Abstract

The Tidal River Management (TRM) approach plays a significant role in enhancing diversified services of the ecosystem in the ecosystem of rivers affected by tides and their floodplains and reducing coastal hazards in southwest Bangladesh. The main aim of this investigation was to complete the development of the Sustainability Index for Tidal River Management (SITRM) and to assess the sustainability of TRM in coastal regions. In the first stage, the key components along with indicators of the Sustainability Index of TRM were identified to address problems of the coast. In the second stage of this study, a five-point Likert scale was applied to gather responses from key informants. In addition, it includes direct field observations and consultation meetings to collect information concerning the SITRM indicators. The results showed that the framework of SITRM included several important indicators to solve coastal problems, including drainage congestion, waterlogging, rising sea levels, new land formation, compensation, alternative livelihoods, and terrestrial biodiversity as indicators. It also established standard tidal flow thresholds for the Hari–Teka River at 600 m3/s (maximum) and 250 m3/s (minimum) for high tide and 550 m3/s (maximum) and 200 m3/s (minimum) for low tide. Moreover, the results showed that the Canadian Water Sustainability Index (CWSI), West Java Water Sustainability Index (WJWSI), and Water Poverty Index (WPI) are suitable for overcoming coastal problems and climate change issues.

1. Introduction

The southwest coastal region of Bangladesh, nestled within the sprawling Ganges–Brahmaputra–Meghna (GBM) delta, stands as a testament to the enduring geological forces that have shaped our planet over millions of years. Originating from the collision of the Indian Plate and the development of the Himalayas approximately 100 million years ago, this delta is a dynamic, ever-changing landscape. Its constant metamorphosis, driven by the relentless processes of river sedimentation and erosion, has bestowed upon it a unique and diverse geographical and hydro-morphological character [1,2,3]. However, it is this very dynamism that also exposes the region to a suite of formidable challenges, notably the relentless impact of climate change. From the devastation of extreme cyclones to the historical records of pluvial floods in the 1950s, 1980s, and 2000s, the region faces rising sea levels and the persistent threat of saline intrusion [3,4,5,6].

To address these challenges and set the stage for sustainable development, the southwest coastal area has undergone significant transformations. In the wake of the Ganges-Kobadak Irrigation Project during the 1960s, ambitious engineering structural development projects were implemented, including the construction of coastal embankments featuring 139 polders. These endeavors were launched with the dual purpose of bolstering food security in the region. However, these initiatives came with their own set of consequences, including riverbed sedimentation, waterlogging issues spanning from the 1980s to the 2020s, and heightened risks of saline intrusion [1,3]. In response to these challenges and building upon their traditional knowledge of water management dating back to the British era, local communities introduced Tidal River Management (TRM) as a pragmatic solution. TRM emerged as a holistic approach to mitigate these issues, ultimately striving to achieve water sustainability in the fragile ecosystem of the lower GBM delta. Early TRM efforts, particularly along the Hamkura River alongside Beel Dakatia and the Hari–Teka River in conjunction with Beel Bhaina, paved the way for the replication of several TRM initiatives across the region [3].

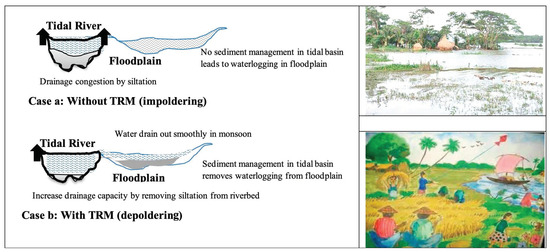

Figure 1 presents case (a), in which the impoldering by the embankment along the river (without TRM) creates drainage congestion by siltation on riverbeds; this situation reduces the river’s navigability and generates waterlogging, which damages agriculture, biodiversity, vegetation, settlement, etc. (picture a). In case (b), the temporary desoldering of the embankment (4 to 6 years) occurs by connecting the river to a tidal basin (with TRM), allowing the smooth drainage of excess water during monsoons and sediment deposition in the tidal basin. In addition, this situation develops the river’s navigability, which improves the ecosystem of the tidal river and floodplain (illustrated in picture b) within the polder system.

This study assesses the literature related to TRM and water sustainability indices to identify crucial research gaps that underpin the significance of our research. This study delves into several seminal studies that have shaped the discourse in this field. For instance, Gain et al. [5] introduced a comprehensive set of 23 social–ecological system (SES) indicators, encompassing biophysical factors, discharge, river width and depth, sediment deposition, sea level rises, flood agricultural production, social monitoring, governmental organization (GO) and non-governmental organization (NGO) involvement, social capital, and leadership, among others. These indicators were created to evaluate the long-term sustainability of the southwest coastal area, with notable variations in SES performance observed across different TRM sites, and the examples include locations Beel Bhaina TRM, Beel Pakhimara TRM, and Beel East Khukshia TRM. The main finding of this study was the identification of variations in SES performance across different TRM sites, highlighting the need for tailored approaches to achieve sustainability. Similarly, Mutahara [7] contributed to the field by introducing indicators covering river capacity, waterlogging, agriculture, land use change, salinity, income, migration, conflict and cooperation, and compensation, all of which are pivotal for the sustainability of TRM within the adaptive delta management of the Bangladesh delta. Mutahara’s research findings underscored TRM’s positive impact on river capacity, the elimination of waterlogging, alterations in land use change patterns, and advancements in the agricultural system, notably in large-scale agro-fishery mixed cultivation with vegetable production. The primary takeaway from this study was the evidence of TRM’s effectiveness in enhancing river capacity, reducing waterlogging, and positively influencing land use change and agricultural systems.

In this regard, Mutahara et al. [7] developed the Water Poverty Index (WPI). This index, comprising 12 indicators, including per capita annual water resources, access to clean water and sanitation, GDP index, literacy rates, and agricultural use, aimed to assess water crisis levels. While informative, these indices did not adequately account for coastal issues under the polder system, the challenges posed by climate change, or the services of the ecosystem of a Tidal River and its adjacent floodplain. The primary finding was the development of a water crisis assessment tool but with limitations in addressing coastal and deltaic challenges comprehensively.

Furthermore, the West Java Water Sustainability Index (WJWSI) was introduced by Juwana et al. [8], evaluating the sustainability of water resources based on 13 key indicators, encompassing availability and demand, coverage and finance, sanitation and health impact, education, and poverty. Their comparative study of catchments in West Java highlighted poor sustainability, indicating a pressing need for action to enhance water availability. Additionally, as presented by Attari et al. [9], the CWSI, which stands for Canadian Water Sustainability Index, incorporates 15 indicators to measure water sustainability but does not address coastal and deltaic challenges adequately. The key finding from these studies was the assessment of water resource sustainability status in specific regions, indicating the need for interventions to enhance sustainability. In addition, Ionus et al. [10] employed the Water Sustainability Index (WSI) using the pressure-state-response (PSR) model to assess water sustainability, which resulted in an intermediate sustainability score. However, these studies collectively reveal critical research gaps, including the omission of coastal problems under the polder system, insufficient consideration of climate change impacts, and the inadequate incorporation of ecosystem services originating from a tidal river and a floodplain ecological system. Additionally, there are only a few dedicated frameworks to measure the endurance of TRM in shoreline areas. By examining these studies and identifying these research gaps, our study sets the stage for the development and application of the Stakeholder-Integrated Transportation Risk Management (SITRM) framework, which addresses these critical deficiencies and offers a comprehensive approach to assess and enhance the sustainability of TRM in coastal regions. The selection of the SITRM framework as the focal point of this study is grounded in both scientific and practical considerations. From a scientific standpoint, the SITRM framework has been designed to address the intricate and dynamic challenges specific to the coastal area in the southwest of Bangladesh. The scientific rationale for its adoption lies in its ability to integrate multidisciplinary insights and expertise, drawing from fields such as environmental science, hydrology, ecosystem services, and stakeholder engagement. By doing so, the SITRM framework offers a holistic approach to transportation risk management, accounting for the complex interplay of environmental factors, societal needs, and ecological services within this unique deltaic environment. Moreover, the framework’s development is underpinned by extensive research, including a thorough review of the existing literature and empirical data, ensuring that it aligns with the latest scientific understanding of the region’s dynamics.

Figure 1.

(a) Tidal river–floodplain ecosystem without TRM event generates waterlogging. (b) Tidal river–floodplain ecosystem with TRM event improves agricultural production. (Source: adapted from Masud [11].)

