Abstract

Reactive iron is a key driver of organic carbon preservation in marine sediments, but its participation in organic carbon remineralization complicates efforts to mechanistically constrain its role in preservation. To address this, we investigated the dual role of iron in the Mississippi River-influenced shelf sediment during low discharge (August 2016) and high discharge (May 2017). Duplicate sediment cores (30 cm depth) were collected from two stations; one core served as a natural reference, while the other was used for an incubation experiment. In the natural cores, reactive iron concentrations in the upper 9 cm were lower in August 2016 than in May 2017, whereas iron-bound organic carbon exhibited the opposite temporal pattern. Post incubation, approximately 10% of iron-bound organic carbon was lost at the offshore stations compared to a substantially greater loss (~59%) at the near-shore station. These results suggest that offshore regions may sustain more efficient organic carbon preservation via reactive iron, whereas the mechanism is considerably less effective in near-shore settings. Such spatial heterogeneity introduces significant uncertainty into current assessments of iron-mediated long-term organic carbon preservation on a global scale and underscores the need for more comprehensive investigations of iron–organic carbon interactions in continental shelve sediments.

1. Introduction

River-influenced continental shelves represent dynamic land–ocean interfaces where chemical, physical, geological, and biological processes interact strongly. The abundant supply of terrigenous materials—including organic matter (OM), trace metals, and nutrients—coupled with high primary productivity supports rapid carbon burial on river-dominated shelf sediments [1]. Because less than 5% of the terrestrial inputs are ultimately exported to the open oceans, river-influenced shelves are hotspot for biogeochemical cycling and long-term preservation of elements. Despite their importance, the mechanisms governing organic carbon (OC) preservation in the shelf sediments remain poorly understood [2].

Carbon biogeochemistry in the shelf sediment is controlled largely by the quantity and composition of OC delivered to the overlying water column from both terrestrial and marine sources. A fraction of this OC undergoes remineralization in the water column [3], while the reminder settles to the seabed. Once deposited, OC experiences further transformation through bioturbation, chemical reactions, and microbial activities, most of which are strongly influenced by sediment redox conditions. Oxygen penetration in the coastal sediments is typically restricted to a few millimeters [4]. Within this thin oxic layer, microorganisms either mineralize or assimilate available organic matter, leading to oxygen consumption. Re-oxidation of reduced metabolites also contributes to oxygen consumption [5,6]. Below the oxic zone, anaerobic conditions support microbial communities that utilize alternative electron acceptors. Organic matter degradation in these deeper sediment layer proceeds through denitrification, manganese reduction, iron reduction, sulfate reduction, and ultimately methanogenesis [7,8]. Carbon dioxide (CO2) generated by these processes accumulates in porewater, enriching the dissolved inorganic carbon (DIC) pool. The fraction of OC that escapes both aerobic and anaerobic remineralization becomes buried and contributes to long-term carbon sequestration.

Iron and manganese oxides play dual roles in sediment, functioning both as terminal electron acceptors for organic matter remineralization and as reactive surfaces that promote organic matter preservation. In shallow continental shelves, iron oxide originates from continental weathering, microbial activity, and atmospheric dust [9]. In the deep ocean, additional iron oxide inputs may arise from hydrothermal venting and volcanic sources [10]. The reactive iron (rFe) phases in sediment—defined here as the solid iron phases that are reductively dissolved by sodium dithionite—are typically present as nanospheres of goethite less than 10 nm in diameter [11,12,13]. These phases accumulate or form within the oxic sediment layer through the oxidation and precipitation of dissolved iron (II) produced during weathering and diagenetic recycling [14]. With time, rFe becomes increasingly crystalline, reducing its surface area, reactivity, and solubility [13]. Globally, approximately 21 ± 8.5% of total sedimentary OC is associated with rFe [13], and even in mature sediments (~1000–1500 yrs old), 23–27% of the total OC remains bound to reactive iron oxides. Such consistency suggests that the strong iron–OC associations may inhibit microbial degradation and enhance long-term OC preservation [13]. Organic carbon can associate with rFe through co-precipitation or direct chelation. However, simple correlation between reactive iron-bound organic carbon (Fe-OC) and total organic carbon (TOC) alone does not fully explain the mechanisms by which rFe governs OC preservation in marine sediments—underscoring the classic reminder that correlation is not always causation [15]. Although substantial progress has been made in understanding molecular-scale interactions between organic matter and mineral phases such as rFe, the stability of Fe-OC complexes over centennial-to-millennial timescales remains uncertain. The present study addresses this knowledge gap using short-term incubation experiments designed to assess how rFe influences long-term OC sequestration in the shallow continental shelf sediments.

In large river-influenced shelves like the Mississippi River-influenced shelf (MIS), sediment stocks of particulate Fe and Mn oxides are shaped by terrestrial inputs and their recycling efficiency within the sediments. These factors, in turn, are modulated by river discharge, depositional conditions in the adjacent shelves, bottom-water oxygen, and other environmental variables [16]. Recent work in the MIS reported that 32–33% of total OC is associated with rFe—approximately 10% higher than global estimates [17]. Although, a larger Fe-OC fraction does not necessarily translate greater preservation without understanding of the underlying mechanisms, the elevated values underscore the MIS as a key system for studying rFe-OC interactions. Additionally, the region experiences one of the world’s largest seasonal hypoxic zones each summer [18], which may further influence iron cycling and OC dynamics.

To develop a mechanistic understanding of organic carbon–rFe coupling in the MIS sediment, we conducted short-term (<2 days) sediment-core incubations under varying oxygen conditions and quantified the resulting changes in Fe-OC. We hypothesized that if rFe plays a significant role in long-term OC preservation, only minimal loss of Fe-OC would occur over these experimental timescales.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

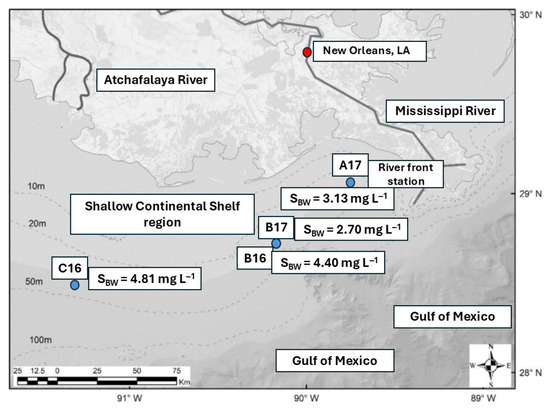

The Mississippi River (MR) drains 41% of the continental United States and ultimately discharges into the northern Gulf of Mexico through the Southwest Pass. The Mississippi-influenced shelf (MIS) is a shallow continental shelf that receives substantial inputs of nutrients and minerals from terrestrial sources [1]. The sampling locations for the present study are located within the MIS (Figure 1). During spring, the region experiences significant freshwater discharge [19], which strongly influences the spatial extent of the freshwater plume [20]. Previous studies have documented major sediment deposition within 30 km of the river mouth [21]. Elevated freshwater discharge during spring enhances net primary productivity on the shelf, driven primarily by increased nutrient inputs [19]. MIS sediment is predominantly autochthonous, exhibiting carbon isotopic signatures similar to those of marine phytoplankton [22,23]. Bianchi et al. (2002) [21] reported that the organic carbon burial rate over the entire Louisiana coastal shelf ranges from 0.5 to 1 Tg yr−1-representing less than 2% of the total OC inputs from terrestrial and marine sources. Xu et al. (2022) [24] described the sediment as silty clay, consisting of 9.9% sand, 60.7% silt, and 29.4% clay. Dutta et al. (2025) [19] found that the near-shore portion of the shelf functions as a source of CO2, whereas the offshore area alternates between a source and sinks. Their work demonstrated that CO2 cycling in the shallow region of the shelf is strongly influenced by freshwater hydrology and community metabolism as well as wave–current interactions. The hydrological and nutrient controls on MIS biogeochemistry are well documented [25,26]. It has been reported [27] that seven major elements (Ca, Na, Mg, Si, K, Al, and Fe) comprise 99% of the total annual metal load (7.38 × 107 tons) delivered by the Mississippi–Atchafalaya River System (MARS) and that the Mississippi River is particularly enriched in Al, Ba, B, Ca, Fe, Mg, Mn, Ag, and Ti. Their study also showed that the Mississippi River contributes 64–76% of the total annual metal load from MARS to the northern Gulf of Mexico. A previous study from the region indicates that 32–33% of the total OC in MIS sediment is associated with rFe, although the specific role of rFe in OC preservation on the shelf was not directly assessed [17], with some studies showing potential for release of reduced Fe from the sediment under near anoxic conditions [28].

