Abstract

The assessment of cultural ecosystem services (CES) has proved challenging due to their intangible, non-material and invisible characteristics. A number of methods for evaluating CES have been developed, which depend mostly on subjective perceptions and behavior. An objective direction for considering CES is proposed based on the assumption that making use of CES leaves visible manifestations in the physical landscape and human society. The approach developed in this paper attempts to follow this direction by identifying a large amount of manifestations that reflect a wider range of CES types. This approach is applied to a case study of the Weser River in Germany, showing that the local people along the river have benefited from multiple CES of the Weser and created various manifestations of those CES. In the future researches, the identification and documentation of manifestations can be used to map the delivery of CES, to develop indicator systems for CES, to assess heritage value and identity, to indicate spatially explicit preferences on ecosystem characteristics and visual aesthetic qualities, to estimate the economic value of educational and inspirational service, to investigate sense of place, as well as to make better informed landscape management and nature protection.

1. Introduction

Cultural ecosystem services (CES) are defined as the non-material benefits people obtain from ecosystems through spiritual enrichment, cognitive development, reflection, recreation, and aesthetic experience [1]. Like all other ecosystem services, CES must demonstrate a certain relationship between ecosystems in the biophysical domain and human needs in the social domain, although some CES may have little dependence on ecosystems (Daniel et al., 2012). As ecosystems cannot deliver benefits to people by themselves without incorporating social inputs like human capital and built capital, CES may depend on human and built capital to a greater degree [2].

Although studies on CES are still confronted with intangible, non-material and invisible challenges, a number of evaluation methods that employ different procedures, start from different theoretical backgrounds and apply different techniques are identified [3]. These methods are divided into two main categories, monetary methods and non-monetary methods. The monetary methods category involves revealed preference, including market price method [4], travel cost method [5], and hedonic pricing method [6], and stated preference, including deliberative valuation method [7], contingent valuation method [8], and choice experiment method [9]. The non-monetary methods category can also be classified into revealed preference, including observation method [10], document method [11], social media-based method [12], and stated preference, including interview method [13], questionnaire method [14], narrative method [15], focus group method [16], expert based method [17], Q-method [18], participatory mapping method [19], participatory GIS method [20], and public participation GIS method [21]. To a large extent, these methods depend generally on subjective perceptions, behavior or responses of participants such as tourists, stakeholders, aboriginal peoples, local residents or experts.

Human cultures are always influenced and shaped by natural landscapes, while humans always influence and shape their surrounding environment to enhance the availability of these services [22]. Indigenous peoples and local communities play an essential role in this reciprocal process, not only by maintaining, enhancing and managing ecosystems [23,24] and effectively conserving biodiversity [25] based on their knowledges, skills and capabilities [26], by incorporating their livelihood, well-being and value perceptions into policy-making [27] and building connections with ecosystems [28], but also by generating cultural landscapes and delivering CES [29,30].

This reciprocal relationship leads to the assumption that making use of CES leaves discernible marks in the physical landscape and human society [31]. Based on this assumption, an objective method has been developed by a series of studies. Bieling and Plieninger proposed an approach for analyzing correlations between visible manifestations of CES in a field walk-based landscape and ecosystem service bundles [31]. Coscieme focused on popular music that reflects the inspirational service of multiple ecosystems and estimated the inspirational value [32]. Figueroa-Alfaro and Tang used geo-tagged photographs from social media to identify aesthetic value in non-monetary terms [33]. Hutcheson et al. considered educational programs as the educational service provided by the Hudson River and estimated the economic value of this educational service based on the travel cost method [34]. Hiron et al. considered poetry as the results of the inspirational service provided by bird species [35]. Katayama and Baba showed that Japanese children’s songs reflect the inspirational service and measured the inspirational value [36]. Additionally, Jiang and Marggraf suggested that the inspirational service is also reflected by published books [37].

The valuable services provided by river ecosystems such as wildlife habitat, electric power and transportation have been recognized since the 1990s [38]. The constant flow of rivers is often associated with the irreversible passing of time or the conformity of society [32]. Hence, in this paper, we focus on river ecosystems and attempt to identify more manifestations in the physical landscape or human society that reflect a wider range of CES provided by rivers. For this purpose, we develop an approach, termed as making intangibles tangible, for identifying different kinds of manifestations that reflect multiple CES. We then apply this approach to a case study of the Weser River in Germany, showing the manifestations of CES provided by the river.

2. Methods and Materials

2.1. Approach

The approach we develop consists of three steps: First, choose a spatially clearly defined ecosystem and present the history of interactions between local people and this ecosystem. The assumption behind is that the longer people interact with their surrounding ecosystems, the more manifestations that reflect CES can be found.

