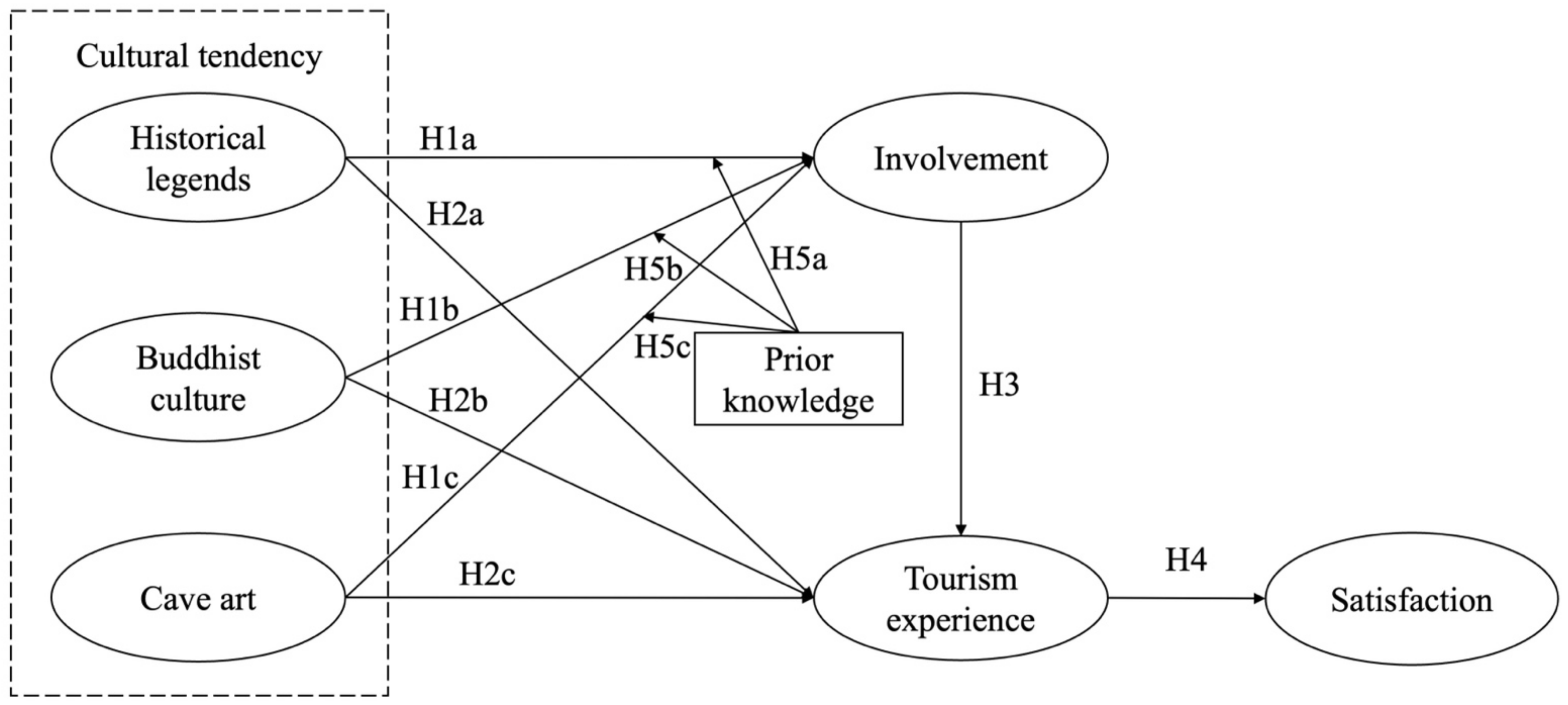

Role of Cultural Tendency and Involvement in Heritage Tourism Experience: Developing a Cultural Tourism Tendency–Involvement–Experience (TIE) Model

