Abstract

Recurrent flooding poses a persistent and growing threat to West African watersheds facing rapid urbanization and climate change. Despite advances in machine learning and geospatial datasets, urban planning and flood prevention often rely on limited datasets and traditional analysis. This study addresses this research gap in the Bonoumin-Palmeraie watershed (Abidjan, Côte d’Ivoire) by developing an integrated approach leveraging remote sensing, Geographic Information Systems (GIS), and the Random Forest algorithm to assess and map flood susceptibility. Twelve conditioning factors related to topography, hydrology, land use, and climate were derived from Sentinel-1, ALOS PALSAR, and multi-source earth observation datasets. Historical flood extents were mapped in Google Earth Engine to train the Random Forest model in a Google Colab environment. The model demonstrated high discriminatory power, yielding an Area Under the Curve of 0.94 and Overall Accuracy of 0.83. Drainage density, rainfall, and altitude were identified as the primary explanatory drivers. The resulting flood susceptibility map indicates that 39% of the watershed exhibits medium to very high susceptibility, with critical hotspots in the neighborhoods of Palmeraie, Attoban, Akouedo, Djorogobité, and Riviera-Sogefiha. While limited by the exclusion of certain anthropogenic variables and ground truth constraints, the study provides a reproducible, data-driven framework for flood risk assessment in tropical urban environments. These findings offer essential scientific support for urban planners and decision-makers to enhance territorial planning and sustainable flood management in Abidjan.

1. Introduction

Flooding is among the most devastating natural disasters worldwide, accounting for nearly half of all recorded disaster events [1,2,3,4,5]. In Africa, particularly within the Sahelian region, floods result in substantial human casualties and socio-economic losses [6]. West Africa is exceptionally vulnerable to the effects of climate change, facing unprecedented temperature variations and the intensification of extreme rainfall patterns that lead to increasingly severe disasters. In Côte d’Ivoire, specifically in the Abidjan district, extreme rainfall in 2022 led to 25 fatalities and over 350 injuries, as reported by the Office National de la Protection Civile (ONPC). The Bonoumin-Palmeraie watershed, located in the Cocody commune, is highly susceptible to recurrent flooding during the rainy season [7,8]. Given the increasing frequency and severity of these events, an in-depth study of the phenomenon is imperative [9,10,11]. Effective flood risk assessment is critical for disaster management, urban planning, and policy formulation [12].

Recent advancements in Artificial Intelligence (AI) and remote sensing technologies have transformed flood susceptibility assessments by enabling high-precision predictions and near real-time monitoring [13,14,15]. Flood prediction models have evolved significantly with the integration of machine learning (ML) frameworks, capable of processing vast datasets to improve predictive accuracy [16,17]. For instance, Random Forest and boosted-tree models have shown superior performance in identifying flood-prone areas [18,19]. The application of ML algorithms, particularly hybrid models, also enhanced the precision of flood forecasting systems [20]. Furthermore, high-spatial-and-temporal-resolution geospatial data has helped capture local flood dynamics, ensuring a more comprehensive understanding of flood susceptibility [21,22,23]. Remote sensing data such as Sentinel and ALOS PALSAR, when combined with AI techniques, further enhances flood susceptibility assessments by automating large-scale data analysis [24,25] and leveraging diverse spatial datasets to identify critical flood drivers such as slope, drainage density, etc. [18].

Though several AI algorithms, including Random Forest and ensemble models, have demonstrated superior accuracy in predicting flood-prone areas [26], many studies still rely on traditional multi-criteria approaches. Techniques such as the Analytical Hierarchy Process (AHP) with the integration of remote sensing, GIS, and multi-criteria decision analysis have helped refine flood risk assessments by considering multiple hydrological and topographic factors [27]. Other studies have emphasized the role of geomorphology in flood modeling, highlighting the importance of incorporating spatial, anthropic and environmental data for comprehensive flood risk management [28,29]. These conventional methods yield significant advances in flood risk assessment, without leveraging AI [30], but possess inherent limitations relating to their accuracy and scalability [31]. Firstly, traditional models struggle to integrate large, high-resolution datasets. Secondly, conventional techniques such as AHP or empirical indices often rely on subjective weight assignments, introducing biases and reducing predictive robustness. Moreover, these models fail to capture the complex, non-linear relationships between flood-influencing factors, such as topography, hydrology, precipitation, and land use.

In this context, our study provides an innovative and operational contribution to flood risk management in tropical urban environments. Moving beyond conventional approaches, we combine machine learning (Random Forest) with multi-sensor data, integrating CHIRPS rainfall series, Sentinel-1 radar imagery, Sentinel-2 multispectral imagery, and ALOS PALSAR digital elevation models. This approach simultaneously links the primary drivers of flooding (precipitation) with their observed spatial effects (flooded areas), while accounting for physical factors influencing flood susceptibility, such as slope, drainage density, and land use.

The primary objective of this research is to identify and map flood-prone areas within the Bonoumin–Palmeraie watershed in Abidjan, using an integrated machine learning and Earth observation framework. This study not only advances the understanding of urban flood dynamics in Abidjan, but also provides a robust, data-driven foundation for proactive urban planning and disaster risk reduction.

2. Study Area

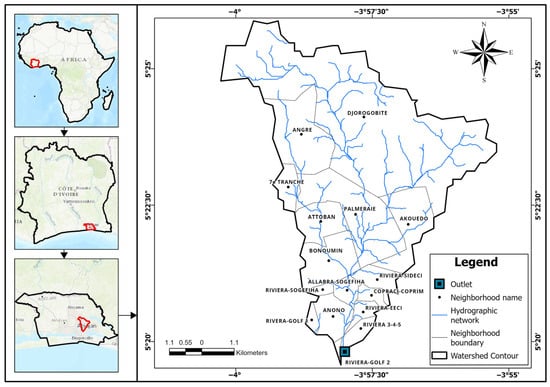

The Bonoumin-Palmeraie watershed (Figure 1) is located in the commune of Cocody, within the Autonomous District of Abidjan, Côte d’Ivoire. It extends between longitudes 3°50′ and 4°10′ West and latitudes 5°10′ and 5°30′ North, encompassing key urban districts such as Bonoumin, Palmeraie, Allabra, and Riviera 2. The watershed features a complex hydrographic network consisting mainly of small, intermittent streams that converge to form stagnant water bodies before eventually draining toward the main outlet during the rainy season. This hydrological behavior, coupled with the area’s irregular topography, makes the watershed particularly prone to flooding. Urbanization has significantly altered the watershed’s natural drainage patterns. The increasing impermeability of surfaces due to rapid infrastructure expansion has led to higher surface runoff, thereby reducing groundwater infiltration and exacerbating flood risks. During intense precipitation events, the natural drainage capacity is exceeded, leading to severe flooding that affects local ecosystems and communities. These hydrological and climatic dynamics underscore the urgency of developing data-driven flood risk assessments to support sustainable urban planning and disaster mitigation strategies in the Bonoumin-Palmeraie watershed.

Figure 1.

Location of the Bonoumin-Palmeraie watershed.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Data Used

3.1.1. Remote Sensing and Geospatial Data

This study integrates a set of geospatial, climate, and land-use data to analyze flood dynamics in the Bonoumin-Palmeraie watershed (Table 1). These datasets were selected for their ability to represent the physical and environmental factors influencing flood occurrence, through a Random Forest AI-based approach.

Table 1.

Overview of Remote Sensing and Geospatial Data used in the Study.

- Sentinel-1 Synthetic Aperture Radar (SAR) images from the COPERNICUS/S1 collection were employed to analyze land surface characteristics and detect flood-prone areas. With a spatial resolution of 10 m and vertical-horizontal (VH) polarization, these images are highly effective for flood mapping, particularly in areas with frequent cloud cover.

- Sentinel-2A optical images, with a 10-m spatial resolution, were used to generate a detailed land use and land cover (LULC) map of the watershed for March 2023. This dataset provided crucial information on impervious surfaces, vegetation cover, and water bodies, all of which significantly influence flood susceptibility.