Second, identify potential manifestations of each CES category relevant to the ecosystem. Based on the Common International Classification of Ecosystem Services (CICES) [39], three groups of CES with eight classes are taken into account. The scientific and educational classes are merged due to their close relatedness. The description of the aesthetic class, artistic representations of nature, is associated with the inspirational service, thus we use the term inspirational instead of aesthetic to avoid the confusion with the terms used in Millennium Ecosystem Assessment (MA). Furthermore, in order to keep consistent, we insist on using the noun forms of terms for all classes such as science and education, inspiration, symbol, sacredness and religiousness (Table 1).

Table 1.

The classification of CES (modified from CICES V5.1).

Third, search for concrete manifestations of each CES class. We adopt the so-called snowball strategy, that is, a small number of fundamental studies will lead to a large number of relevant studies according to their references and citations [37]. For our case study, based on two publications, “Die Weser: vom Thüringer Wald bis zur Nordsee” [40] and “Die Weser: 1800–2000” [41], more information about the Weser has been found, which includes field studies, digital maps, remote sensing data, publications from multiple disciplines, and gray literature from internet.

2.2. Study Area

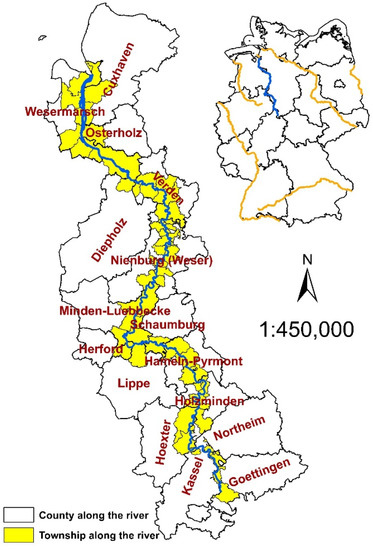

The Weser River is the only large river that lies entirely within German national territory. It forms at Hannoversch Münden by the confluence of the rivers Werra and Fulda, flows in the northern direction through the Central Upland Ranges and the North German Plain, and empties into the North Sea, having an overall length of 453 km. Currently, there are around 1.5 million residents living directly along the Weser River, distributing in 66 municipalities in 16 districts of four federal states (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The geographical location of the Weser River in Germany.

3. Case Study

3.1. A Brief History about Human Activities around the Weser

The history of human activities along the Weser can be dated back to the first four centuries, which is confirmed by the findings in the riverbed or on the banks. The Weser region began substantial development since Charlemagne conquered this region, when a number of important settlements, such as Münden, Hameln, Höxter, Minden, Nienburg and Bremen, arose by reason of military or ecclesial relevance. This river was given the name Weser in the eighth century [42,43].

In the long historical period, the Weser has been deemed an important lifeline. It provides not only food (fish), but also drinking and processing water to local people. Meanwhile, the river is the only transportation route. For the sake of better navigability, local people has begun early to reconstruct and improve the waterway by means of hydro-engineering interventions. The river has also served as wastewater disposal. The water quality of the Weser deteriorates with the increasing industrialization and population growth and has been gradually improved through the construction and expansion of municipal and industrial wastewater treatment plants and the reduction of salt discharges from the potash industry in the last decades. Furthermore, the river plays an outstanding role for recreational activities due to its diversified and attractive landscape. On the dark side, the terrifying and destructive effects of floods also accompany the history of local people along the Weser [42,43]. All of these facts indicate that the interactions between local people and the river are very intensive, implying that there exist plentiful manifestations that reflect the CES provided by the river to local people.

3.2. Identifying Potential Manifestations

Based on the CES classification described in Table 1, we identify the potential manifestations relevant to river ecosystems for each CES class (Table 2). Considering the difficulty in relating intangible services to ecosystem elements or functions [44], we interpret the relationships between ecosystem features and the respective manifestations.

Table 2.

Potential manifestations relevant to river ecosystems for each CES class.

3.2.1. Physical and Experiential Use

Ecosystems are often attractive places where people can engage in some form of nature-based recreational and experiential activities, which in turn provide an opportunity for people to obtain directly the benefits of ecosystem services. Physical activities in, on or along a river include swimming, boating, biking, and camping, while the major in situ experiential activity related to a river is scenery viewing. Since these activities depend usually on built infrastructure and accessibility, the constructive objects like swimming areas, landing stages, cycle routes, camping sites and viewing points are chosen as the manifestations of both classes. The close relationship between ecosystems and infrastructures for physical or experiential use consists in that the degradation or improvement of ecosystem quality would lead to corresponding negative or positive changes in visitor number to and use frequency of these infrastructures.

3.2.2. Science and Education

Generally speaking, ecosystems exist longer than humankind. In the long period of time, ecosystems have recorded the evolutionary traces of the earth and witnessed the human history. Hence, people can learn the knowledge about their natural environment and obtain the information about their own history from them, which can be seen as the scientific and educational service of ecosystems. Permanent objects, rather than temporary research programs or guided tours devoted to river ecosystems are taken into account. Since the primary purpose of modern museums is to collect, conserve, research, exhibit, and interpret objects of art, natural history, science, technology, or human history [45], they are appropriate manifestations for scientific and educational services. Despite the lag of time, any significant change in ecosystem features would be collected and recorded in museums.

