Abstract

Utah typically experiences 18 days with high fine particulate matter (PM2.5) levels exceeding the National Ambient Air Quality Standards per year. In August of 2022, Salt Lake City Mayor Erin Mendenhall convened an Indoor Air Quality Summit, during which experts in healthcare, industrial hygiene, and atmospheric science, among others, expressed the need to prioritize indoor air quality interventions more within the state. We conducted a furnace filter exchange pilot project that involved 11 families in Salt Lake City’s Westside. These families completed a survey regarding air quality-related concerns while researchers took air quality measurements—both inside and outside the residence. The goals of this pilot study were to gather data about the participants’ indoor and outdoor air quality perceptions, how frequently they changed their home air filters, and any barriers they experienced. In addition, this study developed a proof of concept demonstrating collecting preliminary indoor and outdoor air quality data and furnace filter deposition information alongside the survey. The survey results were limited by a small sample size (11 participants); however, among those sampled we found that residents are acutely concerned about outdoor air quality but are less worried about indoor air quality. We measured substantially lower indoor PM2.5 levels compared to ambient air and found a wide range of filter replacement times from those less than a month to over two years. Our research team learned not only about indoor air quality conditions and resident perceptions, but also about the needs of community members including access to filters, health education, and the need to allow more time to build trust between researchers and residents.

1. Introduction

The urbanized Wasatch Front in northern Utah typically experiences several weeks per year with poor air quality levels exceeding the National Ambient Air Quality Standards for either fine particulate matter or ozone pollution [1,2]. Wintertime atmospheric inversions in Utah [3] are linked to increased asthma emergency department visits [4], lower respiratory tract infections [5], higher rates of pneumonia [6], acute coronary events [7], increased absenteeism by schoolchildren [8,9], and lower standardized test scores [10]. Wildfire smoke and airborne dust present additional air pollution health hazards within the state [11,12,13]. While staying indoors provides some protection from air pollution, indoor air quality is not decoupled from outdoor air quality [14,15]. Numerous studies have shown that outdoor air pollutants penetrate buildings and impact the indoor environment, with many factors impacting the pollution transmission between outdoor and indoor environments (e.g., mechanical and natural ventilation, wind patterns, thermal plumes, solar radiation) [16]. Old construction homes and buildings generally have more outdoor pollutants transmitted indoors than more sealed homes. Case studies of high outdoor pollution being transmitted indoors include wildfires [17], urban pollutants [18], dust [19], and fireworks [20]. A study in Salt Lake County comparing indoor and outdoor air quality in an office building for one year over the course of different pollution events found that during inversion events, indoor pollutant concentration estimates were roughly 33% as high as outdoor pollution, and during wildfire events, indoor pollutant concentration estimates were approximately 77% as high as outdoor pollution [21]. Under both pollution events, there was a risk of indoor air pollution reaching or exceeding AQI levels classified as “unhealthy to sensitive groups”. Recent global research has also shown that indoor air pollution “disproportionally affects underprivileged communities” [22]. In Salt Lake City, Utah, “schools with higher proportions of racial/ethnic minority students observed higher pollution exposure” [23].

Filters in Heating, Ventilation, and Cooling (HVAC) systems are the most widely used methods to remove particulate pollution in indoor settings, although filter performance for wildfire smoke commonly observed in the western US is not well known [24]. A recent indoor air quality study conducted in daycare centers found that high-performance filters (with a Minimum Efficiency Reporting Value (MERV) of 13 or higher) resulted in 50% decreases in indoor PM2.5 concentrations [25]. Combining HVAC filters with portable air cleaners (PACs) is also a commonly employed method to reduce indoor air pollution. A recent study in California that utilized both HVAC and PAC systems found a 14–56% decrease in indoor PM2.5 concentrations compared to outdoor levels [26].

