Abstract

The purpose of this paper is to investigate the role of the landscape’s cultural values in the practical work of biosphere reserves and to identify what opportunities there are to increase awareness and knowledge about these values. The paper draws upon data collected in a Swedish biosphere reserve, including a survey of residents, interviews with public officials involved in cultural heritage management, and an analysis of documents produced by the Biosphere Reserve Association. Residents showed a broad knowledge about the landscape’s cultural values, and they linked immaterial heritage to material objects. The residents’ strong identity and pride in relation to the landscape were confirmed by the officials, who argued that it is the deep layers of history and the cultural diversity of the landscape that make the biosphere reserve attractive. However, concepts related to the landscape’s cultural values were barely touched upon in the documents analysed; the landscape’s cultural values were presented as a background—as an abstract value. The findings reveal several unexplored opportunities and practical implications to increase awareness and knowledge of the landscape’s cultural values. Suggested actions include definition of goals, articulation and use of concepts, inventories of actors, increased collaboration, and use of residents’ knowledge. Cultural values of landscapes are often neglected in the practical work of biosphere reserves, despite the social and cultural dimensions of sustainable development being an important component of UNESCO’s Man and the Biosphere (MAB) Programme. This research indicates several ways of bridging this gap between theory and practice.

1. Introduction

Despite high-level commitments and recognition of the importance of the social and cultural dimensions in sustainability policy and science, the requirements and concepts have not yet been absorbed into the practical work of biosphere reserves [1,2,3,4,5,6]. UNESCO’s Man and the Biosphere (MAB) Programme “aims to establish a scientific basis for enhancing the relationship between people and their environments” through the World Network of Biosphere Reserves, which, in 2023, included 738 sites in 124 countries [7]. The MAB Programme has claimed to combine the natural and social sciences since its origin in 1976, but this integrated approach has not been straightforward. Reed and Massie argue that even though both social and natural sciences were important components in early documents, the social sciences disappeared quickly and “biosphere reserves were promoted primarily as living laboratories for natural scientists” [1].

However, the living laboratories became learning sites for sustainable development through the establishment of a statutory framework for biosphere reserves in 1995 [1,8,9,10]. From that point onward, goals to preserve cultural diversity and associated cultural values, as well as local livelihoods and ecological systems, became more explicit justifications for the establishment of biosphere reserves. Moreover, the views and needs of diverse local populations became more visible, in turn supporting a wider rethinking of issues of inclusive governance. These changes have been reiterated and refined through a series of MAB strategy documents and the Madrid (2008–2013) and Lima (2016–2025) action plans, all of which embrace the function and importance of people in the environment [11,12,13]. Today, UNESCO presents biosphere reserves as learning places for sustainable development, involving local communities and stakeholders in planning and management, and integrating three main functions: (1) conservation of biodiversity and cultural diversity; (2) economic development that is socio-culturally and environmentally sustainable; and (3) logistical support, underpinning development through research, monitoring, education, and training [14].

Thus, the social and cultural dimensions of sustainable development today, at least in theory, are an important component of biosphere reserves. However, recent research demonstrates that a bias towards nature conservation continues to exist within biosphere reserves, and that there is a need for more human-centred conservation approaches [2,3,5]. As Reed and Massie explain, there is “a wide gap between the conceptual emphasis placed by UNESCO on the social and cultural dimensions of sustainable development and the priorities or activities of biosphere reserves” [1]. This gap is also evident in a report from UNESCO, which states that biosphere reserves provide a “wealth of experience and insights on the role of culture as an enabler and as a driver of sustainable development”, but “this is not the language used in the context of the MAB Programme” [15]. Still, a recent study reports that nomination forms for biosphere reserves focus on conservation aspects and contributions from the natural sciences [5].

The results presented from a survey including 148 biosphere reserves in 55 countries suggest a discrepancy between the stated mission of the MAB Programme and practice, but they nevertheless indicate that many biosphere reserves have the potential to function as learning sites for social–ecological resilience [9]. However, the results from interviews with managers in 16 Canadian biosphere reserves clearly show low priorities and effectiveness of fostering social and cultural development [1]. The authors offer two potential explanations for their results: the interpretation of the concept of social and cultural dimensions, and the understanding of the UNESCO mandate and plans. They suggest that the gap “could be addressed through improved communication about the expectations and meaning of social and cultural dimensions of sustainability” [1]. However, in addition to these explanations, it should also be added that the social and cultural dimensions are complex and multifaceted, and the guidance put forward by UNESCO on these matters lacks clarity and practical tools to conceptualise and integrate these aspects into management and decision-making in biosphere reserves [6].

Achieving the social and cultural dimensions of sustainable development in practice is not a simple pursuit, in part because of the inherent breadth and complexity of biosphere reserves, but also because the committees that oversee them lack the regulatory authority, direct management, and decision-making powers that are generally required to take action [1,16]. Instead, biosphere reserves are overseen by local community committees that undertake educational and demonstration projects, provide logistical support for scientific research, coordinate regional conservation or sustainability initiatives, and may work with relevant government agencies in cooperative decision-making forums. The aspiration of such a community-based approach is that biosphere reserves will improve the relationships between people and their environment through “people-centred conservation, which explicitly acknowledges humans and human-interests in the conservation landscape” [2]. A bottom-up approach is thus central in biosphere reserve practices, as well as collaboration, learning, and a holistic view of people and nature. Previous studies demonstrate that biosphere reserve organisations can indeed be successful in acting as platforms for collaboration and connecting actors vertically and horizontally, thereby bridging sectorial decision-making processes [17,18,19,20,21].

