Abstract

Climate change is widening the mismatch between water supply and water demand in urban areas, affecting both. Additionally, water demand is increasing due to population growth and economic development. Water allocation is a key component of sustainable urban water management and, unlike traditional approaches, must rely on a fit-for-purpose principle, where water is valued by its quality adequacy based on the use rather than by its source, with water reuse playing a central role in urban water resilience. This paper presents a novel framework, together with the step-by-step process for its application—the smart water allocation process (SWAP) for urban non-potable uses—and the developed software toolset to facilitate the decision-making process by urban managers, water utilities, and other stakeholders. It was developed within the context of a living lab to accelerate the innovation uptake. The demand–supply matchmaking and the plan module are comprehensively described and the SWAP results and their contribution to water resilience in Lisbon are discussed. Three water allocation alternatives were defined to implement different strategies, conservation, redundancy and reuse, in two green area clusters. Synergy with climate action funding was identified. The application of the SWAP enabled decision-making based on factual evidence and fostered intuitive understanding of the urban water resilience challenges.

1. Introduction

Access to water has always influenced the location and development of cities and other settlements around the world [1]. Climate change, and particularly the trend towards more frequent drought periods, rapid urbanisation, and the search for unlimited economic growth have been responsible for widening the mismatch between water supply and water demand [2,3]. Traditionally, water demand–supply gaps have been addressed through the application of supply-oriented measures, such as the construction of new surface storage and inter/intra basin transfer facilities or the increase in groundwater abstraction. However, freshwater availability to meet water demand is decreasing in many regions [4]. The situation is even more serious if the quality of water is also considered when assessing available freshwater resources. In a comparison of quantity and quality-induced scarcity with quantity-induced scarcity, Wang et al. [5] estimated a threefold increase in the number of global river basins facing water scarcity by 2050.

Many urban water systems are unfit to handle the combined effects of climate change, increased urbanization pressures, and governance challenges [6]. Expanding the water supply portfolio, integrating local freshwater sources and water reuse, allows for increased resilience in urban water systems by providing them with greater adaptability and flexibility [6,7]. The European Water Resilience Strategy, adopted in June 2025, includes water reuse as a key element to increase resilience to water-related challenges [8]. The 2024 Urban Wastewater Treatment Directive (UWWTD) recast mandates European countries to encourage the use of treated wastewater for all appropriate purposes, especially in water-stressed areas [9]. Conrad et al. [10] offers policy recommendations to address the implementation of water reuse at the European level.

The movement towards more sustainable water management is already underway. A good example of this is California (USA), where several cities have been developing their own water supply portfolio options appropriate for their geography, values, and urban characteristics [11]. These communities are adopting five key practices for ensuring future sustainability, namely, conservation and efficiency, water reuse, stormwater capture for water supply, desalination, and groundwater banking. To illustrate large-scale water reuse in an urban environment, it is worth mentioning the Madrid region (Spain), where reclaimed water (circa 126 Mm3 in 2020) is used for industrial uses, irrigating green areas and sports fields, street washing, aquifer recharge, and other environmental uses [12].

The transition towards sustainability is facilitated when viewed as a part of a continuous and interconnected series of strategies for the implementation of a long-term solution to challenges [13]. It is important to increase transparency in strategic planning and involve relevant stakeholders in the decision-making process and in the solutions’ implementation. In this context, living labs (LLs) create opportunities to accelerate environmental, social, and economic sustainability transitions by fostering co-innovation and testing solutions in real-world settings through the creation of synergies between different stakeholders as well as a diversity of potential benefits in terms of creativity, knowledge production, knowledge transfer, and user engagement, among other aspects [14]. Urban LLs tend to place more emphasis on co-creation based on a governance model [15], i.e., they can be very useful in guiding the cities to make significant and durable changes in the existing urban water systems. LLs are usually organised following the quadruple-helix model: (a) government, provides the challenge(s) to be tackled and case studies; (b) research, provides scientific guidance and methodological development; (c) industry, provides software and technological solutions, and data; and (d) civil society, provides feedback on the developed solutions (e.g., [16]).

Water allocation represents an important aspect in sustainable urban water management and, in contrast with the traditional approach, must rely on a fit-for-purpose principle, where water is valued by its quality adequacy based on the use rather than by its source and water reuse plays a key role for water resilience. Thus, a comprehensive framework is needed to support urban managers, water utilities, and other stakeholders in the decision process, integrating a coherent set of user-friendly tools designed to work together: (i) for formulating and assessing combinations of water supplies and demands towards water–energy–phosphorus balance (matchmaking); (ii) for assessing risks related to water reuse [17]; (iii) for managing chlorine residual within the reclaimed water distribution systems, a key risk management measure in urban water reuse [18,19]; and (iv) for ranking the candidate supply–demand combinations through quantitative metrics, covering the environmental, social, technoeconomic, and risk dimensions, and ultimately supporting the decision on the course of action in strategic planning.

A novel framework with such features was therefore developed and is herein presented, together with the step-by-step process for its application—the smart water allocation process (SWAP) for urban non-potable uses. It was developed within the B-WaterSmart Lisbon Living Lab, bringing together the urban manager, the developers (science and industry), and the society to accelerate innovation uptake. The demand–supply matchmaking and the plan module are comprehensively described and the SWAP results and their contribution to water resilience in Lisbon are discussed.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. The Lisbon Living Lab of the B-WaterSmart Project

The goal of B-WaterSmart, a European research project, was to accelerate the transition to water-smart economies and societies in coastal Europe by reducing freshwater use, improving water reuse, and increasing efficiency. From 2020 to 2024, systemic innovation was enabled through six living labs and their communities of practice (CoPs): Alicante (Spain), Bodo (Norway), East Frisia (Germany), Flanders (Belgium), Lisbon (Portugal), and Venice (Italy). These European cities and regions have in common the impact of climate change—water scarcity, for some, and flooding, for others—and the high water demand of their economies.

Through the B-WaterSmart project, innovative technologies, management practices, and smart data solutions were developed and demonstrated. One of the main outputs of this project is the Water-smartness Assessment Framework (WAF), designed to assist decision-makers and other stakeholders in strategic planning toward their vision of a water-smart society [20].

Following the Quadruple Helix Model, the B-WaterSmart Lisbon Living Lab (Lisbon LL) presented the following collaborative framework:

- Government—Lisbon Municipality (LM), with the role of LL owner, i.e., it was the stakeholder who “owned” the challenge to be addressed.

- Research—National Laboratory for Civil Engineering (LNEC), with the role of LL mentor, and the Institute of Social Sciences of the University of Lisbon.

- Industry—Águas do Tejo Atlântico (AdTA), the Lisbon’s wastewater utility; ADENE and Lisboa E-Nova, national and local agencies for energy efficiency, respectively; and Baseform, the registered trademark of BF Software, Ltd. (Lisbon, Portugal).

