Abstract

Construction and demolition waste, when used as the substrates of constructed wetlands, provide notable environmental benefits: purification performances and substantial economic advantages compared with conventional substrates such as gravels. However, the high effluent pH induced by waste concrete severely restricts its practical application in such systems. The body of research focused on overcoming this limitation is rather limited. To address this limitation, this study proposed a strategy based on the configurations of acid alkaline substrates. A pilot-scale vertical flow constructed wetland experiment was carried out to evaluate the feasibility of this approach through three treatments: (1) waste concrete alone (Concrete), (2) waste concrete as the upper layer combined with perlite (an acidic substrate (Concrete + Perlite)), and (3) a uniform mixture of waste concrete and perlite (Mixed). The results demonstrate that the Concrete treatment exhibited a persistent high pH problem, where the effluent pH values remained above 9, even after five months of operation. In contrast, the Concrete + Perlite and Mixed treatments effectively mitigated the excessive effluent pH (<8.2). Relative to the Concrete treatment, both the Concrete + Perlite and Mixed treatments significantly enhanced the removal efficiencies of chemical oxygen demand (COD) (from 43.7% to above 68.5%), total nitrogen (TN) (from 31.8% to above 86.5%), and ammonium nitrogen (NH4+-N) (from 96.7% to 96.9%), whereas the removal efficiency of total phosphorous (TP) showed only a slight decrease. No significant differences in pollutant removal performance were observed between the Concrete + Perlite and Mixed treatments. Moreover, the Concrete + Perlite and Mixed treatments substantially increased the bacterial diversity within the substrate biofilm compared with the Concrete treatment, although differences in the bacterial community composition between the Concrete + Perlite and Mixed were relatively minor. Overall, configuring pH-balanced substrates through the combination of acidic and alkaline matrices provided effective and sustainable integrity for promoting the resource of construction and demolition waste in constructed wetlands.

1. Introduction

Substrates represent the most critical component of constructed wetlands. The selection and configuration of substrates not only constitute a vital aspect in the design of constructed wetlands but also serve as one of the primary factors determining the pollutant purification function of such wetlands [1]. Currently, a growing number of materials have been developed for use as substrates in constructed wetlands. Construction and demolition waste (CDW), when utilized as a substrate for constructed wetlands, exhibits advantages including cost-effectiveness, high efficiency, and resource recycling, thereby boasting broad application prospects [2]. This is particularly relevant against the backdrop where constructed wetlands are now widely employed in the advanced treatment of various types of wastewater [3,4,5]—particularly alongside the rapid urbanization in China, which generates billions of tons of CDW annually—endowing it with significant practical implications [5,6].

Waste concrete accounts for nearly 50% of CDW [7], and its proportion is gradually increasing with the declining usage of fired bricks. Crushed waste concrete aggregates feature a rough outer surface, which, when used as a constructed wetland substrate, can provide a larger specific surface area for microbial attachment. Furthermore, concrete aggregates exhibit a strong capacity to adsorb inorganic phosphorus in water bodies [8], thereby significantly reducing the phosphorus concentration in the water [9]. Under the conditions of pH 7–8 and an initial phosphate concentration of 10 mg/L, the removal efficiency of phosphate by recycled concrete aggregates (RCAs) reaches as high as 99.54% [10]. Additionally, in a vertical flow constructed wetland (VFCW) system (CW2) with mixed substrates of 50% recycled brick aggregates (RBAs) + 50% recycled concrete aggregates (RCAs), waste concrete exhibits a certain removal capacity for chemical oxygen demand (COD) and ammonium nitrogen (NH4+-N) in aqueous solutions, with respective removal efficiencies of up to 63.5% and 70.2% [2]. However, when employed as a constructed wetland substrate, waste concrete has a relatively high alkalinity, which can significantly inhibit the activity of microorganisms in the surface biofilm, consequently impairing the purification function of the wetland [11]. In addition, the extensive use of concrete aggregates in constructed wetlands may lead to excessive pH levels in the effluent, where the pH of its effluent can reach up to 9.30 or even higher [10], posing potential ecological risks [12,13]. Addressing the issue of excessively high alkalinity of waste concrete as a constructed wetland substrate is a key determinant of whether it can be widely developed for this application.

