Abstract

Over the past decade, China’s industrialization and urbanization have accelerated rapidly, leading to the extensive consumption of fossil fuels and the accumulation of atmospheric pollutants, which pose significant health risks to the population. This study analyses the spatiotemporal evolution patterns of major air pollutants over the past decade based on data from meteorological- and environmental-factor monitoring from various observation stations in the Yangtze River Delta region of China from 2018 to 2024, as well as air pollution monitoring and statistical data such as mortality rates of weather-sensitive diseases and socioeconomic attributes of patients. Based on mathematical models, a quantitative ‘dose–response’ relationship is established among meteorological factors, air pollution factors and mortality rates of sensitive diseases within the region. (1) PM2.5 and ozone are the primary air pollutants in the Yangtze River Delta region, with significant self-correlation characteristics in pollutants observed in coastal areas and regions around provincial capitals. (2) The synergistic effects of temperature + NO2 and relative humidity + SO2 significantly impact mortality from sensitive diseases, while the cumulative lag effect of relative humidity on respiratory diseases exhibits a V-shaped temporal variation. (3) Pollutant cumulative lag effects are pronounced, with a 10 μg/m3 increase in PM2.5 leading to a 0.93% and 0.71% rise in the mortality risks of non-accidental and circulatory system diseases over the lag period of 15 days, compared to a single-day lag, showing an additional 0.06% and 0.04% increase, respectively.

1. Introduction

Global climate and environmental changes have several impacts on human health, such as an increase in the probability of related diseases and deaths [1,2,3]. The Fourth and Fifth Assessment Reports of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) also clearly indicate that global climate change will continue to have direct or indirect impacts on human health [4,5]. With the development of urbanization and industrialization, urban air pollution represented by haze has intensified, which can easily lead to respiratory and circulatory system diseases, seriously affecting people’s normal lives [6]. There are studies showing that nearly three million people worldwide die directly or indirectly from outdoor air pollution injuries annually, especially in China, where air pollution is severe, with pollutants such as PM2.5 exceeding the standard [7,8,9] and affecting a wider range of people. Therefore, a systematic analysis of the synergistic mechanism between climate conditions and air pollution on the sensitive disease processes of urban residents has important practical significance [10].

Previous studies have shown that excessively high or low temperatures can have negative effects on human health [11,12]. Under normal circumstances, the human body’s well-developed temperature regulation system can maintain a dynamic balance between heat production and dissipation [13]. However, for special populations such as the elderly or infants, their ability to adapt to abnormal weather is relatively weak due to the degradation or incomplete development of their temperature regulation system [14]. Studies have found that in high-temperature environments, the mortality rate of heat radiation-related diseases among urban residents increases and the risk of developing climate-sensitive diseases significantly increases [15]. Harm significantly increases with age, especially among the elderly population aged 50 and above [16,17,18]. However, excessively low temperatures can also have a significant negative impact on human health [19]. Studies suggest that the number of deaths from heart disease is higher in winter than in other seasons [20]. Extremely cold weather can overload the cardiovascular system, causing blood to flow from the skin into the body and increasing the circulatory load on the heart. In addition, studies have found that the sudden cold weather caused by cold waves leads to a rapid decrease in air temperature, which can easily cause the recurrence or aggravation of diseases such as colds, chronic bronchitis and asthma, and can also induce joint and cardiovascular diseases in middle-aged and elderly populations [21,22,23].

Respiratory and circulatory system diseases are weather sensitive and hence closely related to climate and environmental changes in their onset and prevalence [24]. The climate environment can directly affect the human body system through its physical characteristics, causing physiological and pathological changes in the body, thereby directly leading to human diseases. It can also indirectly cause diseases by altering the reproduction and transmission of pathogenic microorganisms [25]. A study found that the relationship between temperature and disease incidence in the population tends to exhibit a J-shaped or U-shaped distribution pattern. Under relatively suitable temperature conditions, the disease incidence among residents is lowest [26]. As the temperature increases or decreases, the number of deaths shows an upward trend. In addition, atmospheric pollutants, especially typical pollutants such as PM10, PM2.5, NO2, and ozone, have negative impacts on human health [27,28,29]. These fine particulate pollutants can become viral carriers and remain in different parts of the respiratory tract, inducing respiratory diseases such as chronic bronchitis and bronchial asthma [30]. Sulphide and nitrogen oxides can stimulate the mouth and nose of humans, exacerbating the incidence and prevalence of related weather-sensitive diseases [31]. Long-term exposure to PM2.5 pollution in the atmospheric environment significantly increases the mortality rates of respiratory diseases, cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases, and cancer, especially asthma, pulmonary inflammation, lung cancer, and other diseases [32].

Meanwhile, existing evidence suggests that temperature changes and air pollution may have synergistic effects on adverse health outcomes [25,33]. Atmospheric pollutants laden with toxic and harmful substances can directly enter the bloodstream, affecting the respiratory and circulatory systems and posing risks to human health [33]. Meteorological factors indirectly induce diseases by affecting the survival, reproduction, and transmission processes of microorganisms [34]. Changes in the climate environment can alter the chemical reactions of atmospheric pollutants and physical processes such as deposition, affecting the concentration distribution and diffusion of these pollutants, thereby exacerbating air pollution [35]. Therefore, to better elucidate the impacts of climate change and air pollution on human health, it is necessary to integrate meteorological factors and atmospheric pollutants to study the synergistic effects of both on weather-sensitive diseases.

Overall, existing studies have explored the relationship between meteorological factors and weather-sensitive diseases. However, most of these studies focus on a single city or specific type of disease, with limited spatial scales and scopes in case selection, lacking case studies on the synergistic relationships among meteorological factors, air pollution factors, and meteorology-sensitive diseases on a large regional scale. Meanwhile, with the accelerated urbanization process in China’s eastern coastal regions, core areas primarily characterized by urban agglomerations and metropolitan circles have formed gradually. These areas are densely populated and feature frequent economic activities, necessitating corresponding meteorological health research. Taking the Yangtze River Delta region of China as the research subject, this study is the first to fit the spatial-temporal distribution patterns of meteorological environments and air pollution at a large regional scale, while conducting statistical and mathematical analysis of disease prevalence across major cities in the region. It specifically focuses on respiratory and circulatory diseases, quantitatively analysis the ‘dose–response’ relationships among meteorological environmental factors, air pollution factors and weather-sensitive diseases.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Scope

The Yangtze River Delta region encompasses 26 cities in the Shanghai, Jiangsu, Zhejiang and Anhui provinces of China. Despite accounting for less than 4% of the country’s total land area, it is home to approximately 235 million permanent residents and contributes nearly one fourth of China’s total economic output [36]. In 2024, the GDP of the Yangtze River Delta region exceeded 33 trillion yuan, with a per capita GDP reaching 139,400 yuan, making it one of the most economically vibrant, open and innovation-driven urban clusters in China [37] (Figure 1). The Yangtze River Delta region features a typical subtropical monsoon climate, characterized by distinct seasons and synchronized rainfall and heat. The average annual temperature ranges from 15 to 17 °C, with annual precipitation between 1000 mm and 1200 mm, predominantly concentrated in summer. Influenced by the East Asian monsoon, summer is hot and humid, while winter is mild with little snow, often accompanied by extreme weather events such as typhoon-induced rainstorms [38]. In response to the practical problems of air pollution prevention and control, the Chinese government has implemented the ‘Detailed Rules for the Implementation of the Action Plan for Air Pollution Prevention and Control’ in the Yangtze River Delta since 2014. Through various measures such as energy structure adjustment, industrial upgrading and transformation, mobile pollution source control, and regional joint prevention and control, it aims to comprehensively implement the prevention and control of air pollution [39]. Studies have shown that between 2019 and 2023, the PM2.5 concentration in the Yangtze River Delta region has continued to decrease and the population’s exposure situation will significantly improve. The proportion of population exposed to PM2.5 concentrations below 35 µg/m3 increased from 25.9% to 79.9%, attributed to a decrease of approximately 30% in premature deaths and economic losses. However, ozone pollution is showing a fluctuating upward trend. In 2022, the number of ozone-related premature deaths and economic losses exceeded PM2.5. It is necessary to strengthen the coordinated governance of PM2.5 and ozone, consolidate the achievements of air quality improvement, and safeguard public health.