As shown above, cultural values of landscapes are often neglected in the practical work of biosphere reserves, despite the social and cultural dimensions of sustainable development being important components of the MAB Programme. The aim of the present paper was to investigate the role of the landscape’s cultural values in the practical work of biosphere reserves and to identify what opportunities there are to increase awareness and knowledge about these values. As a bottom-up approach is central in biosphere reserves, and previous studies demonstrate that they can act as platforms for collaboration [17,18,19,20,21], we investigated residents’ opinions in relation to their favourite outdoor places [22,23] as well asthe work of public officials [24,25], and documents produced in a Swedish biosphere reserve. More precisely, the aims, formulated as questions, were as follows:

- What awareness and knowledge of cultural values do residents have?

- How well do residents’ awareness and knowledge mirror cultural heritage management at the local and regional planning levels?

- Are there any collaborations within the biosphere reserve regarding the landscape’s cultural values?

- Are concepts related to the landscape’s cultural values considered in documents produced by the Biosphere Reserve Association?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. The Case Study Area

The case study area, Lake Vänern Archipelago Biosphere Reserve, is in South Sweden and includes the municipalities of Mariestad, Götene, and Lidköping, with a total population of 80,000 inhabitants (Figure 1). The geographical area comprises part of Lake Vänern, its archipelagos, and an arable landscape with a varied topography consisting of postglacial clay plains, mylonite intrusions, glacial moraine deposits, and a Cambro-Silurian flat-topped mountain named Kinnekulle. People have lived in the area for at least 6000 years, and its richness in landmarks and artefacts dating back to the Bronze Age implies millennia of cultivation and influence on the landscape, which is still visible in the richness of plant species [26]. The landscape’s high natural and cultural values formed the basis for UNESCO’s designation of it as a biosphere reserve in 2010.

Figure 1.

Lake Vänern Archipelago Biosphere Reserve in Sweden, including the three municipalities of Mariestad, Götene, and Lidköping. Source: Lantmäteriet state of dispersal Dnr 601-2008-855.

A non-profit Biosphere Association with members representing the public, private, and non-profit sectors, together with a coordinator and staff, is responsible for projects and coordination in the biosphere reserve. The work is carried out with a focus on communicating knowledge and strengthening ecosystem services, increasing opportunities to lead a sustainable everyday life, contributing to sustainable businesses, and strengthening the biosphere reserve’s brand [27]. Since its designation as a biosphere reserve, the non-profit association has carried out several projects in addition to its basic activities. Together, these activities have generated approximately SEK 50 million in economic activity and engaged many players in the area’s development. However, the Biosphere Association does not operate with any formal authority over the land or waters, since no laws or regulations specifically addressing biosphere reserves have been implemented in Sweden. With regard to the social and cultural dimensions of sustainability, the Swedish municipalities have the main responsibility for sustainable land-use planning. To improve collaboration among local authorities, the Biosphere Association established a working committee in 2017, with the aim of integrating the management bodies of the municipalities in the Biosphere Association.

The Swedish National Heritage Board, under the Ministry of Culture, is the national administrative agency for cultural heritage and cultural environment. It is responsible for the 2030 Vision for cultural heritage management in Sweden. An important goal of the vision is to increase awareness that cultural heritage and the cultural environment are important parts of the work for a sustainable, inclusive society [28]. The County Administrative Board represents the government at the regional planning level, and each Swedish county has at least one regional museum that receives public grants from the region and state to pursue work related to the cultural environment and heritage.

2.2. Research Design

This paper is part of an interdisciplinary research project with the aim of investigating the role of cultural heritage and the historic environment in sustainable landscape management [23,29,30]. The present paper draws upon data collected from a landscape survey, interviews, and documents. A qualitative, single case study approach [31,32,33,34] was used to gain a deeper understanding of the issues at hand. The interdisciplinary project team included researchers with expertise in the fields of physical geography, conservation of the built environment, psychology, biocultural heritage, and protected area management.

2.3. Landscape Survey

In the autumn of 2017, a survey was sent to a total of 2989 households, identified from a population register and randomly and proportionally distributed across three municipalities (Lidköping 51.2%, Mariestad 31.5%, and Götene 17.2%) encompassing the Lake Vänern Archipelago Biosphere Reserve. In total, 884 residents answered the survey. They were not offered any incentive to participate. The survey was anonymous and was conducted in accordance with the ethical guidelines of the APA and the University of Gothenburg Sweden, which oversaw the project. The survey involved several sections, including quantitative and qualitative questions. In this paper, only qualitative data—i.e., results from open-ended questions—are reported; however, see [23] for the quantitative results. The questions analysed in the present paper are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Landscape survey—questions analysed.

2.4. Interviews

In total, 18 semi-structured interviews were conducted between 2018 and 2019 with officials employed or otherwise engaged by local and regional public agencies and other actors, including municipalities, the County Administrative Board, local museums, and the Biosphere Association. The respondents each had formal responsibilities related to the planning and management of the landscape’s cultural values but represented a range of occupations and disciplines, such as historians, built-heritage conservation, urban and landscape planning, environment conservation, engineering, and architecture. Respondents were identified through discussions in the project group and via webpages. The respondents were approached via telephone or e-mail, and they were able to choose the location for a face-to-face interview, which lasted one hour on average and was recorded and transcribed. The themes and questions analysed in the present paper are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Interview instrument—themes and questions analysed.

