Abstract

The East Asian winter monsoon (EAWM) is a critical component of the boreal winter global climate system, exerting profound influences on weather and climate anomalies across East Asia. This study systematically evaluates the capability of 15 Coupled Model Intercomparison Project Phase 6 (CMIP6) models in simulating the typical associated circulation, temporal characteristics, and the relationship with the El Niño–Southern Oscillation (ENSO) during the historical period of 1951–2013. Results indicate that the multi-model ensemble demonstrates considerable fidelity in reproducing the climatological spatial patterns of key EAWM systems, including the Siberian High, Aleutian Low, and low-level meridional winds. However, a systematic eastward shift is identified in the simulated sea level pressure anomaly centers over the North Pacific. In terms of temporal variability, most models realistically capture the dominant interdecadal periodicity of 15–20 years found in observations after 11-year low-passed filter. Four models reproduce a similar bimodal periodicity. Regarding the ENSO–EAWM relationship, approximately 80% of the evaluated models successfully capture the observed negative correlation, although its strength is consistently underestimated across the model ensemble. More notably, only three CMIP6 models faithfully capture the observed intrinsic asymmetry in the ENSO–EAWM relationship (i.e., the stronger impact of El Niño compared to La Niña).

1. Introduction

The East Asian winter monsoon (EAWM), a critical component of the boreal winter global climate system [1,2,3], significantly influences weather and climate anomalies across East Asia. The EAWM comprises several systems: the surface cold Siberian High and warm Aleutian Low, low-level northerlies or northeasterlies along the East Asian coast, the mid-tropospheric East Asian trough, and the upper-tropospheric East Asian jet stream [2,4,5]. An anomalously intensified EAWM tends to facilitate more frequent cold surges, which can trigger extreme weather events including low-temperature damage, prolonged snowfall, and severe cold spells [1,6,7].

EAWM variability is complex due to its extensive meridional coverage and the combined effects of multiple, region-specific drivers, which have been a central focus in extensive research. Existing observation analyses have demonstrated that the EAWM exhibits pronounced interannual variability linked to El Niño–Southern Oscillation (ENSO) [2,8] and interdecadal variability associated with the Pacific Decadal Oscillation (PDO) [9,10,11], the Arctic Oscillation (AO) [12,13], thermal conditions over the Tibetan Plateau [14] and so on. Furthermore, high-latitude climate variations, including Eurasian snow cover and the Siberian High, exert significant influences on it [15]. Despite extensive related research, the mechanisms underlying the EAWM’s multi-scale variability remain subject to persistent uncertainty, stemming from the inherent limitations in observational records and the entangled effects of intrinsic climate variability and external forcings in the reanalysis datasets. The ENSO–EAWM relationship has attracted considerable attention as well. Statistically, ENSO and EAWM exhibit a significant out-of-phase relationship. The East Asian Winter Monsoon tends to be weak during El Niño years, whereas it is stronger during La Niña years. The ENSO–EAWM teleconnection was primarily mediated by the Western North Pacific anomalous anticyclone/cyclone system, with its accompanying meridional wind anomalies establishing critical atmospheric pathways. However, this linkage is non-stationary and subject to nonlinear modulations by PDO and AO. Furthermore, extensive studies demonstrate that El Niño exerts a more pronounced influence on EAWM compared to La Niña events. Several perspectives have been advanced to elucidate this asymmetrical interaction. It has been proposed that asymmetries in the amplitude and longitudinal location of SST anomalies, as well as the interannual oscillation and background state in the western North Pacific (WNP), contribute substantially to this phenomenon [16,17,18].

Systematic research on the EAWM holds critical importance both societally and scientifically. Climate model simulation serves as a powerful tool for both enhancing comprehension of the physical processes and generating projections of future variability. While the simulation fidelity of summer monsoons in climate models has been extensively scrutinized, the evaluation of EAWM dynamics remains markedly understudied. Some deficiencies such as major trough and the zonal sea level pressure gradient exist in the simulation of the EAWM from CMIP5 outputs [19]. As to the ENSO–EAWM relationship, previous studies indicate that this changing ENSO–EAWM relationship can hardly be reproduced in CMIP5 models due to the complexity of EAWM interannual variability and the generally poor model performance in simulating the PDO [20]. Overall, the CMIP6 models reproduce the ENSO-EAWM teleconnection more realistically than the CMIP5 models, although they still somewhat underestimate the ENSO–EAWM relationship than observed [21]. An advanced evaluation of the distinct northern and southern modes of the EAWM and their separate linkages to ENSO in CMIP6 models has also been provided recently. The relationship between EAWM southern mode and ENSO depends on the position of the ENSO-related tripolar pattern of sea surface temperature (SST) anomalies in the tropical Indian and Pacific oceans. The strength of the Philippine anticyclone affects the northern mode [22]. Therefore, a systematic evaluation of CMIP6 models’ capability in simulating the EAWM characteristics is imperative.

Against this background, this study aims to conduct a systematic evaluation of the CMIP6 multi-model ensemble’s capability in simulating fundamental EAWM characteristics. We focus on the two core aspects: (1) the fidelity in reproducing the spatial patterns and absolute intensities of key EAWM systems and multi-scale variability; and (2) the crucial interannual ENSO–EAWM relationship. The rest of this paper is constructed as follows: the involved reanalysis dataset, models, index and methodology are introduced in Section 2. Section 3 evaluates the performance of CMIP6 models in simulating the circulation, period and EAWM–ENSO relationship. Summary and discussion are presented in Section 4.

2. Data and Method

2.1. Datasets

To evaluate the fidelity of EAWM characteristics, the monthly atmospheric variable including zonal winds, meridional winds, surface atmosphere temperature (SAT) and sea level pressure (SLP) with a 0.25° × 0.25° resolution from the fifth major global reanalysis produced by European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts (ERA5) [23] dataset was utilized in the study. Monthly Sea Surface Temperature (SST) data with a 1° × 1° resolution were obtained from Met Office Hadley Centre [24]. The time period for all the aforementioned datasets is from 1951 to 2013 and will be referred to as “observations” hereafter.