Previous studies primarily focused on adopting surface sealing [14,15], or the addition of acidic additives to reduce the pH of waste concrete [16], whereas few studies have employed the method of matrix combination to address the issue of excessively high pH in waste concrete. This paper proposes a strategy involving the mixed use of acidic substrates and waste concrete to resolve the problem of excessive alkalinity when waste concrete is used as a constructed wetland substrate. A small-scale vertical flow experiment was conducted to verify the feasibility of this strategy, aiming to provide a theoretical basis for expanding the application of waste concrete as a constructed wetland substrate.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Design and Operation

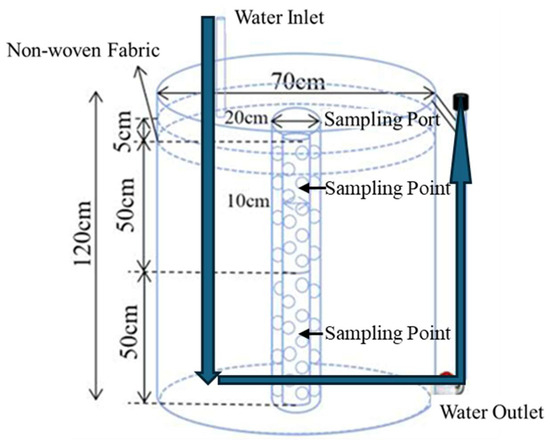

This study was conducted in 2023 at the Water Ecological Purification Experimental Base of Nanjing University, Hongze District, Jiangsu Province (118°55′ E, 33°19′ N). The watershed where the experimental base is located has an annual precipitation of 1080 mm and an average annual temperature of approximately 15 °C. A small-scale vertical flow constructed wetland experimental setup was established, which used a high-strength plastic barrel with a height of 120 cm, a diameter of 70 cm, and a volume of 320 L as the container. The water outlet was positioned 2 cm above the bottom of the barrel. A substrate sampling device was installed at the center of the barrel: it was composed of a nested structure that consisted of one reinforced plastic pipe (20 cm in diameter, 110 cm in height) and two reinforced plastic pipes (10 cm in diameter, 50 cm in height, with a cover at the bottom). Small holes with a diameter of 1.2 cm were evenly distributed around the reinforced plastic pipes (see Figure 1), and the inner 10 cm pipes were filled with the same substrate as that outside the pipes.

Figure 1.

Diagram of the pilot installation of vertical flow constructed wetland.

Three treatment groups were set up in the experiment, namely, the pure concrete aggregate treatment (Concrete), the treatment with 50 cm of concrete aggregates in the upper layer + 50 cm of perlite [17] in the lower layer (Concrete + Perlite), and the mixed treatment with 50% perlite and 50% concrete aggregates (Mixed). Each treatment group consisted of three independent experimental units. Iris pseudacorus was selected as the experimental aquatic plant. Seedlings of Iris pseudacorus with similar age, growth status, and a plant height of 30 cm were chosen. Withered leaves were cut off with sterilized scissors, and the seedlings were pre-cultured in pond water for 15 days before being transplanted on 18 May 2023. For the experiment, the particle size of perlite was 1–2 cm, and that of crushed concrete aggregates was 2–5 cm. The height of the main substrate layer was 1 m, and the plant base was composed of 5 cm-thick gravel (0.5–1 cm in particle size). A layer of non-woven fabric was placed between the plant base and the filling material to separate them. The small-scale setup operated for 5.5 months, including a 2.5-month start-up period and a 3-month operation period.

A continuous flow operation mode was adopted, with a hydraulic retention time (HRT) of 2 days. The influent water quality indicators were configured according to the standards of COD 50 mg/L, TP 0.5 mg/L, TN 15 mg/L, NH4+-N 5 mg/L, and NO3−-N 10 mg/L, which meet the Chinese Class 1A effluent standard [18]. The influent water was prepared by pumping nearby pond water and adding appropriate chemical reagents, with a large-scale water storage barrel (5 tons) used as the influent barrel. Specifically, glucose, potassium dihydrogen phosphate, potassium nitrate, and ammonium sulfate dodecahydrate were used to simulate the chemical oxygen demand (COD), total phosphorus (TP), nitrate nitrogen (NO3−-N), and ammonium nitrogen (NH4+-N) in the influent, respectively. All reagents with an analytical reagent (AR) purity grade were supplied by the Sinopharm Group. Before each water preparation, the main water quality parameters of the pond water were measured. The amounts of chemical reagents to be added were calculated based on the above water quality standards, ensuring that the influent water quality parameters were close to the set influent standards each time.

