Abstract

Availability of irrigation water during growing seasons in the Republic of South Africa (RSA) remains a significant concern. Persistent droughts and unpredictable rainfall patterns attributed to climate change, coupled with an increasing population, have exacerbated irrigation water scarcity. Globally, treated wastewater has been utilised as an irrigation water source; however, despite global advances in the usage of treated wastewater, its suitability for irrigation in RSA remains a contentious issue. Considering this uncertainty, this review article aims to unravel the South African scenario on the suitability of treated wastewater for irrigation purposes and highlights the potential environmental impacts and public health risks. The review synthesised literature in the last two decades (2000–present) using Web of Science, ScienceDirect, ResearchGate, and Google Scholar databases. Findings reveal that treated wastewater can serve as a viable irrigation source in the country, enhancing various soil parameters, including nutritional pool, organic carbon, and fertility status. However, elevated levels of salts, heavy metals, and microplastics in treated wastewater resulting from insufficient treatment of wastewater processes may present significant challenges. These contaminants might induce saline conditions and increase heavy metals and microplastics in soil systems and water bodies, thereby posing a threat to public health and potentially causing ecological risks. Based on the reviewed literature, irrigation with treated wastewater should be implemented on a localised and pilot basis. This review aims to influence policy-making decisions regarding wastewater treatment plant structure and management. Stricter monitoring and compliance policies, revision of irrigation water standards to include emerging contaminants such as microplastics, and intensive investment in wastewater treatment plants in the country are recommended. With improved policies, management, and treatment efficiency, treated wastewater can be a dependable, sustainable, and practical irrigation water source in the country with minimal public health risks.

1. Introduction

Water scarcity is a global phenomenon, and South Africa (RSA) is not an exception. South Africa receives an average annual precipitation of approximately 450 mm, which is below the global average of 860 mm. Importantly, around 50% of this rainfall occurs on 15% of the land, contributing to the increased water scarcity in most areas in the country [1]. Thus, alternative irrigation sources, such as treated wastewater (TWW), are a potentially viable option for enhancing agricultural productivity in the country. Usage of TWW as an irrigation source is recommended by the United Nations as a feasible and sustainable strategy to mitigate against irrigation water scarcity [2,3]. Treated wastewater is also recognised as a potential water source for multiple applications in RSA to mitigate the water crisis in the country, aimed at alleviating water usage in agriculture and improving freshwater supply to the growing population [4]. In RSA, water scarcity is a persistent problem, with reports suggesting that, under the current conditions, the RSA water deficit level will increase to 17% by 2030 [5]. As such, water scarcity will continue to be a principal challenge for farmers in the country, unless alternative options such as treated wastewater are explored.

To mitigate the increase in water-deficient levels, the RSA government has developed a National Water and Sanitation Master Plan, which provides priority actions that need to be implemented by 2030 to improve water supply and reduce demand in the country [6]. The policy documents which guide water reuse in the country include the National Water Resource Strategy II, the Water and Sanitation Management Master Plan, and the National Water Reuse Strategy. Under the water and sanitation management strategy, the government aims to improve water supply and reduce water demand. Consequently, wastewater reuse has been identified as a viable approach to achieve the 2030 target [6]. The primary focus of the framework documents is to augment the diversity of water sources in the country; hence, the policy documents consider treated effluents, rainwater, greywater, and stormwater as potential alternative water sources in the country. However, currently, the water reuse implementation and integration to improve the water supply programme is behind the 2030 schedule, as South Africa is currently using around 14% of water for reuse [7]. As such, RSA needs to hasten the implementation of the policy documents to increase water reuse and subsequently increase freshwater supply to the growing population.

The agricultural sector in RSA utilises roughly 60% of water suitable for ecological purposes, totalling approximately 8.4 billion cubic metres (m3) [8,9]. As such, to improve the water supply for irrigation amid persistent droughts and capricious rainfall patterns due to climate change, the agricultural sector needs to consider alternative irrigation sources such as treated effluents. There are roughly 824 municipal wastewater treatment plants in the country with a capacity to treat approximately 6500 million litres per day (MLD) of wastewater. Additionally, it is estimated that the potential water reuse capacity in the country is around 2500 MLD [4]. As such, treated effluents can be a viable and dependable source for irrigation water in the country, as water scarcity is a principal challenge for the agricultural sector. Furthermore, RSA is faced with substantial food insecurity, with 26% of households facing food insecurity and 28% of households at risk of hunger [10]. As such, utilisation of TWW as an irrigation source might alleviate irrigation water scarcity as the predominant challenge for food production and improve food security in the country; additionally, it could reduce the environmental drawbacks associated with the discharge of treated effluent into water bodies. Thus, the primary objective of this review is to assess the suitability of treated wastewater for irrigation purposes in RSA, whilst reporting on the observed environmental impacts on soil, plants, and freshwater resources, as well as potential public health risks.

2. Review Approach

This review was developed via a comprehensive analysis of existing literature on the impact of treated wastewater for irrigation in South Africa, with particular focus on soil, crops, and water bodies.

2.1. Literature Search Strategy

The authors conducted desktop research and the literature was primarily sourced from various databases, including Google Scholar, ScienceDirect, ResearchGate, and Web of Science, using the following keywords (Figure 1) in line with the study`s thematic focus. The search strings were adapted to each database’s functionality, while maintaining consistent thematic intent.

“Treated wastewater South Africa”; “Irrigation with treated wastewater in South Africa”; “Treated Municipal wastewater as an irrigation in South Africa”; “Reclaimed wastewater South Africa”; “Effects treated wastewater in South Africa on the aquatic life”; ‘Effects of treated wastewater on soil quality and health”; “Accumulation of heavy metals post irrigation with treated wastewater”; “Effects of irrigation with treated wastewater on soil fertility”; “Treated effluents disposal on public health risks”; “Bioaccumulation of heavy metals due to irrigation with treated wastewater”; “Wastewater treatment efficacy in South Africa”; “Effects of microplastics in soil and crop”; “Effects of microplastics on soil quality and health”; and “Effects of treated wastewater discharge on water bodies in South Africa”.

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Studies from the last two decades (2000-present) are included, while studies before 2000 are excluded. This was performed to highlight the current knowledge on the usage of treated wastewater as an irrigation source in RSA. The encompassing range of the literature included peer-reviewed articles, review articles, and book chapters, which were sought primarily from various databases; no preprint literature and blog articles were included. For agricultural crop production, literature from irrigation with winery wastewater was included, as the utilisation of winery wastewater as an irrigation source is predominant in the Western Cape region of South Africa for the production of vineyards. The appraisal of environmental drawbacks was extended to the discharge of treated effluents into water bodies and aquatic life.

2.3. Limitations of the Methodology Guideline Framework Used

The temporal exclusion criterion was the only quality appraisal employed during the construction of this review article; as such, this review article does not claim to provide a thorough synthesis of all available evidence. The selected literature was discussed in line with the study’s thematic focus. As such, the review prioritised thematic focus over quantitative search metrics.

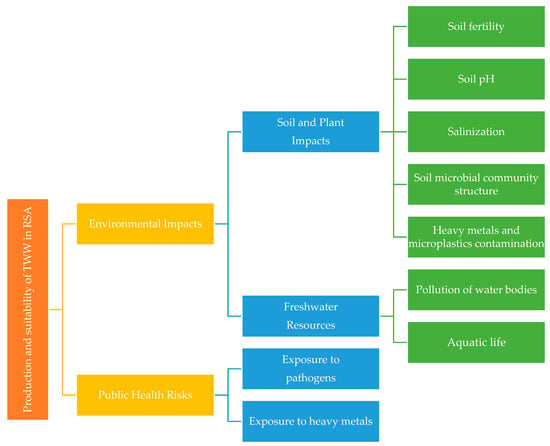

The review begins with an introduction highlighting water scarcity in RSA and recognition of treated wastewater as a water source in the country. The review proceeds to highlight treated wastewater production in RSA compared to the global production and their suitability for irrigation based on the RSA irrigation water guidelines. The two main themes of this review are the environmental impacts and public health risks due to irrigation with treated wastewater. The environmental impact sub-theme includes soil, plants, and water resource impacts. The public health risk impact sub-theme includes exposure to pathogens and heavy metals. The schematic illustration (Figure 2) provides the structure for the review articles. Treated effluents and treated wastewater are used interchangeably in this paper.

Figure 1.

Word-cloud visualisation illustrating dominant research themes.

Figure 2.

Schematic illustration of themes and structure for the review.