Historical simulations from 15 coupled climate models participating in the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project Phase 6 (CMIP6) are analyzed. The models used in this study are from major international modeling centers, ensuring the ensemble represents a sample of current-generation climate models in terms of physics and resolution. The data were downloaded from the Earth System Grid Federation node. The detailed information regarding the modeling centers and horizontal resolutions of these models is provided in Table 1. In contrast to Atmospheric Model Intercomparison Project experiments, the historical simulations focus on evaluating the fully coupled climate system under both anthropogenic and natural forcings. In addition, only the first ensemble member (r1i1p1f1) was analyzed to ensure a like-for-like comparison across the entire model ensemble.

Table 1.

List of 15 CMIP6 models utilized in this study with institutional sources and atmosphere resolution.

To ensure consistency in all subsequent analyses, both the observational/reanalysis and model data were regridded to a common 1° × 1° latitude-longitude grid using the bilinear interpolation method [25].

2.2. Index Definition

From the predictability perspective, the low-level wind field index can better characterize the interannual variability of the EAWM and its relationship with ENSO [26]. Therefore, the EAWM index is defined as the area-averaged December-January-February (DJF) mean 850-hPa meridional wind anomalies over the region (20–40° N, 100–140° E) [27]. In addition, following the standard climatological convention, the winter of a given year refers to the period from December of that year to February of the following year (e.g., “1970 winter” denotes DJF 1970/71). A sign convention was implemented by multiplying by −1, aligning positive index phases with enhanced EAWM intensity (i.e., strengthened cold-air advection via intensified northerlies). Overall, the specific data processing procedure was as follows. First, monthly 850-hPa meridional wind data were interpolated to a common 1° × 1° grid. For each grid point, monthly anomalies were computed by subtracting original values from the climatological mean for the entire study period. These grid-point anomalies were then area-averaged over the East Asian region to produce a monthly anomaly time series. Subsequently, seasonal means for DJF were calculated. The resulting raw index series was multiplied by −1. A linear least squares trend was removed from this derived index. Finally, the index was normalized prior to analysis.

The Niño3.4 index, adopted as the standard metric for ENSO intensity quantification, is calculated as the seasonal average (December–February) of SST anomalies within the Niño3.4 domain (5° S–5° N, 170–120° W). An ENSO event was identified when the Niño3.4 index reached or exceeded ±0.5 standard deviations.

2.3. Methods

In order to cover as much of the common period as possible between ERA5 and the CMIP6 historical experiment, we evaluated the characteristics of the EAWM based on the period 1951–2013 in this study. The application of a unified criterion for defining the EAWM and ENSO indices enables an objective assessment of model performance, both inter-model and against observations.

An 11-year low-pass Lanczos filter was applied to investigate decadal-scale variability to the indices [28]. Compared with a running-mean result, the Lanczos filter more effectively isolates the pure interannual signals from the decadal-scale signals.

The primary metric for assessing the ENSO–EAWM relationship is Pearson’s linear correlation coefficient. The statistical significance of correlation and regression results was assessed using a two-tailed Student’s t-test. To account for autocorrelation, which reduces the number of independent samples, the effective sample size () was calculated [29]. Additional statistical analyses, including regression and power spectrum analysis, were also employed to elucidate the characteristics of the EAWM system. Finally, a multi-model ensemble (MME) mean was computed by arithmetically averaging the outputs from all 15 CMIP6 models with equal weight. The MME is used to represent the collective performance of the current generation of climate models. All data were linearly de-trended before statistical analysis to isolate the internal variability of the climate system and minimize the influence of external forcings.

3. Results

3.1. Fidelity in EAWM Characteristics

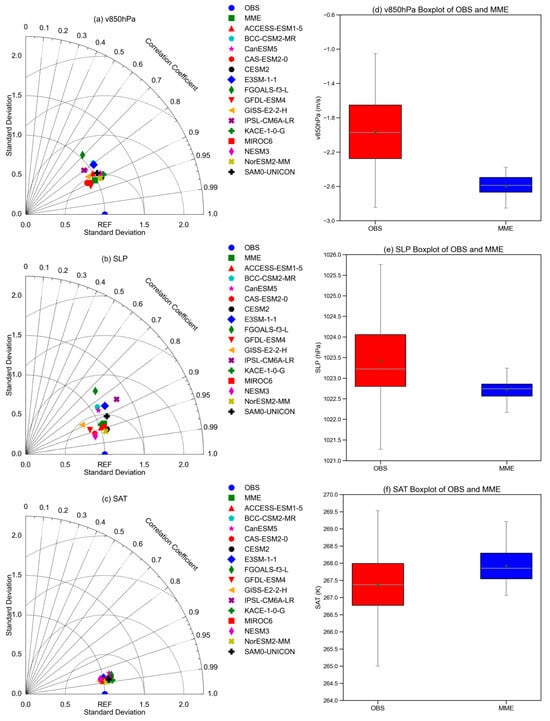

As the EAWM is a key system influencing winter climate over the East Asian coastal region associated with strong surface northerly winds, the zonal pressure contrast between the Siberian high and the Aleutian low, critical climatic elements such as meridional wind, SLP and SAT were evaluated first. To evaluate the models’ performance in simulating EAWM climatology, we constructed Taylor diagrams for the East Asian domain—a widely used tool for model assessment. The CMIP6 ensemble demonstrates substantial fidelity in replicating the wintertime 850 hPa meridional wind and SLP fields across East Asia, evidenced by high pattern correlation coefficients (generally greater than 0.8). Most models exhibit larger standard deviations than the observations. For SAT elements, most of the corresponding correlation coefficients exceed 0.95 and the intermodel spread is small. While the Taylor diagram effectively reflects the resemblance of spatial patterns, it does not convey information about absolute intensities. Therefore, we further quantify the intensity of several EAWM-related systems using boxplots, focusing on their mean, median values and so on. The MME v-wind over East Asia has stronger intensity than in observation (Figure 1d). The dispersion of both the v-wind field and SLP in the MME is significantly smaller than in the observations. For the model-simulated SAT, aside from the mean and median being slightly higher than observations (less than 0.5 K), dispersion shows little difference from the observations, which is consistent with the Taylor diagram. The high simulation fidelity in representing the climatological variables over East Asia serves as a critical prerequisite for the faithful representation of the EAWM system.