2.2. Sampling and Analysis

During the experimental operation phase, water samples were collected every 10 days to determine the main water quality parameters. Specifically, the contents of chemical oxygen demand (COD), total nitrogen (TN), nitrate nitrogen (NO3−-N), and nitrite nitrogen (NO2−-N) in the water were measured using HACH test kits (HACH-China, Shanghai, China), while the contents of total phosphorus (TP) and ammonium nitrogen (NH4+-N) were determined via Liangzi Chemical test kits (Liangzi Huagong, Nanjing, China). Digestion was performed using a HACH DRB200 digester (HACH-China, Shanghai, China), and colorimetry was conducted with a DR2800 spectrophotometer (HACH-China, Shanghai, China). For the determination of COD, NH4+-N, NO3−-N, NO2−-N, TN, and TP, the test kits adopted the potassium dichromate method, salicylic acid method, cadmium reduction method, N-(1-naphthyl)-ethylenediamine spectrophotometric method, potassium persulfate–ultraviolet spectrophotometric method, and potassium persulfate digestion–molybdenum antimony anti-spectrophotometric method, respectively. The experimental data were analyzed using IBM SPSS Statistics 27 (Version 27), and the resulting data were graphically presented using OriginLab OriginPro 2023 (Version 2023).

In the later stage of the experiment, substrate samples were collected from the substrate-sampling device. For the “Concrete + Perlite” treatment and the “Mixed” treatment, equal volumes of substrate samples were collected and mixed. During the collection, the substrate samples were temporarily stored in an insulated box that contained dry ice, and two portions of substrate were collected for each treatment group. After all the substrate samples were collected, pretreatment was carried out to harvest the biofilm: 100 mL of phosphate buffer solution was added to each substrate collection bag to submerge the substrate, followed by sonication with an ultrasonic oscillator at 25 °C and 100 Hz for 5 min. The sonicated turbid solution was filtered using a vacuum pump, and the biofilm was collected on a 0.22 μm filter membrane. The filter membrane was stored in a sterile centrifuge tube and temporarily kept in a dry ice insulated box. This process was repeated once, resulting in two filter membranes collected for each sample. The filter membranes were then sent to Shanghai Majorbio Bio-pharm Technology Co., Ltd. (http://www.majorbio.com/) for bacterial community structure analysis.

3. Results

3.1. Regulation of Effluent pH

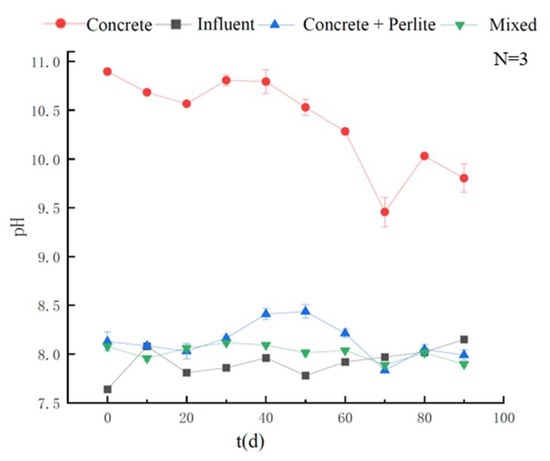

Over the 3-month experimental period, under the condition of near-neutral influent water (average pH = 7.9, pH fluctuation range: 7.6–8.2), the pH of the Concrete group (pure concrete aggregate treatment) fluctuated between 9.2 and 11.0, with an average value of 10.4; the pH of the “Concrete + Acidic Substrate” group (treatment with 50 cm of concrete aggregates in the upper layer + 50 cm of acidic substrate in the lower layer) varied within the range of 7.8–8.6, with an average of 8.1; and the pH of the Mixed group (treatment with 50% acidic substrate and 50% concrete aggregates mixed) fluctuated between 7.8 and 8.2, with an average of 8.0 (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

The influent and effluent pHs (n = 30) of constructed wetlands during the experiment period.

The results indicate that when waste concrete is used alone as a substrate in constructed wetlands, it leads to an excessively high effluent pH (i.e., exceeding the standard for surface water pH specified in GB 3838 [19], which stipulates that the pH of surface water shall not exceed 9.0). Even after 5 months of operation under the experimental conditions, the effluent pH of the Concrete group still exceeded 9.0. In contrast, the mixed use of acidic and alkaline substrates could resolve the issue of excessive effluent pH in the constructed wetlands. Both mixed application methods of acidic and alkaline substrates adopted in this experiment effectively addressed the problem of non-compliant effluent pH, and there was no significant difference between the two mixed methods.

