Abstract

Microplastics are pervasive in aquatic environments; however, their impacts on aquatic organisms at environmentally relevant concentrations remain poorly understood, particularly under field conditions. To address this gap, we employed high-throughput sequencing to assess these impacts under both field and laboratory conditions using crucian carp (Carassius auratus) as a model organism. Following a 4-week exposure in situ, the abundance of intestinal microplastics slightly increased from an initial level of 55.00 ± 59.73 items/fish to 72.67 ± 27.50 items/fish (p > 0.05). Accordingly, a total of 3036 differentially expressed genes (DEGs) were identified in the hepatic transcriptome, with notable enrichment in pathways related to lipid metabolism and oxidative stress. Furthermore, a positive correlation between intestinal microplastic abundance and exposure concentration was observed in fish following a 2-week laboratory exposure to polyamide (PA), with intestinal burdens ranging from 7.50 ± 3.54 to 367.50 ± 17.68 items/fish. The number of DEGs in the hepatic transcriptome, ranging from 41 to 380 items, demonstrated a nonlinear relationship with microplastic levels. Furthermore, these DEGs were primarily enriched in pathways associated with lipid metabolism and oxidative stress, including the PPAR signaling pathway (ko03320) and fatty acid degradation (ko00071). This suggests that microplastics at environmental levels may have detrimental effects on organisms through perturbations in lipid metabolism and oxidative stress. As expected, these findings provide essential insights for evaluating the ecological risks linked to microplastic pollution at environmental levels.

1. Introduction

Microplastics are synthetic polymer particles smaller than 5 mm in diameter [1]. Due to their small size and resistance to degradation, microplastics are readily ingested by various aquatic organisms, particularly fish, through direct consumption or trophic transfer. For instance, microplastic concentrations were found to range from 0.6–1.09 particles per fish in lake ecosystems [2] to 10–119 particles per fish in riverine environments [3]. Upon ingestion, microplastics can induce inflammation and metabolic abnormalities in tissues through physical abrasion and chemical toxicity [4]. A recent study reported that microplastics suppress oxidative stress responses in hookworms while elevating tissue peroxide levels [5]. Furthermore, the entry of microplastics into the circulatory system exerts toxic effects at both cellular and molecular levels [6]. As a result, the toxicological effects and potential health risks related to microplastic pollution have raised significant global concerns.

Transcriptomics, utilizing high-throughput sequencing technology, provides a powerful approach for examining the biological and toxicological effects of contamination on aquatic organisms. This methodology not only reveals the underlying mechanisms associated with exposure to various contaminants, including microplastics, but also enhances our understanding of these interactions. Recently, a transcriptomic analysis demonstrated that the upregulation of gene expression levels, such as gfap and α1-tubulin, were observed in zebrafish (Danio rerio) exposed to polystyrene (PS) nanoplastics (50 nm), and consequently a reduction in locomotor activity and developmental delays were noted in the larvae [6]. Similarly, PS microplastics induced oxidative damage and inflammatory responses in RAW cells through the activation of the p38 MAPK signaling pathway, ultimately leading to apoptosis [7]. In addition to the microplastic polymers, the differentially expressed genes (DEGs) in transcriptomes influenced by microplastics are also associated with a variety of factors, such as exposure dose and especially particle size. For instance, larger PS microplastics (200 nm) induced a significantly higher number of DEGs in zebrafish embryos compared to smaller particles (50 nm), even when exposed to the same concentrations; that is, 734 DEGs were identified at a concentration of 100 μg/L, whereas no DEGs were found at this level for smaller particles. However, 864 DEGs were detected for larger particles, while only 2 DEGs were observed for the smaller ones at a concentration of 1000 μg/L, respectively [8]. Similarly, the number of DEGs in zebrafish gills induced by microplastics also showed a significant correlation with the particle size; that is, there were 60 DEGs identified for particles sized between 45–53 μm, 344 DEGs for those ranging from 90–106 μm, and a notable increase to 802 DEGs for particles measuring between 250–300 μm [9]. However, the exposure concentrations employed in these studies frequently exceed environmentally relevant levels by several orders of magnitude [10]. Consequently, the effects of microplastics at realistic environmental concentrations remain poorly characterized. To elucidate the toxicological effects and underlying mechanisms in organisms exposed to environmentally relevant concentrations of microplastics is essential for a comprehensive assessment of the potential ecological risks associated with microplastic pollution.

