Abstract

This study, based on stable hydrogen and oxygen isotope observations of multiple water bodies (precipitation, river water, soil water, and groundwater) in the Ami Dongsou alpine arid watershed on the southern slope of the Qilian Mountains during 2023–2024, reveals significant seasonal fluctuations in water isotope characteristics and water source renewal mechanisms. The results show that precipitation and soil water exhibit notable enrichment during the dry season, primarily due to enhanced evaporation causing light isotopes to evaporate and heavy isotopes to accumulate. River water, influenced by both precipitation recharge and evaporation, shows smaller seasonal fluctuations. Groundwater isotopes remain stable, reflecting a slower water source renewal process with minimal seasonal influence. Through quantitative comparisons of the evaporation line’s slope and intercept, this study finds that precipitation is most significantly affected by evaporation, while groundwater is least influenced, showing more stable isotope characteristics. Climate and topography in high-altitude areas significantly regulate water isotope characteristics, especially during the dry season, where evaporation plays a dominant role in the enrichment of precipitation and river water isotopes. This study innovatively establishes an evidence framework for the linkage of multiple water body isotopes, revealing the “seasonal strong fluctuations + differential water body responses + high-altitude regulation” mechanism of water isotopes in alpine arid regions. It provides new data support for water resource management, particularly in aspects such as water source allocation during the dry season, groundwater protection, and evaporation enrichment effect prediction. Future research could expand the sample size and integrate multi-source data and hydrological models to further improve the accuracy of hydrological process predictions, offering more precise support for watershed water resource management and ecological protection.

1. Introduction

In high-altitude arid regions, such as the Ami Dongsou small watershed on the southern slope of the Qilian Mountains, the extreme climatic conditions, significant elevation differences, and limited precipitation present unique hydrological challenges. These areas are particularly susceptible to the impacts of climate change, and the availability of water resources is critical for both human populations and ecosystems. A deep understanding of the hydrological dynamics in these regions is essential for predicting water scarcity and ensuring sustainable water resource management in the future. The Ami Dongsou small watershed, with its extreme altitude, seasonal climate variations, and arid conditions, provides a valuable model for studying the water dynamics of cold arid regions.

Stable hydrogen and oxygen isotopes (δ2H and δ18O) are widely used in hydrological studies to reveal the composition, transport pathways, and transformation processes of water sources in the hydrological cycle [1]. These isotopes provide crucial information for understanding key hydrological processes such as evaporation, precipitation, recharge, and water body mixing. They are essential tools for analyzing the relationships between precipitation, surface water, and groundwater at the watershed scale [2,3]. By integrating isotope data, we can gain a deeper understanding of hydrological systems and their complex interactions [4,5,6].

In arid and high-altitude areas, extreme climatic conditions and significant evaporation effects result in strong spatiotemporal variability in water body isotope signals [7,8]. These regions typically have distinct water vapor sources and atmospheric transport paths, with evaporation processes significantly enriching heavy isotopes in water bodies, which in turn affects the isotope characteristics of rivers, soil water, and groundwater [9,10]. Especially in high-altitude areas, seasonal temperature gradients and climate changes produce significant elevation effects and seasonal trends in isotope composition [11,12].

Despite a substantial body of research on the application of stable isotopes in hydrology, including studies in high mountain regions across the globe [13,14], the comprehensive evolutionary patterns of isotope characteristics across different water bodies (precipitation, river water, groundwater, and soil water) and their relationship with regional climate–hydrological processes remain inadequately explained. Several studies have addressed the effects of local climate conditions, topography, and seasonal variations on isotope composition in mountain watersheds, yet the combination of these factors at the small watershed scale has not been systematically studied. This study aims to fill this gap by selecting the Ami Dongsou small watershed on the southern slope of the Qilian Mountains as the research site, using stable isotope data collected from precipitation, river water, groundwater, and soil water during 2023–2024. The main objectives of the study are as follows: (1) to explore the spatiotemporal variation characteristics of isotopes in different water bodies; (2) to analyze the combined effects of evaporation, recharge, elevation, and seasonal variations on water body isotope signals; and (3) to investigate the influence of local climate conditions and topography on water body isotope composition in high-altitude arid areas. The results will provide a new perspective on hydrological processes in cold arid regions and offer scientific support for future water resource management and ecosystem protection in similar regions.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Overview of the Study Area

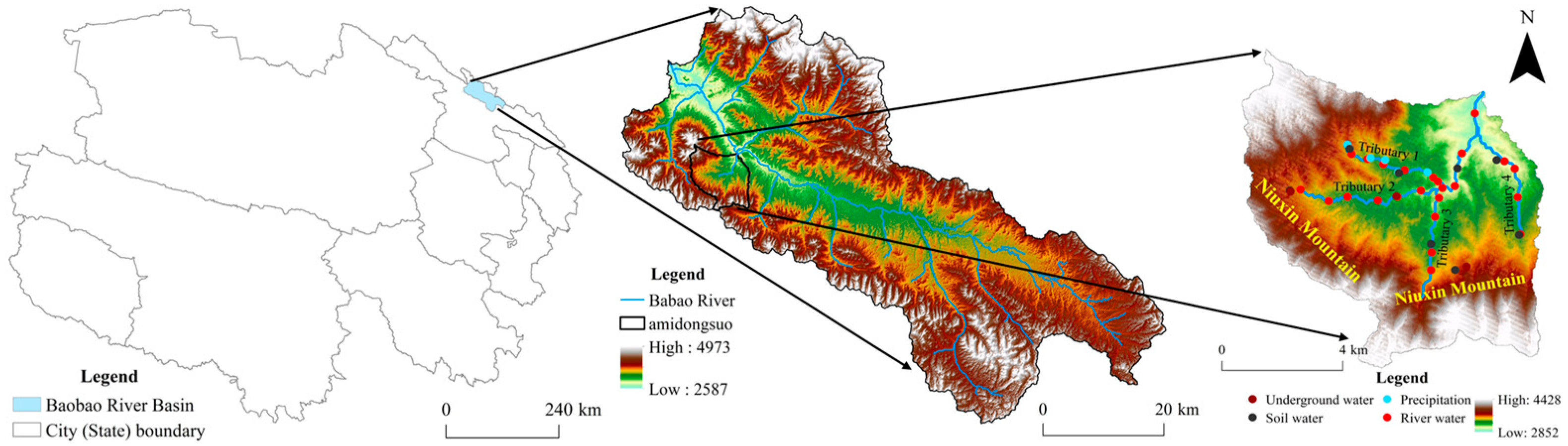

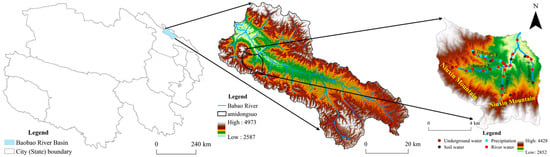

This study area is located in the Ami Dongsou watershed in Qilian County, Haibei Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture, Qinghai Province, with geographic coordinates ranging from 100°17′ E to 100°45′ E and 38°01′ N to 38°25′ N. The elevation varies from 2800 m to 4667 m, with bare rock exposure above 3600 m, as shown in Figure 1. The entire watershed is a valley running from east to west, with a total length of 14 km. The highest peak in the watershed is known as Niuxin Mountain, which is the main peak of the Tuolai Mountain range, a subrange of the Qilian Mountains. The dominant lithology consists of acidic igneous rocks, conglomerates, and sandstones [15]. As a water conservation area within the Qilian Mountain National Park, the Ami Dongsou watershed is a typical region at the transition between the Tibetan Plateau and arid zones. The river ultimately flows into the Heihe River, serving as a crucial water source for the Hexi Corridor and downstream oasis agriculture. The watershed is characterized by towering mountains and significant snow and ice coverage, making it a typical glacier and snowmelt-fed water source region [16]. The topography within the watershed varies considerably, with the southern region consisting of high mountain areas, while the northern part gradually transitions into low mountains and hills, creating a distinct vertical zonal landscape.

Figure 1.

Schematic map of study area and sampling points.

The Ami Dongsou watershed is not only an important area for hydrological process studies but also plays a critical role in regional water resource security. The precipitation and snowmelt in this watershed are vital for water supply to downstream areas. As shown in Figure 1, the study established 13 soil water sampling points, 11 precipitation collection points, 40 river water collection points, and 6 groundwater collection points across four tributaries in the watershed, covering three types of ecosystems. This comprehensive sampling scheme aims to investigate the isotope characteristics of various water bodies, particularly the isotopic composition of precipitation, river water, and groundwater. This research is crucial for understanding the watershed’s hydrological cycle and water resource management.

2.2. Sample Collection

Sample collection in the watershed was conducted at sampling points across different altitudes ranging from 2800 m to 4200 m to ensure spatial representativeness. Water samples were collected from four sources, precipitation, river water, groundwater, and soil water, covering different hydrological processes within the watershed.

2.2.1. Precipitation Samples

Precipitation samples were collected between July and September 2023 and April to September 2024 within the study area. To prevent isotope fractionation during sample collection, a custom-made precipitation collection device was used. This device consists of a polyethylene bottle and a wide-mouth funnel, tightly connected to the bottle. A layer of paraffin oil was added inside the bottle to prevent evaporation and maintain isotope stability. Precipitation was directed through the funnel into the bottle, minimizing exposure to air. After each precipitation event, the samples were immediately transferred into 30 mL plastic bottles, sealed with PARAFILM, and stored in a freezer under low-temperature conditions. Three parallel samples were collected for each precipitation event to ensure the representativeness and reliability of the results.

