Abstract

The transfer of urban development goals from two-dimensional land to three-dimensional space leads to the dilemmas of the functional adjustment of partial space in the building, such as an unclear property right system, vague land financial expropriation method, uncertain economic value, etc. This study aims to understand land-development-right pricing based on spatial characteristics in spatial function regeneration. Especially, we deal with the following questions: (1) How do we identify the spatial development rights and their pricing? (2) How do we develop an effective method to evaluate the value of local spatial-oriented development rights? Answering these questions helps to establish a sustainable land finance mode, which enables the public and private sectors to share the rising value of the urban functional adjustment. Thus, employing mixed methods, the study analyzes the characteristics of property rights and the economic value of spatial-development rights. We find the following: (1) The main institutional obstacle restricting local regeneration is the inconsistency between the local spatial ownership and use right of land. (2) The technical shortcomings of land finance result from the lack of an evaluation method of the spatial characteristics. Our study motivates the transition of urban economics from a two-dimensional surface to three-dimensional spaces. Meanwhile, for countries with similar land property rights and leasing systems to China, the study also provides a useful reference to deal with the property right and land finance issues in the renewal of local spatial functions.

1. Introduction

The current mode of urban construction in China has changed from being increment-led to revitalization-oriented, and urban regeneration has become the key to urban development. For example, according to The 14th Five-Year Plan (2021–2025) for National Economic and Social Development and the Long-Range Objectives through the Year 2035 issued in 2020, the Chinese government started to implement an action plan for urban regeneration [1]. At the same time, the Ministry of China’s Housing and Urban–Rural Development also published The Implementation of Urban Regeneration Action in its official media [2]. As the material concentration of society and economy, cities need to be renovated at different development stages [3]. Urban regeneration satisfies new demands of social and economic development by repairing the physical environment, changing the functions of land and buildings, adjusting the city capacity, etc. No matter which regeneration approach is used, the changes in economic interests are always accompanied [4].

Since 1987, China has implemented the land-leasing system with the compensated transfer of state-owned land-use rights to deal with the inefficient use of land caused by administrative allocation. By regulating the development right of land, urban planning promotes the proper utilization of spatial resources and maximizes their values. It is necessary to transfer land-use rights to serve as an implied right boundary of development rights [5]. Based on neoinstitutional economics, land-development right (LDR) is regarded as a limited ownership right, including developing and taping the land [6]. Meanwhile, the limitation and compensation of land right can solve the incongruity between the externality and benefits from unlimited development [7]. Therefore, the land-transfer price involves the consideration of the bundle of development rights, such as construction license, use-change right, and intensity-improvement right [8,9]. Local governments use land-price income to build infrastructure and provide municipal and public services, which to some extent offsets the negative externalities of land development [10]. In the incremental expansion era, although local governments have long had over-reliance on land finance, the capital cycle, composed of compensated transfer of land-use rights and profit from market development, has become a main driving force of economic growth in Chinese urban areas [11,12].

However, in the stock-regeneration era, the governments fail to rely on land increment to replenish financial funds by land-transfer fees, and thus they may lose an essential source of financial revenue [13]. Following this logic, the sustainable growth of urban economies would rely on the redevelopment of land and spaces. The process requires reshaping the economic relationship between the public and private sectors and seeking a capital cycle that conforms to the public interests [14]. Taking advantage of financial tools, such as the real-estate tax, value-added tax, etc., public sectors can share market benefits brought by spatial quality improvement with the private sectors [15]. At the same time, urban regeneration involves varieties of land adjustment, including land functions and development capacity, the renewal and redemption of land-use rights, and the transferability of allocated and sold land. All these adjustments require the property owners to pay land-transfer fees, or the governments to compensate or return part of the fees to the property owners.

Therefore, the essence of the above process is the repricing and transaction of land development right during urban regeneration [16]. The re-transaction of development rights is a market-oriented process of spatial allocation. A rational pricing approach that conforms to the characteristics of urban regeneration guarantees the balance of interests between public and private sectors and can reduce the transaction cost of property rights [17,18]. In addition, some cities, such as Shenzhen, have explored refined land pricing and expropriation approaches in carrying out the urban-regeneration system. However, due to the defects of the system, some transitional policies of deferring and exempting the transfer fees of land-use rights are employed to compensate for the institutional and technical immaturity [19].

Previous works in the literature pay more attention to the economic rules of two-dimensional plane space but ignore the property right attribute of space [20]. Actually, in the current urban regeneration, the smallest unit of function change is no longer all buildings on the land with independent property rights, but a certain floor or several floors of a building, or a part of the space in a certain floor. Thus, it is unclear whether and how the spatial development right at different spots on the same land or building are priced. In spite of the same function and capacity, the economic value may vary due to distinctive three-dimensional spatial combinations. Furthermore, in the progressive regeneration without large-scale demolition, the changes in function of a specific space are increasingly frequent [21]. However, the current land market usually determines the unit price of land development right based on the difference of location conditions on the two-dimensional urban plane, such as the distance from the plot to the trunk road, the degree of perfection of the surrounding infrastructure, etc. Furthermore, the current evaluation approaches of land pricing are inadequate to solve the issue of “different prices in the same place” caused by the spatial characteristics difference. Moreover, similar dilemmas exist in almost all countries and regions with the land leasehold system. Due to marketization, the prices of real-estate transactions in all countries are flexibly decided by buyers and sellers according to the supply and demand situations. However, when the transaction process involves the change in the development right of a part of the space on a piece of land, especially the change of the control conditions of functional use, the pricing approaches of how buyers and sellers should pay the government (or public sector) are still unclear.

Therefore, the aim of this study is to investigate the establishing conditions of spatial development rights and to seek a more market-oriented value-measurement method. Our study contributes to the existing knowledge in the following ways. First, we extend the object of property rights for the functional regeneration of local space into space above land. In other words, we amend previous studies where development rights can only be set up for land. In the study, the object of control, empowerment and change of development rights is transferred from land to space. Second, the study promotes the transition of urban economics on the value of development rights from focusing on two-dimensional planar location differences to three-dimensional spatial location differences. The transition can respond to the actual needs of urban built-up areas for renovation. Third, our evaluation approach emphasizes the matching development right value between space and function. Especially, our approach can form a sustainable land finance mode under the background of land stock development, which helps the public and private sectors share the value gains brought by the adjustment of the urban functional structure. Meanwhile, it will help to achieve property-rights transactions between private sectors, reduce the information cost of value evaluation, and enhance the market-oriented flow of space resources. Overall, the study will provide insights for the development-right transaction of spatial function regeneration.

2. Literature Review

The aim of this section is to understand land-development rights and their pricing approaches by reviewing previous studies. On this basis, we understand the dilemma and pricing practice with respect to China’s land development.