- ALOS PALSAR Digital Elevation Model (DEM) data, with a 12.5 m spatial resolution, facilitated the calculation of hydrological and geomorphological indices, including elevation, slope, drainage density, and the Topographic Wetness Index (TWI), all of which play a key role in flood dynamics.

- Climate data were obtained from the Climate Hazards Group InfraRed Precipitation with Station data (CHIRPS) database. These gridded precipitation datasets have a 0.05° spatial resolution and cover a period exceeding 35 years (1981–2024). Integration with in-situ meteorological records allowed for the reconstruction of high-resolution precipitation time series, essential for evaluating historical flood events and seasonal rainfall variability.

- Permanent surface water data were sourced from the Joint Research Centre (JRC) Global Surface Water Mapping Layers v1.4 at 30 m resolution. This long-term dataset (1984–2021), derived from Landsat imagery and accessed via Google Earth Engine, was used to assess the temporal and spatial dynamics of water bodies and wetlands.

- Infrastructure data, particularly the road network, was obtained in polyline shapefile format from OpenStreetMap (OSM). This information was incorporated to assess infrastructure exposure and accessibility of flooded areas, helping to identify the most vulnerable sectors and guide response planning.

3.1.2. Computational Tools and Processing Software

In this study, several computational tools and software were employed to support data processing, analysis, and modeling (Table 2):

Table 2.

Main Software Tools and Their Roles in Data Processing and Analysis.

Google Colab was used to develop and execute Python scripts for data preprocessing, statistical analysis, and machine learning. Its high-performance cloud-based computing capabilities facilitated the intensive tasks of training and validating the Random Forest models.

Google Earth Engine (GEE) was exploited to access and process satellite imagery, perform spatial analysis, and derive key environmental variables. The platform’s cloud computing capabilities enabled the integration of multi-temporal and multi-source remote sensing data, which enhanced the accuracy of flood susceptibility mapping.

ArcGIS environment was used to generate topographic and hydrological indices from the ALOS PALSAR DEM and to produce the final thematic maps.

3.2. Preparation of Flood Factors for Susceptibility Mapping

To facilitate flood susceptibility mapping using the Random Forest model, twelve determining parameters were selected and preprocessed to ensure spatial homogeneity, consistent projection, and uniform data format. These factors were chosen based on their geomorphological and hydrological relevance:

Altitude: Derived from the ALOS PALSAR 12.5 m DEM and resampled to 10 m, this map represents the terrain’s relative elevation of points and helps identify low-lying areas.

Slope: Generated using the Slope Tool on the resampled DEM, this parameter is critical in flood modeling as steeper slopes increase runoff velocity and reduce water accumulation, whereas flatter areas favor flood retention.

Aspect: Computed using the Aspect Tool, this identifies the directional orientation of slopes, which influences water flow direction and accumulation patterns.

Curvature: Extracted using the Curvature Tool, this identifies concave areas that are prone to water accumulation.

Drainage Density: Derived using the Line Density Tool on the hydrographic network extracted from the resampled 10 m ALOS PALSAR DEM, it represents the concentration of surface water drainage pathways, which is crucial to understand the watershed’s capacity to evacuate flood water.

Topographic Wetness Index (TWI): TWI identifies areas prone to water accumulation by analyzing surface saturation potential. It is calculated using the following Equation (1):

where “As” is the flow accumulation scaled to spatial resolution and “β” is the slope angle in degrees [32].

Topographic Roughness Index (TRI): TRI measures terrain irregularity, which affects water flow resistance and floodwater dispersion. It is calculated as follows (Equation (2)):

where “Avg”, “Min” and “Max” represents the average, minimum and maximum altitude values within a specific neighborhood window

Sedimentary Transport Index (STI): STI evaluates sediment transport capacity, indicating regions susceptible to erosion and sediment deposition, which can alter river channels and drainage efficiency. It is calculated using Equation (3) developed by [33]:

where “As” is Flow Accumulation and “β” is the slope in percent increase.

Stream Power Index (SPI): SPI assesses the erosive power of surface runoff. It is determined by Equation (4):

where “As” is flow accumulation, “β” is slope in percent, and the small constant “0.001” prevents issues with a logarithm of zero.

Precipitation: Derived from CHIRPS, the spatial distribution of rainfall was generated using the Inverse Distance Weighting (IDW) interpolation method.

Distance to Roads: Computed using the Euclidean Distance Tool, this reflects how the road network can act as a barrier or a conduit for flood water.

Land Use and Land Cover: Classified from Sentinel-2 imagery using an object-oriented classification. The classification process involved image preprocessing, cloud filtering (retaining images with less than 30% cloud cover), and the computation of biophysical indices, including: Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI) and the Normalized Difference Built-Up Index (NDBI) based on Equations (5) and (6), to improve segmentation accuracy.

where NIR is the near-infrared band, R is the red band and SWIR is the short infrared band.

3.3. Database Preparation and Analysis

3.3.1. Training Data Collection and Preprocessing

To train the model, Sentinel-1 SAR data were filtered and clipped to the study area for the relevant timeframes. Change detection analysis was conducted by comparing pre- and post-flood mosaics to generate a binary raster (flooded = 1, non-flooded = 0). A threshold of 1.25 was used for flood detection.

To refine the flood layer, the Global Surface Water Dataset was used to mask permanent water bodies. A slope mask was also applied to exclude areas with a gradient exceeding 5%, ensuring that only topographically relevant flood-prone regions were analyzed. Connectivity analysis was also performed on the flood pixels to eliminate isolated misclassified pixels.

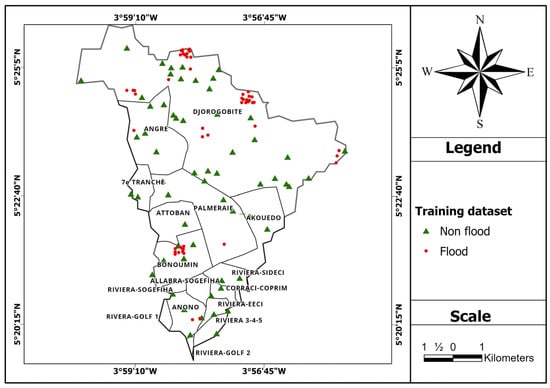

A total of 120 training points were automatically and randomly selected. This dataset (Figure 2) consists of sixty (60) flooded points (labeled 1) and sixty (60) non-flooded points (labeled 0). Flooded points were sampled from the detected flooded extent, while non-flooded points were generated from areas where no flooding was observed.

Figure 2.

Location map of model training data.

3.3.2. Extraction of Flood Factors for Sampling Points

During the data preprocessing phase, the values of the twelve flood conditioning factors were extracted at the locations of the 120 sampling points. This operation was performed by spatially intersecting the point dataset with the corresponding thematic layers, thereby assigning the specific flood factor values to each flooded and non-flooded location.

The result of this process is a feature matrix (structured attribute table) where each sampling point is associated with a complete set of flood conditioning variables. This processed dataset serves as the input for the training and validation of the Random Forest model.

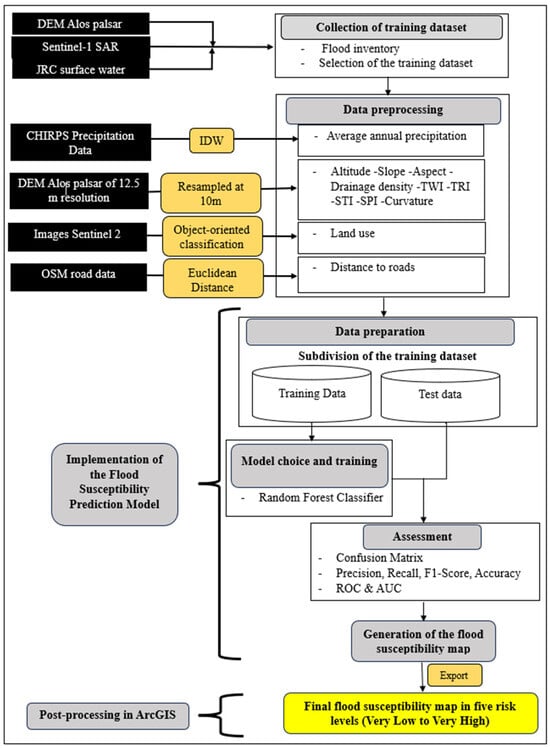

3.4. Implementation of the Flood Susceptibility Prediction Model

Flood susceptibility modelling was carried out using the dataset derived from the extraction of flood conditioning factors. The workflow focuses on variable definition, dataset partitioning, and preparation of the model for training and validation. The integrated methodological approach used to identify the flood prone areas is summarized in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Methodological flowchart for the implementation of the Random Forest model for mapping flood-prone areas in the Bonoumin Palmeraie watershed.