2.2.2. Soil Water Samples

To obtain the hydrogen and oxygen isotope composition of soil water, soil samples were collected at different vertical profiles in representative microtopographic locations within various ecosystems in the study area. The ecosystems selected for sampling included grasslands, shrublands, and forests, which were chosen to represent the primary vegetation types in the region. These ecosystems were selected based on their different water retention capacities, vegetation cover, and evaporation intensities, which are expected to lead to distinct isotope characteristics in the soil water. The sampling period coincided with precipitation sample collection for comparative analysis. A hand drill or soil auger was used to collect samples at the following depths: 0–10 cm, 10–20 cm, 20–30 cm, 30–50 cm, and 50–70 cm. Three parallel samples were collected at each depth. After collection, 20–30 g of soil was immediately placed in glass bottles with screw caps and PTFE liners, sealed with PARAFILM to prevent moisture evaporation and isotope fractionation. To extract soil water for isotopic analysis, the LI-2100 automatic vacuum extraction system from the Qinghai Province Key Laboratory of Physical Geography and Environmental Processes was used. The system processed 14 samples per batch, with each batch undergoing a 3 h extraction period. The extraction process was carefully controlled to prevent isotope fractionation, achieving a water extraction rate of over 98%. This method ensured that the soil water samples were free from evaporation and isotope bias, providing accurate results for the hydrogen and oxygen isotope analysis.

2.2.3. Groundwater Samples

The groundwater samples were collected from naturally flowing groundwater (spring water), and no detailed geological–hydrogeological information regarding sampling depth or specific aquifer types was provided. Springs with stable water flow and minimal human and livestock interference were chosen. Clean polyethylene bottles were used to directly collect spring water while avoiding prolonged contact with air. Two to three parallel samples were taken from each spring point. After collection, the bottles were immediately sealed, and PARAFILM was used to close the bottle mouths. The samples were transported in coolers at low temperatures and stored at −20 °C in the laboratory for subsequent δD and δ18O analysis.

2.2.4. River Water Samples

River water samples were collected from four tributaries within the study area, with sampling points chosen approximately 1 m from the riverbank in areas of faster flow. Three parallel samples were taken from each tributary. Clean polyethylene bottles were used to directly collect the river water samples, and prolonged exposure to air was avoided. After collection, the samples were immediately sealed, and the bottle mouths were closed with PARAFILM. The samples were then transported in coolers at low temperatures to the laboratory and stored at −20 °C for later isotope analysis.

2.3. Data Processing

Hydrogen and oxygen stable isotope measurements of various water bodies were conducted at the Qinghai Lake Wetland Ecosystem National Observatory Research Station, located on the Qinghai–Tibet Plateau, China. The station is managed by the Qinghai Province Key Laboratory of Physical Geography and Environmental Processes. The LI-2100 automated vacuum condensation extraction system was used to extract moisture from the collected plant and soil samples. All water samples were filtered through a 0.22 μm filter membrane, and analyzed using the liquid water isotope analyzer (T-LWIA-45-EP) from Los Gatos Research. During the analysis, the sequence of “3 samples + 1 standard” was followed, with each sample being measured continuously six times. The first two measurements, which may be affected by memory effects, were discarded, and the average of the remaining four measurements was taken as the final value. The data were uniformly exported using the LWIA Post Analysis software. The method precision was: δD (δ2H) ± 0.34‰, δ18O ± 0.05‰. The relevant calculation and conversion formula is as follows [2]:

where δX represents the stable hydrogen and oxygen isotope composition of the sample; Rsample is the ratio of heavy to light isotope abundance in the sample; Rstandard is the ratio of the heavy to light isotope abundance in the internationally recognized standard, typically the Vienna Standard Mean Ocean Water (VSMOW) for hydrogen and oxygen isotopes.

Statistical analysis of the δ18O, δD values, and deuterium excess data for precipitation, river water, groundwater, and soil water was conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics 26.0 and ArcGIS Pro software (Environmental Systems Research Institute). Graphs and charts were created using Origin 2024b.