2.1. Development Right and Pricing Approaches

The development right is unused rights that allow developers to make changes to their property within the limitations imposed by the state or local law [22,23]. In 1944, the Town and Country Planning Act of Britain first formally defined the development right and proposed to compensate the landowners whose development rights were restricted [24]. Similarly, United States, Singapore, and China’s Taiwan also have relevant institutional arrangements for transferable development rights (TDR) [25]. Overall, the current explanation of development right is still nonexistent in the existing legal system [26]. The essence of current urban planning management is the definition and allocation of development rights [27]. Although China adopts the state-owned lease system of urban land, rather than the private land system, the right to land development is controlled by the government. For example, the United States controls the development intensity, functional use and building form of land by zoning. The UK also grants land-development rights based on statutory urban planning and does not allow arbitrary changes in land functions. However, unlike the United States, which strictly follows the zoning conditions for approval, the planning permission procedure in the United Kingdom gives the approver some discretion. The United States and Britain basically represent different land-development management and control modes of all Western countries [28]. Meanwhile, existing studies on urban planning have not yet distinguished the spatial-development right from land-development right. In order to deal with the distribution of interests among multiple property rights entities in the high-intensity development of large cities, Western countries represented by the United States have reached a consensus on the concept of air right, which is directly reflected in the common TDR system [29]. The core of the TDR system is to transfer part of the development rights of the land between the sending place and the receiving place. This type of right only specifies the transferable development volume. However, the existing literature on the right connotation and value evaluation method of the development right is not clear. In recent years, China has learned from the Western TDR system and carried out institutional innovation related to volume transfer in Shanghai and Shenzhen. In addition, the urban planning control in Western countries also reflects the implicit space-development right. For example, urban design control in the United States restricts the building form at different heights or different floors on the land. Specific functions can only be located on specific floors, for instance, the ground floor of the building must be commercial retail [30]. However, this implicit right restriction is usually only for the hierarchical control of building height, which is similar to China’s system of layered transfer and layered development of land-use rights.

When the space development right has not been fully discussed in the relevant research of urban-planning discipline, since the focus of the land-use method has changed from two-dimensional plane use to three-dimensional use, the legal field has attached importance to the definition of spatial-development rights. Furthermore, previous literature and reality have explored the right boundary by comparing it with land-development rights, as well as dividing the ownership of buildings, land-use right and space right [31]. They argue that space can be separated from the ground and be an independent object with specific rights [32,33]. However, there is a dispute about the category of spatial rights as a bundle of rights [34]. Because of different property rights’ institutional arrangements, the current research has not reached a consensus on the specific content of space rights. At the same time, because of the strict protection of private property rights, whether the government should extend land-development control to specific spatial locations, that is, from limiting and supplying land-development rights to space-development rights, is still a huge dispute [35]. In China, the planning authorities have significantly stronger control over the development of private land. They are very careful about the development and control of landmark buildings in the city and buildings in important areas. For example, they forced commercial buildings on adjacent plots belonging to different property owners to build air corridors for public use at specific heights. Such practices have reflected the restrictions on space-development rights. However, a few studies have realized that the source of government power is not clearly defined in law, resulting in legal risks at the administrative level [36]. Thus, the right to control three-dimensional spatial construction is included in land-spatial rights, while its understanding remains unclear.

Regarding the value measure of development rights, the pricing approaches of development right all over the world can be classified into four categories, named the definition of pricing methods (development/residual methods), non-market methods, market methods, and hypothetical market methods [37,38]. First, in the definition of the pricing method, the price is calculated by the land-price difference before and after the change of land-use type and then subtracting the cost [19]. The formula is usually adjusted according to the actual situation of the development-rights transaction. The price of the development right is the differential value between land-market valuation and valuation of restricted open space. Federal and state tax rates and donated amounts are taken into calculation in the calculation process [39,40]. For example, the discounted cash flow method (DCFM) regards the land-development right as capital to generate income [41]. Brach et al., advocated for the real options pricing method to calculate the value of development rights [42,43]. Valerie et al., adopted the perpetual annuity valuation method (PAVM) based on the land-use conversion model to measure the estimated land-revenue discount [44]. Tang suggested that the value of development rights can be measured with the present value of earnings method (PVEM) [45].

Second, the non-market method can be divided into the pricing model with constant land rent and the pricing model with value influencing factors. Based on the concentric circle theory, Sun et al., suggested the pricing formula based on the price of the development right of urban fringes, and the distance, such as from downtown to urban fringes, and the real estate to downtown, has become a decisive variable that affect the price [46]. In addition, the hedonic price method (HPM) is also employed to analyze the factors that affect the price of development rights of urban residential land, such as volume ratio, accessibility, distance from trade circles, etc. [47]. However, some other studies used HPM to investigate the characteristics of spatial changes before and after urban regeneration and to explore the spatial characteristics that yield externalities to the real estate value [48,49]. This method intends to identify the spatial location as a feature, but the feature variables in current literature are mainly two-dimensional locations [50]. Third, in countries with mature land-development-rights transactions, especially in places where land (transferable development rights) banks have been established, the large amount of transaction data makes market-led pricing development operational. Thus, evaluators can set a series of correction parameters on the basis of comparable prices to obtain a new price of right [51]. Fourth, the hypothetical market method is mainly based on the contingent valuation method (CVM) to reflect consumers’ preference for land. However, as a declarative preference method, the accuracy of this method is interfered by many factors, such as the questionnaire design and interviewees [52].

Overall, in reality, most of the land in Western countries is privately owned. The pricing of development rights is usually determined by the market, and the most commonly used are market methods. They determine the price by comparing it with similar transactions in the past. The government usually uses definition pricing methods to compensate private property owners because of restrictions on development rights. Relevant studies focus on exploring market disturbance factors (such as holding period, change of yield, and the reflection of different functional land on tax rate), and government and market big data fusion technology supporting land pricing [53,54]. However, in China, land is mainly supplied by the government. The price of the development right is determined by the planning authority based on the PVEM and multiplied by a series of correction coefficients in the evaluation of specific land. Therefore, the current studies mainly focus on expanding the type of coefficient and studying the price elasticity of coefficients by big data and regression statistics, that is, finding the impact and degree of different location conditions on land value [55]. However, all of them on development-rights valuation focus on land-resources management and land economics, with rigorous application of mathematical models [56], but little attention is attached to the spatial characteristics. At the same time, scholars of urban planning generally recognized that spatial characteristics are the key factors that influence spatial value, but quantitative studies on spatial value remain limited.

2.2. China’s Development Right Dilemma

According to the Law of the People’s Republic of China on Land Administration, the transfer, lease, and allocation of construction land-use rights must be accompanied by land use and planning conditions. The land-use right contains not only land usability and the land-usage term, but also functions of the development period and regulations, intensity, and form control [57]. China’s construction-land-use right includes the land-development right and its usage term. Thus, the price paid by the market for transferring land-use rights is a combination of the cost of the land-development right and its usage term. Policies at national level indicate that if the original land-use right specified in the contract is changed, including the transfer of land use and plot ratio, the land-price difference should be paid according to the regulations [58,59]. Therefore, the regulations have laid a legal foundation for land finance during the process of urban regeneration.