- Step 1: Variable Definition

Flood occurrence was defined as a binary dependent variable, where flooded and non-flooded points were coded as 1 and 0, respectively. The twelve flood conditioning factors served as independent variables (predictors). Geographic coordinates were excluded from the predictive modelling process and retained solely for spatial mapping of the results.

- Step 2: Dataset Partitioning

To evaluate the model performance, the dataset was randomly partitioned into a training subset (80%) and a testing subset (20%). A fixed random seed was applied during the split to ensure reproducibility of the modelling results and to allow for consistent performance comparisons across different model iterations.

- Step 3: Model Selection

The Random Forest (RF) classifier was selected for its robustness and efficiency in processing complex, non-linear geospatial data. While the training sample size is relatively small (120 points), it was deemed sufficient as the sampling strategy ensured representative coverage of the diverse environmental and hydrological conditions of the watershed.

Random Forest operates on the bagging (bootstrap aggregating) principle, which constructs multiple decision trees from random sub-samples with replacement. This approach acts as a form of internal data augmentation, improving the stability and predictive accuracy of the model even with a limited training set. To enhance robustness and reproducibility, a 10-fold stratified cross-validation was used during hyperparameter tuning. The final parameters selected were:

- Number of trees (n_estimators): 300, to ensure prediction stability,

- Maximum tree depth (max_depth): 5, to prevent overfitting,

- Minimum samples per split (min_samples_split): 4, to avoid decisions based on insufficient observations,

- Maximum features (max_features): Square root of the total number of variables, promoting tree diversity and generalization capacity.

- Step 4: Training and Validation

The model was trained on the training subset and then evaluated on the test subset. Its performance was quantified using Overall Accuracy and the Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curve, whose area under the curve (AUC) allows to assess the model’s ability to discriminate between flooded and non-flooded areas. These metrics are defined in the following section.

- Step 5: Prediction and Flood Susceptibility Mapping

The trained and validated Random Forest model was applied to the entire watershed at 10 m resolution to predict flood susceptibility for each pixel in the study area. These probabilities were used to generate the Flood Susceptibility Map (FSM), providing a continuous spatial representation of flood risk.

- Step 6: Exporting the Results

The results, including probability values and spatial coordinates, were exported in shapefile and GeoTIFF formats. These outputs are compatible with geographic information systems for further spatial analysis.

- Step 7: Post-processing and mapping in ArcGIS

The exported prediction results, provided in GeoTIFF formats were integrated into ArcGIS for post-processing. To facilitate interpretation for urban planning and disaster management, the continuous probability values were reclassified into five categories: Very Low, Low, Medium, High and Very High. This was performed using the natural break (Jenks) method, which optimizes the grouping of values by minimizing within class variance and maximizing the variance between classes.

3.5. Model Performance Evaluation

The performance of the classification models was evaluated using several statistical indicators to assess the precision and reliability of the predictions. These metrics are derived from the confusion matrix, then supplemented by the analysis of the ROC curve and the area under the curve (AUC), in order to obtain both a local and global evaluation of the model’s discriminative power.

3.5.1. Confusion Matrix

The confusion matrix is the fundamental tool for evaluating classification models. It compares the model’s predictions against observations in a contingency table, categorizing instances into four main outcomes (Table 3).

Table 3.

Confusion matrix defining the four outcomes.

3.5.2. Evaluation Metrics

From the confusion matrix, several performance metrics were calculated:

Precision (User Accuracy) measures the proportion of correct positive predictions among all positive predictions made by the model. It is expressed by the following equation:

Recall (Sensitivity or Producer Accuracy) indicates the model’s ability to correctly identify all truly positive instances. It is defined by the relationship

F1-score combines precision and recall into a single metric, providing a balanced measurement between these two indicators. It corresponds to their harmonic mean and is calculated according to the equation:

Finally, the Overall Accuracy (OA) corresponds to the ratio between the total number of correct predictions and the total number of observations. It is given by equation

In addition, two types of averages were used to summarize the overall performance of the model. The macro average calculates the average of the indicators for each class by giving them the same weight, regardless of the number of samples, while the weighted average takes into account the number of samples per class, giving more weight to the majority classes. These two measures offer a complementary view: the macro average evaluates the relative performance between classes, and the weighted average reflects the overall performance on the whole data set.

3.5.3. ROC Curve and Area Under the Curve (AUC)

The ROC (Receiver Operating Characteristic) curve and the AUC (Area Under the Curve) were used to assess the model’s discriminatory ability.

The ROC is a probability curve representing the relationship between the True Positive Rate (TPR) and the False Positive Rate (FPR) at different classification thresholds where the TPR is on the y-axis and FPR is on the x-axis. These rates are obtained from the following Equations (7) and (8):

To evaluate the overall performance of the model when classifying data, the AUC (Area Under the ROC Curve) parameter is used [34]. Equation (9) represents the formula for the AUC:

where P is the number of positive points (flooded) and N the negative points (non-flooded).

4. Results

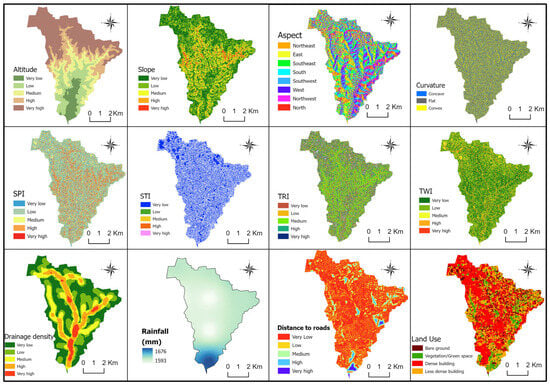

4.1. Factors Conditioning Floods

Eight of the twelve flood-conditioning factors are represented across five susceptibility levels, ranging from Very Low to Very High (Figure 4). The other four include the Aspect map categorized by cardinal and intermediate directions (N, S, E, W, etc.) and the Precipitation map representing the average annual rainfall (1981–2023) across the watershed. The Curvature map differentiates between concave, convex, and flat surfaces to highlight terrain variations affecting water accumulation and runoff. The Land Use/Land Cover map provides a detailed classification, distinguishing between vegetation, bare soil, dense urban areas and sparse settlements.

Figure 4.

Map of flood-conditioning factors.

4.1.1. Topographic and Morphological Factors

The watershed’s elevation decreases toward the central and southern regions, creating natural sinks prone to water accumulation and flooding. The predominance of low to moderate slopes favors water stagnation, whereas steeper slopes present in upstream regions accelerate surface runoff. The direction of slopes (Aspect) favors the flow and accumulation of surface runoff in certain orientations, notably the central and southern zones. The terrain curvature further refines this risk with vast flat areas offering limited natural drainage and concave zones acting as potential water accumulation points, increasing flood risks.

4.1.2. Hydrological and Land Cover Factors

Areas with high SPI values (highlighted in red) along the main watercourses indicate strong runoff potential and erosive power, leading to increased water velocity. Elevated STI values in the northern and central regions suggest high sediment mobility, which can obstruct drainage channels and exacerbate flooding. Relatively low TRI values in the watershed confirm the smooth terrain established from topographic factors, with few natural barriers to slow water flow. Areas with high TWI values indicate zones of high saturation potential, making them susceptible to prolonged inundation.

High drainage density in the central and southern areas is provided by an extensive network of channels that can facilitate the evacuation of water but also lead to accumulation and overflow in these areas during peak events. The Precipitation map shows consistently high average annual rainfall (1981–2023) across the watershed, ranging from 1593 mm to 1676 mm, which underscores the region’s susceptibility to intense rainfall-driven events. While spatial variations across the watershed are relatively minor, the higher rainfall levels observed in the south exacerbate flood risks toward the outlet. This increased local precipitation combines with accumulated runoff draining from the northern upstream regions creating a compounding effect.

