Abstract

This work optimizes the energetic performance of 2,4,6-trinitrotoluene (TNT) abatement in water using a sono-photo-Fenton-like (SPF) process coupled with nano zero-valent iron (nZVI). A response–surface methodology (RSM) with a five-level central composite design (CCD) was applied to concurrently minimize specific energy consumption (SEC) from ultrasound (US) and UV irradiation while maximizing TNT removal. The optimal conditions were US power 80 W for 2 min and UV power 10 W for 6 min, yielding 73.95% TNT removal with SEC = 101.19 kWh kg−1 TNT removed. The analysis of variance (ANOVA) test revealed that US power had the greatest effect on removal efficiency, whereas UV and US exposure times predominantly influenced SEC. Relative to the other Fenton-like configurations examined, the optimized SPF achieved superior removal at lower SEC and enabled enhanced iron recovery compared with photo-Fenton process using Fe2+. When applied to actual “yellow” wastewater, the optimized SPF again outperformed the photo-Fenton process using Fe2+, reducing SEC from 380.77 to 252.60 kWh kg−1 and increasing treatment efficiency. The high-power/short-duration US paired with a low-power/short-duration UV regime provides a favorable efficacy–energy trade-off and supports pilot-scale deployment.

1. Introduction

2,4,6-Trinitrotoluene (TNT) is a toxic aromatic nitro compound, which is widely used in the military and in civil industries [1]. The production of TNT often produces many other dangerous by-products such as mononitrotoluene (MNT) and dinitrotoluene (DNT) [2]. These compounds are highly toxic; they affect the central nervous system, disrupt the ability to transport oxygen in the blood, and have a high risk of causing serious diseases such as aplastic anemia and bladder cancer with long-term exposure [3]. Effluents from these activities, commonly termed “yellow wastewater”, are strongly acidic, highly chromatic, and enriched in persistent organic pollutants; their chemical oxygen demand (COD) commonly reaches the 103 mg O2 L−1 range, substantially exceeding the discharge limits specified in QCVN 40:2025/BTNMT.

To remediate TNT-contaminated wastewater, numerous technologies have been investigated and implemented worldwide, including, but not limited to, the following: (i) adsorption, which offers high removal efficiency and rapid kinetics but entails significant costs and secondary-waste generation [4,5,6]; (ii) biotechnological treatments, which are environmentally benign yet struggle with highly concentrated nitroaromatics and often require expensive equipment [7,8]; and (iii) electrochemical processes, which are promising but remain largely limited to laboratory scale with few industrial deployments [9,10,11,12].

Given the limitations of traditional methods, advanced oxidation processes (AOPs) have emerged as a promising solution for the treatment of difficult-to-degrade organic substances, thanks to their ability to mineralize organic chemicals, minimize by-products, and shorten processing times [13,14,15,16,17]. Among AOPs, the sono-photo-Fenton (SPF) process, combined with zero-valent iron nanomaterials (nZVI), has demonstrated outstanding potential in treating persistent organic pollutants, such as TNT [18]. This method takes advantage of the resonance effect between ultrasound (sono), UV light (photo), and the Fenton reaction, producing strong oxidizing radicals, such as •OH, •H, •OOH, which are capable of decomposing and mineralizing organic substances more efficiently than each individual method (see Figure S1, Table S1 for a more detailed decomposition of TNT) [19,20,21]. The use of nZVI also helps to improve decomposition efficiency, limit waste sludge and increase the recovery and reuse of post-treatment materials, thanks to its strong reduction and adsorption ability, its low toxicity, and the reasonable cost of nZVI [22].

Although the SPF process combined with nZVI offers high processing efficiency, the energy consumption of the method is a key factor that directly affects its operating cost and feasibility in practical application [23,24]. Most previous studies have focused on optimizing processing efficiency without delving into energy efficiency. In fact, operating parameters such as ultrasonic (US) power, ultrasonic (US) time, UV lamp power, and UV illumination time have a great influence on the total energy consumption of the system [17,25]. Studies show that the energy efficiency of the processing system tends to increase as each factor (US power, US time, UV power, and UV time) increases. Ultrasound time is noted as a factor affecting energy efficiency, as extending this time will rapidly increase power consumption. The increase in ultrasonic power and UV illumination time also contributes significantly to the increase in energy consumption. The simultaneous combination of power and time factors can result in high energy consumption.

This study aims to determine optimal operating conditions for TNT-laden wastewater treatment that jointly maximizes contaminant removal while minimizing energy demand. By balancing ultrasound and UV inputs with catalyst use, the work aims to improve process efficacy, reduce operating costs, and lower the environmental footprint, thereby advancing scalable, sustainable remediation strategies and informing pilot-to-plant design choices for resource-efficient, regulatory-compliant deployment in water systems.

2. Experimental Section

2.1. Materials

2,4,6-Trinitrotoluene (TNT, 95% purity; Vietnam) was used as received. Nano zero-valent iron (nZVI) was synthesized by chemical reduction following Ref. [18]. Reagents included FeSO4·7H2O, FeCl3·6H2O, Na2S2O3·5H2O (all 99%, Xilong Scientific, Shantou, China), NaBH4, NaOH, H2SO4 (98%, Xilong Scientific, Shantou, China), and H2O2 (30% w/w, Analytical Reagent, Zhenjiang, China). Deionized water (18.2 MΩ·cm; Milli-Q) was used for all preparations. All chemicals were of analytical grade and were used without further purification.

