Abstract

This systematic review synthesizes current scientific knowledge on the drivers of climate variability and change across the South Pacific, with a particular focus on mechanisms influencing tropical cyclone behavior and regional hydroclimatic extremes. The review begins by contextualizing the unique vulnerabilities of Pacific Island nations, which arise from geographic isolation, socio-economic constraints, and extensive coastal exposures. It examines the foundational role of the South Pacific Convergence Zone in organizing regional convection and precipitation and explores the multi-scale climate oscillations that modulate environmental conditions across interannual, decadal, and intraseasonal timescales. The compounding effects of anthropogenic climate change—including rising temperatures, sea-level increase, shifting rainfall regimes, and changing storm characteristics—are critically assessed. Special attention is given to the complex interplay between natural variability and human-induced trends in altering tropical cyclone genesis, tracks, and intensity. The review identifies persistent knowledge gaps, such as data inhomogeneity, limited long-term records, and uncertainties in downscaled projections, and concludes with prioritized research directions aimed at enhancing predictive capacity and supporting climate-resilient adaptation across this highly vulnerable region.

1. Introduction

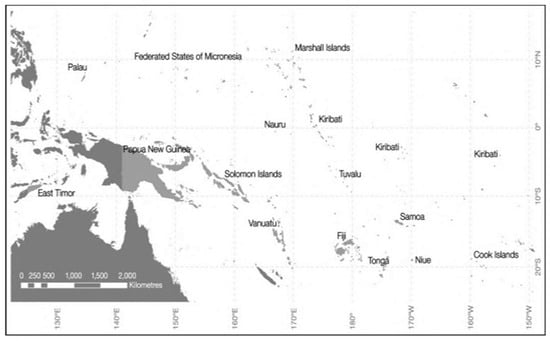

The Pacific Ocean, covering more than one-third of the Earth’s surface, represents one of the most dynamic and influential components of the global climate system. Its vast expanse stretches from the eastern coastlines of Asia and Australia to the western shores of the Americas, bounded to the south by the Antarctic continent. Within this immense marine territory lies a scattered array of island nations and territories (Table 1), each characterized by rich cultural heritage and significant biodiversity, yet also marked by acute environmental fragility. The distribution of these islands (Figure 1) is notably asymmetric: the southwestern Pacific hosts a dense concentration of landmasses, including Papua New Guinea, Fiji, Vanuatu, and New Caledonia, whereas the northeastern Pacific is largely devoid of emergent islands [1,2,3]. This geographic disparity has profound implications for regional climate interactions, biogeographic patterns, and human settlement.

Figure 1.

Distribution of major countries and territories (green) in the Pacific region [4].

Figure 1.

Distribution of major countries and territories (green) in the Pacific region [4].

Table 1.

Key island characteristics from the Pacific island database [5].

Table 1.

Key island characteristics from the Pacific island database [5].

| Country/Group of Islands | Number of Islands | Total Area of Islands (km2) | Average Island Area (km2) | Average Island Maximum Elevation (m) |

Primary Climate Hazards |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cook Islands | 15 | 297 | 20 | 73 | Tropical cyclones, sea-level rise, coastal erosion |

| East Pacific outliers | 24 | 8236 | 343 | 509 | Drought, sea-level rise, extreme heat |

| Micronesia | 127 | 799 | 6 | 45 | Typhoons, sea-level rise, saltwater intrusion |

| Fiji | 211 | 20,857 | 99 | 134 | Tropical cyclones, flooding, sea-level rise |

| French Polynesia | 126 | 3940 | 31 | 154 | Tropical cyclones, coral bleaching, coastal erosion |

| Guam | 1 | 588 | 588 | 400 | Typhoons, sea-level rise, extreme rainfall |

| Hawaii | 16 | 19,121 | 1195 | 896 | Sea-level rise, drought, extreme heat |

| Kiribati | 33 | 995 | 30 | 6 | Sea-level rise, saltwater intrusion, storm surges |

| Marshall Islands | 34 | 286 | 8 | 3 | Sea-level rise, typhoons, freshwater scarcity |

| Nauru | 1 | 23 | 23 | 71 | Sea-level rise, drought, coastal erosion |

| New Caledonia | 29 | 21,613 | 745 | 121 | Tropical cyclones, drought, coral bleaching |

| Niue | 1 | 298 | 298 | 60 | Tropical cyclones, sea-level rise, coastal erosion |

| Mariana Islands | 16 | 537 | 34 | 444 | Typhoons, sea-level rise, extreme heat |

| Palau | 33 | 495 | 15 | 58 | Typhoons, sea-level rise, coral bleaching |

| Papua New Guinea | 439 | 67,757 | 154 | 134 | Landslides, flooding, sea-level rise, tropical cyclones |

| Pitcairn Islands | 4 | 54 | 13 | 97 | Sea-level rise, coastal erosion |

| Samoa | 7 | 3046 | 435 | 504 | Tropical cyclones, flooding, sea-level rise |

| Solomon Islands | 413 | 29,672 | 72 | 88 | Tropical cyclones, sea-level rise, coastal flooding |

| Tokelau | 3 | 16 | 5 | 5 | Sea-level rise, tropical cyclones, freshwater scarcity |

| Tonga | 124 | 847 | 7 | 56 | Tropical cyclones, sea-level rise, coastal erosion |

| Tuvalu | 10 | 44 | 4 | 4 | Sea-level rise, saltwater intrusion, storm surges |

| US-administered islands | 8 | 37 | 5 | 5 | Sea-level rise, tropical cyclones, coral bleaching |

| Vanuatu | 81 | 13,526 | 167 | 330 | Tropical cyclones, volcanic hazards, sea-level rise |

| Wallis and Futuna | 14 | 190 | 14 | 94 | Tropical cyclones, sea-level rise, coastal erosion |

| Total | 1779 | 193,713 | 169 | 190 |

Pacific Island nations, despite their modest contributions to global greenhouse gas emissions, are disproportionately vulnerable to the impacts of climate variability and change. This susceptibility stems from a confluence of factors: geographic remoteness, which complicates disaster response and economic integration; small land areas with high coastline-to-land ratios, increasing exposure to sea-level rise and storm surges; limited economic diversification and adaptive capacity; and dense coastal populations reliant on climate-sensitive sectors such as fisheries, tourism, and subsistence agriculture [4,5,6]. These vulnerabilities are exacerbated by the region’s exposure to recurrent natural hazards, most notably tropical cyclones, which represent the single most destructive climate-related threat to lives, infrastructure, and economic stability across the Pacific.

The climate of the South Pacific is governed by a complex hierarchy of atmospheric and oceanic processes operating across spatial and temporal scales. At the heart of this system lies the South Pacific Convergence Zone (SPCZ), a semi-permanent band of deep convection and heavy rainfall that diagonally spans the basin from the Solomon Islands to French Polynesia. The position and intensity of the SPCZ fluctuate in response to several dominant modes of climate variability, most prominently the El Niño–Southern Oscillation (ENSO) on interannual timescales, and the Interdecadal Pacific Oscillation (IPO) on decadal scales. These fluctuations, in turn, regulate seasonal rainfall distribution, tropical cyclone genesis regions, sea surface temperature anomalies, and oceanic circulation patterns [7,8,9,10].

In recent decades, anthropogenic climate change has emerged as a significant transformative force, superimposing long-term trends upon these natural oscillations. Observed changes include rising surface air and sea temperatures, shifting rainfall regimes, increasing frequency of extreme heat events, accelerating sea-level rise, and emerging evidence of changes in tropical cyclone characteristics [11,12,13]. Disentangling the relative contributions of natural variability and human-induced change to observed trends remains a central challenge in Pacific climate science, particularly for high-impact events such as tropical cyclones, where data records are often short and inhomogeneous.

This systematic review aims to synthesize current understanding of the key determinants of climate variability in the South Pacific, with particular emphasis on their combined influences on tropical cyclones. This work provides a novel, integrated synthesis that explicitly links multi-scale climate drivers—from intraseasonal to decadal timescales—to tropical cyclone impacts, while systematically assessing the compounding role of anthropogenic change, a perspective not comprehensively addressed in previous regional reviews. The review is structured as follows: Section 2 outlines the principal features of the Pacific climate system, including the SPCZ and the major modes of variability from interannual to decadal timescales. Section 3 assesses observed and projected anthropogenic climate change signals across the region. Section 4 provides an in-depth analysis of the factors governing tropical cyclone variability, synthesizing research on the roles of ENSO, IPO, Madden–Julian Oscillation (MJO), Southern Annular Mode (SAM), and anthropogenic warming. Finally, Section 5 presents conclusions and identifies critical research gaps and future directions. Through this comprehensive synthesis, the review seeks to inform climate risk assessment, adaptation planning, and future scientific inquiry across the vulnerable South Pacific region.

2. Methods

This systematic review was conducted in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA 2020) guidelines. The review protocol was registered in the Open Science Framework (OSF) registry (https://osf.io/, accessed on 26 January 2026).

2.1. Eligibility Criteria

Studies were included if they:

- Focused on the South Pacific region, including island nations and territories;

- Addressed climate variability drivers (e.g., ENSO, IPO, SPCZ, MJO, SAM);

- Reported on tropical cyclone activity, rainfall, temperature, sea-level rise, or related impacts;

- Were published in English in peer-reviewed journals;

- Provided observational, modeling, or review-based evidence.