From a practical standpoint, the adoption of the SITRM framework addresses pressing real-world challenges faced by coastal communities in Bangladesh. The region’s vulnerability to climate change-induced events such as cyclones, floods, and sea level rises necessitates robust risk management strategies. SITRM provides a systematic tool for decision-makers, policymakers, and indigenous communities to assess, monitor, and enhance the resilience of transportation infrastructure. Moreover, the framework’s emphasis on stakeholder engagement ensures that local knowledge and priorities are integrated into risk management strategies, promoting community ownership and sustainability. By addressing the practical need for effective risk management in the context of coastal Bangladesh, the SITRM framework not only contributes to the well-being of local communities but also has broader implications for deltaic regions worldwide facing similar challenges. Therefore, incorporating the SITRM framework into this study’s endeavors allows us to connect scientific exploration and practical solutions, ultimately working toward a more resilient and sustainable future in Bangladesh’s southwest coastal zone. Addressing these research gaps, the present study evolves the SITRM framework based on the services of the ecosystem of the coastal river–floodplain environment [12]. Therefore, the primary goal of this research is to complete indicators and components for developing the SITRM framework to monitor water sustainability and improve SES connections in coastal communities by addressing the following research questions:

- i.

- How is the collection of components and key indicators of SITRM finalized?

- ii.

- What is the SITRM approach to evaluate TRM sustainability?

Important Indices for Water Sustainability

Water sustainability is a multifaceted concern that has garnered significant attention in the academic and policy realms. To assess and promote water sustainability, researchers and policymakers have developed various indices tailored to address distinct dimensions of this complex issue. Notable among these indices are the WPI, the WSI, the CWSI, and the WJWSI, each offering unique insights and methodologies.

The WPI, pioneered by Koirala et al. [13], places a central focus on poverty alleviation through a comprehensive evaluation of stress and limitations in water. This index establishes a dynamic connection between poverty and water accessibility in diverse regions, providing a comprehensive perspective on the intertwined challenges of socioeconomic well-being and water resource management. By actively quantifying the relationship between poverty and water availability, the WPI offers valuable insights into the broader context of water sustainability [3,13].

The CWSI, first introduced in 2007 by the Canadian Policy Research Initiative, is designed to advance water sustainability efforts by addressing the needs of both urban and rural populations. It places a strong emphasis on providing access to fresh water for urban dwellers grappling with wastewater management challenges while also recognizing the vital requirements of remote and indigenous communities. Through its holistic approach, the CWSI strives to promote equitable water resource management and sustainability across a wide spectrum of settings, underlining the importance of inclusive and comprehensive water policies [3,9].

The WSI primarily seeks to mitigate sewage pollution, advance the conservation of natural resources, and enhance water-related policies. By focusing on the reduction in sewage pollution and the sustainable management of watersheds, the WSI contributes to the broader goals of ecological integrity and sustainable water resource management [14].

Despite the valuable insights provided by these indices, it is essential to recognize that many of them are region-specific and developed to address the unique water challenges faced by specific localities. However, a common limitation of these existing indices is their limited consideration of crucial factors specific to coastal regions, such as the complex dynamics of tidal basins, water resource management within the polder system, sedimentation in riverbeds, waterlogging issues in floodplains, and the growing threats posed by rising sea levels resulting from climate change [3,15,16].

Acknowledging these critical gaps in existing indices, this study endeavors to provide a comprehensive solution by introducing the SITRM framework. SITRM adopts an integrative approach that considers the services of the ecosystem of the tidal river–floodplain environment and the intricate social and ecological relations of coastal communities. By addressing these coastal-specific challenges, SITRM aims to advance water sustainability in the lower GBM delta of Bangladesh and serves as a model with broader implications for other coastal regions facing similar complex water management issues.

The study is structured as follows: Section 2 explains the research methodology. In Section 3, the results of the study and the TRM Sustainability Index are presented. Section 4 gives the analysis of the questionnaire. In Section 5, the SITRM index is compared with other related indicators. Finally, at the end of Section 5 is devoted to conclusions and suggestions for future research and policy recommendations.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Zone

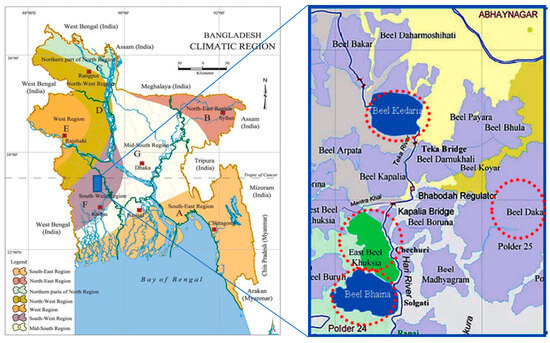

The delta of the GBM in the districts of Jashore, Khulna, and Satkhira of southwest Bangladesh are problematic and active deltas. The polder system of CEP is disconnected downstream from the upstream river of this region and has hampered delta formation and the natural process of sediment management between the tidal river and the floodplain [1,3]. Therefore, several rivers of this region, including Hamkura, Sholgati, Shalikha, Hari, Teka, Sree, Bhadra, Betna, Kobadak, Moricchap, etc., were on the verge of drying up due to sedimentation. In addition, Beel Dakatia, Beel Bhaina, Beel Khukshia, Beel Baruna, Beel Madhugram, etc., were severely affected by waterlogging due to the consequences of CEP. Later, several TRMs (Figure 2) were provided in this region to rescue coastal communities when facing these problems [7,17]. Therefore, this study selected the Jashore, Khulna, and Satkhira districts positioned between 21°36′ and 23°47′ north latitude and 88°40′ and 89°50′ east longitude. The population density of these districts was 703 people per km2 in 2011 (1060, 528, and 520 people separately) [18] (The data was accessed https://bbs.gov.bd/site/page/47856ad0-7e1c-4aab-bd78-892733bc06eb/Population-and-Housing-Census accessed on 7 October 2022). The yearly population growth rate in Bangladesh was 1.46 [19] (The data was accessed https://bbs.gov.bd/site/page/47856ad0-7e1c-4aab-bd78-892733bc06eb/Population-and-Housing-Census accessed on 7 October 2022) and 1.22 in 2022 [18]. Furthermore, in 2022, the national average for access to safe drinking water (tubewell) and toilet facilities (safe disposal) and the literacy rate were 86, 56, and 74.66, respectively. For only the Khulna did the figures stand at 87, 55, and 75.02, respectively, for the same year. Moreover, the mobile phone user and Internet user rates were 55.89 and 30.68 for the nation and 55.91 and 27.54 for the Khulna district in 2022 [18]. In addition, this study included ecosystem services of tidal rivers–floodplains of this region to select the SITRM components and indicators to mitigate coastal problems and achieve water sustainability.

Figure 2.

The study area of the southwest region (F) of Bangladesh [20].

Examples of TRM beels such as Beel Bhaina, Beel East Khukshia, Beel Dakatia, and Beel Kaderia of the Hari–Teka–Bhadra catchment area of the southwestern part of Bangladesh are illustrated in Figure 2.

2.2. Selecting SITRM Components and Indicators

This study collected secondary data from GO and NGO reports and journal articles to identify the preliminary set of components and indicators for the SITRM. These data were collected by reviewing the extensive literature from 2014 to 2017. The main focus of this study is on three subjects, including (a) concepts, principles, and guidance on the stainable management of water resources; (b) reasons and objectives of river management; and (c) indicators that have already been utilized to evaluate the maintaining the balance of water ecosystems [3]. In addition, it reviewed the WPI [13], WSI [10], WJWSI [8], and CWSI [9] for this purpose (Table A1). Then, it included a direct field observation method and four consultation meetings for the revisions of the initial metrics and elements of SITRM. In the direct observation method, the researcher went into the field and directly observed the situation of TRM (after the TRM event and during the TRM event) and collected information. The study conducted several discussions with local people (e.g., farmers, fishermen, day laborers, boatmen, shopkeepers, teachers, and members of CBOs and NGOs) to understand the ecosystem of tidal rivers and floodplains in different seasons around the year (from 2014 to 2017). The researchers observed key components and indicators (e.g., tidal flow, capacity of drainage, saturated soil, crop production, terrestrial biodiversity, land formation, and compensation) of SITRM. These indicators are directly related to the geophysical setting, hydro-morphological characters, and SES of the southwest coastal region (Jashore, Khulna, and Satkhira districts), hydro-morphological characters, and SES of the southwest coastal region (Jashore, Khulna, and Satkhira districts).

The meetings were held at the university level (Khulna University in Bangladesh and Hasselt University in Belgium) and college level (Bhabadah College in the Jashore district and Madhugram College in the Khulna district) in 2015 and 2016 to gather expert opinions. The study included members of the water management committee, the Beel Committee, the Pani Committee, the local government, farmers, journalists, and NGO consultants and practitioners who had more than 10 years of experience in water resource management. Moreover, it invited teachers from the college and university levels and researchers who were directly or indirectly involved in the TRM project (as key informants for interviews) to the consultation meeting to detect the potential SITRM components and indicators. It considered ecosystem services such as provisioning services (e.g., tidal flow, terrestrial biodiversity, and crop production) and regulating services (e.g., drainage capacity, sedimentation, and water quality). In addition, support services (e.g., land formation and reduction in waterlogging) and cultural services (e.g., awareness and coordination and crop compensation) were included in the revisions [3]. This study followed purposive sampling to select target people for the consultation meeting. The number of participants was 8 for Hasselt University in Belgium, 10 for Khulna University in Bangladesh, 12 for Bhabadah College in the Jashore district, and 15 for Madhugram College in the Khulna district of Bangladesh. Meetings were hold one time (2 to 3 h) in each place. The meetings were not recorded, but one enumerator was engaged to write down important notes for each meeting.