Figure 1.

(a–c) Taylor diagram and (d–f) box plots of winter (DJF) climatology average (a) 850 hPa meridional winds, (b) SLP, (c) SAT over East Asia (region information: 20° N–60° N, 100–140° E) for ERA5, MME and 15 models. The left red box displays the climatological mean and ±1 standard deviation derived for the ERA5 reanalysis. The right blue box indicates the climatology of the MME and intra-model standard deviation and upper and lower bars for maximum and minimum values. The green triangle of the boxplot represents the median of the data.

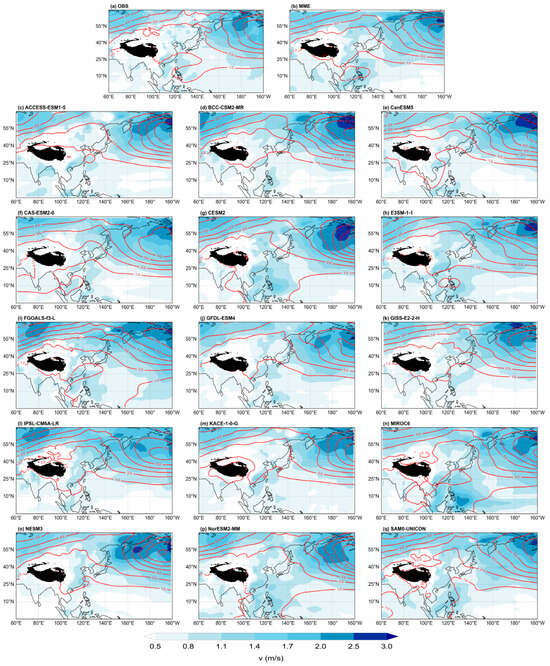

In addition, the interannual standard deviations of DJF-mean 850 hPa meridional winds and SLP are employed to quantify the intensity of interannual variability linked to the EAWM in Figure 2 for observation and 15 models. In addition to the significant signals at high latitudes, V850 exhibits strong interannual variability over southern China, the South China Sea, and the adjacent western North Pacific (Figure 2a). This variability is linked to the anomalous circulation near the Philippine Sea, which typically related with ENSO modulating the EAWM. Three models (CESM2, MIROC6 and NorESM2-MM) overestimate it compared to observations, most notably MIROC6. Furthermore, most models skillfully reproduce the observed pattern of SLP variability, differing only slightly in magnitude. They consistently capture its pronounced strength around the Aleutian Low and its relatively weaker strength over the Siberian High. The MME effectively captures the spatial patterns of interannual variability for both V850 and SLP (Figure 2b).

Figure 2.

The interannual standard deviations of winter mean 850 hPa meridional winds (shading, units: m s−1) and SLP (contours, units:1 hPa) for the (a) observation, (b) MME and (c–q) the 15 models.

In addition to evaluating the correlation and interannual variability of key elements, it is crucial to evaluate the EAWM-related circulation anomalies as defined by the EAWM index in the models. The time series, 11-year low-pass-filtered of normalized EAWM index and associated atmospheric system in observation during 1951–2013, is shown in Figure 3. The EAWM exhibits pronounced both interannual variability and a phase shift around 1985/86, which is consistent with previous studies [10,30,31,32]. In the observation (Figure 3a), a positive EAWM index corresponds to a distinct west–east pressure gradient in the SLP field, characterized by a strengthened Siberian High and a weakened Aleutian Low. This pressure pattern is associated with a meridional wind anomaly structure that aligns with the northerly anomalies along the East Asian coast. Furthermore, a strong EAWM phase corresponds to below-normal surface air temperatures over East Asia alongside positive temperature anomalies over northern Eurasia. The CMIP6 historical simulations demonstrate a generally realistic reproduction of EAWM-related surface thermal conditions, atmospheric circulation, and SLP anomalies, yet exhibits an eastward shift in North Pacific SLP variance center. The prevalent excessive westward extension of the equatorial Pacific cold tongue in models distorts the tropical forcing of extratropical Rossby waves. An altered Rossby wave source can systematically shift the phase of the wave train affecting the North Pacific, thereby displacing the SLP centers [21]. Notably, the underestimation of wind anomalies linked to the EAWM index has improved compared to CMIP5, likely due to better representation of the EAWM index itself. And it has also been suggested that EAWM indices based on low-level wind can reduce the bias significantly [20].

Figure 3.

(a) The time series (bar) and 11-year low-pass-filtered (solid line) of normalized EAWM index from ERA5 (blue indicates negative values and red indicates positive values). (b,c) SLP (red line; units: hPa; solid lines denote positive values, and dashed lines denote negative values), SAT (shading, units: K), 850 hPa wind (vector, units: m s−1; scale at top right) anomalies obtained by regression onto the original normalized EAWM index from (b) ERA5 and (c) MME.