3.2.3. Cultural Heritage

Cultural heritage is conceptualized as memories associated with specific ecosystem features from past cultural connections that remind people of their collective and individual roots [46], implying the inextricable long-term interactions between human influences and ecosystem features. Following the definition by United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization, cultural heritage are monuments, groups of buildings and sites that are built up by past generations, maintained in the present, and bestowed on future generations [47]. Rivers in the pre-modern times were generally deemed geographical barriers to be crossed, the most effective natural transportation ways before trains, automobiles and airplanes are invented, and potential risks for nearby settlements owing to floods. The interactions between rivers and people living around them are accordingly represented by connecting both banks of rivers (bridges, tunnels, and ferries), by improving and modifying waterways for navigation (canals and harbors), and by altering water flows for flood prevention (barrages and dikes). The stone bridge on the Danube in the old town of Regensburg is an example of world cultural heritage. We must keep in mind that heritages are not only inherited from the past but also face the future. Managed or even heavily altered ecosystems can acquire cultural significance over time [48]. Rivers were and are still deemed barriers, transportation ways, and risks, those infrastructures reflect the very interactions how people and rivers coexist for a long time. If bridges or dikes were no more necessary in the future, they would become heritages that reflect our culture at the present.

3.2.4. Entertainment and Inspiration

Ecosystems inspire an almost unlimited array of representations in art, writings, etc., which consciously or subconsciously remind us of our ties with nature and shape our views and appreciation of the represented ecosystems. MA distinguishes five categories of inspirational service: verbal arts (legends, poems, fictions, etc.), performing arts (music, songs, dance, etc.), fine arts (paintings, sculptures, crafts, etc.), designs and fashion (home furnishings, clothing, etc.), and media (radios, televisions, films, advertisings, websites, etc.) [22]. CICES identifies the class of inspiration as artistic representations of nature, and an additional class of entertainment as ex situ viewing of nature through social media, in contrast to in situ experience and activities [39]. Both classes are derived from the same service type in MA, but the most important difference between them is that entertainment refers to ex situ experience of nature, while inspiration refers to mental stimulation and creative work based on in situ experience of nature. Since entertainment can also be provided by artistic representations of nature, the distinction between them should be made that only materials produced and shared by the general public like travel notes, short video, or photographs are considered as manifestations for entertainment, while materials created by professionals or artists like poems, songs, paintings or films are deemed manifestations for inspiration. Worldwide reputable examples about rivers include “The Blue Danube” by Johann Strauss II and “And Quiet Flows the Don” by Mikhail Sholokhov. Although entertainment relates to ecosystems only in a very indirect way, while inspiration depends strongly on ecosystem features, changes in ecosystems would affect both of them. For instance, viewing a river with clean blue water, either in situ or ex situ, is much more inspiring and entertaining than viewing one with dirty polluted water.

3.2.5. Symbol

The relationship between ecosystem features and the symbolic service is straightforward. Since municipal coats of arms often have representative symbols of plants, animals or ecosystems, e.g., the common rue of Saxony, the bear of Berlin, or the Rhine of North Rhine-Westphalia, they are appropriate manifestations of this service.

3.2.6. Sacredness and Religiousness

People often search for spiritual connections to their environment through personal reflections, organized rituals or traditional taboos, while ecosystems or species provide an important medium for this orientation in time and space [22]. Reasonably, the whole river, a certain part of the river, or certain species living in the river can serve as the manifestations of holy places or sacred plants and animals.

3.3. Searching for Concrete Manifestations

3.3.1. Physical Use

A variety of recreational activities are available in, on or along the Weser. Twelve swimming areas are located in the downstream of the river due to wider surface and better water quality, 126 loading stages for boating and cruise are found in almost every village, town and city, 48 camping sites are often combined with other possibilities like fishing and boating, and the Weser Cycle Route from Hannoversch Münden to Bremerhaven with the length of 515 km belongs to the most attractive cycle routes in Germany [49].

3.3.2. Experiential Use

Viewing points can be part of a building (e.g., a tower) or be built in the natural topography (e.g., on a hilltop). A total of 74 viewing points are found along the Weser. Typical forms in the upstream are constructions on the hills, such as the Monument of Weser Song in Hannoversch Münden, the Skywalk of Hannoversche Cliff in Bad Karlshafen, and the Monument of Kaiser Wilhelm in Porta Westfalica, while typical examples in the downstream are the observation tower in Lemwerder, the lighthouse and the water tower in Bremen [50].