Each interview started with a discussion about the research project, and the respondents were then asked to specify their educational and professional backgrounds, as well as their current work assignments. Note that no definitions of concepts related to the landscape’s cultural values were given in advance; thus, the respondents’ answers were based on their own interpretations. During the interview, the respondents were also asked to visualise existing collaboration (Table 2) by drawing lines between six circles on a sheet of A4 paper. Five of the circles included predefined alternatives: the biosphere reserve, the municipality, the County Administrative Board, the regional cultural development administration, and Lake Vänern Museum. The sixth circle was empty, and respondents were given the opportunity to add one or several collaboration partners.

Each respondent’s answer was analysed via transcripts and audio recordings. The responses were compiled in a spreadsheet and were categorised thematically based on their semantic content. Data from the semi-structured interviews are reported using “bottom up” (based on open questions) and “top down” analyses, where “the analytic process involves a progression from description, where the data have simply been organized to show patterns in semantic content, and summarized, to interpretation, where there is an attempt to theorize the significance of the patterns and their broader meanings and implications often in relation to previous literature” [32]. These analyses were conducted with an emphasis on listening, meaning that the interviewer actively avoided influencing and biasing the conversation [35]. To thoroughly understand the data, the transcripts were read several times and, when needed, the original audio recordings were reviewed [32].

2.5. Documents

In total, 57 documents, available on the Lake Vänern Archipelago Biosphere Reserve webpage, were included in the analysis for the present paper (Table 3). These documents included the application to UNESCO, archived reports and projects, annual reports, and one periodic review report to UNESCO (Table 3).

Table 3.

Type and number of documents analysed.

Each document was analysed in three steps: First, a search was performed with three groups of keywords (see Table 4). Second, each document was read through a “cultural lens” to examine whether the landscape’s cultural values were described in terms other than with the keywords. Third, the results from steps 1 and 2 were compiled in diagrams to analyse whether, and in what way, the landscape’s cultural values had been taken into account during the planning and implementation phases of the Lake Vänern Archipelago Biosphere Reserve.

Table 4.

Keywords used during the search of the documents.

3. Results

The findings are reported in line with the three types of data (survey, interviews, and documents) described in the above section.

3.1. Landscape Survey

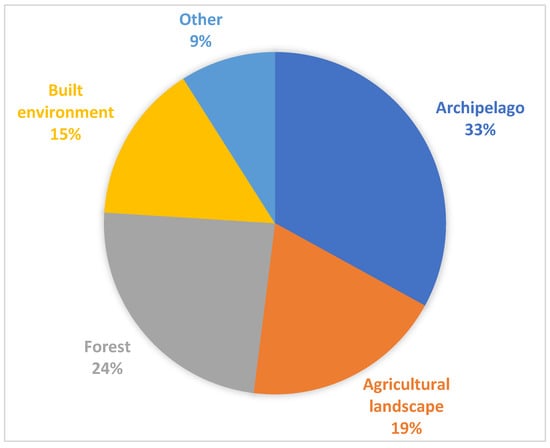

In the landscape survey, the participants were asked questions related to their favourite outdoor places [22,23]. The results showed that 809 residents pointed out 130 personal favourite places. Of these, 65 places were mentioned only once. The participants were also asked to categorise their personal favourite place as belonging to several environmental categories. As shown in Figure 2, most of the respondents’ favourite places were in the archipelago, the forest, or the agricultural landscape. However, 15% of favourite places were categorised as built environment. As many as 24% of participants responded that their favourite place was located within the towns of Mariestad or Lidköping.

Figure 2.

Five environmental categories (archipelago, agricultural landscape, forest, built environment, or other) describing (in percent) the residents’ personal favourite places.

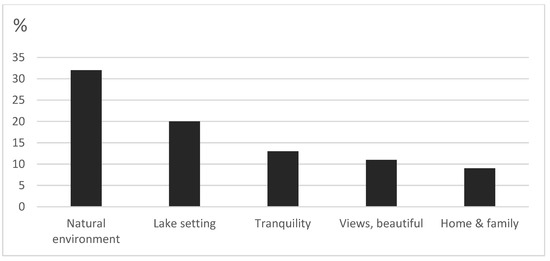

The residents were also asked to describe what they valued most in their favourite place (Table 1). The results show that 32% of the participants valued the natural environment the most, which they described with words such as “nature, forest, plants and animals” (see Figure 3). The lake setting, described in terms such as “water, the lake Vänern, and archipelago”, was the second most important category, valued by 20% of the participants. For many it was the sense of calm that was most important, with 13% of participants valuing tranquillity at their favourite place, using words such as “quiet, calm, soothing, freedom, and silence”. Others felt that the scenery and beauty of the landscape were essential, with 11% of the participants valuing these views. Finally, 9% valued aspects such as “living, home, and possibilities to socialize with family and friends” at their favourite place (see Figure 3). One of the participants expressed the value of their favourite place with the following words:

Figure 3.

Five most valued categories (in percent) of what residents value most in their personal favourite places.

“My family farm includes both agriculture and forestry and is where I’m building a new house. This farm is included on the first maps of the 17th century. Beautiful! What a joy having the opportunity to live and preserve this cultural and natural treasure by means of active farming!”