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Heritage Tourism

2.2. Cultural Tendency as Tourists’ Intention to Search for Cultural Experience

2.3. Involvement in Heritage Tourism

2.4. Heritage Tourism Experience

2.5. The Moderating Effect of Prior Knowledge

3. Materials and Methods

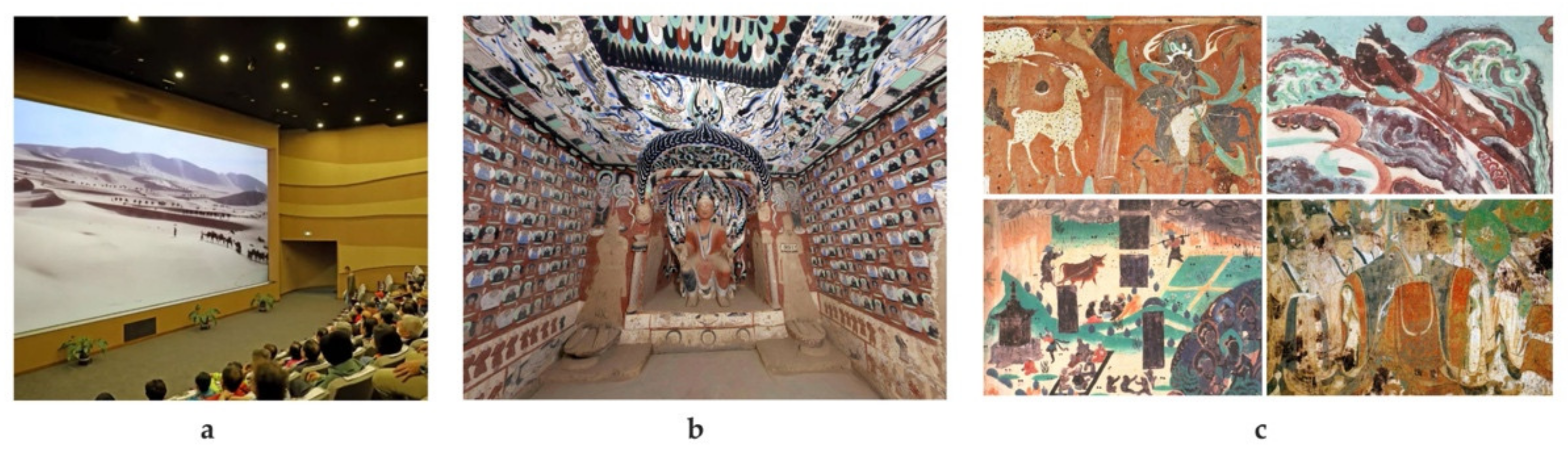

3.1. Study Area

3.2. Research Methods

4. Results

4.1. Sample Descriptive Statistics

4.2. Measurement Model

4.3. Structural Model

4.4. Testing the Moderating Effect of Prior Knowledge

5. Discussion and Implications

5.1. Theoretical Implications

5.2. Management Implications

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Domínguez-Quintero, A.M.; González-Rodríguez, M.R.; Paddison, B. The mediating role of experience quality on authenticity and satisfaction in the context of cultural-heritage tourism. Curr. Issues Tour. 2020, 23, 248–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poria, Y.; Butler, R.; Airey, D. The Core of Heritage Tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 2003, 30, 238–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Carbone, F.; Oosterbeek, L.; Costa, C.; Ferreira, A.M. Extending and Adapting the Concept of Quality Management for Museums and Cultural Heritage Attractions: A Comparative Study of Southern European Cultural Heritage Managers’ Perceptions. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2020, 35, 100698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katahenggam, N. Tourist Perceptions and Preferences of Authenticity in Heritage Tourism: Visual Comparative Study of George Town and Singapore. J. Tour. Cult. Change 2020, 18, 371–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mgxekwa, B.B.; Scholtz, M.; Saayman, M. A Typology of Memorable Experience at Nelson Mandela Heritage Sites. J. Herit. Tour. 2019, 14, 325–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alazaizeh, M.M.; Hallo, J.C.; Backman, S.J.; Norman, W.C.; Vogel, M.A. Giving Voice to Heritage Tourists: Indicators of Quality for a Sustainable Heritage Experience at Petra, Jordan. J. Tour. Cult. Change 2019, 17, 269–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bec, A.; Moyle, B.; Timms, K.; Schaffer, V.; Skavronskaya, L.; Little, C. Management of Immersive Heritage Tourism Experiences: A Conceptual Model. Tour. Manag. 2019, 72, 117–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bezova, K.; Azara, I. Generating and Sustaining Value through Guided Tour Experiences’ Co-Creation at Heritage Visitor Attractions. Tour. Plan. Dev. 2021, 18, 226–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, D.; Saxena, G. Participative Co-Creation of Archaeological Heritage: Case Insights on Creative Tourism in Alentejo, Portugal. Ann. Tour. Res. 2019, 79, 102790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kastenholz, E.; Gronau, W. Enhancing Competences for Co-Creating Appealing and Meaningful Cultural Heritage Experiences in Tourism. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2020, 1096348020951637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vythoulka, A.; Delegou, E.T.; Caradimas, C.; Moropoulou, A. Protection and Revealing of Traditional Settlements and Cultural Assets, as a Tool for Sustainable Development: The Case of Kythera Island in Greece. Land 2021, 10, 1324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trinh, T.T.; Ryan, C. Heritage and Cultural Tourism: The Role of the Aesthetic When Visiting Mỹ Sơn and Cham Museum, Vietnam. Curr. Issues Tour. 2016, 19, 564–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gálvez, J.C.P.; Fuentes Jiménez, P.A.; Medina-Viruel, M.J.; González Santa Cruz, F. Cultural Interest and Emotional Perception of Tourists in WHS. J. Qual. Assur. Hosp. Tour. 2021, 22, 345–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, T.; Zheng, X.; Yan, J. Contradictory or Aligned? The Nexus between Authenticity in Heritage Conservation and Heritage Tourism, and Its Impact on Satisfaction. Habitat. Int. 2021, 107, 102307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, J. The Contradictions between Conservation and Tourism in the Mogao Caves and Countermeasures. Dunhuang Res. 2005, 4, 7–9. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, J. The Management and Monitoring System for the Nature of the World Cultural Heritage Site. Dunhuang Res. 2008, 6, 114. [Google Scholar]