3. Results

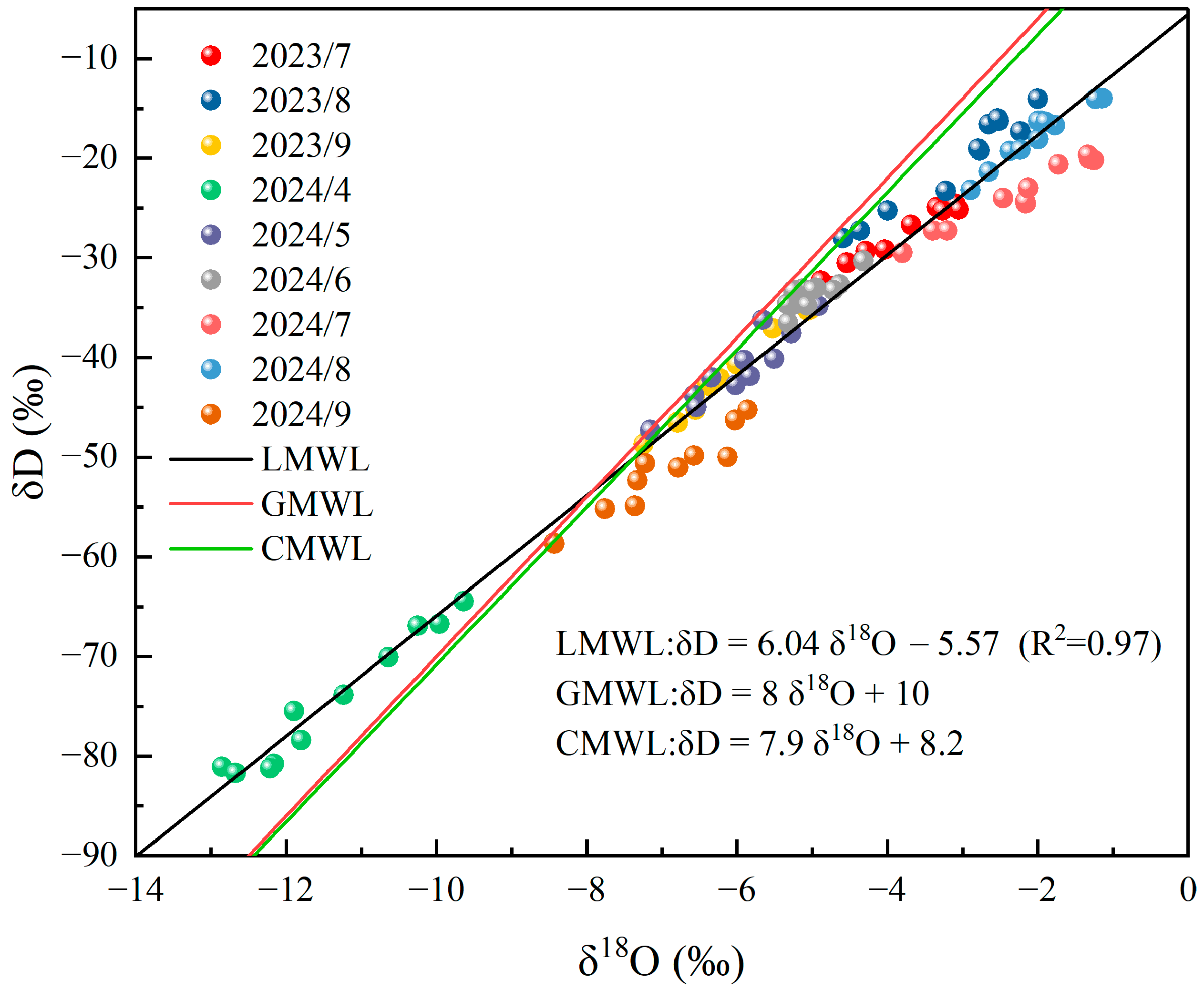

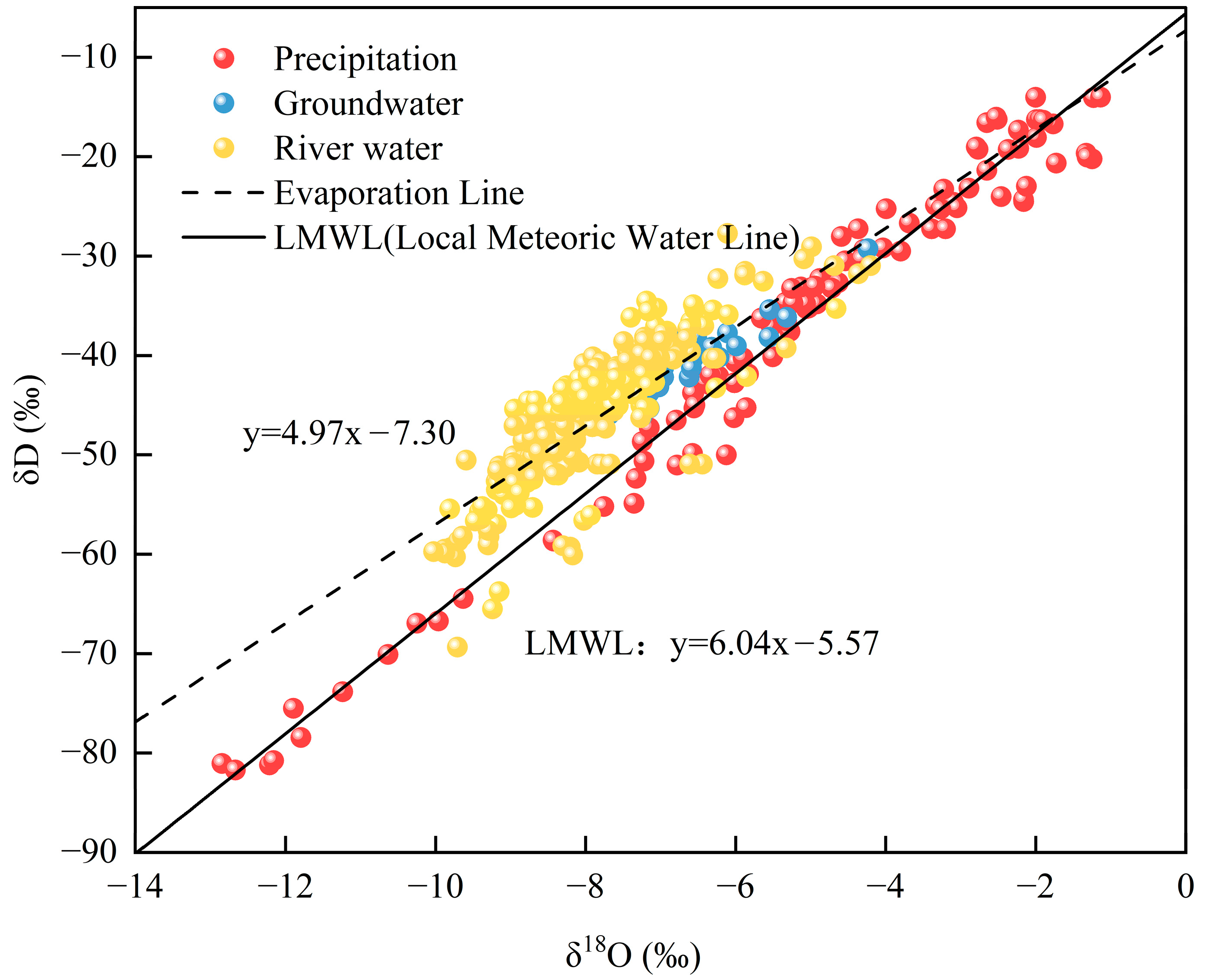

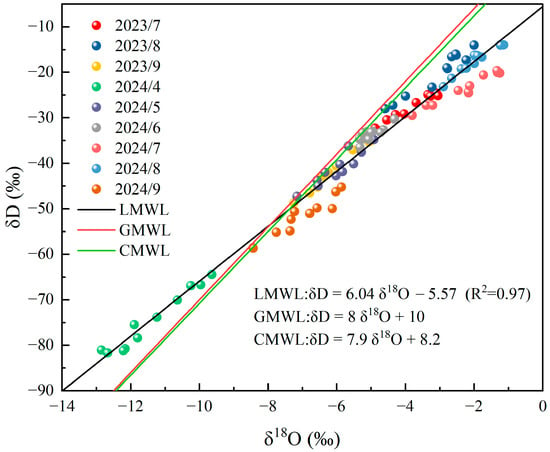

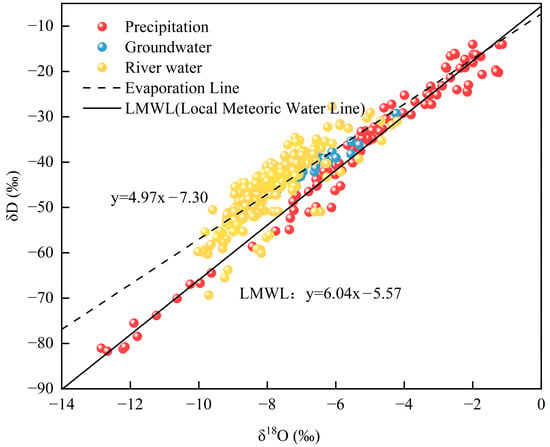

3.1. Atmospheric Precipitation Line

This study is based on the time-series data of precipitation samples from the watershed, and linear fitting analysis was performed on the δD and δ18O values in the water bodies. Figure 2 shows the isotopic characteristics of the watershed’s precipitation samples and presents the fitting analysis of the regional Local Meteoric Water Line (LMWL). The results indicate that the isotopic fit of precipitation has an R2 value of 0.97, with a significance level of p < 0.0001, demonstrating a significant positive correlation between δD and δ18O. This further confirms the high consistency of the stable isotopic characteristics of precipitation water vapor in the region.

Figure 2.

Atmospheric Precipitation Line of the Watershed. Note: The method precision is as follows: δD (δ2H) ±0.34‰, δ18O ±0.05‰. LMWL: Local Meteoric Water Line; GMWL: Global Meteoric Water Line; CMWL: China Meteoric Water Line.

From the fitting results, the local meteoric water line (LMWL) shows a lower slope (6.04) and intercept (−5.57), a feature that suggests significant evaporation fractionation in the watershed’s water bodies, particularly during the growing season. Specifically, during the warm season, due to enhanced evaporation, light isotopes (such as δD and δ18O) are more easily separated from the water vapor, resulting in relatively lower isotopic values in precipitation, reflecting a strong evaporation fractionation effect.

To further understand the characteristics of precipitation water vapor in this region, the watershed’s precipitation line was compared with the Global Meteoric Water Line (GMWL) [17] and the Chinese Meteoric Water Line (CMWL) [18]. The results show that the slope and intercept of the watershed’s precipitation line are significantly lower than those of the GMWL and CMWL. Specifically, the slope of the GMWL is 8.0, while the slope of the local precipitation line is 6.04, indicating that precipitation water vapor in this region undergoes more evaporation fractionation during transport. Similarly, compared with the CMWL (slope = 7.98), the slope and intercept of the watershed’s precipitation line are both lower, further emphasizing that the source of precipitation water vapor in this region is influenced not only by the monsoon system but also by strong control from mountainous terrain and local climatic conditions.

Especially in high-altitude areas, due to lower temperatures, water vapor undergoes more significant isotopic fractionation during the cooling process, leading to relative enrichment of light isotopes in precipitation, resulting in lower δD and δ18O values. This indicates that the isotopic characteristics of watershed precipitation are influenced not only by the monsoon system and climatic zones but also by strong control from local mountainous terrain and climatic conditions, exhibiting obvious regional differences. The autumn samples exhibited lower δD and δ18O values compared to summer samples, mainly due to cooler temperatures in autumn, leading to stronger isotopic fractionation during the cooling process. Additionally, the lower evaporation rates and different moisture sources contribute to the lighter isotopic composition of the autumn precipitation.