2.3. Finalizing SITRM Framework

This study followed purposive sampling and required 10 to 20 years of practical and professional experience in the field of water resource management on the part of stakeholders for them to be selected as key informants. In addition, they were tangibly skilled in geophysical settings, SES, and the hydro-morphological characteristics of the tidal river and floodplain ecosystem in the coastal southwest. Therefore, their expert opinions can be the deciding factors for this framework. The study interviewed 30 key informants (KIIs) (see Table A14 for the list of key informants) to collect expert opinions from local- and national-level stakeholders [12]. High government officials were involved as key informants (Section 3.2) to finalize the initial set of components and indicators and fit the standard threshold (maximum and minimum) values of the indicators and sub-indicators. In the first and second round of the opinion survey, 30 and 20 KIIs were interviewed, respectively. This study applied a 5-point Likert scale [21] to assess the opinions of experts. These five points are (1) Strongly disagree; (2) Disagree; (3) Neutral; (4) Agree; and (5) Strongly agree (Table A2). In this study, we applied a cut-off of 70% agreement on the part of respondents to evolve SITRM. Any component, indicator, or threshold value that surpasses this cut-off percentage (70%) is therefore approved; 51% to 69% advance to the next round, and respondents who agree with less than 51% of the questions are eliminated from the SITRM for the subsequent round.

The SITRM framework can calculate a score for every indicator and sub-indicator (S) from the observed threshold value by applying Equations (1) and (2) [22]. To measure the score, Equation (1) was applied where the preferable threshold value (a) was greater than the not-preferable threshold value (b), and Equation (2) was applied where the preferable value (a) was lesser than the not-preferable value (b).

S = (Vobs − Vmin)/(Vmax − Vmin) × Sf

In this formula, a > b

where a < b

S = Sf − (Vobs − Vmin)/(Vmax − Vmin) × Sf

Here, Sf = the fixed score for a sub-indicator or indicator;

Vobs = the observed threshold value for a sub-indicator or indicator;

Vmin = the minimum standard threshold value for a sub-indicator or indicator;

Vmax = the maximum standard threshold value for an indicator or sub-indicator.

3. Results

3.1. Initial Setting of SITRM Components and Indicators

In order to define prospective components and indicators with their threshold values, the SITRM index’s innovative approach relies on the services of the ecosystem provided by the ecosystem of tidal rivers and floodplains (SES of a coastal area) [3]. Initially, the SITRM comprised 6 components and 20 corresponding indicators (Table A4) to assess the impacts of TRM in the field of sustainability [3]. The study rearranged the indicators and elements of the SITRM framework from expert comments of university/college teachers and senior researchers. Three components, including environmental challenges, resilience, and floodplain ecosystem, have been merged into two components including sediment management and environment. Then, the indices are reorganized based on these two new components. Therefore, the number of components was five in Figure 3.

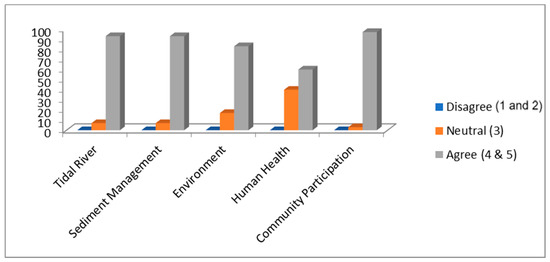

Figure 3.

Expert opinions regarding components of SITRM in the first round. (Source: the findings of this study.)

The component of community participation includes the maximum six indicators (i.e., coordination, consciousness and compensation, LUC, employment, rotation of TRM beel, and governance of water). The components of the tidal river and human health both comprise the minimum two indicators (i.e., water availability and drainage capacity as well as health impact and sanitation, respectively). In addition, the component of environmental challenges, resilience, and floodplain ecosystem involves three, three, and four indicators, respectively. Sedimentation, sea level rises, and waterlogging, as well as agricultural productivity, forest and new land formation, water quality, salinity, biodiversity, and the movement of climate refugees, are indications of these components. The index illustrated two types of values for the matching range of an indicator (i.e., 0 to 1 or 0 to 100), as well as an ongoing re-scaling technique to obtain sub-index values for the indicators of SITRM. The indicators of SITRM for biodiversity, capacity of drainage, rotation of TRM beel, and governance of water set the minimum (0) and maximum (1) values using assumptions.

3.2. Finalization of SITRM Components and Indicators

Figure 3 shows mainly three opinions (i.e., agree, neutral, and disagree) of the respondents in percentages (%) regarding the five components (tidal river, sediment management, environment, human health, and community participation) of SITRM. More than 70% of the respondents agreed on tidal rivers, sediment management, environment, and community participation. Therefore, these four components were approved in the first round, and the component related to human health (60% agreed) was excluded from the second round of the opinion survey.

Table A5 provides expert opinions regarding 20 indicators of the SITRM in percentages. The respondents agreed from 51% to 69% on rising sea levels, water quality, biodiversity, migration, and health impact, whereas less than 51% agreed on forest and sanitation. Therefore, other indicators that captured more than 70% agreement in opinion were accepted in the first round. In addition, forest and sanitation were deleted from the list of indicators. Moreover, rising sea levels, water quality, biodiversity, migration, and health impact had to go to the second-round opinion survey. Table A6 presents the opinions of experts regarding the components and indicators for modification, addition, and deletion in the first round. The study modified the names of the indicators from water availability to tidal flow, new land formation to land reclamation, forest to vegetation with the settlement, biodiversity to terrestrial biodiversity involving livestock and trees, and migration of climate refugees to migration of day laborers. The study also added two sub-components (i.e., the physical environment and social environment (these sub-components were deleted in the second-round survey)) under the environment component. The SITRM index further added metrics for the erosion of riverbanks within the tidal river element and alternative sources of income within the institutional framework.

Moreover, this study made a modified list of threshold values of indicators and their explanation (Table A7) in the first round. The SITRM framework also provided a list of sub-indicators with threshold values that were added by the experts (Table A8) in this round. The expert assessments of one component and nine indicators for the SITRM framework, expressed as a percentage of the second round, are given in Table A9. Less than 70% of the respondents agreed with the water quality and drinking water indicators, and other indicators and components (human health) saw agreement by 70% or more in the second round. Therefore, the riverbank erosion, terrestrial biodiversity, vegetation with the settlement, sea level rises, migration, alternative livelihoods, and health impact indicators were accepted for the SITRM framework. In addition, this study presented the expert opinions for a list of modified/added components and indicators (Table A10), sub-components, and sub-indicators (Table A11) in the second round. All modified/added components, sub-elements, metrics, and sub-metrics were accepted, except the sub-components, physical environment, and social environment in the second round. Moreover, the study presented the threshold values of the indicators and sub-indicators of SITRM (Table A12), which were all accepted in this round.

Therefore, the study produced 5 components and 20 indicators in the final list of the SITRM framework (Table 1). In addition, this framework included 2 sub-components and 23 sub-metrics with their standard values of threshold. The study finalizes the standard values of the threshold (ranging from the highest to the lowest) of an indicator based on a field survey and opinion survey. It provides a short description of these indicators regarding their importance in developing the SITRM framework as follows:

Table 1.

The final list of indicators and elements of SITRM.

3.3. Tidal Flow

This study identifies tidal flow as an important indicator to develop SITRM. This indicator is divided into two sub-indicators including high tide and low tide. The Beel Bhaina TRM was successfully implemented for the first time in the Hari–Teka–Bhadra catchment in March and May of 2000 and 2001, recording flow velocities of 1.39 m/s at high tide and 1.04 m/s at low tide in Ranai [24]. In addition, the cross-sectional area for tidal flow was 547 m2 to 511 m2 during high tide and 315 m2 to 280 m2 during low tide, considering the water level and lunar effect. Then, the tidal flow was 760 m3/s to 710 m3/s in high tide and 328 m3/s to 291 m3/s in May 2001, when the tide was low in Ranai [24]. In addition, the index selects the maximum preferable threshold (MPT) values of 600 m3/s and 250 m3/s and the minimum not-preferable threshold (MNPT) values less than 550 m3/s and 200 m3/s for high tide and low tide, respectively.

