Abstract

Understanding how different pools of sediment organic carbon (OC) are associated with trace metals is essential for interpreting biogeochemical processes in small freshwater ecosystems. This study examines spatial and interannual patterns of total organic carbon (TOC), water-extractable organic carbon (WEOC), and cadmium (Cd) in sediments collected from streams, natural ponds, and drying ditches across three contrasting regions of Lithuania during 2022–2024. TOC and WEOC exhibited pronounced spatial gradients and a marked increase in 2023, while Cd showed a similar but more moderate temporal response. Correlation analysis, principal component analysis, regression modelling, and structural equation modelling consistently indicated that WEOC is more strongly associated with sediment Cd concentrations than bulk TOC. The results suggest that TOC influences Cd distribution primarily indirectly, through its control on the water-extractable OC pool. Multivariate analyses revealed a dominant organic–metal association gradient shared by TOC, WEOC, and Cd, as well as a secondary axis reflecting partial geochemical independence of Cd. These findings highlight the functional relevance of WEOC as an interface between sediment organic matter and Cd accumulation in small freshwater systems. Incorporating WEOC into sediment monitoring may improve interpretation of trace-metal patterns under conditions of hydrological variability.

1. Introduction

1.1. Small Waterbodies as Components of the Global Carbon Cycle

Inland waters—including lakes, ponds, streams, and drainage ditches—represent critical nodes in the global carbon cycle, despite covering a relatively small fraction of the Earth’s surface. Contemporary global syntheses estimate OC burial rates in lake sediments at 0.15–0.25 Pg C yr−1, comparable to the total carbon flux buried in ocean sediments [1,2,3]. However, the efficiency with which carbon is incorporated into sediments varies widely with climatic conditions, hydrological regimes, and anthropogenic pressures. Numerous studies over recent decades have demonstrated that climate warming, changes in runoff, and increasing external organic inputs accelerate mineralization processes, thereby reducing the proportion of carbon that remains stably sequestered in sediments [4,5,6].

1.2. Climatic and Hydrological Drivers of Carbon Accumulation

Water temperature is one of the key climatic controls governing both primary production and microbial decomposition in aquatic systems [4,6]. Rising temperatures promote enhanced mineralization, particularly in surface sediment layers, while seasonal stratification creates anoxic conditions favourable to carbon preservation.

Regional studies in Northern and Central Europe indicate that, in temperate climates, temperature seasonality alone explains up to 70% of the variation in sedimentary OC burial rates [3,6].

In addition to temperature, the so-called browning phenomenon—an increase in dissolved organic carbon (DOC) due to enhanced allochthonous inputs from catchments—has become a dominant trend across boreal and Baltic regions [7,8]. This DOC enrichment, observed since the 1980s, alters light penetration, redox conditions, and microbial activity [9]. WEOC represents a mobile and chemically reactive fraction of organic carbon released from sediments and soils. It is enriched in low-molecular-weight and functionalised organic compounds containing carboxyl, phenolic, and hydroxyl groups, which are capable of forming stable complexes with divalent metal ions such as Cu, Zn, Pb, and Cd. Through complexation, WEOC can increase metal solubility in pore waters while simultaneously promoting metal association with organic-rich sediment matrices, depending on local redox conditions, pH, and mineral interactions. As a result, WEOC influences metal distribution and accumulation patterns in sediments without necessarily implying enhanced metal mobility or release to the overlying water column [10,11,12].

However, in small freshwater systems, disentangling these drivers remains challenging due to limited site-specific hydroclimatic data.

1.3. Landscape Controls and Land-Use Impacts

The relationship between land use and the quality of sedimentary OC is well established [13,14]. Forested and wetland catchments tend to produce sediments enriched in humic, stable carbon fractions, whereas agricultural and urban areas supply more labile, easily decomposable organic compounds that enhance CO2 emissions during mineralization.

In regions characterized by extensive agricultural drainage—such as central and northern Lithuania—small artificial waterbodies and drainage ditches often act as biogeochemical filters, intercepting particulate organic matter but simultaneously facilitating carbon losses through methane emission and DOC export [15,16,17].

Modern carbon-balance models, such as the dynamic dissolved and mineral-associated soil organic carbon (DMSOC) framework [3], integrate both deposition and mineralization processes, emphasizing landscape and hydrodynamic context as primary regulators of OC storage.

1.4. The Baltic Region: Spatial Patterns and Environmental Risks

The Baltic region represents an ecologically sensitive zone due to its dense network of small ponds, ditches, and drainage systems combined with strong agricultural and industrial pressure [18,19].

Sediment surveys from Lithuania, Poland, and Latvia reveal substantial accumulation of both OC and trace metals—particularly Cd and Pb—in near-shore and inland depositional environments [16,20,21,22,23].

In the southeastern Baltic region, Cd concentrations in sediments reach 1.2–2.4 mg kg−1, exceeding commonly applied ecological risk threshold values for Cd in freshwater sediments (typically ~0.6–1.0 mg kg−1, depending on guideline framework) [24]. Conversely, protected catchments in northern Lithuania (e.g., Lake Plateliai area) display elevated OC content but relatively low metal concentrations, typically below ~0.5 mg kg−1 for Cd in sediment [25].

These contrasts illustrate a clear spatial gradient across natural–agricultural–transboundary landscapes, reflecting differences in land-use intensity and hydrological connectivity.

1.5. Coupling Between OC and Heavy Metals

Organic matter in sediments is a key geochemical regulator of metal association, complexation, and immobilization—particularly for Cd, Pb, and Cu [9,26,27]. Humic acids and organo-mineral colloids form stable chelates with metals, decreasing their association while modulating bioavailability as redox and pH conditions change [28,29].

Field and laboratory studies suggest that up to 60% of total Cd and Pb in small-pond sediments can be bound to the organic fraction [30,31]. Yet warming and oxidation of surface sediments may remobilize these elements, creating secondary pollution risks [27,32].

1.6. Knowledge Gaps in Small Ponds and Drainage Systems

While large ponds of the Baltic region have been extensively studied, small waterbodies—streams, natural ponds, and artificial drainage ditches—remain poorly characterized [25,33].

Despite their limited surface area, they contribute disproportionately to carbon and metal fluxes at the catchment scale. Small ponds, due to their shallow depth, short water residence time, and high catchment-to-volume ratio, are strongly affected by inputs from surrounding watersheds, which often carry significant amounts of organic matter, nitrogen, and phosphorus, particularly in agricultural landscapes. Despite this strong external influence, research indicates that metabolic carbon processes in these ponds occur at a high rate, making them important for transforming organic matter, retaining DOC, and storing carbon in sediments. Studies in Lithuania and Poland demonstrate that OC and Cd concentrations in sediments of small ditches are two- to three-fold higher than in natural ponds due to surface runoff from agricultural soils [17,20,21,34,35,36].

