Abstract

Among the countless attractions awaiting tourists in Mexico are towns characterized by an exceptional atmosphere, which in conjunction with natural environmental attractions, leads one to believe that these places are magical. The promotion of tourism in Mexico rests on the principle of cultural and environmental diversity and includes a development program called Pueblos Mágicos. This program is designed to help expand small towns’ tourism offering and to create new jobs in the service sector that normally accompanies tourism. This growth in the employment level is supposed to produce a direct impact on the lives of members of the local community in terms of their standard of living and quality of life. The aim of the present paper is to examine the effects of the implementation of this program in a comprehensive manner. The viewpoint examined is that of the local population and its living conditions. Employment levels in towns designated Pueblos Mágicos are examined in the paper, as is the rate of business development. A comprehensive index is used in the study to analyze these issues. The index of exclusion in the study also varies from town to town—both statically and over time. The paper also examines a number of other studies that have focused on the benefits and downsides of this program. Thus, the aim of this paper is to provide a comprehensive analysis of the effects of the introduction of the tourism development program Pueblos Mágicos (PPM) from the perspective of its impacts on the quality of life of the residents of the affected towns, based on statistical data such as job growth rates and marginalization, as well as a review of existing studies. Research has shown that the Pueblos Mágicos program has not substantially improved the quality of life of residents in Mexican towns designated Pueblos Mágicos. In fact, in some cases, the quality of life has, in some respects, declined over the course of the program’s functioning. However, it is conceivable that with a proper town vetting process the program may yet produce better results in terms of improvements in the quality of life of Pueblo Mágico town residents.

1. Introduction

Tourism is one of the most important and most dynamic economic sectors in Mexico, which also happens to be one of the most important tourist destinations in the world in terms of international tourist volume, as measured in 2018. Prior to the outbreak of the coronavirus, Mexico was ranked 7th in the world as a tourist destination with over 41 million tourists per year [1]. Tourism accounted for 8.6% of Mexico’s GDP, rising 4 percentage points since 2011 [2]. High tourist interest in Mexico can be explained by its wealth of resorts, environmental attractions, and cultural sites associated by most tourists with the monumental remnants of former civilizations dating back at least hundreds of years. However, small towns are also a tourist attraction in Mexico and often provide some vestiges of their colonial past, as well as a unique cultural atmosphere. In conjunction with additional characteristics such as interesting environmental features, these small towns represent exceptionally unique places on the map of Mexico, although they remain undervalued as tourist destinations.

In many cases, such exceptional towns are located in less economically developed areas or remain in the shadow of large cities that attract all sorts of investment but trigger population loss in smaller towns. One solution to this problem is the introduction of various types of local tourism growth programs meant to stimulate economic development by taking advantage of a host of local tourist attractions, as well as by activating existing community potential to increase the quality of life in these areas. In Mexico, the promotion of tourism rooted in cultural diversity and environmental value is managed via a program called Pueblos Mágicos (PPM). This program is designed to offer a fresh perspective on the management of growth in the Mexican tourism sector [3,4].

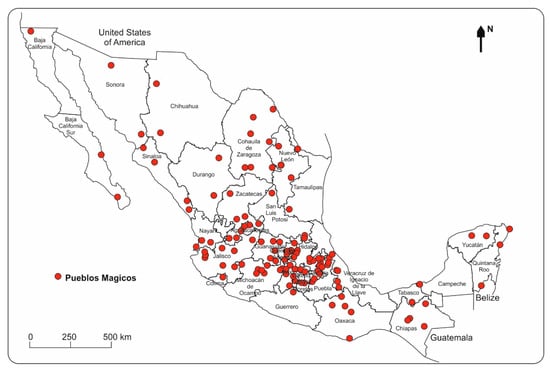

The inclusion of a town in the PPM is associated with an array of analyses on the local potential for tourism growth. One of the benefits of this program is new funding for the selected towns’ physical infrastructure, marketing image, and overall municipal functioning. The very designation of a town via this program creates growth opportunities for the local community, which becomes more attractive for investment purposes, especially in the area of tourism sector development. Inclusion in the program normally leads to an improved tourism offering, and this translates into increased employment in services associated with the tourism sector. Job growth naturally impacts the local community, which is supposed to be the main beneficiary of the Pueblos Mágicos Program (PPM). The newfound economic development must serve the needs and quality of life goals of local residents. Figure 1 shows the spatial distribution of all currently designated Pueblos Magicos in Mexico.

Figure 1.

Pueblos Mágicos in Mexico. Source: Authors’ own work, based on [5].

The PPM has been examined by researchers in a variety of ways [3]. Most literature sources analyze this program in terms of its overall functioning within selected towns [6,7,8,9,10,11]. A more holistic approach concerned with its implementation and its functioning is presented in works by F. Madrid [4,12] and Núñez Camarena and Ettinger Mc Enulty [13].

Some researchers focus on specific issues such as the functioning of the program as an element of each examined town’s local economy [4,14,15,16]. The existence of the Pueblos Mágicos program has also been analyzed in terms of improved quality of life and a more structured approach to economic development [6,17,18,19,20]. Some researchers also note the negative impacts of intensified tourist traffic resulting from the effects of the program, which include key social and cultural changes [10,21,22].

The literature includes an array of works on the relationship between tourism and the quality of life of local residents [23,24,25,26]. Studies in this area [27,28] have shown that increased tourism also generates increased crime levels, higher costs of living, changes in lifestyles, and conflicts between tourists and the local community. All of this may lead to a decline in the quality of life for local area residents.

The Sustainable Tourism Development Plan created by the UNWTO [29] includes an array of issues associated with plans to reduce poverty levels by increasing the number of jobs in poor areas and by stimulating local business activity. This plan assumes that an improvement in the quality of life of local area residents will occur [9]. In recent years, the number of studies on the implementation and functioning of sustainable development principles in tourism has increased considerably. Current thinking focuses on an equilibrium between three specific areas of tourism development—environmental, social and cultural, and economic aspects [30,31,32,33,34,35]. Moreover, when local residents support tourism development goals, this translates into a higher quality of life for them [36].

Existing studies do not focus extensively on changes in employment levels in tourism in the aftermath of the implementation of economic stimulation programs, and consequently they do not focus on the impacts on the quality of life of local residents. Few studies cover employment levels in tourism beyond the case study level. Thus, the purpose of the present study is to assess the effectiveness level of the economic stimulus of the PPM in its early stages and its potential impact on the quality of life of local residents. The study is also designed to examine problems such as social exclusion and marginalization associated with peripheral location relative to any larger cities in a given region. Changes in the level of marginalization of populations living in small towns in Mexico have not been studied extensively in the literature. Thus, it is important to produce a comprehensive analysis of the effects of the implementation of economic growth programs on the quality of life of local residents. It appears that, in the case of tourist towns, it is important to connect quality of life with sustainable development and tourism, as sustainable development principles should be considered in the process of creating any economic stimulus programs such as PPM. In addition, it is also important to note that the literature on the various aspects of Pueblos Mágicos is mostly available in the Spanish language. Thus, the present paper is also designed to help expand the pool of readers who may be interested in the effects of such a development program. The present paper is supposed to help make international comparisons easier by providing analysis in the English language.

2. Tourism versus Quality of Life in the Context of Sustainable Development

The concept of quality of life is subjective. It reflects the views of individuals on various aspects of life, as well as their emotions and feelings. The various elements of quality of life affecting one’s perceived level of satisfaction with one’s life change depending on one’s hierarchy of needs and cultural determinants. Yet individuals’ sense of quality of life remains a fairly universal phenomenon [27]. Quality of life is multifaceted and multidimensional, which is why it is also very difficult to define [37,38,39,40,41]. It covers a broad array of aspects of daily life, well-being, surroundings, relationships, and social and cultural linkages [42,43]. This is why a really comprehensive analysis of human quality of life ought to include subjective feelings defined by the individual [24,44]. The various components of quality of life examined in the study include both objective measures, such as household appliance use, household income, and infrastructural metrics, and also subjective measures such as the sense of one’s satisfaction with various aspects of life [45]. One aspect noted by many researchers is material welfare; this includes employment and economic security [46,47,48]. Economic welfare is one of the key drivers of societal satisfaction with life. It is largely determined by one’s employment status, type of work available, and overall satisfaction with one’s job [49,50]. However, quality of life remains largely dependent on the standard of living (it is the objective layer of the quality of life), and determinants that may be described as “objectively relevant” are household income, living conditions, level of unemployment, level of education, and others.

