Abstract

The process of urbanization has brought about a series of negative effects and prompting researchers to critically reflect on the pros and cons of urbanization. In particular, the rapid development of urbanization has posed serious challenges in terms of food and environmental issues. Edible landscapes have been proposed as a means to offset some of the negative impacts, but many of the challenges faced by edible landscapes in the development process have hindered their development. Therefore, how to promote the further development of edible landscapes in cities has become the focus of current research. This paper takes the edible landscape in the San-He community of the Long tan District, Taoyuan City, Taiwan as a case study and uses in-depth interviews and non-participant observation to investigate the strategies of using local brands to solve the challenges of edible landscape development. The study found that the development of edible landscapes in urban communities can bring many social, economic, and cultural benefits to the communities, but the development of edible landscapes also faces challenges such as marketing, government policies, and growing techniques, which can be effectively addressed by place branding strategies. The results of this study can be used as a guide for the development of edible landscapes by local governments, communities, participants in edible landscapes, or similar cultural countries.

1. Introduction

Since the industrial revolution, cities around the world have developed rapidly, which has brought about a wave of global urbanization. In this rapid, continuous, expansion and development, many rural areas close to cities have been gradually incorporated and become suburban areas [1,2]. According to the CIA, Taiwan will have an urbanization rate of 78.9% in 2020 [3]. Benefiting from the dividends of urbanization, many county and rural areas in Taiwan have been gradually transformed into cities. However, these areas, which have been transformed from rural counties to suburban areas, are facing the problem of decline due to serious population exodus and the influence of factors such as aging and childlessness, and especially for the development of traditional agriculture, which is facing a huge crisis [4,5]. Within the process of urbanization, due to the influence of modern urban planning, urban landscape creation has developed a basically regular and ornamental landscape; this has caused the traditional edible crop landscape gradually to disappear in the city. Hence, in many cities, people have a certain demand for these edible crop landscapes, since with the rapid development of urbanization, the urban population has grown dramatically, and urban food security and other issues are increasingly prominent. In addition, with the advent of the third wave of the information age in the late 20th century and the emergence of the experience economy, urban people are particularly eager to experience and consume such food [6,7,8,9]. As a result, an emerging landscape design concept—edible landscapes—was born within the landscape discipline. The concept was first proposed by American environmentalist Robert Kourik and later developed by landscape designer Rosalind. The concept means that edible crops can be planted in urban landscapes through the design of ecological gardens so that urban landscapes can have not only aesthetic value but also food production and consumption value. In short, edible landscapes are landscapes with a combination of ornamental and edible functions. This kind of landscape combines the multi-functional aspects of ornamental, productive, and participatory experiences and is gradually gaining attention [10,11,12,13]. However, despite the numerous benefits of edible landscapes for urban development, it has failed to develop in a large scale in cities. This is mainly due to the many challenges in the development of edible landscapes. For example, Hajzeri and Kwadwo [14], in their study of policy challenges and implementation evaluation of edible landscapes in Berlin, found that the challenge of edible landscapes was the damage caused by incoming animals and children in the community and that there were different conflicts of interest among citizens, communities, and regional administrations that hindered the further development of edible landscapes. In a review of the literature, Lin et al. [15] found that the development of edible landscapes in cities faces difficulties in terms of land availability, environmental constraints, and lack of knowledge about farming, and Sevik et al. [16] pointed out that land contamination is a serious challenge for growing edible landscapes in urban areas. Therefore, an effective approach to solving these challenges is the key to promoting their development.

In recent years, place branding has been favored by governments, city managers, enterprises, and other organizations around the world as an effective tool to promote place building and urban regeneration, and it is widely used in national, city, and place development [17]. From the definition of the specific place branding concept, most scholars believe that place branding mainly refers to the relevant brand-building and brand-equity building carried out by a country, region, city, or place. This construction is mainly a brand awareness building that combines internal and external images, satisfaction and loyalty, and other favorable brand associations [8,18,19]. Related studies point out that the adoption of place branding strategies not only promotes the development of aspects of a place landscape, but also improves the competitiveness of the whole place, mainly because the adoption of place branding can present a positive place image, create a place landscape brand capital, provide added value to the place, enable the greater promotion of the place, and better position the place on a sustainable development path [20,21,22]. Therefore, building a place branding strategy can solve the difficulties and challenges in the development of edible landscapes and promote them further.

Current research on edible landscapes is mainly focused on environmental, cultivation, ecology, and horticulture disciplines. For example, Wan and Meng [23] conducted a systematic literature review of edible landscapes over the past 30 years and found that it has focused on urban agricultural landscapes, ecological landscapes, children’s nature awareness and education, and community gardens. Li et al. [24] found from a systematic literature review of the progress and trends of edible landscapes in China and abroad that a large number of relevant research results have focused on the concept and connotation of “edible landscapes”; landscape creation strategies using edible plants as materials; the application, scope, and mechanisms of edible landscapes; and the process and methods of applying edible landscapes. Currently, there are few studies on the use of building place branding to promote the development of edible landscapes. Therefore, it is necessary to conduct a study of edible landscapes in urban communities using place branding, which is a useful exploration for the development and promotion of edible landscapes and has more important academic significance and reference value. Through this study, we hope to answer the following three questions:

- 1.

- Why is there a shift from productive urban—suburban agricultural landscapes to edible landscapes?

- 2.

- What benefits can the development of edible landscapes bring to suburban communities?

- 3.

- How to solve the challenges in the development of peri-urban edible landscapes?

In the following, this paper will review the research related to edible landscapes and place branding. The methodology of data collection and analysis will be explained, and the process of the development of edible landscapes in the San-He community will be examined. The paper will then analyze the causes, benefits, and challenges of the development of edible landscapes; explore how place branding can be used to address the challenges of the development of edible landscapes; and draw conclusions from the study.

2. Edible Landscapes and Place Branding Literature Review

2.1. Edible Landscapes

After the industrial revolution, with the accelerated urbanization, the population of cities grew rapidly, which to a certain extent caused a shortage of food, including fruits and vegetables, in cities. In the 1980s, American environmentalist Robert Kourik proposed the idea of developing edible landscapes in cities. This concept was later put into practice and developed by landscape architect Rosalind Creasey. According to Creasey’s [25] definition, edible landscaping refers to the planting of edible crops in urban fruit and farm gardens through the design of ecological gardening techniques that make these gardens not only productive but also aesthetically and ecologically valuable. Specifically, it takes the form of community gardens, urban agriculture, food forests, etc. These landscapes have both edible and ornamental functions; and therefore, we can use the macro name “edible landscapes” to cover the above-related concepts.

As edible landscapes are gradually being introduced into various urban landscape designs, there is a growing body of research evidence that the development of edible landscapes has significant benefits for urban communities. For example, Delormier and Marquis [26] conducted a study of edible landscapes in the Native American community of Kahnawake, New York, and showed that the creation of edible landscapes in the community not only brought mutual interaction but also provided adequate food for the community residents. Kortright and Wakefield [27] showed in a Toronto community study that the development of edible landscapes in urban communities not only beautifies the community landscape, but also provides a variety of foods such as vegetables and fruits for the residents of the community, and even provides a place for the residents to interact and create a space for healing and nature education [28,29,30,31,32].

However, while the development of edible landscapes has many benefits for urban communities, there are many barriers to the development of edible landscapes, the main ones being the following: First, the source of land and land use regulations for edible landscapes. Some researchers have pointed out that in urban areas, there is limited space available for growing food, and there may be competing demands for land use. In addition, many cities have regulations that restrict or prohibit the growing of food in certain areas, which can seriously hinder the development of edible landscapes [15,33]. Second, people’s awareness of edible landscapes is insufficient and their concepts are different. Indeed, Xie et al. [34] noted in their study of edible landscapes in urban communities that nearly one-third of residents did not know what edible landscapes were. Further, Conway’s study of urban residents’ motivations for growing edible landscapes [35] noted that their knowledge of edible landscapes was incomplete, and their motivation for growing them was mainly the food vegetables and recreational pastimes that edible landscapes could bring. There are also some people who do not consider it appropriate to grow food in public places or are not interested in participating in community gardening activities [36]. Third is the challenge of edible landscaping maintenance, management, and growing techniques. Since edible planting requires regular maintenance and management, failure to provide them can lead to problems such as pests and sub-optimal food production. In addition, growing edible plants requires participants to have certain growing skills which many citizens, along with landscape architects, may no longer have [14,37]. Of course, in addition to these impediments, there are many other factors that constrain the further development of edible landscapes. Therefore, effective approaches to address these factors hindering the development of edible landscapes are key to the further development of edible landscapes in cities in the future.

