Abstract

This work aims to review the natural communities of Pinus halepensis in Spain. The methodology consisted of subjecting 400 phytosociological relevés to georeferencing and statistical, biogeographical, and bioclimatic treatment. We analyse the communities of Pinus halepensis on the Iberian Peninsula and Balearic Islands. Five syntaxa with association rank are described in several works and included in the alliances Rhamno-Quercion and Oleo-Ceratonion. Ephedro-Pinetum halepensis was initially proposed as a community by Torres et al. and subsequently raised to the rank of association by Rivas-Martínez et al. In this work, we have separated the plant communities dominated by Pinus halepensis, which was previously included in other syntaxa, and as a result, we propose four new associations and a new alliance for the Iberian Peninsula: ass. Bupleuro rigidi-Pinetum halepensis; ass. Ephedro nebrodensis-Pinetum halepensis; ass. Rhamno angustifoliae-Pinetum halepènsis; ass. Rhamno laderoi-Pinetum halepensis; all. Rhamno lycioidis-Pinion halepensis. In view of the fact that some of the communities have been published as edaphoxerophilous and climatophilous, we suggest separating the climatophilous from the edaphoxerophilous character in the diagnosis of the communities, and have therefore recently proposed the ombroedaphoxeric index Ioex (Ioex = Pp − e/Tp × CR), which considers positive precipitation Pp, positive temperature Tp, residual evapotranspiration (e), and water retention capacity CR (0.25, 0.50, 0.75). In conclusion, we propose the associations mentioned above, which will allow the implementation of a reforestation treatment in accordance with the natural environment.

1. Introduction

The genus Pinus L. is widely distributed on the Iberian Peninsula in the form of autochthonous and introduced species [1]. Flora Ibérica lists seven species of pine, of which five can be considered autochthonous, and two are here introduced [1]. The autochthonous species are Pinus pinaster Aiton, Pinus nigra Arnold subsp. salzmannii (Dumal) Franco, Pinus nigra Arnold var. latisquama (Willk.) Heywood, Pinus sylvestris L., Pinus uncinata Ramond ex DC, Pinus halepensis Mill. The introduced species are Pinus pinea L. and Pinus radiata D. Don.

P. pinea has been considered an introduced species from the phytosociological point of view and has been used in reforestation and neglected by phytosociology; between 1940 and 1985, three million hectares of P. pinea were repopulated in Spain. Several works mention this pine as an introduced plant in the eastern Mediterranean [2,3]; however, Postigo-Mijarra et al. [4] indicate the presence of pollens in sediments in Huelva at a depth of 10.5 m, together with holm oak, rock rose, and heaths.

Fiori [5] states that this pine tree is present in large parts of Italy, and Conti et al. [6] give P. pinea as an exotic plant naturalized in Italy. Bartolucci et al. [7] and Galasso et al. [8] include P. pinea as an archaeophyte flora naturalised in Italy. However, Amaral Franco [1] states its distribution being in southern Europe, western Asia, and frequently in the centre-east and south of the Iberian Peninsula, although with a doubtful autochthonous character, as it is a cultivated species in a large part of the Iberian Peninsula. There is some controversy as to the autochthonous character of Pinus pinea, pointing to the need for future research on this species.

We studied the forests of P. halepensis as natural formations in Spain [9]. According to Amaral Franco [1], P. halepensis has a Mediterranean distribution in the eastern half of the Iberian Peninsula and the Balearic Islands, with P. halepensis var. ceciliae in this latter location. It is cultivated and sub-spontaneous in the CW of Portugal; Maire [10] reports that the Aleppo pine forms forests on semiarid hillsides in a large part of the eastern Mediterranean, but without extending as far as the southern mountains of the Rif, and we cite it in the mountains of Palestine [11]. Quezel et al. [12] report the presence of Coronillo valentinae-Pinetum halepensis Quezel, Barbero, Benabid & Rivas-Martínez 1992, and the association Bupleuro gibraltarici-Pinetum halepensis Tregubov 1963 in eastern Morocco. These associations may also include the species Quercus rotundifolia, Q. coccifera, Arbutus unedo, Viburnum tinus, and Tetraclinis articulata, which implies at least a dry ombrotype; these are therefore edaphoxerophilous formations. Paleobotanical research is conclusive regarding the natural character of the species in Spain, as studies of the fossil record over the last 15,000 years and carbon studies offer evidence of the autochthonous and Iberian character of P. halepensis [13,14,15,16,17].

P. halepensis is a tree that prefers limey soils and is widely distributed throughout the Mediterranean—generally circum-Mediterranean—region, not usually above 800 m (except in some parts of North Africa where it may extend to 2000 m asl.) in Spain, the Balearic Islands, and the eastern half of the Iberian Peninsula. However, throughout the 20th century, there has been some debate about the autochthonous character of this pine on the Iberian Peninsula. In our previous works [9], we demonstrated the autochthonous character of the species and established its area of Mediterranean distribution. Igbareyeh et al. [11] described the forests of Pinus halepensis in Palestine, and Rivas-Martínez et al. [18] subsequently established several plant formations in the east of the Iberian Peninsula and the Balearics. Recently, Pesaresi et al. described several Pinus halepensis communities in the Mediterranean [19]. P. halepensis is a tree with an average height of 12–14 m, generally with an umbrella form. Torres et al. [9] and Bucci et al. [20] state that this species is ecologically and genetically very close to P. brutia, and both species form a clearly defined group that is widespread throughout the western Mediterranean. However, the two species do not usually coexist, and if they do, as occurs in Greece, Anatolia, and Lebanon, they tend to form natural hybrids [21]. P. brutia is distributed in the eastern Mediterranean and has its optimum in the Greek islands of the Aegean, Cyprus, and areas of northeast Greece, Turkey, Syria, and Lebanon without extending as far as Palestine [4]. According to Fiori [5], P. brutia Ten is distributed in Crete, Cyprus, and Afghanistan. Farjon [22] expands the previous area of distribution to Armenia, Azerbaijan, Georgia, and Ukraine

According to our research and that of other authors such as Rivas-Martínez et al. [18], P. halepensis on the Iberian Peninsula is distributed in the pluviseasonal-oceanic Mediterranean, pluviseasonal-continental Mediterranean, and xeric-oceanic Mediterranean, and the determining factors for its distribution are temperature, soil, and ombroclimate. It is located in thermo- and mesomediterranean thermotypes and ombrotypes that range from the semiarid to the subhumid, where it coexists with kermes oak and mastic woodlands [23].

Because of the controversial status of Pinus halepensis communities in Spain in terms of their autochthonous or introduced character, since we previously demonstrated [9] that Pinus halepensis is an autochthonous species, as recognized by Rivas-Martínez et al. [18], and since this species is widely used in reforestation in Spain, we set ourselves the objective of reviewing the natural communities of this species. We maintain the hypothesis that the ombrotype, with an influence of the substrate, is the cause of the ambivalent character of Pinus halepensis, which may have an edaphoxerophilous or climatophilous character, as demonstrated by applying the ombroedaphoxeric index.

2. Materials and Methods

Initially, 400 phytosociological relevés were obtained from the various plant communities on the Iberian Peninsula in which Pinus halepensis has appeared with varying degrees of frequency without any distinction between climatophilic or edaphophilic plant communities. We have used our own relevés and those from various published works [9,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41]. In this study, we analyse relevés from the associations described for P. halepensis and those included in other associations, but which have a dominance of P. halepensis, such as the relevés adscribed initially to Rhamno lycioidis-Quercetum cocciferae.

All vegetation relevés were collected following the Braun-Blanquet methodology [26], establishing the concept of minimum area for sampling this type of tree formation. The method basically consists of sampling homogeneous plots of vegetation from the physiognomic point of view and estimating the dominance/abundance of each taxon based on the Braun-Blanquet indices. The sampling area of each relevé or plot was 300 m2, largely coinciding with that proposed in the Braun-Blanquet methodology, discarding any relevés whose areas were not between 250–350 m2. Other vegetation relevés were discarded because they were repopulations or forestry crops.

The first step was the georeferencing and implementation in a Geographic Information System (GIS), which subsequently allows each vegetation relevé to be associated with other topographic data such as slope, orientation, and biogeographic or bioclimatic information. This establishes a first filter with which to discard any relevés from reforestation, or in which the surrounding vegetation does not correspond to a forest of Pinus halepensis.

The selected relevés were georeferenced with a maximum error of 100 m2 in 100 × 100 squares. After the database had been created, the geographic variables for orientation and slope for each relevé were obtained from a digital terrain model of the Iberian Peninsula with a resolution of 25 m. The climate variables for maximum, minimum, and mean monthly temperature and mean monthly precipitation were obtained for each sampling point from 4987 meteorological stations distributed around the Iberian Peninsula and North Africa by means of neural network-assisted interpolation using the neural software in the Decision Tools package.

With this preliminary information, a database was created with the geographic, climate, and bioclimatic variables for each georeferenced relevé.

Before conducting any statistical or ordination analysis, the climatic, geographic, and bioclimatic data were normalised according to the following formula:

where X is the value of the variable, µ is the mean of the variable, and is the standard deviation of the variable.

A factor analysis was done after normalising the data in Table 1. Factor analysis is one of the series of multi-variable analytical methods for studying the relations of interdependence that occur between a set of variables or individuals. The criterion for choosing the bioclimatic variables was selected after rotating the table of factors with the VARIMAX algorithm, which transforms the initial factor matrix into a rotated factor matrix to make it easier to interpret. This procedure was followed only for the bioclimatic variables. The bioclimatic variables selected correlated with the factors of over 90%.

Table 1.

Correlation between the climatic and bioclimatic variables with the two first rotated factors. (MAX = Mean maximum temperature of each month, MED = Mean temperature of each month, MIN = Mean minimum temperature of each month, PE = Thornthwaite annual potential evapotranspiration index, PE = Thornthwaite annual potential evapotranspiration index for February, PRE = Precipitation, Psw = Precipitation of the coldest semester of the year, Pw = Precipitation of the winter quarter, T = Mean annual temperature, Tmax = Mean annual maximum temperature, Tpw = positive temperature of the coldest four-month period, Tpw1 = positive temperature of the coldest month, Tpw2 = positive temperature of the two coldest months, Ts = mean summer temperature, Ts2 = mean temperature of the two warmest summer months, Itc = compensated thermicity index.

For the biogeographical location of the relevés, we follow Rivas Martínez et al. [42] at the province, sector, and biogeographical district level, and prepare the indices Ic, Io, It/Itc for the bioclimatic analysis [43].

