Abstract

The 21st century, known as the “metropolitan century”, saw urban populations exceed half the global populace. By 2035, emerging metropolises, particularly in Asia and Africa, highlight the urgent need for research on urban growth, demographics, and mobility’s role in sustainable development. The objective of this study is to explore the key aspects of mobility essential for sustaining metropolitan regions, with a focus on the case of Greater London. The research aims to understand, through interview analysis and urban theories, how mobility contributes to socio-spatial equity, connectivity, and integrated governance, highlighting the importance of sustainability—such as decarbonization and the promotion of non-motorized transport—in the context of global sustainable development commitments. This research, through a convergent analysis of interviewees’ responses, has identified thirty-one fundamental attributes to enhance our understanding of sustainable mobility. The results indicate that mobility is a key driver for socio-spatial equity, connectivity, and integrated governance within metropolitan regions; it also shows that successful infrastructure work necessarily calls for collaboration between different administrative levels. Finally, the imperative for sustainability in mobility—as exemplified by decarbonization and the encouragement of non-motorized transport—arises as an urgent element in ordering development at the urban scale vis-à-vis global sustainability commitments, such as SDG 11.

1. Introduction

The twenty-first century is often referred to as the “metropolitan century” [1], due to the rapid urban growth. Recent projections suggest that the global population will peak at 10.3 billion around the 2080s before starting to decline, marking a shift from earlier estimates [2]. By 2035, around 325 new metropolitan areas are expected to emerge, mainly in Asia and Africa, while Europe’s population stabilizes, and Latin America experiences slower growth. Currently, Asia leads with 1038 metropolitan areas, comprising 56.11% of the global total, followed by Western Europe (15.76%), Latin America and the Caribbean (12.5%), Africa (11.7%), and Eastern Europe (3.9%) [3]. These metropolitan areas and their surrounding municipalities are significant drivers of national economies, contributing up to a third of the global economy.

This rapid urban expansion, particularly in Asia and Africa, highlights the urgent need for sustainable urban development that integrates both human and environmental factors. Despite efforts by [1,4] to standardize metropolitan definitions, research often overlooks the complex interrelationship between human activities and the movement of goods. Effectively managing these densely populated and economically critical areas requires a tailored approach that addresses infrastructure, urban networks, and mobility while considering each region’s unique characteristics, such as migration, economic growth, and community needs. To address mobility’s critical role in shaping metropolitan life, specific legislative and planning strategies must be developed [3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15].

The complexity of metropolitan regions, especially Functional Urban Areas (FUAs) in Europe, often challenges the boundaries of conventional urban management, where mobility issues extend beyond municipal limits [4]. Academic research plays a crucial role in understanding these dynamics, particularly how urban planning and mobility influence each other. Studies by [16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25] emphasize the mutual influence of these two factors. Winston Churchill’s quote, “First we shape our mobility system, and afterwards that mobility system shapes us”, as cited by [8,26], encapsulates this interplay well. Similarly, research on metropolitan mobility benefits from a robust scholarly foundation that integrates historical and contemporary perspectives. Studies by [3,14,15,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36] provide critical insights into the complexities of mobility in metropolitan areas.

Mobility profoundly influences urban life, affecting economic, political, and societal dimensions [1]. It is a key driver of regional growth and enriches urban experiences, reflecting societal behavior [37,38]. Population density, for instance, impacts mobility patterns, revealing shifting community needs. Mobility is also closely tied to sustainability, as transportation—particularly automobiles—accounts for 80% of transportation-related emissions [10,29,39,40]1. Thus, transitioning to sustainable mobility is critical. Frameworks such as the New Urban Agenda and the Sustainable Development Goals underscore the importance of sustainable mobility in creating resilient urban communities [1]. Addressing climate change through sustainable mobility, including decarbonization, housing risk assessments, and transport policies, is increasingly important [41,42,43,44].

This emphasis aligns with broader efforts to improve intelligent transport systems and assess mobility’s broader impact on urban development [45,46]. A deep understanding of governance, urban dynamics, and sustainable mobility is essential for effective planning [47,48]. In ref. [24], stress is placed on the need for long-term, evidence-based planning, projecting urban development and sustainability trajectories through 2065, and calls for a unified approach are made to addressing climate change’s effects on mobility [49].

London’s experiences encapsulate the broader context of urban mobility and sustainability, stressing the importance of comprehending how cities manage sustainable mobility’s complexities. This research aims to unravel how metropolises like Greater London tackle sustainable mobility challenges and opportunities. The research question is: How are the different dimensions of mobility perceived and what are the essential attributes needed to guarantee the sustainability of a metropolitan region?

The main objective of this study is to analyze the various dimensions of mobility to define the essential attributes required for making a metropolitan region sustainable. Achieving this broad aim involves two targeted goals. The first specific goal is to explore the perceptions of diverse stakeholders regarding the various dimensions of mobility, with the objective of uncovering how these dimensions are understood and prioritized in the context of sustaining metropolitan regions. This step is crucial for highlighting the spectrum of stakeholder views on mobility’s impact on essential urban interests like accessibility, environmental sustainability, and social inclusivity, using qualitative research methods. The second specific goal aims to extract and articulate the essential attributes of mobility that are considered vital by stakeholders for the sustainability of metropolitan regions. This involves a qualitative analysis to pinpoint both agreements and differences in stakeholder opinions on what makes mobility sustainable, focusing on aspects such as policy frameworks, technological advancements, and strategies for community engagement. These specific goals not only support the main objective but also deepen our comprehension of mobility’s critical role in fostering sustainable metropolitan environments.

This study is structured into four principal sections, beginning with the Theoretical Background, which explores the Metropolitan Phenomenon, Greater London, and its recent policies and programs. Following this, the Method section describes the case study approach, qualitative research phase, and data collection methods employed. The third section, Findings, presents an analysis of general documents related to Greater London, the evaluation of interviewees, and the subcategories for examination. The study concludes with Concluding Remarks, summarizing its contributions to academic discourse on the subject and providing insightful, substantiated conclusions.

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Metropolitan Phenomenon

The term “metropolis”, originally meaning a mother city in Greek, now signifies power and prestige in various contexts. Modern definitions vary, including megalopolis, metropolitan regions, urban agglomerations, and Functional Urban Areas, each applying specific criteria to identify metropolitan characteristics [3,6,50,51,52,53,54,55,56]. Cities shaped by historical contexts require sound urban planning due to their impact on mobility, crucial for socioeconomic growth. Mobility, encompassing urban movements, reveals behavioral patterns and connects people, goods, and locations [37,40]. Sustainable mobility, balancing environmental and socioeconomic factors, aligns with global policies and integrates mobility analyses into urban dynamics [1,47]. The interplay between metropolitan areas, mobility, and climate change necessitates comprehensive adaptation strategies. Research highlights the importance of community-led initiatives and sustainable transport solutions in reducing greenhouse gas emissions [57,58,59]. The Urban Adaptation Index (UAI) and Sustainable Urban Mobility Plans (SUMPs) address urban mobility sustainably, balancing climate objectives with equitable accessibility [60,61]. This study evaluates urban resilience and mobility strategies, using theoretical frameworks to inform sustainable policymaking.

The research is based on Central Place Theory (1966) and the Growth Pole Theory (1955). In ref. [62] (Table 1), the commonalities between these theories were identified. The analysis involved: (i) identifying basic concepts from each theory; (ii) interpreting concepts in relation to metropolitan realities; (iii) correlating the concepts between theories; (iv) detecting the conditions crucial for each concept; and (v) developing a minimal classification for concepts. Key concepts included: (i) territory study necessitates location; (ii) functional hierarchy depends on scale; (iii) regions require vision coverage; (iv) mobility is essential for connection and road dependency; (v) urban networks involve mobility; (vi) urbanization links to a phenomenon; and (vii) investment concentration requires economic context analysis.

