Abstract

High-resolution air-temperature fields are essential for climate, hydrologic, and ecological applications in complex terrain, yet operational products often lack the spatial detail to resolve topographic effects. We develop an observation-driven reconstruction of daily air temperature fields for South Korea (2024) using ordinary kriging with lapse-rate correction (OKLR), integrating a dense network of over 500 stations from the Automatic Mountain Meteorology Observation System (AMOS) and the Automated Surface Observing System (ASOS). The OKLR framework systematically removes elevation-driven trends using a physically based fixed lapse rate (–6.5 °C km−1), performs kriging on detrended residuals, and reapplies Digital Elevation Model (DEM)-based corrections to generate high-fidelity daily fields at a 270 m grid spacing. Unlike numerical weather prediction (NWP) models that simulate atmospheric processes, this approach reconstructs spatially continuous fields directly from dense in situ observations, ensuring empirical grounding. Extensive daily spatial cross-validation (n = 37,813) demonstrates that OKLR (MAE = 0.656 °C) significantly outperforms elevation-unadjusted ordinary kriging by ≈37% and the operational 1.5 km LDAPS product (MAE = 0.895 °C) by 27%. This performance gain is particularly pronounced in high-elevation zones (>700 m) and natural surfaces (≈73% of the study area), where topographic complexity is greatest. The final observation-constrained reconstruction attains a robust MAE of 0.462 °C with near-zero bias over 188,318 station–days. As the first nationwide daily temperature dataset for South Korea at 270 m resolution, this study provides a critical foundation for precision agriculture, ecosystem monitoring, and climate change adaptation in topographically diverse environments.

1. Introduction

As climate change and extreme weather events intensify, high-quality and high-resolution temperature grids are increasingly needed across all fields of global environmental research [1,2]. In Korea, high-resolution temperature grids that reflect fine-scale topographic effects are even more critical for local-scale modeling in agriculture, forestry, meteorology, and hydrology. However, topographic complexity creates substantial temperature variability at local scales (<1 km) through processes such as elevation lapse rates, cold-air drainage, and terrain sheltering—patterns that traditional sparse station networks and coarse operational products (>1 km) fail to resolve [3,4]. Accordingly, in South Korea, gridded air temperature fields are typically derived from station-based statistical interpolation—including geographic information system (GIS)- and Parameter–Elevation Regressions on Independent Slopes Model (PRISM)-based frameworks such as K-PRISM—regression-based models, and operational or global reanalysis datasets such as the Data Assimilation and Prediction System (LDAPS) and ECMWF Reanalysis 5 (ERA5).

More generally, gridded temperature data are primarily produced through three approaches: (1) interpolation of point observations, (2) linear and nonlinear regression using auxiliary variables, and (3) numerical weather prediction (NWP) models. Although spatial interpolation techniques for point data are computationally efficient, they possess inherent methodological limitations. Traditional geometric approaches, such as inverse distance weighting (IDW) and spline functions, offer high computational efficiency but fail to account for the spatial correlation structures inherent in climate data [5,6]. Consequently, these methods typically yield temperature errors ranging from 1.3 to 1.5 °C in complex mountainous terrain. To overcome this, the more sophisticated geostatistical technique of ordinary kriging (OK) provides a more robust framework by leveraging the spatial autocorrelation structure of observations and yielding uncertainty estimates via prediction variance [7,8]. However, this method assumes stationarity in two-dimensional space—that is, a constant local mean—which can introduce systematic errors where elevation varies substantially [9].

Second, linear regression-based methods, such as multiple linear regression (MLR) and geographically weighted regression (GWR), explicitly incorporate environmental covariates but rely on predetermined functional forms and struggle to capture nonlinear relationships between temperature and auxiliary variables [10,11]. Recent advances in machine learning (ML) have demonstrated superior predictive performance by capturing complex nonlinear relationships between temperature and various environmental predictors, with reported RMSEs of 0.4–0.85 °C [12,13,14]. However, these data-driven “black-box” approaches require extensive training data and lack physical interpretability, limiting our ability to understand and trust the underlying climate processes [15].

Third, NWP-based temperature grids—such as global reanalysis products like ERA5, which provide hourly data at approximately 31 km spatial resolution—offer physically consistent datasets. Still, their coarse grids cannot resolve sub-kilometer topographic influences on temperature [16]. While climatology products such as WorldClim (approximately 1 km monthly resolution) offer finer spatial resolution, they provide only long-term averages and thus fail to capture daily variability [17]. Additionally, operational numerical weather prediction models such as the Korea Meteorological Administration’s Local LDAPS provide 3-hourly gridded forecasts at 1.5 km resolution. While LDAPS performs reasonably well in flat terrain (with a bias of approximately 0.1 °C), its errors increase substantially in mountainous regions (−0.6 to 1.6 °C), where terrain smoothing and coarse spatial resolution fail to resolve steep topographic gradients [18].

To address these challenges, the Korea Meteorological Administration (KMA) and the Korea Forest Service (KFS) operate a combined network of more than 500 Automated Surface Observing System (ASOS) and Automatic Mountain Meteorology Observation System (AMOS) stations. Together, these systems provide dense and complementary point observations across both the lowland and mountainous regions of South Korea. However, a nationwide, daily gridded temperature product that fully integrates these synergistic networks while remaining suitable for high-resolution operational climate services has yet to be established.

In this study, we develop an observation-based framework utilizing ordinary kriging with lapse-rate correction (OKLR) to generate high-resolution daily temperature fields across South Korea. The proposed framework explicitly decouples vertical (elevation-driven) and horizontal temperature variability, thereby preserving physically interpretable topographic gradients while maintaining computational efficiency and reproducibility for routine national-scale implementation. Unlike model-based products, our approach directly constrains gridded temperatures using dense ground observations, ensuring the retention of fine-scale terrain-driven temperature variations in complex topography.

The novelty of this study is characterized by three key aspects. First, we present a nationwide daily temperature dataset that integrates a dense mountain observation network, significantly strengthening observational constraints in high-elevation terrain where uncertainties are typically high. Second, we demonstrate the added value of lapse-rate correction and network integration through rigorous daily spatial cross-validation and a comparative analysis with elevation-unadjusted geostatistical interpolation and operational numerical weather prediction products. Third, we establish an operationally feasible OKLR framework that relies solely on routinely available station observations and a DEM, enabling automated nationwide production without the need for data-intensive auxiliary predictors or computationally expensive numerical modeling. Collectively, these contributions position this study as a benchmark case for observation-constrained, physically interpretable temperature gridding in complex terrain. Throughout this paper, “temperature” refers to daily mean air temperature unless otherwise specified. The remainder of this paper is organized as follows: Section 2 describes the study area and observational data. Section 3 details the quality-control procedures, OKLR methodology, and validation approach. Section 4 presents the performance evaluation, final dataset characteristics, and error diagnostics. Section 5 summarizes key conclusions and implications.

2. Study Area and Data

2.1. Study Area

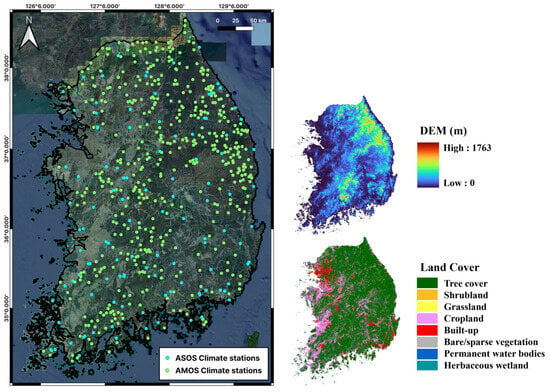

South Korea was selected as the study area to evaluate elevation-adjusted temperature interpolation methods, owing to its topographically complex terrain (Figure 1). The terrain is predominantly mountainous with steep elevation gradients, resulting in substantial spatial heterogeneity and pronounced topographic influences on local climate patterns [19]. It also experiences a monsoon climate with four distinct seasons: spring (March–May), summer (June–August), fall (September–November), and winter (December–February). The combination of rugged terrain and distinct seasonal changes in atmospheric conditions results in substantial spatiotemporal temperature variability, making it an ideal testbed for evaluating interpolation methods that account for topographic and seasonal effects.

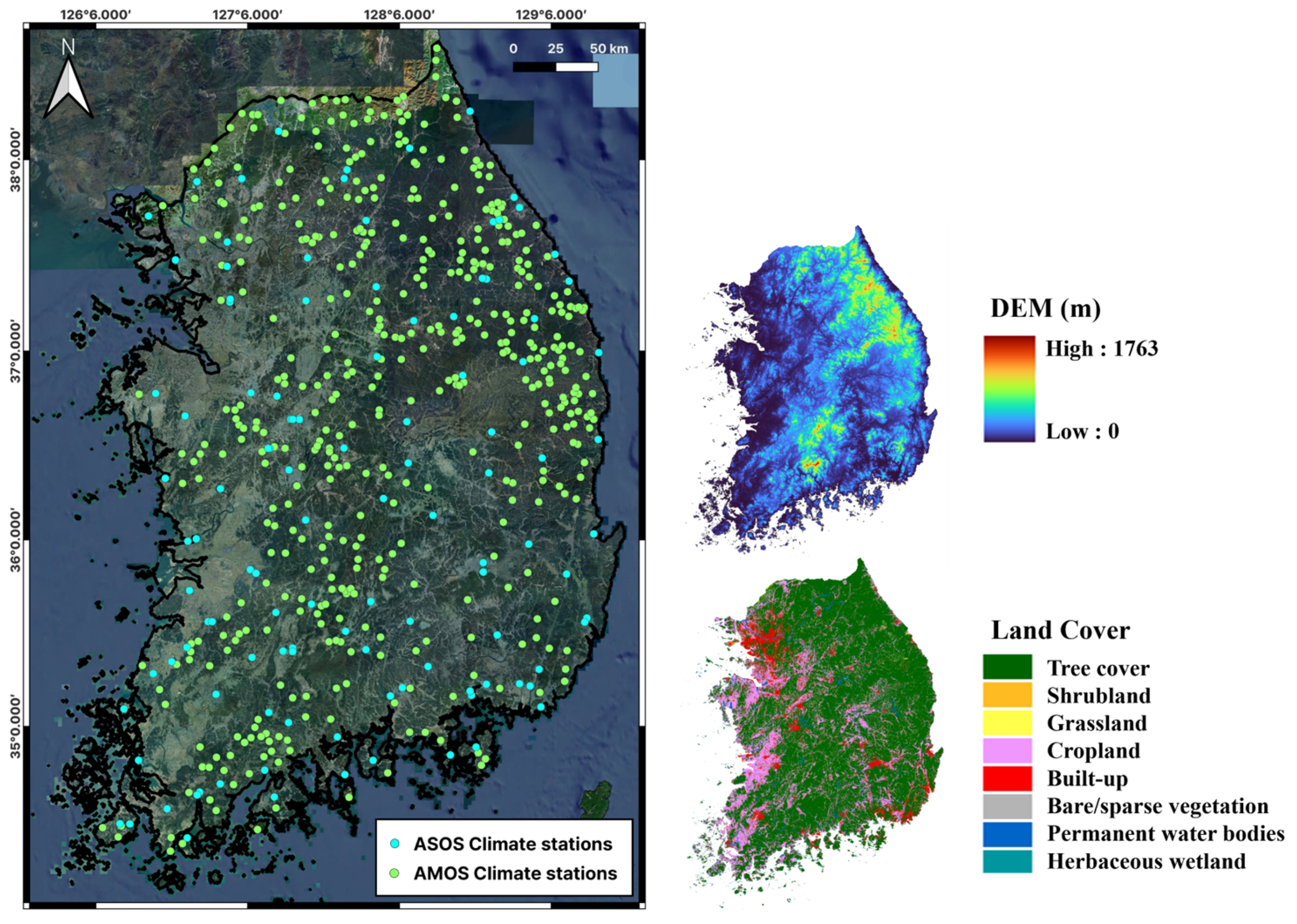

Figure 1.

Spatial distribution of the climate observation network and geographical characteristics of the study area, mainland South Korea. The main map displays the locations of the 90 Automated Surface Observing System (ASOS; light blue dots) and 474 Automatic Mountain Meteorology Observation System (AMOS; light green dots) stations. The inset panels on the right show the region’s topography, derived from the Shuttle Radar Topography Mission (SRTM) Digital Elevation Model (DEM), with elevations ranging from 0 to 1763 m (top) and an 8-category land-cover classification based on the ESA WorldCover dataset (bottom).

Furthermore, a dense observational network comprising hundreds of ASOS and AMOS stations distributed nationwide provides high-quality temperature data. This extensive dataset is well-suited for validating the performance and robustness of the proposed lapse-rate-based interpolation framework. To minimize spatial interpolation uncertainty over large water bodies and isolated regions, Jeju Island was excluded from the analysis. This exclusion is due to its strong maritime influence and the limited spatial connectivity of its station network to the mainland, which could compromise interpolation accuracy.

2.2. Data

2.2.1. In Situ Air Temperature Data

The temperature dataset consists of observations from two in situ networks: the Automated Surface Observing System (ASOS) operated by the Korea Meteorological Administration (KMA) and the Automatic Mountain Meteorology Observation System (AMOS) operated by the Korea Forest Service (KFS). The ASOS network comprises 98 stations distributed throughout South Korea at approximately 13 km intervals, with most stations located near residential areas at elevations below 300 m [20,21]. The KMA processes raw observations collected at 1 min intervals to provide quality-controlled daily statistics.

Although ASOS stations provide nationwide coverage, their spatial distribution is biased toward low elevations and residential areas, which may limit their ability to represent temperature variability across steep elevation gradients. To enhance spatial representativeness in complex terrain, we incorporated additional observations from the AMOS network. Operated by the KFS since 2012, AMOS monitors meteorological conditions specifically in mountainous regions [22]. These stations are preferentially located at higher elevations (typically > 200 m), offering spatial complementarity to the ASOS network [23].

For this analysis, 2024 daily mean air temperature data were obtained via public Application Programming Interfaces (APIs) from 90 ASOS stations (KMA) and 474 AMOS stations (KFS) within the study area. These data were accessed on 12 January 2025 and 5 January 2025, respectively. Temperature sensors are installed at 1.5 m (ASOS) and 2.0 m (AMOS) above ground level. The potential impact of this 0.5 m height difference on daily mean temperatures and inter-network consistency is further examined in Appendix A.

