Abstract

In the review, the collection of population genetics papers from 1973 to 2025 comprises 400 publications, 81 of which were significant and consulted with representatives from water and sewage companies. Reviewed Proteobacteria (mean HS = 0.42), Firmicutes (mean HS = 0.43), Actinobacteria (mean HS = 0.33), and Spirochaetes (mean HS = 0.54) represent the 60 species under investigation through the lens of “h” coefficients related to gene diversity and expected heterozygosity. The research also included ESKAPE, emerging pathogens, bacterial indicators of wastewater treatment efficiency, environmental sanitary surveillance and public health. The restoration of the expected heterozygosity for haploids “h” was proposed in wastewater-based epidemiology as an innovative tool for public health. The unique “h” coefficient allows for the comparison of genetic variability in various organisms, regardless of their ploidy, using multiple markers and traits. The parameter represents a noble character for both the variability of phenotypes (proteins) and genotypes (nucleic acids). Leveraging the genetic diversity highlighted by the “h” coefficient can support wastewater-based epidemiology, offering the ability to predict the stages and trajectories of disease outbreaks.

1. Genetic Diversity Coefficients in Bacteria as a Support for WBE Action

The data on the genetic structure of bacterial populations, as described by population genetics methods, are often fragmented. This lack of consolidation is primarily due to the historical focus on a one-dimensional medical approach to epidemiological research. Initially, this approach aimed to identify species-specific markers quickly, especially for pathogenic bacterial groups [1,2]. Consequently, most analyses have concentrated on selected and characteristic polymorphisms of sequences. Moreover, the search for universal species-specific markers does not necessitate the application of population genetics parameters on the bacteria being examined. The application of population genetic methods has been limited, particularly concerning the genetic variability of archaebacteria. In the case of eubacteria, gene diversity profiles have been obtained for about 40 species from over 100 well-characterized bacterial genomes [3,4]. Most data related to enzymatic loci testing reveal the protein-level diversity among bacteria. Over the past four decades, many new parameters of genetic diversity based on DNA markers have been recognized, and new sequencing approaches have been developed [5,6,7]. The significance of these molecular tools extends to preventing disease, prolonging life, promoting public physical and mental health, improving personal and environmental hygiene, controlling disease factors, and organizing healthcare. Additionally, the last three decades have underscored the importance of bacterial genetics, bioinformatics, and molecular epidemiology in supporting public health [8,9]. Furthermore, open data sources, such as those from used water and wastewater treatment, have become crucial for monitoring biological factors, particularly in the field of wastewater-based epidemiology (WBE) [10].

Molecular epidemiology encompasses a range of activities, techniques, and methodological approaches aimed at gathering materials and information about the occurrence and behavior of biological factors, such as bacteria [11]. This information is crucial for developing countermeasures and procedures when an epidemic is suspected. Subsequently, epidemiological monitoring is conducted regularly, employing standardized methods for data collection, storage, and processing [12]. Various environmental elements are monitored, including air, groundwater, surface water, seawater, coastal water, transitional water, wastewater, and sludge [13,14]. Sewage contains over 21 families of bacteria that may be pathogenic to human health. Additionally, Wu et al. [15] identified one billion microbial phylotypes, including 28 operational taxonomic units (OTUs), in the microbiome of activated sludge systems. Understanding the population structure of specific epidemiological factors can enhance the flow of information from collection points to databases and ultimately to physicians or epidemiologists, especially when mitigation actions are necessary. The increasing presence of multi-, extended-, and pan-drug-resistant strains of Escherichia coli, Salmonella/Shigella, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Acinetobacter baumanii, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and other enteric bacteria (collectively referred to as ESKAPE) is becoming a growing concern [16,17]. At the same time, Directive (EU) 2024/3019 emphasizes the importance of assessing emerging diseases, particularly their surveillance algorithms. The continuous emergence of new traits in environmental bacteria, their expanding host range, and levels of pathogenicity are partially driven by anthropogenic pressures, including the increasing volume of solid waste, sewage, and pharmaceuticals in the environment [18,19].

There are many markers of interest for whole bacterial community evaluation (WBE), particularly those related to proteins and genes that promote resistance to chemotherapy [20]. These markers, which can include mobile elements that are either dispersed or clustered and may be organized as pathogenic islands or multitasking operons [21], flow into wastewater treatment plants from municipal or agricultural sources. After undergoing treatment—ideally through activated sludge processes—they are released directly into water bodies. There is still limited knowledge regarding the potential presence of ESKAPE organisms in wastewater, including their genetic sequences and fragmented material, which may pose environmental risks [22]. Furthermore, there is an urgent need to gather data on the quality and quantity of Legionella species (including L. pneumophila) present in effluent from wastewater treatment plants, especially in light of legislative requirements that promote the reuse of treated wastewater [23,24].

To recognize genetic changes in bacterial populations, population genetics parameters are effectively utilized [25,26,27]. Estimating genetic variability at the species or population level is based on allele frequency (P), the percentage of polymorphic loci (A), and the degree of expected heterozygosity (HT or HS) [28,29]. The coefficient of expected heterozygosity, calculated from allele frequency—especially for haploids—allows for the comparison of variation levels among evolutionarily distant organisms, even if they are at different ploidy stages. Because haploid organisms lack a diploid stage, the HT or HS coefficients are defined as gene diversity [30,31,32]. The HT coefficient reflects the genetic diversity of a species based on the existing polymorphism in the analyzed loci. HT values depend on the number and frequency of alleles present at these loci. The greater the number of loci with lower allele frequencies in a given species, the higher the HT value. In haploid populations, the HS parameter indicates the proportion of loci that differ between two randomly selected individuals. This means it can suggest the likelihood that the individuals differ at least at one locus. By utilizing HT and HS parameters, it is possible to calculate both the proportion of population genetic variability relative to species variability (Dst) and the inter-population variability in relation to the overall variation within the species (Gst) [30,33,34].