3. Treated Wastewater Production in South Africa Compared to the Global Trends and Their Suitability for Irrigation

Globally, mammoth quantities of TWW are generated annually; as such, TWW can be considered a reliable source of irrigation water. It is estimated that approximately 3.14 trillion m3 of municipal wastewater is released annually, with roughly 50% of municipal wastewater released being produced in the USA, Brazil, China, India, Indonesia, Japan, and Russia [11,12]. Zhang and Shen [13] reported that the global release of wastewater is approximately 400 billion m3. While in India, approximately 26 km3 of wastewater is released annually [14]. In South Africa, around 3.54 billion m3 of TWW was produced in 2009. In contrast to the production in 2000, the 2009 production increased by 342 million m3 [15]. Recent data indicate that RSA in 2022 collected roughly 2.77 billion m3 of treated effluents; however, about 10 million m3 was directly utilised for irrigation [16]. As such, the large pool of TWW produced in RSA might offer a viable and reliable alternative to irrigation water and eliminate water scarcity as a principal challenge for crop production in the country. However, the suitability of treated effluents for irrigation purposes might vary with each region where it is being produced, due to variation in influent constituents, climatic conditions, soil, and crop type.

In RSA, physical filtration, chlorine treatment, and pond and lagoon wastewater treatment techniques are widely utilised [17,18,19]. Hence, the suitability of treated effluents for irrigation varies greatly. The RSA irrigation water guidelines regarding water pH, sodium absorption ratio, total solids, suspended solids, and faecal coliform are provided in Table 1, and TWW can be analysed concerning these RSA irrigation water thresholds to determine their suitability for irrigation purposes [20]. However, different crops have different irrigation water requirements and tolerance thresholds of water conditions and induced soil conditions. Therefore, assessing the suitability of TWW for irrigation requires an assessment of its impact on soil health and sustainability, as well as the specific crop to be cultivated and its tolerance thresholds.

Table 1.

RSA irrigation water guidelines [20].

Several studies in South Africa have appraised the suitability of treated effluents for irrigation purposes [21,22,23,24,25]. Odjadjare et al. [21] observed that the physicochemical properties of treated effluent pH, TDS, nitrogen (N), orthophosphate (P), chemical oxygen demand, and electrical conductivity (EC) were within the thresholds for agricultural usage. However, the poor microbial qualities disqualified the suitability of treated effluents for agricultural usage. Kgopa et al. [22] concluded that the disposed treated effluents of Mankweng wastewater treatment plant, Limpopo province, were suitable for irrigation as the treated effluents’ pH, Calcium (Ca), Magnesium (Mg), and Sodium were within the FAO thresholds for irrigation purposes. Mulidzi et al. [23] recommended the usage of winery wastewater for agricultural irrigation in the Western Cape Province under the conditions that the application of winery wastewater should not exceed the soil water holding capacity due to the presence of salts, which might have adverse effects on soil structure in the long term. Howell et al. [24] observed a treated effluent pH and EC of 6.7–8.0 and 0.7–1.2 dS/m in Philadelphia, Western Cape Province, respectively. However, the sodium (Na) concentration in treated effluents was above the thresholds for grapevine production in RSA. Kekana et al. [25] recommended short-term specific irrigation of the Mankweng wastewater treatment plant due to the high treated effluents’ pH, and the presence of non-essential toxic elements such as Arsenic (As), Chromium (Cr), Lead (Pb), Aluminium (Al), and Cadmium (Cd) in the disposed treated effluents. Based on the previous studies, treated effluents in RSA can be utilised for irrigation for short periods. The long-term feasibility of treated effluents for irrigation is unclear and remains a bone of contention due to the presence of a myriad of contaminants in treated effluents as a result of inadequate treatment techniques [26,27]. Maleka et al. [27] concluded that wastewater treatment plants in RSA employ inadequate techniques for wastewater treatment, hence the presence of contaminants such as microplastics (MPs), HMs, and organic substances.

The increase in concentration of trace elements following the irrigation with TWW is a significant concern due to the associated health risks of trace element accumulation in the trophic system. In RSA, previous studies observed that treated effluents are contaminated with trace elements [25,26,28]. Kekana et al. [25] observed the presence of trace elements in treated effluents of the Mankweng wastewater treatment plant; however, the concentration of trace elements was within the RSA irrigation water guidelines (Table 1), except for As. Nyamukamba et al. [26] observed low removal efficiency of heavy metals for treatment plants in the Vaal triangle, Gauteng province, hence the presence of heavy metals in treated effluents. The presence of non-essential heavy metals in TWW is a major drawback to irrigation with treated effluents, as the continual application of TWW contaminated with non-essential heavy metals will most likely increase the phytoavailable pool of non-essential heavy metals in the soil, which might lead to crop uptake and subsequently accumulate in the trophic chain, as animals and humans have zero capability to biodegrade non-essential heavy metals. As such, irrigation with treated effluents might lower the public health security due to increased heavy metal concentration in the soil and trophic level.

The existing irrigation water quality standards in RSA do not account for emerging pollutants, such as microplastics, which adversely affect the extensive use of treated effluents as an irrigation source. Previous studies in the country have indicated that the treatment methods employed in RSA are insufficient for the removal of microplastics [27]. As such, irrigation with treated effluents might increase the accumulation of microplastics in the terrestrial ecosystem, as microplastics are ecologically insignificant.

4. Environmental Impact of Irrigation with Treated Effluents

The suitability of treated effluents for irrigation purposes is a contentious issue, influenced by the diverse types of wastewaters, treatment methods, and sources of influents, all of which significantly impact the appropriateness of these treated effluents for irrigation use. Hence, there is no consensus on the suitability of treated effluents to be used as an irrigation source in RSA [22,25]. The biogeochemical constituents of treated effluents vary with each type of influent source of wastewater and region where TWW is produced, thus affecting the soil, water resources, and crops differently. In contrast to the environmental drawbacks attached to the disposal of TWW, utilisation of TWW as an irrigation source is the most sustainable option.

Soil fertility status: Irrigation with treated effluents influences several soil fertility parameters, such as soil pH, soil organic carbon (SOC), EC, and nutrient status, as treated effluents contain acidic and alkaline substances, organic substances, and essential elements for crop production. Several studies conducted in RSA observed increased soil fertility parameters post-irrigation with treated effluents [23,25,29,30]. Hoogendijk et al. [30] observed increased accumulation of K, chlorine, sodium (Na), soil pH, and exchangeable Na percentage post-irrigation with TMW. Hoogendijk et al. [29] observed increased accumulation of K and Na post-irrigation with TMW. However, the increased K and Na in the soil did not affect crop growth and yield adversely, as there was no excessive crop uptake. Kekana et al. [25] observed an increase in nitrogen (N), phosphorus (P), potassium (K), soil pH, EC, and SOC over 12 weeks following irrigation with TWW. Soil pH fell outside the threshold (6.4–8.5) for crop production, and the increase in soil pH was attributed to the alkalinity of TWW used for irrigation. Mulidzi et al. [23] observed increased reserve soil acidity, SOC, K, Na, exchangeable K, and Na percentage over three years, despite seasonal fluctuations in soils irrigated with winery wastewater at various soil depths on well-drained sandy textured soils. Mulidzi et al. [23] further observed the accumulation of salts in the subsoil, which leached due to the application of high volumes of winery wastewater and rainfall, and concluded that the accumulation of the salts in the subsoil can lead to poor soil structure in the long term and might create toxic soil conditions for crop production. Howell et al. [24] observed increased concentration of N post-irrigation with TMW; however, the low N content in TMW was not sufficient to supply the annual N requirement of grapevines (Vitis vinifera). Musazura et al. [31] observed a significant increase in soil N and P post-irrigation with treated effluents within the soil depth of 30 cm; however, the increased N and P in the soil did not significantly correlate to banana (Musa paradisiaca) and taro (Colocasia esculenta) uptake. Nevertheless, the improved soil nutrient pool and SOC post-irrigation with treated effluents can improve the soil ecosystem service and reduce the over-reliance of agricultural production on chemical fertilisers; thus, reducing the cost of agricultural inputs for crop production, particularly for subsistence and smallholder farmers, and reducing the environmental drawbacks attached to the usage of fertilisers on the ecosystem.

In 2022, RSA utilised approximately 234.477, 321.499, and 541.671 tons of nutrient potash, phosphate, and nitrogen for agricultural usage, respectively [32]. The application of chemical fertilisers can improve the soil nutritional pool, contributing to a successful cropping season. However, the use of chemical fertilisers negatively impacts soil health by reducing soil microbial diversity, which in turn adversely affects crop health and yield [33,34]. Furthermore, the application of fertilisers enhances soil acidification and crusting, negatively impacting the beneficial microbes in the soil, and consequently affecting the soil health index [35,36]. Nevertheless, application of fertilisers is essential for crop productivity, as irrigation with TWW might lead to a deficient soil nutritional pool. Tak et al. [37] observed that application of K at a lower dosage (20 kg/ha) with irrigated wastewater performed better in crop traits such as growth, photosynthesis, and stomatal conductance, relative to high dosage application under irrigation with wastewater (60 kg/ha). This implies that the application of low doses of chemical fertilisers coupled with wastewater irrigation can be sufficient for successful crop production.