The assumption behind tourism development in Mexico is that the sector is supposed to grow in a manner which respects the natural environment, local cultures, and local communities [9,51]. Tourism strongly affects the lives of local residents [36]. This is especially true in the case of small towns in poorly developed areas and in areas that simply do not possess any other means of economic development. Tourism can affect the quality of life of local residents in a variety of ways. One way of improving the lives of local residents is to make tourism products more accessible, and thus usable, by local residents, not just tourists. Such “products” include restaurants, cultural attractions, local events and festivals, and environmental attractions [27,52]. Job growth is certainly one way to make tourism more useful to local residents, which consequently makes their lives better via higher household incomes [27]. On the other hand, increased tax revenues from tourism-related firms may lead to more investment in infrastructure at the local level and the development of services that also serve the local community.

The view of local residents on the issue of tourism development and tourists themselves is also quite relevant. Research has shown that the main factor triggering a positive view among local residents is the creation of tourism-related jobs for local residents—jobs that make them dependent on the continued success of the sector [52,53,54,55].

The whole idea of sustainable development in the tourism sector assumes progress in the area of economic, social, and cultural change without generating new threats to the natural environment [56]. The goal is to grow the tourism sector at the same rate as would be attained without sustainable development strategies, but in this case without triggering a decline in the natural resources that serve as the basis for the development.

The idea of sustainable tourism development rests on four basic principles: (1) natural environmental protection—development occurs without disturbing ecological processes and local biodiversity and without damaging natural resources; (2) community preservation—growth in line with local community values and with the goal of preserving local community identity; (3) cultural preservation—compliance of new cultural development with local cultural norms; and (4) economic growth—utilization of resources in a manner that makes the process economically viable at the present time, as well as in the future. Sustainable development in the tourism sector may be examined in two different ways—(1) from the perspective of local communities and (2) in terms of the quality of the tourist experience [56]. This, in effect, implies the creation of diverse tourist destinations and new opportunities for tourists to spend their free time [9]. This approach generates tourist satisfaction through contact with nature and culture, but in a way that respects local heritage, natural and cultural. Optimal utilization of environmental resources must go hand in hand with respect for the social and cultural authenticity of the host community. Unfortunately, traditional tourism practices often involve the uncontrolled exploitation of local resources.

Activities related to sustainable tourism need to be regulated and sometimes controlled, to some extent, by the government, especially in the area of natural and cultural heritage. This approach needs to involve key local community members in the planning and implementation process [51]. Sustainable development is the responsibility of both public and private entities. This is why it is important for local business leaders and representatives of local community organizations to become involved in the planning process associated with the implementation of tourism-related projects. This process involves making decisions, as well as organizing and completing the subsequent stages of projects. It is also important to underscore the need for collaboration with local communities in order to prevent discrepancies between what is assumed in a project and what is assumed in local spatial and development management plans [56]. Studies have shown that support for tourism growth at the local community level results not only from the expectation of economic benefits but also from the expectation of non-economic benefits in the form of changes in mentality, local policy, and social climate [57].

3. Pueblos Mágicos Program versus Other Tourism Development Programs in Mexico

3.1. Tourism Development Programs in Mexico

National economic development plans in Mexico tend to position tourism as the primary form of economic activity in the country. This is why the Ministry of Tourism creates tourism products designed to trigger social and economic development through the utilization of major natural and cultural resources. These development plans include financial investment designed to prompt economic activity and job creation [58,59]. Mexico has produced a number of programs since the 1970s that aim to protect its rich cultural heritage with limited success in some cases. Some of these programs search for new promotional opportunities and new ways of developing peripheral areas outside of the standard route of promoting recreation and archeological tours [60].

The aforementioned programs are meant to help trigger growth in the tourism sector and in other areas of the economy where historical heritage and local culture that remain largely unknown to the majority of visitors need to be maintained. Tourism represents a valuable portion of the Mexican economy, and it is a particularly important element of the economy of less developed, rural parts of the country. Economic stimulus programs are, by design, supposed to help reduce economic inequality between backward rural areas and developed urban areas. Another reason for the creation of such programs is to help diversify tourism away from what are known to be the traditional areas of tourism concentration along the country’s coastlines, in the direction of noncoastal areas that require the development of new tourism products.

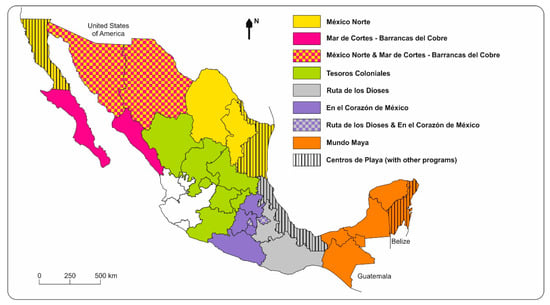

Mexico’s Secretaria de Turismo (SECTUR) has been monitoring eight regional programs, in effect, since 2001 (Figure 2). The programs are designed to help stimulate economic development across a number of local communities, mostly located in the interior of the country, via the use of a common marketing policy in the area of tourism and common development plans. An important feature of these plans is the strategy of developing many different types of tourism including cultural tourism, which currently constitutes one of the largest attractions of the country [60]. The aforementioned programs are supposed to help improve the functioning of selected tourist regions in Mexico by elevating their position in domestic and international markets. Promotional activities common to several regions represent a vital part of these programs, as do innovative tourism products created using market research and well-established marketing techniques. Some programs involve the creation of specialized products based on the unique characteristics of a given tourist site. They also underscore increasing the competitiveness levels and profitability of tourist towns and the entities that operate therein. In addition, economic stimulus programs help create a unique brand for the towns they serve, and this helps generate positive associations and feelings for tourists. According to F. Madrid [4], the greatest value created by such programs consists of the production of a common brand and the marketing benefits that result from being part of a recognizable brand.

Figure 2.

Regional tourism development programs in Mexico. Source: Authors’ own work, based on [61].

The PPM represents a special case among the various development programs offered in Mexico. It is the only program to cover the whole country and requires a level of collaboration among the various levels of local government and national ministries. It was established in 2001 and designed to promote the unique tourist value of small towns located in peripheral areas along with the development of tourist infrastructure in these towns and the creation of an innovative tourism offering that would satisfy growing demand for culture-based tourism rooted in the tourist discovery of local traditions, adventure tours, and pursuit of so-called extreme sports. The program is currently very important for the tourism sector due to its large spatial reach and well-established functioning [62]. However, the development of small tourist towns, regardless of how extensive their environmental and cultural potential is, normally requires at least some financial investment.

3.2. Pueblos Mágicos Program—Assumptions and Functioning

The PPM plays a special role in Mexico due to its orientation toward local development [63]. The initial goal of the program was to help structure a complementary and diverse tourist offering for peripheral areas via the utilization of the cultural and historical characteristics of these areas. The local communities that are located quite far away from the most popular Mexican tourist destinations are characterized by some unique features, which were then used to create tourism products based on local arts and crafts, unique gastronomy, and local festivals [60]. Being located far away from large urban centers, many rural communities have developed unique cultural traditions in unique environmental settings. Hence the program assumes the possibility of enhancing the competitiveness of these towns and rural areas via their establishment as places to pursue adventure tourism, extreme sports, eco-tourism, and sports fishing [58,64]. PPM thus assumes that tourism can become an economic growth driver helping local residents grow their incomes via new employment opportunities, new investment triggered by the development of the tourism market, and other ways of improving the local quality of life [65].