The dominance of impervious surfaces in the dense and less dense built-up areas (illustrated in red and orange) significantly reduces infiltration, directly increasing the volume and speed of surface runoff. Accordingly, the limited green spaces and bare soil provide limited flood mitigation potential. Most of the waterways are in close proximity to roads, making both urban areas highly exposed to flood hazards and disrupting natural drainage.

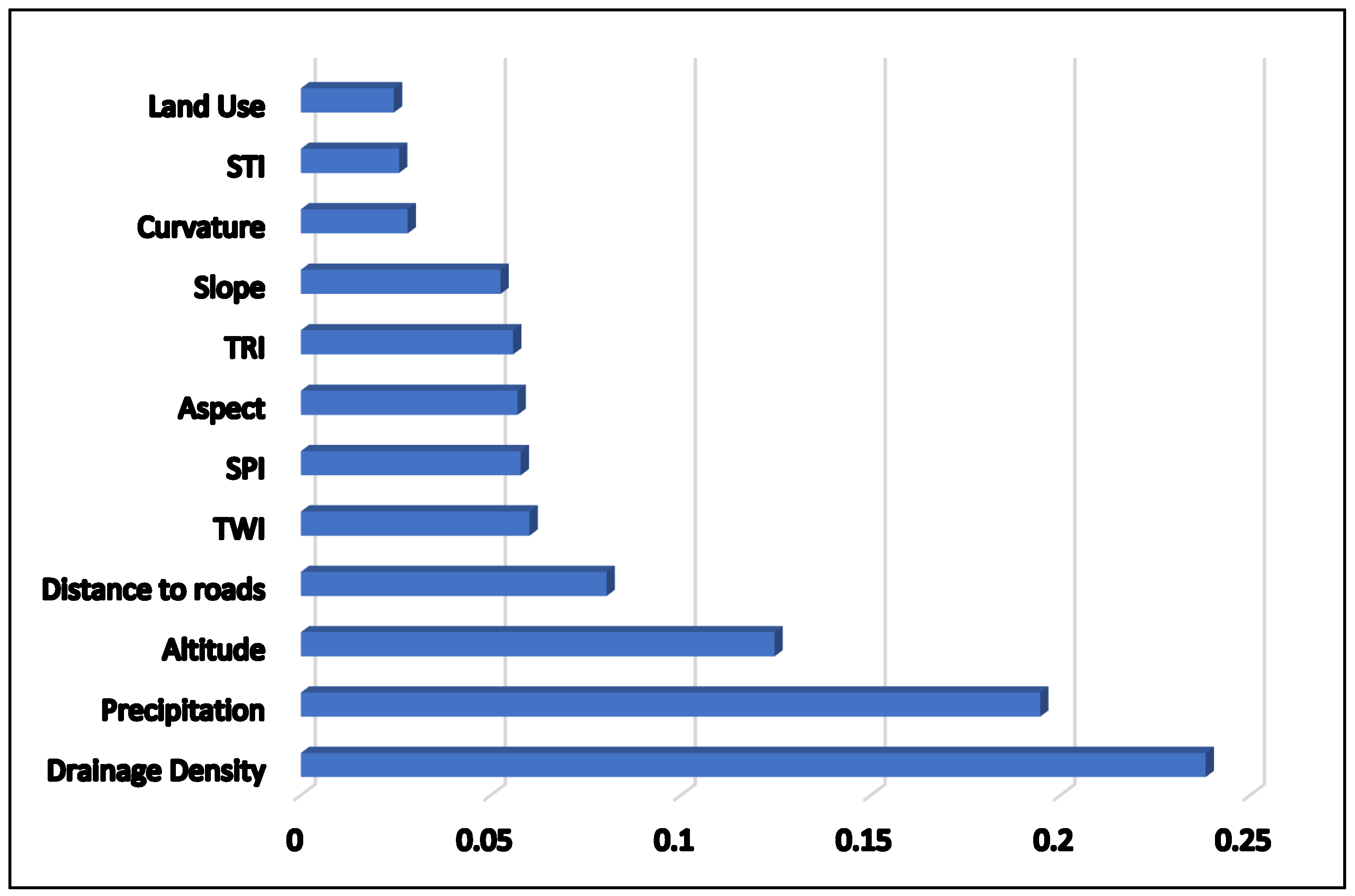

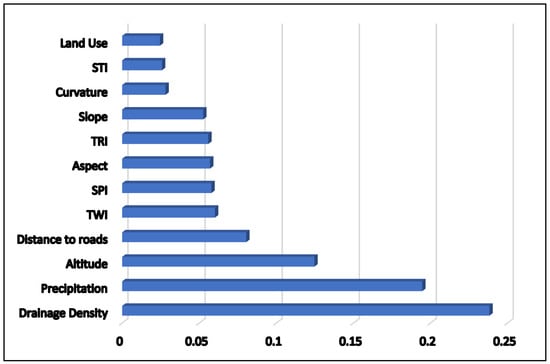

4.2. Importance of Predictive Factors

The relative importance of factors influencing flooding, as determined by the Random Forest model, highlights the specific contribution of each variable to flood susceptibility within the Bonoumin-Palmeraie watershed (Figure 5). The analysis identifies drainage density (0.24), precipitation (0.19), and altitude (0.12) as the three most critical drivers of flood occurrence in the study area.

Figure 5.

Importance of predictive factors according to the Random Forest model.

Drainage density emerges as the most influential predictor, underscoring the significant role of surface water networks. High drainage density often indicates areas where runoff is concentrated; during heavy rainfall these channels frequently reach their capacity, leading to backwater effects and overflow. This finding highlights the urgent need to expand and maintain drainage infrastructure in these densely networked hydrological areas.

Precipitation is the second most important factor, reinforcing the direct impact of rainfall intensity on flood occurrence. Given the high annual precipitation totals in the region (1593–1676 mm), intense events generate significant surface runoff volumes. This emphasizes that flood management must prioritize stormwater retention and/or drainage as well as land use regulations to favor infiltration and urban drainage, especially in southern areas where precipitation-driven floods are compounded by runoff from the northern upstream zones.

Altitude remains a crucial determinant, as lower-elevation areas are prone to water accumulation and lead to prolonged water stagnation. The latter also increases the likelihood of flooding during subsequent high rainfall events. Conversely, the higher elevations in the northern watershed accelerate runoff, effectively transferring the flood risk to downstream southern locations. This finding advocates for topographically informed urban planning, and possible restrictions in low-lying high-risk zones.

Secondary factors, such as distance to roads and TWI, have a moderate influence on flood susceptibility. The Proximity to roads is significant because impervious road surfaces disrupt natural infiltration and channel runoff. TWI, while secondary, helps pinpoint high saturation potential based on terrain characteristics.

In contrast, variables such as curvature, slope, land use, and topographical indices (SPI, TRI, STI) exhibit relatively lower influence. While these factors contribute to localized variations, their overall impact is overshadowed by primary hydrological and climatic parameters. The lower weight assigned to land use, despite its known role in determining infiltration and runoff, is likely a result of the advanced state of urbanization in the watershed. The limited land use variability and the scarcity of natural vegetation leads to less spatial contrast than other parameters, thereby reducing its predictive power.