2.2. Experimental Setup

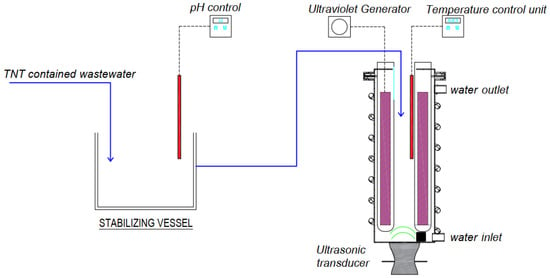

Figure 1 shows the experimental model of the sono-photo-Fenton method. The 1.0 L reactor is made from 1 mm thick Inox 304. The UV lamp is placed in a quartz tube to prevent direct contact with the solution. Up to four UV lamps can be arranged at the same time, with the power of each lamp being 10 W, up to a total of 40 W. At the bottom of the reactor, there is an ultrasonic transmitter with adjustable power from 10 to 100 W, with a frequency of 40 kHz. On the lid of the reactor, there are positions arranged to add H2O2 and catalyst materials, take samples for analysis, etc.

Figure 1.

Experimental model of the sono-photo-Fenton method. Note: 1—UV generator with wave-length 254 nm and length 200–250 mm; 2—air distribution head; and 3—ultrasonic transmitter (sono-transducer), frequency 40 kHz, power 60 W.

To enhance the stirring process in the model, an air distribution device is used, which has the effect of creating a convection air flow with a flow rate of 1 L/min with a foam size of 0.1–3 mm. At the same time, a cooling water pipeline system circulates around the model in order to maintain the temperature of the solution inside.

2.3. TNT Treatment by Sono-Photo-Fenton-like/nZVI

The effects of the ultrasonic transmission power, ultrasonic transmission time, UV lamp power, and illumination time of the UV lamp on TNT treatment efficiency and energy efficiency were investigated using the Design Expert 13 program, in which the response surface method (RSM) with a five-level central composite design (CCD) was utilized; the variables were encoded at five levels, as shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Elements for experimental design.

2.4. Analytical Method

The concentration of TNT in the post-treated wastewater solution is analyzed by HPLC high-performance liquid chromatography (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA, USA, 1100 Series) with Hypersil C18 column (200 × 4 mm); the dynamic phase of methanol and water was 65/35, the pressure was at 125 bar, and the pH = 7. The efficiency of TNT treatment is determined by the following formula:

where H is TNT treatment efficiency, and C0 and Ct are the concentration of TNT at the time before treatment and the final time (t = 20 min) (mg/L), respectively.

The electrical energy consumed per kg of TNT (or specific energy consumption) is determined by a formula, based on Dükkancı M’s research in 2018 [26]:

where E is specific energy consumption (kWh/kg), PUS, tUS, PUV, tUV are ultrasonic power, ultrasonic time, light power, and light time, respectively, as in Table 1 (W; minute), V is the volume of the treated TNT solution (L), and 1000 and 60 are to convert from W to kW and minute to hour

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Design of Experiments

The results of the experiments to study the efficiency of TNT treatment and energy usage in water environment by the sono-photo-Fenton process are presented in Table 2. After conducting all the experiments, the obtained results were entered into the software, regression analysis was performed on the data, and a linear equation was proposed for the treatment efficiency (H) and a two-factor interaction equation was proposed for the SEC (E) by the software to model the process. The analysis of variance (ANOVA) test was performed on the proposed model, with a p-value less than 0.05 indicating that the model is meaningful, and greater than 0.10 indicating that the model is meaningless and ignored.

Table 2.

Treatment efficiency and SEC of synthetic wastewater treatment system by sono-photo-Fenton-like process combined with nZVI.

The summarized model and the obtained ANOVA results are shown in Equations (3) and (4), and Table 3 and Table 4, respectively.

where A is the ultrasonic power (PUS), B is the ultrasonic broadcast time (tUS), C is the light power (PUV), and D is the illumination time (tUV).

Table 3.

ANOVA for TNT treatment efficiency-related model.

Table 4.

ANOVA for the model related to SEC.

The F-value of the model is 37.87 and the R2 and Adjusted R2 values are 0.9522 and 0.9270, respectively, indicating that the model is significant and can predict energy efficiency rather accurately. There is only a 0.01% chance that such a large F-value can occur due to interference. p-Values less than 0.0500 indicate that the elements of the model are meaningful. In this case, A, B, C, are D are the factors of the model that make sense. AB is the relationship between US power and US time, AC is the relationship between US–UV power, and CD is the relationship between UV power and UV time, which can be seen as a meaningful and understandable relationship. BC, BD, and AD are relationships between factors that are not meaningful, so their p-values being greater than 0.500 will not affect the significance of the whole model.

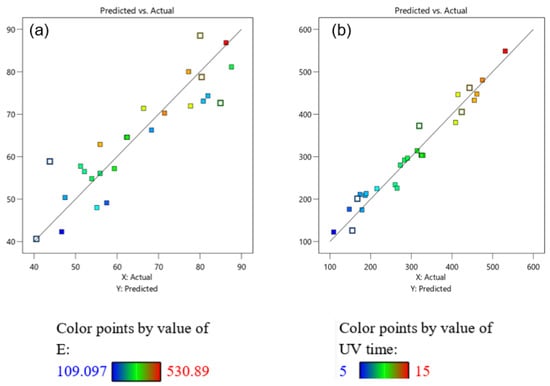

The results in Figure 2 show that the prediction value is close to the results obtained from the experiment.

