Abstract

The small freshwater lakes of Spitsbergen remain poorly studied compared to surrounding marine ecosystems despite their sensitivity to rapid environmental changes. During the short ablation season, these shallow lakes exhibit physicochemical variability influenced by the harsh Arctic climate, local geology, and hydrology. This study analyzed six lakes located on marine terraces, moraine areas, and outwash plains in the Bellsund region to assess how physicochemical variability in their waters affects phytoplankton development. The lakes exhibited local and temporal variations in temperature, conductivity, ion composition, and nutrient levels, with generally low nutrient availability limiting biological productivity. Phytoplankton communities were quantitatively and qualitatively poor, dominated by green algae, either flagellates or mixed communities, including cyanobacteria. Green algae clearly dominated in lakes closest to the fjord shoreline, while dinoflagellates and cryptophytes dominated in inland lakes. Phytoplankton abundance and biomass were extremely low in one of the lakes situated on the raised marine terraces within the tundra vegetation zone (3 × 103 ind L−1 and 0.004 mg L−1, respectively). In contrast, the much larger lake situated within the tundra zone nearer the fjord shoreline had values that were comparable to fertile lakes in the temperate zone (~30 thousand × 103 ind L−1 and ~28 mg L−1, respectively). It should be noted that Monoraphidium contortum and Rhodomonas minuta dominated some of the lakes almost entirely. Phytoplankton abundance was related to physicochemical conditions: green algae increased with increasing ion concentrations (Cl−, Na+, K+, SO42−), Pmin, Fe, and Mn; flagellates preferred colder waters with higher Nmin and low TOC; cyanobacteria occurred in waters with lower COND, TOC, Ca2+, Si, Cu, and Zn. Phytoplankton biomass increased in July with increasing water temperature. Bird activity likely facilitated phytoplankton dispersal, increasing taxonomic diversity in frequently visited lakes.

1. Introduction

The Arctic is currently undergoing a number of changes, the majority of which are human-caused and have impact on the region’s biogeosystems. At present, Arctic ecosystems are facing significant strain due to climate change, primarily driven by global warming, which is manifesting decisively and rapidly. It is known that Arctic air temperatures have been warming at a rate more than double the global average over the past three to four decades [1]. This phenomenon is known as ‘Arctic amplification’ [2]. A particularly severe temperature rise has been reported in Svalbard, the fastest warming region in Europe [3]. Increased air temperatures during summer accelerate glacial melt, leading to a greater volume and faster flow of freshwater runoff from glaciers. This causes a decrease in salinity and an increase in saltwater turbidity, affecting changes in phytoplankton community structure [4,5,6]. These alterations are not limited to marine ecosystems as they are most likely even more apparent in the region’s freshwater bodies. Because of their ephemeral nature (caused by geomorphological and climatic conditions), they are not very stable ecosystems, with significant diurnal and seasonal changes in their physicochemical parameters [7,8]. Such environmental conditions have impact on aquatic organisms, particularly phytoplankton communities. The second type of anthropogenic change is caused by the mining sector and infrastructure development. These activities are placing significant stress on Arctic ecosystems, particularly aquatic ecosystems, disrupting the structure and function of the food web. This has a negative impact on the already low biodiversity of these ecosystems, making the trophic networks much more vulnerable, as they are underdeveloped and hence particularly sensitive to any disturbances [9].

All of the above factors influence the physicochemical properties of water and, consequently, aquatic organisms, especially phytoplankton communities, which, as the first link in the food web, must adapt to growth and development in a constantly changing environment. Despite this, little is known about the freshwater phytoplankton found in water bodies in this region. The current understanding of photoautotrophic prokaryotic and eukaryotic organisms is primarily limited to communities that form on glaciers, in glacial streams [10,11,12], or in soil habitats [13]. The second and by far the most common set of studies concerns phytoplankton in the marine waters of Spitsbergen’s fjords [4,5,6,14,15,16]. In contrast, the studies on freshwater phytoplankton are limited and fragmented. They focus on specific algal species from selected systematic groups or ecological formations, such as cyanobacteria [17], diatoms [10,18,19], chlorophyte [20,21,22], or benthic algae in sub-Arctic ponds [23]. The only more thorough studies demonstrating the abundance and community structure of freshwater cyanobacteria and algae near Ny-Ålesund have been conducted by Willen [24], who identified over 100 taxa, primarily diatoms and green algae, as well as by Kim et al. [25,26], who reported only six taxa, focusing on shallow puddles and ice- and snow-fed streamlets. Additionally, a few studies have examined the physiological and ultrastructure changes in Arctic algae exposed to stressors, such as UV-A and UV-B rays, freezing, or desiccation tolerance in order to understand how these organisms adapt to the harsh conditions prevailing in the Arctic Circle region [27]. There are few scientific studies that demonstrate the quantitative and qualitative composition of phytoplankton in freshwater ecosystems, such as small lakes and ponds, rivers, and streams, in relation to the physicochemical properties of their waters.

Cyanobacteria and algae occur in all environments on Earth. The Arctic experiences a range of severe environmental stresses, including freezing and desiccation of terrestrial ecosystems, freezing of aquatic habitats, and exposure to high levels of UV radiation during polar days. Despite these interesting conditions characterized by a wide spectrum of extreme physical, chemical, and biological phenomena, research on the diversity and abundance of freshwater phytoplankton in the Arctic is highly incomplete. Therefore, the aims of our study were to: (i) determine the specific physicochemical characteristics of selected lakes in Bellsund Bay; (ii) determine the quantitative and qualitative structure of the summer phytoplankton community in the Bellsund area, on the west coast of Spitsbergen in the Svalbard archipelago; and (iii) explore correlations between environmental conditions and the abundance and structure of the phytoplankton community. The study of phytoplankton is important because it is the most reliable bioindicator of changes in hydrographic and physicochemical conditions. Studies of lakes near the coastal zone make a significant contribution to understanding biodiversity in areas exposed to such high environmental stresses.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

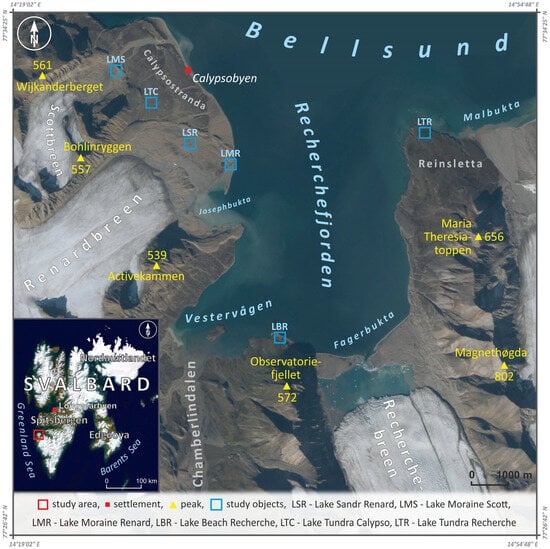

The study was carried out in an area in the north-west of Wedel Jarlsberg Land, which is located in the south-west area of Spitsbergen, the largest island in the Svalbard archipelago (Figure 1). The area is bounded to the north by the waters of Bellsund Fjord, which flows south into Recherche Fjord, dividing the land area in two parts. The mountain ranges Activecammen, Bohlinryggen and Wijkanderberget compose the western part, reaching heights of up to 800 m above sea level. They separate the valleys of the Crammer, Renard and Scott Glaciers, all of which are in severe recession. The southern and eastern parts are formed by comparable height ranges: Observatoriefjellet Recherche debouching into the fiord (Figure 1). The area is dominated by the early Precambrian and old Palaeozoic rock series of the Hecla Hoek Formation [28,29]. Quaternary formations are composed of sediments derived from diverse origins (glacial, fluvioglacial, fluvial, slope, marine and aeolian), lithology and age. They are characterized by their low thickness and dense coverings, which form on glacier forelands, lower portions of slopes, valley bottoms and within marine terraces [30,31]. Glacial sediments can be found in terminal and lateral moraines next to glaciers. Between moraines and the glacier front, ground moraines and ablation moraines can be found. These sediments vary in thickness and grain size. The fluvioglacial sediments that make up the inner and outer outwash plains, as well as the oasis and kames, significantly vary lithologically [32]. The majority of the area is covered by marine terrace sediments, which vary greatly in lithology depending on the dynamics of the sea coast. The accumulation covers of the lower terraces are mostly gravel and sand, while the raised marine terraces comprise sediments of different thickness and genesis [30,31].

Figure 1.

Location of the analyzed lakes and water sampling sites in Bellsund (West Spitsbergen, Svalbard). Background data sources: TopoSvalbard, Norwegian Polar Institute (2011) and National Aeronautics and Space Administration (2005).

The lakes in the Bellsund area are located in a variety of environments and have distinct origins [7,33]. The majority can be found on glacial forelands, as well as on former (raised) and present marine terraces. These water bodies are distinguished by a wide range of morphometric traits. Shallow water bodies covering small areas predominate. The lakes are fed in a variety of ways, with a major proportion serving as drainless lake, functioning due to the disintegration of perennial permafrost and snowmelt accumulation. These bodies of water react quickly to seasonal variations in climatic and hydrological circumstances, resulting in significant fluctuations in the water table, temperature and turbidity. Some of these water bodies are periodic, with the ablative season changing widely but lasting on average from June to October. These water bodies are often characterized by a small thickness of lake sediments and a high mineral content. Greater biodiversity is exhibited by water bodies situated within tundra vegetation zone [7].