3.3.3. Science and Education

There are two museums relevant to the Weser River. One is the Weser Renaissance Museum at Brake Castle. This museum collects the materials and delivers the knowledge about the Weser Renaissance, which is a form of architectural style that is found in the area around the Weser in the period between the Reformation and the Thirty Years War. The Weser played a significant role for idea communication and information exchange through traveling of merchants, artists, and scholars [51]. The other is the German Fairy-tales and Weser Legends Museum located in Bad Oeynhausen, which illustrates the history of collection and writing of fairy-tales and legends about the Weser.

3.3.4. Cultural Heritage

There are totally 55 bridges, 23 ferries and one tunnel across the Weser. The bridges over the Weser cover almost all structure types, such as beam bridge, arch bridge, and suspension bridge, and they are used to carry pedestrians, trains or road traffic. The ferries on the Weser that are privately managed serve as the supplement to bridges. The only tunnel across the Weser was constructed from 1998 to 2004 for offering a connection between Nordenham and Bremerhaven. A total of 35 harbors are distributed in the cities and towns along the Weser, among which the most important and largest ones are located in Bremen and Bremerhaven. The middle course of the Weser is regulated by seven barrages built in the 20th century. Accordingly, seven canals that shorten the shipping distance were constructed for the purpose of navigation. Furthermore, 353 km dikes are built for flood prevention in the lower course of the Weser.

3.3.5. Entertainment

Since a huge amount of geo-tagged photographs relevant to the Weser is found on Google Maps, three photos in high quality are chosen from three typical viewing points along the Weser, the Monument of Weser Song in Hannoversch Münden, the Skywalk of Hannoversche Cliff in Bad Karlshafen, and the Monument of Kaiser Wilhelm in Porta Westfalica (Table 3). These photos show a part of the Weser and indirectly share the beauty of this river.

Table 3.

The entertainment service represented by selected photographs about the Weser (based on Google Maps).

3.3.6. Inspiration

The Weser is generally not the leading character, but often plays a non-negligible role in the German folklores [52] (Table 4). Clearly, the images of the floating ice sheets or the drifting shell are closely associated with the river, implying that they cannot be imagined in a story if the river would not exist. The story about the Westphalian Gorge is related to the geomorphological features, which indicates an impressive description of a possible event in the natural history of the river [42]. The folklore about the dike in Bremen gives us a wonderful example of the interaction between people and flood.

Table 4.

The inspiration service represented by folklores about the Weser (translated from [52]).

A number of literary works in different genres such as poems, proses and novels are created by many writers (Table 5). The poem on the Weser Stone in Hannoversch Münden was written by Carl Natemann who emphasized the formation of the river through the convergence (“kiss”) of two rivers Werra and Fulda [40]. The prose written by von Dingelstedt describes his view of mountains, villages and water when traveling on a boat [53]. Additionally, Raabe meticulously delineated a garden near the river and the stars reflected in the Weser that was like a mirror [54].

Table 5.

The inspiration service represented by literature works about the Weser.

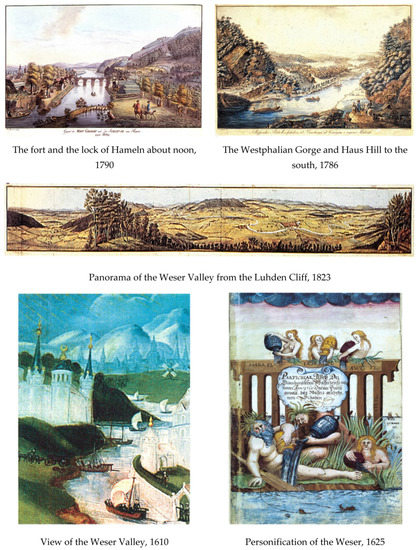

The Weser also inspires the creative desire of painters (Figure 2). Wilhelm Strack faithfully and vividly represented the central role of the Weser in the city of Hameln, the scene of the landscape at the Westphalian Gorge, and the panorama of the Weser Valley [55], while the view of the Weser Valley [56] and the personification of the Weser [57] are beautiful imagination of the river.

Figure 2.

The inspiration service represented by paintings about the Weser.

Besides, there are two songs related to the Weser, one is “The Weser song”, the other is “Where the Weser makes a big bow” (also known as “The Weser Bow song”), and a TV program “The Weser” produced by Northern German Broadcasting. These videos can be found on YouTube.