Exclusion criteria included:

- Studies outside the South Pacific basin;

- Non-climatic analyses (e.g., purely social or economic studies without climate linkage);

- Conference abstracts, reports, or non-peer-reviewed literature;

- Studies published before 1990, unless seminal works. Seminal works published before 1990 were included if they were foundational to the field, as determined by high citation counts and their recognition in subsequent review articles.

2.2. Information Sources and Search Strategy

A comprehensive literature search was performed using the following databases:

- Web of Science

- Scopus

- Google Scholar

- PubMed

The search strategy combined keywords and Boolean operators: (“South Pacific” OR “Pacific Islands”) AND (“climate variability” OR “ENSO” OR “IPO” OR “SPCZ”) AND (“tropical cyclone” OR “rainfall” OR “sea level rise”) AND (“climate change” OR “anthropogenic”).

The last search was conducted on 15 December 2024. Additional records were identified through manual screening of reference lists of relevant reviews.

2.3. Study Selection and Data Collection

Two independent reviewers (M.W. and A.Y.) screened titles and abstracts using the online tool Rayyan (https://www.rayyan.ai/, accessed on 7 January 2026). Rayyan’s AI functions were used only for initial duplicate removal; title/abstract screening and full-text review were performed independently by two reviewers. Full texts of potentially eligible studies were retrieved and assessed against the inclusion criteria. Discrepancies were resolved through discussion or consultation with a third reviewer when necessary. Data extraction was performed using a standardized form, capturing:

- Study characteristics (author, year, region, methodology);

- Key findings on climate drivers and impacts;

- Observed trends and projections.

2.4. Risk of Bias Assessment

Qualitative Appraisal of Study Limitations

Given the diverse nature of the included studies (observational, modeling, review), a formal risk-of-bias assessment was not conducted. Instead, we assessed study quality based on data source reliability, methodological transparency, and consistency with established climate science principles (Table 2).

Table 2.

Qualitative appraisal of study types included in the systematic review, highlighting common strengths and limitations.

2.5. Synthesis Methods

A narrative synthesis approach was adopted due to heterogeneity in study designs, variables, and outcomes. Findings were organized thematically around:

- Principal climate features (SPCZ, ENSO, IPO);

- Observed and projected anthropogenic changes;

- Determinants of tropical cyclone variability.

Results are presented in text, tables, and figures to facilitate comparison and highlight knowledge gaps.

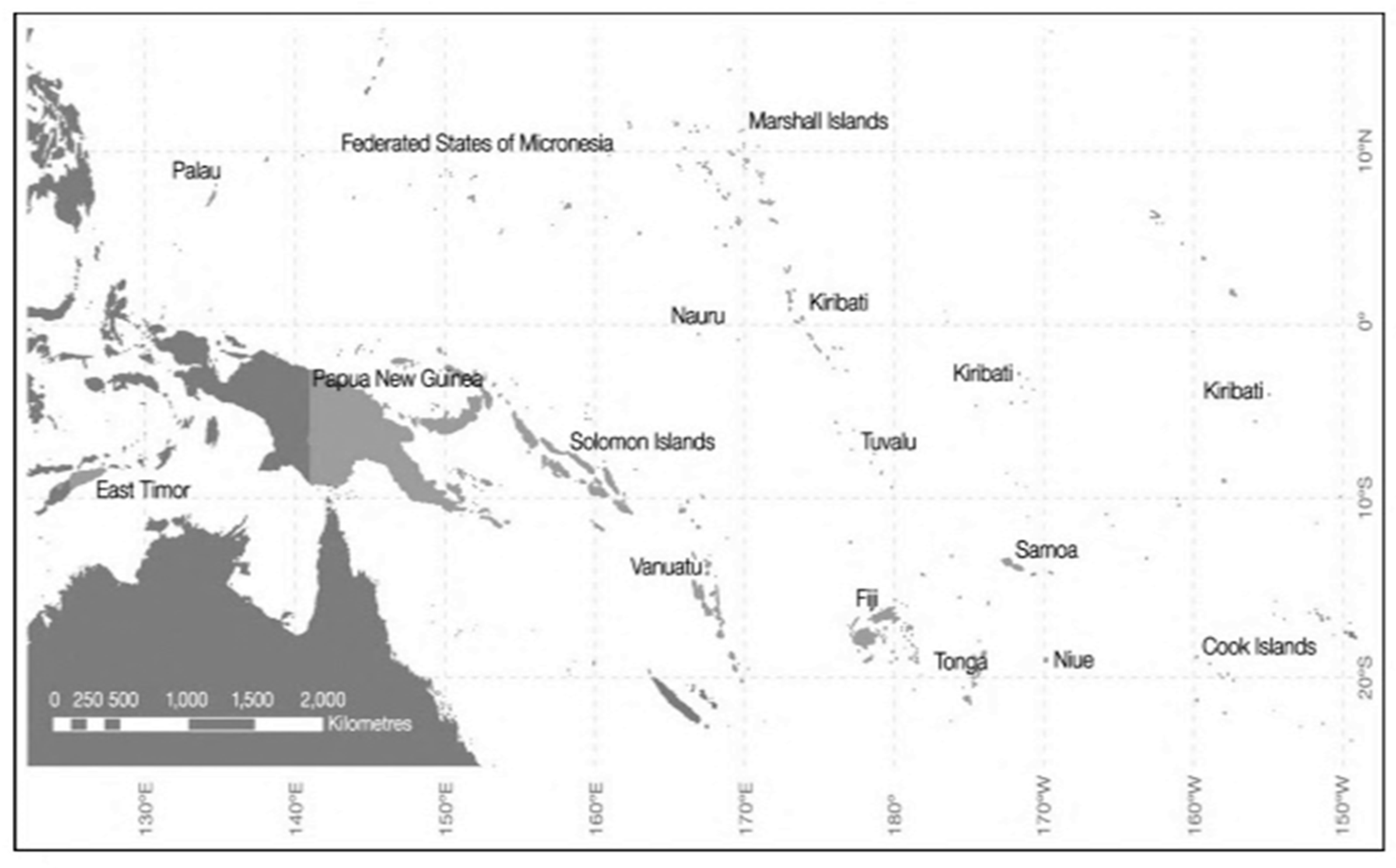

2.6. Study Selection Flow

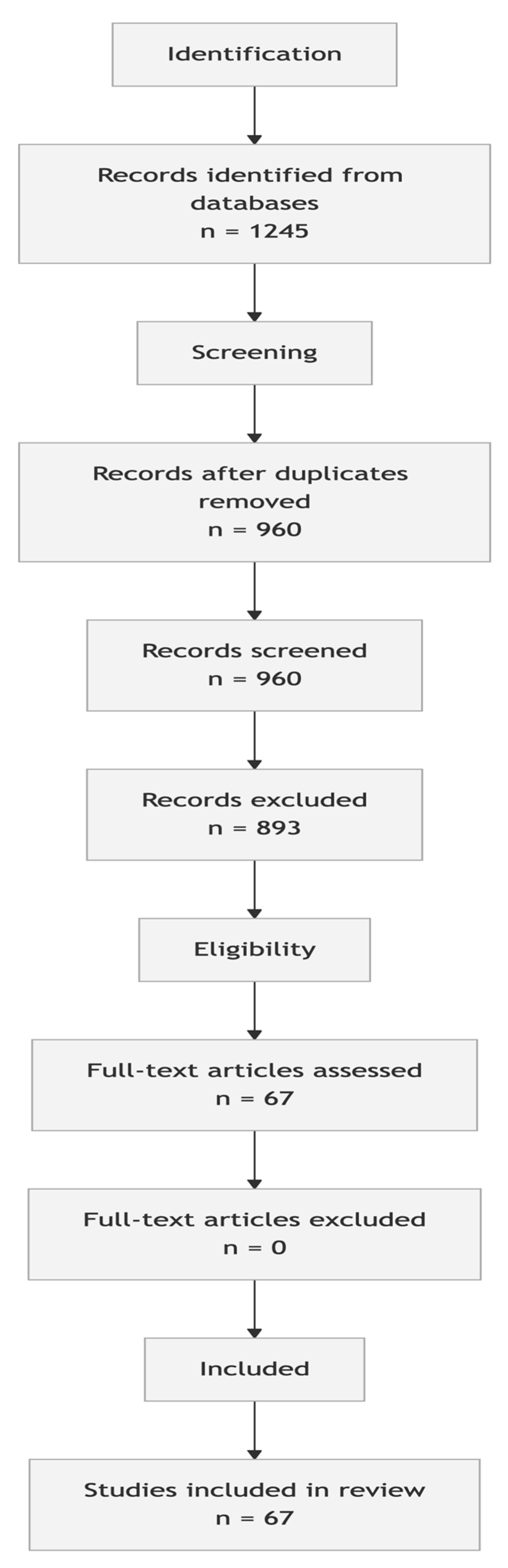

The study selection process is summarized in Figure 2, following PRISMA 2020 guidelines.

Figure 2.

PRISMA 2020 flow diagram of the study selection process.