4.3. Random Forest Model Performance

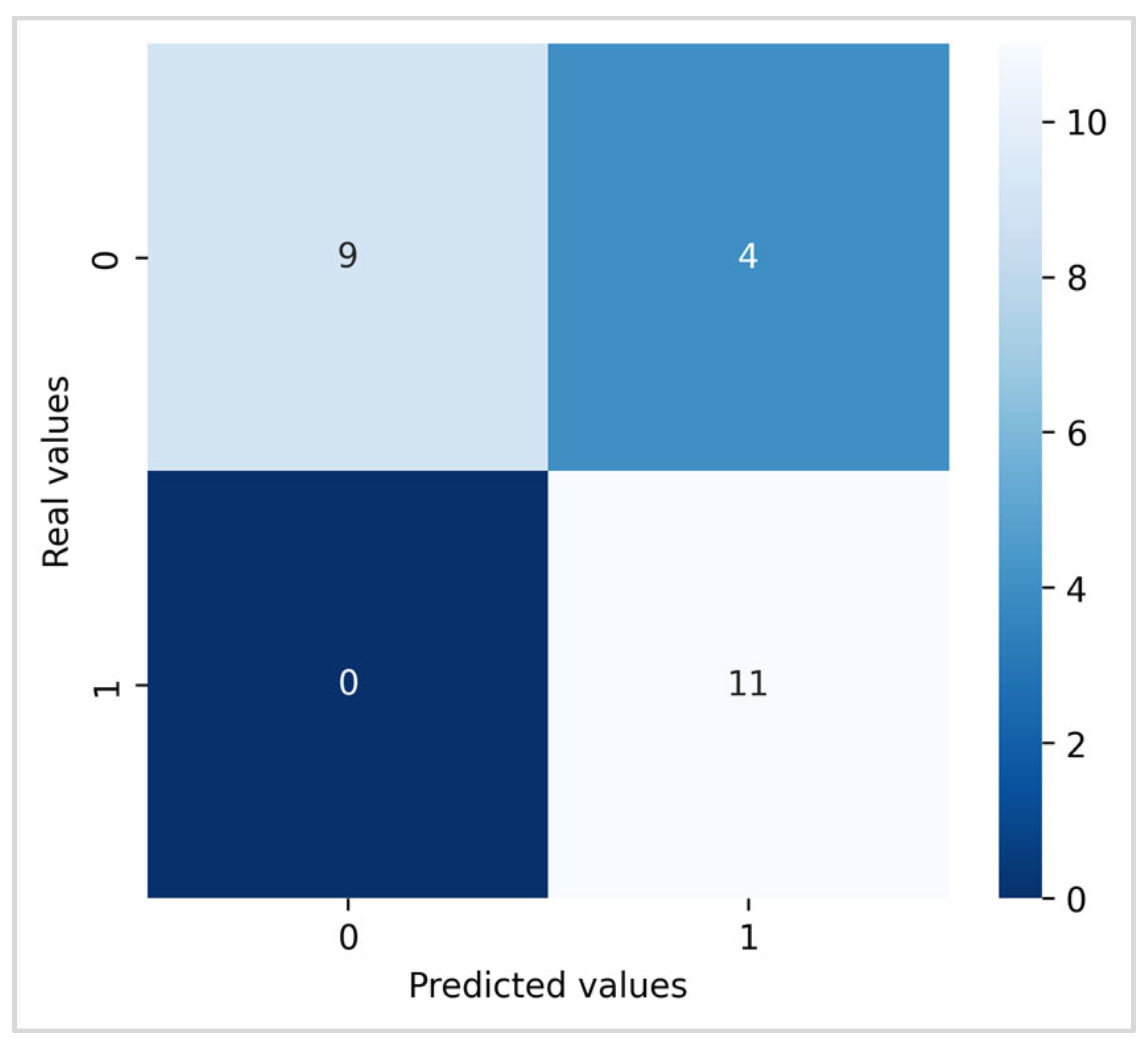

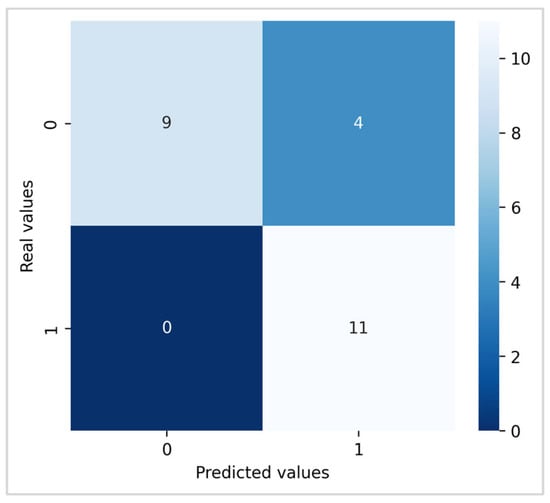

4.3.1. Confusion Matrix Analysis

The confusion matrix of the Random Forest model provides a detailed assessment of the flood classification performance (Figure 6). The vertical axis corresponds to the actual values (0 = not flooded, 1 = flooded) and the horizontal axis to the predicted values using the same coding. Among the 24 testing observations, 11 actually flooded points were correctly identified as flooded (True Positives) and 9 non-flooded areas were correctly identified as not flooded (True Negatives). While no flooded areas were missed (zero False Negatives), four non-flooded areas were incorrectly predicted as flooded (False Positives).

Figure 6.

Confusion Matrix.

4.3.2. Performance Indicators (Precision, Recall, F1-Score, Accuracy)

The performance metrics, including class specific and global indicators, highlight the reliability of the classification (Table 4). For the “Not Flooded” class, the model achieves a precision of 1.00, indicating that all areas predicted as not flooded are indeed correct, while the recall of 0.69 reveals that 31% of truly non-flooded areas were misclassified as flooded, leading to an F1-score of 0.82. For the “Flooded” class, the recall is maximal (1.00), demonstrating that 100% of flooded areas were successfully captured, while the precision of 0.73 reflects the inclusion of some false positives, resulting in an F1-score of 0.85. The Overall Accuracy of the model is 0.83, confirming that 83% of the predictions across the 24 test samples were correct. The macro averages (precision = 0.87, recall = 0.85, F1-score = 0.83) indicate a high and balanced performance between the two classes. Similarly, the weighted averages (precision = 0.88, recall = 0.83, F1-score = 0.83) reflect the real distribution of the observations and provide a robust global view of the model predictive power.

Table 4.

Performance metrics.

