A New Methodological Framework for the Determination of Water Resource Classes and Resource Quality Objectives: A Case Study for the Mzimvubu to Tsitsikamma Water Management Area 7 (WMA7)

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area Description

2.2. Methodology

- (i)

- Delineation of Integrated Units of Analysis and priority Resource Units

- (ii)

- Identification of driving water quality variables for water quality changes in the study area

- (iii)

- Identification and evaluation of water resource scenarios

- (iv)

- Determination of water resource classes

- (v)

- Determination of Resource Quality Objectives

2.3. Conceptualization of Resource Directed Measures

3. Results and Discussion

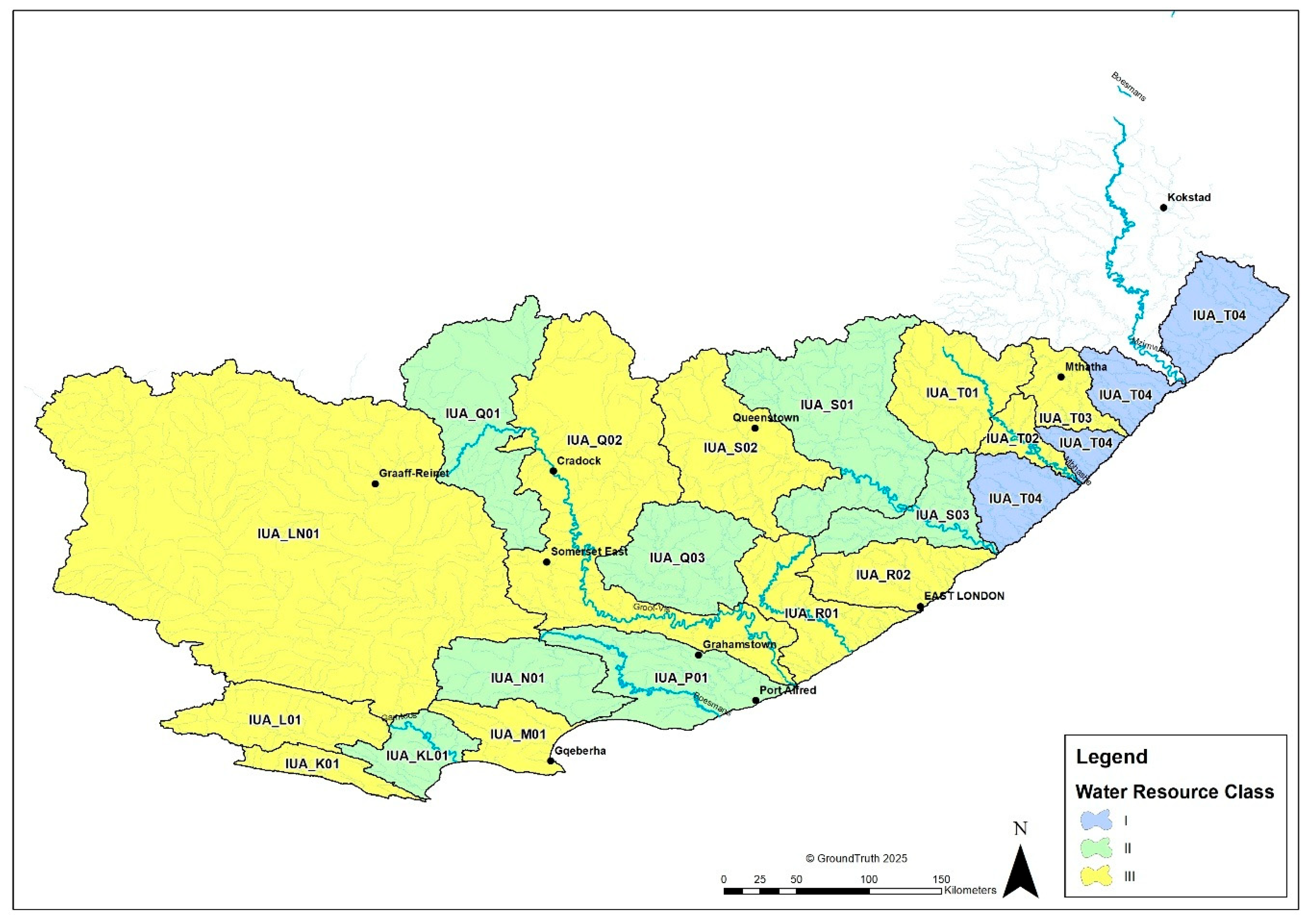

3.1. Delineated Integrated Units of Analysis and Priority Resource Units Within the WMA7

3.2. Identification of Driving Water Quality Variables for Water Quality Changes Within the Integrated Units of Analysis

3.3. Identification and Evaluation of Water Resource Scenarios

3.3.1. Identified Water Resource Scenarios in the Study Area

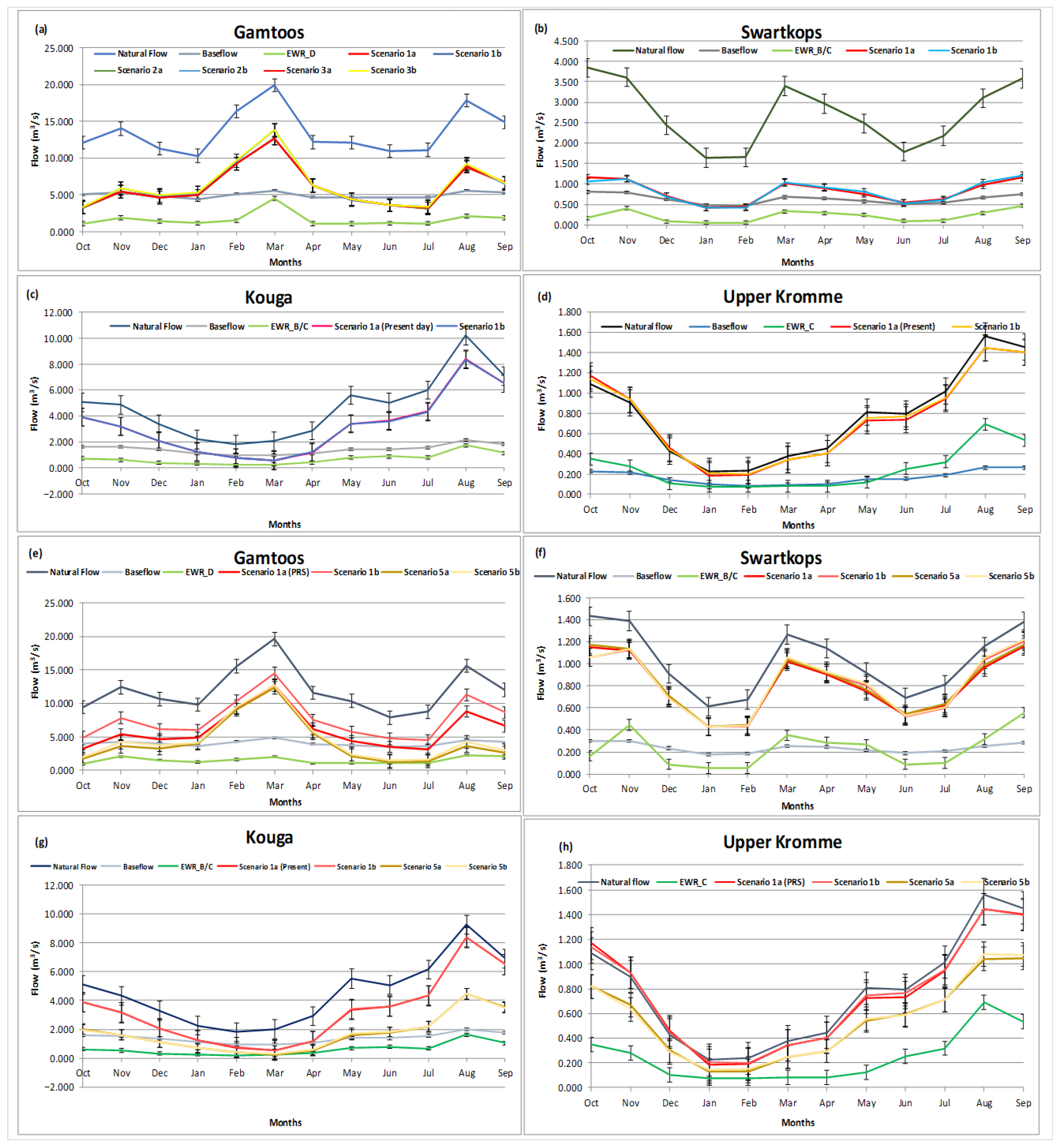

3.3.2. Evaluation of Water Resource Scenarios in the WMA7

3.4. Determination of Water Resources Classes per IUA and Resource Quality Objectives per RU

3.4.1. Determination Water Resources Classes per IUA

3.4.2. Setting of Resource Quality Objectives per RU

4. Conclusions

- Nineteen Integrated Units of Analysis were delineated, and ninety-five Resource Units were identified and prioritized for both surface and groundwater, which provided key insights into areas where stricter measures will be established to safeguard these critical resources.