- Civil society was represented in the CoP through key stakeholders and replicators.

The solutions developed and demonstrated by the Lisbon LL were six smart digital applications (namely, a toolset composed of four interconnected tools for enabling smart water allocation and safe water reuse, a tool for certifying the climate readiness of buildings, and a tool for raising awareness on water management), and a water reclamation protocol for potable water reuse [21]. Within the B-WaterSmart Innovation Alliance, a strategic plan on smart water management in municipal irrigation was developed [22].

Regarding the smart water allocation framework, process, and tools, their development and testing followed the three phases of the systemic innovation process within an LL, i.e., exploration, experimentation, and evaluation of solutions [23], as presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Development phases of the smart water allocation framework and toolset.

2.2. Framework for Smart Water Allocation in Non-Potable Uses

2.2.1. Rationale

Smart water allocation was defined as a risk-based, fit-for-purpose approach for strategically selecting and assigning available water supplies to different water demands. Key aspects for smart water allocation are as follows:

- Alignment with strategic water management planning and with climate action and urban sustainability policies.

- Definition of water allocation alternatives based on strategies for water resilience.

- Establishment of non-potable water demand clusters, e.g., groups of green areas, to facilitate investment scheduling over time. Clusters should be defined with water reuse in mind and, therefore, be organized around existing or planned water resource recovery facilities (WRRFs).

- Safeguarding human health and the environment in the case of water reuse.

- Matching a fit-for-purpose water supply having in mind the demand requirements for water quality and quantity—the core of smart allocation.

- Rank different water allocation alternatives at a cluster level, and then, based on these rankings, prioritize which clusters in a city or region need the most attention for water management.

2.2.2. Smart Water Allocation Process

The Smart Water Allocation Process (SWAP) guides the decision-makers and other stakeholders in the stepwise application of the smart water allocation framework, and integrates a two-scale analysis, city level and cluster level. The step-by-step approach supports a clear definition of objectives and the exploration of multiple alternatives before selecting a solution. The two-level analysis allows for understanding first the large-scale water management challenges (city level) and then defining tailored interventions within sub-areas in the city (cluster level), for guiding a structured definition for the course of action to improve local water resilience (city level).

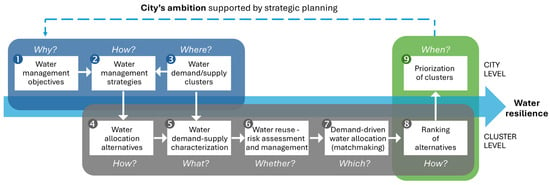

The SWAP is structured in nine steps, each one associated with a simple question (Figure 1), as follows:

Figure 1.

Smart water allocation process—SWAP.

City level:

- Objectives, the “why”—should be supported by strategic planning for smart water management (including climate scenario forecasts for the short, medium and long term) and should be aligned with relevant policies for urban sustainability.

- Strategies, the “how”—should outline the approaches to achieve the stated objectives.

- Clusters, the “where”—should reflect the spatial organization of the (existing and planned) water demands (e.g., irrigated green areas needed to fight the heat island effect and to improve the citizens’ quality of life) and water supplies.

Cluster level:

- 4.

- Alternatives, the “how”—should outline the specific course of action to implement the strategies.

- 5.

- Information, the “what”—should compile data from a variety of sources about the different water demand sites (including values on water consumption and fertilization) and water supplies (including values on volume, cost, phosphorus content, and water losses), as well as on the investments to be made.

- 6.

- Water reuse, the “whether”—should assess and manage risk to human health and the environment whenever water reuse is considered.

- 7.

- Demand–supply matchmaking, the “which”—should be demand-driven and use the following order from the water portfolio:

- (i)

- Select the water supply most directly associated with the alternative being analysed (e.g., select reclaimed water if the alternative is about water circularity).

- (ii)

- If water demand is not yet satisfied throughout the planning period, select other non-potable water supply to meet the remaining demand (e.g., groundwater).

- (iii)

- Drinking water should be the last supply to be considered for non-potable uses.

- 8.

- Ranking of alternatives, the “how”—should evaluate alternatives based on the smart water allocation metrics to rank them.

City level:

- 9.

- Prioritisation of clusters, the “when”—should compare the results of alternatives, ranking for each cluster, and then decide on investment scheduling for improving water resilience.

Figure 1 highlights the SWAP role for the development of a strategic plan for water resilience. Integrating SWAP into comprehensive and long-term strategic plans helps in ensuring the sustainable use of water resources and achieving cross-sectoral goals, e.g., climate adaptation results presentation:

- Understanding current and future performance and risks: diagnosis (including SWOT analysis) and prospective planning (SWAP steps 1 to 3);

- Defining and evaluating alternatives: definition of alternatives and evaluation of alternatives (current and prospective planning) (SWAP steps 4 to 8);

- Defining course of action: strategies to be implemented and monitoring progress (SWAP steps 8 to 9).

Section 4 demonstrates the SWAP application in the strategic planning of water management for non-potable uses in Lisbon; this section is organized according to the elements of the plan.

2.2.3. Smart Water Allocation Metrics

The Water-smartness Assessment Framework translates the “water-smart society” definition [24] into five strategic objectives (SOs) [20]; three of them are considered for assessing smart water allocation, as follows:

- SO A—Ensuring water for all relevant uses, using the A.1.3—Compliant reclaimed water metric (A.1—Safe and secure fit-for-purpose water provision criterion).

- SO B—Safeguarding ecosystems and their services to society, using the B.3.2—Carbon footprint metric (B.3—Resource efficiency criterion).

- SO C—Boosting value creation around water, using the C.3.2—Fertilizer production avoided and C.3.3—Reclaimed water used metrics (C.3—Resource recovery and use criterion).

Table 2 and Table 3 present the architecture (supplies, demands, and matchmaking alternatives) of the matchmaking framework, namely the variables and indicators for defining the matchmaking alternatives and for ranking them, respectively.

Table 2.

Variables and indicators used in defining the matchmaking alternatives.

Table 3.

Metrics and respective reference values used in the ranking of matchmaking alternatives.

2.3. Software Tools for Smart Water Allocation in Non-Potable Uses

As mentioned, a set of four interconnected tools—the Water–Energy–Phosphorus Balance Planning module (matchmaking tool), the Risk Assessment for Urban Water Reuse module, the Reclaimed Water Quality Model in the Distribution Network, and the Environment for Decision Support and Selection of Alternative Courses of Action (plan tool)—was designed to jointly provide a complete ability to quantitively and qualitatively match water supply to demand, while managing water volume, cost, energy, nutrients, and risk. These applications are in beta version and run in the Baseform online environment. Table 4 presents information on these tools and indicates the SWAP steps where they should be used.