Table 1.

Relationship between the announced common concepts of theories and recent concepts. Note: Adapted from [62]. Copyright 2021.

Converging concepts in both theories require specific conditions, categorized as physical (tangible aspects) or non-physical (intangible phenomena). Each concept’s existence depends on fulfilling its primary condition, forming a hierarchical structure essential for understanding urban and metropolitan dynamics [33].

In the 21st century, cities confront challenges such as urbanization and climate change. Refs. [14,63] discuss how globalization centralizes economic power in cities, altering urban dynamics. Ref. [64] explores the sharing economy’s contribution to sustainability and urban mobility. Refs. [28,32,65] introduce the “open city” concept, advocating for porosity in urban planning to enhance integration. In ref. [1] urban areas’ role in achieving Sustainable Development Goals through sustainable urbanization is emphasized. Additionally, the text highlights the importance of integrating climate considerations into urban planning, as noted by [29,30,33]. It concludes with the advocacy by [27,31] for scenario planning as a strategic tool to address urban challenges, emphasizing adaptability and stakeholder involvement for a more resilient and inclusive urban future.

Ref. [33] integrates these concepts, demonstrating that the study of metropolitan phenomena can be approached through the analysis of various dimensions including territory, scale, place, networks [15], urbanization [14,35,36,63], urban economy [35,36,64], culture and identity [28,32,65], innovation [1,66,67], climate change [29,30,33], and foresight [27,31,67].

2.2. Greater London

In the contemporary urban landscape, the intricate dynamics between climate change response and urban mobility have emerged as pivotal determinants of metropolitan sustainability. Analyzing London’s Climate Response and its Implications for Metropolitan Sustainability seeks to illuminate this nexus, focusing on London’s strategic endeavors to navigate the challenges posed by climate change. Through an in-depth examination of initiatives such as the UK Climate Impacts Program (UKCIP) and the thorough assessment of climate impacts, this study endeavors to unravel how mobility, in its myriad forms, plays a crucial role in fostering or impeding the sustainability of metropolitan regions.

London’s diverse strategies to enhance environmental sustainability and mobility are central to this analysis. The research highlights the key mobility attributes identified by stakeholders as essential for the sustainable development of metropolitan areas. Additionally, the study provides a strategic analysis of London’s environmental initiatives, emphasizing the London Environment Strategy’s shift towards integrating urban mobility with environmental sustainability.

By examining London’s comprehensive strategies for improving air and water quality, reducing greenhouse gas emissions, and strengthening flood defenses, this study aligns with the broader academic goal of identifying the critical elements for metropolitan sustainability. It emphasizes the importance of integrating stakeholder perspectives with environmental strategies, presenting a framework for sustainable mobility that addresses climate change impacts and enhances urban livability.

This holistic approach demonstrates London’s commitment to creating a resilient, sustainable, and thriving metropolitan region. The city’s model of integrating environmental sustainability into urban mobility planning and policy development serves as a valuable reference for other metropolitan areas.

2.3. Mobility and Environmental Sustainability: Analyzing London’s Climate Response and Its Implications for Metropolitan Sustainability

This study seamlessly aligns with analyzing mobility’s role in fostering sustainable metropolitan regions, focusing on London’s climate change response through the UK Climate Impacts Program (UKCIP) and comprehensive climate impact assessments. Emphasizing climate scenarios, environmental, social, and economic impacts, and adaptation strategies highlights the critical interplay between sustainability and urban mobility [68].

The climate impact studies and adaptation options provide a foundation for exploring mobility’s essential attributes for metropolitan sustainability. Examining issues like flooding, water resources, health, biodiversity, and transport offers insight into urban mobility’s environmental dimensions and its interconnectedness with urban planning and policymaking. Adaptation options and policies, such as sustainable urban drainage systems, water-efficient appliances, and infrastructure adjustments, are integral to sustainable mobility frameworks. These measures address climate change impacts, improve urban livability, reduce the reliance on unsustainable transport, and promote green spaces. Integrated planning and a multifaceted approach to climate change impacts align with the study’s broader objectives, emphasizing sustainability and resilience in urban mobility planning. Comprehensive strategies across sectors, as seen in Greater London’s transport, economic development, and emergency preparedness approaches, exemplify the holistic perspective needed for sustainable metropolitan regions [68].

2.4. Integrating Urban Mobility and Environmental Sustainability: A Strategic Analysis of London’s Environmental Initiatives (2018)

The 2018 London Environment Strategy aligns with this study’s objectives to analyze the mobility dimensions and define the attributes for sustainable metropolitan regions. This evolution from initial climate change responses to strategizing sustainability marks a paradigm shift towards integrating mobility and environmental sustainability [69].

London’s commitment to improving air and water quality, reducing greenhouse gas emissions, and bolstering flood defenses exemplifies a multifaceted approach to sustainability. These measures are essential for creating a resilient metropolitan region. The emphasis on revitalizing urban spaces and mitigating climate change aligns with the study’s goals, highlighting the importance of stakeholder insights in shaping policies for a sustainable region [69].

The Greater London Authority’s strategy integrates stakeholder input, focusing on reducing carbon emissions, advancing renewable energy, and improving waste management. Enhancements to green infrastructure and air quality ensure the sustained viability of metropolitan regions. The strategy’s multi-dimensional approach blends policy measures with objectives, fostering a greener, sustainable, and resilient city prepared for future challenges. This strategy underscores the importance of effective governance, sustainable urban development, and robust infrastructure in environmental stewardship, paralleling the scholarly emphasis on sustainable mobility [69].

3. Method

3.1. Case Study

The research strategy of adopting the case study method is widely utilized by various authors across different topics related to metropolises such as urban mobility [70], levels of information mobilization for citizens [71], the phenomenon of reurbanization [72], collaborative planning [73], the perspective of elderly customers in delivery service [74], case study understanding [75], and metropolitan planning organization [76]. The study conducted by [77] synthesizes a range of prior research and proposes a comprehensive analytical framework for the examination of case studies. The author outlines seven stages for conducting case study research with the aim of validating theories and applying them to the chosen study object. These research phases include Development of Instruments and Protocols, Data Collection, Data Analysis, Formulation of Hypotheses, and Conclusions.

The methodology employed in this study included data analysis, a review of academic studies and documents, and qualitative interviews. It utilized academic databases and international platforms to identify references and studies exploring the relationship between metropolitan regions, mobility, and climate change. Additionally, it reviewed the relevant literature, including books and scientific articles, to understand the subject matter and its evolution within the context of this research. A specific focus was placed on analyzing the current policies related to climate change in the Greater London area and their impact on mobility. Lastly, qualitative interviews were conducted with subject matter experts to gain insights into their perceptions regarding the research objectives. This comprehensive approach ensured a thorough understanding of the dynamics at play and supported the development of well-informed conclusions.

3.2. Qualitative Phase of Research

This research employed qualitative methodologies to examine urban and metropolitan issues, drawing on frameworks from [78,79]. The study concerning Greater London was structured into five distinct phases: the articulation of a multicultural researcher’s perspective, the establishment of a theoretical paradigm, the development of a research strategy, the collection and analysis of data, and the interpretation of results. This process began with the formulation of research questions and the selection of appropriate ethical paradigms, followed by comprehensive literature reviews and the application of chosen methodologies to probe the multicultural dynamics of Greater London.