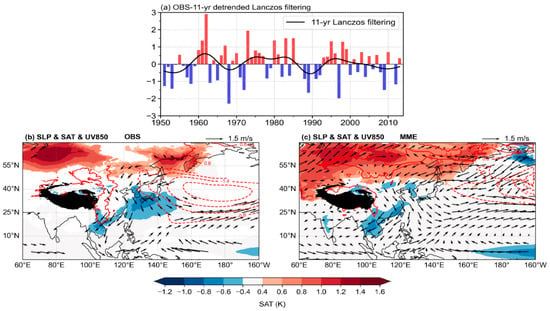

To assess the multi-scale temporal characteristics of the EAWM, we performed a spectral analysis of the EAWM index. As indicated in the bar chart of Figure 3a, the unfiltered spectral analysis reveals a significant interannual signal in the EAWM with a 3–6-year periodicity in observations, the MME and all of the model results. Although results from individual models vary slightly, the interannual signal maybe lined with ENSO remains the dominant component. In addition, the observational results reveal a statistically significant decadal periodicity of 12 years and 20 years (Figure S1a). This peak remains evident even in the spectrum derived from unfiltered data, where pronounced decadal variability coexists with interannual signals, confirming that the identified periodicity is not an artifact of the low-pass filtering procedure. The MME fails to reproduce the decadal variation without the 11-year filter. Only seven models successfully reproduce significant decadal variations with periods longer than ten years, though most exhibit relatively weak power spectral intensity. The power spectrum of 11-year filtered EAWM index is shown in Figure 4. After being 11-year low-filtered, 12 models successfully reproduce the period of approximately 15–20 years except BCC-CSM2-MR, GISS-E2-2-H and NorESM2-MM. Since the historical simulations incorporate both natural and anthropogenic forcings, the robust reproduction of this decadal signal across most models suggests that the EAWM’s low-frequency variability is likely intrinsic to the climate system. This implies that external forcings may modulate rather than fundamentally drive these decadal oscillations—a view further supported by the presence of significant decadal variations in extended pre-industrial control simulations. Additionally, a similar bimodal periodicity is reproduced in four of the fifteen CMIP6 models analyzed, including CAS-ESM2-0, CESM2, E3SM-1-1 and SAM0-UNICON.

Figure 4.

The power spectrum (black solid lines) of 11-year filtered EAWM index from (a) ERA5, (b) MME and (c–q) the 15 models. The red and blue solid lines indicate the noise spectrum and 90% confidence level threshold, respectively.

3.2. ENSO–EAWM Relationship

As the strongest interannual ocean-air signal, ENSO exerts great influence on the East Asia winter climate by an anomalous low-level anticyclone (cyclone) over the western North Pacific [33]. Consequently, in addition to the intrinsic characteristics of the EAWM, the ENSO–EAWM relationship constitutes a critical component of assessment. It is notable that the EAWM index based on the low-level or near-surface meridional wind exhibit superior fidelity in encapsulating the ENSO–EAWM relationship mechanism at interannual timescales [27].

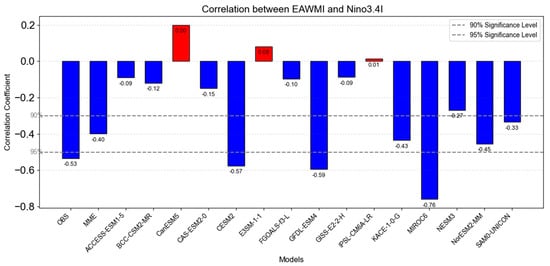

The correlation coefficients between the EAWM and Niño3.4 indices from observations, the 15 individual models, and their MME are summarized in Figure 5. The observed correlation is −0.53, significant at the 95% confidence level, whereas the MME result is weaker (−0.36). The slightly weaker negative correlation found in our observations, compared to previous studies, stems from our use of a longer time series that includes the 1970s—a period of weakened coupling in the ENSO–EAWM relationship [30]. The simulation results vary significantly among different models. While some models capture well the observed negative relationship between DJF Niño3.4 and EAWM indices, only three out of the 15 models (CESM2, GFDL-ESM4, and MIROC6) reproduce a statistically significant negative correlation. In contrast, three other models (CanESM5, E3SM-1-1, and IPSL-CM6A-LR) even simulate an incorrect positive correlation. This overall underestimation of the linkage strength across the model ensemble indicates a systematic bias in representing the observed ENSO–EAWM relationship.

Figure 5.

Correlation coefficients between the DJF-averaged EAWM index and Niño3.4 index in the observation, MME and 15 models during 1951–2013 (blue indicates negative and red indicates positive values). The two gray lines indicate the thresholds for correlations significant at the 90% and 95% confidence levels, respectively.