The PPM aims to diversify the tourism sector and utilize new spaces and opportunities that generate attractions associated with material and nonmaterial heritage [66]. It is also designed to help position Mexico as an international tourist destination [58], in accordance with the following assumptions published by SECTUR in 2017, which extend the basic principles set forth in the establishment process for PPM: “[the program] is designed to search for new ways of utilizing both environmental and cultural assets of the country as well as encourage public and private investment designed to improve the welfare of local populations. In light of this perspective, the most general goal of the said program is to promote the sustainable development of towns possessing unique characteristics and a real authenticity by supporting their attractiveness through an exceptional and prestigious brand” [67].

The Pueblo Mágico town (PM) is, by design, supposed to be characterized by very specific symbolic attributes. According to Mexico’s Secretariat of Tourism (SECTUR), these are defined as the following:

“A place that has resisted the tide of modernization through its historical, cultural as well as environmental heritage, and manifests this heritage via its material and nonmaterial assets. A Pueblo Mágico is a locality which is home to symbolic characteristics, legends, local history, transcendental facts, everyday life, and magic that manifest themselves on many different levels in terms of society and culture, which further create an excellent opportunity to be utilized by the tourism sector. The program sets out to change social perceptions that have persisted for a long time in the national imagination and aims to offer a fresh alternative for visitors”.[5,67]

The most important official goals of the program are the following:

- The creation of a complementary and diverse tourist offering targeting development in peripheral parts of the country characterized by the presence of many unique and special places featuring historical and cultural assets valuable from the perspective of tourism development;

- Development and promotion of local arts and crafts, holidays, traditions, as well as food;

- Creation of concrete tourism products including adventure, extreme sports, eco-tourism, and fishing packages;

- Assessment of and support for existing tourist attractions in these areas that serve as new and alternative destinations for domestic and foreign tourists increasingly seeking a new type of tourist experience [67].

Towns and villages which are part of the PPM should possess a certain “magic” that is self-manifesting and apparent in every aspect of life therein. The definition of “magic” is not fixed in this case. Likewise, it is possible to understand symbolic attributes, history, and everyday life in many different ways. This makes it possible to easily approximate these vital characteristics or differ from them [58,60,68]. The lack of a sense of clarity in these definitions yields an array of opportunities for local government action and a range of broad interpretations that may help utilize a given local asset for tourist purposes. At the same time, the lack of clarity can lead to different forms of abuse, which is particularly problematic in Mexico, where corruption remains an issue in many facets of everyday life. In this situation, the role of political and social activists is quite important, as they represent local communities already in the program and those aspiring to become part of the program. Initial assumptions of the Pueblos Mágicos program included criteria that had to be fulfilled in order to become part of the program. These included community and local government engagement, creation and implementation of planning instruments designed to regulate business activity, a host of economic stimulus targets, creation of local tourist attraction and service packages, and further development of local skills used in local industries [11].

One requirement that needs to be fulfilled to join the PPM is a basic population requirement—it needs to exceed 20,000. Candidate towns may not be located more than two driving hours away from existing tourist centers. In this sense, they supplement the tourism offering already provided by key Mexican cities [3,58]. Other key requirements include the following:

- Preparation of a complementary and diverse tourism offering based first and foremost on the historical, cultural, and environmental attractions of the given town;

- Utilization of unique characteristics of the given town in the creation and improvement of existing tourism products;

- Increases in expenditures to support local communities;

- Improvement in the quality of rendered tourist services;

- Enhanced professionalism among tourist sector workers;

- Motivation to pursue new investment opportunities;

- Coordination of actions pursued by town authorities;

- Reorganization of actions in towns already part of the program;

- Promotion of tourism development as a sustainable development tool in towns admitted to the program [67].

Municipal authorities in towns applying to the PPM are required to file a complete set of documents covering administrative agendas on the tourism sector as well as a catalogue of providers of tourist services, inventory of tourist attractions, and local plan of tourism development [3,67]. In exchange for fulfilling the above set of requirements, a town obtains the right to use the “Pueblo Mágico” logo and associated designation, which have become recognizable trademarks over the last few years of the program’s existence. In addition, member towns receive federal government funds for the purpose of improvements in infrastructure, services, and town image. The funding may be used to improve the quality of tourist areas or to create and expand tourism products, and to enhance the quality of other services [3,67].

The idea to utilize the potential of PMs is the outcome of changing travel preferences and other considerations as well. Today, tourists search for new, alternative ways of traveling that ensure new types of experiences and emotions. Such experiences are available in PMs, which generate “magic” that leaves tourists with unforgettable experiences. Modern society, and this includes tourists and small town residents, is becoming more aware of the need to find new ways of exploring culture and the natural environment—ways that do leave the observer with a new perspective on things. The first thing that a tourist experiences in a new and exceptional place is emotions, which are the result of existing attractions as well as additional opportunities provided by development programs. These include festivals, meeting culture events, unique infrastructure, and local authenticity. In light of the availability of these special attractions, program coordinators produce pathways of promoting sustainable tourism consistent with well-defined requirements.

The requirements set forth in the PPM have changed over the years of the program. They were more rigorous until 2010—tourism products had to be accurately catalogued and a tourist services development plan had to be formulated. After 2010, during the presidency of Felipe Calderon, the requirements were adjusted to become more moderate, partly due to political considerations [13,69,70]. The introduction of less rigorous requirements led to a very large increase in the number of Pueblos Mágicos in Mexico. These new member towns often did not meet the more rigorous initial requirements in place in 2010 [65,66,71]. This newfound leniency became the subject of criticism from politicians and business leaders [13].

4. Materials and Methods

The impact of membership in the PPM on economic growth in the tourism sector was examined by analyzing employment levels and the number of companies present in each studied PM. The study focused on towns admitted to the program between 2001—or its very beginning—and 2009. Statistical material for whole townships (Spanish: municipios) home to Pueblos Mágicos—MPMs—was examined. The program affects not just each member town, but also its surroundings, which is why they were also included in the analysis. Six of the studied MPMs did not have statistics available and were excluded from further analysis. In the next stage of research, the studied PMs were placed in two groups:

- Group I—PM1—towns admitted to the PPM in the years 2001–2004 (13 towns). In this group, changes in employment levels and the number of firms present are noted for the period 2004–2009. Townships with PM1 towns were designated MPM1;

- Group II—PM2—towns admitted to the PPM in the years 2005–2009 (13 towns). In this group, changes in employment levels and the number of firms present are noted for the period 2009–2014. Townships with PM2 towns were designated MPM2.

Changes in employment levels and business development in the tourism sector were assessed using statistical data available from the Instituto Nacional de Estadistica y Geografia (INEGI) [72,73,74]. The analysis is limited to Pueblos Mágicos designated in the period 2001–2009 because of the availability of statistical data that could be later compared. In subsequent years, the method for reporting changes in employment levels changed. The data are only comparable for the years 2004, 2009, and 2014. In addition, the number of new member towns in later years became rather large, which then triggered criticism and charges of politically motivated decision making. It was argued that the new member towns did not really meet the requirements set out in the initial version of the PPM.

Statistical material collected for the purpose of analysis concerned the number of firms present in each town and employment levels at temporary lodging facilities such as hotels and bed and breakfast facilities, service providers in the area of food and drink preparation, and retail stores offering food items. The above data were used for townships with MPM status to calculate the rate of change in employment levels and number of business entities. The rate of change was calculated for all such townships for the periods 2004–2009 and 2009–2014. The resulting data were then standardized using averages and standard deviations, which produced partial comprehensive indices for each given characteristic for the two studied time periods. In turn, the partial indices were used to yield a comprehensive index for townships with Pueblos Mágicos for the two time periods.

Values of the comprehensive index were calculated using the formula below:

where:

x—values of variables examined in the study;

µ—mean value of the studied variables;

ơ—standard deviation of the examined variables;

i—selected indicator.

Thus, the data were standardized for the purpose of comparing the studied MPMs. Data for entire Mexican states were also examined—states where the studied towns and townships are located—and township-level data were then subtracted from state-level data. This made it possible to assess whether changes occurring in the studied townships are a reflection of changes in their respective states.