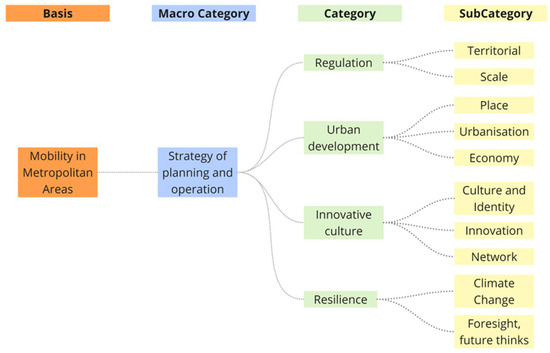

The third and fourth phases were centered on qualitative interpretation and analysis, involving active engagement with diverse communities. This was accomplished through interviews across governmental, academic, and business sectors, focusing on participant selection, qualitative data analysis, and the synthesis of findings into the existing theoretical framework to produce a detailed report. The study incorporated interviews with eight experts, designed to delve into the intricacies of mobility and metropolitan issues as depicted in the main structure (Figure 1). The categories of analysis in the present study were based on previous research that developed the current framework, which systematizes the key aspects of mobility in metropolitan areas. The framework is organized around the basis of mobility in metropolitan areas, linked to the macro category strategy of planning and operation. From this macro category, four main categories emerged: Regulation, Urban Development, Innovative Culture, and Resilience. Each of these categories was further divided into specific subcategories. Regulation covers aspects such as Territorial, Scale, Place, Urbanization, and Economy. Urban Development focuses on Culture and Identity and Economy, while Innovative Culture includes Innovation and Network. Lastly, Resilience addresses critical issues such as Climate Change and Foresight, and Future Thinking. This framework provides a structured view of the factors influencing the urban mobility in metropolitan regions. From this framework, the interview questions were derived, ensuring that each category and subcategory were thoroughly explored during the qualitative research phase.

Figure 1.

The method employed follows a structured analysis framework. Note: Adapted from [62]. Copyright 2021.

The framework guided the development of the interview questions, linking theoretical foundations to practical and policy-relevant discussions (Table 2). They aimed to gather information that connects directly with the specific documents analyzed. This approach ensures a comprehensive exploration of the subject matter, enabling a detailed understanding of how current data and concepts within the field either align with or diverge from established theories and recent research findings. By doing so, the study seeks to uncover new insights and perspectives, contributing to the ongoing discourse in urban and metropolitan studies.

Table 2.

Subcategories and Questions. Note: Elaborated by Ribeiro and Fachinelli, 2023. Copyright 2023.

3.3. Data Collection

Over four months, interviews with multidisciplinary experts from sectors including community, academia, third sector, private, and public were conducted to gather diverse insights (Table 3).

Table 3.

Expert Panel Profile and Sector Affiliation. Note: Elaborated by Ribeiro and Fachinelli, 2023. Copyright 2023.

This study specifically focused on the critical issue of climate change, aiming to consolidate the findings within this pressing global context. All the sessions were recorded with the participants’ explicit consent, evidenced by signed informed and voluntary consent forms, except for one participant who chose to remain anonymous. After the interviews, audio recordings were transcribed word for word using the noota.ai platform to ensure the fidelity of the transcription. The researchers reviewed each transcription to verify the accuracy of the documented discussions, guaranteeing the precise capture of the dialogues.

4. Findings

The findings were derived from an examination of key documents, publications related to Greater London, and an analysis of the conducted interviews.

4.1. Greater London (General Documents)

London, as a global city, competes for international investment, talent, and tourism, necessitating the enhancement of its multilevel urbanism to remain competitive with other global cities [80] (p. 190). Established under Emperor Claudius in 43 AD, London’s Roman legacy is still evident in the names of its ancient gates. After the Romans left in 410 AD, London faced invasions by the Angles, Saxons, Vikings, and Normans, the latter of which made it the capital in 1066. Despite setbacks like the Great Fire of 1666, London flourished, particularly with the construction of St. Paul’s Cathedral and the expansion between the Cities of London and Westminster [81]. London’s history illustrates its resilience and expansion, evolving from post-Roman invasions to its legal recognition as a metropolis.

The term “Metropolis” was legally recognized in 18552, extending London’s administrative reach beyond the City of London and leading to the establishment of the Metropolitan Region in 1888. The first item in Section 40 [82] was pivotal in centralizing London’s metropolitan services, designating it as an administrative county:

(1) The Metropolis shall, on and after the appointed day, be an administrative county for the purposes of this Act by the name of the administrative county of London [82].

The 19th century marked transformative changes, including the introduction of railways in 1836 and the construction of major train stations and the underground railway by 1862, reshaping London’s infrastructure and social fabric [81]. The city’s population surged due to industrialization, which created industrial slums, prompting urban improvements like Regent’s Park to enhance public health [83] (p. 28).

Key developments included the rebuilding of Parliament and the British Museum’s inauguration, while policies like the Green Belt of the 1930s and the 1944 Greater London Plan reflected garden city ideas to manage housing and urban growth [84].

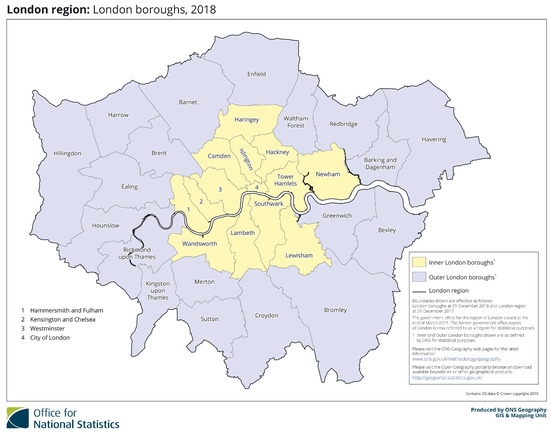

Post-war London saw further suburban expansion and the establishment of the Greater London Council (GLC) in 1965. Although the GLC was dissolved in 1986, London retained an administrative framework of 32 boroughs and the City of London (Figure 2), each responsible for local planning and services3 [81,84].

Figure 2.

London Region: London boroughs. Note: Office for National Statistics, 2018, from Office for National Statistics, 2018.

The 20th century saw a focus on sustainable development and economic regeneration [81], influenced by modernist urbanism, including the introduction of elevated pedestrian systems in the 1960s [80] and efforts to understand movement patterns and transportation networks [85,86,87].

The 21st century sees London engaging in global competition through urban strategies like “The Developing City 2050”, aiming for inward expansion [80]. This ambition sparks debates around urban growth versus Green Belt rigidity [88] or leading to an expansion far beyond its current size [89]. Effective planning must navigate jurisdictional complexities and align development with public transport [54,88].

Sustainable urbanization strategies are critical to balancing growth with ecological integrity, highlighting the role of urban planning in mitigating climate impacts on biodiversity [90,91,92]. Policies must incorporate climate strategies into urban development to address urbanization’s significant effects on land use, driven by socioeconomic shifts [1,67,93,94].

Historic studies from the 1940s by [92] highlighted cities as biodiversity sources. Contemporary landscape ecology stresses spatial heterogeneity’s importance for conservation, supported by recent research [90,91,95,96,97,98,99,100,101]. The shift toward sustainable development in cities like London reflects the integration of ecological considerations into urban planning.

London’s population has decreased from over 9 million to around 7 million, while the broader metropolitan area holds approximately 12 million people. Urban residents in UK metropolitan centers declined from 71% in 1931 to 60% in 1966 as people moved to the suburbs in search of affordable housing and employment. Megacities now face long commute times, requiring strategic urban planning to address the sprawl and promote sustainable development. Policies must prioritize social networks, economic diversity, and public land management to provide affordable housing and prevent the emergence of new urban issues [89]. As urban planning increasingly focuses on mobility and sustainability, Greater London is chosen for its comprehensive data, unique governance model, global relevance, and focus on Public Transport Accessibility Levels (PTAL), making it an ideal case for studying sustainable mobility and urban sustainability.

4.2. Interview Findings

The study analyzed interviewees’ responses, extracting key statements and organizing them by question. The aim was to connect these responses using predefined subcategories. The researchers highlighted and connected the main statements of each interviewee, noting the similarities and common points to analyze mobility dimensions and define attributes for a sustainable metropolitan region. Subsequently, the findings were explored through predefined subcategories. The researchers identified common points essential for regional sustainability and linked them to classical theories and recent studies. This approach ensured a comprehensive understanding of the necessary attributes for creating a sustainable metropolitan region, contributing significantly to the research.