3. Climate of the Pacific Region

3.1. Main Features of the Pacific Climate

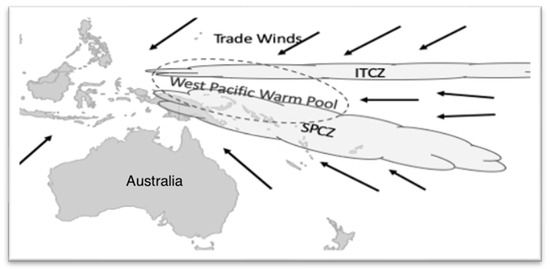

The climate of the South Pacific is fundamentally shaped by the interplay between large-scale oceanic circulations, atmospheric convection patterns, and regional topographic influences. A dominant and defining feature of this region is the SPCZ, a persistent band of intense convective activity that extends diagonally from the Solomon Islands (near the equator and 150° E) southeastward toward French Polynesia (around 30° S, 120° W). The SPCZ is not a static entity but a dynamic zone characterized by deep atmospheric convection, high cloud cover, and heavy precipitation, often exceeding 5–10 mm/day on a climatological basis. It forms along the confluence of moist, easterly trade winds emanating from the South Pacific subtropical high-pressure system and southerly flows originating from higher latitudes. This convergence results in sustained uplift, condensation, and latent heat release, which further fuels convective organization and cloud development [7,8].

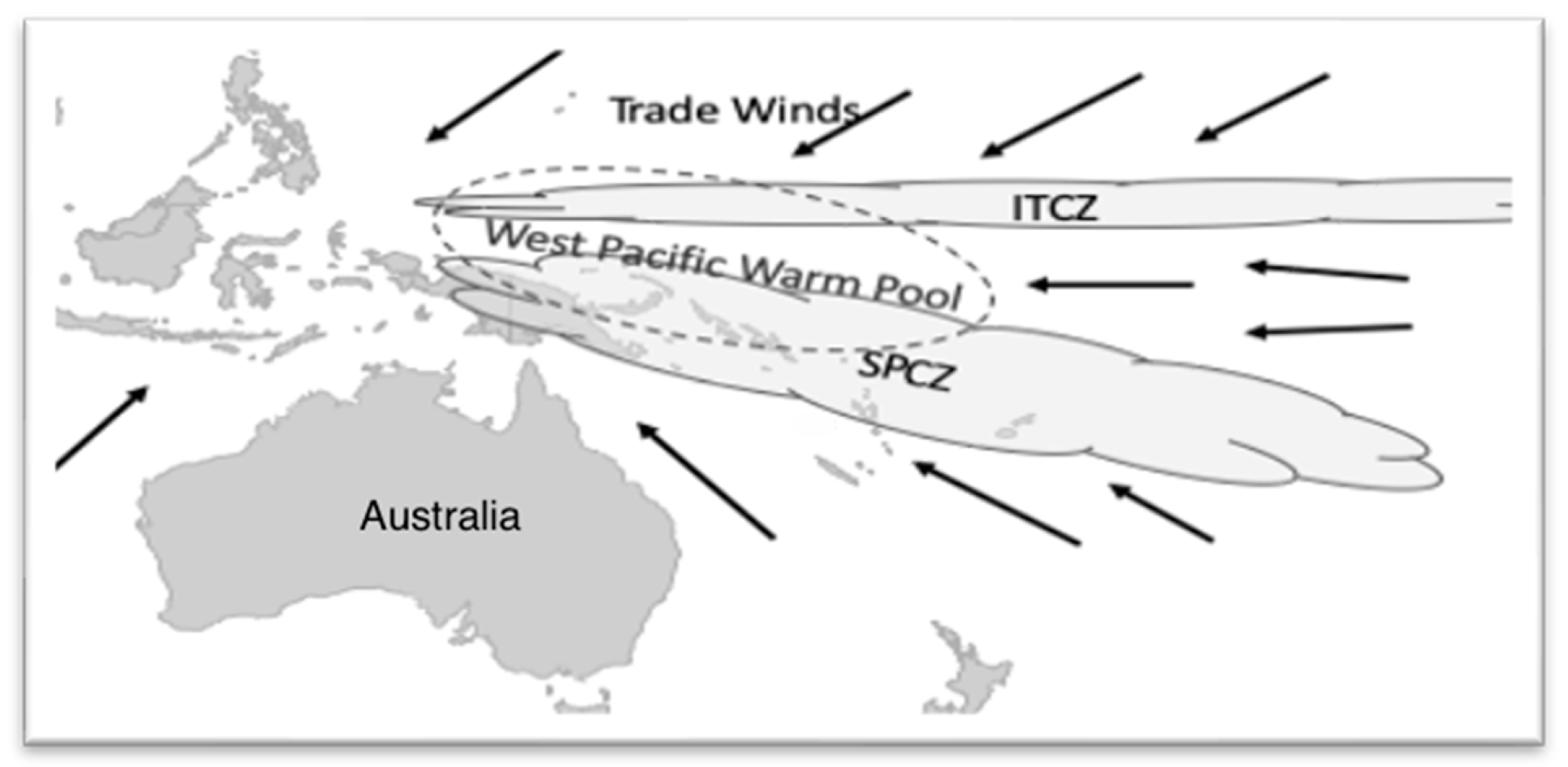

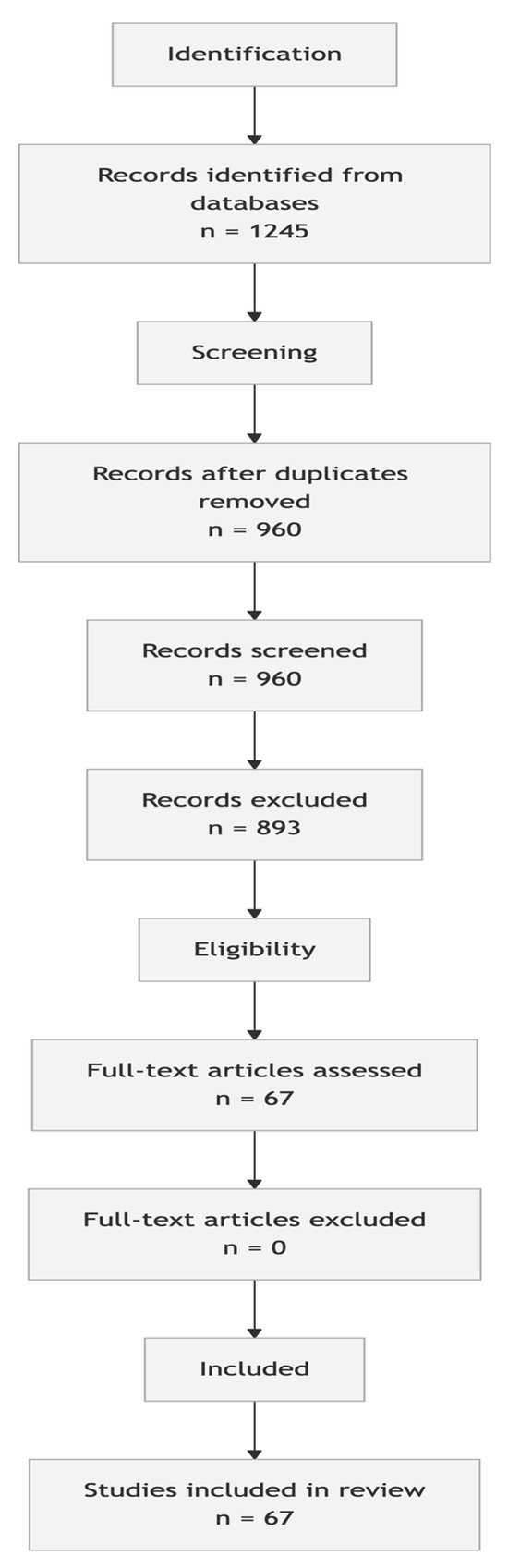

The SPCZ exhibits strong seasonal migration, typically reaching its southernmost and most active position during the austral summer (December–February), and retreating northward during the winter months. Its longitudinal orientation is influenced by both oceanic and atmospheric factors: in the western Pacific, the SPCZ overlaps with the West Pacific Warm Pool, an area of perennial sea surface temperatures (SST) above 28 °C that provides ample moisture and energy for convection. In contrast, the southeastern limb of the SPCZ interacts with mid-latitude frontal systems and subtropical jets, leading to a more diffuse and variable structure [9]. The SPCZ’s location (Figure 3) and intensity are critical determinants of rainfall distribution across the region; islands situated beneath or near the SPCZ experience abundant rainfall, while those to the southwest (such as New Caledonia) or northeast (such as parts of French Polynesia) may experience more pronounced dry seasons.

Figure 3.

Schematic of the South Pacific Convergence Zone, showing mean position and seasonal migration [9].

To quantitatively monitor SPCZ variability, several indices have been developed. Among the most widely used is the SPCZ Index (SPCZI) proposed by Salinger et al. [11], which is derived from normalized rainfall anomalies at stations symmetrically positioned relative to the mean SPCZ axis, typically Apia (Samoa) and Suva (Fiji). A positive SPCZI indicates a northeastward displacement and/or intensification of the convergence zone, often associated with El Niño conditions, while a negative index reflects a southwestward shift typical of La Niña phases. This index has proven valuable for diagnosing interannual to decadal variations in SPCZ behavior and for assessing linkages with large-scale climate drivers.

