Abstract

The efficacy of oil spill response depends on the speed of detecting the oil. Detecting submerged oil is more difficult than oil on the water surface, because most conventional sensors are not effective. Oil Detection Canines (ODCs) have been reliably used to detect oil during shoreline spill surveys, and preliminary laboratory studies also showed promising results for detecting oil submerged under water. To confirm their potential, a field study was conducted in a boreal freshwater lake in Northwestern Ontario, Canada to investigate the capability of an ODC to detect submerged weathered oils at depths of 1 to 5 m. Triplicate targets at each depth used weathered diluted bitumen (dilbit), Bunker C residual fuel oil, and Maya crude oil burn residue and both the ODC and handler blinded to the location of each target. Boat-based searches were conducted and the handler identified “alerts” based on ODC behaviour changes that were compared to georeferenced oil target locations. The ODC positively identified seven (7) of the eight (8) dilbit targets at 1 to 5 m, five (5) of the six (6) Bunker C targets at 1 and 3 m, and none of the burn residue targets at 1-m depth. The ability of ODCs to detect submerged or sunken oil in shallow water was clearly demonstrated, adding another technique for submerged and sunken oil surveys with the advantages of real-time data returns, the ability to detect small oil deposits, and an operational capability in shallow waters with potential for detection in deeper water.

1. Introduction

When responding to oil spills in aquatic environments, the speed of detecting the oil is an important determinant of the effectiveness of remediation. Weathering causes physical and chemical changes to spilled oil and begins immediately with exposure to the elements, increasing density and viscosity of the oil and making recovery efforts more difficult [1]. Here, weathering is used to describe the combined effects of the primary (e.g., oxidation, biodegradation) and secondary (e.g., dispersion, dissolution, emulsification evaporation, spreading) alteration processes affecting spilled oil in aquatic environments [2,3]. For some heavy crude oils with a density close to freshwater, the weathering process can lead to the sinking of the oil. Detecting oil submerged at the bottom of a water body is significantly more difficult than oil on the water surface, because many conventional sensors do not work through water.

Oil Detection Canines (ODCs) are extremely effective for supporting shoreline oil spill response surveys [4,5,6]. ODCs have a very low detection threshold and have successfully located weathered oil targets on land buried up to 5 m below the surface [7]. They can also be trained to be highly selective and can find a specific type of oil in the presence of multiple oil deposits [8]. The speed and accuracy of ODCs in locating oil deposits on shorelines is a significant improvement over other techniques and may similarly help to detect oil in non-traditional settings where existing methods are challenged or ineffective.

The continuously expanding capabilities of ODCs and the potential to improve spill response outcomes were recognized in a recent report by the Inter-agency Coordinating Committee on Oil Pollution Research [9]. The report identified two priority research needs that merited further examination: (i) developing new methods of detecting sunken or submerged oil, and (ii) studies to expand the current capabilities of ODCs to support shoreline spill response surveys and operations. The ability of ODCs to detect submerged and sunken oil in the field had not previously been investigated. It was unclear whether sufficient odour-causing chemicals from submerged oil targets would be transported through the water column to the surface to be detectable by canines. Also, operating from a boat restricts the ODC’s area of movement and thus their ability to follow a scent and alert on a target as they do during a survey on land.

During a proof-of-concept study a boat-based canine detected a shallow lake-bottom hydrocarbon source during a set of small-scale field trials [10]. This positive result led to the current controlled investigation of submerged and sunken oil using ODCs at the International Institute for Sustainable Development- Experimental Lakes Area (IISD-ELA) field station in northwestern Ontario, Canada. Triplicate submerged targets of weathered diluted bitumen/heavy crude mix (dilbit), Bunker C residual fuel oil, and Mayan crude oil burn residue were used to test the ability of an ODC and handler to locate the oils using a boat-based search.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Location

Opportunities to use real oil during field trials or experiments are very limited due to restrictions on the intentional release of oils on shorelines or in water. The International Institute for Sustainable Development’s Experimental Lakes Area (IISD-ELA) in northwestern Ontario has specific Federal (Fisheries Act, SOR/2014-95) and Provincial legislation (Environmental Protection Act, O. Reg. 60/14) that permits researchers to conduct experimental studies that include the deposit or placement of deleterious substances, such as oil. Approval to release contaminants is scrutinized on a case-by-case basis by a governing body of scientists and provincial authorities, and is contingent on the removal of the oil and the remediation of the environment to baseline conditions at the end of the experiment.