An ordination analysis is applied to the selected variables (biogeography, bioclimatology, topography, plant composition), using the statistical packages CAP (Community Analysis Package III) and Past (PAleontological STatistics) to prepare a hierarchical classification dendrogram of the relevés. This cluster dendrogram was created based on the Kendall distance (which is not a parametric test and is therefore robust to the distribution of the data), and the classification was performed with the complete linkage clustering method. A multivariate analysis was then applied using DCA (Detrended Correspondence Analysis) to classify the relevés. The different alliances were separated with a comparative floristic analysis. We consulted Rivas Martínez et al. [18] to choose species used as characteristic of the alliance for the Iberian Peninsula.

To determine whether there are bioclimatic differences between the different Pinus halepensis communities, the values of the bioclimatic indices previously selected from the VARIMAX analysis were statistically analysed by comparing them (Table 1). An exploratory data analysis and the Shapiro-Wilks normality test were carried out beforehand. Due to the nature of targeted sampling, our data do not follow a normal distribution, so non-parametric analyses were applied. In this case, the Kruskal-Wallis test was applied to determine the existence of any bioclimatic differences between the different associations, and the Connover-Iman test to identify which associations of these bio-climatic differences exist and in which variable. The phytosociological nomenclature code of Theurillat et al. was used for the proposal of new syntaxa [44] (articles 3, 10, 17, 27, and 39 ICPN)

3. Results

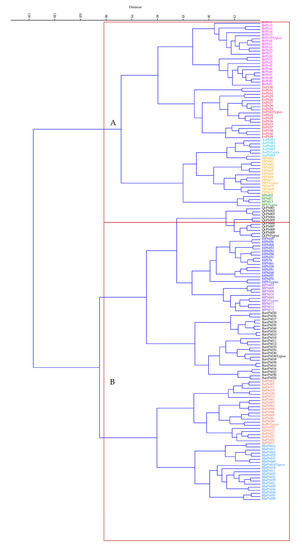

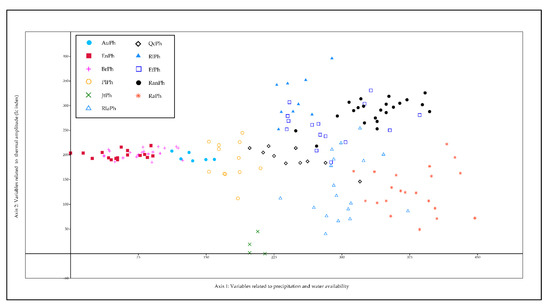

We conducted a syntaxonomic review of the Pinus halepensis communities in the Iberian Peninsula using statistical analysis (cluster and DCA) (Figure 1A,B and Figure 2) and ecological, biogeographical, bioclimatic, and floristic analysis, which allows us to propose several new syntaxa.

Figure 1.

Cluster analysis of Pinus halepensis Mill. relevés corresponding to the associations in the study. (A) Associations in the north-east of the Iberian Peninsula: BrPh = Bupleuro rigidi-Pinetum halepensis, EnPh = Ephedro nebrodensis-Pinetum halepensis, AuPh = Arbuto unedi-Pinetum halepensis, PlPh = Pistacio lentisci-Pinetum halepensis (= Ceratonio siliquae-Pinetum halepensis), JtPh = Junipero turbinatae-Pinetum halepensis. (B) QcPh = Querco cocciferae-Pinetum halepensis; EfPh = Ephedro fragilis-Pinetum halepensis; RlPh = Rhamno lycioidis-Pinetum halepensis; RlaPh = Rhamno laderoi-Pinetum halepensis; RanPh = Rhamno angustifoliae-Pinetum halepensis; RaPh = Rhamno almeriensis-Pinetum halepensis.

Figure 2.

DCA analysis of Pinus halepensis Mill. communities on the Iberian Peninsula.

Five syntaxa with association rank are described in several works and included in the alliances Rhamno-Quercion and Oleo-Ceratonion. Ephedro-Pinetum halepensis was initially proposed as a community by ourselves and subsequently raised to association rank by Rivas Martínez et al. [18]. It was described as the head of the semiarid-dry climatophilous and edaphoxerophilous Accitano-Baztetan vegetation series. These are open formations with a climatophilous character that develop in a lower mesomediterranean thermoclimate in the Accitano-Baztetan biogeographical unit (Guadiana Menor valley), Betic biogeographical province, with an optimum in the semiarid ombroclimate on a substrate of poor gypsum-rich loam. The semiarid character and the abundance of gypsum do not allow for the development of Quercus rotundifolia, so the climax corresponds to the pinewood. As shown in Table 2, bioclimatic differences can be established between the different associations, with statistically significant differences between the values of the bioclimatic indices analysed for each of the proposed associations. This type of woodland should not, therefore, be considered as edaphoxerophilous when it is located on loams unless it develops on soils with a high gypsum content, as gypsum has the property of retaining water (trapped water), which is not useful for the plant. In these circumstances, the semiarid territory behaves as an arid territory [45]. The floristic composition of this pinewood includes Ephedra fragilis, Juniperus oxycedrus, Rhamnus lycioides, Asparagus horridus, Pistacia lentiscus, and occasionally Juniperus phoenicea.

Table 2.

Analysis of means by Kruskal-Wallis test of the selected bioclimatic variables associated with each sampling point.

3.1. Ass. Arbuto-Pinetum halepensis

Arbuto-Pinetum halepensis has been described as a climatophilous and edaphoxerophilous community with an Alcañizano-Gandesan distribution, and is considered a vicariant of Pistacio-Pinetum halepensis. This association is described as calcicolous, calco-dolomitic, and clayey materials in the semiarid-dry (the mean of Io index is 1.97) lower mesomediterranean bioclimate (the Itc index mean is 285.9). The Connover-Iman test establishes that there are bioclimatic differences between these two settlements for the variables MAX-JANUARY (p-value = 0.0002), PREC-JANUARY (p-value < 0.0001), PREC-DECEMBER (p-value < 0.0001) and Ic (p-value < 0.0001). Arbutus unedo is a species with a subhumid-humid and acidophilus optimum that penetrates in decarbonated clayey iron oxide-rich soils. The presence of the acidophilus elements A. unedo and Viburnum tinus gives this association a neutrophilous aspect. This species is not usually found in semiarid-dry environments, although it can occur on some humid rocky sites, allowing it to be potentially diagnosed as an edaphoxerophilous association. According to Rivas-Martínez et al. [18], Arbuto-Pinetum halepensis is Alcañizano-Gandesan, which corresponds to the easternmost territories of the Bardenero-Monegrino sector (Central Iberian Mediterranean province). Due to their floristic composition and distribution, we add to the relevés the author uses to establish the association (Table 75.7.26, Itinera Geobotanica 18:2, page 427) the relevés of Álvaréz de la Campa Fayos [24] which he included in Querco cocciferae-Lentiscetum Br.-Bl., Font Quer, G. Br.-Bl., Frey, Jansen & Moor 1936; and those of Rovira i López [40], which were adscribed to the association Rhamno lycioidis-Quercetum cocciferae Br.-Bl. and Bolòs 1954, but which have a predominance of P. halepensis, collected in the Valenciano-Tarraconensean sector (Catalano-Provenzal-Balearic province). These two associations present notable bioclimatic differences.

3.2. Ass. Ephedro nebrodensis-Pinetum halepensis

The Bardenero, Monegrino, and Somontano biogeographical sectors belong to the Central Iberian Mediterranean province [42,43,44,45], which include two groups of relevés of Braun-Blanquet & Bolòs [26]. The first group is relevés located in very warm environments with an ombrotype ranging from the lower dry to the upper semiarid in areas of d’Escatrón-Caspe-Candasmos, in calcareous semi-arid territories with gypsum, which were adscribed to Rhamneto-Cocciferetum pistacietosum lentisci. These samples did not correspond to a kermes oak-mastic woodland, as P. halepensis is the dominant element (Table 45, rel. 54 to 62 in Braun-Blanquet & Bolòs 1957). In addition to P. halepensis, the floristic elements include Juniperus phoenicea, J. oxycedrus, Ephedra major subsp. nebrodensis, and Rhamnus lycioides in the localities of Zuera and Caspe. This last taxon actually corresponds to Rhamnus oleoides subsp. angustifolia f. linearifolia Riv.-Mart. & Pizarro; we therefore propose the association Ephedro nebrodensis-Pinetum halepensis (Braun-Blanquet & Bolòs 1957) ass. nova (Table A1, rel. EnPh24 to EnPh40, holotypus rel. EnPh32) for the climatophilous character. This association is distributed in the Zaragozano Estepario and Belchitano Hijarensean districts in the Bardenero-Monegrino sector, but may occasionally extend into the Bilbilitano-Serrano Cucalonensean district in the Northern Oroiberian sector. Bioclimatically it is very similar to Arbuto-Pinetum halepensis. However, there are significant bioclimatic differences between the rest of the associations in variables related to the distribution of precipitation, maximum, average, and minimum monthly temperatures and in the values of the bioclimatic indices for PE, PEs, Ic, Io, and Itc, as can be seen in Table S1 (Supplementary Material).

3.3. Ass. Bupleuro rigidi-Pinetum halepensis

The relevés in the second group collected by Braun-Blanquet & Bolòs [26] are located at higher altitudes than the previous group, between 600–700 m. These are more continentalised and rainier environments on calcareous substrates in the Cincovillés, Zaragozano Estepario, and Somontano Aragonés districts in the Somontano sector; and in the Monegrino district in the Bardenero Monegrino sector, occasionally extending to the Alcañizano district, with an upper semi-arid to lower dry ombrotype, and in more continentalised environments than the previous association. This can be deduced from phytosociological table no. 45 of Braun-Blanquet & Bolòs [26], in which the authors include Rhamneto-Cocciferetum subass. cocciferetosum and subass. caricetosum humilis. In both cases, there is a predominance of Pinus halepensis, along with other species such as Quercus coccifera, Rubia peregrina, Rhamnus alaternus, Thymelaea tinctoria, Artostaphylos uva-ursi, Quercus faginea, and Q. rotundifolia; these last three taxa establish the more humid and colder character of the territory. Based on the biogeographical, ecological, and floristic differences, we propose as edaphoxerophilous the association Bupleuro rigidi-Pinetum halepensis (Braun-Blanquet & Bolos 1957) ass. nova (Table A2, rel. BrPh10 to BrPh52, holotypus rel. BrPh15). This association is characterised bioclimatically by its development in environments with a mean Io of 2.11 (σ = 0.43), a mean Ic of 18.55 (σ = 0.74), and a mean Itc of 262 (σ = 20.85). The bioclimatic differences between this association and the rest of the associations can be seen in Table S2 (Supplementary Material).

