Abstract

Storage-oriented reservoir schemes are effective for large-scale hydrological modeling, yet two important limitations remain. First, although some reservoirs seasonally adjust flood storage capacity (FSC), no global study has examined whether constant or seasonally varying FSC performs better. Second, these schemes rely on empirical operational-zone parameterization, but its impact on simulation accuracy has never been systematically assessed. This study presents an open-source Python module integrating three leading storage-oriented schemes (S25, Z17, H22) with both constant and seasonally varying FSC options. Evaluated using daily observations from 289 global reservoirs via Nash-Sutcliffe Efficiency (NSE), constant FSC significantly outperforms seasonal variation, increasing median outflow NSE by 0.18–0.47 and reducing storage error magnitude by 38–61%, and is selected as optimal for 84% of reservoirs. Sensitivity analysis across eight alternative zoning schemes shows that, under constant FSC, outflow remains stable, whereas seasonal FSC sharply increases sensitivity. Storage simulation is more sensitive overall, yet constant FSC consistently yields the smallest errors. This work provides the first global comparison of FSC strategies and the first systematic assessment of operational zone parameter uncertainty. It strongly recommends constant FSC with H22 or S25 as the default for large-scale modeling. The released module offers a flexible, reproducible platform for the community. Future extensions may incorporate demand-driven rules and hybrid calibration to further improve performance in data-rich regions.

1. Introduction

Reservoirs serve as indispensable components of global water infrastructure, regulating river flows to support a wide array of societal needs, including flood mitigation, irrigation, water supply, and hydropower production [1,2]. Worldwide, over 24,000 large reservoirs regulate approximately 63% of all global rivers, storing more than 8000 km3 of water—equivalent to about 150% of annual river discharge—and accounting for 61% of seasonal variability in surface water storage [3,4,5,6]. This extensive network not only disrupts natural river connectivity but also provides critical storage for multiple purposes, often combining functions like water supply in arid regions with hydropower or flood control in humid climates [7,8]. As reservoir development accelerates in emerging economies across Asia, South America, and Africa, driven by population growth and rising demands for food, energy, and water security [9,10,11], the ability to simulate their operations accurately becomes increasingly vital. Effective simulations can inform water resource planning, assess historical trends, and project future availability under changing climatic conditions, where reservoirs may either buffer or exacerbate vulnerabilities.

Despite their importance, simulating reservoir operations poses substantial challenges. Reservoir dynamics are influenced by human decisions that balance competing objectives, such as meeting downstream demands while preventing overflows or maintaining minimum levels for ecosystems [12,13]. Data limitations exacerbate these issues: detailed records of inflows, outflows, storage, and operational rules are often unavailable or restricted, particularly in data-scarce regions [14]. This scarcity hinders the development of models that capture the full spectrum of reservoir behaviors, leading to uncertainties in predictions of storage fluctuations and downstream flow alterations. For instance, reservoirs can dampen streamflow variability, with pronounced effects during extremes, yet replicating this in simulations requires overcoming biases from incomplete datasets [15].

Existing approaches to reservoir operation simulation have evolved to address these hurdles, broadly categorized into simplified generic methods and more data-intensive techniques. Early efforts focused on basic water balance calculations using static attributes like storage capacity and surface area from databases such as GRanD or the World Registry of Dams [16,17]. These methods estimate releases as excess water beyond maximum capacity, making them straightforward but prone to overestimating storage by assuming reservoirs are perpetually full [18]. Subsequent advancements incorporated water demands and primary uses, adjusting releases based on factors like long-term inflow ratios or seasonal priorities [19,20]. For example, demand-driven schemes define downstream “command areas”—regions reliant on reservoir releases—ranging from 250 km to 1100 km downstream, influencing how operations respond to short-term or long-term variability [21]. However, the sensitivity of these areas to model outcomes remains underexplored, and generic schemes often fail to reflect regional differences in reservoir purposes, such as the dominance of water supply in national contexts versus irrigation or hydropower globally [22].

Storage-oriented approaches represent a significant step forward, dividing reservoir capacity into zones (e.g., dead, conservation, flood, and emergency) and linking outflows to storage levels via storage parameters, combined with flow percentiles [23,24]. These methods, exemplified by schemes in models like LISFLOOD and CaMa-Flood, use empirical or satellite-derived data to define zone-specific rules, improving realism over basic balance methods [25,26,27]. Recent innovations leverage remote sensing for transient characteristics: satellite altimetry and surface area data enable back-calculation of storage time series, revealing that over 50% of global reservoirs remain unfilled due to factors like sedimentation and increasing demands [28]. Datasets like GloLakes and HydroSat provide storage anomalies that can refine algorithms, showing promise in capturing seasonal patterns and downstream impacts [29,30]. For instance, calibrating algorithms against these anomalies has improved storage simulations for many reservoirs, outperforming uncalibrated methods like the Hanasaki algorithm by enhancing Nash-Sutcliffe efficiency in up to 68% of cases [31].

Despite these advances, three critical limitations persist in current storage-oriented reservoir schemes typically employed in large-scale hydrological and land-surface models. First, current approaches rely heavily on single modeling schemes, overlooking the significant operational diversity across reservoirs (e.g., water supply vs. irrigation) and regions [32]. There is a lack of a simple, unifying, storage-oriented model framework that can efficiently represent this diversity. Second, existing models commonly assume constant flood capacities year-round, which fails to account for adaptive operations crucial in seasonal climates. While adjusting flood storage based on inferred wet-dry periods offers potential benefits, the comparative effectiveness and systematic evaluation of these seasonal strategies remain largely unexplored in the literature [33,34,35]. Third, storage-oriented models typically rely on empirical parameters to determine the four operational zones (dead, conservation, flood, surcharge). The impact of these fixed zoning parameters on reservoir simulations has not yet been systematically quantified. Overcoming these gaps requires flexible tools that bridge modeling simplicity with the capacity for adaptive, data-driven insights.