The IISD-ELA is in a remote area of the Canadian Shield east of Kenora, Ontario. Research has been conducted continuously at the site since 1969. Although there are hundreds of lakes in the area, 58 of these lakes comprise the ELA. Lake 260 (49°40′ N, 93°44′ W) was selected for this project and is representative of a typical dimictic, oligotrophic boreal lake. It is relatively small with a surface area of 330,000 m2, volume of 2,000,000 m3 and maximum depth of 16 m. During the last decade several oil spill research projects have been conducted in Lake 260:

In 2018, a study using nine 10 m diameter littoral enclosures investigated the fate and behavior of a gradient of diluted bitumen spills ranging from 1.6 to 156 L [11].

In 2019, nine 5 × 10 m rectangular enclosures were installed on each of two different shoreline types to investigate non-invasive remediation techniques for diluted bitumen spills [12].

In 2021, a follow-up study also examined minimally invasive remediation techniques for spills of conventional heavy crude using similar controlled spills in rectangular shoreline enclosures [13].

Oil was physically removed from all study areas and remediation and monitoring efforts and analytical results indicated that concentrations of polycyclic aromatic compounds (PACs) in water and sediment collected in the vicinity of the 2019 and 2021 studies had returned to baseline levels.

2.2. Oil Detection Canine

A six-year-old English Springer Spaniel (“Poppy”) was used for the project. Poppy is an experienced and certified Oil Detection Canine that has supported oil detection research projects and spill response deployments. Poppy is a generalist ODC, which means she is trained to detect and “alert” to any type of hydrocarbon sample, including weathered and unweathered oils [8,14]. Samples of weathered dilbit, Bunker C, and burn residue were used for initial training using proven protocols for imprinting (associating a target odor with a reward) [15]. Additional details regarding the stepwise training procedures are available in Supplementary Materials.

2.3. Test Oils and Target Deployment

Three different sinking oils were supplied by SL Ross Environmental Research Ltd., for this project, as described in Table 1.

Table 1.

Test Oil Properties and Description.

Approximately 50 g of each target oil was spread onto a new, clean, shallow stainless-steel tray (600 cm2) (Figure 1) using a new clean silicone spatula for each target. Odors are released from the surface of a source [16] so a relatively uniform surface area was the main objective. The lip of the pan made it difficult to spread the oil consistently to the edges so mass was added as an additional metric to ensure similarity of the targets. A small amount (~5% by weight) of barite (Baroid 41 drilling mud) was added to the Bunker C and dilbit mix to ensure that they would sink in fresh water. Barite is a naturally occurring mineral with a high density (specific gravity ~4) that is miscible with oil. Studies have shown that minerals suspended in the water column can mix with spilled oil and produce aggregates that sink [17] and the use of barite mimics this process. The trays were lowered to the bottom of the lake, at pre-measured depths, from a flat-bottom boat. ODC detection trials began with shallow targets (1 m) and proceeded to deeper targets only if positive detections were evident. For test depths of 1 or 3 m, the trays were secured with monofilament fishing line that was tied to an anchor point on shore so that the trays could be retrieved after the trials. For deployments of targets to 5 m, the trays were tied to floating marker buoys for retrieval. Because the buoys could have provided a visual cue for the ODC, three additional marker buoys were deployed without associated oil for each target to maintain a blinded study design. Targets were deployed ~2 h prior to ODC detection trials.

Figure 1.

Stainless steel tray coated with weathered dilbit to create a target.