- Driving water quality variables (nutrients, EC, and E. coli) were observed, and primary water users (irrigation, settlements, and WWTWs) were identified per IUA in the study area.

- Five water resource scenarios were designed and evaluated to capture a likely water resource condition for the present and future. The analysis showed that impact is expected under any of the operational scenarios assessed at the selected reaches. However, the climate change scenarios (Sc5a and Sc5b) showed significant variability in the Upper Kromme, Swartkop, Kouga, and Gamtoos systems.

- The water resource classes were determined, of which eleven IUAs were classified to be in Class lll, seven IUAs in Class ll, and one IUA in Class l. This necessitates more stringent management measures to improve resource conditions in the study area.

- Water quality and quantity Resource Quality Objectives were set to ensure that both river and groundwater resources are compliant and protected, while allowing socio-economic development in the study area.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| DWS | Department of Water and Sanitation |

| EC | Ecological category |

| EWR | Ecological Water Requirements |

| GRU | Groundwater Resource Units |

| GDP | Gross Domestic Products |

| IUA | Integrated Units of Analysis |

| RDM | Resource Directed Measures |

| REC | Recommended Ecological Category |

| RQO | Resource Quality Objectives |

| NWA | National Water Act |

| PES | Present Ecological State |

| PES/EIS | Present Ecological State/Ecological Importance and Sensitivity |