Table 4.

Software toolset for smart water allocation and safe water reuse.

3. Case Study

Lisbon is the capital and most populous city of Portugal, with more than 570,000 inhabitants. Between 2021 and 2024, its population increased by 5.6% [29]. Every day, the daily number of people who commute to work or to school doubles [30]. Additionally, millions of tourists visit Lisbon every year: 8.52 million in 2024 [31].

Lisbon is the second-oldest European capital city, and it is located on the estuary of the Tagus River. Because the estuary water is too brackish to be potable, Lisbon suffered from a lack of drinking water over the centuries. When local groundwater sources were no longer sufficient to supply the population, the solution was to obtain water from distant locations: in the 18th century, by abstracting spring water from about 10 km away (Águas Livres spring in Belas, Sintra Municipality) and building the Águas Livres aqueduct; in the 20th century, by abstracting freshwater from about 100 km away (Castelo do Bode reservoir on the Zêzere River—a tributary of the Tagus River, Tomar Municipality) and building an extensive water distribution system.

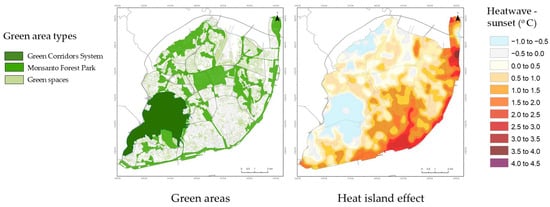

Lisbon is also the largest city of Portugal, with 100 km2 in total area. Its green areas include parks, gardens, remnants of farming lots, and roadway separators. Several of these green areas are connected through green corridors. These green corridors promote biodiversity, ecological connectivity and human well-being in the city, in addition to limiting the urban heat island effect [32]. Figure 2 illustrates the beneficial effect of green areas on air temperature during sunset; in general, heat islands tend to occur in the areas of Lisbon with lower vegetation density. This observation is in line with the conclusions of a study in the city of Porto (Portugal) [33].

Figure 2.

Green infrastructure and its influence on urban heat island in Lisbon (adaptation of [32]).

Lisbon faces water scarcity resulting from increased water demand (growing population and economy) and impacts of climate change (namely, drought, heat islands, and heat waves). The water exploitation index plus (WEI+) provides an overview on water scarcity, quantifying the renewable water resources and the water used for consumptive uses at a monthly time step [34]. Lisbon is in the sub-basin Tagus (Portuguese river basin district number 5), for which the WEI+ value calculated for 1930–2015 from July to September (0.77) indicates high water stress during the summer period [35].

Lisbon also faces long-term shifts in temperature and rain patterns associated with climate change. Through an analysis of rainfall and temperature records from 1864/65 to 2020/21, Espinosa et al. [2] observed an increase in severe and extreme drought conditions in the last 60 years.

Lisbon shares with other cities a long-term vision to tackle climate change. After joining the European Union (EU) Covenant of Mayors for Climate & Energy in 2009, the Lisbon City Council has signed other initiatives for climate action. Of note, is the participation in the C40 Cities Network. Several policies and strategies on climate adaptation and mitigation have been developed and implemented, namely the Municipal Climate Change Adaptation Strategy [36], Lisbon’s Drainage Master Plan [37], and the Lisbon Climate City Contract 2030 [38].

The development of blue-green infrastructures is a key aspect in the ongoing transition towards sustainability. To reduce the consumption of drinking water in non-potable uses, the Lisbon Municipality has implemented several measures, such as the renovation of irrigation networks, smart irrigation systems, the use of drought-tolerant landscaping (e.g., biodiverse meadows), and, more recently, water reuse for irrigation.

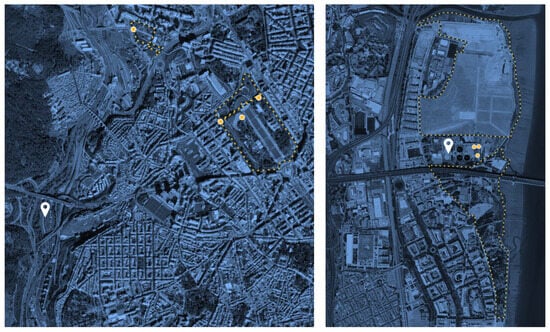

Two clusters were defined to exemplify smart water allocation within the Lisbon LL, representing different moments in the transition towards water resiliency. The Forest cluster integrates into the Monsanto Green Corridor which connects the city centre to the Monsanto Forest Park; irrigation is still conducted with drinking water. The River cluster is in the eastern part of the city and runs alongside the riverfront; water reuse is already implemented. These examples can be considered by decision-makers when analysing investments and operational measures for improving water management in non-potable uses. Table 5 describes the water demand sites and the water portfolio in each cluster.

Table 5.

Lisbon LL clusters—water demand sites and water portfolio.

Figure 3 presents the spatial layout of the two clusters used: the matchmaking tool screenshots present the location of the WRRF (white pins) and the green areas that compose each cluster (yellow dash lines); the Forest cluster (left) is located circa 5 km away from the Alcântara WRRF; and in the River cluster (right), the two parks encircle the Beirolas WRRF.

Figure 3.

Location of WRRFs, white pin, and green areas, yellow dashed lines in the Forest cluster (left) and the River cluster (right)—matchmaking tool screenshots on different scales.

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Understanding Current and Future Performance and Risks

Since funding water management is often challenging, fostering cross-sectoral collaboration can be a way forward to enhance urban water resilience. Thus, in the first two steps of SWAP, it is important to seek synergies between water management objectives (SWAP_step1) and strategies (SWAP_step2) with ongoing environmental policies. In Lisbon, significant potential has been identified in the association with climate action, as presented in Table 6. Table 7 refers to elements to be defined at the very beginning of strategic planning, namely the context (internal and external) analysis, timeline, and scenario.

Table 6.

Strategic alignment between climate action and urban water management in Lisbon.

Table 7.

Strategic planning of smart management of water in non-potable uses: Lisbon municipality.

The division of a territory in areas of analysis, i.e., clusters, facilitates the decision-making process regarding water management (SWAP_step 3). In this case study, two cluster were defined—the Forest and the River clusters, already presented in Section 3.

4.2. Defining and Evaluating Alternatives

The smart water allocation process proceeds at cluster level by studying and comparing possible intervention alternatives, which correspond to different combinations of actions designed to implement a given strategy (SWAP_step 4). The alternatives established to achieve the smart water management objectives presented in Table 6 are as follows:

- A0 Water Efficiency (to implement the Water Conservation strategy)—This baseline alternative aims to reduce water consumption by applying the “water efficiency” principle which, according to the European Water Resilience Strategy [8], is key and must come first. Emphasis is placed on actions that promote water conservation and efficient water use, such as renovating the irrigation network, using more efficient water devices and intelligent irrigation scheduling, and sealing ornamental lakes.