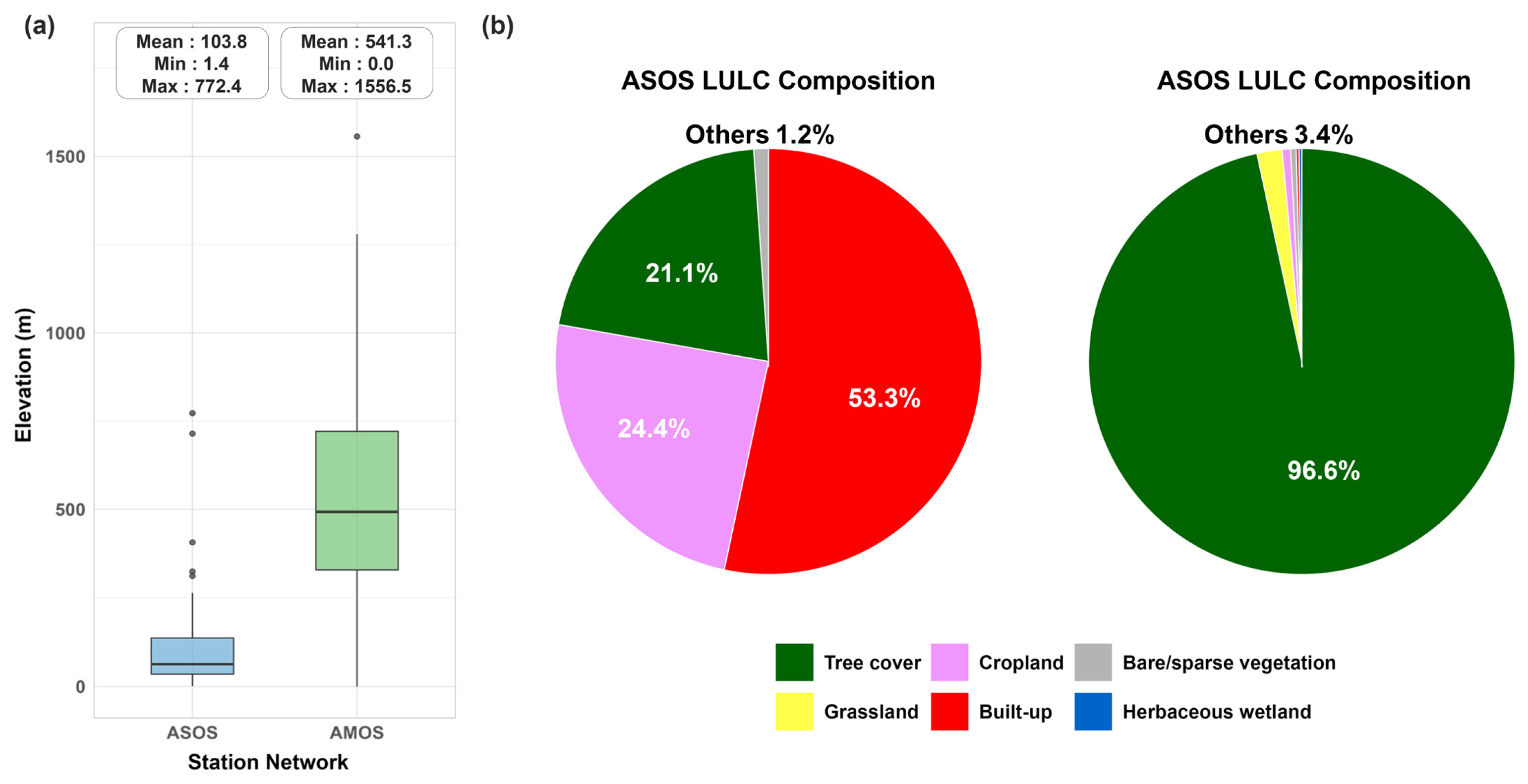

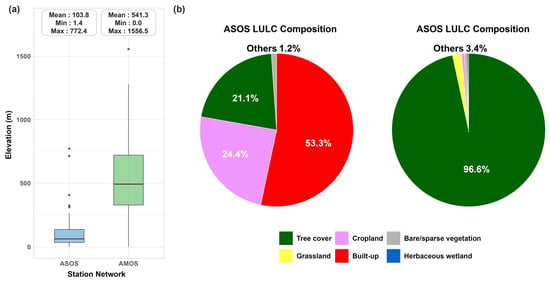

The two observation networks exhibit complementary characteristics in elevation and land cover (Figure 2a,b). ASOS stations are distributed at lower elevations (mean: 103.8 m, range: 1.4–772.4 m) and encompass diverse land-cover types, including built-up areas (53.3%), cropland (24.4%), tree cover (21.1%), and bare or sparsely vegetated surfaces (1.1%). In contrast, AMOS stations cover higher elevations (mean: 541.3 m, range: 0–1556.5 m) and are predominantly located in forested areas (96.6%), with minor contributions from grassland (1.9%), cropland (0.6%), and other land-cover classes (<0.5% each), reflecting their primary role in monitoring mountain meteorological conditions. Given that the height difference between the two networks is minimal, it is unlikely to significantly affect daily mean temperature estimates. Consequently, no adjustments were applied.

Figure 2.

Station characteristics of ASOS and AMOS networks. (a) Elevation distribution showing ASOS stations at lower elevations and AMOS stations at higher elevations. The points represent individual observations that fall beyond the boxplot whiskers. (b) Land-use and land-cover (LULC) composition. Land-cover classifications were derived from the ESA WorldCover 10 m dataset and resampled to 270 m using majority rule. Categories representing less than 2% are not labeled in the pie chart.

2.2.2. Digital Elevation Model (DEM)

Elevation is the most critical topographic variable in temperature interpolation, as it determines spatial temperature patterns through atmospheric lapse rates [24]. This study utilized the Shuttle Radar Topography Mission (SRTM) DEM v4.1, initially at 90 m spatial resolution and resampled to 270 m to match the target grid (https://srtm.csi.cgiar.org/, accessed on 30 November 2024). The DEM is used to account for elevation effects on temperature via lapse-rate corrections during interpolation.

3. Methods

3.1. Overview

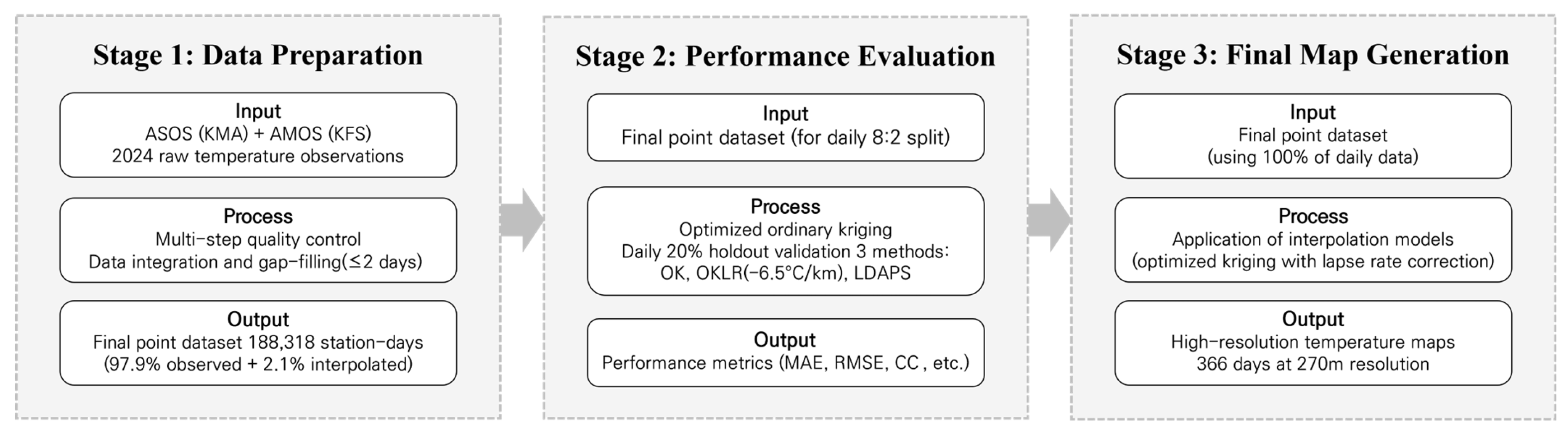

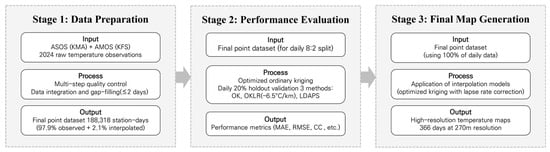

We employed a three-stage approach to generate high-resolution daily temperature maps for South Korea for the entire year of 2024 (1 January–31 December; 366 days) (Figure 3). First, we processed and quality-controlled temperature observations from two complementary networks: ASOS (90 stations) and AMOS (up to 474 stations). Multi-step quality control (QC) procedures and gap-filling (≤2 days) yielded a final point dataset of 188,318 station–days (Section 3.2).

Figure 3.

Schematic diagram of the overall research framework showing the three-stage workflow: (1) data preparation with quality control and gap-filling to produce 188,318 station days, (2) performance evaluation via daily 20% spatial holdout cross-validation of three interpolation models (OK, OKLR, and LDAPS), and (3) final generation of 366 daily temperature maps at 270 m resolution.

Second, to rigorously evaluate model performance, we applied a daily resampling spatial cross-validation framework. The core of this framework was a daily 20% spatial holdout strategy, where a new independent set of stations was withheld each day to evaluate prediction accuracy. We compared three interpolation methods: OK, OKLR with a fixed lapse rate of −6.5 °C/km, and the operational LDAPS numerical weather prediction model (Section 3.3 and Section 3.4).

Third, we generated final daily temperature maps at 270 m resolution using OKLR with 100% of available station data (Section 3.5). These spatially continuous temperature surfaces provide high-resolution estimates suitable for applications that require a detailed representation of topographic temperature gradients across South Korea’s complex terrain.

3.2. Temperature Data Processing

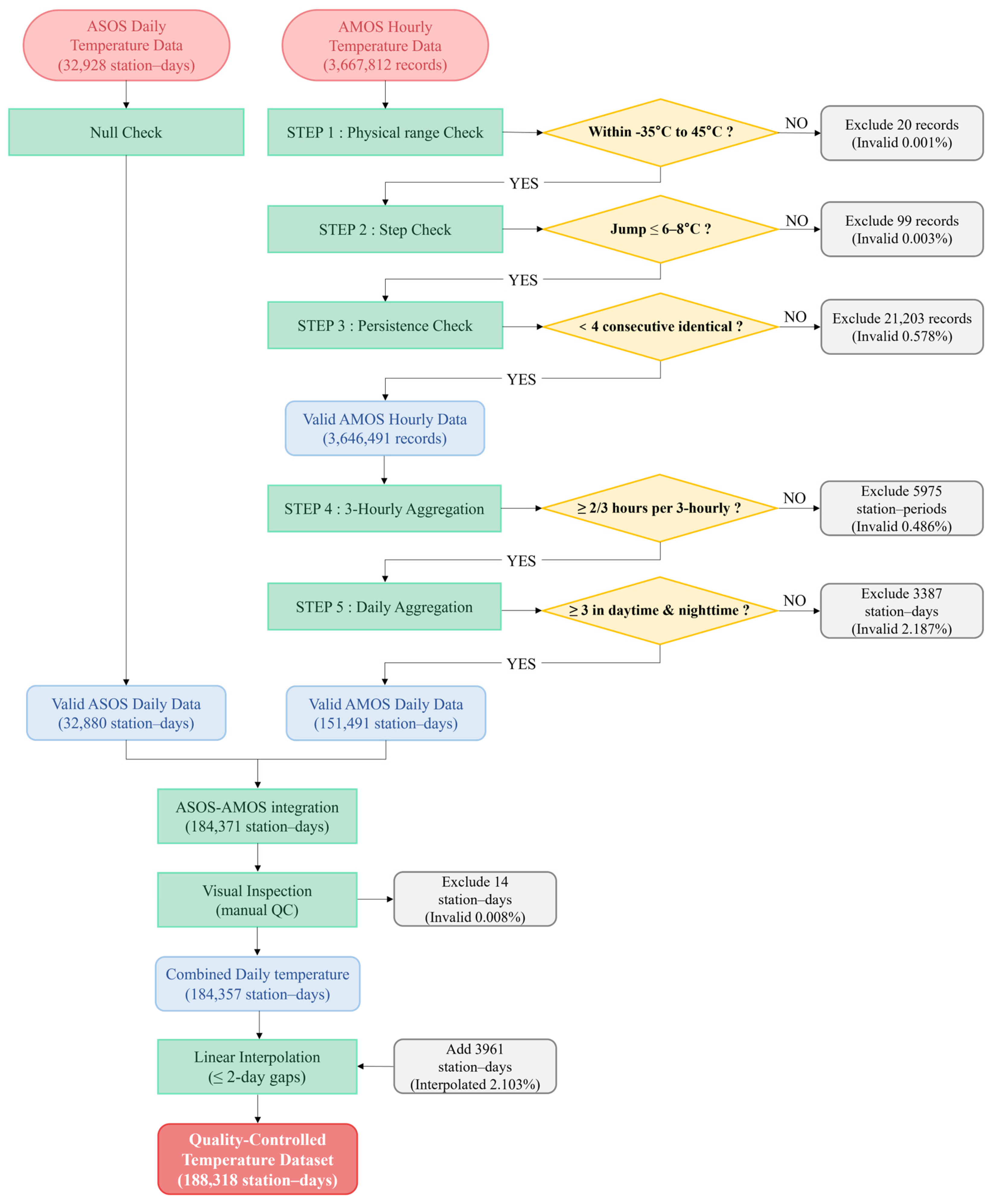

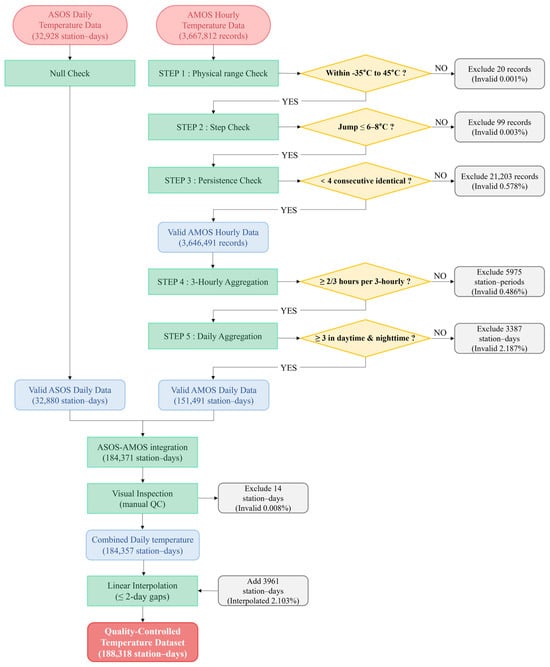

Temperature data processing included QC, temporal aggregation (for AMOS only), data integration, and gap-filling to ensure spatial and temporal consistency for subsequent spatial interpolation (Figure 4). QC procedures were designed to accommodate the characteristics of each observation network.

Figure 4.

Flowchart of temperature data processing and quality control procedures. ASOS data underwent null-value removal, while AMOS data required a multi-step processing framework comprising three quality-control steps (physical range, step, and persistence checks) and two-stage temporal aggregation (hourly to 3-hourly to daily). Following integration, visual inspection removed 14 spatially inconsistent station–days, and linear interpolation filled gaps of two days or less. Percentages in parentheses indicate the proportion of excluded or added data relative to the immediately preceding step.

3.2.1. Quality Control Procedures

ASOS data were obtained as daily mean temperatures that had undergone the KMA’s four-stage QC process (physical limit checks, step tests, persistence tests, and climate range tests) [25]. Visual inspection revealed no significant outliers except for missing values (coded as −99; 48 records). After removing these missing values, 32,880 valid station–days remained for analysis.