Figure 1.

Location of Yangtze River Delta region.

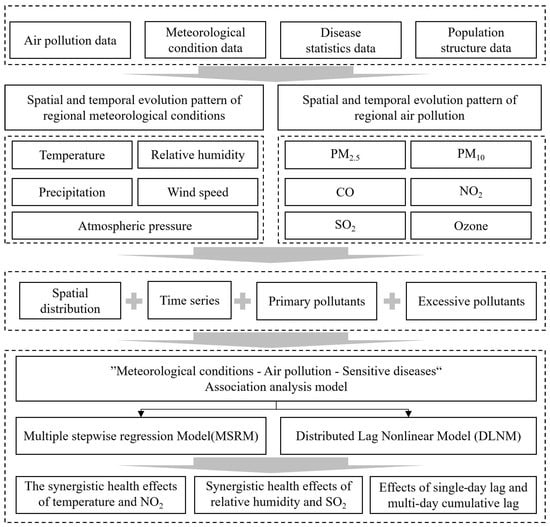

2.2. Research Framework

First, we quantified the frequency of incidents such as excessive and heavy pollution and identified the primary types of pollutants in the affected area, based on monthly climate and environmental, air pollution and statistical data on circulatory and respiratory diseases in the Yangtze River Delta region from 2018 to 2024. Second, through spatial pattern and auto-correlation analysis methods, the spatial evolution characteristics and distribution patterns of the regional climate and pollutants were identified and the correlation between air pollution and climate environment in each city was extracted. Finally, based on the multiple stepwise regression model and distributed lag nonlinear model (DLNM), a correlation analysis framework of ‘meteorological conditions for air pollution sensitive diseases’ were constructed. The synergistic health effects of temperature, NO2, relative humidity and SO2 on respiratory and circulatory system diseases were then identified (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Framework of this study.

2.3. Data Sources and Processing

2.3.1. Meteorological Observation Data

The meteorological data was predominantly sourced from the China Meteorological Data Sharing Service Network (http://www.nmic.cn/ accessed on 12 June 2025), which provides daily ground meteorological data for 26 cities in the Yangtze River Delta region. Monitoring data was obtained from 92 meteorological observation stations in 26 cities, including Shanghai, Hangzhou, Nanjing and Hefei in China. The research time span was from 2020 to 2023, and the collection range was from 8:00 to 20:00 daily. Studies have shown that urban populations mainly work between 8:00 and 20:00 [15,17]. The survey data on activity patterns during this time period shows that it covered 92% of the outdoor exposure time of the population [17]. The data structure includes ten meteorological data items, including monthly average pressure (hPa), monthly maximum pressure (hPa), monthly minimum pressure (hPa), average temperature (°C), maximum temperature (°C), minimum temperature (°C), average relative humidity (%), minimum relative humidity (%), average sunshine hours (h), and average wind speed (m/s).

2.3.2. Air Pollution Data

With the continuous improvement of air quality monitoring and forecasting technology in China, air monitoring stations have been set up in cities at all levels to achieve real-time monitoring of the urban air quality index (AQI). This study collected concentration data of six air pollutants, including PM2.5, PM10, CO, NO2, ozone and SO2, from 92 national air quality monitoring stations in the Yangtze River Delta region between 2018 and 2024. The data is provided by the China Environmental Monitoring Station, a real-time release platform for urban air quality across the country (https://www.cnemc.cn/ accessed on 12 June 2025). According to the data validity regulations in the Environmental Air Quality Standard (GB 3095-2012) [24], we screened and analyzed the data and found a significant correlation between AQI and the concentration of six types of pollutants. We classified air quality levels according to specific standards, as follows: excellent (AQI ≤ 50), good (50 < AQI ≤ 100), mild pollution (100 < AQI ≤ 150), moderate pollution (150 < AQI ≤ 200), severe pollution (200 < AQI ≤ 300) and extreme pollution (AQI > 300) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Classification of Environmental Air Quality.

To ensure data validity, the study standardized the data threshold and focused on screening data with a monthly effective record of no less than 600 h. PM2.5 and ozone monitoring data require that the station has no fewer than 324 valid records within one year, no fewer than 27 valid values within one month, and no fewer than 25 valid records within two months. As shown in Table 2, taking Shanghai as an example, the daily average AQI in 2023 was 79.33 and the range of air pollution index during the quarter ranged from excellent to highly polluted. Statistics show that there are significant differences in AQI values among monitoring stations (F = 8.322, p-value = 0.000), indicating that there were significant differences in air pollution values among cities in the Yangtze River Delta region. The sample distribution of the data meets the experimental requirements (Table 2).

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics of air quality index and various sub-pollution indicators.

2.3.3. Climate-Sensitive Diseases

Previous studies have found through statistical analysis of disease data and spectra that respiratory and circulatory system diseases that are climate-sensitive have the highest mortality rates [32,33]. This study focuses on selecting two types of these diseases for meteorological correlation analysis (Table 3). It collects daily death data from the statistical yearbooks of 26 cities in the Yangtze River Delta region from 1 January 2018 to 31 December 2024. The data structure includes information such as death date, gender and cause of death. The causes of death are coded according to the International Classification of Diseases (ICD), Tenth Edition (ICD-10), and classified based on criteria such as circulatory system disease death data (ICD-10:I00-I99), respiratory system disease death data (ICD-10:J00-J99)and other non-accidental death data (ICD-10:A00-R99) [37,38]. The registration process for death cases in China is completed by medical institutions filling out standard death certificates and the diagnostic process is carried out by hospitals and doctors with professional knowledge. The disease prevention and control centre supervises the process so that the data source is authentic and reliable [37]. This study strictly followed the ICD-10 standard to summarize and organize disease statistical data, eliminating incomplete information and rigorously controlling data quality. Meteorological and atmospheric pollutant concentration data are both from officially released data. Data quality has been checked, judged and managed to eliminate situations such as missing data structures [38].

Table 3.

Statistical data on mortality rates in the Yangtze River Delta region from 2018 to 2024 (unit: annual death toll per 100,000 people).

The baseline mortality rate refers to the probability of a population naturally dying within a specific period without any additional risk factors or intervention measures [25]. This data is from the ‘China Health Statistics Yearbook’ (http://www.nhc.gov.cn/ accessed on 12 June 2025). Non-accidental mortality rate refers to the proportion of deaths caused by non-accidental reasons such as illnesses, suicides and homicides to the total population during a certain period [26,27]. The data is sourced from urban statistical yearbooks [27].