2.2. Place Brand

Place branding has been widely used in recent years by various countries, cities, and local governments as an effective tool for place development. This linking of marketing methods with local characteristics to enable place development allows the image and characteristics of a city to be promoted quickly and more effectively [38]. The origin of place branding comes mainly from the marketing discipline, and its concept is based on the idea of “place marketing” proposed by Philip Kotler, an American marketer, in which the place can be considered as a business and the future development of the place can be considered as a product, in which the place can be specifically analyzed. In this context, the local environment can be specifically analyzed to identify the strengths and weaknesses, as well as the opportunities and challenges faced by localities in global competitiveness. Then, according to the marketing needs of the target market, a series of creative and packaging marketing activities for the place can be carried out, which will improve the development of the place. Therefore, the essence of place branding is to apply marketing to a more specific product, that is, the place [39]. The so-called “place” here is actually the geographical space where the brand is implemented and created, which can be an industry or a national administrative area such as provinces, cities, counties, and towns [40,41]. Therefore, the core of a place brand is the concept of “place”, which is not only the result of place manufacturing but also the result of place creation [42]. The development of place branding is mainly due to the recent development of the capitalist commercial and scientific and technological revolutions, especially the emergence of the experience economy in the late 20th century with the advent of the third wave of the information age, which overturned the previous concept of consumption [8]. The experience economy is very different from the previous concept of consumption. Experience consumption places greater emphasis on the value of experience in the process of consumption, rather than just the simple exchange between goods and services [18]. Therefore, in the age of information technology, brand, media, identity, and image become the core content of the global experience economy. The essence of creating a place brand is to create a brand with a “sense of place” by linking place identity with images through the projection of profound place experiences and place images [8]. The aim is to attract more audiences to come and spend and experience the place, which will lead to place investment and development and make the place better, thus bringing more benefits to the place.

As an emerging sustainable development concept, studies have found that the development of edible landscapes is very beneficial to local development. For example, Robinson et al. [43] found that the development of edible landscapes in the Phoenix area has significant economic benefits and is very conducive to the economic development of the area. Lafontaine-Messier [44] found that the development of edible landscapes in the southern part of Lima, Peru, could increase the economic income of the local municipality, reduce financial support, and also bring economic benefits to local producers and promote local economic development. However, there are many challenges in the development of edible landscapes. Therefore, how to solve these challenges is the key to promoting the development of edible landscapes. There is a growing body of research evidence that the adoption of place branding strategies can contribute to the development of place landscapes. For example, Maheshwari et al. [45] showed that “place branding in Liverpool plays an important role in sustainable place development. It not only promotes place development but creates a strong place brand that enables places to continue to be sustainable”. Chan and Marafa [46] propose a place branding framework for “green resources” through a study of parks and green spaces in Hong Kong, showing that landscape is another dimension of place sustainability that can be used for place branding to make a city’s development more sustainable. Vela et al. [47] used place branding strategies to build support for what they called “landscape branding”, the typical role of landscape in place branding, revealing the importance of experience in landscape branding and finding that a well-constructed landscape brand through a place helps to retain talent and attract people to visit the place thereby promoting development. Therefore, place branding plays a very important role in shaping the place landscape [19]. In view of this, adopting place branding strategies to address the current challenges encountered in the development of edible landscapes and to promote their development has many potential advantages.

3. Methods

3.1. The Study Area

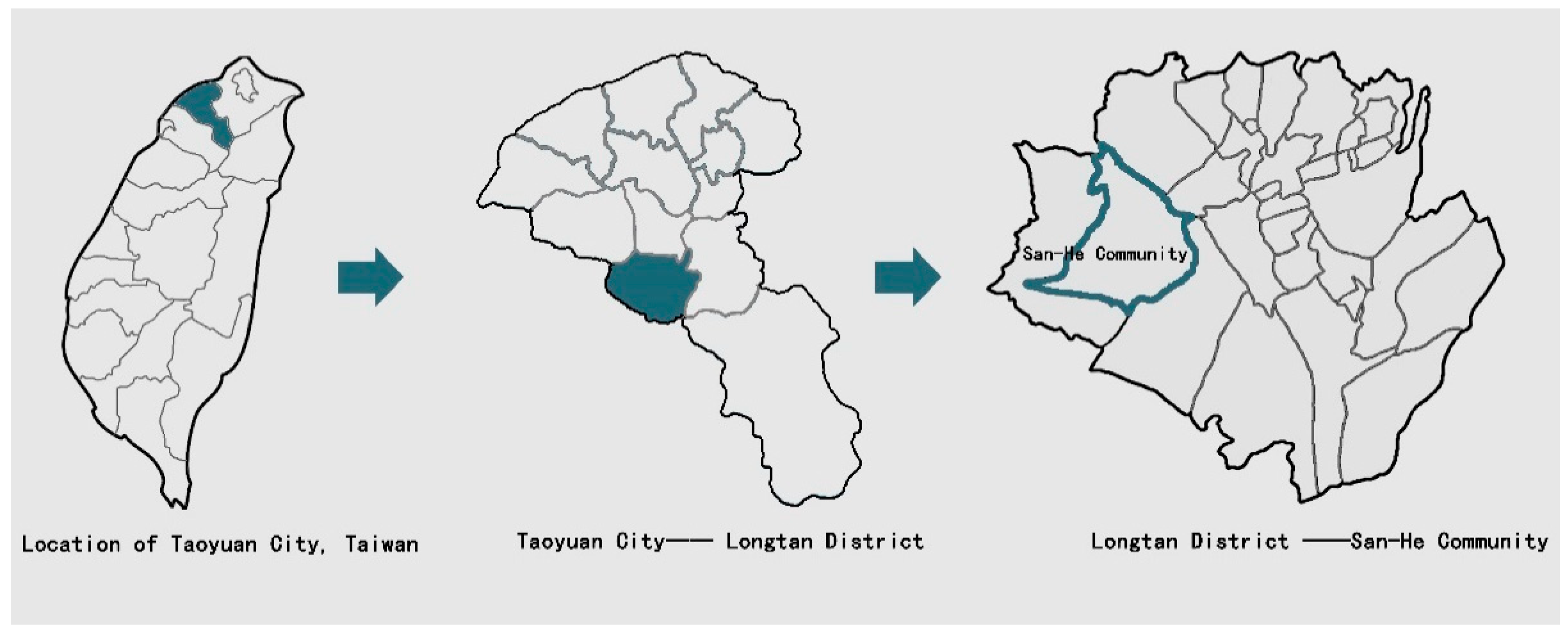

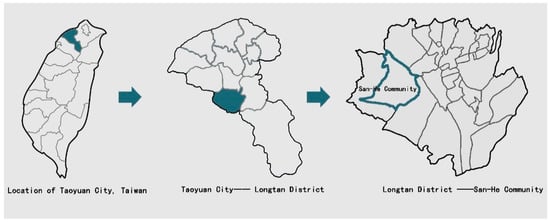

The case for this study, the San-He community, is located in the west of Longtan District, Taoyuan City, Taiwan (see Figure 1 for details). San-He community has a population of about 1000 people and a total community area of about 6.4 km2 The community’s name was San qia shui during the Guang xu period of the Qing Dynasty. After Taiwan’s restoration, then, due to the government’s re-governance, San qia shui was divided into two villages, San he and San shui [48]. Later, on 25 December 2014, due to the elevation of Taoyuan County to a municipality directly under the Central Government of Taiwan, Longtan Township was reorganized into Longtan District, and San qia shui was also reorganized into San-He community [49].

Figure 1.

San-He community Location Index Map.

This case study of the San-He community is mainly based on the following considerations:

- (1)

- Taiwan’s Longtan San-He community is among the first batch of communities in Taiwan to be evaluated for environmental education and is a model for community regeneration in Taiwan. Therefore, the case study is representative and typical;

- (2)

- Taiwan Longtan San-He community is known for its beautiful natural environment and abundant edible crops, especially for its tea garden scenery, which is the location for the filming of the tea advertisement for Taiwan’s unified enterprise King Tea Lane. Therefore, it attracts many government personnel, scholars, enterprises, and tourists to visit the place every year;

- (3)

- This case was a rural area in the county before Taoyuan was upgraded to a municipality in Taiwan in 2014, as was Taoyuan County. Therefore, the study of this case is useful for understanding the transformation of rural productive agricultural landscapes to urban edible landscapes during the urbanization of rural counties in Taiwan.

3.2. Data Collection

This study was conducted from August 2022 to March 2023. Data were mainly obtained from in-depth interviews, non-participant observations, and field surveys to ensure the triangulation of data sources to enhance the credibility and rigor of the study results. In-depth interviews were used mainly because they are an important method in qualitative research in which the researcher can collect first-hand data from the respondents by means of seeking and interviewing them, which is useful for gaining insights into the background to events. In research sample sampling, qualitative case studies require detailed and in-depth first-hand interview data. Therefore, the quality of the sample rather than the quantity of the sample is more important in sample sampling. Therefore, purposive sampling, which is a non-probability sampling method, is mostly used in research sample sampling, that is, the research sample that can best provide the most information to the research questions according to the purpose of the study [50,51,52]. Non-participant observation is used mainly because the researcher can stand as a bystander in an objective and neutral position to understand the dynamics of what is happening in the study as it develops [50,53]. In order to increase the credibility and rigor of the research findings, the selected respondents have characteristics that are relevant to the research topic [54]. Therefore, in-depth interviews were conducted using purposive sampling as a way of ensuring the diversity of the interviewees’ backgrounds.