Herein, we hypothesized that microplastic exposure would perturb conserved gene expression patterns related to specific biological processes, eliciting similar detrimental effects in both field and laboratory settings. To test this hypothesis, crucian carp were subjected to exposure in an urban river, specifically the Qing river in Beijing, which is characterized by environmental concentrations of microplastics. Concurrently, the fish were also exposed to a range of microplastic concentrations reflective of environmental levels under controlled conditions. After that, the DEGs of crucian carp exposed to the two conditions were compared, in conjunction with the quantification of microplastics present in the experimental fish. As anticipated, the present study seeks to offer robust insights for the enhanced assessment of the ecological risks associated with microplastic pollution.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials and Agents

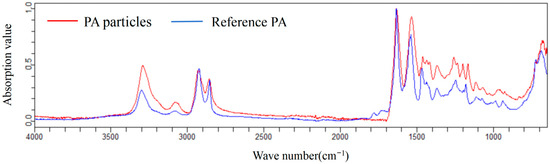

New fishing lines composed of polyamide (Mermaid Co., Ltd., Beijing, China) were melted through thermal treatment and subsequently solidified into aggregates. The aggregates were then cut into smaller fragments using scissors, followed by further pulverization into fine particles via cryogenic ball milling with liquid nitrogen (GT50R, POWTEQ Ltd., Beijing, China). PA particles ranging from 100 to 330 μm in size were obtained after sieving through a mesh, which was further characterized using a Cary 630 FTIR (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA) (Figure 1). The RNAstore™ reagent was purchased from Tiangen Biotech Co., Ltd., Beijing, China, for tissue preservation. Potassium hydroxide (KOH, purity ≥ 90%) and potassium formate (purity ≥ 96%) were obtained from Macklin Biochemical Co., Ltd., Beijing, China).

Figure 1.

Spectrum of PA particles confirmed using a Cary 630 FTIR.

2.2. Exposure in an Urban River

Crucian carp (weight: 70 ± 2.5 g; length: 17 ± 1.4 cm) were purchased from a local fishing farm and subsequently randomly divided into two groups (n = 10 per group). Fish in Group 1 were designated for baseline evaluation. That is, the entire intestine was sampled and stored at −20 °C for the detection of microplastics, while the hepatic tissues were collected and preserved in RNAstore solution at −80 °C for transcriptomic analysis. At the same time, fish in Group 2 were placed in cages constructed from stainless-steel mesh and subsequently submerged to a depth of 0.5 m below the water surface in the Qinghe River, Beijing city. These fish in the river were left to grow naturally without artificial feeding. After four weeks, fish samples were collected and quickly brought back to the laboratory for dissection. Intestinal tissues were sampled for microplastic detection, while hepatic tissues were preserved for transcriptomic analysis, respectively. The cages were cleaned daily during exposure period to remove any debris that accumulated on cage’s surface. Additionally, water quality parameters, including dissolved oxygen, temperature, pH, oxidation-reduction potential, turbidity, were also monitored weekly at the exposure site (Table 1).

Table 1.

Hydrochemical parameters of water from the experimental site in the Qing River.

2.3. Exposure in Laboratory

Crucian carp (weight: 85 ± 1.5 g; length: 18 ± 1.2 cm) were randomly divided into 12 groups (n = 10 per group) and cultured in 50-L glass tanks. Based on the microplastics abundance reported in Qing River [11], three different abundances were conducted, namely, low concentration group (environmental level, 30 PA/L), medium concentration group (10 × environmental level, 300 PA/L), and high concentration group (100 × environmental level, 3000 PA/L) by directly adding the corresponding amount of PA particles, along with control groups without PA particles. Each dosage was replicated across three tanks. The exposure conditions were rigorously maintained: the temperature was set at 23 ± 1.0 °C, with a photoperiod of 14 h light and 10 h dark. Continuous aeration was maintained to supply dissolved oxygen and ensure uniform distribution of particles throughout the water column; at the same time, approximately 50% of the water volume was changed on a daily basis, followed by the administration of commercial fish feed after the water renewal, and the corresponding doses of PA were subsequently added. After two weeks, the whole intestinal samples were collected for microplastics detection, while hepatic tissues were concurrently sampled for transcriptomic analysis.

2.4. Microplastics Analysis

In accordance with our previously established protocol [12], intestinal tissue containing contents were cut into small pieces in a beaker. Subsequently, a 10% KOH solution was added at a ratio of 1 g to 30 mL. The digestate was incubated at 50.0 ± 0.5 °C with agitation of 180 rpm to remove organic matter. Upon complete digestion (no visible tissue residues), the solution was sequentially filtered through a 500 μm and 5 μm stainless steel membrane. The beaker was rinsed three times with purified water, and the digestive solutions were subsequently filtered through the same membrane to effectively collect as many microplastics as possible. After that, the membrane (5 μm) was transferred into a 200 mL glass flask, and the fresh potassium formate solution (≈1.5 g/cm3) was added until nearly full in order to immerse the membrane completely [13]. The flask was treated with ultrasonication for 30 min in an ultrasonic reactor (KQ-500DB, Kunshan Hechuang Ultrasonic Instrument Co., Ltd., Kunshan, China), resulting in flotation of all particles on surface of solution. These particles, including microplastics, flow out from the top outlet following the addition of an excessive potassium formate solution. This operation was conducted three times to maximize the collection of microplastics. Subsequently, the overflow solution was combined and filtered using a new 5 μm stainless steel membrane. The membrane was subsequently placed into a glass concentrating tube containing 20 mL of absolute ethanol and subjected to ultrasonication for 30 min to facilitate the detachment of particles from the membrane. The ethanol solution in the concentrating tube was subsequently evaporated to near dryness under a gentle stream of nitrogen gas. The resulting residue was then transferred to a 2.0 mL glass sample vial utilizing a thin glass dropper. To ensure the collection of residual microplastics, the inner walls of the concentrating tube were rinsed with a minimal volume of absolute ethanol before being transferred into the sample vial. Finally, the volume of ethanol in vial was adjusted to 0.5 mL.