2.2. Study Objects Characterisation of the Conditions of Functioning and Occurrence of Lakes

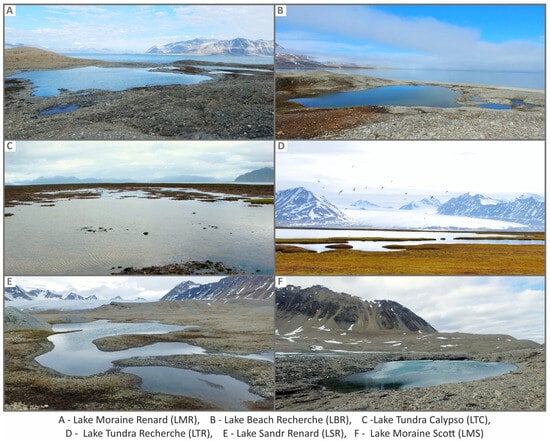

The lakes covered by detailed studies represented various natural circumstances specific to the studied area. Lake Moraine Renard (LMR) and Lake Beach Recherche (LBR) are the nearest bodies of water to the sea, located 65 m and 75 m from the shoreline, respectively. They are located in the Recherche Fjord area (Figure 1, Table 1), and their basins are situated within fuzzy marginal moraines, made of various-grained material. The water table is located approximately 1.5 m above sea level for both water bodies. The first lake is characterized by a more developed shoreline. It is situated in a lake cascade system and is fed by a small stream during the majority of the ablative season (Figure 2A). LBR, which is slightly smaller and significantly deeper, is classified as drainless (Figure 2B, Table 1). Lichens are present in the drainage basins of both lakes. With regard to the surroundings of LMR, sparse mossy vegetation is present in the depressions and the shoreline zone. Mossy vegetation is concentrated in the southern sub-stream part of the LBR drainage basin. In addition, birds and mammals are occasionally seen in the area of both bodies of water. Small fish can also be found in the lake’s waters.

Table 1.

General characteristics of the study objects; source: own study.

Figure 2.

Study objects; author: Ł. Franczak.

Lake Tundra Calypso (LTC) and Lake Tundra Recherche (LTR) are located within older, raised marine terraces, on opposite sides of Recherche Fjord (Figure 2C,D). LTC is located on the west side of the fjord, 35 m above sea level and 652 m from the fjord’s shoreline. It has a limited and very variable surface area and is relatively shallow (see Table 1). This water body disappears during severely dry periods (Figure 2C). LTR is located on the eastern side of the fjord, on a terrace 18 m above sea level and 195 m from the shoreline. It has a modest depth but a significantly wider surface area than the previous lake, with little variation throughout the season (Figure 2D, Table 1). Both water bodies are drainless fed by meltwater and groundwater from permafrost. They are surrounded by tundra vegetation. LTC, however, has less vegetation; mosses, lichens and vascular plants predominate, with species of the genus Saxifraga noted. Birds and mammals are clearly exerting stress on the water bodies under study. This is especially visible at LTR, where colonies of many bird species (especially terns) and mammals, such as reindeer and Arctic foxes can be seen throughout all seasons.

Lake Sandr Renard (LSR) is located on the forelands of the Renard Glacier at a distance of approximately 1250 m from its head and 1210 from the fjord shoreline (Figure 1 and Figure 2E). The lake basin was formed within an older layer of outwash plain, and its drainage basin is bounded by 3 m high esker embankments, which serve as a common habitat for large bird colonies (mainly gulls and terns). The lake is 14 m above sea level and has a very diversified shoreline. During the ablation season, the lake’s surface area and water table level are both minute and extremely variable (Table 1). The water body is fed through snowmelt, with intermittent inflows from tiny watercourses outside the immediate drainage basin. Mossy vegetation patches of various sizes can be seen on the lake’s bottom and in the lower regions of the drainage basin. In addition, small fish are present in the lake’s waters.

Lake Moraine Scott (LMS) is a drainless meltwater water body located in the north-eastern part of the Scott Glacier foreland, at the foot of the inner slope of the push moraine embankment (Figure 1 and Figure 2F). The lake is located around 1200 m from the edge of the Scott Glacier head and 1200 m from the shoreline of Bellsund Fjord. This water body has a minimal surface area and depth and is located 71 m above sea level (Table 1). It is distinguished by little seasonal change in water levels. The drainage basin of the lake has no vegetation, while there are rare clumps of aquatic vegetation on the bottom of the lake. Small fish can be seen here, as well as birds and mammals on rare occasions.

2.3. Field Research

The physicochemical parameters were examined, and water samples were collected from the six Western Spitsbergen water bodies during the UMCS’s XXX Polar Expedition in 2022. Water samples from 3 lakes (LTC, LMS, LMR) were taken twice at a monthly interval (June, July). In the case of these reservoirs, for the June samples, a number 1 was added to the reservoir name, e.g., LTC1, and for the July samples, a number 2 was added, e.g., LTC2. The sample collection for LSR and LBR took place only in June. In turn, with regard to LTR, samples were taken only in July. On each sampling date, one subsurface water sample (up to 30 cm) was taken from the central part of the lake using a sampler. All water bodies were measured for temperature, water pH and electrolytic conductivity (COND). The water samples were examined for hydro-chemical parameters, as well as phytoplankton quantitative and qualitative composition. Surface water sampling was conducted in accordance with EN ISO 5667-1 and EN ISO 5667-3 [34,35]. In order to determine the phytoplankton composition structure, both uncompacted and pre-compacted samples of 50 L were collected on a plankton grid (10 µm) for quantitative and qualitative analyses. The samples were fixed with Lugol’s solution (Chempur, 10%). The samples were safeguarded from damage during transport and kept in sunlight-free settings at a temperature of approximately 4 °C.

The meteorological data was obtained from an automatic measuring station located on the flat surface of a raised marine terrace within the Calypsostrand area, situated 23 m above sea level 180 m from the shoreline of Bellsund Fjord (ϕ = 77°33′30″ N, λ = 14°30′49″ E). The following parameters were measured: air temperature, relative humidity, wind direction and speed, as well as precipitation. From 20 June to 27 July 2022, measurements were taken in UTC time with a 10-min time step (144 times per day).

2.4. Laboratory and Computational Research

At the Laboratory of Hydrochemistry and Hydrometry, Department of Hydrology and Climatology, UMCS (Maria Curie-Sklodowska University), an ion chromatography instrument (Metrohm MIC-3, Herisau, Switzerland) was employed to identify the ions in the waters under study, both qualitatively and quantitatively. Anions (Cl−, NO2−, NO3−, SO42−) were determined using a Metrosep A SUPP5 250 column, whereas cations (Na+, NH4+, K+, Ca2+, Mg2+) were assessed by means of a Metrosep C2 150 column. Bicarbonate (HCO3−) content was discerned by applying a titration method with hydrochloric acid (0.05 M, AlfaChem, Toruń, Poland) in the presence of bromocresol green (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). The water samples were also analysed for total nitrogen (TN), total phosphorus (TP), their dissolved mineral forms (Nmin, Pmin), total organic carbon (TOC), turbidity, colour, total suspended solids (TSS) and basic micronutrients. Table 2 contains information about the various laboratory tests performed, as well as the methodology employed.

Phytoplankton abundance was estimated via an inverted microscope Carl Zeiss Axiovert-35 (Jena, Germany) and the Utermöhl method [36]. We considered individual alga as the unit (unicell, colony, coenobium, or 100 µm long filament). To calculate phytoplankton biomass, unit counts were converted to biovolumes using the guidelines of Hillebrand et al. [37]. For dominants, we determined the species that accounted for at least 25% of the total biomass/abundance of phytoplankton. Taxonomic observations were conducted using a Nikon Eclipse 80i microscope equipped with differential interference contrast (DIC, Nomarski contrast) using ×40 and ×60 magnification. All samples were identified to the species level, if possible. Algal taxa were identified based on published taxonomic keys.

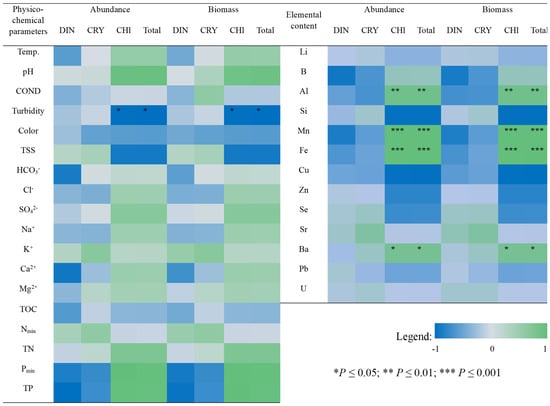

2.5. Statistical Analysis

Physicochemical parameters and quantitative and qualitative phytoplankton data were statistically analysed using Statistica and PAST (Paleontological Statistics). The study applied descriptive and exploratory methods, including cluster analysis, Principal Component Analysis (PCA), and a heatmap of Pearson correlation coefficients between physicochemical and biological variables. Significance levels were set at p ≤ 0.05; p ≤ 0.01; p ≤ 0.001. These methods were used to visually present the data and show general patterns and similarities among the lakes [38,39].

Table 2.

Range of conducted analyses of water quality in lakes of West Spitsbergen; source: own study.

Table 2.