Epidemiology encompasses a set of methodological approaches and concepts designed to track the causes of health disorders, drawing heavily on mathematical principles [35]. The primary objective of preventive epidemic actions is to identify factors contributing to health issues, understand their nature and extent, determine how they affect different biotypes, and assess whether they are in an invasive or eradication phase [36,37]. Periodic and consequence epidemiological monitoring involves evaluating and predicting the state of the environment, as well as collecting, processing, and disseminating information about natural elements of environment. One of the most crucial natural elements is clean water, along with the wastewater produced as a byproduct of human activity. Wastewater is a complex mixture of particulate matter of varying sizes, chemical compounds, and biological factors [38]. The focus of wastewater-based epidemiology (WBE) is on wastewater generated from diverse sources, such as agricultural runoff and domestic sewage from urbanized areas. This area of study includes various biological genres, including bacteria (43), microscopic fungi (29), parasites (15), viruses (13), ciliates (7), and protists (3) that are significant to public health [39,40,41,42,43]. Among these are human pathogens and organisms that are excreted in feces and spread through sewage. These biological agents form a genetically diverse group with varying ploidy levels. Estimating key parameters for WBE, such as the levels of intra- and inter-species variability among these agents, can be valuable for monitoring wastewater treatment processes [44]. Values of heterozygosity parameters may aid in assessing different types of sedimentation parameters and saprobic indices, as well as species and genus balance. Additionally, the genetic parameters of He can help evaluate risks associated with biological agents, genome fragments, or their expression products in the environment. For instance, parameters like genetic variability and diversity (Ne, He, Gst, Dst, I, and D) can enhance database algorithms related to the effectiveness of surfactants, disinfectants, and personal protective equipment [33,45]. Routinely used parameters such as Ne, He, Gst, Dst, I, and D serve to assess genetic variability in various organisms, including plants, animals, protozoa, and microscopic fungi. Values of these parameters help track species distributions and the acquisition and loss of phenotypic traits over time. This information is crucial for implementing appropriate epidemiological and clinical measures [46]. Therefore, a comprehensive approach to the genetic variability of biological factors in wastewater is essential, focusing not only on genetic elements but also, and perhaps primarily, on phenotypic traits. Gene products resulting from the interaction of microorganisms’ genetic information with their environment remain pivotal [47]. Currently, WBE does not fully utilize the established routes of population genetics for pre-epidemic and epidemic assessments, nor does it leverage the neglected parameters in the population genetics of biological factors present in wastewater.

2. Enzymatic Diversity About Epidemiological Interest for Public Health

Pathogenic bacteria possess a widely diverse population structure—from clonal to panmictic. Mycobacterium tuberculosis and Borrelia burgdorferi populations are characterized with a clonal structure in comparison to Neisseria gonorrhoeae, Bacillus subtilis and Rhizobium meliloti [48,49,50]. Studies of enzymatic loci in Haemophilus influenzae strains that are resistant to aminoglycosides, indicate a wide range of population structure from pure clonal to pseudo panmictic [51]. Furthermore, the time of being a clone in bacterial strains is not stable. In Haemophilus influenzae that time is shorter than in Escherichia coli clones [52,53]. Pseudomonas sp., similarly to Vibrio cholerae, possesses a strong clonal structure with mechanisms that maintain such a structure up to 28 months [54,55]. Efficient correction mechanisms may maintain the clonal structure for decades despite much more frequent recombination in V. cholerae than in E. coli and Salmonella enteritica [56,57].

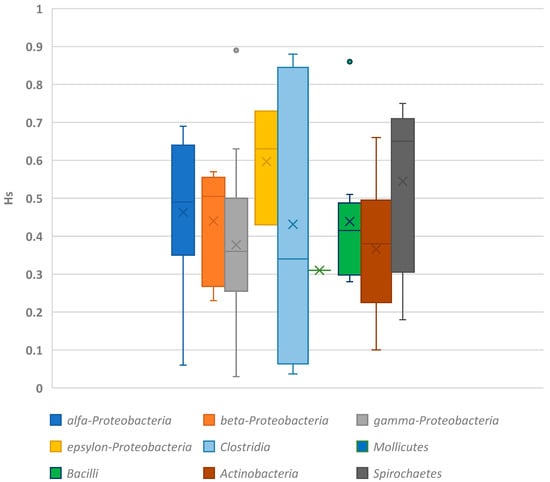

The bacteria that are most well-known for their protein variability are classified within the phylum Proteobacteria. In particular, the γ-Proteobacteria class of this phylum, which includes all human pathogens, exhibits a wide range of variability, with values ranging from HS = 0.03 to 0.89 and an average of 0.46 [58,59]. Differences in this genetic diversity parameter can be observed among families, species, and even within a single species, such as Escherichia coli. For example, the variability for different species of Pseudomonas ranges from 0.08 to 0.89, while Escherichia species show values between 0.27 and 0.52, Haemophilus sp. have values between 0.40 and 0.57, and Pasteurella sp. range from 0.29 to 0.36 (see Table 1 and Figure 1).

Table 1.

Level of genetic diversity in Proteobacteria phylum * based on aggregated enzymatic data for many different enzymes (modified from [3,4]).

Figure 1.

Values of expected heterozygosity based on enzymatic data for key group of microorganisms.

The Spirochaetes phylum exhibits the highest level of genetic variability, with a heterozygosity (HS) value of 0.54. This phylum includes several human pathogens known for their characteristic spiral cell shape. Within the second family of this phylum, the HS parameter for Serpulina species varies significantly, ranging from 0.18 to 0.62. In contrast, bacteria from the Firmicutes phylum demonstrate a lower level of genetic variability. These bacteria have strong cell membranes, similar to those found in Gram-positive organisms. Variations in HS values are observed among families, such as Aeromonas and Streptococcus, as well as among species within the Clostridium genus (Table 2) [86]. The Actinobacteria phylum shows the lowest genetic diversity, as indicated by enzymatic traits (HS = 0.33). These organisms often form specific fungal-like colonies. Among the Actinobacteria, the Mycobacteriaceae family displays notable variability, with a wide range of HS values.

Table 2.

Level of genetic diversity in Firmicutes, Actinobacteria and Spirochaetes phyla * based on aggregated enzymatic data for many different enzymes (modified from [3,4]).

One of the most variable pathogens is Helicobacter pylori. The genetic diversity coefficient (HS) obtained through isoenzyme electrophoresis was 0.74 (see Table 1). The high genetic variability of this pathogen complicates the detection of identical sequences in two unrelated strains. Frequent recombination and a lack of mechanisms to eliminate recombined genotypes result in an almost unlimited number of unique alleles [50,107]. Additionally, H. pylori strains exhibit a tendency to attach to their host, leading to the primary transmission of this bacterium within infected families (from mother to children) [50,67]. In contrast, the probability of selecting two genetically distinct strains in a given locus for Pseudomonas stutzeri, P. balearica, P. pseudoalcaligenes, and P. mendocina is highest among bacteria, with an average genetic diversity coefficient (HS) of 0.88 [55]. Pseudomonas aeruginosa is an exception within this genus; despite inhabiting a wide range of environments—being either environmental or a pathogenic bacterium—the genetic diversity coefficient is relatively low, ranging from 0.14 to 0.23 [54]. For Mycobacterium intracellulare, randomly selected bacteria differ from one another at 38 out of 100 loci (HS = 0.38), while Mycobacterium scrofulaceum shows differences at 66 out of 100 loci (HS = 0.66) [98]. A similar level of genetic variability is found in pathogenic bacteria such as Haemophilus influenzae, where the probability of choosing two cells with different alleles at the same locus ranges from 0.55 to 0.59 (average HS = 0.57) [52,53]. Randomly selected V. cholerae strains differ from one another in an average of 44% of examined enzymatic loci. Comparatively, other pathogens show variation as follows: Neisseria gonorrhoeae at 41%, Escherichia coli at 43%, Staphylococcus aureus at 29%, Legionella pneumophila at 31%, and Salmonella enteritica at 63% [78]. Within Pneumococcus, strains of different serotypes that share the same allele at every locus occur with an average frequency ranging from 3.5 to 1.6 × 10−5. Streptococcus pneumoniae exhibits a low clonal structure while displaying significant genetic diversity (H = 0.82) [86].