AMOS hourly data were obtained from 3,667,812 records processed through the KFS’s QC procedures, which are applied to minute-interval raw observations and include physical limit checks, step tests, persistence tests, climate range tests, and median filter tests. These QC procedures achieve approximately 98% data validity, ranking among the highest quality grades of 28 meteorological observation agencies [26]. However, since we extracted only top-of-hour values (00 min) to construct hourly temperature records, we applied additional QC and processing steps to this hourly dataset.

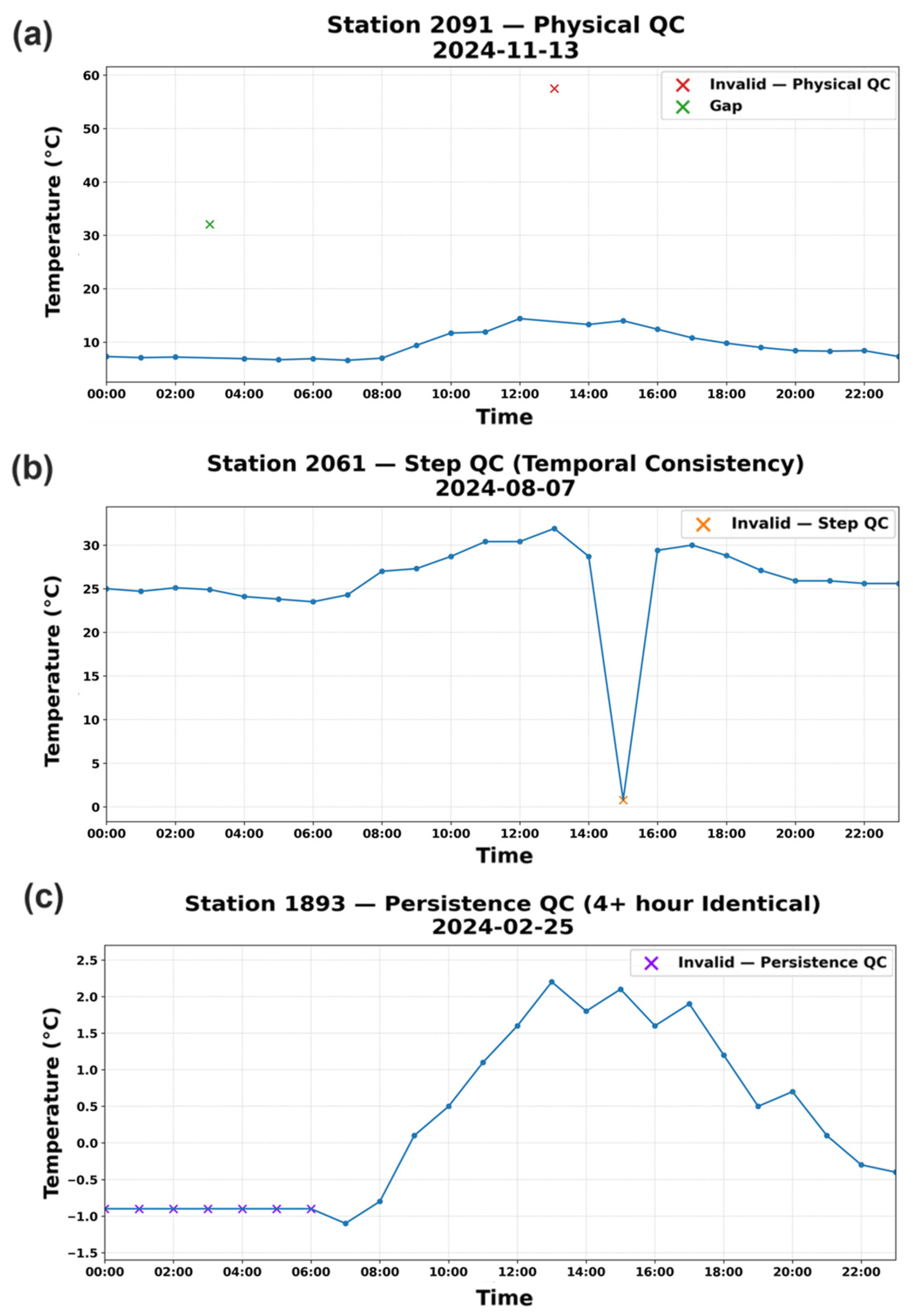

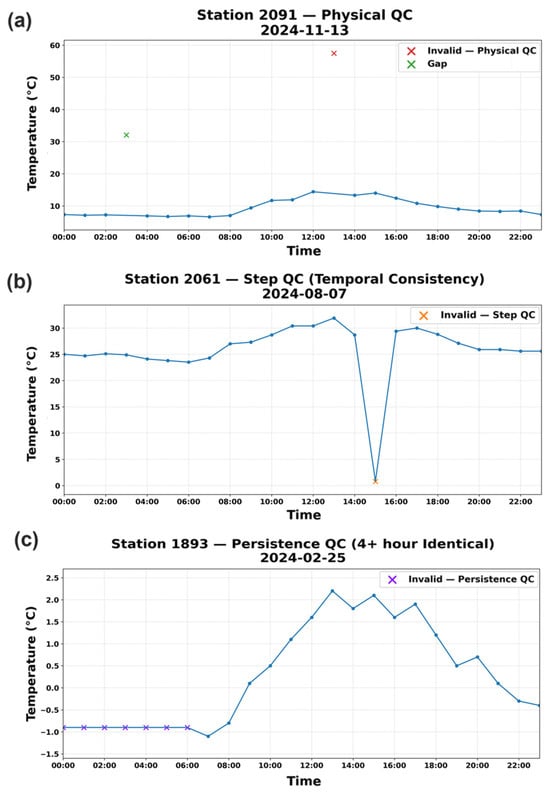

The framework consisted of five sequential steps. First, the physical range check excluded temperatures outside the range of −35 °C to 45 °C, adopting the more stringent boundary between KMA and KFS standards to ensure data quality, removing 20 records (0.001%, Figure 5a). Second, the step check identified abrupt temperature changes between consecutive hourly observations, following the KMA standard of 6 °C per hour [25], but with elevation-dependent differentiated criteria to account for greater natural temperature variability in mountainous terrain, the following apply: 6 °C for stations below 500 m, 7 °C for stations between 500 and 1000 m, and 8 °C for stations above 1000 m. This removed 99 records (0.003%, Figure 5b). Third, the persistence check removed periods showing four or more consecutive identical hourly values, which indicate sensor malfunction or data transmission errors, excluding 21,203 records (0.578%, Figure 5c). These three steps yielded 3,646,491 valid hourly records.

Figure 5.

Examples of quality control procedures applied to AMOS hourly temperature data. (a) Physical range check identifying values outside acceptable limits at station 2091. (b) Step check detecting an abrupt temperature drop exceeding the elevation-dependent threshold at station 2061. (c) Persistence check flagging four or more consecutive identical values at station 1893. Values were compared against the sensors’ recorded decimal precision.

Fourth, to minimize data loss due to missing values in the AMOS hourly dataset (extracted from top-of-hour values), the quality-controlled hourly data were aggregated into 3 hourly intervals by dividing the 24 h into eight 3 h blocks (00–03 h, 03–06 h, 06–09 h, 09–12 h, 12–15 h, 15–18 h, 18–21 h, and 21–24 h). A 3-hourly mean was calculated when at least two of the three hourly observations within each block were available. This step excluded 5975 station–periods (0.486%). Fifth, daily mean temperatures were calculated from the 3-hourly data, which required a proper representation of the diurnal temperature cycle. Specifically, we needed at least three of the four daytime blocks (06–18 h) and at least three of the four nighttime blocks (18–06 h) to ensure the daily mean captured a complete diurnal temperature cycle. This final aggregation step excluded 3387 station–days (2.187%), yielding 151,491 valid AMOS station–days.

3.2.2. Data Integration and Gap-Filling

Following QC, the ASOS and AMOS datasets were integrated (184,371 station–days). Since combining datasets from different observation networks can introduce spatial inconsistencies (e.g., sensor calibration differences and regional reporting biases), we performed additional spatial quality checks. Visual inspection of regional temperature patterns identified 14 station–days (0.008%) showing values inconsistent with nearby stations, which were excluded, resulting in 184,357 combined station–days.

To ensure spatial and temporal continuity for interpolation analysis, we applied linear interpolation to data gaps of two consecutive days or less. For each station, missing daily mean temperatures were estimated using linear interpolation based on observations before and after the gap period. Gaps exceeding two days were not filled to avoid introducing excessive uncertainty from long-term extrapolation. This gap-filling procedure added 3961 interpolated station–days (2.1% of the final dataset), producing a quality-controlled temperature dataset of 188,318 station–days comprising 184,357 original observations (97.9%) and 3961 interpolated values (2.1%). Interpolation rates differed by network: 0.50% for ASOS (165 of 33,045 station–days) and 2.44% for AMOS (3796 of 155,273 station–days), reflecting the more challenging observational conditions in mountainous terrain. To assess potential systematic differences between the two networks following the integration of ASOS and AMOS, we examined OKLR cross-validation residuals categorized by observation network and data status. The results of this diagnostic analysis are detailed in Appendix A (Table A1).

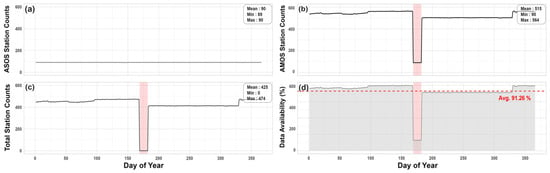

3.2.3. Temporal Data Availability

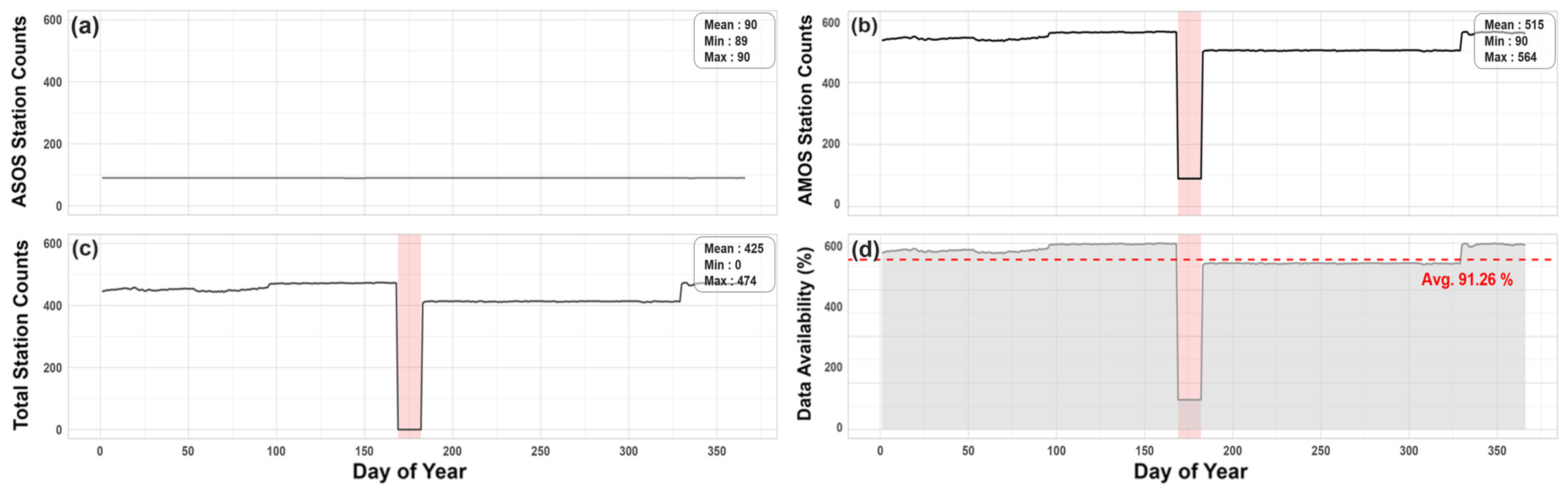

Temporal station availability during the study period showed contrasting patterns between the two observation networks (Figure 6). ASOS maintained consistent availability (mean: 90 stations per day), while AMOS showed greater variability (mean: 425 stations per day, range: 0–474) due to the challenges of operating automatic observation stations in remote mountainous areas. A complete AMOS network outage occurred from 17 to 30 June, during which only ASOS data were available. Despite this outage and sporadic missing data from QC procedures, overall data availability remained high at 91.26% (Figure 6d). To evaluate the impact of station density on interpolation accuracy, we conducted a comparative analysis of model performance during the AMOS outage period (17–30 June, with only ASOS being available) versus regular operation periods (both networks being available).

Figure 6.

Temporal availability of in situ air temperature observations in 2024. Daily counts of available stations for the (a) ASOS network, (b) AMOS network, and (c) combined total stations. (d) Overall data availability percentage (gray area) with the annual average shown as a red dashed line (91.26%). The highlighted period (pink shading) indicates 17–30 June, when the AMOS network experienced a complete outage, leaving only ASOS observations available.

3.3. Spatial Interpolation Methods

3.3.1. Automated Variogram Optimization for Ordinary Kriging

Kriging is a geostatistical interpolation method that estimates values at unobserved locations using the spatial covariance structure of the data [27]. Ordinary kriging, the standard form of kriging, uses a fitted variogram to produce unbiased estimates with minimum variance, making it a robust interpolation method [28].

The spatial prediction at an unmeasured location is computed as a weighted linear combination of neighboring observations:

where is the predicted value, are the kriging weights, are the observed values at neighboring locations, and the weight sum to unity (, ensuring unbiasedness.

The kriging weights are determined by the spatial correlation structure of the data, which is characterized by the variogram. The empirical (or experimental) variogram γ(h) quantifies spatial dissimilarity as a function of separation distance :

where is the number of observation pairs separated by distance .

To apply kriging, the empirical variogram must be fitted to a theoretical variogram model. In general, spherical, exponential, and Gaussian functions are used with three key parameters: the nugget (measurement error and micro-scale variation), the sill (total variance), and the range (the distance beyond which observations are no longer correlated). Accurate estimation of these parameters is crucial because they directly determine the kriging weights assigned to each observation point.

Cressie [29] proposed a weighted least squares (WLS) approach that optimizes variogram fitting by weighting each distance class by the number of observation pairs ():

where is the empirical variogram value and is the theoretical variogram value at distance , and the summation is over all distance classes .

We implemented ordinary kriging using the autoKrige function from the automap package (version 1.1.12) in R (version 4.3.3) [30], which automatically selects the optimal variogram model from multiple candidates (spherical, exponential, and Gaussian, among others) and estimates parameters through WLS optimization. In this study, we use the term “OK” to refer to this optimized implementation of ordinary kriging. The kriging weights are then derived from the optimized variogram through a system of linear equations that balances spatial covariance and the unbiasedness constraint (). This automated approach eliminates subjective manual fitting and ensures reproducible results.

This optimized ordinary kriging framework served as the foundation for both interpolation methods evaluated in this study (OK and OKLR), with the only difference arising in the treatment of elevation effects.