Excessive chemical fertiliser application is associated with environmental drawbacks such as eutrophication, which jeopardises the food web by deteriorating the aquatic biodiversity. Additionally, excessive fertiliser application can elevate soil-borne pathogens and soil acidification, thus resulting in poor crop development and nutrient imbalances in the soil as different nutrients are phytoavailable at different soil pH, consequently leading to yield loss and operational loss [38]. As such, irrigation with treated effluents might enhance crop productivity in the agricultural sector and its commitment to sustainable food productivity, and limit the drawbacks associated with chemical fertiliser application. However, the fate of essential nutrients added via irrigation with treated effluents is a function of soil pH.

Soil pH: The increase in soil pH coupled with EC following the irrigation with TWW in RSA is a potential drawback to irrigation with treated effluents, as the soil pH influences a myriad of biogeochemical reactions in the soil [24,28,30]. Hence, soil pH is considered a master variable, as it dictates the fate of essential nutrients in soil. Soil pH affects microbially driven processes such as nitrification, denitrification, mineralisation of soil organic matter (SOM), enzyme kinetics, and surface charge density on clay minerals, which subsequently influence crop uptake of essential nutrients [39]. Under acidic conditions, nitrate bioavailability is low due to diminished nitrification rate, hence crop uptake of ammonium [40]. Additionally, under acidic conditions, the P bioavailability is hindered due to strong bonds with Al and iron (Fe), while under alkaline conditions, P tends to form insoluble calcium phosphate due to the dominance of calcium in the soil solution. As such, P tends to be bioavailable at soil pH of near neutral pH (6–7) [41]. Furthermore, the bioavailability of K is indirectly proportional to soil pH; as soil pH increases, the availability of K decreases [42]. As such, the increase in soil pH post-irrigation with treated effluents might reduce the phytoavailability of nutrients, leading to poor crop development and yields. The increase in soil pH also influences the dynamics of surface charges.

Soil colloids carry surface charges, which can be permanent or variable. The permanent charges remain the same regardless of soil pH, while the variable charges fluctuate with soil pH [43]. Under acidic conditions, the pH-dependent surface charges tend to be more positive; while, under alkaline conditions, soil surface charge density tends to be more negative. Cao et al. [44] reported that the surface negative charge density of goethite, which is a clay mineral found in variably charged soils and oxidic soils, diminished significantly from 3.19 cmol/kg to 0 (zero) in soil pH conditions that declined from 10.9 to 7.8. The isoelectric point is paramount in highly weathered soil such as oxisols, which constitute mainly variable charges, as it determines the adsorption of ions on the soil colloids. According to Yu [45], Fe and Al oxides, as well as hydrated oxides, are the main contributors of variable charges in the soil. Zhuang and Yu [46] stated that the Fe oxide coats on the soil colloids increase the point of zero charge to a higher soil pH value. Cornell and Schwertmann [47] stated that the point of zero charge of Fe oxides ranges between soil pH of 6–10, and Fe oxides increase the positive charge in the soil. Moreover, the soil pH influences microbially driven processes such as enzyme kinetics and microbial diversity.

Under acidic conditions of less than 4.5, the soil microbial activity is hindered, and the fungal–bacteria ratio is high [48]. Additionally, the virulence of soil-borne pathogens on crop development is also influenced by soil pH. Soil-borne pathogens such as Plasmodiophora brassicae and Streptomyces scabies, which cause clubroot and common scab of potatoes, are virulent at soil pH of 5.7 and 5.2–8, respectively. However, Plasmodiophora brassicae and Streptomyces scabies occurrence drops significantly at soil pH of 5.7–6.2, and below soil pH of 5.2, respectively [49]. The carbon (C), N, and P cycling enzyme kinetics are also influenced by soil pH. Liu et al. [50] attributed the decline in the activity of β-1,4 glucosidase, N-acetyl-β-d-glucosidase, leucine aminopeptidase, and acid phosphatase to reduced soil pH. However, there is no consensus on the impact of treated effluents on soil pH, as the constituents of treated effluents are temporally variable, hence the lack of consensus. Nevertheless, the increase in soil pH following irrigation with treated effluents observed in previous studies can hinder crop productivity. Additionally, the increase in soil pH is a potential drawback to long-term application of treated effluents as an irrigation source, as the increase in soil pH is correlated with salinity, which is detrimental to the soil structure, crop production, and soil ecosystem services rendered.

Salinization: Salinization can be detrimental to crop production, soil ecosystem services, and, subsequently, public health security [51,52,53]. Approximately 1 billion hectares (ha) worldwide are affected by saline conditions [54,55]. In RSA, approximately 32% of the soils are saline, and 20% of irrigated soils are saline [56]. According to Hu and Schmidhalter [57], the drawbacks of salinization include low economic returns due to poor crop performance and yield, hence the low agricultural output. Under saline conditions, phytoavailable P diminishes significantly due to precipitation with Ca ions, leading to nutritional imbalances which adversely affect crop growth [58,59]. Furthermore, the increased accumulation of Na in saline soil can lead to excessive accumulation in the crop cell walls, which can induce osmotic stress and subsequently cell death in crops [60]. The essential crop processes, such as photosynthesis, are also affected by salinity via reduction in leaf area, chlorophyll content, and stomatal conductance, hence the impaired concentration of photosynthesis assimilates to the growing crop tissues [61]. Additionally, salinity affects soil structure through dispersion and flocculation of soil particles. The breaking down of soil aggregate is mainly due to increased thickness of diffuse double layers; however, basic cations such as Ca and Magnesium (Mg) can initiate clay flocculation, which in turn initiates soil aggregate formation [61,62,63]. As such, the increased accumulation of salts following irrigation with treated effluents in RSA is a major concern, as increased salinity can be detrimental to agricultural productivity, environmental resources, and human health [23,29,30].

Soil microbial community structure: Irrigation with TWW may augment the soil microbial diversity and biomass. The soil microbial community influences several essential ecosystem functions such as nutrient cycling, organic matter breakdown, and influxes of gases in the soil [64,65,66]. The soil microbial biomass is mainly influenced by the soil organic matter, while the soil microbial diversity is mainly influenced by the soil pH [67,68,69,70,71]. In contrast to the alkaline and acidic soil pH conditions, the microbial diversity is greatest at neutral soil pH [72,73]. The solubility of essential nutrients in varying soil pH conditions influences microbial diversity. Under alkaline conditions, the low solubility of P tends to decrease the bacterial diversity [74]. Soil microbial biomass is used as a soil quality indicator, as microbial biomass serves several soil ecosystem functions which include nutrient sink, nutrient mineralisation, and biodegradation of toxic substances [75]. The increased SOC coupled with essential nutrients following irrigation with TWW might lead to enhanced enzyme activities, microbial biomass, and increased abundance of beneficial microbial functional groups such as N-fixing, nitrifying and denitrifying bacteria, and carbon decomposers, thus enhancing soil nutrient and carbon cycling. Ibekwe et al. [2] found that soils irrigated with treated wastewater had a high microbial functional abundance compared to soils irrigated with synthetic freshwater. The abundance of Pseudomonas, Acinetobacter, nitrifying bacteria, and Legionella were in soils irrigated with TWW compared to freshwater irrigated soils. However, there was no significant difference in microbial diversity between soils irrigated with TWW and freshwater. Nevertheless, the increase in SOC observed post-irrigation with treated effluents can enhance the soil ecosystem functions and services, by inducing favourable soil conditions for crop growth, such as increased CEC, microbial biomass, and root–microbe interactions. However, treated effluents contain various microbial constituents which may adversely affect soil health, and pose a threat to soil quality, function, and sustainability.

Several studies in RSA observed the presence of Escherichia coli, faecal enterococci, Salmonella typhimurium, Shigella dysenteriae, Vibrio cholerae, and Enterococcus spp. in treated effluents [76,77,78]. As such, irrigation with treated effluents might increase the soil pathogenic community structure, thus reducing soil quality for agricultural productivity and public health security in RSA. Previous studies observed an increase in soil microbial community structure after irrigation with treated effluents [79,80,81]. However, the severity of soil-borne pathogens is influenced by several factors, including soil pH, temperature, SOC, moisture level, salinity, and crop type. Jechalke et al. [82] reported that Salmonella colonisation kinetics on crops were affected by the soil type, Salmonella strain, and crop species. Additionally, it was reported that organic fertilisers enhance the persistence of Salmonella in the soil. Ma et al. [83] reported that the persistence of E. coli O157:H7 was positively correlated with labile OC and negatively with soil salinity. Furthermore, leafy crops throughout the growing season tend to be in contact with soil and are susceptible to contamination [84]. As such, microbial contaminants, SOC, salinity, and soil pH might lead to varying observations regarding pathogenic persistence in soils irrigated with treated effluents and severity of their virulence in RSA.