2.4. ODC Boat-Based Surveys

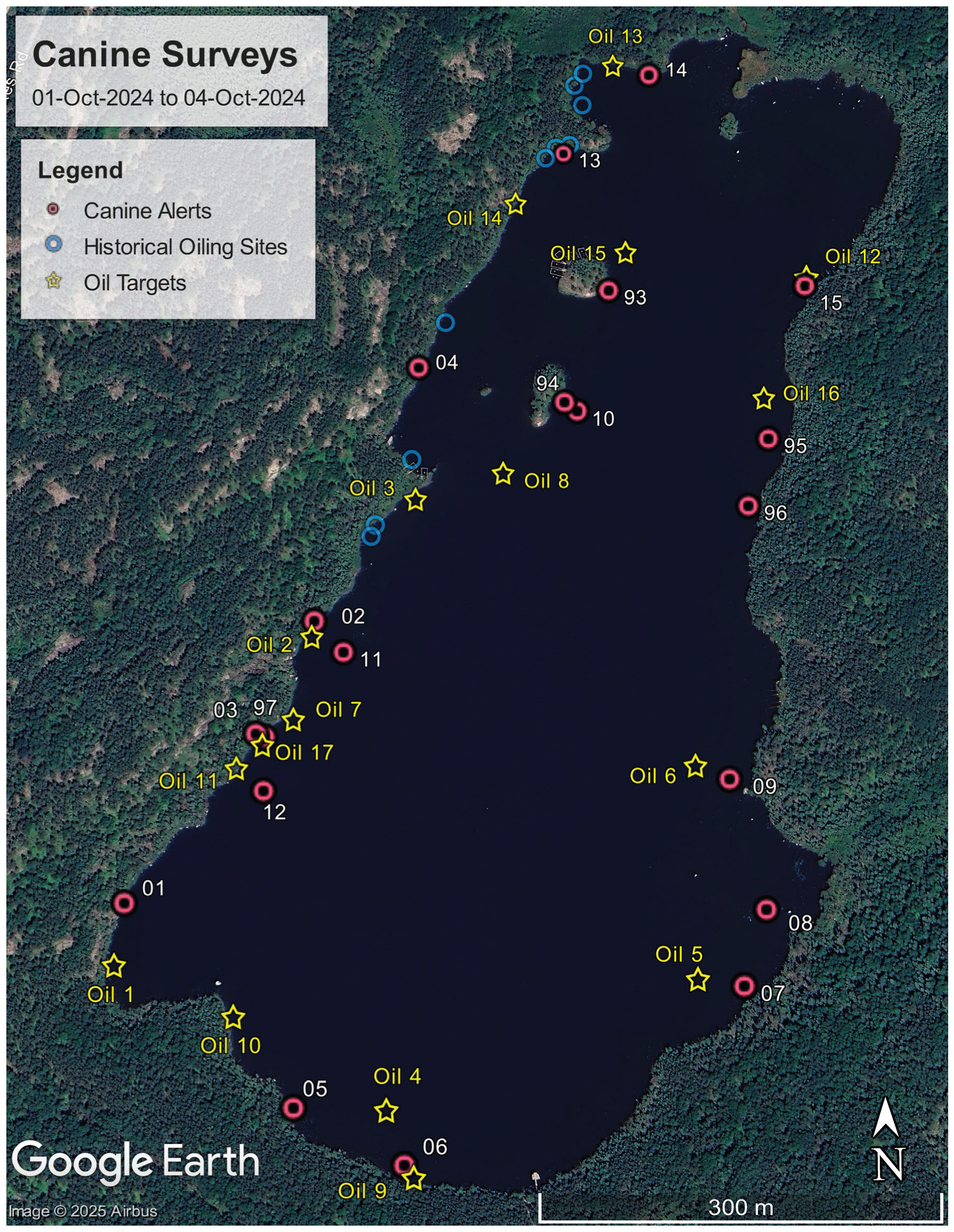

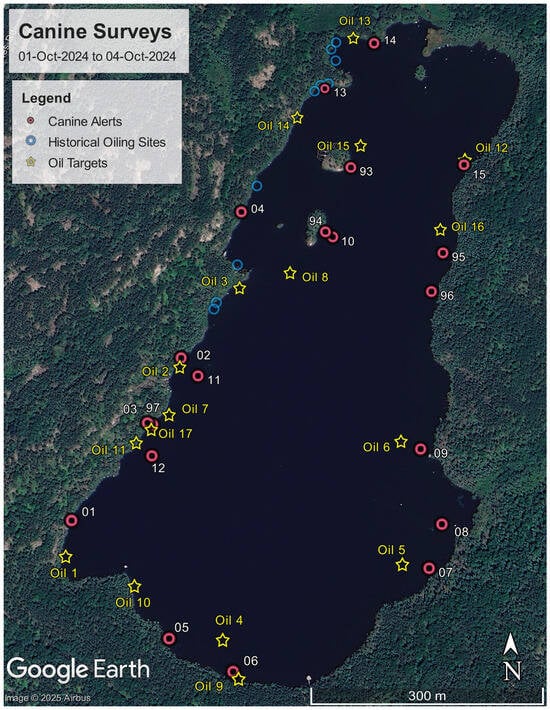

For boat-based surveys to test the ability of the ODC to detect the oil, the team comprised the ODC at the bow (on leash to prevent her jumping into the water), the handler who interpreted the ODC’s behavior and used this to direct the heading of the boat, the boat operator, and an assistant who documented the activities and logged Way Points for each ODC “alert”. On each of the three consecutive survey days (1–4 October 2024), the boat operator was given the general area (400–500 m) in Lake 260 that contained the targets and began each search upwind of those areas (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Location of oil targets (numbered yellow stars), canine alerts (red circles) and the locations of historical experimental oil spill studies (blue circles) that were conducted in Lake 260 from 2018–2021.

