Abstract

The creation of outdoor activity spaces in rural communities is an important indicator to enhance the happiness of villagers and an important means to promote rural revitalization through improving the living environment. However, the urbanization trend of spatial forms has caused problems in the construction of many new rural activity spaces, such as the homogenized design and the lack of attention to the real demands of local residents. In order to understand urban-rural differences as well as inter-rural difference of outdoor activity space preferences in today’s China, so as to optimize the planning and design of public space optimization in rural communities, this study took Puxiu and Yuanyi Village in the suburbs of Shanghai as examples, executed field questionnaire surveys to ascertain villagers’ general preferences for outdoor spaces as well as their personal diversities. The results suggested that urban-rural differences were generally reflected in the practicability, economy, rurality, and diversity of the spaces, and it was found that there are significant relationships between residents’ preferences and their personal attributes, such as gender, age, and occupation. Moreover, the essentials for optimizing community activity space design that reflect urban-rural differences as well as the characteristics of different types of villages were also discussed.

1. Introduction

At the start of the new millennium, the rapid development of industrialization and urbanization in China has led to acute changes in the space and function of the countryside. Although the transformation has generally brought about increases in the standard of infrastructure development of the villages and living environment of the residents, the process has also led to negative situations, such as over-urbanization and rural homogenization [1]. In particular, the new rural construction and population transfer brought about by urbanization in the past decade have led to the of economic improvement of rural families as well as population aging. Meanwhile, the changes also produce the increasing demand for public activities, yet the current activity spaces tended to fail to meet the needs of actual rural public life in parallel with the economic and demographic changes and the demand of rural human habitat environment improvement [2,3].

In 2017, China has clearly put forward the national strategy of implementing rural revitalization, which pointed out a new direction for the rural construction. The new rural planning also puts forward the key points for improving rural public spaces, such as the reasonable allocation of public facilities, the balanced layout of each functional space, and the protection of the original style and features of the village. At the same time, the gradual rise of the rural tertiary industry, the return of the urban population, in addition to the re-examination of vernacular culture in academia also bring new opportunities and new demands for the development of rural public activity spaces [4]. As a result, how to create rural community outdoor activity spaces that not only preserve traditional culture and highlight the characteristics of the village, but also meets the villagers’ demands has become a key issue in the sustainable improvement of rural habitat quality.

Domestic and international scholars have also realized this problem. For example, Chen and He pointed out that the design of rural public space should start from respecting the spatial layout of traditional villages, reflecting regional cultural characteristics, protecting villagers’ daily life environment and considering the needs of all groups within society [5,6]. Chang explored the design strategy of an outdoor communication space that is suitable for the rural elderly [7,8]. Liu indicated that the activity forms of individuals, groups, and clusters should correspond to the design of activity fields with different scales and behavioral characteristics of the villagers [9]. Veitch and Li examined the differences in spatial and use characteristics between rural and urban parks [10,11]. Some other scholars have proposed the reshaping of public space with vernacular culture as its core concept [12,13,14,15].

Some sociological scholars further suggested the possibility of optimizing the activity space by the villagers themselves. For example, both domestic and international scholars pointed out that the reconstruction of public space required the bottom-up participation of rural residents [16,17]. Duan proposed to start from villagers’ own behavioral characteristics, take various environmental behavioral psychological factors into consideration when making design strategies [18]. He studied the changes in villagers’ living, production, and consumption patterns, as well as their spatial material and spiritual needs in the context of urbanization, and proposed rural public space planning strategies that can reflect the changes [19]. By observing and summarizing villagers’ behaviors through field surveys, Zhang summarized some Chinese villagers’ custom behavior patterns in public activity spaces [20]. Some international scholars have also examined urban-rural differences in outdoor activities concerning demographic, geographic, environmental, and psychosocial variables [21].

The above studies all agreed that the design of rural activity spaces should respect the spatial behavior characteristics of villagers and found that villagers’ preferences for different types of activity spaces vary from place to place. However, there is still little research on the factors that are causing the diversities, especially concerning the relationship between rural residents’ activity space-use preferences and their personal attributes—among which some could be natural attributes distinguishing the rural area from the urban area, such as age and educational level, while some might reflect the life patterns influenced by the industry type of the specific villages, such as the occupation. This study aims to assess the current usage situation and villagers’ general preferences on outdoor activity space in rural communities of China, using a case study of Puxiu Village and Yuanyi Village in Shanghai as examples. Moreover, relationships between villagers’ own attributes and their space demand preferences were also analyzed in order to further understand the similarities and differences of public activity space demands among different types of villagers and villages, and provide references for the optimal planning and design of outdoor activity space in rural communities.

Finally, a number of former studies have identified the phenomenon that the main users of outdoor public activity spaces in China tended to be the elderly instead of young people, which is quite different from the patterns of western culture [22,23]. Actually, building and improving outdoor activity spaces have been considered as a popular public health policy to keep ageing populations healthy in many places in China, and has been paid special attention in the most aged city in the Chinese mainland—Shanghai, where people over 60 years old accounted for 36.1% of the household registered population in 2020, which is one of the highest levels in the world (in China, age 60, rather than 65 as in most developed countries, is used as a marker of old age). As the population aging degree in rural areas is even higher than it is in urban areas, the findings of this study and the related space optimization strategies could also be helpful to make local elderly people healthy, thus reducing the healthcare cost in rural areas where medical resources are relatively scarce.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Purposes and General Methodolgy

Taking Shanghai as an example, in this study, we planned to conduct a field questionnaire survey to explore the demand for public activity space in rural communities, so as to compare the urban-rural differences, as well as the internal diversities between different types of villages. Considering the demand differences for public activity space in rural and urban communities, questions such as respondents’ hobbies and favorite outdoor activities, current space using status, as well as their preferences for both functional and atheistic designs were designed. Meanwhile, as the population aging rate is generally higher and people’s educational level is generally lower in the countryside, personal attributes of the respondents were recorded and analyses were undertaken to help further the understanding of potential spatial preference trends in rural communities.