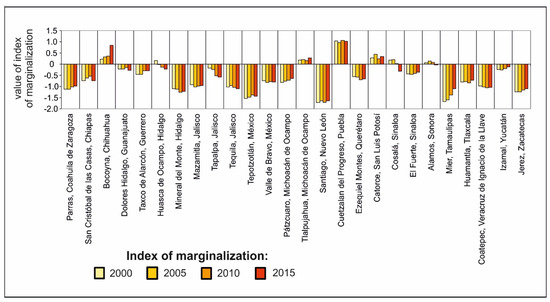

The marginalization index (CONAPO) was used to assess the Quality of life in the PM. The index revolves around the educational levels of town residents, household infrastructure, employment levels, and household income. The index was calculated for 2000, 2005, 2010, and 2015 [75]. Information on the program itself and the subjective sense of well-being was obtained via a critical analysis of documents, reports, research publications, and newspaper editorials.

The total index of marginalization was used to assess changes in the objective layer of quality of life in the MPM. This index is used to show the level of exclusion resulting from a lack of access to basic goods and services. It covers issues such as the level of illiteracy and the share of the population with only an elementary level of educational attainment at the age of 15 or older, as well as employment and pay levels, household infrastructure, such as electricity in the home, drinking water, bathroom, access to wastewater systems, and floor type, and finally the degree of overcrowding in the home. The index has a value of zero for the country as a whole—the average for Mexico in general. The study examines results for the studied townships for the years 2000, 2005, 2010, and 2015. Partial indices that serve in the construction of the full index constitute important components of the quality of life of the noted populations. Educational attainment tends to translate into one’s potential for economic growth and overall well-being. In addition, improvements in physical infrastructure represent a critical factor affecting the quality of life of the studied populations [40,76].

5. Results

5.1. Characteristics of the Studied Towns

Table 1 contains descriptions of the characteristics of the studied PMs.

Table 1.

Description of the studied PMs.

Table 2.

Description of tourist values in studied PMs.

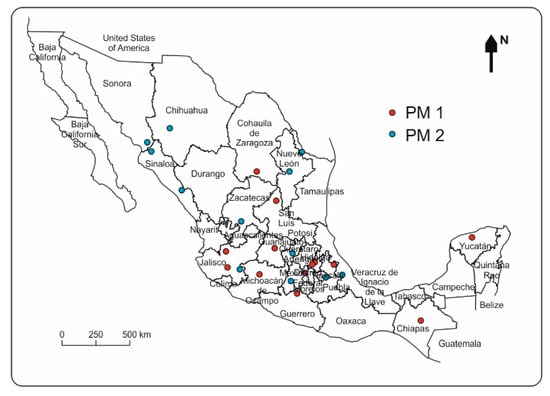

Figure 3.

Location of the studied PMs in Mexico. Source: Authors’ own work.

Table 1.

Description of the studied PMs.

| Characteristic | Description |

|---|---|

| Geographic location | The studied PMs were located in 25 Mexican states out of the 32 in the country. Five states are home to more than one program town. The states of Jalisco and Michoacan are home to three towns each (Figure 3). The studied towns vary in population. The largest is the town of San Cristobal de las Casas with a population of more than 215,000 residents. Dolores Hidalgo is ranked second with 114,000 residents. The smallest towns were Huasca de Campo, with 860 residents, and Real de Catorce, with 2300 residents [77]. |

| Admission to the PPM | A total of 32 towns were admitted into the PPM, of which 26 were selected for further analysis. The first study period covered 13 PM1 towns. The second study period also covered 13 PM1 towns. In 2001, only two towns were admitted to the PPM. In 2002, it was eight—the largest number per year in the studied period. In 2008, no towns joined the PPM [78]. |

| Types of PM | The studied PMs were examined in terms of tourist attractions that had led to their admission to the PPM. These attractions were placed in four distinct categories: cultural, natural environmental, sites of local festivals, and mixed (see Table 2). All of the examined towns offer mostly cultural attractions (almost 60% of all the available attractions). These include archeological sites, museums, churches, and monasteries. Environmental attractions constitute only 8% of all the attractions available in the PMs. These are mostly national parks. The studied towns feature more than 100 different festivals associated with local holidays and traditions. The largest number of tourist attractions was observed for the towns of Tequila (22 attractions, including 16 cultural attractions, 2 environmental attractions, and 4 festivals), Ciudad Mier (19 attractions, including 16 cultural attractions, 2 mixed-type attractions, and 4 festivals), and Mazamitla (18 attractions, including 5 cultural attractions, 3 environmental attractions, 6 mixed-type attractions, and 4 festivals). In summary, the primary type of attraction in most of the studied PMs is cultural attractions, which serve to produce what is known as the “magic” and “atmosphere” components required by the studied program [78]. |

Source: Authors’ own work based on [78].

5.2. Changes in Employment Levels and Number of Firms in Selected Townships

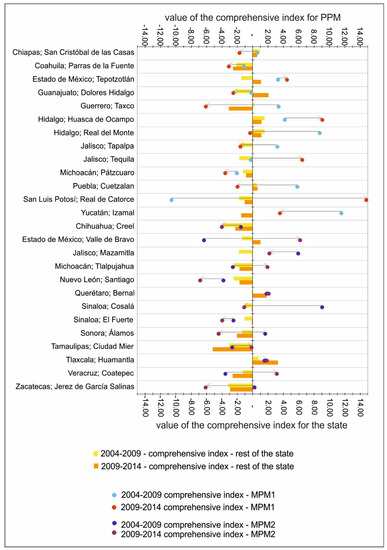

Figure 4 provides values of the comprehensive index for MPM1 and MPM2 townships, as well as for the states where the studied townships are located. Index values were calculated for all towns in the study for both study periods, which made it possible to compare trends at all of the noted towns. The highest comprehensive index values for the period 2004—2009 were observed for MPM1 Izamal (11.52), MPM2 Cosalá (9.05), and MPM1 Real del Monte (8.69). The lowest value in this period was noted for MPM1 Real de Catorce (−10.6). The same township, Real de Catorce, was observed to have the highest value for the second study period (14.77). Second and third place were occupied by MPM1 Huasca del Ocampo (9.05) and MPM1 Tequila (6.43), respectively.

Figure 4.

Comprehensive index for MPMs and the rest of the states. Source: Authors’ own compilation based on [72,73,74].

Of the townships admitted to the PPM in the years 2001–2004 (MPM1), only three cases were observed to experience an increase in the comprehensive index between the periods 2004–2009 and 2009–2014. At the same time, an increase in the index was noted for six states with MPM1 townships. In this group, there were four cases where the index value for the state would increase while the index value for the township would decline for the same time period. The opposite situation was observed in only one case where an increase in the index value for a township accompanied a corresponding decline in the index value for the state with that particular township (MPM Huasca de Ocampo, State of Hidalgo).

On the other hand, in the MPM2 group (towns admitted to the program in 2004–2009), an increase in the comprehensive index value was noted for six townships and for the six states containing these six MPM2 townships. In six cases, the increase in the index value for the state did not correspond to an increase for the applicable township. This was true in four cases. An increase in the index value was noted for only two townships where was a decline for all other townships in the corresponding state (MPM Ciudad Mier in the state of Tamaulipas and MPM Coatepec in the state of Veracruz).

The above data may be used to show that the inclusion of a town in the PPM did not trigger a clear response on the part of the town’s economy in the form of strong increases in employment rates and the number of local firms associated with tourism. It is also apparent that the second studied group, MPM2, responded more positively to inclusion in the program: the economic response to this event was more robust. This may be due to the fact that the program had already been tested on the first studied group of PMs. It is also possible that towns in the second group had been selected more effectively in terms of tourism growth. However, the most important fact seems to be that a decline in the comprehensive index value was noted for most of the studied MPMs, which implies weak economic growth in the area of tourism. The decline in employment levels and number of firms present in each studied MPM indicates that the economic situation in these towns has become worse, and the quality of life of their residents has, in effect, decreased over time.