4.3. Territorial

The interviews reveal a deep emotional connection to Greater London, blending personal and professional lives with the city’s dynamic environment. The interviewees emphasized London’s adaptability and the diverse ways in which residents engage with its spaces, governance, and transportation. Interviewee 1, a lifelong resident of the City of London, expressed a strong emotional investment in the city. Interviewee 3 shared a similar sentiment, describing their initial surprise and quick adaptation to the life in London. Interviewee 7, who arrived for doctoral studies in 2000, described the city as essential to both his career and family life, noting that his children are “true Londoners”. Interviewee 8 emphasized their long-term commitment to improving the city’s quality of life, having studied, lived, and worked in London for many years.

4.4. Scale

The interviews highlighted the complex governance, mobility, and sustainability challenges of Greater London. Interviewee 1 emphasized the City of London’s unique governance structure and collaboration with Transport for London, particularly in large-scale projects like the Elizabeth Line. Interviewees 2 and 3 discussed the semi-autonomous nature of the Greater London Authority (GLA) and the need for coherent regional governance to address the socioeconomic disparities. Interviewee 4 and others pointed out the varying levels of collaboration and identity among boroughs, particularly regarding transportation access. The discussions underscored the importance of cross-borough cooperation and highlighted the disparities in governance and transport networks, with several interviewees advocating for a more unified approach to mitigate the inequalities.

4.5. Place

The discussions surrounding London’s urban landscape focused on its diversity, mobility, and balance between modernization and historical preservation. London’s cultural and ethnic diversity was a key theme, with Interviewee 1 noting the city’s 225 mother tongues as a testament to its inclusivity. Several interviewees highlighted the city’s creative energy, driven by its multiculturalism. Interviewee 4 emphasized the uniqueness of each borough, while Interviewee 8 praised London’s diversity in ethnicity, age, and community. There was also a strong focus on sustainable mobility, with the interviewees advocating for a robust public transport system and the promotion of walking and cycling. The discussions reflected a shared vision for a city that respects its past while embracing future innovation.

4.6. Urbanization

The interviews highlighted the key themes of mobility and sustainability in Greater London’s urbanization, particularly the importance of its comprehensive public transport network, including the Elizabeth Line and metro systems. A recurring theme was the need to integrate equality, diversity, and inclusion into urban regeneration. Managing the balance between urban and rural needs while ensuring equitable access to transport is crucial. The green belt remains essential in controlling the urban sprawl, while migration patterns reflect London’s appeal to a diverse population, influencing housing and development. The rising cost of living and property prices emphasize public transport’s role in maintaining affordability. Interviewee 1 highlighted the ability to enjoy “a very rural life within one hour of London”, showing how transport options allow diverse living conditions. The COVID-19 pandemic has shifted work patterns, prompting a reevaluation of urban planning. Interviewee 7 stressed the need for “alternatives to the car for local journeys”, illustrating the city’s adaptive response. Urbanization and infrastructure development in London are intertwined, as noted by Interviewee 1: “Urbanization has always been the history of London... it’s been urbanized for about 250 years and it’s also had the infrastructure”. Interviewee 2 underscored the city’s advantages in mobility with “fairly good public transport provision”. This longstanding integration of urban growth and transport infrastructure highlights London’s commitment to sustainability. Public transport, with its varied options of trains, buses, the underground, and cycling, remains critical to urban mobility, supporting the city’s dynamic nature. Interviewees 2 and 6 pointed out how easily residents can navigate the city, maintaining its fluid mobility system. Public transport also mitigates the cost of living by enabling residents to live in more affordable areas while commuting to the city center. Multiple interviewees noted that addressing the transport disparities and adopting innovative solutions are crucial for improving mobility and ensuring that London remains accessible. The city’s multicultural environment is central to its urban planning, with Interviewee 2 highlighting how migration enriches London’s socioeconomic fabric. The green belt is a key planning tool to curb the urban sprawl and guide sustainable development, as Interviewee 1 noted that it is a “crucial planning designation”, and Interviewee 8 emphasized the importance of “a strong land use planning framework” to preserve green spaces and promote balanced growth.

4.7. Economy

The interviews underscore the integration of mobility, sustainability, and economic development in Greater London, highlighting the need for a holistic strategy to balance urbanization, infrastructure enhancement, and equitable growth. A key theme was the importance of an efficient public transport system in driving economic sustainability and addressing disparities. The interviewees stressed the need for increased density in the city center (I3), prudent resource allocation, and sustained investment in transport infrastructure to bridge community divides (I4, I7). Projects like HS2 illustrate the complexity of infrastructure spending, with the interviewees advocating for leveraging London’s economic strengths to promote green mobility and enhance public spaces (I1, I3, I8). London’s public transport system plays a critical role in shaping the socioeconomic landscape, supporting both residents and commuters, and driving future development. However, London’s economic dynamism also highlights the spatial inequality, with economic power concentrated in the center and migration patterns amplifying the disparities (I1, I2, I7, I8). These challenges require a balanced urban planning strategy that prioritizes sustainable mobility and addresses the socio-spatial disparities for inclusive growth.

4.8. Culture and Identity

The interviewees unanimously highlighted diversity as London’s greatest strength, enriching its cultural, economic, and social fabric. This diversity fosters innovation, promotes inclusivity, and is essential for sustainable development. London’s diverse population shapes its identity and influences infrastructure and urban planning, with a shared understanding that mobility systems must support both heritage preservation and green solutions. Interviewee 6 stated, “London has been a diverse city for centuries”, while Interviewee 2 described it as “one of the most diverse metropolitan regions globally”. The city’s inclusive nature fosters cultural exchange and unity, as noted by Interviewee 4: “You get educated about other cultures. It helps create a sense of ‘we are one’”. This collective outlook emphasizes the integration of diversity into urban planning and mobility strategies to ensure that London remains vibrant, inclusive, and sustainable. The city’s rich cultural tapestry, reflected in its architecture, cuisine, and literature, further reinforces its global identity, with Interviewee 6 noting, “London’s diversity makes it highly attractive for discovering different literatures”. Despite debates about cultural blending, most of the interviewees, including Interviewee 5, agreed that diversity enriches identities and fosters mutual respect, solidifying London’s position as a dynamic global metropolis.

4.9. Innovation

The interviews from Greater London emphasize innovation in mobility, sustainability, and urban development, focusing on public transportation improvements, micro-mobility adoption, and environmental health. Mobility is viewed as a key driver of urban innovation, integrating social equity, environmental sustainability, and economic growth. Projects like the Elizabeth Line, cycle lanes, and the Ultra-Low Emission Zone (ULEZ) highlight the efforts to reduce car reliance and promote sustainable transport. Interviewee 1 described the Elizabeth Line as “very significant infrastructure”, while Interviewees 3 and 6 cited HS2 and Crossrail as transformative for accessibility and sustainability. Transit-oriented development (TOD) fosters mobility around public transport hubs, with Interviewee 2 noting, “We also call it TOD, transit-oriented development”. Micro-mobility solutions, such as e-scooters and e-bikes, address the gaps in the transportation network, with Interviewee 2 highlighting the rollout of e-micromobility and Interviewee 7 stressing the importance of safe infrastructure for cyclists and pedestrians, especially for children. Environmental initiatives to reduce emissions and improve air quality, such as bus electrification and the ULEZ, reflect a commitment to sustainability. Interviewee 7 noted the importance of “reducing air pollution”, while Interviewee 8 emphasized improvements in air quality. Community-driven initiatives also play a critical role in promoting mobility and safety. Interviewee 5 mentioned, “It’s a great movement in terms of moving around London”, and Interviewee 6 highlighted school streets introduced to prioritize pedestrian safety. These efforts underscore the significance of grassroots innovation in enhancing mobility and fostering a sustainable, inclusive urban environment.