Hydrological regulation and seasonal flow variability further control the redistribution of suspended organo-mineral particles [14,15].

WEOC is widely recognized as a mobile and chemically reactive fraction of sediment organic matter, representing the portion that can readily interact with dissolved constituents in the sediment–water interface. In small freshwater systems—including intermittent streams, drying ditches, and natural ponds—aqueous extractions of sediment organic matter have most often been applied to characterize DOC dynamics and microbial responses to hydrological variability. However, comparatively little attention has been paid to WEOC as an operationally defined, geochemically active carbon pool in sediments, particularly in relation to trace-metal associations under dynamic hydrological conditions [37,38]. Although these environments undergo strong redox fluctuations that can enhance the release of dissolved organic matter, few studies have examined how sediment-derived WEOC is associated with total Cd concentrations in sediments. This is despite evidence from eutrophic lake systems indicating that Cd distribution in pore waters is strongly influenced by complexation with dissolved organic matter under reducing conditions [39]. As a result, the role of sediment WEOC as an operationally defined carbon pool linked to Cd accumulation patterns in small, hydrologically dynamic freshwater systems remains insufficiently explored.

1.7. Contemporary Trends and Remaining Uncertainties

Despite rapid methodological and conceptual progress in understanding aquatic carbon cycling, several key uncertainties persist. First, inter-annual variability in sedimentary carbon storage under changing climatic drivers remains poorly quantified in small- and medium-sized systems [2,6].

Second, the combined effects of heavy-metal contamination on the long-term stability of sedimentary OC remain largely unexplored, and the dual relationship between these components is not well understood. While it is unclear how heavy metals influence the dynamics and preservation of OC, rapid environmental changes—particularly climate-driven alterations—can modify organic matter composition. These changes, in turn, are likely to influence the forms and association patterns of heavy metals in sediments, especially within redox-sensitive organic matter pools.

Recent advances—from dynamic carbon deposition models [3] to geospatial pollution assessments [40]—provide methodological frameworks for regional analyses but require empirical, multi-year datasets.

In Lithuania and neighbouring Baltic states, systematic multi-seasonal studies of TOC/WEOC and Cd in pond and ditch sediments remain scarce.

1.8. Objectives of This Study

This study aimed to:

- (1)

- Quantify TOC, WEOC, and Cd concentrations in sediments of small freshwater ecosystems during 2022–2024;

- (2)

- Examine spatial differences in TOC, WEOC, and Cd among waterbody types (streams, natural ponds, and drying ditches) and across regions with contrasting land-use intensity;

- (3)

- Assess interannual variability in sediment OC fractions and their association with Cd;

- (4)

- Evaluate the relative roles of bulk and water-extractable OC in shaping Cd distribution patterns in freshwater sediments.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

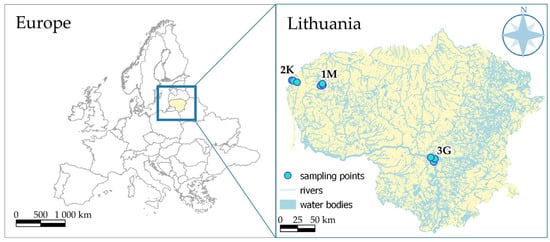

The study was conducted in three contrasting localities in Lithuania, representing a gradient of landscape structure, hydrological settings, and anthropogenic influence. Locality 1M, situated in the northern part of the country, is characterized by semi-natural forested terrain with limited human disturbance and a dense network of small streams. Locality 2K, situated near the Lithuanian–Latvian border, comprises mixed agricultural and semi-natural landscapes under moderate anthropogenic pressure and a heterogeneous hydrological network. Locality 3G, located in central Lithuania, is influenced by agricultural activity, small tributaries, and engineered drainage systems, resulting in greater spatial variation in sediment and organic matter characteristics (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Study area in Lithuania showing three wetland zones: 1M—Žemaitija NP; 2K—Kretinga District; 3G—Kauno Marios vicinity.

Across all localities, three types of waterbodies were sampled: streams, drying ditches, and natural ponds. Streams represent dynamic hydrological pathways that facilitate the mobilization and downstream transport of dissolved and particulate organic matter. Drying ditches, common in agricultural regions, exhibit episodic flow conditions and high sedimentation rates and act as temporal sinks for organic matter and fine sediments. Natural ponds, by contrast, reflect low-energy hydrological systems that promote the accumulation of fine-grained material and DOC. These three waterbody types collectively capture a representative range of hydrological and geomorphological conditions that influence carbon and metal dynamics in lake-associated sedimentary environments.

No additional subdivision of sampling sites (e.g., at the microsite level or relative to beaver dams) was retained in the final analysis, as preliminary testing indicated that these factors did not significantly affect the measured variables and were therefore excluded from the study design and subsequent statistical evaluation.

2.2. Sampling Design

Sediment sampling was performed during the summer seasons of 2022–2024 under stable hydrological conditions to avoid seasonal variability. In each of the three zones, three waterbody types were selected: stream, natural pond, and drying ditch.

Each waterbody contained five sampling points:

- Three littoral points (1–3 m from the shoreline),

- Two central points located within the flow or open-water zone.

This design ensured spatial representativeness and accounted for differences between nearshore and central sediment accumulation.

In total, 135 sediment samples were collected (3 zones × 3 waterbody types × 5 sampling points × 3 years).

Surface sediments (0–10 cm) were collected manually using a stainless-steel scoop or plastic corer. A composite sample was created from three subsamples taken within a 5 m radius at each point. Samples were placed in pre-washed polyethylene containers, labelled, and transported to the laboratory at +4 °C.

Prior to analysis, sediments were air-dried at 25 °C to constant weight, homogenized, and sieved through a <2 mm mesh. To prevent contamination and loss of organic material, all tools were made of inert materials, and working surfaces were cleaned between samples.

This sampling approach enabled reliable comparisons of TOC, WEOC and Cd among zones with different anthropogenic pressures and among distinct freshwater ecosystem types.

2.3. Laboratory Analyses

The following parameters were determined in the sediment samples: TOC, WEOC, Cd.

TOC was measured using the standard soil Tyurin wet-oxidation method (Nikitin modification). Samples were oxidized with potassium dichromate and concentrated sulfuric acid at 160 °C for 30 min, and the resulting Cr3+ complex was quantified spectrophotometrically at 590 nm (Cary 50, Varian, Agilent Technologies, Inc., Santa Clara, CA, USA) using glucose calibration standards [41,42,43].