Range of conducted analyses of water quality in lakes of West Spitsbergen; source: own study.

| Scope | Method | Apparatus | Norm | Reference Materials |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| I. Field measurements | ||||

| Temperature [°C] | Electrometric | YSI Pro 1030 | ||

| Reaction (pH) | YSI Pro 1030 | |||

| COND * [µS cm−1] | YSI Pro 1030 | YSI 3167 | ||

| II. Laboratory measurements | ||||

| Turbidity [FTU] | Spectrophotometric | Hach DR 2000 | Hach 8237 | |

| Color [mg Pt L−1] | Hach 8025 | |||

| Total suspended solids [mg L−1] | Pastel UV | |||

| Sodium [mg Na+ L−1] | Ion chromatography | Metrohm MIC-3 | PN-EN ISO 14911:2002 [40] | Environment Canada MISSIPPI-14 and ION-915 |

| Potassium [mg K+ L−1] | ||||

| Calcium [mg Ca2+ L−1] | ||||

| Magnesium [mg Mg2+ L−1] | ||||

| Ammonium nitrogen [mg NH4+ L−1] | ||||

| Chlorides [mg Cl− L−1] | PN-EN ISO 10304-1:2009 [41] | |||

| Sulphates [mg SO42− L−1] | ||||

| Nitrate nitrogen [mg NO3− L−1] | ||||

| Nitrite nitrogen [mg NO2− L−1] | ||||

| Nmin ** [mg N L−1] | Calculation | |||

| Total nitrogen [mg N L−1] | Spectrophotometric | Hach DR 900 | HACH 10071 | Nitrogen total standard solution (Supelco) |

| Total phosphorus [mg P L−1] | Spectrophotometric | Hach DR 900 | HACH 8190 | Phosphorus total standard solution (Supelco) |

| Orthophosphates [mg PO43− L−1] | HACH 8048 | |||

| Pmin *** [mg P L−1] | Calculation | |||

| Metals and metalloids [µg L−1] | Mass spectrometry | ICP-MS | EnviroMAT ES-L-2 CRM EnviroMAT ES-H-2 CRM | |

Note: * COND—electrolytic conductivity at 25 °C, ** Nmin—mineral nitrogen [mg N L−1], *** Pmin = Orthophosphates [mg P L−1].

3. Results

3.1. Weather and Hydrological Conditions at the Time of Sampling

The Bellsund area’s meteorological conditions are primarily influenced by air circulation processes that are subject to strong local transformations as a result of the interplay of the marine and terrestrial environments with widely varied orography. In the summer season of 2022, the average air temperature during the water sample period (expanded to include data for the 7 days preceding the surveys) was 6.4 °C. A maximum value of 12.0 °C was recorded on 13/07, while a minimum value of 1.2 was recorded on 20/06. The average humidity was 85.2%, with values ranging between 46% (08/07) and 100% (during the last days of June and July). Wind speeds reached values between 0.3 and 15.5 m s−1, with an average of 4.7 m s−1.

The average air temperature on the sampling days (24 and 27 June 2022 and 27 July 2022) was 4.0, 5.5 and 7.0 °C, respectively. The daily maximum values in June were 6.1 and 7.6 °C (10 a.m., and 5 p.m.) and in July 8.9 °C (1 p.m.), while the minimum values were 2.7 and 4.2 °C (24 a.m. and 5 a.m.) and 7.6 °C (11 p.m.), respectively. There was no precipitation recorded on these days, and the average humidity values were 73.0, 74.8 and 93.4%. Wind speeds varied significantly in June, ranging from 4.2–14.2 to 0.7–5.5 m s−1 (average values 9.9 and 2.5 m s−1), whereas in July, they were 0.7–6.5 m s−1 (average value 3.7 m s−1). Winds from the NE prevailed on 24/06 (56%) and 27/06 (36 and 19%), but on 27/07, their distribution was more variable and was as follows: SE—17%, W and NW—33 and 20%, while SE—18%.

3.2. Physicochemical Water Properties

Table 3 shows the physicochemical parameters of the freshwater in the West Spitsbergen lakes (LBR = no chemical analyses, sample damaged during transport). The water temperatures ranged from 7.1 °C in June, to 13.9 °C in July (LMR and LTR). The water had low turbidity (up to 2 NTU), total suspended solids (TSS) (<2.5 to 3.0 mg L−1), TOC (0.7 to 1.5 mg L−1) and colour (no measurable—15 mg Pt L−1). The waters under study had an alkaline pH ranging from 8.2 to 8.8. The COND value of dissolved minerals in the studied lakes ranged from 115 to 403 µS cm−1 and was within the low mineralised water range. The exception was the high COND (>4000) in Lake LBR resulting from overflow of sea water. In our study, higher COND values were recorded in the moraine-like lakes: LMR and LMS. When comparing the concentrations of key ions in the freshwater lakes of Spitsbergen, it was noted that chloride, sulphate and sodium concentrations were higher in the lakes nearest to the shoreline: LMR and LTR, which was consistent with the assumption made previously (no data for LBR). In terms of hydro-chemical characteristics, depending on the lake’s location, the waters under study were of the following types: HCO3−-SO42−-Ca2+-Mg2+ (LMR, LMS, LTR) or HCO3−-Ca2+-Mg2+ (LSR, LTC).

Table 3.

Selected specific physicochemical properties of waters.

The hydro-chemical studies of the waters focused on the biogenic components, i.e., nitrogen and phosphorus, which indicated the fertility of these water bodies (Table 3). The mineral and total nitrogen contents was between 0.01 and 0.06 mg N L−1 and 0.41 and 1.81 mg N L−1, respectively. In most cases, the proportion of mineral forms in total nitrogen ranged from less than 1 to about 2.5%. The exception to the above was the LMR waters sampled in July, where the value was about 14%. There were no characteristic time-dependent nitrogen content correlations in these water bodies. The mineral phosphorus content was between <0.01 and 0.03 mg P L−1, while the total phosphorus content ranged between 0.02 and 0.05 mg P L−1. In turn, the proportion of mineral phosphorus in the total phosphorus pool was much greater and more variable than that of nitrogen, extending from approximately 14 to 83%. The samples taken from the same lakes on different dates showed larger proportions of mineral phosphorus to total phosphorus (from 28.5 to 53%) in June and lower proportions in July (from 14.3 to 33%).

The studied waters had a relatively low metal and metalloid concentration (Table 4). However, considerable disparities in micronutrient content were discovered between the Svalbard freshwater lakes under study. Significantly higher contents of silicon (Si) (Si up to >930 µg L−1) and strontium (Sr) (Sr > 740 µg L−1) were noted in the following lakes: LMS and LTC (northern part of the study area). Moreover, the waters of LTE contained much more aluminium (Al), manganese (Mn) and iron (Fe) as compared to the other water bodies, (from 50% to more than 96%). In turn, boron (B) and lithium (Li) were evidenced at up to several times higher levels in LMR and LTR (located very close to the shoreline) as compared to the other lakes. In addition, our research revealed time-related instability in metal composition.

Table 4.

Content of elements in water samples taken from Spitsbergen (µg L−1).

3.3. Species Structure, Abundance and Biomass of Phytoplankton

The species structure, abundance and biomass of phytoplankton in the Arctic water bodies examined during the summer of 2022 were very varied. The taxonomic diversity, as measured by alpha diversity, was extremely low. Its value was between a few species (minimum 4 in LBR) to a dozen (maximum 16 in LMR in July). This value typically indicated approximately 10 taxa per sample. It should be noted that beta diversity (diversity between lakes) was also low. The greatest taxonomic difference was reported between LBR and LMR (sample taken in July), which had only one common taxon. Accordingly, green algae were the dominant group in both lakes (in LMR, also dinophytes), although Monoraphidium contortum dominated in LBR, while Botryococcus braunii and dinophytes of the genus Gymnodinium dominated in LMR. There was less species diversity of lakes in the June samples than in the July samples.

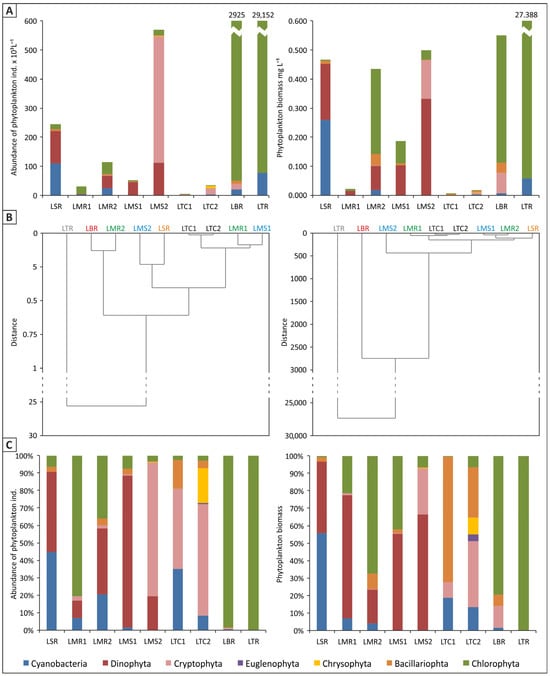

Chlorophytes were found to form the highest number of taxa. There were major differences in the total count of organisms in the individual water bodies, with the highest abundance of phytoplankton having been found in LTR—nearly 30,000 × 103 ind L−1. In contrast, a very low quantity was observed in LTC (3 × 103 ind L−1) in June (Figure 3A). The dendrograms included demonstrate a wide range of individual lake abundances (Figure 3B). In addition, the abundances ware several times higher in the July samples than in the June samples for LMS, LMR and LTC, which was most likely due to the increase in water temperature recorded in our study (Table 3) and the beginning of the growing season.

Figure 3.

Abundance of phytoplankton and phytoplankton biomass in six lakes in Bellsund: (A) calculated values, (B) degree of dissimilarity, (C) percentage of phytoplankton groups; source: own study.