To overcome these gaps and provide a unified, efficient tool, we introduce an open-source Python module that integrates three established storage-oriented models: S25 [36], Z17 [27], and H22 [26]. Our goals are threefold: (1) we provide users with a flexible platform to easily switch between models and compare their performance under default settings, which is essential for informed model selection in large-scale simulation studies. Then, we explore two key operational features within these storage-oriented models and their impact on reservoir simulations. (2) We assess the comparative performance between constant flood storage capacity and seasonally varying flood storage capacity. (3) We investigate the impact of empirically determined parameters used to define the four operational zones. Quantifying the impacts of these two features is critical for improving the reliability of large-scale simulations and selecting appropriate flood storage strategies and empirical storage zoning parameters. We assess the module using observed inflow, outflow, and storage from 289 global reservoirs to demonstrate its capability and provide comparative insights across reservoir types and sizes. The remainder of the paper is structured as follows: Section 2 details the methodology, data, and module architecture; Section 3 presents evaluation results; and Section 4 discusses implications, limitations, and avenues for future enhancements.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Overview of the Module Framework

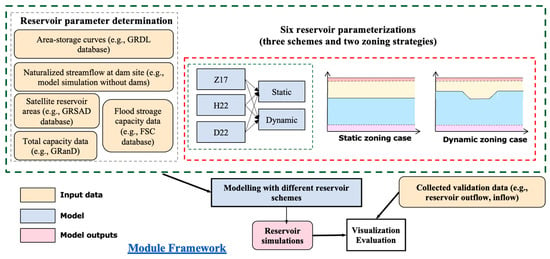

The Python (Version 3.10.12) module developed in this study is designed for simulating reservoir operations at individual or large-scale levels, focusing on storage-based schemes with flexible strategies that implement either seasonally varying or constant flood storage capacity. Figure 1 illustrates the overall structure of the module framework, including data preparation (e.g., inflow and reservoir characteristics), module execution with model selection and flood storage capacity options, performance analysis (using evaluation metrics), and visualization of results. Continuous time series of inflow and reservoir characteristics are crucial for running the storage-based models in the module [37,38,39]. For the current study, all modeled reservoirs are in the global reservoir dataset GRanD [16], which provides locations and total storage capacities. We compiled daily in situ observations of inflow, outflow, and storage for 289 globally distributed reservoirs based on data availability, containing all these variables, obtained from previous studies [32]. These reservoirs have at least 10 years of continuous daily records before 2020. Their spatial distribution, main uses, and storage capacities can be found in the reference [40].

Figure 1.

Computational framework adopted in this study. Note that user can replace or extend these sample data as needed, and users can still use the model even if part of the variables or functions are not used. All the abbreviations of the datasets shown in this figure can be found in the main text.

The module requires five primary inputs. These include continuous daily inflow time series data and a continuous time array corresponding to the inflow data. Additionally, continuous monthly satellite area time series and continuous naturalized streamflow time series data at dam sites are necessary for parameter estimation in specific models, as detailed in Section 2.2. Finally, static reservoir attributes, specifically total capacity data and flood storage capacity data, are required for defining the operational zones. Crucially, no external parameters are required from the user, as all parameters derived in Section 2.2 are determined internally by the module based on the provided time series and attribute data. The module processes this structured input to compute daily outflow and updated storage time series. The comprehensive output includes the simulation results under different models with both seasonal and constant flood storage capacity strategies, yielding a total of six distinct experimental time series for analysis. All datasets are publicly accessible, see the Data Availability Section.

2.2. Development of the Reservoir Operation Module

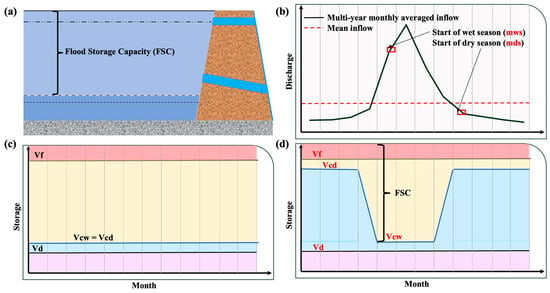

The module incorporates three widely recognized storage-based reservoir operation models: S25 [36], Z17 [27], and H22 [26]. These models were selected due to their computational efficiency, minimal data requirement (relying primarily on inflow statistics), and proven adaptability in large-scale and data-scarce environments, making them highly suitable for global reservoir simulation studies. These models divide total reservoir storage into four distinct zones—dead storage (Vd), water-use storage (Vc), flood storage (Vf), and emergency storage—mirroring real-world operational practices (Figure 2a). The zone below the flood control limit is designated as normal water storage, while the area above constitutes the flood storage capacity (FSC). Historically, FSC estimation methods vary: H22 leverages satellite data for individual reservoir estimates, Z17 assumes a fixed proportion of total capacity, and S25 fused reported and satellite data using machine learning, offering a more adaptive approach.

Figure 2.

Illustration of reservoir storage zoning for our three reservoir operation schemes. (a) Reservoir storage zones: dead, water use and supply, flood control, and emergency zone. (b) Identifying wet and dry seasons from reservoir inflow climatology. The wet (dry) season refers to the months where the average inflow is higher (lower) than the mean annual inflow. Notably, this is a typical example with one peak inflow in summer; for other cases, please refer to Figure 3. (c) Static flood storage capacity case, where flood storage capacity (FSC) remains constant year-round. (d) Seasonally varying flood storage capacity case, where FSC increases during the wet season and decreases during the dry season. Vd, Vcd, Vcw, and Vf are dead water storage, conservation storage during dry season, conservation storage during wet season, and water storage at high flooding level, respectively. The variation in Vc values is evenly distributed over each day of the month to avoid sudden changes.

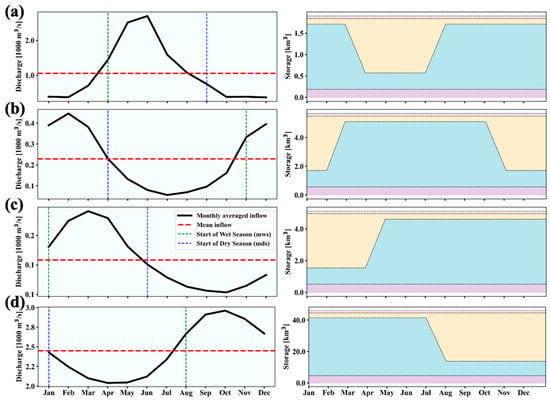

To enhance the module’s versatility, it supports constant and seasonally varying flood storage capacity strategies (Figure 2c,d). In the constant approach, FSC remains constant throughout the year. The dynamic FSC increases during wet seasons, offering maximum protection, and decreases during dry seasons, maximizing water conservation. Wet and dry seasons are determined from inflow climatology, where months with average inflows exceeding or falling below the annual mean are classified accordingly (Figure 2b). Specifically, the dry season conservation level is set to 90% of the total capacity, which is chosen as a practical upper threshold to balance maximizing water use and maintaining a minimum buffer against unexpected early floods, thus avoiding a complete assumption of perpetual fullness. For cases with multiple inflow peaks (multi-modal patterns), the primary (largest) inflow peak defines the wet season to ensure the scheme is responsive to the most significant flood risk period. Figure 3 illustrates six representatives scenarios, highlighting diverse inflow patterns and their corresponding water storage zone allocations across global reservoirs.

Figure 3.

Illustration of reservoir storage zones using the seasonally varying flood storage capacity strategy. (a–d) refer to four representative cases, i.e., wet season in the summer, dry season in the summer, spring flood, and winter flood. The left panel indicates the hydrograph of the reservoir, while the right panel indicates the storage zones of the reservoir. For the storage zones, please refer to Figure 2.