WEOC was quantified using a continuous-flow ion detection system (San++; Skalar, Breda, The Netherlands). Aqueous extracts were prepared at a 1:5 sample-to-water ratio. In the automated analytical procedure, OC in the extract was oxidized by wet combustion in sulfuric acid under a nitrogen atmosphere while exposed to UV irradiation. The resulting carbon dioxide was detected by an infrared (IR) detector over the concentration range of 2–100 mg C L−1. Calibration was performed using potassium hydrogen phthalate (C8H5KO4) as the reference standard. All measurements followed the manufacturer’s (Skalar) protocol [44,45].

Cd concentrations in sediment samples were determined following wet-acid digestion with a mixture of nitric acid (HNO3) and hydrogen peroxide (H2O2). Dried, homogenized samples were digested at 120 °C until a clear solution was obtained, then diluted with deionised water and filtered if required. Cd was quantified by flame atomic absorption spectrometry (FAAS) using an AAnalyst 200 (PerkinElmer, Shelton, CT, USA) at 228.8 nm. Calibration was performed using certified Cd standards, and procedural blanks and reference materials were used to ensure analytical quality. The limit of detection (LOD) was 0.1 mg kg−1 (dry weight). The procedure follows established protocols for FAAS analysis of trace metals in sediments [46,47].

2.4. Quality Assurance and Quality Control (QA/QC)

All analyses were performed following internal quality-control procedures. Laboratory glassware and tools were pre-treated with 10% HNO3 and rinsed with deionized water.

Each analytical batch included blank samples and duplicates (10% of all samples). Certified reference materials [48] were used to verify accuracy. The analytical reproducibility did not exceed ±5% for carbon parameters and ±10% for Cd.

All measurements were conducted in triplicate, with within-sample deviations not exceeding 5%. Concentrations of all analyzed parameters were above detection limits, and no missing values occurred, allowing the use of the complete dataset in statistical analyses.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed in R (version 4.3.1). Data were tested for normality using the Shapiro–Wilk test and for homogeneity of variances using Levene’s test. As most variables did not meet normality assumptions, non-parametric methods were applied.

Differences in TOC, WEOC and Cd among zones, waterbody types, and sampling points were assessed using the Kruskal–Wallis test (H). When significant differences were detected, Dunn’s post hoc test with Bonferroni correction was applied. For pairwise comparisons, the Mann–Whitney U test was used.

Relationships among variables were examined using Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient (ρ). To explore multivariate patterns of spatial and chemical variability, Principal Component Analysis (PCA) was performed on standardized variables using the FactoMineR (version 2.9) and factoextra packages (version 4.3.1).

Data visualization, including boxplots, correlation matrices, and PCA biplots, was conducted using ggplot2 (version 4.3.1). Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Spatial Patterns of TOC, WEOC and Cd

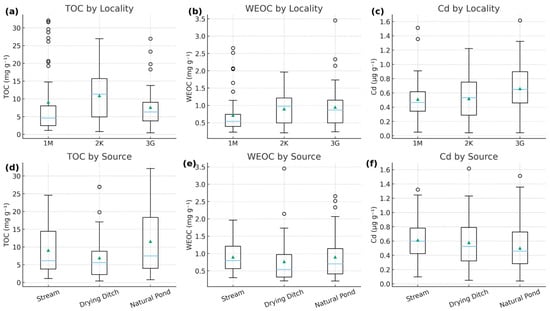

Significant spatial differences were observed in TOC, WEOC and Cd across the three localities (Figure 2). TOC showed pronounced variation among sites, with the highest values in locality 2K, intermediate levels in 3G, and the lowest concentrations in 1M. WEOC exhibited a similar spatial distribution: 1M displayed notably lower WEOC, whereas 2K and 3G showed higher and comparable values.

Figure 2.

Spatial variation in (a) TOC, (b) WEOC, and (c) Cd by locality and (d) TOC, (e) WEOC, and (f) Cd by waterbody type (streams, drying ditches, natural ponds). Boxplots show the median (horizontal line), interquartile range (boxes), and 1.5 × IQR (whiskers). Open circles represent individual observations outside the whisker range (outliers), while triangles indicate mean values.

Cd concentrations also differed significantly among localities (p = 0.0219), although the spatial gradient was less pronounced than for TOC and WEOC. Median Cd values were lowest in 1M, while 2K and 3G exhibited moderately higher and overlapping ranges, consistent with stronger associations between Cd and sediment organic matter in these zones.

Across waterbody types, streams tended to have higher TOC and WEOC than drying ditches, while natural ponds occupied an intermediate position. For Cd, source type alone did not produce statistically significant differences (p = 0.154), although streams and natural ponds generally showed slightly higher Cd variability than drying ditches.

A highly significant interaction between locality and source type (p < 0.001) indicates that the influence of waterbody type on Cd concentrations is not uniform across regions but instead depends on local geochemical and hydrological context.

Together, these spatial patterns demonstrate that landscape setting plays a primary role in shaping sedimentary organic matter characteristics and their association with trace-metal distribution in freshwater sediments.

3.2. Temporal Variation (2022–2024)

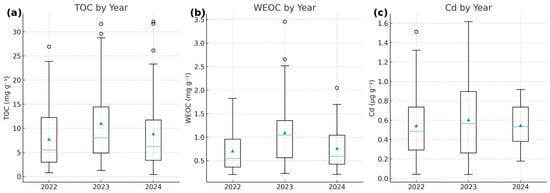

All three parameters exhibited measurable interannual variability, with a moderate elevation in 2023 relative to 2022 and 2024 (Figure 3). TOC increased from a median of 5.48 mg g−1 in 2022 to 8.03 mg g−1 in 2023, followed by a decrease to 6.19 mg g−1 in 2024. WEOC showed a similar pattern, rising from 0.55 mg g−1 in 2022 to 1.04 mg g−1 in 2023, and decreasing to 0.60 mg g−1 in 2024.

Figure 3.

Interannual variation in (a) TOC, (b) WEOC, and (c) Cd in sediments during 2022–2024. Boxplots show the median (horizontal line), interquartile range (boxes), and 1.5 × IQR (whiskers). Open circles represent individual observations outside the whisker range (outliers), while triangles indicate mean values.

Cd concentrations displayed a more subtle interannual response. Median Cd increased from 0.486 µg g−1 in 2022 to 0.564 µg g−1 in 2023 and then declined slightly to 0.532 µg g−1 in 2024, indicating only a modest year-to-year shift compared with the clearer trends observed for TOC and WEOC.