5.3. Quality of Life in the Studied Townships—Objective Measures

The analysis of index of marginalization values for the studied MPMs versus time (Figure 5) shows that the vast majority of studied townships achieved a result below the national average during all of the studied years. Only in four cases (MPM Bocoyna, MPM Tlapujahua, MPM Cuetzalan de Progreso, MPM Catorce) was the index value above the national average for the entire studied time period. In the case of MPM Cuetzalan del Progreso, this was the highest value for all the townships studied in all the study periods (1.04333, 0.9591, 1.0597, 1.027, respectively). In four subsequent cases, the initially positive index values declined below zero. The lowest index values were calculated for MPM Santiago (−1.7044, −1.6274, −1.7196, −1.627, respectively). These were the lowest index values for all the townships studied for every studied period.

Figure 5.

Index of marginalization in the years 2000, 2005, 2010 and 2015 for MPMs. Source: Author’s own compilation based on [75].

With the exception of two townships (MPM Bocoyna and MPM Mier), there was no clear improvement in the objective layer of the quality of life of residents following the admission of their township to the PPM. It is noteworthy that some components of the index used here concern the installation of physical infrastructure and improvements in this area constitute one of the key assumptions in the PPM. Thus, one may not assert that a substantial rise in the quality of life of town residents has occurred following admission to the said program. The lack of improved living conditions of the local population is also observed by Rodríguez Herrera and Pulido Fernández [11].

5.4. Effect of the PPM on the Quality of Life of Town Residents

Today, the PPM covers a broad group of very different towns in Mexico. Over the last 20 years, the program has created a strong brand for itself, and its logo is now easily recognized across Mexico. The program has become a desirable goal for many small towns in peripheral areas that view it as their only chance for social and economic growth. Yet the research literature points to a number of key problems rooted in the relatively uncontrolled development of the tourism sector in small towns. These are most often the problems that impact the local community directly, thus leading to conflict and making everyday life difficult. This type of downside to the program produces negative impacts on the life satisfaction level of the local communities it is designed to help [27].

The research literature provides examples of analyses of the effectiveness of the PPM based on selected case studies. These papers identify the various benefits associated with the program, but also its downsides. The table found below (Table 3) lists some of the most often cited impacts of the program on the quality of life of local residents:

Table 3.

Positive and negative impacts of the PPM on the quality of life of local residents.

6. Discussion

The tourism sector in Mexico has experienced a major transformation over the last several decades from mostly leisure-oriented tourism towards more cultural tourism including the pursuit of alternative cultural sites found away from major cultural hotspots. The PPM is part of this new trend of culture-oriented tourism in Mexico [70]. One of the main assumptions behind this program is the improvement of quality of life for local residents through the stimulation of the local economy and job creation, as well as physical investment not just in the tourism sector, but also in the improvement of the quality of life for town residents. The analysis of changes in employment levels in the tourism sector and changes in the level of exclusion of local residents shows that PPM has not substantially improved the quality of life in towns designated “Pueblos Mágicos”. The number of local businesses has declined in most cases. Employment levels have also declined in most of the studied towns. This is true both of towns designated PM in the first studied time period and of those designated PM in the second studied period of time.

Improvements in the quality of life come from a variety of sources, some of which are included in the index of exclusion used in this study. The analysis of changes in index values for towns designated PM in the first studied time period and second studied time period in fact shows that the program has not improved anything for these towns, at least not in the ways in which it was supposed to have improved their quality of life. In most of the studied cases, the index value has in fact declined, thus leading to a decline in the quality of life in the studied towns.

Local community expectations related to the PPM are frequently quite optimistic and include positive impacts such as a better marketing image and improved urban infrastructure [70,98]. However, research has shown that the actual effects are different from the expectations associated with the program. The literature was used to compile a list of positive and negative impacts of the PPM on member towns in terms of the effect on the quality of life of town residents. Studies do show positive impacts in the form of increased tourist traffic to PMs, development of services and urban infrastructure, improved image of the town, and more collaboration between local entities. They also note problems observed in many towns with this designation. These include lack of consultation with local residents and a feeling of exclusion on their part along with social polarization, increased costs of living, and a decline in traditional culture. Urban renewal is also sometimes criticized for its selectiveness. New buildings do not always reflect local architecture, and renewal often occurs only in parts visited by tourists, while other parts of town decline. In addition, the implementation of vital sustainable development policies is often made difficult by the prioritization of economic goals over social and ecological ones [99]. Quality of life is the product of these three types of goals, and the maintenance of an equilibrium between these goals leads to a rise in the level of satisfaction of local residents in relation to their own lives and their towns.

One main weakness of the analysis of employment levels and business development in the present paper is its limited scope; only the years 2004, 2009, and 2014 are covered. This was due to comparability issues associated with the available statistical material. A longer period of analysis may have shown a fuller picture of the changes occurring in the studied towns. On the other hand, we felt it was important to examine the first batch of towns admitted to the PPM, as they had been fully vetted via the more rigorous requirements first set out in the program in 2001. The first batch may be thought of as a laboratory for the impacts of the program. In addition, the political nature of changes in the program in later years made some towns’ admission to the program somewhat political, as opposed to fact-based [69]. This is why an examination of these later towns would have lowered the quality of the analysis of the statistics available for towns admitted in the early years of the PPM when program requirements were higher.

7. Conclusions

The admission of a town to the PPM leads to an array of changes that may or may not be positive. The program tends to generate new solutions, but also may in some cases reignite previously existing conflicts. The key goals set out in the PPM prescribe actions designed to help achieve sustainable development and an increase in the quality of life for local communities. However, research has shown that resulting changes due to tourism development tend to adapt PMs to the expectations of tourists, but do not necessarily reflect the needs and traditions of the local population, its pursuit of local authenticity, and protection of natural resources. This is a conclusion drawn based on the opinions and comments of local residents noting the various directions of change and investment paths designed to help local towns become more attractive to tourists. This may include the development of central areas for tourist use and, at the same time, a lack of development in peripheral areas inhabited by the local population. This pattern of change may be observed in the appearance of buildings which are designed to draw in tourists but without much consideration for the town’s cultural past. For example, some buildings are made to look colonial, even though they may have nothing to do with Mexico’s colonial past [21,66].

Targeted investment and tourism promotion may help PMs attain a higher status among Mexican tourist destinations. Readily observable development in such towns may help trigger additional investment by outside entities as well as an improvement in the living conditions of town residents.

There is a serious need for a more transparent process of admission of towns to the program, especially in the area of social improvement [100]. Such a change would make the program more effective over the long term. It is our view that PM status should be assigned to towns for a limited period of time, which could then be extended if certain results are in fact achieved. Two of the more important metrics that could be used to assess program results are employment levels and business development in each designated town. In addition, the level of satisfaction among town residents should be measured in order to assess the impacts of higher tourist traffic and the variety of changes resulting from higher tourist traffic. The present paper also yields a contribution on the specifics of this type of tourism development program and provides an alternative source of information, supplementing sources available in the Spanish language. The paper aims to provide a comprehensive analysis that accounts for global factors. Finally, non-Spanish speakers may use the paper for the purpose of international comparisons that account for the functioning of this type of program—the Pueblos Mágicos tourism development program.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.W.-R. and P.R.; methodology, A.W.-R. and P.R.; formal analysis, A.W.-R.; investigation, A.W.-R. and P.R.; writing—original draft preparation, A.W.-R.; writing—review and editing, A.W.-R. and P.R.; visualization, A.W.-R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

https://www.inegi.org.mx/programas/ce/2004/ (accessed on 27 November 2021); https://www.inegi.org.mx/programas/ce/2009/ (accessed on 27 November 2021); https://www.inegi.org.mx/programas/ce/2014/ (accessed on 27 November 2021); http://www.conapo.gob.mx/es/CONAPO/Datos_Abiertos_del_Indice_de_Marginacion (accessed on 27 November 2021); https://www.inegi.org.mx/app/areasgeograficas/default.aspx (accessed on 27 November 2021).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- International Tourism Highlights, 2020 Edition UNWTO. Available online: https://www.e-unwto.org/doi/pdf/10.18111/9789284422456 (accessed on 17 November 2021).