3.4. Ass. Ceratonio siliquae-Pinetum halepensis

The pinewoods of Pistacio-Pinetum halepensis have been described for the semiarid-dry (Io mean = 2.05) lower thermo-mesomediterranean bioclimate (Itc mean = 365.06) in Valencian territories, as a climatophilous and edaphoxerophilous community acting as secondary woodlands derived from Rubio longifoliae-Quercetum rotundifoliae [18]. It is reasonable for this pine-mastic woodland, which has previously been described for the semiarid and dry ombroclimate, to act as the head of the climatophilous series in semiarid environments, but not in dry environments where it is located in rocky areas on skeletal soils or sites denuded of soil. The holm-oak woodland of Rubio-Quercetum rotundifoliae occupies deep soils in the dry ombroclimate. All the relevés used in the description of this association by Rivas-Martínez et al. [18], Table 75.6.20 of Itinera Geobotánica 18(2), page 458, together with the relevés published by Pérez Badia [36] and Molina Cantos et al. [35] and included in the association Rhamno lycioidis-Quercetum cocciferae, belong to the association Pistacio lentisci-Pinetum halepensis, whose name was proposed by Rivas-Martínez et al. [18]. Unfortunately, this name had already been used by De Marco et al. [46], whose typification corresponds to relevé 17 in Table IV, so based on ICPN art. 31 and 39 we propose the name Ceratonio siliquae-Pinetum halepensis (Rivas-Martínez 2011) nom. nov. (Pistacio lentisci-Pinetum halepensis Rivas-Martínez 2011 in Itinera Geobotanica 18(2)458, Table 75.6.20. 2011); the relevés studied are in the Setabensean sector in the Allorano Cofrentino, Huertano Valenciano Turiano, Alcoyano Dianense, Yeclano Villenensean districts (Valenciana-Provenzal-Balearic province), and occasionally in the Alicantino Murciano sector in the Murciano Almeriensean province; this association is clearly differentiated from its northern vicariant Arbuto unedonis-Pinetum halepensis due to its richness in thermophilous species such as Osyris quadripartita, Chamaerops humilis and Arisarum vulgare. This association develops from the thermo- to mesomediterranean in an upper semiarid to lower dry ombrotype, although it may extend to the dry subhumid and may therefore contain elements of the subhumid, including Arbutus unedo, Pistacia terebinthus, Buxus sempervirens, and Certonia siliqua. This type of pine forest is therefore edaphoxerophilous.

3.5. Ass. Querco cocciferae-Pinetum halepensis

The association Querco cocciferae-Pinetum halepensis described by Rivas-Martínez et al. [18], Table 75.7.20 Itinera Geobotanica 18(2), page 460, has been given for semiarid-dry (Io mean = 2.09) mesomediterranean territories (Itc mean = 302.93) and is distributed in territories in the Manchego sector; it was previously proposed by Loisel [47] in the French Provence, but not typified. This association has a more continental character (Ic mean = 17.54) than Pistacio lentisci-Pinetum halepensis (Ic mean = 15.93) from which the thermophilous elements have disappeared, and includes the pine forests of the Manchuela Conquense, with some Setabensean influence and included by Rodríguez Rojo et al. [39] in the kermes oak woodlands of Rhamno lycioidis-Quercetum cocciferae. The relevés studied by us are located in the upper semiarid-lower dry ombrotype of the Serrano Espuñense and Jumillano Hellinense district (Manchego sector), and the Allorano Cofrentino district in the Setabensean sector.

According to its authors, the association Querco cocciferae-Pinetum halepensis can act as a primary and secondary woodland, the latter obtained from the burning of the holm-oak woodland Asparago acutifolii-Quercetum rotundifoliae. It is only natural that the secondary woodland should be edaphoxerophilous and not climatophilous, because in response to the burning of the holm-oak woodland and the loss of soil, it expands and seeks to occupy the biotope of the holm-oak formation.

3.6. Ass. Junipero turbinatae-Pinetum halepensis

The association JPh Junipero turbinatae-Pinetum halepensis represents the microforests of Pinus halepensis var. ceciliae with Juniperus turbinate and has a Balearic distribution that is typical of semiarid-dry (Io mean = 2.04) thermomediterranean environments (Itc mean = 388.71) on calco-dolomitic materials. This group is floristically differentiated from the other associations, and the formations act as edaphoxerophilous in areas with a dry ombroclimate. The strong drying winds (anemogenous character) produce an excessive loss of water that does not allow any other type of climax. However, in inland areas without strong winds and with a semiarid ombroclimate, these woodlands of P. halepensis var. ceciliae must be considered climatophilous. This association was described by Rivas-Martínez et al. [18], Table 75.6.18, Itinera Geobotánica 18(2), page 449, using the type relevé of the island of Majorca and two relevés for Menorca. We have included the relevés published by Rivas-Martínez et al. [18] and Bolòs & Molinier [25] for this syntaxon. We expand the distribution of this association with our observations to the islands of Ibiza and Formentera.

3.7. Ass. Rhamno angustifoliae-Pinetum halepensis

The pine forests sampled by us and extracted from the SIVIM [41] of the Serrano Mariense, Serrano Estanciano, and Serrano Bastitano districts in the Hoyano Accitano Bastitano sector (Betic province), located in the mesomediterranean with an ombrotype ranging from the upper semiarid to the upper dry on calcareous substrates at altitudes between 900–1600 m, constitute a new association that is floristically differentiated from its neighbours Ephedro fragilis-Pinetum halepensis with a semi-arid character in the Hoyano Accitano-Bastitano sector, the Manchegan and continental Querco cocciferae-Pinetum halepensis, and Rhamno almeriensis-Pinetum halepensis, with a thermomediterranean, Gadorensean and western Almeriensean distribution. The floristic composition of these pine forests comprises P. halepensis, Pistacia lentiscus, Quercus coccifera, Rhamnus alaternus subsp parvifolia, R. infectoria, R. myrtifolia, R. lycioides and R. oleoides subsp. angustifolia. We propose the association Rhamno angustifoliae-Pinetum halepensis ass. nova (Table A3 rel. RanPh044 to RanPh045, Holotypus rel. RanPh030). This association has an edaphoxerophilous character and an optimum in the dry ombrotype (Io mean = 2.98, σ = 0.48) with some typical species of this ombroclimate, such as Pistacia terebinthus, Quercus rotundifolia, and Crataegus monogyna. The bioclimatic characterisation of these Aleppo pine groves is based on the fact that they are established on sites with a mean Io of 2.98, a mean Itc of 317.97 (σ = 64.1), a PE of 768.8 (σ = 59.24), and a mean Ic of 16.79 (σ = 1.89). Table S3 (Supplementary Material) shows the bioclimatic differences between this association and the other associations studied.

3.8. Ass. Rhamno almeriensis-Pinetum almeriensis

For the territories in the Sierra de Gador (Gadorensean district, Alpujarreño-Gadorensean sector, Betic province) and in the Western Almeriensean and Serrano-Alhamillensean districts in the Murciano-Almeriensean province, Rivas-Martínez et al. [18] describe the association Rhamno almeriensis-Pinetum almeriensis in Sierra de Gador as a calco-dolomitic mesomediterranean, semiarid and dry community, which may extend down to the thermomediterranean. This association has a strong component of endemisms such as Phlomis almeriensis, Rhamnus velutinus subsp. almeriensis; it is thermo- and lower mesomediterranean (Itc mean = 351.18) with an ombrotype ranging between the upper semiarid and the lower subhumid (Io mean = 2.43, max Io = 4). The type relevé given by Rivas-Martínez et al. [18] in Itinera Geobotanica 18(2), pages 461–462, belongs to this association, together with the relevés extracted from SIVIM (Iberian and Macaronesian Vegetation Information System) [41].

3.9. Ass. Rhamno laderoi-Pinetum halepensis

In successive works, Pérez Latorre et al. [29,30,31,32] propose the association Pino halepensis-Juniperetum phoeniceae for the limestone dolomites of the subhumid-humid thermomediterranean in the Rondeño sector. The same authors subsequently propose a community of Pinus halepensis and Buxus balearica for the Sierras of Tejeda, Almijara, and Alhama, and recently the subassociation rhamnetosum myrtifoliae for the association Pino halpensis-Juniperetum phoeniceae, with a relevé from Sierra Almijara which they incorporate into the original table for the association. This subassociation corresponds to the syntaxon described by Molero & PérezRaya [48], Rhamno myrtifolii-Juniperetum phoeniceae; similarly, in their study of the Desfiladero de los Gaitanes (Malaga), they create the subassociation pinetosum halepensis for Asparago-Juniperum turbinatae, although this syntaxon is really an ecological variant. All our relevés, such as those extracted from the SIVIM, including that of Pérez Latorre et al. [31] in Jayena Sierra de Almijara, which are located in the dry-subhumid thermo- and lower mesomediterranean on dolomitic and limestone-dolomitic substrates, represent a new syntaxon whose floristic composition is given by Pinus halepensis, Juniperus phoenicea, Pinus pinaster, Rhamnus velutina subsp. velutina, Rhamnus lycioides subsp. laderoi, Anthyllis tejedensis (terr.), Ulex rivasgodayanum (terr.), and Brachypodium boissieri (terr.). This allows us to propose the association Rhamno laderoi-Pinetum halepensis ass. nova (Table A4 rel. RlaPh029 to RlaPh011, holotypus rel. RlaPh016) for the Granadino-Almijarensean sector. This association is dominant in the thermo- (max Itc = 434.03) and lower mesomediterranean (Itc mean = 317.97). It may occasionally extend to the upper mesomediterranean (min Itc = 238.14), where it contacts Rhamno myrtifolii-Juniperetum phoeniceae. Its ombrotype ranges from the lower dry (min Io = 1.97) and the lower subhumid (Io max = 3.74) with the average Io = 2.97 (upper dry). Table S4 (Supplementary Material) shows the bioclimatic differences between this association and the other associations studied.

Finally, Rhamno lycioidis-Pinetum halepensis (RlPh) has been described by Torres et al. [9] as Subbetic edaphoxerophilous on rocky limestone and limestone-dolomitic crests with a mesomediterranean thermoclimate (Itc mean = 264.85) and a dry-subhumid ombroclimate (Io mean = 3.97), owing to the water loss caused by their rocky nature. The Ioex is therefore semiarid-dry. All the associations studied have floristic, ecological, and biogeographical differences between them; however, from the bioclimatic point of view, they range from the semiarid to the subhumid.