| WMA | Water Management Area |

| WRC | Water Research Commission |

| WRCS | Water Resource Classification System |

| WWTW | Wastewater Treatment Works |

References

- Makanda, K.; Nzama, S.; Kanyerere, T. Assessing the Role of Water Resources Protection Practice for Sustainable Water Resources Management: A Review. Water 2022, 14, 3153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Wildlife Fund (WWF). Post-2020 Global Biodiversity Framework Synergies; World Wildlife Fund (WWF): Nairobi, Kenya, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Gassert, F.; Reig, P.; Luo, T.; Maddocks, A. Aqueduct Country and River Basin Rankings: A Weighted Aggregation of Spatially Distinct Hydrological Indicators; Working Paper; World Resources Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Pienaar, H.; Xu, Y.; Braune, E.J.; Cao, J.; Dzikiti, S.; Jovanovic, N.Z. Implementation of groundwater protection measures, particularly resource directed measures in South Africa: A review paper. Smart Places Cluster, Council for Scientific and Industrial Research, Pretoria, South Africa. Water Policy 2021, 23, 819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makanda, K.; Nzama, S.; Kanyerere, T. Putting water resource protection into practice: A decision support system to assess compliance with predefined protection limits for water resources in developing countries. J. Hydrol. Reg. Stud. 2025, 60, 102538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Republic of South Africa, National Water Act (NWA). Government Gazette No. 39299; Government Printer: Cape Town, South Africa, 1998; p. 36.

