Abstract

To address the challenge of low nitrogen removal efficiency, particularly the difficulty in meeting total nitrogen (TN) discharge standards during low-temperature seasons and intermittent emission modes in conventional aquaculture wastewater treatment, this study proposed the novel application of bioretention systems. Biochar and sponge iron were used as fillers to construct three bioretention systems: biochar-based (B-BS), sponge iron-based (SI-BS), and a composite system (SIB-BS), for evaluating their nitrogen removal performance for aquaculture wastewater treatment. Experimental results demonstrated that under intermittent flooding conditions at 8.0–13.0 °C and increasing TN loading (9.48 mg/L–31.13 mg/L), SIB-BS maintained stable TN removal (79.7–86.7%), outperforming B-BS and SI-BS (p < 0.05). Under continuous inflow (influent TN = 8.4 ± 0.5 mg/L) at 8.0–13.0 °C, SIB-BS achieved significantly lower effluent TN (2.57 ± 1.5 mg/L) than B-BS (5.6 ± 1.6 mg/L) and SI-BS (5.0 ± 1.5 mg/L) (p < 0.05). Meanwhile, when the temperature ranged from 8.0 to 26.3 °C, SIB-BS exhibited a more stable and efficient denitrification ability. Mechanistic investigations revealed that coupling biochar with sponge iron promoted denitrifying microbial activity and enhanced the functional potential for nitrogen transformation (p < 0.05). Specifically, biochar provided porous attachment sites and improved mass transfer, while sponge iron supplied readily available Fe2+ as an electron donor; their combination buffered iron oxidation and facilitated Fe2+-mediated electron transfer. At low temperature, SIB-BS further stimulated extracellular polymeric substances (EPS) secretion, strengthened biofilm stability without causing blockage, and improved the protective interactions between fillers, thereby increasing metabolic efficiency and sustaining TN removal under variable loading. This study provided a technical reference for the efficient denitrification of aquaculture wastewater.

1. Introduction

Global demand for aquatic products continues to rise, driving rapid growth of aquaculture [1]; this expansion has increased wastewater discharge and the associated risks to aquatic ecosystems [2]. Aquaculture wastewater typically features low pollutant concentrations, large discharge volumes, and irregular release patterns, making treatment challenging [1]. The challenge is exacerbated under low-temperature conditions, where treatment performance faces even greater constraints [3].

Under low temperatures, microbial activity in the water declines; in particular, nitrification and denitrification in the nitrogen transformation pathway are suppressed, leading to a marked decrease in nitrogen removal efficiency [4]. Consequently, conventional physicochemical methods (e.g., sedimentation and adsorption) have limited efficacy for dissolved nitrogen species, while biological methods (e.g., activated sludge and biofilters) are efficient at ambient temperatures but perform poorly at low temperatures [5,6,7]. According to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), the monthly average total nitrogen (TN) requirement is ≤ 5 mg L−1 for warm-water fish and ≤ 3 mg L−1 for salmonids (cold water) [8]. Under these limits, winter effluent readily exceeds the thresholds [9]. In addition, periodic pond cleaning produces intermittent discharge of aquaculture wastewater, which constrains traditional biofilters [10]. Biofilters depend on biofilms on the packing media; after intermittent shutdown, microbial activity can decline rapidly, and restart may require days to weeks to reestablish effective biofilms, during which treatment efficiency is low [11,12]. Thus, new treatment technologies are urgently needed.

Bioretention systems (BS) have been widely used for urban stormwater treatment [13,14]. In recent years, BS have been considered highly promising for treating aquaculture wastewater, especially for reducing nitrogen pollution. Centered on soil, the system uses its strong water-holding capacity to store water during short shutdowns and supplies microorganisms with nutrients such as ammonium through adsorption [15]. Exudates from plant roots help stabilize the microbial environment, thereby maintaining biological activity [16,17]. When wastewater supply resumes, microbial function recovers rapidly, making BS better suited to the practical operating conditions of aquaculture.

Nevertheless, conventional BS often exhibit insufficient nitrogen removal during cold seasons, when both nitrification and denitrification are constrained by low temperature and limited electron availability [18]. Media amendments have therefore been introduced to strengthen adsorption, mass transfer, and redox regulation, among which carbonaceous materials and iron-based media are most commonly adopted [19,20]. Previous studies generally indicate that such modifications can improve nitrogen removal, but performance remains variable, and their stability under low-temperature and intermittent discharge modes is still not well clarified [21,22,23].

Biochar can enhance denitrification in BS by providing porous attachment sites, improving substrate–biofilm contact, creating localized low-oxygen niches, and promoting biofilm stability (e.g., EPS formation) [24,25,26]. Sponge iron can serve as an electron donor and modulate redox conditions, thereby supporting iron-related autotrophic denitrification and shaping microbial communities [27,28]. In Feammox, the combination of biochar and sponge iron increased the abundance of anaerobic myxobacteria and iron bacteria [25]. Although these studies show that both materials can markedly improve nitrogen removal in BS, their cooperative effects under the specific water quality of aquaculture effluent require further investigation.

In this study, three types of BS were constructed: a biochar system (B-BS), a sponge iron system (SI-BS), and a composite biochar–sponge iron system (SIB-BS). With aquaculture wastewater as the influent, the nitrogen removal efficacy and operational stability of the three systems were evaluated through 6-month operation monitoring. Unlike previous modified bioretention or iron–carbon systems that mainly evaluated single amendments or were tested under relatively stable operating conditions, this work explicitly targets the combined challenges typical of aquaculture wastewater—intermittent discharge and low-temperature seasons—and assesses whether a composite amendment can provide more reliable TN compliance. Specifically, this study aimed to (1) compare the nitrogen removal efficiency of each system, particularly under low-temperature conditions; (2) evaluate the impact of biochar and sponge iron on microbial community structure; (3) elucidate the mechanisms underlying the synergistic nitrogen removal facilitated by biochar-iron interactions at low temperatures. The findings of this research provide a technical reference for efficient nitrogen removal from aquaculture wastewater.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental System Construction

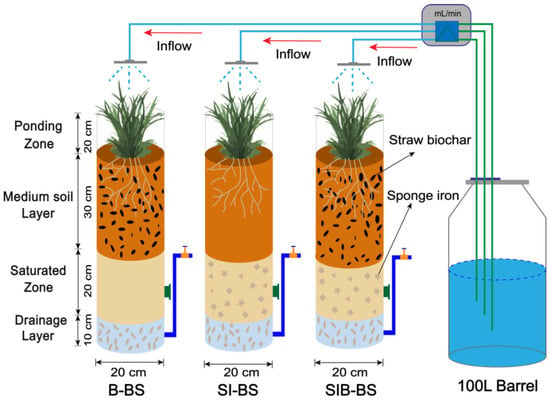

Commercially available biochar is produced through pyrolysis of corn straw at 500 °C in an anaerobic environment, sourced from Henan Lize Environmental Protection Technology Co., Ltd. (Zhengzhou, China) Sponge iron was obtained from Zhengjie Environmental Protection Materials Co., Ltd. (Wuxi, China) The gravel and river sand fillers are procured from a local building materials company, with particle sizes ranging from 8.0–23.0 mm and 0.2–4.0 mm, respectively. The soil used in this study was collected from the soil planted at Southwest University (Chongqing, China). After drying, gravel and sand were removed. For detailed physical and chemical properties, please refer to Table S1. The BRS was constructed using a circular Plexiglas column of 1 m in height with an inner diameter of 0.2 m, and three sets of parallel BRS were established, comprising a 10 cm gravel drainage layer, a 20 cm river sand saturated zone, a 30 cm soil-sand media soil layer (with a volumetric ratio of 7:3), and a 20 cm ponding zone, arranged from the bottom upwards. Each system was equipped with perforated tubes having an internal diameter of 20 mm at the base, facilitating the creation of a saturated zone that enhances denitrification by elevating the drainage outlet 30 cm above the bottom drainage layer.

In our previous research, we conducted operational experiments on traditional BRS (without any modified materials) and on the impact of biochar addition amount on the system [8]. To further explore the potential for enhancing nitrogen removal through the combined application of biochar and sponge iron, this study establishes control systems with either biochar alone or sponge iron alone, and an experimental system incorporating both. To better utilize the adsorption capacity of biochar and prevent excessive oxidation of sponge iron, biochar was added to the media soil layer, and sponge iron was added to the submerged area [21]. Notably, the composite system (SIB-BS) was designed as a double-layer configuration rather than directly mixing biochar and sponge iron within the same layer, such that the biochar functions primarily in the media soil layer while the sponge iron functions in the saturated zone. Then, 20% biochar (B-BS) was added to the media soil layer, 10% sponge iron (SI-BS) was added to the saturated zone, and a bioretention system (SIB-BS) that added 20% biochar and 10% sponge iron double-layer filler to the media soil layer and saturated zone (Figure 1), respectively. All amendment dosages (20% biochar and 10% sponge iron) were determined on a volumetric basis relative to the packing media of the corresponding layer. For B-BS, biochar was homogeneously blended with the soil–sand media (soil/sand = 7:3, v/v) prior to column packing to obtain 20% (v/v) biochar in the 30-cm media soil layer. For SI-BS, sponge iron was evenly distributed within the river-sand matrix in the 20-cm saturated zone, reaching 10% (v/v) before packing. For SIB-BS, the same dosages were applied in their respective layers (20% biochar in the media soil layer and 10% sponge iron in the saturated zone) to form the composite system while maintaining layer separation. For detailed system parameters, please refer to Table S2. The test plants for each system were selected from Iris pseudacorus, which showed a strong predominance of root length and root density, and were weighed continuously on an electronic scale to ensure that the biomass error between systems did not exceed 1.0 g [29].