Heavy metal and microplastic contamination: Kekana et al. [25] observed that TWW in Mankweng was contaminated with heavy metals, and irrigation with TWW enhanced soil heavy metal concentration. The non-biodegradability of heavy metals ensures that these metals persist in soil for a long time. However, heavy metals can be categorised into essential and non-essential heavy metals. For example, Copper (Cu) and Zinc (Zn) are crucial for photosynthesis and respiration, form part of enzyme systems, seed formation, protein and RNA synthesis, and production of growth hormones [85,86,87,88]. While heavy metals such as Mercury (Hg), Arsenic (As), Cadmium (Cd), Lead (Pb), Chromium (Cr), and Aluminium (Al) do not have an ecological significance and are toxic to the crops; their contamination in the soil might induce acute or chronic ecological health. Thus, hindered soil ecosystem functions and services quality might be rendered by the soil contaminated with heavy metals due to low soil productivity, functionality, and metabolic activity of soil microbiome, as heavy metals inhibit OM breakdown and formation, nutrient cycling, enzyme activities, and the development of metal resistance microbes [89,90]. Li et al. [91] reported that heavy metals reduce the soil diversity and richness of functional microbes. Ma et al. [92] reported that the abundance of Actinobacteria and Archaea, and carbon fixation were adversely affected by heavy metal stress, while the relative abundance of Proteobacteria and N metabolism increased. As such, enhanced heavy metal concentration post-irrigation with TWW in RSA might present a serious ecological challenge, especially when utilised for a long period.

According to Maleka et al. [27], wastewater treatment plants in RSA inadequately remove microplastics in wastewater. As such, irrigation with such water will most likely increase the concentration of microplastics in both soil and plant system post-irrigation with TWW, which is detrimental to soil health and crop health, hindering sustainable usage of TWW. Accumulation of microplastics in soil adversely affects soil porosity, bulk density, infiltration, water holding capacity, and increases soil compaction, leading to reduced root growth, low nutrient and water uptake, and reduced crop yield [93,94,95]. The accumulation of microplastics in soil also leads to reduced functional microbial diversity and abundance, which in turn diminishes organic matter breakdown and nutrient cycling, ultimately reducing the overall soil fertility [96,97]. De Souza Machado et al. [97] observed that microplastic contamination reduced SOC by 5–10% due to disruption in OM breakdown. In contrast, Fei et al. [96] observed that the addition of microplastics in soil enhanced Burkholderiaceae bacterial family, urease, and acid phosphatase activities, while inhibiting the bacterial abundance of Sphingomonadaceae and Xanthobacteraceae families, which play a pivotal role in biodegradation of organic pollutants. Additionally, microplastics may act as a transport vector of contaminants [98]. As such, the presence of microplastics in TWW might increase the ecotoxicity of TWW for irrigation purposes due to drawbacks associated with the accumulation of microplastics in the soil system.

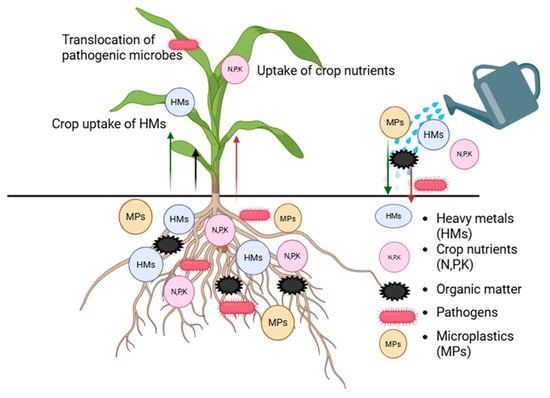

Treated wastewater in RSA is contaminated with various substances ranging from crop nutrients such as N, P, and K, as well as non-essential substances such as heavy metals and microplastics, along with pathogens, resulting in varying impacts (Figure 3). The nutrients, heavy metals, and organic matter introduced through irrigation with treated wastewater will likely enhance crop absorption, while the extra organic matter is expected to increase soil ecosystem functionality. The pathogens introduced through irrigation with TWW will enhance soil microbial diversity. However, their virulence will be contingent upon soil conditions and crop species, and they may translocate to the shoots, constituting a public health risk.

Figure 3.

Fate of contaminants added through irrigation with treated wastewater.

5. Treated Effluents on Freshwater Sources

Pollution of water bodies due to discharge: The discharge of poorly treated effluents negatively affects the freshwater source for human consumption and ecological usage. In RSA, the surface water bodies are the main source of water supply. Hence, the release of improperly treated effluents compromises the quality of water available for ecological and human consumption. The low quality of treated effluents is mainly due to infrastructure failure because of a lack of maintenance [99]. The National Water Act protects the freshwater resources concerning both consumption and pollution, and as such, the discharge of poorly treated effluents into the ecosystem is against the RSA legislation. The pollution of freshwater sources is mainly due to treatment plants not adhering to the country`s norms, standards, and policies regarding wastewater treatment [100,101]. The wastewater treatment plants in the country have a constrained budget, hence the lack of maintenance. Ntombela et al. [102] stated that in 2012/13, approximately 50% of treatment plants were issued with purple drop, which indicates poor management. Additionally, the report states that in 2015, there were roughly 19 reported cases of treated effluent overflowing the water sources, thus suggesting that the water sources were polluted by the overflowing treated effluents and posed an ecological health risk.

Treated effluents contain nutrients, microbes, and heavy metals; their discharge can cause environmental challenges such as eutrophication and microbial and heavy metal contamination in rivers and other surface water bodies. Qadir et al. [103] reported that the discharge of poorly treated effluents introduces toxic substances to the trophic system, thus degrading both the terrestrial and aquatic environment, hence their unsuitable usage for both agricultural production and other ecological uses. Thus, the UN recommended the use of TWW for irrigation as its environmental disposal is detrimental to ecological health and sustainability. Moloi et al. [104] observed that the concentration of heavy metals in treated effluents in Harrismith and Phuthaditjhaba urban centres, Free State province, was within the National Water Act. Furthermore, Moloi et al. [104] reported that the Harrismith treatment plant enriched heavy metals in the Wilge River, thus posing an ecological risk to aquatic life and the environment.

The surface water bodies in developing regions are mostly utilised without any form of treatment [105]. In RSA, surface water bodies are the main source of water supply to the population, and the discharge of treated effluents into the ecosystem might cause freshwater pollution due to inadequate wastewater treatment. Phungela et al. [106] concluded that Crocodile River contamination in Mpumalanga province is due to the discharge of poorly treated effluents into the river system, due to the treatment plant not adhering to the norms, standards, and regulations in the country. Herbig and Meissner [107] reported that over 60% of treatment plants are not functioning properly; hence, discharging treated effluents from such treatment plants may result in ecological contamination and public health risks. Adefisoye and Okoh [108] found that the disposed TWW in the Eastern Cape province were below quality guidelines for disposal and concluded that such water contributes to the development of drug-resistant bacteria and poses a threat to water bodies.

Teklehaimanot et al. [99] reported that water bodies in the Sedibeng and Soshanguve communities did not comply with South African regulations for domestic use, irrigation, and recreational usage by the WHO, as a result of treated effluents contamination. The presence of E. coli, faecal enterococci, and somatic coliphages disqualified the usage of the water bodies for ecological purposes such as aquaculture, agricultural production, and domestic usage. Additionally, the occurrence of pathogenic microbes such as Salmonella typhimurium, Shigella dysenteriae, and Vibrio cholerae substantiated that the usage and disposal of treated effluents into freshwater bodies posed a public health risk. Water bodies contaminated with these pathogens are most likely to cause gastrointestinal illnesses if consumed without proper treatment. Thus, the study concluded that the water bodies pose a health risk to the Sedibeng and Soshanguve communities. Previous studies, conducted in Limpopo, KwaZulu Natal (KZN), and the Eastern Cape provinces, revealed that the treatment plants in these regions are unable to deal with microbial contamination in wastewater effectively, thus leading to high faecal pollution and presence of pathogenic microbial genera [76,109]. Samie et al. [76] reported that over 90% of wastewater treatment plants in Mpumalanga province utilise chlorine for disinfection, however, less than 14% produce treated effluents with zero faecal count. Hence, the presence of Salmonella, Shigella, E. coli, and Enterococcus spp. As such, wastewater in most parts of RSA is inadequately treated, and the discharge of these inadequately treated effluents pollutes freshwater sources and poses an ecological and communal health risk.