The main reason for selecting these groups as interviewees is that some of them are directly involved in the development of edible landscapes; some of them have been living in the community for a long time and are familiar with the development process of edible landscapes. Some of these groups are experienced beneficiaries of edible landscapes, and they have a deep understanding of the development of edible landscapes. Here, the interview subjects were qualified by the following criteria for interview inclusion: (1) growers of edible landscapes in the community; (2) community managers; (3) long-term residents of this community; (4) neighborhood residents; (5) tourists; and (6) community restaurant operators. The interviewees included five original community edible landscaping growers (IV1, IV2, IV3, IV4, IV5), two community managers (IV6, IV7), four community residents (IV8, IV9, IV10, IV11), one nearby resident (IV12), one visitor (IV13), and one community restaurant operator (IV14), (for details, see Table 1). To protect the privacy and anonymity of each interviewee, the interviews were coded individually for specific respondents. The in-depth interviews were conducted in a semi-structured manner, and all respondents were asked three core open-ended questions (see below), which were used to trigger an in-depth exploration through the follow-up questions.

Table 1.

List of interviewees.

- 1.

- What is the current status of the development of community edible landscapes?

- 2.

- What are the difficulties encountered in the development process of community edible landscapes?

- 3.

- How is the community edible landscape operated and promoted, and what are the difficulties and challenges encountered in the operation and promotion?

To ensure saturation of data collection, one-to-one in-depth interviews took place until similar comments began to recur in the answers of each interviewee and no new themes emerged and no new codes were required [55,56]. Interviews were recorded using a numerical approach for later transcription, line-by-line coding, and analysis. In terms of data analysis, this study used thematic analysis to enable a detailed understanding of the interview data. Defined as “a method for identifying, analyzing, and reporting patterns in data” [57], thematic analysis is a flexible and useful method of qualitative analysis [58] and is used in qualitative research to provide a rich and detailed account of the themes in the data. The analysis revealed many interesting findings from this process, such as “tea garden scenery”, “Hakka culture”, and “environmental education”. However, this paper will focus on three themes related to the research topic: (1) the current status of edible landscape development, (2) the challenges of edible landscape development, and (3) the benefits of edible landscape development.

The fieldwork aspect of the field survey included active observation, nature conversations, field notes, drawings, and photographs, combined with non-participant observation of the development of edible landscapes in the San-He community. During the study period, the researcher observed through non-participatory observation, the daily activities of residents and visitors, such as picking, selling, and planting; this helped to understand the development of edible landscapes throughout the community. It is important for the researcher to maintain critical self-reflection so as not to compromise the fieldwork and information. The findings of the study concerned (1) The process of edible landscape development, (2) The emerging system of edible landscape development, and (3) The challenges of edible landscape development.

4. Results

4.1. San-He Community Edible Landscapes Development Process

The San-He community is located in a hilly area in the suburbs of Taoyuan City, Taiwan. The community is a Taiwanese Hakka settlement, and the main culture of the community is the traditional Chinese Hakka culture. The community currently has a total population of about one thousand people. The community has been established for more than thirty years, and the original environment has been well maintained because the community has not been developed extensively during the urbanization process in Taiwan. The community’s overall natural environment is beautiful and rich in flora and fauna, and it was named one of the first environmental education communities in Taiwan.

For example, community managers IV6 said:

“Our community has been established for more than 10 years, before [there were] two rural villages our village is San he village, the next village is San shui village, later because Taoyuan was upgraded to a municipality in 2014, our village [was] also restructured [and] called San-He community. The agricultural products planted here before are mainly rice, green vegetables, corn, etc. In the following years, about after 2015, many tourists from Taipei, Hsinchu, Yangmei and Taoyuan [would come] here on holidays or weekends to play, sightsee, pick, and experience our agricultural products, so our side began to gradually develop [an] ornamental food experience, picking-based agricultural products, such as tea, dragon fruit, strawberry, sugar orange, etc. But since the land is privately owned by the residents, they are developing it on their own, and our community organizations basically do not participate in their development, but only occasionally stand to help them in their development…”(IV6)

Before Taoyuan was upgraded to a municipality directly under the Central Government of Taiwan in 2014, it was a suburban area with a productive agricultural landscape, and the agricultural products grown there were mainly for farmers’ own consumption. A fundamental shift has occurred in the development of the agricultural landscape from the original productive rural agricultural landscape to the development of an edible landscape offering tourists the experience of picking the produce.

For example, respondent community manager IV7 stated in the interview that:

“Our side in the early days…mainly planted some rice, vegetables, citrus, guava agricultural products, because the agricultural products themselves are not very profitable, it slowly withered away. Later, because Taoyuan County was promoted to the municipality of Taiwan, people from the city liked to come over to our side on holiday weekends to experience sightseeing, picking, and environmental education of edible crops in the past few years, and the development of agricultural production planting over here slowly began to shift to the development of sightseeing and picking types…”(IV7)

Interviewee IV8, a resident of the community, said in the interview:

“Before Taoyuan became a municipality, there were not many tourists coming here, and it was basically a rural area. There, more tourists came. Tourists come to our side mainly to see the scenery of our community’s fields, and then experience picking some of the agricultural products here, and cook the picked vegetables here…”(IV8)

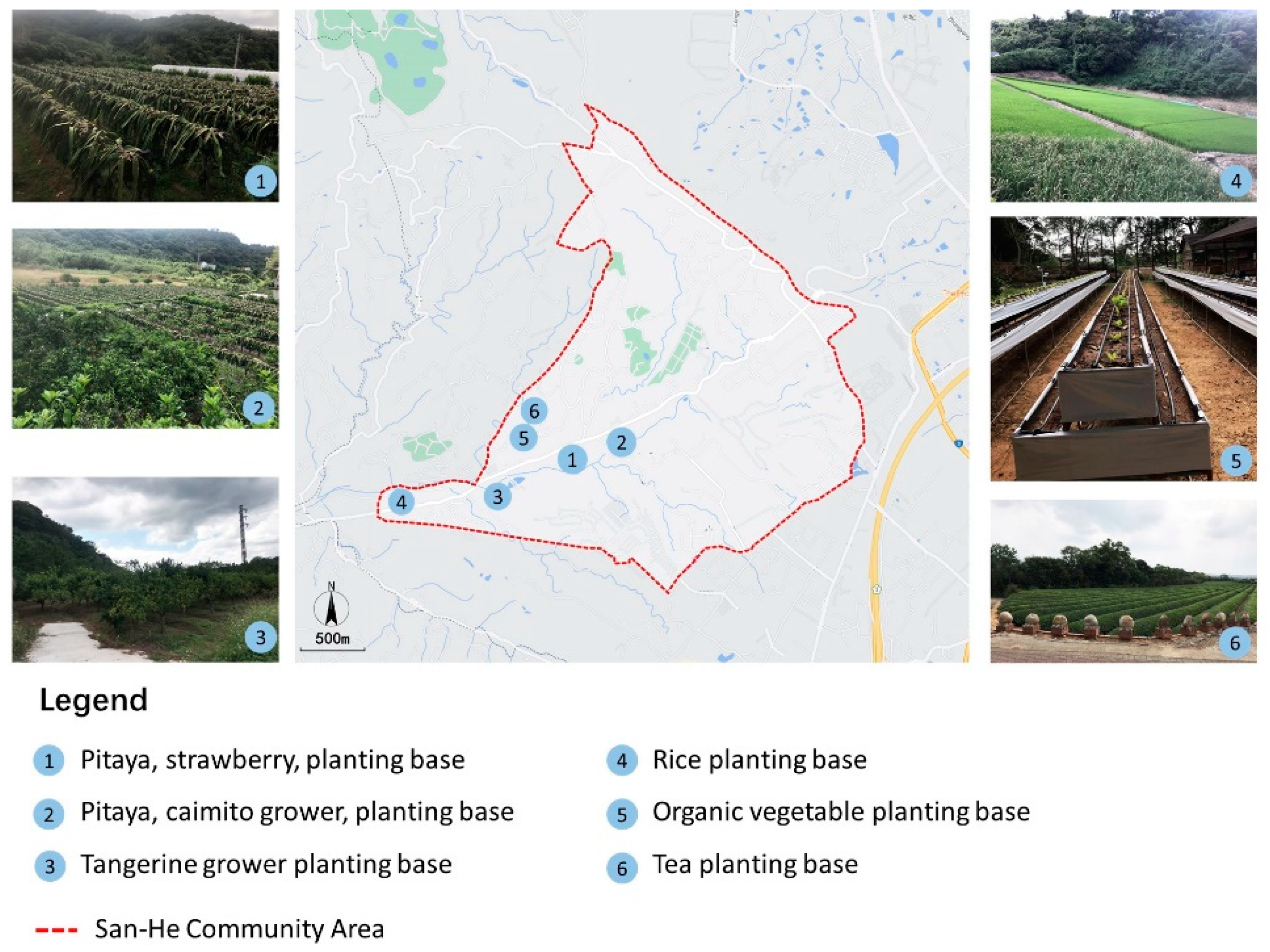

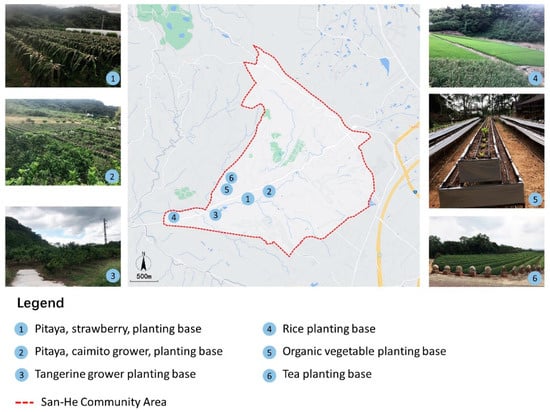

Currently, the edible landscapes in the San-He community mainly contain crops such as rice, tea, pitaya, strawberry, tangerine, organic vegetables, caimito, pumpkin, and winter melon (Figure 2), individually planted on private land rather than public community land. Consequently, these edible landscapes are owned by individuals without the involvement of community residents, the place government, community organizations, and place businesses.