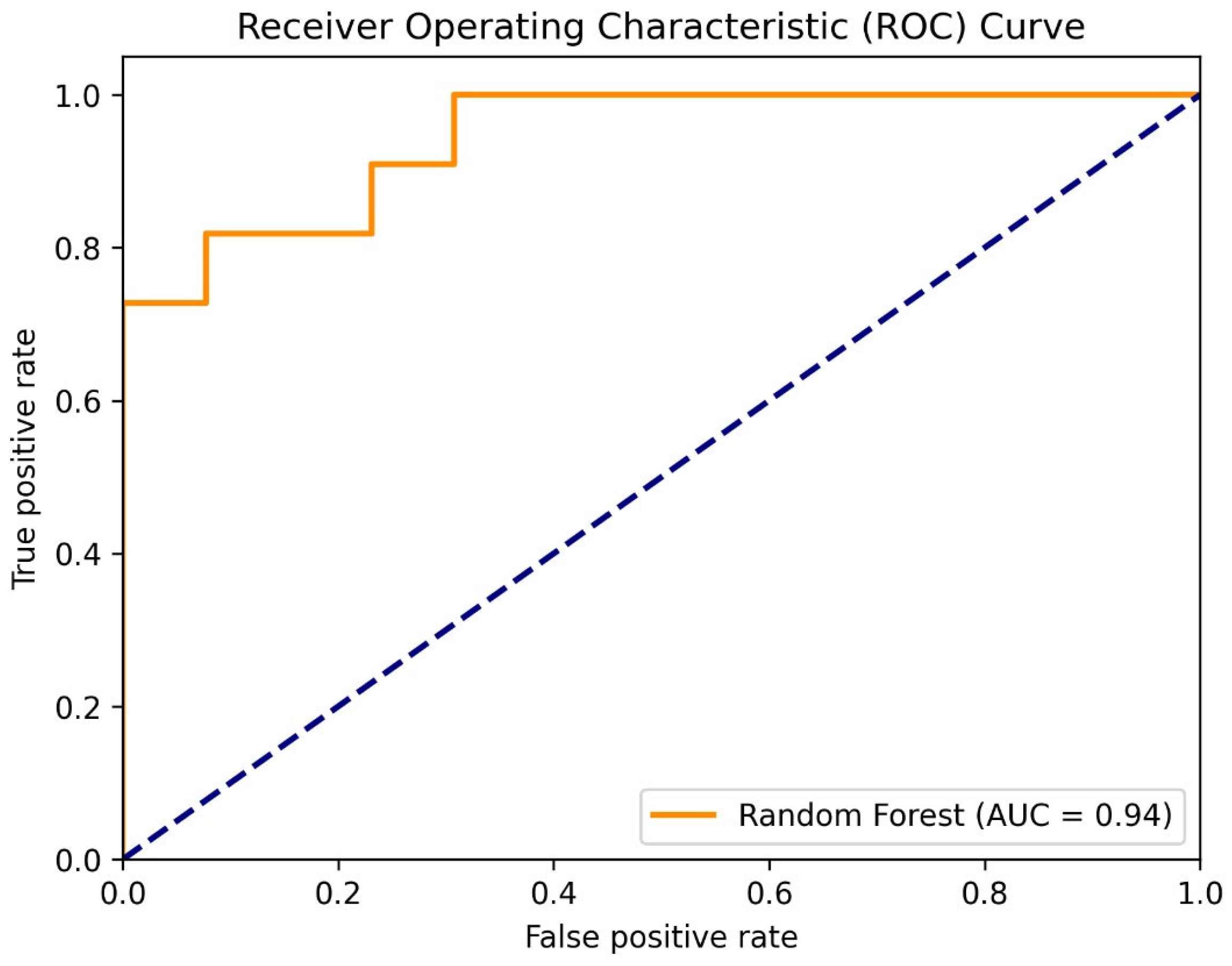

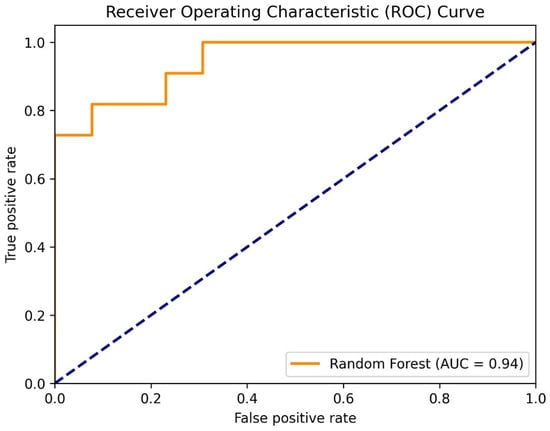

4.3.3. ROC Analysis and AUC

The ROC curve for the Random Forest model yielded an AUC value of 0.94, demonstrating a strong ability to distinguish between flooded and non-flooded classes on the test data. This high performance confirms the model’s reliability to identify flood-prone areas with high precision and minimal error (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

ROC-AUC curve after evaluation of the Random Forest model.

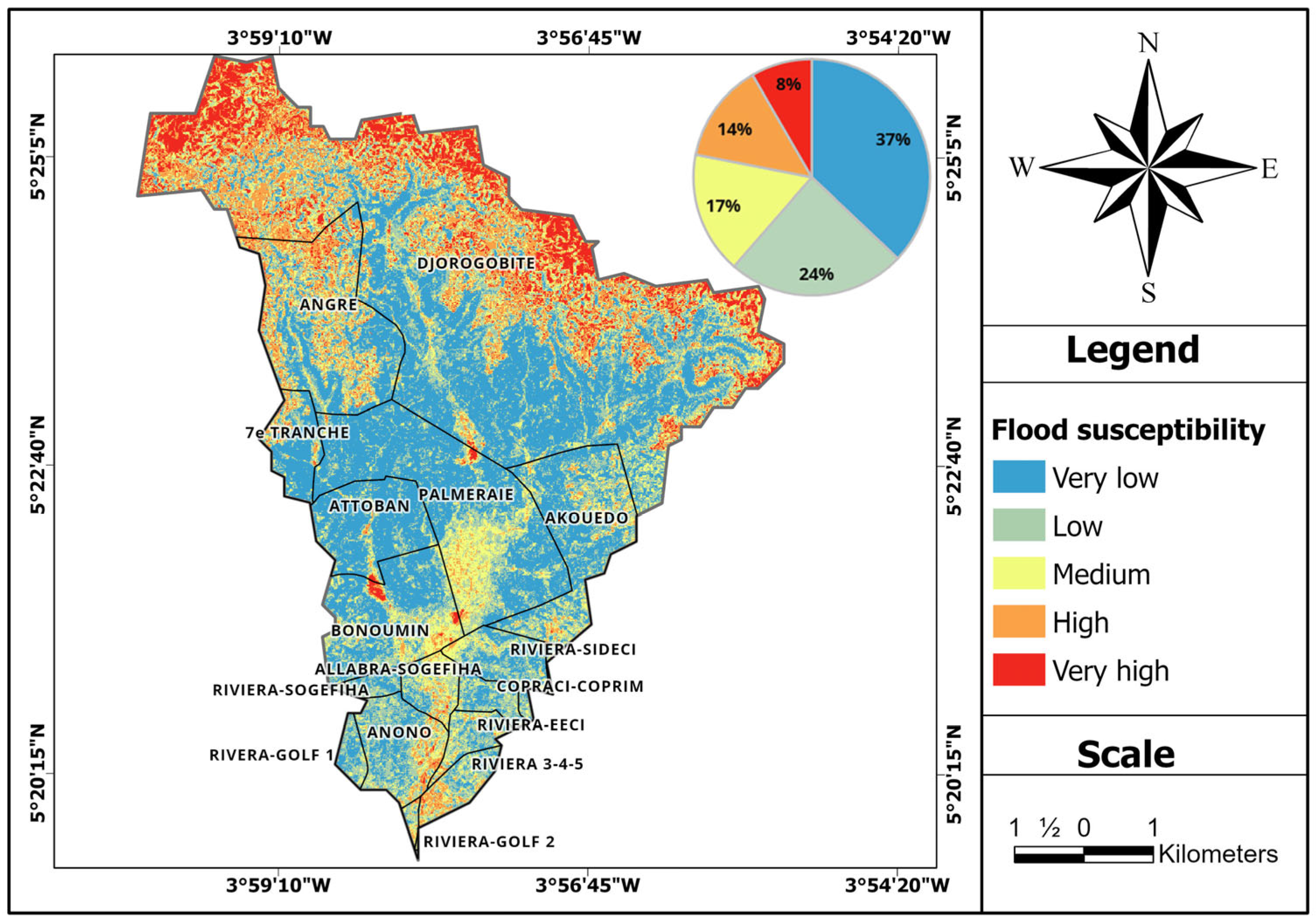

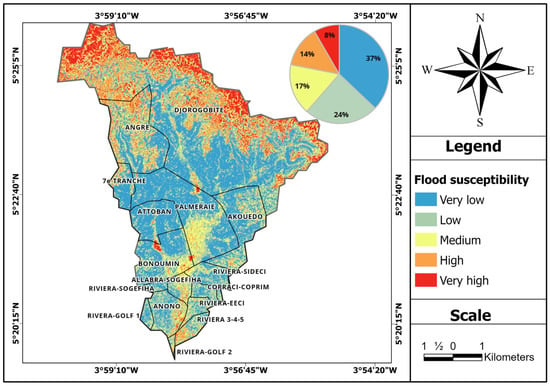

4.4. Flood Susceptibility Map Based on Random Forest Modeling

The final flood susceptibility map reveals a varied spatial distribution across the Bonoumin-Palmeraie watershed (Figure 8). Areas with Very Low flood susceptibility, represent the largest portion of the basin (37%) and pose minimal risk to the built environment. Areas with Low susceptibility (24%) present a manageable but slightly higher risk. Areas with Medium susceptibility (17%) require prudent, proactive management and hydrological monitoring, as they represent a transitional risk level. Areas with High susceptibility (14%) demand special attention and the implementation of targeted flood prevention and mitigation measures. These areas are strongly associated with dense urban development and high-density drainage networks, where reduced infiltration and increasing impervious surfaces exacerbate runoff-induced flooding. Finally, areas with Very High susceptibility (8%) require constant vigilance and monitoring to protect residents and infrastructure as well as immediate flood risk mitigation strategies. These critical hotspots, highlighted in red, are located near major drainage pathways and low-lying urban sectors such as Palmeraie, Djorogobité, Attoban, and Akouedo. Due to their topographic position and urbanization rate, these locations are exceptionally vulnerable to flash floods, infrastructure damage, and the displacement of residents during extreme precipitation events.