- A1 Water Variety (to implement the Water Redundancy strategy)—This alternative aims to reduce the use of drinking water for non-potable purposes by applying the “fit-for-purpose” principle (e.g., [43]). Emphasis is placed on actions that promote the use of local freshwater supplies (e.g., rehabilitation of boreholes and renewal of the aqueduct water distribution network).

- A2 Water Circularity (to implement the Water Reuse strategy)—This alternative aims to explore the value associated with reclaimed water by applying the “circulate products and materials” principle [44]. Emphasis is placed on actions that boost value creation around water and keep water in use as a product, such as water reuse for the irrigation and fertilization of urban green areas.

Next, in SWAP_step 5, information is compiled regarding water demand (e.g., green area irrigation), water supply (i.e., water portfolio), and the investments needed in each cluster. Often, it is necessary to work with information that is scattered, incomplete, siloed, or sensitive—either because the decision-making process is still ongoing or due to data management policy constraints. The information gathered during this step lays the ground for the strategic plan’s monitoring and review, to be carried out on a cyclical basis. For this reason, the matchmaking tool was designed to function as an information repository, in addition to its main purpose, which is to evaluate the application of alternatives in the different clusters.

The main assumptions considered in the matchmaking between water supply and demand in the two clusters in Lisbon are outlined below:

- Water demand—the result of water efficiency measures: it is assumed to be an annual reduction of 1% in water consumption, even though a higher volume of losses due to evapotranspiration and evaporation is expected (climate change impact).

- Water supply—severe 4-year drought scenario (2047/2050): (a) the application of a measure to restrict the supply of drinking water in 2049 and 2050, limiting supply to 50% of the amount made available in 2048, and (b) decreased productivity of boreholes and water springs, respectively, from 2048 to 2050 (75% of the amount made available in 2048).

- Water supply—risk management (Forest cluster): irrigation in the greenhouse is always done with groundwater (i.e., water reuse is excluded).

- Water supply—entry into operation of additional sources (Forest cluster): reclaimed water in January 2030, and spring water in January 2035.

- Water supply—water losses in distribution systems (to estimate abstracted or treated water volumes): 7% for drinking water, 0% for groundwater, 6% for spring water, and 5% and 0% for reclaimed water in Forest and River clusters, respectively.

- Costs: valuated with constant prices (2025, reference year).

The input data for demand–supply matchmaking refer to water (water supply volumes and green areas’ consumption-demand), phosphorus (concentration in water and fertilization needs), energy (consumption and carbon footprint), and costs (operational and investment). The matchmaking solutions are translated as time series of required monthly water volumes over a targeted period. Table 8 describes the data sets that were used for characterizing the Forest cluster (FC) and the River cluster (RC) in the matchmaking tool.

Table 8.

Water demand–supply matchmaking in Forest and River clusters: information description.

Whenever water reuse is considered as a potential water supply, it is necessary to assess the risk to human health and the environment for each green area (SWAP_step 6). To guide risk managers and stakeholders responsible for non-potable water uses through the often-complex process of licensing urban non-potable water reuse projects, a risk assessment framework was developed, based on relevant standardization and regulation.

In this case study, the use of reclaimed water with a Class-A quality (on a scale from A to D, A being the best quality water) was considered. This classification is established in the Portuguese Decree-Law 119/2019 [51] and is aligned with the classes proposed in the ISO standard 16075-2:2020 [52] and defined in the Regulation (EU) 2020/741 [53]. Ribeiro and Rosa [17] exemplify the application of the water reuse risk assessment framework in the irrigation of the Nações Norte park. The main risk control measure defined to ensure that the risk level remains low is the additional (low-level) disinfection [19].

SWAP_step 7 forms the core of the smart water allocation process, as it establishes for each green area the combination of available water supplies that better meet the demand in terms of performance (water volume, energy, and phosphorus), and cost. The water demand–supply matchmaking framework does not address mixture of waters of different qualities to better fit the purpose. Candidate water supplies should have the minimum quality compatible for the purpose. The basic idea of the water supply–demand matchmaking is simple—use a fit-for-purpose water source whenever justifiable. The matchmaking tool (framework and software application) provides a simple-to-use analysis of candidate combinations of one, two, or more supplies for satisfying non-potable water demands. It allows the calculation of metrics related to sustainability (environmental and economic), circular economy (water reuse and phosphorus valorisation), and climate change (carbon neutrality), based on input monthly (or other time interval) variables of water volume, energy, phosphorus and other nutrients, and cost.

The alternatives that embody the different strategies are defined through the selection order of the water supplies from the existing and planned water portfolio. For instance, if rainfall independence is to be increased, reclaimed water should be considered as the first option to meet the demand. Table 9 presents the application of the alternatives in terms of the water portfolio considered for each cluster. As water reuse is already in place in the River cluster, alternatives A0 and A2 are considered in combination.

Table 9.

Application of alternatives in clusters.

Matching available water sources with water demand in each cluster is done in a simple way. First, the green area to be analysed first is selected (e.g., it may be because it is intended to ensure that it is supplied by a particular water supply). In the Forest cluster, for example, Eduardo VII Park was selected first because the historic greenhouse is to be irrigated with groundwater (risk management). Next, one or more water supplies are selected until the volume demand is met throughout the planning period. Then, the same procedure for choosing water supplies is applied to the other green areas that make up the cluster. The water supply–demand alternative combinations are assessed using quantitative metrics of performance, along a pre-defined time scale (present to planning horizon).

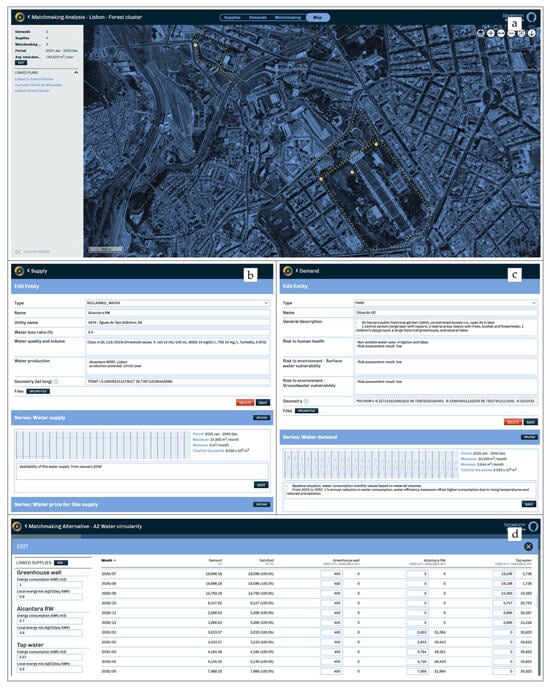

To guide water demand planners and decision makers in urban management, municipal, and water utility contexts, a user-friendly software tool was developed. Figure 4 presents the four tabs of the Water–Energy–Phosphorus Balance Planning module tool (version 1.0): (a) map showing the location of green areas and water supply points; (b) supplies tab for providing information on, among others, water availability, price and P content; (c) demands tab for providing information on, among others, water and P-fertilisation needs; (d) matchmaking tab for selecting available water supplies to meet demand in a given green area, for each alternative.