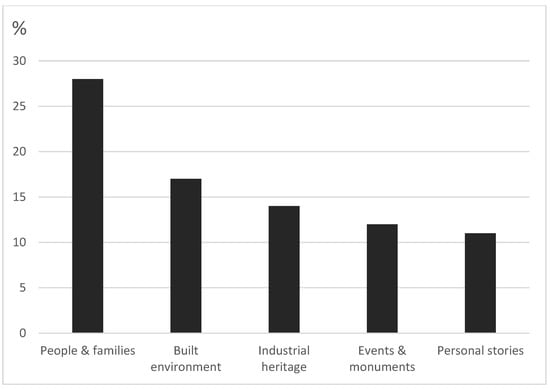

As shown in Figure 4, the participants had knowledge about historic events in the biosphere reserve. For example, the role of historic persons and families and their connection to the landscape and cultural heritage was well known. Several participants wrote about King Olof Skötkonung who, in the 11th century, was the first Swedish king to convert to Christianity and, according to the traditional interpretation, was baptised at Husaby just north of a church on Mount Kinnekulle. Many participants also described the influence of the De la Gardie family who, in the 17th century, extensively rebuilt the medieval Läckö Castle—now a Swedish national monument—close to Lake Vänern. Many participants also mention the botanist Carl Linnaeus, who classified plants in the area in the middle of the 18th century. The work of Linnaeus and his students is of great importance for understanding the biocultural heritage of Mount Kinnekulle—a favourite place for one-quarter of the participants.

Figure 4.

Five most valued categories (in percent) of what residents know about historic events associated with their personal favourite places.

Moreover, the industrial heritage—such as the crafts and traditions of liming and burning, brickwork, millstone quarrying, glassworks, and slate mining—has made a historic imprint on the landscape (see Figure 4). The long tradition of fishing and shipping on Lake Vänern, as well as the associated lighthouses, ports, boats, and ongoing fishing industry, is another example of the cultural imprint on the landscape noted by participants. Graves, rock carvings, city fires, and an aviation disaster during World War II are other examples of historic events and monuments given by the participants. Personal stories, fates, and legends connected to residents’ personal favourite places were also described by many (see Figure 4). For some participants, the cultural features of the landscape are part of their everyday life, as exemplified here by a quote from one participant:

“…a stone, an old well, a fence post, remains of an old croft – these are all important cultural features for us who live here, we are the 9th generation at this place…”

Another example is the story and fate of “Lasse in the mountain” that seems to engage many of the participants. Lasse Eriksson lived with his wife in a cave made of a walled-in limestone outcrop for more than 25 years during the 19th century. The cave has been rebuilt and the site is open to visitors, and a film based on the story was made in 2016.

3.2. Interviews

During the interviews with public officials, we asked whether they knew which outdoor places in the biosphere reserve were residents’ favourites. We also asked whether they knew what the residents valued at their favourite places (see Table 4). It emerged that the places pointed out by the officials as the residents’ favourite places were in line with residents’ own answers in the survey. Officials were also generally aware of what was most valued by the residents. In the words of one of the officials:

“When you go around you come across environments that have been created during thousands of years—I think you feel the passage of time as well. When you go past the churches you know that inside there are paintings from the 1000s. Moreover, people extracted stone from the mountain 3000 years ago. In addition, you can still see the unique touch from the different people on the surface of the stone. It is almost breath-taking.”

Interviews with officials reaffirmed that Mount Kinnekulle is an important favourite place for residents (according to one-quarter of the participants in the survey). The officials described the mountain as a visual and restful vantage point, where one feels the wings of history. Kinnekulle is often called “the flowering mountain” due to the wild garlic that flowers there in May. Officials also described the mountain as a “pilgrimage” where many people go to have picnics, hike, and be with family and friends. Several respondents argued that rather than the flowers or biological features it is the historic landscape that is the main attraction. Old stone walls and other features make it easy to form ideas of the people who once lived in and cultivated the landscape. This is illustrated by the following quote by another official:

“There are both natural and cultural values, which is something we always have to explain—that nature would not be there without the culture. We do not have any wild areas; everything is characterized by culture, so you can’t separate them.”

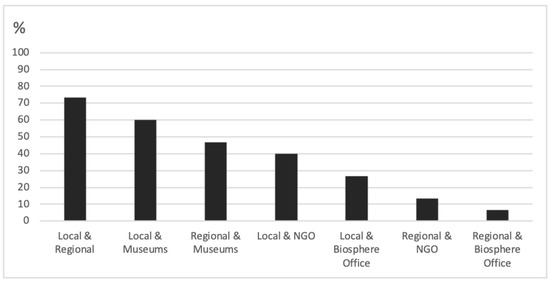

Another question asked during the interviews was about collaboration. As shown in Figure 5, most collaboration on issues related to the landscape’s cultural values exists between the local and regional public agencies and museums, all of which have formal assignments to manage the cultural environment and heritage. However, the results also showed that non-governmental organisations play a strong role in the management of the cultural environment (Figure 5). While national, regional, and local authorities are responsible for the monumental heritage, such as churches and castles, the industrial and agricultural heritage (e.g., stone quarrying, slate mining, sawmills, and the fishing industry) are often managed by non-governmental organisations. The results showed that local and regional authorities assist with networking and specific project resources rather than being in charge of management. According to the officials, the non-profit work by the non-governmental organisations’ members is grounded in their strong interest in local history and local identity issues.