The shallow (1 m and 3 m) targets were close to shore and for these targets straight-line search patterns paralleled the shore. Zigzag search patterns, more typical of other oil search procedures, were used for the deeper water 5-m targets. The assistant and canine handler did not know the location of the targets and were only aware of the general area to be surveyed. They did not know the survey’s endpoint until the boat operator informed them that the end was reached. The assistant recorded a GPS location when the handler identified a change in behaviour by the ODC that was indicative of an “alert”. These locations were compared to GPS locations recorded for each oil target at the end of each survey day. Meteorological data for each of the survey days are available in Supplementary Materials.

3. Results

Figure 2 is a composite map that shows target oil locations in Lake 260, survey track lines, canine alerts and the locations of historical experimental oil spill studies that were conducted in Lake 260 from 2018–2021. Individual GPS survey tracking and waypoint (WP) alert maps for each search are provided in Supplementary Materials. A total of 17 oil targets were deployed (Table 2). Only 2 targets of dilbit were deployed at 5 m, and Bunker C was deployed only up to 3 m depth due to time and weather constraints. Because the ISB residue was not detected at 1 m, no targets at deeper locations were deployed.

Table 2.

Summary of target oil deployments and ODC Alerts. The WP-prefix indicates an alert waypoint, presented in Figure 2 as only numbers to avoid overcrowding.

Specific target locations, ODC alert locations, and GPS track lines for each of the six (6) surveys are provided in Supplementary Materials along with descriptions and interpretations for each of the oil targets. A total of seventeen (17) targets of three (3) oil types were deployed variously at 1, 3 and 5 m depths. The ODC provided eighteen (18) responses that were interpreted as “alerts”, detecting seven (7) of the eight (8) Dilbit targets, and five (5) of the Bunker C targets. In five (5) cases an ODC alert was associated with the same target. The ODC did not detect the three (3) burn residues and one dilbit target at 1 m depth. Two (2) ODC alerts were not associated directly with an oil target and could be considered “false positives”, but were in the vicinity of previous oil spill studies and thus are more accurately described as “non-target detections”.

4. Discussion

Canines have been successfully trained to detect oil on shorelines following a spill or oil targets during controlled field trials in a range of terrestrial or shoreline environments [6]. The potential that canines could detect volatile odors associated with submerged or sunken oil was considered because canines have been used to locate submerged or sunken cadavers [18]. In 2016, four ODC teams supported a Shoreline Cleanup Assessment Technique (SCAT) program during an oil spill response on the North Saskatchewan River, Canada [19]. During several surveys, the handlers observed that canines would wade into the river and exhibit a specific Change in Behavior that suggested the canine had identified a target odor. Further investigation of the area, that included disturbing the river sediment, released oil that then formed a sheen on the water surface. During a series of surveys to locate tar balls on the Texas Gulf Coast, a canine was again observed exhibiting a Change in Behavior that included venturing into the sea to follow tar balls as they washed ashore (Bunker, person. observ).

Based on these observations, in 2021 the Bureau of Safety and Environmental Enforcement (BSEE) funded the US Naval Research Laboratory (USNRL) to investigate the detection of oil underwater, including a study with ODCs. A research trial developed protocols supported by a specifically developed underwater training odor delivery device, which resulted in the ability to train ODCs without any risk of releasing oil into the environment [10]. Although the device proved to be effective it had limitations for training protocols, and a second device was developed [20]. However, neither device allowed for the real-world replication of oil submerged under water, rather they simulated the odor profile likely to be encountered. A combination of these training protocols (Supplementary Materials), using the specially developed delivery devices, was used to train a canine for the field trials described for the current study.

A critical feature of an ODC study is the communication method between the canine and the handler. On land, the canine can indicate that the odor from a target has been detected by one of several methods: Changes in Behavior (such as standing at or over the target, wagging its tail, looking at the handler), and/or “alerts” (such as sitting or a prone body position). The canine can distinguish odor concentrations and will typically move within an odor plume to a location where the concentration is at a maximum. In a boat, the canine does not have equivalent mobility and depends on the boat operator to steer towards the target odor by following directional cues suggested by its behaviour. Specifically, when the canine detects a scent plume, it will attempt to keep its nose within the plume because experience has demonstrated to the canine that the plume leads to the source of the odor. To enable the canine to keep its nose within the plume, it will change position in the boat toward the side closest to the plume. If the boat moves away from the plume, the canine will change position, and by assessing these changes, the boat operator can be “guided” by the canine to the source. When the canine holds its nose and position directly over the bow, the boat is headed up the plume toward the source. Proximity to the source can be discerned by the lowering of the canine’s nose and head to the water’s surface.