3.3.2. Lapse Rate Correction Approaches

OKLR removes the elevation trend before interpolation and reapplies it afterward, effectively separating the two-dimensional horizontal spatial pattern from the dominant vertical gradient. This approach combines physical foundations (elevation–temperature relationship) with statistical robustness (kriging) while remaining simple to implement and computationally efficient. Given these trade-offs, the OKLR approach emerges as a balanced solution. By explicitly incorporating the dominant physical process—the elevation–temperature relationship (lapse rate)—OKLR provides a middle ground between purely data-driven approaches (e.g., machine learning) and computationally intensive simulations (e.g., numerical weather prediction models). This detrending step isolates the vertical temperature gradient, allowing the kriging algorithm to focus on modeling the more subtle spatial dependencies of the horizontal residuals.

Table 1 compares the two interpolation methods based on the same optimized ordinary kriging framework: OK and OKLR. For the elevation-corrected method (OKLR), the interpolation process was methodologically designed to separate the underlying spatial temperature pattern from the dominant vertical trend imposed by elevation. This detrending is essential to satisfy the stationarity assumption of ordinary kriging (i.e., the assumption that the local mean is constant). By removing the confounding effects of topography, the kriging algorithm can more effectively model the residual spatial autocorrelation of the data. This is achieved through a three-step process.

Table 1.

Comparison of the two spatial interpolation methods. T_station refers to observed station temperature, T_0m is the equivalent sea-level temperature, T_grid_0m is the interpolated sea-level grid, and T_grid_surface is the final estimated temperature on the grid.

First, observed station temperatures were adjusted to mean sea level (0 m) by removing the elevation effect:

where LR is the standard atmospheric lapse rate of −6.5 °C/km [31], a widely used constant representing average tropospheric conditions. To ensure consistency between downward adjustments and upward corrections, we used elevations extracted from the same SRTM DEM used to produce the final grid, rather than the official station elevations. Second, these sea-level-adjusted temperatures were spatially interpolated to a 270 m grid using ordinary kriging. Third, the interpolated grid was readjusted to actual surface elevations using the SRTM DEM:

3.4. Validation Strategy

To robustly evaluate interpolation performance, we employed a daily resampling spatial cross-validation. For each day in the study period, 20% of the observation stations were randomly withheld as an independent validation set, while the remaining 80% were used for interpolation. To prevent geographic bias, this random selection was spatially stratified to ensure an even distribution of validation points across the study area. This entire process was repeated independently for each day, enabling a comprehensive assessment of method performance across numerous spatial configurations.

To ensure a direct and unbiased comparison, this validation protocol was applied identically to all methods (OK, OKLR, and LDAPS), yielding a total validation dataset of 37,813 station–days. The predictive accuracy of each method against this dataset was assessed using four standard metrics: mean bias error (MBE), mean absolute error (MAE), root mean square error (RMSE), and the correlation coefficient (CC). Additionally, we calculated the percentage improvement in MAE and RMSE for OKLR relative to OK.

where and are predicted and observed temperatures, respectively, and is the number of validation samples.

3.5. Final High-Resolution Temperature Maps

Following the validation assessment, we generated final daily temperature maps at a spatial resolution of 270 m for the entire study period (366 days in 2024), using 100% of available station data (90 to 564 stations per day, depending on ASOS and AMOS data availability). Unlike the validation phase, which withheld 20% of stations, we utilized all quality-controlled stations to maximize spatial coverage and interpolation accuracy. Daily mapping was performed using the OKLR method, based on the optimized ordinary kriging framework with lapse rate correction. The resulting gridded temperature surfaces covered the South Korean mainland (excluding Jeju Island) at a resolution of 270 m, aligned with the SRTM DEM grid.

4. Result and Discussion

4.1. Model Performance Evaluation

4.1.1. Overall Performance

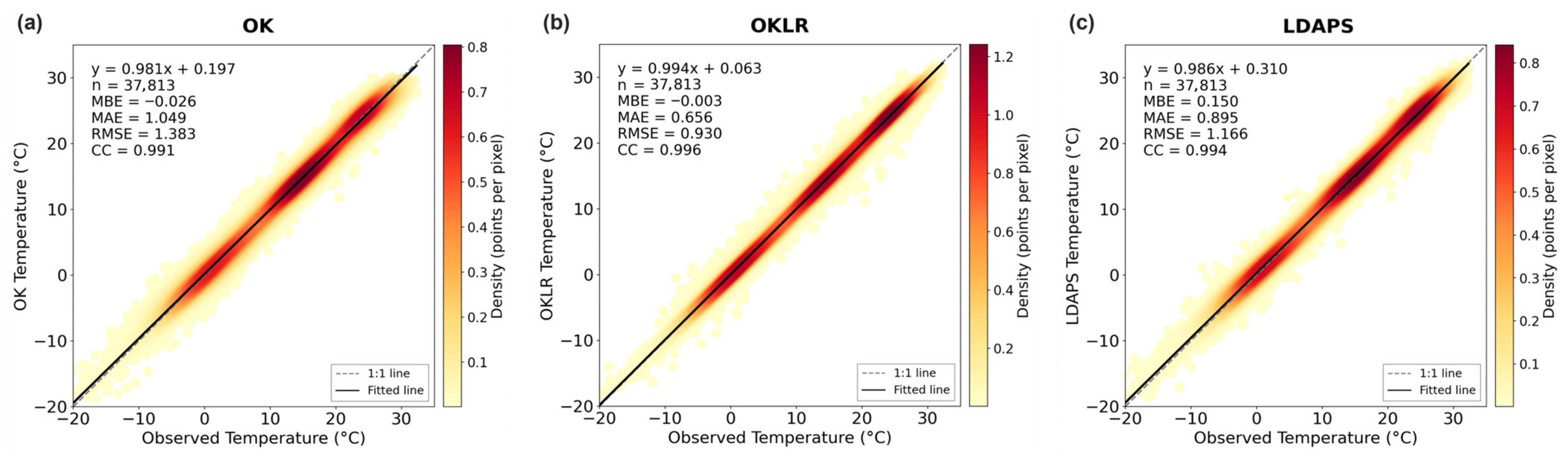

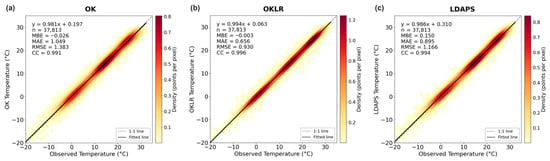

The overall predictive performance of the interpolation models was rigorously evaluated using a daily 20% spatial holdout cross-validation (CV) dataset (n = 37,813 station–days). Results (Table 2, Figure 7) demonstrate that OKLR achieved the highest accuracy with an MAE of 0.656 °C and RMSE of 0.930 °C. Compared to OK, OKLR demonstrated substantial improvements, reducing MAE and RMSE by 0.393 °C (37.5%) and 0.453 °C (32.8%), respectively. This underscores that kriging without elevation adjustment fails to adequately capture the steep vertical temperature gradients inherent in South Korea’s complex terrain. Furthermore, OKLR outperformed LDAPS—an operational numerical weather prediction product with 1.5 km resolution—by 0.239 °C in MAE and 0.236 °C in RMSE. While LDAPS showed superior performance compared to OK, it exhibited a systematic warm bias (MBE = 0.150 °C), whereas OKLR maintained a negligible bias (MBE = −0.003 °C).

Table 2.

Summary of performance metrics for the OK, OKLR, and LDAPS models over the entire study period (n = 37,813 station–days). Positive values in the MAE/RMSE difference columns denote higher errors relative to the OKLR model, which serves as the reference. Best scores are in bold.

Figure 7.

Density scatterplots comparing modeled vs. observed temperatures for three interpolation approaches: (a) OK, (b) OKLR, and (c) LDAPS. The 1:1 line (gray dashed) and linear regression fit (black solid) are shown. Inset text provides key performance metrics: sample size (n), MBE, MAE, RMSE, and correlation coefficient (CC).

The inset text within the scatterplots provides a deeper diagnostic view of model reliability and bias. The OKLR plot exemplifies the ideal scenario: its inset text shows a fitted regression line (y = 0.994x + 0.063) with a slope near one and an intercept near 0, which is strongly supported by its near-zero MBE of −0.003 °C and the strongest correlation (CC = 0.996). In contrast, LDAPS (Figure 7c) exhibited systematic warm bias (y = 0.986x + 0.310, MBE = 0.150 °C) despite showing high correlation (CC = 0.994). OK (Figure 7a) showed the most significant errors (RMSE = 1.383 °C and CC = 0.991), confirming that elevation correction is essential for accurate temperature mapping in mountainous regions.

4.1.2. Seasonal Variations in Performance

To evaluate model stability across different meteorological regimes, performance was analyzed for each season (Table 3). OKLR demonstrated excellent and stable performance throughout the year, with MAE ranging from 0.571 °C (summer) to 0.705 °C (fall) and near-zero MBE across all seasons (−0.014 °C to 0.007 °C), indicating no systematic bias. In contrast, LDAPS exhibited significant seasonal warm bias, particularly in summer (0.230 °C) and winter (0.189 °C). This bias is consistent with known limitations of numerical models in complex terrain, which often struggle to resolve extreme local thermal conditions due to inadequate representation of fine-scale topography and sub-grid-scale processes [32,33,34].

Table 3.

Seasonal performance evaluation of the interpolation models. Best scores are in bold.

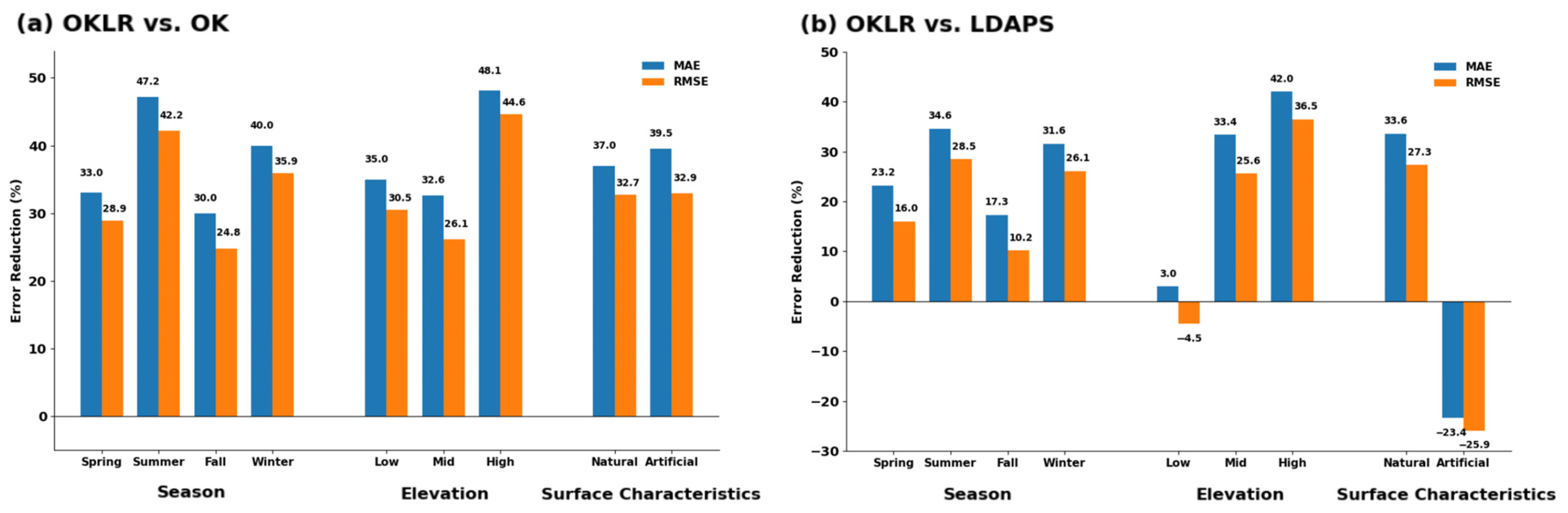

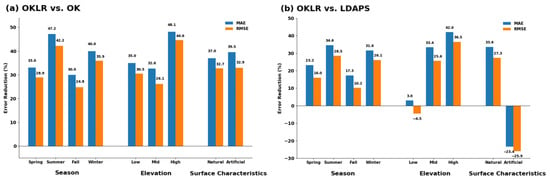

Relative improvement metrics exhibit distinct seasonal patterns (Figure 8). Compared to OK (Figure 8a), OKLR achieved the most substantial reductions in MAE and RMSE during summer (47.2% and 42.2%, respectively), followed by winter (40.0% and 35.9%), spring (33.0% and 28.9%), and fall (30.0% and 24.8%). OKLR consistently outperformed the operational LDAPS product across all seasons (Figure 8b), maintaining the same seasonal ranking; the most pronounced relative improvements occurred in summer (34.6% MAE and 28.5% RMSE) and winter (31.6% MAE and 26.1% RMSE). This pattern is physically consistent with summer atmospheric conditions, where enhanced solar heating and turbulent mixing facilitate well-mixed boundary layers and stable daily mean lapse rates [10]. Under such conditions, the explicit elevation correction employed by OKLR provides a distinct advantage in resolving fine-scale orographic temperature gradients.

Figure 8.

Relative error reduction achieved by OKLR compared to (a) OK and (b) LDAPS across seasons, elevation classes (low: <300 m, mid: 300–700 m, high: >700 m), and surface characteristics (natural vs. artificial). Blue and orange bars represent MAE and RMSE reductions, respectively.

Transitional seasons (spring and fall) showed relatively smaller performance gaps. This reflects the seasonal characteristics of transition periods, which experience increased synoptic-scale variability due to the frequent passage of mobile high- and low-pressure systems and frontal activity, with rapidly changing air-mass properties [35]. Under these conditions, the consistency of daily boundary-layer structure and vertical lapse rates weakens, thereby naturally reducing the relative advantages of OKLR’s elevation correction approach that assumes stable height-dependent temperature patterns. Nevertheless, OKLR maintained lower errors than both OK and LDAPS, with fall showing the smallest but still meaningful improvements (30.0% relative to OK and 17.3% relative to LDAPS).

Winter’s substantial improvements (40.0% relative to OK, 31.6% relative to LDAPS) reflect stabilized daily mean lapse rates despite nocturnal inversions and cold-air pooling. Although enhanced radiative cooling promotes local-scale temperature inversions at night, daytime mixing re-establishes coherent elevation-dependent structure at regional scales, and reduced diurnal amplitude stabilizes daily mean gradients. Under these conditions, OK showed the largest errors (MAE: 1.102 °C), while LDAPS exhibited elevated errors and warm bias (MAE: 0.967 °C and MBE: 0.189 °C). OKLR effectively captured this structure (MAE: 0.661 °C and MBE: −0.014 °C), demonstrating robust elevation-based correction for winter conditions.

4.1.3. Performance Across Different Elevation and Surface Characteristics

Performance stratification by elevation and surface type (Table 4, Figure 8) demonstrates OKLR’s effectiveness across diverse landscapes. In high-elevation areas (>700 m), OKLR achieved the lowest errors (MAE: 0.640 °C and RMSE: 0.889 °C), significantly outperforming OK (Figure 8a) by 48.1% (MAE) and 44.6% (RMSE), and LDAPS (Figure 8b) by 42.0% and 36.5%. These results highlight the critical importance of explicit lapse rate correction in altitude-dominated zones. In mid-elevation regions (300–700 m), OKLR maintained strong performance (MAE: 0.613 °C and RMSE: 0.888 °C), with consistent improvements over OK (32.6% MAE and 26.1% RMSE) and LDAPS (33.4% MAE and 25.6% RMSE).