3.2. Drivers of Interannual to Decadal Climate Variability

3.2.1. El Niño-Southern Oscillation

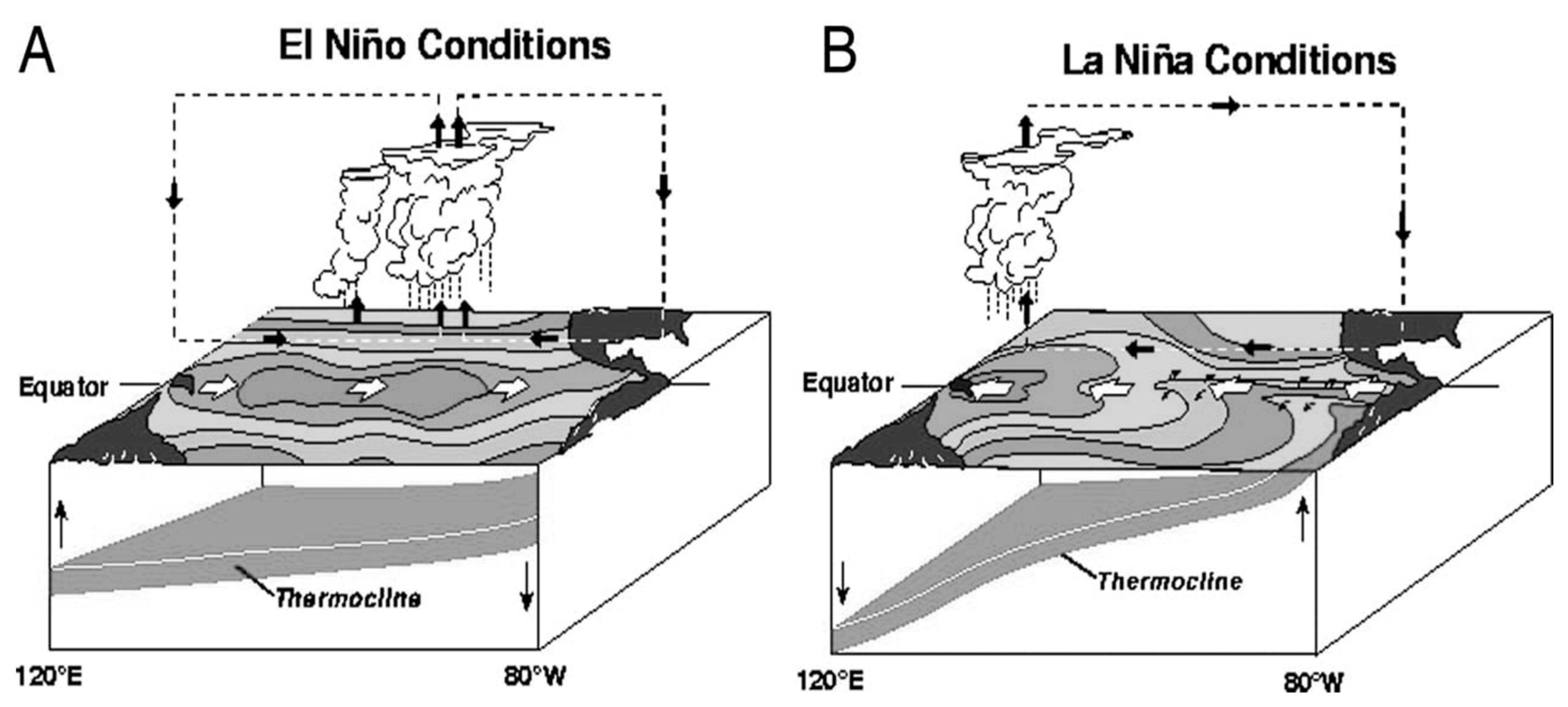

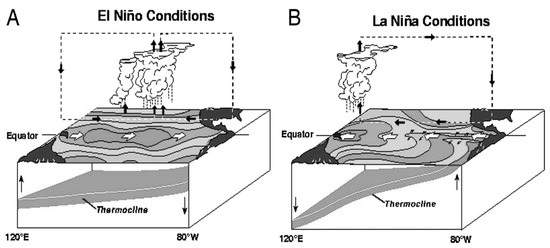

The El Niño–Southern Oscillation is the most prominent mode of interannual climate variability on Earth, with particularly strong expression in the Pacific Basin (Figure 4). ENSO is a coupled ocean-atmosphere phenomenon characterized by quasi-periodic fluctuations between two extreme phases: El Niño (warm phase) and La Niña (cool phase), separated by neutral conditions. During El Niño events, the usual east-to-west trade winds weaken, leading to a reduction in upwelling of cold water along the coast of South America and a pronounced warming of SST in the central and eastern equatorial Pacific. This warming alters atmospheric circulation patterns, causing the uplift and convective core of the SPCZ to shift northeastward. Consequently, regions such as French Polynesia, the Cook Islands, and the central Pacific experience enhanced rainfall and increased tropical cyclone activity, while areas to the west (including Papua New Guinea, Solomon Islands, and parts of Fiji) may experience drought conditions [11,12].

Figure 4.

Ocean-atmosphere interactions during (A) El Niño and (B) La Niña phases, showing shifts in convection, SST, and wind patterns [12].

Conversely, during La Niña events, strengthened trade winds enhance upwelling in the eastern Pacific and drive warmer water westward, leading to cooler-than-average SSTs in the central/eastern Pacific and warmer anomalies in the west. The SPCZ shifts southwestward, bringing heightened rainfall to regions such as Fiji, New Caledonia, and northeastern Australia, while suppressing precipitation in the central Pacific. The atmospheric component of ENSO, known as the Southern Oscillation, is measured by the sea-level pressure (SLP) difference between Tahiti (central Pacific) and Darwin (Australia). This Southern Oscillation Index (SOI) is strongly correlated with SST anomalies and provides a robust indicator of ENSO phase and strength [12].

ENSO’s impacts extend beyond rainfall to affect a wide range of environmental variables across the South Pacific. These include: modulation of tropical cyclone genesis locations and tracks (discussed in Section 4), sea-level anomalies (with higher sea levels in the western Pacific during La Niña due to wind-driven water accumulation), ocean nutrient availability and fisheries productivity, coral bleaching risk, and even the frequency of extreme temperature events. The typical periodicity of ENSO is 2–7 years, though its amplitude and spatial patterns can vary significantly between events, leading to distinct “flavors” such as Eastern Pacific (canonical) vs. Central Pacific (Modoki) El Niño events, each with somewhat different regional teleconnections [13,14,15].

3.2.2. Pacific Decadal Oscillation and Interdecadal Pacific Oscillation

While ENSO dominates interannual variability, the Pacific climate system also exhibits significant variability on decadal to multi-decadal timescales. Two closely related indices are commonly used to describe this low-frequency variability: the PDO. The PDO is defined as the leading empirical orthogonal function (EOF) of monthly sea surface temperature (SST) anomalies in the North Pacific Ocean (poleward of 20° N) [16]. The PDO index, derived from this pattern, exhibits phases that persist for 20–30 years. During its positive phase, cooler-than-average SSTs prevail in the central and western North Pacific, while warmer-than-average conditions occur along the Pacific coast of North America. The negative phase shows the opposite pattern. Although the PDO is primarily a North Pacific phenomenon, it shares spectral characteristics with ENSO and can modulate the frequency and intensity of El Niño and La Niña events. Its teleconnections influence precipitation and temperature patterns across the Americas and can indirectly affect the South Pacific climate by altering the background state of the Pacific basin, thereby modifying the expression of ENSO and the position of the SPCZ on decadal timescales. The IPO, which captures a pan-Pacific pattern of SST anomalies that resembles ENSO but evolves over 20–30 year periods [17]. The IPO is often described as a tripolar pattern, with SST anomalies of one sign in the central equatorial Pacific and the opposite sign in the northwest and southwest Pacific. A positive IPO phase is characterized by warm SST anomalies in the tropical central Pacific and cool anomalies in the extra-tropical Pacific, while the opposite pattern holds during negative IPO phases.

The IPO/PDO modulates the background state upon which ENSO operates, effectively altering the frequency, intensity, and teleconnections of ENSO events. For example, during positive IPO phases (such as the period from the late 1970s to the late 1990s), El Niño events tend to be more frequent, and their impacts on South Pacific rainfall and cyclone activity are often enhanced. Conversely, during negative IPO phases (such as the early 2000s onward), La Niña events become more common, and their regional expressions may be amplified [18,19]. This modulation occurs because the IPO alters mean SST gradients, trade wind strength, and the background positioning of the SPCZ, thereby changing the base state from which interannual anomalies develop.