Figure 2.

Distribution of edible landscape planting in the San-He community.

Edible Landscape grower IV3 said:

“The crops we plant are mainly tea, pitaya, oranges, organic vegetables, etc. Planting is by ourselves’ personal ideas, because these lands are all our own private lands, so planting relies on our own management and maintenance, the (other) residents of the community basically will not participate in our planting.”

These edible landscaping growers mostly use sustainable growing techniques, such as using sets and mowers to reduce the use of pesticides and using natural green manure and enzymes as fertilizers, such as collecting fallen fruits, fruit peels, and food scraps to make edible landscaping fertilizer.

Community manager IV7 said:

“They are now using organic farming methods, which means reducing the use of pesticides and chemical fertilizers and using enzymes to make fertilizers for farming, and most of the farming over here is now using this sustainable farming technique.”

Also, edible landscape growers IV1, IV2, IV4 said:

“We are using friendly and non-toxic farming techniques, for example, we will plant Lupin flowers in front of tea trees because they are a natural green manure fertilizer, so we will plant Lupin flowers in front of tea trees every year, which can be used for ornamental purposes and as a free and non-toxic natural fertilizer.”(IV1)

“Most of us will use enzymes to make fertilizer, which is to make enzymes from fallen fruits, eggshells, soybeans, fruit peels, vegetable leaves, etc. The fertilizer made in this way contains various trace elements and microorganisms, which can be used to fertilize, stimulate, or decompose the soil.”(IV2)

“We don’t use herbicides for weeding, because using herbicides has an effect on other plants too, we carry mowers for weeding.”(IV4)

Through the above in-depth interviews with community leaders, residents, and edible landscape growers, it is clear that the landscape of the San-He community has undergone a transformation from a productive agricultural landscape to an ornamental edible landscape. The fruits were not very profitable so they gradually died out. But after 2014, as Taoyuan County was upgraded to a municipality directly under the central government, with the continuous development of urbanization, people in the city began to have a gradual demand for idyllic scenery and agricultural picking experience. As a result, edible landscapes for sightseeing and picking experiences began to develop here, and the development of edible landscapes began to flourish, especially after the COVID-19 epidemic, because of the limited space for urban activities.

4.2. The Emerging System of Edible Landscape Development in San-He Community

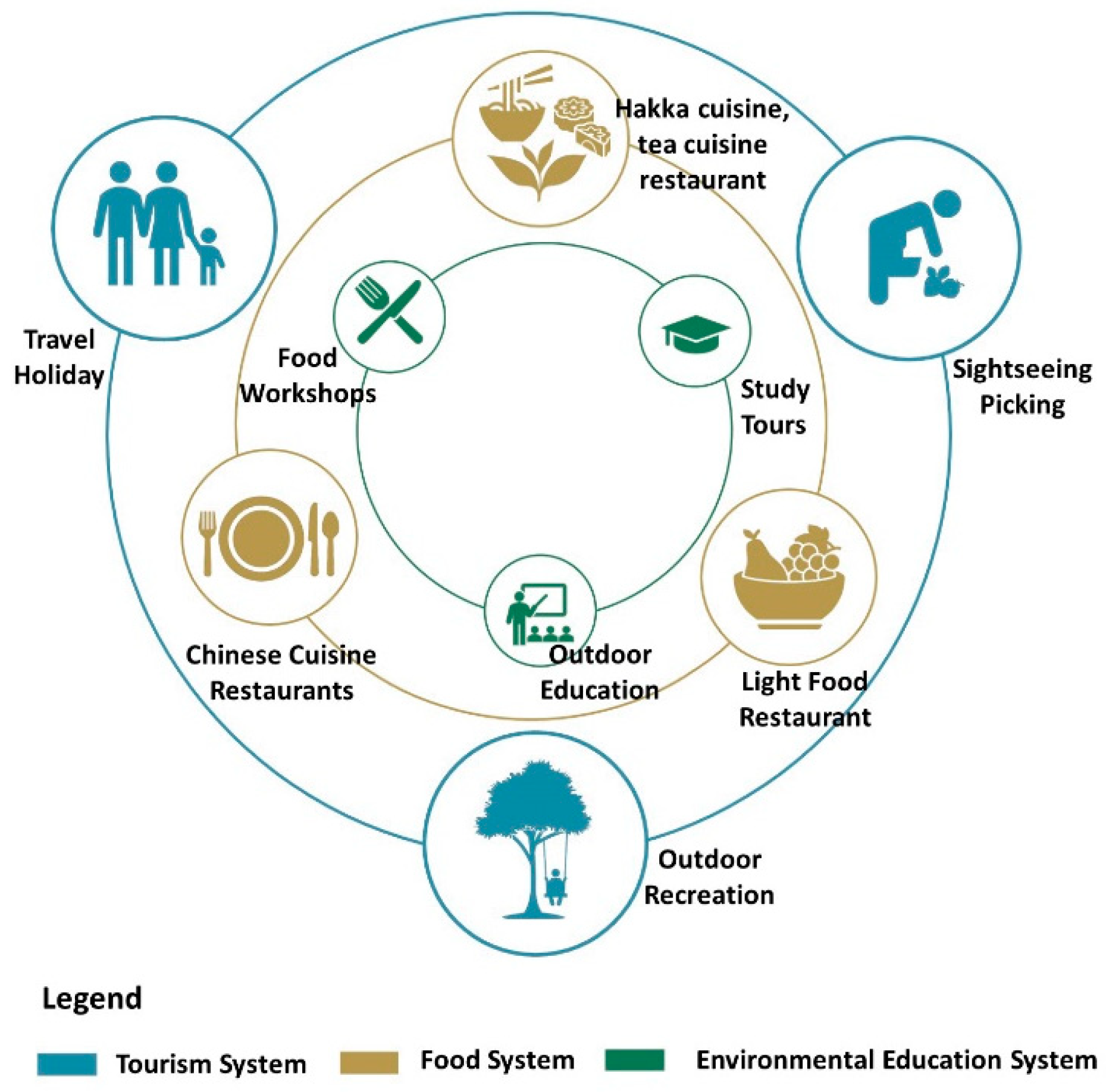

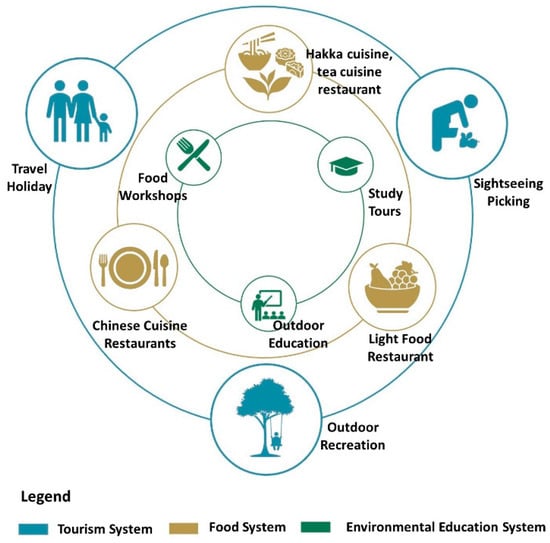

Through fieldwork and non-participant observation of the San-He community, it is found that the following three systems are being developed as edible landscapes (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Three systems that are being formed by the development of edible landscape in the San-He Community.

First, the tourism system formed by the gradual development of edible landscapes mainly includes outdoor recreation, vacation tourism and sightseeing, and harvesting. Due to the development of edible landscapes, the San-He community has gradually become a tourist destination. The community has planted a large number of tea plants, making the tea garden scenery an important attraction for foreign tourists, especially those engaged in vacation tourism.

Tourist IV13 said:

“I come here mainly because the tea garden on the hill has a beautiful view, and it has a Heyao Cultural and Creative Park above it where you can do DIY pottery making and baking bread, etc., so usually I will come over to have a rest and watch.”

Because of the rich variety of fruits planted in the community, sightseeing and picking are gradually emerging and many city visitors visit on weekends and holidays for these activities and to experience the pleasure of farming. In addition, with the development of edible landscapes, other leisure and entertainment industries have also emerged, such as leisure fishing, baking bread, kiln-fired pottery, succulent plants, and other leisure and entertainment projects which give people the opportunity to spend time outdoors.

IV7, the President of the Community Development Association, said:

“The orchards are open to visitors for picking. Visitors can come and do some experiential things, and then our community holds annual flower viewing and performance events such as the Tung Blossom Festival and the Lupinus Festival; so many visitors come to visit and watch.”

Community resident, IV10, interviewed on his way to bring a friend over for a trip, said:

“Our area is famous for its tea gardens, such as the tea commercials for the Chai Li Won Taiwanese style green tea drink, which were filmed here, and many TV dramas were filmed here. In addition, this side also gets a wood-fired kiln.so many artists and enthusiasts will gather here to carry out some related literary activities.”