Several studies conducted in RSA observed the presence of microplastics in treated effluents and subsequently their occurrence in the ecosystem post-discharge of treated effluents into the ecosystem [27,110]. Maleka et al. [27] observed the presence of microplastics in treated effluents across three treatment plants in Emfuleni Municipality, Gauteng Province, thus suggesting that the treatment plants have inadequate capacity to treat microplastics in wastewater. Saad et al. [110] reported the prevalent occurrence of microplastics in the Vaal River and concluded that the accumulation of microplastics poses a contamination threat in the Vaal River.

Aquatic life: Previous studies indicate that TWW in RSA is inadequately treated due to underperforming treatment plants, amplifying the ecological health risks, particularly aquatic life, such as eutrophication, microbial community structure, and buildup of anti-resistance genes [111,112]. Discharge of poorly treated wastewater is a principal contributor to total nutrient load in surface waterbodies, subsequently nutrient enrichment in water bodies, thus causing eutrophication [113,114,115]. Murgatroyd et al. [116] reported bioaccumulation of pharmaceutical compounds in sand prawns (Kraussillichirus kraussi), which serve as key endobenthic organisms in estuarine ecosystems. The discharge of inadequately treated wastewater from the treatment plant, resulting from non-compliance with legislation, negatively impacts aquatic life. Therefore, the implementation of stricter monitoring policies is essential to safeguard the aquatic ecosystem.

6. Public Health Risks

The bone of contention regarding the suitability of treated wastewater for irrigation centres on the presence of pathogenic microbes and heavy metals is that irrigation with treated effluents may increase the exposure of humans to pathogens and heavy metals, thus adversely affecting public health security.

Exposure to pathogens: Irrigation with treated effluents may augment the public exposure to pathogens, thus leading to several clinical manifestations. Previous studies have reported that effluents are not adequately treated in RSA primarily due to a lack of critical infrastructure maintenance and non-compliance of treatment plants with regulations designed to safeguard the increasing population from potential pathogen exposure [73,74,88]. The population can be exposed to pathogenic microbes in treated effluents via the consumption of raw crops irrigated with treated effluents and the consumption of freshwater contaminated by treated effluents. Lin et al. [87] stated that the surface water sources in the developing countries are utilised without treatment. As such, based on the previous reports, which indicated the presence of pathogenic microbes in treated wastewater, the utilisation of treated effluents as an irrigation source is most likely to augment public exposure to pathogens and diminish public health security.

Exposure to enteric pathogens, including E. coli, can lead to diarrhoea and extraintestinal diseases [117]. Clinical signs resulting from Salmonella exposure include fever, septicemia, and abdominal pain. Globally, there are roughly 0.2–1 billion annual Salmonella infections and 155,000 deaths [118]. Clinical manifestations associated with Shigella dysenteriae exposure include fever and gastrointestinal disorders, particularly in underdeveloped regions. Shigella-induced diarrhoea remains a significant source of diarrhoea and is still a cause of mortality and morbidity in children below 5 years [119]. As such, the presence of pathogens in treated effluents lowers their suitability for irrigation purposes on a large scale due to the potential public health risks which may emerge as a result of their usage. However, the suitability of treated effluents to be used as an irrigation source can be enhanced by taking into consideration the irrigation system, applied amount, crop, and soil type. Cakmakci and Sahin [120] observed that different irrigation methods (subsurface drip, surface drip, and flood irrigation) had varying effects on maize under varying deficit wastewater irrigation. Subsurface drip irrigation was established as a feasible option for the irrigation of maize with wastewater due to increased crop yield. As such, subsurface drip irrigation might be viable to ensure the minimal transfer of pathogenic microbes to crops.

Exposure to heavy metals: Utilisation of TWW as an irrigation source may augment the exposure of the public to heavy metals through the consumption of crops contaminated with these metals or augment heavy metal contamination in underground water reservoirs. Thus, irrigation with TWW may increase the phytoavailable pool of heavy metals in the soil, leading to crop uptake and phytoaccumulation. Maliehe et al. [121] observed that metals in Mankweng, Limpopo province, were within the permissible threshold for drinking, except for Pb, which exceeded the WHO limits. Edokpayi et al. [122] found that groundwater exceeds the permissible risk limit for individuals, with Cr and Pb having the highest carcinogenic risk exposure in Muledane area, Vhembe District, Limpopo Province. Irrigation with treated wastewater may increase the heavy metal contamination in the underground water bodies, potentially resulting in the bioaccumulation of these metals in human bodies upon intake. This results in several clinical manifestations, including skin and lung cancer, Alzheimer’s disease, and renal failure, due to the carcinogenic, mutagenic, and reprotoxic effects of heavy metals [123,124,125]. As such, the presence of heavy metals in treated effluent is a major drawback, as the application will increase their accumulation on the trophic level and reduce public health security.

Table 2 provides a brief synthesis of the environmental impacts and public health risks associated with the usage of TWW for irrigation purposes in RSA. Emphasis is placed on soil biogeochemical response to irrigation with TWW, effects of TWW discharge on freshwater resources, and public health. The synthesis provided in Table 2 underscores the critical need for effective wastewater treatments in RSA, site-specific management, and regulatory compliance to enhance the benefits of TWW irrigation in RSA while mitigating long-term environmental degradation and public health risks.

Table 2.

Consolidated summary table highlighting the impacts of irrigation with TWW in RSA.

7. Conclusions and Recommendations

Treated effluents are a feasible option for crop productivity in RSA; nevertheless, inadequate investment in wastewater treatment plants infrastructure hinders the production of treated wastewater that meets RSA irrigation water thresholds. Evidence from previous studies revealed that TWW improve soil fertility, crop productivity, and soil ecosystem functioning. However, elevated soil pH, salinity, heavy metals, microplastics, and pathogenic microbes in TWW threaten soil health, crop productivity, and public health security. Additionally, freshwater bodies and public health security are threatened by pathogenic microbial and heavy metal exposure. As such, based on the evidence provided by previous studies, the usage of treated effluents for irrigation purposes should be performed on a piloted and localised basis, where TWW can be monitored regularly, and soil and crop conditions can be taken into consideration. Future research should focus on crop-specific and site-specific potential usage of TWW to enhance their long-term sustainable usage. Moreover, updated irrigation water standards should include emerging contaminants such as microplastics. Strict policy implementation measures and intentional investment drives should occur to ensure long-term reliability and sustainability of TWW for irrigation purposes to support the agricultural sector and to protect the environment and public health security.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, writing—original draft preparation, I.K.J.K.; conceptualization, student supervision, writing—review and editing and fund acquisition, P.M.K.; student co-supervision, writing—review and editing, fund acquisition, K.K.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The research to conduct this study was funded by the National Research Foundation Grant-Thuthuka TTK220323583. The funders on this research had no role in study design, data collection, data analysis, interpretation or writing this review.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analysed in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Botai, C.M.; Botai, J.O.; Adeola, A.M. Spatial distribution of temporal precipitation contrasts in South Africa. S. Afr. J. Sci. 2018, 114, 70–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibekwe, A.M.; Gonzalez-Rubio, A.; Suarez, D.L. Impact of treated wastewater for irrigation on soil microbial communities. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 622, 1603–1610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vergine, P.; Salerno, C.; Libutti, A.; Beneduce, L.; Gatta, G.; Berardi, G.; Pollice, A. Closing the water cycle in the agro-industrial sector by reusing treated wastewater for irrigation. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 164, 587–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalebaila, N.; Ncube, E.J.; Swartz, C.D.; Marias, S.; Lubbe, J. Strengthening the Implementation of Water Reuse in South Africa, Gezina; Water Research Commission Report TT 742/1/18; Water Research Commission: Pretoria, South Africa, 2020; Available online: https://wrc.org.za/?mdocs-file=60799 (accessed on 14 May 2025).

- WWF-SA. Scenarios for the Future of Water in South Africa. 2017. Available online: https://awsassets.wwf.org.za/downloads/wwf_scenarios_for_the_future_of_water_in_south_africa.pdf (accessed on 24 April 2025).

- Department of Water and Sanitation. National Water and Sanitation Master Plan; Volume 1: Call to Action; Department of Water and Sanitation: Pretoria, South Africa, 2018.

