Abstract

The frequency and intensity of floods increase with global climate change. Strengthening the resilience of farmers to disasters, in particular to mitigate flood risks, has become an important policy issue. Increasing the livelihood resilience of farmers to enhance their disaster preparedness has become the main form of coping with flood risk. However, few studies have explored the correlation between farmers’ livelihood resilience and disaster preparedness. Using data from a survey of 540 rural households conducted in July 2021 across nine towns in three counties in Sichuan Province, we construct an indicator system for evaluating the farmers’ livelihood resilience in flood risk areas. The relationship between farmers’ livelihood resilience and their disaster preparedness is studied using the tobit model. The results show that farmers’ livelihood resilience is composed of multiple dimensions, with self-organization capacity scoring the highest (0.541), followed by learning ability (0.303), and buffer capacity scoring the lowest (0.223). Additionally, the level of trust in society and the possibility of suffering from floods in the research area have a noticeable positive effect on farmers’ decision-making related to disaster preparedness. The more farmers trust in society and the greater the likelihood of exposure to flood risk is, the more they tend to be prepared for risk avoidance. Furthermore, farmers’ livelihood resilience is positively associated with their overall disaster preparedness. Specifically, both buffer capacity and learning ability influence emergency disaster preparedness and knowledge and skill preparation; self-organization capacity affects only knowledge and skill preparation. These results suggest procedures to enhance farmers’ livelihood resilience and further strengthen preparedness for disasters such as floods.

1. Introduction

Since the beginning of the 21st century, global warming has led to frequent floods around the world. In its sixth assessment report, the Synthesis Report, the United Nations Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) stated that extreme weather events are “more frequent and intense” today, with effects on almost half of the population in areas that are highly susceptible to climate change. According to the United Nations Office of Disaster Risk Reduction (UNDRR) statistics report, floods were the most frequent natural disasters over the past 20 years (2000–2019) and caused the most deaths. The recent catastrophic floods indicate this trend: in July 2025, an unprecedented flash flood occurred in Texas, USA, causing at least 132 deaths; similarly, in October 2024, the Valencia region of Spain experienced a year-long rainfall in just 8 h, flooding towns and destroying infrastructure, resulting in 158 deaths. In South Asia, the monsoon floods in Pakistan in 2025 have caused over 300 deaths. These events highlight how climate change amplifies flood risks in different regions, from urban centers to mountainous areas.

One of the countries most affected by flooding is China []. In recent years, rain and flood disasters have occurred frequently in China, causing an average annual economic loss accounting for 3.15% of the total output of the national economy []. According to Ministry of Emergency Management of the People’s Republic of China, flood disasters affected 33.853 million people nationwide in 2022, with rural populations accounting for over 60% of the total affected individuals, resulting in direct economic losses of CNY 128.9 billion []. These disasters seriously threaten the safety of people’s lives and property, especially causing sustained impacts on the livelihoods of rural households mainly engaged in agriculture. Sichuan Province is one of the provinces in China with the highest risk of flood disasters. In 2022, floods and waterlogging disasters in Sichuan Province affected 2.225 million people, with an affected area of 55,000 hectares of crops and a direct economic loss of CNY 4.9 billion []. Sudden climatic disasters are closely associated with climate change, exacerbating hazards to agricultural production [] and severely affecting the livelihoods of rural households. Therefore, how farmers might effectively mitigate flood risks and enhance disaster resilience has become an urgent research topic.

When farmers encounter stresses from climate change, livelihood resilience can help them restore their livelihoods []. Livelihood resilience, which primarily reflects an individual’s ability to deal with external pressures and restore their original livelihood status, is an integral part of a sustainable livelihood [,,]. For farmers, livelihood resilience is particularly concerned with their ability to maintain or even upgrade their livelihood systems under various shocks and disruptions. This ability depends on their resource endowments, which enables them to make specific choices and use combinations of limited resources in order to avoid or minimize losses []. Numerous studies have verified the extremely high vulnerability of farmers to extreme weather [,,]. Increasing the resilience of farmers’ livelihoods is not only conducive to effective prediction and response to disasters caused by climate change, but it can also lower their livelihood vulnerability and enhance sustainable well-being by maintaining or improving their development capabilities and assets while retaining the sustainability of the environment and agricultural economy [,,,]. Thus, identifying farmers’ livelihood resilience in flood risk regions and guiding them to proactively increase their own livelihood resilience can provide critical support while improving the effectiveness of disaster avoidance and risk prevention [,].

Farmers’ disaster preparedness reflects their capacity to take adaptive measures to withstand and recover from natural disasters [,], and plays a crucial role in enhancing household resilience against flood risks []. Due to agriculture being the primary source of livelihood for most farmers, in the context of climate uncertainty, farmers must adopt disaster prevention strategies that are contextually adapted to maintain sustainable development. Existing studies demonstrate that farmers’ disaster preparedness plays a crucial role in mitigating flood risks, yet its effectiveness shows significant context dependency [,,]. This situational dependence leads to differences in the selection of disaster preparedness indicators in different studies. Therefore, researchers have adopted multiple indicators to measure disaster preparedness: storing emergency items such as food and water [], fortifying houses and building levees [], purchasing insurance against natural disasters [], and so on. Some scholars have also studied the impact of threat cognition and emotional control on individuals’ disaster preparedness ability from the perspective of psychological preparation [] or focused on the influence of farmers’ disaster knowledge mastery on their disaster avoidance behavior decisions []. Although a standardized evaluation space has not yet been established, the existing literature still provides useful references for this study.

Current studies mostly focus on the livelihood resilience and adaptation strategies of farmers [,,], especially livelihood resilience and risk perception [,,], and the risk perception and disaster prevention strategies [,,] of farmers in the face of different types of natural disasters (such as floods, droughts, or earthquakes). However, fewer studies have addressed the impact of livelihood resilience and disaster preparedness on farmers. Therefore, as the main group most vulnerable to the risk of floods, how farmers can utilize their livelihood resilience to prepare for disasters and reduce flood hazards is an issue that deserves to be further explored. Hence, this study aims to evaluate the respective characteristics of livelihood resilience and disaster preparedness capacity of farmers in flood-prone areas. It also analyzes the correlation between livelihood resilience and disaster preparedness and provides a practical basis for enhancing the sustainable development capacity of farmers. Compared with existing research, the innovation of this study lies in revealing the driving mechanism of farmers’ livelihood resilience on their disaster preparedness behavior, filling the research gap in the existing literature on the direct correlation between resilience and disaster preparedness. In addition, micro data based on first-hand surveys also provide a practical basis for activating farmers’ endogenous motivation for disaster prevention.

The paper is arranged as follows. The Section 2 is a literature review and statement of research hypotheses. The Section 3 is the research design, which includes three aspects: research model and data sources, variable selection and measurements, and methods. The Section 4 constructs an econometric model of the effects of the farmers’ livelihood resilience on disaster preparedness in flood risk areas and analyzes its results. The Section 5 is the discussion of the results. The Section 6 is the conclusion.