Before each survey, the boat operator was informed of the general sector in Lake 260 where the targets had been deployed. However, the ODC handler did not have this information and had to design a search pattern to sweep that sector. As is typical for ODC surveys on land, the search was initiated upwind of each sector. For surveys conducted in shallow water (1 and 3 m), each sector included a narrow water section following the shoreline (Supplementary Figure S3). However, a more typical zigzag search pattern was employed for surveys in deeper water (5 m) where the boat had more room to maneuver (Supplementary Figure S4).

Experience and communication between the ODC, handler, and boat driver are an important determinant of success for detecting submerged oil. The current study to detect and locate underwater oil was the first, to our knowledge, that involved training a canine to communicate information regarding the location of oil while confined to the bow of a small boat. During the first searches, the handler adjusted the ODC’s response technique to one that was more suitable for working in a boat. For both the ODC and handler, this learning process may have been a factor in the “non-target detections” recorded at sites used for previous oil spill studies in the lake and the missed targets of Dilbit at 1 m and Bunker C at 3 m.

The ability of an ODC to detect weathered and submerged dilbit at depths of 1 to 5 m, and Bunker C at 1 and 3 m, was effectively demonstrated by the current study. However, several confounding factors may have impacted the results. For example, there is some potential for minute oil residues to have persisted from previous (2018–2021) oil spill research in Lake 260. Diluted bitumen, upon which the ODC had been imprinted, was used in the 2018 and 2019 research projects, and a conventional heavy crude oil was used in 2021. Although the oil was removed from the shoreline enclosures, and analytical results indicate near baseline concentrations in water and sediment [13], it is possible that small amounts, below instrument detection limits, remained. Research has shown that ODCs can detect oil concentrations down to parts per billion, so that even extremely small amounts of residue, below the detection limits of instrumentation, may have been detected by the ODC, offering a potential explanation for the ODC’s “non-target detections” on the first set of dilbit surveys at 1 m depth.

Another potential confounding factor was the effect of wind on the odor plume at the water surface. Odors from an underwater source may move in one direction in the water column as the molecules rise to the surface (i.e., with the current or wave action) but then shift to another direction at the surface when the gas phase molecules encounter wind. While the specific mechanisms of odor movement through water are not well understood [21], they can be modeled based on similar research. Volatile Organic Compounds (VOCs) emanate from the target and are transported to the surface and into the air through various processes, including advection, surface exchange, and atmospheric dispersion [22]. Oil sources underwater continually release VOCs into the water, which can be released as gases, particulates, or microdroplets. The initial influence on the molecules’ transport through water is advection (water currents) and diffusion; this transport may be calculated using the Advection–Diffusion Equation (ADE) [23] used for relative positioning. As a result of these influences, molecules often do not rise vertically but instead form an underwater plume that rises to the surface down-current of the target. Once at the surface, an odor forms an expression of the target molecules, termed a scent print, before transferring across the water-air interface [24]. The rate at which the molecules transfer from the water’s surface into the air is affected by the temperature of the air, temperature of the water, surface agitation, wind speed, air pressure [25], and Henry’s Law Constant (hydrocarbon gases, which are product-specific). Once in the air, the molecules are affected by the wind and atmospheric turbulence, producing an odor plume that moves downwind [24]. The canine can detect molecules in the odor plume and communicate to the trainer the direction from which the plume is coming. In this way, the boat can be directed to the source of the odor expression on the water’s surface. As the boat and canine get closer to the source, the canine brings its nose down from the odor plume in the air to the source on the surface. At this point, the trainer can mark the location, and, using ADE, it is possible to calculate the target’s location. Understanding the direction of wind and water currents in relation to the oil target is, therefore, essential to clearly assess the canine’s response at an oil spill response event. This is especially true when the ODC is working from a confined area such as a boat that makes moving towards the source of a diffuse plume more difficult for the canine and interpreting the canine’s behavior more difficult for the handler. This study collected meteorological data (Supplementary Materials) onshore at 15-min intervals during the surveys from a nearby meteorological station. Future studies including ODCs in small watercraft should implement constant wind and wave action monitoring on the watercraft throughout the survey transects to best interpret the spatial differences between source site and canine “alert”.