4. Discussion

We have already mentioned that in some cases, the pinewood is described as a secondary woodland derived from Quercus rotundifolia forest owing to soil loss and the expansion of the genus Pinus, as occurs with the genus Juniperus [49,50,51,52]. This situation has led us to propose the separation of the climatophilous from the edaphoxerophilous character in the diagnosis of the communities [53]. We have, therefore, recently proposed the ombroedaphoxeric index Ioex = Pp − e/Tp × CR [54], which takes into account positive precipitation Pp, positive temperature Tp, residual evapotranspiration (e), and water retention capacity CR (0.25, 0.50, 0.75). The application of this index serves to differentiate the edaphoxerophilous associations from the climatophilous associations in Pinus halepensis.

The community of Ephedra fragilis and Pinus halepensis was described by Torres et al. [9] for the Guadiana Menor valley (Accitano-Baztetan sector), and raised to the association rank by Rivas-Martínez et al. [18]. Ephedro-Pinetum halepensis is described as climatophilous in semiarid environments on gypsum loams and gypsum [55,56,57]; whereas Rhamno-Pinetum halepensis has been described as edaphoxerophilous for the Subbetic sector on limestone and limestone dolomites and in dry-subhumid environments, and the association Junipero turbinatae-Pinetum halepensis as edaphoxerophilous in semiarid-dry environments on calco-dolomitic materials. Arbuto-Pinetum halepensis has been described as semiarid-dry, which appears doubtful as the species Arbutus unedo and Viburnum tinus included in the table cannot thrive in dry environments without soil compensation. In other cases, the pinewood is described as a secondary woodland derived from Quercus rotundifolia woodland owing to soil loss and the expansion of the genus Pinus, as occurs with Juniperus [48,49,50,53].

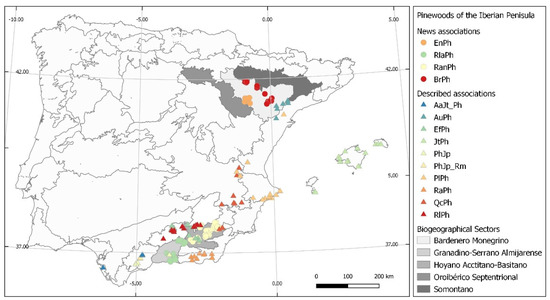

Following the ecological, floristic, bioclimatic, and biogeographical criteria for the relevés from the associations published previously and the new relevés, and proposing to separate the climatophilous from the edaphoxerophilous communities due to their different ecology, flora, and catenal contacts, we maintain the previously published associations with all the relevés belonging to and extracted from the SIVIM with a predominance of P. halepensis that have been adscribed to some of the erroneously published associations, and the relevés published by authors and included in different syntaxa [26,31,35,36], and we propose four new associations. However, in his studies on the Sierra de Cazorla, Gómez Mercado [34] assigns the Aleppo pine forests with Juniperus phoenicea to the association Rhamno lycioidis-Pinetum halepensis. We use this information to make an updated proposal on the syntaxonomy and distribution of the Aleppo pine communities on the Iberian Peninsula (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Biogeographical location of the associations in the study. Br. Bupleuro rigidi-Pinetum halepensis; EnPh. Ephedro nebrodensis-Pinetum halepensis; RanPh. Rhamno angutifoliae-Pinetum halepensis; RlaPh. Rhamno laderoi-Pinetum halepensis; AaJt_Ph. Asparago-Juniperetum turbinatae pinetosum halepensis; AuPh. Arbuto unedonis-Pinetum halepensis; EfPh. Ephedro fragilis-Pinetum halepensis; JtPh. Junipero turbinatae-Pinetum halepensis; PhJp. Pino halepensis-Juniperetum phoeniceae; PhJp. Pino halepensis-Juniperetum phoeniceae rhamnetosum myrtifoliae; PlPh. Pistacio lentisci-Pinetum halepensis; QcPh. Querco cocciferae-Pinetum halepensis; Rhamno almeriensis-Pinetum halepensis; RlPh. Rhamno lycioidis-Pinetum halepensis.

Several associations described by Rivas-Martínez et al. [18] have been proposed as climatophilous and edaphoxerophilous in semiarid-dry ombrotypes. When these pinewoods occur in a semiarid ombrotype, they are understood to be climatophilous, but act as edaphoxerophilous in a dry ombrotype. Although this appears to be true, there is some uncertainty, as the same syntaxon cannot have two different behaviours and maintain its floristic composition and catenal contacts.

This situation leads us to recommend the separation of the climatophilous from the edaphoxerophilous character in the diagnosis of the communities, and we have therefore recently proposed the ombroedaphoxeric index Ioex, which considers positive temperature Tp, residual evapotranspiration (e), and water retention capacity (CR) (0.25, 0.50, 0.75). Pinus halepensis has its bioclimatic optimum in semi-arid environments, where it acts as a climatophile, whereas in dry and lower sub-humid environments it can occupy rocky environments, where it acts as an edaphoxerophile; this behaviour is explained based on the ombroedaphoxeric index [54].

Ioex = Pp − e/Tp ∗ CR

Rivas-Martínez et al. [18] includes several associations of Pinus halepensis in the alliances Oleo-Ceratonion and Rhamno-Quercion cocciferae within the order Pistacio lentisci-Rhamnetalia alaterni. Biondi et al. [58] later describe the order Pinetalia halepensis with a thermo- and mesomediterranean character and the alliance Pistacio lentisci-Pinion halepensis. These authors report that these forests are dominated by Pinus halepensis and have a central-eastern Mediterranean distribution. This alliance is also again present in the north of Algeria, according to Rachid Meddour et al. [59]. Pesaresi et al. [19] have recently proposed several alliances for this order: Rosmarino officinalis-Pinion halepensis for the territories of Corsica, Sardinia, Sicily, and the Italo-Tyrrhenian coasts, and Sarcopoterio sipinosi-Pinion halepensis in Greek territories. Alkanno baeoticae-Pinion halepensis has been proposed by Mucina et al. [60] for serpentines on the Greek island of Euboea. The alliance Thymo vulgaris-Pinion halepensis has been described for the northern areas of the Italo-Tyrrhenian province and the Occitanian-Provencal sector in the Catalonian-Balearic-Provencal province, in the upper subhumid mesomediterranean thermotype. Its authors have proposed the association Cisto albidi-Pinetum halepensis as a holotypus for this alliance, with a subacidophilous mesomediterranean character in the Maritime Alps in Liguria.

Up to now, five alliances have been described for the order Pinetalia halepensis, with a distribution in the Italian, Greek, and Algerian territories, whereas the Iberian pine forests of Pinus halepensis have been included by Rivas-Martínez et al. [18] in the order Pistacio-Rhamnetalia alaterni. The use of species belonging to different phytosociological classes typical of other ecological niches can be observed in the diagnosis established for some of these alliances (Rosmarinus officinalis, Thymus vulgaris, Micromeria graeca, Cistus monspeliensis, Fumana thymifolia, Cistus albidus, Teucrium polium, Convolvulus elegantissimus, Coriaria myrtifolia, Phaganalon sordidum, Cistus creticus) [18,61,62,63].

The Iberian forests of P. halepensis have a different floristic and biogeographical composition from the forests described previously; however, they are similar from the physiognomical and ecological points of view. In our opinion, Pinetalia halepensis described for the central-eastern Mediterranean is also present in the western Mediterranean, although with differences between the eastern and western Mediterranean. We cannot include the associations analysed on the Iberian Peninsula in any of the alliances described for the order Pinetalia halepensis due to their major biogeographical, ecological, and floristic differences. We therefore propose the new alliance Rhamno lycioidis-Pinion halepensis all. nova hoc loco. The order Pinetalia halepensis on the Iberian Peninsula occupies semiarid bioclimatic environments where the forests have a climatophilous character, whereas it assumes an edaphoxerophilous character in dry and subhumid bioclimatic areas.

Holotypus: Rhamno lycioidis-Pinetum halepensis (J. Torres, A. García, Salazar, Cano & F. Valle 1999) Rivas-Martínez 2002.

Diagnostic species: Pinus halepensis, Rhamnus lycioides, Rhamnus oloeides subsp. angustifolia, Rhamnus lycioides subsp. laderoi, Rhamnus bourgaeana, Rhamnus myrtifolia, Rhamnus myrtifolia subsp. iranzoi, Asparagus horridus, Juniperus phoenicea, Efedra fragilis, Stipa tenacissima (com. terr.), Ulex parviflorus (com. terr.); these diagnostic species separate this alliance from the other five alliances in the order (Table 3). Finally, a synthetic table was prepared with all the associations studied (Table 4).

Table 3.

Diagnostic species that separate this alliance from the other five alliances in the order. AbPh: Alkanno boeticae-Pinion halepensis Mucina & Dimopoulos 2009; PlPh: Pistacio lentisci-Pinion halepensis Biondi, Blasi, Galdenzi, Pesaresi & Vagge in Biondi, Allegrezza, Cassavecchia, Galdenzi, Gasparri, Pesaresi, Vagge & Blasi 2014; TvPh: Thymo vulgaris-Pinion halepensis Biondi & Pesaresi in Pesaresi, Biondi, Vagge, Galdenzi & Cassavecchia 2017; RoPh: Rosmarino officinalis-Pinion halepensis Biondi & Pesaresi in Pesaresi, Biondi, Vagge, Galdenzi & Cassavecchia 2017; SsPh: Sarcopoterio spinosi-Pinion halepensis Biondi & Pesaresi in Pesaresi, Biondi, Vagge, Galdenzi & Cassavecchia 2017; RlPh: Rhamno lycioidis-Pinion halepensis all. nova.

Table 4.

Synthetic table of the association in the study. AuPh. Arbuto unedonis-Pinetum halepensis. CsPh. Ceratonio siliquae-Pinetum halepensis. JtPh. Junipero turbinatae-Pinetum halepensis. BrPh. Bupleuro rigidi-Pinetum halepensis. EnPh. Ephedro nebrodensis-Pinetum halepensis. RlaPh. Rhamno laderoi-Pinetum halepensis. RaPh. Rhamno almeriensis-Pinetum halepensi. RlPh. Rhamno lycioidis-Pinetum halepensis. EPh. Ephedro fragilis-Pinetum halepensis. QPh. Querco cocciferae-Pinetum halepensis. RanPh. Rhamno angustifoliae-Pinetu halepensis.

Diagnostic species: Pinus halepensis, Rhamnus lycioides, Rhamnus oloeides subsp. angustifolia, Rhamnus lycioides subsp. laderoi, Rhamnus bourgaeana, Rhamnus myrtifolia, Rhamnus myrtifolia subsp. iranzoi, Asparagus horridus, Juniperus phoenicea, Efedra fragilis, Stipa tenacissima (com. terr.), Ulex parviflorus (com. terr.); these diagnostic species separate this alliance from the other five alliances in the order (Table 3). Finally, a synthetic table was prepared with all the associations studied (Table 4).