Indoor air quality has become a growing concern within Salt Lake County and across the state of Utah. In August of 2022, Salt Lake City Mayor Erin Mendenhall convened an Indoor Air Quality Summit. During the Summit, experts in multiple fields, including healthcare, industrial hygiene, and atmospheric sciences, expressed the need to prioritize indoor air quality interventions within the state [27]. The advent of the COVID-19 pandemic raised awareness about the need to upgrade indoor air filtration in public spaces to reduce the spread of infectious diseases. For example, researchers identified that HVAC system design plays an important role in achieving optimum air quality and optimum comfort [28]. At the same time, “air conditioning systems include important components that may help transmit viruses and need to be revised, such as air handling units, filters, transmission channels, and fans” [28]. This emphasis on upgrading air filtration as a potential intervention for the spread of COVID-19 helped prompt the upgrade of air filters in school districts across Utah. The cities of Park City, Alpine, and Salt Lake City School Districts, for example, upgraded to MERV 13 air filters in portions or all of their buildings [29].

A wide range of approaches have been used in urban areas to engage communities in addressing air quality problems [30,31]. Most citizen science public engagement initiatives have focused on community air monitoring of outdoor air pollution at neighborhood scales [30]. There have been some community efforts to promote indoor air filters and cleaners in neighborhoods. For example, do-it-yourself (DIY) portable air cleaners (PACs) served as exposure mitigation interventions in Denver, Colorado, in 2022 and 2023 [32]. As discussed by Fogg-Rogers et al. [33], “co-engagement activities that are attractive to diverse citizens” are needed to improve public participation in air pollution policymaking and emissions reduction programs. A study in Salt Lake City provided low-cost indoor and outdoor air quality sensors to 26 families with asthmatic children in a participatory air quality sensing project to better understand pollution source identification and behavioral responses. Engaging the public’s perceptions on indoor air pollution is also an area of active study. For example, misconceptions can occur among the public, such as the belief that burning scented candles or incense improve indoor air quality [34].

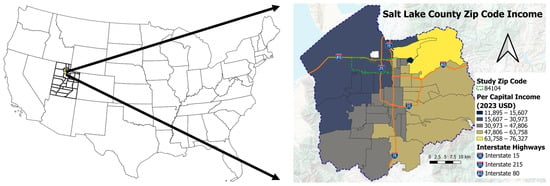

While measures have been made to upgrade filtration in public spaces, the impact of air filters on indoor air quality in private residences in Utah has not been previously investigated to our knowledge. In this study, we focused on two neighborhoods on the west side of Salt Lake City that face some of the greatest sociodemographic disparities as well as pollution exposure (Figure 1) [35]. Recognizing that MERV 11 air filters capture 85% of particles that are 3.0–10.0 microns in size [36], our research expanded upon prior work by piloting a study of participants’ indoor and outdoor air quality perceptions and of barriers in access and installation of home air filters in Salt Lake County through a survey, and demonstrating a proof of concept for identifying the potential effectiveness of upgrading filters to improve indoor air quality at these residences by measuring indoor and outdoor particulate pollution before and after the filter installation, and by also analyzing the composition of sediment deposits on furnace filters. The goals of this pilot study were to gather data about the participants’ indoor and outdoor air quality perceptions, how frequently they changed their home air filters, and any barriers they experienced as well as obtaining preliminary indoor and outdoor air quality data and furnace filter deposition information.

Figure 1.

Site location within Utah, USA. The study zip code within Salt Lake County is marked by the dashed green line. Interstate highways are shown as orange lines and the airport is the white area in the northwest part of the county. Per capita income is listed by zip code showing the study area to be in the lowest range for Salt Lake County.

2. Materials and Methods

In keeping with best practices developed in partnership with residents and researchers, this community-based research project was implemented with ongoing input from non-profit and governmental organizations in the participating neighborhoods as well as residents [37]. Details on the recruitment strategy and community partners are provided in Appendix A and Appendix B.