Recent origins, a high level of recombination in the population, and stages of expansion lead to fluctuations in genetic diversity parameters for strains of Campylobacter jejuni, Yersinia pestis, and Bacteroides fragilis, with an HS of 0.40 (SD = 0.12) [50,108]. The invasive nature and widespread distribution of C. jejuni clones, particularly the best-adapted strains, are facilitated by human activities [50]. For Pasteurella multocida and Pasteurella trehalosi populations, random cells may vary from one another in about 30 out of 100 loci (H = 0.30) [76]. Pasteurella trehalosi primarily affects the lymphatic glands of sheep and demonstrates host specificity and tissue tropism, similar to Mycobacterium tuberculosis. It is also an opportunistic bacterium, typically infecting only individuals with weakened immune systems. The low level of genetic variability and lack of significant genotypic diversity in this bacterium can be attributed to the young age of the host, a low effective population number (Ne), and rare recombinations [80]. An even lower level of genetic variability is observed in the animal pathogen Serpulina hyodysenteriae, which has a coefficient of HS = 0.28 [106]. The level of variability in E. coli, a commensal and pathogen for mammals and birds, depends on the ecological niche it occupies (see Table 3) [109].

Table 3.

Level of genetic diversity (HS) in E. coli strains in relation to origin based on enzymatic data (modified reprint from [3] with permission and based on [49,110].

3. DNA Sequence Diversity as a Valuable Indicator for Public Health and Environmental Hygiene

In addition to protein variability, bacteria exhibit a significant level of variability in their DNA sequences, which includes polymorphisms within species and among different strains. Genetic variability in the tubercle bacillus can be observed through polymorphisms of direct repeats (DR) in repeated DNA sequences [111,112]. Highly polymorphic interval sequences (DVR) vary in number and structure due to deletions and insertions, allowing for the evolution of Mycobacterium tuberculosis strains [113,114]. The polymorphism of DVR in the tubercle bacillus develops more slowly than changes in the insertion sequence IS6110, and it resembles the polymorphism observed in Streptococcus pyogenes [113]. This characteristic is useful for constructing ancestral sequences that have evolved through multiple deletions and insertions, leading to the emergence of recent strains. Furthermore, the DR regions enable the calibration of a molecular clock, which allows researchers to estimate the approximate time of evolution for specific strains [114].

Sreevatsan et al. [115] analyzed the structural gene polymorphism in Mycobacterium tuberculosis and demonstrated that this pathogen has less genetic variability compared to Shigella sonnei, suggesting it is a highly specialized pathogenic clone of Escherichia coli from a genetic perspective. The evolutionary history of some species remains unclear. For instance, based on differences in the katG and gyrA genes at both the single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) level and large sequence polymorphism (LSP), the Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex (MTB) is divided into three groups. There is ongoing debate among scientists regarding the ancestral strain of M. tuberculosis and a lack of consensus on its evolutionary strategy, rendering evolutionary considerations about MTB speculative. Restriction analyses of IS6110, DR, and PGRS have only suggested hypothetical phylogenetics for this complex. It remains uncertain whether the evolution of the M. tuberculosis complex is influenced by gene deletions in M. tuberculosis or by the acquisition (insertions) of DNA fragments from Mycobacterium bovis. In contrast, organisms like Caulobacter crescentus and Rickettsia prowazekii exhibit an evolutionary strategy characterized by significant genome size reduction through the loss of many genes [116]. This genome “simplification” is also observed in Campylobacter jejuni, which utilizes its flagella genes, flaA and flaB, as virulence factors and possesses a larger number of regulatory systems compared to, for example, Helicobacter pylori [117]. What is more, another the O157:H7 strain of E. coli has lost approximately 567 genes compared to the K-12 strain [118,119]. The evolution of Clostridium acetobutylicum is characterized by gene acquisition through horizontal gene transfer [120]. Recent findings suggest the presence of bacteria in bison 17,000 years ago that are more similar to Mycobacterium tuberculosis and Mycobacterium africanum than to Mycobacterium bovis. This evidence could support the hypothesis that the evolution of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex is influenced by gene transfer from the M. tuberculosis genome to the M. bovis genome. These findings challenge the prevailing theories that suggest tuberculosis originated from domestic cattle.

There is relatively little information available regarding the level of genetic diversity in bacteria as it relates to epidemiological studies. Some research has been conducted to understand evolutionary types, sources of virulence, and mechanisms of resistance. However, we currently lack sufficient data to compare the genetic diversity levels of pathogenic bacteria with those of environmental bacteria for these purposes. For instance, estimates of genetic diversity coefficients, HS and HT, indicate that Mycobacterium tuberculosis is more diverse than previously thought, with HS being 0.29 [28]. This finding suggests that M. tuberculosis may have a stronger epidemiological potential and a greater impact on public health than we initially expected. It is possible that a similar relationship exists, whereby higher genetic diversity (or genome plasticity) correlates with a more significant public health impact for many other bacterial species. Similarly to the case of the tubercle bacillus, the perceived image of high or low gene diversity could be revised through methods such as NGS. Subsequently, fast markers could be evaluated de novo and applied for WBE purposes (see Table 4).

Table 4.

Selected markers for WBE, water treatment technology, wastewater treatment and environmental, sanitary and hygienic surveillance other than commonly used in diagnostic tests [4].

Finally, it is important to highlight the advancements in next-generation sequencing (NGS), which have significantly reduced the time and labor intensity associated with traditional genome screening methods. With a reaction capacity of approximately 5 Gbp per 24 h, NGS can capture the E. coli genome in just 3 min, or screen the genomes of 20 different bacterial species within 5 min using compact devices like the Oxford Nanopore Technologies (ONT, Oxford, UK) MinION. Equipment such as the GridION x5 or PromethION Oxford Nanopore Technologies (ONT, Oxford, UK) enables researchers to analyze differences among 48 small genomes or check the E. coli genome 48 times in just 3 min. Additionally, there is a robust logical framework for generating well-oriented data and for the decentralized exchange of data during the planning of epidemiological countermeasures [121]. This raises an important question: why not compare the capabilities of these recent technological advancements with established concepts in population genetics and theories that have been recognized over the years? Employing a new methodological and conceptual approach will undoubtedly benefit public health, practitioners, preventive services, and medical crisis teams.