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of three bioretention system devices. B-BS, SI-BS, and SIB-BS represent bioretention systems amended with biochar, sponge iron, and a biochar–sponge iron composite, respectively. The composition of the filter media is detailed in Table S2, and the characteristics of the influent wastewater are presented in Table S3.

2.2. Formulation of Aquaculture Wastewaters

To closely replicate the water-quality characteristics of aquaculture wastewater, this experiment used fish feces and chemical reagents to simulate it. Specifically, fish waste collected from a local recirculating aquaculture facility (Chongqing, China) was dried, ground, and passed through a 100-mesh sieve to produce fish waste powder. Drawing on previous visits to local pond farming in Chongqing and the research findings [30,31,32], the load concentration gradients of three pollutants were simulated. Inlet water was used to represent the wastewater from both pond culture and circulating culture (Table S3) while concurrently assessing the impact-resistance performance of the bioretention system under varying pollutant loads. Notably, additional substances, such as KNO3, NaNO2, (NH4)2SO4 (Tianjin Zhonglian Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd., Tianjin, China), and glucose (Xilong Scientific Co., Ltd., Shantou, China), were required to configure NO3−-N, NO2−-N, COD, and TP concentrations.

2.3. Operation of the System

The system was initially constructed and irrigated with pond aquaculture wastewater for two months. Upon completion of the cultivation phase, experiments were conducted across different seasons to obtain varying experimental temperatures, ensuring the experiments aligned as closely as possible with actual conditions. The experimental phase commenced in December 2022 and concluded in June 2023, totaling 6 months. To address the periodic intermittent discharges during production and continuous discharges during pond cleaning post-production in actual aquaculture, the experiments were divided into two modes: intermittent and continuous flow.

Intermittent operation mode refers to injecting water at the start of each experiment, with no water injection the following day, after which the injection is repeated (i.e., a 1-d dosing interval). A total of 19 experiments were conducted, with three inlet concentration gradients established: 10 low-TN (influent) runs (water temperature 8.0–12.8 °C), 6 medium-TN runs (water temperature 17.0–21.0 °C), and 3 high-TN runs (water temperature 8.0–12.8 °C) (corresponding to influent TN of 9.5 ± 0.3 mg/L, 20.3 ± 0.9 mg/L, and 31.1 ± 0.4 mg/L, respectively; detailed influent characteristics are provided in Table S3). Here, low/medium/high refers to influent TN loading (concentration), whereas the temperature ranges reflect seasonal operation. Each experiment utilized a sprinkler irrigation method for inflow, with a total inflow volume of 5 L, allowing for natural infiltration, and all outflow was collected for water quality analysis (Table S4).

Continuous flow operation mode refers to uninterrupted and continuous water inflow. From December 2022 to January 2023, March to April 2023, and from May to June 2023, continuous inflow operation experiments were conducted, with corresponding water temperatures of 8.0–12.8 °C, 16.5–17.3 °C, and 24.5–26.3 °C, respectively, representing winter, spring, and summer conditions. The experiments utilized low-TN influent (influent TN = 8.4 ± 0.5 mg/L; Table S3), with each experimental run lasting 72 h. Influent and effluent samples were collected at 1, 2, 4, 7, 12, 24, 36, 48, and 72 h for analysis, and all measurements were performed in triplicate.

2.4. Water Quality Measurement

The inflow and outflow water of the bioretention system were collected in polyethylene bottles, kept in the dark at 4 °C during transport, and the water quality was analyzed as soon as possible after sampling. Prior to analysis, samples were gently mixed. For dissolved (soluble) nitrogen indices, water samples were filtered through a 0.45 μm cellulose acetate membrane; unfiltered samples were used for total indices unless otherwise specified [8].

Total nitrogen (TN) was quantified using alkaline potassium persulfate digestion followed by UV-Vis spectrophotometry. Briefly, samples were digested with alkaline potassium persulfate (K2S2O8) at 121 °C (0.1 MPa) and then analyzed by UV-Vis spectrophotometry. Nitrate nitrogen (NO3−-N) was determined using UV spectrophotometry, ammonium nitrogen (NH4+-N) was measured using the Nessler’s reagent method, and nitrite nitrogen (NO2−-N) was assessed by spectrophotometry [8].

For all colorimetric/UV methods, calibration curves were prepared using external standards covering the concentration range of the samples, and method blanks were analyzed in parallel. Each sample was measured at least in duplicate (or triplicate), and the average value was reported [8].

2.5. Characterization and Determination of Physicochemical Properties

X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) and scanning electron microscopy (SEM) were applied to characterize the surface oxidation status and morphology of sponge iron before and after operation. Excitation–emission matrix (EEM) fluorescence spectroscopy was used to compare the dissolved organic matter (DOM) characteristics of EPS extracts after filtration through a 0.45 μm membrane (Ex/Em = 200–550 nm, step = 5 nm, scan speed = 12,000 nm/min). For EPS extraction, equal volumes of media samples collected at 15 cm and 45 cm depths were homogenized and extracted using a cation exchange resin procedure: samples were mixed with 0.01 M CaCl2 solution (pH 7) and shaken at 4 °C for 30 min, centrifuged (3200× g) to remove soluble organics, then resuspended in a cold extraction buffer (2 mM Na3PO4·12H2O, 4 mM NaH2PO4·H2O, 9 mM NaCl, and 1 mM KCl) with cation exchange resin and shaken at 4 °C for 2 h; the supernatant obtained after centrifugation (4000× g) was used for EPS analyses. Polysaccharides (PS) were determined by the phenol–sulfuric acid method, and proteins (PN) were quantified using a BCA kit (562 nm). ETSA was determined based on the reduction of INT to formazan: 10 g of sample was washed twice with phosphate buffer (PBS, 100 mM, pH 7.4), resuspended in PBS, and incubated with NADH (1 mg) and INT (1 mL) in the dark at 30 °C for 30 min; the reaction was terminated with formaldehyde, formazan was extracted with methanol, and absorbance was measured at 490 nm. These EPS/ETSA procedures were consistent with our previous work [8].

2.6. Metagenomic Analysis

Equal volumes of soil samples were collected from depths of 15 cm and 45 cm within bioretention systems. These samples were thoroughly mixed and stored in an ultra-low-temperature refrigerator at −80 °C. Upon completion of each sampling stage, the samples were sent to Shanghai Meiji Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China) for DNA extraction. Following genomic DNA extraction, 1% agarose gel electrophoresis was performed to assess the quality of the extracted DNA. The isolated DNA was subsequently fragmented to approximately 400 bp using an automatic focus acoustic genome shearer (M220 Focused-ultrasonicator, Covaris, Woburn, MA, USA). After fragmentation, primers were introduced for amplification, and high-throughput sequencing was conducted utilizing Illumina NovaSeq Reagent Kits (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA).

Utilize Prodigal v2.6.3 (https://github.com/hyattpd/Prodigal (accessed on 21 November 2023)) to perform ORF prediction on the contigs derived from the splicing results. Select genes with a 100 bp or greater nucleic acid length and translate them into amino acid sequences. The predicted gene sequences from all samples were clustered using CD-HIT, with the longest gene in each cluster designated as the representative sequence to construct a non-redundant gene set. Employ SOAPaligner (SOAP2, version 2.21) to align the high-quality reads of each sample against the non-redundant gene sets and subsequently quantify the abundance of genes in the respective samples.

2.7. Data Analysis

IBM SPSS Statistics 24 was employed for statistical analysis, while Origin 2018 and Excel 2016 were utilized for data processing. Graphics production was conducted using Adobe Illustrator 2020. All samples were analyzed in triplicate, and the data are presented as mean ± standard deviation.

For the assessment of pollutant treatment performance (e.g., nitrogen removal efficiency, effluent nutrient concentrations) across the three bioretention systems (B-BS, SI-BS, SIB-BS) or under different experimental conditions (e.g., varying temperatures, influent concentrations), one-way analysis of variance (One-way ANOVA) was performed, followed by Tukey’s honestly significant difference (HSD) post hoc test for pairwise comparisons when overall differences were significant. For comparisons between two groups (e.g., EPS content of a single system under low vs. high temperature), an independent samples t-test was used. A p-value of less than 0.05 was deemed statistically significant. Pearson correlation analysis was also applied to evaluate the linear correlation between variables.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Nitrogen Removal Efficacy of Bioretention Systems Operated Intermittently at Different Influent Concentrations

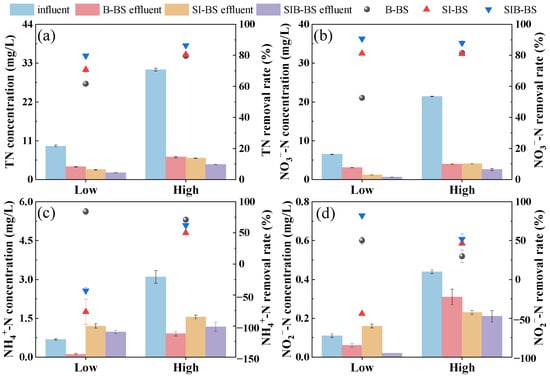

The experimental results demonstrated (Figure 2) that three bioretention systems exhibited effective nitrogen removal under varying influent concentration conditions. Under low-temperature conditions (8.0–12.8 °C), SIB-BS displayed excellent adaptability, achieving TN removal rates of 79.7 ± 1.1% and 86.4 ± 0.5% for low and high wastewater concentrations, which were significantly higher than those of B-BS and SI-BS (p < 0.05). In terms of effluent compliance, SIB-BS consistently met the stringent TN limits across the tested loadings: at low loading (influent TN = 9.5 ± 0.3 mg/L), its effluent TN was 1.9 ± 0.1 mg/L (≤3.0 mg/L), whereas B-BS exceeded the limit (3.6 ± 0.04 mg/L); at high loading (influent TN = 31.1 ± 0.4 mg/L), SIB-BS still achieved an effluent TN of 4.2 ± 0.1 mg/L (≤5.0 mg/L), while both B-BS and SI-BS failed to comply. Meanwhile, although B-BS showed comparatively better NH4+-N removal, SIB-BS maintained lower NO3−-N and NO2−-N levels and achieved the most stable overall TN control under low temperature.