- Van Niekerk, A.M.; Schneider, B. Implementation plan for direct and indirect water re-use for domestic purposes–Sector Discussion Document. WRC Rep. No. KV 2013, 320, 13. [Google Scholar]

- Stevens, J.; van Koppen, B. Trends and Outlook: Agricultural Water Management in Southern Africa; Country Report-South Africa; Project Report Submitted to United States Agency for International Development’s (USAID’s) Feed the Future Program; International Water Management Institute: Pretoria, South Africa, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Donnenfeld, Z.; Hedden, S.; Crookes, C. A Delicate Balance: Water Scarcity in South Africa; Southern Africa Report 13; Institute for Security Studies: Pretoria, South Africa; Frederick S. Pardee Centre for International Futures: Denver, CO, USA; Josef Korbel School of International Studies: Denver, CO, USA; University of Denver: Denver, CO, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Chakona, G.; Shackleton, C.M. Food insecurity in South Africa: To what extent can social grants and consumption of wild foods eradicate hunger? World Dev. Perspect. 2019, 13, 87–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motshumi, K.K.; Mbangi, A.; Van Der Wat, E.; Khetsha, Z.P. Phytoremediation Potential of Silicon-Treated Brassica juncea L. Mining-Affected Water and Soil. Composites in South Africa: A Review. Agriculture 2025, 15, 1582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mateo-Sagasta, J.; Raschid-Sally, L.; Thebo, A. Global wastewater and sludge production, treatment and use. In Wastewater: Economic Asset in an Urbanizing World; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2015; pp. 15–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Shen, Y. Wastewater irrigation: Past, present, and future. WIREs Water 2019, 6, e1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minhas, P.S.; Saha, J.K.; Dotaniya, M.L.; Sarkar, A.; Saha, M. Wastewater irrigation in India: Current status, impacts and response options. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 808, 152001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, T.; Qadir, M.; Yamamoto, S.; Endo, T.; Zahoor, A. Global, regional, and country level need for data on wastewater generation, treatment, and use. Agric. Water Manag. 2013, 130, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO AQUASTAT. Global Information System on Water and Agriculture. 2025. Available online: http://www.fao.org/nr/water/aquastat/main/index.stm (accessed on 1 August 2025).

- Edokpayi, J.N.; Odiyo, J.O.; Popoola, O.E.; Msagati, T.A. Evaluation of contaminants removal by waste stabilization ponds: A case study of Siloam WSPs in Vhembe District, South Africa. Heliyon 2021, 7, e06207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makuwa, S.; Tlou, M.; Fosso-Kankeu, E.; Green, E. Evaluation of fecal coliform prevalence and physicochemical indicators in the effluent from a wastewater treatment plant in the north-west province, South Africa. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 6381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dungeni, M.; van Der Merwe, R.R.; Momba, M. Abundance of pathogenic bacteria and viral indicators in chlorinated effluents produced by four wastewater treatment plants in the Gauteng Province, South Africa. Water SA 2010, 36, 607–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Department of Water Affairs and Forestry. South African Water Quality Guidelines, 2nd ed.; Volume 1: Domestic Water Use; Department of Water Affairs and Forestry: Pretoria, South Africa, 1996.

- Odjadjare, E.; Igbinosa, E.O.; Okoh, A.I. Microbial and physicochemical quality of an urban reclaimed wastewater used for irrigation and aquaculture in South Africa. Afr. J. Microbiol. Res. 2011, 5, 2179–2186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kgopa, P.M.; Mashela, P.W.; Manyevere, A. Suitability of treated wastewater with respect to pH, electrical conductivity, selected cations and sodium adsorption ratio for irrigation in a semi-arid region. Water SA 2018, 44, 551–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulidzi, A.R.; Clarke, C.E.; Myburgh, P.A. Response of soil chemical properties to irrigation with winery wastewater on a well-drained sandy soil. S. Afr. J. Enol. Vitic. 2019, 40, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howell, C.L.; Hoogendijk, K.; Myburgh, P.A.; Lategan, E.L. An assessment of treated municipal wastewater used for irrigation of grapevines with respect to water quality and nutrient load. S. Afr. J. Enol. Vitic. 2022, 43, 168–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kekana, I.K.J.; Kgopa, P.M.; Munjonji, L. Bioremediation of Non-Essential Toxic Elements Using Indigenous Microbes in Soil Following Irrigation with Treated Wastewater. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 2299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyamukamba, P.; Moloto, M.J.; Tavengwa, N.; Ejidike, I.P. Evaluating physicochemical parameters, heavy metals, and antibiotics in the influents and final effluents of South African wastewater treatment plants. Pol. J. Environ. Stud. 2019, 28, 1305–1312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maleka, T.; Greenfield, R.; Muniyasamy, S.; Modley, L. Vaal’s Microplastic Burden: Uncovering the Fate of Microplastics in Emfuleni Municipality’s Wastewater Treatment Systems, Gauteng, South Africa. Sustainability 2025, 17, 2211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olujimi, O.O.; Fatoki, O.S.; Odendaal, J.P.; Oputu, O.U. Variability in heavy metal levels in river water receiving effluents in Cape Town, South Africa. In Research and Practices in Water Quality; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2015; pp. 193–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoogendijk, K.; Myburgh, P.A.; Howell, C.L.; Lategan, E.L.; Hoffman, J.E. Effect of irrigation with treated municipal wastewater on Vitis vinifera L. cvs. Cabernet Sauvignon and Sauvignon blanc in commercial vineyards in the Coastal Region of South Africa-Vegetative growth, yield and juice characteristics. S. Afr. J. Enol. Vitic. 2023, 44, 126–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoogendijk, K.; Myburgh, P.A.; Howell, C.L.; Lategan, E.L.; Hoffman, J.E. Long-term Effects of Irrigation with Treated Municipal Wastewater on Soil Chemical and Physical Responses in Commercial Vineyards in the Coastal Region of South Africa. S. Afr. J. Enol. Vitic. 2024, 45, 8–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musazura, W.; Odindo, A.O.; Tesfamariam, E.H.; Hughes, J.C.; Buckley, C.A. Nitrogen and phosphorus dynamics in plants and soil fertigated with decentralised wastewater treatment effluent. Agric. Water Manag. 2019, 215, 55–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAOSTAT Database. Food and Agriculture Data. 2025. Available online: https://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#data (accessed on 28 April 2025).

- Huang, X.; Liu, L.; Wen, T.; Zhu, R.; Zhang, J.; Cai, Z. Illumina MiSeq investigations on the changes of microbial community in the Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. cubense infected soil during and after reductive soil disinfestation. Microbiol. Res. 2015, 181, 33–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, C.; Ryan Penton, C.; Zhu, C.; Chen, H.; Duan, Y.; Peng, C.; Guo, S.; Ling, N.; Shen, Q. Alterations in soil fungal community composition and network assemblage structure by different long-term fertilization regimes are correlated to the soil ionome. Biol. Fertil. Soils 2018, 54, 95–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozlu, E.; Kumar, S. Response of soil organic carbon, pH, electrical conductivity, and water stable aggregates to long-term annual manure and inorganic fertilizer. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 2018, 82, 1243–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pahalvi, H.N.; Rafiya, L.; Rashid, S.; Nisar, B.; Kamili, A.N. Chemical fertilizers and their impact on soil health. In Microbiota and Biofertilizers, Vol 2: Ecofriendly Tools for Reclamation of Degraded Soil Environs; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tak, H.I.; Babalola, O.O.; Huyser, M.H.; Inam, A. Urban wastewater irrigation and its effect on growth, photosynthesis and yield of chickpea under different doses of potassium. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2013, 59, 156–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Ye, C.; Su, Y.; Peng, W.; Lu, R.; Liu, Y.; Huang, H.; He, X.; Yang, M.; Zhu, S. Soil Acidification caused by excessive application of nitrogen fertilizer aggravates soil-borne diseases: Evidence from literature review and field trials. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2022, 340, 108176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neina, D. The role of soil pH in plant nutrition and soil remediation. Appl. Environ. Soil Sci. 2019, 2019, 5794869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zebarth, B.J.; Forge, T.A.; Goyer, C.; Brin, L.D. Effect of soil acidification on nitrification in soil. Can. J. Soil Sci. 2015, 95, 359–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devau, N.; Le Cadre, E.; Hinsinger, P.; Jaillard, B.; Gérard, F. Soil pH controls the environmental availability of phosphorus: Experimental and mechanistic modelling approaches. Appl. Geochem. 2009, 24, 2163–2174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.; Han, T.; Huang, J.; Asad, S.; Li, D.; Yu, X.; Huang, Q.; Ye, H.; Hu, H.; Hu, Z.; et al. Links between potassium of soil aggregates and pH levels in acidic soils under long-term fertilization regimes. Soil Tillage Res. 2020, 197, 104480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schofield, R.K. Effect of pH on electric charges carried by clay particles. Eur. J. Soil Sci. 1950, 1, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, H.; Liu, X.; Feng, B.; Sun, J.; Ma, D.; Chen, X.; Li, H. Effect of pH on the surface charges of permanently/variably charged soils and clay minerals. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 23169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, H.; Liu, C.; Li, Z. Chemistry of soil-type dependent soil matrices and its influence on behaviors of pharmaceutical compounds (PCs) in soils. Heliyon 2023, 9, e22931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, J.; Yu, G. Effects of surface coatings on electrochemical properties and contaminant sorption of clay minerals. Chemosphere 2002, 49, 619–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornell, R.M.; Schwertmann, U. The Iron Oxides: Structure, Properties, Reactions, Occurrences, and Uses; John Wiley & Sons: Weinheim, Germany, 2003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rousk, J.; Brookes, P.C.; Bååth, E. Contrasting soil pH effects on fungal and bacterial growth suggest functional redundancy in carbon mineralization. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2009, 75, 1589–1596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thakur, R.; Verma, S.; Gupta, S.; Negi, G.; Bhardwaj, P. Role of soil health in plant disease management: A review. Agric. Rev. 2022, 43, 70–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Gan, B.; Li, Q.; Xiao, W.; Song, X. Effects of nitrogen and phosphorus addition on soil extracellular enzyme activity and stoichiometry in Chinese fir (Cunninghamia lanceolata) forests. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 834184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, D. Osmotic stress adaptations in rhizobacteria. J. Basic Microbiol. 2013, 53, 101–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, P.; Bogunovic, I.; Muñoz-Rojas, M.; Brevik, E.C. Soil ecosystem services, sustainability, valuation and management. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sci. Health 2018, 5, 7–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuevas, J.; Daliakopoulos, I.N.; del Moral, F.; Hueso, J.J.; Tsanis, I.K. A review of soil-improving cropping systems for soil salinization. Agronomy 2019, 9, 295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metternicht, G.I.; Zinck, J.A. Remote sensing of soil salinity: Potentials and constraints. Remote Sens. Environ. 2003, 85, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yensen, N.P. Halophyte uses for the twenty-first century. In Ecophysiology of High Salinity Tolerant Plants; Tasks for Vegetation Science; Khan, M.A., Weber, D.J., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2006; pp. 367–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehlers, L.; Barnard, J.H.; Dikgwatlhe, S.B.; Van Rensburg, L.D.; Ceronio, G.M.; Du Preez, C.C.; Bennie, A. Effect of Irrigation Water and Water Table Salinity on the Growth and Water Use of Selected Crops; Water Research Commission Report No 1359/1/07. Water Research Commission: Pretoria, South Africa, 2007. Available online: https://www.wrc.org.za/wp-content/uploads/mdocs/1359-1-071.pdf (accessed on 13 August 2025).