3.4. Drainage Capacity

The drainage capacity of Hari–Teka River was at its maximum of 547 m2 by −10.4 m PWD depth and 79.5 m width at Ranai in May 2001 during Beel Bhaina TRM [24]. To maintain standard drainage capacity, it is important to drain out the excess water in the monsoon from the catchment. Drainage capacity is an essential indicator for SITRM, divided into the two sub-indicators of depth and width. Therefore, the index fixes MPT values of 12 m (−9 mPWD) and 75 m and MNPT values of less than 10 m (−7 mPWD) and 70 m, respectively, for depth and width at Ranai.

3.5. Riverbank Erosion

This study develops four important activities to protect people’s assets from riverbank erosion throughout the TRM operation conducted at the Hari–Teka River (Table A13). Based on the perfection or not perfection of these activities in the TRM project, the index requires 100% and 0%, respectively, for MPT and MNPT values for this indicator.

3.6. Sedimentation

The sedimentation on riverbeds of the tidal river is a very important indicator to develop SITRM. Therefore, the study requires the average annual sedimentation of the cross-sectional area in the percentage of a location for the assessment of TRM. The index fixes the maximum not-preferable value at more than 5 and the minimum preferable value at 0 for this indicator.

3.7. Waterlogging

The catchment area free from waterlogging is very important for agricultural production, biodiversity improvement, job facilities, and livelihoods of the coastal communities [6]. This study selects the area of land in percentage free from waterlogging of the catchment in different seasons from satellite data [15,25] as an indicator of SITRM. This indicator is divided into two sub-indicators (i.e., August during monsoons and December post-monsoon). The index identifies MPT values of 55 and 70 and MNPT values of less than 50 and 35, respectively, for monsoon and post-monsoon.

3.8. Land Reclamation

The evenly distributed sediment all over the TRM beel is important for land reclamation [3]. The general expectation of a farmer of TRM beel is to develop depressed land by sediment deposition during the TRM operation. Therefore, to overcome the challenges of rising sea levels and land subsidence, the study selects land reclamation by the minimum 0.5 m elevation for the total land (in 100%) of beels under the TRM project. The SITRM index selects 100% and 0% land of the beel, respectively, for MPT and MNPT values for this indicator.

3.9. Crop Production

TRM plays an important role in the production of crops within the catchment zone [12,15,25,26]. Therefore, the study identifies average crop production in ton/ha/yr as an essential indicator of SITRM. This indicator is divided into three sub-indicators, including paddy (Boro), vegetables, and shrimp+prawn. The index fixes the MPT values 3.5, 4.5, and 0.5 and the MNPT values 3, 3.5, and 0.4, respectively, for paddy (Boro), vegetables, and shrimp+prawn.

3.10. Vegetation with Settlement

The study selects land coverage (in percentage) of the total land of the catchment (from satellite image) for the indicator of vegetation with settlement in different seasons. The indicator is divided into two sub-indicators (i.e., monsoon and post-monsoon). The index identifies the MPT values of 15 and 30 and the MNPT values of 12 and 25, respectively, for monsoon and post-monsoon.

3.11. Rising Sea Levels

This study argues that developing the bottom land of the beel is very important for supporting coastal populations in coping with higher sea levels due to the changing climate [27]. The sea level rise reached 8 mm/year and land subsidence was 2 mm/year in this floodplain [2,3]. Therefore, it needs a 50-year TRM project in the catchment, including 10–12 beels (i.e., a 4- to 5-year TRM project for a beel) to overcome 10 mm/year. The MNPT value is less than 0.4 m of the TRM beel for this indication, and the index targets average land elevation for the MPT value of 0.5 m.

3.12. Employment

In order to evaluate the employment indicator, this study chooses the range of day laborers who engage in agriculture-related jobs on average over the course of a month. The index fixes the MPT value at 25 days, and the MNPT value is less than 20 days out of 30 days for this indicator.

3.13. Salinity

This section includes the study of salinity as an important indicator of SITRM for Boro production post-monsoon. Most of the salinity-tolerant varieties such as Binadhan-8, Binadhan-10, and BRRIdhan47 do not tolerate a salinity of >2 ppt or 4 dS/m of surface water and >8 dS of soil [28]. Therefore, this study found that for this indicator, the MNPT value was greater than 2 ppt and the MPT value was less than 1 part per thousand (ppt) in November and December.

3.14. Terrestrial Biodiversity

This section includes terrestrial biodiversity as a significant indicator of SITRM. It is divided into four sub-indicators including birds, four-legged animals, fruit trees, and timber trees. The index fixes the increased amount of biodiversity in a percentage at the with-TRM event (2007-13), compared to the without-TRM event (2002-6). Therefore, the MPT values are 10, 5, 10, and 15 for birds, four-legged animals, fruit trees, and timber trees, respectively, and the MNPT value is 0 for all sub-indicators.

3.15. Migration

This section involves the study of day laborers’ migration from the catchment to urban areas to assess migration indicators. It is divided into two sub-indicators (i.e., temporary migration and permanent migration). For temporary migration, the index identifies up to 30 cases as not preferable and 10 cases as preferred values, whereas for permanent migration, it detects up to 1 case as not preferable and 0 instances as preferable values.

3.16. Health Impact

This section includes the study of peoples’ diarrhea disease in the catchment to measure health impact. Out of 1000 people in the catchment, it fixes the maximum 100 cases as a not-preferable value and 0 cases as the preferable value for this indicator.

3.17. Awareness and Coordination

This indicator requires five important activities under two sub-indicators including awareness and coordination for the sustainability of the TRM project (Table A13). The SITRM index selects 100% and 0% for MPT and MNPT values, respectively, based on the perfection of the five activities regarding this indicator.

3.18. Compensation

For TRM to be sustainable, a poor-friendly flexible crop compensation process is required. Compensation is an important indicator that is divided into two sub-indicators (i.e., marginal farmers and other farmers from the tidal basin). There are 80% marginal farmers who have less than 100 decimal cropland and 20% other farmers who have more than 100 decimals croplands in the East Khukshia TRM beel. This study selects 100% and 0% of landowners for MPT and MNPT values, respectively, both from marginal and non-marginal farmers for the compensation indicator.

3.19. Land Use Changes (LUCs)

Rice is the staple food in Bangladesh. Paddy and vegetable production is very important for poor farmers. Most of the land in Beels is profitable for fishery production. This study identifies the MPT values regarding land coverage as 80% and 50% for paddy (Boro) and vegetables, respectively, and the MNPT values of 70% and 40% for paddy (Boro) and vegetables, respectively, for post-monsoon in the catchment.

3.20. Alternative Livelihoods

Many people live in surrounding villages of the TRM beels and have no agricultural land. They depend on the tidal basin for their livelihoods. They participate in everyday work in the beel, namely gathering snails, grass, and fish from the canal or khas land. Alternative livelihoods are needed for beel-dependent people during the TRM operation at the tidal basin. The index selects MPT and MNPT values, respectively, of 100% and 0% for beel-dependent people.

3.21. Rotation of TRM Beel

The tidal flow restoration is significant in the floodplain for sediment management. It protects the tidal river from sedimentation. To maintain and improve the TRM system, this process must be continuously continued from one wetland to another within a watershed. Basically, a long-term plan (for 50 years or 100 years) has been developed for the TRM operation in the catchment. The authorities should arrange several consultation meetings to disseminate this plan and develop a good understanding of local people to continue TRM in the catchment. This study identifies five activities for the rotation of TRM beel. The index picks 1 as the MPT value and 0 as the MNPT value for this indicator.

3.22. Water Governance

For the sustainability of the TRM project, the research highlights five key actions for the water governance indicator (Table A13) of SITRM. Based on the perfection or imperfection of these activities in the TRM project, the index requires 1 as the MPT value and 0 as the MNPT value for this indicator.

The study explored the SITRM framework (Table 2), including its sub-indicators and indicators using their default threshold settings and scores. It fixed scores of 1 to 4 for a sub-indicator based on its significance, whereas a score of 5 was used for an indicator. It selected a comparable weight (i.e., an equal score of 5 [8,10,13]) for each metric used to evaluate TRM sustainability. Therefore, the SITRM index value was a score of 100 from 20 indicators.

Table 2.

Description of the indicators regarding their importance in developing the SITRM framework Source: findings of this study.

In addition, the study used a performance scale [21] based on the scores of indicators (scores earned) from the SITRM framework to assess performance. Table A3 shows the six-step performance of an indicator or indicators. The scale includes scores of 0–1, 2.51–3, and 4.01–5 for very bad, satisfactory, and very good performance, respectively, for an indicator of sustainability. The scale also includes scores of 0–20, 51–60, and 81–100 for very bad, satisfactory, and very good performance for the indicator. This scale is designed to more accurately assess and classify the performance of indicators. Therefore, the index or an indicator needs very high action, low action, and no action for very bad, satisfactory, and very good performance, respectively. In addition, this framework can calculate earning the score of an indicator from its field value (based on its standard threshold value) by applying Equations (1) and (2). Moreover, the SITRM framework can quickly determine the index value by comparing the indicators’ observed values for gauging TRM sustainability. Then, it provides significant results (e.g., bad, satisfactory, or good water sustainability of the coastal area).