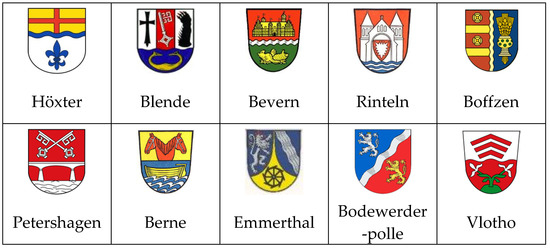

3.3.7. Symbol

The municipal coats of arms of all 16 districts, eight collective municipalities and 66 municipalities along the Weser are examined. We illustrate some coats of arms that symbolize the Weser in Figure 3. According to the official interpretations, all of the wavy shapes stand for the Weser [58,59], regardless of their locations (middle or bottom), orientations (horizontal, vertical or diagonal), colors (golden, silver, blue or red), or different patterns. A simple statistic shows that four districts (25%), five collective municipalities (63%) and 28 municipalities (42%) have symbols of the Weser on their coats of arms. Since the acceptance or change of coats of arms is decided by local communities and special importance is placed consciously on home awareness in the design of coats of arms [60], they actually reflect the sense of place provided by the Weser River.

Figure 3.

The symbol service represented by municipal coats of arms.

3.3.8. Sacredness and Religiousness

In comparison with the religious significance of the river Ganga to Hindus, the Tano River to Asante, the Nile perch to the ancient Egyptians, or the Amazonian dolphin to the most native tribes [61], no evidences are found to indicate that the Weser and the species living in it have any sacred or religious meaning to the local Germans.

4. Discussion

4.1. Limitations and Advantages of This Approach

Due to the data availability and the overwhelming amount of data sources, the inventory of manifestations that reflect CES of the Weser is far from being exhaustive in two senses. First, a large number of photographs on Google Maps, more paintings [53,62], and potential literature works that we did not find are not involved. Second, many relevant manifestations in association with CES are not considered, such as leisure fishing as a recreational activity, research papers, monographs and textbooks for the scientific and educational service, and logos of companies, institutes and other organizations for the symbolic service. This fact implies that the application of this approach at a larger scale (e.g., at national or global scale) is challenging, if not impossible.

On the other hand, the advantages are also obvious. First, this approach can be easily applied to other ecosystem types such as forests, grasslands, lakes, etc., by choosing an appropriate set of potential manifestations. Second, since measurement or valuation of CES often suffers from the issue of overlap and interconnectedness [63], using clearly defined manifestations contributes to avoiding double-counting. We take an extreme example to explain this: A documentary film director was inspired by the beauty and historical heritages when she was hunting in a forest. She took a lot of photos of the forest and produced a film later in order to share her experience, provide entertainment, and convey some knowledge about the forest to her audience. The question is which service the forest delivered to the director and the audience. By focusing on the output (film), we identify the inspirational service of the forest to the director, while the physical use service (hunting), the experiential use service (beauty), cultural heritage and educational service of this forest should be reflected by other manifestations. The photos taken by the director represent the entertainment service of the forest to her audience.

4.2. Implications for Future Research

First of all, the identification of manifestations plays an important role in mapping the delivery of CES [64] and developing indicator systems for CES [65]. Furthermore, documenting manifestations can be used for further analysis of CES. For example, manifestations of cultural heritage is useful for the assessment of heritage value and identity [66,67]; photographs indicate spatially explicit preferences and priorities on ecosystem characteristics [68] and visual aesthetic qualities and attractiveness [69]; educational programs are used to estimate the economic value of educational service [34]; music [32], songs [36], poetry [35] and published books [37] reveal the value of inspirational service; coats of arms are potential for investigating sense of place, which has been investigated through the lens of language [70]. Last but not least, manifestations of CES enable better informed landscape management and planning [71] and nature protection [72].

5. Conclusions

The frequently used methods for the assessment of CES depend significantly on the subjective perceptions, actions and responses of participants. Another objective direction for considering CES is developed based on the assumption that making use of CES leaves visible manifestations in the physical landscape and human society. The approach developed in this paper contributes to the objective direction by illustrating a large amount of manifestations that reflect a wider range of CES types. This approach is applied to a case study of the Weser River in Germany, showing that the local people along the river have benefited from multiple CES of the Weser and created various manifestations of those CES. This approach can be easily applied to other specific ecosystems over the world. In the future researches, the identification and documentation of manifestations can be used to map the delivery of CES, to develop indicator systems for CES, to assess heritage value and identity, to indicate spatially explicit preferences on ecosystem characteristics and visual aesthetic qualities, to estimate the economic value of educational and inspirational service, to investigate sense of place, as well as to make better informed landscape management and nature protection.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, W.J.; methodology, W.J.; data curation, W.J.; writing—original draft preparation, W.J.; writing—review and editing, W.J.; supervision, R.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was funded by National Key Research and Development Program of China (No. 2017YFA0604701).

Acknowledgments

We would like to appreciate the supporting efforts made by Jiamei Xiao.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- TEEB. Mainstreaming the Economics of Nature: A Synthesis of the Approach, Conclusions and Recommendations of TEEB. 2010. Available online: http://teebweb.org/publications/teeb-for/synthesis/ (accessed on 15 December 2021).