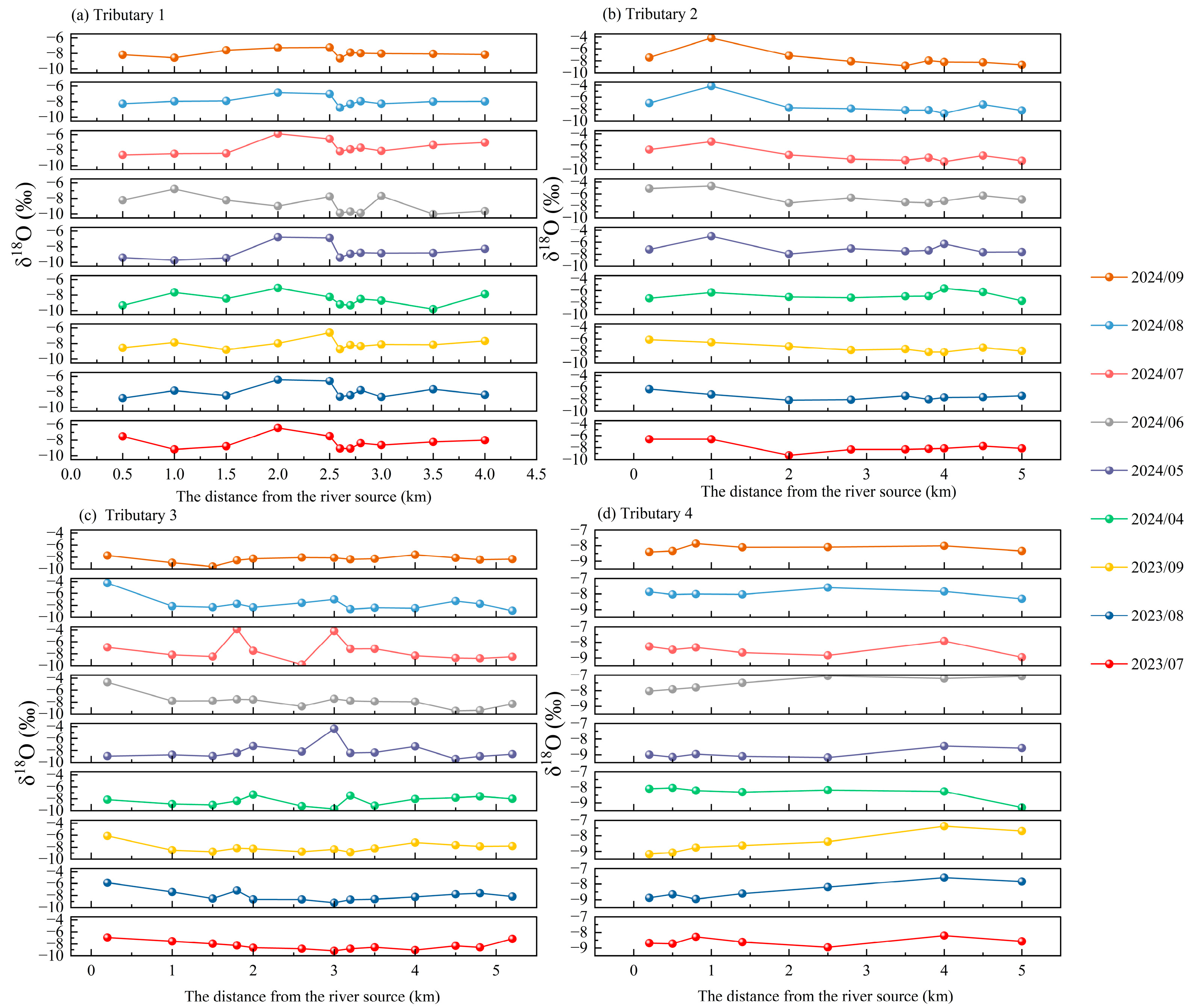

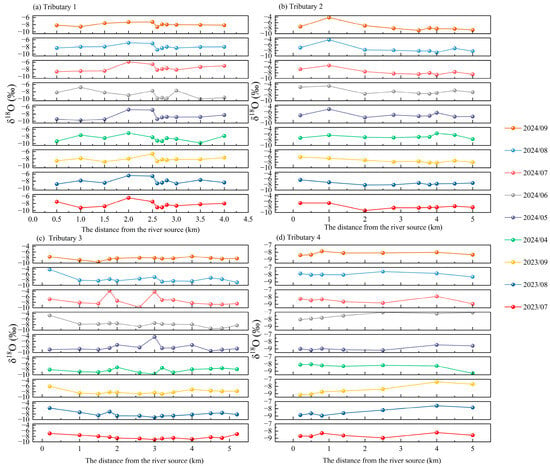

3.2. Oxygen Stable Isotope Characteristics of River Water

The Ami Dongsou small watershed consists of four tributaries, each with distinct hydrological characteristics and variations in oxygen isotope composition. Figure 3a–d show the temporal variation in river water δ18O in the four tributaries, covering data from July 2023 to September 2024. Each curve represents the δ18O values of river water at different distances from the river source during a particular month, with δ18O values changing as the river flows downstream. Each point on the curve represents the δ18O value of the river water at a specific distance from the river source in that month.

Figure 3.

Temporal Variation Characteristics of δ18O in River Water from Four Tributaries. Note: The figure shows the variation in isotopic data at each sampling point along the four tributaries of the watershed, from the river source to the farthest point, measured monthly. Different colors represent different months. The method precision is as follows: δD (δ2H) ± 0.34‰, δ18O ± 0.05‰.

Tributary 1 (Figure 3a) exhibited lower δ18O values near the source area from July to September 2023, with the δ18O values gradually increasing as the distance from the river source increased, indicating an enhancement of the evaporation effect. From April to September 2024, with the intensification of evaporation, the δ18O values steadily increased, especially in May and June, approaching −6‰. By July, the δ18O values stabilized near −5‰, showing significant isotopic enrichment.

Tributary 2 (Figure 3b) displayed a similar trend in δ18O values from July to September 2023 as Tributary 1, but the isotopic depletion of the water was more pronounced. From April to September 2024, δ18O values gradually increased, particularly in May and June, approaching −5‰, also showing isotopic enrichment. Unlike Tributary 1, the δ18O changes in Tributary 2 were relatively smooth, without any sharp fluctuations.

Tributary 3 (Figure 3c) had lower δ18O values from July to September 2023, but the enrichment trend from April to September 2024 was relatively stronger. In particular, δ18O values significantly increased to near −5‰ in June and July, indicating enhanced evaporation during the summer. However, the enrichment in Tributary 1 was more pronounced than in Tributaries 2 and 3, especially in the segment from the source to the 2 km mark, where the δ18O values increased significantly.

In Tributary 4 (Figure 3d), δ18O values showed isotopic depletion from July to September 2023, but, unlike the other tributaries, the enrichment in this tributary was more moderate. In June and July, δ18O values rose to near −6‰, but compared to the other tributaries, the enrichment process was more gradual, without any noticeable sharp changes.

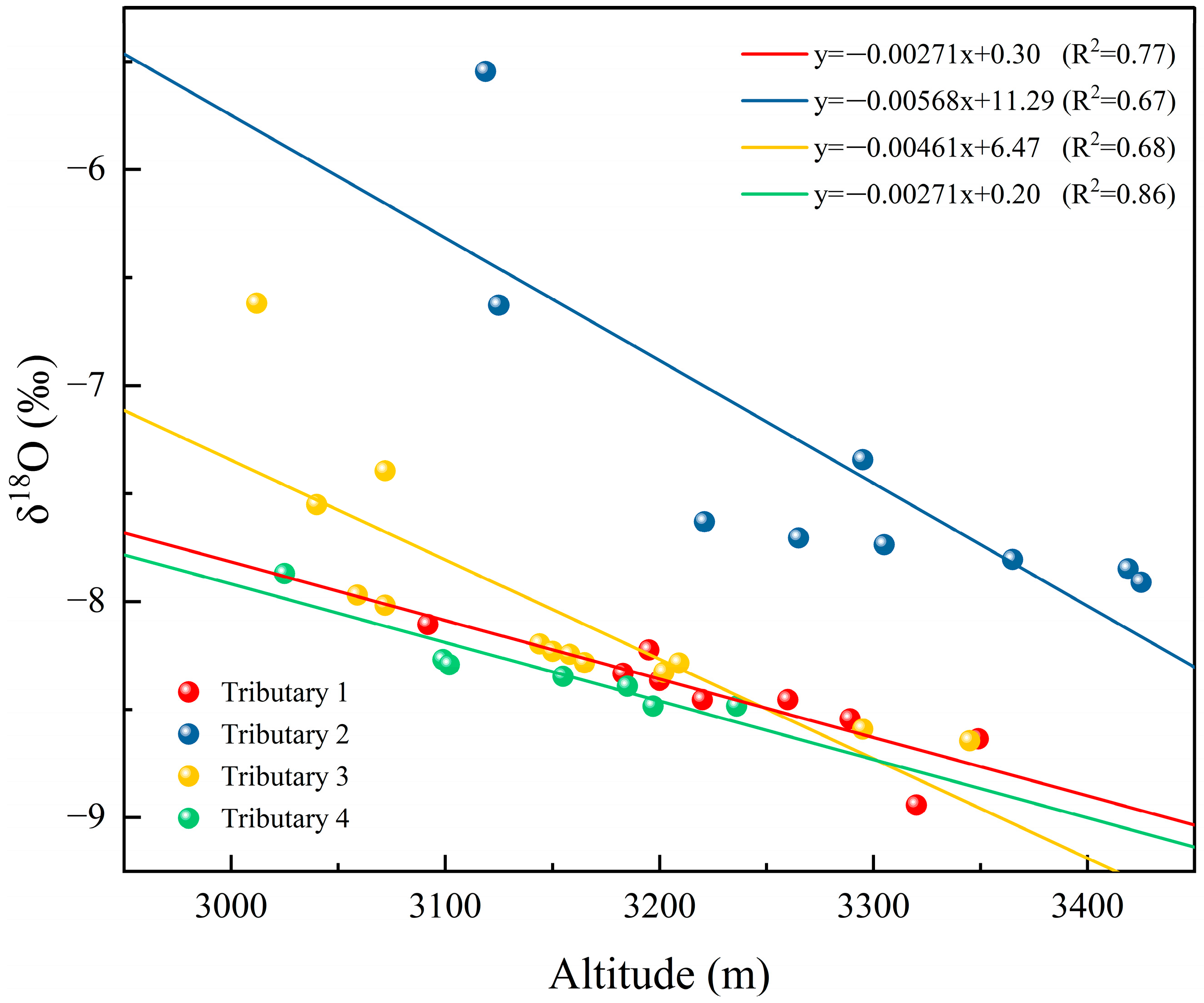

Figure 4 shows the trend of δ18O values in river water from the four tributaries as a function of altitude. The δ18O values of all tributaries decrease with increasing altitude. Specifically, as the altitude rises and temperatures drop, lighter isotopes are more likely to condense during the water vapor condensation process. As a result, river water in high-altitude areas typically has lower δ18O values, which aligns with the commonly observed altitude effect theory. Notably, Tributary 2 shows the most pronounced change in δ18O values with increasing altitude, with a slope of −0.00568 (R2 = 0.67), indicating that altitude has the strongest effect on its δ18O values.

Figure 4.

Fitting of the Relationship Between δ18O Values in River Water and Altitude for the Four Tributaries. Note: The method precision is as follows: δD (δ2H) ± 0.34‰, δ18O ± 0.05‰.