Figure 2.

Comparison of values from the experiment (actual) and from the built model (predicted): (a) TNT treatment efficiency; (b) energy consumed.

3.2. Evaluate the Factors Affecting TNT Treatment Efficiency

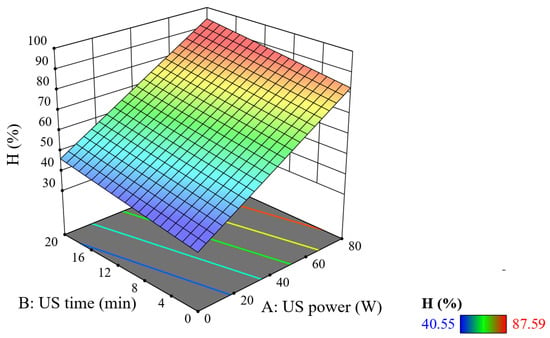

Figure 3 shows that when the ultrasonic power and ultrasonic time are increased, the treatment efficiency increases. In particular, the effect of US power on the treatment efficiency is more than that of US time. It can be seen that, at pH = 2.5, C0TNT = 50 mg/L, CnZVI = 2 mM, CH2O2 = 40 mM, PUV = 20 W, and tUV = 10 min; when the ultrasonic power is 0 W and US time is also 0 min, the treatment efficiency only reaches around 40.55% and 43.81%. At the same UV lamp power condition, if the ultrasonic power is increased to 40 W with a US time of 20 min, the treatment efficiency increases to 71.46%. However, at an ultrasonic power of 80 W and after 5 min of ultrasonic time, the treatment efficiency reaches 80.05%. It can be seen that the combination of high US power and low US time is more effective than the combination of low US power and long US time.

Figure 3.

Combined effect of US power and US time on TNT treatment efficiency (reaction time = 20 min, PUV = 20 W, and tUV = 10 min).

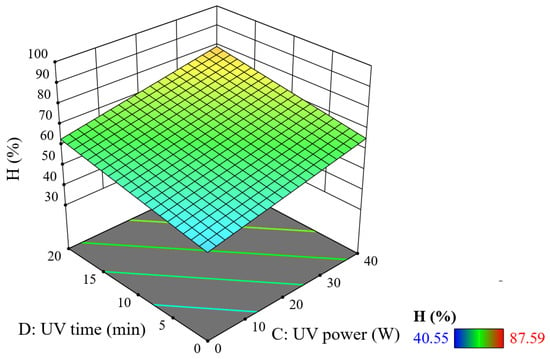

Figure 4 shows that when the UV illumination power and illumination time are increased simultaneously, the treatment efficiency increases significantly.

Figure 4.

Combined effect of UV lamp power and UV light time on TNT treatment efficiency (reaction time = 20 min, PUS = 40 W, and tUS = 10 min).

When using 10 W of UV power for 10 min, the TNT treatment efficiency is about 61%. At 40 W of power and a 10 min time, the efficiency reaches 68%, while at 10 W power and 20 min time, the efficiency reaches approximately 65%. Thus, when increasing the UV lamp power and UV time individually, the efficiency increases but is not significant when compared to the influence of ultrasonic power.

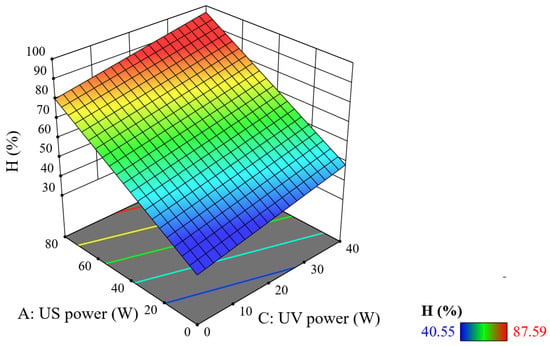

Figure 5 describes the conjugated effect of ultrasonic power (US) and ultraviolet light power (UV) on TNT treatment efficiency.

Figure 5.

Combined effect of US–UV power on TNT treatment efficiency (reaction time = 20 min, tUS = 10 min, and tUV = 10 min).

With the same US power, when the UV power is increased, the efficiency increases and similarly with the same UV power. More importantly, when the UV–US power increases simultaneously, the treatment efficiency also increases significantly. When increasing the ultrasonic power value from 0 W to 40 W, the TNT treatment efficiency increases from 45% to 68%, while when increasing the UV power from 0 to 40 W, the treatment efficiency only increases from 45% to 61%. Meanwhile, if you raise the US power to a maximum = 80 W, the treatment efficiency increases rapidly to 80%. Thus, the effect on the TNT treatment efficiency via US power is greater than that of UV light power. This also satisfies the overall equation that the model predicted—that the influence of the power factor US (A) is shown by a coefficient of 0.598812 greater than that of the UV power factor (C) of 0.403542. The TNT treatment efficiency is optimal when the ultrasonic power reaches 40–60 W and the light power reaches 30–40 W. The results coincide with the research of Nguyen Van Hoang et al. [18].