The ethanol solution containing microplastics was deposited onto glass slides and allowed to air-dry in a laminar flow hood. Subsequently, the particles less than 500 μm were analyzed qualitatively and quantitatively using an 8700 LDIR instrument (Agilent Technologies, USA). Based on the spectral features identified using reference standards, particles demonstrating a matching score exceeding 85% were classified as microplastics.

2.5. Transcriptome Analysis

Total RNA extraction, cDNA library construction, and transcriptome sequencing with three biological replicates per group were performed by Beijing Biomarker Technologies Co., Ltd. (Beijing, China). Bioinformatic analysis was also conducted on the BMKCloud platform (www.biocloud.net). Briefly, raw sequencing reads were quality-filtered, and randomness of fragmentation was assessed. De novo transcriptome assembly was conducted utilizing Trinity software (v2.15.1). The assembled sequences were functionally annotated online using multiple databases, including Gene Ontology (GO), Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG), Protein Family (Pfam), and the non-redundant (nr) protein database. Subsequently, DEGs analysis was performed using DESeq with a threshold set at Fold Change ≥ 2 and FDR < 0.01.

2.6. Quality Control

To minimize background contamination and enhance analytical quality, the entire experiment was conducted within a fume hood. Concurrently, the use of any plastic apparatus was strictly avoided to prevent potential microplastic contamination in both the experimental water and crucian carp samples. All solvents, including ultrapure water, were filtered through a 5 μm stainless steel filter prior to use. Cotton lab coats and nitrile gloves were worn throughout the experiment, and all glassware was rinsed three times with ultrapure water. Moreover, the recovery rates for extracting microplastics from the intestinal tissues of crucian carp surpassed 90%, utilizing fluorescent polystyrene microspheres (180–210 μm) as a reference.

2.7. Statistical Analysis

Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Statistical significance was evaluated using a one-way ANOVA, followed by Waller-Duncan test for multiple comparisons (IBM SPSS Statistics 20, SPSS Inc., USA). A p-value of less than 0.05 is considered to indicate statistically significant difference among the exposure groups.

3. Results

3.1. Microplastics in the Intestinal of Crucian Carp

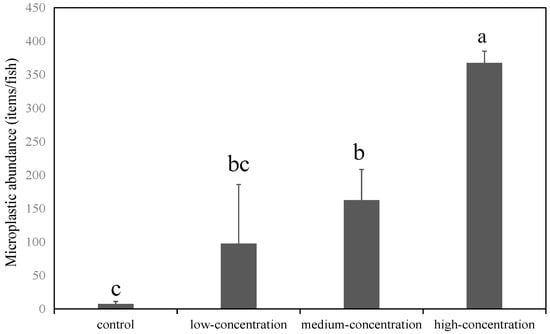

After four weeks of in situ exposure in the Qing River, intestinal microplastic abundance in crucian carp increased from 55.00 ± 59.73 to 72.67 ± 27.50 items/fish, although this increase was not statistically significant (p > 0.05). This indicates ingestion and subsequent intestinal accumulation of environmental microplastics by crucian carp. That is, approximately 97.50 ± 88.39, 162.50 ± 45.96, and 367.50 ± 17.68 items/fish were detected in fish exposed to low-, medium-, and high-abundance microplastics, respectively (Figure 2). These results demonstrate a positive correlation between intestinal microplastic burden and exposure concentration. Moreover, the control group exhibited a significantly lower microplastic abundance (7.50 ± 3.54 items/fish) compared to exposed groups (p < 0.05), confirming the ubiquitous presence of microplastics even under controlled conditions.

Figure 2.

Abundance of microplastics in the intestinal tract of crucian carp exposed in laboratory. Note: Different letters indicate significant differences (p < 0.05); the error bars represent the standard deviation.