Figure 2.

Nitrogen removal efficiency of B-BS, SI-BS, and SIB-BS under intermittent operation mode: (a) TN, (b) NO3−-N, (c) NH4+-N, (d) NO2−-N. Batch experiments with “low” and “high” influent concentrations were conducted at a temperature of 8.0–12.8 °C. The influent pollutant concentrations and experimental replicates were statistically detailed in Tables S3 and S4.

When the temperature ranged from 17.0–21.0 °C, the nitrogen removal efficiency of all systems increased, with SIB-BS maintaining the highest removal rate of 86.7%. This underscores its stability and high efficiency under varying environmental conditions (Figure S1). At an influent TN concentration of 20.3 ± 0.9 mg/L, the TN concentration in the effluent from SIB-BS was 2.7 ± 0.1 mg/L, which complies with the standard of ≤3.0 mg/L. In contrast, the TN concentrations in the effluents from SI-BS and B-BS were 4.5 ± 0.2 mg/L and 5.0 ± 0.1 mg/L, respectively. SI-BS met the standard of ≤5.0 mg/L, while B-BS failed to meet the discharge standard. Regarding NO3−-N removal, when the influent concentration was 12.8 ± 0.5 mg/L, the removal rates for B-BS, SI-BS, and SIB-BS were 70.4 ± 1.5%, 78.8 ± 1.7%, and 87.4 ± 0.9%, respectively. For NO2−-N removal, SIB-BS also showed an advantage, indicating that SIB-BS has a relatively high denitrification rate. At an influent NH4+-N concentration of 2.7 ± 0.1 mg/L, the NH4+-N removal rates for B-BS, SI-BS, and SIB-BS were 70.0 ± 1.6%, 54.1 ± 3.7%, and 68.8 ± 1.6%, respectively, indicating biochar addition improved NH4+-N removal.

The synergistic use of biochar and iron has been further confirmed to enhance nitrogen removal efficiency in other studies. For instance, the pyrite-woodchip-biochar mixed system maintained a total dissolved nitrogen (TDN) removal rate between 64% and 86% across various dry-wet cycles and pollutant load conditions, significantly outperforming single filler improvement systems [13,21]. However, monitoring the removal of NH4+-N revealed that the performance of the B-BS with only biochar was the best. The reason for this may be that biochar facilitates the enrichment of ammonia-oxidizing bacteria (AOB, predominantly Nitrosomonas spp.), thus promoting the conversion of NH4+-N to NH2OH [33]. The dual-layer filler SIB-BS demonstrated markedly stronger resistance to NO2−-N shock compared to B-BS and SI-BS, attributable to the biochar–sponge iron synergy. The Fe-C composite system can generate electrons in situ, which denitrifying bacteria utilize to reduce NO3−-N to NO2−-N and further reduce it to N2 [34].

3.2. Nitrogen Removal Efficacy of Bioretention Systems Operating Continuously at Different Influent Temperatures

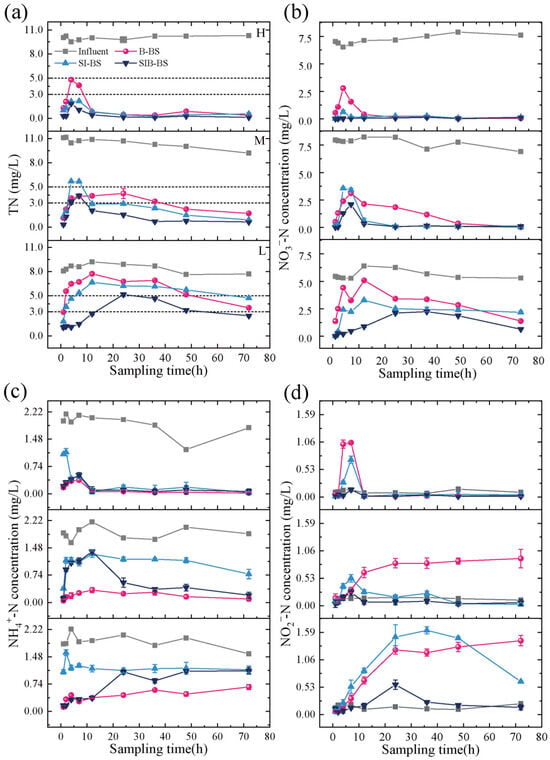

SIB-BS demonstrated superior treatment efficacy to B-BS and SI-BS for TN, NO3−-N, and NO2−-N (Figure 3). Overall, with increasing operation time, effluent TN, NO3−-N, and NO2−-N generally showed an initial rise followed by a decline and eventual stabilization, except that NO2−-N in B-BS under low and moderate temperatures continued to increase. Compared with B-BS and SI-BS, SIB-BS exhibited more stable performance under continuous feed. Under low-temperature conditions (8.0–12.8 °C), the average concentrations of TN, NO3−-N, NH4+-N, and NO2−-N in the effluent from SIB-BS were 2.6 ± 1.5 mg/L, 1.0 ± 0.8 mg/L, 0.6 ± 0.4 mg/L, and 0.2 ± 0.2 mg/L, which were 45%, 31%, 147%, and 26% of those from B-BS, and 52%, 48%, 50%, and 24% of those from SI-BS, respectively.

Figure 3.

Nitrogen removal performance of B-BS, SI-BS, and SIB-BS under continuous inflow and varying temperature conditions: (a) TN, (b) NO3−-N, (c) NH4+-N, and (d) NO2−-N. All figures present nitrogen concentrations (influent vs. effluent) in sequential order from top to bottom: H means high temperature (24.5–26.3 °C), M means medium temperature (16.5–17.3 °C), and L means low temperature (8.0–12.8 °C), within each panel, data are arranged from top to bottom as H, M, and L.

For TN removal (Figure 3a), under high-temperature conditions (24.5–26.3 °C), the peak concentrations of effluent from the three systems occurred between 4 and 7 h, measuring 4.5 ± 0.4 mg/L, 2.1 ± 0.1 mg/L, and 1.5 ± 0.4 mg/L, respectively. All effluents from B-BS met the standard of ≤5.0 mg/L, while all effluents from SIB-BS and SI-BS met the standard of ≤3.0 mg/L. As the temperature decreases, the peak concentrations of the effluents from the three systems show an increasing trend. When the temperature dropped to low levels (8.0–12.8 °C), the peak concentrations of the effluents from the B-BS, SI-BS, and SIB-BS systems were 7.71 mg/L, 6.65 mg/L, and 5.15 mg/L. The proportion of SIB-BS effluent samples that met the standard of ≤5.0 mg/L was 89%, whereas only 33% and 44% of the effluent samples from B-BS and SI-BS met this standard. Similar studies have shown that iron-carbon composite materials used in improved constructed wetlands can treat agricultural runoff at low temperatures (6.2–13.5 °C). By adding organic substrates and polyphosphate-denitrifying bacteria, the TN removal rate increased from 17.7% in the control group to 68.2% in the improved group [23]. In this study, without the addition of organic matter and denitrifying bacteria, the average nitrogen removal efficiency of the SIB-BS system at low temperature (8.0–12.8 °C) still reached 68.7%.

NO3−-N was the main form of TN in the influent (Table S3). The variation in its effluent concentration was consistent with that of TN (Figure 3b), suggesting that TN reduction under continuous inflow was mainly driven by NO3−-N removal in all systems. Across the three temperature levels, SIB-BS consistently showed the lowest NO3−-N peaks and faster recovery than B-BS and SI-BS, indicating a more stable nitrate-control capacity under temperature variation.

The variation in effluent NH4+-N concentration followed a pattern similar to that of TN (Figure 3c), with the distinction that B-BS exhibited the best removal efficiency for NH4+-N. At high temperatures, all three systems demonstrated sufficient NH4+-N removal efficiency, with effluent concentrations approaching zero. However, as the environmental temperature decreased, there was a noticeable increase in effluent NH4+-N concentration, particularly when the temperature dropped to lower levels, where the effluent ammonium nitrogen concentration no longer showed a declining trend but rather a gradual increase. This indicated that ammonia oxidation was more sensitive to temperature changes. The addition of biochar can increase AOB abundance, alleviating temperature inhibition of ammonia oxidation [33]. Meanwhile, Fe(0)/Fe(II) may provide electrons for NO3−-N reduction, but elevated Fe(II) could also favor DNRA-related pathways, which may help explain why SI-BS exhibited a higher effluent NH4+-N at moderate and low temperatures.

The concentration of NO2−-N in the effluent exhibited different patterns of variation (Figure 3d). Under low and moderate-temperature conditions, the concentration of NO2−-N in the effluent from B-BS showed a gradually increasing trend. At 72 h, the concentrations of NO2−-N in the effluent from B-BS under low and moderate-temperature conditions reached 1.43 mg/L and 0.91 mg/L, respectively. The variation pattern of NO2−-N concentration in the effluent from SIB-BS was consistent with that of NO3−-N, with peak concentrations of only 0.14 mg/L and 0.05 mg/L under low and moderate-temperature conditions, respectively. This indicated that although there was an accumulation of NO2−-N in the early stages, SIB-BS consistently maintained the lowest effluent concentration. The synergistic effect of biochar and sponge iron could further promote the conversion of NO2−-N, thereby avoiding its continuous accumulation.