3.2. Pollutant Removal

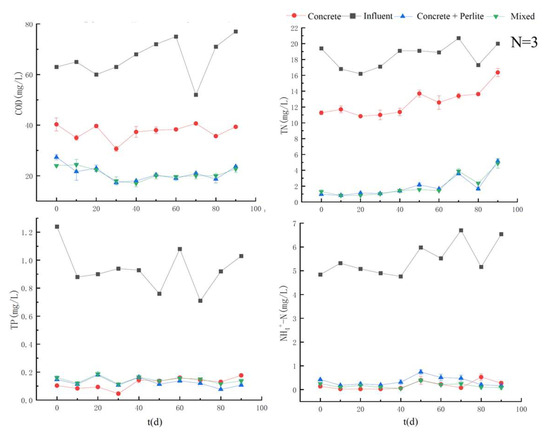

Compared with the influent, each treatment showed good removal effects on the COD, TN, TP, and NH4+-N during the experimental period. The average removal rates of the four pollutants by the three treatments were 60.3%, 70.2%, 86.1%, and 95.8%, respectively (see Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Pollutant concentrations in inlets and effluents of different treatments during the experimental period.

There were significant differences in the pollutant removal capacities of each treatment. The COD removal rates of the Concrete + Perlite group and the Mixed group were 68.5% and 68.8%, respectively, and the effluent COD concentration after the treatment was about 20 mg/L, reaching the Class II water standard; the COD removal rate of the Concrete group was only 43.7%, and the effluent COD concentration reached the Class V water standard [19]. The removal rates of both the Concrete + Perlite group and the Mixed group were significantly higher than that of the pure Concrete group (p < 0.001). The TN removal rates of the Concrete group, Concrete + Perlite group, and Mixed group were 31.8%, 89.3%, and 89.4%, respectively. The removal rates of both the Concrete + Perlite group and the Mixed group (effluent TN was about 2.0 mg/L, reaching the Class V water standard) were significantly higher than that of the pure Concrete group (effluent TN concentration was about 12 mg/L) (p < 0.001); the TP removal rates of the Concrete group, Concrete + Perlite group, and Mixed group were 87.0%, 86.5%, and 84.7%, respectively. The removal rates of the Concrete + Perlite group and the Mixed group were slightly lower than that of the pure Concrete group, and the effluent concentrations of all three reached the Class III water standard; the NH4+-N removal rates of the Concrete group, Concrete + Perlite group, and Mixed group were 96.7%, 93.7%, and 96.9%, respectively. The removal rates of the pure Concrete group and the Mixed group were slightly higher than those of the Concrete + Perlite group, and the effluent concentrations of all three reached the Class II water standard. The results show that compared with the pure Concrete group, the mixed use of acidic and alkaline substrates could significantly improve the removal effects of COD, TN, and NH4+-N; the mixed use of acidic and alkaline substrates only slightly reduced the removal effect of TP. Pure concrete exhibited relatively high TP removal capacity, while its chemical COD removal efficiency was relatively low, which is consistent with previous research findings [2,10].

3.3. Microbial Community Characteristics

There were significant differences in the biofilm bacterial diversity between different substrate treatments (p < 0.001) (Table 1). The bacterial diversity of the Concrete treatment was significantly lower than those of the Concrete + Perlite treatment and the Mixed treatment, while there was no significant difference between the Concrete + Perlite treatment and the Mixed treatment; compared with the Concrete + Perlite treatment and the Mixed treatment, the diversity indices Chao, Sobs, and Shannon of the Concrete treatment decreased by an average of 70.9%, 73.4%, and 59.2%, respectively, while the Simpson index increased by 260%.

Table 1.

Bacterial community diversity index of different substrate biofilms.