Bonari et al. [63] propose the class Pinetea halepensis in the Mediterranean, and for the Iberian Peninsula the alliances Thymo vulgaris-Pinion halepensis Biondi & Pesaresi in Pesaresi, Biondi, Vagge, Galdenzi & Cassavecchia 2017 and Pistacio lentisci-Pinion halepensis Biondi, Blasi, Galdenzi, Pesaresi & Vagge in Biondi, Allegrezza, Cassavecchia, Galdenzi, Gasparri, Pesaresi, Vagge & Blasi 2014.

Bonari et al. include the distribution of Thymo vulgaris-Pinion halepensis from its authors Pesaresi et al. [19] and state that its distribution agrees with the Mesomediterranean basophilic scrub of Rosmarinetalia. Evidently, the area occupied by this order is much larger than that occupied by this alliance, so their distribution areas do not agree. They also state that the distribution of this alliance partially overlaps that of Pistacio lentisci-Pinion halepenis—which is synonymized by Rosmarino officinalis-Pinion halepensis—based on a larger dataset than used by the authors in the description. We cannot agree with this, as it does not consider the phytosociological nomenclature code (Def X and VI) [41]. The correct name is Rosmarino officinalis-Pinion halepensis, an alliance described for the biogeographical territories of the Italo-Tyrrhenian province and the easternmost Occitanian-Provencal sector of the Catalonian-Balearic-Provencal province, which according to these authors ranges from the upper thermo- to the upper meso thermotype.

According to Bonari et al. [63], the alliance Pistacio lentisci-Pinion halepensis is thermo-Mediterranean and is distributed from continental Greece to eastern Spain, and probably also in some areas of northwestern Africa, thus increasing the distribution area of this alliance. This does not coincide with the distribution given by these authors in their map (Figure 3, p. 10), and they do not include any Iberian association in this alliance.

However, the authors describe this alliance for the central-eastern Mediterranean, with an upper thermo- to upper meso thermotype. The original description was based on diagnostic species belonging to other phytosociological classes and is maintained by Bonari et al.; these species have very different ecological niches from that of Pinus halepensis and the taxa generally belong to Quercetea ilicis and Rosmarinetea officinalis [18].

A comprehensive debate is therefore required because of this controversy. For our part, the floristic, biogeographical, and bioclimatic differences allow us to propose a new alliance, which due to the large number of floristic elements in Quercetea ilicis, we prefer to keep in the order Pinetalia halepensis, class Quercetea ilicis.

5. Conclusions

This research confirms the autochthonous character of Pinus halepensis in Spain, and by accepting the associations already described and the new natural associations, we open the door to future repopulations in the bioclimatic environments typical of this species.

The analysis of the 11 associations in the study reveals certain similarities with common floristic elements. Although many associations have been described as climatophilous and edaphoxerophilous, if, in addition to the ombroclimatic factor, the soil factor is considered and the ombroedaphoxeric index is applied, sites with dry-subhumid ombroclimate index values that allow the development of Quercus rotundifolia woodlands cannot be considered as biotopes for P. halepensis unless they are located on rocks where the water loss prevents the holm oak woodland from thriving. This will then lead to the installation of the pinewood, which can be considered edaphoxerophilous. However, P. halepensis can thrive when the value of the ombroclimatic index is semiarid, and Q. rotundifolia is unable to do so when it forms a climatophilous microforest. As a result of the diagnosis of the communities, we propose to separate the climatophilous from the edaphoxerophilous communities.

Syntaxonomical Checklist

Quercetea ilicis Br.-Bl. ex A. & O. Bolòs 1950

Pinetalia halepensis Biondi, Blasi, Galdenzi, Pesaresi & Vagge in Biondi, Allegrezza, Casavecchia, Galdenzi, Gasparri, Pesaresi, Vagge & Blasi 2014

Rhamno lycioidis-Pinion halepensis all. nova

Arbuto unedonis-Pinetum halepensis Rivas-Martínez 2011

Querco cocciferae-Pinetum halepensis Rivas-Martínez & Alcaraz 2011

Junipero turbinatae-Pinetum halepensis Rivas-Martínez 2011

Rhamno almieriensis-Pinetum halepensis Rivas-Martínez 2011

Ephedro fragilis-Pinetum halepensis J. Torres, A. Garcia, Salazar, Cano, F. Valle & Rivas-Martínez 2011

Rhamno lycioidis-Pinetum halepensis (Torres, García Fuentes, Salazar, Cano & F. Valle 1999) Rivas-Martínez 2002

Ceratonio siliquae-Pinetum halepensis (Rivas-Martínez 2011) nom. nov.

Bupleuro rigidi-Pinetum halepensis (Braun-Blanquet & Bolòs 1957) ass. nova

Ephedro nebrodensis-Pinetum halepensis (Braun-Blanquet & Bolòs 1957) ass. nova

Rhamno angustifoliae-Pinetum halepènsis ass. nova

Rhamno laderoi-Pinetum halepensis ass. nova

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/land11030369/s1, Table S1: Ephedro nebrodensis-Pinetum halepensis; Table S2: Bupleuro rigidi-Pinetum halepensis; Table S3: Rhamno angustifoliae-Pinetum halepensis; Table S4: Rhamno laderoi-Pinetum halepensis.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.C. and A.C.-O.; methodology, E.C. and A.C.-O.; validation, E.C. and C.J.P.G.; formal analysis, E.C. and J.C.P.F.; investigation, E.C., A.C.-O., J.C.P.F., R.Q.-C., S.d.R. and C.J.P.G.; data curation, E.C., A.C.-O. and J.C.P.F.; writing—original draft preparation, E.C., A.C.-O. and J.C.P.F.; writing—review and editing, E.C., A.C.-O., J.C.P.F., R.Q.-C., J.I., S.d.R. and C.J.P.G.; visualization, E.C., A.C.-O. and C.J.P.G.; supervision, E.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Ephedro nebrodensis-Pinetum halepensis.

Table A1.

Ephedro nebrodensis-Pinetum halepensis.

| Surface m2 | 300 | 300 | 300 | 300 | 300 | 300 | 300 | 300 | 300 | 300 | 300 | 300 | 300 | 300 | 300 |

| Atitude in m | 629 | 601 | 547 | 596 | 593 | 570 | 595 | 536 | 619 | 585 | 662 | 587 | 562 | 594 | 582 |

| Orientation | N | N | NE | SE | NE | NE | N | E | NO | E | N | N | E | N | NE |

| Slope in decimal degrees | 22.14 | 19.32 | 10.8 | 13.36 | 10.44 | 24.86 | 29.53 | 11.24 | 5.07 | 16.69 | 24.94 | 17.33 | 11.36 | 5.9 | 5.95 |

| Cover rate % | 90 | 80 | 90 | 90 | 80 | 80 | 90 | 90 | 70 | 90 | 90 | 60 | 80 | 60 | 80 |

| Ic | 17.77 | 17.8 | 17.92 | 17.8 | 17.8 | 17.86 | 17.79 | 18.04 | 17.89 | 17.83 | 17.72 | 17.81 | 17.87 | 17.98 | 17.85 |

| Io | 1.97 | 2.5 | 1.96 | 1.99 | 2 | 1.99 | 2.03 | 2 | 2.41 | 1.95 | 2 | 2.02 | 2 | 2.07 | 1.94 |

| Itc | 269.7 | 269.98 | 272.45 | 270.93 | 270.98 | 271.47 | 270.46 | 269.02 | 261.71 | 271.93 | 268.24 | 270.66 | 271.64 | 265.48 | 272.15 |

| Nª inventory | EnPh24 | EnPh25 | EnPh26 | EnPh27 | EnPh28 | EnPh29 | EnPh30 | EnPh32Typus | EnPh33 | EnPh35 | EnPh36 | EnPh37 | EnPh38 | EnPh39 | EnPh40 |

| Nº Orden | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 |

| Characteristic species | |||||||||||||||

| Pinus halepensis Mill. | 5 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 3 | 5 | 5 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 4 |

| Quercus coccifera L. subsp. coccifera | 2 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 3 | + | 2 | + | 2 | + | |

| Juniperus oxycedrus L. subsp. oxycedrus | 1 | + | 1 | + | 1 | + | 3 | + | + | + | + | + | + | ||

| Juniperus phoenicea L. subsp. phoenicea | 2 | 2 | 1 | + | 1 | + | + | + | + | + | + | ||||

| Bupleurum rigidum L. | 1 | 1 | + | 2 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 2 | + | ||||||

| Rubia peregrina L. subsp. peregrina | + | 2 | + | 1 | 2 | 2 | + | + | 2 | + | |||||

| Ephedra nebrodensis Guss. | + | + | + | + | + | + | 1 | + | 1 | 1 | + | + | |||

| Rhamnus lycioides L. subsp. lycioides | + | + | + | + | 3 | + | |||||||||

| Pistacia lentiscus L. | + | + | + | ||||||||||||

| Carex halleriana Asso. | + | + | |||||||||||||

| Asparagus acutifolius L. | + | + | |||||||||||||

| Quercus rotundifolia Lam. | 2 | ||||||||||||||

| Rhamnus alaternus L. subsp. alaternus | + | ||||||||||||||

| Arctostaphylos uva-ursi (L.) Spreng. | + | ||||||||||||||

| Companion species | |||||||||||||||

| Carex humilis Leyss. | + | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | + | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Brachypodium retusum (Pers.) P. Beauv. | + | 3 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 5 | 2 | + | 3 | ||

| Stipa orientalis Trin. | + | + | + | + | 3 | + | 1 | 1 | 2 | + | + | 1 | 3 | ||

| Rosmarinus officinalis L. | 2 | + | + | + | + | + | 2 | + | + | + | 2 | 1 | |||

| Centaurea linifolia L. | 1 | + | 1 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | |||||

| Linum suffruticosum L. | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | 1 | + | |||||

| Coronilla minima L. subsp. lotoides (W.D.J. Koch) Nyman | 3 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | |||||

| Echinops ritro L. | + | + | + | 3 | + | + | + | + | + | + | |||||

| Avenula bromoides (Gouan) H. Scholz | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | 1 | + | ||||||

| Bupleurum fruticescens Loefl. ex L. | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | |||||||