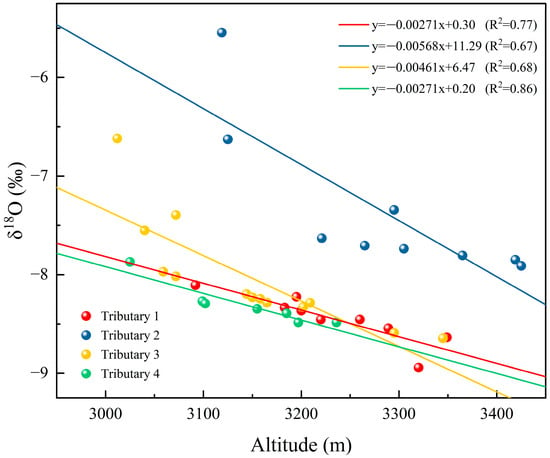

3.3. Oxygen Stable Isotope Characteristics of Groundwater

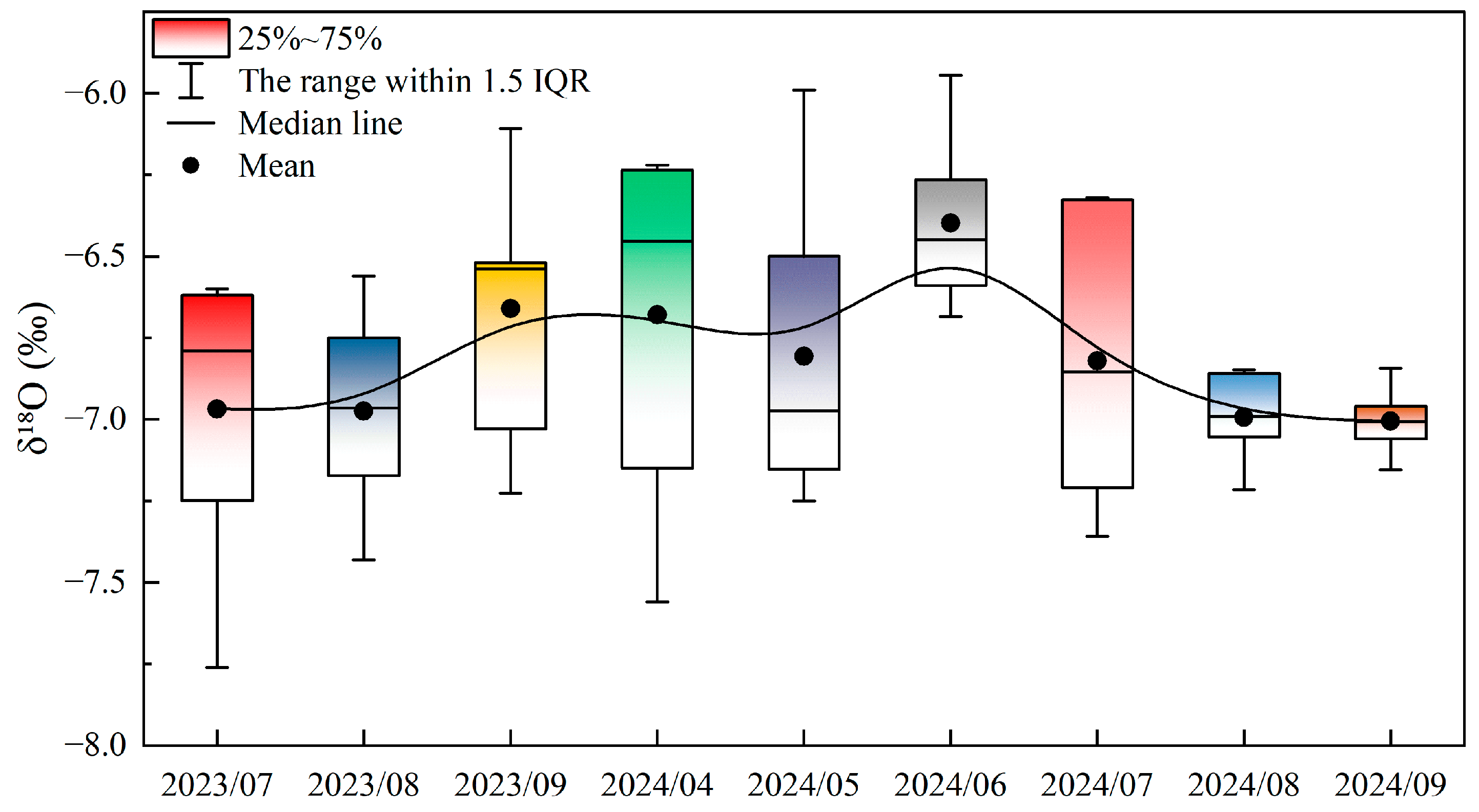

Based on the mean δ18O values of groundwater from July to September 2023 and April to September 2024, as shown in Figure 5, the groundwater isotopic values exhibit significant seasonal variation, reflecting the alternating effects of precipitation and evaporation processes.

Figure 5.

Temporal Variation Characteristics of Groundwater Stable Isotopes. Note: Figure 5 shows the temporal variation characteristics of groundwater δ18O data. The boxplots represent the distribution of data, where the boxes correspond to the interquartile range (IQR), covering the 25th to 75th percentiles. The whiskers extend to 1.5 times the IQR, indicating the range of values within this range. The black line inside the box represents the median value, and the black dots represent the mean value. The IQR reflects the variability of δ18O values, providing insight into the data distribution and central tendency. Different colors represent different months.

In July 2023, the mean δ18O value of groundwater was −7.03‰, with values of −7.02‰ in August and −6.69‰ in September. These data indicate that during the dry season, the evaporation effect gradually intensified, leading to the enrichment of groundwater isotopic values.

Entering 2024, the δ18O values of groundwater displayed an alternating trend of troughs and peaks. Starting from April 2024, the δ18O value was −6.50‰, relatively low, indicating that groundwater at this time was primarily influenced by precipitation recharge, with minimal evaporation effects. Subsequently, in May 2024, the δ18O value decreased to −6.76‰, reaching the annual trough, reflecting the dominance of precipitation recharge during this period.

In June 2024, the δ18O value of groundwater rose to −6.36‰, reaching a peak. This change can be attributed to two factors: Firstly, June marks the transition from spring to early summer, with rising temperatures leading to enhanced evaporation. Although precipitation continues to recharge the groundwater, the evaporation effect also begins to show. Secondly, June may be a critical period of alternating precipitation and evaporation effects, where evaporation causes lighter isotopes to evaporate, making the remaining water relatively enriched in heavier isotopes. As a result, the δ18O value in June is relatively high, reflecting an enriched state.

However, after June 2024, the δ18O values of groundwater continued to remain negative, with values of −6.83‰ in July, −6.98‰ in August, and −7.01‰ in September. This indicates that, although the evaporation effect persisted through the summer, the continued influence of precipitation recharge caused the isotopic values of groundwater to gradually become depleted. Particularly from July to September, while the intensity of evaporation remained high, the increasing precipitation and surface water recharge caused the groundwater to gradually revert to a negative enrichment state, highlighting the dominant role of precipitation in shaping the isotopic composition of water.

Overall, the δ18O values of groundwater in 2024 exhibited notable fluctuations, particularly from April to September, with alternating troughs (May 2024) and peaks (June 2024). The enriched state in June is closely related to the alternating effects of evaporation and precipitation recharge, while the continued depletion after June is primarily due to the dominant role of precipitation recharge during this phase. This variation allows us to gain a deeper understanding of groundwater source dynamics and its response to climate change.