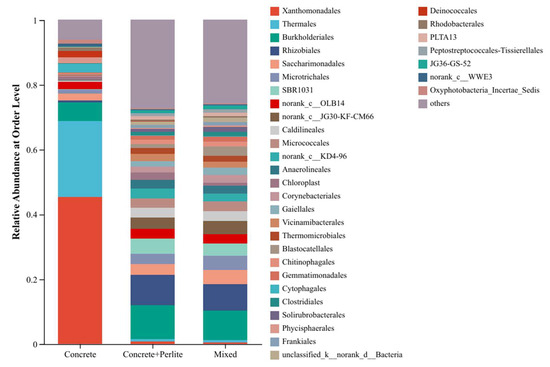

The analysis of bacterial community structure can further clarify the reasons why the biofilm bacterial diversity of the Concrete treatment was significantly lower than that of the other two treatments (see Figure 4 and Figure 5): at the phylum level, Proteobacteria and Deinococcota were the dominant flora in the Concrete treatment, which accounted for 54.8% and 25.5% respectively; the community structures of the Concrete + Perlite group and the Mixed group were similar, and the top three microorganisms in terms of abundance were Proteobacteria, Chloroflexi, and Actinobacteriota. At the order level, Xanthomonadales and Thermales occupied an absolute dominant position in the Concrete treatment, with relative abundances of 45.5% and 23.5% respectively, while Burkholderiales (third) and Cytophagales (fourth) had relative abundances of only 5.6% and 2.8%, respectively. In the Concrete + Perlite treatment, the top four in terms of relative abundance at the order level were Rhizobiales, Burkholderiales, Micrococcales, and Caldilineales, with 10.0%, 8.18%, 4.02%, and 3.88%, respectively. In the Mixed treatment, the top four in terms of relative abundance at the order level were Burkholderiales, Rhizobiales, Saccharimonadales, and Microtrichales, with 8.97%, 8.25%, 4.43%, and 4.43%, respectively.

Figure 4.

Bacterial community structures of substrate biofilms under different treatments at the later stage of the experiment (phylum level).

Figure 5.

Bacterial community structure of substrate biofilm under different treatments at the later stage of the experiment (order level).

The analysis of differences in the functional predictions based on the FAPROTAX database (Figure 6) showed that in groups with different substrate treatments, the carbon and nitrogen cycle functional groups of the constructed wetlands changed significantly. The abundances of microorganisms with chemoheterotrophic, photosynthetic autotrophic, nitrogen-fixing, nitrate-reducing, anaerobic ammonium oxidation, denitrifying, and ammoniating functions in the pure Concrete group were significantly lower than those in the Concrete + Perlite group and the Mixed group (p < 0.05). There was no significant difference in the abundance of chemoheterotrophic microorganisms between the acid–base Concrete + Perlite group and the Mixed group (p > 0.05).

Figure 6.

One-way ANOVA of the FAPROTAX-predicted function of the bacterial community. Note: *: p < 0.05; **: p < 0.01.

4. Discussion

In constructed wetlands, adsorption and precipitation are typically the most crucial pathways for total phosphorus (TP) removal. The results of this study revealed that the pure Concrete group achieved the highest TP removal rate, which can be attributed to two factors. On one hand, compared with perlite, concrete has a larger specific surface area and higher porosity, leading to superior TP adsorption performance [12]. On the other hand, the high pH of the pure Concrete group inhibits the leaching of Ca2+ from concrete, and the formation of Ca-P bonds on the substrate surface constitutes a key pathway for TP removal by concrete [11]. Consequently, the Concrete group exhibits a higher TP adsorption capacity. In contrast, the reduction in TP removal efficiency in the two combined groups (acidic–alkaline substrate combinations) relative to the pure Concrete group was minimal. This may be associated with the extremely high TP adsorption capacity of concrete—even after the concrete dosage was halved in the two combined groups, the TP adsorption capacity remained far from saturation by the end of the experiment [12].

Pollutant removal in constructed wetlands is highly dependent on the activities of microorganisms associated with the substrate [20]. Previous studies have indicated that the majority of microorganisms thrive in an environment with a pH ranging from 6 to 9 [21]. An excessively high environmental pH hinders the synthesis of ATPase, rendering microorganisms unable to survive; alkaline environments also promote intracellular alkalinization of microorganisms, making them more susceptible to death [22,23]. Throughout the experimental period, the pH of the Concrete group fluctuated between 9.2 and 11.0, with an average of 10.4, which resulted in a significant reduction in bacterial diversity [24]. Additionally, the “Concrete + Perlite” and Mixed groups, which benefited from the diverse habitats created by the mixed substrates, tended to exhibit increased biological diversity.