On the other hand, regarding the purpose of identifying the demand diversities in different types of villages, we hypothesized that different types of industries in the context of rural revitalization in China could change the lifestyle of local residents, thus influencing their demands for public activity space. Therefore, we conducted pilot surveys in several villages, and finally selected two villages with different types of industries as well as lifestyles as the subjects of the formal investigation. The related personal information, such as the occupation and working status of the respondents, were also expected to be collected. The specific conditions of the two selected villages—Puxiu Village takes tourism as its main industry, and Yuanyi Village that retains farming as its main industry, are as follows.

2.2. Overview of the Surveyed Villages

After the national rural revitalization strategy was put forward, Shanghai has been actively exploring innovative measures for rural revitalization based on the transformation of rural areas towards the tertiary sector. At the same time, there are a large number of villages with rich physical resources, abundant cultural deposits, and rapid industrial development in the surrounding areas of Shanghai.

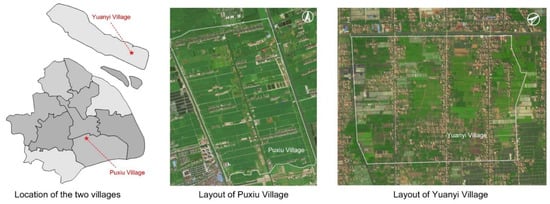

Puxiu Village, located in the northeast corner of Fengxian District, covers an area of 4.6 square kilometers, with agricultural and leisure tourism as its main economic industry, and has an agronomic park for tourists to visit. Yuanyi Village, on the other hand, is located in the Chongming District, with an area of 5.83 square kilometers. More than 80% of the working population there are farmers engaging in planting, modeling, and selling boxwoods, and the boxwood-themed cultural tourism project is also under rapid development (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Location map and layout of Puxiu and Yuanyi village.

Similarities and differences in villages’ conditions were considered when selecting the survey objects for comparative analysis. As shown in Table 1, the similarities of the two villages include the location, development model, and spatial type, and the differences include the housing cluster pattern, production mode, and residential density (Table 1).

Table 1.

Comparison of Puxiu and Yuanyi village.

2.3. Survey Program Design

Considering the high degree of aging and the limited education of the villagers, the questionnaire study was conducted in the form of a one-on-one interview to the respondents, and the answers were recorded by the investigators. The questionnaire was divided into three parts: respondents’ personal information, the current use of outdoor activity space, and preferences for outdoor activity space. The spaces involved here referred to not only the public spaces in the original old village structure, but also the new public activity spaces in the renovation of old villages and the construction of new villages in this century, such as the courtyard space in front of the newly built houses, the waterfront space of the newly renovated river, and the square space in front of the newly built public facilities.

Respondents’ personal information included their basic information, residence status, working status, hobbies, and specialties, aiming to collect personal traits and past experiences that may influence their outdoor activity as well as spatial preferences. The current status of space use included the respondents’ daily activity location, transportation mode, activity contents, number and type of participants, length of stay and frequency of activity, etc. In addition, respondents’ preferences for the outdoor activity space were inquired from six aspects—spatial scale, accessibility, landscape, facilities allocation, environmental comfort and activity contents.

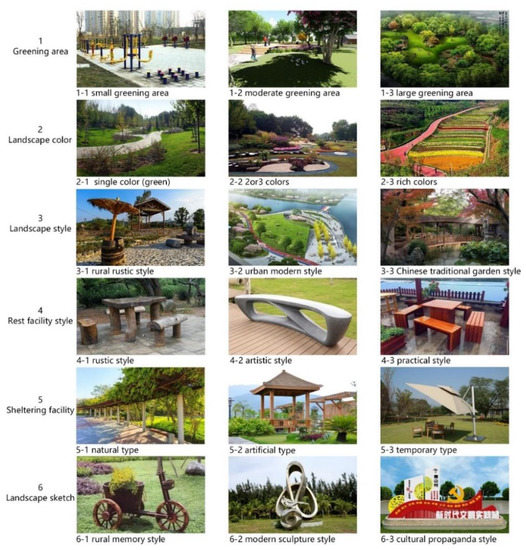

The respondents were selected to cover who lived in different housing clusters, taking into account the diversity of residents in terms of age, gender, health level, and occupation. The personal information and activity status was questioned and recorded by the investigator, while spatial preferences were provided with reference images that matched the written descriptions to deepen the respondents’ understanding of the issues (shown in Appendix A).

A total of 106 valid questionnaires were collected from the interviews, including 42 from Puxiu Village and 64 from Yuanyi Village (Hereinafter referred to simple as P village and Y village). Meanwhile, in addition to the settled questions, during the interview process, the investigator also asked and recorded the reasons for the respondents’ choices and suggestions for optimizing the outdoor activity space.

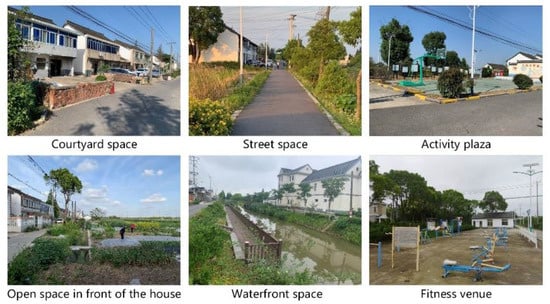

The rural outdoor activity space in this survey referred to the outdoor spaces that can accommodate rural residents for daily interactions, public activities, and leisure activities, including courtyard space, open space in front of the house, street space, waterfront space, activity plaza, and fitness venues, yet excluded spaces mainly used for production activities such as farmland cultivation (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Types of rural outdoor activity spaces.

2.4. Analysis Methods

In the analysis process, we first screened and organized the data, then descriptive statistics to each part of the questionnaire were made to compare the situations of the two villages, as well as clarify the respondents’ general current using situation and preferences for various types of outdoor activity spaces. Moreover, the study tried to explore the relationship between the answers and the respondents’ individual attributes so as to identify the personal diversities in spatial preferences. As the sample size is limited, bar charts were made to illustrate the tendency of choices in a more direct way.

3. Results

3.1. Personal Information of the Respondents

Generally, the respondents in the two villages were similar in age and gender distribution, education level, health status, and occupation (including pre-retirement occupations for the elders), while significantly different in terms of residential status, current working status, and economic status.