- Ashworth, G.J.; Tunbridge, J.E. Old Cities, New Pasts: Heritage Planning in Selected Cities of Central Europe. GeoJournal 1999, 49, 105–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beeho, A.J.; Prentice, R.C. Conceptualizing the Experiences of Heritage Tourists. Tour. Manag. 1997, 18, 75–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y. Institutional Approach of Self-Governance on Cultural Heritage as Common Pool Resources. Ebla Working Paper. 2010. Available online: https://www.css-ebla.it/wp-content/uploads/22_WP_Ebla_CSS.pdf (accessed on 27 February 2022).

- Yale, P. From Tourist Attractions to Heritage Tourism; Elm Publications: Huntingdon, UK, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Poria, Y.; Butler, R.; Airey, D. Clarifying Heritage Tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 2001, 28, 1047–1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Frame, B.; Liggett, D.; Lindström, K.; Roura, R.M.; van der Watt, L. Tourism and Heritage in Antarctica: Exploring Cultural, Natural and Subliminal Experiences. Polar Geogr. 2021, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Timothy, D.J.; Wang, Y.; Min, Q.W.; Su, Y.Y. Reflections on Agricultural Heritage Systems and Tourism in China. J. China Tour. Res. 2019, 15, 359–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, D.N.; Nguyen, N.A.N.; Nguyen, Q.N.T.; Tran, T.P. The Link between Travel Motivation and Satisfaction towards a Heritage Destination: The Role of Visitor Engagement, Visitor Experience and Heritage Destination Image. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2020, 34, 100634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salinas Chavez, E.; Delgado Mesa, F.A.; Henthorne, T.L.; Miller, M.M. The Hershey Sugar Mill in Cuba: From Global Industrial Heritage to Local Sustainable Tourism Development. J. Herit. Tour. 2018, 13, 426–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Wall, G. Heritage Tourism in a Historic Town in China: Opportunities and Challenges. J. China Tour. Res. 2021, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gnoth, J.; Zins, A.H. Developing a Tourism Cultural Contact Scale. J. Bus. Res. 2013, 66, 738–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silliman, S.W. Culture Contact or Colonialism? Challenges in the Archaeology of Native North America. Am. Antiq. 2005, 70, 55–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cusick, J.G. Studies in Culture Contact: Interaction, Culture Change, and Archaeology; Southern Illinois University Press: Carbondale, IL, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, H.; Rahman, I. Cultural Tourism: An Analysis of Engagement, Cultural Contact, Memorable Tourism Experience and Destination Loyalty. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2018, 26, 153–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B. Memory, Narcissism, and Sublimation: Reading louandreas-Salome’s Freud Journal. Am. Imago 2000, 57, 215–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.-Q.; Liu, C.-H. Impact of Cultural Contact on Satisfaction and Attachment: Mediating Roles of Creative Experiences and Cultural Memories. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2020, 29, 221–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seyfi, S.; Hall, C.M.; Rasoolimanesh, S.M. Exploring Memorable Cultural Tourism Experiences. J. Herit. Tour. 2020, 15, 341–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Havitz, M.E.; Dimanche, F. Leisure Involvement Revisited: Conceptual Conundrums and Measurement Advances. J. Leis. Res. 1997, 29, 245–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherif, M.; Cantril, H. The Psychology of Ego-Involvements: Social Attitudes and Identifications; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1947. [Google Scholar]