Table 4.

Model performance evaluation stratified by elevation class and surface characteristics. Best scores are in bold.

In low-elevation areas (<300 m), LDAPS yielded the best RMSE (0.959 °C), surpassing OKLR (1.002 °C) by 4.5% (indicated by negative bars in Figure 8b). This reflects LDAPS’s explicit representation of surface energy balance and heterogeneous land-surface characteristics [18] in areas where orographic effects are less pronounced. Nevertheless, OKLR still substantially outperformed OK (35.0% MAE, 30.5% RMSE).

Regarding surface types, OKLR exhibited superior performance for natural surfaces (n = 32,355; MAE: 0.612 °C, RMSE: 0.867 °C), with improvements of 37.0% and 32.7% over OK, and 33.6% and 27.3% over LDAPS, respectively. For artificial surfaces, LDAPS achieved the best performance (MAE: 0.744 °C and RMSE: 0.985 °C) due to its land-use-specific parameterizations [36], outperforming OKLR by 23.4% (MAE) and 25.9% (RMSE). However, OKLR showed substantial gains over OK (39.5% MAE and 32.9% RMSE), demonstrating that lapse rate correction remains valuable even in complex anthropogenic landscapes. Overall, OKLR’s superiority in natural areas—which comprise the majority of the national territory—and its competitive performance in challenging regions underscore its robustness for generating high-resolution national-scale temperature datasets. These findings indicate that the effectiveness of lapse-rate correction is not uniform but is contingent upon boundary-layer stability and dominant temperature controls.

4.1.4. Sensitivity to Observation Density

A 14-day AMOS network outage (17–30 June; n = 252 station–days) provided a natural experiment to test model robustness under sparse observational conditions (Table 5, Figure 6). This period, when only the sparse ASOS network was available, mirrors many earlier ASOS-only interpolation studies and reveals fundamental trade-offs between data-driven geostatistical and physics-based modeling approaches.

Table 5.

Model performance sensitivity to observation network density during the AMOS data gap period (17 to 30 June). Best scores are in bold.

Under sparse network conditions, geostatistical models are inherently sensitive to observation density, while physics-based LDAPS is relatively less affected by network gaps. Consequently, LDAPS achieved the lowest errors (MAE: 0.649 °C, RMSE: 0.835 °C, and CC: 0.888) despite a modest cold bias (MBE: −0.211 °C). Nevertheless, OKLR maintained substantial advantages over OK even under these challenging conditions, achieving error reductions of 16.9% in MAE and 20.4% in RMSE (OKLR: MAE 0.745 °C, RMSE 1.013 °C, OK: MAE 0.896 °C, and RMSE 1.272 °C), demonstrating that lapse-rate correction yields consistent benefits even under sparse observations.

Because this is a period-specific natural experiment, performance differences likely reflect both station density and concurrent meteorological regimes. Even so, LDAPS outperforming optimized OKLR during the outage suggests that ASOS-only configurations are generally insufficient—especially in complex terrain—to reproduce fine-scale temperature patterns. This underscores the critical importance of maintaining specialized mountain observation networks, such as AMOS; such networks enable data-driven geostatistical methods to realize their full potential in generating high-resolution temperature maps.

4.2. Characterization of the High-Resolution Daily Temperature Dataset

4.2.1. Dataset Specifications and Overall Accuracy

Following the validation assessment in Section 4.1, we generated the final high-resolution daily temperature dataset for South Korea using all available station data. In contrast to the cross-validation stage, which employed a daily 20% spatial holdout for independent evaluation, the final reanalysis utilized the full set (100%) of quality-controlled observations to maximize spatial coverage and interpolation accuracy. In this context, “reanalysis” refers to an observation-based geostatistical reconstruction derived from in situ stations, rather than a product of NWP-based data assimilation. The resulting dataset, named the OKLR Daily Temperature Reanalysis for South Korea, provides spatially continuous temperature fields at 270 m resolution covering the entire 2024 calendar year (366 days including leap day). Table 6 summarizes the technical specifications: 270 m spatial resolution; daily interpolation from 90 to 564 stations; and an interpolation method of ordinary kriging with lapse-rate correction (OKLR; optimized variogram selection) with a fixed lapse rate of −6.5 °C/km. The spatial domain encompasses mainland South Korea (excluding islands such as Jeju), and all grids are provided in WGS84/UTM Zone 52N GeoTIFF format.

Table 6.

Specifications of the 270 m daily mean temperature reanalysis dataset for South Korea.

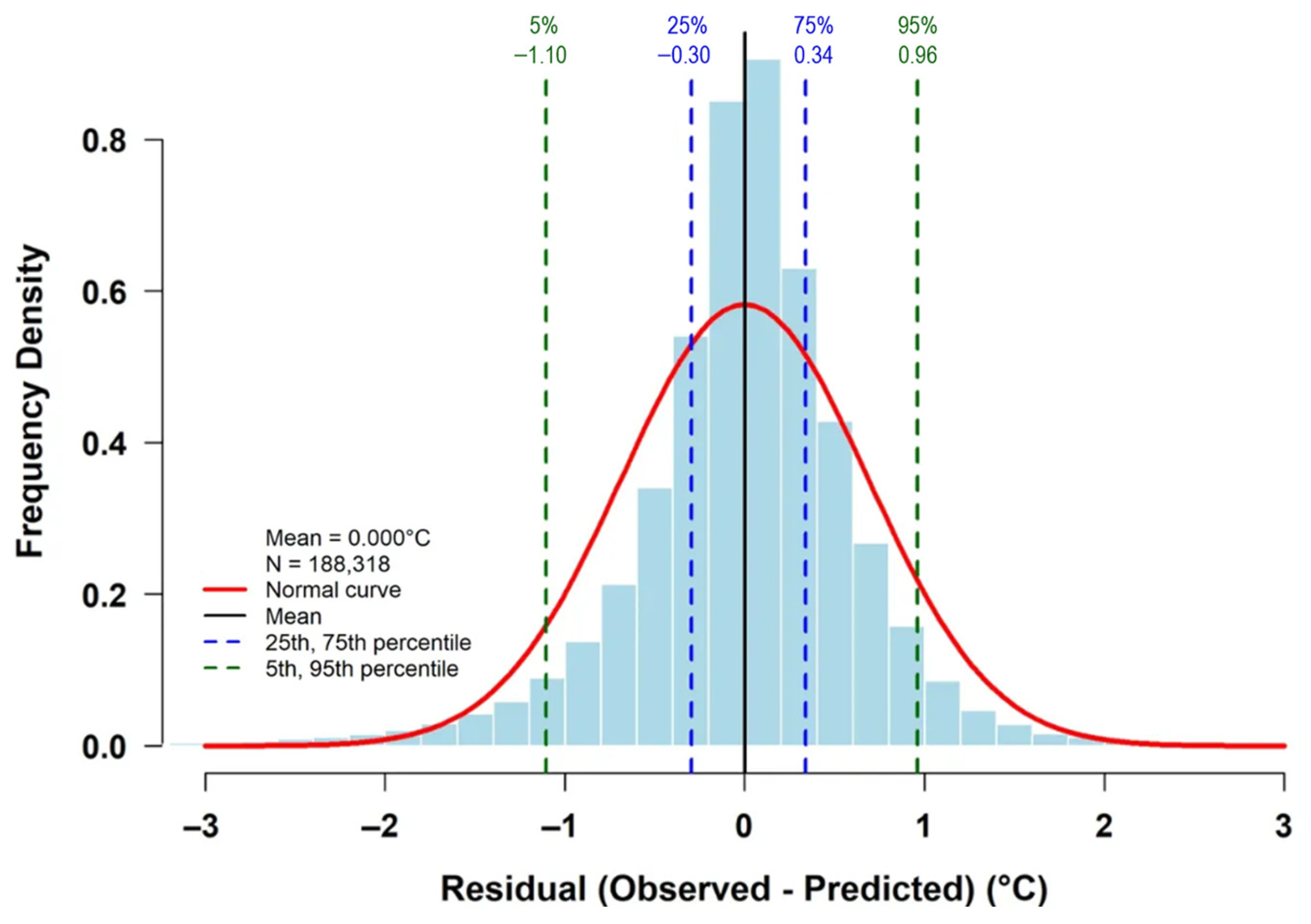

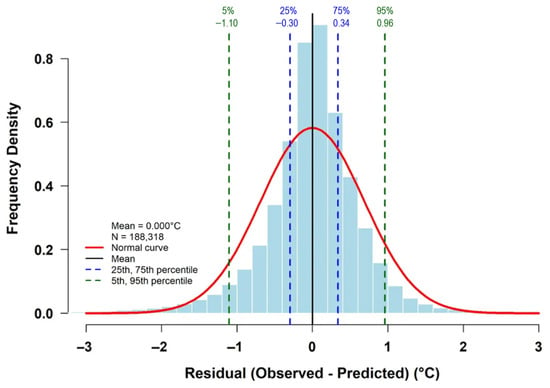

To assess the overall quality of the final reanalysis, OKLR predictions were evaluated against all station observations (n = 188,318 station–days) throughout the year (Table 7). With this in-sample evaluation, the reanalysis achieved an MAE of 0.462 °C, an RMSE of 0.685 °C, and a CC of 0.998, with near-zero MBE (≈0.000 °C). The enhanced accuracy relative to the cross-validation results in Section 4.1 (MAE = 0.656 °C; n = 37,813) is attributable to the increased observational constraints provided by the full station network, rather than any modifications to the interpolation procedure itself. The residual distribution (Figure 9) is nearly Gaussian, centered at zero, with 67.1% of predictions within ±0.5 °C, 89.5% within ±1.0 °C, and 98.1% within ±2.0 °C of the observations. These results complement, rather than supersede, the independent cross-validation presented in Section 4.1, further validating the product’s suitability for regional-scale applications.

Table 7.

Overall accuracy assessment of the OKLR reanalysis at weather station locations.

Figure 9.

Distribution of OKLR temperature residuals (observed–predicted) for 188,318 station–days in 2024. The nearly Gaussian distribution centered at zero demonstrates unbiased performance, with 67.1% within ±0.5 °C, 89.5% within ±1.0 °C, and 98.1% within ±2.0 °C. Dashed lines indicate percentiles (5th, 25th, 75th, and 95th); the red curve shows the regular fit.

4.2.2. Climatological Characteristics and Seasonal Variation

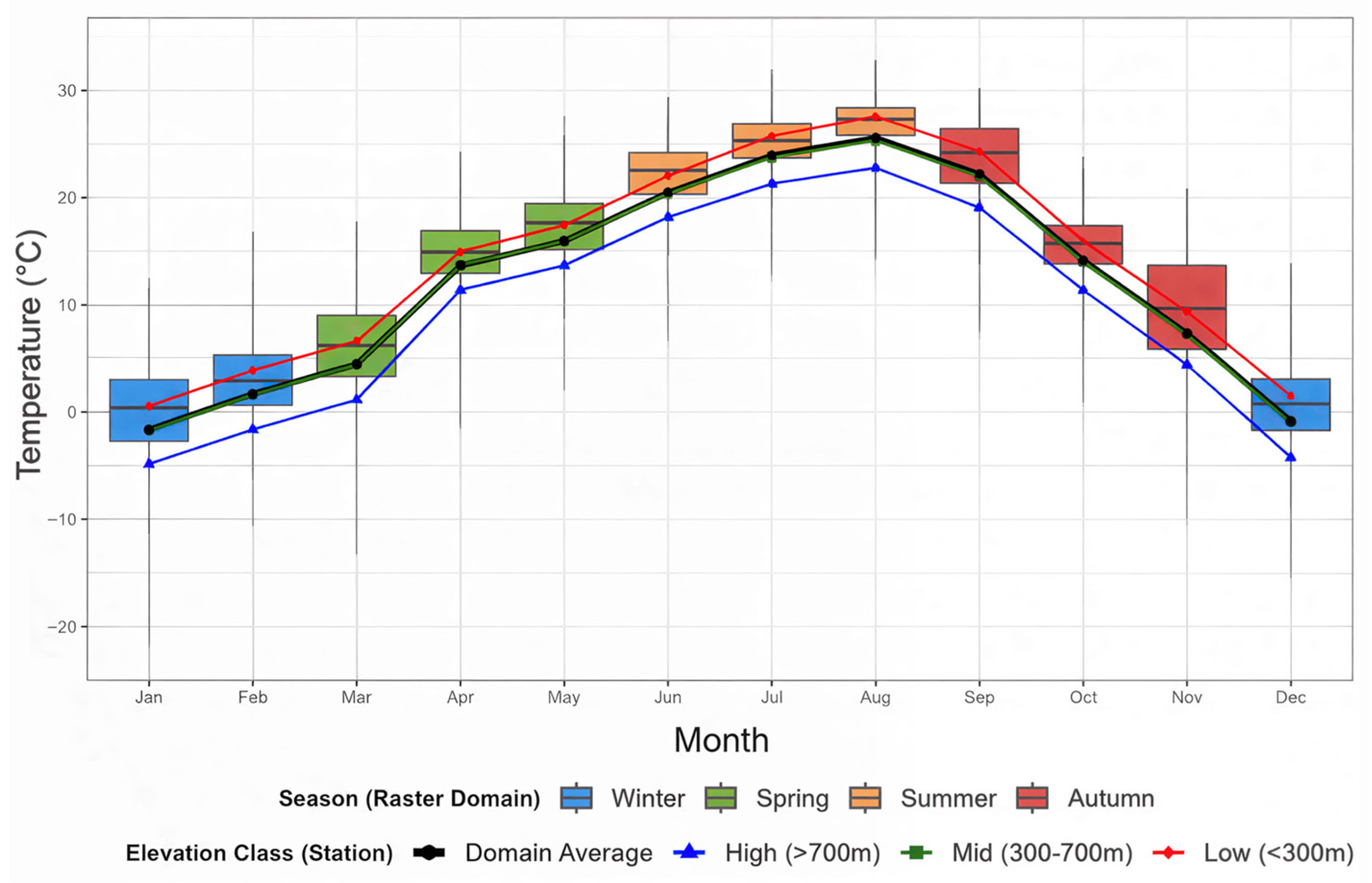

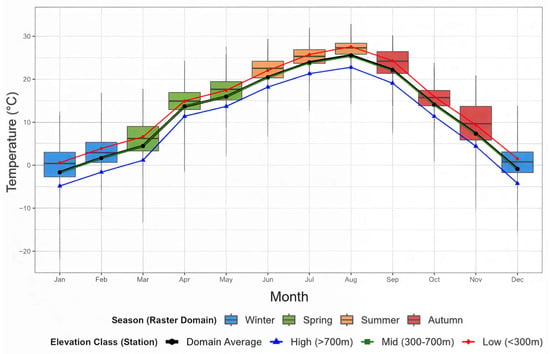

Beyond accuracy verification, the final reanalysis dataset must demonstrate its ability to capture realistic climatological and seasonal characteristics of South Korea. The monthly temperature statistics for the entire 270 m gridded domain are summarized in Table 8 and visualized in the monthly boxplots in Figure 10. The dataset successfully captures South Korea’s distinct four-season climate, with domain-averaged mean temperature ranging from −0.160 °C in January (the coldest month) to 26.918 °C in August (the warmest month). This clear annual cycle is also evident in the figure’s medians (black lines).