Burn residue was never successfully detected or located by the ODC in the current study. It may be that training an ODC to detect burn residues requires a specific protocol or that larger amounts of burn residue within the water source are required to allow detection. Laboratory analyses of burn residue indicate low concentrations of volatile organic compounds (i.e., odor molecules) that would be available for detection by an ODC [26]. Increasing the surface area and mass of the product at the target and imprinting the ODC on higher molecular weight compounds, more highly retained in the burn residue product, may improve canine detection of this type of product in future studies.

The savings in time and effort to detect subsurface oil on beaches by K9 SCAT surveys have been well demonstrated [27]. Similarly increased efficiency and improved level of confidence can be applied for the detection of submerged and sunken oil in the nearshore zone based on the results of this study. For example, the intertidal and near-subtidal Snorkel SCAT program conducted during the Deepwater Horizon shoreline surveys involved teams of 5–7 persons who completed 1014 mission days on 136 km of shoreline, with an approximate daily coverage of 150 m in length and 40 m in width. By comparison, this study indicates that a boat-based K9 SCAT team could cover the same width at a rate on the order of 1000 m a day.

Validation of this ODC technique not only emphasizes its validity in practical application but also creates the potential for further investigation. At the time of publication our group has begun investigation into ODCs’ ability to detect various oil types under different ice thicknesses on freshwater lakes. Further investigations into the ODCs’ capabilities on open water boat surveys could include lotic environments, wetlands or the effect of stratification on the canine’s ability to detect a scent print at the surface. With regard to the latter, the maximum depth beneath freshwater that an ODC can detect also warrants further investigation. It is very likely to surpass the five meters achieved by this study as this depth was not limited by “Poppy” but rather by our ability to safely retrieve the oil target after surveys.

5. Conclusions

This study has demonstrated for the first time that an ODC can be trained to successfully detect weathered oil targets in freshwater at depths up to 5 m below the surface from a small watercraft. Positive locations by the ODC for two of the three oil types (Dilbit and Bunker C) clearly demonstrated the ability of an ODC to detect submerged oil in freshwater, adding another technique for submerged and sunken oil surveys. Other current techniques oil (i.e., disturbing the bottom sediment and looking for sheen, sampling with cores or dredges, direct observation by divers) require large oil deposits and shallow depths while overcoming additional challenges such as slow survey coverage and data analysis [27]. In contrast, this study shows that ODC boat-based surveys for submerged oil can rapidly cover survey areas and provide real time data, and appear to be effective for small deposits at water depths up to 5 m.

Oil properties governing the amount of odor that can be released into the water are an important limiting factor, however. For example, the ODC did not detect Burn Residue at a depth of 1 m, which is consistent with lower concentrations of volatile compounds in petroleum products after burning. Detecting and locating also requires accurate and swift communication between the ODC and the handler who in turn communicate the appropriate headings during a search survey to the boat operator.

An important application of ODCs for spill response is their ability to rapidly “clear” large areas that have not been oiled and this study shows this ability to be transferable to submerged and sunken oil offshore in freshwater. Results from this study provide field validation of the ODC’s ability to detect specific submerged oil types in freshwater and indicate that ODCs are a viable and effective technique to detect and locate even small, submerged oil deposits in freshwater lakes.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/w18030355/s1, Oil Detecting Canine Training Protocols: Step 1—Oil in Jars, Step 2—Oil Submerged in Jars, Step 3—Oil Submerged in Buckets, Step 4—Boat Training, Step 5—Boat Training at IISD-ELA; Figure S1: The ODC survey boat team: from left to right, the trainer who interpreted the ODC’s behavior and used this to direct the boat’s heading; the boat operator: an assistant who documented the activities and logged Way Points. Poppy the ODC is at the boat’s bow, directing the boat’s heading; Figure S2: ODC and trainer positions during the boat survey. Note that Poppy is restrained in the boat but is able to change positions at the bow of the boat to direct the heading; Figure S3: Search pattern, following the shoreline, employed for shallow-water targets line (Oil #12 at 1-m depth); Figure S4: Search pattern, following a zigzag pattern, employed for deeper-water targets (Oil # 8 at 5-m depth); Figure S5: Survey tracks, oil target locations, and ODC Alerts for the Dilbit targets at 1 m depth; Figure S6: Survey tracks, oil target locations, and ODC Alerts for the Dilbit targets at 3 m depth; Figure S7: Survey tracks, oil target locations, and ODC Alerts for the Dilbit targets at 5 m depth; Figure S8: Survey tracks and oil target locations for the burn residue targets at 1 m depth; Figure S9: Survey tracks, oil target locations, and ODC Alerts for the Bunker C targets at 1 m depth; Figure S10: Survey tracks, oil target locations, and ODC Alerts for the Bunker C targets at 3 m depth; Table S1: Average meteorological data for the duration of each survey. Measurements were taken every 15 min. Note that the wind measurements are average results at 10 m above the ground so that effects at Lake 260 level may not be represented; Table S2: Surface water temperatures and barometric pressures at Lake 260 during the field trials.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: V.P., P.B., E.O., J.M. and D.D.; Formal analysis: V.P., P.B. and L.T.; Investigation: V.P., P.B., L.T., C.B. and J.M.; Project administration: V.P., P.B., L.T., C.B., E.O. and D.D.; Visualization: P.B., L.T. and E.O.; Writing—review and editing: V.P., P.B., L.T., C.B., E.O., J.M. and D.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by funds awarded to V. Palace at the IISD from US Coast Guard’s Center for Oil Spill Expertise based on a Broad Agency Announcement number 70Z02324RBAAGLCOE-1, for Freshwater Oil Spill Preparedness and Response Research and contributions from the International Institute for Sustainable Development Experimental Lakes Area. The above funding sources had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Materials. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