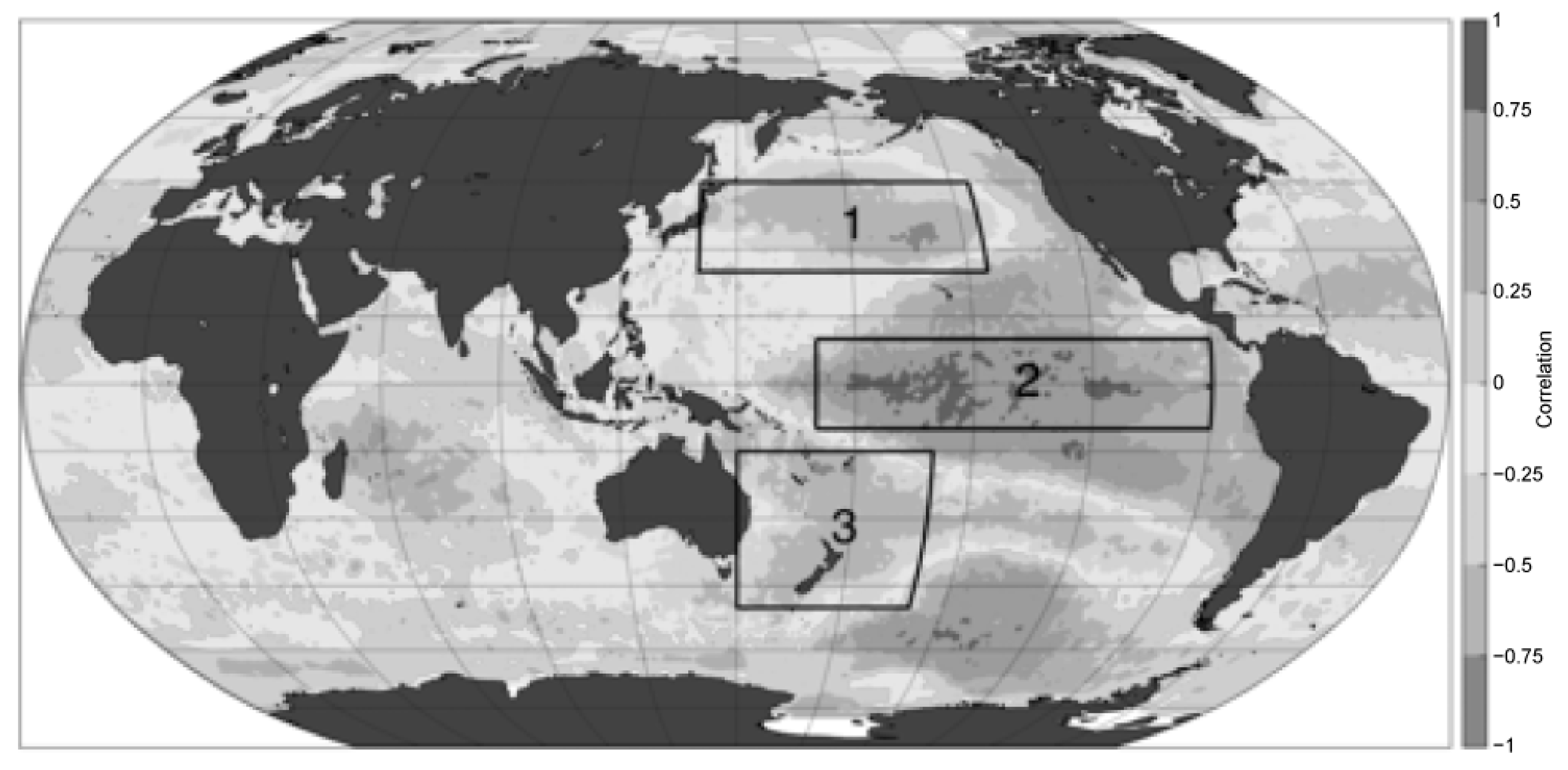

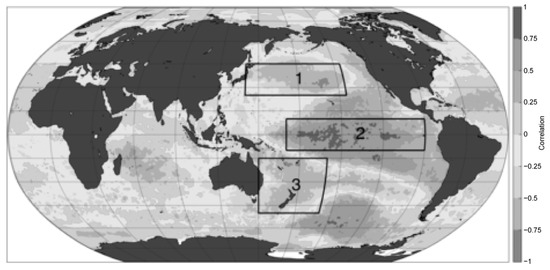

Quantifying IPO variability is commonly achieved using the IPO Tripole Index (TPI), developed by Henley et al. [17]. The TPI is calculated as the difference between the average SST anomaly in the central equatorial Pacific region and the average of SST anomalies in the Northwest and Southwest Pacific regions (Figure 5). This index effectively captures the decadal-scale swings in Pacific climate and has been correlated with long-term variations in rainfall, temperature, and tropical cyclone activity across the South Pacific [20,21]. Understanding IPO variability is crucial for interpreting observed trends and for improving decadal climate predictions, as the IPO’s slow evolution may offer some predictive capacity beyond typical seasonal forecasting horizons.

Figure 5.

Spatial pattern associated with the IPO Tripole Index (TPI) and its temporal evolution since 1900, showing distinct decadal phases [20]. In Figure, 1: NW Pacific, 2: Central Equatorial Pacific, 3: SW Pacific.

4. Observed and Projected Anthropogenic Climate Change Signals

4.1. Historical Changes in Temperature and Rainfall

The South Pacific has not been immune to global warming trends. Instrumental records indicate a clear increase in surface air temperatures across most of the region over the past century. Analysis of data from meteorological stations maintained by national services and regional bodies reveals warming rates ranging from approximately +0.08 °C to +0.20 °C per decade since the early 20th century, with stronger warming trends observed in recent decades [22]. This warming is evident in both maximum and minimum temperatures and affects both the wet (November–April) and dry (May–October) seasons, though some seasonal and spatial heterogeneity exists. For instance, nighttime minimum temperatures have generally increased at a faster rate than daytime maximums in some island groups, potentially affecting ecosystem functioning and human comfort.

The warming trend is consistent with the increase in global mean temperature attributed to rising concentrations of greenhouse gases, primarily carbon dioxide (CO2), methane (CH4), and nitrous oxide (N2O). Detection and attribution studies that separate natural variability (from ENSO, IPO, and volcanic eruptions) from anthropogenic forcing have concluded that the observed warming in the Pacific is extremely unlikely to have occurred without human influence [23,24]. Moreover, paleoclimate reconstructions using proxies such as coral geochemistry, tree rings, and ice cores indicate that current temperatures in the region are likely the warmest experienced in at least the past several centuries, and possibly the past millennium [25].

In contrast to temperature, identifying coherent long-term trends in rainfall across the South Pacific is more challenging due to the region’s high natural variability, sparse observational networks, and strong localized influences such as topography and island size. However, several studies have reported shifts in precipitation patterns over recent decades, often linked to changes in the mean position and intensity of the SPCZ as modulated by ENSO and IPO [26,27]. For example, there is evidence of a slight eastward extension of the SPCZ during the late 20th century, which may have contributed to drying trends in parts of the western Pacific (e.g., southern Papua New Guinea) and wetting trends in the central Pacific (e.g., Kiribati). Rainfall extremes have also shown changes, with some locations experiencing an increase in the frequency of heavy precipitation events, consistent with the thermodynamic expectation of a warmer atmosphere holding more moisture [28].

The robustness of these observed rainfall trends varies depending on the data source. Analyses based solely on sparse station networks are often limited in spatial representativeness, particularly over ocean areas and remote islands. Reanalysis products and satellite-based precipitation estimates (e.g., GPCP, TRMM, GPM) provide broader coverage and have been instrumental in identifying large-scale patterns, such as the eastward extension of the SPCZ. However, these products also have uncertainties related to algorithmic assumptions, temporal inhomogeneities, and difficulty in capturing orographic and convective-scale rainfall. Multi-source syntheses that integrate ground observations, reanalysis, and satellite data generally provide higher confidence in identifying coherent regional trends, such as the increased frequency of extreme rainfall events, while highlighting areas where signals remain weak or contradictory due to natural variability and data limitations.

Projections of future SPCZ behavior under anthropogenic warming show consistent directional changes between successive climate model intercomparisons (CMIP5 and CMIP6), but with refined spatial patterns and magnitudes. CMIP6 models generally project a more pronounced eastward and poleward shift of the SPCZ under high-emission scenarios (e.g., SSP5-8.5) compared to CMIP5 under RCP8.5. This shift is associated with a weakening of the Walker Circulation and an expansion of the western Pacific warm pool. The resulting changes in convergence zones and atmospheric steering flow are projected to alter tropical cyclone genesis regions—potentially reducing activity in the western South Pacific (e.g., Coral Sea) while increasing it in the central and eastern basins—and modify rainfall distributions, with implications for flood and drought risks across island nations.

4.2. Sea-Level Rise and Coastal Impacts

Sea-level rise represents one of the most pressing climate-related threats to Pacific Island nations, many of which consist of low-lying atolls and coastal communities. Global mean sea level has risen by approximately 0.2 m since 1900, with the rate of rise accelerating in recent decades due to thermal expansion of seawater and increased meltwater from glaciers and ice sheets [18]. In the Pacific, regional sea-level trends are not uniform due to the influence of natural variability, ocean circulation changes, and vertical land motion (subsidence or uplift). Subsidence is observed in parts of the Solomon Islands and Vanuatu due to tectonic activity, while uplift occurs in areas like Tonga and Fiji, affecting relative sea-level rise rates. For instance, during La Niña events, strengthened trade winds push water westward, leading to temporarily higher sea levels in the western Pacific and lower levels in the east—a pattern that can mask or accentuate the long-term trend on interannual timescales [11].

Despite this variability, tide gauge records and satellite altimetry data confirm that sea levels are rising across most of the South Pacific, with current rates generally consistent with or slightly exceeding the global average. This rise exacerbates a range of coastal hazards, including storm surge inundation, coastal erosion, saltwater intrusion into freshwater lenses, and increased flooding during high tides and extreme weather events. Notably, nations such as Kiribati, Tuvalu, and the Marshall Islands have average maximum elevations of only 3–6 m (Table 1), rendering them acutely vulnerable to even moderate sea level rise, even modest sea-level rise poses existential risks to habitability, freshwater security, and infrastructure [29,30].

In the context of future projections, the Shared Socioeconomic Pathways (SSPs) from the IPCC Sixth Assessment Report (AR6) provide updated and more nuanced scenarios. Under intermediate mitigation scenarios (e.g., SSP2-4.5), global mean sea level is projected to rise by 0.4–0.7 m by 2100, relative to the 1995–2014 baseline. High-emissions scenarios (SSP5-8.5) project a rise of 0.6–1.1 m by 2100, with the potential for significantly higher increases if ice-sheet instability thresholds are crossed [31]. These projections also indicate greater regional variability for the Pacific, with some areas experiencing rates up to 20% above the global mean due to oceanographic and gravitational effects.