- Hu, Y.; Schmidhalter, U. Limitation of salt stress to plant growth. In Plant Toxicology; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2004; pp. 205–238. [Google Scholar]

- Ashraf, M. Some important physiological selection criteria for salt tolerance in plants. Flora Morphol. Distrib. Funct. Ecol. Plants 2004, 199, 361–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bano, A.; Fatima, M. Salt tolerance in Zea mays (L). following inoculation with Rhizobium and Pseudomonas. Biol. Fertil. Soils 2009, 45, 405–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munns, R. Comparative physiology of salt and water stress. Plant Cell Environ. 2002, 25, 239–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Netondo, G.W.; Onyango, J.C.; Beck, E. Sorghum and salinity: II. Gas exchange and chlorophyll fluorescence of sorghum under salt stress. Crop Sci. 2004, 44, 806–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pihlap, E.; Steffens, M.; Kögel-Knabner, I. Initial soil aggregate formation and stabilisation in soils developed from calcareous loess. Geoderma 2021, 385, 114854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbaslou, H.; Hadifard, H.; Ghanizadeh, A.R. Effect of cations and anions on flocculation of dispersive clayey soils. Heliyon 2020, 6, e03462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastida, F.; García, C.; Fierer, N.; Eldridge, D.J.; Bowker, M.A.; Abades, S.; Alfaro, F.D.; Asefaw Berhe, A.; Cutler, N.A.; Gallardo, A. Global ecological predictors of the soil priming effect. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 3481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crowther, T.W.; Van den Hoogen, J.; Wan, J.; Mayes, M.A.; Keiser, A.D.; Mo, L.; Averill, C.; Maynard, D.S. The global soil community and its influence on biogeochemistry. Science 2019, 365, eaav0550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado-Baquerizo, M.; Reich, P.B.; Trivedi, C.; Eldridge, D.J.; Abades, S.; Alfaro, F.D.; Bastida, F.; Berhe, A.A.; Cutler, N.A.; Gallardo, A. Multiple elements of soil biodiversity drive ecosystem functions across biomes. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2020, 4, 210–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dequiedt, S.; Saby, N.P.; Lelievre, M.; Jolivet, C.; Thioulouse, J.; Toutain, B.; Arrouays, D.; Bispo, A.; Lemanceau, P.; Ranjard, L. Biogeographical patterns of soil molecular microbial biomass as influenced by soil characteristics and management. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 2011, 20, 641–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomson, B.C.; Tisserant, E.; Plassart, P.; Uroz, S.; Griffiths, R.I.; Hannula, S.E.; Buée, M.; Mougel, C.; Ranjard, L.; Van Veen, J.A. Soil conditions and land use intensification effects on soil microbial communities across a range of European field sites. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2015, 88, 403–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horrigue, W.; Dequiedt, S.; Prévost-Bouré, N.C.; Jolivet, C.; Saby, N.P.; Arrouays, D.; Bispo, A.; Maron, P.; Ranjard, L. Predictive model of soil molecular microbial biomass. Ecol. Ind. 2016, 64, 203–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terrat, S.; Horrigue, W.; Dequietd, S.; Saby, N.P.; Lelièvre, M.; Nowak, V.; Tripied, J.; Régnier, T.; Jolivet, C.; Arrouays, D. Mapping and predictive variations of soil bacterial richness across France. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0186766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimi, B.; Terrat, S.; Dequiedt, S.; Saby, N.P.; Horrigue, W.; Lelièvre, M.; Nowak, V.; Jolivet, C.; Arrouays, D.; Wincker, P. Biogeography of soil bacteria and archaea across France. Sci. Adv. 2018, 4, eaat1808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fierer, N.; Jackson, R.B. The diversity and biogeography of soil bacterial communities. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2006, 103, 626–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malard, L.A.; Anwar, M.Z.; Jacobsen, C.S.; Pearce, D.A. Biogeographical patterns in soil bacterial communities across the Arctic region. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2019, 95, fiz128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nautiyal, C.S.; Bhadauria, S.; Kumar, P.; Lal, H.; Mondal, R.; Verma, D. Stress induced phosphate solubilization in bacteria isolated from alkaline soils. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2000, 182, 291–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dalal, R.C. Soil microbial biomass—What do the numbers really mean? Aust. J. Exp. Agric. 1998, 38, 649–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samie, A.; Obi, C.L.; Igumbor, J.O.; Momba, M. Focus on 14 sewage treatment plants in the Mpumalanga Province, South Africa in order to gauge the efficiency of wastewater treatment. Afr. J. Biotechnol. 2009, 8, 3276–3285. [Google Scholar]