Figure 1.

Map showing the sampling locations on the Mississippi-influenced shelf in August 2016 and May 2017. Stations ‘A’, ‘B’, and ‘C’ indicate near-shore, intermediate, and offshore sites, respectively. The numbers following the station IDs indicate the sampling year. ‘SBW’ denotes bottom-water salinity.

2.2. Sampling Details

Sediment cores and bottom water were collected between the 10–60 m isobaths of the Mississippi River-influenced shelf region during research cruises conducted in August 2016 and May 2017 aboard the R/V Pelican. These sampling periods correspond to relatively high- and low-river-discharge periods, respectively (Figure 1). Although the plan targeted near-shore (A), offshore (C), and their intermediate station (B) during both cruises, logistical constraints prevented sampling at station ‘A’ in August 2016 and station ‘C’ in May 2017. A summary of the sampling and analytical procedures is provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of sample collection and analytical procedure conducted during the August 2016 and May 2017 cruises on the Mississippi-influenced shallow shelf regions.

2.3. Collection and Shipboard Treatment of Sediment Cores

Duplicate sediment cores (30 cm in length and 10 cm diameter) were collected at each station using a low-wake Ocean Engineering multicore system. Upon recovery, the cores were immediately sealed at the bottom using custom-designed end caps. Bottom-water samples (20 L) for core incubation experiments were also collected at each station using Niskin bottles (General Oceanic, USA). A CTD profiler was deployed concurrently to record water temperature, salinity, and dissolved oxygen (DO).

2.3.1. Shipboard Processing of the Sediment Cores

One of the collected cores from each pair was left untreated and is hereafter referred to as the ‘natural core’. The natural cores were sliced from 0.5 cm to 8.5 cm in depth with intervals of 2 cm. Each sediment slice was then placed in a Mylar zip lock bag (Fisher Scientific, USA) and stored at −20 °C until analyses.

The second sediment core was incubated on board to measure the DIC and oxygen fluxes. Within two hours of collection, each core was gently filled with bottom water along the core tube’s side wall to cause minimal disturbance to the sediment–water interface. The cores were then sealed using custom-designed PVC piston lids (made by LSU shop), which allowed the water column height to be adjusted to 25 cm [29,30]. Care was taken to ensure that no headspace or air bubbles were present. The lids were equipped with double O-rings (https://www.mcmaster.com/products/o-rings/, accessed on 1 December 2025) for air-tight incubations, a stirring device, and inlet/outlet ports for sampling. All cores were connected to a reservoir containing filtered bottom water, enabling gravity-driven replenishment during sampling. The sealed cores were then immersed in an opaque water bath incubator, which was maintained at in situ bottom-water temperature (Table 2). The total delay between core retrieval and the start of sampling was restricted to ≤3 h. Water samples of DIC and DO were collected from the overlying water of the core at regular intervals until the DO concentrations dropped below 1 mg L−1 or until 48 h had elapsed, whichever occurred first. DIC samples were filtered through a Whatman GF/F syringe filter (Fisher Scientific, USA) and transferred to acid-washed, muffled, gas-tight glass exetainers after overflowing the vial with at least one vial-volume of sample. Samples were then preserved with saturated HgCl2 to arrest microbial activity and stored at 5 °C until analysis. DO was measured concurrently using a Presens Microx 4 oxygen meter (https://www.presens.de/products/o2, accessed on 1 December 2025). Water samples were also collected from the connected water reservoir at each time to perform volumetric dilution corrections during flux calculations. Following completion of the incubation, the top 9 cm of the core was sectioned and stored using the same procedure described for the natural core.

Table 2.

Spatial variabilities in water depth, temperature (T), and dissolved oxygen (DO) conc. in the bottom water, and salinities of surface (SW) and bottom (BW) waters in August 2016 and May 2017 cruises. The date of collection is mentioned as “mm/dd/year”.

2.3.2. Laboratory Processing of Sediment Samples and Analytical Techniques

Upon returning to the laboratory, sediment samples collected from both the natural and incubated cores were properly homogenized. The homogenized samples were then freeze-dried, milled, and sieved through a 120 μm mesh [31]. A portion of the dried samples was exposed to HCl vapor to remove the inorganic carbon content prior to measuring the total organic carbon (TOC) content in the sediment before rFe extraction [32]. The remaining samples were used for rFe extraction following a buffered citrate dithionite bicarbonate (CDB) single-step extraction method [33,34]. All glassware, plasticware, and syringes used during extraction were pre-cleaned in accordance with GEOTRACES sampling protocols [35]. After extraction, sediments were rinsed three times with Milli-Q water to ensure complete removal of CDB reagent. The washed samples were then oven-dried at 50 °C and subsequently treated with HCl vapor to determine the TOC content in the sediment after rFe extraction. Detailed procedures for sample treatment and rFe extraction are provided in Ghaisas et al. (2021) [17].

Following this, a 1 mL aliquot of the extracted rFe sample was diluted with a 2% trace-metal-grade nitric acid (OptimaTM grade HNO3; Fisher Scientific, USA) solution prepared using Milli-Q ultra-pure water (Millipore Milli-Q system, USA). The acid-diluted rFe samples were analyzed at the Wetland Biogeochemistry Analytical Services, Louisiana State University, using high-resolution inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectroscopy (ICP-OES) on a Varian MPX spectrophotometer (USA). The detection limit for Fe was 0.90 µg L−1 for Fe. TOC in sediments before and after rFe extraction was quantified using a Costech 1040 CHNOS Elemental Combustion system (USA) following the EPA Standard Method 440.0. DIC samples collected during the sediment-core incubation experiment were analyzed using an Apollo SciTech DIC Analyzer (AS-C5) (USA). Briefly, a 0.5–1 mL sample was acidified to convert all dissolved carbonates to CO2 gas, which was then quantified using a solid-state infrared CO2 detector (LI-850, Li-COR, USA) [36]. Further details on the DIC analytical procedure are provided in Cai et al. (1998) [36].

2.4. Calculation

The Fe-bound OC (Fe-OC) content in the samples from each depth was calculated as follows:

Fe-OC = [TOC]Before rFe extraction − [TOC]After rFe extraction

For shelf sediment, the change in Fe-OC during the incubation period was determined as the difference between the average Fe-OC values of the natural and incubated cores down to 9 cm depth. A smaller decrease in Fe-OC during incubation indicates a greater potential for rFe-mediated OC preservation and vice versa.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

Seasonal differences were evaluated using one-way ANOVA (p < 0.05) using JMP 14 (SAS).