3.3. Interfacial Effects of Biochar–Sponge Iron Modified Media

3.3.1. Physicochemical Effects

SEM and XPS were employed to analyze the potential chemical interactions between multi-medium modifications. The SEM images of the sponge iron samples (Figure S2) revealed that the layered structure on the surface disappeared after prolonged use, replaced by a rougher surface morphology, as seen in b-1 and c-1. Comparison between c-2 and b-2 showed that c-2 exhibited a rougher texture, while b-2 remained relatively smooth. These results suggested that the biochar layer in SIB-BS protected the sponge iron [21], preventing excessive oxidation and thereby extending its service life.

Further investigation using X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) revealed differences in the oxidation states of sponge iron between SI-BS and SIB-BS. The full spectrum (Figure S3) showed that, compared to the original sponge iron samples, the Si and O1s peak intensities increased in the used samples, while the Fe2p peak intensity decreased, indicating partial oxidation of sponge iron within the system. Notably, the Fe2p peak was almost undetectable in SI-BS. These results suggested that the biochar layer alleviated the excessive oxidation of sponge iron.

The multiple-peak-fitting method was employed to analyze Fe2p spectra. The analysis showed that the iron content in the used sponge iron decreased, while Fe3+ peak proportions increased significantly. Notably, in SI-BS, Fe3+ increased from 77.32% to 96.05%, whereas Fe2+ decreased from 21.22% to 2.56%. Previous studies reported that Fe2+ ions serve as electron donors for chemical denitrification; oxidation of low-valent iron releases electrons for nitrate reduction [35]. The higher proportion of surface Fe2+ in SIB-BS compared to SI-BS suggested reduced oxidation of sponge iron in SIB-BS. These results confirmed that biochar in the upper medium layer provides protective effects, mitigating sponge iron corrosion rates.

3.3.2. Biochemical Effect

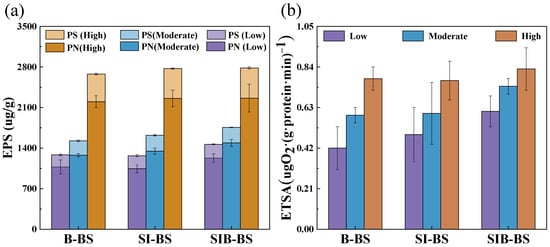

To reveal the impact of the relationship between EPS and ETSA on nitrogen removal in bioretention systems, the EPS and ETSA content in these systems were analyzed (Figure 4). As the water temperature increased, the EPS content showed an upward trend. The PN of SIB-BS at low temperature was significantly higher at 1226.95 μg/g compared to B-BS (1075.24 μg/g) and SI-BS (1045.70 μg/g) (p < 0.05). At high temperature, the PN and PS of the three bioretention systems reached their highest levels, but the differences were not significant. The non-significant change in PS for the iron-containing systems (SI-BS and SIB-BS) at high temperature may indicate that polysaccharides, as a major structural fraction of EPS, reached a relatively stable level once mature biofilms were established [36]. Moreover, the presence of Fe(II)/Fe(III) can promote EPS bridging and complexation with iron (hydr)oxides [37], which may reduce the extractable/free PS fraction and thus lead to comparable measured PS values despite enhanced overall microbial activity. The ETSA variation pattern was similar to that of EPS; with increasing water temperature, ETSA in the bioretention systems also showed an upward trend. SIB-BS consistently maintained the highest value, especially under low temperature conditions, where SIB-BS (0.6 ± 0.1 μgO2·(g·protein·min)−1) was significantly higher than B-BS (0.42 ± 0.1 μgO2·(g·protein·min)−1) and SI-BS (0.5 ± 0.1 μgO2·(g·protein·min)−1) (p < 0.05).

Figure 4.

EPS content and ETSA of media soils in B-BS, SI-BS, and SIB-BS under different temperatures: (a) EPS and (b) ETSA. “High, Moderate, and Low” mean high temperature (24.5–26.3 °C), medium temperature (16.5–17.3 °C), and low temperature (8.0–12.8 °C), respectively.

Studies have shown that EPS, primarily consisting of proteins, are microbial secretions that promote the adhesion of microbial individuals and the formation of biofilms [38,39]. Furthermore, EPS is closely related to the nitrogen removal performance of bioretention systems, as it contains redox-active substances [36]. During denitrification, electrons from electron donors are transferred through the electron transport system, which then reduces nitrate to N2 [40]. The oxidatively active substances stored in EPS, such as type C cells and humic substances, can serve as mediators for electron transfer. The increase in EPS may be a reason for the enhanced electron transfer activity [37]. When ETSA is promoted, it may enhance electron transfer during denitrification, thereby potentially improving nitrogen removal efficiency [41]. Research has shown that adding EPS can enhance electron transfer by 1.66 times, thereby improving denitrification [42]. This may explain why changes in ETSA were consistent with EPS, and why variations in ETSA potentially affected the nitrogen removal efficiency of the bioretention systems. SIB-BS had significant advantages in terms of EPS and ETSA, particularly its outstanding performance at low temperatures, which was a key factor in maintaining efficient nitrogen removal. However, high EPS may lead to medium blockage and affect effluent efficiency [37]. A comparison of infiltration rates was conducted among the three systems, and no clearly blockage was observed (Table S5).

3.4. Mechanism of Nitrogen Removal by Biochar–Sponge Iron Synergistic Enhancement of Bioretention System

3.4.1. Effect of Biochar–Sponge Iron on Microbial Composition

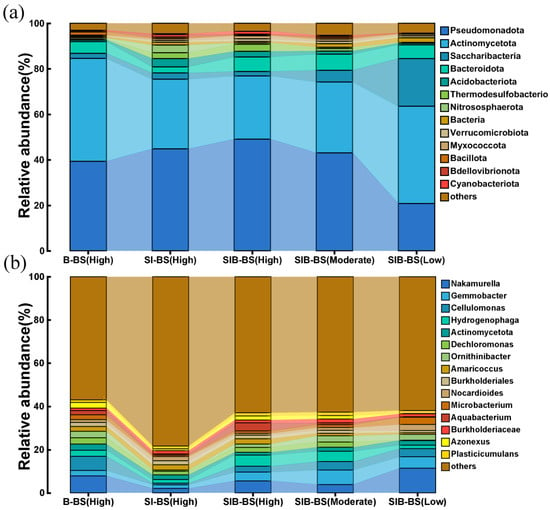

Under high load conditions in high temperature, the composition at the phylum level showed clear differentiation among the three systems: in SIB-BS(HIGH), the relative abundances of Pseudomonadota and Actinomycetota are 59.6% and 22.1%, respectively; in SI-BS(HIGH), they were 52.7% and 28.8%; and in B-BS(HIGH), they were 49.2% and 39.2% (Figure 5). The overall abundance of phyla related to nitrification is relatively low, with Nitrospirota accounting for only 1.1%/0.7%/0.4% in the three systems, and Nitrososphaerota also ≤4.1%. This indicated that the differences in the systems studied were primarily not driven by nitrification. In contrast, SIB-BS exhibited lower NO3−-N/NO2−-N ratios and higher TN removal in Section 3.1 and Section 3.2 (Figure 2 and Figure 3). Therefore, considering the characteristics of Pseudomonadota as the core phylum carrying denitrification functions (including denitrifying genera such as Hydrogenophaga and Thauera) [43], the community framework dominated by Pseudomonadota was more conducive to the progression of denitrification [44]. At the genus level, SIB-BS(HIGH) was enriched with various key groups related to denitrification: Hydrogenophaga (5.2%), Gemmobacter (4.1%), and Aquabacterium (3.7%), whereas in SI-BS(HIGH) these were 1.7%/1.7%/0.6%, and in B-BS(HIGH) they were 2.8%/2.5%/2.0%. Hydrogenophaga and Aquabacterium were often involved in hydrogen/ferrous iron donor-driven autotrophic denitrification [45,46], whereas Gemmobacter was commonly found in heterotrophic denitrification niches in biofilm/wetland systems [47]. Combining with the material characterization in Section 3.3.1, it was evident that the proportion of Fe(II) on the surface of sponge iron in SIB-BS was higher, and over-oxidation was suppressed (SEM/XPS), indicatied that Fe(III)/Fe(II) donors were more persistent and hydrogen production was more stable, which aligns with the higher proportions of the aforementioned denitrifying genera [48,49]. Additionally, the micropores and weak conductivity characteristics of biochar can reduce local DO, provide electron shuttle sites, and buffer intermediates such as NO2−, facilitating the closure of the denitrification electron chain and preventing the accumulation of intermediates [24]. Accordingly, in SIB-BS, the increases observed at both the phylum and genus levels were a higher abundance of Pseudomonadota and of H2/Fe-dependent denitrifying genera, which were consistent with its lower effluent NO3−-N and NO2−-N.

Figure 5.

Microbial community structure in bioretention systems (a) relative abundance at the phylum level (b) relative richness at the genus level. The abundance of microbial communities in three sets of bioretention systems was measured at high temperatures to compare microbial community structure between the systems. SIB-BS was measured at three temperatures to compare microbial community structure.

Across the temperature gradient (low, moderate, high), SIB-BS exhibited a continuous internal shift: Pseudomonadota increased from 35.1% to 59.6%, whereas Actinomycetota decreased from 50.6% to 22.1%. At low temperature, Nakamurella was more abundant (11.3%); with increasing temperature, Hydrogenophaga rose from 1.6% to 4.8% to 5.2%, and Aquabacterium from 0.2% to 0.8% to 3.7%. This shift was consistent with Section 3.3.2: EPS (PN/PS) and ETSA increased with temperature, and SIB-BS already exhibited higher EPS/ETSA at low temperatures (Figure 4). At low temperatures, the system relied on dense, EPS-rich biofilms to maintain the reaction interface and a micro-oxic redox layer. As the temperature increased, hydrogen generation from iron corrosion and mass transfer/extracellular electron transfer (EET) were enhanced, further amplifying the advantage of H2/Fe-dependent denitrifiers [50,51]. In line with the continuous flow results in Section 3.2, SIB-BS showed lower NO3−-N peaks at low and moderate temperatures. NO2−-N peaks were smaller with faster recovery (Figure 3b–d).