- Department of Water and Sanitation, South Africa. National Water Resource Strategy 2; Department of Water and Sanitation: Pretoria, South Africa, 2013.

- Nkosi, M.; Mathivha, F.I.; Odiyo, J.O. Impact of Land Management on Water Resources, a South African Context. Sustainability 2021, 13, 701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Department of Water Affairs, South Africa. Procedure to Develop and Implement Resource Quality Objectives; Department of Water Affairs: Pretoria, South Africa, 2011.

- WRC. Water Resource Protection: Research Report a Review of the State-of-the-Art and Research and Development Needs for South Africa; WRC Report No. 2532/1/17; Riemann, K., McGibbon, D.C., Gerstner, K., Scheibert, S., Hoosain, M., Hay, E.R., Eds.; Umvoto Africa (Pty) Ltd.: Cape Town, South Africa, 2017; ISBN 978-1-4312-0879-1. [Google Scholar]

- Mulangaphuma, L.H.; Odusanya, D.; Jovanovic, N. Evaluation of River and Groundwater Quality in the Mzimvubu to Tsitsikamma Water Management Area (WMA7). Water 2024, 16, 1654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulangaphuma, L.; Jovanovic, N. Investigation of Water Use and Trends in South Africa: A Case Study for the Mzimvubu to TsitsikammaWater Management Area 7 (WMA7). Water 2025, 17, 1522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Department of Water and Sanitation, South Africa. Determination of Water Resource Classes, Reserve and RQOs in the Keiskamma and Fish to Tsitsikamma Catchment: Status quo and Delineation of Integrated Units of Analysis Report; Report No: WEM/WMA7/00/CON/RDM/0322; Department of Water and Sanitation: Pretoria, South Africa, 2022.

- UNDP-GEF. UNDP-GEF Orange-Senqu Strategic Action Programme (Atlas Project ID 71598) Delineation of Management Resource Units Research Project on Environmental Flow Requirements of the Fish River and the Orange-Senqu River Mouth; Technical Report 22 Rev 0; UNDP-GEF: Washington, DC, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- DWAF. South African Water Quality Guidelines (Volume 1), Domestic Uses, 2nd ed.; Department of Water Affairs & Forestry: Pretoria, South Africa, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- DWAF. South African Water Quality Guidelines (Volume 7), Aquatic Ecosystems, 1st ed.; Department of Water Affairs & Forestry: Pretoria, South Africa, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Water Affairs and Forestry (DWAF). Water Quality Sampling Manual for the Aquatic Environment; Institute for Water Quality Studies (IWQS): Pretoria, South Africa, 1997.

- Nzama, S.M.; Kanyerere, T.O.B.; Mapoma, H.W.T. Using Groundwater Quality Index and Value Duration Curves for Classification and Protection of Groundwater Resources: Relevance of Groundwater Quality of Reserve Determination; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WRC. Groundwater Resource Directed Measure Manual; WRC Project: K8/891; WRC: Pretoria, South Africa, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- DWS. A Desktop Assessment of the Present Ecological State, Ecological Importance and Ecological Sensitivity per Sub Quaternary Reaches for Secondary Catchments in South Africa. Compiled by RQIS-RDM. 2014. Available online: https://www.dws.gov.za/iwqs/rhp/eco/peseismodel.aspx (accessed on 25 September 2025).

- Department of Water and Sanitation, South Africa. Development of Procedures to Operationalise Resource Directed Measures; Main Report, Report No. RDM/WE/00/CON/ORDM/0117; Department of Water and Sanitation: Pretoria, South Africa, 2017.

- WRC. Water Resources of South Africa, 2012 Study (WR2012); WRC Project No. K5/2143/1; WRC: Pretoria, South Africa, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Water and Sanitation, South Africa. Amathole WSS Water Allocations, Water Requirements and Return Flows Report; Department of Water and Sanitation: Pretoria, South Africa, 2023.