All the respondents were over 50 years old, among which 87.74% were over 60 years old. During the 10 times of filed survey, we haven’t encountered any younger residents in the public space during the field investigation time, which included daytime and evening, weekdays, and weekends. The result agreed with the abovementioned phenomenon that elders are generally the prominent user of outdoor public activity spaces in China. Considering the remarkable high proportion of senior space-users in this study, we interviewed some respondents as well as local government officers for the possible reason. According to them, the two villages, just like the majority of the rural communities in China, had a considerable high population aging degree (the over 60-year-old population rate was 41.6% in Puxiu and 43.2% in Yuanyi), thus the number of young residents were limited in number, and the young generations who came to visit their parents would generally stay in their parents’ homes. Meanwhile, according to our former studies in urban communities in Shanghai, the main purpose of younger adults gathering together in public spaces was to have family activities with their children. As there were also not many children in the rural communities today, the driving force for young people to go to public spaces might also be decreased. Moreover, younger adults might be unwilling to have activities together with the crowds of elderly people in public spaces, and such a mutual exclusivity could be reinforced by the considerable ideological differences between young and old in rural areas, thus lessened the outdoor activity spaces use of young generations.

Based on the result, we used three stages to categorize elders’ age according to Forman’s classification [24]: the young old (60 to 69 years), the middle old (70 to 79 years) and the very old (80 years and older) each accounted for 37.74%, 41.51%, and 8.49% of the respondents. Meanwhile, 43.4% of the respondents were male and 56.6% were female. The overall education level was low, with nearly 90% people graduated from junior middle school or below. Moreover, statistics on the health condition of the respondents showed that more than half of them were suffered from chronic diseases (60.38%), among which hypertension and back diseases were the most common ones, followed by leg or brain diseases.

In terms of residence and family structure, most of the respondents were empty-nest elderly, and the top two situations in family structures were living with their spouses (66.04%) and living alone (10.38%), as their children and grandchildren were living in urban areas. While, among the respondents in P village, almost all the younger family members would visit them every weekend, while only 25% of the respondents in Y village had their children visit them once a week, as Y village is far away from downtown.

The occupation composition of the respondents was similar in two villages, with the largest proportion of farmers (66.04%), another 34.91% were mainly workers and service providers, with a few office employees and soldiers. About half of the respondents have already retired and, among those who were still working, half of them were engaged in crop cultivation, and another half were employed by others. For the respondents’ economic circumstances, most of the respondents could obtain about 1000 RMB each month from rural social endowment insurance, and other sources of income included crop cultivation, working outside, or a retirement salary. Since most of the villagers in Y village were still engaged in boxwood cultivation, the overall income level was higher than that of P village. While 33.33% of the respondents in P village were still working, 40.63% of the respondents in Y village were still engaged in boxwood cultivation (Table 2).

Table 2.

Basic information statistics of the respondents.

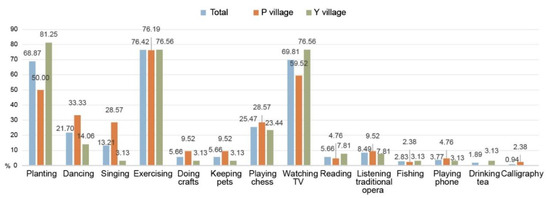

On the other hand, respondents’ hobbies suggested that the most common ones were physical exercising (76.42%), gardening (68.87%), and watching TV (69.81%), followed by chess (25.47%), dancing (21.70%), and singing (13.21%), while other hobbies accounted for no more than 10% of the total. Former studies had found that most common hobbies for urban community residents were watching movies, playing musical instruments, and reading [25], which indicated that compared to urban peers, rural residents were more interested in outdoor recreation, such as exercising and gardening. In comparison, respondents in Y village liked gardening more than those in P village (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Statistics chart of respondents’ hobbies.

3.2. Current Use of Outdoor Activity Space

Different outdoor spaces are suitable for different kinds of activities and understanding the current using status of various types of sites is the basis of spatial optimization [26,27,28]. In this study, more than half of the villagers (57.55%) said they would go to the street and waterfront space most frequently for activities, followed by those who would use personal yards and open spaces in front of their homes (49.06%), while fewer chose to go to the squares. At the same time, there was a significant gap in the choice of respondents from the two villages—more than 60% of the respondents in P village would go to the fitness venue, while the choice of respondents in Y village was the opposite—65.63% of the villagers preferred the personal courtyard and the open space in front of the house.

The daily activities of villagers in the two villages showed that walking and chatting along the streets and waterfront spaces after dinner, along with gardening and chatting in the courtyard and open space in front of the door during free time were the most common outdoor activities of the villagers. According to the interviews, the choice of square depended on whether it is within 15 min walking distance from home. If not, the residents would prefer to gather in the courtyard space or the close waterfront space. If there was a nearby public square, most villagers would go there after dinner to participate in square dancing, use sports and fitness facilities, or sit around and chat. However, very few villagers would be active in the square during the daytime, and only a few elders who have their grandchildren visiting them would go there in the weekend afternoons to play with the kids.

In comparison, villagers in the Y village who were still engaged in agricultural activities tended to prefer activity contents and places that didn’t require a lot of physical strength, and they would prefer to relax and rest through outdoor activities. In addition, since Y village was far from the urban area and the frequency of children’s visiting was lower, the villagers would take care of each other and the neighborhood relationship were closer—specifically, they were more likely to gather on the waterfront terraces or in the courtyards to chat during the day. However, the situation in P village was the opposite—as the villagers had more free time and didn’t have heavy farm work to do, they wanted a higher level physical exertion in outdoor activities. Moreover, compared to the close neighborhood relationship in Y village, residents in P village were more likely to prefer exercising in their own yards or interact only with a few neighbors during the day.