Figure 4.

Screenshots of the four tabs of the matchmaking tool: (a) Map—geo-reference of the green areas and water supplies that constitute the cluster; (b) Supply—information on volume (availability), cost and P content for each water supply; (c) Demand—information on volume (demand) and P fertilisation for each green area; (d) Matchmaking—demand satisfaction based on the portfolio established for each alternative—the software permanently updates and displays the still available water supply, as well as the satisfied/mapped demands and the unmapped demands.

Water-smart allocation for urban non-potable uses implies the assessment and ranking of planning alternatives through objective-guided metrics. The impact of each alternative should be quantified over time. In SWAP_step 8, the water supply–demand matchmaking is evaluated through the metrics, and respective reference values, presented in Table 3. The risk evaluation results from the water reuse risk assessment tool and, if applicable, from the water quality modelling in the reclaimed water distribution system.

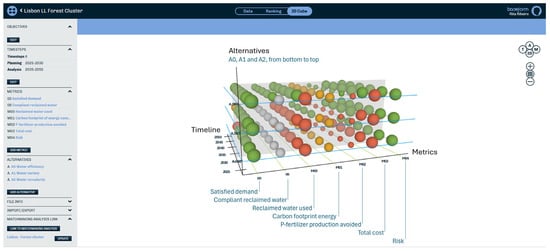

The ranking of the alternatives is done automatically using the Environment for Decision Support and Selection of Alternative Courses of Action software tool (version 1.0). This tool, an intuitive numerical and visual decisional environment, enables water demand planners and other decision makers to easily comprehend the decisional problem involved in prioritizing the alternatives. Figure 5 presents a screenshot of the three-dimensional view of the alternatives’ evaluation in the planning tool. A colour code is applied to provide information about the evaluation results (i.e., “good” is green, “fair” is orange, and “poor” is red). This software tool also presents the evaluation results in tables.

Figure 5.

Plan tool: 3D comparison of Forest cluster alternatives (software screenshot).

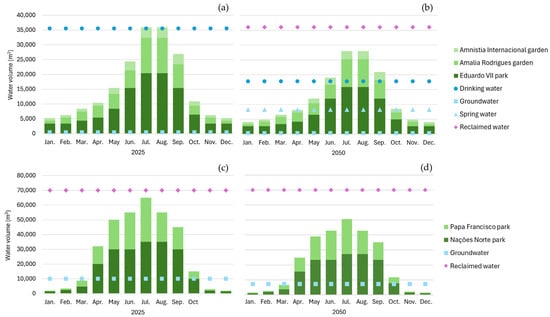

The impact of climate change in Lisbon, particularly on its green areas, is analysed in the strategic plan through the prolonged drought scenario. Figure 6 presents the supply–demand balance for 2025 and 2050—the 2025 values are based on the water supply potential from different sources and on water consumption in the green areas, and the 2050 values correspond to planning projections. In the Forest cluster, it is anticipated that in July and August 2050 the use local freshwater supplies (alternative A1), even with drinking water, will not be sufficient to meet water demand. Only the water reuse alternative (A2) provides water security in this scenario. Figure 7 presents the distribution of the water supplies in each alternative through the planning timeline. In the River cluster, the use of groundwater is considered for redundancy and cost (alternative A1), explaining the increase in its contribution from 2025 to 2035; in 2050, the drought limits its availability.

Figure 6.

Water supply–demand balance at the beginning and end of the planning period: Forest cluster in (a) 2025 and (b) 2050; River cluster in (c) 2025 and (d) 2050.

Figure 7.

Distribution of the water supplies sources for each alternative over the planning timeline: (a) Forest cluster; (b) River cluster.

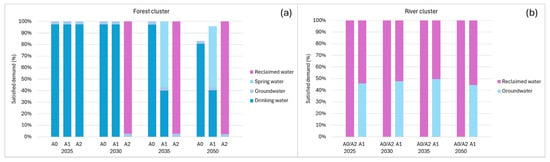

As mentioned, the Environment for Decision Support and Selection of Alternative Courses of Action software tool (i.e., the plan tool) can present the evaluation results of the ranking metrics in two types of formats: in the form of a cube (Figure 5) or through tables. Table 10 and Table 11 present the evaluation results of matchmaking alternatives in the Forest and River clusters, respectively. The values correspond to the annual average calculated for the ranking metrics; again, a colour code is applied to provide information about the result (i.e., “good” is green, “fair” is orange in a light grey cell, and “poor” is red in a dark grey cell). The planning timeline was hypothesised in Table 7; the year 2050 corresponds to the end of a severe drought period (resilience scenario). As water reuse already occurs in the River cluster, alternatives A0 (baseline) and A2 (circularity) are jointly assessed.

Table 10.

Lisbon LL Forest cluster: alternatives evaluation.

Table 11.

Lisbon LL River cluster: alternatives evaluation.

Below are some comments on the evaluation of the smart water allocation alternatives applied in Lisbon LL:

- Satisfied demand—This metric reflects a critical aspect for demand-driven water allocation: maintaining healthy vegetation is crucial because it limits the urban heat island effect through shading and evapotranspiration. According to the conditions considered in the strategic plan, in the Forest cluster, the use of additional freshwater sources (alternative A1) is not sufficient to meet the demand for non-potable water in a situation where drinking water restrictions may be applied to the irrigation of green areas—resilience scenario (prolonged drought). As expected, water reuse (alternative A2) is the only water supply that ensures water resilience in a severe drought scenario.

- Reclaimed water used—Because water reuse is a key element in increasing resilience against climate change, the smart water allocation evaluation system includes four metrics to analyse it. This first metric indicates the relative importance of water reuse in meeting demand. In the case study, it is possible to fully meet the water demand through reuse. However, the use of groundwater for greenhouse irrigation is always maintained for risk management reasons. This is why water reuse in the Forest cluster represents 98% of total consumption in 2050 (Alternative A2).