In China, property ownership is interdependent with the right of using the corresponding land. According to Real Rights in the Civil Code, if the right to use construction land is transferred, exchanged, contributed or donated, buildings, structures and ancillary facilities on the land shall be disposed of, together with the right. When the land is developed for the first time, developers tend to carry out construction according to additional land-planning conditions. In addition, they retain the ownership of all buildings after the construction or sell them separately. In this way, new property owners obtain shared ownership of the buildings. The relationship between shared ownership and complete right to use land in Real Rights in the Civil Code is implicit. However, based on The Law of the People’s Republic of China on the Administration on the Urban Real Estate, the obligations specified in the land-use-right-transfer contract are transferred together with the rights, when the real estate is transferred [58]. In Chinese management of real-estate registration, the right to use apportion land area of the shared ownership is also well-defined in the real-estate ownership certificate, indicating that the complete right to use land is redistributed to shared owners in the ownership transaction. Therefore, when the upper-level planning is changed, the existing legal foundation for the shared owners and the government can be used to re-sign a transfer contract of the right to use specific spaces. Thus, new owners can renew their properties. The premise of the second property right transaction is the reasonable pricing of the local space separated from the land.

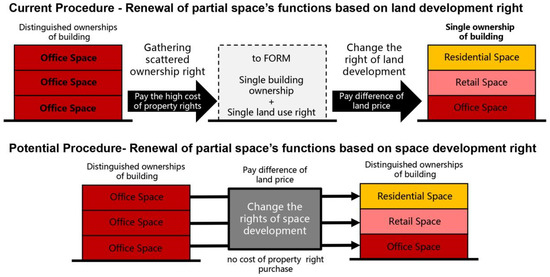

Due to the lack of relevant provisions in current upper-level laws, the separated right to use land included in the separated ownership of buildings is unrecognized. The property-rights exchange, functional changes, and regeneration of the right to use land are attached to the transfer of the right to use specific lands. In the conditions, the current urban regeneration methods with less large-scale demolition and construction, which seem to be hindered by state policies, become a reaction due to the imperfect property-rights system. Furthermore, only by redeeming and merging common property rights can developers be allowed to change the land-use right. Take the popular urban regeneration methods with multi-functional spaces as an example. In a single-function office building, if the upper-level planning allows the ground floor spaces to be renovated into retail spaces or some floors to be transformed into long-term rental apartments, transferring the right to use local spaces will be hard to achieve. Transferring the land-use right of the property plot can reflect such changes, while individuals with shared ownership are not qualified to be property subjects [60]. Therefore, as shown in Figure 1, the only way to change the right to use land is to purchase the property rights of all buildings on the land.

Figure 1.

Procedure of function renewal based on different property rights objects (source: authors).

In some cities, by changing the spatial-development rights, real estate is allowed to be registered according to the new functions and service life or acquiesces. On the one hand, the practice of local governments involves legal risks for the government because they ignore the fundamental role of land-use-rights management for secondary development. On the other hand, it is a challenge to obtain the due land income from the value change caused by the transfer of local space property rights. For local spatial owners who want to renew their spaces, unclear property rights information may cause inconveniences in business registration, business license, and asset valuation [61]. To conclude, a limitation of Chinese progressive urban regeneration from the central to the local government is the imperfection of the property-rights system. The achievement of the property-right exchange in turn interdepends on the effective valuation of spatial-development rights.

2.3. China’s Development Right Pricing Practice

The valuation approaches at the technical level are clarified into regulations for valuation on urban land and technical specification for price evaluation of land-use-right transfer of state-owned construction land. Insufficient attention has been paid to spatial characteristics and mixed functions in the five basic valuation methods simultaneously, including the market comparative method, income capitalization method, residual method, cost-approaching method, and coefficient-correction method of benchmark land price (Table 1). They are insufficient because the measure target remains the sum of all development rights on the land [62,63]. Regulations for the valuation of urban land point out that if there are existing independent rights in above-ground, surface, and underground of the same land, the prices should be evaluated respectively according to the boundaries, rights ownership, profitability, and property-rights restrictions. In evaluating the rights of the above-ground spaces, the valuation process should consider spatial usage type, influence on surface spaces, location conditions, spatial accessibility, air restrictions, etc. If the above-ground spaces affect the utilization of the surface spaces, the obstacle compensative method can be employed for evaluation.

Table 1.

Major valuation methods for construction land.

As for the rights of independent underground spaces, the valuation process should consider underground use, depth, hydrogeological conditions, and the influence of underground construction on the surface and above-ground spaces. The above-mentioned regulations on the pricing of layered construction-land-use right form a connection with the Civil Code of the People’s Republic of China. It regulates that construction-land-use rights could be divided into above-ground, surface, and underground rights. These policies have served as pricing support for the transfer of layered spaces rather than the whole land [62]. However, due to weak theoretical guidance and few measure methods, the price evaluation remains unpractical, which leads to difficult implementation to local governments. For example, the market comparison method may result in unclear pricing of the stratified space right because of difficult quantification in the selection of comparative samples and the individual factors brought by spatial characteristics. In general, the current land-oriented system and techniques born in the increment-led age fail to meet the spatial-oriented pricing needs of property-rights transactions in the stock regeneration era.

Although the current pricing technical regulations at the national level are not perfect, some positive explorations have been made at the local level. The relationship between commercial functions and floors is considered in the current land-valuation rules of local governments. The correction coefficient is formulated as well. For instance, in Shenzhen, the land valuations of the second, third and fourth floors and above are only 60%, 50%, and 40% of that on the first floor [64]. In addition, the relationship between underground space and its functions is taken into consideration. In Beijing, the land valuations of underground offices, warehouses, and garages are only 20% to 30% of that of above-ground space. The land valuation of underground commercial space is lower than the depth of underground floors [65]. Guangzhou also prices floors with residential and other functions according to their positions in the buildings. In Guangzhou, if the land value of the 8th floor in a residential building with a total height of 18 floors is evaluated at 100%, the floors above the 8th floor are priced higher 100%, in which the price increases with the floor height and vice versa. However, the pricing-correction coefficients of the top floor 18th and the second top floor 17th are 103.4% and 104.2%, respectively, because the top floor is exposed to severe sunlight and risk of leakage [66].

The above-mentioned refined valuation method still echoes the market rules. If the land is sold for the first time, it is more convenient to calculate the difference in the development right value caused by the plot planning. In this way, the exchange price of the development right is closer to the fair market value, which would reduce exchange costs for both the public and private sectors. In the progressive local regeneration, the value of spatial-development rights with different functions in different vertical positions can be estimated with a series of correction coefficients. The process would help to realize the secondary transfer of the right to use local space. This method is only practiced in a few cities with advanced land-value-management systems. Even in some advanced cities such as Beijing, Shanghai, and Shenzhen, functional types of land-value correction caused by spatial factors remain limited, because they only adjust the floors with commercial functions. The published land-value correction system lacks a flexible updating mechanism. The calculation of the correction range is merely determined by the benchmark land value and the extreme land value within the region without the comparison of the multi-point market price. It is not precise enough.