Although the magnitude of change differed across parameters, all three variables showed their highest values in 2023. This is consistent with a shared hydrological or biogeochemical influence during that year, likely affecting both organic matter mobilization and Cd dynamics.

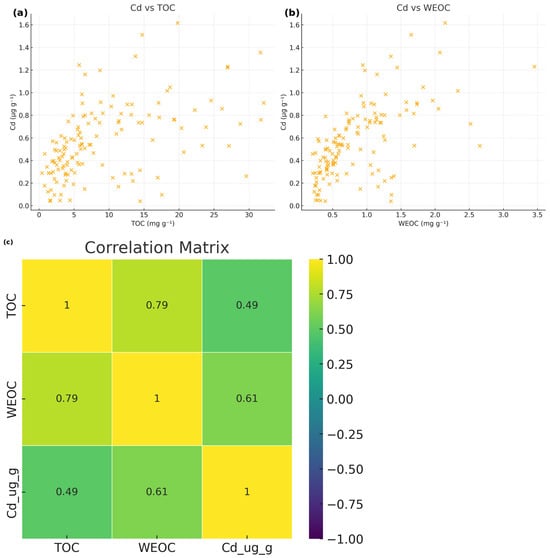

3.3. Bivariate Relationships Between Carbon Forms and Cd

The relationships among TOC, WEOC and Cd were moderate to strong but far from linear (Figure 4). Cd showed a moderate positive correlation with TOC (r = 0.49) and a stronger correlation with WEOC (r = 0.61), indicating that dissolved and water-extractable organic fractions may play a more direct role in Cd association and distribution than bulk sedimentary OC (r = 0.79) between TOC and WEOC. Scatterplots confirm substantial variability around these trends, reflecting heterogeneous sediment composition and mixed hydrological influences across the study sites.

Figure 4.

Relationships between cadmium and organic carbon pools in sediments: (a) Cd versus TOC, (b) Cd versus WEOC, and (c) Spearman correlation matrix for TOC, WEOC, and Cd.

3.4. Principal Component Analysis (PCA) and Structural Equation Model (SEM)

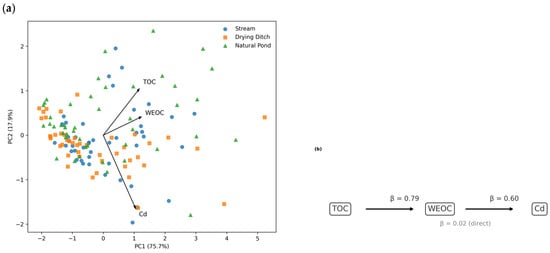

PCA revealed a dominant but not exclusive geochemical gradient underlying the joint variation in TOC, WEOC and Cd (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Multivariate relationships among organic carbon fractions and cadmium in sediments: (a) PCA biplot of TOC, WEOC, and Cd in freshwater sediments. Scores are colour-coded by waterbody type (streams, drying ditches, and natural ponds) to illustrate their distribution in multivariate space. The PCA is presented as an exploratory analysis and does not imply formal stratified statistical testing. (b) Structural equation model illustrating direct and indirect relationships among TOC, WEOC, and Cd.

In Figure 5, PCA scores are colour-coded by waterbody type to provide a descriptive comparison across streams, drying ditches, and natural ponds. Further stratification by both waterbody type and sampling year was not applied, as this would substantially reduce the number of observations within individual groups and limit interpretability.

The first principal component (PC1 = 75.7% of variance) exhibited strong positive loadings for TOC (0.586), WEOC (0.617) and Cd (0.525), indicating that all three parameters co-vary along a shared axis associated with organic matter enrichment and its influence on trace-metal behaviour.

The second component (PC2 = 17.9%) expressed a contrast between TOC (0.523) and Cd (−0.827), suggesting that part of Cd variability is not strictly aligned with the main organic matter gradient and reflects additional sedimentary or geochemical controls.

PCA structure shows that Cd is related to, but not fully aligned with WEOC, and its variability is partly independent of TOC.

This pattern implies that Cd dynamics respond to both dissolved and bulk organic matter pools, yet with different sensitivities.

SEM analysis supported a partially mediated relationship among the three variables.

TOC exerted a strong positive effect on WEOC (β = 0.79), whereas WEOC showed a moderate but significant effect on Cd (β = 0.60).

The direct pathway from TOC to Cd was minimal (β = 0.02), indicating that TOC influences Cd primarily through its control over the WEOC fraction rather than through direct mechanisms.

Together, PCA and SEM provide a coherent picture in which WEOC serves as the primary mediator linking organic matter dynamics to Cd distribution, while TOC modulates Cd concentrations mainly indirectly by shaping the pool of soluble and reactive OC.

3.5. Multiple Regression Modelling

Multiple regression analysis indicated that WEOC was the primary predictor of sediment Cd concentrations, whereas TOC did not explain additional variability once WEOC was included in the model. In the model including both predictors, WEOC showed a strong positive association with Cd (p < 0.001), while the effect of TOC was not statistically significant (p = 0.234). The resulting coefficient of determination (R2 ≈ 0.38) reflects a moderate to strong association typical of heterogeneous field datasets.

These results indicate a robust statistical association, while also suggesting that additional environmental and geochemical factors beyond OC contribute to Cd variability in sediments.

4. Discussion

4.1. Spatial Controls and Landscape Drivers

Spatial heterogeneity in TOC, WEOC and Cd across the three localities may reflects the combined influence of catchment characteristics, hydrological connectivity, and regional differences in land-use intensity. It should be noted that the present study does not include site-specific hydrological or climatic measurements, and therefore observed spatial and temporal variability is interpreted descriptively rather than attributed to specific environmental drivers.

Locality 2K consistently exhibited the highest TOC and WEOC values, whereas 1M showed the lowest concentrations, indicating a gradient in organic matter inputs and reactivity among the study regions. Cd displayed the same directional trend but with a considerably weaker contrast, suggesting that metal distribution is influenced by organic matter availability but also by additional sedimentary or geochemical factors.

This partial decoupling is consistent with findings from lake and wetland sediments where trace metals respond to both dissolved organic matter content and site-specific physicochemical conditions [5,49].

Differences among waterbody types further reinforce the role of hydrodynamics and local sediment–water interactions. Streams generally contained higher TOC and WEOC, reflecting their capacity to mobilize and redistribute both dissolved and particulate OC through continuous or seasonally sustained flow [50]. Drying ditches, in contrast, exhibited lower concentrations of reactive carbon fractions, consistent with reduced hydrological connectivity, intermittency, and enhanced carbon stabilization due to slower flow velocities. Natural ponds typically occupied an intermediate position, functioning as semi-retentive systems that integrate inflows from surrounding catchments.