It should be noted that the typical nitrifying clades accounted for uniformly low proportions across the three systems and showed little variation (Nitrospirota 0.4–1.1%, Nitrososphaerota ≤ 4.1%), which did not support the conclusion of nitrification-driven differences among the systems. Accordingly, divergence of clades involved in denitrification is more likely to account for the differences in TN, NO3−-N, and NO2−-N performance among the three systems [52,53]. Additionally, the elevated effluent NH4+-N observed for sponge iron alone (SI-BS) in Section 3.1 and Section 3.2 may be due to promotion of dissimilatory nitrate reduction to ammonium (DNRA) by Fe(II); In SIB-BS, the adsorption and shuttling roles of biochar may suppress competition from DNRA and channel electrons to the denitrification pathway, consistent with the lack of a significant increase in NH4+-N [54,55].

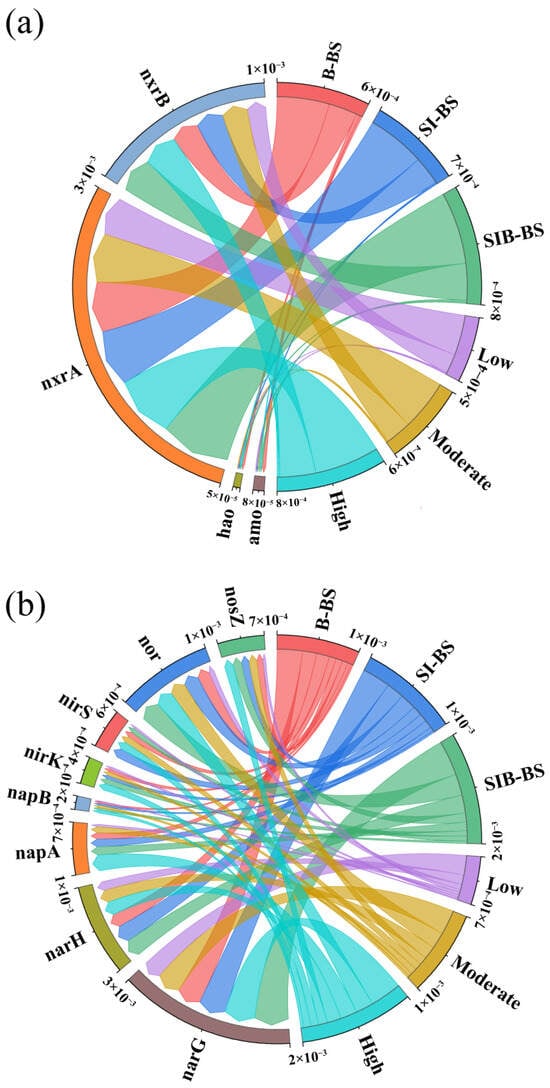

3.4.2. Effect of Biochar–Sponge Iron on Denitrification Genes

The combined use of sponge iron and biochar synergistically regulates the differential expression of nitrification and denitrification functional genes, and the coupling between the materials and the microenvironment strengthens cascade gene functions. Together, these effects enhance nitrogen removal efficiency and confer strong resistance at low temperatures (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Analysis of gene abundance of nitrogen metabolism pathway in bioretention systems: (a) Nitrification gene abundance; (b) Denitrification gene abundance.

Biochar and sponge iron regulate nitrification genes with clear selectivity; this selectivity stems from the fundamental differences between amo/hao and nxrA/B: amo/hao are core genes of ammonia-oxidizing microorganisms (AOB/AOA) that mediate the oxidation of NH4+-N to NO2−-N (the initiation step of nitrification); nxrA/B are characteristic genes of nitrite-oxidizing bacteria (NOB, e.g., Nitrospira) that catalyze the oxidation of NO2−-N to NO3−-N (the coupling step of nitrification) [56,57]. The two depend on different functional guilds and exhibit divergent responses to the materials. The abundance of amo/hao was highest in B-BS, followed by SIB-BS, and lowest in SI-BS. In B-BS, we infer that biochar, through its porous structure and surface functional groups, built a more stable niche for ammonia-oxidizing microorganisms (AOB/AOA) [58]. Its abundances of amo (0.0000273) and hao (0.0000174) were 2.05 and 2.00 times in SIB-BS, and 3.25 and 2.87 times in SI-BS, consistent with the superior NH4+-N removal of B-BS; in iron-containing systems, iron-based materials may inhibit AOB/AOA activity through chemical toxicity and passivation of the cell surface, and Fe(II) oxidation and precipitation can form an encrusting layer on the cell surface [59,60]. Among the iron systems, inhibition was strongest in SI-BS (amo and hao were only 31% and 35% of those in B-BS), whereas in SIB-BS, the inhibition was weaker because biochar adsorbed Fe(II) (abundances were 48–50% of those in B-BS). The abundance of nxrA/nxrB was highest in SIB-BS, followed by SI-BS, and lowest in B-BS. In SIB-BS, nxrA (0.000536) and nxrB (0.000275) were 1.38 and 1.29 times those in B-BS, and 1.24 and 1.30 times those in SI-BS. Compared with AOA/AOB, NOB show stronger potential for metal tolerance [61]; moreover, biochar adjusted the pH into their suitable range (7.2–7.8) and reduced Fe(OH)3 encrustation [62]. In B-BS, oxygen consumption by biochar suppressed aerobic NOB, yielding the lowest abundance, which was consistent with the observed accumulation of NO2−-N [63]. B-BS accumulated NO2−-N due to the pattern of high amo/hao and low nxrA/B; SI-BS showed inefficient nitrification due to low amo/hao and intermediate nxrA/B; whereas SIB-BS achieved efficient coupling of nitrification through moderate amo/hao and high nxrA/B, thereby providing sufficient substrate for denitrification and supporting its optimal TN removal (Section 3.1 and Section 3.2). This pattern reflects a regulatory logic of the materials: suppress taxa that are sensitive and promote taxa that are tolerant.

At the denitrification gene level, SIB-BS exhibited an advantage in aligning core gene abundance with function, attributable to synergy between sponge iron and biochar within the material–microenvironment. Upstream, the abundances of narG (membrane nitrate reductase) and napA (periplasmic nitrate reductase) were higher than in the single-material systems: narG was 1.24 times that of SI-BS (0.000536 vs. 0.000432) and 1.38 times that of B-BS (0.000536 vs. 0.000389), while napA was 1.06 times that of SI-BS and 1.27 times that of B-BS. Mechanistically, sponge iron sustained electron supply via Fe2+ and H2, and biochar, through its porosity and functional groups, enriched functional bacteria such as Hydrogenophaga, together enhancing the conversion of NO3−-N to NO2−-N [48]. Downstream, nor (nitric oxide reductase) and nosZ (nitrous oxide reductase) increased more markedly in SIB-BS (relative to SI-BS: +34% and +10%; relative to B-BS: +63% and +34%). The electron-shuttling function of biochar accelerated electron transfer and, combined with sufficient upstream NO availability, promoted the enrichment of Thauera, reduced greenhouse gas accumulation, and completed nitrogen removal [24]. Critically, SIB-BS exhibited a distinct pattern; nirK (copper nitrite reductase) was found to be 1.41 times more abundant than in SI-BS and 1.54 times more than in B-BS. In contrast, nirS (cytochrome cd1 type) was only 51% of that in SI-BS and 83% of that in B-BS. This pattern may suggest microenvironmental selection: elevated Fe2+ availability from sponge iron and the lower-oxygen conditions associated with biochar could disfavor nirS-type denitrifiers (e.g., Paracoccus), whereas nirK-type groups reported to tolerate low temperature and Fe2+ stress may be relatively favored [64,65,66]. Consistently, XPS indicated a higher fraction of Fe2+ on the sponge iron surface in SIB-BS (Section 3.3.1), SEM showed passivation and corrosion mitigation of iron by biochar, and higher EPS/ETSA under low-temperature (Section 3.3.2) lowered electron transfer resistance. These factors may jointly help explain the efficient cascade operation of denitrification genes and are consistent with the lower effluent NO3−-N/NO2−-N and the more stable TN removal observed for SIB-BS.

Variation in gene abundance along the temperature gradient further highlights resilience at low temperature: from Low to High, most genes increased; napA rose by about 6.1-fold, nor and nosZ increased by 3.4-fold and 3.3-fold, and nitrification genes also increased with temperature. Even at the low-temperature stage, SIB-BS maintained an intact narG/nap–nirK–nor–nosZ cascade at a certain abundance, with baseline expression of amo/hao; together with high abundance of Hydrogenophaga/Thauera and increases in EPS/ETSA, this supported lower effluent NO3−-N/NO2−-N and higher TN removal at 8–12.8 °C.