2. Literature Review and Research Hypotheses

2.1. Literature Review

The term “resilience” was first introduced into the field of ecology by Rahman (2023) []. It refers to the ability of an ecosystem to confront natural or human-induced changes, to adapt to uncertainties and disturbances, and to remain in a particular state [,]. Resilience implies not only resisting and adapting to shocks but also upgrading and developing after the shocks []. Scholars recognize that the concept of resilience needs to focus more on people’s livelihoods if it is to help poor and vulnerable groups achieve endogenous development []. Livelihood resilience of farmers refers to their ability to preserve their well-being in coping with environmental threats, and economic and social crises []. Due to the vulnerability of farmers to natural disasters in their agricultural activities, how farmers use their livelihoods to avoid or deal with disasters has become a key concern of scholars. For constructing livelihood resilience, scholars differ slightly on research approaches, but ref. [] proposed a livelihood resilience analysis framework that has been widely recognized and applied domestically and internationally. This framework—composed of three parts: buffer capacity, self-organization capacity, and learning ability—laid a foundation for subsequent studies. For example, ref. [] proposed a framework for estimating the resilience of disaster-related resettlers from a livelihood perspective. Ref. [] incorporated another dimension in evaluating the relationship between livelihood strategies and adaptive capacity in mountain pastoralist households.

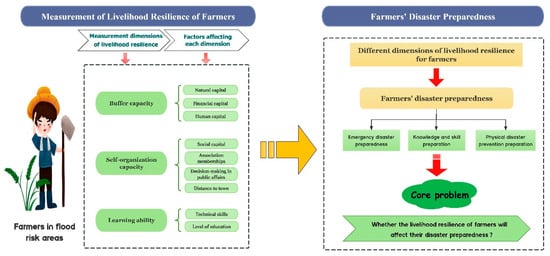

This study develops a theoretical framework for the impact of livelihood resilience of farmers on disaster preparedness in the context of flood risk by taking buffer capacity (natural capital, financial capital, human capital), self-organization capacity (social capital, rural cooperative organizations, decision-making in public affairs, and distance to town) and learning ability (technical skills and level of education) as dimensions to assess the resilience level of farmers in their livelihoods. We take emergency disaster preparedness, knowledge and skill preparation, and physical disaster prevention preparation as dimensions for assessing the level of farmers’ disaster preparedness. These are depicted in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

The theoretical framework of this research.

2.2. Research Hypotheses

We divide the livelihood resilience of farmers into three primary indicators: buffer capacity, self-organization capacity, and learning ability, and use second-level indicators to specifically evaluate these three dimensions.

2.2.1. Mechanistic Analysis of Buffer Capacity Affecting Farmers’ Disaster Preparedness

The buffer capacity of farmers refers to their ability to buffer changes and utilize emerging opportunities to obtain better livelihood outcomes []. According to the sustainable livelihood framework proposed by the Department For International Development [], the construction of buffering capacity relies on the synergistic effect of five types of livelihood capital []. This study combines the livelihood characteristics of farmers in flood scenarios and selects three types of core capital as the characterization dimensions of buffering capacity, namely natural capital, financial capital, and human capital. Specifically:

- (1)

- Natural capital, centered on land, is the material basis for the survival of farmers, including natural resources and services that are beneficial to the livelihoods of farmers []. Here, “the land area that farmers are operating” is used to characterize natural capital. Concretely, the larger the land area is that farmers are operating, the greater the scope is for increasing the harvest of agricultural products, which, in turn, affects farmers’ ability to have sufficient economic capacity to prepare for disaster preparedness.

- (2)

- Referring to [,,], we selected “owning valuable fixed assets at home” and “annual household income” to represent financial capital. The greater the number of a rural household’s valuable permanent assets is, the stronger their ability is to protect against risk, and hence the greater the farmer’s disaster preparedness. From another perspective, the higher the annual household income is, the more capital the farmer has to invest in agricultural production and operation, which increases the number of agricultural products that farmers can produce and can improve their income.

- (3)

- Human capital includes farmers’ family labor force, physical health status, and so on [,]. In this paper, we use “number of household labor force” and “household dependency ratio” to characterize human capital. Specifically, the more labor force there is in rural households, the greater the likelihood is that members of the household can go out to engage in non-agricultural activities, and the greater the diversity of their livelihoods, which enhances their buffer capacity. In rural households, the larger the dependency ratio is, the heavier the burden will be, which has a negative impact on household savings, and the weaker the disaster preparedness.

Hypothesis 1.

There is a positive correlation between farmers’ buffer capacity and disaster preparedness, as well as its three dimensions (emergency disaster preparedness, knowledge and skill preparation, and physical disaster prevention preparation).

2.2.2. Mechanistic Analysis of Self-Organization Capacity Affecting Farmers’ Disaster Preparedness

Self-organization capacity primarily reflects the impact of individual adaptability, power, and interaction with society on resilience []. In this paper, we use “social capital”, “association membership”, “decision-making in public affairs”, and “distance to town” to characterize self-organization capacity, as follows.

- (1)

- The wider the social network of farmers is, the more conducive it is to cultivate self-organization capacity, which is a deep-rooted motivation for farmers to avoid risks and disasters [,]. In this study, social capital is characterized by “the number of relatives and friends working in the public sector” and “the number of relatives and friends who come and go during the Chinese New Year”. The more frequent and the closer the farmer’s contact is with relatives and friends, as well as the more relatives and friends working in the public sector, the richer is the farmers’ interpersonal resources; that is, the more likely they are to have access to more resources or assistance, which to a large extent can help them prepare for disasters.

- (2)

- Agricultural cooperative organizations are able to concentrate dispersed farmers and combine their efforts to cope with market competition or various types of natural risks [,]. The more farmers participate in various cooperative organizations, the more they can rely on the strength of the organization’s members in the face of sudden floods; they can respond to the floods through collective action to mitigate the repercussions of the floods. Furthermore, decision-making in public affairs is a key factor influencing farmers’ self-organization capacity. The greater the participation of farmers in such decision-making processes, the more likely it is that their political status will be strengthened and their influence in the village will grow, thereby enhancing their self-organization capacity.

- (3)

- The distance to town directly reflects the convenience of farmers’ lives. The closer the rural household is to a town, the more convenient it is for them to move around, which enhances the farmer’s self-organization capacity [].

Hypothesis 2.

There is a positive correlation between farmers’ self-organization capacity and disaster preparedness and its three dimensions.

2.2.3. Mechanistic Analysis of Learning Ability Affecting Farmers’ Disaster Preparedness

Learning ability can be interpreted as the individual’s ability to learn from previous practices and knowledge in order to respond and adjust to external stressors [,]. In this paper, we use “technical skills” and “level of education “ to represent learning ability. Specifically:

- (1)

- The more technical skills that are held by farmers, the more likely they are to utilize their knowledge and skills to cope with disasters and flexibly address immediate dilemmas.

- (2)

- Education status of farmers has two aspects: the education level of the household head, and the number of people with a high school education or above in the family. In particular, the more educated a household head is, the more likely they are to have diverse and high-level technical skills, which can help the household prevent disaster or mitigate the negative impacts of disasters []. The more people there are in rural households with higher education, the more likely they are to access and capture a relatively large amount of disaster information and screen and analyze information, so as to adjust livelihood strategies in a timely manner to achieve effective disaster preparedness.

Hypothesis 3.