Although Cd did not differ significantly across waterbody types, its variability followed the same relative ordering as TOC and WEOC, supporting the interpretation that organic matter quality and quantity exert a first-order control on Cd binding and distribution, while hydrological and geochemical context modulates this relationship [51,52].

4.2. Hydrological and Interannual Variability

Interannual variation in TOC, WEOC, and Cd demonstrates that sediment biogeochemistry responded coherently across the three study years, with a marked elevation in 2023 followed by a decline in 2024. The increase in TOC and, especially, WEOC suggests that hydrological or climatic conditions during 2023 likely enhanced the transfer of organic matter from terrestrial to aquatic environments. Such pulses of WEOC are widely associated with climatic anomalies—most notably elevated precipitation, intensified runoff, shifts in soil moisture, and temperature-driven changes in catchment organic matter processing [53,54].

Cd exhibited a similar but more moderate interannual response, with a modest increase in 2023 that paralleled the rise in WEOC. This pattern supports the interpretation that Cd dynamics are sensitive to changes in reactive organic matter pools but remain partly modulated by additional geochemical factors such as sediment redox state or mineral surface availability.

The synchronous elevation of TOC, WEOC and Cd in 2023 is consistent with global observations that dissolved and particulate carbon fractions respond rapidly to hydrological variability, particularly in small, shallow, or hydrologically dynamic systems [55,56].

These results underscore the vulnerability of lake and pond sediment processes to climatic forcing, highlighting that interannual fluctuations in hydrology can propagate directly into carbon–metal interactions and potentially amplify biogeochemical sensitivity under future increases in hydroclimatic instability in northern Europe.

4.3. Mechanistic Links Between WEOC and Cd Association

The strong positive association between WEOC and Cd observed in this study highlights the importance of sediment-derived, labile organic carbon as a key factor shaping Cd distribution patterns in freshwater sediments. Although the relationship between WEOC and Cd is not perfectly linear in the corrected dataset, it remains sufficiently strong to indicate that reactive dissolved and colloidal organic matter is closely associated with Cd accumulation in organic-rich sediment environments.

This interpretation is consistent with extensive evidence showing that low-molecular-weight and aromatic components of dissolved organic matter readily form stable complexes with divalent metals such as Cd, Zn, Cu, and Pb [57,58]. However, in the context of the present dataset, such complexation is interpreted as influencing Cd association within the sediment matrix rather than implying net mobilization or transport out of the sediment system.

Regression and SEM analyses further indicate that TOC does not exert a measurable direct effect on Cd once WEOC is included as a predictor. Instead, TOC influences Cd indirectly through its strong association with WEOC, supporting the view that bulk sedimentary organic carbon primarily represents a long-term reservoir, whereas dissolved and colloidal fractions constitute the chemically reactive pool relevant for metal association [59].

Accordingly, WEOC is interpreted here as a functionally relevant interface between sediment organic matter and Cd, reflecting conditions conducive to organo-metal co-accumulation rather than direct evidence of Cd mobilization into porewater or the overlying water column.

4.4. Multivariate Evidence and Conceptual Interpretation

The dominant gradient captured by PC1 in the PCA—characterized by strong positive loadings of TOC, WEOC and Cd—represents a broad organic–metal enrichment axis that integrates the co-variation of carbon pools and Cd across sites. This pattern is consistent with observations from boreal and temperate lake systems, where increases in organic matter inputs or hydrological connectivity tend to elevate both WEOC and associated trace metals [52].

However, the structure of PC2, which contrasts Cd against TOC, indicates that a portion of Cd variability is not strictly aligned with bulk OC and may be influenced by additional geochemical factors, such as redox conditions, mineral associations, or differences in organic ligand composition.

The SEM results complement the PCA by clarifying the mechanistic relationships among the three variables. TOC exerted a strong positive effect on WEOC, while WEOC displayed a moderate direct effect on Cd, and the direct TOC → Cd pathway was negligible. This partially mediated structure demonstrates that the influence of TOC on Cd operates predominantly through its regulation of the dissolved, reactive carbon fraction, rather than through direct mechanisms.

Together, these multivariate analyses support a conceptual model in which WEOC serves as the functional interface between sediment organic matter and Cd association, while TOC acts primarily as a reservoir shaping the size and reactivity of the dissolved carbon pool. This framework aligns with established models of organic matter–metal interactions in freshwater environments while incorporating the additional nuance revealed by the corrected dataset.

4.5. Implications for Monitoring, Management, and Environmental Policy

The updated results have potential relevance for freshwater assessment and monitoring under frameworks such as the EU Water Framework Directive (WFD) [60] and the forthcoming Nature Restoration Law [61].

Current monitoring programmes typically emphasize bulk TOC as an indicator of organic enrichment and sediment quality. However, our findings indicate that WEOC represents a more sensitive and functionally relevant indicator of trace-metal patterns, capturing the reactive fraction of OC that is closely associated with Cd distribution in sediments. This distinction is important because TOC alone did not explain Cd variability, whereas WEOC consistently predicted Cd concentrations across sites and years.

In the context of increasing climatic variability, systems characterized by elevated WEOC may be particularly sensitive to fluctuations in metal association and distribution patterns. Hydrological anomalies—such as intensified runoff or soil moisture shifts—can rapidly alter dissolved carbon pools, with immediate consequences for trace-metal interactions in sediments.

Integrating WEOC or comparable dissolved-carbon metrics into routine monitoring therefore offers a stronger early-warning signal of biogeochemical change than TOC alone. Such an approach can enhance risk assessments, guide sediment management, and support restoration planning in small lakes, streams, and wetland complexes that are sensitive to hydroclimatic regime shifts.

4.6. Methodological Considerations and Study Limitations

This study benefits from the integration of multiple analytical approaches—including nonparametric testing, correlation analysis, PCA, regression, and SEM—which together provide a coherent interpretation of carbon–metal interactions in lake-associated sediments. Nevertheless, several methodological limitations must be acknowledged.

First, sampling was restricted to the summer season, and seasonal fluctuations in WEOC, hydrology, and metal association may be substantial, particularly during spring snowmelt or autumn turnover events. Extending sampling across seasons would help clarify the temporal stability of the identified relationships.

Second, although WEOC emerged as the strongest predictor of Cd concentrations, the multivariate analyses indicate that Cd variability is not explained exclusively by dissolved organic matter but may also be influenced by additional geochemical factors captured along PC2. A more detailed characterization of organic matter—such as fluorescence spectroscopy, SUVA, FT-ICR-MS, or chromatographic separation—would help disentangle the specific WEOC fractions responsible for metal complexation.