2.4. Research Methods

2.4.1. Spatial Correlation Model

To explore the spatial-temporal correlation of air pollution between cities in the region, we constructed a global spatial auto-correlation index, which is Moran’s I index [30]. This indicator quantitatively analyses the agglomeration effect of air pollutant indicators in various cities within the region. The formula for calculating Moran’s index is as follows:

In the formula, S2 is the sample variance; n is the number of samples; is the spatial weight matrix; , represents the observed values at spatial positions i and j; and is the mean of attributes. The range of Moran’s index values is [−1, 1]. When the value is greater than 0, there is a positive spatial correlation, that is, the observed values of each unit around the high (low) values are also high (low), showing spatial clustering characteristics. When the value is less than 0, it indicates that there is a negative correlation between each spatial unit, with high and low values clustered together. When it equals 0, it indicates that there is no spatial correlation, and high and low values are randomly distributed in space [31]. The strength and significance of spatial correlation are judged based on the Z- and p-values obtained from Monte Carlo hypothesis testing, as shown in Table 4. When the confidence level is higher, it indicates that the analyzed data tends to be spatially clustered, while when it is lower, it indicates that the data tends to be dispersed [31].

Table 4.

Statistics of spatial auto-correlation test.

2.4.2. Generalized Additive Model

Numerous studies have shown that the impact of pollutants on diseases does not reach its maximum on the same day, and there may be some lag and cumulative effects [23,24,25]. Since the late 19th century, time series regression models have been widely used to investigate the adverse effects of atmospheric pollutants and meteorological factors on human health [31]. Among them, the most mature and widely used is the Generalized Additive Model (GAM) [32]. The Generalized Additive Model (GAM) is a modelling method that evolved from the Generalized Linear Model (GLM) and has been widely used in research in natural sciences, medicine, economics and other fields [32]. The GAM does not require strict limitations of the parameter dependency relationship between the response and explanatory variables. It allows the relationship between the dependent and the predictor variables to be represented as the sum of smoothing functions of each predictor variable, which can better adapt to complex data patterns and effectively explain the complex nonlinear relationship between the independent and dependent variables [32].

Among them, is the expected value of the dependent variable. is the connection function between the independent and dependent variables, and different connection functions are selected for different data distribution types. is the intercept. is a univariate function for each predictor variable . (e.g., the natural cubic spline, smooth spline, and kernel smoothing functions). is the residual. Based on the principle of least squares, the model selects the variables that contribute the most to the dependent variable from many independent variables and introduces them into the equation, while removing unimportant independent variables from the equation. We repeat this process and ultimately establish the optimal regression fitting equation based on the observed data:

In the formula, is a constant term, is the regression coefficient, and is the random error. Previous studies have shown that the relationship between the dependent variable and each independent variable may be linear or nonlinear [33]. Therefore, if only Formula (3) is used to fit the relationship between the dependent variable and the independent variable, it will lead to a series of problems such as excessive computational complexity and overfitting. Therefore, this article uses Semi Parametric Generalized Additive Models to select significant variables from numerous meteorological and air pollution factors, and establishes an analytical model strongly associated with meteorological-sensitive diseases. The form of the model is as follows:

Among them, represents various nonparametric smoothing functions; means linear function; is the regression coefficient representing the interaction term between various indicators in the GAM; α represents the residual.

2.4.3. Distributed Lag Nonlinear Model

Distributed Lag Nonlinear Model (DLNM) can flexibly describe the sustained impact of predictor variables in lagged spatiotemporal environments. It first appeared in epidemiology and was later introduced into the study of temperature health effects [40]. The core algorithm of DLNM is to construct a cross basis, which is a two-dimensional spatial matrix that can simultaneously describe the response relationship curve and distribution lag effect of variables [41]. Considering that the onset process of meteorological-sensitive diseases is a result of long-term accumulation, we use the DLNM for lag analysis:

Among them, the dependent variable is the number of deaths from related diseases. x generally refers to environmental factors such as monthly average air pollutant concentration, temperature and relative humidity during the same period. The connection function usually adopts the Poisson distribution. is a new variable generated by the transformation of the independent variable x through a basis function. A lag dimension is then added to the exposed relationship, namely the S matrix:

Among them, L is the longest lag day defined by the model, which can achieve the dependent variable and lag distribution in the independent variable dimension. We then select appropriate basis functions for each column in the S matrix to obtain a three-dimensional sequence.

3. Results

3.1. PM2.5 and Ozone as Key Air Pollutants in the Yangtze River Delta Region

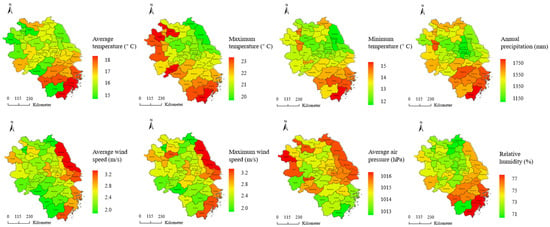

Figure 3 shows the annual spatial distribution of meteorological elements in various cities within the Yangtze River Delta region. Overall, the average annual temperature range in the Yangtze River Delta region is between 15.3 °C and 18.4 °C, with a relative humidity of about 77% and an average wind speed of 2.4 m/s. The average annual precipitation in the region ranges from 1150 millimetres to 1750 millimetres, with a decreasing trend from south to north. The average annual precipitation in Zhejiang Province in the south is 1600 millimetres, while it is 1200 millimetres in Jiangsu Province in the north. The southern region of Zhejiang Province has the highest annual precipitation, about 1750 millimetres, while the areas with the lowest precipitation are Suqian and Huainan in central Jiangsu Province, about 1100 millimetres. In addition, Wenzhou City has the highest average annual temperature of about 18.4 °C, while the neighbouring Lishui City has the lowest average annual temperature of 15.1 °C. The spatial distribution characteristics of the highest and lowest annual temperatures in other cities are basically consistent with the characteristics of the average temperature, and there is little difference within the region. Meanwhile, due to the highest average altitude and lowest average air pressure in the region, Wenzhou has the highest average relative humidity and corresponding annual precipitation. Except for cities along the eastern coast such as Lianyungang, Yancheng and Nantong, the wind speed in other areas is relatively similar.

Figure 3.

Spatial distribution pattern of meteorological elements in various cities within Jiangsu Province from 2018 to 2024.

The AQI of 26 cities in the Yangtze River Delta region is shown in Figure 4. There are significant differences in the proportion of good air quality and polluted days among different cities. Among them, cities in Anhui Province have the highest proportion of excellent days, followed by Zhejiang Province, while cities in Jiangsu Province have a relatively low proportion of excellent days.

Figure 4.

The air quality status of cities in the Yangtze River Delta during the research period.

The proportion of days with excellent air quality ratings in Jiangsu Province range from 72.6% to 89.2%. Among them, Suzhou and Huai’an have the least and most excellent days, respectively. The proportion of moderate and above pollution days range from 1.3% to 5.2%, with Suzhou having the highest proportion and Huai’an having the lowest proportion of pollution days. The proportion of days rated as excellent air quality in Zhejiang Province range from 81.6% to 91.2%, with Hangzhou having the lowest proportion and Quzhou having the highest proportion. The proportion of moderate and above pollution days range from 0.9% to 4.3%. Quzhou City has the lowest proportion of pollution days and the best air quality in the province, while Hangzhou City has the highest proportion and a more severe pollution situation than other cities. In Anhui Province, the proportion of days with good urban air quality is on the rise, ranging from 81.6% to 98.3%. Hefei City has the least number of days with good air quality, while Anqing City has the greatest number of days with good air quality. The proportion of moderate and above pollution days ranges from 0.2% to 8.1%, with Anqing City having the lowest proportion of pollution days. Hefei has the highest proportion of pollution days and the worst air quality in the province.