Operational rules for outflows are tailored to each zone and model, guided by specific parameters (see details in [40]). All models follow a consistent release policy: minimal outflow in dead storage to preserve water for environmental needs; demand-driven releases in water-use zones, capped to avoid flood levels; storage- and capacity-dependent outflows in flood zones to manage flood risks; and maximum releases in emergency zones to prevent overtopping during extreme events. Parameter sets differ by model: H22 uses Qf_h22 (30% of 100-year flood), Qn_h22 (long-term mean flow), and Abasin_h22 (upstream catchment area in m2); Z17 employs Qs_z17 (97th percentile), Qn_z17 (30th percentile), and Qmin_z17 (5th percentile) of inflow; S25 includes Qs_s25 (99th percentile), Qmin_s25 (10th percentile), Qn_s25 (long-term mean flow) and Vtar_s25 (monthly median storage from satellite data). These parameters are estimated using inflow percentiles or satellite-derived medians, even when historical records are available, to simulate conditions typical of data-scarce environments.

The module’s core is the RunningOPs function, which executes simulations based on user inputs: a time array (tmptime), time step (DT), inflow (Qin), and reservoir capacities (e.g., maxSTORres). The function processes daily data, updating storage via a mass balance equation, ensuring non-negative storage by resetting to zero if negative, and adjusting outflow to match inflow in such cases. It also calculates variable conservation levels (vc) based on wet/dry seasons when dynamic is enabled, using a linear transition across month boundaries to avoid abrupt shifts. Outputs include a time series of outflow and storage, stored in a pandas DataFrame for analysis. The GetwetdryMonth function complements this by analyzing inflow to determine wet (mws) and dry (mds) season start months, enhancing the dynamic zoning’s responsiveness to seasonal patterns.

2.3. Datasets and Metrics for Model Evaluation

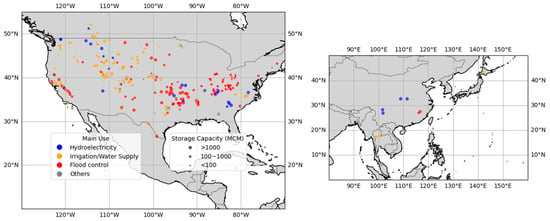

To operate the storage-based reservoir models within the module, continuous time series of inflow and reservoir properties (e.g., total storage capacity) are essential. Reservoir information was drawn from the GRanD dataset, which provides critical details such as geographic locations, physical characteristics, and storage capacities. Daily in situ measurements of inflow, outflow, and storage for 289 globally distributed reservoirs were aggregated from existing studies [14,40], selected for their comprehensive data coverage. These reservoirs are characterized by at least 10 years of continuous daily records prior to 2020, ensuring a robust temporal assessment spanning diverse climate regimes. These reservoirs vary widely, with storage capacities ranging from 0.01 to 39.3 km3. Figure 4 presents their global distribution, primary uses (e.g., irrigation, hydropower), and capacity categories, illustrating the diverse characteristics across different regions. A more comprehensive summary of the dataset is provided in the reference [40], with the percentage distribution across main usage categories and key statistical metrics.

Figure 4.

Location of the 289 reservoirs investigated in this work.

The core experiments evaluate the three models (S25, Z17, H22) using default parameter settings across two flood storage capacity strategies (static and seasonally varying). Furthermore, the effectiveness of storage-based models is intrinsically linked to the parameterization of the four storage zones. Since the current default parameterizations introduce inherent uncertainties, we therefore conduct an extensive analysis to quantify the sensitivity of model performance to variations in these parameters.

In this study, performance evaluation is based solely on the Nash-Sutcliffe Efficiency (NSE), a widely recognized metric for assessing the fit between simulated and observed time series, with an optimal value of 1 [41].

3. Results

3.1. Spatial Distribution of Model Performance

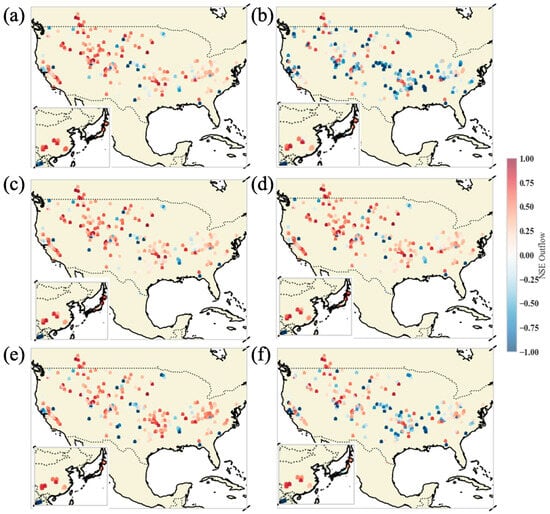

The evaluation across 289 reservoirs reveals a consistent performance advantage for the constant Flood Storage Capacity (FSC) strategy over the seasonally varying approach (Figure 5). For outflow simulations, employing constant FSC yielded median NSE values of 0.30 (Z17), 0.31 (H22), and 0.35 (S25). In contrast, introducing seasonal variations resulted in notably lower performance for the Z17 and S25 models, with median NSEs dropping to −0.17 and 0.13, respectively, while the H22 model maintained comparable performance (0.31). Effectively, the static approach boosted median outflow NSE by 0.17 to 0.47 for Z17 and S25. These benefits were particularly pronounced in arid and temperate climates, where 33% of reservoirs exceeded an NSE of 0.5 under the constant strategy, compared to just 22% with seasonal rules. The gains were even more substantial in large reservoirs (>1000 MCM) managed for hydropower or flood control; here, the proportion of reservoirs achieving NSE > 0.5 rose from 24% under seasonal rules to 35% with the static approach, suggesting that fixed target levels better accommodate operational complexities without introducing unnecessary variability.

Figure 5.

Spatial distribution of NSE for outflow simulations across 289 reservoirs. The panels compare the performance of three models (Z17, H22, S25) under two FSC strategies: constant FSC (a,c,e) and seasonally varying FSC (b,d,f).