- Kleynhans, C.J.; Louw, M.D.; Thirion, C.; Rossouw, N.J.; Rowntree, K. River EcoClassification: Manual for EcoStatus Determination (Version 1); Joint Water Research Commission and Department of Water Affairs and Forestry Report; WRC Report No. KV 168/05; WRC: Pretoria, South Africa, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Water and Sanitation (DWS), South Africa. Determination of Water Resource Classes and Resource Quality Objectives for Water Resources in the Mzimvubu Catchment; Wetlands and Groundwater RQO Report; Report no. WE/WMA7/00/CON/CLA/0318; Department of Water and Sanitation: Pretoria, South Africa, 2018.

- Department of Water Affairs and Forestry (DWAF). Manual for the Classification of Water Resources in South Africa: Water Resource Classification System (WRCS); Department of Water Affairs and Forestry (DWAF): Pretoria, South Africa, 2007.

- Water Resources of South Africa Study, WR2012. 2012. Available online: http://waterresourceswr2012.co.za/resource-centre/ (accessed on 15 September 2025).

- Palmer, C.G.; Muller, W.J.; Gordon, A.K.; Scherman, P.A.; Davies-Coleman, H.D.; Pakhomova, L.; de Kock, E. 2004b0 the development of a toxicity database using freshwater macroinvertebrates, and its application to the protection of the south African water resources. S. Afr. J. Sci. 2004, 100, 643–650. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Water and Sanitation, South Africa. Determination of Water Resource Classes, Reserve and RQOs in the Keiskamma and Fish to Tsitsikamma Catchment: Resource Quality Objectives; Numerical Limits and Confidence Report No: WEM/WMA7/00/CON/RDM/2825; Department of Water and Sanitation: Pretoria, South Africa, 2025.

- Department of Water and Sanitation. Green Drop Watch Report; Department of Water and Sanitation: Pretoria, South Africa, 2024.

- Department of Water and Sanitation, South Africa. Determination of Water Resource Classes, Reserve and RQOs in the Keiskamma and Fish to Tsitsikamma Catchment: Ecological Water Requirements Quantification for Rivers Report; Report No. WEM/WMA7/00/CON/RDM/1923; Department of Water and Sanitation: Pretoria, South Africa, 2023.

- Munzhelele, H.E.; Barnhoorn, I.E.J.; Addo-Bediako, A.; Ramulifho, P.A.; Luus-Powell, W.J. Impact of weirs in altering benthic macroinvertebrate assemblages and composition structure in the Luvuvhu River Catchment, South Africa. Front. Environ. Sci. 2024, 12, 1308227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Class and Description | Percentage (%) of Sub-Quaternary Reaches in the IUA Falling Into the Indicated Ecological Category Groups | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ≥A/B | ≥B | ≥C | ≥D | >D | ||

| I: Minimally used and distribution of Ecological Category of that water resource minimally altered from its pre-development conditions | 0 | 60 | 80 | 95 | 5- | |

| II: Moderately used and distribution of Ecological Category of that water resource moderately altered from its pre-development conditions | 0 | 70 | 90 | 10 | ||

| III: Heavily used and distribution of Ecological Category of that water resource significantly altered from its pre-development conditions | Either | 0 | 80 | 20 | ||

| Or | 100 | - | ||||

| IUA Code | Resource Unit | Water Quality Impact (Rating) | Water Quality Sources/Users | Driving Variables | Comment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IUA_K01 | R_RU02_I | 3 | Wastewater Treatment Works, Irrigation, Cattle farming | E. coli, Electrical conductivity, Nutrients | Upstream towns and villages. |

| R_RU01_I | 3 | Irrigation | Nutrients, Electrical conductivity | Dominated by citrus farming. | |

| IUA_L01 | R_RU05_I | 3 | Wastewater Treatment Works, Irrigation, Cattle farming | Nutrients (High Algae Content) | Dominated by cattle farming. |

| IUA_M01 | R_RU03_I | 3 | Industry, Cattle farming | Electrical Conductivity, Nutrients | Downstream of the Groendal Dam. Limited impacts due to conservation area. |

| IUA_LN01 | R_RU04_I | 3 | Irrigation and cattle farming | Nutrients | Elevated nutrient load. |