Future projections indicate that sea-level rise will continue and likely accelerate through the 21st century. Under intermediate emissions scenarios (e.g., RCP4.5), global mean sea level is projected to rise by 0.4–0.7 m by 2100, while high-emissions scenarios (RCP8.5) could see rises of 0.6–1.1 m [32]. These projections do not include potential contributions from rapid ice-sheet collapse, which could add several tens of centimeters additional rise. For the Pacific, regional variations will persist, but the overall trend is unequivocally upward, necessitating urgent adaptation measures such as coastal protection, planned relocation, and enhanced freshwater management.

4.3. Impacts on Ecosystems and Human Systems

Anthropogenic climate change is already affecting both natural and human systems across the South Pacific. Future warming projections for the South Pacific are closely aligned with global trends under the SSP framework. Under SSP2-4.5, regional mean surface temperatures are projected to increase by 1.5–2.5 °C by mid-century (2041–2060) and by 2.0–3.5 °C by 2100, relative to 1850–1900. Under SSP5-8.5, warming could reach 2.0–3.5 °C by mid-century and 3.5–6.0 °C by 2100 [32]. These increases are expected to intensify heatwaves, alter precipitation regimes, and further stress both terrestrial and marine ecosystems, with cascading effects on agriculture, health, and livelihoods. Coral reef ecosystems, which provide critical habitat for marine biodiversity and support fisheries and tourism, are under severe stress from repeated mass bleaching events driven by prolonged periods of elevated SSTs. Bleaching episodes have become more frequent and severe in recent decades, with major events recorded in 1998, 2010, 2015–2017, and 2020, each causing widespread coral mortality and ecosystem degradation [33,34,35].

Terrestrial ecosystems are also undergoing changes, including shifts in species distributions, phenology, and community composition. Some plant and animal species are migrating to higher elevations or latitudes in response to warming, while others face increased extinction risk due to habitat loss, invasive species, and extreme events. Changes in rainfall patterns affect agricultural productivity, particularly for staple crops like taro, yam, and cassava, which rely on consistent water availability. Combined with increased temperature stress and pest outbreaks, these changes threaten local food security and livelihoods [36].

Human health is increasingly impacted through heat-related illnesses, changing patterns of vector-borne diseases (e.g., dengue fever), and health risks associated with extreme weather events and water insecurity. Moreover, the economic costs of climate-related disasters are substantial and rising. Tropical cyclones, floods, and droughts disrupt infrastructure, reduce tourism revenue, damage crops, and strain government budgets. For small island economies, the repeated need for post-disaster recovery can hinder long-term development and perpetuate cycles of poverty and vulnerability [34].

4.4. Interactions and Compound Events

The emerging impacts of anthropogenic climate change in the South Pacific do not occur in isolation but interact dynamically with natural climate variability, leading to compound events that can amplify risks. For instance, during positive phases of the IPO, which favor more frequent and intense El Niño events, the superimposed anthropogenic warming can exacerbate sea surface temperature anomalies. This combination may intensify marine heatwaves, prolong coral bleaching episodes, and enhance the eastward shift of tropical cyclone activity in the central Pacific. Conversely, during negative IPO phases (La Niña-like background), strengthened trade winds combined with anthropogenic sea-level rise can lead to more pronounced sea-level extremes in the western Pacific, increasing the frequency and severity of coastal inundation during storm surges and king tides.

Compound events—where multiple climate drivers or hazards coincide—pose particularly severe challenges. Examples include tropical cyclones occurring during periods of already elevated sea levels (due to seasonal variability, ENSO, or long-term rise), which dramatically increase storm surge impacts. Similarly, droughts coinciding with heatwaves can severely stress water resources and agricultural systems, while heavy rainfall events on drought-affected soils can trigger landslides and flash flooding. These interactions are not merely additive; they can create non-linear impacts that exceed the adaptive capacity of communities and ecosystems.

Understanding and projecting these compound risks requires integrated modeling approaches that capture both natural variability and anthropogenic trends across multiple timescales. Improved early warning systems that consider both climatic and non-climatic factors are essential for enhancing preparedness and resilience across the vulnerable island nations of the South Pacific.

5. Determinants of Tropical Cyclone Variability in the Pacific

5.1. ENSO Modulation of Cyclone Activity

Tropical cyclones (TCs) are among the most destructive natural phenomena in the South Pacific, and their interannual variability is strongly modulated by ENSO. During El Niño events, the region of maximum TC genesis shifts eastward and poleward, with increased activity observed east of the dateline, particularly around the Cook Islands, French Polynesia, and the Northern Fiji Islands. The warm SST anomalies and altered wind patterns associated with El Niño create a more favorable environment for cyclogenesis in these central Pacific areas. Conversely, TC activity tends to be suppressed in the Coral Sea and near Australia during El Niño phases. Storm tracks also change, with cyclones more likely to follow recurving paths toward the southeast, potentially affecting islands that are less frequently impacted under neutral or La Niña conditions [36,37,38,39].

During La Niña events, the pattern largely reverses: TC genesis concentration shifts westward and equatorward, with enhanced activity in the Coral Sea, around Vanuatu and New Caledonia, and off the northeast coast of Australia. The western South Pacific, including the Solomon Islands and Papua New Guinea, also tends to experience more frequent cyclone formations. Tracks during La Niña often exhibit a more zonal (westward) motion, with some systems penetrating into the Australian region or curving southwestward. Intensity characteristics may also differ, with some studies suggesting that La Niña events support longer-lived storms that maintain intensity further into higher latitudes, occasionally reaching the Tasman Sea near New Zealand [40,41].

The physical mechanisms linking ENSO to TC variability involve changes in several environmental factors: vertical wind shear (which is often reduced in genesis regions during favorable ENSO phases), low-level relative vorticity, mid-tropospheric humidity, and oceanic heat content. ENSO-driven shifts in the SPCZ and the monsoon trough also play key roles in organizing large-scale convergence zones that serve as foci for cyclone development.

5.2. Influence of Decadal-Scale Oscillations (IPO/PDO)

Beyond interannual ENSO effects, decadal-scale climate variability imprinted by the IPO/PDO can modulate the background frequency and preferred regions of TC activity over multi-year to multi-decadal periods. For example, during positive IPO phases (like the 1980s–1990s), the central and eastern South Pacific often experiences increased TC activity, consistent with a more El Niño-like mean state. During negative IPO phases (such as the 1950s–1970s and the post-2000 period), TC activity tends to become more concentrated in the western South Pacific and Coral Sea, aligned with a La Niña-like background [42,43].

These decadal modulations can have important implications for risk assessment and adaptation planning. For instance, a multi-decadal shift into a negative IPO phase could mean that islands in the eastern South Pacific experience a temporary reprieve from frequent cyclone impacts, while western island groups face heightened exposure. However, such decadal predictions remain uncertain, and more research is needed to understand the dynamical interactions between IPO, ENSO diversity, and TC behavior.

5.3. Intraseasonal and High-Frequency Drivers: MJO and SAM

On sub-seasonal timescales, the MJO—a large-scale eastward-propagating pattern of tropical convection with a period of 30–60 days—exerts a strong influence on TC activity in the South Pacific. When the convectively active phase of the MJO moves into the Pacific basin, it enhances large-scale ascent, reduces vertical wind shear, and increases low-level vorticity, thereby creating windows of heightened TC genesis likelihood. Conversely, the suppressed phase of the MJO inhibits convection and reduces cyclone formation potential. The MJO’s influence interacts with ENSO; for example, the enhancement of TC activity by the MJO appears more pronounced during El Niño events than during La Niña events, possibly due to more favorable background conditions [44,45].

The SAM, which describes the north–south movement of the Southern Hemisphere’s mid-latitude westerly wind belt, also affects TC behavior, particularly in the higher latitudes of the South Pacific. A positive SAM (with contracted westerlies) is associated with increased blocking high pressure over southern Australia and the Tasman Sea, which can steer TCs on more poleward tracks and facilitate extratropical transition near New Zealand. Studies have shown that SAM and ENSO can act in tandem: during La Niña and positive SAM combinations, the likelihood of TCs affecting New Zealand increases significantly [46].

When a tropical cyclone undergoes extratropical transition, it often evolves into a hybrid system with an expanded wind field, prolonged rainfall duration, and the potential for intense mid-latitude-like frontal precipitation. These post-transition systems can affect larger geographic areas than their tropical counterparts and may produce severe weather—including gale-force winds, heavy rainfall, and coastal flooding—far from the original cyclone track. The combined influence of SAM and background atmospheric flow patterns can modulate the location, frequency, and impacts of these transitioning systems, posing distinct forecasting and risk management challenges for regions such as New Zealand, southeastern Australia, and the southern island groups of the South Pacific.

5.4. Anthropogenic Climate Change and Tropical Cyclones

Detecting and attributing long-term trends in tropical cyclone activity in the South Pacific is complicated by short and inhomogeneous historical records, strong natural variability, and observational uncertainties. Historical inhomogeneity arises largely from observational shifts, such as the pre-satellite era (before the 1970s), relying on ship reports, which undercounted weaker and remote cyclones.

Furthermore, discrepancies between observed trends and model projections arise from several key factors. First, the strong modulation by natural climate modes (ENSO, IPO, SAM) can obscure anthropogenic signals in relatively short observational records. Second, most global climate models operate at coarse resolutions (~50–100 km) that cannot explicitly resolve tropical cyclone genesis and intensification processes, relying instead on parameterization schemes that vary substantially between models. Higher-resolution models and downscaling approaches show improved representation of TC statistics but are not yet widely incorporated into multi-model ensembles used for detection and attribution studies. Finally, uncertainties in historical forcing (e.g., aerosols) and internal climate variability contribute to divergent projections, particularly for regional TC frequency. These factors collectively explain why confident detection of anthropogenic trends in South Pacific TC activity remains challenging, despite consistent thermodynamic expectations from theory and models.