| Euphorbia minuta Loscos & J. Pardo | + | + | + | + | + | 3 | 1 | + | |||||||

| Polygala rupestris Pourr. | + | + | + | + | 3 | + | + | 3 | |||||||

| Pleurochaete squarrosa Linderg | 1 | 2 | 1 | + | + | + | 3 | ||||||||

| Salvia officinalis L. | + | + | + | + | + | + | 3 | ||||||||

| Helianthemum myrtifolium (Lam.) Samp. | + | + | + | 1 | + | + | + | ||||||||

| Teucrium chamaedrys L. subsp. pinnatifidum (Sennen) Rech. fil. | + | + | 3 | + | 1 | 1 | + | ||||||||

| Rhaponticum coniferum (L.) Greuter | + | + | + | + | + | + | |||||||||

| Aristolochia pistolochia L. | 1 | + | + | + | + | 3 | |||||||||

| Genista scorpius (L.) DC. in Lam. & DC. | + | + | + | + | 1 | + | |||||||||

| Aphyllanthes monspeliensis L. | + | 3 | + | 3 | 2 | ||||||||||

| Fumana ericoides (Cav.) Gand. in Magnier | 3 | + | + | + | + | ||||||||||

| Lavandula latifolia Medik. | + | + | + | + | + | ||||||||||

| Thymus vulgaris subsp. vulgaris L. | + | + | 1 | + | + | ||||||||||

| Viola rupestris F.W. Schmidt | + | + | + | + | + | ||||||||||

| Cistus albidus L. | + | + | + | + | |||||||||||

| Cistus clusii subsp. clusii Dunal | 3 | 1 | + | + | |||||||||||

| Cistus libanotis L. | 3 | 1 | + | + | |||||||||||

| Inula montana L. | + | + | + | ||||||||||||

| Koeleria vallesiana subsp. vallesiana (Honck.) Gaudin | + | + | 1 | ||||||||||||

| Lithodora fruticosa (L.) Griseb. | + | + | + | ||||||||||||

| Orobanche latisquama (F.W. Schultz) Batt. in Batt. & Trab. | + | 3 | + | ||||||||||||

| Stereodon cupressiforme (Hedw.) Brid. ex Mitt. | 2 | 2 | + | ||||||||||||

| Dorycnium pentaphyllum Scop. | + | + | + | ||||||||||||

| Euphorbia verrucosa Lam. subsp. mariolensis (Rouy) Vives | + | + | + | ||||||||||||

| Anacamptis pyramidalis (L.) Rich. | 3 | 3 | |||||||||||||

| Globularia vulgaris L. | + | + | |||||||||||||

| Hedysarum boveanum Bunge ex Basiner subsp. europaeum Guitt. & Kerguélen | + | + | |||||||||||||

| Helianthemum syriacum (Jacq.) Dum. Cours. | + | + | |||||||||||||

| Ononis fruticosa L. | + | 1 | |||||||||||||

| Staehelina dubia L. | + | + | |||||||||||||

| Teucrium polium L. subsp. aragonense (Loscos & J.Pardo) Nyman | + | + | |||||||||||||

| Centaurium quadrifolium (L.) G. López & Jarvis subsp. barrelieri (L.M. Dufour) G. López | + | + |

Table A2.

Bupleuro rigidi-Pinetum halepensis.

Table A2.

Bupleuro rigidi-Pinetum halepensis.

| Surface m2 | 300 | 300 | 300 | 300 | 300 | 300 | 300 | 300 | 300 | 300 | 300 | 300 | 300 | 300 | 300 |

| Atitude in m | 619 | 532 | 669 | 652 | 700 | 700 | 675 | 671 | 686 | 600 | 570 | 622 | 265 | 327 | 149 |

| Orientation | NE | S | N | N | N | N | O | N | E | N | E | NE | NO | N | E |

| Slope in decimal degrees | 11.1 | 6.3 | 19.15 | 4.4 | 17.78 | 20.85 | 15.68 | 22.72 | 20.21 | 22.91 | 21.64 | 16.26 | 16.01 | 24.17 | 23.67 |

| Cover rate % | 85 | 85 | 90 | 90 | 90 | 90 | 90 | 90 | 80 | 65 | 80 | 90 | 80 | 80 | 85 |

| Ic | 17.6 | 18 | 16.97 | 18.88 | 18.73 | 18.73 | 18.82 | 18.83 | 18.87 | 17.77 | 18.79 | 17.58 | 19.38 | 18.76 | 19.37 |

| Io | 2.77 | 2.55 | 2.8 | 2.06 | 2.11 | 2.11 | 2.09 | 2.09 | 2.22 | 2.73 | 1.92 | 2.78 | 1.73 | 1.73 | 1.71 |

| Itc | 237.72 | 249.11 | 230.97 | 258.34 | 255.4 | 255.42 | 256.52 | 256.7 | 249.56 | 241.03 | 268.36 | 237.14 | 283.24 | 284.66 | 291.59 |

| Nª inventory | BrPh10 | BrPh11 | BrPh12 | BrPh14 | BrPh15Typus | BrPh16 | BrPh17 | BrPh18 | BrPh20 | BrPh21 | BrPh22 | BrPh23 | BrPh45 | BrPh46 | BrPh52 |

| Nº Orden | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 |

| Characteristic species | |||||||||||||||

| Pinus halepensis Mill. | 4 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| Quercus coccifera L. | 2 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 1 |

| Juniperus oxycedrus L. | 2 | + | + | + | 2 | 1 | + | 3 | 2 | 2 | + | + | + | ||

| Juniperus phoenicea L. | + | 3 | 1 | + | + | 1 | + | + | 2 | 3 | 2 | ||||

| Carex halleriana Asso. | 3 | 1 | + | + | + | 2 | + | 1 | 1 | 1 | + | + | 1 | + | |

| Rubia peregrina L. | + | + | + | 1 | + | + | 2 | 1 | + | 1 | + | 1 | + | ||

| Rhamnus lycioides L. | + | + | 3 | 1 | + | 2 | |||||||||

| Arctostaphylos uva-ursi (L.) Spreng. | + | 1 | + | + | + | 4 | 2 | 4 | 3 | ||||||

| Pistacia lentiscus L. | 1 | 2 | + | ||||||||||||

| Quercus rotundifolia Lam. | 3 | + | + | 2 | + | + | |||||||||

| Ephedra nebrodensis Guss. | + | 1 | + | ||||||||||||

| Rhamnus alaternus L. | + | + | + | ||||||||||||

| Bupleurum rigidum L. | + | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | + | + | ||||||||

| Juniperus thurifera L. | + | + | + | + | 1 | ||||||||||

| Phillyrea angustifolia L. | + | ||||||||||||||

| Quercus faginea Lam. | + | ||||||||||||||

| Companion species | |||||||||||||||

| Brachypodium retusum (Pers.) P. Beauv. | + | 2 | 1 | + | 1 | + | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | + | 1 | 1 | 1 | + |

| Teucrium chamaedrys L. subsp. pinnatifidum (Sennen) Rech. fil. | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | + | 2 | 3 | + | 1 | ||||

| Thymelaea tinctoria (Pourr.) Endl. | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | ||||

| Stereodon cupressiformis (Hedw.) Brid. ex Mitt. | 1 | + | 3 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 3 | ||||

| Helianthemum myrtifolium (Lam.) Samp. | 1 | 2 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | ||||||

| Rosmarinus officinalis L. | 3 | + | + | + | + | + | 1 | 2 | |||||||

| Rhaponticum coniferum (L.) Greuter | + | + | + | + | + | + | |||||||||

| Asphodelus cerasiferus J. Gay | 3 | + | + | + | 3 | + | |||||||||

| Genista scorpius (L.) DC. in Lam. & DC. | + | + | + | + | + | ||||||||||

| Pleurochaete squarrosa Linderg | + | 1 | + | 1 | + | ||||||||||

| Festuca rubra L. | 3 | + | + | + | + | ||||||||||

| Viola rupestris F.W. Schmidt | 1 | 3 | + | + | + | ||||||||||

| Dorycnium pentaphyllum Scop. | 1 | 3 | + | + | 1 | ||||||||||

| Helianthemum origanifolium subsp. origanifolium (Lam.) Pers. | + | + | + | 1 | |||||||||||

| Salvia officinalis L. | + | + | + | + | |||||||||||

| Cladonia pyxidata (L.) Hoffm. | 3 | + | + | 3 | |||||||||||

| Thymus vulgaris L. | 3 | + | + | ||||||||||||

| Viscum album L. subsp. austriacum (Wiesb.) Vollm. | + | + | + | ||||||||||||

| Staehelina dubia L. | + | 3 | 3 | ||||||||||||

| Bupleurum fruticescens Loefl. ex L. | + | 3 | + | ||||||||||||

| Aristolochia pistolochia L. | + | + | |||||||||||||

| Epipactis microphylla (Ehrh.) Sw. | + | + | |||||||||||||

| Galium pumilum Murray | + | + | |||||||||||||

| Helianthemum violaceum (Cav.) Pers. | + | + | |||||||||||||

| Homalothecium sericeum W. P. Schimper | + | 3 | |||||||||||||

| Linum narbonense L. | 3 | 3 | |||||||||||||

| Thalictrum tuberosum L. | + | + | |||||||||||||

| Thesium humifusum DC. in Lam. & DC. | + | + |

Table A3.

Rhamno angustifoliae-Pinetum halepensis.

Table A3.