Figure 8.

Flood susceptibility map.

5. Discussion

The integration of geospatial technology and machine learning to map flood-prone areas in the Bonoumin-Palmeraie watershed, in Abidjan, Côte d’Ivoire, represents a significant advancement in local flood risk assessment. By defining five susceptibility classes ranging from Very low to Very high, the study provides an innovative perspective on the catchment’s vulnerability, the reliability of which is tied to the quality of the input parameters [35]. Our study used a multi-dimensional approach, integrating twelve topographical (elevation, slope, TRI, SPI, etc.), climatic (precipitation) and anthropogenic (including distance to roads, urbanization) flood-conditioning criteria. This methodology aligns with the work of Seydi (2022), who employed comparable criteria to evaluate machine learning algorithms for flood susceptibility [36]. The GIS environment facilitated data manipulation and spatial interpolation across the study area, but potential margins of error due to the resolution of datasets–notably precipitation derived from CHIRPS gridded datasets-may influence the absolute precision of the final outputs. Furthermore in the absence of a comprehensive historical flood database for the Bonoumin-Palmeraie basin, we adopted the approach recommended by Duwal et al. [37] using Sentinel-1 radar imagery for past flood detection. The lack of extensive field-based ground truthing for several of the datasets remains a common challenge that can affect the accuracy of the outputs.

The analysis of the confusion matrix and the ROC curve demonstrates the ability of the Random Forest model to effectively discriminate between flooded and non-flooded zones. Achieving an AUC of 0.94, the model reflects excellent discriminatory capacity, thanks to relevant explanatory factors and effective training and validation datasets. The absence of false negatives suggests that the model is highly effective at capturing all actual flooded areas, while the small number of false positives indicates a slight overestimation of risk. The precision, recall and F1-score values show a balanced performance between the two classes, with an overall accuracy of 0.83 and stability confirmed by the proximity of the macro and weighted averages. When compared to similar research, our model shows high competitive performance. For instance, Farhadi and Najafzadeh (2021) achieved an AUC of 0.91 [38] using the same RF algorithm in the Galikesh catchment. The slight difference in performance may be attributed to local environmental factors and the combination of predictors used. such as drainage density and precipitation which we identified as the primary drivers of flood occurrence.

Our machine learning based estimates indicates that 39% of the watershed falls into the Medium to Very High susceptibility categories. This is notably lower than results from traditional GIS-based multi-criteria analyses (52%) or index based methods (71.7%) performed in the region [39,40]. These discrepancies can be attributed to the subjectivity inherent in traditional weighting methods, whereas AI-driven models offer greater objectivity and minimize the risk of overestimation. However, several constraints must be acknowledged. The spatial resolution and temporal frequency of the satellite imagery used may limit the detection of fine variations in the data. This may reduce the accuracy of flood zone assessments, affecting the diversity within training and test datasets and the effectiveness of the model predictions. Despite these limitations, the results obtained are robust and provide a scientifically sound foundation for urban planning and disaster risk reduction strategies by the relevant authorities in Cote d’Ivoire. This study also highlights the importance of integrating historical data, advanced predictive models and mapping techniques to better inform flood management strategies. The ongoing collection and integration of ground and satellite observations and the improvement of predictive models will further enhance the accuracy of flood risk maps and help reduce the negative impacts of floods on people and infrastructure.

6. Conclusions

This study provides a comprehensive assessment of flood susceptibility within the Bonoumin-Palmeraie watershed by successfully integrating remote sensing data, GIS-based analysis, and machine learning algorithms. The Random Forest model identified drainage density, precipitation, and altitude as the primary drivers of flood risk. The resulting flood susceptibility map provides a precise spatial delineation of flood hazard zones, offering a critical tool for targeted intervention.

The machine learning approach achieved a high AUC (0.94), ensuring a robust accuracy in the final flood susceptibility mapping. The watershed distribution reveals that 39% of the study area falls within significant risk categories: 17% with medium susceptibility, 14% high susceptibility, and 8% very high susceptibility. This map can be used as a tool for risk management and land use planning. These results move beyond traditional mapping by providing an objective, data-driven framework for risk management and land use planning.

The empirical validation of the model using the recorded flood event of 16 June 2024, indicated good agreement between observed events and significant-risk zones predicted by the susceptibility map. Observed flood points were in areas classified as Medium to Very High flood risk and no flood occurrences were recorded in areas classified as Low Risk, confirming the reliability of the model.

These findings advocate for proactive flood management strategies, including improved drainage infrastructure, changes to urban planning, and the implementation of early warning systems to mitigate the impacts of recurrent flooding. The study also highlights the importance of continuous data monitoring to enhance predictive accuracy, especially in changing environmental and urban conditions.

By leveraging geospatial technologies and machine learning, this research provides valuable decision-support tools for policymakers, urban planners, and disaster risk reduction stakeholders. Future research should build upon this framework by incorporating real-time hydraulic monitoring, climate change projections, and socio-economic vulnerability assessments. Such a holistic approach is essential to develop sustainable flood mitigation strategies for the Bonoumin-Palmeraie watershed and similar rapidly urbanizing environments across Sub-Saharan Africa.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.H.D. and W.A.A.; methodology, J.H.D., W.A.A., V.C.J.S. and Y.L.A.; software, W.A.A.; validation, V.C.J.S., Y.L.A., A.O. and M.B.S.; formal analysis, W.A.A., V.C.J.S. and Y.L.A.; investigation, J.H.D., W.A.A. and V.C.J.S.; resources, J.H.D. and W.A.A.; data curation, W.A.A.; writing—original draft preparation, J.H.D., W.A.A., V.C.J.S. and Y.L.A.; Writing—review and editing, J.H.D., W.A.A., V.C.J.S., Y.L.A., A.O. and M.B.S.; visualization, W.A.A.; Supervision, V.C.J.S. and Y.L.A.; project administration, J.H.D. and M.B.S.; funding acquisition, J.H.D. and W.A.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the ESA EO-for-Africa RFCMACC Project and the IRN ActNAO.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Calvo-Mendieta, I.; Longuépée, J. Chapitre 25. Risque d’inondation et Développement Durable. Développement Durable Territ. 2010, 16, 315–326. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, Q.; Wang, Y.; Li, N. Extreme Flood Disasters: Comprehensive Impact and Assessment. Water 2022, 14, 1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UN Office for Disaster Risk Reduction. The Human Cost of Disasters: An Overview of the Last 20 Years (2000–2019); UN Office for Disaster Risk Reduction: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Tanoue, M.; Taguchi, R.; Alifu, H.; Hirabayashi, Y. Residual Flood Damage under Intensive Adaptation. Nat. Clim. Change 2021, 11, 823–826. [Google Scholar]

- Agrawal, N.; Elliott, M.; Simonovic, S.P. Risk and Resilience: A Case of Perception versus Reality in Flood Management. Water 2020, 12, 1254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bengaly, S. Evaluation des zones à risque d’inondation dans le bassin versant de Kotoroni à l’aide des outils Géomatiques. In Proceedings of the Journée Internationale des Systèmes d’Information Géographiques (GIS Day), 6e Edition, Bamako, Mali, 3 March 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, C.; Kacou, M.; Koffi, E.S.; Dao, A.; Dutremble, C.; Guilliod, M.; Kamagaté, B.; Perrin, J.-L.; Salles, C.; Neppel, L.; et al. Rainfall Risk over the City of Abidjan (Côte d’Ivoire): First Contribution of the Joint Analysis of Daily Rainfall from a Historical Record and a Recent Network of Rain Gauges. Proc. IAHS 2024, 385, 259–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diabate, M.; Bamba, Y.; Alla, D.A. La Commune de Cocody, Un Territoire Exposé Aux Inondations. Rev. Int. De La Rech. Sci. 2025, 3, 7453–7467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction. UNDRR Annual Report 2023; United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023; p. 44. [Google Scholar]

- Johansson, M. Experience of Data Collection in Support of the Assessment of Global Progress in the Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction 2015–2030–A Swedish Pilot Study. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2017, 24, 144–150. [Google Scholar]