The primary pollutant refers to the pollutant with the highest air quality index (IAQI) among all pollutants when the AQI is greater than 50. It reflects the main types of air pollution in the region at present. After statistical analysis of the number of days that the primary pollutants appeared during the research period, we found that PM2.5 and ozone, as the primary pollutants, generally appeared higher than other pollutants and were the two most important pollutants in the Yangtze River Delta region (Table 5).

Table 5.

The number of days that the primary pollutant appeared in 26 cities in the Yangtze River Delta region during the research period.

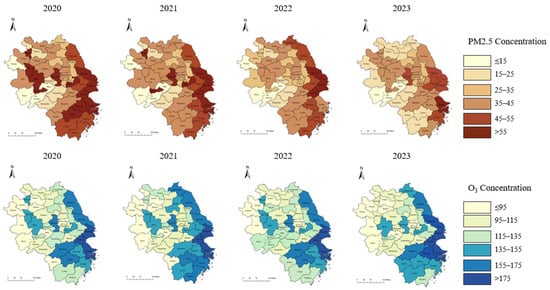

3.2. PM2.5 and Ozone Exhibiting Significant Spatial Heterogeneity Characteristics

The spatial distribution of average annual PM2.5 concentration in the Yangtze River Delta region is shown in Figure 5. From the trends in the past decade, the overall pollution level in the Yangtze River Delta region has gradually decreased, but the spatial heterogeneity of PM2.5 concentration distribution is evident. The overall characteristics are characterized by a differentiated distribution being ‘high in the eastern coastal areas and low in the central and western inland areas’ and ‘high in the southern regions and low in the northern regions’. Except for cities in the southern part of Jiangsu Province and the eastern part of Zhejiang Province, most cities have high PM2.5 concentrations, presenting a heavy pollution core centred around the three provincial capitals of Nanjing, Hangzhou and Hefei, forming a patchy pollution agglomeration area in the central and southern parts of the Yangtze River Delta around the core cities. From a temporal perspective, although the PM2.5 concentration in heavily polluted core areas shows a fluctuating downward trend, it is still significantly higher than in surrounding areas. There is a spatial evolution trend of high pollution areas gradually spreading from provincial capitals to surrounding cities within the region.

Figure 5.

Spatial distribution pattern of PM2.5 and ozone concentrations in the Yangtze River Delta region from 2018 to 2024.

As shown in Figure 5, the annual average concentration of ozone in the region follows a spatial distribution pattern being ‘high in the south and low in the north’. The heavily polluted areas are mainly concentrated in eastern coastal cities such as Hangzhou, Ningbo, Nantong and Shanghai. There are significant inter-annual differences in the distribution of heavily polluted areas. In 2020, the overall pollution level was the highest and areas with high ozone concentrations spread to the central region of Anhui Province and the western region of Zhejiang Province. In 2024, the region will have the smallest heavily polluted areas with generally low ozone concentrations, but ozone pollution in coastal areas will still be severe. In addition, the annual average concentration of ozone in western and southern cities of Anhui Province is generally lower than that in other cities, mainly due to the combined effects of extensive vegetation coverage, relatively less industrial activity and fewer sources of pollutant emissions in the region [42,43].

We conducted spatial auto-correlation analysis on the clustering characteristics of PM2.5 pollution in various cities and obtained the global Moran’s index, as shown in Table 6. From 2018 to 2024, the global Moran’s index range for PM2.5 pollution in the Yangtze River Delta region was 0.39–0.61 (all positive values) and passed the 99% significance test. The results indicate that PM2.5 pollution has a significant global positive correlation and spatial agglomeration characteristics at the urban scale of the Yangtze River Delta. Among them, the global Moran’s index of PM2.5 was the highest in 2020, and the global Moran’s index of ozone was the highest in 2022. The spatial clustering characteristics of the two types of pollutants were strongest in the above years.

Table 6.

Global Moran’s Index of PM2.5 and Ozone in the Yangtze River Delta Region from 2018 to 2024.

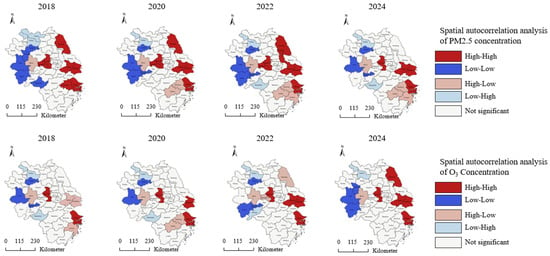

3.3. The Distribution of PM2.5 and Ozone in Coastal Areas and Around Provincial Capital Cities Showing Significant Spatial Autocorrelation Characteristics

Further analysis of local autocorrelation in each city is shown in Figure 6. We divide the research area into five types based on city, including a non-significant type, ‘High-High’ type area, ‘High-Low’ type area, ‘Low-High’ type area, and ‘Low-Low’ type area. From 2018 to 2024, the local autocorrelation types of regional PM2.5 pollution are mainly characterized by insignificant, ‘High-High’, and ‘Low-Low’ distributions. The ‘High-High’ pattern indicates that the PM2.5 concentration in this city and surrounding cities is relatively high and the spatial difference in pollutant concentration is small. The ‘Low-Low’ type indicates that both the city and surrounding cities have low PM2.5 concentrations and the regional pollution level is generally low. The non-significant type indicates that the concentration of pollutants in the region does not show obvious spatial polarization characteristics. During the research period, ‘High-High’ agglomeration cities were mainly distributed in the eastern coastal areas of the region, with overall high levels of PM2.5 concentration and strong agglomeration. Some studies suggest that the industrial structure of cities of the same type is similar, and high-polluting industries are clustered and distributed, resulting in obvious clustering characteristics of air pollution between cities [44]. The ‘Low-Low’ agglomeration cities are mainly distributed in the central region of Anhui Province, which is mainly mountainous with low industrialization and generally low air pollution levels.

Figure 6.

Local spatial auto-correlation analysis of PM2.5 and ozone concentrations in the Yangtze River Delta region from 2018 to 2024.

In addition, Suqian, Mount Huangshan and Anqing show ‘Low-High’ agglomeration characteristics in 2020, 2022 and 2024, respectively. Hefei, Jinhua and Taizhou exhibit a ‘High-Low’ spatial agglomeration characteristic in 2020, 2022 and 2024. These cities have a significant spatial difference in PM2.5 concentration compared to surrounding cities, and their air pollution phenomena rely more on industrial structure and population distribution patterns, with weaker correlations to regional industrial structures and population mobility; they are relatively less affected by surrounding cities.

Table 6 shows the results of local spatial auto-correlation analysis of ozone. During the study period, the global Moran’s index of ozone pollution in the Yangtze River Delta region ranged from 0.47 to 0.72. The values are all positive; the 99% significance test also indicates a significant spatial positive correlation between ozone pollution. In 2022, the global Moran’s index is the largest and the spatial clustering characteristics are the most obvious. The results are consistent with PM2.5. The local auto-correlation types of ozone pollution are mainly non-significant, ‘High-High’ and ‘Low-Low’, indicating that most cities exhibit positive clustering characteristics in pollutant concentrations; the pollutant concentrations in cities and surrounding areas show the same high or low phenomenon. Ozone pollution is manifested in ‘High-High’ agglomeration cities, mainly provincial capital cities and eastern coastal cities. For example, cities such as Suzhou and Wuxi in eastern Jiangsu, Shanghai, and Ningbo in Zhejiang Province have close air pollution links with surrounding cities. The ‘Low-Low’ agglomeration cities are mainly distributed in Anhui Province and the overall ozone concentration in most cities is relatively low. In addition, in the central region of Anhui Province, some cities also exhibit ‘Low-High’ and ‘High-Low’ distribution characteristics, indicating that the ozone pollution in these cities is related to their own industrial structure and has little correlation with surrounding areas.