There is a positive correlation between farmers’ learning ability and disaster preparedness and its three dimensions.

3. Data and Methods

3.1. Study Area

Sichuan Province is in southwest China upstream of the Yangtze River. Its subtropical monsoon climate results in pronounced seasonal precipitation variability, with uneven rainfall distribution frequently leading to flood disasters []. In addition, Sichuan also has low-lying and flat terrain with poor drainage, which is one of the factors that make it prone to flooding []. As a major agricultural province and high-risk area for floods in China, the rural population and agricultural production in Sichuan Province are facing serious flood threats. According to statistics, from 2009 to 2018, Sichuan was affected by floods, with an average annual direct economic loss of CNY 23.526 billion and an average annual number of affected people of 10.721 million. Rural areas were particularly severely affected [,]. According to the 2022 Statistical Bulletin of the Sichuan Provincial Bureau of Statistics, the affected area of crops for the whole year was 616,000 hectares, and direct economic losses of CNY 4.9 billion were caused by floods and geological disasters [].

This study focuses on Gao County, Jiajiang County, and Yuechi County as the research areas. The research area is concentrated in the central and eastern regions of the Sichuan Basin, with well-developed water systems in the three counties, including the Nanguang River, Qingyi River, and Qujiang River. Influenced by the monsoon climate, these areas are prone to heavy rainstorms and flood disasters during the summer months from June to August. To provide a clearer understanding of the geographical features of the research areas, the following descriptions of Gao County, Jianjiang County, and Yuechi County are given: Gao County is located on the southern edge of the Sichuan Basin, with a terrain sloping from northwest to southeast. The Nanguang River runs through the entire area, and the terrain is mainly hilly and plain, with poor drainage and a high risk of flooding. Jiajiang County is located in the southwest of Sichuan Basin. The Qingyi River flows through the county, and the river basin area is large, so it is easy to cause floods in rainstorm in summer. Yuechi County is in the northeastern part of the Sichuan Basin. The Qujiang River flows through the county, and the hilly terrain, combined with frequent summer rainstorms, results in frequent flood disasters that severely affect the rural population and agricultural production.

3.2. Data Collection

We used data from a questionnaire survey and in-depth interviews conducted in July 2021 in nine towns of Gao County (Jiale, Qingling, Shengtian), Jiajiang County (Ganjiang, Huangtu, Mucheng), and Yuechi County (Fulong, Luodu, Zhonghe). The research group randomly selected 50 villagers in Jiajiang to conduct a pre-survey, on the basis of which the original questionnaire was modified and improved, to finally form the official questionnaire. The surveyed farmers were selected by stratified and equal probability random sampling. The flood risk areas in Sichuan were divided into three groups according to the rainfall, and three sample villages in the Gao, Jiajiang, and Yuechi counties were chosen. In light of the economic development status of the sample counties, in each sample county, one township was randomly selected as the sample county town. Because of the economic development circumstances of each county and town, one village was chosen at random from each sample county as the sample village. Finally, 20 farmers were randomly selected from each sample village as the sample farmers. Based on the above process, after excluding invalid samples, we obtained a total of 540 valid questionnaires from nine towns in three counties.

The questionnaire mainly includes five parts: basic information of farmers (gender, age, marriage, education, and so on), family livelihood capital and livelihood strategies (corresponding to the five major capitals of nature, finance, material, human, and society), climate change risk perception (risk awareness situation), natural disaster insurance (insurance experience, and so on), disaster preparedness and behavioral choice willingness (flood perception, flood information acquisition, disaster avoidance strategies, and so on).

3.3. Variable Selection

3.3.1. Core Explanatory Variables

The core explanatory variable of this research is the livelihood resilience of farmers. The three dimensions of buffer capacity, self-organization capacity, and learning ability are used to measure the livelihood resilience of farmers, and a total of 14 subtle indicators are used as specific measurement standards (Table 1). Buffer capacity is represented by three variables (natural capital, financial capital, and human capital); the land area being operated by farmers represents natural capital; valuable fixed assets at home and annual household income represent financial capital; the total household labor force and the household dependency ratio represent human capital. Self-organization capacity is represented by four factors: social capital, association membership, decision-making in public affairs, and distance to town. Learning ability is represented by two variables: technical skills and education. All three dimensions are expected to affect the resilience levels of farmers in their livelihoods, and the greater the value of the indicator is, the stronger the livelihood resilience of farmers is expected to be. Otherwise, the weaker it is.

Table 1.

Measurement index of the livelihood resilience of farmers.

3.3.2. Dependent Variable

The dependent variable is the disaster preparedness of farmers. Emergency disaster preparedness, knowledge and skill preparation, and physical disaster prevention preparation were selected as three primary indicators to weigh the farmers’ level of disaster preparedness, and a total of 12 indicators as specific evaluation criteria (Table 2). Among them, emergency disaster preparedness is represented by four variables: whether the family usually has emergency supplies, whether the emergency preparedness items are sufficient, whether insurance is purchased, and whether one is willing to prepare for disaster avoidance. Knowledge and skill preparation is represented by five variables: whether family members take the initiative to learn basic knowledge about disaster prevention, whether they have a way to knowledge, whether they participate in disaster knowledge training, whether they participate in disaster emergency drills, and whether they apply the knowledge to their lives. Preparation for physical disaster prevention is represented by three variables: whether the house if reinforced, whether valuables are stored, and whether harmful and toxic materials are safely stored. All three dimensions affect farmers’ disaster preparedness, and the larger the index value is, the better the farmers are prepared for disaster. Otherwise, the less prepared they are.

Table 2.

Measurement index of farmers’ disaster preparedness.

3.3.3. Control Variables

To exclude confounding factors, individual characteristics, family characteristics, and subjective perception of farmers are incorporated as control variables (Table 3). Individual characteristics include gender, age, education level, and marital status; family characteristics include residence time, flood experience, and family building structure. The subjective perception of farmers includes their trust level in the majority of the community, individual perception of the severity of the flood, the potential negative impact of the flood, and the threat caused by the flood.

Table 3.

Control variable definitions and descriptive statistics.

3.4. Methods

3.4.1. Entropy Method Determines the Index Weights

The entropy method was used to construct the farmers’ livelihood resilience index. This method determines the weights of each indicator in accordance with the size of the information it provides []. The core explanatory variables are divided into three dimensions that affect the livelihood resilience of farmers to varying degrees. Moreover, since the data are captured in the actual survey, it is suitable to adopt an objective weighting method, as described in the following procedure:

(1) Data standardization

The raw data are standardized by the range-difference method to eliminate dimensionality.

Positive indicator processing:

Negative indicator processing:

where i = 1, 2, …540; i.e., j = 1, 2, …14. Xij is the original value of the j indicator of the i-th sample; X′ij is the standardized indicator value with a range of [0, 1]; maxXij is the maximum value of the jth indicator; minXij is the minimum value of the jth indicator.

(2) Determine the weights of the indicator and criterion, as follows.