- Selin, S.W.; Howard, D.R. Ego Involvement and Leisure Behavior: A Conceptual Specification. J. Leis. Res. 1988, 20, 237–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Havitz, M.E.; Dimanche, F. Propositions for Testing the Involvement Construct in Recreational and Tourism Contexts. Leis. Sci. 1990, 12, 179–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witt, P.A.; Ellis, G. The Leisure Diagnostic Battery. Leis. Comment. Pract. 1984, 3, 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Bloch, P.H.; Richins, M.L. A Theoretical Model for the Study of Product Importance Perceptions. J. Mark. 1983, 47, 69–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Kim, H.J.; Liang, M.; Ryu, K. Interrelationships between Tourist Involvement, Tourist Experience, and Environmentally Responsible Behavior: A Case Study of Nansha Wetland Park, China. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2018, 35, 856–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, I.A.; Tang, S.L.W. Linking Travel Motivation and Loyalty in Sporting Events: The Mediating Roles of Event Involvement and Experience, and the Moderating Role of Spectator Type. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2016, 33, 63–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duerden, M.D.; Lundberg, N.R.; Ward, P.; Taniguchi, S.T.; Hill, B.; Widmer, M.A.; Zabriskie, R. From ordinary to extraordinary: A framework of experience types. J. Leis. Res. 2018, 49, 196–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos, A.C.; Mendes, J.; do Valle, P.O.; Scott, N. Co-Creating Animal-Based Tourist Experiences: Attention, Involvement and Memorability. Tour. Manag. 2017, 63, 100–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cevdet Altunel, M.; Erkurt, B. Cultural tourism in Istanbul: The mediation effect of tourist experience and satisfaction on the relationship between involvement and recommendation intention. J. Dest. Mark. Manag. 2015, 4, 213–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafaei, F. The Relationship between Involvement with Travelling to Islamic Destinations and Islamic Brand Equity: A Case of Muslim Tourists in Malaysia. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2017, 22, 255–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pine, B.J.; Gilmore, J.H. The Experience Economy: Work Is Theatre and Every Business a Stage; Harvard Business School Press: Boston, MA, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, Y.; Wu, K. From expectations to feelings: An interactive model for quality tourist experience. Tour. Sci. 2000, 2, 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Sun, G. Relic Park: New Industry of Tourism Development on Cultural Heritage Experience—A Case Study of Three Relic Parks in Xi’an. Hum. Geogr. 2012, 1, 142–146. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, G. Tourism Culture: Research Location and Disciplinary Framework. Tour. Trib. S. 1999, 1, 20–23. [Google Scholar]