3. Methodology

3.1. Study Area

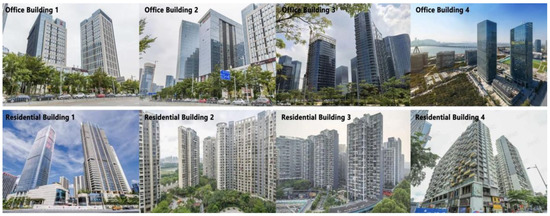

In the study, the coastal area in the downtown Bao’an district, Shenzhen, is selected as the empirical case (Figure 2). The study analyzes the value of the development right of office buildings in the selected area, and it is partially renewed into residential spaces. According to the Urban Master Plan of Shenzhen, Bao’an Central District is one of the city’s double centers, while the coastal area is the core of Bao’an district (Figure 3). It is a concentration of administrative, commercial, cultural, and sports functions with an area of 6.82 square kilometers [67]. In 2016, Shenzhen’s urban regeneration policies clarified three regeneration measures, including demolition and reconstruction, functional regeneration, and comprehensive improvement [68]. Functional regeneration refers to changes in the function of all or part of the building in retaining the original building structure. Thus, the practice in Shenzhen indicates the operability of changing the local functions of buildings.

Figure 2.

Location of study area (source: authors).

Figure 3.

Typical office and residential building in Bao’an district. The figure belongs to the following source: Beike Housing. Available online: https://bj.ke.com (accessed on 18 August 2022).

The vacancy rate of office buildings in Shenzhen has continuously risen. In 2021, the vacancy rate of Grade A office buildings in Shenzhen reached 22.7%, and that in Bao’an Central District reached 40% in 2020 [69]. Shenzhen, the city for start-ups in China, has always concentrated on the internet, finance, and high-tech industries. Among the 17.682 million population in Shenzhen, 3.85 million are commercial entities1. The huge amount of business activities activates the short-term oversupply of office land, resulting in an insufficient supply of residential land. In Shenzhen, the proportion of residential land only accounted for 22.6% of construction land by 2020, which is lower than the lower limit of 25–40% in the Code for Classification of Urban Land Use and Planning Standards of Development Land [70,71]. Additionally, Shenzhen’s per capita residential area is only 27 square meters, ranking the lowest among China’s super-first-tier cities. The shortage of residential land leads to high housing prices in Shenzhen. In 2019, the average price of second-hand houses (CNY 65,516/m2) in Shenzhen surpassed Beijing for the first time, ranking the first among China’s cities. The latest average price of first-hand houses in Xixiang street, where the studied coastal area is located, reached CNY 74,361/m2.

Due to the unbalanced supply-and-demand relationships between office and residential land, Shenzhen municipal government issued Measures for Further Increasing the Supply of Residential Land (Exposure Draft) in July 2021 [72]. It proposes that in the future, Shenzhen will gradually increase the scale of residential land and public facilities and ensure that the per capita housing area of permanent residents reaches over 40 square meters by 2035. It also encourages the regeneration and transformation of existing office buildings into residential or long-term rental apartments. Overall, our case is a rational choice, which will make a difference to the economic valuation of the partial change from office buildings into residential space. These also meet the needs of urban regeneration.

3.2. Methods

This study argued to separately estimate the valuation change of the development right of spaces in urban regeneration, instead of carrying out the valuation based on the average floor. It results from the different implicit matching degrees between spaces and their functions, producing distinctive economic disparity. The location theorists represented by Von Thunen and Alonso pay great attention to the two-dimensional changing rules of urban bid rent [73,74]. However, in the three-dimensional urban development at the micro-level, residential, commercial, and public-service functions as well as specific industries have relationships with spatial attributes, which involves floor height, accessibility, and privacy [75,76]. The valuation of the development right caused by the change of local function is the different land values before and after changing the use type of local buildings. Therefore, the residual method advocated by the Technical Guidelines for Land Price Evaluation of the Transfer of State-Owned Construction Land Use Right is a more suitable choice. The formula is as follows:

where is the government’s pricing of local spatial development right during urban regeneration. and refer to the value of development right after and before the local spatial regeneration, respectively. They reflect how the matching degree between new functions and spatial location affects the price. is calculated according to the spatial price before the second property rights exchange, instead of the floor price of the first land transfer. This indicates that the price of the development right in urban regeneration excludes the value change of the renewing spaces, due to macroeconomic and other external factors since being initially constructed. Instead, the price is measured only by the change of the spatial value due to the property-rights exchange. The disparity between and may be positive or negative. A positive income for the property owner after the regeneration may encourage the owner to renew the local space, where the public sectors capture benefits from the spatial renewal. On the contrary, a negative income requires economic compensation from the public sectors to private ones. refers to the institutional cost of local spatial regeneration, including the extra tax that the property owners pay to the public sectors at the secondary transfer of local spatial land. The real-estate value-added tax is an example where the government regulates the regeneration of different functional spaces by fiscal tools.

The time efficiency and market are important issues during the valuation of spatial rights through the residual method. Therefore, the coefficient-correction method of the benchmark land price is inappropriate for estimating the value of and due to the time lag of periodical publishing. In addition, the correction-coefficient system is a one-size-fits-all approach, which is difficult to reflect the influence of spatial location on the value of spatial rights in different urban areas. Similarly, the land capitalization rate, the core parameter of the income capitalization method, also lacks time efficiency and flexibility. In practice, the rate is determined by the annual loan interest rate of the People’s Bank of China, which fluctuates with the different proportions of the function types. As for the cost-approaching method, it is excluded since it only fits newly developing and underdeveloped lands or land with few transactions [62]. Thus, through analysis, the market comparative method is better because progressive local regeneration usually occurs in the urban areas. The real-estate market is relatively mature, and the real-estate transaction samples of different functional spaces are easier to obtain in these urban areas. However, the price-correction approaches of this method, including the exchange index and regional factor index, ignore the matching degree between the spatial characteristics and spatial functions.

Therefore, this study advocates HPM to measure the price impact of spatial characteristics, which is suitable for processing the vast data of actual market exchange and for reflecting the influence of spatial location. The fundamental logic is that the property is regarded as a heterogeneous product, whose value consists of a complex variety of attributes (e.g., locational attributes) [50]. This method has been widely used to estimate the implicit price of commodities with specific attributes [77]. Based on the theoretical framework of hedonic price analysis [78], the HPM formulas are shown as follows:

where Equations (2)–(5) are the deformation of basic Equation (2). They are a logarithmic function, logarithmic linear function and semi-logarithmic function, respectively. These three deformations are usually used to examine the elasticity of price changes caused by changes in product characteristics. However, the purpose of this study is to directly measure the specific implicit price of spatial characteristics. Thus, we exclude Equations (3)–(5), and select Equation (2). is the price per unit area and a constant term. It is the main real-estate price of different functional spaces determined by the supply-and-demand relationship of the regional market. This is the price based on the valuation method in Table 1 and is not affected by spatial characteristics. refers to property rights and spatial characteristics in year, including the floor, spatial orientation, and mixing degree of functions. is the implicit price of different characteristics. ε is the error term. In progressive local regeneration, when the government re-confirms property rights and carries out the exchange between public and private sectors, only the change of spaces functions and the years of property rights may affect the real-estate value. Therefore, the value of development rights results from the disparity of the real-estate value before and after the regeneration measured by the HPM.