3.4. Descriptive Statistics of Deaths from Meteorological Factors, Air Pollution Factors and Related Sensitive Diseases

By analyzing the distribution pattern of air pollution in the Yangtze River Delta region, it has been determined that PM2.5 and ozone are the two most significant pollutants affecting the region. We collected death statistics, pollutant data and meteorological element data, and constructed a quantitative relationship between pollutants and resident diseases based on a GAM to quantitatively evaluate the impact of short-term exposure to PM2.5 and ozone on mortality risk. Considering the differences in pollutant levels and meteorological factors in different regions, we established an independent model with cities as the smallest unit to discuss the effects of PM2.5 and ozone on non-accidental, respiratory and circulatory system deaths and to explore gender and seasonal differences in health effects. Finally, the combined effect values of each city affected by pollutants were obtained through meta-analysis.

Table 7 presents descriptive statistics on the number of deaths and environmental factors. The daily average number of other non-accidental deaths in each city ranged from 5 to 98, with Shanghai having the highest number of deaths and Zhoushan having the lowest. The daily average number of respiratory system-related deaths ranged from 7 to 140, while the daily average number of circulatory system-related deaths ranged from 8 to 163. The daily average concentration of PM2.5 in various cities ranged from 40.1 μg/m3 to 68.9 μg/m3 and the daily average concentration of ozone ranged from 60.6 μg/m3 to 90.8 μg/m3, both exceeding the recommended range standards published by the International Health Organization [45]. The daily average temperature ranged from 11.7 °C to 19.7 °C and the relative humidity ranged from 60.9% to 78.5%, indicating strong consistency in meteorological conditions within the study area.

Table 7.

Descriptive statistics of atmospheric environmental factors and the death toll in 26 cities in the Yangtze River Delta region from 2018 to 2024.

4. Discussion

4.1. Combination of Temperature with NO2 and Relative Humidity with SO2 as Having a Synergistic Effect on Sensitive Diseases

We analyzed the synergistic health effects of meteorological and air pollution factors. Table 8 presents a statistical table of synergistic effects on circulatory diseases, showing the classified combinations of meteorological and pollution element factors that have passed significance tests. From the perspective of the meteorological factors’ synergistic effect, average temperature and relative humidity have a significant impact on circulatory system diseases, as both can affect the internal environmental balance of the human body, thereby influencing the circulatory system [46]. In addition, the results indicate that the synergistic effect of the two factors has no significant impact on males but has a significant impact on female patients. From the perspective of the synergistic effect of pollution factors, temperature, PM2.5 and NO2 have a significant synergistic effect on total circulatory system diseases, and the impact is more pronounced on the elderly population aged 55 and above. Relative humidity, NO2 and SO2 have a significant synergistic effect on total circulatory system diseases, with a more pronounced effect on the male population.

Table 8.

The synergistic effect of meteorological and air pollution factors on circulatory diseases in the Yangtze River Delta Region from 2018 to 2024.

Under the combination of low temperature and low humidity, respiratory diseases have the highest number of deaths. This indicates that respiratory diseases in the Yangtze River Delta region are mainly affected by low temperature environments, and cold air and low humidity environments mainly stimulate the respiratory tract to cause the disease. The number of deaths from total circulatory system diseases has also significantly increased, indicating that such diseases are also affected by the low-temperature effect. In addition, when the environment is in a combination of high temperature and high humidity, the mortality rate of circulatory system diseases increases significantly.

Under the combination of low temperature and high-concentration NO2, there are more deaths from respiratory diseases, and women and people over 56 years old are high-risk and sensitive populations. When the temperature or relative humidity is constant, as the value of another variable decreases, the number of deaths from respiratory diseases gradually increases. When PM2.5 is at a high concentration, with the continuous increase in SO2 and NO2 concentrations, the number of respiratory disease deaths in the Yangtze River Delta region significantly increases and the synergistic effect is obvious. Meanwhile, comparing the synergistic effect parameters of PM2.5 with SO2 and NO2, it was found that the synergistic effect between PM2.5 and NO2 was more significant and the population under 12 and over 56 years old were highly sensitive. Related studies have shown that an increase in NO2 concentration in the atmosphere leads to an increase in PM2.5 concentration [47] and the synergistic effect has the greatest impact on circulatory system diseases at higher concentrations.

Under the combination of low humidity and high concentration of SO2, there are more deaths from circulatory system diseases. As the relative humidity decreases and the concentration of SO2 increases, the number of deaths continues to steadily increase, with susceptible individuals being under the age of 12. Due to the relative average annual humidity in the Yangtze River Delta region being above 80%, there is a certain removal effect on atmospheric pollutants when the relative humidity is high. Therefore, the relationship between relative humidity and pollution factors SO2 and NO2 mainly exhibits a low humidity effect [48]. When the relative humidity is below ~70%, the harm to the circulatory system diseases in the Yangtze River Delta region significantly increases with the increase in pollutant concentration.

4.2. Cumulative Lag Effect of Air Pollutants and Increase in the Mortality Rate of Related Sensitive Diseases

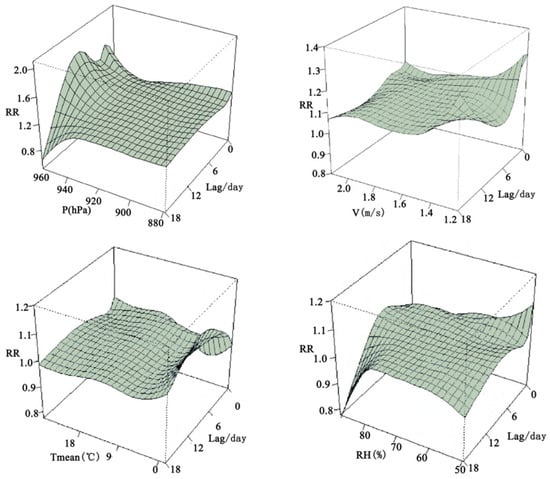

The study selected median indicators such as air pressure (912 hPa), wind speed (1.7 m/s), temperature (13.5 °C) and relative humidity (72.3%) as reference standards for the sample mean and measured the lagged effects of each factor on respiratory system diseases. Figure 7 shows the hysteresis effect RR curve of average air pressure, wind speed, temperature and relative humidity. The average air pressure in the figure is mainly manifested as a high-pressure effect with two lagged peaks. The impact of low pressure on respiratory diseases is manifested as a smaller immediate effect, and the intensity of the impact is not as strong as the former. From the lag effect results of average wind speed, both extremely low and extremely high wind speeds exhibit a certain degree of immediate effect, but the overall RR value is relatively small, indicating that the lag effect is not significant. The impact of average temperature on respiratory diseases is mainly reflected in the harm of low temperature and the overall RR values are relatively small, indicating that the lag effect is not significant. Relative humidity mainly manifests as the hazard of low humidity and there are two peak values of delayed danger. The first peak appears about 3–5 days after the delay and the second peak appears about 8–15 days after the delay. However, in high-humidity environments, the lag effect of respiratory diseases in the Yangtze River Delta region is not significant. Studies have shown that changes in relative humidity can have an impact on the reproduction of viruses or bacteria, thereby further inducing respiratory diseases [49].

Figure 7.

RR surface distribution of lagged effects of meteorological factors on respiratory diseases in the Yangtze River Delta region from 2018 to 2024.