Figure 5.

Collaboration on issues related to the cultural environment in the biosphere reserve, measured as percentages (y-axis). The x-axis shows the various actors, including local and regional authorities, museums, the Biosphere Association, and NGOs.

The interviews revealed that the Biosphere Association has no staff responsible for the planning and management of the social and cultural dimensions of sustainability. Instead, they rely on established structures such as the local and regional public agencies. However, as shown in Figure 5, only one-quarter of the interviewees noted that a collaboration exists between the Biosphere Association and the local authorities, and as few as 10% between regional authorities and the Biosphere Association. This limited collaboration was confirmed during the interviews, where several officials said that they did not have any contact with the Biosphere Association or even did not know anything about it. In the words of one respondent:

“I have not really understood what they are doing and since they do not work with landscape and history, then it falls outside my area of work.”

Some respondents argued that the biosphere reserve lacks a clear profile, and that the organisation is fragmented. They expressed a desire for the Biosphere Association to be a platform for landscape issues—a relatively neutral place for various actors, such as local and regional public agencies, non-profit organisations, and landowners. The results show that most of the officials want stronger and more continuous collaboration within the biosphere reserve. They argue that increased cooperation between local and regional authorities and other actors within the biosphere reserve is required to achieve sustainable development, as well as to integrate the cultural and natural values of the landscape into this work. One example of an initiative for cooperation between different actors within the biosphere reserve is the ecosystem service network. This network was initiated by a public official at the municipality level a few years ago in connection with the publication of national directives to implement the ecosystem service approach in practice. The motive was to increase cooperation between actors on issues related to ecosystem services by forming a horizontal platform for discussion that creates trust and common targets. The network consists of representatives from the three municipalities, the County Administrative Board, the Biosphere Association, and two nature conservation associations. Actors with expertise in the social and cultural dimensions of sustainability are sometimes invited but are not regular members of the network. It is evident that the existence of the biosphere reserve has had a positive effect on collaboration on and implementation of the ecosystem service approach in the present case study area. The respondents argued that the network is an important arena for discussions on ecosystem services. The network meets regularly, and it has applied and received funds for training projects in ecosystem services for politicians, public officials, and developers working within the biosphere reserve. Nevertheless, at the time of the interviews, the respondents expressed a great deal of uncertainty about how to work with the ecosystem service approach. Cultural ecosystem services were less known and were given less consideration than other ecosystem services [29].

3.3. Documents

The results show that the keywords (Table 4) appear in 19 of the 57 documents analysed (Table 5). The majority of hits were found in the application to UNESCO for designation as a biosphere reserve, with 40 matches for the keyword “cultural environment” and 9 for the more specified keywords “cultural heritage, cultural history and cultural values”. Search results for the keyword “culture” in the context of landscape, places, areas, and values showed hits on 62 of the 126 pages in this document (Table 5). The review of the application to UNESCO showed that aspects related to the landscape’s cultural values are recognised mainly in paragraphs where the natural environments are described as assets for the area. Examples of such writings include “The area is known for its rich variety of outdoor life and recreation, unique flora and cultural history” and “Promote a long-term development, based on the area’s natural and cultural environmental qualities” [36]. However, the significance of the concepts of cultural environment and cultural heritage is not described in the application to UNESCO, apart from the description of 19 architectural monuments. Moreover, the text does not refer to any inventories of actors working with the cultural environment or to previous projects related to social and cultural dimensions of sustainability.

Table 5.

Numbers of hits in different documents for three groups of keywords.

Table 5 also shows that 14 of 28 reports included at least one of the keywords; however, the numbers of hits were low. The highest number of hits per document was five, which occurred in three reports. The first was the report “Table Mountain—Geopark”, which is a document clearly based upon the historical environment and cultural heritage of the landscape. The second report, “Social Enterprise Workshop”, stated that cultural heritage is a basis for certain business activities, and that it has development potential. The third report, “Volunteering in the Biosphere Reserve”, states that cultural history, cultural events, and historical landscapes are excursion destinations. Another report, “The Forestry of the Future”, stands out, as the text is based on historical perspectives and lessons learned from history, but the search results only showed one keyword match. In the remaining 24 reports, texts about social and cultural dimensions of sustainability were either non-existent or simplistic, where the cultural environment was described as taken for granted—a backdrop in the landscape.

As shown in Table 5, only three keyword matches were found in 3 of the 20 project documents available on the biosphere reserve’s webpage. No keyword matches were found in the nine annual reports analysed (Table 5), except for references to the present research project.

The analysis of the periodic review report to UNESCO [27] showed 67 matches for the keywords (Table 5). However, the review showed that, in line with the text in the application to UNESCO, the keywords were used mainly in sweeping terms, such as “The castle is surrounded by a stunningly rich natural environment, with the Kållandsö cultural landscape meeting islets, skerries and a rich flora and fauna”. In some paragraphs, the landscape’s cultural values are described without using any of the present study’s keywords (Table 4). One example is when the text briefly touches upon identity and cultural heritage in relation to a documentary film about three generations of commercial fishermen. Another example is a brief description of the agrarian history of meadows and ancient remains under the heading “Ecosystem services”. However, the concept of cultural ecosystem services is mentioned only three times throughout the document, all in relation to the present research project presented in this paper. It should be noted that the periodic review report acknowledges “Over the years, a lot of the focus has been on economy and ecology, but there is considerable potential for the development of better social sustainability” [27].