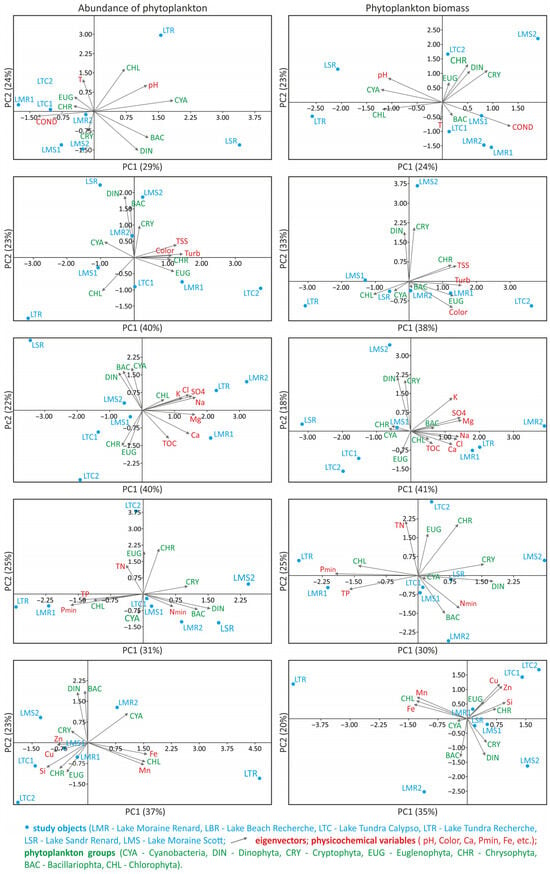

Chlorophytes were found to dominate in lakes with the highest phytoplankton abundance (Figure 3A,C), i.e., LTR and LBR, both located in the eastern and southern part of Recherchefjorden, near the shoreline. With regard to LBR, Monoraphidium contortum was the only green algae species that made up this abundance. In turn, LTR was dominated by Oocystis submarina, with the participation of other green algae species, the most prevalent of which were Botryococcus braunii, Elakatothrix lacustris, and three species of Pseudopediastrum: P. kawraiskyi, P. boryanum, P. integrum. In their totally low abundance in LMR close to the shoreline, chlorophytes were dominant in June (Chlamydomonas sp.) and co-dominant with dinophytes in July (Botryococcus braunii). PCA analysis revealed a directly proportional relationship between the quantity of green algae in LTR and LMR and ion content: Cl−, Na+, K+, SO42−, as well as Pmin, TP and content of microelements, such as Fe and Mn (Figure 4). The latter relationship appeared to be driven by the geological structure of the drainage basin area, namely the presence of iron-rich rocks. In contrast, inversely proportional relationships in chlorophyte abundance were observed with respect to COND, Nmin, and water clarity parameters: TSS, Colour, Turbidity (Figure 4). The strong relationship between turbidity and green algae abundance was also confirmed by a statistically significant negative correlation (Pearson’s coefficient, p ≤ 0.05) (Figure 5), which would indicate that green algae have higher light requirements in the water.

Figure 4.

Relationship between abundance and biomass of phytoplankton groups and environmental variables in bi-plot PCA analysis; source: own study.

Figure 5.

Heatmap of Pearson Correlation Coefficients between physicochemical parameters or elemental content of the studied lake water and the abundance and biomass of phytoplankton; source: own study.

The cryptophytes contributed significantly to overall phytoplankton load in two other lakes (LMS, LTC). These were primarily represented by Rhodomonas species. Their dominant development, as measured by percentage of abundance, occurred in July in the LMS water body at the moraine location—(Rh. pusilla) and in June and July in LTC (Rh. minuta) (Figure 3C). According to the PCA analysis, there was a noticeable inverse relationship in cryptophyte quantity with temperature (preferred cooler waters), Pmin, TP and Fe and Mn content. Cryptophyte abundance was noted to be directly proportional to the Nmin content of the waters (Figure 4). In turn, dinophytes dominated the planktonic algal community in LMS and LSR in June, owing to the development of Gymnodinium sp., which was also numerous in the LMS reservoir in the July (Figure 3A,C). PCA analysis showed a relationship between dinophyte mass and Nmin content, as well as an inverse relationship with Pmin, TP and TOC content in the waters (Figure 4). A significant proportion of cyanobacteria in phytoplankton abundance in the waters of the lakes under study (above 35%) appeared in June samples in LSR and LTC1 (different cyanobacteria species, among others, Dolichospermum sp., Planktolyngbya limnetica, Limnococcus limneticus) (Figure 3C). The PCA analysis demonstrated that the amount of Cyanobacteria was inversely related to TOC, COND, Ca2+ ions and the Si, Cu, and Zn microelements (Figure 4).

The considerable disparities in phytoplankton abundance in the waters under consideration translated into great variations in their biomass. The dendrograms show the degree of dissimilarity in biomass between different lakes (Figure 3B). LTR had a high biomass level (~28 mg L−1) due to the growth of the dominant species, Oocystis submarina. In other water bodies, biomass levels were significantly lower (0.004 to 0.550 mg L−1) (Figure 3A). When the percentage contribution of each category to the overall phytoplankton biomass of the examined lakes was analysed, chlorophytes dominated in the water bodies located nearest to the fjord shoreline (LTR, LBR, LMR2) (Figure 3C). In turn, dinophytes were clearly prevalent in LMS at the moraine area, which is located far from the shoreline (as is the case at the LMR moraine in June). Bacillariophyta dominated LTC, especially in the June sample (Figure 3C). It should be noted that LSR was the only lake in which cyanobacteria were found to be prevalent (Figure 3A,C). The PCA analysis revealed relationships between biomass of phytoplankton systematic groups and environmental variables that were comparable to those discovered for abundance (Figure 4). There was a significant relationship between chlorophyte biomass and Pmin, TP and TOC content, as well as an inverse relationship with total suspended solids and turbidity (TSS, Turb). The relationship between turbidity and chlorophytes biomass was also confirmed by Pearson’s coefficient (p ≤ 0.05) (Figure 5). According to PCA analysis, the biomass of dinophytes and cryptophytes had a relationship with Nmin content, but an inverse relationship with phosphorus (Pmin and TP), while cyanobacteria had an inverse relationship with COND (Figure 4).

4. Discussion

Spitsbergen’s small freshwater lakes have distinct physical and chemical properties that are influenced by the harsh Arctic climate, as well as by local hydrological and geological conditions. The surface water temperature in these lakes is heavily impacted by air temperature, insolation conditions, feeding type and lake depth. In addition, the temperature in the lake increases downstream of the fluvial-lake system [42,43]. The water temperatures measured in our study (7.1 to 13.9 °C) are higher than those previously recorded for the area [33,42] and probably come about due to climatic variability, both between years and during the season [7,44]. In a broader perspective, the observed increase in temperatures across the polar regions is a clear indicator of progressive climate change [45,46,47]. Rising air temperatures are causing significant warming of Arctic lakes, leading to changes in biogeochemical cycles and the ecological structure of lake ecosystems [48]. The pH levels of the waters in the lakes under study did not differ considerably from one another (8.2–8.8), in contrast to pH values recorded in other Svalbard lakes by other researchers (6.6 to 9.5) [8,49] and in subarctic ponds in Finland (4.3–7.4) [23]. The waters of Arctic lakes, even in limited geographical areas, exhibit a large range and quick change in this parameter. This is strongly tied to the productivity of these lakes and to weather conditions (snow melt, precipitation, sun) [8]. The highest pH levels are reported on sunny days, when intense photosynthetic activity induces an increase in pH values [50].

The mineralisation level of the waters recorded in our study (up to about 400 µS cm−1) was slightly higher than that reported by Ruman et al. [8] for the flow-through lakes of south-western Svalbard during the years 2010–2018. In the majority of cases, COND < 500 µS cm−1 was also recorded in lakes located in western [49] and Central Spitsbergen [51]. In turn, much lower COND < 50 µS cm−1 values were recorded in flow-through lakes in western Spitsbergen [42] and COND < 40 µS cm−1 was noted in subarctic freshwater mountain lakes in Finland [23]. COND in freshwater is most typically determined by the geological conditions of the area where the lake is located [8]. In our study, higher COND values were recorded in moraine-like water bodies (LMR and LMS). This results from the increased quantity of chlorides, sodium, sulphates and magnesium, which are primarily associated with the maritime environment, long-distance atmospheric transport [49], or a carbonate-rich geological substrate, such as dolomite. The impact of sea water expresses itself in numerous forms, including the effect of sea spray, salt spray created by the wind or sea aerosols [49,51]. This can be clearly seen in LMR and LMS, as well as in LTR. Another situation occurs when seawater seeps or overflows during storms, as demonstrated by the high-salinity LBR water body.

In freshwater ecosystems, nutrients that enter the aquatic environment have an impact on production and biodiversity [49]. Arctic ecosystems, including small freshwater lakes in Spitsbergen, are often characterized by nutrient deficiencies, particularly in phosphorus and nitrogen [52,53]. Our study has shown very low quantities of these elements, and these results are similar to other freshwater ponds in western Svalbard [49]. The low total nitrogen content in Arctic lakes, combined with a large amount of organic fraction, may indicate the influence of migrating waterbirds on water fertility, as suggested by Calizza et al. [54]. According to several researchers, the supply of nitrogen and phosphorus from mammalian and waterfowl activity is of key importance in lower lakes [42] and those closest to the shoreline [55,56]. Indeed, the role of birds as vectors for nutrient and pollutant transport has been extensively studied, particularly in polar regions [57,58,59]. Contemporary changes in lake chemistry can also be influenced by atmospheric nitrogen deposition, which can lead to the fertilisation of aquatic ecosystems [60]. Arctic lakes are often characterised by low phosphorus concentration, which limits their biological productivity [52]. However, the decrease in the proportion of mineral phosphorus to total phosphorus seen in our study in the summer is a normal phenomenon, which can be explained by the consumption of mineral forms of phosphorus by biological life during the short growing season in the Arctic [61].