H = 20.0497 + 0.598812 × A + 0.568917 × B + 0.403542 × C + 0.68125 × D

In conclusion, after considering the influence of combined factors, the change in US power has the greatest effect on TNT treatment efficiency, while the effect of UV irradiation time is the least. The increase in ultrasound power combined with a reduction in ultrasound time has the potential to maintain a good TNT treatment efficiency while reducing energy use.

3.3. Evaluating the Factors Affecting SEC at the Laboratory Scale

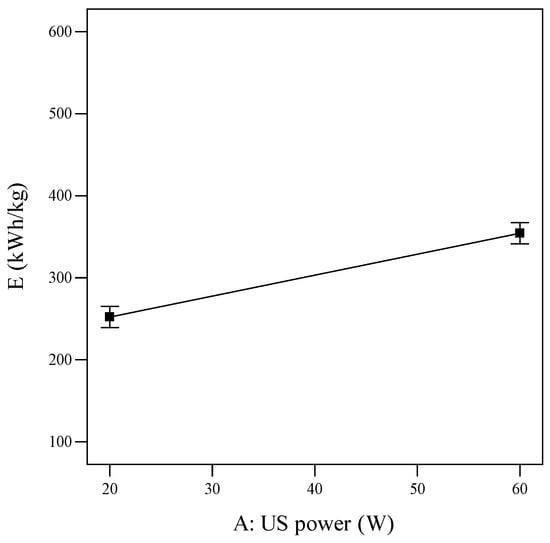

3.3.1. Effect of Single Factors

With the same amount of TNT treated, the greater the SEC value of the process, the more energy the system consumes, so this research aims to reduce this value but at the same time to maintain a high level of treatment efficiency. Overall, the SEC value of the treatment system increases as each factor increases (Figure 6 and Figure 7). The best SEC reaches 109.097 kWh/kg under the following conditions: a US power of 20 W, UV lamp power of 10 W, and ultrasonic and illumination time of 5 min.

Figure 6.

Single effect of US ultrasonic power on SEC (reaction time = 20 min, tUS = 10 min, PUV = 20 W, and tUV = 10 min).

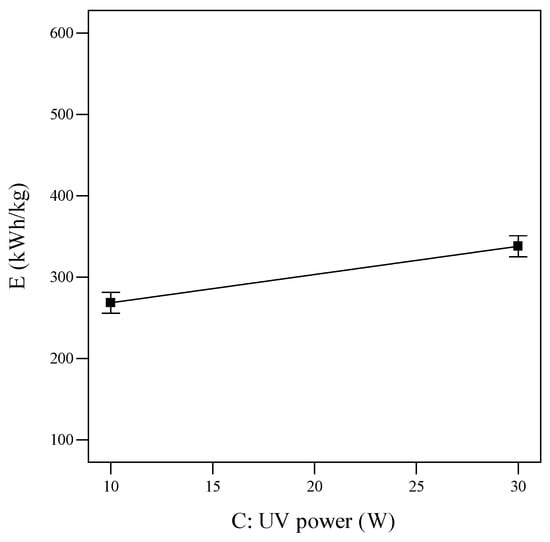

Figure 7.

Single effect of UV power on SEC (reaction time = 20 min, PUS = 40 W, tUS = 10 min, and tUV = 10 min).

The SEC value increased from 233.802 kWh/kg to 372.628 kWh/kg when the UV power increased from 0 to 40 W. The same increase was also seen upon raising the UV time from 0 to 20 min: the E value increased from 225.812 kWh/kg to 380.6 kWh/kg (Figure 8).

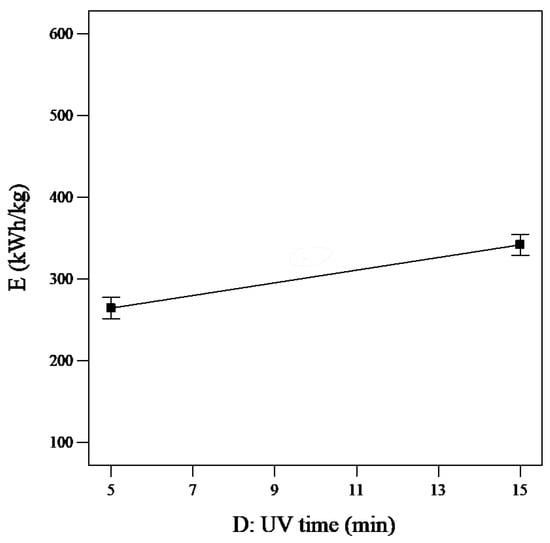

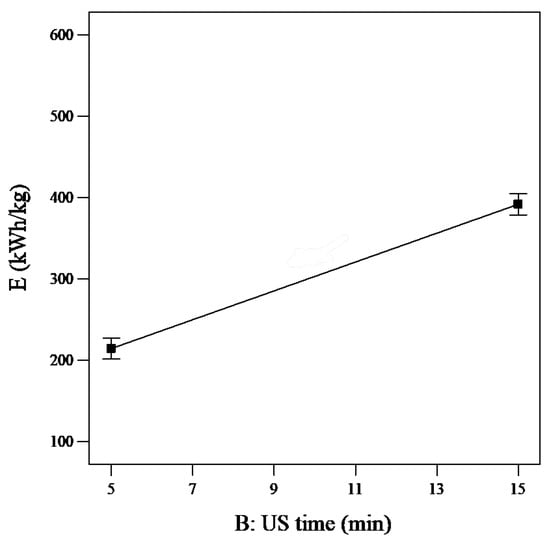

Figure 8.