Third, the study did not directly assess metal speciation or complexation chemistry. Incorporating models such as WHAM VII or NICA-Donnan would allow quantification of organic ligand binding and prediction of bioavailable metal fractions. Similarly, coupling hydrological measurements or catchment-scale runoff modelling would strengthen inferences regarding the climatic drivers of interannual variability.

Despite these limitations, the overall consistency of patterns across statistical approaches supports the main conclusion that WEOC plays a central—though not exclusive—role in regulating Cd dynamics in small lake and wetland sediment systems.

5. Conclusions

This study demonstrates that patterns of cadmium (Cd) distribution in freshwater sediments are more closely associated with water-extractable organic carbon (WEOC) than with bulk sedimentary organic carbon (TOC). Across localities, waterbody types, and sampling years, WEOC consistently showed the strongest statistical association with total sediment Cd, whereas TOC influenced Cd only indirectly through its relationship with WEOC.

Interannual and spatial variability in TOC and WEOC indicates that changes in organic matter inputs and reactivity are reflected in sediment Cd patterns, although these relationships are interpreted descriptively rather than attributed to specific climatic or hydrological drivers. The elevated TOC and WEOC observed in 2023, together with a more moderate increase in Cd, highlight the heterogeneous nature of interannual responses across systems.

Multivariate analyses further support this interpretation. PCA revealed a dominant organic-matter–metal association gradient shared by TOC, WEOC, and Cd, while also indicating that a portion of Cd variability is not aligned with bulk organic carbon. SEM results suggest a partially mediated structure in which TOC is related to Cd primarily through its association with WEOC, with minimal direct influence. These analyses are interpreted as exploratory, supporting observed association patterns rather than providing mechanistic proof.

From a monitoring and assessment perspective, the findings highlight the potential value of WEOC as a sensitive indicator of reactive organic conditions in sediments, complementing bulk TOC measurements. Incorporating WEOC into freshwater monitoring frameworks may improve detection of changes in sediment metal association, particularly in small and hydrologically dynamic systems. Future research should integrate seasonal sampling, detailed characterization of organic matter quality, and metal speciation or partitioning approaches to strengthen mechanistic understanding and support more robust ecological risk evaluation.

Taken together, the present dataset supports interpretation of WEOC as an indicator of sediment organic reactivity and Cd association patterns but does not allow inference on Cd partitioning, mobility, or bioavailability without additional speciation-based measurements.

6. Patents

LAMMC Programme—Productivity and Sustainability of Agrogenic and Forest Soils.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/w18030332/s1. Table S1: The contents of TOC, WEOC and Cd.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, O.B. and A.S. (Alvyra Slepetiene); methodology, K.F.; software, E.V.; validation, K.F., J.G.-I. and A.S. (Aida Skersiene); formal analysis, K.F. and A.S. (Aida Skersiene); investigation, O.B. and A.S. (Alvyra Slepetiene); resources, A.S. (Alvyra Slepetiene); data curation, B.F.; writing—original draft preparation, K.F.; writing—review and editing, J.G.-I. and A.S. (Aida Skersiene); visualization, J.G.-I.; project administration, A.S. (Alvyra Slepetiene). All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article and Supplementary Materials. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this manuscript, the authors used ChatGPT (OpenAI, GPT-5) exclusively for language editing and improvement of the academic English style, including grammar, clarity, and readability of the text. The tool was not used for study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, or generation of scientific results. All scientific content, data analysis, interpretation, and conclusions were developed solely by the authors. The authors have carefully reviewed and edited the AI-assisted text and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Mendonça, R.; Müller, R.A.; Clow, D.; Verpoorter, C.; Raymond, P.; Tranvik, L.J.; Sobek, S. Organic carbon burial in global lakes and reservoirs. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 1694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dean, W.E.; Gorham, E. Magnitude and significance of carbon burial in lakes, reservoirs, and peatlands. Geology 1998, 26, 535–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Q.; Xiaohua, M.; Zhichun, L.; Shuaidong, L.; Changchun, H.; Tao, H.; Bin, X.; Hao, Y. New perspectives on organic carbon storage in lake sediments based on classified mineralization. Catena 2024, 237, 107811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gudasz, C.; Bastviken, D.; Steger, K.; Premke, K.; Sobek, S.; Tranvik, L.J. Temperature-controlled organic carbon mineralization in lake sediments. Nature 2010, 466, 478–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sobek, S.; Anderson, N.J.; Bernasconi, S.M.; Del Sontro, T. Low organic carbon burial efficiency in Arctic lake sediments. J. Geophys. Res. Biogeosci. 2014, 119, 1231–1243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.; Long, H.; Chen, W.; Qiu, C.; Zhang, C.; Xing, H.; Zhang, J.; Cheng, L.; Zhao, C.; Cheng, J.; et al. Temperature seasonality regulates organic carbon burial in lakes. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kritzberg, E.S.; Maher Hasselquist, E.; Škerlep, M.; Löfgren, S.; Olsson, O.; Stadmark, J.; Valinia, S.; Hansson, L.-A.; Laudon, H. Browning of freshwaters: Consequences to ecosystem services, underlying drivers, and potential mitigation measures. Ambio 2020, 49, 375–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, N.J.; Bennion, H.; Lotter, A.F. Lake eutrophication and its implications for organic carbon sequestration in Europe. Glob. Change Biol. 2014, 20, 2741–2751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piwowarska, D.; Kiedrzyńska, E.; Jaszczyszyn, K. A global perspective on the nature and fate of heavy metals polluting water ecosystems, and their impact and remediation. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2024, 54, 1436–1458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kot, A.; Norton, U.; Kulczycki, G.; Guðmundsson, J.; Medyńska-Juraszek, A.; Mattilio, C.M.; Waroszewski, J. Stable and Mobile (Water-Extractable) Forms of Organic Matter in High-Latitude Volcanic Soils under Various Land Use Scenarios in Southeastern Iceland. Agriculture 2025, 15, 1255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Séguin, V.; Gagnon, C.; Courchesne, F. Changes in water extractable metals, pH and organic carbon concentrations at the soil-root interface of forested soils. Plant Soil 2004, 260, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, L.; Wang, K.; Noguera, D.R.; Jiang, J.; Oyserman, B.; Zhao, N.; Zhao, Q.; Cui, F. Transformation and speciation of typical heavy metals in soil aquifer treatment system during long time recharging with secondary effluent: Depth distribution and combination. Chemosphere 2016, 165, 100–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, B.; Ljung, K.; Ning, W.; Filipsson, H.L.; Nielsen, A.B. Relationships Between Land Use and Terrestrial Organic Matter Transfer to the Baltic Sea Over the Last 500 Years. J. Geophys. Res. Biogeosci. 2024, 129, e2023JG007477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Liu, J.; Kitch, J.; Tang, F.; Xue, B.; Yang, H. Evaluating the effectiveness of sediment retention by comparing the spatiotemporal burial of sediment carbon, nitrogen and phosphorus in a plateau lake and its affiliated reservoirs. CATENA 2023, 223, 106896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ignatavičius, G.; Satkūnas, J.; Grigienė, A.; Nedveckytė, I.; Hassan, H.R.; Valskys, V. Heavy Metals in Sapropel of Lakes in Suburban Territories of Vilnius (Lithuania): Reflections of Paleoenvironmental Conditions and Anthropogenic Influence. Minerals 2022, 12, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raulinaitis, M.; Ignatavičius, G.; Sinkevičius, S.; Oškinis, V. Assessment of heavy metal contamination in surface and subsurface layers of bottom sediments—Lake Babrukas (Lithuania). Ekologija 2012, 58, 33–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senze, M.; Kowalska-Góralska, M.; Pokorny, P.; Dobicki, W.; Polechoński, R. Accumulation of Heavy Metals in Bottom Sediments of Baltic Sea Catchment Rivers Affected by Operations of Petroleum and Natural Gas Mines in Western Pomerania, Poland. Pol. J. Environ. Stud. 2015, 24, 2167–2175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Struck, U. Changes in the C, N, P burial rates in some Baltic Sea sediments over the last 150 years—Relevance to P regeneration rates and the phosphorus cycle. Mar. Geol. 2000, 167, 43–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Remeikaitė-Nikienė, N.; Garnaga-Budrė, G.; Lujanienė, G.; Jokšas, K.; Stankevičius, A.; Malejevas, V.; Barisevičiūtė, R. Distribution of metals and extent of contamination in sediments from the south-eastern Baltic Sea (Lithuanian zone). Oceanologia 2018, 60, 193–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paliulis, D. Assessment of lake bottom sediment pollution by lead and cadmium (Lithuania). Pol. J. Environ. Stud. 2014, 23, 1273–1279. [Google Scholar]