4.10. Network

The interviews emphasize the critical role of an integrated transportation network in Greater London’s sustainability. The interviewees highlighted the efficient public transport, pedestrian and cyclist-friendly mapping, and inter-borough collaboration to address the infrastructure disparities. The key challenges include improving the accessibility for people with disabilities and enhancing the connections in areas with limited rapid transit. Interviewee 1 noted that London has “the most integrated transport network in the UK”, while Interviewees 5 and 6 praised Transport for London’s proactive approach to mobility. Initiatives like “Legible London” and seamless interconnectivity between transport modes are essential for optimizing urban mobility. Collaboration between boroughs and central government is crucial for shaping mobility strategies. Interviewee 2 stressed the importance of inter-borough cooperation, while Interviewee 8 highlighted the role of governance in setting city-wide transport strategies. Accessibility and inclusivity are central concerns, with Interviewee 4 questioning whether people in wheelchairs can access all platforms, and Interviewee 7 stressing the need to address air pollution and congestion through improved accessibility. The interplay between policy implementation and public sentiment is also significant. Interviewee 3 highlighted the gap between mobility network improvements and the city’s rapid population growth, calling for faster policy implementation. Interviewee 6 acknowledged that necessary policies, such as those addressing congestion and pollution, often face resistance. The interviews collectively emphasize that an integrated, inclusive, and well-governed transport network is key to ensuring Greater London’s sustainable development.

4.11. Climate Change

The interviews underscore the vital role that an integrated transportation network plays in Greater London’s sustainability. Expanding public transport, improving pedestrian and cycling access, and fostering inter-borough collaboration are essential steps to address the infrastructure disparities. The key challenges include improving the accessibility for all, particularly those with disabilities, and enhancing the connections in underserved areas. These insights highlight the need for a holistic approach that includes integration, collaborative governance, and environmentally sustainable mobility solutions. The interviewees emphasized the importance of an integrated transport network to enhance urban mobility and connectivity. Interviewee 1 praised London’s efforts, describing it as having the “most integrated transport network in the UK”. Interviewee 5 supported this, commending Transport for London’s (TfL) leadership, and Interviewee 6 reinforced the importance of London’s cohesive mobility network. These comments reflect initiatives like “Legible London” and emphasize seamless connections between various transportation modes as essential to optimizing mobility. Effective governance and collaboration between boroughs and central government are also seen as crucial in developing comprehensive mobility strategies. Interviewee 2 highlighted the need for cooperation among the boroughs and the GLA, while Interviewee 8 emphasized the significance of governance in shaping overarching transport strategies. Interviewee 6 pointed to the need for strong leadership and effective policy implementation to address the challenges such as air pollution, congestion, and mobility efficiency. Accessibility and inclusivity are central concerns, with a focus on equal access for all, particularly individuals with disabilities. Interviewee 4 raised concerns about whether the transport network adequately accommodates those with disabilities, while Interviewee 7 emphasized the importance of improving the accessibility to address air pollution, congestion, and public health issues. The discussion on management and policy implementation revealed the complexities of balancing sustainable growth with public opinion. Interviewee 3 noted a gap between network improvements and population growth, urging quicker policy implementation. Interviewee 6 highlighted the challenge of overcoming public resistance to necessary policies, and Interviewee 7 emphasized the long-term benefits of addressing the environmental and health issues. Interviewee 8 praised London’s integrated transport network compared to other UK and European cities, while Interviewee 6 noted the importance of accommodating various modes of transport to ensure the system’s inclusivity and effectiveness.

4.12. Foresight, Future Think

The interviews emphasize the future of mobility and sustainability in Greater London, focusing on urban development, technological innovation, environmental concerns, and social equity. The key themes included expanding public transport networks, incorporating autonomous buses and electric vehicles, and promoting non-motorized transport like cycling and walking to reduce car dependency and emissions. Interviewee 4 stressed the need to “cater more for all areas, so everyone can move freely”, underscoring the importance of equitable mobility solutions. The interviewees envisioned a shift away from large infrastructure projects like Crossrail, instead focusing on sustainable and accessible technologies. Interviewee 7 saw “64% mode shift of walking, cycling, public transport” by 2050, driven by technological advancements. Innovation in urban mobility highlights digitalization, with tools like remote work reducing physical travel. Interviewee 2 emphasized the role of ICT, noting, “we can walk from home”, while Interviewee 6 saw the potential of data analytics to enhance transportation planning. Technology is also viewed as crucial for safety, with Interviewee 7 projecting fewer road fatalities through tech-enabled solutions. The discussions reflect a strategic shift toward a more integrated, technology-driven transport network focused on accessibility, sustainability, and safety. Climate change is a central concern, with interviewees stressing the need to reduce carbon emissions and prioritize environmental sustainability. Interviewee 2 anticipated a significant reduction in emissions by 2050, while Interviewee 3 called climate change “a top concern”. Practical solutions like reducing private car use are seen as vital for addressing the climate crisis and ensuring health and safety. The focus on public transport and non-motorized mobility was shared among the interviewees. Creating safe urban spaces for walking and cycling, as well as improving the interconnectivity between transport modes, is seen as key to fostering healthier lifestyles and sustainable cities. Stakeholder involvement and collaborative planning are essential to these efforts. Interviewee 1 highlighted the need for safe spaces for public health, while Interviewee 5 emphasized that effective mobility strategies must consider environmental, health, and economic impacts. These insights underscore the importance of creating a livable, resilient, and inclusive urban future.

5. Subcategory Analysis

The provided framework serves as a comprehensive model that elucidates the multifarious interplay between urban planning, sustainability, and mobility within metropolitan regions. It systematically categorizes the key concepts into distinct but interconnected domains: Territorial, Scale, Place, Urbanization, Economy, Culture/Identity, Innovation, Network, Climate Change, and Foresight. This schema highlights the intricate synergy among various urban planning facets and their collective impact on metropolitan sustainability.

The framework depicted offers a comprehensive view of metropolitan development, highlighting the necessity for strategic planning that integrates governance, cultural identity, innovation, and climate resilience (Figure 3). Reflecting the study’s goals, this framework facilitates the understanding of stakeholders’ perceptions of mobility within complex dimensions, identifying the vital attributes for metropolitan sustainability. It emphasizes the importance of considering a wide range of factors, from infrastructure innovations to cultural integration, in devising strategies for sustainable metropolitan areas. The detailed interconnections within the framework, spanning local to global scales, encapsulate the complexity of ensuring sustainable mobility and stress the importance of inclusive, future-oriented urban planning that addresses both present and anticipated challenges.

Figure 3.

Basic attributes according to converging interviewees’ points of view. Note: elaborated by Ribeiro and Fachinelli, 2024. Copyright 2024.

5.1. Subcategory Territorial Analysis

The narratives provided by all the interviewees collectively offer a rich tapestry of insights into the socio-spatial dynamics of Greater London. These personal and professional testimonies shed light on the complex relationship between individuals and the territory, revealing how emotional connections, professional engagements, and participatory actions in urban spaces shape and are shaped by the territorial configurations of London.

Principle of Socio-Spatial Structuring. The principle of socio-spatial structuring is evident in how the interviewees described their engagement with London’s urban spaces. For example, Interviewee 1’s connection to local projects shows how personal activities intersect with the city’s spatial organization. Interviewee 2’s insights on urban regeneration illustrate how socioeconomic developments influence spatial restructuring, reflecting London’s dynamic urban fabric.

Construction of Internal/External Partitions. Emotional and professional connections to London, as shared by the interviewees, delineate internal/external partitions, with personal and career developments within the city fostering a profound sense of belonging and identity in relation to the urban territory.