Calculate Pij of the share of indicator j in the sum of all indicators j:

Calculate ej, the information entropy of the jth indicator:

Calculate dj, the redundancy based on information entropy ej:

Calculate indicator weight Wj:

Calculate the comprehensive score Si:

3.4.2. Tobit Model Regression Analysis

The tobit model is a regression in which the range of the dependent variable is constrained in some way [,,]. The dependent variable in this research takes values between 0 and 1, and we use the tobit model to analyze the impact of livelihood resilience of farmers on disaster preparedness. The tobit regression model with livelihood resilience as the core explanatory variables and disaster preparedness of farmers as the dependent variable is as follows:

where Yi stands for disaster preparedness, which can be emergency disaster preparation, knowledge and skill disaster preparedness, and physical disaster prevention preparation. Xi represents the livelihood resilience of farmers, which can be divided into buffer capacity, self-organization capacity, and learning ability; Controli represents a selected series of control variables; α is the constant term; β1i and β2i are the parameters to be estimated for each influencing factor; ε is the random disturbance term, i = 1, 2, 3…n.

Besides, to avoid the problem of multicollinearity between the core explanatory variables overfitting the model and affecting the regression analysis, we used SPSS 24.0 to perform multicollinearity tests on the sample values of the independent variables. It is generally accepted that if the variance inflation factor (VIF) is greater than 10, there is a multicollinearity effect []. In our results, the VIF value for all indicators is less than 10, and the maximum VIF value of a single indicator is 2.101, showing that there is no problem of multicollinearity between the variables, and the assumption that variables are independent is satisfied.

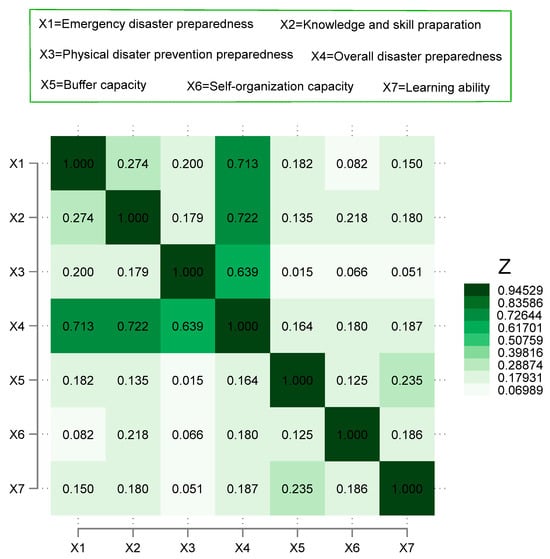

This study used the entropy method to calculate the correlation coefficients between the livelihood resilience and disaster preparedness of farmers in flood risk areas. The correlation coefficient matrix is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Model relates to the correlation coefficient matrix of core variables.

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Statistics of Key Variables

This study conducted descriptive statistical analysis of farmers’ livelihood resilience, disaster preparedness, and control variables using Stata 17.0 based on survey data, with results presented in Table 1, Table 2 and Table 3.

Table 1 reports the means and standard deviations of livelihood resilience indicators across three dimensions: buffer capacity, self-organization capacity, and learning ability. In terms of buffering capacity, the average annual income of farmers is CNY 929,900, but the standard deviation is as high as 16.87, indicating a significant income gap. The average labor force is 2.63 people, and the average dependency ratio is 0.428, indicating that the family burden is generally heavy. In terms of self-organizing ability, the average number of households that can seek help is 8.596, but the standard deviation is 12.36, indicating an uneven distribution of social capital. The proportion of decision-making in public affairs reached 88.5%, while the proportion of joining farmer professional cooperative organizations was only 6.1%. In terms of learning ability, the average length of education for household heads is 6.74 years, and 23.7% of them have mastered professional skills, indicating a relatively low overall level of human capital.

Table 2 focuses on the three sub-dimensions of disaster preparedness: severely inadequate emergency preparedness, with only 15.2% of households having emergency supplies, and the lowest score for item adequacy (mean = 0.130). The insurance participation rate is relatively high, with 62.2% of farmers purchasing agricultural natural disaster insurance. At the level of knowledge preparation, only 31.9% of households actively learn basic disaster prevention knowledge, and only 11.7% of farmers have participated in emergency drills in the village. In physical disaster preparedness, 76.1% of households will place valuable items in a safe location, but the housing reinforcement rate is only 8%, exposing structural risks.

Regarding the control variables (Table 3), the average age of the respondents was 58.5 years, the average education was 6.6 years, and they had lived in the village for more than 50 years, indicating that the sample was mainly composed of “old farmers” who had lived there for a long time. Notably, 93% had flood experience, while their mean expectation of flood occurrence within the next decade scored 3.06, indicating that the sample farmers have a strong perception of future disaster threats. In addition, concrete houses account for 40.9%, reflecting that the disaster resistance ability of the sample farmers’ infrastructure needs to be improved.

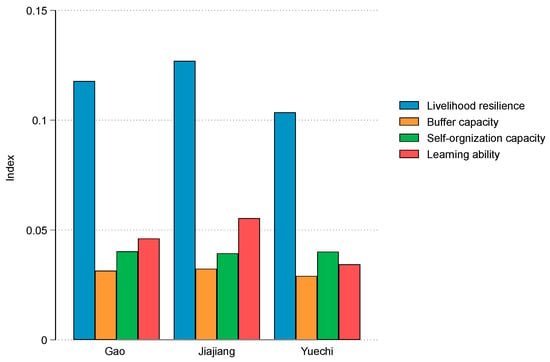

4.2. Livelihood Resilience of Farmers and Sub-Dimension Performance

The values of the farmers’ livelihood resilience index are in the range 0–1. The livelihood resilience index of farmers in the three study areas is in the range of 0–0.15 with a mean of 0.116, which seems quite low. Among them, Jiajiang had the highest livelihood resilience index (0.127), followed by Gao (0.118) and Yuechi (0.104). In addition, the livelihood resilience varied across the study regions. To be more specific, the learning ability index of farmers in the Jiajiang area is the highest (0.065), followed by self-organization capacity (0.040) and buffer capacity (0.031); the performance of farmers in the Gao area is similar to that of Jiajiang; the farmers in Yuechi area had the strongest self-organization capacity (0.040), followed by learning ability (0.034) and buffer capacity (0.029), as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Farmers’ livelihood resilience index and sub-dimension index in different study areas.