Rhamno angustifoliae-Pinetum halepensis.

| Surface m2 | 300 | 300 | 300 | 300 | 300 | 300 | 300 | 300 | 300 | 300 | 300 | 300 | 300 | 300 | 300 | 300 | 300 | 300 | 300 | 300 |

| Atitude in m | 1212 | 1233 | 1179 | 1150 | 1326 | 1192 | 1100 | 1209 | 1154 | 1179 | 1179 | 1254 | 1086 | 1160 | 1111 | 1011 | 1100 | 971 | 894 | 1212 |

| Orientation | NE | NE | SO | SE | NO | E | E | SO | NE | N | E | E | NO | E | NO | O | E | NO | SE | E |

| Slope in decimal degrees | 7.82 | 19.76 | 19.43 | 8.19 | 12.51 | 15.82 | 12.89 | 7.52 | 13.86 | 26.67 | 19.43 | 6.76 | 26.32 | 15.29 | 3.87 | 14.78 | 12.89 | 6.6 | 17.93 | 22.2 |

| Cover rate % | 80 | 80 | 80 | 55 | 95 | 70 | 65 | 55 | 65 | 65 | 40 | 55 | 55 | 55 | 65 | 65 | 65 | 65 | 55 | 55 |

| Ic | 18.02 | 17.85 | 17.87 | 18.62 | 18.34 | 18.57 | 18.07 | 18.58 | 18.08 | 18.59 | 17.87 | 18.54 | 18.51 | 17.78 | 17.85 | 17.7 | 18.07 | 17.6 | 17.45 | 18.52 |

| Io | 2.23 | 2.47 | 2.39 | 2.3 | 2.64 | 2.43 | 2.12 | 2.25 | 2.21 | 2.4 | 2.39 | 2.33 | 1.99 | 2.33 | 2.23 | 2.08 | 2.12 | 2.04 | 2.02 | 2.47 |

| Itc | 230.18 | 228.71 | 233.32 | 245.39 | 230.21 | 232.87 | 247.87 | 233.38 | 238.31 | 234.47 | 233.32 | 229.61 | 260.01 | 238.42 | 248.41 | 270.19 | 247.87 | 275.7 | 282.81 | 231.04 |

| Nª inventory | RanPh063 | RanPh065 | RanPh066 | RanPh010 | RanPh011 | RanPh012 | RanPh030 | RanPh033 | RanPh034 | RanPh049 | RanPh066 | RanPh069 | RanPh071 | RanPh017 | RanPh019 | RanPh024 | RanPh030Typus | RanPh038 | RanPh043 | RanPh044 |

| Nº Orden | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 |

| Characteristic species | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Pinus halepensis Mill. | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 5 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| Rhamnus oleoides subsp. angustifolia (Lange & Willk.) Rivas Mart. & J.M. Pizarro | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| Quercus rotundifolia Lam. | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | + | + | + | + | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| Juniperus oxycedrus subsp. oxycedrus L. | 1 | 3 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | 2 | 2 | |||||||||

| Juniperus phoenicea subsp. phoenicea L. | + | + | + | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||||||

| Carex halleriana Asso. | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | ||||||||||||||||

| Rhamnus lycioides subsp. lycioides L. | 1 | |||||||||||||||||||

| Asparagus acutifolius L. | + | |||||||||||||||||||

| Daphne gnidium L. | + | + | 1 | 2 | 1 | |||||||||||||||

| Quercus coccifera subsp. coccifera L. | 2 | 1 | 2 | |||||||||||||||||

| Crataegus monogyna subsp. brevispina (Kunze) Franco | 1 | + | ||||||||||||||||||

| Pistacia lentiscus L. | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Pistacia terebinthus L. | + | + | ||||||||||||||||||

| Companion species | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Rosmarinus officinalis L. | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | ||||||

| Macrochloa tenacissima (L.) Kunth | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | + | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | |||||||

| Brachypodium retusum subsp. retusum (Pers.) P. Beauv. | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | |||||||||

| Thymus zygis subsp. gracilis (Boiss.) R. Morales | 1 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||

| Genista scorpius (L.) DC. in Lam. & DC. | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | |||||||||||

| Thymus membranaceus subsp. membranaceus Boiss. | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | ||||||||||||

| Erinacea anthyllis Link | 2 | + | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | ||||||||||||||

| Festuca scariosa (Lag.) Asch. & Graebn. | + | 2 | 2 | 2 | ||||||||||||||||

| Cistus clusii subsp. clusii Dunal | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | ||||||||||||||||

| Lavandula stoechas L. | 3 | 3 | 3 | |||||||||||||||||

| Helichrysum stoechas (L.) Moench | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||||||||

| Helianthemum almeriense Pau | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||||||||

| Bupleurum fruticescens subsp. spinosum (Gouan) O. Bolòs & Vigo | 2 | 1 | 2 | |||||||||||||||||

| Fumana thymifolia (L.) Spach ex Webb | 2 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||||||||

| Genista cinerea subsp. speciosa Losa & Rivas Goday (Vill.) DC. | + | 2 | 2 | |||||||||||||||||

| Phlomis lychnitis L. | 3 | 2 | + | |||||||||||||||||

| Dorycnium pentaphyllum Scop. | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Euphorbia nicaeensis All. | 3 | + | ||||||||||||||||||

| Sideritis incana L. | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Stipa lagascae Roem. & Schult. | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Thymus mastichina subsp. mastichina (L.) L. | 1 | + | ||||||||||||||||||

| Trifolium spumosum L. | 2 | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Ulex parviflorus subsp. parviflorus Pourr. | + | 1 |

Table A4.

Rhamno laderoi-Pinetum halepensis.

Table A4.

Rhamno laderoi-Pinetum halepensis.

| Surface m2 | 300 | 300 | 300 | 300 | 300 | 300 | 300 | 300 | 300 | 300 | 300 | 300 | 300 | 300 | 300 |

| Atitude in m | 1270 | 1076 | 1034 | 1102 | 1040 | 1223 | 1071 | 226 | 422 | 552 | 144 | 560 | 1012 | 894 | 226 |

| Orientation | O | S | S | O | SO | NE | NE | NO | S | NE | S | S | O | SE | NO |

| Slope in decimal degrees | 22.39 | 10.1 | 28.19 | 13.39 | 35.8 | 14.09 | 11.58 | 25.48 | 12.33 | 27.98 | 28.51 | 31.64 | 40.25 | 33.22 | 25.48 |

| Cover rate % | 60 | 60 | 80 | 65 | 80 | 65 | 65 | 60 | 60 | 65 | 90 | 60 | 60 | 65 | 50 |

| Ic | 18.44 | 18.24 | 18.37 | 18.38 | 16.97 | 18.66 | 17.5 | 13.33 | 13.55 | 15.52 | 14.05 | 14.87 | 18.74 | 16.05 | 13.33 |

| Io | 3.75 | 3.21 | 3.11 | 3.23 | 3.37 | 3.69 | 3.44 | 2.36 | 2.59 | 2.78 | 1.94 | 2.88 | 2.54 | 3.12 | 2.36 |

| Itc | 244.61 | 282.46 | 284.49 | 272.54 | 296.91 | 238.15 | 272.02 | 434.04 | 423.51 | 371.18 | 424.74 | 379.4 | 277.37 | 329.67 | 434.04 |

| Nª inventory | RlaPh029 | RlaPh034 | RlaPh035 | RlaPh036 | RlaPh050 | RlaPh032 | RlaPh041 | RlaPh011 | RlaPh014 | RlaPh016Typus | RlaPh024 | RlaPh025 | RlaPh060 | RlaPh018 | RlaPh011 |

| Nº Orden | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 6 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 16 | 17 | 18 |

| Characteristic species | |||||||||||||||

| Pinus halepensis Mill. | 3 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 5 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 |

| Rhamnus ladedroi Rivas-Mart. & J.M. Pizarro | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | + | 1 | + | 1 | + | + | + | 1 | + | |

| Juniperus oxycedrus subsp. oxycedrus L. | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | ||||||||

| Daphne gnidium L. | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | |||||||||

| Quercus coccifera L. subsp. coccifera | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | |||||||||||

| Olea europaea var. sylvestris (Mill.) Lehr | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | |||||||||||

| Rhamnus myrtifolia Willk. | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||

| Quercus rotundifolia Lam. | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||

| Chamaerops humilis L. | 2 | 2 | 3 | ||||||||||||

| Asparagus acutifolius L. | 2 | 2 | |||||||||||||

| Rhamnus alaternus L. subsp. alaternus | 2 | ||||||||||||||

| Rhamnus alaternus subsp. parvifolia Arcang. | + | ||||||||||||||

| Rhamnus velutina Boiss. subsp. velutina | 2 | ||||||||||||||

| Juniperus phoenicea L. subsp. phoenicea | 1 | ||||||||||||||

| Pinus pinaster Aiton | 1 | ||||||||||||||

| Aristolochia baetica L. | 2 | ||||||||||||||

| Buxus balearica Lam. | 2 | ||||||||||||||

| Carex halleriana Asso. | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||||

| Pistacia lentiscus L. | 2 | 2 | |||||||||||||

| Pistacia terebinthus L. | + | ||||||||||||||

| Quercus faginea subsp. alpestris (Boiss.) Maire | 1 | ||||||||||||||

| Rubia peregrina L. subsp. peregrina | 1 | ||||||||||||||

| Teucrium fruticans L. | + | ||||||||||||||

| Companion species | |||||||||||||||

| Rosmarinus officinalis L. | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | ||||

| Ulex parviflorus subsp. parviflorus Pourr. | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | |||||||

| Brachypodium retusum subsp. retusum (Pers.) P. Beauv. | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | ||||||||

| Macrochloa tenacissima (L.) Kunth | 2 | 2 | 3 | ||||||||||||

| Cistus albidus L. | 2 | 2 | 2 | ||||||||||||

| Phlomis purpurea L. subsp. purpurea | 2 | 2 | 2 | ||||||||||||

| Genista scorpius (L.) DC. in Lam. & DC. | 2 | 2 | |||||||||||||

| Echinospartum boissieri (Spach) Rothm. | 2 | 1 | |||||||||||||

| Lavandula latifolia Medik. | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||||

| Lavandula stoechas L. | 3 | ||||||||||||||

| Helichrysum stoechas (L.) Moench | 1 | ||||||||||||||

| Genista umbellata subsp. equisetiformis (Spach) Rivas Goday & Rivas Mart. | 2 | ||||||||||||||

| Cistus clusii subsp. clusii Dunal | 1 | ||||||||||||||

| Astragalus incanus L. subsp. incanus | + | ||||||||||||||

| Berberis hispanica Boiss. & Teut. | 1 | ||||||||||||||

| Brachypodium retusum subsp. boissieri (Nyman) Romero García | 2 | ||||||||||||||

| Bupleurum fruticescens subsp. spinosum (Gouan) O. Bolòs & Vigo | 1 | ||||||||||||||

| Cistus salviifolius L. | 2 | ||||||||||||||

| Dactylis glomerata subsp. hispanica (Roth) Nyman | 2 | ||||||||||||||

| Erica multiflora L. | 2 | ||||||||||||||

| Festuca indigesta subsp. hackeliana | 1 |

References

- Do Amaral Franco, J. Pinus L. in Flora Ibéria Vol I; Castroviejo, S., Lain, M., López González, G., Monserrat, P., Muñoz-Garmendia, F., Paiva, J., Villar, L., Eds.; Real Jardín Botánico, CSIC: Madrid, Spain, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Bolòs, O.; de Vigo, J.; Masalles, R.M.; Ninot, J.M. Manual Dels Paisos Catalans; Portic: Barcelona, Italy, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández-Galiano, E. Pasado, Presente y Futuro de los Boques de la Península Ibérica. Acta Bot. Malacit. 1990, 15, 135–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Postigo-Mijarra, J.M.; Manzaneque, F.G.; Juaristi, C.M.; Zazo, Z. Palaeoecological significance of Late Pleistocene pine macrofossils in the lower Guadalquivir Basin (Doñana natural park, southwestern Spain). Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 2010, 295, 332–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiori, A. Nuova Flora Analitica D´italia; Library New York: Firenze, Italy, 1923; Volume I. [Google Scholar]