Single effect of UV time on SEC (reaction time = 20 min, PUS = 40 W, tUS = 10 min, and PUV = 20 W).

The results in Figure 9 show that for the ultrasound time there is a rapid increase so it can be seen that the influence of this factor is the largest. The SEC value increased from 125 kWh/kg to approximately 480 kWh/kg when the US time increased from 0 to 20 min, which occurred faster than the increase in the UV time factor, shown in Figure 8 (from 225 kWh/kg to 380 kWh/kg during the same period).

Figure 9.

Single effect of US ultrasound time on SEC (reaction time = 20 min, PUS = 40 W, PUV = 20 W, and tUV = 10 min).

Therefore, restricting the US time will affect the SEC; specifically, reducing the ultrasound time will decrease the SEC value and result in reduced energy consumption.

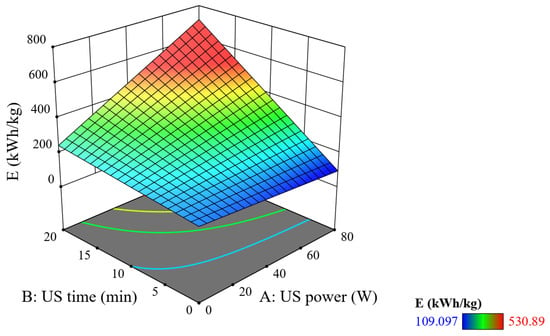

3.3.2. Effect of Combined Factors

Figure 10 depicts the combined effect of US power and US ultrasound time on SEC. It can be seen that when the US power is increased and the US time is increased, the E value tends to increase. However, the effect of the US time is much stronger than that of US power at the same increment of increase. From the time of transmitting the ultrasonic with a power of 20 W in 5 min, E reached a value of 199 kWh/kg. When the time is increased to 20 min, and the power remains the same at 20 W, E increases to 360 kWh/kg; when the power is increased to 80 W and the time is kept at the same time of 5 min, E only increases to 250 kWh/kg. Especially when both factors are increased simultaneously, the E value increases rapidly to nearly 800 kWh/kg, showing a resonant effect between ultrasonic power and time, leading to a lot of energy consumption. So, the combination of high US power and short US time can be implemented to reduce energy consumption.

Figure 10.

Combined effect of US power and US ultrasound time on SEC (reaction time = 20 min, PUV = 20 W, and tUV = 10 min).

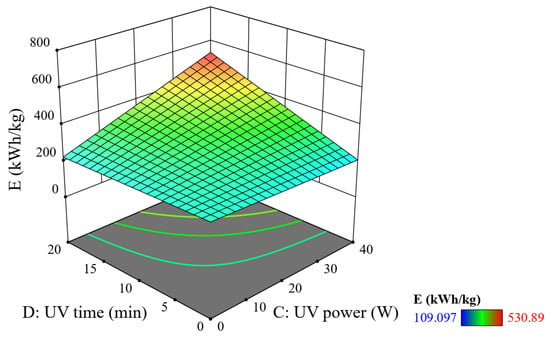

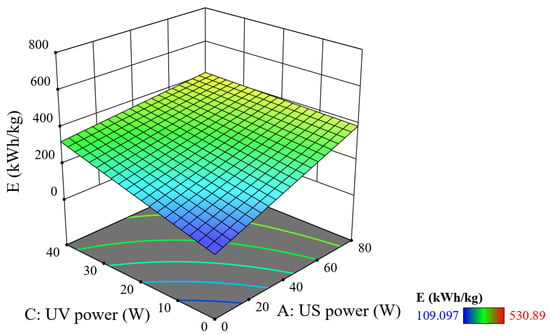

Comparing Figure 11 and Figure 12, it can be seen that the ultrasonic power and time factor have a greater effect on SEC than the UV illumination power and time factor. When emitting a 10 W UV lamp for 10 min, the SEC is about 260 kWh/kg. At 40 W power and a 5 min time, E reaches 290 kWh/kg, while at 10 W power and 20 min time, E reaches approximately 280 kWh/kg. Thus, when increasing the UV lamp power and UV time individually, the efficiency increases but not significant when compared to the influence of ultrasonic power. Increasing UV power improves the reaction rate but is not directly proportional to the energy produced due to the system’s limited light absorption capacity [19]. However, UV irradiation time still plays a significant role in increasing E. Research by Perumal A et al. (2023) shows that when the irradiation time is extended, the efficiency increases but also this especially increases energy consumption [27].

Figure 11.

Combined effect of UV lamp power and UV time on SEC (reaction time = 20 min, PUS = 40 W, and tUS = 10 min).

Figure 12.

Combined effect of US–UV power on SEC (reaction time = 20 min, tUS = 10 min, and tUV = 10 min).

There is less impact on overall SEC when changing the US–UV power at the same time than when changing the US/UV time individually or with a power–time combination. The plane shown in Figure 12 is quite flat, and the highest point occurs when the US–UV power is 80 W–40 W but the E value is only 409 kWh/kg, showing that when only changing the power without increasing the processing time, SEC does not increase by a lot, thereby saving energy consumption. It can be concluded that exposure time (both UV and US) is the core factor that determines energy consumption, rather than just increasing power.