3. Results

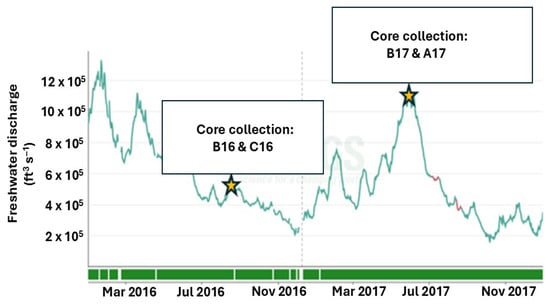

3.1. Hydrology and General Features of the Shelf Water

In August 2016, surface-water salinity ranged from 27.23 to 33.01, while bottom-water salinity ranged from 35.90 to 36.08 (Table 2). In comparison, May 2017 exhibited relatively higher salinity, with values of 27.49–28.62 for surface waters and 36.20–36.24 for bottom waters. Salinity is largely controlled by freshwater discharge. The average freshwater discharge in May 2017 was 684 ± 115 × 103 ft3 s−1 (USGS site 07374525, Belle Chasse, LA, USA), approximately 1.5 times higher than that recorded in August 2016 (Figure 2). The relatively elevated salinity observed in May 2017 despite this higher discharge likely reflects the timing of sampling; the cruise occurred roughly two weeks before the peak discharge conditions. The surface waters were warmer in August 2016 (24.43 to 25.83 °C) compared to May 2017 (22.56–22.64 °C) (Table 2). Bottom waters during both cruises were not well oxygenated and ranged from hypoxic to moderately oxygenated. Dissolved oxygen conc. in August 2016 ranged between 4.40 and 4.81 mg L−1, whereas lower values of 2.70 to 3.13 mg L−1 were recorded in May 2017 (Table 2). The oxygenated conditions in the MIS are conducive to aerobic remineralization of organic matter in the overlying water column.

Figure 2.

Variation in freshwater discharge of the Mississippi River at Belle Chasse, LA, from January 2016 to December 2017. Discharge data were obtained from the USGS (site 07374525). Sampling events noted with a star symbol.

3.2. Reactive Iron (rFe) Distribution in the Natural Cores

The vertical distribution of rFe within the 0 to 9 cm depth range of MIS sediment did not display a consistent trend during either sampling campaign. However, pronounced differences in sedimentary rFe content were observed between the two cruises.

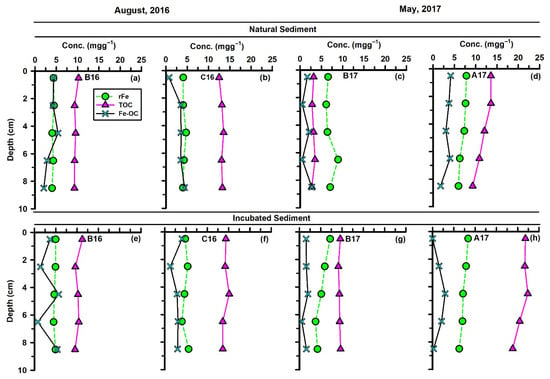

During August 2016, when freshwater discharge was relatively low (Figure 2), and the sediment rFe contents in the upper 8.5 cm depth at the intermediate station ‘B16’ ranged from 3.99 to 4.44 mg g−1 (average = 4.21 ± 0.20 mg g−1; Figure 3a). A modest increase was observed offshore at station ‘C16’, where rFe ranged from 4.00 to 4.75 mg g−1 (average = 4.23 ± 0.31 mg g−1; Figure 3b).

Figure 3.

Vertical distributions of rFe, TOC, and Fe-OC in the upper 9 cm depth of natural (a–d) and incubated (e–h) sediment cores collected from the MIS.

Compared to August 2016, sedimentary rFe levels were higher in May 2017, coinciding with elevated freshwater discharge (Figure 2). During this period, rFe increased slightly from the near-shore station A17 (5.96–7.82 mg g−1; average = 7.00 ± 0.83 mg g−1) to the intermediate station ‘B17’ (6.14–8.93 mg g−1; average = 7.03 ± 1.12 mg g−1) (Figure 3c,d).

Overall, rFe concentrations in the MIS sediments fall within the ranges reported for other regions globally (Table 3). A one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) confirmed significant seasonal variabilities in sedimentary rFe across the study region (p ˂ 0.05).

Table 3.

Global distributions of reactive iron (rFe), total organic carbon (TOC), and Fe-OC (rFe-bound OC) in the sediments of the marine and coastal regions. Values are reported in ‘mg g−1’ units unless otherwise noted.

3.3. Distribution of Fe-OC in Natural and Incubated Cores

In the continental shelf region, OC-rFe coupling in sediments is governed not only by the size of the rFe pool but also by the quantity and composition of TOC inputs. In August 2016, TOC concentrations in the upper 9 cm of sediment at the intermediate station B16 ranged from 9.25 to 10.22 mg g−1 (average = 9.52 ± 0.41 mg g−1; Figure 3a). TOC increased from the intermediate station towards the offshore station ‘C16’, mirroring the spatial pattern observed for rFe. At station ‘C16’, TOC values ranged from 12.50 to 13.55 mg g−1 (average = 13.11 ± 0.39 mg g−1; Figure 3b). Compared to August 2016, sedimentary TOC levels were lower in May 2017. During this period, TOC decreased sharply from the near-shore station ‘A17’ (9.29–13.59 mg g−1; average = 11.87 ± 1.84 mg g−1) to intermediate station ‘B17’ (2.76–3.51 mg g−1; average = 3.09 ± 0.30 mg g−1) (Figure 3c,d). The elevated TOC at station ‘A17’ likely reflects substantial delivery of terrestrially derived organic matter to the near-shore region during peak Mississippi River discharge. Overall, sedimentary TOC concentrations in the MIS region fell on the lower end of the range reported for the other regions where rFe-TOC coupling has been evaluated (Table 3). Despite significant terrestrial OC inputs from the Mississippi River and the dominance of silty-clay sediments, the relatively low TOC content in the MIS sediment suggested either (1) enhanced anaerobic remineralization within the shelf environment or (2) substantial lateral export of river-derived organic matter to the adjacent continental slope region.

3.3.1. Fe-OC in the Natural Cores

In August 2016, Fe-OC concentrations in the natural core collected from the intermediate station ‘B16’ ranged from 2.05 to 5.40 mg g−1, with an average of 3.77 ± 1.33 mg g−1 (Figure 3a). At the offshore station ‘C16’, the average Fe-OC decreased by 17%, with values ranging from 0.73 to 4.37 mg g−1 (Figure 3b). The spatial pattern contrasts with that observed by rFe and TOC.

Compared to August 2016, sedimentary Fe-OC concentrations decreased in May 2017 during elevated freshwater discharge conditions (Figure 2). During this period, Fe-OC decreased by roughly 2-fold from the near-shore station ‘A17’ (0.75–4.13 mg g−1; average = 3.31 ± 0.97 mg g−1) to the intermediate station ‘B17’ (0.51–2.76 mg g−1; average = 1.52 ± 1.00 mg g−1) (Figure 3c,d). Ghaisas et al. (2021) [17] reported that Fe-OC accounted for 31.9–33.2% of the TOC within the upper 20 cm of natural cores—comparable to our calculated value of ~32% for the upper 9 cm of same core. This suggests that, despite spatial variability in sedimentary TOC and rFe across the MIS, the proportional contribution of Fe-OC to the TOC pool remains relatively stable.