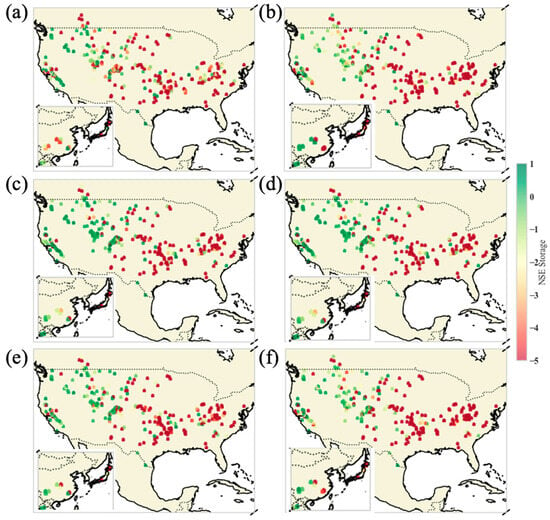

Simulating storage dynamics remains challenging within this uncalibrated framework, generally yielding negative NSE values due to cumulative volume estimation errors (Figure 6). However, the constant FSC strategy significantly mitigated these errors. Median storage NSE values improved to −3.84 (Z17), −2.26 (H22), and −3.67 (S25), a marked improvement over the considerably lower scores observed under seasonal adjustments (−6.21 for Z17/S25 and −2.31 for H22). This equates to a 38–61% reduction in the magnitude of storage errors, underscoring the stabilizing effect of a year-round fixed supply level. This stabilizing impact was especially evident in small- to medium-sized reservoirs (<1000 MCM) used for irrigation or water supply (n = 93). In this category, the constant approach virtually eliminated the most severe outliers (NSE < −50), reducing their occurrence from 197 cases under seasonal rules to 162. Even in cold zones with less extreme demand fluctuations, the fixed approach proved more effective at limiting error propagation, ensuring more reliable long-term storage trajectories in the absence of site-specific calibration.

Figure 6.

Spatial distribution of NSE for storage simulations across 289 reservoirs. The panels compare the performance of three models (Z17, H22, S25) under two FSC strategies: constant FSC (a,c,e) and seasonally varying FSC (b,d,f).

In summary, applying constant FSC consistently elevated median outflow NSE by 0.18–0.47 and reduced the severity of storage errors by 40–60% across the three models. These improvements were robust across diverse climate zones, reservoir capacities, and operational purposes. Our findings suggest that attempting to incorporate seasonal flood storage capacity dynamics at a global scale—without the support of reservoir-specific calibration or high-resolution data—tends to amplify simulation instability rather than refine predictive accuracy. Consequently, the constant FSC strategy emerges as the more robust default for large-scale routing applications, offering a practical balance between simplicity and performance. While theoretically appealing, seasonal variations should be implemented with caution and rigorous validation to avoid degrading model fidelity.

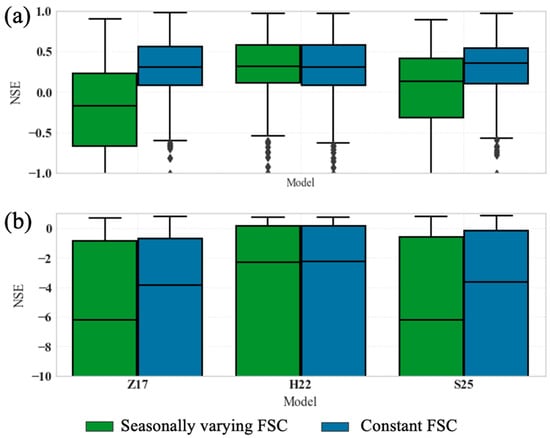

3.2. Overall Performance Among Models

Boxplots in Figure 7 visually confirm the clear superiority of the constant FSC strategy in enhancing overall simulation performance across the three models. For outflow simulation, the constant approach yielded median NSE values between 0.3 (Z17) and 0.35 (S25). This marks a substantial improvement, raising the median NSE for the S25 and Z17 models by 0.22 to 0.47 compared to the seasonally varying rules (where Z17’s median was −0.17). Notably, the consistency of the constant strategy is evident in the interquartile range (IQR): S25’s IQR was contained between 0.1 and 0.54 under constant FSC, significantly narrower than the −0.31 to 0.41 range observed under seasonal variations, which reflects heightened sensitivity to inflow patterns. Similarly, the Z17 model showed a more contained IQR (0.08 to 0.55) with the fixed approach compared to the wide range under seasonal adjustments. Storage simulations, while generally less robust, also benefited substantially from the constant FSC approach. Median storage NSE scores improved across all models: H22 achieved −2.26, S25 achieved −3.67, and Z17 achieved −3.84. This is superior to the significantly lower performance under seasonal rules (e.g., −6.21 for S25 and Z17). The stability of the constant strategy is demonstrated by its ability to mitigate severe underestimation in storage volumes, reducing the lower interquartile bound from approximately −47 to −23 in Z17 and from −51 to −31 in S25. Overall, 37% of all model runs achieved a storage NSE greater than −1 under constant FSC, compared to 34% with seasonal variations, emphasizing how fixed target levels stabilize large reservoir simulations.

Figure 7.

NSE performance among models and two FSC strategies. (a) NSE for outflow, with seasonally varying and constant FSC for Z17, H22, and S25. (b) NSE for storage.

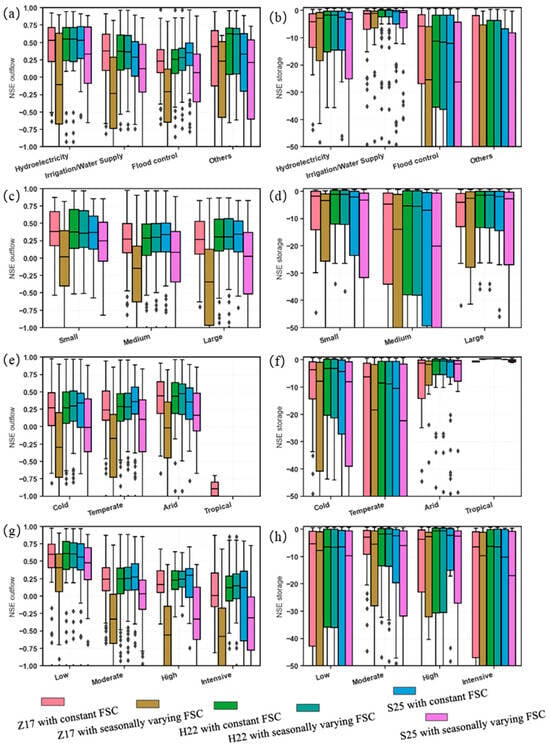

3.3. Performance by Reservoir Categories

Analysis of performance across specific reservoir categories confirms the robustness of the constant FSC strategy, which consistently outperformed seasonal variations in target levels. Gains were significant based on main use. For hydroelectricity reservoirs (Figure 8), the S25 model with the constant approach achieved the highest median outflow NSE of 0.53, representing a 0.20 improvement over the seasonal variant, driven by more stable management of peak flows. Irrigation and water supply reservoirs showed similar benefits (S25 median 0.29 constant versus 0.13 seasonal), and flood control performance improved notably (median 0.35 versus 0.07), indicating that fixed target levels adequately capture extreme events without unnecessary complexity. By storage capacity, the benefits were most pronounced in large reservoirs (>1000 MCM), which achieved a superior median outflow NSE of 0.35 (S25 with constant FSC)—an improvement of 0.33 over the seasonal approach—due to better management of cumulative volumes. Medium and small reservoirs also showed robust median gains, though small reservoirs exhibited a wider interquartile range under seasonal variations, highlighting their sensitivity to limited data. Climate analysis revealed substantial stability advantages, particularly in areas where seasonal variations are high. Temperate reservoirs achieved a median outflow NSE gain of 0.25 (S25 median 0.36 constant), and arid regions also benefited significantly (median 0.36 versus 0.16), due to reduced variability in inflow management. Notably, in cold climates, the constant FSC provided critical stability during seasonal shifts (median 0.34 versus −0.01).