- Kastenholz, E.; Marques, C.P.; Carneiro, M.J. Place Attachment Through Sensory-Rich, Emotion-Generating Place Experiences in Rural Tourism. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2020, 17, 100455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quan, S.; Wang, N. Towards a Structural Model of the Tourist Experience: An Illustration from Food Experiences in Tourism. Tour. Manag. 2004, 25, 297–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, G.; King, B.; Yeung, E. Experiencing Culture in Attractions, Events and Tour Settings. Tour. Manag. 2020, 79, 104104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.M.; Smith, S.L.J. A Visitor Experience Scale: Historic Sites and Museums. J. China Tour. Res. 2015, 11, 255–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Van Raaij, W.F. Expectations, Actual Experience, and Satisfaction a Reply. Ann. Tour. Res. 1987, 14, 141–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crompton, J.L.; Love, L.L. The Predictive Validity of Alternative Approaches to Evaluating Quality of a Festival. J. Travel Res. 1995, 34, 11–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bigné, J.E.; Andreu, L.; Gnoth, J. The Theme Park Experience: An Analysis of Pleasure, Arousal and Satisfaction. Tour. Manag. 2005, 26, 833–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, L.; Chi, C.G.; Liu, Y. Authenticity, Involvement, and Image: Evaluating Tourist Experiences at Historic Districts. Tour. Manag. 2015, 50, 85–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.-F.; Chen, F.-S. Experience Quality, Perceived Value, Satisfaction and Behavioral Intentions for Heritage Tourists. Tour. Manag. 2010, 31, 29–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dipietro, R.B.; Peterson, R. Exploring Cruise Experiences, Satisfaction, and Loyalty: The Case of Aruba as a Small-Island Tourism Economy. Int. J. Hosp. Tour. Admin. 2017, 18, 41–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suhartanto, D.; Gan, C.; Andrianto, T.; Ismail, T.A.T.; Wibisono, N. Holistic Tourist Experience in Halal Tourism Evidence from Indonesian Domestic Tourists. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2021, 40, 100884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tapar, A.V.; Dhaigude, A.S.; Jawed, M.S. Customer Experience-Based Satisfaction and Behavioural Intention in Adventure Tourism: Exploring the Mediating Role of Commitment. Tour. Recreat. Res. 2017, 42, 344–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratchford, B.T. The Economics of Consumer Knowledge. J. Consum. Res. 2001, 27, 397–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Gursoy, D.; Xu, H. Impact of Personality Traits and Involvement on Prior Knowledge. Ann. Tour. Res. 2014, 48, 42–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Xu, H. Cultural Heritage Elements in Tourism: A Tier Structure from a Tripartite analytical framework. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2019, 13, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gursoy, D.; Gavcar, E. International Leisure Tourists’ Involvement Profile. Ann. Tour. Res. 2003, 30, 906–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, J. Dunhuang Mogao Caves. World Herit. 2015, Z1, 26–31. [Google Scholar]

- Nie, F.; Qi, S. Dunhuang History, Culture and Art; Gansu People’s Publishing House: Lanzhou, China, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Hwang, H.; Malhotra, N.K.; Kim, Y.; Tomiuk, M.A.; Hong, S.A. Comparative Study on Parameter Recovery of Three Approaches to Structural Equation Modeling. J. Mark. Res. 2010, 47, 699–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M.; Mena, J.A. An Assessment of the Use of Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling in Marketing Research. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2012, 40, 414–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viet, B.N.; Dang, H.P.; Nguyen, H.H. Revisit intention and satisfaction: The role of destination image, perceived risk, and cultural contact. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2020, 7, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laurent, G.; Kapferer, J.-N. Measuring Consumer Involvement Profiles. J. Mark. Res. 1985, 22, 41–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, R.L. A Conceptual Model of Service Quality and Service Satisfaction: Compatible Goals, Different Concepts. Adv. Mark. Manag. 1993, 2, 65–85. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H.; Zhang, J.; Cheng, S.; Lu, S.; Shi, C. Role of Constraints in Chinese Calligraphic Landscape Experience: An Extension of a Leisure Constraints Model. Tour. Manag. 2012, 33, 1398–1407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Afsharifar, A.; van der Veen, R. Examining the moderating role of prior knowledge in the relationship between destination experiences and tourist satisfaction. J. Vacat. Mark. 2016, 22, 320–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Igbaria, M.; Iivari, J.; Maragahh, H. Why Do Individuals Use Computer Technology? A Finnish Case Study. Inf. Manag. 1995, 29, 227–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stylianou-Lambert, T. Gazing from Home: Cultural Tourism and Art Museums. Ann. Tour. Res. 2011, 38, 403–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calver, S.J.; Page, S.J. Enlightened Hedonism: Exploring the Relationship of Service Value, Visitor Knowledge and Interest, to Visitor Enjoyment at Heritage Attractions. Tour. Manag. 2013, 39, 23–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Dimensions | Items |

|---|---|

| Tendency | I like to learn about different customs, rituals, and ways of life I am very keen on finding out about this culture I would like to see the world through the eyes of people from this culture I like to spend time on finding out about this culture |

| Depth of contact | I like to experience more than just staged events associated with this culture I would like to get to know more about this culture I prefer just to observe how this culture is different rather than really meet and interact with people from that culture I am interested in getting to know more people from this culture The more I see, hear, and sense about this culture, the more I want to experience it |

| Involvement | I would like to get involved in cultural activities |

| Overall level of contact | Contact with these cultures forms a very important part of my experience in this visit |