Overall, the proportion of Fe-OC within the TOC pool in the MIS sediments is substantially higher than values reported for many other marine and coastal regions globally (Table 3). Despite comparatively low TOC concentrations, the elevated Fe-OC fraction indicates strong associations between rFe and organic matter in this river-influenced shelf sediment, underscoring the significant role of rFe in promoting OC preservation in the MIS sediments.

3.3.2. Fe-OC in the Incubated Cores

In August 2016, Fe-OC concentrations in the incubated core collected from the intermediate station ‘B16’ ranged from 0.77 to 5.68 mg g−1, with an average of 3.37 ± 2.23 mg g−1 (Figure 3e). At the offshore station ‘C16’, the average Fe-OC was ~15% lower, with values ranging from 1.32 to 4.05 mg g−1 (Figure 3f).

In May 2017, Fe-OC concentrations in the incubated cores increased slightly from the near-shore station ‘A17’ (0.02–2.96 mg g−1; average = 1.37 ± 1.25 mg g−1) to the intermediate station B17 (0.58–2.00 mg g−1; average = 1.49 ± 0.54 mg g−1) (Figure 3g,h).

A consistent pattern across both cruises was that there was a lower Fe-OC content in the incubated cores relative to their corresponding natural cores. This reduction indicates active remineralization of Fe-OC in the shallow sediment layers of the MIS, which would partially diminish rFe-mediated OC preservation. Nevertheless, the relatively high proportion of Fe-OC within the sedimentary TOC pool—compared to global estimates—highlights the significance of this river-dominated shelf system for understanding the role of rFe in long-term OC preservation in sediment.

4. Discussions

In general, spatial and temporal variability in sedimentary rFe and Fe-OC is shaped by coupled interactions of hydrological, biogeochemical, and geochemical processes operating across the river-influenced shelf system. The primary drivers governing the distribution and interactions of rFe and Fe-OC in the Mississippi shelf sediments are discussed below.

4.1. Drivers for rFe in the MIS Shelf Sediment

Ghaisas et al. (2021) [17] reported that freshwater discharge exerts strong control over rFe concentrations in MIS sediment, with discharge typically peaking between March and May (Figure 2). The elevated freshwater input in May 2017 likely delivered substantial quantities of fresh sediment to the shelf, thereby enriching the sedimentary rFe pool [2]. Increased mixing during periods of elevated discharge may further promote flocculation and settling of colloidal iron complexes, enhancing rFe accumulation in sediment [53]. In addition to hydrodynamic controls, biogeochemical processes—particularly primary productivity—may also mediate the sedimentary rFe content depending upon factors such as euphotic layer depth, community composition, nutrient availability, etc., [7,19]. Recent work by Dutta et al. (2025) [19] showed that primary productivity increases in near-shore regions of the northern Gulf of Mexico during high-discharge periods, driven by enhanced nutrient inputs. Because iron is critical micronutrient for marine primary production [54,55], elevated productivity at the near-shore station ‘A17’ during the high-discharge periods may have reduced the pool of unutilized iron in the water column, thereby reducing the downward flux of iron to the sediment.

The depth profile of rFe from August 2016 exhibited no discernible trend within the upper 9 cm of MIS sediment (Figure 3a,b). This pattern likely reflects physical sediment redistribution driven by bottom currents and storm-induced wave actions [56]. Supporting this interpretation, an earlier 210Pb study demonstrated both a high sedimentation rate (0.03–0.45 cm yr−1) and active sediment remobilization in the MIS [57]. Additional evidence from 234Th showed excess activity within the upper 3–5 cm, suggesting that the surface sediments were deposited within the past six months or less—i.e., are relatively recent [17]. The MIS is also highly susceptible to annual hurricane activity, which can redistribute sediments to depths of ~20 cm [58]. In contrast to the August 2016 observation, the May 2017 profile at station A17 exhibited elevated rFe in the surface sediments followed by decreasing concentrations in the subsurface layers. Corbett et al. (2004) [56] reported the deposition of a mobile mud layer up to 12 cm thick near the river mouth (station A17) during a high-discharge period (May 2017). This newly deposited, mobile material may serve as the source of elevated surface-layer rFe at station ‘A17’ in May 2017.

4.2. Drivers of Iron-Bound Organic Carbon (Fe-OC) in the MIS Shelf Sediment

The spatial and temporal variability in Fe-OC in MIS sediment likely reflects differences in organic matter sources and relative inputs of TOC and rFe to the system. Bulk δ13C values indicate that TOC in the Wax Lake delta is primarily terrestrial in origin [52], whereas TOC in the MIS is predominantly marine [22]. The 34% decline in sedimentary TOC in May 2017 may largely contribute to the lower Fe-OC content observed in the natural core compared to August 2016. Reduced TOC availability in May 2017 may have limited the amount of organic matter available to encapsulate bioavailable rFe [17].

In contrast, the incubated sediment cores exhibited a decrease in Fe-OC in May 2017 despite a 25% increase in TOC relative to August 2016, demonstrating that greater TOC inputs do not necessarily enhance Fe-bound OC preservation. Seasonal processes, particularly algal bloom, may also shape the Fe-OC content in shelf sediment. In this region, spring algal blooms promote the scavenging of marine plankton biomass by rFe, enhancing the downward flux of autochthonous organic matter. Rapid aggregation and settling of planktonic material by rFe may account for the elevated Fe-OC observed in August 2016 (spring) [17].

The vertical distribution of Fe-OC showed no noticeable trend within upper 9 cm in MIS sediment during either sampling period (Figure 3). This pattern likely reflects physical sediment redistribution and the alternating supply and dilution of both rFe and organic matter, processes that collectively disrupt and reset seasonal diagenetic processes in the MIS [17]. Frequent mixing on the shelf sediment enhances remineralization of organic matter, reducing TOC content. Additionally, such mixing inhibits dissimilatory iron reduction, thereby limiting the enrichment of dissolved Fe in near bottom waters [59].

4.3. Fe-Organic Carbon Coupling in the MIS Sediment—Primary Evidence

A first-order understanding of the coupling between rFe and organic carbon in the shelf sediment can be inferred from their weight ratios. The OC: rFe weight ratio increased by roughly 31% from the natural sediment core (average = 1.88 ± 1.00) to the incubated core (average = 2.46 ± 0.57). Notably, the OC: rFe ratios for both the natural and incubated cores collected from the MIS were substantially higher than maximum sorption capacity of rFe for OC (0.22 g OC per gm Fe; ref. [60]). This discrepancy likely reflects formation of OC-Fe complexes that enhance the capacity of Fe-bearing surfaces beyond their sorption limits. Such complexation could protect OC from further microbial decomposition, thereby enhancing its preservation in the shelf sediment [60].

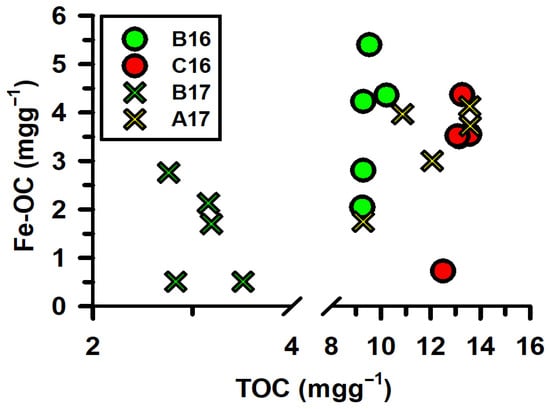

The spatial trends further highlight the complexity of rFe-OC interactions. In August 2016, Fe-OC at the offshore station ‘C16’ was lower than the intermediate station ‘B16’, despite increases in both rFe and TOC. Moreover, in May 2017, Fe-OC was higher at the near-shore station ‘A17’ compared to the intermediate station ‘B17’, even though rFe decreased and TOC increased. This pattern indicates that increasing TOC loading in the shelf sediment does not necessarily enhance the association of OC with rFe in this river-influenced shelf sediment—contrary to expectations based solely on OC: rFe ratios. To further investigate the relationship, the Fe-OC content in the sediment was plotted against changes in TOC in the MIS sediment (Figure 4). The absence of significant correlation between the two variables suggests that mechanisms beyond simple pool size—such as differences in organic-matter composition, differences in rFe mineralogy and reactivity, or particle aggregation and transport dynamics—play key roles in regulating rFe-TOC coupling in the continental shelf sediment. Further experimental work is required to clarify these underlying processes.