Equation (2) is widely used in land and property valuation and is very intuitive. However, the linear regression based on the ordinary least square (OLS) is difficult to achieve the best fit due to ignoring the spatial interaction between the research samples. Thus, the spatial error model (SEM), spatial lag model (SLM) and geographically weighted regression (GWR) based on local space are widely used in existing studies to improve the classical HPM model. SEM mainly aims at the situation in which independent variables affect other regions through regional random spillover. It realizes the quantitative simulation of the spatial transmission mechanism of determinants of the dependent variables by modifying the error term of OLS [79]. It is as follows:

where is the dependent variable. is the independent variable, and is the coefficient of the independent variable. is the autoregressive parameter. is the spatial weight matrix, and is the error term. is the regression residual vector, which meets the expectation of 0, and the variance is the normal distribution of .

SLM is mainly aimed at the case that the independent variable is used in other regions through the spatial conduction mechanism. It adds an explanatory variable multiplied by the spatial proximity matrix. The regression coefficient of this variable can be used to judge the significance of SLM, and its expression is as follows:

where is the dependent variable. is the independent variable, and is the regression coefficient of the independent variable. is the spatial autoregressive coefficient, and is the spatial weight matrix. is an error term.

GWR is to add the spatial location of the sample into the model. For each sample point, it uses the spatial weight function and bandwidth to determine the most appropriate local spatial range, and then constructs the local regression model. This can be used to judge the difference in the impact of different variables. The specific formula is as follows:

where is the average rent in office buildings . and respectively represent the slope and intercept of the regression model established by GWR at . shows the number of independent variables, and represents the regression residual of the model at .

The commonness of the above methods lies in the introduction of spatial weight matrix to deal with spatial autocorrelation. The aim of constructing a spatial weight matrix is to realize local regression by quantifying the distance and adjacency between samples. However, the method explored in this study focuses on variables of three-dimensional space, such as floor, orientation, etc. In the theoretical consistency, these variables conflict with the spatial weight matrix representing the locational relationship in the two-dimensional plane. At the same time, this study aims to provide a reference for pricing the spatial-development rights of local governments. The mean obtained from the global regression of the classical HPM can provide pricing guidance for the relatively homogeneous areas in a city and facilitate the formulation of price standards for regional rights changes. However, the model introducing spatial weight matrix needs to determine the spatial weight of each real estate to be priced, which is too costly for actual land price management. Overall, the above seemingly more advanced models cannot explain the difference in the value of development rights resulting from the three-dimensional space features, and their operability is poor. Therefore, they are excluded.

3.3. Variables Selection

Employing HPM, there is considerable domestic literature that estimates the determinants of real-estate prices, including height, floor area, age and other building characteristics [80,81]. Additionally, neighborhood characteristics, such as the number of surrounding schools, commercial services, and public transportation, are also considered in existing studies [82,83]. They measure the influence of city locations, including the distance from downtown, airport and other sizeable external transportation facilities [84,85]. In conclusion, the previous literature concentrates on the impact of two-dimensional locations on real-estate prices in cities. The selected method in this study narrows the range of the comparative samples and lessens the impact of locations, which helps to focus on the differences of three-dimensional spatial characteristics in a relatively micro area. In particular, the study filters factors affecting local spaces of office and residential areas with expert advice. The opinions of eight experts from the fields of architect design, urban planning, real-estate marketing are integrated to construct a variable set for these two functions, respectively. To ensure that the interviewed experts understand the purpose of variable selection, we first explain the basic definition of space development right and our pricing method to them. Then, we give the pre-selected twenty-two characteristic variables based on existing studies. In addition, experts are invited to classify these variables as “important” and “unimportant”. We discard the variables that eight experts agree are not important. Because our subsequent model establishment adopts the method of multiple stepwise regression, we also exclude variables with weak correlation based on statistical indicators. All in all, the purpose of this action is to exclude those variables that do not conform to the basic cognition and laws, or do not conform to our pricing logic, but may show strong correlation in statistics.

As shown in Table 2, according to the current land leasing regulations in China, the residential property right is automatically renewed without charges after expiration. However, other urban functional lands may be recovered or be required to pay the land-leasing fee for regeneration. Therefore, when estimating the value of office spaces, the remaining tenure of use (X0) presents an essential feature. The matching degree between office functions and three-dimensional spaces is reflected by floor No. (X1), total floors (X2) and orientation (X3). Owners’ preference for different scales and types of office spaces is indicated by property right area of the sales unit (X4), standard area per floor (X5), floor No. of the sales unit (X6), and whether the sales unit can be shared (X7). For instance, small- and medium-sized enterprises prefer smaller units in large office buildings, resulting in high market rent and sales. Volume rate (X8) represents the overall development intensity and density of the building land. The service area per car (X9) and service area per elevator (X10) indicate the influence of building facilities on the local spatial service level. The proportion of business retail area (X11) refers to the convergence of commercial and office space in a building. The retail space provides convenient services, which helps to improve the real-estate value. Whether there is coastal landscape (X12) is another factor that significantly influences the regional property value. The affecting factors of residential spatial value are illustrated in Table 3, in which factors such as floor No., total floors and property area are the same as those of office spaces. The only difference is that the property of residential space is automatically renewed so that the remaining tenure can be ignored. Two spatial characteristics, architectural form (X25) and unit structure (X26), are taken into consideration. The service areas per car and per elevator are adjusted into the household number (X28, X29); the household parking number is now a key factor to measure the facilities of residential land. The grade of residential buildings in China is usually measured by two apartment types: an apartment with one staircase and several apartments with one staircase [86].

Table 2.

Factors affecting office spatial value.

Table 3.

Factors affecting residential spatial value.

3.4. Data Collection

In this study, the web crawler function of R studio software is used to fetch last year’s large-scale data of office and residential real estate in the coastal area listed on the websites of China’s real estate agencies, including Beike and Fangtianxia. The consistency of space and time is the core premise of the data collection. After collecting trading or listing price examples and analyzing them via the regression algorithm, the HPM studies the of different functional spaces and the price impact caused by the matching degrees between spatial characteristics and functions. Therefore, the influence of urban locations, such as public service and traffic, should be ignored, and the geographical scope of the selected example should not be too large. If the urban location within the scope is also consistent, the same basic price can be obtained. With the actual situation in China, key location conditions, such as school districts, should be given special attention. Although the selected examples are close to each other in physical distance, their public service conditions may significantly vary due to administrative intervention.

For this reason, while identifying the geographic scope, spaces within the same administrative boundaries, including blocks and streets, are preferred due to the more consistent conditions. In addition, since the real-estate prices in different cities in China have changed greatly in recent years, attention should be paid to listing or trading examples with consistent timing. In the current valuation of construction land, the China real-estate index and the national real-estate industry prosperity index are frequently used in correcting the fluctuation of real-estate prices at different times. However, the samples may also suffer from some shortcomings, such as difficulty in reflecting price changes in specific cities and areas, lag in compilation time, inaccurate fixed weighting coefficients, etc. [87]. Thus, during the valuing process, the listing or trading time of the samples should be within a month or a quarter while ensuring the scale of collected data in order to fill the gap of lessening the impact of time. Meanwhile, attention should be paid to rigid policies, such as real-estate purchase restrictions, to avoid political impact on land value.