Figure 8.

NSE performance by reservoir categories. (a,b) reservoir main use, (c,d) storage category, (e,f) climate category, (g,h) reservoir regulation. Each category level shows six boxes: three models with two FSC strategies.

In summary, the constant FSC strategy consistently improves median outflow NSE by 0.09 to 0.33 and reduces the storage error magnitude by 38% to 61% across all reservoir categories. These category-specific insights, especially the substantial gains in large hydroelectric reservoirs and arid climates, reinforce that fixed target levels provide a more stable and effective approach for diverse reservoir types at a global scale, circumventing the instabilities often induced by uncalibrated seasonal adjustments.

3.4. Best-Performing Model Variant per Reservoir

To practically assess the implications of model and strategy selection, we identified the single best-performing configuration for each of the 289 evaluated reservoirs. This selection maximized the NSE for outflow and storage simulations separately across the six available combinations: the three models paired with either a constant or seasonally varying FSC strategy.

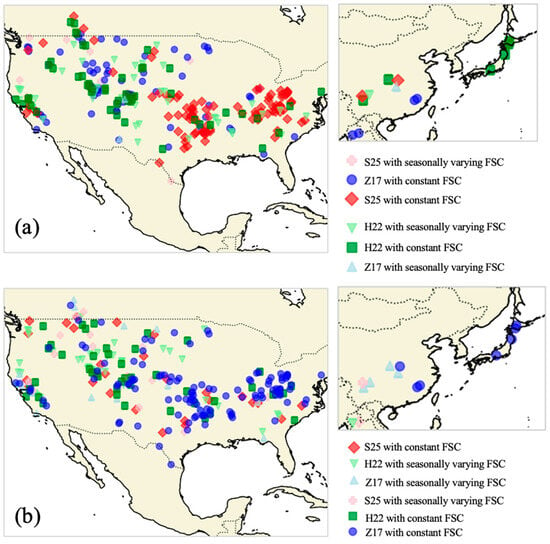

When the primary objective was to maximize outflow simulation accuracy (Figure 9a), the constant FSC strategy was overwhelmingly preferred, emerging as the best option for the vast majority of reservoirs, specifically 83.7% (242 out of 289). The seasonally varying FSC was chosen for only 16.3% of cases. Among the three routing models, H22 was the most frequently selected (40.5%), followed closely by S25 (31.8%) and Z17 (27.7%). The dominance of the constant FSC approach was consistent, with the H22-constant variant proving the single most successful configuration, optimal for 34.3% of all reservoirs. Seasonally varying FSC configurations were rarely optimal, primarily being selected in isolated cases for specific temperate or cold-climate reservoirs, typically those with hydroelectric or flood-control purposes where pronounced seasonal inflow variability is observed but still better captured by one of the variants in isolation. The category-specific patterns observed consistently reinforce the robustness of the constant FSC approach. Across primary reservoir use, constant FSC was preferred in 91% of hydroelectric reservoirs, 85% of irrigation/water-supply reservoirs, and 79% of flood-control reservoirs. The preference for constant FSC also generally increased with reservoir storage capacity, ranging from 79% in small reservoirs to 89% in large reservoirs (>1000 MCM). Furthermore, the constant FSC strategy dominated across climate zones, selected in 93% of arid and 87% of temperate regions, and maintained a substantial majority (74%) even in cold zones. This indicates that the fixed approach provides crucial stability regardless of the typical climate-driven inflow patterns. Across regulation levels, the constant FSC strategy was chosen in over 80% of cases, demonstrating its consistent effectiveness irrespective of operational intensity.

Figure 9.

Spatial map of best model variant per reservoir. (a) Best for outflow; (b) Best for storage.

When the objective shifted to maximizing storage NSE (Figure 9b), the preference for constant versus seasonally varying FSC became more balanced, although still leaning towards constant (55.7%) over seasonally varying (44.3%). This transition reflects the greater inherent difficulty of accurately simulating storage dynamics within an uncalibrated global framework. For some reservoirs with highly seasonal operating rules, the seasonally varying FSC can occasionally mitigate cumulative error propagation, leading to its selection. H22 remained the most frequently selected model (47.1%), underscoring its superior handling of volume conservation across both constant and seasonally varying strategies, thereby demonstrating its structural advantage in storage-related tasks compared to S25 and Z17.

In summary, when outflow simulation is the primary concern—which is typically the case in large-scale hydrological and water-resource modeling—the constant FSC strategy combined with either the H22 or S25 scheme provides the best performance for the vast majority (>83%) of the evaluated reservoirs. This dominance is robust and holds irrespective of the reservoir’s climate, size, or primary use. Seasonal FSC variations rarely emerge as the optimal choice at a global scale without site-specific calibration. These per-reservoir results strongly corroborate the aggregate findings of Section 3.1, Section 3.2 and Section 3.3 and support the recommendation of constant FSC as the default, most robust operating rule for uncalibrated global reservoir modeling applications.

4. Discussion

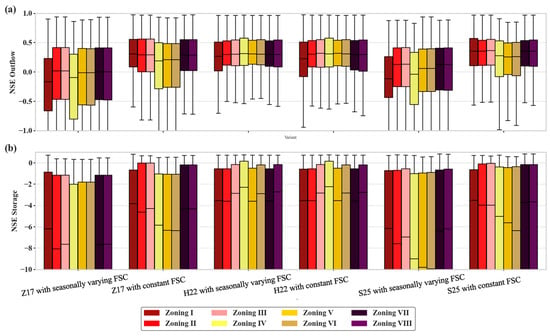

4.1. Sensitivity to Operational Zone Parameterization

The division of total reservoir capacity into four operational zones (dead storage Vd, conservation storage Vc, flood-control storage Vf, and emergency zone) forms the mechanistic core of all storage-based reservoir operation schemes. These zone boundaries directly govern release decisions across the full spectrum of hydrological conditions and therefore exert primary control over both outflow and storage simulation accuracy. In the benchmark analyses presented in Section 3.1, Section 3.2, Section 3.3 and Section 3.4, each model was run with its original published default parameterization, deliberately retained to represent realistic uncalibrated global modeling practice. The Z17 scheme (Zoning I) uses simple fixed percentages: dead storage at 10% of total capacity, conservation zone extending to 30%, and flood-control level at 90%. The H22 scheme (Zoning IV) derives conservation volume from satellite-observed active storage, sets dead storage to half of that value, and places the flood-control limit at conservation volume plus 80% of the estimated flood buffer. The S25 scheme (Zoning VIII) estimates normal operating storage via machine-learning fusion of reported and satellite data, fixes dead storage at 10% of total capacity, and likewise positions the flood-control level at conservation volume plus 80% of the remaining flood buffer.