Figure 4.

The graph illustrates the variability in TOC and Fe-OC in MIS sediment. Circles represent data collected during the August 2016 cruise, while crosses represent data collected in the May 2017 cruise. Data points from intermediate, offshore, and near-shore stations are shown in green, red, and yellow, respectively.

4.4. Implications of Fe-OC on Organic Carbon Preservation in the MIS Sediment: Experimental Evidence

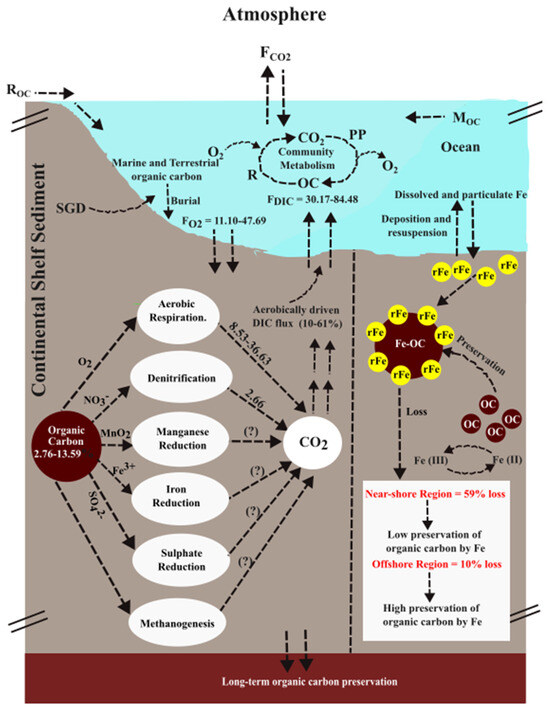

A simplified schematic diagram illustrating organic carbon (OC) dynamics on the continental shelf is shown in Figure 5. In this conceptual model, OC enters in shelf waters through riverine input (ROC), marine sources (MOC), submarine groundwater discharge (SGD), and primary productivity (PP). OC is removed through community respiration (R) and burial to seabed sediments. The Mississippi River delivers significant amounts of particulate organic carbon (POC) and dissolved organic carbon (DOC) to the Louisiana coast region, largely derived from C3 vascular plants and coastal wetlands [21]. However, multiple studies indicate that SGD accounts for less than 1% of Mississippi River discharge on the Louisiana shelf [61,62,63] and thereby likely plays a negligible role in shelf the OC budget. Biological controls on OC cycling (i.e., community metabolism) vary seasonally and are strongly influenced by nutrient availability and community composition. Based on primary production estimates, previous studies suggest that only 20–50% of the organic carbon produced in coastal waters off the Mississippi River is ultimately buried in the Louisiana Shelf sediments, and less than 40% of the buried OC is of terrestrial origin [64]. The unaccounted-for OC is either remineralized on the shelf region or transported offshore via the benthic boundary layer and subsequently buried in slope and Mississippi Canyon sediments [65].

Figure 5.

A figure presenting organic carbon metabolism in the shelf sediment. Here, ROC, MOC, OC, PP, R, SGD, and F indicate riverine organic carbon, marine organic carbon, organic carbon, primary production, respiration, submarine groundwater discharge, and flux, respectively. Values are in ‘mmol m−2 d−1’ unless otherwise noted.

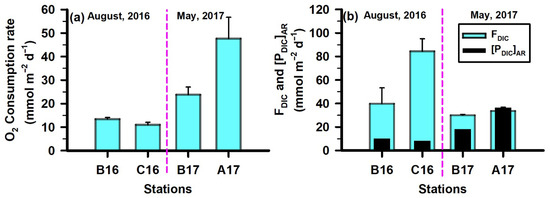

To assess remineralization in shelf sediments, a useful first step is to examine sediment O2 consumption (O2Cons.). Aerobic remineralization of organic matter can be approximated using O2 consumption rates; however, it is important to note that oxygen is also consumed during the reoxidation of reduced metabolites within the sediment. O2Cons. exhibited clear temporal variability between August 2016 and May 2017. During the low-freshwater-discharge conditions in August 2016, O2Cons. decreased by roughly 10% from the intermediate station ‘B16’ (13.50 ± 0.64 mmol m−2 d−1) to the offshore station ‘C16’ (11.10 ± 0.98 mmol m−2 d−1) (Figure 6). Compared to August 2016, consumption rates increased substantially in May 2017 under high-freshwater-discharge conditions. During this period, O2Cons. decreased by approximately 50% from the near-shore station ‘A17’ (47.69 ± 9.03 mmol m−2 d−1) to the intermediate station ‘B17’ (23.85 ± 3.23 mmol m−2 d−1) (Figure 6). These O2 consumption values fall within the range previously reported for this region and are comparable to rates observed in other continental shelf systems worldwide [28,66,67]. The elevated O2Cons. in May 2017 indicates markedly higher aerobic OC remineralization in shelf sediment relative to August 2016.

Figure 6.

Spatial variability in (a) sediment oxygen consumption rates, (b) DIC flux from sediment (FDIC), and DIC production estimated by Redfield respiration ([PDIC]AR).

Using sediment O2 consumption rates, we calculated the aerobic remineralization of OC—expressed as DIC production ([PDIC]AR)—based on the stoichiometric equation of Redfield respiration: [(CH2O)106(NH3)16(H3PO4) + 138O2 ⇌ 106CO2 + 16HNO3 + H3PO4 + 122H2O]. The resulting [PDIC]AR can be utilized to trace the process. In August 2016, [PDIC]AR at station B16 was 10.37 mmol m−2 d−1 and decreased by ~18% at station C16 (Figure 6). In comparison, substantially higher rates were observed in May 2017: at station B17, [PDIC]AR was 18.32 mmol m−2 d−1 and doubled at station C17 (Figure 6). Overall, [PDIC]AR accounted for only 10–61% of the measured DIC fluxes from shelf sediment (FDIC), indicating that anaerobic pathways dominate aerobic OC remineralization in MIS sediment. In August 2016, FDIC increased nearly 2-fold from the intermediate station B16 (39.95 ± 13.13 mmol m−2 d−1) to the offshore station ‘C16’ (84.48 ± 10.53 mmol m−2 d−1) (Figure 6). In comparison, FDIC decreased under high-freshwater-discharge conditions in May 2017, declining ~11% from the near-shore station ‘A17’ (33.83 ± 3.06 mmol m−2 d−1) to the intermediate station ‘B17’ (30.17 ± 0.64 mmol m−2 d−1) (Figure 6). The only exception occurred at A17, where [PDIC]AR approximately matched with FDIC (Figure 6). This may be attributed to enhanced mixing in that station associated with increased freshwater discharge. The intense mixing may have deepened oxygen penetration in the sediment, allowing aerobic OC remineralization alone to sustain the observed FDIC. The sediment OC content and bottom-water oxygen conditions also likely contributed to the observed variability. The average OC content at stations A17 and B17 was ~33% lower than those at stations B16 and C16. Additionally, bottom-water O2 levels were higher in August 2016 (4.40 to 4.81 mg L−1) relative to May 2017, when near-hypoxic conditions prevailed (3.13 to 2.70 mg L−1). The combination of higher sediment OC and higher overlying-water O2 in August 2016 may have supported elevated aerobic OC remineralization, thereby increasing FDIC during that period. Other factors influencing FDIC include sediment porosity, temperature, salinity, and DIC concentrations in the overlying water. The substantial mismatch between [PDIC]AR and FDIC indicates that anaerobic remineralization processes—such as denitrification, Mn reduction, Fe reduction, sulphate reduction, and methanogenesis—play a major role in controlling DIC fluxes from sediment and, consequently, diminishing the long-term OC preservation in the shelf sediment. Although the available dataset does not allow for quantification of each pathway individually, their relative importance can be interfered through comparison with prior studies and the present dataset.