4.3. Livelihood Resilience of Farmers with Different Household Characteristics

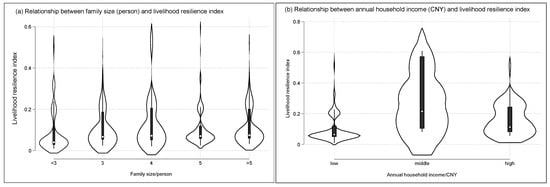

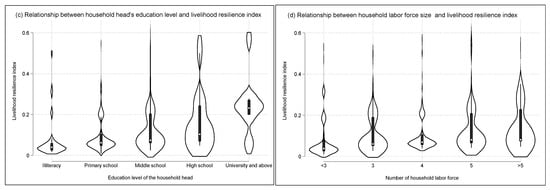

Across all samples, there is some variation in the livelihood resilience of farmers with different household characteristics (Figure 4). Specifically, Figure 4a demonstrates that farmers’ livelihood resilience index exhibits phased changes with increasing family size. When the family size increases from less than three people to four people, the livelihood resilience index shows a significant upward trend. This may be because a family of four usually has between two and three laborers who can participate in agricultural and non-agricultural activities, which is sufficient to cover the needs of agriculture and part-time work, thereby enhancing the risk buffering capacity. However, when the family size exceeds four people, the livelihood resilience index tends to stabilize, which may be due to a decrease in per capita resource ownership, leading to a decrease in marginal benefits. The livelihood resilience of the farmers is significantly and positively correlated with the annual household income (Figure 4b). In Figure 4b, the midpoint of low-income, middle-income, and high-income peasant households is closer to the lower quartile, showing income differences among farmer households within the same income level. The level of education affects the level of livelihood resilience of rural households (Figure 4c). Rural households whose householders are better educated have significantly higher livelihood resilience, and in particular, the livelihood resilience index is highest in households whose head of household has a university level of education or above (0.237), which is 2.96, 2.44, 1.81, and 1.31 times higher than that of households whose head of household is illiterate or has a primary, junior high school, or senior high school level of education, respectively. From the statistical results of the number of household labor force (Figure 4d), when the labor force increases from fewer than three to three, the livelihood resilience index rises from 0.24 to 0.33. This improvement may be attributed to the increased likelihood of non-agricultural employment and income diversification brought by additional labor. However, when the number of laborers exceeds three, the growth of the livelihood resilience index tends to stabilize, which may reflect the limited capacity of local non-agricultural job markets to absorb more labor. This finding also provides important insights for formulating labor transfer policies. Further analysis of Figure 4 reveals that the sample of farmers with different household characteristics exhibits a “gourd-shaped” distribution structure with narrow upper and wide lower parts. Specifically, the livelihood resilience index of the vast majority of rural households is concentrated in the low-value area (wide bottom of the graph), with only a few households reaching a high level (narrow top of the graph). This structure remains consistent across different household characteristic groups, confirming the generally low overall livelihood resilience of farmers in the study area.

Figure 4.

Livelihood resilience index of farmers with different family characteristics.

4.4. Model Results

(1) Regression results

To probe the impact of the livelihood resilience of farmers on disaster preparedness, we used Equation (8), developed earlier. The results of this regression are in Table 4, where Model 1 and Model 2 are used to test the impact of livelihood resilience of farmers on emergency disaster preparedness. Model 1 does not include control variables, and Model 2 adds 11 control variables such as gender, age, and education level based on Model 1. Models 3, 4, 5, and 6 were used to test the impact of farmers’ livelihood resilience on knowledge and skill preparation and physical disaster prevention preparation, respectively. Model 4 and Model 6 are treated similarly to Model 2. The regression results show that except for Model 5, the results of other models are significant at the level of 0.1.

Table 4.

The regression results of the tobit models.

For Model 1, buffer capacity and learning ability are significant except for self-organization capacity; both positively affect farmers’ disaster preparedness. Buffer capacity and learning ability of farmers are significantly positive at the statistical level of 1% and 5%, respectively, which means that improving the buffer capacity and learning ability can help improve the level of farmers’ disaster preparedness. For Model 2, which includes control variables, flood experience and probability of flood disaster are significantly and positively correlated with emergency preparedness. In Model 1, the influence coefficient of self-organization capacity is 0.316, which does not pass the significance test. A possible reason is that the emergency disaster preparedness behavior of farmers is mainly spontaneous within the family and is not related to external factors such as social networks or cooperative organizations. Therefore, although the self-organization capacity may play a certain role in promoting emergency disaster preparedness, it is not significant.

With Model 3, buffer capacity, self-organization capacity, and learning ability positively affect farmers’ knowledge and skill preparation, indicating that when farmers’ buffer capacity, self-organization capacity, and learning ability increase, they can enrich their knowledge and skill preparation. A possible reason is that the better the buffer capacity is of farmers, the more likely they are to take advantage of new opportunities to improve themselves, thereby strengthening their knowledge and skill preparation level. Greater self-organization capacity means that farmers are more connected to the outside world and are likely to have access to more external information about a disaster and be better prepared for disaster prevention. The stronger the learning ability is of farmers, the more likely they are to have knowledge about self-help and mutual aid, further enriching their knowledge and skill preparation. In Model 4, the control variables, age, housing structure, trust level, and flood severity are significantly and positively associated with knowledge of disaster preparedness, although the remaining control variables also positively impact knowledge preparedness for disaster but not significantly.

In Model 5, none of the three dimensions of livelihood resilience of farmers were significant, that is, there was no marked correlation with physical disaster prevention preparation. A possible reason is that in the event of severe floods, the vulnerability of small farmer economies can make it difficult to cope with the threat of more severe floods. In Model 6, which incorporates control variables, trust level, probability of flood disaster, and threat are significantly and positively related to physical disaster prevention preparation, but other control variables are not.

Model 7 shows that buffer capacity, self-organization capacity, and learning ability all have a positive impact on overall disaster preparedness, indicating that the stronger the buffer capacity, self-organization capacity, and learning ability of farmers are, the better their overall disaster preparedness is. In Model 8, after controlling for variables, the three dimensions of livelihood resilience still have a significant positive impact on overall disaster preparedness, while age, trust level, and likelihood of being affected by floods have a positive and significant impact on overall disaster preparedness.

(2) Results and the hypotheses

In summary, buffer capacity has a significant influence on emergency disaster preparedness and knowledge and skill preparation, which is basically in agreement with our Hypothesis 1. Possible reasons for this are as follows: (1) With buffer capacity, represented by natural capital, financial capital, and human capital, the larger the land area that farmers are operating and the more valuable fixed assets they have, the more farmers will “guard” their capital, and the more likely they are to do a good job in daily disaster preparedness. On the other hand, the larger the labor force is in rural households, the greater the possibility is of going out to engage in non-agricultural activities and the likelihood of obtaining the latest relevant disaster prevention knowledge from the outside world. (2) When household income increases, there may be surplus resources to invest in disaster prevention education, thus enhancing knowledge and skill preparation.

Self-organization capacity has a significant effect on knowledge and skill preparation only but does not have a significant impact on emergency disaster preparedness and physical disaster prevention preparation. This is inconsistent with our Hypothesis 2. The possible reasons are as follows: (1) The closer the connection is between farmers and external assistance forces such as relatives, friends, and village collectives, the more likely they are to reduce information barriers and receive up-to-date disaster information from the outside, so the more fully prepared they are in terms of knowledge and skill preparation. (2) Emergency disaster preparedness and physical disaster prevention preparation are essentially behavioral choices of individual farmers. In other words, individual actions depend on their own subjective choices. Self-organization capacity, represented by the closeness of relatives and friends and the participation in village collective behavior, is only one of the external influencing factors and cannot determine the behavior of farmers, thus leading to the insignificant correlation between the self-organization capacity of farmers and disaster preparedness and the other two dimensions (emergency disaster preparedness and physical disaster prevention preparation).