4. Discussion

SITRM pursues the WPI in the case of creating employment and reducing poverty, the WSI for improving drainage capacity and tidal flow and reducing waterlogging and pollution, and the CWSI and WJWSI for improving terrestrial biodiversity, land formation, and agriculture for coastal communities. Mutahara et al. [26] developed a socio-eco-technical (SET) model to characterize interactions between the social system, the ecological system, and the TRM in biophysical processes, socio-economic activities, and socio-institutional settings in the context of sustainable delta management. Talchabhadel et al. [29] and Islam et al. [2] illustrated the sediment management of a tidal river by sediment transport and deposition in its tidal basin for the sustainability of TRM. Gain et al. [5] demonstrated the socio-economic, biophysical, governance, and policy challenges for nature-based solutions such as TRM in the Ganges–Brahmaputra delta. Therefore, the present study suggests that the SITRM framework can improve ecosystem services and socio-ecological systems relationships of coastal communities by considering different components such as ecological, institutional, socio-economic management, Mediterranean rivers, sediment and human health, to ultimately achieve water sustainability. In this regard, other research is also in line with this research (e.g., Salam et al. [30] and P. de Alencar et al. [31]). The study conducted by Salam et al. [30] showed that the SITRM framework is a key tool for policymakers to measure TRM sustainability impacts. This framework helps in choosing more effective strategies to deal with the negative consequences of inundation, adverse climatic events, and environmental and social changes in coastal areas. In addition, P. de Alencar et al. [31] indicated that the SITRM framework is a comprehensive model used to assess sustainability in water resource management and tidal processes. This model can analyze the environmental, social, economic, and governmental effects well and helps policymakers and managers find appropriate solutions to deal with the problems caused by climate change and environmental damage in coastal areas. The results of another study conducted in the southwestern region of Bangladesh revealed that the SITRM framework serves as a tool to assess the sustainability of tidal water resource management in coastal areas [32].

According to Mutahara et al. [26], the uncertainties in the TRM project are due to power imbalances among stakeholders (BWDB, major shrimp company owners, and members of marginalized communities), inadequate time management, a knowledge gap, and complex financial issues. Sustainable water resource management in the lower GBM delta has not continued due to multiple conflicts and complexities in social interaction and stakeholder relationships [26]. The water professionals (mainly engineers and hydrologists) of BWDB were not competent to involve local stakeholders who played a key role in decision-making for delta management [6,30]. Mutahara et al. [26] recommended the collaboration between government agencies and community people for the development of a functional multi-stakeholder process (MSP). In addition, Mutahara et al. [26], Adnan et al. [4], and Gain et al. [5] argued for raising awareness, conflict resolution, cooperation, and the co-creation of knowledge among government agencies, NGOs, and civil society organizations (CSOs) for the sustainability of TRM. Nath et al. [32] illustrated the development of the conflict resolution systems of TRM implementation in the southwest delta, which is publicly accepted and trusted by the local elite. Therefore, SITRM includes the awareness and coordination indicator by focusing on conflict resolution issues. Moreover, Nath et al. [31] discussed sequential downstream–upstream planning, the appropriate design of peripheral embankment, proper mechanisms of compensation, and the effective duration of TRM for sustainable delta management. Huda et al. [33] analyzed water resource management in the southwest Bengal delta and assessed land use change, focusing on agriculture, bare land, waterlogging, river navigability, vegetation, human settlement, fish culture, and livelihoods. In addition, Islam et al. [2] argued for land reclamation by sediment deposition in the tidal basin to counteract sea level rises and land subsidence in the southwest Bengal delta. By properly addressing these coastal ecosystem issues, the present study comprises alternative livelihoods, LUC, land reclamation, rising sea levels, tidal flow, drainage capacity, water governance, and compensation indicators to form SITRM.

The CWSI has set the MPT and MNPT values at 45% and 18%, respectively. In Iran, these values are defined for the education index (USD −12.45) and the finance index (USD −2.23) [9]. For the awareness and compensation indicators in the SITRM framework, the values set for these values are 100% and 0%. Furthermore, the MPT and MNPT values for the water availability indicator of WSI in the Motru river basin were 6800 m3/per person-year and 1700 m3/per person-year, respectively [10]. In this regard, the values for the tidal flow indicator of SITRM in Hari–Teka River are 600 m3/s and 550 m3/s on the one hand and 250 m3/s and 200 m3/s on the other for high tide and low tide, respectively. In addition, the MPT and MNPT values for the vegetation coverage indicator of the WSI were 40% and 5%, respectively [10], since the values for vegetation with the settlement indicator post-monsoon of SITRM are 30% and 25%, respectively.

According to Talukder et al. [20], an integrated agricultural system (shrimp–rice–vegetables) was more sustainable than other integrated agricultural systems based on rice and large-scale shrimp agriculture systems. The current study makes the case that the coastal region’s water sustainability may be measured using the SITRM framework and that agricultural output is a key indication of sustainability. The SITRM framework also includes community participation (i.e., coordination and recognition, procedure of compensation, and varied livelihood options) and governance (i.e., the movement of TRM and governance of the water) as sub-elements under the institution component. It also measures tidal flow (the velocity of a tidal river at high and low tides), drainage capacity (width and depth of the river), land reclamation, and waterlogging indicators, aligning with the Institutional Analysis and Development (IAD) framework to evaluate the sustainability of the Tidal River Management (TRM). Adnan et al. [4] explored land elevation and reducing the susceptibility of flood in 44 polders of five coastal districts of southwest Bangladesh through the TRM approach. They identified 106 suitable beels where TRM could be implemented to decrease flood vulnerability by land reclamation. Therefore, there is significant potential for the application of SITRM in several tidal basins of the southwest coastal region of Bangladesh; tidal basins of the Subarnarekha River, Vamsadhara River, Sindhu River, and Netravati River in India; tidal basins for the Indus River, Chenab River, and Ravi River in Pakistan; and other coastal areas (the Amazon, Columbia, Saint Lawrence, Yangtze, and Mekong tidal river basins, etc.) of the world.

Due to time restrictions, not all 30 KIIs participated in the second stage of the study, and it only focused on the ecosystem of tidal rivers and floodplains within the polder system of the coastal area. Therefore, setting the indicators and fixing the standard threshold values of SITRM may vary based on coastal characteristics and water resource management approaches. This study introduces the SITRM framework to solve coastal problems and achieve water sustainability. Water professionals, researchers, and policymakers can use the SITRM sub-indicators and indicators using their default threshold settings to address coastal issues worldwide and improve SES relationships for community well-being and coastal sustainability.

5. Conclusions

Today, nature-based solutions, such as TRM, are important to achieve water sustainability by reducing human interventions in the natural environment and improving SES relationships in coastal regions. Therefore, this study has finalized the SITRM indicators in mitigating coastal problems, considering the socio-ecological relations, geophysical settings, and hydro-morphological characteristics of tidal river–floodplain ecosystems. The SITRM index raises a set of complex and interconnected issues that must be addressed comprehensively and in a coordinated manner for the sustainable management of coastal deltas. These issues include siltation and the management of sediment, waterlogging, the capacity of drainage of the rivers, rising sea levels, coordination, migration, and the governance of the water for sustainable delta management in coastal zones. Therefore, some indicators are different (e.g., sedimentation, waterlogging, land reclamation, and rising sea levels) and some are alternatives (e.g., awareness for education, tidal flow for water availability, and vegetation with settlement for vegetation) of SITRM, compared to recent indices (e.g., the WPI, CWSI, and WSI). In addition, this study fixes the MPT and MNPT values for the crop production (i.e., ton/ha/yr) indicator as 3.5 and 3 for paddy, 4.5 and 3.5 for vegetables, and 0.5 and 0.4 for shrimp+prawn, and for the waterlogging indicator (% catchment area free from waterlogging), these values were 55 and 50 during monsoons and 70 and 35 post-monsoon, respectively. Furthermore, the MPT and MNPT values for the drainage capacity indicator of SITRM in the Hari–Teka River are 12 m and 10 m, respectively, and 75 m and 70 m for the depth and width, respectively. These values are significant to mitigate coastal problems and improve SES relationships. Additionally, SITRM scoring is straightforward since each indication or the total score of 100 is determined by 20 significant indicators with equal weight (five points). The score ranged from 1 to 4 due to the relevance of a sub-indicator for SES. Moreover, policymakers and researchers can easily calculate the index value of SITRM and incorporate it into the performance scale. The decision is then made if action is required for an indicator and the index to enhance its performance. As a result, SITRM ensures sustainable water resource management by monitoring TRM sustainability and delivering urgent ecosystem services to support the lives of present and future generations of coastal people. The novelty of this study is to finalize the elements, sub-indicators, and indicators of SITRM by following recent indices based on ecosystem services and SES issues towards addressing coastal problems. In addition, it succeeds in innovative methods to collect expert opinions, and as a result, standard threshold values are determined for the sub-indicators and indicators.