Anaerobic OC remineralization within the anoxic zone begins with denitrification, in which uses NO3− serves as the terminal electron acceptor (Figure 5). Potential sediment denitrification rates on the northern Gulf of Mexico shelf range from −0.85 ± 0.14 and 1.80 ± 0.33 mmol N m−2 d−1. Using the upper-end estimate of 2.13 mmol N m−2 d−1, the OC remineralization rate associated with sediment denitrification (or DIC production by denitrification, [PDIC]DN) was calculated using the stoichiometric relationship CH2O + 0.8NO3− + 0.8H+ → CO2 + 0.4N2 + 1.4H2O [68]. This equation indicates that 0.8 moles of NO3− are consumed per mole of OC oxidized, yielding 1 mole of CO2. This leads to a [PDIC]DN of 2.66 mmol m−2 d−1 in the Mississippi shelf sediment. When compared with the anaerobic component of the benthic DIC flux (i.e., FDIC—[PDIC]AR), denitrification accounts for only ~4–22% of anaerobically driven DIC flux from the shelf sediment. This finding suggests that additional anaerobic pathways substantially influence FDIC and thereby influence OC preservation in the shelf sediment.

In river-influenced continental shelf sediments, the roles of iron and manganese reductions in organic matter remineralization are well established [2]. In large river-dominated shelf systems such as the Mississippi, organic matter is efficiently remineralized in meter-thick, iron-rich muddy deposits. Frequent mixing with overlying oxygenated water promotes active redox cycling of manganese and iron, further enhancing remineralization processes [69]. Although manganese reduction rates have not yet been quantified in this shelf region, our datasets enable examination of how rFe influences OC preservation. Despite some heterogeneity between the natural and incubated sediment cores, we treat cores collected from the same station as comparable. This assumption allows for quantitative assessment of how rFe–organic carbon interactions shape OC preservation in shelf sediments.

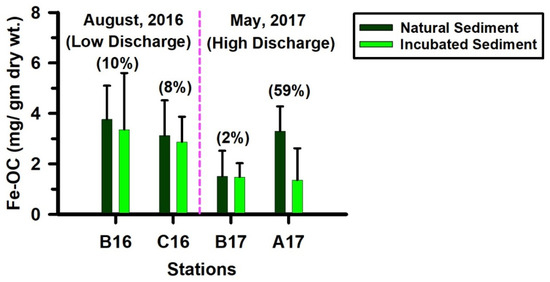

As described earlier, Fe-OC concentrations consistently decreased in the incubated sediments relative to the corresponding natural sediments. When integrated over the top 9 cm of the core, this loss was within approximately 10% at all stations except the near-shore station (A17) (Figure 7). At station A17, Fe-OC declined by roughly 59% in the incubated core relative to the natural core, indicating that rFe operates differently in preserving OC at the near-shore station compared with the more offshore stations B and C (Figure 7). At the offshore stations of the shelf, where sedimentary Fe and TOC concentrations are relatively low, the minor loss of Fe-OC during the incubation suggests that rFe may effectively contribute to long-term OC preservation. Similar patterns have been reported in other ecosystems. Kaiser and Guggenberger (2000) [60] documented substantial OC preservation by rFe in the soil, and Lalonde et al. (2012) [13] identified rFe as an efficient ‘rusty sink’ for OC, estimating that (19–45) × 1015 g of OC is globally preserved through Fe associations. More recently, Longman et al. (2022) [70] estimated Fe-OC burial rates of 17 and 11 Mt C yr−1 in continental shelf and deltaic/estuarine environments, respectively. In contrast, the large Fe-OC loss during the incubation at station A17 suggests that rFe-associated OC preservation is far less efficient in the near-shore environment. Several factors contribute to this pattern. Elevated freshwater discharge in May 2017 likely delivered substantial fresh organic matter and rFe in the near-shore site, conditions that may stimulate intense iron reduction and destabilize Fe-OC complexes. In deeper anoxic sediments, sulphate reduction and methanogenesis may also influence OC preservation, with sulphate reduction recognized as particularly important in the Louisiana coast region—often comparable in significance to iron reduction [71].

Figure 7.

Graph presenting Fe-OC levels in the top 9 cm depth of the natural and incubated sediment cores. The value inside the parenthesis indicates percentage loss of Fe-OC during incubation.

In summary, the study provides an initial assessment of the role of rFe in OC preservation within MIS sediments based on short-period incubation experiments. Our findings demonstrate the dual role of rFe, functioning both as preserving and facilitating the remineralization of sedimentary OC. The pronounced spatial variability observed across the shelf indicates that the influence of rFe on shelf OC dynamics is complex and highly site-specific. These results highlight the need for more-comprehensive, multi-seasonal investigations to clarify the mechanisms by which rFe regulates OC preservation in the shallow continental shelf region.

5. Conclusions

The present study provides an experimental assessment of organic carbon–rFe coupling in the Mississippi River-influenced shelf, offering new insights into the role of rFe in long-term organic carbon preservation in shelf sediments. During the sampling period, bottom-water oxygen concentrations in the MIS were low and approached hypoxic conditions. Although no clear vertical pattern in sedimentary rFe was observed, strong temporal variability emerged between August 2016 and May 2017. Sedimentary rFe levels were higher in May 2017 than in August 2016, likely due to inputs of fresher sediment associated with elevated freshwater discharge. The absence of pronounced vertical variability may be attributed to frequent sediment mixing on the shelf. Incubation experiments revealed a measurable loss of Fe-OC over short timescales, with prominent spatial differences across the shelf. Offshore stations showed relatively minor losses (10%), whereas near-shore stations experienced a substantially large loss (59%). These findings suggest that the effectiveness of rFe in promoting OC preservation varies across oceanographic settings. The minor loss of Fe-OC at the offshore stations indicates that rFe may better support long-term OC preservation in those environments, whereas this mechanism appears less effective in the near-shore environments. The pronounced spatial variability documented here introduces uncertainty regarding our current understanding of iron-mediated OC preservation at the global scale. This study examined the influence of rFe on OC preservation only during high- and low-river-discharge periods; thus, future studies should include further multi-seasonal investigations to better constrain OC-rFe interactions in the shallow continental shelf sediment.

Author Contributions

M.K.D.: analyzed the data and wrote the first draft of the manuscript; N.A.G.: collected the samples and performed experiments; K.M.: designed the study, conducted fund acquisition, and corrected the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work is partly supported by NSF Chemical Oceanography grant #1558957 and LSU Shell endowment fund to K.M.