Participant inclusion criteria were based on home ownership in the 84104 or 84116 zip codes. These zip codes encompass the six neighborhoods on the west side of Salt Lake: Poplar Grove, Jordan Meadows, Glendale, Rose Park, Fair Park, and Westpointe. These criteria ensured that we targeted regions with the greatest air quality disparities [23] and that the participants had the right to change their air filters. It is worth noting that 49% of residents in the 84104 zip-code and 44% of residents of the 84116 zip-code are renters, and were thus excluded from participation [38]. Of the eleven participants in our study, four were recruited from the Poplar Grove Community Council meeting and seven were referrals from the Glendale Middle School teacher. Two families were recruited from the Northwest Middle School Community Council meeting, but they unfortunately were renters who lived outside of our study area boundary and thus could not be included in our study. Six study participants resided in Glendale and five resided in Poplar Grove—both neighborhoods belong to the 84104 zip code.

2.1. Site Visit Scheduling

We scheduled five installation sessions for our air filter exchange program. Each installation session lasted two hours in total, during which we visited up to four houses in thirty-minute blocks. We reached out to our participants 1–2 weeks before our installation period to schedule our site visits. When we contacted participants, we briefed them on what we would be doing in their homes during our site visit and guided them through a series of questions via a Qualtrics survey form. We recorded their names, phone numbers, addresses, availability for visits, home ownership statuses, filter access, and filter dimensions. All data was transferred from our Qualtrics survey form into a spreadsheet. We bulk ordered fifteen of each of the four most common filter dimensions through a donation by Hollingsworth & Vose, a company which works in air filtration. When residents required filters that we did not have in stock, we ordered their custom filters prior to our site visits. We contracted a certified HVAC technician to attend our installation sessions to ensure that the filters were changed correctly.

2.2. Site Visit PM2.5 Measurements

PM2.5 was measured using a MetOne Instruments ES-642 Remote Dust Monitor (Grants Pass, OR, USA) with a tolerance of 1 µg m−3 [39]. The ES-642 instruments utilize a nephelometer with high accuracy and are well-established research-grade instruments (Accuracy: ±5% with 0.6 µm polystyrene latex (PSL) spheres) [39]. The MetOne units are factory-calibrated when new and this study took place before the 2-year recommended calibration window. MetOne ES-642 performs humidity correction through an active, controlled inlet heater that regulates humidity at the sensor’s inlet to reduce measurement errors. This system is an integral part of the instrument and helps ensure accurate particulate matter concentration readings in both dry and high-humidity conditions [39]. While the range of the measurement is 0 to 100,000 µg/m3, we cannot distinguish between 0 and 1 µg/m3 measurements given the instrument sensitivity of ±1 µg m−3.

Upon arriving at participating homes, we started the indoor and outdoor air quality PM2.5 measurements by setting up the two ES-642 Remote Dust Monitors. The sensors were configured to output PM2.5 measurements at 5 s intervals and data was collected for approximately 30 min both indoors and outdoors during the site visit. Summary statistics including minimum, maximum, mean, and standard deviation were calculated for each site. It is important to note that this collection was carried out as a demonstration or proof of concept only, and more lengthy measurements would be needed to make statistically robust conclusions about the impacts of filters and indoor versus outdoor air pollution.

2.3. Site Visit Protocol

On the day of our site visits, we sent confirmation texts and calls to all participants. We shared the addresses of all participants with our HVAC technician and met at their homes. Upon arriving at participating homes, we started the indoor and outdoor air quality measurements with the MetOne Instruments ES-642 Remote Dust Monitor as outlined in Section 2.2. The homeowner turned on the furnace in the home to allow for air circulation inside the house and through the filter. The furnace was turned off to allow the HVAC technician to change the filter, with the participant available to watch the process. The HVAC technician wore gloves to eliminate contamination of the used air filter. The used filter was folded into a Zip-Loc bag and labeled for sediment analysis. Once the filter was changed, the furnace was turned on again to recirculate the air through the new filter and gather air quality data with the new filter. Throughout this process, we conducted our qualitative survey with our participants (Appendix B). At the conclusion of our visit, we provided participants with an instructional pamphlet, which included instructions on how to change their air filter, information on how to improve indoor air quality, and a QR code which directed to an air filter instructional video. We also left participants with a second air filter for their next filter change.