3.3. Preferences for Outdoor Activity Space

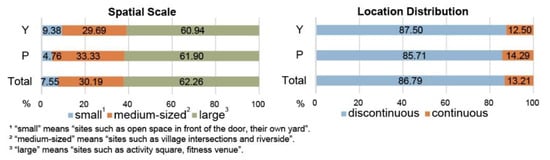

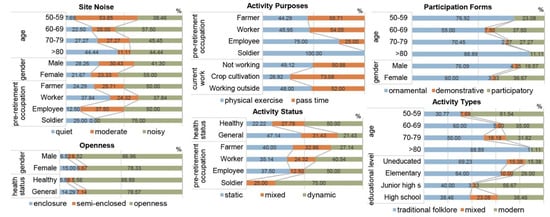

The investigation of spatial scale preferences included site scale and location distribution. In terms of site scale, more than 60% of respondents preferred large activity spaces, such as fitness venues, followed by medium-sized activity spaces, such as street spaces and waterfront spaces. In terms of location distribution, 86.79% of the respondents chose a discontinuous activity space location instead of a continuous one (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Survey statistics of respondents’ spatial scale preferences.

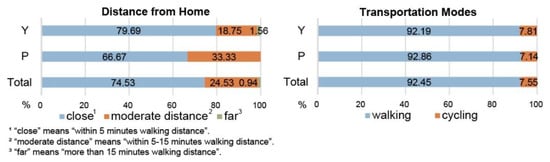

The survey on spatial accessibility preferences included distance from home and transportation modes. As for the distance from home, 74.53% of the respondents wanted the distance to be maintained within a 5-min walk, and the proportion of respondents in Y village who chose the close option was higher than that in P village. Regarding the choice of transportation, the majority of respondents (92.45%) preferred walking (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Survey statistics of respondents’ spatial accessibility preferences.

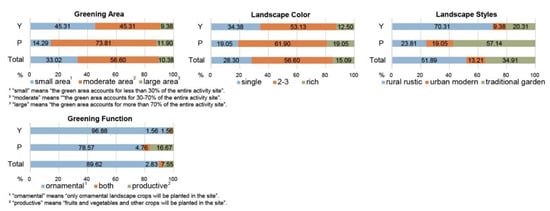

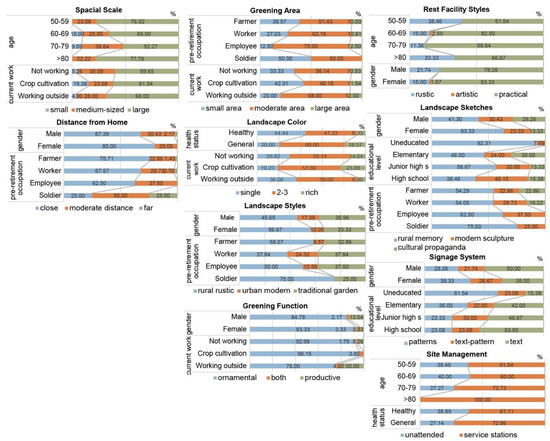

The survey on landscape preferences included greening area, landscape color, landscape styles and function of greening. On the choice of greening area, more than half of the respondents chose the picture of moderate green landscape area, and 33.02% of the respondents wanted a larger area of square for activities; this trend was clearer in Y village (45.31%). In terms of landscape color, 56.60% of respondents chose pictures with 2–3 colors, and nearly 30% chose pictures with all greenery, which was more prevalent in Y village (34.38%). For landscape styles, about half of the respondents chose pictures with a rural rustic style, 34.91% chose a traditional Chinese garden style, and only 13.21% chose a modern style similar to common urban parks. Comparing the results of the two villages, the respondents in P village tended to prefer the Chinese traditional garden style, while those in Y village preferred the rural rustic style. The results of question about the function of greening showed that only 7.55% of the people thought that it was appropriate to have agricultural plantings as landscape which are also productive (Appendix A, Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Survey statistics of respondents’ landscape preferences.

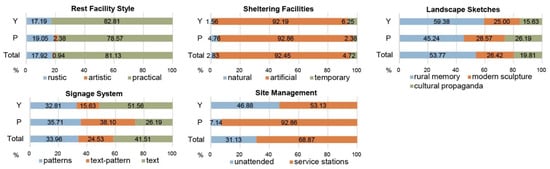

Facilities allocation preferences included the styles of rest facility and sheltering facilities, landscape sketches, signage systems, and site management. In the choice of rest facilities, 81.13% of the respondents chose the image of practical design, and they liked to have enough seats for sitting around. Regarding the preference for sheltering facilities, more than 90% of the respondents chose artificial sheltering facilities, and for the choice of landscape sketches, 53.77% of the respondents chose the rural memory style and 26.42% chose the modern sculpture style. Respondents did not show a significant preference for signage systems, with 33.96%, 24.53%, and 41.51% of respondents choosing patterns, text, and text-pattern mixes designs, respectively. Furthermore, in terms of site management, nearly 70% of the respondents preferred to have security stations or service stations around the activity space (Appendix A, Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Survey statistics of respondents’ facilities allocation preferences.

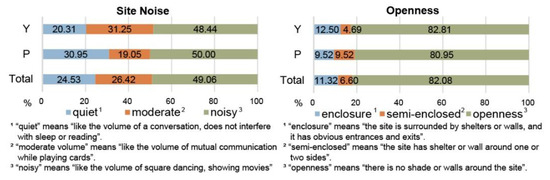

Environmental comfort preference included two aspects: site noise and openness. In terms of venue noise, nearly half of the respondents said they would like the space to be a bit noisy with square dancing or open-air cinema, 26.42% of respondents said they can accept moderate volume of noise, and another 24.53% wanted quiet spaces. In terms of openness, 82.08% of respondents believed that the outdoor activity space was meant to have a sense of openness, and the surrounding area should be free of tall walls (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Survey statistics of respondents’ environmental comfort preferences.