In this study, the microbial community structure of the pure Concrete group exhibited extreme distribution characteristics at all taxonomic levels. Alkaliphilic microorganisms, such as those belonging to the phylum Proteobacteria, dominated the Concrete group [25], while the proportion of non-alkali-tolerant microorganisms was relatively extremely low. According to research by Cao et al. [6], the microbial community structure is strongly influenced by the pH, which acts as a driving factor that determines the microbial community structure across large spatial scales. In constructed wetlands, microbial degradation and microbially mediated nitrogen cycling are generally the primary pathways for the removal of chemical oxygen demand (COD), TN, and ammonium nitrogen (NH4+-N) [26]. Relevant studies have also demonstrated that when the pH exceeds 9.0, the activity of microorganisms involved in COD degradation and nitrogen cycling is often significantly inhibited [27,28]. This explains why the mixed use of acidic and alkaline substrates enhanced the removal efficiency of COD, TN, and NH4+-N compared with the pure Concrete group—this improvement is likely associated with the pH regulation achieved by the mixed substrate system. In the microbial community structure analysis, the orders Rhizobiales and Burkholderiales, which were the most abundant in the Mixed and “Concrete + Perlite” groups, were capable of participating in aerobic denitrification and heterotrophic ammonia oxidation, which contributed to the decomposition and removal of both COD and ammonia nitrogen. Their degradation efficiency begins to decline when pH > 8.0 [29]. This confirms that the relative abundance of Rhizobiales and Burkholderiales decreased in the high-pH Concrete group, which may be a key factor that led to the lower pollutant removal rates in this group. For NH4+-N removal, NH4+-N primarily exists in an ionized form under alkaline conditions, which is relatively stable and difficult to remove—this further reduced the NH4+-N removal rate in the pure Concrete group [30].

As previously noted, most microorganisms thrive in environments with a pH between 6 and 9 [21]. Excessively high pH disrupts ATPase synthesis, preventing microbial survival, and alkaline conditions induce intracellular alkalinization, increasing microbial mortality [22,23]. During the experiment, the Concrete group’s pH fluctuated between 9.2 and 11.0 (average: 10.4), which significantly reduced the bacterial diversity [24]. Moreover, the “Concrete + Perlite” and Mixed groups, with diverse habitats derived from mixed substrates, facilitated increased biological diversity.

Functional prediction via FAPROTAX in this study revealed that chemoheterotrophy had the highest abundance among all ecological functions. Chemoheterotrophic microorganisms are key decomposers in ecosystems and play an extremely important role in the cycling of organic carbon (C) and nitrogen (N) [31].

The abundance of chemoheterotrophic microbial functions in the Concrete group was lower than that in the “Concrete + Perlite” group and the Mixed group. This aspect also explains why the COD (chemical oxygen demand) removal rate of the Concrete group was significantly lower than that of the “Concrete + Perlite” group and the Mixed group.

Additionally, the abundance of microbial functions involved in fermentation, nitrogen fixation, and nitrogen respiration in the Concrete group was significantly lower than that in the “Concrete + Perlite“ group and the Mixed group, which also resulted in the poor TN (total nitrogen) removal performance of the Concrete group.

This study has certain limitations. The findings derived from the laboratory-scale pilot experiments may not fully represent the conditions of full-scale constructed wetlands, and seasonal variations (e.g., temperature, light) were not systematically evaluated. Nevertheless, this research addresses potential environmental risks (high pH) associated with using construction and demolition waste as a substrate in constructed wetlands, thereby offering a viable approach for overall cost reduction in constructed wetland implementation. Consequently, the proposed technology demonstrates strong practical applicability for real-world engineering applications.

5. Conclusions

The sole use of waste concrete as a substrate in constructed wetlands leads to the issue of excessively high effluent pH. Under the experimental condition of a 2-day hydraulic retention time (HRT), the effluent pH remained above 9.0, even after 5 months of operation, indicating that the resource utilization of waste concrete as a constructed wetland substrate carries potential ecological risks. However, the mixed application of acidic and alkaline substrates can resolve the problem of non-compliant effluent pH in constructed wetlands, and there was no significant difference between the two configuration modes of acidic–alkaline substrates adopted in this experiment.

Compared with the pure Concrete group, the mixed use of acidic and alkaline substrates significantly improved the removal efficiencies of the chemical oxygen demand (COD), total nitrogen (TN), and ammonium nitrogen (NH4+-N) in the constructed wetlands, and only caused a slight reduction in the total phosphorus (TP) removal efficiency.

In comparison with the constructed wetlands using a pure concrete substrate, the mixed application of perlite (acidic substrate) and concrete (alkaline substrate) significantly enhanced the bacterial community diversity and functional diversity of the substrate-attached biofilm. Additionally, the difference between the two configuration modes of acidic–alkaline substrates in this experiment was relatively small.