2.4. Elemental Analyses of Residence Air Filters

The filters from each residence were cut into approximately 2 cm × 2 cm squares ensuring no deposit loss. The loaded filters were cold leached at 22 °C for 24 h in 0.8 M HNO3 to extract the 42 study metals. Geochemical analysis for elemental concentrations was performed in the ICP-MS Metals and Strontium Isotope Facility of the Geology and Geophysics Department at the University of Utah by quadrupole Inductively Coupled Mass Spectrometry (ICP-MS) [40] using an external calibration method with internal standard.

3. Results

3.1. Survey Findings

We learned that participants were consistently more concerned about outdoor air pollution than indoor air pollution, as seen in Table 1.

Table 1.

Participant level of concern about outdoor and indoor air quality.

The most frequently listed outdoor air quality concerns were as follows: (1). dust from the drying Great Salt Lake, (2) the wintertime inversion effect, (3). pollution and contamination from nearby industrial activity, (4). transportation emissions, and (5). the impact of poor air quality on children and those with asthma. The most frequently listed indoor air quality concerns were how the age of the home impacted air quality, pollution from cooking, and pollutants such as radon, carbon monoxide, and mold. Interestingly, two participants expressed concern about how opening their windows would allow polluted air into their homes, reinforcing the finding that there was a greater level of concern about outdoor air pollution than indoor air pollution. As shown in Table 2, there was high variability in how recently participants had changed their filters, ranging from three weeks to two years prior to our visit. Four participants expressed no difficulty with changing their filters and three noted that the location of their filter was difficult to access, such as in a basement crawl space or on their roof. One mentioned the prohibitive cost of relocating the system for better access. Others shared that they were too busy, had trouble remembering, or struggled to find the right dimensions to change their filter.

Table 2.

Distribution of air filter replacement frequency.

3.2. PM2.5 Measurements

The results of the demonstration indoor versus outdoor observations for PM2.5 are shown in Table 3. In all cases, the indoor readings were much smaller than the outdoor readings, showing that homes are protective against outdoor PM2.5, although more lengthy measurements would be needed to quantitatively support this finding. The substantial differences in outdoor concentrations are primarily due to the proximity of homes to larger roads, such as Interstate 15, Interstate 80, and Interstate 215. The indoor readings were very similar, with all homes showing mean concentrations lower than 0.5 µg m−3, and we did not find marked differences after the air filters were replaced.

Table 3.

Outdoor and indoor PM2.5 measurements.

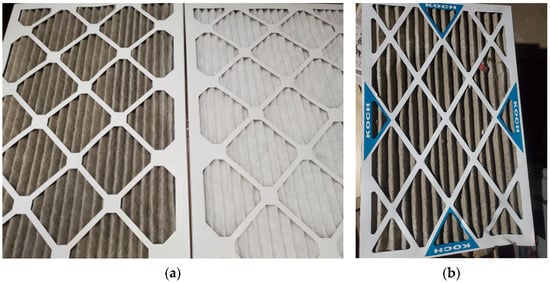

3.3. Furnace Filter Observations

An example of furnace filters from this study is shown in Figure 2. Figure 2a compares a used filter with a clean filter while Figure 2b shows a used filter with large debris (~1 cm) embedded in the filter itself. These filters were both used for much longer than the recommended 1-month period and it is likely that they were not only ineffective but also caused substantial stress on the furnace equipment as they appeared to be largely clogged with impurities. Of the 11 participants in this study, only 4 had replaced the filters within the recommended 1-month period of use (Table 2). Several furnace filters were found to be completely clogged with large debris, including pet hair, which raised concerns about the home vents. A visual inspection of intake vents showed that they were often obstructed, either by objects placed in front of them, or had unclean vent slats potentially lowering the flow rate.

Figure 2.

Filter exchange program filter. (a) A comparison between a used furnace filter from a residence and a new replacement filter and (b) a used filter with large (~1 cm) debris.