Therefore, our sample period is within one year after the policy of increasing housing supply in July 2021 to avoid the impact of fluctuant real-estate value and rigid guidelines. The selected coastal areas are all located within the unified administrative boundary of Xi’xiang street, Bao’an district, Shenzhen. Thus, we assume that all spaces in this area enjoy the same urban public service. After obtaining a large amount of structured numerical and text data (the variables listed in the previous section), in this area within one year, we process the data as follows. Firstly, the social residential property and villa are excluded from the obtained data. Then, the researchers manually check and delete the repeated information of two functional spaces. Secondly, the researchers make up missing information of the listed properties through the properties’ website or by calling the building property-management companies, such as volume rate and the number of elevators, and evaluate the retail area and whether there is coastal landscape. Third, we standardize the data of text information, such as qualitative words and descriptive sentences (e.g., spatial orientation and commercial facilities perfection). Finally, as shown in Figure 4, 575 pieces of valid data are obtained, including 190 spaces of 6 buildings in the studied area and 385 spaces in 36 communities.

Figure 4.

Distribution of samples (source: authors).

4. Results

Our analysis aims to verify the difference of real estate value with different functions on the same spatial location. On this basis, we identify the impact of spatial locations on the economic value of development rights in three-dimensional urban developed areas and explain the limitation of the current valuation method of rights. In this section, the multiple linear regression method is used to analyze the relationship between the value of the two functional spaces and different spatial characteristics. Stepwise regression is employed with the unit price per square meter as the dependent variable. Then, we introduce the independent variables to test the statistical significance until no insignificant independent variable is eliminated from the regression model. To avoid the influence of multicollinearity, the VIF test is carried out. The VIFs of all variables in the final models are less than 10. Through the VIF test, we find that there is still a relatively small correlation between some variables selected previously. For example, the later the residential area is built, the more parking spaces per household there will be. Although the more stringent VIF test standard is lower than 5, we believe that the variables mentioned above belong to different spatial characteristics. In order to better reflect the impact of different spatial characteristics on prices and obtain a model that is closer to reality and has a better fit, we choose the general VIF standard, which is less than 10 [88].

In the price modeling of office spaces (Table 4), there are overall nine fitted models, and seven variables were included in the final models, namely, remaining tenure of use (X0), floor No. (X1), orientation (X3), the standard area per floor (X5), whether the sales unit can be shared (X7), the volume rate (X8), and the proportion of retail area (X11). F values of the hypothetical tests are 129.728, 101.696, 72.751, 56.288, 47.988, 43.078, 37.694, 33.668, 38.528, respectively. The P value of the fitted models is lower, 0.001, indicating the significance of this model. With the increasing number of variables, the R2 and the adjusted R2 of each model show an upward trend, while model 9 indicates a decreasing trend. The adjusted R2 of each fitting model is greater than 0.5. Therefore, the price model of office spaces is established:

Table 4.

Results of the price model of office spaces.

Based on Model 13, the basic price per square meter of office space in this area is RMB 50195.3, while the mean and median prices of the sample are RMB 59170.7 and 57576.4 respectively. The difference is mainly caused by the variables representing property rights and spatial characteristics in the model. The office space in the area was built in 2010, and the remaining service life ranges from 32 to 38 years. The large value of variables makes the product of the remaining tenure and its implied price play an important role in the property value. In addition, the larger standard floor area has become the preference of consumers, which also has a positive impact on the property price. In our case, the standard floor area varies from 1300 square meters to 3600 square meters, indicating great changes. The larger standard floor means that the internal layout of the office space is more flexible, and more in line with the office needs of large enterprises with stronger payment capacity. The variable, whether the space can be divided and confirmed as multiple independent property units, can influence the space price, reaching RMB 9433.5. Being able to split means that real-estate investors can flexibly produce space products according to the preferences of different consumers during the second sale.

This right of free choice at the property level has formed value. The retail industry plays a supporting role in office space and has a greater impact on the appreciation of real estate. Whether the functions can be mixed depends on the definition of the original land development right. Whether or not the space faces south determines the natural lighting conditions of the property. However, for office spaces that use artificial lighting all year round, the spatial characteristics have relatively little impact on the price. Unlike the above variables, the higher floor has a negative effect on price. The office buildings in this area are mostly super high-rise buildings, with floors ranging from 20 to 47. The vertical accessibility of these super high-rise buildings has a negative impact on the three-dimensional accessibility of office space, and thus, the office space with a low floor is more favored. In addition, the plot ratio represents the development intensity of the land and means the population density per unit land area. Although the total land value of low-density development is low, the model shows that the price appreciation of office space per unit area is higher.

In the price modeling of residential spaces (Table 5), there are six fitted models, and six variables are included in the final models, namely, floor No. (X21), total floors (X22), property area of the sales unit (X24), unit structure (X26), household service number per elevator (X29) and whether there is coastal landscape (X31). Fs of the hypothetical tests are 44.39, 26.23, 19.3, 16.09, 13.95 and 12.23, respectively. The Ps of the fitted models are lower, 0.001, and the adjusted R2 of model 3 to model 6 is greater than 0.5. Therefore, we can obtain the following price model of residential spaces:

Table 5.

Results of the price model of residential spaces.

Model 14 indicates that the basic price per square meter of residential space in this area is RMB 59,665.7, while the mean and median prices of the sample are RMB 72,318.2 and 68,596.3, respectively. Whether the living space has coastal landscape has become an important factor to determine the real estate price. Its price appreciation reached RMB 24,781.2. These two variables, the floor where the space is located and the total floor of the building, have become important preferences of consumers in this area. In other words, high floors lead to a better view, which increases property prices. However, this preference is diametrically opposite to the office space. That is to say, low accessibility to three-dimensional space of the high-rise building is no longer the decisive factor affecting the price. In addition, the influence of the house type structure is also more important, and flat floor residences are more favored by consumers than duplex residences. The number of households on each floor served by a single elevator has a positive impact on the price, but the degree is not strong. This result is consistent with consumers’ preference for the number of floors in residential space. The only variable with negative influence in the model is the area of unit property right sold. The total price of the smaller residential space is lower, which is more consistent with the affordability of the middle class in the area. Furthermore, for smaller residential space, it is easier to lease and resell the property.

After substituting models 13 and 14 into model 8, model 15 is generated, which is a valuation model of the development right when the office spaces in coastal area is renewed as residential spaces:

The primary profit brought by the office spatial regeneration into residential spaces per square meter is RMB 9470.4, which may increase or decrease due to different spatial characteristics, such as the floor No., the orientation, the total floors and the view of the landscape. The difference may result from the different matching degrees between functions and spaces. Although these variables, such as floor No. and total floors, are consistent before and after the regeneration, the customer’s willingness to pay for these characteristics is significantly different. In the transfer process of property rights, although the physical structure of the building is maintained, the functional change directly leads to different spatial values. Therefore, it is reasonable for the government to push the property owner to redeem the development right based on the corresponding valuation.