3.4. Comparison Between the Energy-Optimized SPF Process and Similar Processes

3.4.1. Energy-Optimized Sono-Photo-Fenton-like Process Combined with nZVI Process (Optimized SPF)

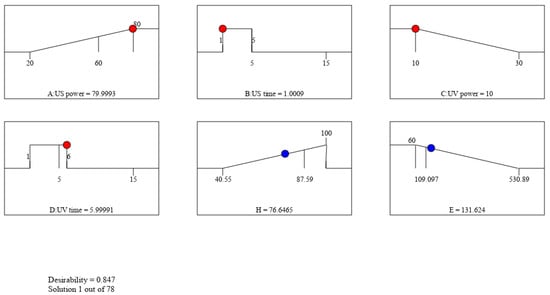

In order to determine the conditions to maximize the efficiency of TNT treatment and minimize the energy use from ultrasonic devices and UV lamps, this study uses Design Expert 13 to carry out the optimization. Figure 13 demonstrates 78 solutions given by the program. The most optimal process (with high H and low E) is chosen to have the following conditions: US power: 80 W; US time: 2 min; UV power: 10 W; and UV: 6 min

Figure 13.

Graphical representation of the optimal TNT treatment by SPF combined with nZVI given by Design Expert 13 software.

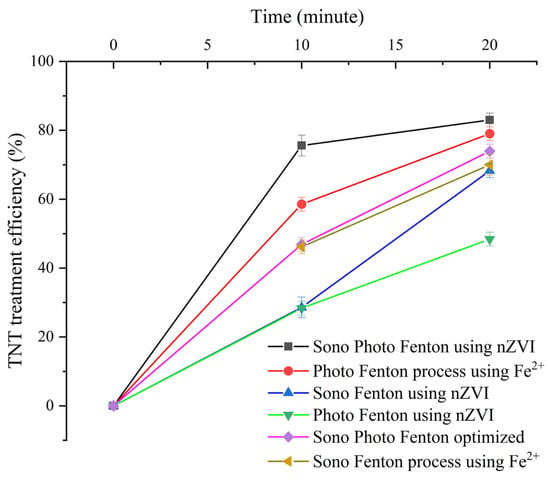

3.4.2. TNT Treatment Efficiencies by Energy-Optimized SPF Process Compared to Similar Processes

In terms of TNT treatment efficiency, the optimized SPF reached the highest value (86.2%), followed by the photo-Fenton process using Fe2+ (79.0%), then the optimized SPF (73.95%), and then the remaining processes (Figure 14). The performance of the optimized SPF, although lower than that of the photo-Fenton process using Fe2+, was negligible (about 5% difference). In terms of SEC, the optimized SPF reached 101.19 kWh/kg, lower than most processes and only higher than the value of the photo-Fenton method using Fe2+ (82.3 kWh/kg). However, with optimized SPF, the method of using nZVI material is reusable. This is the advantage of optimized SPF has over the photo-Fenton process using Fe2+.

Figure 14.

TNT treatment efficiency of Fenton-like processes.

Moreover, according to the research of N.V. Hoang et al., with the conditions of pH = 3, CH2O2 = 40 mM, CFe0 = 2 mM, C0TNT = 50 mg L−1, ultrasound = 40 kHz, UV = 254 nm, and PUS = 80 W, the TNT treatment efficiency reaches 80.4% after 20 min of reaction [18]. Even though the efficiency of TNT treatment is lower than that of the previous study, the SEC of the optimized SPF process is better than that of the previous study, at 746.27 kWh/kg (based on the calculations of this study).

Table 5 shows the energy consumption per mass for various Fenton-like processes. sono-Fenton methods consume the most energy, with process using nZVI at 594.64 kWh/kg and the process using Fe2+ at 461.05 kWh/kg. In contrast, photo-Fenton methods are more energy-efficient, especially the process using Fe2+ (82.3 kWh/kg). Optimized SPF significantly reduces energy usage compared to the unoptimized form.

Table 5.

SEC of Fenton-like processes.

3.4.3. Practical Treatment of TNT-Contaminated Wastewater

After the above comparison results, it was found that there were two methods that showed potential in terms of TNT treatment efficiency and good SEC, so the comparison of those two methods was carried out on actual wastewater, namely on acidic yellow wastewater taken from an industrial factory.

Both experiments used 1 L of yellow wastewater at pH = 2.5. Common experimental conditions include 40 mM of H2O2; 2 mM of Fe; US frequency = 40 kHz; UV wavelength = 254 nm; and temperature at 30–35 °C. The experimental conditions of the optimized SPF are 80 W ultrasonic power, 2 min of ultrasonic end time, 10 W of UV power, and 6 min illumination end time. The conditions for the photo-Fenton process using the Fe2+ reaction are as follows: a UV lamp with a power of 10 W and an illumination time of 20 min.