4. Discussion

In this section, we shall discuss the results in relation to the four questions set out in the Introduction.

4.1. What Awareness and Knowledge of the Landscape’s Cultural Values Do Residents Have?

The residents participating in the landscape survey were aware, and had a broad knowledge, of the landscape’s cultural values in the biosphere reserve. They expressed interest in and knowledge about both material and immaterial heritage and how these aspects are related at their favourite places. One example is the connection between historic persons and families, the built heritage, and related stories and legends. The results also showed a strong local identity in relation to the long tradition of the crafts and traditions of, for example, liming and burning, brickwork, and fishing in the area. The sense of calm, scenery, beauty, and the possibility of socialising with family and friends were among the most valued aspects of the residents’ favourite places. These results are in line with recent research showing that the most valued attributes at residents’ favourite places in the Swedish mountains are related to aesthetic values of the landscape, such as “beautiful, wide vistas, views, terrain, towering mountain”, and to outdoor restoration experiences such as “relaxation, recreation, spirituality, freedom, silence, peace and quiet” [22].

In the present study, several of the residents’ favourite outdoor places were in the built environment and towns. These results confirm the importance of considering urban areas in biosphere reserves. In the Lake Vänern Archipelago Biosphere Reserve, the small towns and settlements are considered as integrated parts of the biosphere reserve. However, in many other parts of the world, biosphere reserves consist of protected nature areas with no connection to urban areas. The role of biosphere reserves for sustainable urban development has been developed within the UNESCO MAB Programme in order to facilitate integrated sustainable resource management, foster the conservation of urban ecosystems, and improve environmental governance [37,38].

4.2. How Well Do Residents’ Awareness and Knowledge Mirror Cultural Heritage Management at the Local and Regional Planning Levels?

Interviews with public officials confirmed the survey findings that showed a strong local identity and pride, linked to the landscape of the biosphere reserve, among residents. According to the officials, above all, the deep layers of history and the cultural diversity of the landscape are what makes the biosphere reserve attractive. Some respondents argued that the main attraction is not the natural values but the landscape’s time-depth and the stories that it provides people. These results give implications of a strong focus on immaterial values in landscape planning and management at the local and regional levels. However, this is not always reflected in the officials’ daily work, which has a focus on material landscape dimensions [24,29,30]. Residents’ interest in and knowledge of local history were also reflected in the fact that non-governmental organisations often oversee the management of the industrial and agricultural heritage related to, for example, sawmills, the fishing industry, stone quarrying, and shale mining. The role of local and regional authorities was to assist these organisations with networking and specific project resources rather than being in charge of management. These results are in line with previous findings from the County of Jämtland in Sweden, showing that a key factor for the successful management of historic landscapes is obtaining a balance between expert conservation practice and non-expert practice guided by personal engagement, sense of responsibility, and personal wellbeing [25].

4.3. Are There Any Collaborations within the Biosphere Reserve regarding the Landscape’s Cultural Values?

Previous research has demonstrated that biosphere reserves can act as platforms for collaboration [17,18,19,20,21]. However, this is not evident in the present study, which shows a very limited collaboration on issues related to the landscape’s cultural values between the Biosphere Association and local and regional public agencies or NGOs. Several of the officials interviewed had limited or no knowledge about the Biosphere Association, and some respondents reported that the organisation is fragmented and lacks a clear profile. However, the idea of a platform for collaboration appealed to most respondents who wanted a stronger and more continuous dialogue within the biosphere reserve to achieve sustainable development. The network for ecosystem services is one good example of collaboration between different actors that is already set up within the biosphere reserve. The network has successfully created new forms of collaboration and an extended dialogue about ecosystem services between different actors at different levels, including training programs for politicians and developers. A weakness that counteracts a holistic and sustainable approach is that experts on the landscape’s cultural values are not regular members of the network. For the formation of the network, the existence of a biosphere reserve was important. The implementation of the ecosystem service approach was in an initial stage in the case study area at the time of the interviews, and the respondents stated that the work was tentative and that cultural ecosystem services were especially difficult to concretise [29,30].

4.4. Are Concepts Related to the Landscape’s Cultural Values Considered in Documents Produced by the Biosphere Association?

The results showed that the role and importance of the landscape’s cultural values, which were a basis for the designation by UNESCO, were barely touched upon in the Biosphere Association’s published materials. This is a result that confirms previous studies, reporting a lack of focus on social and cultural values in biosphere practice [1,2,3,5]. The concepts of cultural environment and cultural heritage were generally not defined, and descriptions were vague in all documents analysed. The cultural environment was seen as a background; a scene; something that is obvious; an abstract value of the landscape. A clear understanding of the significance of the landscape’s cultural values for sustainable development was rarely expressed. The document analysis did not reveal any major interest or commitment on the part of the Biosphere Association to highlight the importance of managing the landscape’s history and cultural values. It is clear that the Biosphere Association has not problematized the concepts of social and cultural dimensions of sustainability in their activities. This can be explained partly by the fact that, in Sweden, the nomination process of a biosphere reserve involves local enthusiasts and local/regional expertise but rarely integrates researchers—particularly those from the social sciences and humanities [5]. However, even though a bottom-up approach is important within biosphere reserves, the residents’ interests and knowledge of tangible and intangible heritage were not reflected in the documents produced by the Biosphere Association. These results are in line with research that shows how the relevance of local, traditional, and experiential knowledge, passed down from one generation to another, is recognised in sustainable landscape management but less common in practice [39,40].