3.2. Transcriptomic Alterations in Crucian Carp Exposure in Qing River

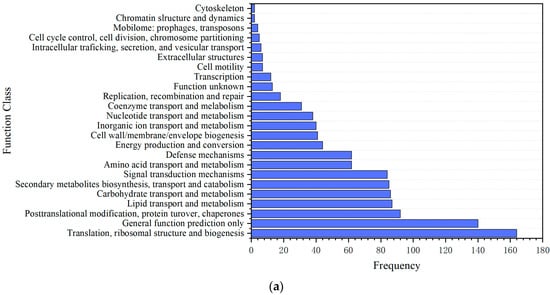

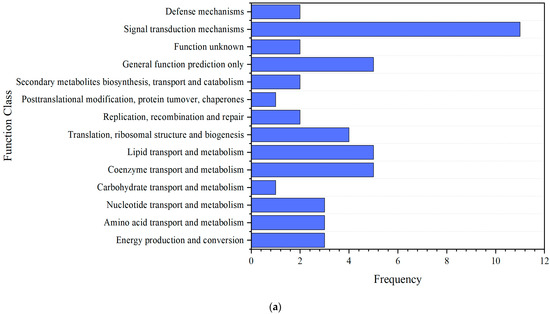

After a 4-week exposure in the Qing river, 3036 DEGs were identified in the hepatic transcriptome of crucian carp liver. Specifically, 1048 DEGs were significantly up-regulated, while 1988 DEGs were significantly down-regulated. Based on these DEGs, a GO enrichment analysis was conducted. The results indicated that a total of 10,895 DEGs were categorized into biological processes, while 3698 and 8643 DEGs were classified under cellular components and molecular functions, respectively. Additionally, among the DEGs analyzed, 1132 could be assigned to the COG classification (Figure 3a). This analysis revealed that translation, ribosomal structures and biogenesis represented the predominant category, followed by lipid transport and metabolism as well as defense mechanisms. Furthermore, a KEGG enrichment analysis mapped 3150 DEGs to 199 metabolic pathways (Figure 3b). Among these pathways, the five most significantly enriched included Peroxisome (ko04146), Ribosome (ko03010), metabolism of xenobiotics by cytochrome P450 (ko00980), fatty acid metabolism (ko01212), and drug metabolism-cytochrome P450 (ko00982).

Figure 3.

Differentially expressed genes in crucian carp exposed to microplastic pollution in the Qing river. (a) COG enrichment analysis; (b) KEGG enrichment analysis.

3.3. Transcriptomic Response of Crucian Carp Exposure to Microplastics Under Lab Conditions

Compared to the control group, only 41 DEGs, comprising 2 up-regulated genes and 39 down-regulated genes, were observed in fish exposed to the low abundance (environmental level, 30 PA/L). However, a significant higher number of DEGs were identified in fish exposed to the medium and high abundance, corresponding to 380 DEGs (117 up/263 down) and 210 DEGs (95 up/115 down), respectively. Moreover, the number of DEGs identified from the transcriptome of crucian carp did not consistently increase with increasing microplastic abundance. This indicates that DEGs in crucian carp exposed to PA microplastics, from low (30 items/L) to high abundance (3000 items/L), were not typically dose-dependent, which differed to the accumulation of microplastics in the intestinal tract.

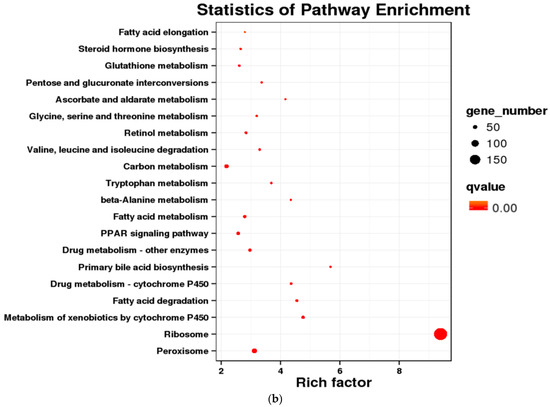

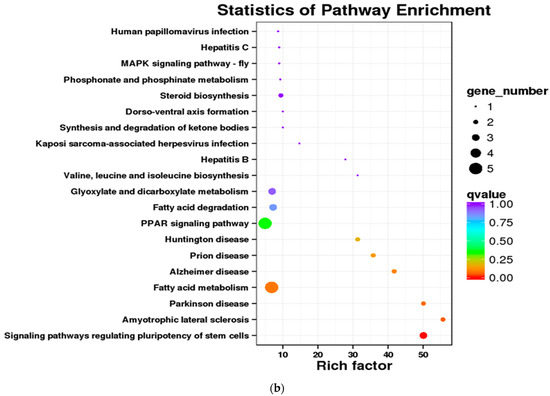

Similarly, GO enrichment analysis demonstrated consistent distribution patterns across exposure groups, with the following hierarchy: biological processes > cellular components > molecular functions. Within the category of biological processes, cellular processes were predominant, while binding emerged as the most prevalent molecular function. In terms of COG classification, alterations in nucleotide transport and metabolism were observed across all exposure groups. Additionally, posttranslational modification, protein turnover, and chaperone proteins predominantly featured in the low- and medium-concentration groups. Conversely, at medium and high concentrations, signal transduction mechanisms along with amino acid transport and metabolism; nucleotide transport and metabolism; translation; ribosomal structure; and biogenesis became more prominent. Notably, DEGs related to lipid transport/metabolism increased significantly within the high-exposure group (Figure 4a).

Figure 4.

Differentially expressed genes in crucian carp exposed to high abundance of microplastics under lab conditions. (a) COG enrichment analysis; (b) KEGG enrichment analysis.

Furthermore, KEGG enrichment analysis indicated that only 46 DEGs in the low concentration group (environmental level) were enriched across 16 KEGG pathways. In contrast, the medium concentration group (10 × environmental level) exhibited a significant increase, with 403 DEGs mapped to 116 pathways. Notable shared pathways included PPAR signaling (ko03320), mitophagy-animal (ko04137), ubiquitin-mediated proteolysis (ko04120), and hepatitis C (ko05160). The high concentration group (100 × environmental level) comprised 212 enriched DEGs associated with 100 pathways, demonstrating significant enrichment in signaling pathways that regulate pluripotency of stem cells (ko04550) and fatty acid metabolism (ko01212) (Figure 4b).