- Risk—Safeguarding health and environmental protection is the basic condition for water reuse; thus, risk assessment is a prerequisite for the design and establishment of a water reuse project. Whenever water reuse is considered, risk control measures are integrated in the irrigation system and in the green areas to ensure that risks are kept at a low level—namely, Class-A quality [51,52,53] is ensured at the sprinkler outlets and other devices. The other supplies of water pose a low risk to human health and the environment.

- Compliant reclaimed water—Post-disinfection (a measure to control the risk associated with water reuse) by adding chlorine to the irrigation network, whenever justified by its length, is included in the risk management system defined through risk assessment. Therefore, the quality of reclaimed water is expected to be ensured at the points of application (e.g., at the sprinklers’ outlet).

- Phosphorus fertilizer production avoided—This metric refers to exploiting the fertilizing potential of reclaimed water. In the assumption made in Table 9, the green area soils are rich in phosphorus, and half the dose of fertilizer recommended in general lawn fertilisation requirements was considered. For that reason, it appears that P is supplied in quantities greater than necessary. This possibility should be clarified through a thorough analysis of soil conditions. In any case, the new European legislation [9] will require the phosphorus concentration at the wastewater treatment plants’ effluent not to exceed 0.5 g/m3, i.e., 1/6 of the value currently considered.

- Carbon footprint consumed energy—Good energy performance can only be achieved when using spring water, as this is sent to Lisbon through a network built in the 18th century (Sistema das Águas Livres), which operates through gravitational flow. The carbon footprint of reclaimed water production is evident in the application of alternative A1 in the River cluster: as groundwater supply is selected first (constant value until the scarcity scenario) and demand decreases over the years due to water efficiency measures, the overall carbon footprint decreases because the contribution of reclaimed water is lower; in 2050, as a result of a 25% reduction in borehole productivity, water reuse becomes more prevalent and, thus, the energy consumption associated with water supply to this cluster also increases. Again, this is likely to improve soon due to the mandatory energy neutrality in wastewater treatment [9].

- Total cost—The drinking water tariff paid in Lisbon by commercial customers in 2025 (2 EUR/m3, Table 9) was used as a reference value for the total cost analysis; based on this value, the results associated with this criterion are classified as “poor.” As negotiations on reclaimed water prices are ongoing and the supply of spring water is still under consideration, it was decided to assign them a price related to the drinking water tariff (25% and 12.5% of this tariff for reclaimed water and spring water, respectively). The value below which results are considered “good” is also related to the drinking water tariff: 1 EUR/m3 or 50% of the tariff. Regardless of operating costs, the rehabilitation of the irrigation network in some green areas (baseline alternative and measure integrated into the other alternatives) contributes significantly to the total cost of water used in the non-potable urban areas considered. It is interesting to note that, since the available volume of spring water does not allow for the complete replacement of drinking water (Forest cluster), the total cost recorded in Alternative A1 is higher than that recorded with water reuse, despite the latter having additional costs (post-chlorination and quality monitoring). Once again, the expected decrease in the productivity of freshwater sources requires greater use of the remaining source—drinking water. In the case of the River cluster, the higher value observed in alternative A2 results from the fact that the reclaimed water price is higher than for groundwater.

4.3. Defining Course of Action

At the final step of the Smart Water Allocation Process—SWAP_step 9, the water demand planners and decision makers in urban management, municipal, and water utility contexts are supposed to make decisions about investment values and the scheduling required to achieve the desired level of water resilience. The assessment and ranking of alternatives through the objective-guided metrics (SWAP_step 8) within the clusters is the basis to plan investments to be made in the city over time.

In this case study, the obvious option is to improve the water allocation in non-potable uses in the Forest cluster, since water reuse is already in place in the River cluster. The SWAP results can be used by the Lisbon Municipality technicians to build business cases for improving the resilience to climate. In both clusters, the strategic plan should be reviewed every five years to verify demand and supply scenarios.

The effort invested in compiling information for smart water allocation and defining the analytical assumptions sets the foundation for an effective transition towards water resilience. In fact, it enables a bridge to be created between different municipal departments and sustainability policies, as well as relevant stakeholders in the context of the urban water cycle. Clear and updated information is also necessary for supporting communication with citizens and municipal staff regarding water scarcity.

5. Conclusions

This study presents an innovative framework for smart water allocation in non-potable urban uses, to tackle urban water resilience through the application of three good water management practices, namely, (a) fit-for-purpose use; (b) water reuse; and (c) redundancy. This framework aims to support water management strategic planning through the study and comparison of possible intervention alternatives, combining the performance, cost, and risk dimensions in the analysis. The framework is applied through a nine-step, two-level process—the SWAP. To foster the use of this framework, a toolset of four user-friendly applications was designed to facilitate the smart water allocation in non-potable uses by urban managers, water utilities, and other stakeholders. This article describes the application of the supply–demand matchmaking and the planning tools to meet water demand in a set of green areas in Lisbon.

The main advantages of applying the presented smart water allocation framework are as follows:

- Greater ease in understanding and assessing the dimensions involved (performance, cost, and risk) in using different water sources for non-potable uses and how the application of different water resilience strategies impacts adaptation to climate change—e.g., the use of water sources more independent of rainfall to support the implementation of green structures to combat the heat island effect), as well as their mitigation—i.e., it is important to consider the energy consumption involved in water treatment and distribution, depending on its source.

- Promoting stakeholder engagement by making the decision-making process more transparent, particularly in terms of urban water management strategic planning.

- Evidence-based decision-making, which requires a serious effort to compile and manage information from various sectors and entities. The fact that the matchmaking tool can also function as an information repository can help combat data silos and a lack of communication between different sectors of the same entity (e.g., between the green areas management sector and the sector involved in climate action).

Further research is needed to better characterize the water circularity alternative, valuing the recovery of resources present in water (e.g., phosphorus recovery in WRRF) so that the comparison of alternatives is based on a more accurate cost–benefit analysis.

The use of the living lab approach was a key aspect for the framework development. The two main lessons learned are:

- The LL quadruple-helix model leverages the systematic integration of scientific knowledge in an iterative, challenge-driven way to produce practical outcomes. Lisbon LL accelerated co-creation by engaging from the outset: academia (conceptual and methodological development), (defining challenges and validating solutions), industry (software development and data provision), and society (feedback and discussion).