Authors wish to acknowledge that research was conducted at the IISD Experimental Lakes Area field station, situated on the traditional land of the Anishinaabe Nation in Treaty 3 Territory and the Homeland of the Métis Nation.

Conflicts of Interest

Authors Paul Bunker and Christina Brewster were employed by the company Chiron K9, author Ed Owens was employed by Owens Coastal Consulting, and author David Dickins was employed by DF Dickins Associates LLC. The authors also declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as potential conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| BSEE | Bureau of Safety and Environmental Enforcement |

| Dilbit | Diluted Bitumen |

| IISD-ELA | International Institute for Sustainable Development-Experimental Lakes Area |

| ODC | Oil Detecting Canine |

| PAC | Polycyclic Aromatic Compound |

| SCAT | Shoreline Cleanup Assessment Technique |

| USNRL | United States Naval Research Laboratory |

| WP | Waypoint |

References

- Lee, K.; Chen, B.; Boufadel, M.; Swanson, S.M.; Hodson, P.V.; Foght, J.; Venosa, A.D. Behaviour and Environmental Impacts of Crude Oil Released into Aqueous Environments; Royal Society of Canada: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- ITOPF. Fate of Marine Oil Spills; Technical Paper 2; ITOPF Ltd.: London, UK, 2011; p. 12. [Google Scholar]

- Prince, R.C.; Butler, J.D.; Redman, A.D. The Rate of Crude Oil Biodegradation in the Sea. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2017, 51, 1278–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- API. Canine Oil Detection: Field Trials Report; Technical Report 1149-3; American Petroleum Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 2016; p. 67. Available online: https://www.oilspillprevention.org/-/media/Oil-Spill-Prevention/spillprevention/r-and-d/shoreline-protection/canine-oil-detection-field-trials-report.pdf (accessed on 13 January 2026).

- Owens, E.; Bunker, P. Canine Oil Detection: Field Trials Report; Owens Coastal Consultants: Bainbridge Island, WA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Owens, E.; Bunker, P.C. Canine Detection Teams to Support Oil Spill Response Surveys. In Canines: The Original Biosensors, 1st ed.; DeGreeff, L., Schultz, C.A., Eds.; Jenny Stanford Publishing: New York, NY, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Owens, E.; Bunker, P.; Dubach, H.C.; Taylor, E. Field Trials Using Canines to Detect Deep Subsurface Weathered and Heavy Oils. In Proceedings of the 43rd AMOP Technical Seminar; Environment and Climate Change Canada: Gatineau, QC, Canada, 2021; pp. 221–238. [Google Scholar]