Due to differences in the sources and characteristics of atmospheric pollutants, urban population distribution and population lifestyles, the exposure feedback effects of primary pollutants on non-accidental, respiratory and circulatory system mortality vary among different cities. The results indicate that there is an approximately linear relationship between PM2.5 exposure feedback and mortality. As PM2.5 concentration increases, the risk of mortality from respiratory and circulatory system diseases also increases, but there is no clear threshold. There is a positive correlation and cumulative lag between PM2.5 concentration and mortality risk. For every 10 μg/m3 increase in PM2.5, the lag effect on respiratory diseases increases by 0.82% over the lag period of 15 days. The cumulative lag effect of PM2.5 on non-accidental and circulatory system diseases has decreased in the central and southern regions of the Yangtze River Delta, while remaining unchanged or increasing in other cities. Eastern coastal cities still have the highest relative risk, with a cumulative lag increase of 0.93% and 0.71% in non-accidental and cardiovascular disease mortality rates for every 10 μg/m3 increase in PM2.5 over the lag period of 15 days, respectively, compared to a single-day lag increase of 0.06% and 0.04%.

4.3. Cumulative Lag Effect of Relative Humidity on Respiratory Diseases Showing a V-Shaped Change over Time

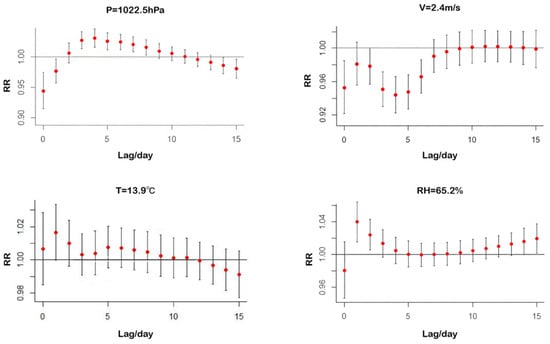

Based on the above analysis, we chose to observe the extreme values of various factors at the 98% percentile, namely air pressure at 1022.5 hPa, wind speed at 2.4 m/s, temperature at 13.9 °C and relative humidity at 65.2%, to explore the impact characteristics of various meteorological factors on respiratory diseases under extreme conditions. As shown in Figure 8, high pressure mainly has a significant inducing effect on respiratory diseases at a lag of 4 days, and the highest risk occurs at a lag of 6 days, with a significant cumulative lag effect. When the wind speed is 2.4 m/s, its impact on diseases is not significant, but in lower wind speed environments (i.e., less than 0.7 m/s), it has a significant impact on respiratory system diseases. Appropriate wind speed is beneficial for reducing pollutant concentration and has an inhibitory effect on respiratory diseases. The lag effect of relative humidity shows a ‘V-shaped’ change over time, and as the lag time increases, the cumulative disease effect becomes more pronounced. Low-humidity weather has a significant lag effect on respiratory diseases in the Yangtze River Delta region. Studies have shown that in high-humidity environments, the reproductive function of viruses or bacteria is continuously enhanced, which has a significant inducing effect on respiratory diseases [49,50].

Figure 8.

The trend of RR values of meteorological factors in the Yangtze River Delta region from 2018 to 2024 as a function of lag time (P is air pressure, V is wind speed, T is air temperature and RH is relative humidity).

In recent years, with the continuous development of environmental epidemiological research, scholars have developed the ‘Integrated Exposure Response’ model to assess the relative risk of PM2.5 comprehensive exposure [46]. This model integrates multi-channel pollution source information such as atmospheric air pollution, household cooking fuel combustion and smoking pollution, and integrates research results obtained at lower exposure concentrations with research results obtained at high exposure concentrations [47]. Some studies have also proposed a ‘concentration response’ function for long-term exposure to PM2.5, namely the global exposure mortality model, which explains the cumulative lag effect of air pollution on residents’ health [48,49].

4.4. Synergistic Health Effect Between Specific Meteorological Conditions and Pollutants During the Same Period

Table 9 presents the synergistic analysis results of meteorological conditions and pollutants in the Yangtze River Delta region from 2018 to 2024, quantifying the correlation between PM2.5, SO2 and NO2 and mortality rates from respiratory and circulatory system diseases. The results include correlation indicators, significance tests, standard deviations and other information. Among them, β1, β2 and β3 represent the main correlation degree between meteorological factors and major pollutants, as well as the health effect coefficient produced by their synergistic effect. Their main correlation degree and synergistic effect have passed the significance test and have statistical significance (p < 0.05).

Table 9.

The synergistic analysis results of meteorological conditions and pollutants in the Yangtze River Delta region from 2018 to 2024.

A significant impact on respiratory diseases in the Yangtze River Delta region is the synergistic effect between temperature and NO2, relative humidity and SO2. Under the conditions of low temperature and high-concentration NO2, the mortality rate of respiratory diseases significantly increases, and the impact characteristics on different populations are basically consistent. Under the conditions of low temperature and high-concentration NO2, the mortality rate of circulatory system diseases in the Yangtze River Delta region has significantly increased and the number of deaths gradually increased with the decrease in relative humidity. Winter meteorological conditions are more prone to creating polluted weather, and under such conditions the synergistic effect of the two can increase the impact on respiratory diseases. Even with low NO2 concentrations, there are still more deaths from respiratory diseases in the Yangtze River Delta region, which is related to the generally good air quality and low adaptability of residents to pollutants [50].

Some scholars internationally have conducted comparative analysis on the exposure levels and risks of atmospheric environmental pollution [51]. The long-term changes in environmental air quality have formed a regional pollution exposure pattern. Scholars have calculated that in 2024, approximately 43.67% of the global population will have been exposed to high concentrations of PM2.5 pollution based on county-level population data. The results indicate that the current air pollution problem is still severe with a wide range of impacts and the harm to human health cannot be ignored. There are also studies showing that changes in the exposure distribution of short-term pollutants reflect the effectiveness of emergency emission control measures and the trend of changes in the frequency of heavy pollution days. From 2013 to 2023, the frequency of severe PM2.5 pollution decreased by a total of 1190 times, and major air pollutants were well restricted [52,53].

5. Conclusions

This study analyzed the spatiotemporal evolution patterns of major air pollutants over the past decade. Based on mathematical models, a quantitative ‘dose–response’ relationship was fitted among meteorological factors, air pollution factors and mortality rates of sensitive diseases within the region. The main conclusions are mentioned below.

5.1. Key Findings

(1) Based on the trend of changes over the past decade, the overall pollution level in the Yangtze River Delta region has gradually decreased, but there is significant spatial heterogeneity in the distribution of PM2.5 concentration. The overall performance exhibits differentiated distribution characteristics, with higher levels in the eastern coastal areas and lower levels in the central and western inland areas, as well as higher levels in the southern areas and lower levels in the northern areas.

(2) The synergistic effect of temperature and NO2, as well as relative humidity and SO2, has a significant impact on the mortality rate of sensitive diseases. Under the combined conditions of low temperature and high NO2 concentration, the number of deaths from respiratory diseases increased significantly, with women and people over 56 years of age being highly sensitive groups. Under the combined conditions of low humidity and high concentrations of SO2, the number of deaths from circulatory system diseases increased significantly. Among them, people under 12 years of age were the most susceptible population.

(3) High pressure had a significant inducing effect on respiratory diseases after a lag of 4 days and the risk was highest at a lag of 6 days, indicating a certain cumulative lag effect. The impact of wind speed of 2.4 m/s on diseases was not significant, but in lower wind speed environments, specifically when less than 0.7 m/s, it had a significant impact on respiratory diseases. The lag effect of relative humidity exhibited a ‘V’-shaped variation over time and low-humidity weather had a significant lag effect on respiratory diseases in the Yangtze River Delta region.