4. Conclusions

Understanding genetic variation through the universal coefficients mentioned allows us to categorize bacteria alongside other haploid and diploid organisms. The selected H coefficients, which represent genetic diversity, enable us to estimate the genetic variation in bacteria. By comparing the values of these genetic diversity coefficients, we can test hypotheses regarding the evolutionary stage of the bacteria under examination. The specific value of the H parameter helps estimate the acquisition of DNA sequences within bacterial genomes, particularly concerning traits related to drug resistance in various pathogens. This understanding is crucial in light of the widespread pan-drug resistance observed in many bacterial species today.

With the wealth of knowledge regarding various bacterial genomes and the detailed DNA sequences now accessible, it is essential to reevaluate the current estimates of genetic diversity in bacteria. Traditional DNA scanning techniques designed for diploid organisms suggest that the genetic diversity among the analyzed bacterial individuals may be nearly three times greater than what has been indicated by enzymatic estimations [122]. Furthermore, the significant genetic diversity observed in bacterial genomes within known niches may suggest genome plasticity, hidden genetic potential, and a spreading population type. In contrast, stable values of diversity coefficients could reflect the intentional use of selected strains, resulting in a clonal population with a high rate of invasiveness. Additionally, a sudden emergence of unusually high genetic diversity in monitored bacterial populations might indicate their intentional application for harmful purposes or serve as an early sign of traits linked to public health and environmental hygiene concerns.

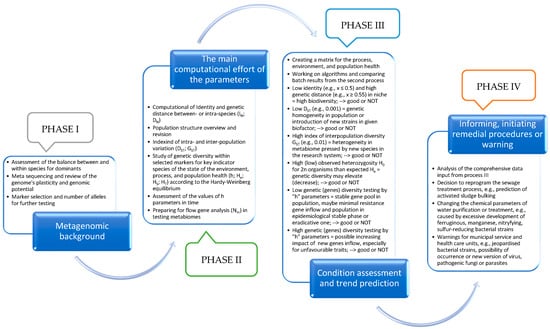

Understanding the genetic variability of bacterial populations in human communities, as well as the diversity of genes and proteins, is crucial. This is particularly relevant given the potential accidental or intentional use of genetically modified bacteria as unconventional weapons during hybrid warfare and crises. Identifying specific genetic markers and coefficients can serve as early warning signals for any unusual endemic or epidemic activity among bacteria within urban populations. This proactive approach can help prevent, protect, and preserve public health effectively. Monitoring the presence of bacteria in shed feces within sewer systems or outflows from wastewater treatment plants, while analyzing the genetic structure—whether panmictic or invasive—of bacterial populations and their level of clonality, is essential. The greater the genetic diversity of potential pathogens within the human population, the higher the actual threat of an epidemic (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Simplified phased algorithm of operation taking into account the parameters of variability and genetic diversity of sanitary-hygienic environmental and epidemiological indicators for the needs of WBE and water and wastewater treatment technologies (preliminary idea).

According to Mata and Douardo [123], a matrix of values and numerical ranges can be created to assess the bacterial structure of populations and genetic diversity parameters across several categories. These include susceptible (S), exposed (E), asymptomatic infectious (A), symptomatic (I), pre-hospitalized in the ICU (PH), predeceased with a fatal prognosis (PD), admitted to the ICU with potential recovery (HR) or death (HD), recovered (R), and deceased (D) populations. Additionally, space can be included in the matrices for potential microbiological markers related to the intentional use of microorganisms that could threaten public health. During environmental systematic surveillance, values of “h” parameters will provide information or warnings about impending events and risks before they escalate into endemic or higher-level epidemic situations. The critical question revolves around the selection of genetic markers. Therefore, whole genome sequencing, along with randomly amplified regions and individual traits (such as enzymes and resistance genes), should be utilized simultaneously.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization and methodology, K.K.; formal analysis, K.K.; resources, K.K.; writing—original draft preparation, K.K.; writing—review and editing, K.K., O.O.-W. and M.K.; visualization, K.K., O.O.-W. and M.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

APC was funded by Project implemented from the funds of the National Health Program for 2021–2025” no 357/2021/DA Ministry of National Defense, Poland.

Data Availability Statement

The original data presented in the study are openly available in PubMed at https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov, accessed on 12 December 2025.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ESKAPE | An acronym comprising the scientific names of six highly virulent and antibiotic resistant bacterial pathogens |

| WBE | Wastewater based epidemiology |

| OTU | Operational taxonomic unit |

| NGS | Next-generation sequencing |

References

- Trevors, J. Bacterial population genetics. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 1997, 14, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, S.L.; Stevens, S.L.R.; Crary, B.; Martinez-Garcia, M.; Stepanauskas, R.; Woyke, T.; Tringe, S.G.; Andersson, S.G.E.; Bertilsson, S.; Malmstrom, R.R.; et al. Contrasting patterns of genome-level diversity across distinct co-occurring bacterial populations. ISME J. 2018, 12, 742–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korzekwa, K. Application of DNA Markers for Assessment of Mycobacterium tuberculosis Strains. Ph.D. Thesis, Warmia and Mazury University, Olsztyn, Poland, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Zmysłowska, I.; Korzekwa, K. Microorganisms in Biotechnology, 1st ed.; Warmia and Mazury University Press: Olsztyn, Poland, 2011; pp. 13–315. ISBN 978-83-7299-735-7. [Google Scholar]

- Pavoine, S.; Bailly, X. New analysis for consistency among markers in the study of genetic diversity: Development and application to the description of bacterial diversity. BMC Evol. Biol. 2007, 7, 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, Y.; Nie, J.; Kuang, L.; Zhang, J.; Li, H. DNA sequencing, genomes and genetic markers of microbes on fruits and vegetables. Microb. Biotechnol. 2021, 14, 323–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satam, H.; Joshi, K.; Mangrolia, U.; Waghoo, S.; Zaidi, G.; Rawool, S.; Thakare, R.P.; Banday, S.; Mishra, A.K.; Das, G.; et al. Next-Generation Sequencing Technology: Current Trends and Advancements. Biology 2023, 12, 997, Erratum in: Biology 2024, 13, 286. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology13050286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuznetsov, V.; Lee, H.K.; Maurer-Stroh, S.; Molnár, M.J.; Pongor, S.; Eisenhaber, B.; Eisenhaber, F. How bioinformatics influences health informatics: Usage of biomolecular sequences, expression profiles and automated microscopic image analyses for clinical needs and public health. Health Inf. Sci. Syst. 2013, 1, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carriço, J.A.; Rossi, M.; Moran-Gilad, J.; Van Domselaar, G.; Ramirez, M. A primer on microbial bioinformatics for nonbioinformaticians. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2018, 24, 342–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Therrien, J.-D.; Thomson, M.; Sion, E.S.; Lee, I.; Maere, T.; Nicolaï, N.; Manuel, D.G.; Vanrolleghem, P.A. A comprehensive, open-source data model for wastewater-based epidemiology. Water Sci Technol. 2024, 89, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riley, L.W. Laboratory methods in molecular epidemiology: Bacterial infections. Microbiol. Spectr. 2018, 6, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Global Health Observatory. World Health Organization. Available online: https://www.who.int/data/gho (accessed on 11 December 2025).