The results shown in Table 6 indicate that the TNT treatment efficiency of the sono-photo-Fenton process combined with the optimized anomalous material is higher than that of the photo-Fenton process using Fe2+, although the efficiency of both processes is low. This is because the yellow wastewater contains MNT, DNT, and TNT, all with different concentrations, affecting the ability to specifically treat TNT in yellow wastewater. In addition, because in the yellow wastewater environment the color is much higher than that of synthetic wastewater, which contains only TNT, the UV light is more obstructed, reducing the effectiveness of the UV factor, so the treatment efficiency of the photo-Fenton process is worse than that of the process with both ultrasonic and UV light elements [28]. Furthermore, the SEC of the optimized SPF reached 252.60 kWh/kg, better than that of the photo-Fenton process using Fe2+ (380.77 kWh/kg). The SEC value of the two processes is so large because the efficiency of TNT treatment is much lower than that of the experiment using synthetic wastewater. Thus, it can be seen that although the treatment efficiency of TNT in acidic yellow wastewater by optimized SPF is not high, it is more effective than the photo-Fenton method using Fe2+, and initially minimizes the amount of electricity/energy used in the sono-photo-Fenton-like processes combined with nZVI [7,29].

Table 6.

Comparison of the efficiency of yellow wastewater treatment between the energy-optimized SPF process and the PF process using Fe2+.

4. Conclusions

This study successfully evaluated the effects of the operating parameters using the surface response method (RSM) and determined the optimal conditions for the sono-photo-Fenton-like process combined with zero-valent iron (nZVI) to simultaneously achieve high TNT treatment efficiency and good energy efficiency. These optimal conditions include a US power of 80 W, a US time of 2 min, a UV power of 10 W, and a UV time of 6 min. Under these conditions, the process was confirmed to achieve a TNT treatment efficiency of 73.95% and energy consumption of 101.19 kWh/kg after 20 min of reaction with an initial TNT concentration of 50 mg/L. Compared to other Fenton-like methods, the optimal SPF process exhibits a significantly improved TNT treatment efficiency and energy efficiency. Although the treatment efficiency of the optimal SPF method is not yet superior to that of the photo-Fenton process using Fe2+, it demonstrates significant advantages in terms of iron recovery and sustainability. When applying the optimal SPF process to treat acidic yellow wastewater, the results showed better TNT treatment efficiency than the photo-Fenton method under the same conditions, while also achieving an energy consumption of 252.60 kWh/kg. This shows that the method has initially reduced the amount of electricity/energy used.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/w18010037/s1, Figure S1. GC chromatogram (a) initial; (b) after 15 min; (c) after treatment process; Table S1. MS spectra of intermediate products formed during TNT degradation.

Author Contributions

H.V.N. (Hoang Van Nguyen): Writing—original draft, Methodology, Resources, Data curation, and Investigation. T.S.P.: Writing—review and editing, Validation, Data curation, Formal analysis, Supervision, and Conceptualization. H.V.N. (Huong Van Nguyen): Data curation, Methodology, and Writing—review and editing. W.C.: Writing—review and editing, Validation, and Resources. W.C.: Resources, Supervision, and Writing—review and editing. D.D.L.: Data curation, Methodology, and Writing—review and editing. D.D.N.: Conceptualization, Writing—review and editing, Validation, Resources, and Supervision. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Lamba, J.; Bhardwaj, D.; Anand, S.; Dutta, J.; Rai, P.K. Biodegradation of 2,4,6-trinitrotoluene (TNT) by the microbes and their synergistic interactions. In Harnessing Microbial Potential for Multifarious Applications; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2024; pp. 177–202. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, G.C. TNT: Trinitrotoluenes and Mono-and Dinitrotoluenes, Their Manufacture and Properties; D. Van Nostrand Company: New York, NY, USA, 1918. [Google Scholar]

- Dorsey, A.; Hodes, C.S.; Richter-Torres, P. Toxicological Profile for 2, 4, 6-Trinitrotoluene; ATSDR: Washington, DC, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, D.; Zhang, Y.; Lv, F.; Chu, P.K.; Shang, J. Removal of organic materials from TNT red water by Bamboo Charcoal adsorption. Chem. Eng. J. 2012, 193, 39–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todde, G.; Jha, S.K.; Subramanian, G.; Shukla, M.K. Adsorption of TNT, DNAN, NTO, FOX7, and NQ onto cellulose, chitin, and cellulose triacetate. Insights from Density Functional Theory calculations. Surf. Sci. 2018, 668, 54–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, H.; Zhang, B.; Xu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Huo, J.; Zhang, L.; Chang, G. A simple approach to prepare isoxazoline-based porous polymer for the highly effective adsorption of 2,4,6-trinitrotoluene (TNT): Catalyst-free click polymerization between an in situ generated nitrile oxide with polybutadiene. Chem. Eng. J. 2020, 393, 124674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Ye, Z.; Zhang, M.; Bai, X. Degradation of 2,4,6-trinitrotoluene (TNT) by immobilized microorganism-biological filter. Process Biochem. 2010, 45, 993–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kao, C.-M.; Lin, B.-H.; Chen, S.-C.; Wei, S.-F.; Chen, C.-C.; Yao, C.-L.; Chien, C.-C. Biodegradation of trinitrotoluene (TNT) by indigenous microorganisms from TNT-contaminated soil, and their application in TNT bioremediation. Bioremediation J. 2016, 20, 165–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szopińska, M.; Prasuła, P.; Baran, P.; Kaczmarzyk, I.; Pierpaoli, M.; Nawała, J.; Szala, M.; Fudala-Książek, S.; Kamieńska-Duda, A.; Dettlaff, A. Efficient removal of 2,4,6-trinitrotoluene (TNT) from industrial/military wastewater using anodic oxidation on boron-doped diamond electrodes. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 4802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayoub, K.; Van Hullebusch, E.D.; Cassir, M.; Bermond, A. Application of advanced oxidation processes for TNT removal: A review. J. Hazard. Mater. 2010, 178, 10–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grigoriants, I.; Markovsky, B.; Persky, R.; Perelshtein, I.; Gedanken, A.; Aurbach, D.; Filanovsky, B.; Bourenko, T.; Felner, I. Electrochemical reduction of trinitrotoluene on core–shell tin–carbon electrodes. Electrochim. Acta 2008, 54, 690–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodgers, J.D.; Bunce, N.J. Electrochemical treatment of 2, 4, 6-trinitrotoluene and related compounds. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2001, 35, 406–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nidheesh, P.V.; Couras, C.; Karim, A.V.; Nadais, H. A review of integrated advanced oxidation processes and biological processes for organic pollutant removal. Chem. Eng. Commun. 2022, 209, 390–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, T.H.; Zhang, Z.Z.; Liu, Y.; Zou, L.H. Recent Progress in Catalytically Driven Advanced Oxidation Processes for Wastewater Treatment. Catalysts 2025, 15, 761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litter, M.I. Introduction to photochemical advanced oxidation processes for water treatment. In Environmental Photochemistry Part II; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2005; pp. 325–366. [Google Scholar]