(4) The cumulative lag effect of pollutants was evident. For every 10 μg/m3 increase in PM2.5, the probability of non-accidental and circulatory system disease deaths increased by 0.93% and 0.71% over the lag period of 15 days, which was 0.06% and 0.04% higher compared to single-day lag, respectively. There was a positive correlation between PM2.5 concentration and mortality risk, and the effect exhibited cumulative lag; that is, for every 10 μg/m3 increase in PM2.5, the lagged impact on respiratory diseases increases by 0.82% over the lag period of 15 days.

5.2. Implications

This study systematically reveals the complex synergistic health effects between meteorological conditions and air pollutants in the Yangtze River Delta region, which holds policy implications and public health significance. Firstly, the spatial heterogeneity and lag effect of PM2.5 and ozone as major pollutants indicate that the regional joint prevention and control mechanism should be strengthened, especially in high-pollution agglomeration areas around coastal and provincial capitals. Secondly, the significant impact of combinations such as temperature and NO2, as well as relative humidity and SO2 on respiratory and circulatory diseases, suggests that future health risk warning systems should comprehensively consider the interaction between meteorological and pollution factors rather than relying solely on single indicators for judgment. Furthermore, the study emphasizes that women, elderly individuals (aged ≥ 55) and children (aged ≤ 12) constitute high-risk and sensitive populations and should be the primary targets of environmental health interventions.

5.3. Limitations and Future Research Directions

Although this study reveals the synergistic health effects of meteorology and pollution at the regional scale, there are still certain limitations. Firstly, health data primarily relies on official statistical yearbooks without considering population mobility, individual exposure differences and socioeconomic backgrounds, which may underestimate the actual health risks. Secondly, the model treats PM2.5 and ozone as independent variables without delving into their potential interaction mechanisms. Due to limitations in data collection, the list of pollutants investigated in this article does not include some compounds known to be crucial for human health. For example, formaldehyde is a strong respiratory irritant and carcinogen, and urban air may contain relatively high concentrations of this compound. We will include carbonyl compounds such as formaldehyde in future research to more comprehensively assess urban air health risks. Due to the data collection period of 8:00–22:00, there may be missing data on nitrate secondary particulate matter and nighttime emissions pollution, which may underestimate the true health effects of nighttime exacerbations such as asthma. We will use continuous automatic monitoring technologies such as TEOM–FDMS in future research, combined with fixed stations and mobile monitoring, to comprehensively capture the health impacts of pollution gradients at night and day.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, C.C. and Y.C.; Data curation, Y.C.; Formal analysis, J.C.; Methodology, J.C.; Visualization, F.W., J.C. and C.C.; Writing—original draft, C.C.; Writing—review and editing, Y.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the General Project for Philosophy and Social Science Research in Jiangsu Province’s Universities (Grant No.2025SJYB0560), the 2025 Jiangsu Education Science Planning on Youth Special Project (Grant No.C-2025-01-66), the Jiangsu Social Science Fund Project (Grant No.22ZXC008), the 2025 Jiangsu Disabled Persons’ Federation Research Project (Grant No.2025SC02002) and the 2024 Jiangsu Province Social Science Application Research Boutique Project Social Education Special Project (Grant No.24SJA-121).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to the data involves the personal privacy and identity information of the investigated individuals.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Deng, Y.; Wang, J.; Sun, L.; Wang, Y.; Chen, J.; Zhao, Z.; Wang, T.; Xiang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Chen, J.; et al. Effects of ambient O3 on respiratory mortality, especially the combined effects of PM2.5 and O3. Toxics 2023, 11, 892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, G.; He, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Dou, P.; Dai, S. PM2.5 Spatiotemporal Evolution and Drivers in the Yangtze River Delta between 2005 and 2015. Atmosphere 2019, 10, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ao, Z.; Wang, H.; Zhang, Y.; Li, L.; Ke, Y.; Wu, Z.; Peng, Z. Online Observation of PM2.5 during a Persistent Haze in the Yangtze River Delta: Chemical Components, Health Effect and Light Extinction. Atmos. Pollut. Res. 2025, 16, 102695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dominski, F.H.; Branco, J.; Buonanno, G. Effects of air pollution on health: A mapping review of systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Environ. Res. 2021, 201, 111487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.J.; Xia, S.Y.; Yang, Y.; Wu, J.F.; Zhou, Y.N.; Ren, Y.W. Spatiotemporal Dynamics and Impacts of Socioeconomic and Natural Conditions on PM2.5 in the Yangtze River Economic Belt. Environ. Pollut. 2020, 11, 114569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maji, K.J.; Ye, W.F.; Arora, M. Ozone pollution in Chinese cities: Assessment of seasonal variation, health effects and economic burden. Environ. Pollut. 2019, 247, 792–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peralta, A.H.D.; Gavidia-Calderón, M.; Andrade, M.F. Future ozone levels responses to changes in meteorological conditions under RCP 4.5 and RCP 8.5 scenarios over São Paulo, Brazil. Atmosphere 2023, 14, 626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Barroso, G.; Sanz-Calcedo, J.G. Application of predictive maintenance in hospital heating, ventilation and air conditioning facilities. Emerg. Sci. J. 2019, 3, 337–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, S.; Zhang, X.; Gao, Z.; Li, Y.; Wang, J. Evaluation of atmospheric circulations for dynamic downscaling in CMIP6 models over East Asia. Clim. Dyn. 2023, 60, 2437–2458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fann, N.L.; Nolte, C.G.; Sarofim, M.C. Associations between simulated future changes in climate, air quality, and human health. JAMA Netw. Open 2021, 4, e2032064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, C.R.; Liu, H.Y.; Li, Y.F. Socioeconomic Drivers of PM2.5 in the Accumulation Phase of Air Pollution Episodes in the Yangtze River Delta of China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2016, 13, 928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Li, Y.; Zhu, B.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, H.; Liu, X. What have we missed when studying the impact of aerosols on surface ozone via changing photolysis rates? Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2023, 20, 10831–10844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Sokolov, A.; Schlosser, C.A. A large ensemble global dataset for climate impact assessments. Sci. Data 2023, 10, 801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, N.; Li, R.; Xu, C.; Chen, J.; Wang, L.; Zhang, Y. Ground ozone variations at an urban and a rural station in Beijing from 2006 to 2017: Trend, meteorological influences and formation regimes. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 235, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chien, L.; Chen, Y.; Yu, H.; Lin, Y.; Hsu, S. Lagged influence of fine particulate matter and geographic disparities on clinic visits for children’s asthma in Taiwan. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demarco, A.; Amoatey, P.; Khaniabadi, Y.O. Mortality and morbidity for cardiopulmonary diseases attributed to PM2.5 exposure in the metropolis of Rome, Italy. Eur. J. Intern. Med. 2018, 57, 49–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dehghan, A.; Khanjani, N.; Bahrampour, A. The relation between air pollution and respiratory deaths in Tehran, Iran—Using generalized additive models. BMC Pulm. Med. 2018, 18, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, G.; Zheng, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Tong, D.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, X.; He, K.; Liu, Y. Drivers of PM2.5 air pollution deaths in China 2002–2017. Nat. Geosci. 2021, 14, 645–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Q.; Wang, W.; Chen, C.; Xu, D.; Li, J. Acute effect of multiple ozone metrics on mortality by season in 34 Chinese counties in 2013–2015. J. Intern. Med. 2018, 283, 481–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, R.; Zhao, J.; Liu, Y.; Wu, J.; Li, S.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Gu, B.; Ju, X.; Gao, S.; et al. Air quality and health co-benefits of China’s carbon dioxide emissions peaking before 2030. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasilakos, P.N.; Shen, H.; Mehdi, Q. US clean energy futures—Air quality benefits of zero carbon energy policies. Atmosphere 2022, 13, 1401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Zhou, J.; Han, R.; Liu, Y.; Wang, Y. Association of short-term co-exposure to particulate matter and ozone with mortality risk. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2023, 57, 15825–15834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, M.Z.; Do, V.; Liu, S. Short-term PM2.5 and cardiovascular admissions in NY State: Assessing sensitivity to exposure model choice. Environ. Health 2021, 20, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB 3095-2012; Ambient Air Quality Standards. Ministry of Environmental Protection of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2012.