Nevertheless, climate model projections and theoretical considerations provide insights into expected changes under continued global warming. Thermodynamic theory suggests that a warmer atmosphere and ocean will increase the potential intensity of TCs, as higher SSTs provide more energy for development, and increased atmospheric moisture content can fuel heavier rainfall. Some studies also suggest a possible poleward migration of TC tracks as the tropics expand and the regions suitable for genesis shift [47,48].

However, dynamic changes—such as alterations in vertical wind shear, atmospheric stability, and large-scale circulation patterns—could offset some of these thermodynamic effects in certain basins. For the South Pacific, current projections indicate a possible reduction in overall TC frequency but an increase in the proportion of intense storms (Category 4–5). Rainfall associated with TCs is projected to increase substantially due to higher atmospheric water vapor. These changes, if realized, would imply a shift toward less frequent but potentially more destructive cyclone events, with serious implications for disaster preparedness and infrastructure design [49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58].

Challenges remain in reconciling observed trends with model projections. Some analyses of historical TC data show no clear trend in frequency or intensity for the South Pacific basin as a whole, though regional variations exist. Improved data homogenization, longer records, and higher-resolution modeling are needed to reduce uncertainties and provide more confident outlooks for policymakers.

6. Conclusions and Future Research Directions

This systematic review has synthesized the current state of knowledge regarding the determinants of climate variability and change in the South Pacific, with a focused examination of tropical cyclone behavior. The climate of this region is governed by a complex hierarchy of processes, from the dominant interannual influence of ENSO to decadal modulations by the IPO/PDO, and intraseasonal variability driven by the MJO and SAM [59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67]. Superimposed upon these natural modes is the accelerating signal of anthropogenic climate change, manifested in rising temperatures, shifting rainfall patterns, sea-level rise, and evolving extremes.

The interplay between natural variability and human-induced change presents both a scientific challenge and a practical imperative for the vulnerable island nations of the South Pacific. Disentangling their relative contributions is essential for accurate attribution of observed trends, for improving seasonal to decadal predictions, and for generating reliable climate projections to inform adaptation. Tropical cyclones, as a key hazard, exemplify this complexity: while theory and models suggest an increase in peak intensity and associated rainfall, historical records do not yet show unambiguous trends, underscoring the need for continued monitoring and research.

Several critical knowledge gaps (Table 3) and priority research areas emerge from this synthesis:

Table 3.

Summary of key knowledge gaps and recommended research actions for the South Pacific region.

- Enhanced Observational Networks and Data Homogenization: There is a pressing need to maintain and expand in situ and remote sensing observations across the Pacific, particularly for oceanic variables, precipitation, and tropical cyclones. Improved historical data reanalysis and homogenization efforts are essential for robust trend detection and model validation.

- Understanding ENSO Diversity and Teleconnections: Further research is needed on the distinct impacts of different ENSO “flavors” (e.g., Eastern Pacific vs. Central Pacific events) on South Pacific climate extremes, including TC activity, rainfall anomalies, and marine heatwaves.

- Decadal Predictability and Projections: Improving the representation of IPO/PDO and their interactions with anthropogenic forcing in climate models is crucial for producing credible decadal-scale projections. Research should focus on mechanisms of decadal variability and potential predictability.

- High-Resolution Climate and Impact Modeling: Dynamical downscaling using regional climate models and convection-permitting simulations can provide more detailed projections of future changes in TC characteristics, extreme rainfall, and local-scale climate processes. Coupling these with hydrological, coastal, and ecosystem models will enable more integrated impact assessments.

- Integration of Indigenous Knowledge and Social Science: Effective adaptation requires collaboration between physical scientists, social scientists, and local communities. Research should increasingly incorporate indigenous ecological knowledge, assess socio-economic vulnerabilities, and evaluate the effectiveness of adaptation strategies. For example, Chand et al. [29] documented how communities in Fiji use cloud patterns and bird behavior to forecast cyclones—a practice that could enhance early warning systems and build community trust in scientific forecasts.

- Strengthening Climate Services and Communication: Translating scientific insights into actionable information for decision-makers, communities, and sectors (e.g., agriculture, water management, disaster risk reduction) is essential. This includes improving seasonal forecasts, early warning systems, and long-term scenario planning.

In conclusion, addressing these research priorities will not only advance scientific understanding but also directly support the resilience and sustainable development of South Pacific Island nations. As the climate continues to change, a concerted effort involving regional cooperation, capacity building, and targeted science will be vital to navigating the challenges ahead and safeguarding the future of this unique and vulnerable part of the world.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.Y.; methodology, M.W. and A.Y.; investigation, M.W.; resources, M.W. and A.Y.; writing—original draft preparation, M.W.; writing—review and editing, M.W. and A.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Md Wahiduzzaman was supported by Startup funding from Nanjing University of Information Science and Technolgy, China. Alea Yeasmin was supported by RTP scholarship from Federation University Australia.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the initial support from Savin Chand, Federation University Australia.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Md Wahiduzzaman and Alea Yeasmin are employees of E-3 Complexity Ltd., Sydney. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Nunn, P.D. Oceanic Islands; Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 1994; pp. 1–204. [Google Scholar]

- Neall, V.E.; Trewick, S.A. The age and origin of the Pacific islands: A geological overview. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2008, 363, 3293–3308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nunn, P.D. Pacific Island Landscapes: Landscape and Geological Development of Southwest Pacific Islands, Especially Fiji, Samoa and Tonga; The University of the South Pacific: Suva, Fiji, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Power, S.; Schiller, A.; Cambers, G.; Jones, D.; Hennessy, K. The Pacific Climate Change Science Program. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 2011, 92, 1409–1411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunn, P.D.; Kumar, L.; McLean, R.; Eliot, I. Islands in the Pacific: Settings, distribution and classification. In Climate Change and Impacts in the Pacific; Kumar, L., Ed.; Springer Climate: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 1–35. [Google Scholar]

- International Monetary Fund. Tonga: 2017 Article IV Consultation-Press Release; and the Staff Report for Tonga; IMF Country Report No. 18/12; International Monetary Fund: Washington, DC, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Trenberth, K.E. Spatial and temporal variations in the Southern Oscillation. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 1976, 102, 639–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vincent, D.G. The South Pacific Convergence Zone (SPCZ): A review. Mon. Weather Rev. 1994, 122, 1949–1970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Widlansky, M.J.; Webster, P.J.; Hoyos, C.D. On the location and orientation of the South Pacific Convergence Zone. Clim. Dyn. 2011, 36, 561–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vincent, E.M.; Lengaigne, M.; Menkes, C.E.; Jourdain, N.C.; Marchesiello, P.; Madec, G. Interannual variability of the South Pacific Convergence Zone and implications for tropical cyclone genesis. Clim. Dyn. 2011, 36, 1881–1896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salinger, M.J.; McGree, S.; Beucher, F.; Power, S.B.; Delage, F. A new index for variations in the position of the South Pacific convergence zone 1910/11–2011/2012. Clim. Dyn. 2014, 43, 881–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latif, M.; Keenlyside, N.S. El Niño/Southern Oscillation response to global warming. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 20578–20583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Power, S.; Casey, T.; Folland, C.; Colman, A.; Mehta, V. Inter-decadal modulation of the impact of ENSO on Australia. Clim. Dyn. 1999, 15, 319–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Power, S.; Tseitkin, F.; Mehta, V.; Lavery, B.; Torok, S.; Holbrook, N. Decadal climate variability in Australia during the twentieth century. Int. J. Climatol. 1999, 19, 169–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callaghan, J.; Power, S.B. Variability and decline in severe landfalling tropical cyclones over eastern Australia since the late 19th century. Clim. Dyn. 2011, 37, 647–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mantua, N.J.; Hare, S.R.; Zhang, Y.; Wallace, J.M.; Francis, R.C. A Pacific interdecadal climate oscillation with impacts on salmon production. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 1997, 78, 1069–1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henley, B.J.; Gergis, J.; Karoly, D.J.; Power, S.; Kennedy, J.; Folland, C.K. A tripole index for the Interdecadal Pacific Oscillation. Clim. Dyn. 2015, 45, 3077–3090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salinger, M.J.; Renwick, J.A.; Mullan, A.B. Interdecadal Pacific Oscillation and South Pacific climate. Int. J. Climatol. 2001, 21, 1705–1721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gershunov, A.; Barnett, T.P. Interdecadal modulation of ENSO teleconnections. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 1998, 79, 2715–2725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Power, S.; Colman, R. Multi-year predictability in a coupled general circulation model. Clim. Dyn. 2006, 26, 247–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mochizuki, T.; Ishii, M.; Kimoto, M.; Chikamoto, Y.; Watanabe, M.; Nozawa, T.; Sakamoto, T.T.; Shiogama, H.; Awaji, T.; Sugiura, N.; et al. Pacific decadal oscillation hindcasts relevant to near-term climate prediction. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 1833–1837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gergis, J.L.; Fowler, A.M. A history of ENSO events since A.D. 1525: Implications for future climate change. Clim. Change 2009, 92, 343–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cubasch, U.; Wuebbles, D.; Chen, D.; Facchini, M.C.; Frame, D.; Mahowald, N.; Winther, J.-G. Introduction. In Climate Change 2013: The Physical Science Basis; Contribution of Working Group I to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Stocker, T.F., Qin, D., Plattner, G.-K., Tignor, M., Allen, S.K., Boschung, J., Nauels, A., Xia, Y., Bex, V., Midgley, P.M., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2013; pp. 119–158. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenzweig, C.; Casassa, G.; Karoly, D.J.; Imeson, A.; Liu, C.; Menzel, A.; Rawlins, S.; Root, T.L.; Seguin, B.; Tryjanowski, P. Assessment of observed changes and responses in natural and managed systems. In Climate Change 2007: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability; Contribution of Working Group II to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Parry, M.L., Canziani, O.F., Palutikof, J.P., van der Linden, P.J., Hanson, C.E., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2007; pp. 79–131. [Google Scholar]