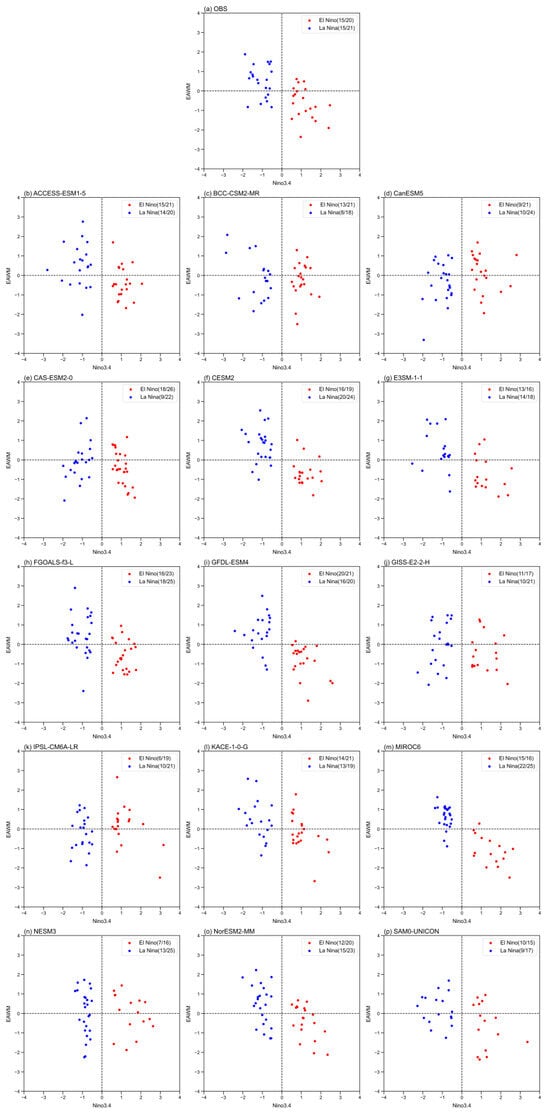

To further visualize the relationship, we present scatter plots of the normalized EAWM index against the Niño3.4 index for both observations and all models. The overall distribution, particularly from the observational data, clearly indicates a negative EAWM–ENSO tendency. The ratio of positive EAWM events occurring in El Niño years is comparable to that of negative EAWM events in La Niña years. An asymmetry becomes more apparent when considering only strong ENSO events exceeding the ±1 Niño 3.4 index threshold (Figure 6a), which is consistent with previous studies and operational forecasts [18,34,35,36]. Moreover, the observed scatter plot clearly shows a negative correlation. The models exhibit marked discrepancies in the performance. Specifically, several models show little difference in the magnitude of the EAWM across different ENSO phases. Only three models show the observed asymmetry in the ratio between the two phases.

Figure 6.

Scatter diagram of DJF-averaged normalized EAWM index against Niño3.4 index for the (a) observation and (b–p) 15 models. The values top-right correspond to the ratios of “El Niño-negative EAWM” events and “La Niña-positive EAWM” events, respectively. In the fraction, the denominator represents the total number of El Niño (La Niña) events, while the numerator indicates the number of concurrent negative (positive) EAWM events that occur simultaneously.