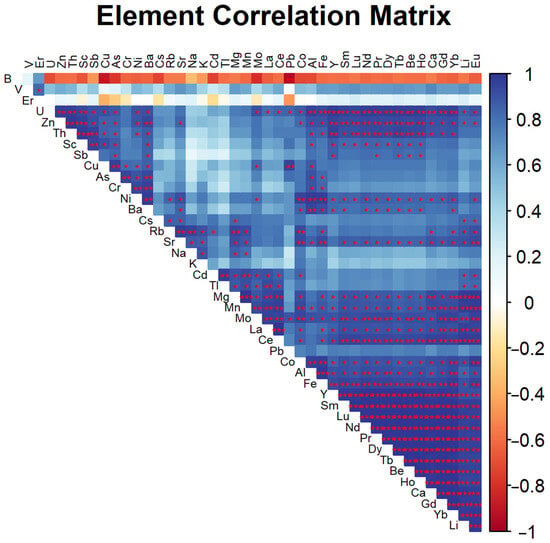

3.4. Furnace Filter Deposition

The furnace filter deposition analysis results are shown in Table 4, and the correlation matrix is shown in Figure 3. Elevated magnesium levels are likely to be associated with emissions from the large U.S. Magnesium plant located approximately 60 miles northwest of the homes [41]. During northwest flow, air masses from the magnesium plant vicinity pass over the Salt Lake Valley. This manufacturing facility has been found to be a substantial contributor to air pollution in the Salt Lake Valley [41]. Aluminum, iron, and zinc are associated with brake wear as they are all elements found on rotors, either as structural components or protective coating. Arsenic and lead are metals associated with substantial health concerns and have been found to be present and available in dust from the drying Great Salt Lake (GSL). Metal shredding facilities are also located on the Westside—these types of facilities have been known to emit hazardous air pollutants, including lead and zinc, through their processes [42]. Uranium is found naturally at high concentrations in many parts of the American West and is also found on the dust from the GSL.

Table 4.

Furnace filter deposition analysis results listing minimum, maximum, mean, median, interquartile range, standard deviation, and relative standard deviation for study elements. All units are (mg/kg) except for RSD.

Figure 3.

Furnace filter element correlation matrix. For statistically significant results, *, **, and *** represent p < 0.05, p < 0.01, and p < 0.001, respectively.

The results from Table 4 show relatively consistent relative standard deviations, mostly ranging from 60–90%. The most variable element, based on RSD, is boron, which exhibits largely negative correlations with the presence of other elements (Figure 3). With few exceptions, the presence of erbium is not correlated to other elements. Nearly half of the elements sampled are statistically significantly associated, at various levels, with other elements (Figure 3). The variability in correlations between elements shows that the study area, despite its relatively small spatial extent, has some metal composition differences. As this is a pilot study with limited participants, Figure 3 and the results from Table 4 are intended for illustrative purposes to demonstrate the elemental analysis techniques. The elemental analysis of furnace filters as demonstrated here cannot be directly associated with air quality without the addition of air pollution measurements to link to the filter deposition results.

4. Discussion

4.1. Community Engagement

In addition to the data collected, we learned some key process elements which may be incorporated into a larger future study. First and foremost, this pilot study demonstrated the importance of allowing time for relationship and trust building. Limitations on the availability of the filters that were donated to our program necessitated an expedited timeline. While we successfully recruited eleven participants for a larger-scale study, allowing more time for establishing relationships will increase the likelihood of higher participation rates. As discussed by Green et al. [43], “participatory research projects usually require complex and time-consuming processes of building relationships, trust, and divisions of responsibilities among partners.” We learned that it is crucial that someone with credibility in the community make the first introduction about our program to potential participants and sustain efforts in building trust and seeking requests from community participants are needed. In our study, a teacher at a local school introduced us to interested families, and a Poplar Grove Community Councilmember discussed the merits of our program to elicit interest at a community council meeting. When we attempted to advertise our program without being vouched for by a trusted source, our recruitment was unsuccessful. It is also critical to make registration for the program as seamless as possible for participants. For example, it was more fruitful to fill out the registration form with interested participants over the phone rather than ask them to fill out the form on their own. Lastly, we learned that the research team needs someone fluent in Spanish for all recruitment events and site visits. The Westside has a significant Spanish-speaking population, and while we provided flyers in Spanish at recruitment events, without speaking with families in Spanish, we were unable to build trust and interest in the program. We had a bilingual researcher at each of our site visits, which allowed for more in-depth communication and trust with Spanish-speaking families. Our study builds on other studies that have shown that “inclusive, community-led approaches that foster trust, build cultural competence” and overcome language barriers are needed for best practice engagement in minority communities [44].