- Rzętała, M.A. Cadmium contamination of sediments in the water reservoirs in Silesian Upland (southern Poland). Soils Sediments 2016, 16, 2458–2470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fastovetska, K.; Belova, O.; Šlepetienė, A. Lead Fixation in Sediments of Protected Wetlands in Lithuania. Land 2025, 14, 737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belova, O.; Fastovetska, K.; Vigricas, E.; Urbaitis, G.; Šlepetienė, A. Beaver Wetland Buffers as Ecosystem-Based Tools for Sustainable Water Management and Lead (Pb) Risk Control. Sustainability 2025, 17, 9892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- HELCOM. Hazardous Substances in the Baltic Sea—Fact Sheets and Data on Sediment Concentrations (As, Cd, Cr, Co, Cu, Ni, Zn) 2003–2008; Baltic Sea Environment Proceedings 120B; HELCOM: Helsinki, Finland, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- State Scientific Research Institute Nature Research Centre (NRC). Lake sediment composition and human impact in small lakes of Latvia & Lithuania—Multi-proxy investigation. Baltica 2015, 28, 99–114. Available online: https://gamtostyrimai.lt/en/leidiniai/baltica-vol-28-2-2015/ (accessed on 17 December 2025).

- Zerbe, J.; Sobczyński, T.; Elbanowska, H.; Siepak, J. Speciation of Heavy Metals in Bottom Sediments of Lakes. Pol. J. Environ. Stud. 1999, 8, 331–339. [Google Scholar]

- Mao, K.; Wang, X.; Yu, K.; Li, M.; Wang, Y.; Gao, G.; Geng, S.; Song, H.; Ning, W.; An, H.; et al. Source apportionment and ecological risk assessment of heavy metals in sediments of Dongping lake based on PCA-PMF model. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 32026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuriata-Potasznik, A.; Szymczyk, S.; Skwierawski, A.; Glińska-Lewczuk, K.; Cymes, I. Heavy Metal Contamination in the Surface Layer of Bottom Sediments in a Flow-Through Lake: A Case Study of Lake Symsar in Northern Poland. Water 2016, 8, 358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzetti, S. Heavy metal pollution in the Baltic Sea, from the North European coast to the Baltic States, Finland and the Swedish coastline to Norway. Tech. Rep. 2020, 6, 9. [Google Scholar]

- Chałabis-Mazurek, A.; Rechulicz, J.; Pyz-Łukasik, R. A Food-Safety Risk Assessment of Mercury, Lead and Cadmium in Fish Recreationally Caught from Three Lakes in Poland. Animals 2021, 11, 3507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Chen, R.; Li, Z.; Wu, X.; Xiang, K.; Wang, C.; Peng, Y. Ecological Risk and Human Health Assessment of Heavy Metals in Sediments of Datong Lake. Toxics 2025, 13, 560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eklöf, K.; von Brömssen, C.; Huser, B.; Åkerblom, S.; Augustaitis, A.; Veiteberg Braaten, H.F.; de Wit, H.A.; Dirnböck, T.; Elustondo, D.; Grandin, U.; et al. Trends in mercury, lead and cadmium concentrations in 27 European streams and rivers: 2000–2020. Environ Pollut. 2024, 360, 124761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gubri, B.; Hansen, J.P.; Wikström, S.A.; Snickars, M.; Dahl, M.; Gullström, M.; Rydin, E.; Masqué, P.; Garbaras, A.; Björk, M.; et al. Shallow Coastal Bays as Sediment Carbon and Nutrient Reservoirs in the Baltic Sea. Estuaries Coasts 2025, 48, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Downing, J.A.; Cole, J.J.; Middelburg, J.J.; Striegl, R.G.; Duarte, C.M.; Kortelainen, P.; Prairie, Y.T.; Laube, K.A. Sediment organic carbon burial in agriculturally eutrophic impoundments over the last century. Global Biogeochem. Cyc. 2008, 22, GB1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Downing, J.A. Emerging global role of small lakes and ponds: Little things mean a lot. Limnetica 2010, 29, 9–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, P.J.; Taylor, S.; Cooke, D.A.; Deary, M.E.; Jeffries, M.J. Quantifying organic carbon storage in temperate pond sediments. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 280, 111698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harjung, A.; Sabater, F.; Butturini, A. Hydrological Connectivity Drives Dissolved Organic Matter Processing in an Intermittent Stream. Limnologica 2017, 68, 71–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reverey, F.; Großkopf, T.; Mohr, J.F.; Herrmann, M.; Lischeid, G.; Premke, K. Dry–Wet Cycles of Kettle Hole Sediments Leave a Microbial and Biogeochemical Legacy. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 627, 985–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Ding, S.; Li, C.; Tang, Y.; Fan, X.; Xu, H.; Tsang, D.C.W.; Zhang, C. High cadmium pollution from sediments in a eutrophic lake caused by dissolved organic matter complexation and reduction of manganese oxide. Water Res. 2021, 190, 116711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalifa, A.M.; ElBaghdady, K.Z.; Abdel-Karim, S.; El Kafrawy, S.B.; Nafea, E.M.; El-Zeiny, A.M. Geospatial assessment of heavy metal contamination and metal-resistant bacteria in Qarun Lake, Egypt. Environ. Sci. Eur. 2025, 37, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. Standard Operating Procedure for Soil Organic Carbon: Tyurin Spectrophotometric Method; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2021; Available online: http://www.wipo.int/amc/en/mediation/rules (accessed on 21 October 2025).