- Cuenta Satélite del Turismo de México, Dirección General de Integración de Información Sectorial, INEGI. Available online: https://www.datatur.sectur.gob.mx/SitePages/ProductoDestacado3.aspx (accessed on 17 November 2021).

- Núñez Camarena, G.M. Los pueblos mágicos de México: Mecanismo de la SECTUR para poner en valor el territorio. In VIII Seminario Internacional de Investigación en Urbanismo. Departament d’Urbanisme i Ordenació del Territorio; Universitat Politècnica de Catalunya: Barcelona, Spain, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Madrid, F. Gobernanza Turística = Destinos Exitosos: El Caso de los Pueblos Mágicos de México; VLA Laboratorio Visual, Universidad Anáhuac México Norte: Ciudad de México, México, 2014; p. 348. [Google Scholar]

- Pueblos Mágicos, Herencia que Impulsan Turismo, Secretaría de Turismo. Available online: https://www.gob.mx/sectur/articulos/pueblos-magicos-herencia-que-impulsan-turismo?idiom=es (accessed on 10 September 2021).

- Hoyos Castillo, E.; Hernández Lara, Ó. Localidades con recursos turísticos y el Programa Pueblos Mágicos en medio del proceso de la nueva ruralidad. Los casos de Tepotzotlán y Valle de Bravo en el Estado de México. Quivera 2008, 10, 111–130. [Google Scholar]

- Covarrubias Ramírez, R.; Conde Pérez, E.M. Percepción del nivel de satisfacción de los residentes con la actividad turística: Caso Comala, Colima, México. Rev. Tur. Desarro. Local Sosten. 2009, 2, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Covarrubias Ramírez, R.; Vargas Vázquez, A.; Rodríguez Herrera, I.M. Satisfacción de residentes con la actividad turística en los Pueblos Mágicos de México: Un indicador de competitividad. Casos de Comala en Colima y de Real de Asientos en Aguascalientes. Gestión Turística 2010, 14, 33–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velarde Valdez, M.; Maldonado Alcudia, A.V.; Maldonado Alcudia, M.C. Pueblos Mágicos Estrategia para el desarrollo turístico sustentable: Caso Sinaloa. Teoría Prax. 2009, 6, 79–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velázquez García, M.A.; Balslev Clausen, H. Tepoztlán, una Economía de la Experiencia Íntima. Lat. Am. Res. Rev. 2012, 47, 134–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez Herrera, I.M.; Pulido Fernández, J.I. Análisis del desarrollo turístico en los Pueblos Mágicos de México. Una revisión de los efectos de la política pública en los destinos mexicanos. In Retos para el turismo español. In Proceedings of the Cambio de Paradigma, XIV Congreso AECIT, Gijon, Spain, 8–20 November 2009; pp. 797–819. [Google Scholar]

- Madrid, F. Derivaciones epistémicas de una política pública: El caso de los Pueblos Mágicos 2001–2015. El Periplo SustenTable 2019, 36, 184–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Núñez Camarena, G.M.; Ettinger Mc Enulty, C. La transftormación de un territorio cultural. El desarollo de los Pueblos Mágicos en México: Pátzucaro como caso de estudio. Rev. Urbano 2020, 41, 40–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treviño Aguilar, E.; Heald, J.; Guerrero Rodríguez, R. Un modelo del gasto con factores sociodemográficos y de hábitos de viaje en Pueblos Mágicos del Estado de Guanajuato, México. Rev. Investig. Turísticas 2015, 10, 117–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Rojo Quintero, S.; Llanes Gutiérrez, R.A. Patrimonio y turismo: El caso del Programa Pueblos Mágicos. Topofilia Rev. Arquit. 2009, 1, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Loredo, J.L. Pueblos Mágicos entre el simulacro y la realidad. Topofilia 2012, 3, 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Guillén Lúgigo, M.; Valenzuela, B.A.; Jaime Rodríguez, M.E. Efectos del Programa Pueblos Mágicos en los residentes locales de El Fuerte, Sinaloa. Una aproximación al estudio de los imaginarios sociales. Topofilia 2013, 4, 776–784. [Google Scholar]

- Romero Samaniego, G.A. Descripción de la experiencia del recorrido de Álamos “Un itinerario de fantasmas”. Topofilia 2012, 3, 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez González, S.C. Pueblos Mágicos. Tiraje cinematográfico como estrategia de estudio del montaje a partir del imaginario turístico. Topofilia 2013, 4, 832–847. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez González, S.C. Metodología para el estudio del montaje de escenarios urbanos a partir del imaginario. IV Encuentro Latinoamericano de Metodología de las Ciencias Sociales. In Proceedings of the La Investigación Social ante Desafíos Transnacionales: Procesos Globales, Problemáticas Emergentes y Perspectivas de Integración Regional, Heredia, Costa Rica, 27–29 March 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Hernández López, J. Tequila: Centro mágico, pueblo tradicional. ¿patrimonialización o privatización? Andamios 2009, 6, 41–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojo Quintero, S.; Castañeda, M.E. El Programa “Pueblos Mágicos” en dos ciudades de origen minero del noroeste de México. Topofilia 2013, 1, 4. [Google Scholar]

- Santos-Júnior, A.; Almeida-García, F.; Morgado, P.; Mendes-Filho, L. Residents’ Quality of Life in Smart Tourism Destinations: A Theoretical Approach. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.; Uysal, M.; Sirgy, M.J. How does tourism in a community impact the quality of life of community residents? Tour. Manag. 2013, 36, 527–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woo, E.; Kim, H.; Uysal, M. Life satisfaction and support for tourism development. Ann. Tour. Res. 2015, 50, 84–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uysal, M.; Sirgy, M.J.; Woo, E.; Kim, H. Quality of life (QOL) and well-being research in tourism. Tour. Manag. 2016, 53, 244–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andereck, K.L.; Nyaupane, G.P. Exploring the Nature of Tourism and Quality of Life Perceptions among Residents. J. Travel Res. 2010, 50, 248–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tosun, C. Host Perceptions of Impacts: A Comparative Tourism Study. Ann. Tour. Res. 2002, 29, 231–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Tourism Organization. UNWTO Annual Report 2016. Available online: https://www.e-unwto.org/doi/epdf/10.18111/9789284418725 (accessed on 8 October 2021).

- Eslami, S.; Khalifah, Z.; Mardani, A.; Streimikiene, D.; Han, H. Community attachment, tourism impacts, quality of life and residents’ support for sustainable tourism development. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2019, 36, 1061–1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanafiah, M.H.; Jamaluddin, M.R.; Zulkifly, M.I. Local Community Attitude and Support towards Tourism Development in Tioman Island, Malaysia. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2013, 105, 792–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasoolimanesh, S.M.; Jaafar, M. Sustainable tourism development and residents’ perceptions in World Heritage Site destina-tions. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2017, 22, 34–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stylidis, D. Place attachment, perception of place and residents’ support for tourism development. Tour. Plan. Dev. 2017, 2, 188–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres-Delgado, A.; Palomeque, F.L. Measuring sustainable tourism at the municipal level. Ann. Tour. Res. 2014, 49, 122–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunkoo, R.; So, K.K.F. Residents’ support for tourism: Testing alternative structural models. J. Travel Res. 2016, 55, 847–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramkissoon, H. Perceived social impacts of tourism and quality-of-life: A new conceptual model. J. Sustain. Tour. 2020, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uysal, M.; Sirgy, J. Quality-of-life indicators as performance measures. Ann. Tour. Res. 2019, 76, 291–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theofilou, P. Quality of Life: Definition and Measurement. Eur. J. Psychol. 2013, 9, 150–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felce, D.; Perry, J. Quality of life: Its definition and measurement. Res. Dev. Disabil. 1995, 16, 51–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winiarczyk-Raźniak, A.; Raźniak, P. Regional differences in the standard of living in Poland (based on selected indices). Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2011, 19, 31–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zborowski, A. Przemiany Struktury Społeczno-Przestrzennej Regionu Miejskiego w Okresie Realnego Socjalizmu i Transformacji Ustrojowej (na Przykładzie Krakowa); Instytut Geografii i Gospodarki Przestrzennej, Uniwersytet Jagielloński: Kraków, Poland, 2005; p. 559. [Google Scholar]

- Organization of Economic Cooperation and Development. OECD Better Life Initiative: Compendium of OECD Well-Being Indicators. 2011. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/general/compendiumofoecdwell-beingindicators.htm (accessed on 12 October 2021).