4.2. Community Health

One of the most significant findings of our pilot study was the need to ensure that we have connections to home-improvement resources for low-income families if we find significant structural problems during our site visits. At one home, our HVAC technician identified a broken furnace pipe which had the potential to emit pollutants into the home when the heating was turned on. The impacted family was introduced to community resources and grants to assist them and will continue to communicate with them to ensure they get the support they need before they need to heat their home again. If we identify potentially lethal circumstances in a home without providing families with the correct resources, we would be doing great disservice to study participants.

Through our pilot research we noted that participants were more concerned about outdoor air quality than indoor air quality. While outdoor air is a critical issue in Salt Lake County, indoor air quality has health ramifications [45,46]. Additionally, indoor particulate matter sources are a substantial source of health concerns [47,48]. Because people spend approximately one third of their life sleeping, often breathing through their mouths while asleep, residential air quality is an important consideration [49]. As discussed by Nassikas et al. [50], “there is no regulatory framework similar to the Clean Air Act for the indoor environment, where people spend the majority of their time and are exposed to air pollutants, both similar to and unique from outdoor air.” Even less attention is given to unique urban environments where elevated episodic pollutants from outside can penetrate inside, such as what occurs in northern Utah during wildfires, dust storms, and wintertime inversions.

Nearly half of the families we visited did not have a problem changing indoor air filters. As such, future projects might focus on researching what types of air filters are needed and providing them at no cost. Given that filters should be changed monthly, this initiative could serve as educational outreach and a reminder of the importance of changing filters while also increasing access and building trust within the community.

4.3. Pollutant Collection Proof of Concept

The range of furnace filter age self-reported by the families (Table 2) and the lower concern for indoor air quality (Table 1) showed that there is a substantial need for education on air quality, particularly indoors. While Utah’s outdoor air quality concerns are well-documented [51] and monitored [52], indoor air pollution, particularly in homes, is less well-studied. The irregularly changed filters found in this study (Figure 2) provide evidence that families are either financially, or otherwise, unable to change filters to maintain healthy indoor quality levels, or that awareness about the detrimental effects of poor indoor air quality is lacking. It is also important to educate community members about the importance of regularly changing their furnace filters for best efficiency and to preserve the longevity of their HVAC unit. A filter that has been in use for longer than the recommended 1-month period is likely to become clogged and produce more resistance. This can strain the HVAC fan and cause premature wear and tear, resulting in an increased economic cost of maintenance and repair.

The furnace filter deposition analysis results in this study are among the first studies investigating heavy metals and other pollutant deposition in the Salt Lake Valley. It is important to note that the filter deposition results represent integrated particulate accumulation, not direct air concentrations. As described in Table 2, some furnace filters had been changed as recently as half a month before our visit while some were nearly two years old which made the integration time irregular across participants. Another important aspect of the elemental analysis to note is that gaseous pollutants such as ozone, volatile organic compounds, nitrous oxides, or non-metal elements common in organic compounds, such as carbon (C), sulfur (S), or oxygen (O), are not represented in the filter deposition results. A number of studies have analyzed metal deposition in the lakebed of the Great Salt Lake [53,54,55], but less work has been done on the transport of these pollutants into the surrounding communities. Putman et al. [56] recently studied the transport of metals and contaminates in dust from the Great Salt Lake into a number of shoreline locations. Lee et al. [57] found that elevated asthma rates in regions with higher metal concentrations. We identify the potential presence of pollutants impacting residences in the Salt Lake Valley. Variations in the observed pollutants could result from many factors, including proximity to dust plumes from the Great Salt Lake (e.g., arsenic and lead), being downwind from the U.S. Magnesium plant (magnesium), and proximity to on-road vehicle emissions or commercial air traffic. For example, in the atmosphere, calcium is observed to be strongly correlated with other elements typically found in soil dust and sea spray such as aluminum, iron and potassium, and this is confirmed in the element correlation matrix (Figure 3).