- Tümmler, B. Molecular epidemiology in current times. Environ. Microbiol. 2020, 22, 4909–4918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingelbeen, B.; van Kleef, E.; Mbala, P.; Kostas, D.; Ivalda, M.; Hens, N.; Cleynen, E.; van der Sande, M.A.B. Embedding risk monitoring in infectious disease surveillance for timely and effective outbreak prevention and control. BMJ Glob. Health 2025, 10, e016870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Ning, D.; Zhang, B.; Li, Y.; Zhang, P.; Shan, X.; Zhang, Q.; Brown, M.R.; Li, Z.; van Nostrand, J.D.; et al. Global diversity and biogeography of bacterial communities in wastewater treatment plants. Nat. Microbiol. 2019, 4, 1183–1195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Available online: https://ndc.services.cdc.gov/wp-content/uploads/Antibiotic-Resistance-Threats-in-the-United-States-2019.pdf (accessed on 11 May 2025).

- de Oliveira, D.M.P.; Forde, B.M.; Kidd, T.J.; Harris, P.N.A.; Schembri, M.A.; Beatson, S.A.; Paterson, D.L.; Walker, M.J. Antimicrobial resistance in ESKAPE pathogens. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2020, 33, e00181-19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lenart-Boroń, A.; Wolanin, A.; Jelonkiewicz, E.; Żelazny, M. The effect of anthropogenic pressure shown by microbiological and chemical water quality indicators on the main rivers of Podhale, southern Poland. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2017, 24, 12938–12948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiersztyn, B.; Chróst, R.; Kaliński, T.; Siuda, W.; Bukowska, A.; Kowalczyk, G.; Grabowska, K. Structural and functional microbial diversity along a eutrophication gradient of interconnected lakes undergoing anthropopressure. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 11144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, D.; Kong, X.; Cui, B.; Jin, S.; Xie, Y.; Wang, X.; Deng, Y. Bacterial communities and potential waterborne pathogens within the typical urban surface waters. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 13368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Das, S.; Bombaywala, S.; Srivatsava, S.; Kapley, A.; Dhodopkar, R.; Dafale, N.A. Genome plasticity as a paradigm of antibiotic resistance spread in ESKAPE pathogens. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2022, 29, 40507–40519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, S.; Lin, W.-Y.; Wang, Y.-C.; Fu, Y.; Lakshmi, A.; Wang, H.-Y. Antibiotic resistance diagnosis in ESKAPE pathogens—A review on proteomic perspective. Diagnostics 2023, 13, 1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinert, M.; Hentschel, U.; Hacker, J. Legionella pneumophila: An aquatic microbe goes astray. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2002, 26, 149–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Neill, E.; Humphreys, H. Surveillance of hospital water and primary prevention of nosocomial legionellosis: What is the evidence? J. Hosp. Infect. 2005, 59, 273–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spratt, G.B.; Maiden, M.C. Bacterial population genetics, evolution and epidemiology. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B. Biol. Sci. 1999, 354, 701–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dykhuizen, D.; Kalia, A. The population structure of pathogenic bacteria. In Evolution in Health and Disease, 2nd ed.; Stearns, S.C., Koella, J.C., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Cabridge, UK, 2007; pp. 185–198. [Google Scholar]

- Rocha, E.P.C. Neutral Theory, Microbial Practice: Challenges in Bacterial Population Genetics. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2018, 35, 1338–1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korzekwa, K.; Polok, K.; Zieliński, R. Application of DNA markers to estimate genetic diversity of Mycobacterium tuberculosis strains. Pol. J. Microbiol. 2005, 55, 19–24. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Shitut, S.; van Dijk, T.; Claessen, D.; Rozen, D. Bacterial heterozygosity promotes survival under multidrug selection. Curr. Biol. 2025, 35, 1437–1445.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nei, M. Analysis of gene diversity in subdivided populations. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. USA 1973, 70, 3321–3323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagylaki, T. The expected number of heterozygous sites in a subdivided population. Genetics 1998, 149, 1599–1604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewan, I.; Uecker, H. Evolutionary rescue of bacterial populations by heterozygosity on multicopy plasmids. J. Math. Biol. 2025, 90, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, T.L.; Jasper, M.-E.; Weeks, A.R.; Hoffmann, A.A. Unbiased population heterozygosity estimates from genome-wide sequence data. Methods Ecol. Evol. 2021, 12, 1888–1898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nei, M. Molecular Evolutionary Genetics; Columbia University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1987; p. 512. ISBN 978-02-3106-321-0. [Google Scholar]