- Shek, D.T.L. Protests in Hong Kong (2019–2020): A Perspective Based on Quality of Life and Well-Being. Appl. Res. Qual. Life 2020, 15, 619–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urtasun, A.; Gutiérrez, I. Tourism agglomeration and its impact on social welfare: An empirical approach to the Spanish case. Tour. Manag. 2006, 27, 901–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winiarczyk-Raźniak, A. Wybrane Usługi a Jakość Życia Mieszkańców w Regionie Miejskim Krakowa. Prace Monograficzne Uniwersytetu Pedagogicznego; Naukowe Uniwersytetu Pedagogicznego: Kraków, Poland, 2008; Volume 508, p. 159. [Google Scholar]

- Han, G.; Yan, S.; Fan, B. Regional Regulations and Public Safety Perceptions of Quality-of-Life Issues: Empirical Study on Food Safety in China. Healthcare 2020, 8, 275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szymańska, A.I. The Importance of the Sharing Economy in Improving the Quality of Life and Social Integration of Local Communities on the Example of Virtual Groups. Land 2021, 10, 754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anttila, J.; Jussila, K. Understanding quality—Conceptualization of the fundamental concepts of quality. Int. J. Qual. Serv. Sci. 2017, 9, 251–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilevičienė, T.; Bilevičiūtė, E.; Drakšas, R. Employment as a Factor of Life Quality. J. Int. Stud. 2016, 9, 203–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Second European Quality of Life Survey—First Findings. 2009. Available online: http://www.eurofound.europa.eu/pubdocs/2008/52/en/1/EF0852EN.pdf (accessed on 17 November 2021).

- Rosas Mantecón, A. Giro hacia el turismo cultural: Participación comunitaria y desarrollo sustentable. In Gestionar el Patrimonio en Tiempos de Globalización; Nivón, E., Mantecón, A., Eds.; Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana: Mexico City, México, 2010; pp. 107–130. [Google Scholar]

- Andereck, K.L.; Valentine, K.M.; Knopf, R.C.; Vogt, C.A. Residents’ Perceptions of Community Tourism Impacts. Ann. Tour. Res. 2005, 4, 1056–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Pfister, R.E. Residents’ Attitudes toward Tourism and Perceived Personal Benefit in a Rural Community. J. Travel Res. 2008, 47, 84–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.-P.; Cole, S.T.; Chancellor, C. Resident Support for Tourism Development in Rural Midwestern (USA) Communities: Perceived Tourism Impacts and Community Quality of Life Perspective. Sustainability 2018, 10, 802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, D.-W.; Stewart, W.P. A structural equation model of residents’ attitudes for tourism development. Tour. Manag. 2002, 23, 521–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelevska-Najdeska, K.; Rakicevik, G. Planning of Sustainable Tourism Development. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2012, 44, 210–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGehee, N.G.; Andereck, K.L. Factors Predicting Rural Residents’ Support of Tourism. J. Travel Res. 2004, 43, 131–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bustingorry, F. Pueblos Mágicos. El proyecto de patrimonialización de localidades mexicanas para promover el turismo. Ing. Tecnol. Cienc. Apl. 2016, 1, 49–53. [Google Scholar]

- Rosas-Jaco, M.I.; Almeraya-Quintero, S.X.; Guajardo-Hernández, L.G. Los comités Pueblos Mágicos y el desarollo turístico: Tepotzotlán y El Oro. Agric. Soc. Desarollo 2017, 14, 105–123. [Google Scholar]

- Bustingorry, F. Pueblos Mágicos. El proyecto de patrimonialización de localidades mexicanas para promover el turismo. In XI Jornadas de Sociología; Facultad de Ciencias Sociales, Universidad de Buenos Aires: Buenos Aires, Argentina, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- SECTUR—Programas Regionales. Available online: https://www.sectur.gob.mx/programas/programas-regionales/ (accessed on 27 September 2021).

- Enríquez, J.; Vargas, R. El estudio de los Pueblos Mágicos. Una revisión a casi 20 años de la implementación del programa. Dimens. Turísticas 2021, 5, 9–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez Corona, J. Desarollo local y turismo en México. Pueblos Mágicos en regiones metropolitanas. In Desarollo Regional Sustenable y Turismo; Pérez-Campuzano, E., Mota-Flores, V.E., Eds.; Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México y Asociación Mexicana de Ciencias para el Desarrollo Regional: México DF, México, 2018; pp. 902–927. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez Herrera, I.M.; Pulido Fernández, J.I.; Vargas Vásquez, A.; Shaadi Rodriguez, R.M. Dinámica relacional en los pueblos mágicos de México. Estudio de las implicaciones de la política turística a partir del análisis de redes. Tur. Soc. 2018, 22, 85–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durán-Díaz, P.; Armenta-Ramírez, A.; Kristiina Kurjenoja, A.; Schumacher, M. Community Development through the Empowerment of Indigenous Women in Cuetzalan Del Progreso, Mexico. Land 2020, 9, 163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Levi, L. Las territorialidades del turismo: El caso de los Pueblos Mágicos en México. Ateliê Geográfico 2018, 12, 6–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guía Para la Integración Documental Pueblos Mágicos. 2017. SECTUR. Available online: https://www.gob.mx/cms/uploads/attachment/file/273030/Gui_a_2017_de_Incorporacio_n_2017.pdf (accessed on 24 September 2021).

- Amerlinck, M.J. Arquitectura vernácula y turismo: ¿Identidad para quién? Tradic. Cult. Pop. 2008, 3, 381–388. [Google Scholar]

- Armenta, G. Cuál es la Situación Real de los Pueblos Mágicos, Faorbes. 2014. Available online: http://www.forbes.com.mx/develan-misterios-de-los-pueblos-magicos/ (accessed on 25 September 2021).

- López-Levi, L.; Valverde-Valverde, C.; Fernández-Poncela, A.M.; Figueroa-Díaz, M.E. (Eds.) Presentación. In Pueblos Mágicos. Una Visión Interdisciplinaria; Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana and Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México: Mexico City, Mexico, 2015; Volume 1, pp. 9–19. [Google Scholar]

- Puga, T.; Pueblos, M.; Pero, P. El Universal. 2018. Available online: https://www.eluniversal.com.mx/cartera/pueblos-magicos-pero-pobres (accessed on 15 September 2021).

- Censo Economico 2004, Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía (INEGI). Available online: https://www.inegi.org.mx/programas/ce/2004/ (accessed on 2 September 2021).

- Censo Economico 2009, Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía (INEGI). Available online: https://www.inegi.org.mx/programas/ce/2009/ (accessed on 2 September 2021).

- Censo Economico 2014, Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía (INEGI). Available online: https://www.inegi.org.mx/programas/ce/2014/ (accessed on 2 September 2021).

- Consejo Nacional de Población CONAPO, Datos Abiertos del Índice de Marginación. Available online: http://www.conapo.gob.mx/es/CONAPO/Datos_Abiertos_del_Indice_de_Marginacion (accessed on 28 September 2021).

- Winiarczyk-Raźniak, A. Standard of Living as Deprivation Index in Poland (Based on Selected Indices). In Environmental and Socio-Economic Transformations in Developing Areas as the Effect of Globalization; Wójtowicz, M., Winiarczyk-Raźniak, A., Eds.; Prace Monograficzne UP, Wydawnictwo Naukowe Uniwersytetu Pedagogicznego: Kraków, Poland, 2014; Volume 699, pp. 49–61. [Google Scholar]

- México en Cifras. Available online: https://www.inegi.org.mx/app/areasgeograficas/default.aspx (accessed on 17 November 2021).