The outdoor PM2.5 readings showed the large variability within a neighborhood scale. During the same day, some homes reported outdoor readings that were noticeably higher than other homes and these were ascribed to neighbors grilling food nearby, based on our observations. The indoor PM2.5 values showed little variability with all homes reading below 1 µg m−3. This is largely explained by the outdoor air quality since April and May are historically the least polluted months of the year due to frequent precipitation and low incidence of seasonal pollutants or episodic events.

4.4. Study Limitations

The small sample size (11 participants) limited the conclusiveness of our findings. However, this pilot project successfully established community relationships and provided our research team with critical insights on air pollution awareness and measurements for follow up work. One limitation of the study was that the observed outdoor pollutant concentrations were relatively low during the study period. A longer study period with higher observed outdoor particulate pollutants from episodic dust, smoke and wintertime inversion events would be ideal, to be able to determine in any differences in the before and after filters were replaced situations. Additionally, determining at what point the filters become clogged and ineffective at air purification for a range of outdoor conditions would be highly valuable in the episodic type of outdoor pollution events observed in Salt Lake City. We did not measure the transmission of the metals found deposited on the filters to the air in the room, so a future study that measured these in the indoor air could also provide insight into the impacts of dirty filters on the indoor air quality. A larger sample size of participants would further strengthen the study findings and broaden and deepen understanding of indoor and outdoor air quality perceptions and filter replacement effectiveness on improving indoor air quality in the Salt Lake Valley. Given additional time for relationship building, we likely would have been able to cultivate more partners to help build on and reinforce what we learned here. Spatial analysis of the furnace filter deposition analysis results taken over a longer period would provide new insight into additional pollution concerns.

4.5. Future Work

Future work could incorporate an educational component aimed at increasing community awareness of the health risks associated with indoor air pollution. Although separate from research activities, such education could be supported through tools like personal exposure monitors, which have been effective in promoting public understanding of air quality and health outcomes [58]. From a research perspective, an important lesson from this study is the timing of recruitment. Initiating recruitment earlier in the year would allow for furnace filter exchanges during peak heating periods (January or February), thereby capturing more representative data. Further work will identify additional means to include a more representative population including non-native English speakers, renters, and traditionally underrepresented communities. This would involve working with community organizations and reaching out to cultural groups and other trusted sources. Finally, multiple families expressed interest in filters for air conditioning units, indicating a potential direction for future research. Lastly, research on the presence and quantity of heavy metals captured by filters and houses’ proximity to known air pollution sources, such as roadways, metal shredding facilities, and other emitters, could help inform evidence-based risk assessment and mitigation.