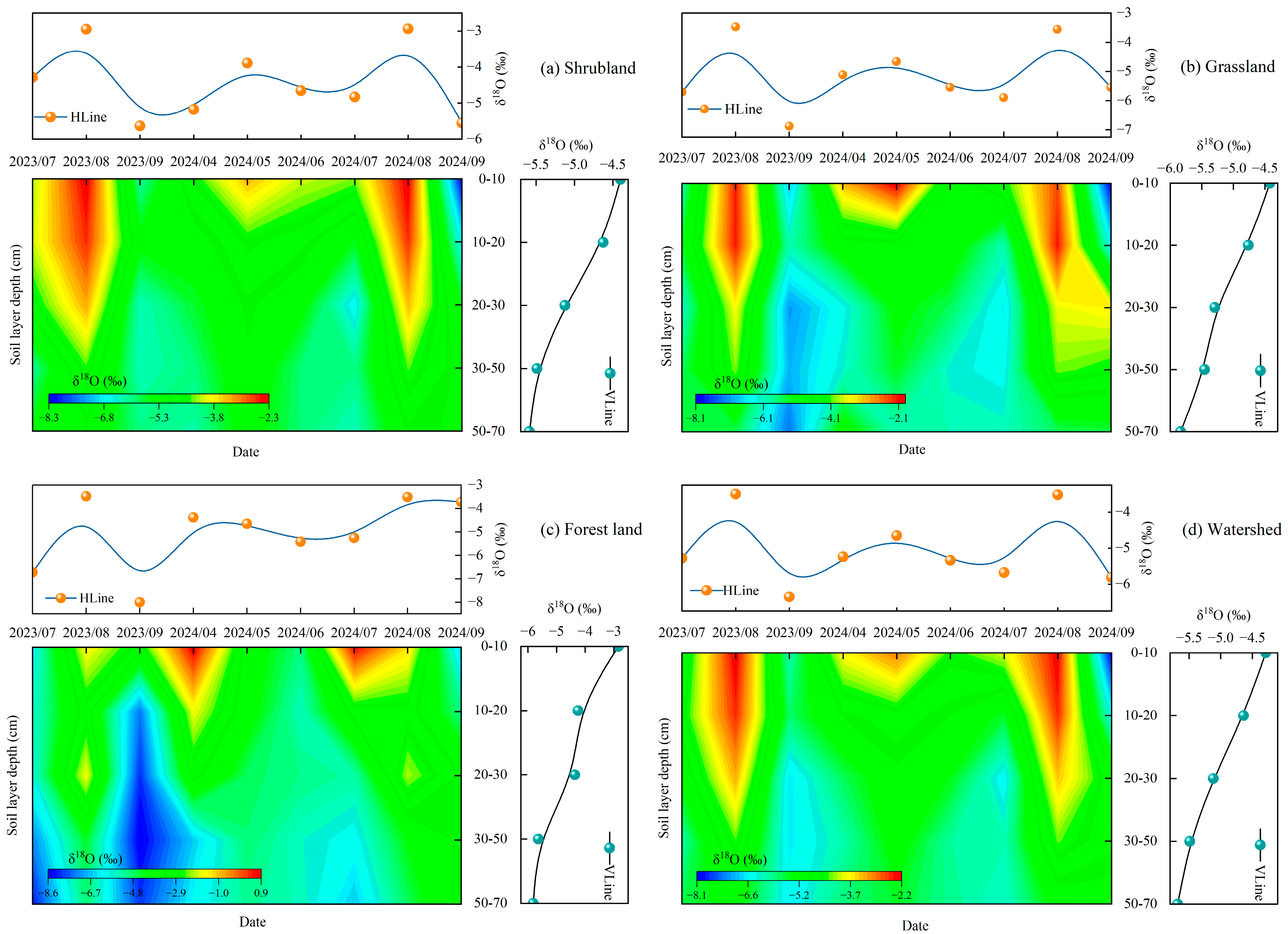

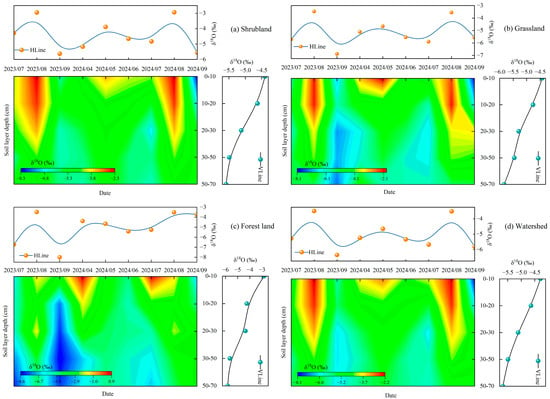

3.4. Oxygen Stable Isotope Characteristics of Soil Water

As shown in Figure 6, in the three types of ecosystems in the study area, the time-depth dynamics of soil water δ18O exhibit a consistent stratified pattern, while also showing varying degrees of change due to differences in vegetation types and root structures. The three ecosystems represent the typical vegetation types in the study area, namely shrubland, grassland, and forest. The surface soil water in all ecosystems is strongly influenced by seasonal changes, with significant δ18O enrichment peaks observed in August 2023 and August 2024, while spring and early autumn show more negative values, reflecting the alternating effects of precipitation recharge and evaporation. However, the response amplitude and depth transmission range to this seasonal signal vary significantly across different ecosystems (refer to Figure 6a–c).

Figure 6.

Time Variation Trend of δ18O Values in Soil Water at Different Soil Depths of Different Ecosystems. Note: (a) The shrubland ecosystem; (b) The grassland ecosystem; (c) The forest ecosystem; (d) Watershed scale. HLine represents the time-series data, while VLine represents the depth series data.

The selection of these three ecosystems is based on their distinct differences in hydrological characteristics and root structure. In the shrubland ecosystem (Figure 6a), soil water δ18O values exhibited significant seasonal fluctuations between July 2023 and September 2024, with a range from −5.63‰ to −2.93‰. The surface soil water (0–20 cm) δ18O values fluctuated in response to precipitation pulses and evaporation, with notable δ18O enrichment (close to −2.93‰) in August 2023 and August 2024, indicating an intensification of evaporation effects. The two-dimensional heatmap shows that the shrubland soil profile follows a typical “fast-changing surface layer–regulated middle layer–stable deep layer” pattern, with the surface layer undergoing rapid changes due to both precipitation and evaporation, while the fluctuation in the middle layer (20–40 cm) is smaller, reflecting the competition between precipitation infiltration and deep root water uptake. Below 40 cm, the deep soil water δ18O values remained stable and negative over the long term, forming the “old water reservoir” that helps shrubland plants maintain drought resistance.

In the grassland ecosystem (Figure 6b), soil water δ18O values fluctuated between −6.88‰ and −3.47‰ from July 2023 to September 2024. The surface soil water (0–20 cm) δ18O values were highly variable, influenced by the alternating effects of precipitation and evaporation. In particular, δ18O values reached −3.47‰ in August 2023 and −3.2‰ in August 2024, indicating enhanced evaporation effects. In spring (April to June), δ18O values were more negative, reflecting the dominant effect of precipitation recharge. As the depth increased (20–40 cm, below 40 cm), the δ18O values became more stable with reduced fluctuation. The δ18O values in the 20–40 cm layer ranged from −5.84‰ to −5.0‰, and in the deep layers below 40 cm, they remained stable between −5.82‰ and −6.0‰, indicating that the deep water in the grassland ecosystem renews more slowly and responds less to seasonal changes.

In the forest ecosystem (Figure 6c), soil water δ18O values ranged from −7.00‰ to −3.06‰ between July 2023 and September 2024. The surface soil water (0–20 cm) δ18O values showed considerable seasonal variation, with δ18O enrichment peaks occurring in the spring and autumn. During the summer and early autumn, δ18O values gradually became enriched. In the spring of 2024, δ18O values were more negative, reflecting the dominant influence of precipitation recharge. With increasing soil depth, the fluctuation of δ18O values gradually decreased, and the 20–40 cm middle layer showed smaller fluctuations, reflecting the interaction between precipitation infiltration and plant root water uptake. Below 40 cm, deep soil water δ18O values remained stable and negative over the long term, ranging from −5.82‰ to −2.84‰, indicating slower deep water renewal and minimal response to seasonal changes. The stable δ18O values in the deep soil water in the forest ecosystem suggest a strong water buffering capacity, providing sustained water support to plants, especially during dry seasons.

At the watershed scale, the soil water structure characteristics of the three ecosystems were consistent: surface soil water strongly responds to precipitation and evaporation, the middle layer serves as a water regulation zone with weaker but identifiable seasonal signals, and deep soil water remains stable over time, forming a regional background water storage layer. The main differences among the three ecosystems lie in the amplitude of profile changes and the role of each layer: grasslands show the most sensitive shallow fluctuations, shrublands depend on deep layers, and forests have middle-layer regulation. Overall, the spatiotemporal pattern of regional soil water δ18O reflects the core mechanism controlled by “precipitation pulses–evaporation enrichment–slow deep renewal” in cold arid regions, while also reflecting the differences in the ability of different vegetation types to regulate soil moisture through their root structures and surface features.

4. Discussion

4.1. Isotopic Characteristics Analysis: Seasonal Variation and Water Source Renewal in Different Water Bodies

In this study, we analyzed the stable hydrogen and oxygen isotope characteristics (δ18O, δD, and deuterium excess values) of different water bodies to reveal the differences in water source renewal and seasonal variation. The δ18O values of precipitation, as shown in Table 1, ranged from −12.85‰ to −1.14‰, showing significant seasonal fluctuations. Given the significant variation in δ18O values across different elevations, it is more appropriate to consider the spatial distribution of these values rather than reporting a single average value. In particular, during the dry season, evaporation was prominent, leading to enrichment of δ18O, reflecting the enhancement of vapor sources and evaporation effects. Li Q et al. [19], in their study on precipitation characteristics in the Tibetan Plateau, also found that δ18O values were significantly affected by vapor sources and evaporation effects, which is consistent with the results of this study.

Table 1.

Stable Hydrogen and Oxygen Isotope Ratios and d-excess Values of Water Bodies in the Ami Dongsou Small Watershed.

Compared to precipitation, the δ18O values of river water showed smaller variation, ranging from −10.02‰ to −3.20‰, with an average of −7.97‰. This result indicates that the seasonal fluctuation of river water is weaker, primarily influenced by both precipitation recharge and evaporation. The deuterium excess value of river water was 17.97‰, indicating that evaporation effects were more significant in summer and autumn, particularly during the dry season, where enhanced evaporation led to the enrichment of δ18O and δD. Zou Y et al. [20] also found a significant evaporation enrichment effect in river water isotopic characteristics in arid regions, further supporting the findings of this study.

The isotopic characteristics of groundwater showed more stability, with δ18O values ranging from −7.76‰ to −5.94‰, and an average of −6.80‰, showing minimal variation. This indicates that the groundwater renewal process is slower and less affected by seasonal changes. The deuterium excess value of groundwater was 14.93‰, reflecting that groundwater is less influenced by evaporation and is mainly replenished by hydrological processes. Juan C et al. [21] also pointed out that groundwater exhibits smaller isotopic fluctuations, indicating a more stable water source renewal process.

Soil water exhibited more significant seasonal fluctuations, with δ18O values ranging from −7.33‰ to −3.58‰, and an average of −4.70‰. Particularly in the surface soil water (0–20 cm), δ18O values were significantly influenced by the alternating effects of precipitation and evaporation. In the summer, evaporation effects were pronounced, leading to enrichment of δ18O. The deuterium excess value of soil water was 3.53‰, further indicating that evaporation effects were particularly significant in the high-temperature season. Yong L et al. [11] also found that in cold, arid regions, the isotopic characteristics of soil water were significantly affected by the evaporation enrichment effect.

Overall, the isotopic characteristics of water bodies were highly consistent with previous studies, especially regarding seasonal changes and evaporation effects in precipitation, river water, and soil water [11,19,20]. By comparing the δ18O, δD, and deuterium excess values of different water bodies, we found that soil water and river water responded most significantly to evaporation, especially during the high-temperature season when evaporation effects were intensified. In contrast, the isotopic characteristics of groundwater were more stable and less affected by seasonal changes. These results further validate the important role of alternating evaporation and precipitation recharge in controlling the isotopic variation in water bodies in cold, arid regions.

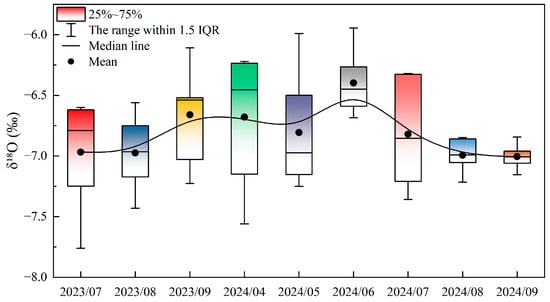

4.2. Evaporation Line Characteristic Analysis

The isotopic characteristics of water bodies are significantly influenced by environmental factors, particularly the enrichment effect of evaporation on water isotopes. The evaporation line reveals the impact of isotope fractionation during evaporation, helping to understand water sources, evaporation intensity, and the influence of climate change on the hydrological cycle [6,22]. Based on the δ18O and δD values of precipitation, groundwater, and river water, the evaporation trend line was fitted as follows: y = 4.97x − 7.30 (n = 504, R2 = 0.85). The study found that evaporation lines for different water bodies have different slopes, indicating that changes in water body isotopic characteristics are closely related to evaporation. The specific evaporation line equations are as follows: River water: y = 4.97x − 7.30 (n = 360, R2 = 0.71); Groundwater: y = 3.86x − 14.42 (n = 45, R2 = 0.71).