- Costanza, R.; De Groot, R.; Braat, L.; Kubiszewski, I.; Fioramonti, L.; Sutton, P.; Farber, S.; Grasso, M. Twenty years of ecosystem services: How far have we come and how far do we still need to go? Ecosyst. Serv. 2017, 28, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, X.; Van Damme, S.; Li, L.; Uyttenhove, P. Evaluation of cultural ecosystem services: A review of methods. Ecosyst. Serv. 2019, 37, 100925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumarga, E.; Hein, L.; Edens, B.; Suwarno, A. Mapping monetary values of ecosystem services in support of developing ecosystem accounts. Ecosyst. Serv. 2015, 12, 71–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Berkel, D.B.; Verburg, P.H. Spatial quantification and valuation of cultural ecosystem services in an agricultural landscape. Ecol. Indic. 2014, 37, 163–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, X.; Corominas, L.; Pargament, D.; Acuña, V. Is river rehabilitation economically viable in water-scarce basins? Environ. Sci. Policy 2016, 61, 154–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenter, J.O. Integrating deliberative monetary valuation, systems modelling and participatory mapping to assess shared values of ecosystem services. Ecosyst. Serv. 2016, 21, 291–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gandarillas, R.V.; Jiang, Y.; Irvine, K. Assessing the services of high mountain wetlands in tropical Andes: A case study of Caripe wetlands at Bolivian Altiplano. Ecosyst. Serv. 2016, 19, 51–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ungaro, F.; Häfner, K.; Zasada, I.; Piorr, A. Mapping cultural ecosystem services: Connecting visual landscape quality to cost estimations for enhanced services provision. Land Use Policy 2016, 54, 399–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unnikrishnan, H.; Nagendra, H. Privatizing the commons: Impact on ecosystem services in Bangalore’s lakes. Urban Ecosyst. 2015, 18, 613–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Everard, M.; Jones, L.; Watts, B. Have we neglected the societal importance of sand dunes? An ecosystem services perspective. Aquat. Conserv. Mar. Freshw. Ecosyst. 2010, 20, 476–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willemen, L.; Cottam, A.J.; Drakou, E.; Burgess, N.D. Using Social Media to Measure the Contribution of Red List Species to the Nature-Based Tourism Potential of African Protected Areas. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0129785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmidt, K.; Walz, A.; Jones, I.; Metzger, M.J. The Sociocultural Value of Upland Regions in the Vicinity of Cities in Comparison With Urban Green Spaces. Mt. Res. Dev. 2016, 36, 465–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryce, R.; Irvine, K.N.; Church, A.; Fish, R.; Ranger, S.; Kenter, J.O. Subjective well-being indicators for large-scale assessment of cultural ecosystem services. Ecosyst. Serv. 2016, 21, 258–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bieling, C. Cultural ecosystem services as revealed through short stories from residents of the Swabian Alb (Germany). Ecosyst. Serv. 2014, 8, 207–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ondiek, R.A.; Kitaka, N.; Oduor, S.O. Assessment of provisioning and cultural ecosystem services in natural wetlands and rice fields in Kano floodplain, Kenya. Ecosyst. Serv. 2016, 21, 166–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nahuelhual, L.; Carmona, A.; Lozada, P.; Jaramillo, A.; Aguayo, M. Mapping recreation and ecotourism as a cultural ecosystem service: An application at the local level in Southern Chile. Appl. Geogr. 2013, 40, 71–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacDonald, P.A.; Murray, G.; Patterson, M. Considering social values in the seafood sector using the Q-method. Mar. Policy 2015, 52, 68–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, G.; Raymond, C. The relationship between place attachment and landscape values: Toward mapping place attachment. Appl. Geogr. 2007, 27, 89–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darvill, R.; Lindo, Z. Quantifying and mapping ecosystem service use across stakeholder groups: Implications for conservation with priorities for cultural values. Ecosyst. Serv. 2015, 13, 153–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, G.; Hausner, V.H. An empirical analysis of cultural ecosystem values in coastal landscapes. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2017, 142, 49–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, R.; Scholes, R.; Ash, N. Ecosystems and Human Well-Being: Current State and Trends; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Comberti, C.; Thornton, T.F.; Wyllie de Echeverria, V.; Patterson, T. Ecosystem services or services to ecosystems? Valuing cultivation and reciprocal relationships between humans and ecosystems. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2015, 34, 247–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sangha, K.K.; Evans, J.; Edwards, A.; Russell-Smith, J.; Fisher, R.; Yates, C.; Costanza, R. Assessing the value of ecosystem services delivered by prescribed fire management in Australian tropical savannas. Ecosyst. Serv. 2021, 51, 101343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawson, N.M.; Coolsaet, B.; Sterling, E.J.; Loveridge, R.; Gross-Camp, N.D.; Wongbusarakum, S.; Sangha, K.K.; Scherl, L.M.; Phan, H.P.; Zafra-Calvo, N.; et al. The role of Indigenous peoples and local communities in effective and equitable conservation. Ecol. Soc. 2021, 26, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sangha, K.K.; Preece, L.; Villarreal-Rosas, J.; Kegamba, J.J.; Paudyal, K.; Warmenhoven, T.; RamaKrishnan, P.S. An ecosystem services framework to evaluate indigenous and local peoples’ connections with nature. Ecosyst. Serv. 2018, 31, 111–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sangha, K.K.; Russell-Smith, J.; Costanza, R. Mainstreaming indigenous and local communities’ connections with nature for policy decision-making. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2019, 19, e00668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoeckl, N.; Jarvis, D.; Larson, S.; Larson, A.; Grainger, D.; Corporation, E.A. Australian Indigenous insights into ecosystem services: Beyond services towards connectedness—People, place and time. Ecosyst. Serv. 2021, 50, 101341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plieninger, T.; van der Horst, D.; Schleyer, C.; Bieling, C. Sustaining ecosystem services in cultural landscapes. Ecol. Soc. 2014, 19, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinheiro, R.O.; Triest, L.; Lopes, P.F.M. Cultural ecosystem services: Linking landscape and social attributes to ecotourism in protected areas. Ecosyst. Serv. 2021, 50, 101340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bieling, C.; Plieninger, T. Recording Manifestations of Cultural Ecosystem Services in the Landscape. Landsc. Res. 2013, 38, 649–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coscieme, L. Cultural ecosystem services: The inspirational value of ecosystems in popular music. Ecosyst. Serv. 2015, 16, 121–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueroa-Alfaro, R.W.; Tang, Z. Evaluating the aesthetic value of cultural ecosystem services by mapping geo-tagged photographs from social media data on Panoramio and Flickr. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2017, 60, 266–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutcheson, W.; Hoagland, P.; Jin, D. Valuing environmental education as a cultural ecosystem service at Hudson River Park. Ecosyst. Serv. 2018, 31, 387–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiron, M.; Pärt, T.; Siriwardena, G.M.; Whittingham, M.J. Species contributions to single biodiversity values under-estimate whole community contribution to a wider range of values to society. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 7004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katayama, N.; Baba, Y.G. Measuring artistic inspiration drawn from ecosystems and biodiversity: A case study of old children’s songs in Japan. Ecosyst. Serv. 2020, 43, 101116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, W.; Marggraf, R. Ecosystems in Books: Evaluating the Inspirational Service of the Weser River in Germany. Land 2021, 10, 669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lansing, J.S.; Lansing, P.S.; Erazo, J.S. The Value of a River. J. Political Ecol. 1998, 5, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Haines-Young, R.; Potschin, M.B. Common International Classification of Ecosystem Services (CICES) V5.1 and Guidance on the Application of the Revised Structure. 2018. Available online: https://cices.eu/content/uploads/sites/8/2018/01/Guidance-V51-01012018.pdf (accessed on 15 August 2021).