- Wang, J.; Li, J.; Li, X.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, H. Characteristics of air pollutants emission and its impacts on public health of Chengdu, Western China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 16852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, B.; Wang, T.; Ma, D.; Li, S.; Chen, J. Impacts of regional emission reduction and global climate change on air quality and temperature to attain carbon neutrality in China. Atmos. Res. 2022, 279, 106384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, M.; Sbihi, H.; Pan, X.; Chen, J.; Li, W. Modifiers of the effect of short-term variation in PM2.5 on mortality in Beijing, China. Environ. Res. 2020, 183, 109066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Hong, S.; Mu, H.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, J. Ozone exposure and health risks of different age structures in major urban agglomerations in People’s Republic of China from 2013 to 2018. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 42152–42164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pothirat, C.; Chaiwong, W.; Liwsrisakun, C. The short-term associations of particulate matters on non-accidental mortality and causes of death in Chiang Mai, Thailand: A time series analysis study between 2016–2018. Int. J. Environ. Health Res. 2021, 31, 538–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, Y.; Wang, T.; Cai, Y.; Liu, X.; Zhou, M. Influence of atmospheric particulate matter on ozone in Nanjing, China: Observational study and mechanistic analysis. Adv. Atmos. Sci. 2018, 35, 1381–1395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, Y.; Wang, T.; Yuan, C.; Li, S.; Zhang, H. The underlying mechanisms of PM2.5 and O3 synergistic pollution in East China: Photochemical and heterogeneous interactions. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 873, 162434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juginović, A.; Vuković, M.; Aranza, I. Health impacts of air pollution exposure from 1990 to 2019 in 43 European countries. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 22516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, M.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, H.; Liu, Y.; Wang, T. On the relevancy of observed ozone increase during COVID-19 lockdown to summertime ozone and PM2.5 control policies in China. Environ. Sci. Technol. Lett. 2021, 8, 289–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khomenko, S.; Cirach, M.; Pereira-Barboza, E.; Mueller, N.; Barrera-Gómez, J.; Rojas-Rueda, D.; Nieuwenhuijsen, M. Health impacts of the new WHO air quality guidelines in European cities. Lancet Planet. Health 2021, 5, e764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Chen, D.; Zhao, C.; Zhang, S.; Wang, J. Influence of meteorological conditions on PM2.5 concentrations across China: A review of methodology and mechanism. Environ. Int. 2023, 139, 105558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, B.; Zhou, J.; Ma, Y.; Li, X.; Wang, H. Association between atmospheric particulate matter and emergency room visits for cerebrovascular disease in Beijing, China. J. Environ. Health Sci. Eng. 2022, 20, 293–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, J.; Tong, D.; Zhang, Q.; Zheng, Y.; Wang, S. Pathways of China’s PM2.5 air quality 2015–2060 in the context of carbon neutrality. Natl. Sci. Rev. 2021, 8, nwab078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamkiewicz, L.; Maciejewska, K.; Rabczenko, D. Ambient particulate air pollution and daily hospital admissions in 31 cities in Poland. Atmosphere 2022, 13, 345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albahar, S.; Li, J.; Zaabi, A.; Almaskari, P.; Ahmed, A. Air pollution and respiratory hospital admissions in Kuwait: The epidemiological applicability of predicted PM2.5 in arid regions. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 5998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xi, M.; Luo, Y.; Li, Y.; Ma, D.; Feng, L.; Zhang, S. Comprehensive analysis of prevailing weather patterns and high-impact typhoon tracks to reveal where and how tropical cyclone affects regional ozone pollution in the yangtze river delta region, China. Atmos. Environ. 2025, 361, 121498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Li, D.; Zhou, L.; Wang, T.; Chen, J. Health impact attributable to improvement of PM2.5 pollution from 2014–2018 and its potential benefits by 2030 in China. Sustainability 2021, 13, 9690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Shi, H.; Ni, T.; Ma, D.; Fu, J.; Qi, Y. A quantitative exploration of the interactions and synergistic driving mechanisms between factors affecting regional air quality based on deep learning. Atmos. Environ. 2023, 12, 314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badida, P.; Krishnamurthy, A.; Jayaprakash, J. Meta-analysis of health effects of ambient air pollution exposure in low- and middle-income countries. Environ. Res. 2023, 216, 114604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, J.L.; Hu, J.C.; Xu, B.H.; Hu, X.L.; Sun, P.; Har, W.L.; Gu, Z.P.; Yu, X.M.; Wu, M.H. Characteristics and Seasonal Variation of Organic Matter in PM2.5 at a Regional Background Site of the Yangtze River Delta Region, China. Atmos. Environ. 2015, 123, 288–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, M.; Wei, J.; Zhang, S.; Liu, Y.; Wang, H. Short-term air pollution exposure associated with death from kidney diseases: A nationwide time-stratified case-crossover study in China from 2015 to 2019. BMC Med. 2023, 21, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, C.; Li, T.; Sun, Q.; Wang, L.; Zhang, Y. Short-term exposure to ozone and cause-specific mortality risks and thresholds in China: Evidence from nationally representative data, 2013–2018. Environ. Int. 2023, 171, 107666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Lin, J.; Niu, Y.; Zhang, H.; Liu, M. Impact of ozone exposure on heart rate variability and stress hormones: A randomized-crossover study. J. Hazard. Mater. 2022, 421, 126750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, P.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, K.; Li, S.; Chen, J. Health impacts and cost-benefit analyses of surface O3 and PM2.5 over the US under future climate and emission scenarios. Environ. Res. 2019, 178, 108687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Y.; Qu, W.; Lu, J.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, S. Responses of hydrological processes under different shared socioeconomic pathway scenarios in the Huaihe River Basin, China. Water 2021, 13, 1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, R.; Ma, Q.; Zhang, Q.; Li, W.; Wang, T. Coordinated effects of energy transition on air pollution mitigation and CO2 emission control in China. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 841, 156482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, J.; Qian, J.; Chen, J.; Li, S.; Wang, J.; Yao, M.; Du, Q. Modification effects of regional temperature and humidity on the relationship between daily mortality and short-term coexposure to fine particulate matter and ozone. Atmos. Environ. 2025, 358, 121369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, P.; Jin, P.; Yang, Y.; Wang, Q. Evaluating Urbanization and Spatial-Temporal Pattern Using the DMSP/OLS Nighttime Light Data: A Case Study in Zhejiang Province, Yangtze River Delta. Math. Probl. Eng. 2016, 7, 9850890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Yan, X.; Li, Y.; Zhang, S. Temporal-Spatial Evolution of PM2.5 and Driving Factors in Yangtze River Delta Urban Agglomeration. Resour. Environ. Yangtze Basin 2020, 29, 1497–1506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).