| IUA_Q02 | R_RU08_I | 3 | Human settlement, Sediment mining, Erosion, Irrigation | Total Dissolved Solids, Salinity | High sedimentation (highly turbid) from erosion and settlement. |

| R_RU06_I | 3 | Upstream Town | Clarity, Total Dissolved Solids, Salinity | High sedimentation. Cradock Town is located upstream. | |

| R_RU26_R | 3 | Cattle trampling and grazing | Nutrients | Extensive bank erosion. | |

| IUA_R01 | R_RU0_12 | 3 | Irrigation | Electrical conductivity, Nutrients, pH | Upstream Tois River contributes to the sediment loads. |

| R_RU10_I | 3 | Wastewater Treatment Works, Human settlement | E. coli, Nutrients, Total Dissolved Solids | Nutrients (algae) mainly from wastewater treatment works pipeline leakage downstream. | |

| R_RU09_I | 3 | Wastewater Treatment Works, Bank erosion, sand mining | E. coli, Clarity, Nutrients | High silt loads during higher flows; Deposition of sand on the lower flood features. | |

| IUA_R02 | R_RU13_I | 3 | Irrigation | Electrical conductivity, NH4 | Elevated nutrient load. |

| R_RU20_R | 4 | Wastewater Treatment Works | Nutrients, E. coli | Point sources posing health hazards to both humans and the environment. | |

| IUA_S02 | R_RU24_R | 3 | Irrigation, Wastewater Treatment Works, abstraction | Nutrients, E. coli, Chemical Oxygen | Nutrient enrichment (algae). Evidence of bank collapse and bank erosion due to flood event. |

| IUA_T01 | R_RU17_I | 3 | Wastewater Treatment Works, Human Settlement | E. coli, Nutrients | Nutrient enrichment (algae). |

| IUA_T02 | R_RU14_I | 3 | Human settlement, Sediment mining, Erosion | Electrical conductivity, Salinity, Clarity | Erosion and deposition along the channel margins. |

| IUA_T03 | R_RU15_I | 4 | Wastewater Treatment Works, Cattle trampling and Grazing | E. coli, Nutrients, Clarity | Algae and fine silt layer over stone biotope, erosion from cattle grazing. |

| Scenario | Scenario Descriptions | |

|---|---|---|

| Scenario 1 (Sc1) | Present Day Demands |

|

| ||

| Scenario 2 (Sc2) | Medium Term (2030) |

|

| ||

| Scenario 3 (Sc3) | Long Term (2050) |

|

| ||

| Scenario 4 (Sc4) | Water Quality (Considered and Predicted) |

|

| Scenario 5 (Sc5) | Climate Change (Considered and Predicted) |

|

| Scenario | Scenario Description | Reason for Selection |

|---|---|---|

| Scenario 1b | Present-Day Demands (With EWR) | To ensure flow of water in the system for the survival of flow dependent fish and macroinvertebrates. |

| Scenario 2b | Mid-Term (With EWR) | To ensure flow of water in the system is maintained and improved for sustainable water use. |

| Scenario 4 | Water Quality Scenario | To ensure that present and future water quality condition is improved for the ecosystem and water users |

| IUA | Class | REC | Component | Sub- Component | Indicator | RQO | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Narrative | Numeric | ||||||

| * IUA_K01 | iii | C | Quantity | Flows | High | Freshets and floods required for the upper Kromme River | 4.16 m3/s |

| Low | 0.16 m3/s | ||||||

| Quality | Salts | EC | _ | ≤55 mS/m | |||

| Nutrients | TIN | _ | ≤0.75 mg/L | ||||

| PO4-P | _ | <0.015 mg/L | |||||

| System variables | DO | _ | >7 mg/L | ||||

| pH | _ | 5th Percentile: 6.00–6.24; 95th Percentile: 8.37–8.69 | |||||

| Pathogens | Fecal coliforms and E. coli | _ | Meet targets for use in Table 6 detailing high health risk guidelines | ||||