- Below, M. Die Weser. Vom Thüringer Wald Bis Zur Nordsee; Temmen: Bremen, Germany, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Küster, B. Die Weser: 1800–2000; Donat: Bremen, Germany, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Löbe, K. Das Weserbuch. Roman Eines Flusses. 2. Aufl.; Niemeyer: Hameln, Germany, 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, H.-G.; Eckoldt, M.; Rohde, H. Die Weser. In Flüsse und Kanäle. Die Geschichte der Deutschen Wasserstrassen; Martin, E., Hans-Georg, B., Eds.; DSV-Verl.: Hamburg, Germany; Busse-Seewald: Herford, Germany, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Gee, K.; Burkhard, B. Cultural ecosystem services in the context of offshore wind farming: A case study from the west coast of Schleswig-Holstein. Ecol. Complex. 2010, 7, 349–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, E.P. Museums in Motion. An Introduction to the History and Functions of Museums; American Association for State and Local History: Nashville, TN, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Millennium Ecosystem Assessment. Ecosystems and Human Well-Being: Synthesis; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. Convention Concerning the Protection of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage. Adopted by the General Conference at Its Seventeenth Session Paris, 16 November 1972. Paris. 1972. Available online: http://whc.unesco.org/archive/convention-en.pdf (accessed on 15 August 2021).

- Daniel, T.C.; Muhar, A.; Arnberger, A.; Aznar, O.; Boyd, J.W.; Chan, K.M.A.; Costanza, R.; Elmqvist, T.; Flint, C.G.; Gobster, P.H.; et al. Contributions of cultural services to the ecosystem services agenda. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 8812–8819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allgemeiner Deutscher Fahrrad-Club. Bicycle Travel Analysis. 2016. Available online: https://www.adfc.de/fileadmin/user_upload/Expertenbereich/Touristik_und_Hotellerie/Radreiseanalyse/Downloads/ADFC_Bicycle_Travel_Analysis__2016__engl._short_version_.pdf (accessed on 15 December 2021).