Fields of Operation. Past, Present, and Emerging Borders: The evolving experiences of the interviewees with London’s urban environment highlight the dynamic nature of territorial borders. The collective narratives reveal how historical legacies, current initiatives, and future aspirations continuously reshape the socio-spatial landscape of London, influencing individual and collective experiences of the city’s territory.

5.2. Subcategory Scale Analysis

The interviewees’ insights align with the concept of “scale” within London’s governance and spatial organization, reflecting the theories of functional hierarchy, Central Place Theory, and socio-spatial structuring. These discussions reveal the complex interplay between governance levels and spatial hierarchies, emphasizing the need for an integrated approach to urban planning in Greater London.

Principle of Socio-Spatial Structuring in Greater London. The socio-spatial structuring of Greater London highlights the relationship between governance, infrastructure, and the disparities among boroughs. Key projects like the Elizabeth Line, spearheaded by TfL, play a critical role in enhancing urban mobility and promoting the collaboration between boroughs. Insights from Interviewees 5, 6, 7, and 8 underline the diverse socioeconomic fabric of the city and the strategic partnerships required to improve connectivity. This framework emphasizes the need for urban planning that addresses London’s socio-spatial complexities, fostering a more integrated and equitable urban environment.

Governance Dynamics and its Organization in Greater London. The governance of Greater London is marked by autonomy, varied administrative practices, and a balance between collaboration and independence among the boroughs. The interviewees highlighted the unique governance structures, particularly the City of London’s distinct approach and its impact on major projects like the Elizabeth Line. This governance model reflects functional hierarchy and Central Place Theory, where the boroughs align with city-wide policies led by the GLA and TfL. Interviewees 1, 4, and 5 noted the multi-layered governance system, characterized by both collaboration and independence, which presents the challenges and opportunities in managing a city as complex as London. The coordination between the boroughs and regional authorities is essential to ensuring that the spatial and functional organization of the city serves all communities effectively.

5.3. Subcategory Place Analysis

The interviewees provided diverse insights into the concept of “place” in the context of Greater London, emphasizing its rich cultural, historical, and socio-spatial diversity. Their perspectives reflect principles from Christaller’s Central Place Theory and Perroux’s Growth Poles theory, underlining the city’s unique socio-spatial structure. These shared narratives offer a deep understanding of London’s identity, shaped by its multiculturalism, heritage, and socioeconomic dynamics.

Principle of Socio-Spatial Structuring. The interviews highlight the complexity of London’s socio-spatial structure, shaped by the city’s diverse boroughs, each with its distinct history and cultural identity. Interviewees 2, 3, and 8 discussed how London’s multiculturalism, inclusivity, and balance between historical preservation and modern advancements define its character. With over “225 mother tongues” and policies promoting “dense housing and low traffic neighborhoods”, London has emerged as a city committed to fostering an interconnected, tolerant environment. The city’s evolution, embracing both its historical roots and its dynamic future, reaffirms its status as a global hub. This socio-spatial structuring reflects London’s commitment to innovation, connectivity, and diversity, continuously shaping its global identity.

Market, Traffic, and Administrative Separation. London’s role as a central hub aligns with the market principle of Christaller’s theory. Interviewee 1 emphasized London’s multiculturalism, dense housing, and progressive transport policies, illustrating its central role in serving a broad region with diverse services. The efficient public transport system, including the Elizabeth Line, supports the city’s function as a regional traffic hub. The administrative separation is also evident in the complex governance structures and the cooperative relationship between London’s boroughs and the GLA, showcasing the city’s unique internal administrative dynamics.

Place-Centrism. Interviewees 2 and 5 focused on London’s efforts to preserve its historical character while embracing diversity and urban regeneration, reflecting the concept of Place-Centrism. This attachment to London’s unique identity—marked by its history, cultural richness, and global prominence—drives regional development and attracts skilled labor and investment. London’s distinctive centrism highlights its international influence and vibrant urban dynamism, sustained through a robust transport network and collaborative governance across its boroughs. This Place-Centrism underscores London’s role as both a cultural and economic center, continually adapting while preserving its core identity.

5.4. Subcategory Economy Analysis

The interviewees provided valuable insights into the complex dynamics of economic concentration and investment in London, highlighting the links between urbanization, economic development, and sustainability. These reflections align with the academic frameworks asserted by [14,64], particularly regarding the opportunities and challenges posed by urban growth, the sharing economy, and sustainable urban planning.

Investment and Infrastructure for Mobility. The development of transportation infrastructure, as discussed by I3 and I7, exemplifies public investment’s role in facilitating urban mobility and economic growth. The Elizabeth Line, for example, enhances the connectivity within London and between its urban and peripheral areas, echoing Harrison and Growe’s advocacy for innovative urban planning solutions to mobility challenges. This investment not only supports economic activities but also contributes to the environmental sustainability goals highlighted by Mi and Coffman, through reduced emissions and the promotion of green mobility options.

Economic Concentration Spatial Inequality. Interviewees I1 and I6 emphasized London’s role as a global hub for finance, technology, and the creative industries, attracting talent and driving GDP growth. This economic concentration fuels innovation and underscores London’s global economic significance. These dynamics align with Mi and Coffman’s views on how the sharing economy can support sustainability and urban mobility by leveraging economic hubs like London to pilot innovative, eco-friendly solutions. However, I2 and I8 highlighted the spatial inequalities that this concentration exacerbates, both within London and between the capital and other UK regions. The need for balanced investment and governance strategies to address these disparities is clear. Mi and Coffman also stress the importance of aligning economic growth with social welfare, ensuring that the benefits of concentrated economic activity extend beyond central business districts to foster social and economic equity across the city.

Sustainability and the Sharing Economy. Interviewees 4 and 5 discussed the potential of the sharing economy to address the urban sustainability challenges, emphasizing the need for strategic investments that benefit communities. This aligns with Mi and Coffman’s findings on the environmental and social benefits of the sharing economy. London, with its economic resources, has the potential to integrate sustainable practices with economic development, leveraging the sharing economy to enhance urban resilience and livability.

5.5. Subcategory Urbanization Analysis

The interviewees provided a comprehensive view of urbanization in London, focusing on the interaction between urban growth, mobility, socioeconomic dynamics, and spatial planning. Their perspectives offer practical insights into urbanization, economic globalization, and metropolization, reflecting on the challenges and strategies discussed by [14,63].

Urbanization and Urban Planning (dynamic land use planning and its infrastructure). The interviewees emphasized the critical role of land use planning and infrastructure in shaping London’s urban growth, particularly through its extensive public transport system. This aligns with Benko’s observations on the influence of economic concentration in metropolitan areas. Interviewee 7 highlighted the Green Belt Policy’s role in managing the urban sprawl and promoting a denser, more sustainable urban core. This spatial management approach seeks to balance urban expansion with ecological preservation. Interviewees 2 and 3 discussed how land occupancy reflects the spatial dynamics and socioeconomic factors, pointing to the disparities between the inner and outer boroughs. Their observations underscore the complexity of London’s socio-spatial fabric, shaped by demographic shifts and housing policies, echoing Harrison and Growe’s focus on urban development challenges.

Mobility and Urban Planning. Mobility plays a key role in urbanization, with all the interviewees emphasizing public transport’s importance in enhancing the integration and accessibility across London. Their discussions highlighted the need for innovative mobility solutions to address the urban planning challenges, reinforcing Harrison and Growe’s call for a cohesive approach to urban mobility. This illustrates the intrinsic link between mobility and urban planning in shaping sustainable metropolitan development.

5.6. Subcategory Culture and Identity Analysis

The interviewees’ reflections on diversity’s impact on the culture and identity in London align with academic discussions on urban adaptability and the “open city” concept, as explored by [28,32,65]. Both the interviewees and these frameworks emphasize that cities, like sponges, can absorb diverse influences while maintaining their core identity, fostering environments which are rich in culture and inclusivity.