| Culture Type | Introduction | Representative Elements |

|---|---|---|

| Historical legends | History of the construction of the Mogao Caves over the past thousand years, spanning different periods and dynasties; history of the exchange between Eastern and Western civilizations represented by the Silk Road; history of the discovery of the Cave of the Hidden Scriptures; and history of plunder and destruction in modern times. | Cave Construction, Silk Road, Cave Construction by Lezun, Xuanzang’s Journey to the West, Theft of Cultural Relics, etc. |

| Buddhist culture | The Dunhuang region was one of the earlier regions in China to which Buddhism spread. Dunhuang area’s romantic and exotic Buddhist culture was widespread. Shanghai Fine Arts Film Studio’s 1981 adaptation of The Deer King Itself and The Nine Colored Deer was widely acclaimed. In addition, the Buddhist culture of flying trapeze, musical dances, and the Thousand-Handed Goddess of Mercy were well known. | The nine-colored deer, flying trapeze, musical dances, the Thousand-Handed Goddess, etc. |

| Cave art | The Mogao Caves contain a comprehensive body of art that combines architecture, sculpture, and mural painting. The subject matter, formal techniques, and style of the Mogao Caves art are of great value and demonstrate that Chinese perspective, color, and architecture have reached a high level in the last thousand years. | Forms, styles, colors, and ideas of cave art. |

| Construct | Items | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Cultural tendency | I would like to know more about this culture. I am very keen on finding out about this culture. I like to spend time finding out about this culture. I am interested in meeting people who are familiar with this culture. | Chen and Rahman [30], Li and Liu [26], and Viet et al. [70] |

| Involvement | Visiting the Mogao Caves was a very important activity for me. I enjoyed visiting the Mogao Caves. I enjoy discussing my Mogao Caves experience with family and friends. Visiting the Mogao Caves is an expression of my interest. | Laurent and Kapferer [71] |

| Tourism experience | The caves, painted sculptures, and murals are fascinating to me. I learned something new from visiting the Mogao Caves. Visiting the Mogao Caves made me happy. | Pine and Gilmore [46] and Lee and Smith [53] |

| Satisfaction | Visiting the Mogao Caves was a satisfying decision for me. I am glad I visited the Mogao Caves. I would be happy to visit the Mogao Caves again. I would recommend visiting the Mogao Caves to others. | Oliver [72] and Zhang et al. [73] |

| Prior knowledge | How much did you know about the culture prior to your trip? | Huang et al. [74] |

| Characteristics | % | Characteristics | % | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 41.9 | Education | Primary and below | 3.25 |

| Female | 58.1 | Junior high school | 7.5 | ||

| Age | <19 | 12.6 | Senior high school | 10.0 | |

| 19–25 | 26.4 | Junior college | 15.75 | ||

| 26–35 | 25.2 | Undergraduate | 53.5 | ||

| 36–45 | 17.4 | Graduate | 10.0 | ||

| 46–55 | 12.6 | Income (CNY per month) | ≤1500 | 28.2 | |

| >55 | 5.8 | 1501–3500 | 11.4 | ||

| 3501–5000 | 19.8 | ||||

| 5001–8000 | 18.8 | ||||

| 8001–12,500 | 9.6 | ||||

| >12,500 | 12.2 |

| Construct | Items | Factor Loading | Cronbach’s α | CR | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cultural tendency | |||||

| Historical legends | I would like to know the historical legends of the Mogao Caves. | 0.859 | 0.784 | 0.874 | 0.699 |

| I am very keen on finding out about historical legends of the Mogao Caves. | 0.865 | ||||

| I like to spend time finding out about historical legends of the Mogao Caves. | 0.782 | ||||

| Buddhist culture | I would like to know the Buddhist culture of the Mogao Caves. | 0.881 | 0.875 | 0.915 | 0.729 |

| I am very keen on finding out about the Buddhist culture of the Mogao Caves. | 0.875 | ||||

| I like to spend time finding out about the Buddhist culture of the Mogao Caves. | 0.891 | ||||

| I am interested in meeting more people who are familiar with the Buddhist culture of the Mogao Caves. | 0.761 | ||||

| Cave art | I would like to know the art of the Mogao Caves. | 0.839 | 0.824 | 0.884 | 0.656 |

| I am very keen on finding out about the art of the Mogao Caves. | 0.848 | ||||

| I like to spend time finding out about the art of the Mogao Caves. | 0.833 | ||||