The combined use of acidic substrates with waste concrete is an effective strategy to address the problem of excessively high effluent pH in constructed wetlands utilizing waste concrete. Specifically, formulating pH-balanced substrates through the configuration of acidic and alkaline materials constitutes an efficient approach for developing construction and demolition waste (CDW) into constructed wetland substrates. Compared with existing CDW resource utilization methods (e.g., road-filling materials), the development of CDW as a constructed wetland substrate represents a resource utilization approach with higher economic value.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.C.; methodology, Y.G.; software, Y.W.; analysis, Y.G.; data curation, Y.G.; writing—review and editing, R.Z.; supervision, D.Z.; project administration, D.Z.; funding acquisition, M.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Research and Development Project of Jiangsu Environmental Engineering Technology Co., Ltd. (No. JSEP-GJ20220011-RE-ZL), and Cooperation with Local Governments Project of the Chinese Academy of Engineering (No.: JS2025XZ05).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this study, the authors used the Majorbio Cloud platform (https://cloud.majorbio.com) for the purposes of bioinformatic analysis. The authors declare that this study received funding from Research and Development Project of Jiangsu Environmental Engineering Technology Co., Ltd. (No. JSEP-GJ20220011-RE-ZL). The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

Authors Ying Cai, Miao Zhang, and Ying Wei were employed by the company Jiangsu Environmental Engineering Technology Co., Ltd. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CDW | Construction and demolition waste |

| COD | Chemical oxygen demand |

| NH4+-N | Ammonium nitrogen |

| pH | Potential of hydrogen |

| TN | Total nitrogen |

| TP | Total phosphorus |

References

- Ji, Z.H.; Tang, W.Z.; Pei, Y.S. Constructed wetland substrates: A review on development, function mechanisms, and application in contaminants removal. Chemosphere 2022, 286, 131564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.Y.; Zhang, Y.H.; Wu, L.Y.; Jin, Y.; Gong, Y.W.; Li, A.Z.; Li, J.X.; Li, F. Recycled aggregates from construction and demolition waste as wetland substrates for pollutant removal. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 311, 127766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotsia, D.; Sympikou, T.; Topi, E.; Pappa, F.; Matsoukas, C.; Fountoulakis, M.S. Use of recycled construction and demolition waste as substrate in constructed wetlands for the wastewater treatment of cheese production. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 362, 121324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.F.; Zhu, J.Z.; Gu, X.J.; Zhu, J.J. Current Situation and Control of Agricultural Non-point Source Pollution. China Popul. Resour. Environ. 2010, 20, 81–84. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, Z.; Ding, Z.; Zha, X.; Cheng, T.; Ding, Z.; Zha, X.; Cheng, T. Phosphorus Adsorption Characteristics of Different Substrates in Constructed Wetland. China Water Wastewater 2009, 25, 80–82. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, H.; Chen, R.; Wang, L.; Jiang, L.; Yang, F.; Zheng, S.; Wang, G.; Lin, X. Soil pH, total phosphorus, climate and distance are the major factors influencing microbial activity at a regional spatial scale. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 25815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tam, V.; Gao, X.F.; Tam, C.M.; Ng, K.M. Physio-chemical reactions in recycle aggregate concrete. J. Hazard. Mater. 2009, 163, 823–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hube, S.; Zaqout, T.; Ogmundarson, O.; Andradottir, H.O.; Wu, B. Constructed wetlands with recycled concrete for wastewater treatment in cold climate: Performance and life cycle assessment. Sci. Total. Environ. 2023, 904, 166778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.S.; Zhu, H.Z.; Wu, K.M.; Zhao, X.H.; Wang, F.; Liao, Q.L. Fines isolated from waste concrete as a new material for the treatment of phosphorus wastewater. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2020, 27, 12539–12549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abd Roni, N.; Adnan, S.H.; Hamidon, N.; Ismail, T. The vertical recycled concrete aggregate filter for removal of phosphorus in wastewater. In 3rd International Conference on Civil and Environmental Engineering; Izhar, T., Ibrahim, N., Dahalan, F.A., Saad, F., Ghani, A.A., Ibrahim, N.M., Yusof, S.Y., Bawadi, N.F., AnudaiAnuar, S., Eds.; Science Publishing Group: New York, NY, USA, 2021; Volume 646. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Q.M.; Ma, Y.; Chen, J.; Cai, Y.; Lu, Q.Q.; Yu, Q.; Duan, X.T.; Zhao, D.H.; An, S.Q. The negative effect of the high pH of waste concrete in constructed wetlands on COD and N removal. J. Water Process. Eng. 2023, 51, 103356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.J.; Wang, J.P.; Lin, X.C.; Wang, H.; Li, H.E.; Li, J.K. Purification effects of recycled aggregates from construction waste as constructed wetland filler. J. Water Process. Eng. 2022, 50, 103335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staunton, J.; Williams, C.D.; Morrison, L.; Henry, T.; Fleming, G.; Gormally, M.J. Spatio-temporal distribution of construction and demolition (C&D) waste disposal on wetlands: A case study. Land Use Policy 2015, 49, 43–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saavedra, R.; Etxeberria, M. Carbonation Treatments for Durable Low-Carbon Recycled Aggregate Concrete. Materials 2025, 18, 4168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S.J.; Yin, J.; Xu, W.X.; Liu, S.Z.; Liu, X.F. Alkalinity Regulation and Optimization of Cementitious Materials Used in Ecological Porous Concrete. Materials 2024, 17, 1918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Radevic, A.; Despotovic, I.; Zakic, D.; Oreskovic, M.; Jevtic, D. Influence of acid treatment and carbonation on the properties of recycled concrete aggregate. Chem. Ind. Chem. Eng. Q. 2018, 24, 23–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fetene, Y.; Addis, T. Adsorptive Removal of Phosphate From Wastewater Using Ethiopian Rift Pumice: Batch Experiment. Air Soil Water Res. 2020, 13, 1178622120969658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB 18918-2002; Discharge Standard of Pollutants for Municipal Wastewater Treatment Plant. Ministry of Ecology and Environment: Beijing, China, 2002.