Governance and metropolitan cosmopolitan character. Interviewees 4 and 5 stressed the role of governance and urban planning in supporting or limiting the positive impacts of diversity. They discussed the need for equitable infrastructure and critique policies that may hinder cultural exchange, echoing academic arguments that governance must encourage adaptability and cohesion in cities. Their insights emphasize the importance of inclusive governance structures in fostering a cosmopolitan urban character, enriching metropolitan life through diversity.

Enrichment through Diversity. The interviewees vividly illustrated how cultural diversity enriches London’s identity, resonating with Richard Sennett’s idea of the “open city”, where permeable boundaries enable integration and interaction. Interviewee 8’s statement, “London is open”, captures the city’s welcoming spirit, fostering a dynamic and diverse environment. Interviewees 2 and 3 further highlighted how London preserves its historical legacy while embracing modern changes, creating a vibrant cultural and social landscape. This underscores that urban diversity is not just a demographic fact but a source of cultural enrichment and social vitality.

Cultural Integration and Identity. Interviewees 1 and 8 delved into London’s historical cosmopolitanism, noting its role in driving the city’s creativity, dynamism, and economic growth. Their observations align with the idea of urban “porosity”, which sees cities as adaptable spaces that promote seamless cultural integration. This approach fosters a sense of belonging among diverse populations and highlights the critical role of cultural integration in shaping urban identity. The discussion affirms London’s success in creating an environment that not only accommodates diversity but actively engages with it, enriching the city’s social fabric and identity.

5.7. Subcategory Innovation Analysis

The interviewees’ insights on urban mobility and infrastructure innovations in London, aligned with UN Habitat’s goals for sustainable urbanization [1,67], especially Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 11, highlight the need for adaptive city planning and sustainable practices to create inclusive, resilient, and sustainable metropolitan regions.

Infrastructure (cycling and walking) and Mobility Innovations. The introduction of the Elizabeth Line, noted by multiple interviewees, represents a significant leap in London’s urban mobility, enhancing the connectivity across the city. This aligns with SDG 11, which emphasizes upgrading public transport to foster sustainability. Innovations like electric mobility options (e-scooters and e-bikes) and improvements to pedestrian and cycling infrastructure reflect a strategic focus on environmentally friendly transport solutions, supporting global goals for green, accessible cities.

Public Spaces and Accessibility. The reallocation of highway space for walking and cycling, along with the development of low-traffic neighborhoods, demonstrates London’s commitment to creating safer and more accessible public spaces. These initiatives, mentioned by several of the interviewees, align with sustainable urbanization principles, promoting social interaction and physical well-being while enhancing community resilience.

Social and Economic Equity. The discussions around major infrastructure projects like HS2 and Crossrail, particularly by Interviewee 3, emphasized the importance of balancing innovation with social justice. These projects highlight the role of governance in ensuring that economic development is coupled with social and ecological welfare, advocating for an approach that prioritizes innovation, equity, and sustainability in urban development.

Behavioral Change and Environmental Sustainability. Efforts to improve the air quality through the ULEZ and the electrification of buses, as noted by Interviewee 8, represent proactive steps in addressing the environmental challenges. By encouraging walking and cycling, these initiatives contribute to reducing urban emissions and promoting sustainability, aligning with SDG 11’s vision for sustainable cities and communities. These strategies reflect a commitment to fostering behavioral change and environmental stewardship.

5.8. Subcategory Net Analysis

The interviewees’ insights, when analyzed through the theoretical frameworks of urban networks and connectivity, align with principles such as Christaller’s Central Place Theory and Perroux’s planned hub growth. These discussions provide a valuable lens for understanding the dynamics of urban planning, integration, and mobility in London.

Integrated Transport Networks. The majority of the interviewees, especially Interviewee 1, emphasized the efficiency of London’s integrated transport system, highlighting initiatives like Legible London, which enhance urban mobility through clear visual and physical connections. This integration reflects the concept of nodal connectivity, facilitating easy navigation and access across the city. The approach aligns with urban planning theories, reinforcing the importance of cohesive transport networks in improving movement and the overall urban quality of life.

Governance and Collaboration Across Boroughs. Interviewee 2 discussed the socioeconomic landscapes across London’s boroughs to underscore the principle of socio-spatial structuring, emphasizing the need for greater collaboration between boroughs and the GLA. A unified governance model is critical to address the challenges posed by administrative divisions and to create a seamless urban mobility network. Such collaboration ensures that mobility solutions are equitable and responsive to the diverse needs of London’s communities.

Accessibility and Inclusivity. Interviewee 4 highlighted the importance of inclusivity in London’s transport network, especially for individuals with disabilities. This reflects the need for urban planning that prioritizes social equity and accessibility. Similarly, Interviewee 3 pointed out gaps in fast public transport in certain areas of Greater London, emphasizing the need for an extensive, equitable transport network that connects both urban and suburban areas. Ensuring comprehensive and inclusive mobility is essential for creating a well-connected city.

Forward-Looking Mobility Strategies and Policy Influence. Interviewees 5 and 6 underscored the role of TfL in driving innovation, particularly by integrating technology-driven services like Uber and Bolt into the city’s transport matrix. This approach illustrates the “networks of networks” concept, where traditional and modern mobility solutions merge to create an adaptive transport system. Interviewee 7 added that a harmonized legislative and strategic framework is crucial for implementing unified transport policies across boroughs, ensuring consistency and coherence in London’s sprawling urban landscape.

5.9. Subcategory Climate Change Analysis

The interviewees’ insights on addressing climate change through urban mobility and planning initiatives reflect a comprehensive strategy to mitigate and adapt to climate impacts in metropolitan regions. These discussions connect with broader themes of climate action, urban planning, and sustainable development, highlighting the key areas for future exploration.

Climate Change and Sustainability. Decarbonizing transport and enhancing pedestrian and cycling infrastructure are central to addressing climate change and ensuring sustainable mobility. This approach emphasizes diverse yet interconnected solutions to build a low-carbon future.

Decarbonization and Electrification of Transport. The shift toward decarbonizing and electrifying transport is critical in reducing greenhouse gas emissions, as emphasized in the [15] report. Transitioning from petrol and diesel vehicles to electric vehicles (EVs), alongside expanding EV charging infrastructure, represents a pivotal move toward cleaner transport. The interviewees stressed the need for accessible public transport, especially in the outer London boroughs, to ensure that sustainable mobility options are equitable and effective in reducing emissions across the metropolitan area.

Pedestrianization and Cycling Infrastructure. The interviewees highlighted the importance of pedestrian and cycling infrastructure as key elements of sustainable urban planning. By reducing car dependency, these initiatives help mitigate the urban heat island effects and lower emissions. Investments in non-motorized transport are essential for creating healthier, more sustainable cities, reinforcing the role of infrastructure in shaping livable urban environments.

Integrated Planning Beyond Administrative Boundaries. Effective climate change mitigation requires planning that transcends administrative boundaries. The interviewees emphasized the need for a unified, city-wide approach to climate action, where resources and strategies are coordinated across the boroughs. This integrated planning allows for more efficient and impactful sustainability efforts, demonstrating the importance of collaboration in achieving environmental goals.

Climate Change Mitigation Strategies. Initiatives like the ULEZ, congestion charges, and low-traffic neighborhoods are innovative strategies to reduce emissions. These measures play a key role in promoting sustainable urban mobility and steering cities toward carbon neutrality. Through targeted policies, cities can actively reduce their environmental impact, highlighting the role of urban planning in climate change mitigation.

Adaptation to Climate Change Impacts. Proactive adaptation strategies, such as those discussed by Interviewee 8, address the direct impacts of climate change, including heatwaves and flooding. These plans focus on building resilience in metropolitan areas by ensuring that infrastructure, public health, and ecosystems are protected from climate-related challenges. Adaptation measures are crucial for safeguarding urban regions against the unpredictable effects of climate change.