Dissolved ion concentrations in lakes such as calcium, magnesium, sodium and potassium can be low as well. This can vary depending on local geology, the quantity of inflow from melting glaciers and thawing permafrost, and finally the distance from seawater, as confirmed by Chmiel et al. [53]. Bicarbonate, calcium and sulphate are the more abundant ions in lake waters [51]. In addition, chloride and sodium content may increase as a result of atmospheric deposition from the sea [42]. The observed content of metals and metalloids in the lakes under study was within the range of standard values documented in Spitsbergen surface waters [62,63]. Their presence and the content differences in western Svalbard’s fresh waters were linked to local geological conditions and supply to the lakes via bedrock weathering or atmospheric transport, as elements of natural and anthropogenic origin, as well as by way of meltwater from melting glaciers [62,63,64]. The instability in metal content shown in our work is a common phenomenon in Arctic surface waters, as confirmed by Ruman et al. [8], who conducted a study analysing metal content in lake waters between 2010 and 2018. These changes may have been caused by, for instance, the varying intensity of geological processes linked to temperature fluctuations and mineral surface reactions, the fluctuating amount of precipitation during the summer sampling period, the variability of local hydrological processes, the rate of bottom sediment resuspension, or atmospheric transport from great distances [8,65,66].

Organisms that inhabit Arctic ecosystems must adjust to the physicochemical features of the waters, which are shaped by the harsh Arctic climate. There are only few with a broad range of abiotic parameter tolerance that can adapt to such extreme instability within the aquatic environment in terms of physical characteristics and nutrient availability (hence the low diversity expressed by alpha diversity). Such organisms have only short periods of time to meet their life needs, which is why phytoplankton dynamics were so high. Indeed, the findings of this study shown significant variation in phytoplankton abundance among individual Arctic freshwater bodies, and are supported by previous research on phytoplankton in Arctic waters [24,25,26], despite the fact that the abundance and biomass values of freshwater phytoplankton in this area were typically low [9]. The study by Moedt et al. [67] in north-east Greenland, for example, showed that phytoplankton biomass and taxonomic composition exhibit high seasonal and annual variability. This was linked to temperature changes and earlier ice melt, which promoted phytoplankton growth, dominated by chrysophytes and dinoflagellates [67]. According to research conducted in the majority of other Arctic regions, chrysophytes and chlorophytes were also the dominant groups [68]. Our study showed that Chlorophyta had the highest number of taxa presence and the highest biomass and abundance values (however, they were low as compared to lakes from other temperate zones). These were notably dominant in the two lakes nearest to the shoreline, which had increased pH (pH > 8.5—LBR and LTR). In LTR, Oocystis submarina was the dominant species, accounting for about 20% of overall biomass. The species has been discovered in a variety of aquatic environments, most of which have a high pH, and in fresh, but especially brackish and saline waters [69,70,71,72], hence the name ‘freshwater marine’. The large proportion of O. submarina in the LTR waters was due to the vicinity of the lake to the bay’s shoreline and can be explained by contact with sea spray, as evidenced by the high values of chloride and sodium ions in the lake’s water (Table 3). Oocystis submarina is a common inhabitant of both saline and alkaline waters, and has been observed in a variety of specific environments, including a saline alkaline crater lake in central Mexico [72], soda lakes of south-eastern Transbaikalia, Russia [69] and it even forms a monoculture spring bloom in a shallow alkaline soda pan in Kiskunság National Park, Hungary [73]. The most dominant green alga in LBR was Monoraphidium contortum. The Monoraphidium species are cosmopolitan freshwater organisms that can inhabit moderately salty and alkaline environments similarly to O. submarina [74].

The higher percentage of Chlorophyta, particularly taxa that prefer eutrophic conditions or those that were on the border between meso- and eutrophic conditions, like M. contortum (LBR), O. submarina, Botryococcus braunii and taxa from the genus Pseudopediastrum (LTR), Chlamydomonas sp., and Coenocystis sp. (LMR) in water bodies closer to the sea may also have been linked to a higher influx of nutrients carried by runoff and rainwater that bring matter from the land in the form of organic and inorganic fractions. This phenomenon is well-documented and has been described for both lotic and lentic ecosystems [75,76,77,78,79]. Comparable Arctic region results were obtained by Sharov [80] and Hazuková et al. [81], who observed that diatoms and green algae were the most prevalent dominants, albeit their proportion changed depending on trophic conditions and dissolved organic carbon concentration. In turn, offshore water bodies may have different dynamics of nutrient availability, which may have favoured the dominance of flagellates (cryptophytes and dinophytes).

In our study, LTC and LMS, which were situated a few hundred meters from the shoreline and elevated above sea level at the highest level (35 and 71 m, respectively), were unique in terms of phytoplankton taxonomic composition. It should be noted that flagellates dominated the phytoplankton population, particularly during the summer (second study period). These lakes were distinguished from the others by having the poorest pool of inorganic nutrient components and the highest organic nitrogen level. Organic nitrogen (particularly in dissolved form) in stagnant water can originate mostly from direct, unaltered inputs from wet or dry deposition or terrestrial runoff [82]. It can also originate from decomposing organisms or be bound in living biomass. According to some studies, certain phytoplankton species are able to naturally take up dissolved organic nitrogen [83]. In addition, experimental studies have shown that phytoplankton can utilise dissolved organic matter as a nutrient source. These are organic substances present in lake water or that reach it via rivers and rainfall [84]. The ratio of mineral to organic nitrogen fractions, as well as the availability of the latter pool, are believed to have impacted the development of dinophytes in LMS and cryptophytes in LTC. Our research demonstrated that phytoplankton abundance and biomass at LTC was extremely low, and the lowest of any lake under study. This also results from Rhodomonas minuta dominance, which is typically not often represented in phytoplankton mass due to its small biovolume. Small flagellates are normally abundant in coloured, trophically poor waters [85], but their wide tolerance of physicochemical parameters allows them to colonize eutrophic reservoirs as well [86,87,88]. Cryptophytes and dinoflagellates are mixotrophic organisms that utilise mixotrophy as a survival strategy in the nutrient-limited environments of Arctic and Antarctic lakes [89]. This versatility in feeding allows them to thrive in extremely trophically poor lakes [90]. Cryptophytes are subjected to grazing, although the low intensity of foraging in most Arctic lakes likely benefits these fast-growing flagellates [85].

Regarding phytoplankton composition, as indicated from our study results, LSR and LMR were the most diversified in terms of taxonomy, although this diversity was not significant. The low taxonomic diversity of phytoplankton observed in the studied lakes (maximum 16 species identified in lake LMR during the second sampling period) can be explained by the extremely short growing season characteristic of the Arctic region. Such a compressed vegetative period imposes strong environmental constraints, resulting in a very rapid pace of ecological succession under conditions that are highly challenging for survival [91]. Consequently, only a limited number of taxa are able to establish and persist. These are primarily species exhibiting exceptional physiological plasticity and advanced adaptive traits that enable them to tolerate low temperatures, limited light availability, and pronounced seasonal variability [92]. Although these external conditions are highly unfavorable, once suitable ecological niches are identified, such taxa are capable of successful development and reproduction, leading to simplified but functionally adapted phytoplankton communities [93]. The phytoplankton structure expressed in terms of abundance and biomass included a distribution between dinoflagellates and green algae with the clear participation of cyanobacteria. Cyanobacteria notably constituted a quantitatively significant component in LSR, accounting for 45% of total abundance and 56% of biomass. The reason for this lake’s high proportion of cyanobacteria is unknown. The only difference between LSR and LMR and the other lakes under study was the considerable amount of available nitrogen. This could explain the higher abundance of Planktolyngbya limnetica; however, diazotrophic Dolichospermum sp. was even more prevalent. The proximity of the two lakes may be the common factor for the presence of cyanobacteria in both these water bodies. Additionally, large bird colonies were frequently found in LSR, suggesting that this vector in the transfer of forms, whether vegetative or resting, may have been crucial in creating a similar microbial flora in both water bodies. Animal activity, particularly that of birds, can significantly influence phytoplankton composition and abundance by modelling algal assemblages and supplying nutrients. A study by Côté et al. [94] has shown that waterbirds, particularly geese, can significantly enrich freshwater bodies with nitrogen and phosphorus through their faeces, which can lead to increased primary production. Researchers who conducted their work in a small pond in the northern part of Svalbard came to similar conclusions. Based upon an analysis of the taxonomic composition and abundance of zooplankton, it was concluded that there was definitely increased productivity in this ecosystem, as evidenced by a rise in phytoplankton biomass. This, in turn, was caused by the enrichment of the lake’s waters with goose guano from the growing population of these birds in the study area, which has become more favorable to birds due to climate warming [95]. Birds can replenish waters with nutrients, making it a “friendlier” habitat for algal colonisation, but they can also act as vectors for microorganism migration between water bodies. There has been research on birds and other animals transferring resting stages of algae in a process known as ‘zoochory’ [96,97,98]. Algae and their resting stages can be found in soil particles attached to waterbird paws and feathers. Other species, including invertebrates, such as dragonflies or water beetles, are also known to be dispersers of algae [99,100]; however, the involvement of invertebrates (insects) in the transfer of unicellular organisms in the Arctic zone is severely limited.