4. Discussion

4.1. Intestinal Microplastics in Crucian Carp

Microplastics can be easily ingested by aquatic organisms due to their small size, ranging from 1 μm to 5 mm. Notably, microplastics can be transferred to higher trophic levels via the food chain [14], posing ecological risks and potential threats to human health [15,16]. The present study also found that after a four-week exposure in the Qing river, the microplastics abundance in the intestinal tract of crucian carp (72.67 ± 27.50 items/fish) was slightly higher than the initial value (55.00 ± 59.73 items/fish) (p > 0.05), suggesting that the accumulation of microplastics in fish was not significant. This may be due to the relatively short exposure duration (4 weeks) and the low environmental abundance of microplastics in Qing River. Nevertheless, the detection of microplastics in fish could serve as an effective indicator for monitoring microplastic contamination in the environment, as evidenced by the document of microplastics found at Yangfang Sluice in the Qing River (37.22 ± 17.69 items/L) [11]. Laboratory experiments have further demonstrated that higher exposure concentrations increase the intestinal microplastic burden from 7.50 ± 3.54 items/fish to 367.50 ± 17.68 items/fish, corresponding to environmental levels and 100 times those levels. This concentration-response relationship has been similarly documented in other species, such as the pearl gentian grouper (Epinephelus lanceolatus) exposed to polystyrene [17]. All these findings highlight the widespread presence of microplastics ingestion and subsequent bioaccumulation in aquatic organisms. Consequently, further research is needed to elucidate the impacts of microplastics on aquatic organisms, particularly their mechanisms of action at the molecular level.

4.2. Transcriptomic Alterations in Crucian Carp Following Microplastic Exposure in Qing River

Qing river exposure revealed DEGs primarily enriched in lipid metabolism, oxidative stress response, xenobiotic metabolism and protein synthesis/transport. Moreover, KEGG pathway enrichment analysis indicated that peroxisomes play a central role in redox signaling and lipid homeostasis by mediating fatty acid β-oxidation, reactive oxygen species (ROS) metabolism, and lipid biosynthesis. Therefore, microplastic exposure may induce oxidative stress in aquatic organisms, triggering ROS accumulation which could potentially disrupt peroxisomal function. This finding is consistent with previous studies, which reported that PS microplastic exposure significantly suppressed the activities of catalase (CAT) and superoxide dismutase (SOD) in so-iuy mullet (Liza haematocheila) liver, suggesting compromised peroxisomal antioxidant capacity [18]. Concurrently, cytochrome P450 (CYP) pathway alterations were observed. As membrane-bound hemoproteins, CYP enzymes metabolize xenobiotics through oxidation, thereby exerting detoxification functions [19]. Consistent with this, polyethylene terephthalate (PET) and polypropylene (PP) microplastics elevated CYP450 isoenzyme activity in freshwater crustaceans during acute, high-concentration exposure, which was accompanied by increased antioxidant enzyme activity [20]. Similarly, the CYP450 enzyme in Daphnia magna exposed to environmentally relevant concentrations of PS microplastics (5 μg/L) was involved in the metabolism of microplastics to a certain extent [21], collectively indicating microplastics may provoke oxidative stress through xenobiotic-metabolizing pathway activation.

The number of DEGs in the liver transcriptome of crucian carp under field exposure conditions was as high as 3036, indicating a more substantial transcriptomic perturbation than that induced under controlled laboratory conditions. However, there are other pollutants in the Qing river (such as As, Cd, Cr, Cu, Pb, Zn, [22] and organophosphate esters [23], which might adsorb on microplastics or coexist in the environment), making it difficult to identify whether the observed transcriptome responses are caused by microplastics or other factors. Therefore, we conducted controlled laboratory exposures using a single microplastic polymer to isolate and clarify its specific impact on the crucian carp transcriptome.

4.3. The Influence of Microplastic Exposure on the Transcriptome of Crucian Carp

Among microplastics detected in Qing river, PA was the most abundance (25.14%), followed by polyurethane (PU, 24.32%), and PP (19.73%) [11]. Due to its highest abundance, PA was selected in this study at environmentally relevant abundance. The number of DEGs was highest in the medium-concentration group (10 × environmental level), followed by the high-concentration group (100×), and lowest in the low-concentration group (1×), and a clear dose-dependent relationship was not observed. The same trend was also observed in the transcriptome response of zebrafish (Danio rerio) embryos to bisphenol A [24]. This result suggests a biological threshold effect of microplastic exposure. Specifically, a 10 × environmental concentration activated gene defense systems, whereas a 100 × concentration exceeded response thresholds, potentially inducing compensatory suppression [25].