5.1. Policy Recommendations

This study has some policy recommendations for the betterment of coastal communities by exploring sustainable TRM with its SITRM framework, and these are as follows:

- SITRM may be used by water experts not only to test the sustainability of TRM but also to test the sustainable coastal zone management.

- Policymakers can apply the SITRM indicators to non-polder as well as polder systems of coastal zones to achieve water sustainability.

- The study also suggests SITRM for achieving sustainable coastal livelihoods.

The novelty of the present study is in following a creative way to integrate biophysical, geo-morphological, and eco-technological knowledge towards the development of the SITRM framework with its standard baseline values of sub-indicators and indicators to advance coastal SES and community well-being. Therefore, SITRM is better than the WPI, WSI, CSWI, and WJWSI, as it addresses coastal problems and achieves water sustainability. As TRM helps enhance ecosystem services in improving coastal livelihoods, it needs future research evaluating the contribution of the SITRM in achieving SDGs, which stands for sustainable development goals.

The findings and the SITRM framework introduced in this study hold significant implications beyond the confines of the lower GBM delta of Bangladesh. Nature-based solutions like Tidal River Management (TRM) are increasingly vital to achieving water sustainability while minimizing human interventions in the natural environment. SITRM, designed with careful consideration of the socio-ecological relations, geophysical settings, and hydro-morphological characteristics of the ecosystem of tidal rivers and floodplains, addresses a spectrum of coastal challenges such as waterlogging, sedimentation management, river drainage capacity, rising sea levels, migration, coordination, and water governance. While SITRM’s indicators differ or provide alternatives compared to recent indices like the WPI, CWSI, and WSI, its adaptability and relevance extend to diverse coastal regions worldwide. Policymakers, water experts, and researchers can readily employ the SITRM framework not only to assess TRM sustainability but also to foster sustainable coastal zone management and livelihoods. As a versatile tool for advancing coastal socio-ecological systems and community well-being, SITRM offers a promising approach to achieving water sustainability in various national contexts, making it a valuable asset for future research and policy initiatives aimed at meeting SDGs for coastal communities worldwide.

5.2. Future Studies

It is suggested that future studies differentiate between the production of freshwater fish and saltwater fish caught or farmed in the delta. This differentiation can provide useful information on the ecological and economic influence of TRM on different types of fish production and can provide a better understanding of its benefits to coastal and deltaic communities.

Author Contributions

M.M.A.M., writing—review and editing, writing—original draft preparation, visualization, validation, software, resources, project administration, methodology, investigation, formal analysis, data curation, and conceptualization; H.A., writing—review and editing, writing—original draft preparation, visualization, validation, data curation, and conceptualization; R.V., Reviewing, editing and enriching the revised version; T.D., writing—review and editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. All authors have reviewed the final version, have confirmed their approval for publication, and take responsibility for the accuracy and integrity of the data.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Components and indicators of water sustainability.

Table A1.

Components and indicators of water sustainability.

| WJWSI | CWSI | WSI | WPI | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Component | Indicator | Component | Indicator | Component | Indicator | Component | Indicator | |

| Water Resources | Availability | Resource | Availability | Hydrology (Water quantity and water quality) | Pressure | Resource | Per capita annual water resources | |

| Demand | Demand | State | Coefficient of variation of rainfall | |||||

| Quality | Supply | Response | ||||||

| LUC | ||||||||

| Water Provisions | Coverage | Ecosystem Health | Stress | Environment (Environment Pressure Index—EPI) | Pressure | Access | % population to clean water | |

| Water loss | Quality | State | % population to sanitation | |||||

| Finance | Fish | Response | ||||||

| Human Health | Sanitation | Infrastructure | Demand | Life (Life Quality Index—LQI) | Pressure | Capacity | Literacy rate | |

| Access | Condition | State | GDP index | |||||

| Health impact | Treatment | Response | Ratio of the population engaged in non-agriculture to agriculture | |||||

| Capacity | Poverty | Human Health | Access | Policy (Education Index—EI) | Pressure | Use | The ratio of irrigated to cultivated area | |

| Education | Reliability | State | Domestic use | |||||

| Impact | Response | agricultural use | ||||||

| Capacity | Financial | Environment | Fertilizer used per hectare | |||||

| Education | ||||||||

| Training | % area of natural vegetation | |||||||

Note: Source: adapted from Masud et al. [3].

Table A2.

The opinions on the 5-point Likert scale.

Table A2.

The opinions on the 5-point Likert scale.

| Opinions | Point |

|---|---|

| Strongly disagree | 1 |

| Disagree | 2 |

| Neutral | 3 |

| Agree | 4 |

| Strongly agree | 5 |

Note: Source: Masud et al. [3].

Table A3.

Performance scale of the SITRM framework.

Table A3.

Performance scale of the SITRM framework.

| Score for an Indicator | Score for the Sustainability Index (or % Score of an Indicator) | Performance for Satisfaction | Needs Action |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0–1 | 0–20 | Very Bad | Need Very High Action |

| 1.01–2 | 21–40 | Bad | Need High Action |

| 2.01–2.5 | 41–50 | Not Satisfactory | Need Medium Action |

| 2.51–3 | 51–60 | Satisfactory | Need Low Action |

| 3.01–4 | 61–80 | Good | Need Very Low Action |

| 4.01–5 | 81–100 | Very Good | Need No Action |

Note: Source: authors’ compilation.

Table A4.

The potential components and indicators (with their threshold values) of SITRM.

Table A4.

The potential components and indicators (with their threshold values) of SITRM.

| Component | Indicator | Unit | Threshold Values | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maximum | Minimum | |||

| Tidal River | Water availability | m3/cap/yr | 1700 a | 500 b |

| Drainage capacity | - | 1 a | 0 b | |

| Environmental Challenges | Sedimentation | % | 100 b | 0 a |

| Rising sea level | mm/yr | 20 b | 0 a | |

| Waterlogging | % | 100 b | 0 a | |

| Resilience | Crop production (paddy + fish) | ton/ha/yr | (paddy) 3 a | <2 b |

| Forest | % | 25 a | <11.2 b | |

| New land formation | % | 100 a | 0 b | |

| Floodplain Ecosystem | Water quality | 76 a | <51 b | |

| Salinity | ppt | (crops) 1 b | 0 a | |

| Biodiversity | - | 1 a | 0 b | |

| Migration of climate refugees | % | 100 b | 0 a | |

| Human Health | Sanitation | % | 100 a | 0 b |

| Health impact | Cases/1000/pop | 100 b | 0 a | |

| Community Participation | Awareness and coordination | % | 100 a | 0 b |

| Compensation | % | 100 a | 0 b | |

| LUC | % | 100 b | 0 a | |

| Employment | % | 100 a | 0 b | |

| Rotation of TRM beel | - | 1 a | 0 b | |

| Water governance | - | 1 a | 0 b | |

Notes: ‘a’ for preferable, ‘b’ for not preferable, and - for national or global standard. Source: Masud et al. [3].

Table A5.

The expert opinion of respondents (in percentage) on indicators of SITRM in the first round.

Table A5.

The expert opinion of respondents (in percentage) on indicators of SITRM in the first round.

| Indicator | Disagree (1 and 2) | Neutral (3) | Agree (4 and 5) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Water availability | 0 | 0 | 100 |

| Drainage capacity | 0 | 7 | 93 |

| Sedimentation | 0 | 3 | 97 |

| New land formation | 7 | 20 | 73 |

| Waterlogging | 0 | 10 | 90 |

| Crop production | 0 | 23 | 77 |

| Forest | 10 | 40 | 50 |

| Sea level rise | 10 | 23 | 77 |

| Water quality | 0 | 37 | 63 |

| Salinity | 0 | 13 | 87 |

| Biodiversity | 0 | 33 | 67 |

| Migration | 7 | 30 | 63 |

| Sanitation | 0 | 50 | 50 |

| Health impact | 0 | 33 | 67 |

| Awareness | 0 | 17 | 83 |

| Compensation | 0 | 10 | 90 |

| LUC | 0 | 23 | 77 |

| Employment | 0 | 20 | 80 |

| Rotation of TRM beel | 0 | 17 | 83 |

| Water governance | 0 | 13 | 87 |

Note: Source: Silva et al. [23].

Table A6.