Data Availability Statement

All the data used in the paper is presented in figures and tables.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the captain and crew of R/V Pelican and Jeff Krause for their support during sample collection. We are thankful Wokil Bam, Byron Ebner, Katie Bowes, and Jessica Landry for their support in this project. We thank Thomas Blanchard and Sara Gay from WBAS, LSU for their kind help in sample analysis. Special thanks to the staff at CAMD, Wanda LeBlanc at SIF, for their support in data collection.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Allison, M.A.; Bianchi, T.S.; McKee, B.A.; Sampere, T.P. Carbon burial on river-dominated continental shelves: Impact of historical changes in sediment loading adjacent to the Mississippi River. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2007, 34, L01606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKee, B.A.; Aller, R.C.; Allison, M.A.; Bianchi, T.S.; Kineke, G.C. Transport and transformation on river-influenced margins. Cont. Shelf Res. 2004, 24, 899–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Middelburg, J.J.; Levin, L.A. Coastal hypoxia and sediment biogeochemistry. Biogeosciences 2009, 6, 1273–1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, H.; Maiti, K. The importance of fauna-mediated sediment O2 consumption in the NGOM hypoxic zone. Front. Mar. Sci. 2024, 12, 1532999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aller, R.C.; Blair, N.E. Early diagenetic remineralization of sedimentary organic C in the Gulf of Papua deltaic complex (Papua New Guinea): Net loss of terrestrial C and diagenetic fractionation of C isotopes. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 2004, 68, 1815–1825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aller, R.C.; Blair, N.C.; Xia, Q.; Rude, P.D. Remineralization rates, recycling and storage of carbon in Amazon shelf sediments. Cont. Shelf Res. 1996, 16, 753–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutta, M.K.; Chowdhury, C.; Jana, T.K.; Mukhopadhyay, S.K. Dynamics and exchange fluxes of methane in the estuarine mangrove environment of Sundarbans, NE coast of India. Atmos. Environ. 2013, 77, 631–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutta, M.K.; Mukherkjee, R.; Jana, T.K.; Mukhopadhyay, S.K. Biogeochemical dynamics of exogenous methane in a mangrove estuary. Mar. Chem. 2015, 170, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beam, J.P.; Scott, J.J.; McAllister, S.M.; Chan, C.S.; McManus, J.; Meysman, F.J.R.; Emerson, D. Biological rejuvenation of iron oxides in bioturbated sediments. ISME J. 2018, 12, 1389–1394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gini, C.; Jamieson, J.W.; Reeves, E.P.; Gartman, A.; Barreyre, T.; Babechuk, M.G.; Jørgensen, S.L.; Robert, K. Iron oxyhydroxide-rich hydrothermal deposits at the Fåvne vent field. Geochem. Geophys. Geosystems 2024, 25, e2024GC011481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poulton, S.W.; Raiswell, R. Characteristics of iron oxides in riverine and meltwater sediments. Chem. Geol. 2005, 218, 203–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Zee, C.; Roberts, D.R.; Rancourt, D.G.; Slomp, C.P. Nano-goethite in lake and marine sediments. Geology 2003, 31, 993–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lalonde, K.; Mucci, A.; Ouellet, A.; Gélinas, Y. Preservation of organic matter promoted by iron. Nature 2012, 483, 198–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canfield, D.E. The geochemistry of river particulates from the continental USA: Major elements. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 1997, 61, 3349–3365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eglinton, T. A rusty carbon sink. Nature 2012, 483, 165–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burdige, D.J. The biogeochemistry of manganese and iron reduction in marine sediments. Earth-Sci. Rev. 1993, 35, 249–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghaisas, N.A.; Maiti, K.; Roy, A. Iron-mediated organic matter preservation in the Mississippi River–influenced shelf sediments. J. Geophys. Res. Biogeosci. 2021, 126, e2020JG006089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabalais, N.N.; Turner, R.E.; Wiseman, W.J., Jr. Hypoxia in the Gulf of Mexico. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 2002, 33, 235–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutta, M.K.; Forsman, J.; Maiti, K. Estimating air–sea CO2 fluxes in the northern Gulf of Mexico shelf utilizing 226Ra–222Rn disequilibria. J. Geophys. Res. Ocean. 2025, 130, e2025JC022794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, N.D.; Wiseman, W.J.; Rouse, L.J.; Babin, A. Controls on the Mississippi River plume. J. Coast. Res. 2005, 216, 1228–1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianchi, T.S.; Mitra, S.; McKee, B.A. Sources of terrestrially derived organic carbon in lower Mississippi River and Louisiana shelf sediments. Mar. Chem. 2002, 77, 211–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, J.E.; Cai, W.-J.; Raymond, P.A.; Bianchi, T.S.; Hopkinson, C.S.; Regnier, P.A.G. The changing carbon cycle of the coastal ocean. Nature 2013, 504, 61–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fry, B.; Justić, D.; Riekenberg, P.; Swenson, E.M.; Turner, R.E.; Wang, L.; Pride, L.; Rabalais, N.N.; Kurtz, J.C.; Lehrter, J.C.; et al. Carbon dynamics on the Louisiana continental shelf. Estuaries Coasts 2015, 38, 703–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, K.; Wang, J.; Li, C.; Bentley, S.J.; Miner, M.D. Geomorphic and hydrodynamic impacts on sediment transport on the inner Louisiana shelf. Geomorphology 2022, 398, 108022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Cai, W.-J.; Huang, W.-J.; Wang, Y.; Chen, F.; Murrell, M.C.; Lohrenz, S.E.; Jiang, L.-Q.; Dai, M.; Hartmann, J.; et al. Carbon dynamics in the Mississippi River plume. Limnol. Oceanogr. 2012, 57, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.-J.; Cai, W.-J.; Wang, Y.; Lohrenz, S.E.; Murrell, M.C. The CO2 system on the Mississippi River–dominated shelf. J. Geophys. Res. Ocean. 2015, 120, 1429–1445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reiman, J.H.; Xu, Y.J.; He, S.; DelDuco, E.M. Metals export from the Mississippi–Atchafalaya River system. Chemosphere 2018, 205, 559–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghaisas, N.A.; Maiti, K.; White, J.R. Coupled iron and phosphorus release from seasonally hypoxic Louisiana shelf sediment. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 2019, 219, 81–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clower, P.O.; Maiti, K.; Bowles, M. Contrasting organic carbon respiration pathways in coastal wetlands undergoing accelerated sea level changes. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 949, 174898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upreti, K.; Maiti, K.; Rivera-Monroy, V.H. Microbial phosphorus mobilization in Louisiana wetlands. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 651, 122–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wentworth, C.K. A scale of grade and class terms for clastic sediments. J. Geol. 1922, 30, 377–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedges, J.I.; Stern, J.H. Carbon and nitrogen determinations of carbonate-containing solids. Limnol. Oceanogr. 1984, 29, 657–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostka, J.E.; Luther, G.W. Partitioning and speciation of solid-phase iron in saltmarsh sediments. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 1994, 58, 1701–1710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, M.; McManus, J.; Goñi, M.A.; Chase, Z.; Borgeld, J.C.; Wheatcroft, R.A.; Muratli, J.M.; Megowan, M.R.; Mix, A. Reactive Fe and Mn near small mountainous rivers. Cont. Shelf Res. 2013, 54, 67–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cutter, G.; Andersson, P.; Codispoti, L.; Croot, P.; Francois, R.; Lohan, M.; Rutgers van der Loeff, M. Sampling and Sample-Handling Protocols for GEOTRACES Cruises; Geotraces: Toulouse, France, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Cai, W.-J.; Wang, Y. The chemistry, fluxes, and sources of CO2 in estuarine waters of the Satilla and Altamaha Rivers, Georgia. Limnol. Oceanogr. 1998, 43, 657–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, Y.; Liu, X.; Liu, Q.; Kong, F.; Lan, K.; Chang, X.; Zhang, M.; Zhuang, G.; Wang, H. Source–sink process of reactive iron in the Central Yellow Sea. Chem. Geol. 2025, 683, 122780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, F.; Liu, X.; Li, A.; Dong, J.; Wang, H.; Zhuang, G.; Zhang, Z.; Li, C. Depositional control on reactive iron in East China Sea sediments. Mar. Geol. 2024, 475, 107358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, W.-W.; Zhu, M.-X.; Yang, G.-P.; Li, T. Iron geochemistry and OC preservation in ECS and SYS sediments. J. Mar. Syst. 2018, 178, 62–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Dong, L.; Sui, W.; Niu, M.; Cui, X.; Hinrichs, K.-U.; Wang, F. Cycling and persistence of iron-bound organic carbon in subseafloor sediments. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 6370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, B.; Yao, P.; Bianchi, T.S.; Shields, M.R.; Cui, X.; Zhang, X.; Huang, X.Y.; Schroeder, C.; Zhao, J.; Yu, Z. Reactive iron in preservation of terrestrial OC in estuarine sediments. J. Geophys. Res. Biogeosci. 2018, 123, 3556–3569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, M.-X.; Hao, X.-C.; Shi, X.-N.; Yang, G.-P.; Li, T. Iron speciation in ECS continental shelf sediments. Appl. Geochem. 2012, 27, 892–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egger, M.; Hagens, M.; Sapart, C.J.; Dijkstra, N.; van Helmond, N.A.; Mogollón, J.M.; Risgaard-Petersen, N.; van der Veen, C.; Kasten, S.; Riedinger, N.; et al. Iron oxide reduction in methane-rich Baltic Sea sediments. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 2017, 207, 256–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Zhu, M.-X.; Yang, G.-P.; Ma, W.-W. Reactive iron and Fe-bound OC in Bohai Sea vs. Yellow Sea. J. Geophys. Res. Biogeosci. 2019, 124, 79–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.; Guo, X.; Zhao, J.; Li, D.; Hu, J.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, C.; Han, Z.; Sun, W.; Sun, Y.; et al. Reactive iron in Prydz Bay sediments and implications for OC preservation. Front. Mar. Sci. 2023, 10, 1142061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olson, L.; Quinn, K.A.; Siebecker, M.G.; Luther, G.W.; Hastings, D.; Morford, J.L. Trace metal diagenesis in sulfidic sediments. Chem. Geol. 2017, 466, 530–546. [Google Scholar]

