. 2007, 27, 89–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).