- Brauer, F. Mathematical epidemiology: Past, present, and future. Infect. Dis. Model. 2017, 2, 113–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiu, X.; Challagundla, L.; Senghore, M.; Hanage, W.P.; Robinson, D.A. Population Structure of Pathogenic Bacteria. In Genetics and Evolution of Infectious Diseases, 3rd ed.; Tibayrenc, M., Ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2024; pp. 57–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treskova, M.; Semenza, J.C.; Arnés-Sanz, C.; Al-Ahdal, T.; Markotter, W.; Sikkema, R.S.; Rocklöv, J. Climate change and pandemics: A call for action. Lancet Planet. Health 2025, 9, 101302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larsen, D.A.; Green, H.; Collins, M.B.; Kmush, B.L. Wastewater monitoring, surveillance and epidemiology: A review of terminology for a common understanding. FEMS Microbes 2021, 2, xtab011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Waarde, J.; Krooneman, J.; Geurkink, B.; van der Werf, A.; Eikelboom, D.; Beimfohr, C.; Snaidr, J.; Levantesi, C.; Tandoi, V. Molecular monitoring of bulking sludge in industrial wastewater treatment plants. Water Sci. Technol. 2002, 46, 551–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kacprzak, M.; Neczaj, E.; Okoniewska, E. The comparative mycological analysis of wastewater and sewage sludges from selected wastewater treatment plants. Desalination 2005, 185, 363–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corpuz, M.V.A.; Buonerba, A.; Vigliotta, G.; Zarra, T.; Ballesteros, F., Jr.; Campiglia, P.; Belgiorno, V.; Korshin, G.; Naddeo, V. Viruses in wastewater: Occurrence, abundance and detection methods. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 745, 140910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carles, L.; Wullschleger, S.; Joss, A.; Eggen, R.I.L.; Schirmer, K.; Schuwirth, N.; Stamm, C.; Tlili, A. Wastewater microorganisms impact microbial diversity and important ecological functions of stream periphyton. Water Res. 2022, 225, 119119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaur, B.; Choudhary, R.; Sharma, G.; Brar, L.K. Sustainable and effective microorganisms method for wastewater treatment. Desalin. Water Treat. 2024, 319, 100419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gencel, M.; Cofino, G.M.; Hui, C.; Sahaf, Z.; Gauthier, L.; Matta, C.; Gagné-Leroux, D.; Tsang, D.K.L.; Philpott, D.P.; Ramathan, S.; et al. Quantifying the intra- and inter-species community interactions in microbiomes by dynamic covariance mapping. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 6314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanaka, K.K.; Sukhija, N.; Goli, R.C.; Singh, S.; Ganguly, I.; Dixit, S.P.; Dash, A.; Malik, A.A. On the concepts and measures of diversity in the genomics era. Curr. Plant Biol. 2023, 33, 100278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansouri, Z.; Benmalek, Y.; Korichi-Ouar, M. Antibiotic and cadmium resistance patterns in non-fermentative Gram-negative bacilli isolated from hospital and urban wastewater. Water Air Soil Pollut. 234, 389. [CrossRef]

- Boon, E.; Meehan, C.J.; Whidden, C.; Wong, D.H.; Langille, M.G.; Beiko, R.G. Interactions in the microbiome: Communities of organisms and communities of genes. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2014, 38, 90–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boerlin, P.; Peter, O.; Bretz, A.G.; Postic, D.; Baranton, G.; Piffaretti, J.C. Population genetic analysis of Borrelia burgdorferi isolates by multilocus enzyme electrophoresis. Infect. Immun. 1992, 60, 1677–1683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, V.; Rocha, M.; Valera, A.; Eguiarte, L.E. Genetic structure of natural population of Escherichia coli in wild hosts on different continents. Appl. Environ. Microb. 1999, 65, 3373–3385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suerbaum, S.; Lohrengel, M.; Sonnevend, A.; Ruberg, F.; Kist, M. Allelic diversity and recombination in Campylobacter jejuni. J. Bacteriol. 2001, 183, 2553–2559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hampson, D.J.; Blackall, P.J.; Woodward, J.M.; Lymbery, A.J. Genetic analysis of Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae and comparison with Haemophilus spp. taxon “minor group” and taxon C. Zentralbl. Bakteriol. 1993, 279, 83–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fusté, M.C.; Pineda, M.A.; Palomar, J.; Vińas, M.; Lorén, J.G. Clonality of multidrug-resistant nontypeable strains of Haemophilus influenzae. J. Clin. Microbiol. 1996, 34, 2760–2765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Alphen, L.; Caugant, D.A.; Duim, B.; O’Rourke, M.; Bowler, L.D. Differences in genetic diversity of nonecapsulated Haemophilus influenzae from various diseases. Microbiology 1997, 143, 1423–1431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin, C.; Boyd, E.F.; Quentin, R.; Massicot, P.; Selander, R.K. Enzyme polymorphism in Pseudomonas aeruginosa strain recovered from cystic fibrosis patients in France. Microbiology 1999, 145, 2587–2594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rius, N.; Fusté, M.C.; Guasp, C.; Lalucat, J.; Lorén, J. Clonal population structure of Pseudomonas stutzeri, a species with exeptional genetic diversity. J. Bacteriol. 2001, 183, 736–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farfán, M.; Miñana, D.; Fusté, M.C.; Lorén, J.G. Genetic relationships between clinical and environmental Vibrio cholerae isolates based on multilocus enzyme electrophoresis. Microbiology 2000, 146, 2613–2626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farfán, M.; Miñana-Galbis, D.; Fusté, M.C.; Lorén, J.G. Allelic diversity and population structure in Vibrio cholerae O139 Bengal based on nucleotide sequence analysis. J. Bacteriol. 2002, 184, 1304–1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Starliper, C.E.; Schill, W.B.; Shotts, E.B.; Waltman, W.D. Isozyme analysis of Edwardsiella ictaluri. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 1988, 37, 81–87. [Google Scholar]

- Starliper, C.E.; Phelps, S.R.; Schill, W.B. Genetic relatedness of Vibrio anguillarum and Vibrio ordalii. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 1989, 40, 25–30. [Google Scholar]