Environmental microplastics constitute a highly heterogeneous mixture, encompassing diverse polymers, sizes (nanoscale to microscale), shapes (e.g., fragments, fibers), and states of degradation. Thus, a single polymer type might not capture potential interactions in fish and other organisms, therefore failing to predict transcriptomic responses under realistic, mixed-exposure scenarios [26]. For instance, non-spherical microplastics, particularly fibrous ones, have been shown to compromise the intestinal stress response. Specifically, fibrous microplastics induce the down-regulation of DEGs associated with intestinal stress responses, such as il13 [27]. Meanwhile, due to the different migration and transport times of microplastics of various shapes in the intestinal tract of organisms, the resulting biological effects are diverse. For example, fibrous microplastics remain in goldfish (Carassius auratus) for a significantly longer time, compared with film and irregular fragments, which may lead to more obvious acute toxic effects [28]. Liang et al. [29] revealed synergistic interactions between different-sized plastics, where co-exposure to 50nm and 500nm polystyrene caused more severe intestinal barrier dysfunction in mice than either size alone. Moreover, a high detection rate of a certain polymer in the environment does not necessarily mean that its intrinsic toxicity (such as leaching toxicity or physical damage effects) is necessarily stronger than that of low-abundance polymers. Under uniform experimental conditions, the toxicity differences in polyvinyl chloride (PVC) and polymethyl methacrylate (PMMA) microplastics with similar sizes on renal cells of young hamsters were compared. The results showed that PVC could induce higher reactive oxygen species but lower ATP concentrations, indicating that some microplastics, such as PVC, may have lower environmental abundance than polyethylene or polypropylene. However, the toxic effects it induces are even stronger [30]. Consequently, risk assessments based solely on the most abundant polymers may overlook less prevalent but highly toxic ones, leading to underestimation of overall hazard.

4.4. The Effects of Microplastic Exposure in the Field and Laboratory on Crucian Carp

In the present study, no significant alterations were observed in the overall physiological condition of the fish following exposure under both laboratory and field conditions. This highlights the distinct advantages of transcriptomics as a highly sensitive signal for detecting early biological responses in fish exposed to microplastics [6]. Specifically, both field and laboratory microplastic exposures induced oxidative stress responses in crucian carp, supporting the role of oxidative damage as a primary mechanism of microplastic-induced cytotoxicity [31]. Notably, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (PPARs) regulate lipid/lipoprotein metabolism and glucose homeostasis, influencing cellular proliferation, differentiation, and apoptosis [32], These nuclear receptors also exhibit anti-carcinogenic properties in various human tumors [33]. Similarly, a 28-day exposure to 0.05–1% polystyrene nanoplastics (PS-NPs) significantly upregulates PPAR signaling components (including ACOX1 and CPT1A) in Monopterus albus [34]. The consistent activation of the PPAR pathway observed across various aquatic species indicates that microplastics commonly disrupt energy metabolism via this mechanism. Furthermore, as lipid sensors and metabolic regulators [35], PPARs account for the consistent lipid metabolic alterations in both our field and laboratory exposed fish. As a crucial process for maintaining energy homeostasis and metabolic balance, lipid metabolism can be perturbed by exposure to PS microplastics, which alters the expression of fatty acid metabolism-related genes in zebrafish [36]. Concurrently, a recent study demonstrated that exposure to both PE and PS microplastics significantly upregulates immune system gene expression in mature zebrafish, while downregulating genes associated with epithelial integrity and lipid metabolism [37]. These findings demonstrate that microplastics elicit complex biological effects, necessitating further investigation into their precise modes of action and long-term ecological consequences.

By employing environmentally prevalent microplastic types for controlled laboratory exposure, this study ensures ecological relevance and extrapolation potential of experimental findings. The application of single-polymer microplastics can eliminate the interference of other types of microplastics (such as different polymers, shapes, sizes, and additives) as well as complex coexisting pollutants in the wild environment (heavy metals, organic pollutants, pathogens). Therefore, the presented results indicate that microplastic exposure triggers host defense mechanisms, leading to oxidative stress, perturbed lipid metabolism, and activation of the PPAR signaling and fatty acid degradation pathways.

5. Conclusions

A combination of field and laboratory experiments demonstrated significant positive correlations between environmental microplastic abundance and intestinal accumulation in crucian carp. Importantly, environmentally relevant abundance of microplastics consistently induced metabolic dysregulation, characterized by disrupted lipid metabolism, oxidative stress, and inflammatory activation. Furthermore, significantly high abundances of microplastics may induce biological inhibitory effects. These findings provide novel mechanistic insights into the toxicity pathways associated with microplastics and offer direct evidence of their biological impacts at the molecular level. This is particularly evident through the modulation of PPAR signaling and alterations in fatty acid metabolism.