Another community resident, IV8, said:

“Tourists come over here mainly because of the COVID-19 epidemic, because during the epidemic many people want to run to the outskirts. Our community happens to be on the outskirts of the city, so a lot of people come this way.”

Second, the food system gradually developed from edible landscapes. The San-He community is mainly a traditional Hakka community, and the edible landscape crops grown are mainly tea, fruits, and vegetables. To meet the needs of tourists, three restaurants have been opened in the community, including the “Family-Fortune” Hakka Restaurant, which focuses on Place Hakka and tea cuisine; the “Matsuba-Garden” Restaurant, which serves Chinese cuisine; and the “Three-Steps-Five-Food” Restaurant, which serves light meals of fruits and vegetables provided by the edible landscape of the community. Thus, with the development of the edible landscape, the San-He community has developed a unique food system that not only provides healthy and nutritious food for local residents but also provides local specialties for foreign visitors. Interviewee IV14, the owner of the Family-Fortune Hakka Restaurant, said the main features of his restaurant’s operation are:

“We mainly operate a traditional Hakka-style restaurant, and we often use some seasonal vegetables grown in the community to make one of our restaurant’s craft specialties. Tea is a special agricultural product of our community, so we will use tea and catering to attract foreign tourists and let them know about our Hakka food.”

Third, the environmental education system is formed by the development of edible landscapes. On the one hand, the San-He community has not been developed on a large scale during the urbanization process, so the overall environment of the community is kept more natural and simple.

For example, community manager IV6 said:

“Our community environment is kept relatively simple and natural resources are not destroyed, so we are one of the first environmental education communities to be adopted as a community-based name.”

On the other hand, the development of edible landscapes has made the entire community richer in flora and fauna which has enabled San-He to become one of the first batch of leading communities in Taiwan to be named as an environmental education base. Thus, the San-He community has become a base for outdoor ecological education, edible landscaping study visits, and food workshops which have attracted many government agencies, social groups, schools, tourists, and other people to visit and learn.

Edible Landscapes grower IV5 said with happiness:

“Since San-He Elementary School is just across the street from our Orangery, we often invite [the children] to come [and] participate in some experiential or learning activities about the environment.”

Community resident IV8 said:

“We often have government organizations or schools come here to conduct studies in this tea garden.”

From the above interviews, we can see that the current edible landscape development in the San-He community has led to three activity systems: tourism, food, and environmental education which have increased San-He’s visibility and driven its development.

4.3. Edible Landscape Development Challenges in San-He Community

At present, the development of edible landscapes in the San-He community is becoming more and more abundant. However, there are some challenges in the development. These challenges are summarized as challenges in marketing and promotion, challenges in government policies, and challenges in planting techniques. For example, in the area of marketing and promotion of edible landscapes:

Most of the edible landscape growers are older people, so they have limited knowledge of how to use modern networks for marketing, and their means of marketing promotion is basically by personal introduction or telephone and other more traditional ways. Therefore, marketing promotion has become a serious problem for most growers.

For example, community manager IV6 said:

“Marketing is mainly by word-of-mouth, commonly by acquaintances, and there are no special marketing programs, so our marketing is very passive.”

Edible landscape growers IV3 and IV5 said:

“Our biggest difficulty is the marketing and promotion problem, we are old and can’t keep up with the times, commonly only the old traditional kind of sales method.”(IV3)

“Our marketing approach is mainly fruit picking, and we usually call friends and family to come. I need to call them a week or two before the fruit picking to spread the information and let them know that we are going to open here.”(IV5)

The challenge in terms of government policies is that many government policies are in conflict with the development of edible landscapes, and this has seriously hindered the development of edible landscapes.

For example, interviewee edible landscapes grower IV4 clearly complained in the interview saying:

“I think that the government’s land policy is too restrictive in terms of the use of land. For example, agricultural land can only be used for farming and not for other purposes, but sometimes you have to build a greenhouse or a resource room or something like that, but you can’t. So I think the government’s laws and policies are out-of-date and I think the government is blocking us from doing things.”

Moreover, the government has set many conditions offering financial subsidies and technical guidance; however, the application process is extremely cumbersome, which makes edible landscape growers complain:

“The amount of our crops is relatively small, the place government has regulations that you can only join these crop classes held by the government after reaching a certain scale, and then the government will give you financial subsidies.”(IV2)

“To get those subsidies from the government, the whole procedure is very complicated. First, you have to write a good proposal, then you have to go to the review, and after the review and approval of the funds, the government has to conduct [a] mid-term review and final review. So for me, if I have the time to do all these complicated grant procedures, I’d rather be busy with my own business.”(IV4)

With the more serious loss of the youth population in the community, there are difficulties and challenges in the inheritance of planting techniques. This is mainly from those young growers, because they do not have as much experience as the older growers, so they face certain difficulties and challenges in planting techniques. Edible landscapes grower IV4 said:

“For us a lot of planting techniques are not understood. For example, when we first planted oranges in the first year…we almost killed all those orange trees, but fortunately we went to consult our predecessors who planted citrus later to solve the problem. “

From the above results, it is clear that there are currently certain challenges in the development of edible landscapes in the San-He community including government policy constraints, difficulties in marketing and promotion, and planting technology challenges. How these difficulties and challenges can be solved becomes the key to the development of edible landscaping in the San-He community.

5. Discussion: How to Promote Edible Landscapes through Place Branding

This article takes the edible landscape in the San-He community as an example and aims to explore how to further promote the development of edible landscapes in the suburbs of the city. The research results show that the development of an edible landscape in the San-He community has many benefits to the community. The development of edible landscaping in San-He community not only protects the natural ecological environment of the community but also enriches its ecological diversity. From a social perspective, the development of edible landscapes in the San-He community demonstrates the promotion of community solidarity, community cohesion, and place revitalization. it also enriches the development of community social capital to some extent. From an economic point of view, the development of edible landscapes not only increases the income of community residents, but also promotes the economic development of the community, and to some extent, promotes the return of young people in the community and improves its resilience. All-in-all, with the development of its edible landscape, the San-He community has become a resilient community involving tourism, environmental education, an ecological landscape, and community cohesion.

In the San-He community, today’s edible landscape represents a different kind of productive rural landscape than before. It is the result of the transformation from a single productive rural landscape to a multifunctional edible landscape with sightseeing, production, and experience in the city during the process of urbanization. The fundamental reason behind this transformation is that, first of all, urban residents’ demand for natural idyllic and biophilic landscapes has driven the development of peri-urban edible landscapes. As an evolved species in nature, human beings are innately biophilic [34,59,60]. However, in the process of urbanization, modern urban landscape creation has largely separated urban and rural landscape creation from each other, which makes it difficult to see edible crops in urban landscapes. Therefore, as urbanization continues to grow, the demand for edible crop landscapes in cities becomes stronger and stronger. Secondly, influenced by the modern growth of the experience economy, greater emphasis is placed on people co-creating experience consumption within the process of consumption, which makes it essentially different from the past where consumption was just a simple exchange between goods and services. Today, there is a greater emphasis on people’s personal experience in consumption, thus triggering the demand for edible crop picking [8,61]. Furthermore, the most important point is that the benefits of edible landscape development far exceed the benefits of traditional agricultural production. As Robinson et al. [43] showed in their study, multifunctional edible landscapes have the potential for high returns on creation and investment. There are even economic benefits for urban municipalities, mainly in terms of reduced municipal expenditure on greenery maintenance and management [44].

Of course, the development of edible landscapes has many functions, roles, and benefits in addition to the great economic benefits. This study found that there are multiple social, economic, and cultural functions that bring the benefits of edible landscape development to the San-He community. This is mainly due to the three systems of tourism, food, and environmental education created by edible landscape development. This is consistent with the findings of [29,30,32] He and Zhu, Lu et al., and Wei and Jones, who found that developing edible landscapes in communities could enrich the social capital of communities, reduce residents’ expenses, and increase the biodiversity of communities. This study differs in that it found that the development of edible landscapes also promotes the development of community tourism, which not only increases the visibility of the community but also brings significant economic benefits. This is mainly due to the rise of the modern experience economy, which, unlike the traditional agricultural economy, places more emphasis on human consumption satisfaction [62]. This has allowed the development of edible landscapes with numerous projects for experiential consumption such as picking, planting, and DIY so that people can have a deep experience of the edible landscapes in their communities. The study also found that the development of food systems featuring edible landscapes has contributed to the development and transmission of Hakka food culture, allowing more people to develop their sense of regional cultural identity and connect to local networks. As Wu et al. [63] pointed out in their study, through the design of edible landscapes, economies can reconnect to place networks. Thus, tourism harvesting, specialty foods, and environmental education resulting from the development of edible landscapes have become important factors in attracting outside visitors to the community, which has directly contributed to the development of various aspects of the community’s economy, culture, and education, as well as encouraging the return of the departing young people and thereby revitalizing the community. Further, during the COVID-19 epidemic, the San-He Community Edible Landscape provided a buffer vegetable supply chain for city residents. It also provided the best place for urban residents to relax, release stress, and get in touch with nature, offering people a natural healing place. This echoes the studies of He et al. [28], Lu et al. [30], and Nasir et al. [31]. Thus, the development of edible landscapes provides new ideas for sustainable community development in the post-epidemic era in cities and is conducive to further integration of landscape and nature, urban and suburban, and aesthetic and edible [28,64]. Therefore, this study shows that the development of edible landscapes can not only bring healthy food and great economic benefits to communities, but also promote community revitalization, invigorate community culture, and enhance community resilience.