| * IUA_KL01 | ii | B | Quantity | Flows | High | Continuous flows required at the Kouga River | 8.5 m3/s |

| Low | 0.34 m3/s | ||||||

| Quality | Salts | EC | _ | ≤55 mS/m | |||

| System variables | DO | _ | >7 mg/L | ||||

| pH | _ | 5th Percentile: 6.00–6.24; 95th Percentile: 8.37–8.69 | |||||

| C | Quantity | Flows | High | Continuous flows required at the river | 9.3 m3/s | ||

| Low | 0.49 m3/s | ||||||

| Quality | Salts | EC | _ | <85 mS/m | |||

| Nutrients | TIN | _ | <4 mg/L | ||||

| PO4-P | _ | <0.125 mg/L | |||||

| System variables | Water temperature | Natural temperature range is estimated from air temperature | _ | ||||

| TSS | _ | <10% of the background TSS concentrations at a specific site and time. TSS ≤ 117.0 mg/L | |||||

| * IUA_T04 | Class I | B | Quantity | Flows | High | _ | 0.038 m3/s |

| Low | _ | 0.016 m3/s | |||||

| Quality | Salts | EC | _ | ≤85 mS/m | |||

| Nutrients | TIN | _ | ≤2.0 mg/L | ||||

| PO4-P | _ | <0.025 mg/L | |||||

| System variables | DO | _ | >6 mg/L | ||||

| pH | _ | 5th Percentile: 5.00–5.23 95th Percentile: 9.05–9.36 | |||||

| Clarity | Aim for clarity to be approximately ≥95 cm | ≥95 cm | |||||

| B | Quantity | Flows | High | _ | 0.465 m3/s | ||

| Low | _ | 0.201 m3/s | |||||

| Quality | Salts | EC | _ | ≤55 mS/m | |||

| Nutrients | TIN | _ | ≤0.75 mg/L | ||||

| PO4-P | _ | <0.015 mg/L | |||||

| System variables | DO | _ | >7 mg/L | ||||

| pH | _ | 5th Percentile: 6.00–6.24 95th Percentile: 8.37–8.69 | |||||

| Clarity | Use on-site observations and expert opinion. | ≥81 cm | |||||

| IUA | Component | Sub- Component | Indicator | RQO | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Narrative | Numeric Limit | ||||

| * IUA_K01 | Quantity | Abstraction | Allocation | New users are to remain within the allocable groundwater volume. | - |

| Groundwater level | Time series | Drawdown in monitoring boreholes should not exceed peak drawdown. | Peak drawdown < 16.2 m 75th percentile drawdown < 10.2 m | ||

| Quality | Nutrients | NO3/NO2 | Trend should not exceed the 75th percentile or the TWQR for domestic use (in brackets) if higher for Compounds of Concern. | <1.4 | |

| Salt | EC | <74 mS/m (70) | |||

| SO4 | <16 mg/L (200) | ||||

| Na | <104 mg/L (100) | ||||

| Cl | <165 mg/L (100) | ||||

| F | <0.2 mg/L (1) | ||||

| * IUA_KL01 | Quantity | Abstraction | Allocation | Existing users to comply with allocation schedules. | - |

| Groundwater level | Monthly time series | _ | Peak drawdown < 13.4 m 75th percentile drawdown < 8.5 m | ||

| Quality | Nutrients | NO3/NO2 | Trend should not exceed the 75th percentile or the TWQR for domestic use (in brackets) if higher for Compounds of Concern. | <0.1 mg/L | |

| Salt | EC | <109 mS/m (70) | |||

| SO4 | <48 mg/L (200) | ||||

| Na | <89 mg/L (100) | ||||

| Cl | <200 mg/L (100) | ||||

| * IUA_L01 | Quantity | Abstraction | Allocation | New and existing water users to comply with allocation condition. | _ |

| Groundwater level | Time series | Identify suitable monitoring borehole. | _ | ||

| Quality | Nutrients | NO3/NO2 | Trend should not exceed the 75th percentile or the TWQR for domestic use (in brackets) if higher for Compounds of Concern. | <0.4 mg/L | |