Table 8.

Monthly temperature statistics for the interpolated 270 m gridded dataset over South Korea (2024). Q25, Median, and Q75 represent the 25th, 50th, and 75th percentiles, respectively. IQR denotes the interquartile range (Q75–Q25). P01 and P99 represent the 1st and 99th percentiles, capturing extreme temperature values. SD denotes standard deviation. Statistics are computed across all grid cells (N ≈ 48–49 million pixels per month).

Figure 10.

Monthly distributions of reconstructed temperatures and elevation-stratified station means. Boxplots illustrate the seasonal dynamics of gridded temperatures (270 m resolution), with the box width reflecting the spatial variability within each month. Colored lines represent mean temperatures at in situ stations stratified by elevation: high (>700 m), mid (300–700 m), and low (<300 m). The black line denotes the domain-wide average across all stations.

More importantly, the dataset realistically captures seasonal changes in spatial variability. The IQRs (Table 8) show that spatial variability across the domain peaks in November (7.766 °C), remains elevated in winter (e.g., January: 5.698 °C), and is minimized in summer (e.g., August: 2.505 °C; July: 3.142 °C). This seasonal expansion and contraction of spatial variability is clearly reflected in the raster-domain boxplots (Figure 10), which exhibit the greatest dispersion during autumn and winter and the narrowest in summer. Concurrently, the elevation-stratified station means (represented by lines) reveal a more pronounced temperature contrast between low and high elevations in winter (≈5.26–5.64 °C) compared to summer (≈3.74–4.50 °C). Notably, November combines the largest IQR (7.77 °C) with only moderate elevation contrast (≈4.6 °C), suggesting that transitional-season synoptic variability—rapid air-mass changes and frequent frontal passages—amplifies horizontal contrasts among regions at similar elevations, thereby reducing the relative dominance of vertical (elevation-driven) gradients [36].

4.2.3. Spatial Distribution Patterns and Model Comparison

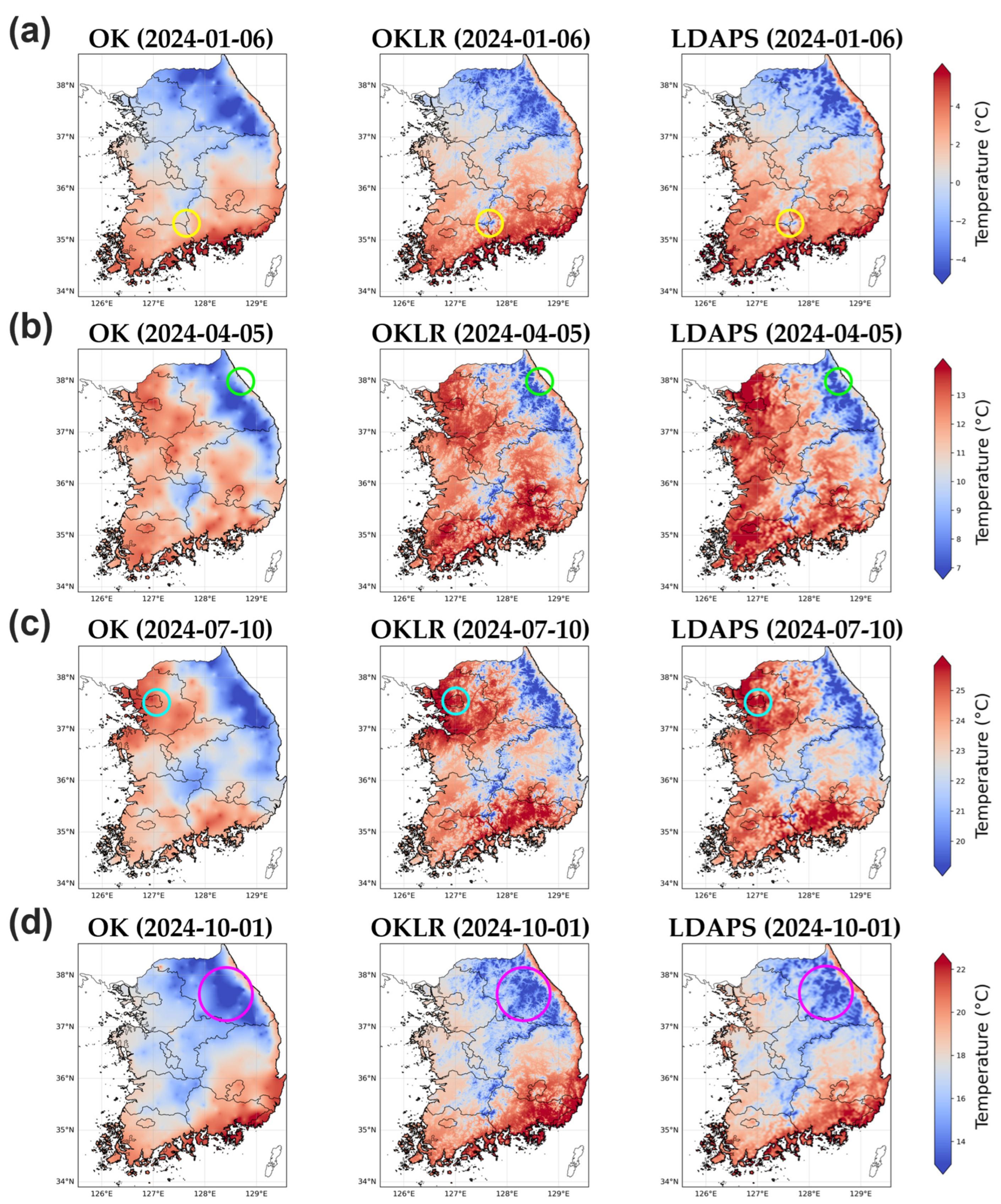

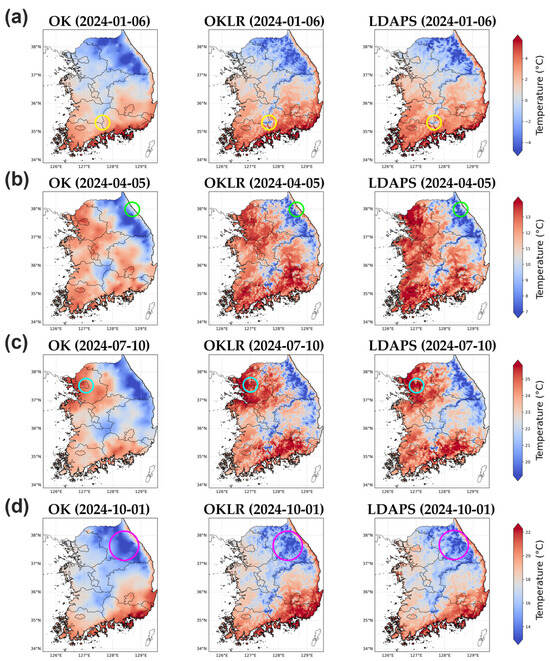

To qualitatively assess the spatial realism and physical consistency of the OKLR reanalysis, we compared daily temperature maps for representative dates from four seasons (Figure 11). The figure presents three-way comparisons: OK (left column), OKLR (center column), and LDAPS (right column), with rows representing winter (6 January), spring (5 April), summer (10 July), and fall (1 October), all from 2024.

Figure 11.

Spatial distribution of daily mean temperature fields generated by OK (left), OKLR (center), and LDAPS (right) across four representative dates in 2024. The selected dates represent (a) winter (6 January), (b) spring (5 April), (c) summer (10 July), and (d) autumn (1 October). Colored circles highlight specific regions where inter-model discrepancies are most pronounced due to varying sensitivities to topography and land cover. OKLR consistently captures fine-scale, elevation-driven temperature gradients aligned with the 270 m DEM. In contrast, OK exhibits a topography-insensitive, over-smoothed representation, while LDAPS reflects broader-scale meteorological patterns with smoothed terrain gradients limited by its 1.5 km native resolution.

The circled regions in Figure 11 highlight representative cases where these inter-model discrepancies are most pronounced. In the southern mountainous regions (yellow circles, January), OK is prone to topography-insensitive over-smoothing, which excessively blends cold mountain air masses with warmer conditions on the plains. While LDAPS identifies cold temperature distributions at high elevations, it lacks sufficient spatial detail at its native resolution. Conversely, OKLR more effectively resolves the abrupt temperature gradients between mountains and plains. Along the eastern coast (green circle, April), where the Taebaek Mountains rise steeply from the shoreline, significant temperature variations occur over short distances. The OK approach fails to distinguish these contrasting air masses, and LDAPS exhibits smoothing across the sharp coastal–inland transition. OKLR, however, successfully resolves this transition zone, clearly discriminating between the cold mountainous interior and the warmer coastal areas.

The northern mountainous regions (pink circles, October) and the Seoul metropolitan area (cyan circle, July) further demonstrate OKLR’s spatial fidelity across different terrain types. In the high-relief mountainous regions of Gangwon-do, including the Seoraksan area, OK generates vague cooling patterns that do not correspond to actual topography. Concurrently, while LDAPS captures broad-scale cold conditions, it lacks the necessary fine-scale spatial detail. In contrast, OKLR precisely reconstructs the temperature field in a manner consistent with the 270 m DEM, clearly resolving individual ridges and sheltered valleys. Furthermore, the Seoul metropolitan area (cyan circle, July) demonstrates OKLR’s robustness in urban settings; it captures localized thermal patterns that are over-smoothed in elevation-unadjusted kriging (OK) and represented more diffusely in LDAPS.

In summary, OKLR consistently reconstructed across all seasons and regions by integrating elevation-based temperature gradients that elevation-unadjusted kriging misses. Furthermore, while LDAPS effectively captures broad-scale meteorological patterns at a 1.5 km resolution, OKLR achieves a more physically realistic representation of terrain-driven temperature gradients by leveraging elevation-constrained interpolation. This approach allows for a finer integration of topographic effects that are often under-resolved in coarser numerical weather prediction products. This combination of observational fidelity, physical consistency, and fine-scale resolution makes OKLR particularly valuable for applications in complex terrain where topographic temperature variations drive critical processes in hydrology, ecology, and agriculture.

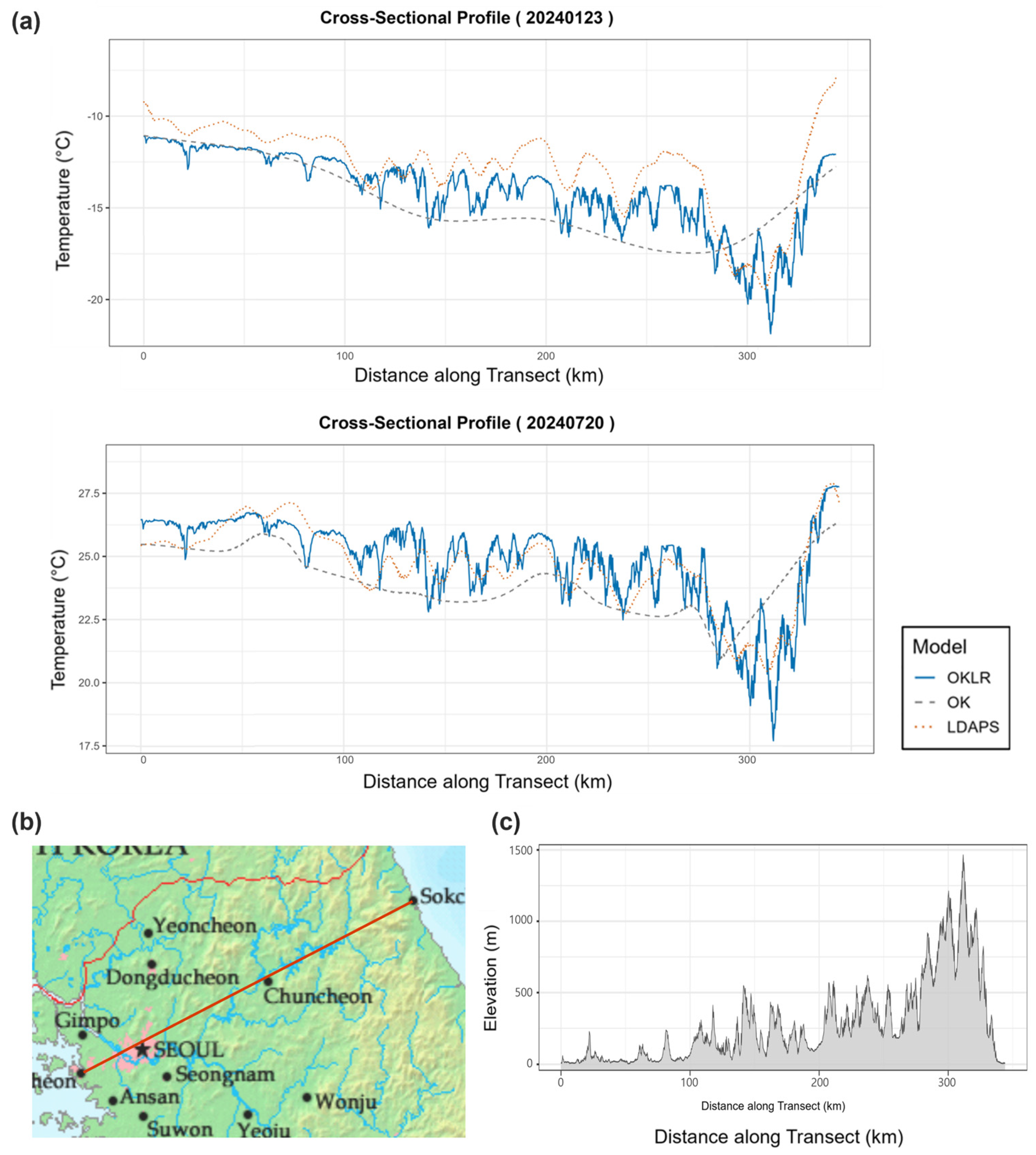

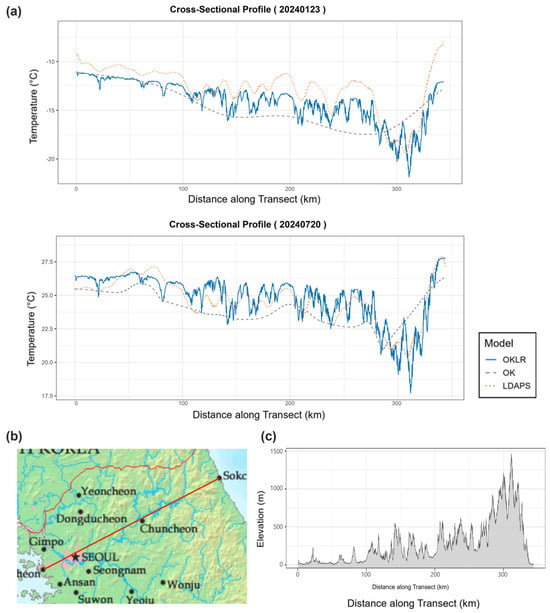

4.2.4. Topographic Cross-Sectional Analysis

To evaluate the OKLR model’s performance in capturing topography-induced temperature variations, we analyzed cross-sectional temperature profiles along a transect from Incheon Songdo (126.66° E, 37.40° N) to Sokcho, Gangwon Province (128.58° E, 38.20° N). This approximately 345 km transect crosses diverse terrain, including coastal lowlands, urban areas, and mountainous regions exceeding 1400 m elevation (Figure 12b). Figure 12a presents cross-sectional temperature profiles for two representative cases: a cold wave event on 23 January 2024 (upper panel) and a heat wave event on 20 July 2024 (lower panel). The elevation profile (Figure 12c) begins at coastal lowlands, rises gradually through the central section, then increases sharply in the eastern mountainous region (after approximately 250 km), reaching its peak at Seoraksan National Park (>1400 m).