Learning ability has a positive and significant effect on emergency disaster preparedness and knowledge and skill preparedness, which is basically in agreement with Hypothesis 3. Possible reasons are as follows: (1) The stronger the learning ability and the greater the literacy are of farmers, the more likely they are to be proactive in gaining knowledge about disaster preparedness, which, in turn, improves their daily disaster preparedness, disaster knowledge learning ability, and disaster mutual rescue ability. A concrete manifestation of this is that farmers keep emergency supplies at home, consciously purchasing agricultural insurance, updating disaster knowledge, and so on. (2) Learning ability has no significant effect on physical disaster prevention preparation. On the one hand, experience with house reinforcement is related to whether the household has previously experienced a risky disaster, such as a flood, and is not related to personal learning ability (farmers who have experienced such disasters usually choose to strengthen the building to cope with the disaster impact). On the other hand, whether to properly store valuable and hazardous items is a personal behavior for which the strength of individual learning ability cannot play a role, with the result that the correlation between farmers’ learning ability and physical disaster prevention preparation is not significant.

5. Discussion

Livelihood resilience is a key strategy for achieving sustainable agricultural and rural development, while also providing solutions for local farmers to effectively cope with risks of disasters such as floods [,]. We have assessed three major aspects of farmers’ livelihood resilience characteristics in the study area: buffer capacity, self-organization capacity, and learning ability, as well as selected indicators (emergency disaster preparedness, knowledge and skill preparation, and physical disaster prevention preparation) from these three dimensions to evaluate the disaster preparedness. A tobit model was constructed to analyze the impact of farmers’ livelihood resilience on disaster preparedness.

Our results indicate that households with high buffer capacity will be more likely to be prepared for disasters. The reason for this is that when faced with the threat of floods, these farmers have more human and social capital and are more likely to utilize these resources to alleviate the negative impacts of floods. This is consistent with the study by [,,,], who also reported similar results. However, this study further suggests that there may be a critical point in the “livelihood capital synergy effect” [], where the marginal benefits decrease after exceeding the threshold (Figure 4a), providing a quantitative basis for precise interventions to enhance farmers’ livelihood resilience. The greater the learning ability of farmers is, the greater the ability is to be prepared for and withstand natural disasters, which is consistent with the studies of [,]. For farmers in flood risk areas, enhancing their livelihood resilience, and thereby improving risk aversion, has become an effective means of mitigating losses from natural disasters such as floods. Further, the self-organization capacity of farmers has a positive effect on knowledge and skills to prepare for disasters. The reason is that good social networks and abundant social capital can provide both emotional and material support for farmers. In social networks, information is exchanged, and disaster preparedness is improved, which is partially consistent with the findings of [,]. All of these clearly demonstrate that the impact of natural disasters on families depends on their resilience []. In this regard, farmers should maximize their opportunities to actively learn and master knowledge about flood prevention and disaster responses.

Farmers, as direct victims of climate disturbance, can take advantage of various internal and external conditions to cope with the impact of natural disasters []. We found that the household’s internal characteristics, such as the number of labor force and the education level of the household head, as well as external factors such as the convenience of transportation and social support, all affect the livelihood resilience of farmers to varying degrees. This is in accord with the research of [,]. The former points out that the larger the labor force is and the better the health status is of members in rural households, the smaller the financial burden and thus the greater the livelihood resilience. The latter found that farmers with a more stable network of relationships will be better able to mitigate the negative impacts of disasters. Ref. [] also found that the distance from a market determines whether farmers can easily obtain information, which plays an indirect role in the strength of their livelihood resilience. It should also be noted that farmers’ response to climate shocks is not a simple linear process of “capacity outcome”. As discussed in Figure 4d, the advantage of improving livelihood resilience brought about by the increase in labor force is actually offset by market capacity bottlenecks, leading to marginal labor outflow and weakening the disaster response capacity of households. Therefore, this study suggests that government departments should take account of local resource endowments and take advantage of the high self-organization and strong connectivity of farmers in the research area and improve the bottleneck of local labor redundancy.

6. Conclusions

This article constructs a theoretical framework to explore the contributors of farmers’ livelihood resilience and disaster preparedness by focusing on three dimensions: buffer capacity, self-organization capacity, and learning ability. Results show that self-organization capacity of farmers is the strongest among the three capacities in the study area, followed by learning ability, while buffer capacity is the weakest, a ranking corroborated by entropy-weight calculations. Farmers’ overall disaster preparedness behavior averages only 0.393, with the adequacy of emergency supplies being particularly low; most households lack basic preparedness items, highlighting an urgent need for improvement.

Regression analyses reveal that the level of trust that farmers have in society and the possibility of being exposed to flood risk will significantly shape disaster preparedness. On the one hand, increasing their trust in society will make them more willing to respond to the call for disaster prevention before natural disasters such as floods occur. Belief that government departments and relevant organizations in society lend a helping hand to farmers hit by floods will also positively build up their confidence in post-disaster recovery. On the other hand, when farmers perceive the possibility of flooding or perceive a high impact caused by flooding, they are more inclined to incorporate disaster avoidance measures into their daily lives. Importantly, livelihood resilience correlates strongly with disaster preparedness, where buffer capacity most influences emergency disaster preparedness, self-organization capacity drives knowledge and skill preparation, and both self-organization capacity and learning ability collectively enhance overall disaster preparedness.

This article has the following limitations. First, we use cross-sectional data, but when collecting information, the research objects of our research, farmers, may have a tendency to avoid certain sensitive issues such as income and property. If qualitative research can be supplemented to dig out hidden deep information, the gap in this article will be better filled. Second, due to resource constraints, our study was restricted to the three selected flood-prone areas of Gaox, Jiajiang, and Yuechi counties in Sichuan Province, which, to some extent, reduces its representativeness. It is necessary to expand the research scope of flood-prone areas for a more representative study in the future. In addition, this study did not differentiate whether farmers planting different crops would be affected to varying degrees by floods. It is necessary to conduct comparative studies on different crops in the future to reveal the potential role of crop types. Third, this study only focuses on the correlation between farmers’ livelihood resilience and disaster preparedness but does not address their risk perception before disasters occurred. Whether risk perception of farmers plays a mediating role between livelihood resilience and disaster preparedness still needs further research in the future.

Although the representativeness of the region studied in this article is limited, our research results are still relevant for other regions or countries that aim to improve the livelihood resilience of farmers and mitigate the negative impacts of natural disasters of all types. Resource conditions vary from region to region, and there are differences in the resilience potential of local farmers for their livelihoods [,]. Thus, each region needs to tailor its policies to suit the practical needs and circumstances of its community.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, W.L.; methodology, Y.N.; validation, W.L. and Y.N.; formal analysis, Y.N.; investigation, D.X.; resources, W.L. and D.X.; data curation, D.X.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.N.; writing—review and editing, M.F.; visualization, Y.N.; supervision, D.X.; funding acquisition, W.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Nos. 723B2019 and 72474173), the Ministry of Education Humanities and Social Science Research Youth Fund Project (No. 22XJC630007), the Natural Science Foundation of Shaanxi Province (No. 2024JC-YBQN-0758), the Social Science Foundation of Shaanxi Province (Grant No. 2023R290), and the Morrison Institute for Population and Resource Studies at Stanford University.

Data Availability Statement

Data have not been deposited into a publicly available repository associated with my study and are available on request due to privacy/ethical restrictions.