- Caballero, M.J.; Martinez, R.E. Limited genetic diversity in the endophytic sugarcane bacterium Acetobacter diazotrophicus. Appl. Environ. Microb. 1994, 60, 1532–1537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barrera, L.L.; Trujillo, M.E.; Goodfellow, M.; Garcia, F.J.; Hernandez, L.I.; Davila, G.; Berkum, P.; Martinez, R.E. Biodiversity of Bradyrhizobia nodulating Lupinus spp. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 1997, 47, 1086–1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, V.; Eguiarte, L.; Avila, G.; Cappello, R.; Gallardo, C.; Montoya, J.; Pinero, D. Genetic structure of Rhizobium etli biovar phaseoli associated with wild and cultivated bean plants (Phaseolus vulgaris and Phaseolus coccineus) in morelos, Mexico. Appl. Environ. Microb. 1994, 60, 1260–1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinero, D.; Martinez, E.; Selander, R.K. Genetic diversity and relationships among isolates of Rhizobium leguminosarum biovar phaseoli. Appl. Environ. Microb. 1988, 54, 2825–2832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drouin, P.; Prevost, D.; Antoun, H. Classification of bacteria nodulating Lathyrus japonicus and Lathyrus pratensis in northern Quebec as strains of Rhizobium leguminosarum biovar viciae. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 1996, 46, 1016–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagen, M.J.; Hamrick, L.J. A hierarchical analysi of population genetic structure in Rhizobium leguminosarum bv. Trifolii. Mol. Ecol. 1996, 5, 177–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wise, M.G.; McArthur, J.V.; Wheat, C.; Shimkets, L.J. Temporal variation in genetic diversity and structure of a lotic population of Burkholderia (Pseudomonas) cepacia. Appl. Environ. Microb. 1996, 62, 1558–1562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Go, M.F.; Kapur, V.; Graham, D.Y.; Musser, J.M. Population genetic analysis of Helicobacter pylori by multilocus enzyme electrophoresis: Extensive allelic diversity and recombinational population structure. J. Bacteriol. 1996, 178, 3934–3938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuente, L.; Vasquez, J.A. Multilocus enzyme electrophoresis of African type penicillinase-producing Neisseria gonorrhoeae (PPNG) strains isolated in Spain. Sex. Transm. Dis. 1991, 18, 150–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuente, L.; Vasquez, J.A. Analysis of genetic variability of penicillinase non-producing Neisseria gonorrhoeae strains with differen levels of resistance to penicillin. J. Med. Microbiol. 1992, 37, 96–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caugant, D.A.; Mocca, L.F.; Frasch, C.E.; Froholm, L.O.; Zollinger, W.D.; Selander, R.K. Genetic structure of Neisseria meningitidis populations in relation to serogroup, serotype, and outer membrane protein pattern. J. Bacteriol. 1987, 169, 2781–2792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hampson, D.J.; Trot, D.J.; Clarke, I.L.; Mwaniki, C.G.; Robertson, I.D. Population structure of Australian isolates of Streptococcus sius. J. Clin. Microbiol. 1993, 31, 2895–2900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Musser, J.M.; Beltran, P.; Kline, M.W.; Selander, R.K. Genotypic heterogeneity of strains of Citrobacter diversus expressing a 32-kilodalton outer membrane protein asociated with neonatal meningitis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 1990, 28, 1760–1765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, D.G.; Wilson, R.A.; Gabriel, A.S.; Saco, M.; Whittam, T.S. Genetic relationships among strains of avian Escherichia coli associated with swollen-head syndrome. Infect. Immun. 1990, 58, 3613–3620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whittam, T.S.; Ochman, H.; Selander, R.K. Geographic components of linkage disequilibrium in natural populations of Escherichia coli. Mol. Biol. Evol. 1983, 1, 67–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodward, J.M.; Connaughton, I.D.; Fahy, V.A.; Lymbery, A.J.; Hampson, D.J. Clonal analysis of Escherichia coli of serogroups O9, O20, and O101 isolated from Australian pigs with neonatal diarrhea. J. Clin. Microbiol. 1993, 31, 1185–1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blackall, P.J.; Trott, D.J.; Rapp-Gabrielson, V.; Hampson, D.J. Analysis of Haemophilus parasuis by multilocus enzyme electrophoresis. Vet. Microbiol. 1997, 56, 125–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, D.M.; Lee, J. The genetic structure of enteric bacteria from Australian mammals. Microbiology 1999, 145, 2673–2682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selander, R.K.; McKinney, R.M.; Whittam, T.S.; Bibb, W.F.; Brenner, D.J.; Nolte, F.S.; Pattison, P.E. Genetic structure of populations of Legionella pneumophila. J. Bacteriol. 1985, 163, 1021–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blackall, P.J.; Fegan, N.; Chew, G.I.T.; Hampson, D.J. Population structure and diversity of avian isolates of Pasteurella multocida from Australia. Microbiology 1998, 144, 279–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davies, R.L.; Arkinsaw, S.; Selander, R.K. Genetic relationship among Pasteurella trehalosi isolates based on multilocus enzyme electrophoresis. Microbiology 1997, 143, 2841–2849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denny, T.P.; Gilmour, M.N.; Selandr, R.K. Genetic diversity and relationship of two pathovars of Pseudomonas syringae. J. Genet. Microbiol. 1988, 134, 1949–1960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reeves, M.W.; Evins, G.M.; Heiba, A.A.; Plikaytis, B.D.; Farmer, J.J. Clonal nature of Salmonella typhi and its genetic relatedness to other salmonellae as shown by multilocus enzyme electrophoresis, and proposal of Salmonella bongori comb. J. Clin. Microbiol. 1989, 27, 313–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beltrán, P.; Delgado, G.; Navarro, A.; Trujillo, F.; Selander, R.K.; Cravioto, A. Genetic diversity and population structure of Vibrio cholerae. J. Clin. Microbiol. 1999, 37, 581–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aeschbacher, M.; Piffaretti, J.C. Population genetics of human and animal enteric Campylobacter strains. Infect. Immun. 1989, 57, 1432–1437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tortora, G.J.; Funke, B.R.; Case, C.L. Microbiology: An Introduction, 10th ed.; Pearson Benjamin Cummings: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2010; pp. 210–474. ISBN 13: 978-0-321-58202-7. [Google Scholar]