- SECTUR—Pueblos Mágicos. Available online: http://www.sectur.gob.mx/gobmx/pueblos-magicos/ (accessed on 1 September 2021).

- Jacobo-Herrera, F.; del Progreso, P.C. Un pueblo mágico organizado por sus habitantes. In Pueblos Mágicos. Una Visión Interdisciplinaria; López-Levi, L., Valverde-Valverde, C., Fernández-Poncela, A.M., Figueroa-Díaz, M.E., Eds.; Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana and Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México: Mexico City, Mexico, 2015; Volume 1, pp. 67–86. [Google Scholar]

- Quiroz-Rosas, L.E. Tepoztlán, Morelos. Conformación socioespacial de un pueblo en resistencia. In Pueblos Mágicos. Una Visión Interdisciplinaria; López-Levi, L., Valverde-Valverde, C., Fernández-Poncela, A.M., Figueroa-Díaz, M.E., Eds.; Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana and Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México: Mexico City, Mexico, 2015; Volume 1, pp. 87–106. [Google Scholar]

- Valverde-Valverde, C.; López-Levi, L.; Fernández-Poncela, A.M. Huasca de Ocampo, Hidalgo. Donde la magia inicia. In Pueblos Mágicos. Una Visión Interdisciplinaria; López-Levi, L., Valverde-Valverde, C., Fernández-Poncela, A.M., Figueroa-Díaz, M.E., Eds.; Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana and Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México: Mexico City, Mexico, 2015; Volume 1, pp. 23–44. [Google Scholar]

- Enríquez-Acosta, J.; Guillén-Lúgigo, M.; Valenzuela, B.; Jaime, M.E. 2015, El Fuerte, Sinaloa. Turismo, transformaciones urbanas y sentido de lugar. In Pueblos Mágicos. Una Visión Interdisciplinaria; López-Levi, L., Valverde-Valverde, C., Fernández-Poncela, A.M., Figueroa-Díaz, M.E., Eds.; Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana and Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México: Mexico City, Mexico, 2015; Volume 2, pp. 273–298. [Google Scholar]

- Guzmán-Ríos, V. Tlalpujahua, Michoacán. Magia, espacio e imaginarios. In Pueblos Mágicos. Una Visión Interdisciplinaria; López-Levi, L., Valverde-Valverde, C., Fernández-Poncela, A.M., Figueroa-Díaz, M.E., Eds.; Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana and Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México: Mexico City, Mexico, 2015; Volume 1, pp. 131–157. [Google Scholar]

- Arévalo-Martínez, J.; Armas-Arévalos, E. Pueblos mágicos: Implicaciones para el desarrollo local. In Impactos Ambientales, Gestión de Recursos Naturales y Turismo en el Desarrollo Regional; Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México y Asociación Mexi-cana de Ciencias para el Desarrollo Regional: Ciudad de México, México, 2019; pp. 633–650. [Google Scholar]

- Lara, M. El presupuesto participativo como herramienta de inclusión. El programa Pueblos Mágicos. In Pueblos Mágicos: Discursos y Realidades. Una Mirada Desde las Políticas Públicas y la Gobernanza; Hernández, R., Ed.; Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana–Lerma y Juan Pablos Editor: Lerma, México, 2015; pp. 55–85. [Google Scholar]

- Barrera de la Torre, G. Real de Catorce, San Luis Potosí. Entre la minería y el turismo. In Pueblos Mágicos. Una Visión Interdisciplinaria; López-Levi, L., Valverde-Valverde, C., Fernández-Poncela, A.M., Figueroa-Díaz, M.E., Eds.; Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana and Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México: Mexico City, Mexico, 2015; Volume 1, pp. 45–65. [Google Scholar]

- Duarte Flores, E. Cuitzeo, Michoacán. La desapropiación social del patrimonio y espacio público. In Pueblos Mágicos. Una Visión Interdisciplinaria; López-Levi, L., Valverde-Valverde, C., Fernández-Poncela, A.M., Figueroa-Díaz, M.E., Eds.; Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana and Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México: Mexico City, Mexico, 2015; Volume 1, pp. 159–185. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Ramírez, C.A.; Antolín-Espinosa, D.I. Programa Pueblos Mágicos y desarrollo local: Actores, dimensiones y perspectivas en El Oro, México. Estud. Soc. 2016, 25, 219–243. [Google Scholar]

- Jiménez-Martínez, A.J. Desarrollo Turístico y Sustentabilidad. El caso de México; Miguel Angel Porrua: México DF, Mexico, 2005; p. 191. [Google Scholar]

- Shaadi Rodríguez, R.M.A.; Pulido-Fernández, J.I.; Rodríguez Herrera, I.M. El producto turístico en los Pueblos Mágicos de México. Un análisis crítico de sus componentes. Rev. Estud. Reg. 2017, 108, 125–163. [Google Scholar]

- Fuentes-Carrera, J. 2015, Huamantla, Tlaxcala. Magia efímera. In Pueblos Mágicos. Una Visión Interdisciplinaria; López-Levi, L., Valverde-Valverde, C., Fernández-Poncela, A.M., Figueroa-Díaz, M.E., Eds.; Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana and Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México: Mexico City, Mexico, 2015; Volume 1, pp. 187–202. [Google Scholar]

- Chavoya-Gama, J.I.; Rodríguez-Ávalos, M.L.; Muñoz-Macías, H. Entre el escenario de la tradición y la emergencia del turismo: Talpa, San Sebastián del Oeste y Mascota. Topofilia 2013, 4, 761–777. [Google Scholar]

- Ramírez, I.; Osorio, M.; Nieto, C.; Cortés, I. Así son, así se imaginan ellos, o así los imaginamos? Reflexiones sobre las trans-formaciones socioterritoriales del turismo residencial en Malinalco, México. Rev. Estud. Urbano Reg. 2017, 43, 143–164. [Google Scholar]

- Valenzuela, A. Patrimonio, turismo y mercado inmobiliario en Tepoztlán, México. PASOS Rev. Tur. Patrim. Cult. 2017, 15, 181–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valenzuela, A.; Saldaña, M.; Vélez, G. Identidad, estructura barrial y controlsocial del espacio en Tepoztlán, Morelos. Topofilia 2012, 3, 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- Delgado, M. Ciudades sin ciudad. La tematización ‘cultural’ de los centros urbanos. In Antropología y Turismo. Claves Culturales y Disciplinares; Lagunas, D., Ed.; Universidad Autónoma del Estado de Hidalgo: Pachuca de Soto, México, 2007; pp. 91–108. [Google Scholar]

- Zúñiga López, L.F. Chiapa de Corzo, Chiapas. El turismo como opción de desarrollo. In Pueblos Mágicos. Una Visión Interdisciplinaria; López-Levi, L., Valverde-Valverde, C., Fernández-Poncela, A.M., Figueroa-Díaz, M.E., Eds.; Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana and Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México: Mexico City, Mexico, 2015; Volume 1, pp. 341–355. [Google Scholar]

- Fierro-Reyes, I.G.; Rodriguez-González, R.; Corral-Molina, R.; Rascón-Pérez, P.I. Creel, Chihuahua. La puerta mágico-turistica a la Sierra Tarahumara. In Pueblos Mágicos. Una Visión Interdisciplinaria; López-Levi, L., Valverde-Valverde, C., Fernández-Poncela, A.M., Figueroa-Díaz, M.E., Eds.; Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana and Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México: Mexico City, Mexico, 2020; Volume 5, pp. 47–72. [Google Scholar]

- Dodds, R.; Butler, R. Barriers to implementing sustainable tourism policy in mass tourism destinations. Tour. Int. Multidiscip. J. Tour. 2010, 5, 35–53. [Google Scholar]

- Winiarczyk-Raźniak, A.; Raźniak, P. Magia Meksyku—Pueblos Mágicos w przestrzeni turystycznej kraju. Stud.-Dustrial Geogr. Comm. Pol. Geogr. Soc. 2019, 33, 112–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).