In summary, the findings of this study are consistent with prior research and show that the composition and abundance of phytoplankton in Arctic freshwater bodies are controlled by seasonal dynamics, water chemistry and biotic pressure. Further long-term study is required to assess the impact of climate change on these ecosystems and forecast future trends in phytoplankton function in a warming Arctic climate.

5. Conclusions

The physicochemical composition of the lakes studied within the Bellsund region showed variance among lakes and measurement dates, demonstrating both local and time variability. This variation was caused by geological factors, hydrology, climate, marine impact and bird activity. Nutrient concentrations were low in all lakes under study. This demonstrates the limited availability of these components, which affect the poor biological production and specific dynamics of freshwater ecosystems during the short ablation period.

The phytoplankton in the lakes under study was low in quantity (measured by both fresh biomass and abundance) and quality (measured by alpha and beta diversity within and between lakes). There was a noticeable distinction between lakes dominated by chlorophyta, those dominated by flagellates and those with a more diversified species structure (cyanobacteria/chlorophyta/dinoflagellates). The dominant taxa were as follows: Rhodomonas minuta, Gymnodinium sp., Monoraphidium contortum, Oocystis submarina, Botryococcus braunii, Dolichospermum sp. It should be noted that chlorophyta were clearly dominant in the lakes nearest to the fjord’s shoreline, but dinoflagellates and cryptophytes dominated lakes further inland. The significant differences in phytoplankton abundance were greatly influenced by the physicochemical parameters of the waters. The chlorophyta content increased with higher ion concentrations (Cl−, Na+, K+, SO42−), Pmin, and Fe and Mn. Flagellate favoured cooler waters with higher Nmin and low TOC, while cyanobacteria preferred waters with lower COND, TOC, Ca2+, Si, Cu and Zn. In turn, phytoplankton biomass varied significantly both in terms of space and time, with an increase in July associated with higher water temperatures.

Vectors of key importance in phytoplankton dispersal are animals, primarily birds. The water bodies that birds visited most frequently had the greatest taxonomic variety of phytoplankton (LTR, LTC, LSR). More research on Arctic freshwater ecosystems is necessary, since they are unique to the region and play a key role in determining the material cycles and climate of the region, but more importantly, they are crucial to the development of Arctic flora and fauna during the ablation season (as a residence/resting place for animals, particularly large bird populations).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.Z., M.P., M.K. and Ł.F.; methodology, M.Z., Ł.F., M.P. and M.K.; validation, M.K., M.P. and M.Z.; formal analysis, M.K. and Ł.F., investigation, Ł.F. (field measurements and sample collection), M.K. (laboratory chemical analyses), M.Z. and M.P. (phytoplankton analyses); data curation, M.Z., M.P. and M.K.; writing—original draft preparation, M.Z.; writing—review and editing, M.Z., M.P. and M.K.; visualization, Ł.F. and M.K.; supervision, M.Z. and M.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Dahlke, S. Rapid Climate Changes in the Arctic Region of Svalbard: Processes, Implications and Representativeness for the Broader Arctic. Ph.D. Thesis, Universitäsverlag Potsdam, Potsdam, Germany, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Park, J.H.; Kim, S.-J.; Lim, H.-G.; Kug, J.-S.; Yang, E.J.; Kim, B.-M. Phytoplankton Responses to Increasing Arctic River Discharge under the Present and Future Climate Simulations. Environ. Res. Lett. 2023, 18, 064037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordli, Ø.; Przybylak, R.; Ogilvie, A.E.J.; Isaksen, K. Long-Term Temperature Trends and Variability on Spitsbergen: The Extended Svalbard Airport Temperature Series, 1898–2012. Polar Res. 2014, 33, 21349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, S.; Kim, H.; Nam, S.-I.; Choi, K.-H.; Kim, T.-W.; Yun, S.T.; Kim, H.S.; Kim, T.-H.; Han, D.; Ko, Y.H.; et al. The Composition and Abundance of Phytoplankton after Spring Bloom in the Arctic Svalbard Fjords. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 2022, 275, 107970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krajewska, M.; Szymczak-Żyła, M.; Tylmann, W.; Kowalewska, G. Climate Change Impact on Primary Production and Phytoplankton Taxonomy in Western Spitsbergen Fjords Based on Pigments in Sediments. Glob. Planet. Chang. 2020, 189, 103158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Payne, C.M.; Roesler, C.S. Characterizing the Influence of Atlantic Water Intrusion on Water Mass Formation and Phytoplankton Distribution in Kongsfjorden, Svalbard. Cont. Shelf Res. 2019, 191, 104005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franczak, Ł. Development and Functioning of Catchment-Lake Systems at the Forefield of the Scott and Renard Glaciers (NW Part of the Wedel Jarlsberg Land, Spitsbergen). Ph.D. Thesis, Maria Curie-Skłodowska University, Lublin, Poland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Ruman, M.; Kosek, K.; Koziol, K.; Ciepły, M.; Kozak-Dylewska, K.; Polkowska, Ż. A High-Arctic Flow-through Lake System Hydrochemical Changes: Revvatnet, Southwestern Svalbard (Years 2010–2018). Chemosphere 2021, 275, 130046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rautio, M.; Dufresne, F.; Laurion, I.; Bonilla, S.; Vincent, W.F.; Christoffersen, K.S. Shallow Freshwater Ecosystems of the Circumpolar Arctic. Écoscience 2011, 18, 204–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubečková, K.; Elster, J.; Kanda, H. Periphyton Ecology of Glacial and Snowfed Streams, Ny-Ålesund, Svalbard: The Influence of Discharge Disturbances Due to Sloughing, Scraping and Peeling. Nova Hedwig. Beih. 2001, 123, 139–170. [Google Scholar]

- Kvíderová, J. Research on Cryosestic Communities in Svalbard: The Snow Algae of Temporary Snowfields in Petuniabukta, Central Svalbard. Czech Polar Rep. 2012, 2, 8–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stibal, M.; Šabacká, M.; Kaštovská, K. Microbial Communities on Glacier Surfaces in Svalbard: Impact of Physical and Chemical Properties on Abundance and Structure of Cyanobacteria and Algae. Microb. Ecol. 2006, 52, 644–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matuła, J.; Pietryka, M.; Richter, D.; Wojtuń, B. Cyanoprokaryota and Algae of Arctic Terrestrial Ecosystems in the Hornsund Area, Spitsbergen. Pol. Polar Res. 2007, 28, 283–315. [Google Scholar]

- Fredriksen, S.; Røst Kile, M. The Algal Vegetation in the Outer Part of Isfjorden, Spitsbergen: Revisiting Per Svendsen’s Sites 50 Years Later. Polar Res. 2012, 31, 17538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piquet, A.M.-T.; van de Poll, W.H.; Visser, R.J.W.; Wiencke, C.; Bolhuis, H.; Buma, A.G.J. Springtime Phytoplankton Dynamics in Arctic Krossfjorden and Kongsfjorden (Spitsbergen) as a Function of Glacier Proximity. Biogeosciences 2014, 11, 2263–2279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiktor, J.; Wojciechowska, K. Differences in Taxonomic Composition of Summer Phytoplankton in Two Fjords of West Spitsbergen, Svalbard. Pol. Polar Res. 2005, 26, 259–268. [Google Scholar]

- Komárek, J.; Kovacik, L. Schizotrichacean Cyanobacteria from Central Spitsbergen (Svalbard). Polar Biol. 2013, 36, 1811–1822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hejduková, E.; Elster, J.; Nedbalová, L. Annual Cycle of Freshwater Diatoms in the High Arctic Revealed by Multiparameter Fluorescent Staining. Microb. Ecol. 2020, 80, 559–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zgrundo, A.; Wojtasik, B.; Convey, P.; Majewska, R. Diatom Communities in the High Arctic Aquatic Habitats of Northern Spitsbergen (Svalbard). Polar Biol. 2017, 40, 873–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heesch, S.; Pažoutová, M.; Moniz, M.B.J.; Rindi, F. Prasiolales (Trebouxiophyceae, Chlorophyta) of the Svalbard Archipelago: Diversity, Biogeography and Description of the New Genera Prasionella and Prasionema. Eur. J. Phycol. 2016, 51, 171–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenzenweger, R.; Lütz, C. A Contribution to Knowledge of the Desmid Flora (Desmidiaceae, Zygnemaphyceae) of Spitzbergen. Algol. Stud. Arch. Hydrobiol. 2006, 119, 79–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richter, D.; Matuła, J.; Pietryka, M. The Northernmost Populations of Tetraspora Gelatinosa (Chlorophyta) from Spitsbergen. Pol. Polar Res. 2014, 35, 521–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heikkinen, J.M.; Niittynen, P.; Soininen, J.; Pajunen, V. Patterns and Drivers for Benthic Algal Biomass in Sub-Arctic Mountain Ponds. Hydrobiologia 2024, 851, 689–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willen, T. Phytoplankton from Lakes and Ponds on Vestspitsbergen. Acta Phytogeogr. Suec. 1980, 68, 173–188. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, G.H.; Klochkova, T.A.; Kang, S.H. Notes on Freshwater and Terrestrial Algae from Ny-Ålesund, Svalbard (High Arctic Sea Area). J. Environ. Biol. 2008, 29, 485–491. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kim, G.H.; Klochkova, T.A.; Han, J.W.; Kang, S.-H.; Choi, H.G.; Chung, K.W.; Kim, S.J. Freshwater and Terrestrial Algae from Ny-Ålesund and Blomstrandhalvøya Island (Svalbard). J. Environ. Biol. 2011, 64, 25–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holzinger, A.; Roleda, M.Y.; Lütz, C. The Vegetative Arctic Freshwater Green Alga Zygnema Is Insensitive to Experimental UV Exposure. Micron 2009, 40, 831–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dallmann, W.K.; Hjelle, A.; Ohta, Y.; Salvigsen, O.; Bjornerud, M.G.; Hauser, E.C.; Maher, H.D.; Craddock, C. Geological Map of Svalbard 1:100 000, Sheet B 11 G; Norwegian Polar Institute: Tromsø, Norway, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Hjelle, A. Geology of Svalbard; Polarhandbook 7; Norsk Polarinstitutt: Oslo, Norway, 1993; ISBN 978-82-7666-057-9. [Google Scholar]