To assess the uncertainty stemming from these zone assumptions and evaluate their robustness, we performed a comprehensive sensitivity experiment involving 48 unique configurations per reservoir, combining three models, two flood storage capacity (FSC) strategies, and eight distinct operational-zone schemes, as detailed in Figure 10. These eight operational-zone schemes were carefully designed to cover a realistic spectrum of parameterizations, reflecting both traditional and contemporary approaches. They varied the dead storage fraction (set at either 10% or 20% of total capacity), the method for estimating flood storage (from a conventional 37% of total capacity, as used in older generic models, to the estimates by Z17, H22, or S25). For instance, Zoning II, with a fixed 37% flood storage and 10% dead storage, contrasts with Zoning I, Z17’s default scheme, while Zoning IV adopts H22’s satellite-informed approach.

Figure 10.

Effect of storage zones on reservoir simulations. (a) NSE for outflow; (b) NSE for storage.

Median NSE analysis across the 289 reservoirs reveals that outflow simulation is only moderately sensitive to zoning choice under constant FSC, with values ranging from 0.188 to 0.360 (S25 with fixed 37% flood storage and 20% dead storage), and an overall median of approximately 0.30. The original defaults already perform near the upper end of this range: Zoning I yields 0.30–0.31, Zoning IV 0.31–0.32, and Zoning VIII 0.35 for their respective models under static FSC. Simple fixed-proportion schemes with moderate-to-large flood buffers (Zoning II and III) occasionally outperform the observation-constrained defaults by 0.01–0.04 in S25 and H22, particularly in reservoirs with relatively stable flood risk, suggesting that avoiding over-complex estimation of conservation volume can reduce occasional overestimation of low flows. Increasing dead storage from 10% to 20% consistently produces small but systematic gains of 0.01–0.03 in outflow NSE across nearly all model–strategy combinations, reflecting improved resilience against prolonged drawdown in irrigation-dominated or arid settings.

Storage simulation proves far more sensitive, with median NSE spanning −13.9 (poorly matched configurations) to −2.26 (H22 using its native Zoning IV under constant FSC). The original H22 zoning (IV) clearly produces the least negative storage errors (−2.26 to −2.31), confirming the value of satellite-constrained active-storage estimates for long-term volume tracking. In contrast, imposing a fixed 37% flood buffer (Zoning II/III) markedly degrades storage performance (medians around −4 to −6), because this classic generic assumption tends to over-allocate flood space in reservoirs whose actual operating range is much narrower. Raising dead storage to 20% mitigates the most extreme negative outliers by 10–20%, especially beneficial in older reservoirs affected by sedimentation, but at the cost of slightly poorer outflow simulation in flood-prone sites.

In conclusion, while alternative zoning parameterizations can yield modest outflow improvements of up to 0.04–0.05 in specific contexts, the original published defaults of H22 (Zoning IV) and S25 (Zoning VIII) already lie close to the global performance frontier under constant FSC, and H22’s satellite-informed zoning stands out as uniquely effective for storage simulation. The dominant source of performance variation, therefore, remains the choice between constant and seasonally varying FSC rather than fine details of zone delineation. For uncalibrated large-scale applications, adopting constant FSC together with any of the three established zoning schemes provides a robust and near-optimal solution, with only marginal further gains available from context-specific retuning of dead-storage fraction or flood-buffer size.

4.2. Insights on Constant and Seasonally Varying Flood Storage Capacity Strategies

The central finding of this study is the overwhelming superiority of a constant FSC strategy across virtually all evaluated metrics, reservoir categories, and per-reservoir selections. In an uncalibrated global context, the introduction of seasonal variation in the flood-control limit, defined by simple climatology-based rules, consistently and often dramatically degrades outflow simulation skill. Such seasonality only marginally stabilizes storage trajectories in a minority of cases. This counterintuitive result arises because the rudimentary climatology rules used to define wet and dry seasons are fundamentally inadequate for capturing the complex, institution-specific trade-offs that govern real-world seasonal drawdown and refilling decisions.

In the absence of site-specific operating policies or high-resolution demand data, the imposed seasonality introduces artificial oscillations in target storage that amplify rather than dampen mismatches with observed behavior. This is particularly evident in reservoirs managed primarily for irrigation, water supply, or hydropower in arid and temperate climates. Even within strongly seasonal monsoon or snowmelt regimes, the marginal benefit of a lowered dry-season flood buffer is frequently outweighed by the risk of premature emptying or delayed refilling when inflow timing deviates from the long-term climatological mean. Conversely, the constant FSC strategy provides a stable upper operating target that implicitly accommodates diverse management objectives through the underlying release functions of the storage-oriented models themselves. When paired with the observation-constrained operational zones offered by models such as H22 or S25, the constant FSC approach delivers robust, high-quality outflow simulations across virtually all reservoir types and sizes, while simultaneously conferring considerable resilience against uncertainties in the zone delineation process.

4.3. Implications and Future Directions

The open-source Python module presented here provides the hydrological modeling community with a lightweight, transparent, and fully reproducible framework for testing and comparing state-of-the-art storage-oriented reservoir schemes under both constant and seasonally varying flood storage regimes. By demonstrating that constant FSC, combined with any of the three established models—particularly H22 and S25—provides near-optimal performance for the vast majority of global reservoirs in an uncalibrated setting, this work supplies clear practical guidance for large-scale land-surface and hydrological modeling efforts.

Implementing seasonal FSC adjustments at continental or global scales without reservoir-specific calibration is not recommended as a default strategy; such adjustments should be reserved for targeted regional studies where detailed operating rules or high-quality demand data are available to inform the timing and magnitude of flood-buffer variation. Future enhancements could profitably extend the module in several directions. Integrating probabilistic or ensemble-based approaches to both zoning parameters and seasonal timing would allow for the formal propagation of structural uncertainty into downstream water-resource assessments. Furthermore, coupling the module with emerging global datasets on irrigation water demand, hydropower scheduling, or multi-purpose operating policies would enable more realistic dynamic FSC rules that move beyond simple inflow climatology. Finally, incorporating automated calibration routines for selected critical reservoirs—while retaining fully generic behavior elsewhere—could create hybrid global schemes that preserve computational efficiency yet achieve higher fidelity where accurate storage or release estimation is critical. These developments would further strengthen the module’s utility as a flexible, community-driven platform for advancing reservoir representation in Earth system models.