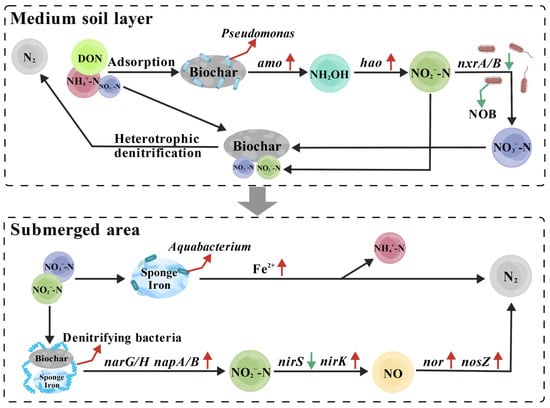

3.5. Nitrogen Removal Process by Biochar–Sponge Iron Bioretention System

The biochar–sponge iron bioretention system achieved efficient and stable nitrogen removal via a multistage “adsorption–nitrification–denitrification” coupling mechanism, jointly driven by the media layer and the saturated zone, and well matched to the water-quality characteristics of aquaculture effluent. Based on the results of the intermittent-flow tests in Section 3.1 (simulating pulsed influent during water exchange) and the continuous-flow tests in Section 3.2 (simulating routine steady discharge), and considering water quality evolution, the microbial community structure (Section 3.4.1), and the material interface properties (Section 3.3), the denitrification process of the system is resolved as follows (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Synergistic nitrogen removal process in SIB-BS amended with biochar and sponge iron.

Aquaculture effluent, driven by feed residue degradation and metabolic activity, is characterized by high NH4+-N, the presence of readily degradable organic carbon, and suspended solids (SS) composed mainly of undigested feed particles and biological debris [67]. After entering the system, the wastewater first percolates into the media soil layer that contains negatively charged clay minerals. Through electrostatic interactions, the clay minerals strongly adsorb NH4+, forming the primary nitrogen interception barrier [68]. Biochar, relying on its porous structure and surface oxygen-containing functional groups, simultaneously achieves three functions: adsorbing dissolved DON and some NH4+ from wastewater, and physically retaining SS to reduce the risk of pore blockage in the medium [69]. And it adsorbs organic carbon released from feed decomposition to store an in situ carbon source for denitrification, avoiding external reagents and matching the low-cost treatment needs of aquaculture wastewater.

Within the aerobic microenvironment of the media layer, NH4+-N is converted via a shortcut nitrification pathway. Microbial community analysis confirmed that biochar promoted the enrichment of Pseudomonas (heterotrophic nitrifiers), which, under the catalysis of amo and hao annotated in the functional gene analysis, rapidly transformed the high proportion of NH4+-N in the wastewater into NO2−-N [70]. At the same time, biochar markedly suppressed the proliferation of NOB and the expression of nxrA/B (Section 3.4.2), resulting in incomplete conversion of NO2−-N to NO3−-N [71]. This characteristic fits the high NH4+-N input condition in aquaculture effluent, reduces the formation of NO3−-N, and thereby lowers the denitrification load in the downstream saturated zone. For the NO3−-N already formed, and that present in the influent, organic carbon adsorbed in the media layer is released slowly and supplies a carbon source to heterotrophic denitrifiers for in situ nitrogen removal. In addition, the high water retention of biochar in the planting soil layer lengthens the oxygen diffusion path; together with oxygen consumption by organic carbon decomposition and by corrosion of sponge iron, it produces a synergy of two oxygen consumption processes that builds a low-oxygen microenvironment favorable for denitrification in the saturated zone [72]. A small amount of organic carbon leached into the saturated zone further replenishes the carbon source reserve.

During the dry period, NO3−-N and NO2−-N that accumulate in the media layer migrate to the saturated zone together with nitrogen introduced during the inflow period. Removal occurs mainly through the coupling of autotrophic denitrification and heterotrophic denitrification. In the saturated zone, the addition of sponge iron enriches autotrophic denitrifiers such as Aquabacterium and Hydrogenophaga. XPS confirmed that sponge iron continuously releases Fe2+, which serves as an inorganic electron donor; under the catalysis of nitrate reductases and periplasmic nitrate reductases encoded by narG/H and napA/B, NO3−-N is efficiently converted to NO2−-N (Equation (1)). At the same time, organic carbon adsorbed by biochar provides energy for dominant heterotrophic denitrifiers (e.g., Thauera). Together, these processes form an Fe2+ organic carbon electron donor synergy that sustains continuous denitrification. Subsequently, NO2−-N is reduced to nitric oxide by nirK/S, and nitric oxide is finally converted to nitrogen gas through the enzymatic actions of nor and nosZ, completing the detoxification of N2.

10Fe2+ + 2NO3− + 24H2O → 10Fe(OH)3 + N2 + 18H+

The formation of the iron-carbon microsystem in the saturated zone further enhances the synergistic effect of the filler-microorganism-gene system: biochar passivates and inhibits corrosion of the sponge iron surface through physical coverage, extending the electron donor release cycle. At the same time, the quinone functional groups on the biochar surface can serve as electron shuttles, accelerating the transfer of Fe2+ to the EET of bacteria, thereby addressing the core contradiction that the oxidation rate of Fe2+ is faster than its utilization by microorganisms [73]. This microsystem significantly increased the abundances of the key denitrifying genera reported in Section 3.4.1 (Hydrogenophaga, Thauera; one-way ANOVA, p < 0.05) and increased the relative abundances (functional potential) of the functional genes reported in Section 3.4.2, including narG/H, napA/B, nirK, norB/C, and nosZ. At low temperatures (8–12.8 °C), proliferation of Nakamurella detected in Section 3.4.1 promoted EPS secretion [74]. Section 3.3.2 showed that EPS improved electron transfer efficiency; polysaccharides and proteins in EPS complexed Fe2+ and inhibited its oxidative deactivation [75]. Together with the low-temperature adaptation of nirK noted in Section 3.4.2, these effects mitigated the decline in denitrification performance relative to the single-material systems, consistent with the more stable nitrogen removal observed in SIB-BS at low temperature in Section 3.1 and Section 3.2.

In summary, the denitrification advantage of SIB-BS arises from functional division and precise synergy between biochar and sponge iron. In the media layer, biochar emphasizes nitrogen interception and shortcut nitrification, matches the water quality of aquaculture effluent with high NH4+-N and suspended solids, and reduces the downward nitrogen load. In the saturated zone, sponge iron, together with the electron shuttling and corrosion mitigation provided by biochar, builds a two-path denitrification system that secures efficient nitrogen conversion. Together, these effects enable efficient and stable nitrogen removal from aquaculture wastewater under both intermittent flow and continuous flow conditions.

4. Conclusions

Overall, our results demonstrate that incorporating biochar and sponge iron in a dual-layer bioretention configuration can substantially improve TN stability control in aquaculture wastewater, especially under low-temperature conditions and intermittent/continuous discharge modes common in practice. This indicates that SIB-BS could serve as a promising polishing option to enhance the likelihood of meeting stringent effluent TN requirements, whereas single amendments may be less robust under challenging conditions. Nevertheless, practical applications should consider potential long-term consumption/passivation of sponge iron and associated maintenance (e.g., media replacement/regeneration), as well as possible hydraulic performance changes under real wastewater matrices. The main findings of this study are summarized as follows:

- (1)

- Three bioretention systems exhibited good nitrogen removal efficiency during intermittent inflow, and SIB-BS performed best. At 8.0–12.8 °C, at influent TN concentrations of 9.5 ± 0.3 mg/L and 31.1 ± 0.4 mg/L, respectively, SIB-BS had effluent TN concentrations of 1.9 ± 0.1 mg/L and 4.2 ± 0.1 mg/L, respectively, with TN removal rates of 79.7% and 86.4%.

- (2)

- Under continuous inflow conditions, SIB-BS had lower TN concentrations in the effluent than B-BS and SI-BS at varying temperatures (8–26.3 °C). At low temperature (8–12.8 °C), the SIB-BS’s TN concentration (2.6 ± 1.5 mg/L) was significantly lower than that of B-BS (5.6 ± 1.6 mg/L) and SI-BS (5.0 ± 1.5 mg/L). (p < 0.05).

- (3)

- The combination of biochar and sponge iron promoted the enrichment of denitrifying genera (Hydrogenophaga, Thauera, etc.), boosting denitrification genes (narG/H, napA/B, etc.) and facilitating nitrate/nitrite denitrification.

- (4)

- Biochar and sponge iron addition promoted the secretion of EPS, optimized the electron transfer pathway mediated by Fe2+, accelerated electron transfer efficiency, and enhanced the low-temperature nitrogen removal stability of bioretention systems.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/w18020270/s1, Table S1. Filler parameters. Table S2. Media composition of bioretention systems. Table S3. Simulated influent pollutant concentrations (mg/L). Table S4. Number of experimental trials. Table S5. Infiltration rate of three improved bioretention systems. Figure S1. Performance of B-BS, SI-BS, and SIB-BS in nitrogen removal under intermittent mode at 17.0–21.0 °C. Figure S2. Morphological changes in sponge iron: SEM analysis pre- and post-experiment. Figure S3. Surface chemical characterization of sponge iron via XPS pre- and post-utilization.