- Lucas, M.S.; Teixeira, A.R.; Jorge, N.; Peres, J.A. Industrial Wastewater Treatment by Coagulation–Flocculation and Advanced Oxidation Processes: A Review. Water 2025, 17, 1934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferre, M.; Moya-Llamas, M.J.; Dominguez, E.; Ortuño, N.; Prats, D. Advanced Oxidation Processes and Adsorption Technologies for the Removal of Organic Azo Compounds: UV, H2O2, and GAC. Water 2025, 17, 212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Nguyen, H.; Pham, S.T.; Vu, T.N.; Van Nguyen, H.; La, D.D. Effective treatment of 2, 4, 6-trinitrotoluene from aqueous media using a sono–photo-Fenton-like process with a zero-valent iron nanoparticle (nZVI) catalyst. RSC Adv. 2024, 14, 23720–23729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moradi, M.; Elahinia, A.; Vasseghian, Y.; Dragoi, E.-N.; Omidi, F.; Khaneghah, A.M. A review on pollutants removal by Sono-photo-Fenton processes. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2020, 8, 104330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.-L.; Sun, J.-H.; Liu, B.; Chen, Y.-N.; Feng, W. Fabrication of MoS2@Fe3O4 Magnetic Catalysts with Photo-Fenton Reaction for Enhancing Tetracycline Degradation. Water 2025, 17, 235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shukla, T.L.; Duranceau, S.J. Comparing Hydrogen Peroxide and Sodium Perborate Ultraviolet Advanced Oxidation Processes for 1,4-Dioxane Removal from Tertiary Wastewater Effluent. Water 2023, 15, 1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleh, R.; Taufik, A. Degradation of methylene blue and congo-red dyes using Fenton, photo-Fenton, sono-Fenton, and sonophoto-Fenton methods in the presence of iron (II, III) oxide/zinc oxide/graphene (Fe3O4/ZnO/graphene) composites. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2019, 210, 563–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Ye, Y.; Xu, L.; Gao, T.; Zhong, A.; Song, Z. Recent advances in nanoscale zero-valent iron (nZVI)-based advanced oxidation processes (AOPs): Applications, mechanisms, and future prospects. Nanomaterials 2023, 13, 2830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.; Zhu, L.; Yu, S.; Li, G.; Wang, D. The synergistic effect of adsorption and Fenton oxidation for organic pollutants in water remediation: An overview. RSC Adv. 2024, 14, 33489–33511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keen, O.; Bolton, J.; Litter, M.; Bircher, K.; Oppenländer, T. Standard reporting of electrical energy per order (E EO) for UV/H2O2 reactors (IUPAC technical report). Pure Appl. Chem. 2018, 90, 1487–1499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dükkancı, M. Sono-photo-Fenton oxidation of bisphenol-A over a LaFeO3 perovskite catalyst. Ultrason. Sonochem 2018, 40, 110–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perumal, A.; Yesuf, M.B.; Govindarajan, R.; Niju, S.; Arun, C.; Periyasamy, S.; Pandiyarajan, T.; Alemayehu, E. Photo-Alternating Current-Electro-Fenton Process for Pollutant Removal and Energy Usage from Industrial Wastewater: Response Surface Approach Optimization of Operational Parameters. ChemElectroChem 2023, 10, e202300086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseini, M.; Kahkha, M.R.R.; Fakhri, A.; Tahami, S.; Lariche, M.J. Degradation of macrolide antibiotics via sono or photo coupled with Fenton methods in the presence of ZnS quantum dots decorated SnO2 nanosheets. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B Biol. 2018, 185, 24–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, E.N.; Da Silva, F.T.; De Paiva, T.C.B. Ecotoxicological evaluation of wastewater from 2.4. 6-TNT production. J. Environ. Sci. Health Part A 2012, 47, 184–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.