- Conti, F.; Abbate, G.; Alessandrini, A.; Blasi, C. (Eds.) An Annotated Checklist of the Italian Vascular Flora; Ministero dell´Ambiente de della Tutela del Territorio-Direzione per la Protezione della Natura, Dipartimento de BiologiaVegetale-Università degli Studi di Roma “La Sapienza”: Roma, Italy, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Bartolucci, F.; Peruzzi, L.; Galasso, G.; Albano, A.; Alessandrini, A.N.M.G.; Ardenghi, N.M.G.; Astuti, G.; Bacchetta, G.; Ballelli, S.; Banfi, E.; et al. An updated checklist of the vascular flora native to Italy. Plant Biosyst. 2018, 152, 179–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galasso, G.; Conti, F.; Peruzzi, L.; Ardenghi, N.M.G.; Banfi, E.; Celesti-Grapow, L.; Albano, A.; Alessandrini, A.; Bacchetta, G.; Ballelli, S.; et al. An updated checklist of the vascular flora alien to Italy. Plant Biosyst. 2018, 152, 556–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, J.A.; García Fuentes, A.; Salazar, C.; Cano, E.; Valle, F. Caracterización de los Pinares de Pinus halepensis Mill. en el sur de la Península Ibérica. Ecol. Mediterránea 1999, 25, 135–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maire, R. Flore de l´Afrique de Nort, 1st ed.; Paul Lechevalier: Paris, Frence, 1987; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Ighbareyeh, M.M.H.; Cano, E.; Cano-Ortiz, A.; Ighbareyeh, J.; Suliemieh, A.A.A. Phytosociology with other Characteristic Biologically and Ecologically of Plant in Palestine. Am. J. Plant Sci. 2014, 5, 3104–3118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quézel, P.; Barbero, M.; Benabid, A.; Rivas-Martínez, S. Contribution a l´etude des groupements foretiers et pre-forestiers du Maroc Oriental. Studa Bot. 1992, 10, 57–90. [Google Scholar]

- Parra, I. Análisis polínico del sondaje C.A.L. 81-I. (Casablanca-Almenara, Prov. Castellón). In Actas del IV Simposio de Palinología Española; APLE: Barcelona, Spain, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Rivera, B.; Obón, C. Macrorrestos vegetales de los yacimientos 433–445 de la comarca noroeste en los inicios de la Edad de los Metales. In El cambio Cultural del IV al II Milenios a.C. en la Comarca Noroeste de Murcia; López, P., Ed.; CSIC: Madrid, Spain, 1991; Volume I, pp. 239–246. [Google Scholar]

- Ariza, M.O.R. Human-plant relationships during the Copper & Bronze Ages in the Baza & Guadix basins (Granada, Spain). Bull. Société Bot. France. Actual. Bot. 1992, 139, 451–464. [Google Scholar]

- Ariza, M.O.R.; Vernet, J.L. Premiers resutats peléoécologiques de l´établissement chalcothique de Los Millares (Santa Fé de Mondujar, Almería, Espagñe) d´après l´analyse anthracologique. In Lind Deya Conference of Prehistory 1–13; BAR International Series; Weldren, W.H., Ensenyal, J.A., Kennard, R.C., Eds.; BAR Publishing: Oxford, UK, 1991; Volume I. [Google Scholar]

- Ariza, M.O.R.; Aguayo, P.; Moreno, F. The environment in the Ronda Basin (Málaga, Sapin) during recent prehistory based on an anthracological study of Old Ronda. Bull. Société Bot. France. Actual. Bot. 1992, 139, 715–725. [Google Scholar]

- Rivas-Martínez, S.; Asensi, A.; Valle, F.; Garretas, B.D. Mapa de series, geoseries y geopermaseries de vegetación de España. Parte II. Itinera Geobot. 2011, 18, 425–800. [Google Scholar]

- Pesaresi, S.; Bioindi, E.; Vagge, I.; Galdenzi, D.; Casavecchia, S. The Pinus halepensis Mill. Forests in the central-eastern European Mediterranean basin. Plant Biosyst. 2017, 151, 512–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bucci, G.; Anzidei, M.; Madaghiele, A.; Vendramin, G.G. Detection of haplotypic variation and natural hybridization in halepensis-complex pine species using chloroplast simple sequence repeat (SSR) markers. Mol. Ecol. 1998, 7, 1633–1643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panetsos, C.P. Natural hybridization between Pinus halepensis and Pinus brutia. Silvae Genet. 1975, 24, 163–168. [Google Scholar]

- Farjon, A. Pinus brutia. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2013: Et42347a2974345. Available online: https://www.iucnredlist.org/ (accessed on 14 January 2020).

- Daniels, R.R.; Taylor, R.S.; Serra-Varela, M.J.; Vendramin, G.G.; González-Martínez, S.C.; Grivet, D. Inferring selection in instances of long-range colonization: The Aleppo pine (Pinus halepensis) in the Mediterranean Basin. Mol. Ecol. 2018, 27, 3331–3345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de la Campa Fayos, J.M.Á. Vegetació del Massís del Port.; Colúlecció Pius Font i Quer, 3; Institut d’Estudis Ilerdencs: Lleida, Spain, 2004; p. 459. [Google Scholar]

- Bolòs, O.; de et Molinier, R. Recherches phytosociologiques dans l’île de Majorque. Collect. Bot. 1958, V, 699–865. [Google Scholar]

- Braun-Blanquet, J. i Bolòs, O. de. Les groupements végétaux du bassin moyen de l’Ebre et leur dynamisme. An. Estac. Exp. Aula Dei. 1957, 5, 1–266. (In Saragossa) [Google Scholar]

- Cabezudo, B.; Pérez-Latorre, A.V.; Navas, P.; Gil, Y.; Navas, D. Parque natural de la Sierra de las Nieves. ‘Cartografía y evaluación de la flora y vegetación’. In Memoria de Investigación; Departamento de Biología Vegetal, Universidad de Málaga: Málaga, Spain, 1998; p. 367. [Google Scholar]

- Olmedo, J.A. Análisis Biogeográfico y Cartografía de la Vegetación de la Sierra de Baza (Provincia de Granada). Ph.D. Thesis, Universidad de Granada, Granada, Spain, 2011; p. 783. [Google Scholar]

- Latorre, A.V.P.; Navas, P.; Navas, D.; Gil, Y.; Cabezudo, B. Datos sobre la flora y la vegetación de la Serranía de Ronda (Málaga, España). Acta Bot. Malacit. 1998, 23, 149–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latorre, A.V.P.; Fernández, D.N.; Gavira, O.; Caballero, G.; Cabezudo, B. Vegetación del Parque Natural de Las Sierras Tejeda, Almijara y Alhama (Málaga-Granada, España). Acta Bot. Malacit. 2004, 29, 117–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Latorre, A.V.; Casimiro, F.; Cabezudo, B. Flora y vegetación de la sierra de Alcaparaín (Málaga, España). Acta Bot. Malacit. 2015, 40, 107–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Pérez-Latorre, A.V.; Casimiero, F.; Sánchez, J.G.; Cabezudo, B. Flora y vegetación del Paraje Natural Desfiladero de los Gaitanes y su entorno (Málaga). Acta Bot. Malacit. 2014, 39, 129–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llueca, C.; Udias, S.L. Estudio de las Comunidades Vegetales del Valle del Mijares (Teruel); Servicio de Conservación de la Biodiversidad; Gobierno de Aragón: Zaragoza, Spain, 2004; pp. 1–122. [Google Scholar]

- Gómez-Mercado, F. Vegetación y flora de la Sierra de Cazorla. Guineana 2011, 17, 1–481. [Google Scholar]

- Cantos, R.M.; Franzi, A.V.; Ariza, F.J.A. Flora y Vegetación del Tramo Medio del Valle del Río Júcar (Albacete); Instituto de estudios albacetenses ‘Don Juan Manuel’ de la excma: Alicante, Spain, 2008; p. 663. [Google Scholar]

- Badia, R.P. Flora Vascular y Vegetación de la Comarca de la Marina Alta (Alicante); Colección Técnica 16; Instituto de Cultura Juan Gil Albert: Alicante, Spain, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez, S.R.; Costa, M.; Soriano, P.; Badia, R.P.; Llorens, L.; Roselló, J.A. Datos sobre el paisaje vegetal de Mallorca e Ibiza (Islas Baleares, España). Itinera Geobot. 1992, 6, 5–98. [Google Scholar]

- Rivas-Martínez, S.; Pizarro, J.M. Taxonomical system advance to Rhamnus, L. & Frangula Mill. of Iberian Peninsula and Balearic Islands. Int. J. Geobot. Res. 2011, 1, 55–78. [Google Scholar]

- Rojo, M.P.R.; Úbeda, J.R.; Badia, R.P. La diversidad vegetal de La Manchuela Conquense: Una comarca manchega con influencias setabenses y celtibérico-alcarreñas. Lazaroa 2009, 30, 35–49. [Google Scholar]

- López, A.M.R.i. Estudi Fitogeogràfic de les Comarques Catalanes Compreses Entre Els Ports de Beseit, el Riu Ebre i Els Límits Aragonesos. Ph.D. Thesis, Universitat de Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- SIVIM. Sistema de Información de la Vegetación Ibérica y Macaronésica. Available online: http://www.sivim.info/sivi/PissarraUTM.jsp?ruta=f2.1&utm=30SXK60 (accessed on 20 February 2022).

- Rivas-Martínez, S.; Penas, A.; González, T.E.D.; Cantó, P.; del Río, S.; Costa, C.; Herrero, L.; Molero, J. Biogeographic Units of the Iberian Peninsula and Balearic Islands to District Level. A Concise Synopsis. In The Vegetation of the Iberian Peninsula, Plant and Vegetation 12; Loidi, J., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017; pp. 131–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivas-Martínez, S.; Rivas-Sáenz, S.; Penas, A.S. Worldwide bioclimatic classification system. Glob. Geobot. 2011, 1, 1–634. [Google Scholar]

- Theurillat, J.P.; Willner, W.; Fernández-González, F.; Bültmann, H.; Čarni, A.; Gigante, D.; Mucina, L.; Weber, H. International Code of Phytosociological Nomenclature. 4th edition. Appl. Veg. Sci. 2020, 24, e12491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivas-Martínez, S. Mapa de series, geoseries y geopermaseries de vegetación de España. Parte I. Itinera Geobot. 2007, 17, 5–436. [Google Scholar]