Acknowledgments

The authors appreciate the support of the local government and the patient cooperation of the interviewees during the data collection.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Xu, X.; Tang, Q. Spatiotemporal variations in damages to cropland from agrometeorological disasters in mainland China during 1978–2018. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 785, 147247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X.; Zhang, H.; Chen, W.; Huang, G. Urbanization and climate change impact on future flood risk in the Pearl River Delta under shared socioeconomic pathways. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 762, 143144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- China News Service. Ministry of Emergency Management: Natural Disasters Affected 112 Million People in 2022 [EB/OL]. (2023-01-14). Available online: http://www.cneb.gov.cn/yjxw/gnxw/20230114/t20230114_526125085.html#:~:text= (accessed on 13 August 2025).

- Sichuan Provincial Emergency Management Department. The Emergency Management Department of Sichuan Province Releases the Basic Situation of Natural Disasters in the Province in 2022 [EB/OL]. (2023-02-07). Available online: https://yjt.sc.gov.cn/scyjt/juecegongkai/2023/2/7/3b72e16f55a040a48dd32c9fc30957f1.shtml#:~:text= (accessed on 13 August 2025).

- Kumara, K.; Pal, S.; Chand, P.; Kandpal, A. Carbon sequestration potential of sustainable agricultural practices to mitigate climate change in Indian agriculture: A meta-analysis. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2023, 35, 697–708. [Google Scholar]

- Das, U.; Ansari, M.A. The nexus of climate change, sustainable agriculture, and farm livelihood: Contextualizing climate smart agriculture. Clim. Res. 2021, 84, 23–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Y.; Zhu, F.; Qiu, X.; Zhao, S. Effects of natural disasters on livelihood resilience of rural residents in Sichuan. Habitat Int. 2018, 76, 19–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chambers, R.; Conway, G. Sustainable Rural Livelihoods: Practical Concepts for the 21st Century; Institute of Development Studies (UK): Brighton, UK, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- IPCC. Climate Change 2014: Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerability. Part A: Global and Sectoral Aspects. Contribution of Working Group I to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Yiran, G.A.B.; Atubiga, J.A.; Kusimi, J.M.; Kwang, C.; Owusu, A.B. Adaptation to perennial flooding and food insecurity in the Sudan savannah agroecological zone of Ghana. Environ. Res. 2022, 214, 114037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Núñez, A.P.B.; Gutiérrez-Montes, I.; Hernández-Núñez, H.E.; Suárez, D.R.G.; García, G.A.G.; Suárez, J.C.; Casanove, F.; Flora, C.; Sibelet, N. Diverse farmer livelihoods increase resilience to climate variability in southern Colombia. Land Use Policy 2023, 131, 106731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awazi, N.P.; Quandt, A. Livelihood resilience to environmental changes in areas of Kenya and Cameroon: A comparative analysis. Clim. Change 2021, 165, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macusi, E.D.; Diampon, D.O.; Macusi, E.S. Understanding vulnerability and building resilience in small-scale fisheries: The case of Davao Gulf, Philippines. Clim. Policy 2023, 25, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanner, T.; Lewis, D.; Wrathall, D.; Bronen, R.; Cradock-Henry, N.; Huq, S.; Lawless, C.; Nawrotzki, R.; Prasad, V.; Rahman, M.A.; et al. Livelihood resilience in the face of climate change. Nat. Clim. Change 2015, 5, 23–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.; Guo, S.; Deng, X.; Xu, D. Livelihood resilience and strategies of rural residents of earthquake-threatened areas in Sichuan Province, China. Nat. Hazards 2021, 106, 255–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Dong, S.; Lin, H.; Li, F.; Cheng, H.; Jin, Z.; Wang, S.; Zhang, H.; Hou, P.; Xia, P. Vulnerability of farmers and herdsmen households in Inner Mongolian plateau to arid climate disasters and their development model. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 402, 136853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Yang, Z.; Xu, X.; Wu, S.; Wang, Y. Assessment and influencing factors of urban residents’ flood emergency preparedness capacity: An example from Jiaozuo City, China. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2024, 102, 104294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cong, Z.; Feng, G.; Chen, Z. Disaster exposure and patterns of disaster preparedness: A multilevel social vulnerability and engagement perspective. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 339, 117798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tierney, K.J.; Lindell, M.K.; Perry, R.W. Facing the unexpected: Disaster preparedness and response in the United States. Disaster Prev. Manag. Int. J. 2002, 11, 222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronan, K.R.; Alisic, E.; Towers, B.; Johnson, V.A.; Johnston, D. Disaster preparedness for children and families: A critical review. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 2015, 17, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toland, J.C.; Wein, A.M.; Wu, A.M.; Spearing, L.A. A conceptual framework for estimation of initial emergency food and water resource requirements in disasters. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2023, 90, 103661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obi, R.; Nwachukwu, M.U.; Okeke, D.C.; Jiburum, U. Indigenous flood control and management knowledge and flood disaster risk reduction in Nigeria’s coastal communities: An empirical analysis. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2021, 55, 102079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Zhang, F.; Liu, S.; Xu, D. Consistency between the subjective and objective flood risk and willingness to purchase natural disaster insurance among farmers: Evidence from rural areas in Southwest China. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2023, 102, 107201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLennan, J.; Marques, M.D.; Every, D. Conceptualising and measuring psychological preparedness for disaster: The Psychological Preparedness for Disaster Threat Scale. Nat. Hazards 2020, 101, 297–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Yang, X.; Deng, X.; Xu, D. Does disaster knowledge affect residents’ choice of disaster avoidance behavior in different time periods? Evidence from China’s earthquake-hit areas. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2022, 67, 102690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuang, F.; Jin, J.; He, R.; Ning, J.; Wan, X. Farmers’ livelihood risks, livelihood assets and adaptation strategies in Rugao City, China. J. Environ. Manag. 2020, 264, 110463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, D.; He, M.; Kong, F. Risk attitude, risk perception, and farmers’ pesticide application behavior in China: A moderation and mediation model. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 276, 124241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sertse, S.F.; Khan, N.A.; Shah, A.A.; Liu, Y.; Naqvi, S.A.A. Farm households’ perceptions and adaptation strategies to climate change risks and their determinants: Evidence from Raya Azebo district, Ethiopia. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2021, 60, 102255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, A.; Wei, Y.; Zhong, F.; Wang, P. How do climate change perception and value cognition affect farmers’ sustainable livelihood capacity? An analysis based on an improved DFID sustainable livelihood framework. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2022, 33, 636–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, Z.; Guha, G.S.; Shew, A.M.; Alam, G.M. Climate change risk perceptions and agricultural adaptation strategies in vulnerable riverine char islands of Bangladesh. Land Use Policy 2021, 103, 105295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, G.; Qureshi, J.A.; Khan, A.; Shah, A.; Ali, S.; Bano, I.; Alam, M. The role of sense of place, risk perception, and level of disaster preparedness in disaster vulnerable mountainous areas of Gilgit-Baltistan, Pakistan. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2020, 27, 44342–44354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.S.; Zulfiqar, F.; Ullah, H.; Himanshu, S.K.; Datta, A. Farmers’ perceptions, determinants of adoption, and impact on food security: Case of climate change adaptation measures in coastal Bangladesh. Clim. Policy 2023, 23, 1257–1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollnagel, E. Resilience engineering and the built environment. Build. Res. Inf. 2014, 42, 221–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holling, C.S. Resilience and stability of ecological systems. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 1973, 4, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Li, J.; Xu, J. Effects of disaster-related resettlement on the livelihood resilience of rural households in China. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2020, 49, 101649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Speranza, C.I.; Wiesmann, U.; Rist, S. An indicator framework for assessing livelihood resilience in the context of social–ecological dynamics. Glob. Environ. Change 2014, 28, 109–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Li, J.; Ren, L.; Xu, J.; Li, C.; Li, S. Exploring livelihood resilience and its impact on livelihood strategy in rural China. Soc. Indic. Res. 2020, 150, 977–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lecegui, A.; Olaizola, A.M.; López-i-Gelats, F.; Varela, E. Implementing the livelihood resilience framework: An indicator-based model for assessing mountain pastoral farming systems. Agric. Syst. 2022, 199, 103405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ifejika Speranza, C. Buffer capacity: Capturing a dimension of resilience to climate change in African smallholder agriculture. Reg. Environ. Change 2013, 13, 521–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DFID. Sustainable Livelihoods Guidance Sheets; Department for International Development (UK): London, UK, 1999.