5. Conclusions

The social and cultural dimensions of sustainability are complex and multifaceted and, as argued by Weller [6], the UNESCO guidance lacks clarity and practical tools. We agree with [1] that improved communication on expectations and the meanings of the social and cultural dimensions of sustainability are crucial to increase the broad understanding of these concepts and the UNESCO mandate. If, for example, the concepts describing the landscape’s cultural values are not defined, articulated, and actively used in projects and activities, actors with the right expertise will not be attracted. The language used in the documents produced by the Biosphere Association in the present study did not encourage actors with knowledge of cultural heritage management, and without this expertise it is difficult to define which aspects are important. Many of the projects and activities initiated and supported by the Biosphere Association in the present study made use of the landscape’s cultural values but did not label them as such. In fact, the biosphere reserve would not have been designated by UNESCO without these values, but if not articulated it is difficult to find areas of collaboration. Our results show that the Biosphere Association in the present study is aware of the very limited focus on the social and cultural dimensions of sustainability, as in the periodic review report to UNESCO they acknowledge that the “focus has been on economy and ecology” [27]. One major obstacle is that biosphere reserves lack the necessary regulatory authority, direct management, and decision-making powers [1,16]. The results of the present study show that the Biosphere Associations do not have any legal authority related to the planning and management of the social and cultural dimensions of sustainability; they rely on collaboration with local and regional authorities on these matters. However, as shown above, such collaboration is limited.

Despite the limited role of the landscape’s cultural values identified in the present study, we can conclude that several unexplored opportunities exist to increase awareness and knowledge about these values (Table 6). One such opportunity is to make use of residents’ knowledge and interest as a resource to link the immaterial heritage to the material objects. Our study clearly shows that the residents showed a broad knowledge about the landscape’s cultural values. Their strong identity and pride in relation to the landscape were confirmed by the public officials, who argued that it is the deep layers of history and the cultural diversity of the landscape that make the biosphere reserve attractive. Residents’ knowledge is also reflected in the ambitious work of non-governmental organisations. Collaboration between the Biosphere Association and the local and regional public agencies, as well as NGOs and the civil society, is a key factor in order to increase awareness and knowledge of the landscape’s cultural values. This also includes inventories of actors, definition of goals, and articulation and use of concepts.

Table 6.

Opportunities identified to increase awareness and knowledge of the landscape’s cultural values.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, I.E., S.F., I.K., E.G. and J.W.; methodology, I.E., S.F. and I.K.; formal analysis, I.E., S.F. and I.K.; investigation, I.E., S.F. and J.W.; writing—original draft preparation, I.E.; writing—review and editing, I.E., S.F., I.K., E.G. and J.W.; supervision, I.E.; project administration, I.E.; funding acquisition, I.E., I.K. and E.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Swedish National Heritage Board (Dnr 3.2.2-5202-2016) and is part of the project “Cultural heritage and the historic environment in sustainable landscape management”. Co-funding was also received from University of Gothenburg, Sweden, and the University of Gävle, Sweden.

Data Availability Statement

Not Applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Reed, M.G.; Massie, M. What’s Left? Canadian Biosphere Reserves as Sustainability-in-Practice. J. Can. Stud. 2013, 47, 200–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coetzer, K.L.; Witkowski, E.T.F.; Erasmus, B.F.N. Reviewing Biosphere Reserves globally: Effective conservation action or bureaucratic label? Biol. Rev. Camb. Philos. Soc. 2014, 89, 82–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stenseke, M. Integrated landscape management and the complicating issue of temporality. Landsc. Res. 2016, 41, 199–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, M.G. The contributions of UNESCO Man and Biosphere Programme and biosphere reserves to the practice of sustainability science. Sustain. Sci. 2019, 14, 809–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kjellqvist, T.; Rodela, R.; Lehtilä, K. Meeting the Challenge of Sustainable Development: Analysing the Knowledge Used to Establish Swedish Biosphere Reserves, 1st ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2020; pp. 102–113. [Google Scholar]

- Weller, J. Cultural Ecosystem Services in the Beaver Hills Biosphere; Beaver Hills Biosphere Reserve Association: Sherwood Park, AB, Canada, 2020; Available online: https://www.beaverhills.ca/learn/projects/project/cultural-ecosystem-services (accessed on 1 February 2023).

- UNESCO. Man and the Biosphere Programme. Available online: https://en.unesco.org/mab (accessed on 1 February 2023).

- Batisse, M. Biosphere reserves: A challenge for biodiversity conservation and regional development. Environ. Sci. Policy Sustain. Dev. 1997, 39, 6–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schultz, L.; Lundholm, C. Learning for resilience? Exploring learning opportunities in biosphere reserves. Environ. Educ. Res. 2010, 16, 645–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, M.G.; Price, M.F. UNESCO Biosphere Reserves: Supporting Biocultural Diversity, Sustainability and Society, 1st ed.; Routledge: Milton, ON, Canada, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. Biosphere Reserves: The Seville Strategy & the Statutory Framework of the World Network; UNESCO: Paris, France, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. Madrid Action Plan for Biosphere Reserves: 2008–2013; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. A New Roadmap for the Man and the Biosphere (MAB) Programme and its World Network of Biosphere Reserves; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. Biosphere Reserves. Available online: https://en.unesco.org/biosphere/about (accessed on 1 February 2023).