- Chand, S.S.; Chambers, L.E.; Waiwai, M.; Malsale, P.; Thompson, C. Indigenous knowledge for environmental prediction in the Pacific Island countries. Weather Clim. Soc. 2014, 6, 445–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mann, M.E.; Zhang, Z.; Rutherford, S.; Bradley, R.S.; Hughes, M.K.; Shindell, D.; Ammann, C.; Faluvegi, G.; Ni, F. Global signatures and dynamical origins of the Little Ice Age and Medieval Climate Anomaly. Science 2009, 326, 1256–1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chand, S.S. Climate change scenarios and projections for the Pacific. In Climate Change and Impacts in the Pacific; Kumar, L., Ed.; Springer Climate: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 37–66. [Google Scholar]

- Folland, C.K.; Renwick, J.A.; Salinger, M.J.; Mullan, A.B. Relative influences of the Interdecadal Pacific Oscillation and ENSO on the South Pacific Convergence Zone. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2002, 29, 21-1–21-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chand, S.S.; Dowdy, A.; Bell, S.; Tory, K. A review of South Pacific tropical cyclones: Impacts of natural climate variability and climate change. In Climate Change and Impacts in the Pacific; Kumar, L., Ed.; Springer Climate: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 147–176. [Google Scholar]

- Nicholls, R.J.; Cazenave, A. Sea-level rise and its impact on coastal zones. Science 2010, 328, 1517–1520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Church, J.A.; White, N.J.; Hunter, J.R. Sea-level rise at tropical Pacific and Indian Ocean islands. Glob. Planet. Change 2006, 53, 155–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IPCC. Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis; Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Masson-Delmotte, V., Zhai, P., Pirani, A., Connors, S.L., Péan, C., Berger, S., Caud, N., Chen, Y., Goldfarb, L., Gomis, M.I., et al., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2021; p. 2391. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.; Church, J.A. Sea level trends, interannual and decadal variability in the Pacific Ocean. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2012, 39, L21701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunn, P.D. The end of the Pacific? Effects of sea level rise on Pacific Island livelihoods. Singap. J. Trop. Geogr. 2013, 34, 143–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Church, J.A.; Woodworth, P.L.; Aarup, T.; Wilson, W.S. (Eds.) Understanding Sea-Level Rise and Variability; Wiley-Blackwell: Chichester, UK, 2010; pp. 402–419. [Google Scholar]

- Becker, M.; Meyssignac, B.; Letetrel, C.; Llovel, W.; Cazenave, A.; Delcroix, T. Sea level variations at tropical Pacific islands since 1950. Glob. Planet. Change 2012, 80–81, 85–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knutson, T.R.; McBride, J.L.; Chan, J.; Emanuel, K.; Holland, G.; Landsea, C.; Held, I.; Kossin, J.P.; Srivastava, A.K.; Sugi, M. Tropical cyclones and climate change. Nat. Geosci. 2010, 3, 157–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ting, M.; Kushnir, Y.; Seager, R.; Li, C. Forced and internal twentieth-century SST trends in the North Atlantic. J. Clim. 2009, 22, 1469–1481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DelSole, T.; Tippett, M.K.; Shukla, J. A significant component of unforced multidecadal variability in the recent acceleration of global warming. J. Clim. 2011, 24, 909–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landsea, C.W.; Harper, B.A.; Hoarau, K.; Knaff, J.A. Can we detect trends in extreme tropical cyclones? Science 2006, 313, 452–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landsea, C.W.; Franklin, J.L. Atlantic hurricane database uncertainty and presentation of a new database format. Mon. Weather Rev. 2013, 141, 3576–3592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klotzbach, P.J.; Landsea, C.W. Extremely intense hurricanes: Revisiting Webster et al. (2005) after 10 years. J. Clim. 2015, 28, 7621–7629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dowdy, A.J. Long-term changes in Australian tropical cyclone numbers. Atmos. Sci. Lett. 2014, 15, 292–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chand, S.S.; Dowdy, A.J.; Ramsay, H.A.; Walsh, K.J.E.; Tory, K.J.; Power, S.B.; Bell, S.S.; Lavender, S.L.; Ye, H.; Kuleshov, Y. Review of tropical cyclones in the Australian region: Climatology, variability, predictability, and trends. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Clim. Change 2019, 10, e602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chand, S.S.; Walsh, K.J.E.; Camargo, S.J.; Kossin, J.P.; Tory, K.J.; Wehner, M.F.; Chan, J.C.L.; Klotzbach, P.J.; Dowdy, A.J.; Bell, S.S.; et al. Declining tropical cyclone frequency under global warming. Nat. Clim. Change 2022, 12, 655–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diamond, H.J.; Lorrey, A.M.; Knapp, K.R.; Levinson, D.H. Development of an enhanced tropical cyclone tracks database for the Southwest Pacific from 1840 to 2010. Int. J. Climatol. 2012, 32, 2240–2250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diamond, H.J.; Lorrey, A.M.; Renwick, J.A. A Southwest Pacific tropical cyclone climatology and linkages to the El Niño–Southern Oscillation. J. Clim. 2013, 26, 3–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diamond, H.J.; Renwick, J.A. The climatological relationship between tropical cyclones in the Southwest Pacific and the Southern Annular Mode. Int. J. Climatol. 2015, 35, 613–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diamond, H.J.; Lorrey, A.M.; Renwick, J.A. The climatological relationship between tropical cyclones in the Southwest Pacific and the Madden–Julian Oscillation. Int. J. Climatol. 2015, 35, 676–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuleshov, Y.; Qi, L.; Fawcett, R.; Jones, D. On tropical cyclone activity in the Southern Hemisphere: Trends and the ENSO connection. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2008, 35, L14S08. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuleshov, Y.; Chane-Ming, F.; Qi, L.; Chouaibou, I.; Hoareau, C.; Roux, F. Tropical cyclone genesis in the Southern Hemisphere and its relationship with the ENSO. Ann. Geophys. 2009, 27, 2523–2538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramsay, H.A.; Camargo, S.J.; Kim, D. Cluster analysis of tropical cyclone tracks in the Southern Hemisphere. Clim. Dyn. 2012, 39, 897–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chand, S.S.; Walsh, K.J.E. Tropical cyclone activity in the Fiji region: Spatial patterns and relationship to large-scale circulation. J. Clim. 2009, 22, 3877–3893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chand, S.S.; Walsh, K.J.E. The influence of the Madden–Julian Oscillation on tropical cyclone activity in the Fiji region. J. Clim. 2010, 23, 868–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chand, S.S.; Walsh, K.J.E. Influence of ENSO on tropical cyclone intensity in the Fiji region. J. Clim. 2011, 24, 4096–4108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chand, S.S.; Tory, K.J.; McBride, J.L.; Wheeler, M.C.; Walsh, K.J.E. The different impact of positive-neutral and negative-neutral ENSO regimes on Australian tropical cyclones. J. Clim. 2013, 26, 8008–8016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashok, K.; Behera, S.K.; Rao, S.A.; Weng, H.; Yamagata, T. El Niño Modoki and its possible teleconnection. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 2007, 112, C11007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kug, J.-S.; Jin, F.-F.; An, S.-I. Two types of El Niño events: Cold tongue El Niño and warm pool El Niño. J. Clim. 2009, 22, 1499–1515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kao, H.-Y.; Yu, J.-Y. Contrasting eastern-Pacific and central-Pacific types of ENSO. J. Clim. 2009, 22, 615–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.-M.; Webster, P.J.; Curry, J.A. Impact of shifting patterns of Pacific Ocean warming on North Atlantic tropical cyclones. Science 2009, 325, 77–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.-M.; Webster, P.J.; Curry, J.A. Modulation of North Pacific tropical cyclone activity by three phases of ENSO. J. Clim. 2011, 24, 1839–1849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.T.; Yu, J.-Y. The two types of ENSO in CMIP5 models. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2012, 39, L11704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, C.-C.; Li, Y.-H.; Li, T.; Lee, M.-Y. Impacts of central Pacific and eastern Pacific El Niños on tropical cyclone tracks over the western North Pacific. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2011, 38, L16712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G. How does shifting Pacific Ocean warming modulate on tropical cyclone frequency over the South China Sea? J. Clim. 2011, 24, 4695–4700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klotzbach, P.J. The Madden–Julian Oscillation’s impacts on worldwide tropical cyclone activity. J. Clim. 2014, 27, 2317–2330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leroy, A.; Wheeler, M.C. Statistical prediction of weekly tropical cyclone activity in the Southern Hemisphere. Mon. Weather Rev. 2008, 136, 3637–3654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendon, H.H.; Zhang, C.; Glick, J.D. Interannual variation of the Madden–Julian oscillation during austral summer. J. Clim. 1999, 12, 2538–2550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.