- Bielefelder Verlag. Weser-Radweg: Vom Weserbergland Bis zur Nordsee. Radwanderkarte 1:75.000. 3. Aufl.; Bielefelder Verlag: Bielefeld, Germany, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Großmann, G.U. Renaissance im Weserraum; Dt. Kunstverl: München, Germany, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Paetow, K. Die Schönsten Wesersagen. 3., Durchges. und Erw. Aufl.; Sponholtz: Hameln, Germany, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- von Dingelstedt, F. Das Wesertal von Münden bis Minden. Reprograf. Nachdr. der Ausg. Kassel und Leipzig 1838; Olms: Hildesheim, Germany, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Raabe, W. Der heilige Born; Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht: Göttingen, Germany, 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Strack, A.W.; Albrecht, T. Malerische Reise Durch das Weserbergland: Anton Wilhelm Strack, Hofmaler und Professor für Zeichenkunst in Bückeburg (1758–1829); Verl. Createam: Bückeburg, Germany, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Kastler, J.; Lüpkes, V. (Eds.) Die Weser. EinFluss in Europa. Aufbruch in die Neuzeit; Mitzkat (Die Weser-Einfluss in Europa, Bd. 2): Holzminden, Germany, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Musculus, J.C.; Eckhardt, A. Der Deichatlas des Johann Conrad Musculus von 1625/26. Faks; Holzberg: Oldenburg, Germany, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Stadler, K. Die Gemeindewappen der Bundesländer Niedersachsen und Schleswig-Holstein; Angelsachsen-Verl.: Bremen, Germany, 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Veddeler, P. Wappen, Siegel, Flaggen. Die kommunalen Hoheitszeichen des Landschaftsverbandes, der Kreise, Städte und Gemeinden in Westfalen-Lippe; Ardey: Münster, Germany, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Hildebrandt, A.M. Handbuch der Heraldik. 19., Verb. und Erw. Aufl.; Nikol: Hamburg, Germany, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, B.R. The Encyclopedia of Religion and Nature; Thoemmes Continuum: London, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Engel, A. Weserbuch. Ein erklärender Begleiter auf der Weserreise mit Berücksichtigung der Fulda von Kassel ab. Repr. d. Ausg.; Niemeyer: Hameln, Germany, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Hernández-Morcillo, M.; Plieninger, T.; Bieling, C. An empirical review of cultural ecosystem service indicators. Ecol. Indic. 2013, 29, 434–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ridding, L.E.; Redhead, J.W.; Oliver, T.H.; Schmucki, R.; McGinlay, J.; Graves, A.R.; Morris, J.; Bradbury, R.B.; King, H.; Bullock, J.M. The importance of landscape characteristics for the delivery of cultural ecosystem services. J. Environ. Manag. 2018, 206, 1145–1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiele, J.; Albert, C.; Hermes, J.; von Haaren, C. Assessing and quantifying offered cultural ecosystem services of German river landscapes. Ecosyst. Serv. 2020, 42, 101080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tengberg, A.; Fredholm, S.; Eliasson, I.; Knez, I.; Saltzman, K.; Wetterberg, O. Cultural ecosystem services provided by landscapes: Assessment of heritage values and identity. Ecosyst. Serv. 2012, 2, 14–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanik, N.; Aalders, I.; Miller, D. Towards an indicator-based assessment of cultural heritage as a cultural ecosystem service—A case study of Scottish landscapes. Ecol. Indic. 2018, 95, 288–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tenerelli, P.; Demšar, U.; Luque, S. Crowdsourcing indicators for cultural ecosystem services: A geographically weighted approach for mountain landscapes. Ecol. Indic. 2016, 64, 237–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Berkel, D.B.; Tabrizian, P.; Dorning, M.A.; Smart, L.; Newcomb, D.; Mehaffey, M.; Neale, A.; Meentemeyer, R. Quantifying the visual-sensory landscape qualities that contribute to cultural ecosystem services using social media and LiDAR. Ecosyst. Serv. 2018, 31, 326–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wartmann, F.M.; Purves, R.S. Investigating sense of place as a cultural ecosystem service in different landscapes through the lens of language. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2018, 175, 169–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plieninger, T.; Bieling, C.; Fagerholm, N.; Byg, A.; Hartel, T.; Hurley, P.; López-Santiago, C.A.; Nagabhatla, N.; Oteros-Rozas, E.; Raymond, C.; et al. The role of cultural ecosystem services in landscape management and planning. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2015, 14, 28–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vrbičanová, G.; Kaisová, D.; Močko, M.; Petrovič, F.; Mederly, P. Mapping Cultural Ecosystem Services Enables Better Informed Nature Protection and Landscape Management. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).