Figure 7 shows that there are significant differences in the slopes of the evaporation lines for different water bodies in the watershed. The evaporation line slope for precipitation (6.04) is the largest, indicating that evaporation has a greater impact on the isotopic characteristics of precipitation, especially during the dry season, where enhanced evaporation leads to the enrichment of δ18O and δD. Previous studies have pointed out that the isotopic characteristics of water bodies in arid regions are significantly influenced by evaporation, with a strong evaporation enrichment effect [23,24]. The evaporation line slope for river water (4.97) is smaller, reflecting a more moderate influence of evaporation on river water isotopes. Although river water is influenced by precipitation recharge, evaporation still has a significant effect [25,26]. In summer and autumn, the enhanced evaporation leads to isotopic enrichment in river water, particularly in the Ami Dongso watershed, where river water levels fluctuate greatly in the dry season, and evaporation effects are more pronounced.

Figure 7.

Relationship Between δ18O and δD of Different Water Bodies and Evaporation Trend Lines. Note: Method precision is as follows: δD (δ2H) ± 0.34‰, δ18O ± 0.05‰.

The evaporation line slope for groundwater (3.86) is the smallest, indicating that groundwater is less affected by evaporation and is primarily controlled by deep recharge processes. Therefore, the isotopic characteristics of groundwater remain relatively stable [27]. Other studies have found that the groundwater renewal rate in the watershed is slow, mainly depending on seasonal precipitation and mountain infiltration recharge, with minimal influence from evaporation on groundwater [20,28].

By comparing the evaporation line characteristics of different water bodies, this study found that the intensity of the evaporation effect on water bodies follows the order precipitation > river water > groundwater. This indicates that evaporation plays a multi-level role in the hydrological cycle, especially during the dry season or in high-temperature environments, where the enrichment effects on water body isotopic characteristics are more significant. The δ18O and δD values of river water and precipitation are significantly affected by evaporation, particularly in the summer and dry seasons, where evaporation is enhanced and the isotopic concentration effect in water bodies is more pronounced. In contrast, groundwater remains relatively stable, indicating that its isotopic characteristics are less affected by seasonal changes and evaporation.

Figure 7 shows the differences in the range of isotopic variations among precipitation, river water, and groundwater. Precipitation exhibits the largest variation in isotopic values, primarily influenced by seasonal and climatic changes, reflecting the significant fluctuations between evaporation and direct precipitation inputs. Particularly during dry seasons, the enhanced evaporation effect leads to the volatilization of lighter isotopes in precipitation, causing enrichment in δ18O and δD values. In contrast, river water shows smaller variations, mainly regulated by watershed hydrological processes, such as precipitation recharge and groundwater input, resulting in relatively stable isotopic changes with smaller fluctuations. Groundwater displays the smallest variations in isotopic values, primarily controlled by deep recharge processes, with a slower renewal rate, which reduces its response to seasonal changes. As a result, groundwater isotopic characteristics remain relatively stable, with minimal fluctuation. The differences in water storage capacity are key to explaining these variations in range. The differences in the roles of precipitation, river water, and groundwater in the hydrological cycle, as well as their isotopic characteristics, highlight their distinct roles in water source recharge and evaporation processes.

Additionally, the climate conditions and topographic features of the watershed, especially the influence of high-altitude areas and the dry season [29,30], play a significant role in regulating the isotopic characteristics of water bodies. The mountainous terrain and monsoon effects lead to more pronounced local climate variations, especially in high-altitude regions, where the isotopic values of precipitation and river water are significantly enriched, reflecting the dominant role of evaporation effects and local climate conditions. Our results are consistent with studies in the Tibetan Plateau region [31,32], where it was also found that the mountainous terrain and monsoon influence led to more pronounced local climate changes, especially in high-altitude areas. The isotopic values of precipitation and river water were significantly enriched, reflecting the dominant role of evaporation effects and local climate conditions.

4.3. Role of Hydrodynamics in Regulating Water Body Isotopic Characteristics

In the Ami Dongsou small watershed, water source recharge significantly influences the spatial and temporal distribution of water isotopic characteristics, particularly during the dry season. Seasonal fluctuations in the isotopic characteristics of precipitation, along with enrichment during the dry season, indicate the dominant role of evaporation in precipitation. Hydrological dynamics, especially the evaporation process, play a crucial role in regulating the isotopic characteristics of precipitation, soil water, and river water. During the dry season, high temperatures and enhanced evaporation conditions lead to more significant isotopic concentration effects, particularly in soil water and river water, where δ18O values are enriched [11,33]. These phenomena provide important insights for understanding the hydrological cycle and managing watershed water resources, especially as evaporation increases the risk of water shortages during dry seasons.

In contrast to precipitation and river water, groundwater exhibits more stable isotopic characteristics with smaller variations, and is less influenced by seasonal changes, reflecting the dominance of deep hydrological processes. The stability of groundwater highlights its importance as a water source during dry seasons and high temperatures, especially when other water sources (such as river water and soil water) become concentrated due to evaporation effects [33,34]. This demonstrates that groundwater has a stronger buffering capacity compared to other water bodies, particularly under climate change and seasonal fluctuations.

Based on these findings, it is recommended to strengthen the monitoring and protection of groundwater resources, rationally utilize groundwater, avoid over-extraction, and explore sustainable groundwater recharge management strategies. Hydrological dynamics, particularly the alternating effects of evaporation and water source recharge, must be considered key factors in water resource management, especially during dry seasons and hot environments.

The impact of hydrological dynamics on water isotopic characteristics, as revealed in this study, not only enhances our understanding of water cycles in high-altitude arid regions but also provides data support for addressing climate change, improving water resource management, and optimizing hydrological prediction models. Real-time monitoring of isotopic data can provide early warnings for the sustainable management of watershed water resources, ensuring the effective allocation of water resources, particularly during dry seasons and high-temperature environments.

5. Conclusions

5.1. Significant Seasonal Variation in Water Body Isotopic Characteristics and Differences in “Fast–Slow” Water Source Renewal

This study, based on stable hydrogen and oxygen isotope observations of multiple water bodies (precipitation, river water, soil water, and groundwater) in the Ami Dongsou alpine arid small watershed during 2023–2024, reveals significant seasonal fluctuations in water body isotopic characteristics. Precipitation and soil water exhibit notable enrichment during the dry season, indicating that evaporation plays a dominant role in determining the isotopic characteristics of water bodies. River water also responds to seasonal changes, but the response is more controlled by both recharge and evaporation processes. In contrast, groundwater isotopes show the most stable changes, reflecting a slower recharge process with a noticeable lag. The contrast between the “fast response of surface water bodies and slow response of groundwater” provides valuable evidence for understanding water source renewal dynamics in cold arid small watersheds, filling a gap in isotopic research on the collaborative evolution of multiple water bodies at the small watershed scale.

5.2. Evaporation Dominates Isotopic Enrichment, and Its Differential Response Is Quantified Through Evaporation Line Parameters

Evaporation is a key process controlling the isotopic enrichment of water bodies, especially during high-temperature and dry seasons, when isotopic enrichment in precipitation, river water, and surface soil water is more pronounced. By fitting the evaporation line slopes and intercepts, this study quantifies the intensity of evaporation’s impact on different water bodies: precipitation is most sensitive to evaporation (with the steepest slope), river water exhibits a “recharge–evaporation superimposed” response, and groundwater has the smallest slope, reflecting its dominant control by deep recharge with limited influence from evaporation. Consistent with existing studies on the Tibetan Plateau and similar high-altitude arid regions [23,35], this study further clarifies the hierarchical pattern of “evaporation-dominated differential water body response” at the small watershed scale, providing a basis for incorporating isotopic data into hydrological process assessments and model parameterization.

5.3. High-Altitude Climate–Topography–Vapor Source Synergy Regulates Isotopic Signals, Enhancing Process Understanding in Cold Arid Regions

This study shows that climate conditions and topographical features in high-altitude areas significantly regulate water body isotopic signals. During winter and spring, lower δ18O values of precipitation indicate the influence of cold vapor sources and low-temperature fractionation effects. In contrast, at higher altitudes and during the dry season, enhanced evaporation further amplifies isotopic enrichment characteristics in water bodies. This result highlights the mechanism by which local climate, topography, and vapor sources jointly shape isotopic signals, providing more comprehensive evidence for understanding the “vapor source—evaporation—recharge” processes that control water body isotopic characteristics in cold, arid mountainous regions.

5.4. Innovation and Practical Application Prospects

The innovation of this study lies in its focus on the small watershed scale, where it integrates the isotopic processes of precipitation, river water, soil water, and groundwater. By quantitatively comparing evaporation effects using evaporation line parameters, the study reveals the integrated mechanism of “seasonal strong fluctuations + differential water body responses + high-altitude regulation” in water body isotopes within cold arid regions, deepening our understanding of the combined impacts of local climate, topography, and hydrological processes.

In relation to objectives (2) and (3), we successfully conducted a quantitative analysis of isotopic variations across different water bodies and uncovered the alternating effects of water source recharge, evaporation, and hydrological dynamics. Despite some limitations, such as the sample size and monitoring period, the study provides valuable data to support future water resource management and ecological protection, particularly in optimizing water resource allocation during dry seasons and high-temperature environments.