| I am interested in meeting more people who are familiar with the art of the Mogao Caves. | 0.713 | ||||

| Involvement | Visiting the Mogao Caves was a very important activity for me | 0.789 | 0.808 | 0.874 | 0.634 |

| I enjoyed visiting the Mogao Caves. | 0.783 | ||||

| I enjoy discussing my Mogao Caves experience with family and friends. | 0.797 | ||||

| Visiting the Mogao Caves is an expression of my interest. | 0.817 | ||||

| Tourism experience | The caves, painted sculptures, and murals are fascinating to me. | 0.807 | 0.783 | 0.874 | 0.698 |

| I learned something new from visiting the Mogao Caves. | 0.819 | ||||

| Visiting the Mogao Caves made me happy. | 0.878 | ||||

| Satisfaction | Visiting the Mogao Caves was a satisfying decision for me. | 0.836 | 0.844 | 0.895 | 0.681 |

| I am glad I visited the Mogao Caves. | 0.831 | ||||

| I would be happy to visit the Mogao Caves again. | 0.800 | ||||

| I would recommend visiting the Mogao Caves to others. | 0.832 |

| Construct | Buddhist Culture | Cave Art | Historical Legends | Involvement | Satisfaction | Tourism Experience |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Buddhist culture | 0.854 | |||||

| Cave art | 0.605 | 0.810 | ||||

| Historical legends | 0.569 | 0.583 | 0.836 | |||

| Involvement | 0.536 | 0.511 | 0.571 | 0.796 | ||

| Satisfaction | 0.354 | 0.319 | 0.432 | 0.580 | 0.825 | |

| Tourism experience | 0.355 | 0.401 | 0.440 | 0.556 | 0.706 | 0.835 |

| Hypothesis | Path | Path Coefficient | t-Value | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1a | Cultural tendency (Historical legends) → Involvement | 0.333 | 5.75 *** | Supported |

| H1b | Cultural tendency (Buddhist culture) → Involvement | 0.245 | 3.588 ** | Supported |

| H1c | Cultural tendency (Cave art) → Involvement | 0.167 | 2.882 ** | Supported |

| H2a | Cultural tendency (Historical legends) → Tourism experience | 0.143 | 2.203 * | Supported |

| H2b | Cultural tendency (Buddhist culture) → Tourism experience | −0.025 | 0.415 | Not supported |

| H2c | Cultural tendency (Cave art) → Tourism experience | 0.114 | 1.816 | Not supported |

| H3 | Involvement → Tourism experience | 0.430 | 7.596 *** | Supported |

| H4 | Tourism experience → Satisfactory | 0.706 | 22.313 *** | Supported |

| Moderator | Path | Group | N | Path Different (High-Low) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prior knowledge (Historical Legend) | Culture Tendency (Historical Legend) → Involvement | High | 207 | 0.150 | 0.222 |

| Low | 199 | ||||

| Prior knowledge (Buddhist Culture) | Culture Tendency (Buddhist Culture) → Involvement | High | 121 | 0.146 | 0.602 |

| Low | 285 | ||||

| Prior knowledge (Cave Art) | Culture Tendency (Cave Art) → Involvement | High | 182 | 0.307 | 0.055 |

| Low | 224 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Xu, L.; Zhang, J.; Nie, Z. Role of Cultural Tendency and Involvement in Heritage Tourism Experience: Developing a Cultural Tourism Tendency–Involvement–Experience (TIE) Model. Land 2022, 11, 370. https://doi.org/10.3390/land11030370

Xu L, Zhang J, Nie Z. Role of Cultural Tendency and Involvement in Heritage Tourism Experience: Developing a Cultural Tourism Tendency–Involvement–Experience (TIE) Model. Land. 2022; 11(3):370. https://doi.org/10.3390/land11030370

Chicago/Turabian StyleXu, Li, Jie Zhang, and Zhenghu Nie. 2022. "Role of Cultural Tendency and Involvement in Heritage Tourism Experience: Developing a Cultural Tourism Tendency–Involvement–Experience (TIE) Model" Land 11, no. 3: 370. https://doi.org/10.3390/land11030370

APA StyleXu, L., Zhang, J., & Nie, Z. (2022). Role of Cultural Tendency and Involvement in Heritage Tourism Experience: Developing a Cultural Tourism Tendency–Involvement–Experience (TIE) Model. Land, 11(3), 370. https://doi.org/10.3390/land11030370