Figure 12.

(a) Temperature comparisons for a cold wave (23 January 2024, top) and heat wave (20 July 2024, bottom) showing OKLR (blue), OK (gray), and LDAPS (orange). (b) Transect location map spanning 345 km from coastal lowlands to mountainous terrain. (c) Elevation profile showing topographic variations from sea level to >1400 m in Seoraksan National Park.

The cross-sectional analysis reveals distinct differences in how each model represents temperature variations across diverse terrain. The most pronounced inter-model differences occur in the high-elevation region and its transition zone (approximately 200–345 km). In this mountainous area where observation station density decreases due to Seoraksan’s rugged terrain, the OK model generates overly simplified temperature patterns that do not respond to local elevation changes, producing smooth curves that connect temperatures at available station locations while ignoring intermediate topographic complexity. This behavior is particularly evident during the heat wave event (20 July), when the OK temperature profile shows a monotonic decrease followed by a smooth increase, despite continuous elevation changes in the actual terrain (Figure 12c).

In contrast, the OKLR model explicitly incorporates terrain effects through elevation-based adjustment, generating temperature fields that respond realistically to local topographic variations, even in data-sparse mountainous regions. Compared with OKLR, LDAPS generally follows elevation-dependent cooling patterns but exhibits diminished spatial detail due to its coarser horizontal resolution (1.5 km). During the cold wave event (23 January), LDAPS consistently produced lower temperatures across the entire transect. This discrepancy highlights the fundamental differences in how physics-based numerical models and observation-constrained geostatistical reconstructions represent temperature structures within complex terrain.

4.3. Error Analysis and Quality Assessment

4.3.1. Environmental Drivers of Prediction Errors

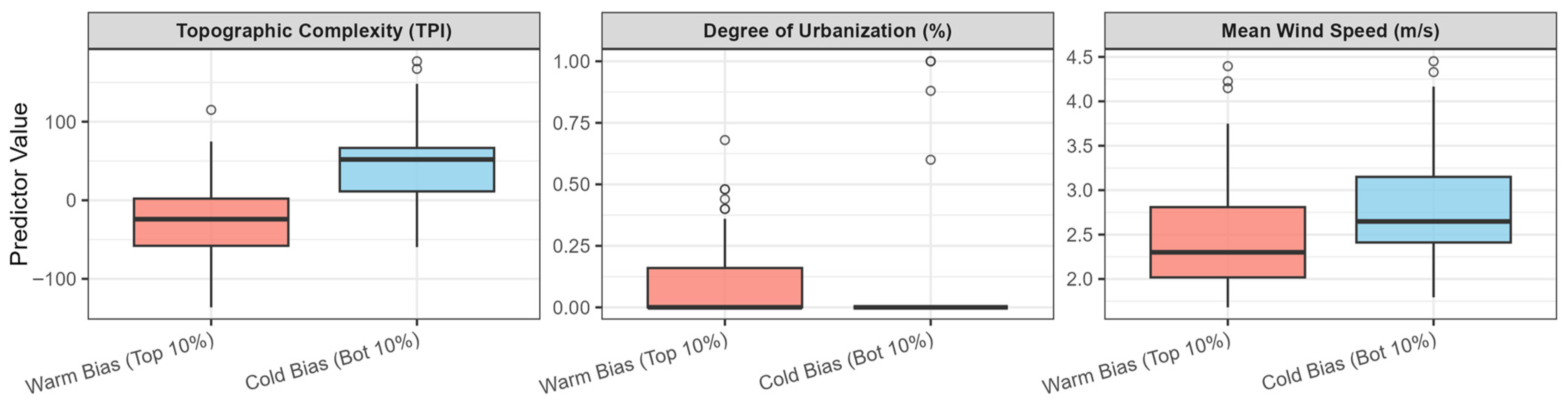

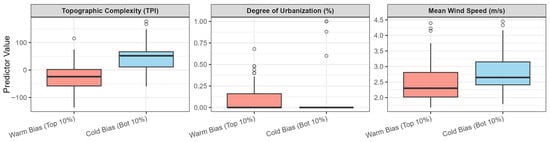

To identify the underlying conditions of OKLR’s systematic errors, we profiled environmental predictors associated with extreme bias directions (Figure 13). We compared warm bias (top 10% positive MBE: model overestimation) with cold bias (bottom 10% negative MBE: model underestimation).

Figure 13.

Environmental drivers of OKLR systematic biases. Boxplots compare topographic complexity (TPI), urbanization percentage, and mean wind speed between warm bias (top 10% positive MBE indicates model overestimates, depicted in red) and cold bias (bottom 10% negative MBE indicates model underestimates, depicted in blue). The circles represent individual observations that fall beyond the boxplot whiskers.

Topographic Position Index (TPI) emerged as the dominant predictor with non-overlapping interquartile ranges (IQRs) and only limited crossover outside the IQRs. Warm bias (median TPI: −24.0 and IQR: −58.0 to 2.1) occurred predominantly in valleys, while cold bias (median TPI: 52.0 and IQR: 11.4 to 66.6) occurred predominantly on ridges. Warm bias occurs in valleys with relatively low wind speeds (2.30 m/s) because nocturnal radiative cooling and cold-air drainage under stable atmospheric conditions make actual temperatures much lower than lapse-rate predictions [37]. For example, if the model predicts 5 °C but cold-air pooling results in an observed −2 °C, a 7 °C overestimation occurs (MBE = +7 °C). Conversely, cold bias occurs on ridges with relatively stronger winds (2.65 m/s) because mechanical mixing maintains warmer temperatures than lapse-rate predictions [38]. If the model predicts −1 °C but turbulent mixing results in an observed 2 °C, a 3 °C underestimation occurs (MBE = −3 °C).

Urbanization analysis also showed a clear pattern: stations with top-10% errors exhibited significantly higher urbanization rates (IQR range: 0.0–16.1%), whereas stations with bottom-10% errors were completely non-urban (IQR range: 0.0–0.0%). This indicates that OKLR fails to capture urban heat island (UHI) effects, resulting in underestimation in urban areas.

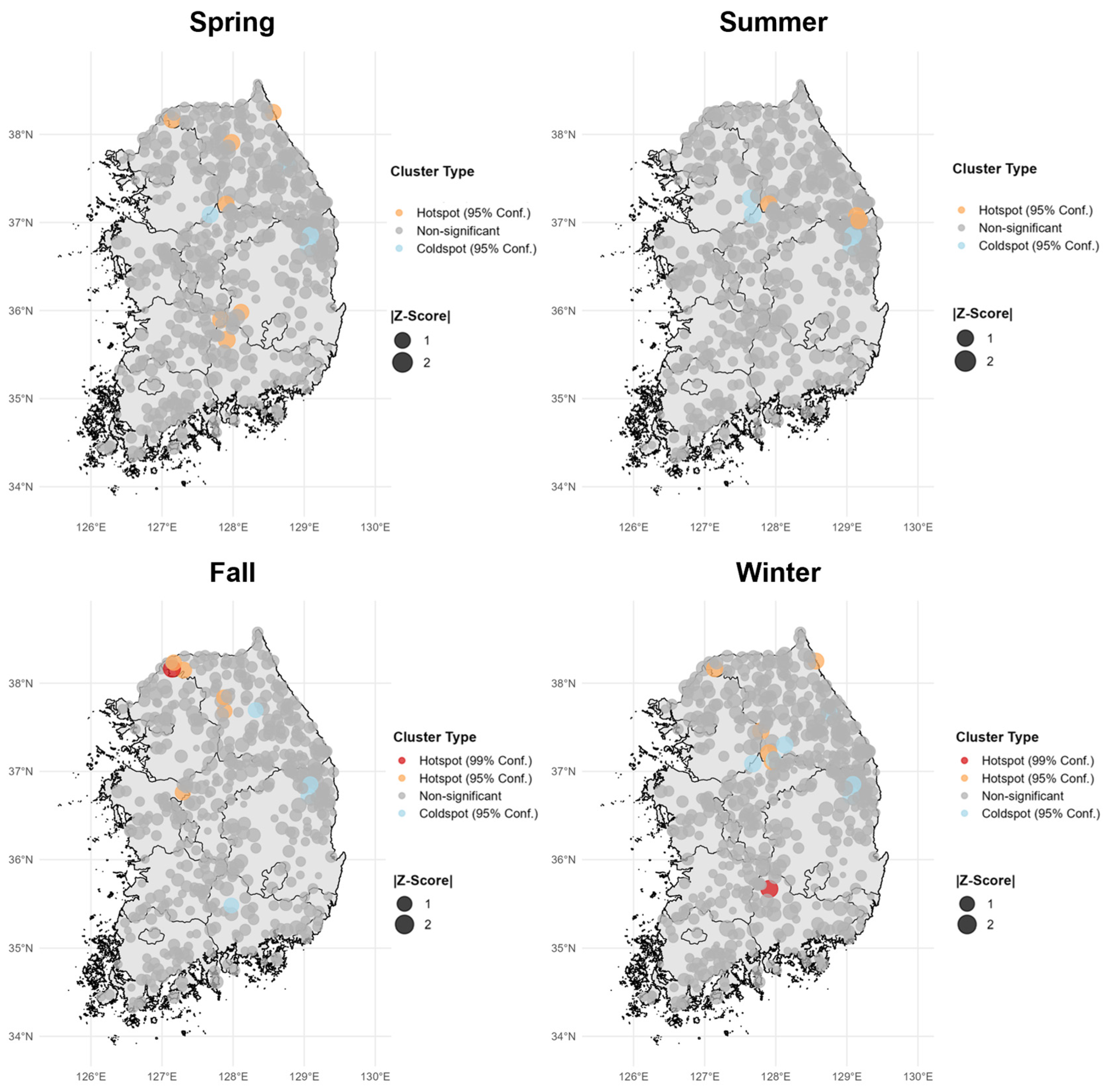

4.3.2. Spatial Autocorrelation of Interpolation Errors

To assess the spatial patterns of OKLR errors, we first used the global Moran’s I statistic and found no significant global clustering (all 366 days: p > 0.05; |I| generally < 0.3). We then performed seasonal Getis-Ord Gi* hotspot analysis to detect local clusters (Figure 14, Table 9). Unlike global statistics, Gi* identifies local clustering by comparing the mean value near each station to the overall domain distribution. We applied dual criteria: statistical significance (moderate at p < 0.05 and strong at p < 0.01) and practical magnitude (moderate at |Z| > 1.96 and strong at |Z| > 2.58).

Figure 14.

Seasonal Getis-Ord Gi* hotspot analysis of OKLR mean biases. Colored points indicate significant spatial clustering (95% or 99% confidence); gray points are non-significant. Point size represents |Z-score|.

Table 9.

Seasonal summary of Getis-Ord Gi* hotspot analysis for OKLR mean biases. Strong and moderate clusters indicate statistically significant spatial clustering at 99% and 95% confidence levels, respectively. Over 98% of station–season observations showed no considerable clustering (p ≥ 0.05), confirming spatially random error distribution.

The analysis revealed minimal spatial clustering across all seasons (Figure 14, Table 9). Approximately 98% of the 2135 station–season combinations showed no significant clustering (p ≥ 0.05), with only 40 significant sites identified (1.9%). These were categorized by statistical strength into two strong clusters (p < 0.01, |Z| > 2.58) and 38 moderate clusters (p < 0.05, 1.96 < |Z| ≤ 2.58). The significant clusters were geographically dispersed across the domain (35.5–38.3° N, 127.1–129.2° E) and showed no consistent spatial patterns associated with specific topographic features.

From a temporal persistence perspective, only five stations (0.9% of the entire network) showed repeated clustering with perfect directional consistency across multiple seasons. Notably, two stations (stations 42 and 7896) exhibited persistent coldspots across all four seasons, indicating systematic overestimation. Both sites feature exposed ridges (TPI 160, 75) and strong mean wind speeds (3.6 m/s, 3.0 m/s), where—as identified in Section 4.3.1—mechanical mixing maintains warmer temperatures than lapse rate predictions, causing overestimation. An additional three stations showed consistent clustering across 3 seasons, but these persistent clusters accounted for only 0.2% of all station–season combinations, suggesting localized issues.

In terms of statistical strength, the two strong clusters (p < 0.01) appeared in single seasons only and exhibited contrasting characteristics. Station 1939 (fall) showed the highest Z-score (2.97, p = 0.003) and the most significant absolute bias (−3.96 °C). This station has valley-topography (TPI = −24.04) and relatively low wind speed (2.2 m/s)—conditions that often produce warm bias via cold-air pooling—yet it exhibited a cold bias instead. A plausible explanation is a combination of sub-grid elevation/siting mismatch that over-corrected temperatures downward during the lapse-rate adjustment and/or daytime mixing that elevated observed temperatures above the simple lapse-rate expectation, yielding a negative MBE despite the valley setting. In contrast, Station 284 (winter) showed a high Z-score (2.61, p = 0.009) despite a slight absolute bias (0.96 °C), indicating highly consistent warm-bias clustering in a low-error region. This occurred because low wind speed (1.8 m/s) and stable winter conditions led to strong cold-air pooling, which suppressed the typical urban heat island effect, resulting in cold temperatures. Both strong clusters showed no significant clustering in other seasons, suggesting complex interactions of specific season–topography conditions rather than fundamental model deficiencies. The balanced distribution of hotspots (55%) and coldspots (45%) confirms the absence of directional bias.

This overwhelming prevalence of non-significant clustering (98%) demonstrates that OKLR errors are inherently spatially random across South Korea’s diverse terrain. The small number of persistent clusters (<0.5% of observations) does not indicate systematic regional bias but suggests a potential need for localized improvements in future implementations.

4.4. Capabilities and Limitations

This study generated daily temperature data for the entire South Korean mainland using the OKLR framework and evaluated it through a multi-faceted validation framework. Our approach has three key strengths. First, this study provides national-scale coverage at a 270 m grid spacing, surpassing many previous studies that were restricted to local domains or coarser resolutions [39,40,41,42]. Second, the complete annual coverage (366 days) enables robust characterization of seasonal variability, complementing many existing studies that focused on limited periods such as single months or specific dates [43,44]. Third, the validation framework explicitly examines performance across seasons, elevations, and surface characteristics, allowing users to understand when and where the dataset can be reliably applied.

Several limitations of this study warrant mention. First, the application of a fixed lapse rate (−6.5 °C km−1) represents a deliberate simplification to prioritize robustness and reproducibility over the explicit modeling of lapse-rate variability. Although empirical lapse rates fluctuate seasonally and diurnally, sensitivity tests indicate that incorporating season-specific mean lapse rates does not yield consistent performance gains at the national scale (Appendix B, Table A2). This reflects a strategic trade-off between physical granularity and operational stability in daily nationwide mapping.