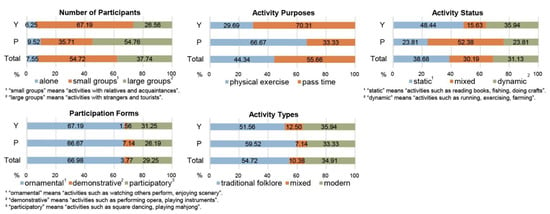

Activity content preferences included 5 aspects: number of participants, activity purposes, activity status, participation forms, and activity types. In terms of activity number, more than half of the villagers preferred to have activities in small groups with relatives or acquaintances, while 37.74% said they would welcome strangers and tourists to join them. Moreover, there was a significant difference in the choice of activity purpose preferences within the two villages—the majority of respondents in P village preferred physical exercise while most respondents in Y village preferred to pass time. Meanwhile, respondents did not have an overwhelming preference for activity status, but there were differences in the two villages as a greater percentage of respondents in Y village preferred static activities such as doing crafts, fishing, and chatting, yet more respondents in P village preferred a mix of static activities with dynamic activities, such as exercising and walking. As for the preference of participation forms, 66.98% of the respondents preferred ornamental activities, such as watching other people’s performances and enjoying the scenery. For the preference of activity types, more than half of the respondents preferred to watch traditional folklore activities such as dragon dance performances, playing with rolling lanterns (a traditional game in the suburbs of Shanghai) and singing mountain songs, while 34.91% of the respondents chose modern activities such as watching movies and performances (Figure 9).

Figure 9.

Survey statistics of respondents’ activity contents preferences.

3.4. Relationship between Spatial Preferences and Personal Attributes

The above questionnaire results generally showed the characteristics of outdoor activity space preferences of rural residents. To further clarify the differences in choices among respondents, this study analyzed the relationship between respondents’ personal attributes and space preferences.

First of all, it was found the preference of site scale and the age of respondents could be related, with middle-aged people under 60 years old and elderly people over 80 years old accounting for the majority of respondents who chose a large site. In addition, the preference of site scale was also influenced by whether the respondents were still working—for those who were not working, they preferred activity sites such as street space and waterfront space for walking and social activities, while those who worked outside preferred large squares.

It was also found that gender had a greater relationship with the choice of distance from home, with males were more likely to prefer activity sites far away, while females preferred to use activity spaces closer to home. Pre-retirement occupation also affected the choice as office employees preferred more distant activity locations than workers and farmers.

In the preference survey about landscape, the current working content and respondents’ pre-retirement occupation had a greater influence on the choice of greening area. Among the respondents who chose the small green landscape area, more people were currently engaged in farming than those who worked outside. Landscape color preference was more influenced by health status and current work content, and among respondents who chose rich colors, those with chronic diseases and those who were engaged in farming were relatively more prevalent. The choice of landscape styles was more related to gender and pre-retirement occupation, as males were more receptive to the modern style than females, while workers and service providers chose the urban modern style and Chinese traditional garden style more than other occupations. Gender and current work content could also influence the greening plant choice, with females and respondents engaged in farming were less receptive to the use of productive agricultural plants for landscape.

The choice of rest facilities design style could be related to age and gender, with respondents under 60 and over 80 preferring the rustic style over other age groups, and females preferring the practical style more than males. The selection of landscape sketches had some relationships with gender and education level, in which females preferred the rustic memory style over males, and respondents with higher education levels preferred the modern sculpture style. Gender and the educational level affected the choice of signage systems style preference, as females and villagers with lower education level were more likely to prefer pattern-based signage systems. The choice of site management could be influenced by age and physical condition—the higher the age and the poorer the physical condition, the respondents would be more likely to have the security and service station (Appendix A, Figure 10).

Figure 10.

Relationship between personal attributes and spatial preferences—part 1.

Preference for site noise was partially related to age, gender, and pre-retirement occupation, with a gradual increase in the preference for quite environments as age increased, and a greater degree of tolerance for noisy environments among females. Among the various types of pre-retirement occupations, workers and service providers had relatively low levels of adaptation to noise. The preference for openness was more related to gender and health status, with female respondents preferring activity sites with a sense of enclosure than males, while preference for enclosure increased as one’s health status decreased.

Concerning the content of activities, the choice of activity purposes was more related to the pre-retirement occupation and current working content, and the respondents’ choice of physical exercise as the activity purpose gradually increased in the order of farmers, workers and service providers, office employees, and soldiers, while the respondents who were currently engaged in farming preferred the activity purpose of passing time than who were not working. The preference for activity status was more related to health status and pre-retirement occupation, with villagers in poor physical condition and those who were manual laborers preferring static activities. The choice of the participation forms was strongly influenced by gender and age group, with females preferring participatory activities, yet males preferring demonstrative and ornamental types of activities. Meanwhile, as the age increased, the elderly became less enthusiastic about participatory activities and preferred ornamental activities instead. Finally, the choice of activity types had a relationship with age group and education level, in which younger respondent had higher inclination for modernized activities, and respondents over the age of 80 preferred traditional folklore activities. In addition, respondents with lower education level also showed greater interest in activities of traditional folklore (Figure 11).

Figure 11.

Relationship between personal attributes and spatial preferences—part 2.

4. Discussion

4.1. Urban-Rural Differences in Outdoor Activity Space Preferences

As former studies pointed out, the urbanization of spatial forms in the construction of many new rural activity spaces had led to a significant decrease in villagers’ sense of identity and their frequency of space use [29]. Therefore, exploring the urban-rural differences in outdoor activity space preferences could be helpful to the optimization of rural outdoor activity spaces. Comparing the findings in 3.3 with previous studies on urban outdoor activity spaces, it was found that urban-rural differences were generally reflected in the practicability, economy, rurality, and diversity of the spaces, while the degree of importance of these four factors was closely related to the personal attributes of the villagers.

Firstly, in terms of practicability, with generally better material living standards, many urban residents wanted the outdoor space to meeting their spiritual needs. As a result, they tended to care more about the improvement of the spatial aesthetics, such as adding more landscape sketches or art installations, and increasing spaces for cultural displays and communication [30,31]. However, the results of this survey suggested that, concerning public activity space, residents in rural areas still regarded whether the space could meet their physiological needs as the highest priority. For example, in the choice of rest facilities, they would first consider whether the number of seats was adequate, rather than whether the form of the seats was aesthetically pleasing. They also wanted the seats to be able to have a backrest to support the upper body, thereby reducing back pain arising from agricultural activities. When choosing a shelter, the first consideration was whether it could meet the needs of both sun and rain shade and whether it was easy to maintain, rather than whether the shelter was compatible with the village environment. In addition, when choosing the signage systems, they would consider whether it was clear and easy to understand, rather than whether the design was unique and innovative.