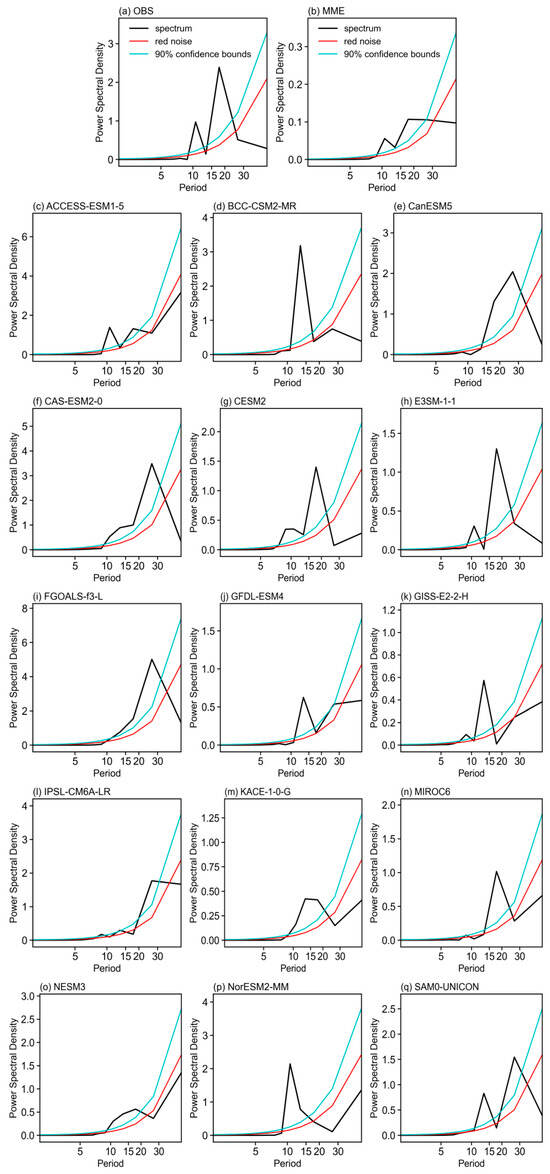

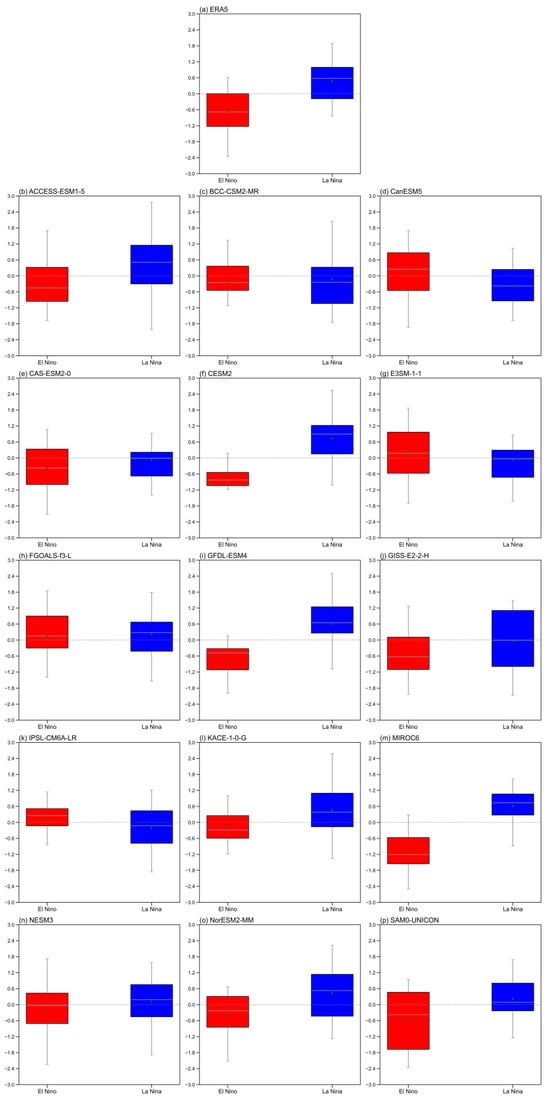

To quantitatively assess the feature, Figure 7 presents boxplots of the EAWM index during canonical El Niño and La Niña events from both ERA5 and the 15 CMIP6 models. Observations confirm this asymmetry: the composite EAWM index averages less than −0.6 during El Niño episodes but +0.5 during La Niña episodes, indicating that El Niño tends to induce a weaker EAWM, while the strengthening effect associated with La Niña is less pronounced. The models’ capability to replicate this observed relationship is limited. Only 8 out of the 15 models (ACCESS-ESM1-5, CESM2, GFDL-ESM4, KACE-1-0-G, MIROC6, NESM3, NorESM2-MM, and SAM0-UNICON) successfully capture the basic “El Niño–negative EAWM/La Niña–positive EAWM” dipole pattern. In contrast to observations, four models simulate a positive mean EAWM during El Niño years, while six models yield a negative mean EAWM during La Niña years. This discrepancy suggests that the more unstable nature of the La Niña–positive EAWM relationship poses a greater challenge for models to simulate accurately. More notably, just three of these models (CESM2, GFDL-ESM4, and MIROC6) with the highest correlation coefficients realistically reproduce the observed amplitude asymmetry between the two phases. A key systematic bias is evident, with over 70% of the models underestimating the magnitude of EAWM weakening during El Niño years. The systematic underestimation likely stems from model biases in simulating the tropical–extratropical teleconnection, ENSO asymmetry and so on, which still requires further verification [21,22].

Figure 7.

Box plot of the EAWM index in typical El Niño years (red bar) and La Niña (blue bar) years from (a) ERA5 and (b–p) 15 models. The gray error bands represent ±1 standard deviation of the EAWM index. The green triangle of the boxplot represents the median of the data.

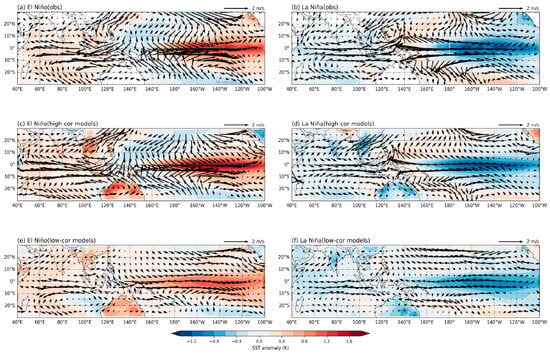

To identify the factors influencing the simulation performance of the aforementioned ENSO–EAWM asymmetry, we selected and categorized 15 CMIP6 models into high-correlation models (correlation coefficient higher than the observed value) and low-correlation models (positive correlation coefficient) based on the correlation coefficient between DJF Niño3.4 index and the EAWM index. To ensure balanced group sizes and to clearly differentiate the ENSO–EAWM relationships between them, the two correlation thresholds were selected accordingly. This classification resulted in three high-correlation and three low-correlation models. The composite anomalies of DJF SST and 850 hPa wind in El Niño and La Niña years in the observations, three high-correlation model ensembles and three low-correlation model ensembles are shown in Figure 8. In El Niño years, significant positive sea surface temperature (SST) anomalies develop over the tropical central-eastern Pacific and Indian Ocean, while negative SST anomalies prevail in the tropical western Pacific. During La Niña years, an approximately opposite but spatially similar SST anomaly pattern emerges, albeit with noticeable asymmetries in intensity and extent. Consistent with these SST patterns, a pronounced lower-tropospheric anomalous anticyclone (cyclone) is established over the Philippine Sea in El Niño (La Niña) years, respectively (Figure 8a,b). An anomalous anticyclone (cyclone) forms primarily due to suppressed (enhanced) convection over the tropical western North Pacific, which is triggered by sea surface temperature anomalies in the equatorial central-eastern Pacific. Additionally, a Rossby wave response to local SST anomalies in the region contributes to its development [37,38]. Ultimately, the southerly (northerly) anomalies along the western flank of this anticyclone (cyclone) directly modulate the intensity of the East Asian winter monsoon [8,34,37]. The three high-correlation model ensembles successfully reproduce the Philippine Sea anomalous anticyclone (cyclone) during El Niño (La Niña) years, albeit with a westward extension toward the North Indian Ocean (Figure 8c,d), while the low-correlation ensemble shows notable deficiencies. Not only are the tropical WNP SST anomalies substantially weaker than those in observations and the high-correlation ensemble, but the simulated anticyclone (cyclone) over the Philippine Sea is also notably weaker and displaced westward relative to observations.

Figure 8.

Composite anomalies of DJF SST (shading; unit: K) and 850 hPa wind (vector; unit: m/s; scale at top right) in (a,c,e) El Niño years and (b,d,f) La Niña years for (a,b) the observation, (c,d) 3three high-correlation model ensemble and (e,f) three low-correlation model ensemble.

4. Summary and Discussion

Utilizing the ERA5 reanalysis dataset and Hadley SST observational data, this study performs a comprehensive assessment of the spatiotemporal characteristics of the EAWM and its relationship with ENSO across 15 CMIP6 historical simulations during 1951–2013. Fifteen studied CMIP6 models were able to reproduce the climatic state of 850 hPa meridional winds, SLP and SAT over East Asia. For a clearer comparison of model performance, a table regarding the key diagnostics for the 15 CMIP6 models is provided (Table S1).

We first conducted a systematic evaluation of the climatology characteristics associated with the East Asian winter monsoon defined by 850 hPa meridional wind anomalies, including its spatial patterns, speed magnitude, and periodic characteristics. In general, 15 CMIP6 models demonstrate considerable capability in reproducing the climatological mean distribution and intensity of key EAWM system components, such as the Siberian High, Aleutian Low, and 850 hPa winds and SAT over East Asia. CMIP6 MME generally captures 850 hPa meridional wind patterns over East Asia. However, a systematic eastward shift bias persists in simulated SLP center. In addition to the abovementioned tropical Pacific SST bias, an overly zonal and eastward-shifted Kuroshio-Oyashio extension may also play a role. This displaced ocean front directly anchors an eastward-shifted storm track and mean SLP low center [39]. Assessments of EAWM simulations defined by different indices require future research for CMIP6 models. In terms of the multi-scale variations, all selected models robustly capture statistically significant interannual variability. Of 15 models, four also exhibit a discernible 10-year periodicity.