Author Contributions

Data curation, Writing—original draft: Y.W.; Data curation: Z.S.; Conceptualization, Supervision, Writing—review & editing: Y.L.; Data curation: X.W.; Conceptualization: L.A.; Conceptualization, Supervision, Writing—review & editing: H.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was financially supported by the 2024 Hebei Province Yanzhao Golden Platform Talent Gathering Program Key Talent Project (Overseas Returnee Platform) (C2024026), Hebei Provincial Natural Science Foundation Project (C2025201026), Project of College Students’ Innovation and Entrepreneurship Training Program in Hebei University (2023167; DC2025346) and National Scholarship Foundation of China (CSC 201808130270).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance, and the protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of Chinese Research Academy of Environmental Sciences (CRAES IRB 2025YS) on 15 March 2024.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Yuguang Lu was employed by the company Beijing Qinghe Management Department. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Zuri, G.; Karanasiou, A.; Lacorte, S. Microplastics: Human exposure assessment through air, water, and food. Environ. Int. 2023, 179, 108150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conowall, P.; Schreiner, K.M.; Marchand, J.; Minor, E.C.; Schoenebeck, C.W.; Maurer-Jones, M.A.; Hrabik, T.R. Variability in the drivers of microplastic consumption by fish across four lake ecosystems. Front. Earth Sci. 2024, 12, 1339822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalu, T.; Themba, N.N.; Dondofema, F.; Cuthbert, R.N. Nowhere to go! Microplastic abundances in freshwater fishes living near wastewater plants. Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2023, 101, 104210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banaei, M.; Forouzanfar, M.; Jafarinia, M. Toxic effects of polyethylene microplastics on transcriptional changes, biochemical response, and oxidative stress in common carp (Cyprinus carpio). Comp. Biochem. Physiol. C Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2022, 261, 109423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Browne, M.A.; Dissanayake, A.; Galloway, T.S.; Lowe, D.M.; Thompson, R.C. Ingested microscopic plastic translocates to the circulatory system of the mussel, Mytilus edulis (L.). Environ. Sci. Techno. 2008, 42, 5026–5031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Gundlach, M.; Yang, S.; Jiang, J.; Velki, M.; Yin, D.; Hollert, H. Quantitative investigation of the mechanisms of microplastics and nanoplastics toward zebrafish larvae locomotor activity. Sci. Total Environ. 2017, 584, 1022–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Q.; Wang, H.; He, C.; Jin, Y.; Fu, Z. Polystyrene nanoparticles trigger the activation of p38 MAPK and apoptosis via inducing oxidative stress in zebrafish and macrophage cells. Environ. Pollut. 2021, 269, 116075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedersen, A.F.; Meyer, D.N.; Petriv, A.-M.V.; Soto, A.L.; Shields, J.N.; Akemann, C.; Baker, B.B.; Tsou, W.-L.; Zhang, Y.; Baker, T.R. Nanoplastics impact the zebrafish (Danio rerio) transcriptome: Associated developmental and neurobehavioral consequences. Environ. Pollut. 2020, 266, 115090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, Y.H.; Jia, T.; Yang, N.; Sun, Z.X.; Xu, Z.Y.; Wen, X.L.; Feng, L.S. Transcriptome alterations in zebrafish gill after exposure to different sizes of microplastics. J. Environ. Sci. Health A Tox. Hazard. Subst. Environ. Eng. 2022, 57, 347–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, J.C.; Segner, H.E. Hazards of current concentration-setting practices in environmental toxicology studies. Crit. Rev. Toxicol. 2023, 53, 297–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, L.; Cui, T.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, H. A case study on small-size microplastics in water and snails in an urban river. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 847, 157461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.F.; Wu, H.W.; Wu, W.N.; Wang, L.; Liu, J.L.; An, L.H.; Xu, Q.J. Microplastic characteristics in organisms of different trophic levels from Liaohe Estuary, China. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 789, 148027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Q.; Gao, Y.; Xu, L.; Shi, W.; Wang, F.; LeBlanc, G.A.; Cui, S.; An, L.; Lei, K. Investigation of the microplastics profile in sludge from China’s largest Water reclamation plant using a feasible isolation device. J. Hazard. Mater. 2020, 388, 122067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, F.; Zeng, J.; Xu, X.; Wang, Y.; Liu, Q.; Xu, X.; Huang, W. Status of marine microplastic pollution and its ecotoxicological effects on marine fish. Haiyang Xuebao 2019, 41, 85–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadique, S.A.; Konarova, M.; Niu, X.F.; Szilagyi, I.; Nirmal, N.; Li, L. Impact of microplastics and nanoplastics on human Health: Emerging evidence and future directions. Emerg. Contam. 2025, 11, 100545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamoree, M.H.; van Boxel, J.; Nardella, F.; Houthuijs, K.J.; Brandsma, S.H.; Béen, F.; van Duursen, M.B.M. Health impacts of microplastic and nanoplastic exposure. Nat. Med. 2025, 31, 2873–2887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, B.C.; Pillai, D.; Kumar, V.J.R. Sub-chronic nanoplastic toxicity in Etroplus suratensis (Pisces, Cichilidae): Insights into tissue accumulation, stress and metabolic disruption. Aquat. Toxicol. 2025, 285, 107418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, S.; Sun, K.; Zhang, Q.; Wangkahart, E.; Wang, Z.; Sui, Y.; Qi, Z. Effects of Microplastics on the Activity of Digestive-, Antioxidative- and Immune-related Enzymes in Soiny Mullet (Liza haematocheila Temminck & Schlegel, 1845) Larvae. Turk. J. Fish Aquat. Sci. 2024, 24, TRJFAS24718. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H.; Cui, T.; Zang, M.; Sun, X.; Fang, N. Progress in research on the mechanism of norfloxacin on cytochrome P450 in aquatic organisms. J. Hebei Univ. Nat. Sci. Ed. 2020, 40, 631–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniel, D.; Vieira, M.; da Costa, J.P.; Girao, A.V.; Nunes, B. Effects of microplastics on key reproductive and biochemical endpoints of the freshwater microcrustacean Daphnia magna. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. C Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2024, 281, 109917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, M.; Li, M.; Xu, W.; Li, X.; Liu, J.; Stoks, R.; Zhang, C. Microplastics increases the heat tolerance of Daphnia magna under global warming via hormetic effects. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2023, 249, 114416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Zhang, L.; Qin, Y.; Ma, Y.; Liu, Z.; Wang, H. Assessment of Heavy Metals in Sediments of Qinghe River Based on Triangular Fuzzy Numbers. Res. Environ. Sci. 2015, 28, 1538–1544. [Google Scholar]