In terms of economy, most villagers considered more about saving money due to their frugal habits, as well as the fact that they might have to rely on themselves rather than professional organizations for facility maintenance and management in the future. For example, when choosing the landscape design styles, although most people said that Chinese traditional gardens were aesthetically pleasing and suitable to the environment, they might still choose a vernacular landscape design style due to its lower cost. On the other hand, regarding landscape plants, most villagers didn’t choose agricultural plants; considering that the ownership of the production could lead to neighborhood conflicts, they preferred non-productivism leisure landscape [32,33].

Rusticity meant that the rural residents preferred activity spaces with rural cultural characteristics compared to a sense of urbanized and modernized space design, which were formed by the visual memory of rural communities accumulated through time [34]. For example, when choosing landscape design styles and landscape sketches, villagers preferred options with rural cultural elements. Regarding the activity contents, they also preferred traditional folklore activities so as to awaken memories of the past and enhance the sense of belonging. Furthermore, the social communication function carried by the place also had a strong rural characteristic—in contrast to the design of public spaces in urban areas that are intended to promote communication between strangers [35], the social network of the “acquaintance society” is naturally stronger in rural societies, thus people there preferred a more suitable place for communication and activities between acquaintances [34]. In this survey, most of the villagers knew each other and had good neighborhood relationships, so they were very active in having activities together; no matter whether it was in the courtyard, roadside, or public square, there would always be many villagers gathering together and communicating with each other.

In studies on urban space, scholars have already pointed out the importance of spatial diversity, such as Jane Jacobs’ theory of urban diversity, which summarized that people were the core to shape various urban space. In the rural environment, the case was the same as spatial diversity was reflected in the space and activity choices of individuals. For example, people would choose different forms of sites according to the activity contents; regarding the activity types, they would take their physical condition and physical strength left after labor work into consideration; concerning participation forms, they would choose ornamental or performance activities according to their personality characteristics.

4.2. Influence of Individual Attributes on Activity Space Preference

In order to avoid homogenized environmental design, when planning and designing outdoor activity spaces in villages, in addition to the urban-rural differences, the influence of villagers’ personal attributes on spatial preferences should also be taken into account. Meanwhile, through the joint participation of designers and villagers, a better combination of “top-down” and “bottom-up” might be achieved [36].

For example, according to the results of the relationship analysis, it was found that age could affect the choice of preferences for site scale, rest facilities, site management, site noise, participation forms, and activity types greatly. For example, in the process of ageing, some seniors experienced the loss of their spouse or the departure of children; thus, their family structure gradually became more homogeneous, yet the need for socialization became greater and they were more inclined to participate in activities with a larger number of people. Moreover, due to the accumulation of time living in the village, the elderly people’s sense of belonging was strong, which might lead to their preference for traditional activities [37].

Gender, on the other hand, might influence the preferences for spatial distance from home, landscape styles, as well as rest facility styles and forms of participation. In general, previous research has indicated that since females in traditional rural societies were responsible for activities within the family, while males were responsible for activities such as working outside and farming, a different scope of life and psychological needs might thus be generated [38,39,40]. Generally, females were more socially oriented and preferred collective activities such as square dancing or doing crafts, so they had a higher preference for large squares and more seats. Males, however, were more interested in personal activities or activities individually or in small groups, and they also preferred competitive activities such as fishing and sports.

Educational level attributes tended to influence villagers’ choices of landscape sketches, signage systems, types of activities, etc. As education could affected one’s aesthetic tastes and comprehension abilities, people with higher levels of education would be more likely to appreciate abstract designs and like modern and new activities.

Finally, health status could influence the preferences for landscape color, site management, sense of openness, and activity status. Residents with poorer health preferred activity spaces with a sense of safety, such as activity spaces with a certain extent of enclosure. Meanwhile, since those people may not be able to participate in activities that consumed physical strength, they tended to acquire information through watching. On the other hand, as their cognitive ability gradually declined, their recognition of space and color also decreased, thus rich colors and forms could better stimulate their cognitive ability and attract their attention.

4.3. Spatial Design That Reflected the Characteristics of Different Types of Villages

Past experiences and current situation of people would influence their aesthetic and activity preferences, thus influencing their choice of outdoor activity space. Each village also had its unique preference characteristics because of its distinctive history, cultural tradition, and industrial content. In this survey, the differences between the respondents from the two villages were mainly reflected in two aspects—occupations and working contents—which were influenced by the location and industry of the villages.

Compared with P village, Y village is farther away from the urban center, and a relatively large proportion of the old villagers were former farmers, workers, and service providers, while a relatively small proportion of them have worked in institutions or companies. According to the survey, pre-retirement occupational attributes could affect the spatial preferences such as landscape styles, site noise, activity purposes, and activity status. It indicated that a person’s previous occupation could affect their sense of aesthetics—those who have worked in an urban area were more likely to prefer urban-style landscapes and activities [36,41,42]. At the same time, villagers who were mental labors tended to prefer complex activity content, while those engaged in agricultural activities liked simpler activities more. In addition, villagers engaged in farming would be more likely to consider the act of cultivating plants as a means to earning life, so they might pay extra attention to the issue of crop ownership, thus rejecting the use of productive landscape plants, which suggested that some kind of plants adopted in urban activity spaces might not be that applicable for use in rural public areas.

Although there was a large amount of farmland in both villages, the farmland in P village was under the collective contract system and managed by the village government, while the farmland in Y village was contracted to individuals, and most villagers were still engaged in farming. This difference in current working content could influence the preference of site scale, landscape color, activity content, etc. In general, people tended to prefer outdoor spaces that were distinct from their working environment, so that they could enjoy their activities in a more relaxed manner, while avoiding aesthetic fatigue [26]. The degree of physical exertion from work also affected their choice of activity content and site—villagers who were still engaged in manual works preferred activities that didn’t consume physical and mental energy and needed more rest facilities in the outdoor spaces. Yet, villagers who were not working had more time and energy for outdoor exercises, thus expecting various activity content and larger space.