Expert opinions regarding components and indicators of SITRM for modification, addition, and deletion in the first round.

Table A6.

Expert opinions regarding components and indicators of SITRM for modification, addition, and deletion in the first round.

| Component | Sub-Component | Indicator | Modification | Addition |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tidal river | Water availability | Tidal flow | ||

| Riverbank erosion | ||||

| Sediment management | New land formation | Land reclamation | ||

| Environment | Physical environment | Forest | Vegetation with settlement | |

| Biodiversity | Terrestrial biodiversity (livestock and trees) | |||

| Social environment | Migration of climate refugee | Migration | ||

| Institution | Community participation | Alternative livelihoods | ||

| Water governance |

Note: Source: Silva et al. [23].

Table A7.

The modified threshold values and explanation of indicators in the first round.

Table A7.

The modified threshold values and explanation of indicators in the first round.

| Component | Indicator/Added Indicator | Explanation/Modified Explanation | Threshold | Modified Threshold | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Max | Min | Max | Min | |||

| Tidal River | Riverbank erosion | Protection of the people’s assets from riverbank erosion (%) | 100 a | 0 b | ||

| Sediment Management | Sedimentation | Average annual sedimentation rate on riverbed regarding cross-sectional area (%) | 100 b | 0 a | >5 b | 0 a |

| Land reclamation | Land development by even sediment distribution in the TRM beel (%) | 100 a | 0 b | - | - | |

| Environment | Sea level rise | Average land elevation targets 0.4 to 0.5 m of the TRM beel by considering annual sea level rises (8 mm/yr) for 50-year plan in the catchment for 10–12 beels (a 4-year TRM project) | 20 b | 0 a | 0.5 a | <0.4 b |

| Employment | Availability of agricultural-related jobs (days/month) in the catchment (%) | 100 a | 0 b | 25 a | <20 b | |

| Salinity | Salinity of Hari–Teka River during high tide (ppt) | 1 b | 0 a | >2 b | <1 a | |

| Human Health | Health impact | Diarrhea disease (cases/1000 pop) | 100 b | 0 a | 100 b | 0 a |

| Institution | Alternative livelihoods | To support landless (beel-dependent) and poor (if applicable including resettled) people with alternative livelihoods | 100 a | 0 b | ||

| Rotation of TRM in the beels of the catchment | Networking among beels with adjacent rivers for TRM operation in the catchment (%) | 1 a | 0 b | - | - | |

| Water governance | Trends and strategies of water governance (locally/nationally/regionally)—connecting a. main canals of the beels to the tidal rivers, b. one catchment to another catchment, c. upstream to downstream rivers, and d. identifying/learning the gaps/problems from past/present TRM project and (by policy improvements/changes) to solve them in the present/next TRM project | 1 a | 0 b | - | - | |

Notes: ‘-‘for no modification. Source: Silva et al. [23]. ‘a’ represents the preferred threshold value, while ‘b’ indicates the non-preferred threshold value. Source: Silva et al. [23] and adapted from Masud et al. [3].

Table A8.

The addition of sub-indicators with their threshold values in the first round.

Table A8.

The addition of sub-indicators with their threshold values in the first round.

| Component | Indicator | Explanation/Modified Explanation | Threshold | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Max | Min | |||||

| Tidal River | Tidal flow | Average annual flow of surface water (m3/s) at Ranai in 2002 | High tide | 600 a | <550 b | |

| Low tide | 250 a | <200 b | ||||

| Drainage capacity | Capacity of the Hari–Teka River at Ranai—downstream river—to drain out excess water from the catchment | Depth (m) | 12 a | <10 b | ||

| Width (m) | 75 a | <70 b | ||||

| Waterlogging | Area free from waterlogging (including permanent water body) in the catchment (%) | Monsoon (August) | 55 a | <50 b | ||

| Post-monsoon (December) | 70 a | <35 b | ||||

| Environment | Crop production | Average annual production (ton/ha/yr) | Paddy (Boro) | 3.5 a | <3 b | |

| Vegetables | 4.5 a | <3.5 b | ||||

| Shrimp+prawn | 0.5 a | <0.4 b | ||||

| Vegetation with settlement | Area is covered with vegetation including settlement (%) | Monsoon (August) | 15 a | <12 b | ||

| Post monsoon (December) | 30 a | <25 b | ||||

| Terrestrial biodiversity | Increase in number of species (%) | Livestock | Birds | 10 a | 0 b | |

| 4-legged animals | 5 a | 0 b | ||||

| Trees | Fruit | 10 a | 0 b | |||

| Timber | 15 a | 0 b | ||||

| Migration | No. of migrated (day laborer) people (%) | Temporary | >30 b | 10 a | ||

| Permanent | >1 b | 0 a | ||||

| Institution (Community Participation) | Awareness and coordination | Community people’s awareness and active role of beel committee and coordination (among CBOs, GOs, and NGOs) (%) | Awareness | 100 a | 0 b | |

| Coordination | 100 a | 0 b | ||||

| Compensation | No. of landowners who receive crop compensation from the government (%) | Marginal farmer (<100 decimal land) | 100 a | 0 b | ||

| Other farmers (>100 decimal land) | 100 a | 0 b | ||||

| Land use changes | Accessibility of crop production post-monsoon (%) | Paddy (Boro) | 80 a | <70 b | ||

| Vegetables | 50 a | <40 b | ||||

Notes: ‘a’ represents the preferred threshold value, while ‘b’ indicates the non-preferred threshold value. Source: Silva et al. [23] and adapted from Masud et al. [3].

Table A9.

Expert opinions (in percentage) on components and indicators in the second round.

Table A9.

Expert opinions (in percentage) on components and indicators in the second round.

| Component | Indicator | Disagree (1 and 2) | Neutral (3) | Agree (4 and 5) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Human health | 15 | 10 | 75 | |

| Riverbank erosion (during TRM) | 0 | 10 | 90 | |

| Terrestrial biodiversity | 0 | 25 | 75 | |

| Vegetation with settlement | 10 | 20 | 70 | |

| Sea level rises | 10 | 15 | 75 | |

| Water quality | 15 | 30 | 55 | |

| Migration | 10 | 20 | 70 | |

| Drinking water | 10 | 30 | 60 | |

| Alternative livelihoods | 0 | 20 | 80 | |

| Health impact (diarrhea disease) | 10 | 20 | 70 |

Note: Source: Silva et al. [23].

Table A10.

The opinion for modified/added components and indicators (from the first round) in the second round.

Table A10.

The opinion for modified/added components and indicators (from the first round) in the second round.

| Modified Component | Modified Indicator | Added Indicator | Opinion in % | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agree | Disagree | Neutral | |||

| Institution | 85 | 5 | 10 | ||

| Tidal flow | 100 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Vegetation with settlement | 90 | 5 | 5 | ||

| Terrestrial biodiversity | 85 | 10 | 5 | ||

| Land reclamation | 80 | 10 | 10 | ||

| Migration | 90 | 0 | 10 | ||

| Riverbank erosion | 80 | 10 | 10 | ||

| Alternative livelihoods | 90 | 0 | 10 | ||

Note: Source: Silva et al. [23].

Table A11.

Opinions for added sub-components and sub-indicators (from the first round) in the second round.

Table A11.

Opinions for added sub-components and sub-indicators (from the first round) in the second round.

| Component | Added Sub-Component | Indicator | Added Sub-Indicator | Opinion in % | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | D | N | ||||

| Environment | Physical environment | 40 | 50 | 10 | ||

| Social environment | ||||||

| Institution | Community participation | 85 | 5 | 10 | ||

| Water governance | ||||||

| Tidal flow | High tide | 100 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Low tide | ||||||

| Drainage capacity | Depth (m) | 100 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Width (m) | ||||||

| Waterlogging | Monsoon (August) | 100 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Post-monsoon (December) | ||||||

| Crop production | Paddy (Boro) | 100 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Vegetables | ||||||

| Shrimp+prawn | ||||||

| Vegetation with settlement | Monsoon (August) | 90 | 0 | 10 | ||

| Post-monsoon (December) | ||||||

| Terrestrial biodiversity | Livestock | 100 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Trees | ||||||

| Migration | Temporary | 100 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Permanent | ||||||

| Awareness and coordination | Awareness | 100 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Coordination | ||||||

| Compensation | Marginal farmer (<100 decimal land) | 100 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Other farmers (>100 decimal land) | ||||||

| Land use changes | Paddy (Boro) | 80 | 10 | 10 | ||

| Vegetables | ||||||

Notes: ‘A’ for Agree, ‘D’ for Disagree, and ‘N’ for Neutral. Source: Silva et al. [23].

Table A12.

Opinions for threshold values (from the first round) in the second round.

Table A12.