Given ENSO’s significant impact on EAWM interannual variability, the ENSO–EAWM relationship is examined in the selected CMIP6 models. The MME-simulated correlation between Niño3.4 index and EAWM index exceeds −0.3, statistically significant at the 90% confidence level. While 12 models simulate the correct negative sign of the ENSO-EAWM relationship, only six of them (CESM2, GFDL-ESM4, KACE-1-0-G, MIROC6, NorESM2-MM, SAM0-UNICON) achieve a statistically significant correlation comparable to observations. Three models (CESM2, GFDL-ESM4, MIROC6) produce a stronger negative correlation than observations, exceeding the 95% significance threshold. The maximum correlation coefficient is −0.74 in 15 models. Asymmetry in the ENSO–EAWM relationship constitutes another key assessment focus. Eight models reproduce distinct EAWM responses to ENSO warm/cold phases successfully, whereas only three models accurately capture the observed stronger impact during El Niño events. In addition, most models underestimate the EAWM weakening during El Niño events complements the work of Guo et al. [22], who identified biases in the zonal SST gradient for the southern mode.

Although the models demonstrate notable skill in replicating the climatological mean state of key EAWM systems and capturing its dominant decadal variability, their simulation of the observed ENSO–EAWM relationship and its asymmetries remains limited. This limitation may be influenced by multiple factors, including ENSO amplitude [20], the westward extension of ENSO-related SST anomalies in the equatorial Pacific [8], and the position of the associated tripolar SST pattern across the tropical Indian and Pacific oceans [22]. Further analysis is therefore required to understand the processes that affect the reproduction of EAWM conditions. To advance beyond this diagnostic identification of biases, future work should focus on the following aspects. Process-based comparisons between high- and low-performing models can be performed to pinpoint the minimal physics required for simulating the ENSO-EAWM asymmetry. The modulating role of internal decadal variability (e.g., PDO) should be explicitly evaluated using long control simulations. In addition, the results are based on the historical experiment from 15 models, and a broader range of models should be incorporated.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/atmos16121400/s1. Figure S1. The power spectrum (black solid lines) of nonfiltered EAWM index from (a) ERA5, (b) MME and (c–q) the 15 models. The red and blue solid lines indicate the noise spectrum and 90% confidence level threshold, respectively. Table S1. Summary of key diagnostics for the 15 CMIP6 models.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.T.; Methodology, Y.T. and M.L.; Software, M.L. and Y.T.; Validation, Y.T. and M.L.; Formal Analysis, Y.T. and M.L.; Writing—Original Draft Preparation, Y.T.; Writing—Review and Editing, Y.T. and M.L.; Project Administration, Y.T.; Funding Acquisition, Y.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The research presented in this paper was jointly funded by the Natural Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province (Grants No BK20240318) and Open Foundation of Plateau Atmosphere and Environment Key Laboratory of Sichuan Province.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Daily data of ERA5 reanalysis can be downloaded at https://cds.climate.copernicus.eu/datasets/reanalysis-era5-single-levels-monthly-means?tab=download (accessed on 31 October 2025). CMIP6 historical simulation data can be accessed at https://esgf-node.llnl.gov/search/cmip6/ (accessed on 31 October 2025). Monthly Sea Surface Temperature dataset from Met Office Hadley Centre can be obtained at https://www.metoffice.gov.uk/hadobs/hadisst/data/download.html (accessed on 31 October 2025).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Ding, Y. Monsoon Over China; Kluwer Academic: Norwell, MA, USA, 1994; p. 420. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, W.; Hans-F, G.; Huang, R. The interannual variability of EastEast Asian winter monsoon and its relation to the summer monsoon. Adv. Atmos. Sci. 2000, 17, 48–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Wang, L.; Feng, J.; Wen, Z.; Ma, T.; Yang, X.; Wang, C. Recent progress in studies of the variabilities and mechanisms of the East asian monsoon in a changing climate. Adv. Atmos. Sci. 2019, 36, 887–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, L.; Chen, W.; Wei, K. The interdecadal variation of winter temperature in China and its relation to the anomalies in atmospheric general circulation. Climatic Environ. Res. 2006, 11, 330–339. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, G.; Wang, W.; Sun, Z.; Li, Z. Atmospheric circulation cells associated with anomalous East Asian winter monsoon. Adv. Atmos. Sci. 2011, 28, 913–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.; Wang, Z.; Harry, H. The Asian winter monsoon. In The Asia Monsoon; Wang, B., Ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2006; pp. 89–127. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, J.; Wang, L.; Chen, W.; Fong, S.; Leong, K. Different impacts of two types of Pacific Ocean warming on Southeast Asian rainfall during boreal winter. J. Geophys. Res. 2010, 115, D24122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Wu, R.; Gong, H.; Jia, X.; Dai, P. What determine the performance of the ENSO-East Asian winter monsoon relationship in CMIP6 models? J. Geophys. Res. 2022, 127, e2021JD036227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.; Wang, X.; Zhou, T.; Li, C.; Chan, J. Interdecadal variability of the relationship between the East Asian winter monsoon and ENSO. Meteor. Atmos. Phys. 2007, 98, 283–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Y.; Liu, Y.; Liang, S.; Ma, X.; Zhang, Y.; Si, D.; Liang, P.; Song, Y.; Zhang, J. Interdecadal variability of the East Asian winter monsoon and its possible links to global climate change. J. Meteor. Res. 2014, 28, 693–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Qian, S.; Feng, G. A study of the winter recurrence mechanism of the temperatures in Northern East Asia. J. Trop. Meteor. 