The practical benefits of this study are significant for water resource management in cold arid regions. By revealing the interactions between evaporation and water source recharge in different water bodies, this study can guide the rational allocation of water resources, especially during dry seasons. Future research can expand the sample size, extend the monitoring period, and incorporate more multi-source data and hydrological models, further improving the accuracy of hydrological process predictions and providing more precise support for watershed water resource management and ecological protection.

Author Contributions

Q.H.: Conceptualization, Investigation, Data curation, Methodology, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing, Visualization, Validation. G.C.: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Writing—review & editing. G.H.: Supervision, Validation, Writing—review & editing. M.Z., J.B. and W.Y.: Investigation. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the “Kunlun Elite High-Level Innovation and Entrepreneurship Talents” Cultivation Program for Outstanding Talents of Qinghai Province [Qing Rencai Zi (2023) No.1] and the Major Special Projects of Qinghai Science and Technology Department [Grant No. 2021-SF-A7-1].

Data Availability Statement

The data sets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to the unique geographical characteristics and protected status of the Qilian Mountain National Park. As the study area is located within a protected region, some of the raw field data are subject to confidentiality and cannot be made publicly accessible at this time. We acknowledge the scientific value of data sharing and are willing to provide relevant data upon reasonable request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We sincerely thank our teachers for their expert guidance, critical feedback, and unwavering supervision throughout this research. Their insights and dedication were instrumental in shaping this work. We also extend our gratitude to our classmates for their collaborative support, stimulating discussions, and encouragement during the project. Their contributions created a nurturing academic environment that greatly aided this endeavor.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Wu, X.; Pan, M.; Yin, J.; Cao, J. Hydrogen and oxygen isotope signal transmission in rainfall, soil water, and cave drip water in Liang feng Cave, Southwest China. Appl. Geochem. 2023, 158, 105798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coplen, T. Stable Isotope Hydrology: Deuterium and Oxygen-18 in the Water Cycle. Eos Trans. Am. Geophys. Union 1982, 63, 861–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Li, X.; Deng, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, X. Stable isotope evidence confirms lakes are more sensitive than rivers to extreme drought on the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau, China. J. Hydrol. 2023, 627, 130466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, S.N.; Novakowski, K.S. Groundwater recharge, flow and stable isotope attenuation in sedimentary and crystalline fractured rocks: Spatiotemporal monitoring from multi-level Wells. J. Hydrol. 2019, 571, 178–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vystavna, Y.; Schmidt, S.I.; Diadin, D.; Rossi, P.M.; Vergeles, Y.; Erostate, M.; Yermakovych, I.; Yakovlev, V.; Knoller, K.; Vadillo, I. Multi-tracing of recharge seasonality and contamination in groundwater: A tool for urban water resource Management. Water Res. 2019, 161, 413–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, C.; Li, X.; Cheng, X.; Liu, C.; Bai, Z.; Li, J. Hydrochemical processes and water balance trends based on stable isotopes of typical alpine lakes in the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. J. Geochem. Explor. 2025, 270, 107663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Tian, L.; Tian, H. Stable isotope tracing the transformation dynamics of diverse water bodies in the Manas River Basin, Northwest China. Appl. Water Sci. 2025, 15, 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Xiao, H.; Qin, Z.; Zou, S. Hydrogen and oxygen isotopic records in monthly scales variations of hydrological characteristics in the different landscape zones of alpine cold Regions. J. Hydrol. 2013, 499, 124–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, S.; Zeng, C.; Zhang, F.; Wang, G.; Xiao, X. Defining lateral subsurface flow and identifying its water sources in an Alpine-permafrost Hillslope. CATENA 2024, 236, 107765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baijuan, Z.; Zongxing, L.; Qi, F.; Zhang, B.; Gui, J. A review of isotope ecohydrology in the cold regions of Western China. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 857, 159438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valdivielso, S.; Vázquez-Suñé, E.; Custodio, E. Origin and variability of oxygen and hydrogen isotopic composition of precipitation in the Central Andes: A Review. J. Hydrol. 2020, 587, 124899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, S.; Li, F.; Li, Y.; Gu, C.; Zhang, Q.; Qiao, Y.; Jiao, L.; Zhu, N. Stable isotope evidence for identifying the recharge mechanisms of precipitation, surface water, and groundwater in the Ebinur Lake Basin. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 657, 1041–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vreča, P.; Kern, Z. Use of Water Isotopes in Hydrological Processes. Water 2020, 12, 2227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.; Zhu, G.; Zhang, Z.; Xu, Y.; Yong, L.; Wan, Q.; Ma, H.; Sang, L.; Liu, Y. Identifying Surface Water Evaporation Loss of Inland River Basin Based on Evaporation Enrichment Model. Hydrol. Process. 2021, 35, e14093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuo, Z. A Study on the Characteristics of Carbon Sources/Sinks and Factors Influencing Carbon Pools in the Ecosystem on the Southern Slope of the Qilian Mountains; Tongfang Knowledge Network Technology Co., Ltd.: Beijing, China, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meiliang, Z. Simulation Study on Runoff Generation Patterns and Hydrological Processes in the Babao River Basin of the Qilian Mountains; Qinghai Normal University: Xining, China, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shuhui, Z.; Fagao, H.; Baoling, N. Study on the hydrogen and oxygen stable iso⁃topes in meteoric precipitation of China. Chin. Sci. Bull. 1983, 28, 801–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craig, H. Isotopic Variations in Meteoric Waters. Science 1961, 133, 1702–1703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Q.; Jiao, L.; Xue, R.; Che, X.; Zhang, P.; Wang, X.; Yuan, X. Seasonal and Depth Dynamics of Soil Moisture Affect Trees on the Tibetan Plateau. Forests 2024, 15, 752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, Y.; Zhang, S.; Yu, X.; Fu, G.; Lu, X. Isotopic evidence for soil water sources and reciprocal movement in a Semi-arid degraded wetland: Implications for wetland Restoration. Fundam. Res. 2023, 3, 861–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juan, C.; Fang-yuan, Z.; Gen-xu, W.; Jian, L. Spatiotemporal heterogeneity of suprapermafrost groundwater dynamic processes in the permafrost region of the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. CATENA 2024, 239, 107911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Du, R.; Cao, X.; Yu, H.; Xu, Y.; Yu, Y.; Peng, J. Evaporation dominates the loss of plateau lake in Southwest China using water isotope balance Assessment. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 873, 162415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yong, L.; Zhu, G.; Wan, Q.; Xu, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Sun, Z.; Ma, H.; Sang, L.; Liu, Y.; Guo, H.; et al. The Soil Water Evaporation Process from Mountains Based on the Stable Isotope Composition in a Headwater Basin and Northwest China. Water 2020, 12, 2711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gat, J.R. Stable isotopes, the hydrological cycle and the terrestrial Biosphere. In Stable Isotopes; Garland Science: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 397–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.; Hao, S.; Li, F.; Li, G.; Ji, D. Tracking seasonal evaporation of arid Ebinur Lake, NW China: Isotopic Evidence. Environ. Earth Sci. 2024, 83, 543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.; Meng, Y.; Liu, G.; Xia, C.; Zhou, J.; Li, H. Identifying hydrological conditions of the Pihe River catchment in the Chengdu Plain based on Spatio-temporal distribution of 2H and 18O. J. Radioanal. Nucl. Chem. 2020, 324, 1125–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jørgensen, N.; Banoeng-Yakubo, B. Environmental isotopes (18O, 2H, and 87 Sr/86 Sr) as a tool in groundwater investigations in the Keta Basin, Ghana. Hydrogeol. J. 2001, 9, 190–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berghuijs, W.R.; Collenteur, R.A.; Jasechko, S.; Jaramillo, F.; Luijendijk, E.; Moeck, C.; van der Velde, Y.; Allen, S. Groundwater recharge is sensitive to changing Long-term Aridity. Nat. Clim. Change 2024, 14, 357–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, L.; Wang, L.; Luo, D.; Chen, D.; Zhou, J. Assessing hydrothermal changes in the upper Yellow River Basin amidst permafrost Degradation. Npj Clim. Atmos. Sci. 2024, 7, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, X.; Zhu, G.; Qiu, D.; Ye, L.; Liu, Y.; Jiao, Y.; Wang, L.; Zhao, K.; Zhang, W.; Liu, J.; et al. Climate and landscape control of runoff stable isotopes in the inland Mountain. J. Hydrol. Reg. Stud. 2024, 51, 101633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, M.; Chen, X.; Wang, J.; Soulsby, C.; Cheng, Q. Climate and landscape controls on Spatio-temporal patterns of stream water stable isotopes in a large glacierized mountain basin on the Tibetan Plateau. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 771, 144799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juan, G.; Li, Z.; Qi, F.; Ruifeng, Y.; Tingting, N.; Baijuan, Z.; Jian, X.; Wende, G.; Fusen, N.; Weixuan, D.; et al. Environmental effect and spatiotemporal pattern of stable isotopes in precipitation on the transition zone between the Tibetan Plateau and arid Region. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 749, 141559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Lin, J.; Gu, W.; Min, X.; Han, J.; Dai, Y.; Liu, P.; Wang, S. Analysis and evaluation of the renewability of the deep groundwater in the Huaihe River Basin, China. Environ. Earth Sci. 2021, 80, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tangarife-Escobar, A.; Koeniger, P.; López-Moreno, J.I.; Botia, S.; Ceballos-Lievano, J. Spatiotemporal variability of stable isotopes in precipitation and stream water in a high elevation tropical catchment in the Central Andes of Colombia. Hydrol. Process. 2023, 37, e14873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Xiao, T.; Jia, L.; Han, L. Spatiotemporal Distribution Characteristics of Actual Evapotranspiration in the Qinghai–Tibet Plateau. Atmosphere 2023, 14, 1360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.