- Nikitin, B.A. A method for soil humus determination. Agric. Chem. 1999, 3, 156–158. [Google Scholar]

- Šlepetienė, A.; Liaudanskienė, I. Dirvožemio organinės medžiagos modernių tyrimo metodų taikymas ir vystymas šalies dirvožemių tvarumui įvertinti agrarinėje žemėnaudoje. In Mokslinės Metodikos Inovatyviems Žemės ir Miškų Mokslų Tyrimams; Lietuvos Agrarinių ir Miškų Mokslų Centras; Lututė: Kaunas, Lithuania, 2013; pp. 406–415. ISBN 978-9955-37-149-6. [Google Scholar]

- Gershey, R.M.; Mackinnon, M.D.; Williams PJle, B.; Moore, R.M. Comparison of three oxidation methods used for the analysis of the dissolved organic carbon in seawater. Mar. Chem. 1979, 7, 289–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volungevičius, J.; Amalevičiūtė, K.; Liaudanskienė, I.; Šlepetienė, A.; Šlepetys, J. Chemical properties of Pachiterric Histosol as influenced by different land use. Zemdirb. Agric. 2015, 102, 123–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 11047:1998; Soil Quality—Determination of Cadmium, Chromium, Cobalt, Copper, Lead, Manganese, Nickel and Zinc—Flame and Electrothermal Atomic Absorption Spectrometric Methods. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 1998.

- Turek, A.; Wieczorek, K.; Wolf, W.M. Digestion Procedure and Determination of Heavy Metals in Sewage Sludge—An Analytical Problem. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NIST. Standard Reference Material 2709a: San Joaquin Soil; National Institute of Standards and Technology: Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 2019. Available online: https://www.nist.gov/srm (accessed on 21 October 2025).

- Tranvik, L.J.; Downing, J.A.; Cotner, J.B.; Loiselle, S.A.; Striegl, R.G.; Ballatore, T.J.; Dillon, P.; Finlay, K.; Fortino, K.; Knoll, L.B.; et al. Lakes and reservoirs as regulators of carbon cycling and climate. Limnol. Oceanogr. 2009, 54, 2298–2314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raymond, P.A.; Saiers, J.E.; Sobczak, W.V. Hydrological and biogeochemical controls on watershed dissolved organic matter transport: Pulse–shunt concept. Ecology 2016, 97, 5–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, M.; Ke, X.; Ma, J.; Liu, L.; Qiu, Y.; Hu, Z.; Liu, F. Dissolved Organic Matter (DOM)–Driven Variations of Cadmium Association and Bioavailability in Waterlogged Paddy Soil. J. Hazard. Mater. 2025, 492, 138065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kothawala, D.N.; Stedmon, C.A.; Müller, R.A.; Weyhenmeyer, G.A.; Köhler, S.J.; Tranvik, L.J. Controls of dissolved organic matter quality: Evidence from a large-scale boreal lake survey. Glob. Change Biol. 2014, 20, 1101–1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteith, D.T.; Stoddard, J.L.; Evans, C.D.; de Wit, H.A.; Forsius, M.; Høgåsen, T.; Wilander, A.; Skjelkvåle, B.L.; Jeffries, D.S.; Vuorenmaa, J.; et al. Dissolved organic carbon trends resulting from changes in atmospheric deposition chemistry. Nature 2007, 450, 537–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prijac, A.; Gandois, L.; Taillardat, P.; Bourgault, M.-A.; Riahi, K.; Ponçot, A.; Tremblay, A.; Garneau, M. Hydrological connectivity controls dissolved organic carbon exports in a peatland-dominated boreal catchment stream. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2023, 27, 3935–3953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, C.D.; Chapman, P.J.; Clark, J.M.; Monteith, D.T.; Cresser, M.S. Alternative explanations for rising dissolved organic carbon export from organic soils. Glob. Change Biol. 2006, 12, 2044–2053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creed, I.F.; Bergström, A.-K.; Trick, C.G.; Grimm, N.B.; Hessen, D.O.; Karlsson, J.; Kidd, K.A.; Kritzberg, E.S.; Paterson, M.J.; Rusak, J.A.; et al. Global change–driven effects on dissolved organic matter composition: Implications for for food webs of northern lakes. Glob. Change Biol. 2018, 24, 3692–3713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perminova, I.V.; Frimmel, F.H.; Kudryavtsev, A.V.; Kulikova, N.A.; Abbt-Braun, G.; Hesse, S.; Petrosyant, V.S. Molecular weight characteristics of humic substances from different environments as determined by size exclusion chromatography and their statistical evaluation. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2003, 37, 2477–2485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tipping, E.; Lofts, S.; Sonke, J.E. Humic Ion-Binding Model VII: A Revised Parameterisation of Cation-Binding by Humic Substances. Environ. Chem. 2011, 8, 225–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aiken, G.R.; McKnight, D.M.; Wershaw, R.L.; MacCarthy, P. Influence of Dissolved Organic Matter on the Environmental Fate of Metals, Nanoparticles, and Colloids. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2011, 45, 3196–3201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Directive 2000/60/EC Establishing a Framework for Community Action in the Field of Water Policy. Off. J. Eur. Communities 2000, L327, 1–73. [Google Scholar]

- European Parliament and Council. Regulation (EU) 2024/1991 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 24 June 2024 on Nature Restoration and Amending Regulation (EU) 2022/869. Off. J. Eur. Union 2024, 1–55. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reg/2024/1991/oj/eng (accessed on 21 October 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.