2018, 24, 49–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jhun, J.; Lee, E. A new East Asian winter monsoon index and associated characteristics of the winter monsoon. J. Clim. 2004, 17, 711–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, J.; Wang, T.; Wang, H.; Zhu, Y.; Sun, J. Interdecadal weakening of the east Asian winter monsoon in the mid-1980s: The roles of external forcings. J. Clim. 2018, 31, 8985–9000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; Sun, J.; Gao, Y. Effects of AO on the interdecadal oscillating relationship between the ENSO and East Asian winter monsoon. Int. J. Climatol. 2020, 40, 4374–4383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Y.H.; Krishnamurti, T.N. Heat budget of the Siberian high and the winter monsoon. Mon. Weather Rev. 1987, 115, 2428–2449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, B.; Li, T.; Zhou, T. Asymmetry of atmospheric circulation anomalies over the western North Pacific between El Niño and La Niña. J. Clim. 2010, 23, 4807–4822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Min, Q.; Su, J. Impact of El nino on atmospheric circulations over East Asia and rainfall in China: Role of the anomalous Western North Pacific anticyclone. Sci. China-Earth Sci. 2017, 60, 1124–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, J.; Chen, W.; Li, Y. Asymmetry of the winter extra-tropical teleconnections in the Northern Hemisphere associated with two types of ENSO. Clim. Dyn. 2017, 48, 2135–2151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, K.; Xu, T.; Du, Z.; Gong, H.; Xie, B. How well do the current state-of-the-art CMIP5 models characterize the climatology of the East Asian winter monsoon? Clim. Dyn. 2013, 43, 1241–1255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, H.; Wang, L.; Chen, W.; Wu, R.; Wei, K.; Cui, X. The climatology and interannual variability of the East Asian winter Monsoon in CMIP5 models. J. Clim. 2014, 27, 1659–1678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, W.; Gong, H.; Huang, P.; Wang, L.; Huang, G.; Hu, L. Biases and improvements of the ENSO-East Asian winter monsoon teleconnection in CMIP5 and CMIP6 models. Clim. Dyn. 2022, 59, 2467–2480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, W.; Hao, X.; Zhou, B.; Li, J.; Han, T. Understanding the ENSO–East Asian winter monsoon relationship in CMIP6 models: Performance evaluation and influencing factors. Clim. Dyn. 2024, 62, 7519–7534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hersbach, H.; Bell, B.; Berrisford, P.; Hirahara, S.; Horányi, A.; Sabater, J.M.; Nicolas, J.P.; Peubey, C.; Radu, R.; Schepers, D.; et al. The ERA5 global reanalysis. Quart. J. Roy. Meteor. Soc. 2020, 146, 1999–2049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rayner, N.; Parker, D.; Horton, E.; Folland, C.; Alexander, L.; Rowell, D.; Kent, E.; Kaplan, A. Global analyses of sea surface temperature, sea ice, and night marine air temperature since the late nineteenth century. J. Geophys. Res. 2003, 108, 4407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, P.W. First-and second-order conservative remapping schemes for grids in spherical coordinates. Mon. Weather Rev. 1999, 127, 2204–2210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Lau, K.M.; Kim, K.M. Variations of the East Asian jet stream and Asian-Pacific-American winter climate anomalies. J. Clim. 2002, 15, 306–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Chen, W. How well do existing indices measure the strength of the East Asian winter monsoon? Adv. Atmos. Sci. 2010, 27, 855–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duchon, C. Lanczos filtering in one and two dimensions. J. Appl. Meteorol. 1979, 18, 1016–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bretherton, C.S.; Widmann, M.; Dymnikov, V.P.; Wallace, J.M.; Bladé, I. The Effective Number of Spatial Degrees of Freedom of a Time-Varying Field. J. Clim. 1999, 12, 1990–2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; He, S. Weakening relationship between East Asian winter monsoon and ENSO after mid-1970s. Chin. Sci. Bull. 2012, 57, 3535–3540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Wu, S.; Ao, J. Role of the North Pacific Sea surface temperature in the East Asian winter monsoon decadal variability. Clim. Dyn. 2016, 46, 3793–3805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, T.; Chen, W. Climate variability of the East Asian winter monsoon and associated extratropical–tropical interaction: A review. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2021, 1504, 44–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, T.; Chen, W. Recent progress in understanding the interaction between ENSO and the East Asian winter monsoon: A review. Front. Earth Sci. 2023, 11, 1098517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Sumi, A.; Kimoto, M. Impact of El Niño on the East asian monsoon: A diagnostic study of the ’86/87 and ’91/92 events. J. Meteorol. Soc. Jpn. 1996, 74, 49–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W. Impacts of El Niño and La Niña on the cycle of the East asian winter and summer monsoon. Chin. J. Atmos. Sci. 2002, 26, 595–610. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, R.; Zhang, R.; Wen, M.; Li, T. Interdecadal changes in the asymmetric impacts of ENSO on wintertime rainfall over China and atmospheric circulations over Western North Pacific. Clim. Dyn. 2019, 52, 7525–7536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Wu, R.; Fu, X. Pacific-East Asian teleconnection: How does ENSO affect East Asian climate? J. Clim. 2000, 13, 1517–1536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, R.; Wang, B. Interannual variability of summer monsoon onset over the Western North Pacific and the underlying processes. J. Clim. 2000, 13, 2483–2501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, Y.O.; Alexander, M.A.; Bond, N.A.; Frankignoul, C.; Nakamura, H.; Qiu, B.; Thompson, L.A. Role of the Gulf Stream and Kuroshio–Oyashio systems in large-scale atmosphere–ocean interaction: A review. J. Clim. 2010, 23, 3249–3281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).