5. Conclusions

This study introduces a flexible, open-source Python module that unifies three state-of-the-art storage-oriented reservoir operation schemes (S25, Z17, and H22) and enables systematic comparison of constant versus seasonally varying flood storage capacity (FSC) strategies across 289 globally distributed reservoirs with long-term observed records. The results provide the clearest evidence to date that, in an uncalibrated large-scale modeling context, a constant flood storage capacity strategy consistently and substantially outperforms seasonally varying approaches. Median outflow NSE increases by 0.18–0.47, interquartile ranges narrow markedly, and severe simulation failures virtually disappear when a fixed flood-control limit is maintained year-round. This superiority holds across all climate zones, reservoir sizes, primary uses, and regulation intensities, with constant FSC selected as the best-performing option for 84% of reservoirs when outflow accuracy is prioritized.

The counterintuitive degradation induced by seasonal FSC arises from the inability of simple inflow-climatology rules to replicate the nuanced, purpose-specific operating policies that govern real reservoirs. Without site-specific demand data or institutional rules, imposed seasonal oscillations in target storage introduce artificial instability that outweighs any theoretical benefit of adaptive flood buffering. Storage simulation remains inherently more challenging and sensitive to both zoning assumptions and FSC strategy, yet even here, constant FSC reduces error magnitude by 38–61% and eliminates the most extreme outliers. Sensitivity tests further reveal that, under constant FSC, outflow performance is remarkably robust to plausible variations in operational-zone parameterization, whereas seasonal FSC dramatically amplifies vulnerability to zoning errors.

Among the three integrated models, H22 and S25 emerge as the strongest performers under the recommended constant-FSC framework, with H22 showing particular strength in storage simulation thanks to its satellite-constrained active-storage estimates. The original operational zones of all three schemes already lie close to the global performance frontier, confirming their suitability for uncalibrated applications and underscoring that the dominant control on simulation skill is the choice of FSC strategy rather than fine details of zone delineation.

These findings carry immediate practical implications: for continental- to global-scale hydrological and land-surface modeling where reservoir-specific calibration is infeasible, constant flood storage capacity combined with any of the established storage-oriented schemes—preferably H22 or S25—should be adopted as the default operating rule. Seasonally varying FSC should be applied only in targeted regional studies where high-quality operating policy or demand data are available to inform realistic dynamic rules. The openly available module provides the community with a transparent, lightweight, and extensible platform to implement these recommendations, explore future refinements such as ensemble zoning or hybrid calibration, and continue advancing the representation of human water management in Earth system models.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, X.H. and X.S.; methodology, X.S.; software, L.T.; validation, X.S.; formal analysis, Y.H.; investigation, X.S.; resources, X.S.; data curation, X.H.; writing—original draft preparation, X.H.; writing—review and editing, X.S.; visualization, X.S.; supervision, X.S.; project administration, X.S.; funding acquisition, X.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Key Research and Development Project of Shanxi Province, grant number: 202202020101007, and the Shanxi Province Water Conservancy Science and Technology Research and Promotion Project, grant number 2025GM18.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets supporting this study are publicly available from various repositories. The observed daily in situ data of inflow, outflow, and storage for the studied reservoirs are accessible via the Zenodo repository at https://zenodo.org/records/6612040, accessed on 1 October 2025. The Global Reservoir and Dam (GRanD) database, providing physical reservoir attributes, can be downloaded from https://www.globaldamwatch.org/directory, accessed on 1 October 2025. Furthermore, the continuous monthly satellite reservoir area data is available at the digital object identifier https://doi.org/10.18738/T8/DF80WG, accessed on 1 October 2025, and the Flood Storage Capacity data is available on Zenodo at https://zenodo.org/records/11076525, accessed on 1 October 2025.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the editor and anonymous reviewers for their comments and suggestions, which helped a lot in making this paper better.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Xiaodong Hao was employed by the company, The Shanxi Institute of Geological Survey Co., Ltd. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Chao, B.F.; Wu, Y.H.; Li, Y.S. Impact of artificial reservoir water impoundment on global sea level. Science 2008, 320, 212–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perera, D.; Smakhtin, V.; Williams, S.; North, T.; Curry, A. Ageing water storage infrastructure: An emerging global risk. UNU-INWEH Rep. Ser. 2021, 11, 25. [Google Scholar]