5.10. Category Future Thinking/Future Sights Analysis

The interviewees’ insights on urban mobility, planning, and climate change adaptation provide a strong basis for integrating “Future Thinking/Foresight” into discussions on urban development and resilience. Synthesizing these reflections with the principles of scenario planning and adaptability from [27,31], the key areas for future-oriented urban studies include:

Innovative Urban Mobility Solutions. The interviewees highlighted the potential of autonomous vehicles, electric cars, and expanded public transport systems as crucial elements of future urban mobility. These initiatives align with scenario planning by preparing for technological advancements that address climate change and improve transportation efficiency. Emerging technologies like metaverse applications and augmented reality for remote work signal a shift towards more digital urban experiences, indicating how cities can adapt to uncertainty and leverage innovation in shaping the future.

Adapting to Climate Change. The focus on decarbonizing transport and mitigating the urban heat island effect aligns with scenario planning aimed at making cities more resilient to climate change. The interviewees emphasized sustainable urban planning measures such as increasing green spaces and implementing low-emission zones, underscoring the need for integrated climate adaptation strategies that build urban resilience in the face of the evolving environmental challenges.

Enhanced Public Transport and Non-motorized Mobility. Improving public transport networks and pedestrian/cycling infrastructure to reduce the reliance on private vehicles emerged as a key priority. This approach reflects scenario planning’s emphasis on designing future urban landscapes that prioritize sustainable, inclusive mobility options, addressing both the environmental and accessibility challenges.

Stakeholder Involvement and Collaborative Planning. The interviewees stressed the importance of involving diverse stakeholders in the planning process, echoing the collaborative ethos of scenario planning. Community engagement and inclusive decision making are essential to developing adaptive, participatory urban strategies that reflect the needs and priorities of all residents, ensuring the success of future urban initiatives.

Addressing Socio-Spatial Inequalities. The discussions on the disparities in the transport access and quality of life between the central and peripheral areas highlight the need for a deeper understanding of urban networks and their socioeconomic impacts. Scenario planning provides a framework to explore the outcomes of different spatial development strategies, with the goal of reducing the inequalities and improving the connectivity across metropolitan regions.

6. Concluding Remarks

This research on mobility in metropolitan regions, with a focus on Greater London, offers crucial insights into how various dimensions of mobility are perceived and the key attributes needed for metropolitan sustainability. By analyzing the diverse stakeholder perspectives, the study provides valuable qualitative data on urban governance, socio-spatial structuring, and infrastructure integration. These findings highlight the pivotal role of mobility in shaping the future of metropolitan regions, aligning with broader theories of urban development and sustainability.

The study reveals that socio-spatial structuring plays a crucial role in shaping personal and professional connections to urban spaces. The interviewees noted how infrastructure projects, such as the Elizabeth Line, improve connectivity and collaboration across the boroughs. This underscores the importance of integrated governance and transport systems in promoting socio-spatial equity, ensuring that all communities benefit from sustainable mobility solutions.

In terms of governance dynamics, the complexity of managing Greater London, with its varied administrative practices and autonomous boroughs, emerged as a key theme. The interviewees stressed the need for collaboration between the GLA, TfL, and local boroughs to create cohesive urban planning. Stronger policy coordination and leadership were identified as essential for addressing the infrastructure and mobility disparities across different parts of the city.

Cultural identity and diversity were also highlighted as critical factors in shaping a metropolitan region’s identity. The interviewees emphasized London’s ability to balance its rich historical legacy with modern urban developments. Inclusive urban planning that accommodates diversity not only enhances social cohesion but also fosters economic growth and innovation.

From an economic perspective, the research points to the dual role of mobility in supporting economic concentration while addressing the spatial inequalities. Although London’s position as a global hub attracts talent and resources, it also intensifies the socioeconomic disparities between the central and peripheral areas. The study suggests that balanced investment in infrastructure and mobility, particularly through the sharing economy, is vital for ensuring that the benefits of economic concentration are equitably distributed across the city.

Lastly, the issue of climate change and sustainability is central to building resilient metropolitan regions. The research emphasizes the need to decarbonize transport and promote non-motorized mobility options, such as walking and cycling. These initiatives, coupled with long-term planning and adaptive governance, are crucial for reducing emissions and enhancing urban livability in line with global sustainability goals, such as SDG 11. However, it is important to acknowledge the limitations of this research. While the interviews provided rich qualitative data, they did not offer deeper analyses of the attributes identified by the interviewees. Furthermore, the study has not incorporated quantitative phases that could further elucidate these attributes, either in London or in another case study.

As a future contribution, adapting this research to explore the identified attributes both qualitatively and quantitatively in London or another metropolitan context presents an exciting avenue for further investigation. Such an approach would not only expand the empirical base of this study but also enhance our comparative understanding of metropolitan sustainability across different global contexts, thereby contributing to a more nuanced and comprehensive discourse on urban mobility and sustainability.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, V.d.T.R. and A.C.F.; Methodology, V.d.T.R. and A.C.F.; Software, V.d.T.R. and A.C.F.; Validation, V.d.T.R. and A.C.F.; Formal analysis, V.d.T.R. and A.C.F.; Investigation, V.d.T.R. and A.C.F.; Resources, V.d.T.R. and A.C.F.; Data curation, V.d.T.R. and A.C.F.; Writing—original draft, V.d.T.R. and A.C.F.; Writing—review & editing, V.d.T.R. and A.C.F.; Visualization, V.d.T.R. and A.C.F.; Supervision, V.d.T.R. and A.C.F.; Project administration, V.d.T.R. and A.C.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Brazilian Federal Foundation for Support and Evaluation of Graduate Education–CAPES, processes number PDSE—88881.846533/2023-01.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author due to privacy or ethical restrictions about interviewees names and positions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | The latest IPCC report forecasts temperature increases of 1.5 °C from 2021 to 2040 and 1.6 °C from 2041 to 2060 under the SSP1 scenario, highlighting the critical need to integrate mobility into worldwide sustainability initiatives. Given that automobiles contribute to 80% of greenhouse gas emissions, there is an imperative for systemic shifts towards sustainable transportation alternatives. |

| 2 | According to item CCL, the term “metropolis” in the Metropolis Management Act 1855 indicates the jurisdictional extent of the Metropolitan Board of Works. This encompasses the City of London and its adjacent parishes, marking the area for urban management and the development of essential infrastructure such as roads, sewers, and public utilities. This delineation was critical for the Victorian era governance and the systematic modernization of London’s municipal services and urban configuration. |

| 3 | The Unitary Development Plan (UDP) is built in two parts with strategic policies and land use details, plus a Proposals Map with general uses. The Supplementary Planning Guidance is issued for development control. The boroughs operate under a decentralized system of central government, aligned to the London Strategic Planning Guidance issued every five years. |

References

- UN HABITAT World Cities Report 2020. The Value of Sustainable Urbanization. 2019. Available online: https://unhabitat.org/world-cities-report-2020-the-value-of-sustainable-urbanization (accessed on 8 January 2021).

- UN-DESA. World Population Prospects 2024. 2024. Available online: www.un.org/development/desa/ (accessed on 9 September 2024).

- UN Population Division A Recommendation on the Method to Delineate Cities, Urban and Rural Areas for International Statistical Comparisons. 2020, Volume 3, pp. 1–33. Available online: https://unstats.un.org/unsd/statcom/51st-session/documents/BG-Item3j-Recommendation-E.pdf (accessed on 10 January 2021).

- Dijkstra, L.; Poelman, H.; Veneri, P. The EU-OECD Definition of a Functional Urban Area, OECD Regional Development Working Papers, no. 2019/11; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ITF. The Innovative Mobility Landscape the Case of Mobility as a Service; International Transport Forum Policy Papers; OECD: Paris, France, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]