- Teklehaimanot, G.Z.; Coetzee, M.A.; Momba, M.N. Faecal pollution loads in the wastewater effluents and receiving water bodies: A potential threat to the health of Sedibeng and Soshanguve communities, South Africa. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2014, 21, 9589–9603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kgopa, P.M.; Mashela, P.W.; Manyevere, A. Microbial quality of treated wastewater and borehole water used for irrigation in a semi-arid area. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 8861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frenk, S.; Hadar, Y.; Minz, D. Resilience of soil bacterial community to irrigation with water of different qualities under Mediterranean climate. Environ. Microbiol. 2014, 16, 559–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wafula, D.; White, J.R.; Canion, A.; Jagoe, C.; Pathak, A.; Chauhan, A. Impacts of long-term irrigation of domestic treated wastewater on soil biogeochemistry and bacterial community structure. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2015, 81, 7143–7158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farhadkhani, M.; Nikaeen, M.; Yadegarfar, G.; Hatamzadeh, M.; Pourmohammadbagher, H.; Sahbaei, Z.; Rahmani, H.R. Effects of irrigation with secondary treated wastewater on physicochemical and microbial properties of soil and produce safety in a semi-arid area. Water Res. 2018, 144, 356–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jechalke, S.; Schierstaedt, J.; Becker, M.; Flemer, B.; Grosch, R.; Smalla, K.; Schikora, A. Salmonella establishment in agricultural soil and colonization of crop plants depend on soil type and plant species. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Ibekwe, A.M.; Crowley, D.E.; Yang, C. Persistence of Escherichia coli O157: H7 in major leafy green producing soils. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2012, 46, 12154–12161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carstens, C.K.; Salazar, J.K.; Darkoh, C. Multistate outbreaks of foodborne illness in the United States associated with fresh produce from 2010 to 2017. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 2667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Li, J.; Han, H.; Du, R.; Wang, X. Physiological and molecular mechanisms of plant responses to copper stress. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 12950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamzah Saleem, M.; Usman, K.; Rizwan, M.; Al Jabri, H.; Alsafran, M. Functions and strategies for enhancing zinc availability in plants for sustainable agriculture. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 1033092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Umair Hassan, M.; Aamer, M.; Umer Chattha, M.; Haiying, T.; Shahzad, B.; Barbanti, L.; Nawaz, M.; Rasheed, A.; Afzal, A.; Liu, Y. The critical role of zinc in plants facing the drought stress. Agriculture 2020, 10, 396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saboor, A.; Ali, M.A.; Hussain, S.; El Enshasy, H.A.; Hussain, S.; Ahmed, N.; Gafur, A.; Sayyed, R.Z.; Fahad, S.; Danish, S. Zinc nutrition and arbuscular mycorrhizal symbiosis effects on maize (Zea mays L.) growth and productivity. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2021, 28, 6339–6351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nurzhan, A.; Tian, H.; Nuralykyzy, B.; He, W. Soil enzyme activities and enzyme activity indices in long-term arsenic-contaminated soils. Eurasian Soil Sci. 2022, 55, 1425–1435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Z.; Shi, J.; He, Y.; Wu, L.; Xu, J. Assembly of root-associated bacterial community in cadmium contaminated soil following five-year consecutive application of soil amendments: Evidences for improved soil health. J. Hazard. Mater. 2022, 426, 128095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Quan, Q.; Gan, Y.; Dong, J.; Fang, J.; Wang, L.; Liu, J. Effects of heavy metals on microbial communities in sediments and establishment of bioindicators based on microbial taxa and function for environmental monitoring and management. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 749, 141555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, S.; Qiao, L.; Liu, X.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, L.; Qiu, Z.; Yu, C. Microbial community succession in soils under long-term heavy metal stress from community diversity-structure to KEGG function pathways. Environ. Res. 2022, 214, 113822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rillig, M.C.; Lehmann, A.; de Souza Machado, A.A.; Yang, G. Microplastic effects on plants. New Phytol. 2019, 223, 1066–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boots, B.; Russell, C.W.; Green, D.S. Effects of microplastics in soil ecosystems: Above and below ground. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2019, 53, 11496–11506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Souza Machado, A.A.; Lau, C.W.; Till, J.; Kloas, W.; Lehmann, A.; Becker, R.; Rillig, M.C. Impacts of microplastics on the soil biophysical environment. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2018, 52, 9656–9665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fei, Y.; Huang, S.; Zhang, H.; Tong, Y.; Wen, D.; Xia, X.; Wang, H.; Luo, Y.; Barceló, D. Response of soil enzyme activities and bacterial communities to the accumulation of microplastics in an acid cropped soil. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 707, 135634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Souza Machado, A.A.; Lau, C.W.; Kloas, W.; Bergmann, J.; Bachelier, J.B.; Faltin, E.; Becker, R.; Görlich, A.S.; Rillig, M.C. Microplastics can change soil properties and affect plant performance. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2019, 53, 6044–6052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, Y.; Gao, M.; Qiu, W.; Song, Z. Uptake of microplastics by carrots in presence of As (III): Combined toxic effects. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 411, 125055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tempelhoff, J.; Munnik, V.; Viljoen, M. The Vaal River barrage, South Africa’s hardest working water way: An historical contemplation. J. Transdiscipl. Res. S. Afr. 2007, 3, 107–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Merwe-Botha, M. Water Quality: A Vital Dimension of Water Security; Development Planning Division; Working Paper No 14; DBSA: Midrand, South Africa, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Herold, C. The water crisis in South Africa. In Proceedings of the 14th Sanciahs Symposium, Pietermaritzburg, South Africa, 21–23 September 2009; University of KwaZulu-Natal: Pietermaritzburg, South Africa, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Ntombela, C.; Funke, N.; Meissner, R.; Steyn, M.; Masangane, W. A critical look at South Africa’s green drop programme. Water SA 2016, 42, 703–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qadir, M.; Wichelns, D.; Raschid-Sally, L.; McCornick, P.G.; Drechsel, P.; Bahri, A.; Minhas, P.S. The challenges of wastewater irrigation in developing countries. Agric. Water Manag. 2010, 97, 561–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moloi, M.; Ogbeide, O.; Voua Otomo, P. Probabilistic health risk assessment of heavy metals at wastewater discharge points within the Vaal River Basin, South Africa. Int. J. Hyg. Environ. Health 2020, 224, 113421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, L.; Yang, H.; Xu, X. Effects of water pollution on human health and disease heterogeneity: A review. Front. Environ. Sci. 2022, 10, 880246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phungela, T.T.; Maphanga, T.; Chidi, B.S.; Madonsela, B.S.; Shale, K. The impact of wastewater treatment effluent on Crocodile River quality in ehlanzeni district, Mpumalanga province, South Africa. S. Afr. J. Sci. 2022, 118, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herbig, F.J. Talking dirty-effluent and sewage irreverence in South Africa: A conservation crime perspective. Cogent Soc. Sci. 2019, 5, 1701359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adefisoye, M.A.; Okoh, A.I. Ecological and public health implications of the discharge of multidrug-resistant bacteria and physicochemical contaminants from treated wastewater effluents in the Eastern Cape, South Africa. Water 2017, 9, 562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Momba, M.; Mfenyana, C. Inadequate treatment of wastewater: A source of coliform bacteria in receiving surface water bodies in developing countries—Case study: Eastern Cape Province of South Africa. Water Encycl. 2005, 1, 661–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saad, D.; Ramaremisa, G.; Ndlovu, M.; Chimuka, L. Morphological and chemical characteristics of microplastics in surface water of the Vaal River, South Africa. Environ. Process. 2024, 11, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agboola, O.A.; Downs, C.T.; O’Brien, G. Macroinvertebrates as indicators of ecological conditions in the rivers of KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Ecol. Ind. 2019, 106, 105465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sibanda, T.; Selvarajan, R.; Tekere, M. Urban effluent discharges as causes of public and environmental health concerns in South Africa’s aquatic milieu. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2015, 22, 18301–18317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lukhele, T.; Msagati, T.A.M. Eutrophication of inland surface waters in South Africa: An overview. Int. J. Environ. Res. 2024, 18, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Germishuys, R.; Diamond, R. Nitrogen isotopes of Eichhornia crassipes (water hyacinth) confirm sewage as leading source of pollution in Hartbeespoort Reservoir, South Africa. S. Afr. J. Sci. 2022, 118, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffin, N.J.; Palmer, C.G.; Scherman, P.A. Critical Analysis of Environmental Water Quality in South Africa: Historic and Current Trends; Water Research Commission Report No. 2184/1/14; Water Research Commission: Pretoria, South Africa, 2014; Available online: https://www.wrc.org.za/wp-content/uploads/mdocs/2184-1-14.pdf (accessed on 13 October 2025).

- Murgatroyd, O.; Petrik, L.; Ojemaye, C.Y.; Pillay, D. Persistent Pharmaceuticals in a South African Urban Estuary and Bioaccumulation in Endobenthic Sandprawns (Kraussillichirus kraussi). Water 2025, 17, 2289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Croxen, M.A.; Law, R.J.; Scholz, R.; Keeney, K.M.; Wlodarska, M.; Finlay, B.B. Recent advances in understanding enteric pathogenic E. coli. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2013, 26, 822–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chlebicz, A.; Śliżewska, K. Campylobacteriosis, salmonellosis, yersiniosis, and listeriosis as zoonotic foodborne diseases: A review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenkins, C. Shigella. In Encyclopedia of Food and Health; Caballero, B., Finglas, P.M., Toldrá, F., Eds.; Academic Press: Oxford, UK, 2016; pp. 785–789. [Google Scholar]

- Cakmakci, T.; Sahin, U. Improving silage maize productivity using recycled wastewater under different irrigation methods. Agric. Water Manag. 2021, 255, 107051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maliehe, T.S.; Mavingo, N.; Selepe, T.N.; Masoko, P.; Mashao, F.M.; Nyamutswa, N. Quantitative assessment of human health risks associated with heavy metal and bacterial pollution in groundwater from Mankweng in Limpopo Province, South Africa. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2024, 21, 1489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edokpayi, J.N.; Enitan, A.M.; Mutileni, N.; Odiyo, J.O. Evaluation of water quality and human risk assessment due to heavy metals in groundwater around Muledane area of Vhembe District, Limpopo Province, South Africa. Chem. Cent. J. 2018, 12, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, Y.; Song, K.; Chung, J. Health effects of chronic arsenic exposure. J. Prev. Med. Public Health 2014, 47, 245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geng, H.; Wang, L. Cadmium: Toxic effects on placental and embryonic development. Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2019, 67, 102–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dasharathy, S.; Arjunan, S.; Maliyur Basavaraju, A.; Murugasen, V.; Ramachandran, S.; Keshav, R.; Murugan, R. Mutagenic, carcinogenic, and teratogenic effect of heavy metals. eCAM 2022, 2022, 8011953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]