- Lei, Q.; Shi, Y.; Tang, Z.; Niu, L.; Zhao, X. Pollution Characteristics and Ecological Risk Assessment of Organophosphate Esters in Qinghe River, Beijing. Res. Environ. Sci. 2023, 36, 836–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez, R.; Esteve-Codina, A.; Herrero-Nogareda, L.; Ortiz-Villanueva, E.; Barata, C.; Tauler, R.; Raldua, D.; Pina, B.; Navarro-Martin, L. Dose-dependent transcriptomic responses of zebrafish eleutheroembryos to Bisphenol A. Environ. Pollut. 2018, 243, 988–997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCaw, B.A.; Leonard, A.M.; Lancaster, L.T. Nonlinear transcriptomic responses to compounded environmental changes across temperature and resources in a pest beetle, Callosobruchus maculatus (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae). J. Insect Sci. 2024, 24, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zang, C.; Liu, Y.; Bai, X.; XI, Z.; JIN, F. Research progress on toxic effects of microplastics on typical model organisms. J. Anhui Univ. Nat. Sci. Ed. 2025, 49, 98–108. [Google Scholar]

- Qiao, R.X. Toxicity of Different Shapes of Microplastics on Zebrafish Gut. Nanjing University, 2019. Available online: https://d.wanfangdata.com.cn/thesis/ChhUaGVzaXNOZXdTMjAyNDA5MjAxNTE3MjUSCFkzODk3NzAyGghrZXFwNXU4Yw== (accessed on 6 September 2025).

- Tu, Y.N. Study on the Process and Effect of Microplastics Feed by Freshwater Zooplankton and Goldfish. University of Chinese Academy of Sciences. 2018. Available online: https://www.las.ac.cn/front/book/detail?id=e55bd653b28e3961d2c66fa2c2aa606b (accessed on 6 September 2025).

- Liang, B.; Zhong, Y.; Huang, Y.; Lin, X.; Liu, J.; Lin, L.; Hu, M.; Jiang, J.; Dai, M.; Wang, B.; et al. Underestimated health risks: Polystyrene micro- and nanoplastics jointly induce intestinal barrier dysfunction by ROS-mediated epithelial cell apoptosis. Part Fibre Toxicol. 2021, 18, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahadevan, G.; Valiyaveettil, S. Understanding the interactions of poly(methyl methacrylate) and poly(vinyl chloride) nanoparticles with BHK-21 cell line. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 2089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, C.B.; Kang, H.M.; Lee, M.C.; Kim, D.H.; Han, J.; Hwang, D.S.; Souissi, S.; Lee, S.J.; Shin, K.H.; Park, H.G.; et al. Adverse effects of microplastics and oxidative stress-induced MAPK/Nrf2 pathway-mediated defense mechanisms in the marine copepod Paracyclopina nana. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 41323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montaigne, D.; Butruille, L.; Staels, B. PPAR control of metabolism and cardiovascular functions. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2021, 18, 809–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyagi, S.; Gupta, P.; Saini, A.S.; Kaushal, C.; Sharma, S. The peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor: A family of nuclear receptors role in various diseases. J. Adv. Pharm. Technol. Res. 2011, 2, 236–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, C.; Zhou, W.; Han, M.; Yang, Y.; Li, Y.; Jiang, Q.; Lv, W. Dietary polystyrene nanoplastics exposure alters hepatic glycolipid metabolism, triggering inflammatory responses and apoptosis in Monopterus albus. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 891, 164460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, J.; Moller, D.E. The mechanisms of action of PPARs. Annu. Rev. Med. 2002, 53, 409–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Bao, Z.; Wan, Z.; Fu, Z.; Jin, Y. Polystyrene microplastic exposure disturbs hepatic glycolipid metabolism at the physiological, biochemical, and transcriptomic levels in adult zebrafish. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 710, 136279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Limonta, G.; Mancia, A.; Benkhalqui, A.; Bertolucci, C.; Abelli, L.; Fossi, M.C.; Panti, C. Microplastics induce transcriptional changes, immune response and behavioral alterations in adult zebrafish. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 15775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.