In addition, although we supposed that there might be conflicts between the development of rural tourism and the original needs of rural life, the result also suggested that the spatial demands of rural residents might change with the development of tourism, thus reconciling the conflicts. For example, the survey found that if the villagers were engaged in service industry works rather than farming, a desire for having leisure activities and sports instead of just resting could be enhanced, which agrees with the spatial demands of visitors from urban areas. Therefore, in these villages, plazas and sport venues could be planned to meet the needs of both the residents and visitors. Yet in villages where agriculture was the main industry, the situation could be different.

In summary, differences in occupations and working content could shape the differences in aesthetic and activity preferences between P village and Y village. The result indicated that when planning an activity site, the designers might take the characteristics of the villagers into consideration and evaluate the demands of the residents in advance. For example, for people in Y villages who had a lack of physical strength due to farming and were less receptive to urban elements, the activity space might be arranged as a small-scale site with rich rest facilities and the visual characteristics of rusticity. For the P village, which was developing rural tourism, plazas and sports grounds with multi-functionality might be introduced to meet the exercising demands of the residents and attract tourists, thus promoting the coexistence of the rural tourism industry and the original village life.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, along with the proposed strategy of rural revitalization and improvement of rural habitat environment quality, the design of outdoor activity space in rural communities is attracting more and more attention. However, it is currently facing problems, such as the homogenized design and the lack of attention to the real demands of local residents. Meanwhile, the urbanization trend of spatial forms has caused problems in the construction of many new rural activity spaces, leading to a significant decrease in villagers’ sense of identity and active use of space. Furthermore, the villagers, as the main users of the rural public space, were one of the essential elements concerning the direction of outdoor activity space optimization, but in China’s current rural community design, a human-centered approach to public space design was still lacking. This study recorded the using status of outdoor activity spaces in two villages around Shanghai through field surveys and analyzed the space-using preferences of the villagers. The result suggested that the demands of activity space of the countryside were significantly different from those of the city. To be specific, villagers would pay more attention to the practicality and cost-saving of the activity space and facilities, and they preferred rustic elements in aesthetics and have great diversities in personal choices of space and activities. It was also found that the personal choices of residents’ preferences could be influenced by their personal attributes such as gender, age, and occupation. On this basis, urban-rural differences in outdoor activity space preferences were discussed, and spatial design strategies reflecting the characteristics of the villages as well as varieties of the residents were proposed.

The findings of the study could serve as a reference for the optimization of public space in rural communities, and the suggested strategies regarding the joint participation of designers and villagers might be helpful to make a better combination of “top-down” and “bottom-up” planning in the practical works. To be specific, the study results might help to make the relevant design in villages fit better to the real demands of local residents, improve the social and economic benefits of the construction investment, and promote the overall human living environment quality—especially for older adults, who were the main users of public activity spaces as well as the group of people needing especial attention regarding the remarkably high population aging level in rural communities.

On the other hand, the study also has considerable limitations. Firstly, because of COVID-19 and travel policy restrictions, the field investigations have limitations in terms of the number and scope of the survey sample. Meanwhile, the two villages in the study were selected to demonstrate that people living in different villages under industrial transformation could have different demands for public activity space due to different life styles, but they might not be representative of the whole condition in rural China. Moreover, the findings generally reflected the demands of the older generation of local residents. Although the younger generations tended to be less active in using community public spaces, their demands should be also studied in the future so as to create attractive public spaces that could help to promote cross-generational communication. Therefore, we would like to expand the types of villages and the sample size of investigation and questionnaire in a future study and verify the effect of relevant spatial optimization methods in practice, so as to provide more evidence-based references for the planning and design of outdoor activity spaces in China’s rural communities.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.W. and L.S.; methodology, L.W. and L.S.; software, L.W.; validation, L.W.; formal analysis, L.W. and L.S.; investigation, L.W.; resources, L.W. and L.S.; data curation, L.W.; writing—original draft preparation, L.W.; writing—review and editing, L.W. and L.S.; visualization, L.W.; supervision, L.S.; project administration, L.S.; funding acquisition, L.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The research was funded by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (Grant No. 2019YFD1100803), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 52078344), and the National Social Science Fund of China (Grant No. 21ZDA107).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

First of all, we are very grateful to the local community for their support and participation in this research. Their knowledge is the soul of this paper. We also want to thank all experts and editors who reviewed the paper after its completion.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Figure A1.

Images used in the questionnaire to illustrate the options to the villagers.

References

- Yang, R.; Liu, Y.S.; Long, H.L.; Zhang, Y.J. Research progress and prospect of rural transformation and reconstruction in China: Paradigms and main content. Prog. Geogr. 2015, 34, 1019–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Wang, X.Y.; Deng, R.N. Research on the environmental design of public space under the construction of beautiful countryside. Hebei Enterp. 2019, 31, 72–73. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, H.; Weng, D.; Liu, H. Decoding Rural Space Reconstruction Using an Actor-Network Methodological Approach: A Case Study from the Yangtze River Delta. Land 2021, 10, 1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L. Study on the Design of Village Public Space Based on Rural Characteristics—Taking Yinzi Village of Rongcheng as an example. Master’s Thesis, Shandong Jianzhu University, Jinan, China, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y. Research on Public Space Design of New Rural in Handan Area. Master’s Thesis, Hebei University of Engineering, Handan, China, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- He, Y. The practice and experience based on the construction of public space and facility. Arch. Tech. 2017, 37, 68–71. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, G.H. Study on the Space Design of Outdoor Communication Facilities in Rural. Master’s Thesis, Zhongyuan University of Technology, Zhengzhou, China, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, S.; Li, T.S.; Li, J.J.; Zeng, X.L. Talking about the design of outdoor activity space for the left-behind elderly in the context of new rural construction. Contemp. Hortic. 2020, 43, 157–159. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Wu, H.M. Discussion on the New Mode of Rural Endowment for the Aged—Behavioral Characteristics Define the Design Technique of Public Space Classification. Jiangsu Constr. 2019, 39, 92–96. [Google Scholar]

- Veitch, J.; Salmon, J.; Ball, K.; Crawford, D.; Timperio, A. Do features of public open spaces vary between urban and rural areas. Prev. Med. 2013, 56, 107–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Fang, Z.Y.; Yin, L.D. Northern Rural Areas Public Activity Space Aging Research. Arch. Cult. 2016, 13, 180–181. [Google Scholar]