As in similar related studies, this study found many challenges in the development of edible landscapes. The main challenges are mainly from government policy constraints and growing technology challenges, which echo the studies of Lin et al. [15], McClintock et al. [33], Conway [35], Hajzeri and Kwadwo [14], and Wang [37]; however, in addition to these dilemmas and challenges, this study found that there are certain challenges in the marketing of edible landscapes. In addition, this study found that since land in communities in Taiwan is generally privately held, basically there is no public land. Therefore, the development of edible landscapes in San-He communities has autonomous characteristics, and the development of edible landscapes is not constrained by government land policies, which differs from related studies such as He and Zhu [29] and Wekerle and Classens [65] in that there are no public land disputes in the development of edible landscapes in Taiwanese communities, which also indicates that the development of edible landscapes is site-specific, so the generalizability and replicability of the findings of the case studies on edible landscapes cannot be fully applied to the study of edible landscapes elsewhere.

In response to the above challenges in the development of edible landscapes, the adoption of place branding can overcome them and become a useful tool to promote the further development of edible landscapes. First, in terms of government policy challenges, the adoption of place branding can help create a positive image of edible landscapes in the minds of government policymakers and the public. According to Zenker and Beckmann [66], place branding involves creating a positive image of a place by highlighting its unique characteristics and attributes. Moreover, place communication with the main goal of place image development tasks is the most attractive to tourists, mainly because tourists’ choice of destination depends on creating a good place image [67,68]. Therefore, by making edible “placescapes” a unique and desirable place brand, government policymakers may be more inclined to support policies that promote their development and may address the policy constraints noted above. In addition, the use of social media and other marketing channels for place branding can be very helpful in raising awareness and support for edible landscapes, and ultimately influencing government policy decisions.

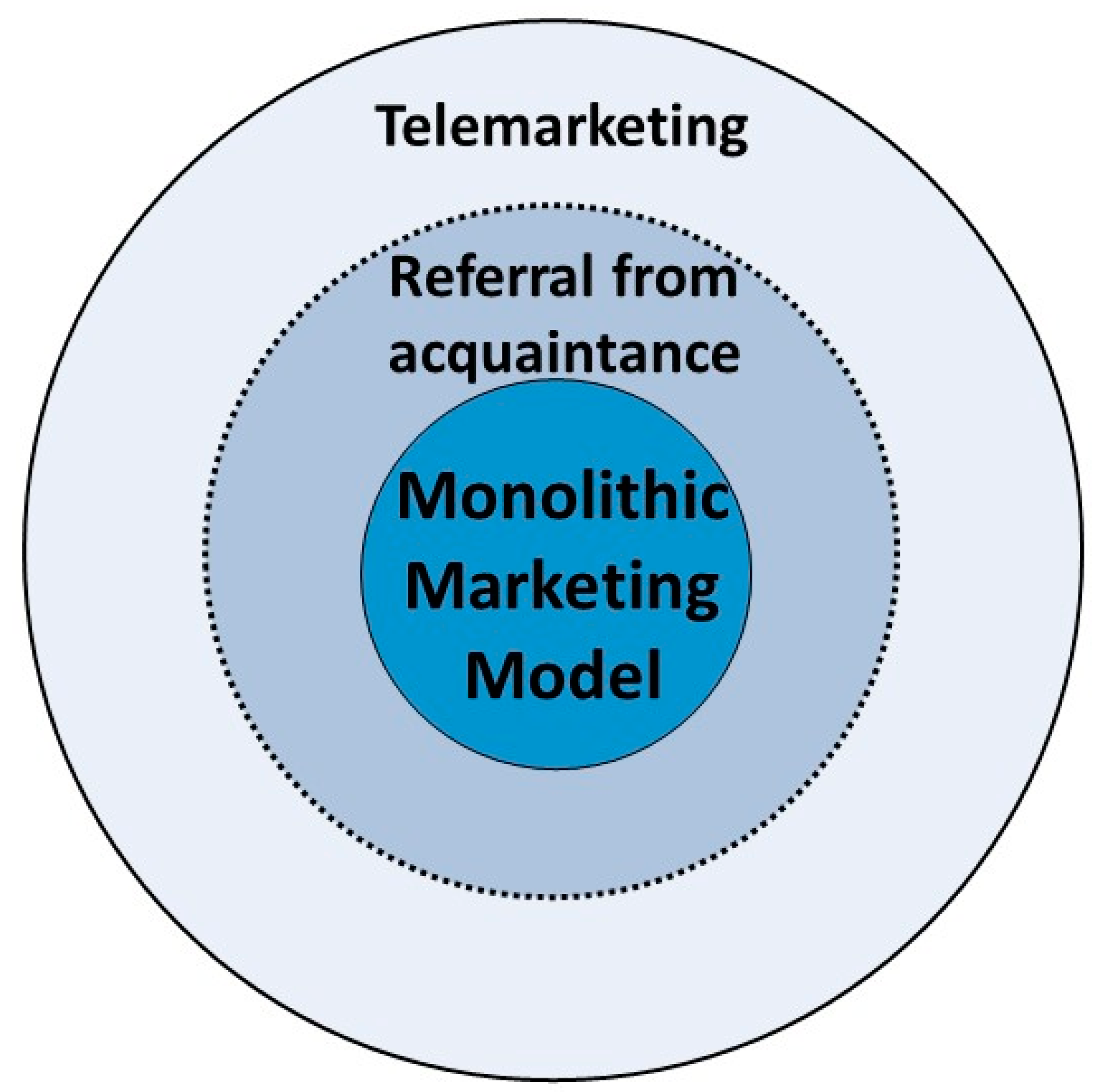

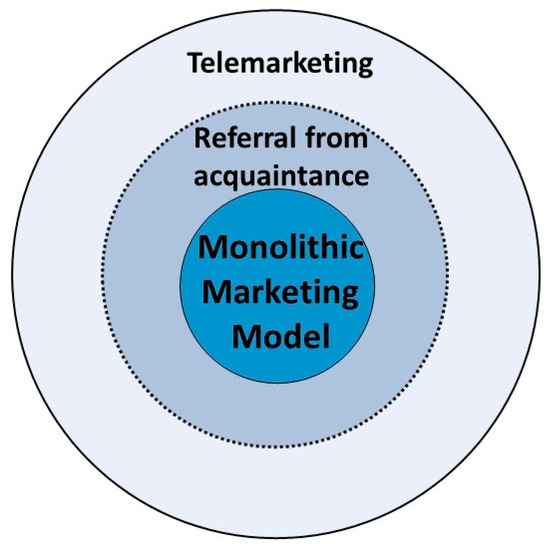

Secondly, how to effectively address the challenges of marketing edible landscapes is critical to their development. This is mainly because the lack of marketing and promotion of edible landscapes will inevitably lead to a decrease in the production of locally grown food crops, thus affecting the further development of edible landscapes. Therefore, effective marketing strategies must be developed to showcase the benefits of locally grown food and edible landscapes. Through place branding, a unique and attractive brand identity can be created for edible landscapes. As Hanna and Rowley [69] point out in their study, place branding helps create a unique identity for a place and can be used to differentiate it from other places and promote its unique characteristics. By developing a brand identity for edible landscapes, marketers can effectively communicate the benefits of locally grown food and promote edible landscapes. In addition, the use of social media, place events, and community outreach programs can help raise public awareness and generate a demand for locally grown foods. However, the current marketing and promotion of edible landscape products in the San-He community are specifically based on traditional marketing and promotion methods, relying mainly on acquaintances, telemarketing, and a small amount of internet marketing (see Figure 4 for details). This creates huge challenges in the development and promotion of an edible landscape. Therefore, the adoption of appropriate marketing and promotion methods is the core of promoting the development of an edible landscape The researcher believes that this can be done in two ways: developing an edible landscape brand event and developing diversified marketing (see Figure 5).

Figure 4.

Traditional single marketing model.

Figure 5.

Modern diversified marketing model.

Specifically, one can brand the community with edible landscapes as the core content and conduct branding events to build the community edible landscapes brand. the brand event can also be used as an opportunity to raise community awareness. In this process, the edible landscapes are used to attract participants and increase their emotional attachment and identification with the San-He community place brand so that each participant in the community becomes a promoter and marketer of edible landscapes. As McAlexander et al. [70] reveal in their study on building brand communities, “Through the participation of brand events, many people who participate in brand events feel part of the brand community, primarily because of the way brand events give them greater benefits for consuming the brand, whether these benefits are utilitarian, self-expressive, social, or hedonistic”.