- Aller, R.C.; Mackin, J.E.; Cox, R.T. Diagenesis of Fe and S in Amazon inner shelf muds: Apparent dominance of Fe reduction and implications for the genesis of ironstones. Cont. Shelf Res. 1986, 6, 263–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvadó, J.A.; Tesi, T.; Andersson, A.; Ingri, J.; Dudarev, O.V.; Semiletov, I.P.; Gustafsson, Ö. Permafrost OC resequestered by reactive Fe on Arctic shelves. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2015, 42, 8122–8130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faust, J.; Ascough, P.; Hilton, R.; Stevenson, M.; Hendry, K.; März, C. Preservation of contemporary marine OC by iron in Arctic shelf sediments. Environ. Res. Lett. 2022, 18, 014006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beckler, J.S.; Kiriazis, N.; Rabouille, C.; Stewart, F.J.; Taillefert, M. Importance of microbial iron reduction in deep sediments of river-dominated continental margins. Mar. Chem. 2016, 178, 22–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Huang, H.; Dong, D.; Zhang, S.; Yan, R. Role of iron minerals in OC preservation in mangrove sediments. Water 2024, 16, 1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shields, M.R.; Bianchi, T.S.; Gélinas, Y.; Allison, M.A.; Twilley, R.R. Enhanced terrestrial carbon preservation by reactive iron. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2016, 43, 1149–1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jilbert, T.; Asmala, E.; Schröder, C.; Tiihonen, R.; Myllykangas, J.-P.; Virtasalo, J.J.; Kotilainen, A.; Peltola, P.; Ekholm, P.; Hietanen, S. Impacts of flocculation on iron distribution in estuarine sediments. Biogeosciences 2018, 15, 1243–1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tagliabue, A.; Bowie, A.; Boyd, P.; Buck, K.N.; Johnson, K.S.; Saito, M.A. The role of iron in ocean biogeochemistry. Nature 2017, 543, 51–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vosteen, P.; Spiegel, T.; Gledhill, M.; Frank, M.; Zabel, M.; Scholz, F. Fate of reactive iron at the land–ocean interface: Amazon shelf. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 2022, 23, e2022GC010543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corbett, D.R.; McKee, B.; Duncan, D. An evaluation of mobile mud dynamics in the Mississippi River deltaic region. Mar. Geol. 2004, 209, 91–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adhikari, P.L.; Maiti, K.; Overton, E.B.; Rosenheim, B.E.; Marx, B.D. Distributions and accumulation rates of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in the Northern Gulf of Mexico sediments. Environ. Pollut. 2016, 212, 413–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zang, Z.; Xue, Z.G.; Bao, S.; Chen, Q.; Walker, N.D.; Haag, A.S.; Ge, Q.; Yao, Z. Sediment dynamics during Hurricane Gustav. Ocean Model. 2018, 126, 29–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, P.; Maiti, K.; McManus, J. Lead-210 and Polonium-210 in the NGOM hypoxic zone. Mar. Chem. 2015, 169, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, K.; Guggenberger, G. The role of DOM sorption in OM preservation in soils. Org. Geochem. 2000, 31, 711–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCoy, C.A.; Corbett, D.R.; McKee, B.A.; Top, Z. Submarine groundwater discharge on the Louisiana shelf. J. Geophys. Res. 2007, 112, C03013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, C.; Smith, L.; Maji, R. Hydrogeological modeling of groundwater discharge. J. Geophys. Res. 2007, 112, C03014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, A.M. Fresh and saline groundwater discharge to the ocean. Water Resour. Res. 2005, 41, W02016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trefry, J.H.; Metz, S.; Nelsen, T.; Trocine, R.P.; Eadie, B.J. POC transport by the Mississippi River. Estuaries 1994, 17, 839–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sampere, T.P.; Bianchi, T.S.; Wakeham, S.G.; Allison, M.A. OM sources on the Louisiana margin. Cont. Shelf Res. 2008, 28, 2472–2487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarthy, M.J.; Newell, S.E.; Carini, S.A.; Gardner, W.S. Denitrification dominates sediment N removal. Estuaries Coasts 2015, 38, 2279–2294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, G.; Liu, S.; Zhu, Z.; Zhai, W.; Zhu, C.; Zhang, J. Sediment oxygen consumption on ECS and YS shelves. Deep-Sea Res. II 2016, 124, 53–63. [Google Scholar]

- Krumins, V.; Gehlen, M.; Arndt, S.; Van Cappellen, P.; Regnier, P. DIC and alkalinity fluxes from coastal sediments. Biogeosciences 2013, 10, 371–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devereux, R.; Lehrter, J.C.; Beddick, D.L.; Yates, D.F.; Jarvis, B.M. Manganese, iron, and sulfur cycling in Louisiana continental shelf sediments. Cont. Shelf Res. 2015, 99, 46–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longman, J.; Faust, J.C.; Bryce, C.; Homoky, W.B.; März, C. Organic carbon burial with reactive iron. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 2022, 36, e2022GB007447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eldridge, P.M.; Morse, J.W. A diagenetic model for sediment–seagrass interactions. Mar. Chem. 2008, 70, 89–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).