- Zhou, W.; Ma, Z.; Guo, S.; Deng, X.; Xu, D. Livelihood capital, evacuation and relocation willingness of residents in earthquake-stricken areas of rural China. Saf. Sci. 2021, 141, 105350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandilya, J.; Goswami, K. Effect of different forms of capital on the adoption of multiple climate-smart agriculture strategies by smallholder farmers in Assam, India. Mitig. Adapt. Strateg. Glob. Change 2024, 29, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Jin, J.; Zhang, C.; Qiu, X.; Liu, D. How do livelihood capital affect farmers’ energy-saving behaviors: Evidence from China. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 414, 137769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Huo, X.; Peng, C.; Qiu, H.; Shangguan, Z.; Chang, C.; Huai, J. Complementary livelihood capital as a means to enhance adaptive capacity: A case of the Loess Plateau, China. Glob. Environ. Change 2017, 47, 143–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Y.; Shi, X.; Li, X.; Feng, X. Livelihood resilience of vulnerable groups in the face of climate change: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Environ. Dev. 2022, 44, 100777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreft, C.; Angst, M.; Huber, R.; Finger, R. Farmers’ social networks and regional spillover effects in agricultural climate change mitigation. Clim. Change 2023, 176, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skaalsveen, K.; Ingram, J.; Urquhart, J. The role of farmers’ social networks in the implementation of no-till farming practices. Agric. Syst. 2020, 181, 102824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Qiu, T. The effects of farmer cooperatives on agricultural carbon emissions reduction: Evidence from rural China. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 450, 141881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Cai, S.; Singh, R.K.; Cui, L.; Fava, F.; Tang, L.; Xu, Z.; Li, C.; Cui, X.; Du, J.; et al. Livelihood resilience in pastoral communities: Methodological and field insights from Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 838, 155960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, L.; He, J.; Deng, X.; Xu, D. The influence of professionals on the general public in the choice of earthquake disaster preparedness: Based on the perspective of peer effects. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2021, 66, 102593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, S.; Enelamah, N.V. Social protection and absorptive capacity: Disaster preparedness and social welfare policy in the United States. World Dev. 2024, 173, 106443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zhong, B.; Chen, J.; Li, J.; Wang, H. Investigation of 2020−2022 Extreme Floods and Droughts in Sichuan Province of China Based on Joint Inversion of GNSS and GRACE/GFO Data. J. Hydrol. 2024, 632, 130868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sichuan Provincial Bureau of Statistics. Statistical Bulletin on National Economic and Social Development of Sichuan Province in 2022 [EB/OL]. (2023-03-22). Available online: https://tjj.sc.gov.cn/scstjj/c112126/2023/3/22/46b62db1f5d14461905178e3f990b627.shtml (accessed on 13 August 2025).

- Quandt, A. Measuring livelihood resilience: The household livelihood resilience approach (HLRA). World Dev. 2018, 107, 253–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amore, M.D.; Murtinu, S. Tobit models in strategy research: Critical issues and applications. Glob. Strategy J. 2021, 11, 331–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, D.; He, J.; Qing, C.; Zhang, F. Impact of perceived environmental regulation on rural residents’ willingness to pay for domestic waste management. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 412, 137390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mabuku, M.P.; Senzanje, A.; Mudhara, M.; Jewitt, G.; Mulwafu, W. Rural households’ flood preparedness and social determinants in Mwandi district of Zambia and Eastern Zambezi Region of Namibia. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2018, 28, 284–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, A.U.; Balakrishnan, U.V.; Jha, P.S. A study of multicollinearity detection and rectification under missing values. Turk. J. Comput. Math. Educ. 2021, 12, 399–418. [Google Scholar]

- Qin, Y.; Shi, X.; Li, X.; Yan, J. Geographical indication agricultural products, livelihood capital, and resilience to meteorological disasters: Evidence from kiwifruit farmers in China. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 65832–65847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waseem, H.B.; Mirza, M.N.E.E.; Rana, I.A. Exploring the role of social capital in flood risk reduction: Insights from a systematic review. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2024, 105, 107390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dapilah, F.; Nielsen, J.Ø.; Friis, C. The role of social networks in building adaptive capacity and resilience to climate change: A case study from northern Ghana. Clim. Dev. 2020, 12, 42–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rustinsyah, R.; Prasetyo, R.A.; Adib, M. Social capital for flood disaster management: Case study of flooding in a village of Bengawan Solo Riverbank, Tuban, East Java Province. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2021, 52, 101963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kakehazar, R.; Agahi, H.; Geravandi, S. Livelihood resilience to climate change in family farming system (case study: Wheat farmers’ Mahidasht in Kermanshah). Int. J. Agric. Manag. Dev. 2020, 10, 415–433. [Google Scholar]

- Losee, J.E.; Webster, G.D.; McCarty, C. Social network connections and increased preparation intentions for a disaster. J. Environ. Psychol. 2022, 79, 101726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galarza-Villamar, J.A.; Leeuwis, C.; Cecchi, F. Rice farmers and floods in Ecuador: The strategic role of social capital in disaster risk reduction and livelihood resilience. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2024, 104, 104332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arouri, M.; Nguyen, C.; Youssef, A.B. Natural disasters, household welfare, and resilience: Evidence from rural Vietnam. World Dev. 2015, 70, 59–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorward, P.; Clarkson, G.; Poskitt, S.; Stern, R. Putting the farmer at the center of climate services. One Earth 2021, 4, 1059–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, L.; Xu, Y.; Wang, W.; Wang, Y. Impact of livelihood capital and rural site conditions on livelihood resilience of farm households: Evidence from contiguous poverty–stricken areas in China. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 123808–123826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, X.; Chen, H.; Zhao, H.; Xue, B. Farmer households’ livelihood resilience in ecological-function areas: Case of the Yellow River water source area of China. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2022, 24, 9665–9686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngoma, H.; Finn, A.; Kabisa, M. Climate shocks, vulnerability, resilience and livelihoods in rural Zambia. Clim. Dev. 2023, 16, 490–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).