Marketing and promotion can be done through diverse networks (e.g., self-publishing, e-commerce, online marketing, etc.). Self-media such as Jitterbug can be used to sell products, live-stream goods, or promote brands. E-commerce marketing can also be used to promote them more quickly and precisely, so that edible landscapes can be promoted more quickly and comprehensively, and the place brand awareness of edible landscapes in the San-He community can be continuously expanded. As Styvén et al. [71] pointed out in their study, “In the digital age, advertisers should look for the most appropriate digital channels and media to reach their target audiences. Their adoption of online streaming video to spread place branding campaigns is highly effective, judging from the intention of residents to share place branding messages in the form of online streaming video”. The adoption of a diverse network to promote the San-He community Edible Placescape is more conducive to an integrated, authentic, and comprehensive presentation of a San-He community Edible Placescape place brand, and thus more conducive to the promotion and dissemination of the San-He community Edible Placescape marketing.

Again, addressing the current challenges of edible landscaping techniques is key to its further advancement. This is mainly because today’s young people and professionals, such as landscape architects, generally lack experience in the growing techniques which help ensure sustainable, productive, and aesthetically pleasing food, fruit, and vegetable production systems. Therefore, if this growing technology challenge is not addressed, it can seriously hinder the further development of edible landscapes. Place branding can be used to promote the development of edible landscapes by providing education and training programs on growing techniques. As noted by Zenker and Beckmann [66] in their study, place branding can be used to promote education and training programs to improve stakeholders’ skills and knowledge of edible landscapes. Thus, by making edible landscapes unique and desirable places, training programs can be developed to educate stakeholders on essential growing techniques, sustainability practices, and food safety regulations. Also, the use of social media and other marketing channels can help place branding to raise awareness of these training programs and generate interest in edible landscapes.

Overall, the results of this study found that the development of edible landscapes in cities can bring social, economic, and cultural benefits to the community in many ways. This is similar to previous studies by Delormier and Marquis [26], Kortright and Wakefield [27], and He and Zhu [29]. This study also found some inconsistencies in the development of edible landscapes in cities, mainly in that the development of edible landscapes in cities can also promote the development of tourism, food and beverage, and recreation and leisure industries in the community, and can even promote the return of young people to the suburban community and change the demographic structure of the community, thus promoting various aspects of community development. Among the factors that hinder the development of edible landscapes, this study found that government policy constraints and inadequate planting techniques are common problems encountered in the development of edible landscapes in many cities, in line with the findings of Hajzeri and Kwadwo [14], Wang [37], De Guzman et al. [72], He and Zhu [29], and others who all identified these challenges that hinder the development of edible landscapes in their studies. For example, Lovell [73] pointed out that one of the greatest constraints to the development of edible landscapes in urban areas is the limited access to land for those who want to grow food. However, this study found that such a problem does not exist in the development of edible landscapes in Taiwan, mainly because the land system in Taiwan is basically privately owned by the residents, so there is no land constraint. Unlike other studies, this study found a constraint that other researchers have not found before, that is, the marketing and promotion constraint of edible landscapes, which is the key factor that hinders the further development of edible landscapes. Therefore, in the theoretical aspect, this study demonstrates that the marketing and promotion problems encountered in the development of edible landscapes can be solved through place branding, and proposes corresponding strategies to solve them.

Of course, there are inevitable limitations in this study, mainly because this paper takes the edible landscapes of peri-urban communities in Taiwan as the research object, and selects the edible landscapes of communities that are typical of the urbanization process in Taiwan as a case study. The first advantage of using case studies is that they facilitate comprehensive and in-depth analysis of the cases, but the disadvantage is that the results may not be generalizable due to the small number of cases selected. Moreover, the edible landscape itself is place-dependent and varies from country to country and region to region depending on the policy and culture. Therefore, the results of this study may not be extrapolated to other countries or regions, and may only be of reference value to a specific region or country or to those which are culturally similar.

The shortcomings of this study need to be further investigated and improved by subsequent researchers.

6. Research Conclusions

As urbanization continues to grow, urban food security and environmental sustainability are becoming increasingly important global issues. Therefore, making urban food security and the environment sustainable lies at the core of future urban development research. This study uses a case study of the San-He community in Longtan District, Taoyuan City, Taiwan, and uses place branding as a case study to promote the development of urban edible landscapes:

The fundamental reason for the transformation of traditional agricultural landscapes in suburban communities into edible landscapes is that with the development of urbanization, the landscape of the urban environment is too artificial, so people in cities have an inherent demand for natural and idyllic landscapes. This major driving force for the development of edible urban landscapes can bring huge socio-economic benefits to people in suburban and city communities.

San-He Community Edible Landscapes is gradually developing three systems: tourism, food, and environmental education. This development not only promotes the development of the community but also provides many benefits while increasing its visibility.

The main difficulties and challenges in the process of development are (1) the government’s policies bring various constraints and challenges; (2) difficulties and challenges in the marketing and promotion of edible landscapes; (3) difficulties and challenges where planting technology is applied to an edible landscape.

To address the challenges facing the development of edible landscapes in the San-He community. Place branding can be a useful tool for addressing and solving these challenges while promoting the further development of edible landscapes.

During the period of the COVID-19 epidemic, the edible landscape of the San-He community not only provided a buffer chain of vegetable supply for the people in the community but also became a good place for city residents to go out to relax and release their stress during the epidemic. It provides new ideas for sustainable urban development in the post-epidemic era.

This case study concerns the edible landscapes in the San-He community, Longtan District, Taoyuan City, Taiwan, with the aim of gaining insight into the specific situations and challenges of the current urban edible landscape development. These challenges were found to be similar to those identified by many other researchers, with the main challenges being government policy constraints and planting technology challenges [74,75,76]. The difference in the results of this study is that the challenges in marketing and promotion of edible landscapes were found to have been ignored by previous researchers; however, they are important factors in addressing the further development of edible landscapes. Therefore, the solution to these challenges is the key to promoting the development of edible landscapes. The use of place branding strategy as a solution to the current challenges of urban edible landscapes has many advantages, which not only provide a solution for the future development and promotion of urban edible landscapes but also to the sustainable development of cities within the landscape discipline.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Z.-W.Z. and R.-J.C.; Methodology, Z.-W.Z. and R.-J.C.; Investigation, Z.-W.Z.; Writing—original draft, Z.-W.Z.; Writing—review & editing, R.-J.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Mahmood, H.; Alkhateeb, T.T.Y.; Furqan, M. Industrialization, urbanization and CO2 emissions in Saudi Arabia: Asymmetry analysis. Energy Rep. 2020, 6, 1553–1560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.J.; Ng, C.N. Spatial and temporal dynamics of urban sprawl along two urban–rural transects: A case study of Guangzhou, China. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2007, 79, 96–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CIA. The World Factbook. 2023. Available online: https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/fields/349.html (accessed on 2 June 2023).

- Chou, T.L.; Chang, J.Y. Urban sprawl and the politics of land use planning in urban Taiwan. Int. Dev. Plan. Rev. 2008, 30, 67–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.S.; Chen, Y.C.; Tsui, P.L.; Chiang, M.C. Diversified and Sustainable Business Strategy of Smallholder Farmers in the Suburbs of Taiwan. Agriculture 2022, 12, 740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekele, H. Urbanization and Urban Sprawl; Royal Institute of Technology: Stockholm, Sweden, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Eigenbrod, C.; Gruda, N. Urban vegetable for food security in cities. A review. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2015, 35, 483–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Govers, R.; Go, F. Place Branding: GPlace, Virtual and Physical Identities, Constructed, Imagined and Experienced; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Trancik, R. Finding Lost Space: Theories of Urban Design; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Brito, V.V.; Borelli, S. Urban food forestry and its role to increase food security: A Brazilian overview and its potentialities. Urban For. Urban Green. 2020, 56, 126835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Fan, H.; Wei, M.; Yin, K.; Yan, J. From edible landscape to vital communities: Clover nature school community gardens in Shanghai. Landsc. Archit. Front. 2017, 5, 72–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLain, R.; Poe, M.; Hurley, P.T.; Lecompte-Mastenbrook, J.; Emery, M.R. Producing edible landscapes in Seattle’s urban forest. Urban For. Urban Green. 2012, 11, 187–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sartison, K.; Artmann, M. Edible cities—An innovative nature-based solution for urban sustainability transformation? An explorative study of urban food production in German cities. Urban For. Urban Green. 2020, 49, 126604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajzeri, A.; Kwadwo, V.O. Investigating integration of edible plants in urban open spaces: Evaluation of policy challenges and successes of implementation. Land Use Policy 2019, 84, 43–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, B.B.; Philpott, S.M.; Jha, S. The future of urban agriculture and biodiversity-ecosystem services: Challenges and next steps. Basic Appl. Ecol. 2015, 16, 189–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sevik, H.; Cetin, M.; Ozel, H.B.; Ozel, S.; Zeren Cetin, I. Changes in heavy metal accumulation in some edible landscape plants depending on traffic density. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2020, 192, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagaynay, C.; Lee, J. Place branding and urban regeneration as dialectical processes in local development planning: A case study on the Western Visayas, Philippines. Sustainability 2020, 12, 369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aaker, D.A.; Joachimsthaler, E. Brand Leadership; Simon and Schuster: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Eshuis, J.; Klijn, E.H.; Braun, E. Place marketing and citizen participation: Branding as strategy to address the emotional dimension of policy making? Int. Rev. Adm. Sci. 2014, 80, 151–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- François Lecompte, A.; Trelohan, M.; Gentric, M.; Aquilina, M. Putting sense of place at the centre of place brand development. J. Mark. Manag. 2017, 33, 400–420. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez, N.M. Towards a network place branding through multiple stakeholders and based on cultural identities: The case of “The Coffee Cultural Landscape” in Colombia. J. Place Manag. Dev. 2016, 9, 73–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, N. “Single-minded, compelling, and unique”: Visual communications, landscape, and the calculated aesthetic of place branding. Environ. Commun. J. Nat. Cult. 2013, 7, 231–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, J.; Meng, X. English literature research on urban edible landscape from 1995 to 2019. Guangdong Landsc. Archit. 2020, 42, 38–43. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Li, Z.R.; Yu, W.X.; Gao, W. Research progress and trends of urban edible landscape at home and abroad. Chin. Gard. 2020, 36, 88–93. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Rosalind, C. The Complete Book of Edible Landscaping; Sierra Club Books: San Franscisco, CA, USA, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Delormier, T.; Marquis, K. Building healthy community relationships through food security and food sovereignty. Curr. Dev. Nutr. 2019, 3 (Suppl. S2), 25–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kortright, R.; Wakefield, S. Edible backyards: A qualitative study of household food growing and its contributions to food security. Agric. Hum. Values 2011, 28, 39–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, H.; Zhang, T.; Li, T.T. The Construction of Community Edible Landscapes Combining “Peace and War”—Thinking Based on the Prevention and Control of Infectious Diseases. Chin. Gard. 2021, 5, 56. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- He, B.; Zhu, J. Constructing community gardens? Residents’ attitude and behaviour towards edible landscapes in emerging urban communities of China. Urban For. Urban Green. 2018, 34, 154–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, S.; Wu, F.; Wang, Z.; Cui, Y.; Chen, C.; Wei, Y. Evaluation system and application of plants in healing landscape for the elderly. Urban For. Urban Green. 2021, 58, 126969. [Google Scholar]