Second, the relatively modest improvements observed in low-elevation and artificial (urban) surfaces underscore the limitations of lapse-rate-based corrections in environments where non-orographic processes—such as urban heat island effects, land–sea breeze circulations, and heterogeneous surface energy balances—predominate. In these contexts, the marginally superior performance of LDAPS suggests that explicitly resolving surface–atmosphere interactions can be advantageous. Future work could complement OKLR by incorporating additional covariates representing near-surface controls (e.g., built-up fraction, land-cover class, distance to coast, and TPI) within a regression-kriging or hybrid framework, particularly for metropolitan and coastal regions.

Regarding uncertainty, while kriging provides prediction variance as an internal measure, the variance within the OKLR framework reflects uncertainty associated solely with spatial sampling and variogram fitting of the detrended residual field. It does not account for errors arising from the fixed lapse-rate assumption, DEM-based retrending, or unresolved near-surface processes. Thus, users are encouraged to rely on the residual-based diagnostics and stratified error summaries provided herein to avoid overconfidence in uncertainty estimates.

Overall, the resulting 270 m dataset is well-suited for climate change impact assessments, ecological modeling, and hydrological simulations, especially in mountainous regions where elevation-driven gradients dominate. While this reconstruction offers superior spatial detail compared to conventional NWP models, it is specialized for high-fidelity temperature representation rather than providing the multi-modal environmental complexity (e.g., radiation, humidity) found in coarser numerical simulations. By transparently characterizing these capabilities and limitations, this study enables informed decision-making regarding the dataset’s suitability for specific applications.

5. Conclusions

Our work makes three key contributions. First, we developed and applied a rigorous QC framework to integrate observations from the recently established high-elevation AMOS network with the traditional ASOS. This integration creates an unprecedented high-density (500+ stations) dataset, ensuring both high data reliability and vastly improved spatial representation in complex terrain. Second, by leveraging this dense observation network, we applied the OKLR framework at a 270 m grid spacing across the entire South Korean mainland—achieving a level of spatial detail and regional scope that would be unattainable using sparse conventional networks alone. Third, we developed and applied a comprehensive, multi-faceted validation framework to rigorously establish the OKLR model’s stability and reliability. This includes the following: predictive accuracy assessment using daily resampling spatial cross-validation; comparative analysis against OK and LDAPS across diverse seasons and terrain types (elevation and surface characteristics); robustness evaluation under abrupt changes in observation density (AMOS network outage); and environmental diagnosis of model residuals using spatial autocorrelation analysis. This multi-layered validation transparently characterizes the model’s actual capabilities and limitations, clarifying not only average performance but when, where, and why the model excels or exhibits constraints.

This study developed and validated the first nationwide, daily high-resolution (270 m) temperature reanalysis dataset for South Korea, utilizing the OKLR framework. The main findings are as follows:

- (1)

- Utilizing integrated data from 500+ stations combining AMOS and ASOS networks, OKLR achieved an MAE of 0.656 °C and an RMSE of 0.930 °C in spatial cross-validation. This represents substantial MAE improvements of 37.5% over OK and 26.7% over LDAPS, resulting from explicit incorporation of elevation–temperature relationships.

- (2)

- The improvement peaked at 48.1% over OK and 42.0% over LDAPS in high-elevation zones (>700 m) where elevation gradients dominate temperature patterns. Seasonal analysis revealed that OKLR performance varies with atmospheric conditions. Performance was highest in summer (47.2% better than OK and 34.6% better than LDAPS), reflecting stable and consistent lapse rates. Natural land surfaces, such as forest and grassland, showed superior improvements (37.0% better than OK and 33.6% better than LDAPS).

- (3)

- The final reanalysis dataset achieved MAE of 0.462 °C, RMSE of 0.685 °C, and near-zero bias (MBE ≈ 0.000 °C) across 188,318 station–days. Monthly analysis captured distinct seasonal patterns (winter: –0.16 °C and summer: 26.92 °C) and realistic spatial variability.

- (4)

- Error analysis demonstrated that systematic biases are confined to specific terrain-meteorology combinations and are physically interpretable. TPI clearly separated bias directions, and spatial autocorrelation analysis confirmed spatially random error distribution with 98% of station–season combinations showing no significant clustering.

Future research should extend in several directions. Multi-year validation is essential to confirm long-term stability. Furthermore, incorporating temporally varying lapse rates and additional covariates—such as urban fraction, distance to the coast, and TPI—could enhance model performance across transitional seasons and complex landscapes.

In conclusion, this study provides a nationwide, annual, high-resolution daily temperature dataset for South Korea’s complex terrain and quantitatively demonstrates the substantial value of lapse rate correction. By transparently characterizing the model’s capabilities and limitations, this research enables practitioners to assess the dataset’s suitability for specific applications. Notably, the analysis reveals that OKLR and LDAPS exhibit complementary strengths: LDAPS excels in resolving surface-atmosphere interactions in lowlands, whereas OKLR offers superior fidelity in mountainous regions owing to its direct observational grounding. These findings provide practical guidance for generating high-resolution temperature fields essential for climate change adaptation, precision agriculture, and ecosystem monitoring in topographically diverse environments.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.Y., S.H.K. and Y.L.; methodology, Y.Y., S.H.K. and Y.L.; formal analysis, Y.Y.; data curation, Y.Y.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.Y.; writing—review and editing, S.H.K., M.K. and Y.L.; supervision, Y.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by Korea Environment Industry & Technology Institute (KEITI) through the project “Developing an Observation-based GHG Emissions Geospatial Information Map”, funded by Korea Ministry of Climate, Energy and Environment (MCEE) (RS-2023-00232066). This work was supported by Korea Environment Industry & Technology Institute (KEITI) through Research and Development on the Technology for Securing the Water Resources Stability in Response to Future Change Project, funded by Korea Ministry of Climate, Energy and Environment (MCEE) (RS-2024-00332300). This research was supported by the Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF), funded by the Ministry of Education (RS-2025-25431067).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The dataset generated during this study is publicly available in Zenodo at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17627307. The R scripts used for spatial interpolation and the Python scripts used for data preprocessing are not publicly released at this stage; however, the processing workflow and methodological details are fully described in the manuscript to ensure reproducibility. The analyses were performed using R (version 4.3.3) and Python (version 3.10.12). The scripts can be made available upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

| AMOS | Automatic Mountain Meteorology Observation System |

| ASOS | Automated Surface Observing System |

| CC | Correlation Coefficient |

| DEM | Digital Elevation Model |

| IQR | Interquartile Range |

| KFS | Korea Forest Service |

| KMA | Korea Meteorological Administration |

| LDAPS | Local Data Assimilation and Prediction System |

| MAE | Mean Absolute Error |

| MBE | Mean Bias Error |

| OK | Ordinary Kriging |

| OKLR | Ordinary Kriging with Lapse-Rate Correction |

| QC | Quality Control |

| RMSE | Root Mean Square Error |

| SRTM | Shuttle Radar Topography Mission |

| TPI | Topographic Position Index |

| UHI | Urban Heat Island |

| WLS | Weighted Least Squares |

Appendix A. Examination of Inter-Network Residual Characteristics

Table A1.

Summary of OKLR cross-validation residual statistics stratified by observation network (ASOS vs. AMOS) and data status (original vs. interpolated), including n, MBE, MAE, and RMSE. The inter-network offset persists for original observations, indicating that it is not an artifact of gap-filling; its magnitude exceeds what would be expected from the 0.5 m sensor height difference alone and likely reflects broader differences in station environment and spatial representativeness.

Table A1.

Summary of OKLR cross-validation residual statistics stratified by observation network (ASOS vs. AMOS) and data status (original vs. interpolated), including n, MBE, MAE, and RMSE. The inter-network offset persists for original observations, indicating that it is not an artifact of gap-filling; its magnitude exceeds what would be expected from the 0.5 m sensor height difference alone and likely reflects broader differences in station environment and spatial representativeness.

| Network | Data Status | n | MBE (°C) | MAE (°C) | RMSE (°C) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ASOS | Original | 6674 | 0.357 | 0.859 | 1.160 |

| Interpolated | 11 | 0.094 | 1.340 | 2.290 | |

| AMOS | Original | 30,316 | −0.074 | 0.596 | 0.837 |

| Interpolated | 812 | −0.292 | 1.230 | 1.730 |

Appendix B. Sensitivity of OKLR to Seasonal Lapse-Rate Variability

Table A2.

Seasonal mean empirical lapse rates and sensitivity of OKLR performance to using season-specific mean lapse rates (OKLR_Seasonal). Season-specific mean lapse rates were applied uniformly within each season, but did not yield consistent improvements over the fixed lapse-rate OKLR, supporting the fixed lapse rate (−6.5 °C km−1) for robust daily mapping.

Table A2.

Seasonal mean empirical lapse rates and sensitivity of OKLR performance to using season-specific mean lapse rates (OKLR_Seasonal). Season-specific mean lapse rates were applied uniformly within each season, but did not yield consistent improvements over the fixed lapse-rate OKLR, supporting the fixed lapse rate (−6.5 °C km−1) for robust daily mapping.

| Season | Seasonal Mean LR (°C km−1) | LR SD (°C km−1) | OKLR (Fixed LR) MAE (°C) | OKLR (Seasonal Mean LR) MAE (°C) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spring | −5.53 | 2.25 | 0.677 | 0.662 |

| Summer | −5.57 | 1.34 | 0.571 | 0.576 |

| Fall | −6.21 | 1.37 | 0.705 | 0.707 |

| Winter | −7.19 | 1.66 | 0.661 | 0.676 |

References

- Haylock, M.; Hofstra, N.; Klein Tank, A.; Klok, E.; Jones, P.; New, M. A European daily high-resolution gridded data set of surface temperature and precipitation for 1950–2006. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2008, 113, D20119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotlarski, S.; Szabó, P.; Herrera, S.; Räty, O.; Keuler, K.; Soares, P.M.; Cardoso, R.M.; Bosshard, T.; Pagé, C.; Boberg, F.; et al. Observational uncertainty and regional climate model evaluation: A pan-European perspective. Int. J. Climatol. 2019, 39, 3730–3749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodson, R.; Marks, D. Daily air temperature interpolated at high spatial resolution over a large mountainous region. Clim. Res. 1997, 8, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyler, J.W.; Dobrowski, S.Z.; Ballantyne, A.P.; Klene, A.E.; Running, S.W. Artificial amplification of warming trends across the mountains of the western United States. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2015, 42, 153–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daly, C. Guidelines for assessing the suitability of spatial climate data sets. Int. J. Climatol. 2006, 26, 707–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutchinson, M.F. Interpolation of rainfall data with thin plate smoothing splines. Part I: Two dimensional smoothing of data with short range correlation. J. Geogr. Inf. Decis. Anal. 1998, 2, 139–151. [Google Scholar]

- Cressie, N. Statistics for Spatial Data; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Goovaerts, P. Geostatistics for Natural Resources Evaluation; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Nalder, I.A.; Wein, R.W. Spatial interpolation of climatic normals: Test of a new method in the Canadian boreal forest. Agric. For. Meteorol. 1998, 92, 211–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stahl, K.; Moore, R.; Floyer, J.; Asplin, M.; McKendry, I. Comparison of approaches for spatial interpolation of daily air temperature in a large region with complex topography and highly variable station density. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2006, 139, 224–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunsdon, C.; McClatchey, J.; Unwin, D. Spatial variations in the average rainfall-altitude relationship in Great Britain: An approach using geographically weighted regression. Int. J. Climatol. 2001, 21, 455–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appelhans, T.; Mwangomo, E.; Hardy, D.R.; Hemp, A.; Nauss, T. Evaluating machine learning approaches for the interpolation of monthly air temperature at Mt. Kilimanjaro, Tanzania. Spat. Stat. 2015, 14, 91–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonsoms, J.; Ninyerola i Casals, M. Comparison of linear, generalized additive models and machine learning algorithms for spatial climate interpolation. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 2024, 155, 1777–1792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zandi, O.; Zahraie, B.; Nasseri, M.; Behrangi, A. Stacking machine learning models versus a locally weighted linear model to generate high-resolution monthly precipitation over a topographically complex area. Atmos. Res. 2022, 272, 106159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reichstein, M.; Camps-Valls, G.; Stevens, B.; Jung, M.; Denzler, J.; Carvalhais, N.; Prabhat, F. Deep learning and process understanding for data-driven Earth system science. Nature 2019, 566, 195–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hersbach, H.; Bell, B.; Berrisford, P.; Hirahara, S.; Horányi, A.; Muñoz-Sabater, J.; Nicolas, J.; Peubey, C.; Radu, R.; Schepers, D.; et al. The ERA5 global reanalysis. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 2020, 146, 1999–2049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fick, S.E.; Hijmans, R.J. WorldClim 2: New 1-km spatial resolution climate surfaces for global land areas. Int. J. Climatol. 2017, 37, 4302–4315. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, D.-J.; Kang, G.; Kim, D.-Y.; Kim, J.-J. Characteristics of LDAPS-predicted surface wind speed and temperature at automated weather stations with different surrounding land cover and topography in Korea. Atmosphere 2020, 11, 1224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.H.; Chung, E.S.; Shahid, S. Spatiotemporal differences and uncertainties in projections of precipitation and temperature in South Korea from CMIP6 and CMIP5 general circulation models. Int. J. Climatol. 2021, 41, 5899–5919. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, G.; Lee, D.E. Changing human-sensible temperature in Korea under a warmer monsoon climate over the last 100 years. Int. J. Biometeorol. 2020, 64, 729–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noh, G.H.; Ahn, K.H. New gridded rainfall dataset over the Korean peninsula: Gap infilling, reconstruction, and validation. Int. J. Climatol. 2022, 42, 435–452. [Google Scholar]

- Yoon, S.; Jang, K.; Won, M. The spatial distribution characteristics of Automatic Weather Stations in the mountainous area over South Korea. Korean J. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2018, 20. [Google Scholar]

- Yoon, S.; Won, M.; Jang, K. A Study on Optimal Site Selection for Automatic Mountain Meteorology Observation System (AMOS): The Case of Honam and Jeju Areas. Korean J. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2016, 18, 208–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Hijmans, R.J.; Cameron, S.E.; Parra, J.L.; Jones, P.G.; Jarvis, A. Very high resolution interpolated climate surfaces for global land areas. Int. J. Climatol. 2005, 25, 1965–1978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.W.; Jung, S.K. A study on the development of quality control algorithm for internet of things (IoT) urban weather observed data based on machine learning. J. Korea Water Resour. Assoc. 2021, 54, 1071–1081. [Google Scholar]

- Jang, K.C.; Min, S.H.; Kim, I.H.; Chun, J.H.; Won, M.S. Mountain meteorology data for forest disaster prevention and forest management. Korean J. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2022, 24, 346–352. [Google Scholar]

- Mitas, L.; Mitasova, H. Spatial interpolation. In Geographical Information Systems: Principles, Techniques, Management and Applications; Longley, P.A., Goodchild, M.F., Maguire, D.J., Rhind, D.W., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1999; Volume 1, pp. 481–492. [Google Scholar]

- Wackernagel, H. Multivariate Geostatistics: An Introduction with Applications, 3rd ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2003. [Google Scholar]