- Living labs provide the contextual insights essential to handle urban challenges. To foster water resilience in a city and across diverse regions, it is essential to establish adaptive planning methods that respond to shifting conditions through regular supply-and-demand verification, by recalibrating actions across different timeframes. From its inception, the Lisbon LL prioritized the replicability and scalability of the smart water allocation framework, leading to more systematic analysis and the development of user-friendly tools.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.R. and M.J.R.; methodology, R.R., M.J.R. and C.S.; data collection, P.T.; validation, P.T. and R.R.; writing—original draft preparation, R.R. and P.T.; writing—review and editing, M.J.R., R.R., P.T., C.S. and C.F.; fund raising, M.J.R., C.S. and C.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant agreement No. 869171 (B-WaterSmart).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to give special thanks to Diogo Andrade, Diogo Vitorino, and Sérgio Teixeira Coelho from Baseform for developing the smart water allocation software toolset, and for contributing to the framework discussion. The authors also acknowledge other B-WaterSmart partners from the Lisbon LL and the participants of the Community of Practice for the fruitful discussion about water challenges in the context of climate change and important considerations for overcoming them. We also acknowledge the valuable comments made by the three reviewers.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AdTA | Águas do Tejo Atlântico |

| CAPEX | Capital Expenditures |

| CoP | Community of Practice |

| EPAL | Empresa Portuguesa das Águas Livres |

| FC | Forest Cluster |

| LL | Living Lab |

| LM | Lisbon Municipality |

| LNEC | Laboratório Nacional de Engenharia Civil (National Laboratory for Civil Engineering) |

| OPEX | Operational Expenditures |

| RC | River Cluster |

| SO | Strategic Objective |

| SWAP | Smart Water Allocation Process |

| SWOT | Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, Threats |

| WAF | Water-smartness Assessment Framework |

| WRRF | Water Resource Recovery Facility |

References

- Angelakis, A.N.; Capodaglio, A.G.; Kumar, R.; Valipour, M.; Ahmed, A.T.; Baba, A.; Güngör, E.B.; Mandi, L.; Tzanakakis, V.A.; Kourgialas, N.N.; et al. Water Supply Systems: Past, Present Challenges, and Future Sustainability Prospects. Land 2025, 14, 619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espinosa, L.A.; Portela, M.M.; Matos, J.P.; Gharbia, S. Climate change trends in a European coastal metropolitan area: Rainfall, temperature, and extreme events (1864–2021). Atmosphere 2022, 13, 1995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nel, J.B.; Mativenga, P.T.; Marnewick, A.L. A framework to support the selection of an appropriate water allocation planning and decision support scheme. Water 2022, 14, 1854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gleick, P.H.; Cooley, H. Freshwater scarcity. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2021, 46, 319–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Bodirsky, B.L.; Rijneveld, R.; Beier, F.; Bak, M.P.; Batool, M.; Droppers, B.; Popp, A.; van Vliet, M.T.H.; Strokal, M. A triple increase in global river basins with water scarcity due to future pollution. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capodaglio, A.G. Urban Water Supply Sustainability and Resilience under Climate Variability: Innovative Paradigms, Approaches and Technologies. ACS ES&T Water 2024, 4, 5185–5206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quon, H.; Jiang, S. Decision making for implementing non-traditional water sources: A review of challenges and potential solutions. npj Clean Water 2023, 6, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission: European Water Resilience Strategy. Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, The Council, The European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions, COM/2025/280 Final. 2025. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A52025DC0280&qid=1750857768458 (accessed on 29 October 2025).

- Directive (EU) 2024/3019 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 27 November 2024 concerning urban wastewater treatment (recast). 2024. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/dir/2024/3019/oj/eng (accessed on 17 October 2025).

- Conrad, A.; Schieren, J.; Cardoso, M.A.; Rosa, M.J.; Xevgenos, D.; Bilyaminu, A.; Stroutza, D. Accelerating Water Smartness by Successfully Implementing the EU Water Reuse Regulation (2020/741). Policy Brief, B-WaterSmart. 2024. Available online: https://b-watersmart.eu/download/b-watersmart-policy-brief-accelerating-water-reuse/# (accessed on 29 October 2025).

- Luthy, R.G.; Wolfand, J.M.; Bradshaw, J.L. Urban water revolution: Sustainable water futures for California cities. J. Environ. Eng. 2020, 146, 04020065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- del Villar, A.; García-López, M. The potential of wastewater reuse and the role of economic valuation in the pursuit of sustainability: The Case of the Canal de Isabel II. Sustainability 2023, 15, 843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, M.; Koebele, E.; Deslatte, A.; Ernst, K.; Manago, K.F.; Treuer, G. Towards urban water sustainability: Analyzing management transitions in Miami, Las Vegas, and Los Angeles. Glob. Environ. Change 2019, 58, 101967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouwma, I.; Wigboldus, S.; Potters, J.; Selnes, T.; Van Rooij, S.; Westerink, J. Sustainability transitions and the contribution of living labs: A framework to assess collective capabilities and contextual performance. Sustainability 2022, 14, 15628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Innella, C.; Ansanelli, G.; Barberio, G.; Brunori, C.; Cappellaro, F.; Civita, R.; Fiorentino, G.; Mancuso, E.; Pentassuglia, R.; Sciubba, L.; et al. A methodological framework for the implementation of urban living lab on circular economy co-design activities. Front. Sustain. Cities 2024, 6, 1400914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esashika, D.; Masiero, G.; Mauger, Y. Living labs contributions to smart cities from a quadruple-helix perspective. J. Sci. Commun. 2023, 22, A02. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, R.; Rosa, M.J. The Role of Scenario-Building in Risk Assessment and Decision-Making on Urban Water Reuse. Water 2024, 16, 2674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, J.; Mesquita, E.; Ferreira, F.; Rosa, M.J.; Viegas, R.M.C. Identification and modelling of chlorine decay mechanisms in reclaimed water containing ammonia. Sustainability 2021, 13, 13548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, J.; Mesquita, E.; Ferreira, F.; Figueiredo, D.; Rosa, M.J.; Viegas, R.M. Modelling Chlorine Decay in Reclaimed Water Distribution Systems—A Lisbon Area Case Study. Sustainability 2023, 15, 16211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, C.; Cardoso, M.A.; Rosa, M.J.; Alegre, H.; Ugarelli, R.; Bosco, C.; Raspati, G.; Azrague, K.; Bruaset, S.; Damman, S.; et al. Final Version of the Water-Smartness Assessment Framework. B-WaterSmart Deliverable D6.3. 2023. 276p. Available online: https://b-watersmart.eu/download/final-version-of-the-water-smartness-assessment-framework-pdf-deliverable-6-3/ (accessed on 16 October 2025).

- Rosa, M.J.; Ribeiro, R.; Viegas, R.; Oliveira, M.; Teixeira, P.; Figueiredo, D.; Lourinho, R.; Mendes, R.; Coelho, S.T.; Vitorino, D.; et al. B-WaterSmart Solutions for Lisbon—Summary Report. B-WaterSmart Deliverable D2.15. 2024. 43p. Available online: https://b-watersmart.eu/download/b-watersmart-solutions-for-lisbon-d2-15/ (accessed on 16 October 2025).