Opinions for threshold values (from the first round) in the second round.

| Component | Sub-Component | Indicator | Sub-Indicator | Threshold | Opinion in % | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Max | Min | A | D | N | |||||

| Tidal River | Tidal flow | High tide | 600 a | < 50 b | 100 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Low tide | 250 a | <200 b | 100 | 0 | 0 | ||||

| Drainage capacity | Depth (m) | 12 a | <10 b | 100 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Width (m) | 75 a | <70 b | 100 | 0 | 0 | ||||

| Riverbank erosion | 100 a | 0 b | 80 | 10 | 10 | ||||

| Sediment Management | Sedimentation | >5 b | 0 a | 90 | 0 | 10 | |||

| Waterlogging | Monsoon (August) | 55 a | <50 b | 85 | 5 | 10 | |||

| Post-monsoon (December) | 70 a | <35 b | 85 | 5 | 10 | ||||

| Land reclamation | 100 a | 0 b | 75 | 20 | 5 | ||||

| Environment | Crop production | Paddy (Boro) | 3.5 a | <3 b | 90 | 0 | 10 | ||

| Vegetables | 4.5 a | <3.5 b | 90 | 0 | 10 | ||||

| Shrimp+prawn | 0.5 a | <0.4 b | 90 | 0 | 10 | ||||

| Vegetation with settlement | Monsoon (August) | 15 a | <12 b | 90 | 0 | 10 | |||

| Post monsoon (December) | 30 a | <25 b | 90 | 0 | 10 | ||||

| Sea level rises | 0.5 a | <0.4 b | 75 | 0 | 25 | ||||

| Employment | 25 a | <20 b | 90 | 0 | 10 | ||||

| Salinity | >2 b | <1 a | 85 | 5 | 10 | ||||

| Terrestrial biodiversity | Livestock | Birds | 10 a | 0 b | 100 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 4-legged animals | 5 a | 0 b | 100 | 0 | 0 | ||||

| Trees | Fruit | 10 a | 0 b | 100 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Timber | 15 a | 0 b | 100 | 0 | 0 | ||||

| Migration | Temporary | >30 b | 10 a | 80 | 10 | 10 | |||

| Permanent | >1 b | 0 a | 80 | 10 | 10 | ||||

| Human Health | Health impact | 100 b | 0 a | 100 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Institution | Community participation | Awareness and coordination | Awareness | 100 a | 0 b | 100 | 0 | 0 | |

| Coordination | 100 a | 0 b | 100 | 0 | 0 | ||||

| Compensation | Marginal farmer (<100 decimal land) | 100 a | 0 b | 100 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Other farmers (>100 decimal land) | 100 a | 0 b | 100 | 0 | 0 | ||||

| Land use changes | Paddy (Boro) | 80 a | <70 b | 85 | 5 | 10 | |||

| Vegetables | 50 a | <40 b | 85 | 5 | 10 | ||||

| Alternative livelihoods | 100 a | 0 b | 100 | 0 | 0 | ||||

| Institution | Governance | Rotation of TRM in the beels of the catchment | 1 a | 0 b | 90 | 10 | 0 | ||

| Water governance | 1 a | 0 b | 80 | 10 | 10 | ||||

Notes: ‘a’ represents the preferred threshold value, while ‘b’ indicates the non-preferred threshold value. Source: Silva et al. [23] and adapted from Masud et al. [3].

Table A13.

Activities of the indicators.

Table A13.

Activities of the indicators.

| Indicators | Important Activities |

|---|---|

| Riverbank erosion | Raising awareness among people who live on the bank side by GOs |

| Raising awareness among people who live on the bank side by CBOs | |

| Installing concrete blocks on the riverbank to protect against erosion | |

| Resettling people, if necessary, by the government authority/NGOs | |

| Awareness and Coordination | Community people’s awareness regarding the TRM project |

| The active role of CBOs and local NGOs regarding the TRM project | |

| Coordination between GOs and CBOs for village protection dams | |

| Coordination between GOs and CBOs for the TRM project’s time fixation | |

| Coordination between GOs and CBOs for compensation | |

| Rotation of TRM beel | Dissemination of the long-term plan (50 years) for rotational TRM in different beels of the catchment by the authority (BWDB) |

| Community people were aware of the plan for rotational TRM | |

| Beel Committees have a good understanding of the next TRM project | |

| CBOs and NGOs have a good understanding of the next TRM project | |

| The authorities have taken the initiative to prepare the next TRM beel before closing the current Beel East Khukshia TRM | |

| Water governance | Removing obstacles from the main canals of beels in the catchment |

| Connecting the main canals of beels to the tidal rivers in the catchment | |

| Connecting upstream and downstream rivers in the catchment | |

| Connecting the catchments and developing the network system | |

| Learning from facing problems in past TRM project |

Note: Source: Silva et al. [23].

Table A14.

The list of key informants.

Table A14.

The list of key informants.

| Serial No. | Name of the Key Informant | Position and Organization |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Dr. Ainun Nishat | Professor Emeritus, BRAC University |

| 2 | Dr. Kazi Matin U Ahmed | Professor, GED, Dhaka University |

| 3 | Dr. Matin, WRE, BUET | Professor, WRE, BUET |

| 4 | Dr. Rezaur Rahman | Professor, IWFM, BUET |

| 5 | Dr. Shah Alam Khan | Professor, IWFM, BUET |

| 6 | Dr. Md. Mujibur Rahman | Professor, ESD, Khulna University |

| 7 | Motaher Hossain | Additional Chief Engineer, BWDB |

| 8 | Sheikh Nurul Ala | Ex. Chief Engineer, BWDB |

| 9 | Md. Zahurul Haq Khan | Director, IWM |

| 10 | Eng. Md. Humayon Karim | Associate Specialist, IWM |

| 11 | Md. Sarafat Hossain Khan | DG, WARPO |

| 12 | Md. Saiful Alam | Director Technical, WARPO |

| 13 | Malik FidalA Khan | Deputy ED, CEGIS |

| 14 | Dr. Maminul Haq Sarker | Deputy ED, CEGIS |

| 15 | Dr. Ashraful Alam | Associate Specialist, CEGIS |

| 16 | Farhana Ahmed | Specialist, CEGIS |

| 17 | Mukhteruzzaman | Senior Professional, CEGIS |

| 18 | Md. Mujibul Haque | Environmental Advisor, CEGIS |

| 19 | Md. Shahidul Islam | Director, Uttaran |

| 20 | Hashem Ali Fakir | Consultant, Uttaran |

| 21 | Mahir Uddin Biswas | Ex Member, Governing Council, BWDB |

| 22 | Md. Shafiqul Islam | Ex Principal, Chuknagar College, Khulna |

| 23 | Md. Motleb Sorder | Principal, Bhabadah College, Jashore |

| 24 | G. M. Amanullah | Assistant Professor, Dumuria Mahila College, Khulna |

| 25 | Faruque Alam | Vice Pricipal, Madhugram College, Khulna |

| 26 | Abu Mohsin Mollah | Program Coordinator, Progati Sangstha, Dumuria, Khulna |

| 27 | Md. Rezowan Mollah | Chairman, Dhamialia Union Parishad, Khulna |

| 28 | Shajahan Sheikh | President, Beel Committee, Beel Dohakhola, Khulna |

| 29 | Md. Anower Hosen Akunji | Journalist, The Daily Nayadiganta, Khulna |

| 30 | Md. Sirazul Islam Sarder | President, Beel Committee, Beel Panjia, Jashore |

References

- Gain, A.K.; Benson, D.; Rahman, R.; Datta, D.K.; Rouillard, J.J. Tidal river management in the southwest Ganges-Brahmaputra delta in Bangladesh: Moving towards a transdisciplinary approach? Environ. Sci. Policy 2017, 75, 111–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.F.; Middelkoop, H.; Schot, P.P.; Dekker, S.C.; Griffioen, J. Enhancing effectiveness of tidal river management in southwest Bangladesh polders by improving sedimentation and shortening inundation time. J. Hydrol. 2020, 590, 125228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masud, M.M.A.; Moni, N.N.; Azadi, H.; Van Passel, S. Sustainability impacts of tidal river management: Towards a conceptual framework. Ecol. Indic. 2018, 85, 451–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adnan, M.S.G.; Talchabhadel, R.; Nakagawa, H.; Hall, J.W. The potential of tidal river management for flood alleviation in South-western Bangladesh. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 731, 138747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gain, A.K.; Rahman, M.M.; Sadik, M.S.; Adnan, M.S.G. Overcoming challenges for implementing nature-based solutions in deltaic environments: Insights from the Ganges-Brahmaputra delta in Bangladesh. Environ. Res. Lett. 2022, 17, 064052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Y.; Zheng, T.; Wang, H.; Guan, R.; Zheng, X.; Walther, M. Experimental and numerical evidence on the influence of tidal activity on the effectiveness of subsurface dams. J. Hydrol. 2021, 603, 127149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]