However, the added value caused by the regeneration engineering and design should not be contained in the values of some variables of model 11, such as the apartment structure, the property area of the sales unit, and the household service number per elevator. Because the common floor area of an office building is generally larger than that of a residence, it is usually necessary to carry out spatial partitions during the residential regeneration. Developers who can better meet the market demand benefit more. Functional constraints do not directly lead to added value. For levying the land use fee, the government should transfer this potential income to the market, which may encourage a spontaneous and market-oriented adjustment of the urban functional structure. Thus, the average housing area and standard apartment layout are preferred as the substitution in the calculation practice. Additionally, the government can carry out precise regulation of different functions and regions by C value assignment in the formula. This can promote the regeneration of over-supply functions to functions in short supply and adjust the structure of urban spatial functions. If an office is transformed into a retail area, there will be a higher cost of fire protection, building partition, hydropower and new gas pipelines. In this case, the governments can ease the developers’ burden by reducing or eliminating part of the development rights fee, that is, the supplementary payment for land use rights, to ensure an active market investment.

5. Discussion

The current land valuation method is based on the calibrated land price and correction coefficients, which only involves seven kinds of correcting situations, namely correction of land use right term, correction of property right condition, correction of industrial development, correction of industrial project types, correction of above-ground commercial areas. At the same time, this is the current land price measurement method in almost all Chinese cities, and the influencing factors (correction coefficients) considered in land price measurement in most other cities are not as comprehensive as those in Shenzhen. There are two core defects in the current method: Firstly, the update of the calibrated land price lags with large granularity, which makes it difficult to timely reflect the change in land price in small units. Secondly, the matching degree between different functions and spaces is ignored, which makes it difficult to reflect the market fair value of local spaces when they are engaged in various functions. Rough land valuation may cause so-called windfalls and wipeouts in economics [89], resulting in a market imbalance of new stock spaces. Market capital may flood into the regeneration projects with excessive returns, while the projects with low returns may be ignored. However, the method proposed by this study is based on the actual market price of homogeneous land in a short period. Furthermore, we highlight the influence of spatial location. Thus, it is a more accurate method for estimating the development right value of local spatial function changes.

The aim of urban regeneration is built-up spaces, instead of vacant land. The current system of land development rights takes land as an urban regeneration unit to carry out property consolidation, development rights transfer and renewal construction. This restricts the efficiency of local functional regeneration of urban spaces and fetters the convergence of different functional spaces. However, the previous studies on urban planning have not yet taken refined spatial governance into consideration. There is no distinction between the development rights of spaces and land. Therefore, our methods’ purpose can be classified into two aspects. First, based on urban planning, it distinguishes the ownership, use and development rights of land and spaces, as well as the connotation of specific subdivision rights included in spatial development rights as a bundle of rights. The purpose of pricing has undergone fundamental changes, which is used to satisfy the requirements of refined spatial governance in urban regeneration. Second, by clarifying current regulations on spatial development rights and property rights, our approach puts forward a primary valuation method of rights to develop three-dimensional space instead of two-dimensional land. The measurement of space value-added brought by functional change can help to establish a sustainable land finance mode.

In addition, our perspectives and methods are in reference to other countries. China’s land system adopts the state-owned land lease model. The development right of land is tied to the use right. Although land in most Western countries is generally privately owned, the development and construction of these lands are all restricted by politics of urban planning. For example, in the UK, the types of land property rights are divided into perpetual ownership and leasehold. Perpetual ownership means that the subject of property right always owns the ownership of the land, while the leasehold only gives the owner the right to use the land for a certain period of time. No piece of the two kinds of land can be developed for any function or capacity by the owners without permission. Urban planning supported by law is not only a technical means to determine the urban spatial layout, but also a secondary distribution mechanism of property rights. When the function of the existing buildings or the internal space on the land changes, the development right changes accordingly. The change of property rights means income or loss to landowners and real estate owners. Whether the value added is shared by the public sector or returned to private owners, their purpose is to promote urban regeneration. In the United States, France, Germany and many other Western countries, the annual collection of value-added tax is used to solve the private and public interest distribution caused by property appreciation. The value added brought by the transformation of local space functions of buildings belongs to the redistribution object of this system. This institutional inertia makes the current studies pay little attention to the distribution of benefits through redemption or compensation of development rights when the function of local space changes. This system is an important part of a country’s welfare system. However, the appreciation of real estate is affected by many factors, including the appreciation brought by the change of development rights, inflation, improvement of traffic conditions, and even a new private school. The question is, what should we do when we do not want to “ rob the rich to feed the poor”, but only want the property owner to hand over some of the proceeds obtained from the new rights granted by the public sector? Additionally, how much compensation should be given to the property owner when the public sector imposes more restrictions on the use of space functions? Therefore, our study provides a meaningful way to solve the above problems.

How to quantify the value of right change accurately is the premise of land policy formulation in various countries. Every country has a relative perfect official land pricing system. Land transactions between private entities rarely follow the official pricing standards of the location, but most are completed by market-oriented self-pricing and negotiation. We are concerned about how the right value changes when the restrictions imposed on land by urban planning allow the function of some spaces on the land to change for urban regeneration. The corresponding feasible measurement methods do not exist in Western countries and China. At least, they do not exist in the official pricing method. The main difference between official pricing and market pricing lies in whether the value of rights is evaluated or the value of real estate. The latter includes architectural aesthetics, appreciation potential and other factors. The influencing factors of current official pricing include functional constraints, development capacity and a series of regional conditions. These location conditions include the distance to the city center and various public service facilities. However, these factors all focus on the relative position of land on the two-dimensional plane of the city. Moreover, relevant studies all over the world are still strengthening this trend. Therefore, the perspective of measuring the development rights of local buildings based on spatial characteristics and the corresponding specific methods proposed in this study are universal. In countries and cities that have adopted land-use control systems and are in the process of or planning to renew local functions of buildings, our results can help them to further develop their own land policies and reduce the institutional costs caused by the lack of measurement technology. They can accurately calculate the change of property value caused by the change of local space function in the building. In addition, based on the welfare policy, they can choose whether or to what extent to allocate the value-added part.

6. Conclusions

In our study, the relationship between condominium ownership and land use right in China’s current property rights system is analyzed thoroughly. At the same time, this study argues that the trend of contemporary urban planning management in Western countries has transferred from the restriction of land development rights to the restriction of space development rights. These further illustrate the common demand for the measurement and redistribution of the change value of space development rights under different institutional backgrounds. We contribute to the current literature from two aspects. Firstly, the study reveals the influence of the unified right of ownership, use rights and development rights in the property system on the urban local spatial regeneration. In particular, during the change from two-dimensional plane to three-dimensional spaces, economic issues caused by the current property management are also identified in the study. Secondly, we further illustrate the necessity to update urban land economics toward urban spatial economics. Previous studies on land economic value focus on factors in the two-dimensional land, such as traffic, infrastructure and distance to public service facilities. However, our study can explain the laws of land economics in the three-dimensional spaces and guide the land resources management and exchange.

We find that, as a subdivision of condominium ownership, the condominium land-use right is hard to be identified. This has led to an institutional dilemma that restricts the transfer of functional development rights of local spaces. In addition, the valuation of local spaces development rights transfer, as the technical basis of the property rights system, may significantly influence the basic logic of land economics in urban regeneration, including the institutional choice of Western countries and China in the distribution of land-value-added income. With the residual method and market comparative method as the core, the study puts forward a primary system for estimating the value change of development rights. In addition, we also discuss detailly land leasing payment and compensation for local functional regeneration projects. The HPM is employed to measure the values of spatial characteristics in different urban functional spaces, which provides a new perspective for dealing with different pricing of the same place in real estate valuation.