- Smart Water Management in Lisbon’s Municipal Irrigation System—Strategic Plan 2025–2050. 2025; (Unpublished document, in Portuguese).

- Evans, P.; Schuurman, D.; Ståhlbröst, A.; Vervoort, K. Living Lab Methodology Handbook; U4IoT Consortium: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017; Available online: https://zenodo.org/records/1146321 (accessed on 16 October 2025).

- Damman, S.; Schmuck, A.; Oliveira, R.; Koop, S.S.H.; Almeida, M.C.; Alegre, H.; Ugarelli, R.M. Towards a water-smart society: Progress in linking theory and practice. Util. Policy 2023, 85, 101674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Water Europe Marketplace. Product: Water-Energy-Phosphorous Balance Planning Module. 2024. Available online: https://mp.uwmh.eu/d/Product/55 (accessed on 16 October 2025).

- Water Europe Marketplace. Product: Risk Assessment for Urban Water Reuse Module. 2024. Available online: https://mp.uwmh.eu/d/Product/67 (accessed on 16 October 2025).

- Water Europe Marketplace. Product: Reclaimed Water Distribution Network Water Quality Model. 2024. Available online: https://mp.uwmh.eu/d/Product/51 (accessed on 16 October 2025).

- Water Europe Marketplace. Product: Environment for Decision Support and Alternative Course Selection. 2024. Available online: https://mp.uwmh.eu/d/Product/66 (accessed on 16 October 2025).

- Portrait of Municipalities—Lisbon. Available online: https://retratos.pordata.pt/populacao/lisboa (accessed on 14 October 2025). (In Portuguese)

- Lisbon. Available online: https://www.upperprojecteu.eu/cities-regions/lisbon/ (accessed on 14 October 2025).

- Lisbon Tourism Statistics. Available online: https://roadgenius.com/statistics/tourism/portugal/lisbon/#Lisbon_Tourism_Statistics_2024_International_and_Domestic (accessed on 14 October 2025).

- Lopes, A.; Oliveira, A.; Correia, E.; Reis, C. Identification of Urban Heat Islands and Simulation for Critical Areas in the City of Lisbon. Lisbon Municipality. 2020. Available online: https://www.lisboa.pt/fileadmin/portal/temas/ambiente/alteracoes_climaticas/ondas_calor/IdentificacaoICU_ATUAL_Fase1.pdf (accessed on 17 October 2025). (In Portuguese)

- Lopes, H.S.; Vidal, D.G.; Cherif, N.; Silva, L.; Remoaldo, P.C. Green infrastructure and its influence on urban heat island, heat risk, and air pollution: A case study of Porto (Portugal). J. Environ. Manag. 2025, 376, 124446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sondermann, M.N.; de Oliveira, R.P. Using the WEI+ index to evaluate water scarcity at highly regulated river basins with conjunctive uses of surface and groundwater resources. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 836, 155754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assessment of Water Availability by Water Body and Application of the WEI+ Scarcity Index, with a View to Complementing the Assessment of the Status of Water Bodies—Final Report. 2023. Available online: https://apambiente.pt/sites/default/files/_SNIAMB_Agua/DRH/PlaneamentoOrdenamento/PGRH/2022-2027/APA_WEIPLUS_RelatorioFinal_Dez2023.pdf (accessed on 17 October 2025). (In Portuguese)

- Lisbon Municipal Strategy for Adaptation to Climate Change. 2017. Available online: https://www.lisboa.pt/fileadmin/portal/temas/ambiente/documentos/EMAAC_2017.pdf (accessed on 17 October 2025). (In Portuguese)

- Lisbon General Drainage Plan 2016–2030. 2015. Available online: https://planodrenagem.lisboa.pt/sobre-o-plano (accessed on 17 October 2025). (In Portuguese)

- Lisbon Municipality. Lisbon’s Climate City Contract. 2024. Available online: https://netzerocities.app/resource-4423 (accessed on 17 October 2025).

- C40 Cities. C40 Commitment. Available online: https://www.c40.org/what-we-do/raising-climate-ambition/1-5c-climate-action-plans/ (accessed on 17 October 2025).

- C40 Cities, Water Safe Cities Accelerator. Available online: https://www.c40.org/accelerators/water-safe-cities/ (accessed on 17 October 2025).

- Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/2030agenda (accessed on 17 October 2025).

- European Commission: Directorate-General for Climate Action. Going Climate-Neutral by 2050—A Strategic Long-Term Vision for a Prosperous, Modern, Competitive and Climate-Neutral EU Economy. 2019. Available online: https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2834/02074 (accessed on 17 October 2025).

- International Water Association. The Journey to Water-Wise Cities. Available online: https://www.iwa-network.org/water-wise-cities (accessed on 17 October 2025).

- Ellen MacArthur Foundation. Circulate Products and Materials. Available online: https://www.ellenmacarthurfoundation.org/circulate-products-and-materials (accessed on 17 October 2025).

- Bigelow, C.A.; Tudor, W.T.; Nemitz, J.R. Facts About Phosphorus and Lawns. Purdue Agronomy-Turf Science, AY-334-W. N.d. Available online: www.agry.purdue.edu/turf (accessed on 17 October 2025).

- Águas de Portugal. Sustainability Report 2024. Available online: https://www.adp.pt/sustentabilidade/Documentos%20Partilhados/Sustainable%20Reports/AdP%20Sustainability%20Report%202024.pdf (accessed on 3 December 2025).

- Areosa, I.; Martins, T.A.; Lourinho, R.; Batista, M.; Brito, A.G.; Amaral, L. Treated wastewater reuse for irrigation: A feasibility study in Portugal. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 954, 176698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowtricity. Real Time Live Emissions from Energy Production by Country—Portugal. Available online: https://www.nowtricity.com/country/portugal/ (accessed on 3 December 2025).

- EPAL. Sales Prices of Water in Lisbon. Available online: https://www.epal.pt/EPAL/en/menu/customers/tariff/water (accessed on 3 December 2025).

- Expósito, A.; Lorenzo Lopez, A.M.; Berbel, J. How much does reclaimed wastewater cost? A comprehensive analysis for irrigation uses in the European Mediterranean context. Water Reuse 2024, 14, 434–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Decree-Law 119/2019 on Water Reuse. 2019. Available online: https://diariodarepublica.pt/dr/detalhe/decreto-lei/119-2019-124097549 (accessed on 17 October 2025). (In Portuguese)

- ISO 16075-2:2020; Guidelines for Treated Wastewater Use for Irrigation Projects. Part 2: Development of the Project, 2nd ed. International Standards Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/73483.html?browse=tc (accessed on 17 October 2025).

- Regulation (EU) 2020/741 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 25 May 2020 on Minimum Requirements for Water Reuse. 2020. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reg/2020/741/oj/eng (accessed on 17 October 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.