Author Contributions

J.W. and W.J. organized the framework of the paper. S.W. and X.Y. proposed the study idea and were responsible for revising the manuscript. C.Z. contributed to the testing and analysis of experimental data and participated in the writing of this paper. L.W., J.L. and L.J. contributed to the writing of the paper and data analysis. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was financially supported by the open fund of “China (Guangxi)-ASEAN Key Laboratory of Comprehensive Exploitation and Utilization of Aquatic Germplasm Resources, Ministry of Agriculture” (No. GXKEYLA-2023-01-3).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Materials. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Li, K.; Jiang, R.T.; Qiu, J.Q.; Liu, J.L.; Shao, L.; Zhang, J.H.; Liu, Q.G.; Jiang, Z.J.; Wang, H.; He, W.H.; et al. How to control pollution from tailwater in large scale aquaculture in China: A review. Aquaculture 2024, 590, 741085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, V.-G.; Nguyen, M.-K.; Nguyen, H.-L.; Thai, V.-A.; Le, V.-R.; Vu, Q.M.; Asaithambi, P.; Chang, S.W.; Nguyen, D.D. Ecotoxicological response of algae to contaminants in aquatic environments: A review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2024, 22, 919–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Li, X.; Xu, G.; Yu, H. Overview of strategies for enhanced treatment of municipal/domestic wastewater at low temperature. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 643, 225–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qu, J.; Zhao, R.; Chen, Y.; Li, Y.; Jin, P.; Zheng, Z. Enhanced nitrogen removal from low-temperature wastewater by an iterative screening of cold-tolerant denitrifying bacteria. Bioprocess Biosyst. Eng. 2022, 45, 381–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Liu, Y.; Li, B.; Ding, L.; Wei, X.; Wang, P.; Chen, Z.; Han, S.; Huang, T.; Wang, B.; et al. Physiological responses to heat stress in the liver of rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) revealed by UPLC-QTOF-MS metabolomics and biochemical assays. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2022, 242, 113949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bordignon, F.; Birolo, M.; Fanizza, C.; Trocino, A.; Zardinoni, G.; Stevanato, P.; Nicoletto, C.; Xiccato, G. Effects of water salinity in an aquaponic system with rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss), black bullhead catfish (Ameiurus melas), Swiss chard (Beta vulgaris), and cherry tomato (Solanum lycopersicum). Aquaculture 2024, 584, 740634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santigosa, E.; Constant, D.; Prudence, D.; Wahli, T.; Verlhac-Trichet, V. A novel marine algal oil containing both EPA and DHA is an effective source of omega-3 fatty acids for rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss). J. World Aquac. Soc. 2020, 51, 649–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, W.; Yang, X.; Zhang, C.; Qian, Q.; Liang, Z.; Liang, J.; Wen, L.; Jiang, L.; Wang, S. Enhanced Nitrogen Removal from Aquaculture Wastewater Using Biochar-Amended Bioretention Systems. Water 2025, 17, 2751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, S.; Singh, V.; Cheng, L.; Hussain, A.; Ormeci, B. Nitrogen removal from wastewater: A comprehensive review of biological nitrogen removal processes, critical operation parameters and bioreactor design. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2022, 10, 107387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Han, Y.; Liu, J.; Li, B.; Li, J.; Li, W.; Shi, P.; Pan, Y.; Li, A. Occurrence, distribution and potential environmental risks of pollutants in aquaculture ponds during pond cleaning in Taihu Lake Basin, China. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 939, 173610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cramer, M.; Traenckner, J. Development of Decay in Biofilms under Starvation Conditions-Rethinking of the Biomass Model. Water 2020, 12, 1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burut-Archanai, S.; Ubertino, D.; Chumtong, P.; Mhuantong, W.; Powtongsook, S.; Piyapattanakorn, S. Dynamics of Microbial Community During Nitrification Biofilter Acclimation with Low and High Ammonia. Mar. Biotechnol. 2021, 23, 671–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, Z.; Song, Y.Q.; Xu, M.; Yang, Y.; Wang, X.Y.; Ma, H.Y.; Zhi, Y.; Shao, Z.Y.; Chen, L.; Yuan, Y.S.; et al. Multi-media interaction improves the efficiency and stability of the bioretention system for stormwater runoff treatment. Water Res. 2024, 250, 121017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tansar, H.; Duan, H.F.; Mark, O. Unit-scale- and catchment-scale-based sensitivity analysis of bioretention cell for urban stormwater system management. J. Hydroinform. 2023, 25, 1471–1487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, T.; Sage, J.; Técher, D.; Gromaire, M.-C. Hydrological performance of bioretention in field experiments and models: A review from the perspective of design characteristics and local contexts. Sci. Total Environ. 2025, 965, 178684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.-X.; Chen, S.-J.; Hong, X.-Y.; Wang, L.-Z.; Wu, H.-M.; Tang, Y.-Y.; Gao, Y.-Y.; Hao, G.-F. Plant exudates-driven microbiome recruitment and assembly facilitates plant health management. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2025, 49, fuaf008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afridi, M.S.; Kumar, A.; Javed, M.A.; Dubey, A.; de Medeiros, F.H.V.; Santoyo, G. Harnessing root exudates for plant microbiome engineering and stress resistance in plants. Microbiol. Res. 2024, 279, 127564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Søberg, L.C.; Viklander, M.; Blecken, G.-T. Nitrogen removal in stormwater bioretention facilities: Effects of drying, temperature and a submerged zone. Ecol. Eng. 2021, 169, 106302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswal, B.K.; Vijayaraghavan, K.; Tsen-Tieng, D.L.; Balasubramanian, R. Biochar-based bioretention systems for removal of chemical and microbial pollutants from stormwater: A critical review. J. Hazard. Mater. 2022, 422, 126886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, Q.; Zhangsun, X.; Cao, J.; Zhang, F.; Huang, T. Water-lifting aerator coupled with sponge iron-enhanced biological aerobic denitrification to remove nitrogen in low C/N water source reservoirs: Effect and mechanism. Environ. Res. 2025, 277, 121557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, Z.; Song, Y.; Shao, Z.; Chai, H. Biochar-pyrite bi-layer bioretention system for dissolved nutrient treatment and by-product generation control under various stormwater conditions. Water Res. 2021, 206, 117737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.-J.; Zhao, Z.-Y.; Li, J.; Wang, J.; Qi, Y. An anaerobic two-layer permeable reactive biobarrier for the remediation of nitrate-contaminated groundwater. Water Res. 2013, 47, 5977–5985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, R.; Zhao, Y.; Jiang, M.; Cun, D.; Xiong, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Chang, J. Agricultural runoff treatment by constructed wetlands filled with iron-carbon composites in winter: Performance augmentation by organic solids and denitrifying bacteria addition. Bioresour. Technol. 2023, 387, 129692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, A.; Wang, Z.; Shi, C.; Li, N.; Bai, M.; Yao, J.; Hrynsphan, D.; Qian, H.; Hu, S.; Wei, J.; et al. Enhanced denitrification performance via biochar-mediated electron shuttling in Pseudomonas guariconensis: Mechanistic insights from enzymatic and electrochemical analyses. Environ. Pollut. 2025, 382, 126667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Xie, Y.; Sun, S.; Zhang, M.; Yan, P.; Xu, F.; Tang, L.; He, S. Efficient nitrogen removal through coupling biochar with zero-valent iron by different packing modes in bioretention system. Environ. Res. 2023, 223, 115375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sathishkumar, K.; Li, Y.; Sanganyado, E. Electrochemical behavior of biochar and its effects on microbial nitrate reduction: Role of extracellular polymeric substances in extracellular electron transfer. Chem. Eng. J. 2020, 395, 125077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Zhang, X.; Wang, Z.; Song, X.; Cheng, M.; Cheng, M.; Zhang, Y. Enhancing the pollutant removal performance and biological mechanisms by adding ferrous ions into aquaculture wastewater in constructed wetland. Bioresour. Technol. 2019, 293, 122003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Chen, B.; Zhu, L.; Xing, B. Effects and mechanisms of biochar-microbe interactions in soil improvement and pollution remediation: A review. Environ. Pollut. 2017, 227, 98–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Cao, X.; Zhao, J.; Dai, Y.; Cui, N.; Li, Z.; Cheng, S. Performance of biofilter with a saturated zone for urban stormwater runoff pollution control: Influence of vegetation type and saturation time. Ecol. Eng. 2017, 105, 355–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashem, A.H.M.; Das, P.; Hawari, A.H.; Mehariya, S.; Thaher, M.I.; Khan, S.; Abduquadir, M.; Al-Jabri, H. Aquaculture from inland fish cultivation to wastewater treatment: A review. Rev. Environ. Sci. Bio Technol. 2023, 22, 969–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Ke, H.; Xie, J.; Tan, H.; Luo, G.; Xu, B.; Abakari, G. Characterizing the water quality and microbial communities in different zones of a recirculating aquaculture system using biofloc biofilters. Aquaculture 2020, 529, 735624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Luo, G.; Tan, H.; Sun, D. Effects of sludge retention time on water quality and bioflocs yield, nutritional composition, apparent digestibility coefficients treating recirculating aquaculture system effluent in sequencing batch reactor. Aquac. Eng. 2016, 72–73, 58–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.; Wen, X.; Cao, Z.; Cheng, R.; Qian, Y.; Mi, J.; Wang, Y.; Liao, X.; Ma, B.; Zou, Y.; et al. Modified cornstalk biochar can reduce ammonia emissions from compost by increasing the number of ammonia-oxidizing bacteria and decreasing urease activity. Bioresour. Technol. 2021, 319, 124120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quan, X.; Zhang, H.; Liu, H.; Chen, L.; Li, N. Remediation of nitrogen polluted water using Fe–C microelectrolysis and biofiltration under mixotrophic conditions. Chemosphere 2020, 257, 127272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, T.; Chi, Y.; Wang, Y.; Shi, X.; Jin, X.; Jin, P. Diversified metabolism makes novel Thauera strain highly competitive in low carbon wastewater treatment. Water Res. 2021, 206, 117742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wang, H.; Xu, Y.; Tu, Q.; Chen, X. Achieving enhanced denitrification via hydrocyclone treatment on mixed liquor recirculation in the anoxic/aerobic process. Chemosphere 2017, 189, 206–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Zhang, M.; Zhou, Z.; Qu, T.; Ran, J.; Zhang, J.; Li, X.