| Salt | EC | <21 mS/m (70) | |||

| SO4 | <5 mg/L (200) | ||||

| Na | <25 mg/L (100) | ||||

| Cl | <47 mg/L (100) | ||||

| F | < 0.1 mg/L (1) | ||||

| Pb | <0.015 mg/L (0.01) | ||||

| * IUA_LN01 | Quantity | Abstraction | Allocation | New and existing water users to comply with allocation condition. | _ |

| Groundwater level | Time series | _ | peak drawdown < 2.5 m 75th percentile drawdown < 2.2 m | ||

| Quality | Nutrients | NO3/NO2 | Trend should not exceed the 75th percentile or the TWQR for domestic use (in brackets) if higher for Compounds of Concern. | <5.4 mg/L | |

| Salt | EC | <116 mS/m (70) | |||

| SO4 | <123 mg/L (200) | ||||

| Na | <100 mg/L (100) | ||||

| Cl | <115 mg/L (100) | ||||

| F | <0.9 mg/L (1) | ||||

| Mg | <48 (mg/L 30) | ||||

| Quantity | Abstraction | Allocation | New and existing water users to comply with allocation condition. | _ | |

| Groundwater level | Time series | _ | peak drawdown < 16.5 m 75th percentile drawdown < 8.7 m | ||

| Quality | Nutrients | NO3/NO2 | Trend should not exceed the 75th percentile or the TWQR for domestic use (in brackets) if higher for Compounds of Concern. | <0.1 mg/L | |

| Salt | EC | <402 mS/m (70) | |||

| SO4 | <501 mg/L (200) | ||||

| Na | <632 mg/L (100) | ||||

| Cl | <722 mg/L (100) | ||||

| F | 0.7 mg/L (1) | ||||

| Mg | <121 mg/L (30) | ||||

| Pb | <0.045 mg/L (0.01) | ||||

| Quantity | Abstraction | Allocation | New and existing water users to comply with allocation condition. | _ | |

| Groundwater level | Time series | peak drawdown < 20.6 m 75th percentile drawdown < 15.7 m | |||

| Quality | Nutrients | NO3/NO2 | Trend should not exceed the 75th percentile or the TWQR for domestic use (in brackets) if higher for Compounds of Concern. | <6.4 | |

| Salt | EC | <235 mS/m (70) | |||

| SO4 | <150 mg/L (200) | ||||

| Na | <196 mg/L (100) | ||||

| Cl | <441 mg/L (100) | ||||

| F | <1.3 mg/L (1) | ||||

| Mg | <69 mg/L (30) | ||||

| Pb | <0.045 mg/L (0.01) | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Mulangaphuma, L.H.; Jovanovic, N. A New Methodological Framework for the Determination of Water Resource Classes and Resource Quality Objectives: A Case Study for the Mzimvubu to Tsitsikamma Water Management Area 7 (WMA7). Water 2026, 18, 70. https://doi.org/10.3390/w18010070

Mulangaphuma LH, Jovanovic N. A New Methodological Framework for the Determination of Water Resource Classes and Resource Quality Objectives: A Case Study for the Mzimvubu to Tsitsikamma Water Management Area 7 (WMA7). Water. 2026; 18(1):70. https://doi.org/10.3390/w18010070

Chicago/Turabian StyleMulangaphuma, Lawrence Humbulani, and Nebo Jovanovic. 2026. "A New Methodological Framework for the Determination of Water Resource Classes and Resource Quality Objectives: A Case Study for the Mzimvubu to Tsitsikamma Water Management Area 7 (WMA7)" Water 18, no. 1: 70. https://doi.org/10.3390/w18010070

APA StyleMulangaphuma, L. H., & Jovanovic, N. (2026). A New Methodological Framework for the Determination of Water Resource Classes and Resource Quality Objectives: A Case Study for the Mzimvubu to Tsitsikamma Water Management Area 7 (WMA7). Water, 18(1), 70. https://doi.org/10.3390/w18010070