- Konate, D.; Didi, S.R.; Dje, K.B.; Diedhiou, A.; Kouassi, K.L.; Kamagate, B.; Paturel, J.-E.; Coulibaly, H.S.J.-P.; Kouadio, C.A.K.; Coulibaly, T.J.H. Observed Changes in Rainfall and Characteristics of Extreme Events in Côte d’Ivoire (West Africa). Hydrology 2023, 10, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, K.; Choi, S.H. Analysis of Urban Flood Risk for the Implementation of Sustainable Land Use Measures. Clim. Serv. 2025, 38, 100568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maddodi, B.S.; Shwetha, V.; Nirmala, R.; Gopika, S.V.; Laxmi, V.; Shrivastava, S.; Mizera, S. Advances and Challenges in Artificial Intelligence-Driven Flood and Drought Risk Management: A Comprehensive Review. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2026, 164, 113354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, A.; Kuehnert, J.; Fraccaro, P.; Meuriot, O.; Ishikawa, T.; Edwards, B.; Stoyanov, N.; Remy, S.L.; Weldemariam, K.; Assefa, S. AI for Climate Impacts: Applications in Flood Risk. npj Clim. Atmos. Sci. 2023, 6, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, D.-L.; Yang, S.-H.; Hsieh, S.-L.; Wang, H.-J.; Yeh, K.-C. Artificial Intelligence Methodologies Applied to Prompt Pluvial Flood Estimation and Prediction. Water 2020, 12, 3552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosavi, A.; Ozturk, P.; Chau, K. Flood Prediction Using Machine Learning Models: Literature Review. Water 2018, 10, 1536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Rawas, G.; Nikoo, M.R.; Al-Wardy, M.; Etri, T. A Critical Review of Emerging Technologies for Flash Flood Prediction: Examining Artificial Intelligence, Machine Learning, Internet of Things, Cloud Computing, and Robotics Techniques. Water 2024, 16, 2069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Kim, J.-C.; Jung, H.-S.; Lee, M.J.; Lee, S. Spatial Prediction of Flood Susceptibility Using Random-Forest and Boosted-Tree Models in Seoul Metropolitan City, Korea. Geomat. Nat. Hazards Risk 2017, 8, 1185–1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aiyelokun, O.O.; Aiyelokun, O.D.; Agbede, O.A. Application of Random Forest (RF) for Flood Levels Prediction in Lower Ogun Basin, Nigeria. Nat. Hazards 2023, 119, 2179–2195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeng, C. Technological Advances in Flood Forecasting Models. Hydrol. Current Res. 2024, 15, 546. [Google Scholar]

- Pan, D.; Deng, Y.; Yang, S.X.; Gharabaghi, B. Recent Advances in Remote Sensing and Artificial Intelligence for River Water Quality Forecasting: A Review. Environments 2025, 12, 158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abedi, R.; Costache, R.; Shafizadeh-Moghadam, H.; Pham, Q.B. Flash-Flood Susceptibility Mapping Based on XGBoost, Random Forest and Boosted Regression Trees. Geocarto Int. 2022, 37, 5479–5496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aydin, H.E.; Iban, M.C. Predicting and Analyzing Flood Susceptibility Using Boosting-Based Ensemble Machine Learning Algorithms with SHapley Additive exPlanations. Nat. Hazards 2023, 116, 2957–2991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riazi, M.; Khosravi, K.; Shahedi, K.; Ahmad, S.; Jun, C.; Bateni, S.M.; Kazakis, N. Enhancing Flood Susceptibility Modeling Using Multi-Temporal SAR Images, CHIRPS Data, and Hybrid Machine Learning Algorithms. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 871, 162066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shivhare, V.; Kumar, A.; Kumar, R.; Shashtri, S.; Mallick, J.; Singh, C.K. Flood Susceptibility and Flood Frequency Modeling for Lower Kosi Basin, India Using AHP and Sentinel-1 SAR Data in Geospatial Environment. Nat. Hazards 2024, 120, 11579–11610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahabi, H.; Shirzadi, A.; Ghaderi, K.; Omidvar, E.; Al-Ansari, N.; Clague, J.J.; Geertsema, M.; Khosravi, K.; Amini, A.; Bahrami, S.; et al. Flood Detection and Susceptibility Mapping Using Sentinel-1 Remote Sensing Data and a Machine Learning Approach: Hybrid Intelligence of Bagging Ensemble Based on K-Nearest Neighbor Classifier. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammami, S.; Zouhri, L.; Souissi, D.; Souei, A.; Zghibi, A.; Marzougui, A.; Dlala, M. Application of the GIS Based Multi-Criteria Decision Analysis and Analytical Hierarchy Process (AHP) in the Flood Susceptibility Mapping (Tunisia). Arab. J. Geosci. 2019, 12, 653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arora, A.; Arabameri, A.; Pandey, M.; Siddiqui, M.A.; Shukla, U.K.; Bui, D.T.; Mishra, V.N.; Bhardwaj, A. Optimization of State-of-the-Art Fuzzy-Metaheuristic ANFIS-Based Machine Learning Models for Flood Susceptibility Prediction Mapping in the Middle Ganga Plain, India. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 750, 141565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singha, C.; Chakraborty, N.; Sahoo, S.; Pham, Q.B.; Xuan, Y. A Novel Framework for Flood Susceptibility Assessment Using Hybrid Analytic Hierarchy Process-Based Machine Learning Methods. Nat. Hazards 2025, 121, 13765–13810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Coleman, N.; Patrascu, F.I.; Yin, K.; Li, X.; Mostafavi, A. Artificial Intelligence for Flood Risk Management: A Comprehensive State-of-the-Art Review and Future Directions. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2025, 117, 105110. [Google Scholar]

- Okacha, A.; Salhi, A.; Bouchouou, M.; Fattasse, H. Enhancing Flood Forecasting Accuracy in Data-Scarce Regions through Advanced Modeling Approaches. J. Hydrol. 2024, 645, 132283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, I.D.; Grayson, R.B.; Ladson, A.R. Digital Terrain Modelling: A Review of Hydrological, Geomorphological, and Biological Applications. Hydrol. Process. 1991, 5, 3–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, I.D.; Burch, G.J. Physical Basis of the Length-slope Factor in the Universal Soil Loss Equation. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 1986, 50, 1294–1298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messen, H.; Serrah, H. Mapping of flood-prone areas using GIS techniques, remote sensing and artificial intelligence. In Final Year Project Report for Obtaining the State Engineering Diploma in Hydraulics; National Polytechnic School: Alger, Algerie, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Saley, M.B.; Kouamé, F.; Penven, M.J.; Biemi, J.; Kouadio, B.H. Cartographie des zones à risque d’inondation dans la région semi-montagneuse à l’Ouest de la Côte d’Ivoire: Apport des MNA et de l’imagerie satellitaire. Teledetection 2005, 5, 53–67. [Google Scholar]

- Seydi, S.T.; Kanani-Sadat, Y.; Hasanlou, M.; Sahraei, R.; Chanussot, J.; Amani, M. Comparison of Machine Learning Algorithms for Flood Susceptibility Mapping. Remote Sens. 2022, 15, 192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duwal, S.; Liu, D.; Pradhan, P.M. Flood Susceptibility Modeling of the Karnali River Basin of Nepal Using Different Machine Learning Approaches. Geomat. Nat. Hazards Risk 2023, 14, 2217321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farhadi, H.; Najafzadeh, M. Flood Risk Mapping by Remote Sensing Data and Random Forest Technique. Water 2021, 13, 3115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kangah, A.; Alla, D.A. Determination of flood risk zones using digital terrain model (DTM) and geographic information system (GIS): Case of the Bonoumin-Palmeraie watershed (Cocody municipality, Ivory Coast). Geo-Eco-Trop 2015, 39, 297–308. [Google Scholar]

- Kadio, A.M.L. Évaluation Du Risque D’inondation à l’aide Du Modèle D’indice de Risque D’inondation: Cas Du Bassin Versant de La Palmeraie de Bonoumin. Master’s Thesis, Félix Houphouët-Boigny University of Cocody, Abidjan, Côte d’Ivoire, 2020. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.