- GB 3838-2002; Environmental Quality Standards for Surface Water. Ministry of Ecology and Environment: Beijing, China, 2002.

- Ding, J.; Shu, Q. Application of Constructed Wetlands for Wastewater Treatment. J. Agro-Environ. Sci. 2000, 5, 320–321. [Google Scholar]

- Bárcenas-Moreno, G.; Bååth, E.; Rousk, J. Functional implications of the pH-trait distribution of the microbial community in a re-inoculation experiment across a pH gradient. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2016, 93, 69–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhakar, K.; Pandey, A. Wide pH range tolerance in extremophiles: Towards understanding an important phenomenon for future biotechnology. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2016, 100, 2499–2510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voskuil, M.I.; Covey, C.R.; Walter, N.D. Antibiotic Lethality and Membrane Bioenergetics. Adv. Microb. Physiol. 2018, 73, 77–122. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, Q.; Wang, Q.-Q.; Wu, L.; Cai, A.-D.; Wang, C.-J.; Zhang, W.-J.; Xu, M.-G. Fertilization impacts on soil microbial communities and enzyme activities across China’s croplands: A meta-analysis. J. Plant Nutr. Fertil. 2018, 24, 1598–1609. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, D.; Zhao, Y.G.; Ma, R.; Yang, P.; Zhang, C.; Zhou, D.J.; Sun, F.J.; Zhang, F.H. Effects of Microbial Fertilizers on Soil Improvement and Bacterial Communities in Saline-alkali Soils of Lycium barbarum. J. Agric. Biotechnol. 2020, 28, 1499–1510. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, J.; Hu, X.B.; Chen, M.L.; Zhang, J.M.; Guo, F.C.; Vymazal, J.; Chen, Y. Meta-analysis of the removal of trace organic contaminants from constructed wetlands: Conditions, parameters, and mechanisms. Ecol. Eng. 2022, 178, 106596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, T.; Zhang, L.; Quan, X.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, F. Study on Adsorption and Bio-degradability of Aged-refuse-based Bioreactor. Environ. Eng. 2007, 6, 34–36. [Google Scholar]

- Zhengwei, L.; Xishu, H.; Xuan, C.; Yongtao, L.; Xudong, W. Effect of pH values on shortcut denitrification and nitrous oxide emission. J. Xi’an Univ. Archit. Technol. 2019, 51, 605–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, D.R.; Zhang, Y.; Gao, Y.X.; Liu, Y.; Yang, M. Biotransformation of nitrogen- and sulfur-containing pollutants during coking wastewater treatment: Correspondence of performance to microbial community functional structure. Water Res. 2017, 121, 338–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albina, P.; Durban, N.; Bertron, A.; Albrecht, A.; Robinet, J.C.; Erable, B. Influence of Hydrogen Electron Donor, Alkaline pH, and High Nitrate Concentrations on Microbial Denitrification: A Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 5163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, S.S.; Hu, Q.L.; Cheng, Y.Q.; Bai, L.Y.; Liu, Z.H.; Xiao, W.J.; Gong, Z.H.; Wu, Y.N.; Feng, K.; Deng, Y.; et al. Application of organic fertilizer improves microbial community diversity and alters microbial network structure in tea (Camellia sinensis) plantation soils. Soil Tillage Res. 2019, 195, 104356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.