- UNESCO. UNESCO’s Work on Culture and Sustainable Development Evaluation of a Policy Theme; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- de Lucio, J.V.; Seijo, F. Do biosphere reserves bolster community resilience in coupled human and natural systems? Evidence from 5 case studies in Spain. Sustain. Sci. 2021, 16, 2123–2136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsson, P.; Folke, C.; Galaz, V.; Hahn, T.; Schultz, L. Enhancing the Fit through Adaptive Co-management: Creating and Maintaining Bridging Functions for Matching Scales in the Kristianstads Vattenrike Biosphere Reserve, Sweden. Ecol. Soc. 2007, 12, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schultz, L.; Folke, C.; Olsson, P.E.R. Enhancing ecosystem management through social-ecological inventories: Lessons from Kristianstads Vattenrike, Sweden. Environ. Conserv. 2007, 34, 140–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandström, E.; Olsson, A. The Process of Creating Biosphere Reserves. An Evaluation of Experiences from Implementation Processes in Five Swedish Biosphere Reserves; Swedish Environmental Protection Agency: Stockholm, Sweden, 2013.

- Heinrup, M.; Schultz, L. Swedish Biosphere Reserves as Arenas for Implementing the 2030 Agenda; Swedish Environmental Protection Agency: Stockholm, Sweden, 2017.

- Sandström, E.; Sahlström, E. Biospheres Reserves through Collaborative Governance—A Study of Organisational Forms and Collaborative Processes in Sweden’s Biosphere Reserves; Swedish Environmental Protection Agency: Stockholm, Sweden, 2021.

- Knez, I.; Eliasson, I. Relationships between personal and collective place identity and well-being in mountain communities. Front. Psychol. 2017, 8, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knez, I.; Eliasson, I.; Gustavsson, E. Relationships Between Identity, Well-Being, and Willingness to Sacrifice in Personal and Collective Favorite Places: The Mediating Role of Well-Being. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eliasson, I.; Knez, I.; Fredholm, S. Heritage Planning in Practice and the Role of Cultural Ecosystem Services. Herit. Soc. 2018, 11, 44–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredholm, S.; Eliasson, I.; Knez, I. Conservation of historical landscapes: What signifies ‘successful’ management? Landsc. Res. 2018, 43, 735–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gustavsson, E.; Lennartsson, T.; Emanuelsson, M. Land use more than 200 years ago explains current grassland plant diversity in a Swedish agricultural landscape. Biol. Conserv. 2007, 138, 47–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Periodic Review Report Lake Vänern Archipelago Biosphere Reserve 2010–2020. 2020. Available online: https://biosfarprogrammet.se/wp-content/uploads/Periodic-Review-Lake-Vanern-Archipelago-and-Mount-Kinnekulle-BR-2010-2020.pdf (accessed on 1 February 2023).

- COE. 2030 Vision for Cultural Heritage Management in Sweden. Available online: https://www.coe.int/en/web/culture-and-heritage/-/2030-vision-for-cultural-heritage-management-in-sweden (accessed on 1 February 2023).

- Gustavsson, E.; Eliasson, I.; Fredholm, S.; Knez, I.; Nilsson, L.G.; Gustavsson, M. Min Plats i Biosfären; University of Gothenburg: Gothenburg, Sweden, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Eliasson, I.; Fredholm, S.; Knez, I.; Gustavsson, E. The Need to Articulate Historic and Cultural Dimensions of Landscapes in Sustainable Environmental Planning—A Swedish Case Study. Land 2022, 11, 1915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merriam, S.B. Case Study Research in Education. A Qualitative Approach; Jossey-Bass Inc.: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J.W. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches, 5th ed.; SAGE: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, R.K. Case Study Research and Applications: Design and Methods, 6th ed.; SAGE: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Sørensen, M.L.S. Between the Lines and in the Margins: Interviewing People about Attitudes to Heritage and Identity. In Heritage Studies; Routledge: London, UK, 2009; pp. 164–177. [Google Scholar]

- MacTaggart, J.; Gärdefors, B.; Olsson, J.; Crommert, C.G.; Magnusson, H.; Magnusson, B.; Nilsson, L.G. Application to UNESCO, Lake Vänern Archipelago Biosphere Reserve; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- de la Vega-Leinert, A.C.; Nolasco, M.A.; Stoll-Kleemann, S. UNESCO Biosphere Reserves in an Urbanized World. Environ. Sci. Policy Sustain. Dev. 2012, 54, 26–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caballero, G.V.A. The role of natural resources in the historic urban landscape approach. J. Cult. Herit. Manag. Sustain. Dev. 2016, 6, 2–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hockings, M.; Lilley, I.; Matar, D.A.; Dudley, N.; Markham, R. Integrating Science and Local Knowledge to Strengthen Biosphere Reserve Management, 1st ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2020; pp. 241–253. [Google Scholar]

- Roux, D.J.; Kingsford, R.T.; Cook, C.N.; Carruthers, J.; Dickson, K.; Hockings, M. The case for embedding researchers in conservation agencies. Conserv. Biol. 2019, 33, 1266–1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).