- Landvik, J.Y.; Bolstad, M.; Lycke, A.K.; Mangerud, J.; Sejrup, H.P. Weichselian Stratigraphy and Palaeoenvironments at Bellsund, Western Svalbard. Boreas 1992, 21, 335–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pękala, K.; Repelewska-Pękalowa, J.; Zagórski, P. Quaternary Deposits and Stratigraphy. In The Geographical Environment of NW Part of Wedel Jarlsberg Land (Spitsbergen, Svalbard); Zagórski, P., Harasimiuk, M., Rodzik, J., Eds.; UMCS: Lublin, Poland, 2013; pp. 48–63. [Google Scholar]

- Reder, J.; Zagórski, P. Recession and Development of Marginal Zone of the Renard Glacier. Landform Anal. 2007, 5, 175–178. [Google Scholar]

- Szumińska, D.; Szopińska, M.; Lehmann-Konera, S.; Franczak, Ł.; Kociuba, W.; Chmiel, S.; Kalinowski, P.; Polkowska, Ż. Water Chemistry of Tundra Lakes in the Periglacial Zone of the Bellsund Fiord (Svalbard) in the Summer of 2013. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 624, 1669–1679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PN-EN ISO 5667-1:2022-07; Water Quality—Sampling—Part 1: Guidelines for Developing Sampling Programs and Sampling Techniques. Polish Committee for Standardization: Warsaw, Poland, 2022.

- PN-EN ISO 5667-3:2018-08; Water Quality—Sampling—Part 3: Guidelines for the Preservation and Handling of Water Samples. Polish Committee for Standardization: Warsaw, Poland, 2018.

- Utermöhl, H. Zur Vervollkommnung Der Quantitativen Phytoplankton-Methodik: Mit 1 Tabelle Und 15 Abbildungen Im Text Und Auf 1 Tafel. Mitt. Int. Ver. Theor. Angew. Limnol. 1958, 9, 1–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillebrand, H.; Dürselen, C.-D.; Kirschtel, D.; Pollingher, U.; Zohary, T. Biovolume Calculation for Pelagic and Benthic Microalgae. J. Phycol. 1999, 35, 403–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lepš, J.; Šmilauer, P. Multivariate Analysis of Ecological Data Using CANOCO; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2003; ISBN 978-0-511-61514-6. [Google Scholar]

- Diez, D.; C¸etinkaya-Rundel, M.; Barr, C.D. OpenIntro Statistics, 4th ed.; OpenIntro: Mountain View, CA, USA, 2019; ISBN 978-1-943450-07-7. [Google Scholar]

- PN-EN ISO 14911:2002; Water Quality—Determination of Dissolved Li+, Na+, NH4+, K+, Mn2+, Ca2+, Mg2+, Sr2+ and Ba2+ Using Ion Chromatography—Method for Water and Waste Water. Polish Committee for Standardization: Warsaw, Poland, 2002.

- PN-EN ISO 10304-1:2009; Water Quality—Determination of Dissolved Anions by Liquid Chromatography of Ions—Part 1: Determination of Bromide, Chloride, Fluoride, Nitrate, Nitrite, Phosphate and Sulfate. Polish Committee for Standardization: Warsaw, Poland, 2009.

- Marszałek, H.; Górniak, D. Changes in Water Chemistry along the Newly Formed High Arctic Fluvial–Lacustrine System of the Brattegg Valley (SW Spitsbergen, Svalbard). Environ. Earth Sci. 2017, 76, 449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krawczyk, W.E.; Bartoszewski, S.A.; Siwek, K. Rain Water Chemistry at Calypsobyen, Svalbard. Pol. Polar Res. 2008, 29, 149–162. [Google Scholar]

- Mędrek, K.; Gluza, A.; Siwek, K.; Zagórski, P. Warunki meteorologiczne na stacji w Calypsobyen w sezonie letnim 2014 na tle wielolecia 1986–2011 (The meteorological conditions on the Calypsobyen in summer 2014 on the background of multiyear 1986–2011). Probl. Klim. Polar. 2014, 24, 37–50. [Google Scholar]

- Livingstone, S.J.; Li, Y.; Rutishauser, A.; Sanderson, R.J.; Winter, K.; Mikucki, J.A.; Björnsson, H.; Bowling, J.S.; Chu, W.; Dow, C.F.; et al. Subglacial Lakes and Their Changing Role in a Warming Climate. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2022, 3, 106–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prowse, T.D.; Wrona, F.J.; Reist, J.D.; Gibson, J.J.; Hobbie, J.E.; Lévesque, L.M.J.; Vincent, W.F. Climate Change Effects on Hydroecology of Arctic Freshwater Ecosystems. AMBIO J. Hum. Environ. 2006, 35, 347–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woelders, L.; Lenaerts, J.T.M.; Hagemans, K.; Akkerman, K.; van Hoof, T.B.; Hoek, W.Z. Recent Climate Warming Drives Ecological Change in a Remote High-Arctic Lake. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 6858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vincent, W.F.; Callaghan, T.V.; Dahl-Jensen, D.; Johansson, M.; Kovacs, K.M.; Michel, C.; Prowse, T.; Reist, J.D.; Sharp, M. Ecological Implications of Changes in the Arctic Cryosphere. Ambio 2011, 40, 87–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, T.C.; Walseng, B.; Hessen, D.O.; Dimante-Deimantovica, I.; Novichkova, A.A.; Chertoprud, E.S.; Chertoprud, M.V.; Sakharova, E.G.; Krylov, A.V.; Frisch, D.; et al. Changes in Trophic State and Aquatic Communities in High Arctic Ponds in Response to Increasing Goose Populations. Freshw. Biol. 2019, 64, 1241–1254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tank, S.E.; Lesack, L.F.W.; McQueen, D.J. Elevated pH Regulates Bacterial Carbon Cycling in Lakes with High Photosynthetic Activity. Ecology 2009, 90, 1910–1922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazurek, M.; Paluszkiewicz, R.; Rachlewicz, G.; Zwoliński, Z. Variability of Water Chemistry in Tundra Lakes, Petuniabukta Coast, Central Spitsbergen, Svalbard. Sci. World J. 2012, 2012, 596516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis-Evans, J.C.; Galchenko, V.; Laybourn-Parry, J.; Mylnikov, A.P.; Petz, W. Environmental Characteristics and Microbial Plankton Activity of Freshwater Environments at Kongsfjorden, Spitsbergen (Svalbard). Arch. Hydrobiol. 2001, 152, 609–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chmiel, S.; Bartoszewski, S.; Gluza, A.; Siwek, K.; Zagórski, P. Physicochemical Characteristics of Land Waters in the Bellsund Region (Spitsbergen). Landform Anal. 2007, 5, 13–15. [Google Scholar]

- Calizza, E.; Salvatori, R.; Rossi, D.; Pasquali, V.; Careddu, G.; Sporta Caputi, S.; Maccapan, D.; Santarelli, L.; Montemurro, P.; Rossi, L.; et al. Climate-Related Drivers of Nutrient Inputs and Food Web Structure in Shallow Arctic Lake Ecosystems. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 2125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clyde, N.; Hargan, K.E.; Forbes, M.R.; Iverson, S.A.; Blais, J.M.; Smol, J.P.; Bump, J.K.; Gilchrist, H.G. Seaduck Engineers in the Arctic Archipelago: Nesting Eiders Deliver Marine Nutrients and Transform the Chemistry of Island Soils, Plants, and Ponds. Oecologia 2021, 195, 1041–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zmudczyńska-Skarbek, K.; Balazy, P. Following the Flow of Ornithogenic Nutrients through the Arctic Marine Coastal Food Webs. J. Mar. Syst. 2017, 168, 31–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziółek, M.; Bartmiński, P.; Stach, A. The Influence of Seabirds on the Concentration of Selected Heavy Metals in Organic Soil on the Bellsund Coast, Western Spitsbergen. Arct. Antarct. Alp. Res. 2017, 49, 507–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziółek, M.; Melke, J. The Impact of Seabirds on the Content of Various Forms of Phosphorus in Organic Soils of the Bellsund Coast, Western Spitsbergen. Polar Res. 2014, 33, 19986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zwolicki, A.; Zmudczyńska-Skarbek, K.M.; Iliszko, L.; Stempniewicz, L. Guano Deposition and Nutrient Enrichment in the Vicinity of Planktivorous and Piscivorous Seabird Colonies in Spitsbergen. Polar Biol. 2013, 36, 363–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmgren, S.U.; Bigler, C.; Ingólfsson, Ó.; Wolfe, A.P. The Holocene–Anthropocene Transition in Lakes of Western Spitsbergen, Svalbard (Norwegian High Arctic): Climate Change and Nitrogen Deposition. J. Paleolimnol. 2010, 43, 393–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosek, K.; Luczkiewicz, A.; Kozioł, K.; Jankowska, K.; Ruman, M.; Polkowska, Ż. Environmental Characteristics of a Tundra River System in Svalbard. Part 1: Bacterial Abundance, Community Structure and Nutrient Levels. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 653, 1571–1584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chmiel, S.; Reszka, M.; Rysiak, A. Heavy Metals and Radioactivity in Environmental Samples of the Scott Glacier Region on Spitsbergen in Summer 2005. Quaest. Geogr. A 2009, 28, 23–29. [Google Scholar]