- Best, J. Anthropogenic stresses on the world’s big rivers. Nat. Geosci. 2019, 12, 7–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooley, S.W.; Ryan, J.C.; Smith, L.C. Human alteration of global surface water storage variability. Nature 2021, 591, 78–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, W.; Liu, X.; Wang, K.; Bai, P.; Liu, C.; Liang, X. Estimation of global reservoir evaporation losses. J. Hydrol. 2022, 607, 127524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, T.D.; Chowdhury, A.F.M.K.; Galelli, S. On the representation of water reservoir storage and operations in large-scale hydrological models: Implications on model parameterization and climate change impact assessments. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2020, 24, 397–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Döll, P.; Fiedler, K.; Zhang, J. Global-scale analysis of river flow alterations due to water withdrawals and reservoirs. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2009, 13, 2413–2432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseini-Moghari, S.-M.; Araghinejad, S.; Tourian, M.J.; Ebrahimi, K.; Döll, P. Quantifying the impacts of human water use and climate variations on recent drying of Lake Urmia basin: The value of different sets of spaceborne and in situ data for calibrating a global hydrological model. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2020, 24, 1939–1956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boulange, J.; Hanasaki, N.; Yamazaki, D.; Pokhrel, Y. Role of dams in reducing global flood exposure under climate change. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donchyts, G.; Winsemius, H.; Baart, F.; Dahm, R.; Schellekens, J.; Gorelick, N.; Iceland, C.; Schmeier, S. High-resolution surface water dynamics in Earth’s small and medium-sized reservoirs. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 13776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grill, G.; Lehner, B.; Lumsdon, A.E.; MacDonald, G.K.; Zarfl, C.; Liermann, C.R. An index-based framework for assessing patterns and trends in river fragmentation and flow regulation by global dams at multiple scales. Environ. Res. Lett. 2015, 10, 015001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Intralawan, A.; Wood, D.; Frankel, R.; Costanza, R.; Kubiszewski, I. Tradeoff analysis between electricity generation and ecosystem services in the Lower Mekong Basin. Ecosyst. Serv. 2018, 30, 27–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Xiong, L.; Xiong, B.; Li, Y.; Xu, Q.; Cheng, L.; Xu, C.-Y. Investigating the downstream sediment load change by an index coupling effective rainfall information with reservoir sediment trapping capacity. J. Hydrol. 2020, 590, 125200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steyaert, J.C.; Condon, L.E.; Turner, S.W.D.; Voisin, N. ResOpsUS, a dataset of historical reservoir operations in the contiguous United States. Sci. Data 2022, 9, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maavara, T.; Chen, Q.; Van Meter, K.; Brown, L.E.; Zhang, J.; Ni, J.; Zarfl, C. River dam impacts on biogeochemical cycling. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2020, 1, 103–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehner, B.; Liermann, C.R.; Revenga, C.; Vörösmarty, C.; Fekete, B.; Crouzet, P.; Döll, P.; Endejan, M.; Frenken, K.; Magome, J.; et al. High-resolution mapping of the world’s reservoirs and dams for sustainable river-flow management. Front. Ecol. Environ. 2011, 9, 494–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; Nielsen, K.; Revel, M.; Liu, D.; Yamazaki, D. Res-CN (reservoir dataset in China): Hydrometeorological time series and landscape attributes across 3254 Chinese reservoirs. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2023, 15, 2781–2808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Döll, P.; Kaspar, F.; Lehner, B. A global hydrological model for deriving water availability indicators: Model tuning and validation. J. Hydrol. 2003, 270, 105–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanasaki, N.; Kanae, S.; Oki, T. Areservoir operation algorithm for global river routing models. J. Hydrol. 2006, 327, 22–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddeland, I.; Skaugen, T.; Lettenmaier, D.P. Anthropogenic impacts on continental surface water fluxes. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2006, 33, L08406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadki, M.; Munier, S.; Boone, A.; Ricci, S. Implementation and sensitivity analysis of the Dam-Reservoir OPeration model (DROP v1.0) over Spain. Geosci. Model Dev. 2023, 16, 427–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rougé, C.; Reed, P.M.; Grogan, D.S.; Zuidema, S.; Prusevich, A.; Glidden, S.; Lamontagne, J.R.; Lammers, R.B. Coordination and control—Limits in standard representations of multi-reservoir operations in hydrological modeling. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2021, 25, 1365–1388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neitsch, S.L.L.; Arnold, J.G.G.; Kiniry, J.R.R.; Williams, J.R.R. Soil and water assessment tool theoretical documentation version 2005. In Texas Water Resources Institute Technical Report; Texas Water Resources Institute: College Station, TX, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Y.; Chen, J. An operation-based scheme for a Mul-tiyear and multipurpose reservoir to enhance macroscale hydrologic models. J. Hydrometeorol. 2012, 13, 270–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burek, P.; van der Knijff, J.; de Roo, A. LISFLOOD Distributed Water Balance and Flood Simulation Model e Revised User Manual 2013; JRC Technical Reports, Joint Research Centre of the European Commission; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Hanazaki, R.; Yamazaki, D.; Yoshimura, K. Development of a reservoir flood control scheme for global flood models. J. Adv. Model. Earth Syst. 2022, 14, e2021MS002944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zajac, Z.; Revilla-Romero, B.; Salamon, P.; Burek, P.; Hirpa, F.A.; Beck, H. The impact of lake and reservoir parameterization on global streamflow simulation. J. Hydrol. 2017, 548, 552–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, F.; Minear, J.T.; Rajagopalan, B.; Wang, C.; Yang, K.; Livneh, B. Estimating reservoir sedimentation rates and storage capacity losses using high-resolution Sentinel-2 satellite and water level data. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2023, 50, e2023GL103524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, J.; Van Dijk, A.I.J.M.; Renzullo, L.J.; Larraondo, P.R. GloLakes: Water storage dynamics for 27 000 lakes globally from 1984 to present derived from satellite altimetry and optical imaging. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2024, 16, 201–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tourian, M.J.; Elmi, O.; Shafaghi, Y.; Behnia, S.; Saemian, P.; Schlesinger, R.; Sneeuw, N. HydroSat: Geometric quantities of the global water cycle from geodetic satellites. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2022, 14, 2463–2486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseini-Moghari, S.-M.; Döll, P. The value of observed reservoir storage anomalies for improving the simulation of reservoir dynamics in large-scale hydrological models. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2025, 29, 4073–4092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steyaert, J.C.; Condon, L.E. Synthesis of historical reservoir operations from 1980 to 2020 for the evaluation of reservoir representation in large-scale hydrologic models. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2024, 28, 1071–1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, N.; Wei, J.; Yang, M.; Yan, D.; Yang, C.; Gao, H.; Arnault, J.; Laux, P.; Zhang, X.; Liu, Y.; et al. Model Estimates of China’s Terrestrial Water Storage Variation Due To Reservoir Operation. Water Resour. Res. 2022, 58, e2021WR031787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, N.; Yang, M.; Wei, J.; Arnault, J.; Laux, P.; Xu, S.; Wang, H.; Yu, Z.; Kunstmann, H. Toward Improved Parameterizations of Reservoir Operation in Ungauged Basins: A Synergistic Framework Coupling Satellite Remote Sensing, Hydrologic Modeling, and Conceptual Operation Algorithms. Water Resour. Res. 2023, 59, e2022WR033026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehsani, N.; Fekete, B.M.; Vörösmarty, C.J.; Tessler, Z.D. A neural network based general reservoir operation algorithm. Stoch. Environ. Res. Risk Assess. 2016, 30, 1151–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; Yamazaki, D.; Pokhrel, Y.; Zhao, G. Improving global reservoir parameterizations by incorporating flood storage capacity data and satellite observations. Water Resour. Res. 2024, 61, e2024WR037620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Liu, J.; Xia, Y. Risk prediction of gas hydrate formation in the wellbore and subsea gathering system of deep-water turbidite reservoirs: Case analysis from the south China Sea. Reserv. Sci. 2025, 1, 52–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, L.; Lv, M.; Li, C.; Sun, Q.; Wu, M.; Xu, C.; Dou, J. Effects of crosslinking agents and reservoir conditions on the propagation of fractures in coal reservoirs during hydraulic fracturing. Reserv. Sci. 2025, 1, 36–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Kobina, F. The influence of geological factors and transmission fluids on the exploitation of reservoir geothermal resources: Factor discussion and mechanism analysis. Reserv. Sci. 2025, 1, 3–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, L.; Liu, G.; Sun, X.; Liu, P. Optimizing storage-based reservoir operation schemes for enhanced large-scale hydrological modeling: A comprehensive sensitivity analysis. J. Hydrol. 2025, 657, 133173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nash, J.E.; Sutcliffe, J.V. River flow forecasting through conceptual models part I—A discussion of principles. J. Hydrol. 1970, 10, 282–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.