- Nasir, M.R.M.; Sham, M.S.A.; Mohamad, W.S.N.W.; Hassan, K.; Noordin, M.A.M.J.; Hassan, R. Developing a Framework of Edible Garden Concept for Horticultural Therapy for the Elderly People. J. Appl. Arts 2020, 2, 102–111. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, Y.; Jones, P. Emergent urban agricultural practices and attitudes in the residential area in China. Urban For. Urban Green. 2022, 69, 127491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McClintock, N.; Cooper, J.; Khandeshi, S. Assessing the Potential Contribution of Vacant Land to Urban Vegetable Production and Consumption in Oakland, California. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2016, 148, 105–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Q.; Yue, Y.; Hu, D. Residents’ Attention and Awareness of Urban Edible Landscapes: A Case Study of Wuhan, China. Forests 2019, 10, 1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conway, T.M. Home-based edible gardening: Urban residents’ motivations and barriers. Cities Environ. CATE 2016, 9, 3. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, M. The Applicability of Participatory Design for Urban Community Building. Ph.D. Thesis, The Hong Kong Polytechnic University, Hong Kong, China, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X. Edible Landscapes within the Urban Area of Beijing, China. Ph.D. Thesis, Universität Stuttgart, Stuttgart, Germany, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Daldanise, G. From place-branding to community-branding: A collaborative decision-making process for cultural heritage enhancement. Sustainability 2020, 12, 10399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotler, P. Marketing Places; Simon and Schuster: New York, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Kavaratzis, M. Is corporate branding relevant to places? In Towards Effective Place Brand Management; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, G.X. Study on the Revitalization of Handicraft Resources in the Creation of Ebian Local Brand. Master’s Thesis, China Academy of Art, Hangzhou, China, 2020. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Lew, A.A. Tourism planning and place making: Place-making or placemaking? Tour. Geogr. 2017, 19, 448–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, C.; Cloutier, S.; Eakin, H. Examining the business case and models for sustainable multifunctional edible landscaping enterprises in the phoenix metro area. Sustainability 2017, 9, 2307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lafontaine-Messier, M.; Gélinas, N.; Olivier, A. Profitability of food trees planted in urban public green areas. Urban For. Urban Green. 2016, 16, 197–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maheshwari, V.; Vandewalle, I.; Bamber, D. Place branding’s role in sustainable development. J. Place Manag. Dev. 2011, 4, 198–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, C.S.; Marafa, L.M. Developing a sustainable and green city brand for Hong Kong: Assessment of current brand and park resources. Int. J. Tour. Sci. 2014, 14, 93–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vela, J.D.S.E.; Nogué, J.; Govers, R. Visual landscape as a key element of place branding. J. Place Manag. Dev. 2017, 10, 23–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taiwan Community Access Website. 2022. Available online: https://communitytaiwan.moc.gov.tw/Home/SiteMap (accessed on 27 September 2022).

- Longtan District. Wikipedia. 2022. Available online: https://zh.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E9%BE%8D%E6%BD%AD%E5%8D%80_(%E5%8F%B0%E7%81%A3) (accessed on 27 September 2022).

- Chen, X.M. Qualitative Research in Social Sciences; Wunan Book Publishing Co., Ltd.: Taipei, Taiwan, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Patton, M.Q. Qualitative Evaluation and Research Methods; SAGE Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, X.E. Empirical analysis of in-depth interview research methods. J. Xi’an Jiaotong Univ. Soc. Sci. Ed. 2012, 32, 101–106. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Cai, N.W.; Yu, H.P.; Zhang, L.H. The application of participant observation and non-participant observation in case studies. J. Manag. 2015, 4, 66–69. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Ritchie, J.; Lewis, J.; Nicholls, C.M.; Ormston, R. (Eds.) Qualitative Research Practice: A Guide for Social Science Students and Researchers; SAGE Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Fusch, P.I.; Ness, L.R. Are we there yet? Data saturation in qualitative research. Qual. Rep. 2015, 20, 1408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saunders, B.; Sim, J.; Kingstone, T.; Baker, S.; Waterfield, J.; Bartlam, B.; Burroughs, H.; Jinks, C. Saturation in qualitative research: Exploring its conceptualization and operationalization. Qual. Quant. 2018, 52, 1893–1907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaismoradi, M.; Turunen, H.; Bondas, T. Content analysis and thematic analysis: Implications for conducting a qualitative descriptive study. Nurs. Health Sci. 2013, 15, 398–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beatley, T.; Newman, P. Biophilic cities are sustainable, resilient cities. Sustainability 2013, 5, 3328–3345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, F.; Gou, Z.; Lau, S.S.Y.; Lau, S.K.; Chung, K.H.; Zhang, J. From biophilic design to biophilic urbanism: Stakeholders’ perspectives. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 211, 1444–1452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, M.; Elbe, J.; de Esteban Curiel, J. Has the experience economy arrived? The views of destination managers in three visitor-dependent areas. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2009, 11, 201–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pine, B.J.; Gilmore, J.H. The Experience Economy; Harvard Business Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Z.T.; Zhou, R.J.; Huang, F.Z. The Social Design of Food: The Food Landscape of Taoyuan Cross-ethnic Area. J. Archit. 2018, 19, 25–42. [Google Scholar]

- Riolo, F. The social and environmental value of public urban food forests: The case study of the Picasso Food Forest in Parma, Italy. Urban For. Urban Green. 2019, 45, 126225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wekerle, G.R.; Classens, M. Food production in the city: (Re)negotiating land, food and property. Local Environ. 2015, 20, 1175–1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zenker, S.; Beckmann, S.C. My place is not your place—Different place brand knowledge by different target groups. J. Place Manag. Dev. 2013, 6, 6–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gartner, W.C. Tourism image: Attribute measurement of state tourism products using multidimensional scaling techniques. J. Travel Res. 1989, 28, 16–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodside, A.G.; Lysonski, S. A general model of traveler destination choice. J. Travel Res. 1989, 27, 8–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanna, S.; Rowley, J. Towards a strategic place brand-management model. J. Mark. Manag. 2011, 27, 458–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAlexander, J.H.; Schouten, J.W.; Koenig, H.F. Building brand community. J. Mark. 2002, 66, 38–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Styvén, M.E.; Mariani, M.M.; Strandberg, C. This is my hometown! The role of place attachment, congruity, and self-expressiveness on residents’ intention to share a place brand message online. J. Advert. 2020, 49, 540–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Guzman, R.; Sanchez, F.C., Jr.; Balladares, M.C.E.; Mora, J.A.M.M.; Tayobong, R.R.P.; Medina, N.M.; Aquino, E.C. Edible Landscaping Technology Dissemination in the Philippines: An Evaluation. J. Int. Soc. Southeast Asian Agric. Sci. ISSAAS 2018, 24, 150–158. [Google Scholar]

- Lovell, S.T. Multifunctional urban agriculture for sustainable land use planning in the United States. Sustainability 2010, 2, 2499–2522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, B.B.; Philpott, S.M.; Jha, S.; Liere, H. Urban agriculture as a productive green infrastructure for environmental and social well-being. In Greening Cities; Springer: Singapore, 2017; pp. 155–179. [Google Scholar]

- Purcell, M.; Tyman, S.K. Cultivating food as a right to the city. In Urban Gardening as Politics; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2018; pp. 62–81. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, J.; He, B.J.; Tang, W.; Thompson, S. Community blemish or new dawn for the public realm? Governance challenges for self-claimed gardens in urban China. Cities 2020, 102, 102750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).