- Jóźwiak, M.; Jóźwiak, M. The Heavy Metals in Water of Select Spitsbergen and Iceland Glaciers. Landform Anal. 2007, 5, 32–34. [Google Scholar]

- Lehmann-Konera, S.; Kociuba, W.; Chmiel, S.; Franczak, Ł.; Polkowska, Ż. Effects of Biotransport and Hydro-Meteorological Conditions on Transport of Trace Elements in the Scott River (Bellsund, Spitsbergen). PeerJ 2021, 9, e11477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colombo, N.; Salerno, F.; Gruber, S.; Freppaz, M.; Williams, M.; Fratianni, S.; Giardino, M. Review: Impacts of Permafrost Degradation on Inorganic Chemistry of Surface Fresh Water. Glob. Planet. Chang. 2018, 162, 69–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudnicka-Kępa, P.; Zaborska, A. Sources, Fate and Distribution of Inorganic Contaminants in the Svalbard Area, Representative of a Typical Arctic Critical Environment—A Review. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2021, 193, 724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moedt, S.M.; Olrik, K.; Schmidt, N.M.; Jeppesen, E.; Christoffersen, K.S. Long-Term Phytoplankton Dynamics in Two High Arctic Lakes (North-East Greenland). Freshw. Biol. 2024, 69, 403–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schartau, A.K.; Mariash, H.L.; Christoffersen, K.S.; Bogan, D.; Dubovskaya, O.P.; Fefilova, E.B.; Hayden, B.; Ingvason, H.R.; Ivanova, E.A.; Kononova, O.N.; et al. First Circumpolar Assessment of Arctic Freshwater Phytoplankton and Zooplankton Diversity: Spatial Patterns and Environmental Factors. Freshw. Biol. 2022, 67, 141–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afonina, E.Y.; Tashlykova, N.A. Phytoplankton and Zooplankton Succession during the Dry–Refilling Cycle: A Case Study in Large, Fluctuating Soda Lakes. Freshw. Biol. 2023, 68, 987–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latała, A.; Hamoud, N.; Pliński, M. Growth Dynamics and Morphology of Plankton Green Algae from Brackish Waters under the Influence of Salinity, Temperature and Light. Acta Ichthyol. Piscat. 1991, 21, 101–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moisander, P.H.; Rantajärvi, E.; Huttunen, M.; Kononen, K. Phytoplankton Community in Relation to Salinity Fronts at the Entrance to the Gulf of Finland, Baltic Sea. Ophelia 1997, 46, 187–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliva, M.G.; Lugo, A.; Alcocer, J.; Peralta, L.; del Rosario Sánchez, M. Phytoplankton Dynamics in a Deep, Tropical, Hyposaline Lake. Hydrobiologia 2001, 466, 299–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korponai, K.; Szabó, A.; Somogyi, B.; Boros, E.; Borsodi, A.K.; Jurecska, L.; Vörös, L.; Felföldi, T. Dual Bloom of Green Algae and Purple Bacteria in an Extremely Shallow Soda Pan. Extremophiles 2019, 23, 467–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, A.C. Las Chlorococcales Dulciacuícolas de Cuba; Bibliotheca Phicologica; J. Cramer: Berlin–Stuttgart, Germany, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Allan, J.D.; Castillo, M.M. Nutrient Dynamics. In Stream Ecology: Structure and Function of Running Waters; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2007; pp. 255–285. ISBN 978-1-4020-5583-6. [Google Scholar]

- Dupas, R.; Abbott, B.W.; Minaudo, C.; Fovet, O. Distribution of Landscape Units Within Catchments Influences Nutrient Export Dynamics. Front. Environ. Sci. 2019, 7, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeppesen, E.; Kronvang, B.; Meerhoff, M.; Søndergaard, M.; Hansen, K.M.; Andersen, H.E.; Lauridsen, T.L.; Liboriussen, L.; Beklioglu, M.; Ozen, A.; et al. Climate Change Effects on Runoff, Catchment Phosphorus Loading and Lake Ecological State, and Potential Adaptations. J. Environ. Qual. 2009, 38, 1930–1941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Martín, M.Á. Understanding Nutrient Loads from Catchment and Eutrophication in a Salt Lagoon: The Mar Menor Case. Water 2023, 15, 3569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinckney, J.L.; Paerl, H.W.; Tester, P.; Richardson, T.L. The Role of Nutrient Loading and Eutrophication in Estuarine Ecology. Environ. Health. Perspect. 2001, 109, 699–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharov, A.N. Phytoplankton of Cold-Water Lake Ecosystems under the Influence of Natural and Anthropogenic Factors. Issues Mod. Algol. 2021, 1, 42–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazuková, V.; Burpee, B.T.; McFarlane-Wilson, I.; Saros, J.E. Under Ice and Early Summer Phytoplankton Dynamics in Two Arctic Lakes with Differing DOC. J. Geophys. Res. Biogeosci. 2021, 126, e2020JG005972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willett, V.B.; Reynolds, B.A.; Stevens, P.A.; Ormerod, S.J.; Jones, D.L. Dissolved Organic Nitrogen Regulation in Freshwaters. J. Environ. Qual. 2004, 33, 201–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paerl, H.W. Ecophysiological and Trophic Implications of Light-Stimulated Amino Acid Utilization in Marine Picoplankton. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1991, 57, 473–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Granéli, E.; Carlsson, P.; Legrand, C. The Role of C, N and P in Dissolved and Particulate Organic Matter as a Nutrient Source for Phytoplankton Growth, Including Toxic Species. Aquat. Ecol. 1999, 33, 17–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forrström, L. Phytoplankton Ecology of Subarctic Lakes in Finnish Lapland. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Helsinki, Helsinki, Finland, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Ferencz, B.; Toporowska, M.; Dawidek, J.; Sobolewski, W. Hydro-Chemical Conditions of Shaping the Water Quality of Shallow Łęczna-Włodawa Lakes (Eastern Poland). CLEAN—Soil Air Water 2017, 45, 1600152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poniewozik, M.; Lenard, T. Phytoplankton Composition and Ecological Status of Lakes with Cyanobacteria Dominance. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 3832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šupraha, L.; Bosak, S.; Ljubešić, Z.; Mihanović, H.; Olujić, G.; Mikac, I.; Viličić, D. Cryptophyte Bloom in a Mediterranean Estuary: High Abundance of Plagioselmis Cf. Prolonga in the Krka River Estuary (Eastern Adriatic Sea). Sci. Mar. 2014, 78, 329–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laybourn-Parry, J.; Marshall, W.A. Photosynthesis, Mixotrophy and Microbial Plankton Dynamics in Two High Arctic Lakes during Summer. Polar Biol. 2003, 26, 517–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laybourn-Parry, J.; Roberts, E.; Bell, E. Mixotrophy as a Survival Strategy in Antarctic Lakes. In Antarctic Ecosystems: Models for Wider Ecological Understanding; Davison, W., Howard-Williams, C., Broady, P., Eds.; New Zealand Natural Sciences: Christchurch, New Zealand, 2000; pp. 33–40. ISBN 0473 06877 X. [Google Scholar]

- Calbet, A. Plankton Adaptations to Extreme Environments. In The Wonders of Marine Plankton; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 95–101. ISBN 978-3-031-50765-6. [Google Scholar]

- Lyon, B.R.; Mock, T.; Lyon, B.R.; Mock, T. Polar Microalgae: New Approaches towards Understanding Adaptations to an Extreme and Changing Environment. Biology 2014, 3, 56–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padisák, J.; Naselli-Flores, L. Phytoplankton in Extreme Environments: Importance and Consequences of Habitat Permanency. Hydrobiologia 2021, 848, 157–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Côté, G.; Pienitz, R.; Velle, G.; Wang, X. Impact of Geese on the Limnology of Lakes and Ponds from Bylot Island (Nunavut, Canada). Int. Rev. Hydrobiol. 2010, 95, 105–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luoto, T.P.; Brooks, S.J.; Salonen, V.-P. Ecological Responses to Climate Change in a Bird-Impacted High Arctic Pond (Nordaustlandet, Svalbard). J. Paleolimnol. 2014, 51, 87–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figuerola, J.; Green, A.J. Dispersal of Aquatic Organisms by Waterbirds: A Review of Past Research and Priorities for Future Studies. Freshw. Biol. 2002, 47, 483–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Incagnone, G.; Marrone, F.; Barone, R.; Robba, L.; Naselli-Flores, L. How Do Freshwater Organisms Cross the “Dry Ocean”? A Review on Passive Dispersal and Colonization Processes with a Special Focus on Temporary Ponds. Hydrobiologia 2015, 750, 103–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naselli-Flores, L.; Padisák, J. Blowing in the Wind: How Many Roads Can a Phytoplanktont Walk down? A Synthesis on Phytoplankton Biogeography and Spatial Processes. Hydrobiologia 2016, 764, 303–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristiansen, J. 16. Dispersal of Freshwater Algae—A Review. Hydrobiologia 1996, 336, 151–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, K.W.; Schlichting, H.E. Dispersal of Algae and Protozoa by Selected Aquatic Insects. J. Ecol. 1966, 54, 551–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.