- Dai, Y.M. Design of rural public space regeneration—A case of public space regeneration in wuhan city yushan village. Design 2016, 21, 158–160. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, Y.; Liang, K. Analysis and optimal design of new rural public space in Jiangxi region. Constr. Mater. Decor. 2018, 37, 80–81. [Google Scholar]

- Oyang, C.Y. Research on Public Space Construction of New Rural Communities in Chengdu Based on Local Culture. Master’s Thesis, Southwest Jiaotong University, Chengdu, China, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Gong, Y.Q.; Ma, J.W.; Liu, M.H.; Jiang, X.Q.; Yang, Q. Design of Rural Public Space Based on Humanistic Feelings—A Case of Yinshan Village in Jinting Town. Suzhou Urban. Arch. 2019, 16, 7–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y. Study on the Status and Reconstruction of Public Space in the New Rural Construction—Taking Ningbo Zoumatang as an Example. Sci. Technol. Inf. 2011, 28, 433–434. [Google Scholar]

- Parks, S.E.; Housemann, R.A.; Brownson, R.C. Differential correlates of physical activity in urban and rural adults of various socioeconomic backgrounds in the United States. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2003, 57, 29–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duan, C.; Dong, L. Studies on Outdoor Leisure Space and Elements in Rural Communities. Hubei Agric. Sci. 2015, 54, 4756–4760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, H.; Wang, B.; Li, M. Study on Rural Public Space Planning in Response to Lifestyle Changes: A Case Study of Beautiful Village Planning in Guiba Village. In Proceedings of the Annual China Urban Planning Conference, Shenyang, China, 24–26 September 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H.; Zhang, Z.Q. Investigation and Analysis of the Rural Public Space Activities under the Background of Rural Rejuvenation—A Case Study of Nanao Village, Zhoushan. Chin. Overseas Arch. 2018, 24, 139–142. [Google Scholar]

- Jaszczak, A.; Žukovskis, J.; Antolak, M. The role of rural renewal program in planning of the village public spaces: Systematic approach. Manag. Theory Stud. Rural. Bus. Infrastruct. Dev. 2017, 39, 432–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Tian, Y.; Du, M.; Hong, B.; Lin, B. How to design comfortable open spaces for the elderly? Implications of their thermal perceptions in an urban park. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 768, 144985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.; Li, Y. Understanding leisure satisfaction of Chinese seniors: Human capital, family capital, and community capital. J. Chin. Sociol. 2019, 6, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forman, D.E.; Berman, A.D.; McCabe, C.H.; Baim, D.S.; Wei, J.Y. PTCA in the elderly: The “young-old” versus the “old-old”. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 1992, 40, 19–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.Y. Study on the Relationship Between the Elderly Behavioral Psychology and Public Space Privacy in Community—A Case of Minxin Community in Shanghai. Urban. Arch. 2021, 18, 164–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalif, M.; Dharmowijoyo, D. Individuals’ activity space in Seri Iskandar Malaysia. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Env. Sci. 2020, 419, 012004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schönfelder, S.; Axhausen, K.W. Activity spaces: Measures of social exclusion? Transp. Policy 2003, 10, 273–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dharmowijoyo, D.B.; Susilo, Y.O.; Karlström, A. Day-to-day interpersonal and intrapersonal variability of individuals’ activity spaces in a developing country Environment and Planning B. Plann. Des. 2014, 41, 1063–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Q.L. Reconstruction of Public Spaces of New Rural Community Based on Peasant Households Perspective. Master’s Thesis, Southwest University, Chongqing, China, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Zi, Y.F.; Yang, Y.; Li, Y.S. Research on the Healthy Promotion of Community Public Space in Qingdao under the Background of Quality Improvement. Urban. Arch. 2021, 18, 46–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y. Research on the Interaction of Community Public Space Based on Sustainable Concept. Master’s Thesis, North China University of Technology, Beijing, China, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, C.J.A. Entrepreneurialism, commodification and creative destruction: A model of post-modern community development. Rural Stud. 1998, 14, 273–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.; Kong, X. Tourism-led Commodification of Place and Rural Transformation Development: A Case Study of Xixinan Village, Huangshan. Land 2021, 10, 694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, H.L. The Evolution of Village Public Space and Its Significance for the Reconstruction of Village Order—A Concurrent Discussion on the Generative Logic of Village Order in Social Change. Tianjin Soc. Sci. 2005, 25, 61–65. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, Q. Exploring the planning and design of public space in urban communities. City House 2021, 28, 126–127. [Google Scholar]

- Xi, X.; Xu, H.; Zhao, Q.; Zhao, G. Making Rural Micro-Regeneration Strategies Based on Resident Perceptions and Preferences for Traditional Village Conservation and Development: The Case of Huangshan Village, China. Land 2021, 10, 718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nchuchuwe, F.F.; Adejuwon, K.D. The Challenges of Agriculture and Rural Development in Africa: The Case of Nigeria. Acad. Res. Prog. Educ. Dev. 2012, 1, 45–61. [Google Scholar]

- Gallina, M.; Williams, A. Perceptions of Air Quality and Sense of Place among Women in Northeast Hamilton, Ontario. Soc. Sci. Stud. 2014, 2, 67–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allendorf, T.D.; Yang, J.M. Development; Sustainability, The role of gender in local residents’ relationships with Gaoligongshan Nature Reserve, Yunnan. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2017, 19, 185–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soini, K.; Vaarala, H.; Pouta, E. Residents’ sense of place and landscape perceptions at the rural-urban interface. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2012, 104, 124–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Zhao, G.; Fagerholm, N.; Primdahl, J.; Plieninger, T. Participatory mapping of cultural ecosystem services for landscape corridor planning: A case study of the Silk Roads corridor in Zhangye. Environ. J. Environ. Manag. 2020, 264, 110458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, M.; Yang, Y.; Chen, F.; Zhu, F.; Qu, J.; Zhang, S. Response of agricultural multifunctionality to farmland loss under rapidly urbanizing processes in Yangtze River Delta. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 666, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).