The study also provides a practical way to deal with the property dilemma of building functional transfer. On the basis of the building ownership, it allows the transfer of condominium land use rights attached to ownership. In regeneration practice, after the redemption and compensation of development rights, the governments and property owners can achieve the compensated transfer of the functional property right by re-confirming the right and issuing the property right certificate according to regulations of urban planning. This method will reduce the property rights consolidation, land rights transfer, and large-scale demolition and construction with plots as its smallest unit. In addition, the valuation method of the development right proposed by the study not only improves the accuracy by shortening the time and scope of market comparison, but also realizes the valuation of local spaces. The blocked land financial and economic cycle in China’s urban regeneration can only be solved when the property rights system and economic valuation technology are interdependent. In the context of the sharp decrease of newly sold land, the public and private sectors can share the value brought by the exchange of urban spatial functions transfer. However, although the HPM reflects the value of spatial characteristics, the formula produced by the researchers is only used to illustrate the characteristics and operability of this method due to the limitations of data collection and the uncertainty of data fitting conditions in the modelling process. Our limitations mainly lie in the following: (1) It is difficult to be absolutely comprehensive in the selection of spatial characteristic variables. For example, it is difficult to obtain information such as indoor floor height and distance from surrounding buildings through network big data. We still need to use other methods to efficiently obtain the values of these variables with greater potential impact. (2) This method belongs to the market comparison method and relies on more market transaction data. Therefore, it does not apply to areas where the real estate market has shrunk. (3) In the use of this method in real scenarios, it is still necessary for the measurer to delimit the comparison area based on the local characteristics to ensure the relative equality of public services, transportation and other conditions in the area as far as possible. At the same time, we still need to judge the cycle of selecting comparative cases to avoid the impact of the external environment, such as real-estate policy and financial credit policy. Therefore, the valuation formula for a specific city or at the national level requires more research on diverse data sources and stable models in the future.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.Z. and X.G.; methodology, H.Z.; software, Y.L.; formal analysis, H.Z.; investigation, X.G.; resources, Y.L.; data curation, Y.H.; writing—original draft preparation, H.Z. and X.G.; writing—review and editing, Y.L. and Y.H.; visualization, Y.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China, Grant/Award Number: 52108035; Science and Technology Plan Project of Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development of China, Grant/Award Number: 2022-K-014; National Natural Science Foundation of China, Grant/Award Number: 51908232l; Pyramid Project of Beijing University of Civil Engineering and Architecture, Grant/Award Number: JDYC20220803.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available to protect the privacy of the study’s participants.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Note

| 1 | Market entities refer to the natural person, enterprise entities, and other economic organizations registered by the registration authority according to law and engaged in business activities for profit. |

References

- General Office of the CPC Central Committee and General Office of the State Council. Proposal of the CPC Central Committee on Formulating the Fourteenth Five-Year Plan for National Economic and Social Development and the Vision for 2035. 2020. Available online: http://www.gov.cn/zhengce/2020-11/03/content_5556991.htm (accessed on 1 August 2022).

- Wang, M.H. Implement Urban Regeneration Actions. 2020. Available online: http://www.gov.cn/xinwen/2020-12/29/content_5574417.htm (accessed on 3 August 2022).

- Harvey, D. The right to the city. City Read. 2008, 6, 23–40. [Google Scholar]

- Harvey, D. Spaces of Global Capitalism; Verso: London, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, G.Z. On the innovation in the system of dispositing the local power of land in China. Acad. Res. 2011, 9, 46–50. [Google Scholar]

- McConnell, V.; Walls, M.; Kopits, E. Zoning, TDRs and the Density of Development. J. Urban Econ. 2006, 59, 440–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coase, R.H. The Problem of Social Cost. J. Law Econ. 1960, 3, 1–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.; Xu, C.Y. Land development rights, space control, and synergetic planning. City Plan. Rev. 2014, 34, 26–34. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, H.; Lin, Y.; Yan, B. Space development right study under the background of urban regeneration. Urban Dev. Stud. 2022, 3, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, D.; Ren, C.R.; Zhou, T. Understanding the impact of land finance on industrial structure change in China: Insights from a spatial econometric analysis. Land Use Policy 2021, 103, 105323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Ye, F. The political economy of land finance in China. Public Budg. Financ. 2016, 36, 91–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, C. Land policy reform in China: Assessment and prospects. Land Use Policy 2003, 20, 109–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.Y.; Xiong, X.F.; Zhang, Y.H.; Guo, G.C. Land system and China’s Development Mode. China Ind. Econ. 2022, 1, 34–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.J. Urbanization 2.0 and Transition of Planning: Explanation Based on a Two-Phase Model. City Plan. Rev. 2017, 3, 84–93+116. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Y.J.; Song, T. An analysis on the financial balance of urban renewal: Patterns and practice. City Plan. Rev. 2021, 45, 53–61. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, Y. Analysis on the key fields and strategies of the institutional innovation of urban regeneration in China. Urban Plan. Int. 2022, 37, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Liu, Y.F.Q.; Deng, C.W. Characteristics of the ongoing urban regeneration in China. Hum. Settl. 2021, 3, 43–48. [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence, W.C.L.; Kwong, W.C.; Edward, C.Y.Y.; Kelvin, S.K.W.; Wah, S.W.; Pearl, Y.L.C. Measuring and interpreting the effects of a public-sector-led urban renewal project on housing pricesöan empirical study of a comprehensive development area zone developed upon ‘taking’ in Hong Kong. Environ. Plan. B Plan. Des. 2007, 34, 524–538. [Google Scholar]

- Linkous, E.R. Transer of development rights and urban land markets. Environ. Plan. A Econ. Space 2017, 49, 1122–1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujita, M.; Paul, R.K.; Venables, A. The Spatial Economy: Cities, Regions, and International Trade; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, Y.; Yang, D.; Zhu, H. The Innovation of Urban Regeneration Institutions in China: Experience from Guangzhou, Shenzhen and Shanghai; Tsinghua University Press: Beijing, China, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, J.Q.; Zhu, Y.X.; Zhang, Q. Urban regeneration toward the improvement of spatial quality. Time + Archit. 2021, 4, 12–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wakeford, R. American Development Control: Parallels and Paradoxes from an English Perspective; HMSO: London, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Cullingworth, B.; Nadin, V. Town and Country Planning in the UK; Routledge: London, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplowitz, M.D.; Machemer, P.; Pruetz, R. Planners’ experiences in managing growth using transferable development rights (TDR) in the United States. Land Use Policy 2008, 25, 378–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pruetz, R.; Pruetz, E. Transfer of development rights turns 40. Plan. Environ. Law 2007, 59, 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sang, J. The Feature of the Land Development Right and the Institutional Plight of Urban Planning in Transitional China. Mod. Urban Res. 2013, 28, 38–43+89. [Google Scholar]