- Bunker, P.; Owens, E. Specific Oil Detection by Oil Detection Canines. In Proceedings of the 45th AMOP Technical Seminar on Environmental Contamination and Response; Environment and Climate Change Canada: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Vocke, W.T.; Miller, E.J.; Hudson, C.; Lundgren, S.; Conmy, R.N.; Trego, C.K.R.; Baillie, C.A. Evolution of Federal Oil Pollution Research Planning. Int. Oil Spill Conf. Proc. 2021, 2021, 689043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bunker, P.; Vaughan, S.; DeGreeff, L.; Owens, E.; Tuttle, S. The Detection of Underwater Oil by Oil Detection Canines; Chiron K9: San Antonio, TX, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez-Gil, J.L.; Stoyanovich, S.; Hanson, M.L.; Hollebone, B.; Orihel, D.M.; Palace, V.; Faragher, R.; Mirnaghi, F.S.; Shah, K.; Yang, Z.; et al. Simulating Diluted Bitumen Spills in Boreal Lake Limnocorrals—Part 1: Experimental Design and Responses of Hydrocarbons, Metals, and Water Quality Parameters. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 790, 148537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perry, M.; Hanson, M.; Ankley, P.J.; Palace, V.; Paterson, M.J.; Black, T.A.; Higgins, S.N. The Effects of Diluted Bitumen, the Shoreline Washing Agent Corexit EC9580A, and Bio-Stimulation on the Lower Food Web of a Boreal Lake. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2025, 305, 119260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stanley, M.J.; Peters, L.; Guttormson, A.; Tremblay, J.; Wasserscheid, J.; Timlick, L.; Greer, C.W.; Rodríguez Gil, J.L.; Halldorson, T.; Havens, S.; et al. Assessing Changes to the Root Biofilm Microbial Community on an Engineered Floating Wetland upon Exposure to a Controlled Diluted Bitumen Spill. Front. Synth. Biol. 2025, 3, 1517337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeChant, M.T.; Bunker, P.C.; Hall, N.J. Evaluation of the Capability of Oil Specific Discrimination in Detection Dogs. Behav. Process. 2024, 216, 105014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bunker, P. Imprint Your Detection Dog in 15 Days: A Step-by-Step Workbook; Chiron K9: San Antonio, TX, USA, 2021; Available online: https://chiron-k9.com/publications/ (accessed on 13 January 2026).

- Lazarowski, L.; Krichbaum, S.; DeGreeff, L.E.; Simon, A.; Singletary, M.; Angle, C.; Waggoner, L.P. Methodological Considerations in Canine Olfactory Detection Research. Front. Vet. Sci. 2020, 7, 408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacketti, M.; Beegle-Krause, C.J.; Englehardt, J.D. A Review on the Sinking Mechanisms for Oil and Successful Response Technologies. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2020, 160, 111626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rebmann, A.; David, E. Cadaver Dog Handbook: Forensic Training and Tactics for the Recovery of Human Remains; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Owen, E.H.; Reimer, P.D. River Shoreline Response and SCAT on the North Saskatchewan River: Streamlined Surveys, Segmentation, and Data Management Evolutions. In Proceedings of the Forty-First Artic and Marine Oil Spill Program (AMOP) Technical Seminar; Environment and Climate Change Canada: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2018; p. 22. [Google Scholar]

- Bunker, P. Canine Underwater Search Training Device. U.S. Patent Application No. 63/650,390, 21 May 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Pannunzi, M.; Nowotny, T. Odor Stimuli: Not Just Chemical Identity. Front. Physiol. 2019, 10, 1428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osterkamp, T. K9 Water Searches: Scent and Scent Transport Considerations. J. Forensic Sci. 2011, 56, 907–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osterkamp, T. Detector Dogs and Scent Movement: How Weather, Terrain, and Vegetation Influence Search Strategies; CRC Press/Taylor & Francis Group: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Richards, N.L. (Ed.) Using Detection Dogs to Monitor Aquatic Ecosystem Health and Protect Aquatic Resources; Palgrave Macmillan: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; p. 11. [Google Scholar]

- Faksness, L.G.; Leirvik, F.; Taban, I.C.; Engen, F.; Jensen, H.V.; Holbu, J.W.; Dolva, H.; Bråtveit, M. Offshore Field Experiments with In-Situ Burning of Oil: Emissions and Burn Efficiency. Environ. Res. 2022, 205, 112419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- API. Canine Oil Detection (K9-SCAT) Guidelines; Technical Report 1149-4; American Petroleum Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 2016; p. 81. Available online: https://www.oilspillprevention.org/-/media/Oil-Spill-Prevention/spillprevention/r-and-d/shoreline-protection/canine-oil-detection-k9-scat-guidelines.pdf (accessed on 13 January 2026).

- API. Sunken Oil Detection and Recovery; Technical Report 1154-1; American Petroleum Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 2016; p. 116. Available online: https://www.oilspillprevention.org/~/media/Oil-Spill-Prevention/spillprevention/r-and-d/inland/sunken-oil-technical-report-pp2.pdf (accessed on 13 January 2026).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.