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, A. Effect of extracellular polymeric substances removal and re-addition on anaerobic digestion of waste activated sludge. J. Water Process Eng. 2024, 57, 104702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, A.; Cheng, X.; Wang, C.; Kang, L.; Chen, P.; He, Q.; Zhang, G.; Ye, J.; Zhou, S. Extracellular polymeric substances trigger an increase in redox mediators for enhanced sludge methanogenesis. Environ. Res. 2020, 191, 110197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Li, C.; Shen, Y.; Zhu, N. Anaerobic ammonium oxidation (anammox) promoted by pyrogenic biochar: Deciphering the interaction with extracellular polymeric substances (EPS). Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 802, 149884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Xu, F.; Yang, C.; Su, X.; Guo, F.; Xu, Q.; Peng, G.; He, Q.; Chen, Y. Highly efficient nitrate removal in a heterotrophic denitrification system amended with redox-active biochar: A molecular and electrochemical mechanism. Bioresour. Technol. 2019, 275, 297–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, F.; Xu, F.; Cai, R.; Li, D.; Xu, Q.; Yang, X.; Wu, Z.; Wang, Y.; He, Q.; Ao, L.; et al. Enhancement of denitrification in biofilters by immobilized biochar under low-temperature stress. Bioresour. Technol. 2022, 347, 126664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Chen, T.; Gao, C.; Xie, Y.; Zhang, A. Effect of extracellular polymeric substances removal and re-addition on the denitrification performance of activated sludge: Carbon source metabolism, electron transfer and enzyme activity. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2022, 10, 108069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, F.; Zeng, Z.; Zhang, W.; Li, H.; Zhou, L.; Zhuang, W.-Q. Functional bacteria and their genes encoding for key enzymes in hydrogen-driven autotrophic denitrification with sulfate loading. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 440, 140901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Tang, M.; He, L.; Xiao, X.; Yang, F.; He, Q.; Sun, S.; Gao, Y.; Zhou, L.; Li, Y.; et al. Exploring the impact of fulvic acid on electrochemical hydrogen-driven autotrophic denitrification system: Performance, microbial characteristics and mechanism. Bioresour. Technol. 2024, 412, 131432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Lin, L.; Xing, G.; Jiang, Y.; Cao, W.; Zhang, Y. Interspecies electron transfer and microbial interactions in a novel Fe (II)-mediated anammox coupled mixotrophic denitrification system. Bioresour. Technol. 2024, 403, 130852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Li, A.; Szewzyk, U.; Ma, F. Improvement of biological nitrogen removal with nitrate-dependent Fe (II) oxidation bacterium Aquabacterium parvum B6 in an up-flow bioreactor for wastewater treatment. Bioresour. Technol. 2016, 219, 624–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lai, C.-Y.; Zhou, L.; Yuan, Z.; Guo, J. Hydrogen-driven microbial biogas upgrading: Advances, challenges and solutions. Water Res. 2021, 197, 117120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, P.; Li, W.; Ren, S.; Peng, Y.; Wang, Y.; Feng, M.; Guo, K.; Xie, H.; Li, J. Use of sponge iron as an indirect electron donor to provide ferrous iron for nitrate-dependent ferrous oxidation processes: Denitrification performance and mechanism. Bioresour. Technol. 2022, 357, 127318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Chen, X.; Yang, T.; Zhu, H.; He, Z.; Zhao, R.; Chen, Y. Sponge iron enriches autotrophic/aerobic denitrifying bacteria to enhance denitrification in sequencing batch reactor. Bioresour. Technol. 2024, 407, 131097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teal, T.K.; Lies, D.P.; Wold, B.J.; Newman, D.K. Spatiometabolic stratification of Shewanella oneidensis biofilms. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2006, 72, 7324–7330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, I.; Cha, D.K. Effect of low temperature on abiotic and biotic nitrate reduction by zero-valent Iron. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 754, 142410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, S.; Ni, J.; Ma, T.; Li, C. Heterotrophic nitrification and aerobic denitrification at low temperature by a newly isolated bacterium, Acinetobacter sp HA2. Bioresour. Technol. 2013, 139, 80–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, M.; Winkler, M.K.H.; Volcke, E.I.P. Elucidating the Competition between Heterotrophic Denitrification and DNRA Using the Resource-Ratio Theory. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2020, 54, 13953–13962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, D.; Chen, P.; Yang, G.; Niu, R.; Bai, Y.; Cheng, K.; Huang, G.; Liu, T.; Li, X.; Li, F. Fe(II) Oxidation Shaped Functional Genes and Bacteria Involved in Denitrification and Dissimilatory Nitrate Reduction to Ammonium from Different Paddy Soils. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2023, 57, 21156–21167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luz Cayuela, M.; Angel Sanchez-Monedero, M.; Roig, A.; Hanley, K.; Enders, A.; Lehmann, J. Biochar and denitrification in soils: When, how much and why does biochar reduce N2O emissions? Sci. Rep. 2013, 3, 1732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiu, H.; Zhao, W.; Qin, Y.; Wang, Y.; Bai, M.; Su, S.; Wang, C.; Zhao, Z. Ammonia-oxidizing activity and microbial structure of ammonia-oxidizing bacteria, ammonia-oxidizing archaea and complete ammonia oxidizers in biofilm systems with different salinities. Bioresour. Technol. 2025, 423, 132248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krueger, M.; Chaudhari, N.; Thamdrup, B.; Overholt, W.A.; Bristow, L.A.; Taubert, M.; Kuesel, K.; Jehmlich, N.; von Bergen, M.; Herrmann, M. Differential contribution of nitrifying prokaryotes to groundwater nitrification. ISME J. 2023, 17, 1601–1611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Huo, Y.; Qi, F.; Zhang, Y.; Li, R.; Qiao, M. Biochar-supported microbial systems: A strategy for remediation of persistent organic pollutants. Biochar 2025, 7, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.; Xin, X.; Li, S.; Zhou, J.; Zhu, T.; Mueller, C.; Cai, Z.; Wright, A.L. Effects of Fe oxide on N transformations in subtropical acid soils. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, srep08615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, D.; Yu, Z.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, R.; Hao, J.; Feng, Y. Differences in the efficiency and mechanisms of different iron-based materials driving synchronous nitrogen and phosphorus removal. Environ. Res. 2025, 268, 120706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramanathan, B.; Boddicker, A.M.; Roane, T.M.; Mosier, A.C. Nitrifier Gene Abundance and Diversity in Sediments Impacted by Acid Mine Drainage. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 2136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcelino, V.R.; Verbruggen, H. Multi-marker metabarcoding of coral skeletons reveals a rich microbiome and diverse evolutionary origins of endolithic algae. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 31508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, J.; He, Y.; Zhao, H.; Yang, H.; Li, Q.; Chen, R.; Li, Y.-Y. Biochar mediated microbial synergy in Partial nitrification-anammox systems: Enhancing nitrogen removal efficiency and stability. Front. Environ. Sci. Eng. 2025, 19, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdulatti, A.; Zhao, B.; Xie, F.; Cui, Y.; Yue, X. Approach enhancing nitrate removal from actual municipal wastewater by integrating electric-magnetic field with Fe0 in UMSR reactor. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2024, 333, 125646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.L.; Zhou, Q.W.; Wang, L.L.; Wan, B.; Yang, Q.N. How Biochar Addition Affects Denitrification and the Microbial Electron Transport System (ETSA): A Meta-Analysis Based on a Global Scale. Agriculture 2024, 14, 2320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, M.Y.; Savio, F.; Kjaergaard, C.; Jensen, M.M.; Kovalovszki, A.; Smets, B.F.; Valverde-Pérez, B.; Zhang, Y.F. Inorganic bioelectric system for nitrate removal with low N2O production at cold temperatures of 4 and 10 °C. Water Res. 2025, 274, 123061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Huang, Y.T.; Ji, H.F.; Nie, X.J.; Zhang, Z.Y.; Ge, C.; Luo, A.C.; Chen, X. Treatment of turtle aquaculture effluent by an improved multi-soil-layer system. J. Zhejiang Univ. Sci. B 2015, 16, 145–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Yu, J.X.; Chen, Y.C.; Li, X.J.; Zhang, Z.Y.; Xiao, C.Q.; Fang, Z.; Chi, R. The adsorption mechanism of NH4+ on clay mineral surfaces: Experimental and theoretical studies. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2025, 354, 128521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayadi, M.; Farasati, M.; Mahmoodlu, G.M.; Rostamicharati, F. Removal of Nitrate, Ammonium, and Phosphate from Water Using Conocarpus and Paulownia Plant Biochar. Iran. J. Chem. Chem. Eng. Int. Engl. Ed. 2020, 39, 205–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, C.; Wang, B.; Hassan, M.; Xu, H.; Wang, X. Removal mechanisms of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in biochar and its effects on plant growth. J. Environ. Sci. 2025, 158, 309–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Wang, N.; Wang, Y.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Qi, G.; Dong, H.; Wang, H.; Zhang, X.; Li, X. Inhibitory Effects of Biochar on N2O Emissions through Soil Denitrification in Huanghuaihai Plain of China and Estimation of Influence Time. Sustainability 2024, 16, 5813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, W.; Bao, Z.; Meng, J.; Chen, T.; Liang, X. Biochar Makes Soil Organic Carbon More Labile, but Its Carbon Sequestration Potential Remains Large in an Alternate Wetting and Drying Paddy Ecosystem. Agronomy 2025, 15, 1547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, F.; Mu, Z.; Zhang, C.; Deng, L.; Zhang, X.; Sun, Y.; Liu, H.; Zhang, X.; Tabassum, S.; Liu, H. A comprehensive review on nature-inspired redox systems based on humic acids: Bridging microbial electron transfer and high-performance supercapacitors. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2026, 156, 101563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, R.; Huang, D.; Xu, X.; Yang, F. Optimal algae species inoculation strategy for algal-bacterial granular sludge: Sludge characteristics, performance and microbial community. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 370, 123011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, R.; Duan, J.; Shi, X.; Zhang, Y.; Guan, F.; Sand, W.; Hou, B. Extracellular Polymeric Substances and Biocorrosion/Biofouling: Recent Advances and Future Perspectives. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 5566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.