- Lomholt, H. Evidence of recombination and an antigenically diverse immunoglobulin A1 protease among strains of Streptococcus pneumoniae. Infect. Immun. 1995, 63, 4238–4243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boyd, E.F.; Hiney, M.P.; Peden, J.F.; Smith, P.R.; Caugant, D.A. Assessment of genetic diversity among Aeromonas salmonicida isolates by multilocus enzyme electrophoresis. J. Fish. Dis. 1994, 17, 97–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altwegg, M.; Reeves, M.W.; Altwegg-Bissig, R.; Brenner, D.J. Multilocus enzyme analysis of the genus Aeromonas and its use for species identification. Zentralbl. Bakteriol. 1991, 275, 28–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pons, J.L.; Combe, M.L.; Leluan, G. Multilocus enzyme typing of human and animal strains of Clostridium perfringens. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 1994, 121, 25–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lukin, S.A.; Malinina, T.B.; Prozorov, A.A. Allozyme variability in strains of soil bacilli related to Bacillus subtilis. Genetika 1994, 30, 181–184. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bibb, W.F.; Schwartz, B.; Gellin, B.G.; Plikaytis, B.D.; Weaver, R.E. Analysis of Listeria monocytogenes by multilocus enzyme electrophoresis and application of the method to epidemiologic investigation. Int. J. Food. Microbiol. 1989, 8, 233–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piffaretti, J.C.; Kressebuch, H.; Aeschbacher, M.; Bille, H.; Bannerman, E.; Musser, J.M.; Selander, R.K.; Rocourt, J. Genetic characterization of clones of bacterium Listeria monocytogenes causing epidemic disease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1989, 86, 3818–3822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilmour, M.N.; Whittam, T.S.; Kilian, M.; Selander, R.K. Genetic relationships among the oral streptococci. J. Bacteriol. 1987, 169, 5247–5257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Starliper, C.E. Genetic diversity of North America isolates of Rhenibacterium salmoninarum. Dis. Aquat. Organ. 1996, 27, 207–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trott, D.J.; Masters, A.M.; Carson, J.M.; Allis, T.M.; Hampson, D.J. Genetic analysis of Dermatophilus spp. using multilocus enzyme electrophoresis. Zentralbl. Bakteriol. 1995, 282, 24–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feizabadi, M.M.; Robertson, I.D.; Cousins, D.V.; Dawson, D.J.; Chew, W.; Gilbert, G.L.; Hampson, D.J. Genetic characterization of Mycobacterium avium isolates recovered from humans and animals in Australia. Epidemiol. Infect. 1996, 116, 41–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wasem, C.F.; McCarthy, C.M.; Murray, L.W. Multilocus enzyme electrophoresis analysis of the Mycobacterium avium complex and other mycobacteria. J. Clin. Microbiol. 1991, 29, 264–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feizabadi, M.M.; Robertson, I.D.; Cousins, D.V.; Dawson, D.J.; Hampson, D.J. Use of multilocus enzyme electrophoresis to examine genetic relationships amongst isolates of Mycobacterium intracellulare and related species. Microbiology 1997, 143, 1461–1469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feizabadi, M.M.; Robertson, I.D.; Cousins, D.V.; Hampson, D.J. Genomic analysis of Mycobacterium bovis and other members of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex by isoenzyme analysis and Pulsed-Field Gel Electrophoresis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 1996, 34, 1136–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balmelli, T.; Piffaretti, J.C. Association between different clinical manifestation of Lyme disease and different species of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato. Res. Microbiol. 1995, 146, 329–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balmelli, T.; Piffaretti, J.C. Analysis of the genetic polymorphism of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato by multilocus enzyme electrophoresis. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 1996, 46, 167–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahle, U.R.; Olsen, I.; Tronstad, L.; Caugant, D.A. Population genetic analysis of oral treponemes by multilocus enzyme electrophoresis. Oral Microbiol. Immun. 1995, 10, 265–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trott, D.J.; Oxberry, S.L.; Hampson, D.J. Evidence for Serpulina hyodysenteriae being recombinant, with an epidemic population structure. Microbiology 1997, 43, 3357–3365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trott, D.J.; Mikosza, A.S.J.; Combs, B.G.; Oxberry, S.L.; Hampson, D.J. Population genetic analysis of Serpulina hyodysenteriae and its molecular epidemiology in villages in the Eastern Highlands of Papua New Guinea. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 1998, 48, 659–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.I.; Hampson, D.J. Genetic Characterisation of intestinal spirochaetes and their association with disease. J. Med. Microbiol. 1994, 40, 365–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trott, D.J.; Atyeo, R.F.; Lee, J.I.; Swayne, D.A.; Stoutenburg, J.W.; Hampson, D.J. Genetic relatedness amongst intestinal spirochaetes isolated from rats and birds. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 1996, 23, 431–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S.-R.; Zschausch, H.-C.; Meyer, H.-G.; Schneider, T.; Loos, M.; Bhakdi, S.; Maeurer, M.J. Helicobacter pylori: Clonal population structure and restricted transmission within families revealed by molecular typing. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2000, 38, 3646–3651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutacker, M.; Valsangiacomo, C.; Piffaretti, J.-C. Identification of two genetic groups in Bacteroides fragilis by multilocus enzyme electrophoresis: Distribution of antibiotic resistance (cfiA, cepA) and enterotoxin (bft) encoding genes. Microbiology 2000, 146, 1241–1254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, D.M. The genetic structure of Escherichia coli population in feral house mice. Microbiology 1997, 143, 2039–2045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selander, R.S.; Levin, B.R. Genetic diversity and structure in Escherichia coli populations. Science 1980, 210, 545–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Z.; Morrison, N.; Watt, B.; Doig, C.; Forbes, K.J. IS6110 transposition and evolutionary scenario of the direct repeat locus in a group of closely related Mycobacterium tuberculosis strains. J. Bacteriol. 1998, 180, 2102–2109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.H.; Ijaz, K.; Bates, J.H.; Eisenach, K.D.; Cave, M.D. Spoligotyping and polymorphic GC-rich repetitive sequence fingerprinting of Mycobacterium tuberculosis strains having few copies of IS6110. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2000, 38, 3572–3576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Embden, J.D.A.; Gorkom, T.; Kremer, K.; Jansen, R.; Zeijst, B.A.M.; Schouls, L.M. Genetic variation and evolutionary origin of the direct repeat locus of Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex bacteria. J. Bacteriol. 2000, 182, 2393–2401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kato-Maeda, M.; Bifani, P.J.; Kreiswirth, B.N.; Small, P.M. The nature and consequence of genetic variability within Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J. Clin. Investig. 2001, 107, 533–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sreevatsan, S.; Pan, X.; Stockauer, K.E.; Connel, N.D.; Kreiswirth, B.N.; Whittam, T.S.; Musser, J.M. Restricted structural gene polymorphism in the Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex indicates evolutionarily recent global dissemination. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1997, 94, 9869–9874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nierman, W.C.; Feldblyum, T.V.; Laub, M.T.; Paulsen, I.T.; Nelson, K.E.; Eisen, J.A.; Heidelberg, J.F.; Alley, M.R.; Ohta, N.; Maddock, J.R.; et al. Complete genome sequence of Caulobacter crescentus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2001, 98, 4136–4141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parkhill, J.; Wren, B.W.; Mungall, K.; Ketley, J.M.; Churcher, C.; Basham, D.; Chillingworth, T.; Davies, R.M.; Feltwell, T.; Holroyd, S.; et al. The genome sequence of the food-borne pathogen Campylobacter jejuni reveals hypervariable sequences. Nature 2000, 403, 665–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayashi, T.; Makino, K.; Ohnishi, M.; Kurokawa, K.; Ishii, K.; Yokoyama, K.; Han, C.-G.; Ohtsubo, E.; Nakayama, K.; Murata, T.; et al. Complete genome sequence of enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli O157:H7 and genomic comparison with a laboratory strain K-12. DNA Res. 2001, 28, 11–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perna, N.T.; Plunkett, G.; Burland, V.; Mau, B.; Glasner, J.D.; Rose, D.J.; Mayhew, G.F.; Evans, P.S.; Gregor, J.; Kirkpatrick, H.A.; et al. Genome sequence of enterohaemorrhagic Escherichia coli O157:H7. Nature 2001, 409, 529–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nölling, J.; Breton, G.; Omelchenko, M.V.; Makarova, K.S.; Zeng, Q.; Gibson, R.; Lee, H.M.; Dubois, J.; Qiu, D.; Hitti, J.; et al. Genome sequence and comparative analysis of the solvent-producing bacterium Clostridium acetobutylicum. J. Bacteriol. 2001, 183, 4823–4837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kman, N.E.; Bachmann, D.J. Biosurveillance: A Review and Update. Adv. Prev. Med. 2012, 2012, 301408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balfourier, F.; Charmet, G.; Ravel, C. Genetic differentiation within and between natural populations of perennial and annual ryegrass (Lolium perenne and L. rigidum). Heredity 1998, 81, 100–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mata, A.S.; Dourado, S.M.P. Mathematical modeling applied to epidemics: An overview. Sao Paulo J. Math. Sci. 2021, 15, 1025–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.