5. Conclusions

We conducted a furnace filter exchange pilot project that involved 11 families in Salt Lake City’s Westside which included a survey of air quality-related concerns, brief air quality measurements, and analysis of deposits on furnace filters. The survey results showed that residents are acutely concerned about outdoor air quality but less so for indoor air quality. We observed substantial variation in the time since participants last changed their filters, ranging from less than one month to over two years. Due to the relatively clean outdoor air during the study period, the indoor air was also found to be clean. Filter deposits provided preliminary information on air pollutant variability within a neighborhood. Future research may benefit from data collection from a large, cross-sectional pool of respondents. We recommend future studies provide filters for resident installation, include indoor air quality education, allow more time for trust building and education between study organizers and participants, and increase the temporal span of air quality measurements to capture a more thorough air exchange after the new filters are installed.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.L.M., L.P.C. and A.C.; methodology, D.L.M., L.P.C. and A.C.; software, D.L.M.; validation, D.L.M., E.T.C. and L.P.C.; formal analysis, D.L.M., E.T.C. and L.P.C.; investigation, D.L.M. and L.P.C.; resources, D.L.M. and A.C.; data curation, D.L.M., E.T.C. and L.P.C.; writing—original draft preparation, D.L.M., E.T.C., L.P.C. and A.C.; writing—review and editing, D.L.M., E.T.C., L.P.C. and A.C.; visualization, D.L.M. and E.T.C.; supervision, D.L.M., A.C.; project administration, D.L.M. and A.C.; funding acquisition, D.L.M. and A.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the SPARC Environmental Justice Lab at the University of Utah and Hollingsworth & Vose provided the furnace filters.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and declared exempt by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Utah (IRB_00163068, 24 April 2023).

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data available on request due to restrictions privacy.

Acknowledgments

Sarah Hoy, Julia Wales, and Jasmine Walton from NeighborWorks SLC provided initial feedback about filter exchange program, introduced our research team to members of the five Westside Community Councils as well as contacts at Northwest Middle School, provided suggestions and guidance on best practices in working with Westside residents, and assisted in participant recruitment by sharing the program flier on social media. NeighborWorks works in partnership with residents to build on strengths of neighborhoods and create opportunities. Angela Romero, Senior Community Programs Manager from Salt Lake City Corporation, introduced us to community leaders at Glendale Middle School for our study recruitment and provided input on which organizations to partner with in the area. Chelsie Acosta, a teacher at Glendale Middle School introduced us to several study participants. Rylie Rayner, Diana Gonzalez, and Ben Timm, student researchers from the Environmental Justice class at the University of Utah, ENVST 3365, assisted in the development of flyers, surveys, and sign-up forms in Spanish and English, and assisted during site visits. The 11 participants who shared their homes and their concerns about air quality. Diego P. Fernandez and his team performed the geochemical analysis for elemental concentrations. Peter Whelan processed the filter samples.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

NeighborWorks Salt Lake, a non-profit which aims to create “opportunities through housing, resident leadership, and youth and economic development” assisted us in designing our recruitment strategy and introduced us to additional community collaborators [59]. We created a partnership agreement to ensure that we were meeting community and researcher needs while providing a mechanism for ongoing communication and feedback. We contacted members of the Fairpark, Glendale, and Poplar Grove Community Councils, and presented at the Glendale and Poplar Grove Community Council meetings. We also attended a community council meeting at Northwest Middle School in the Westpointe Neighborhood, and a food distribution event at Rose Park Elementary School. We consulted a member of the Westside Coalition, a nonprofit organization which acts upon the interests of the six Westside communities, on the need and content of our survey questions. Our survey questions were reviewed by a member of the Westside Coalition to ensure that our data was useful to those working on Salt Lake City’s Westside. They were asked about their level of concern about indoor and outdoor air quality, using the following scale: Not Concerned, Moderately Concerned, and Very Concerned. We used a combination of in-person presentations, flyers, and referrals to recruit participants for our pilot study. During the in-person events, we gave a short presentation to community members about the project, gathered phone numbers of those who were interested, and distributed flyers which contained a QR code that linked to a Qualtrics sign-up form for our program. We also sent home flyers with the students at Rose Park Elementary School. Lastly, we utilized referrals from an educator at Glendale Middle School.

Appendix B

Air Filter Exchange Research Questions (English):

- Do you know when the last time your home air filter was changed?

- What barriers, if any, do you experience to changing your air filter or having your air filter changed?

- What concerns do you have, if any, about outdoor air quality?

- Please rate your level of concern about outdoor air quality:

- ○

- Very concerned

- ○

- Moderately concerned

- ○

- Not concerned

- What concerns do you have, if any, about indoor air quality?

- Please rate your level of concern about indoor air quality:

- ○

- Very concerned

- ○

- Moderately concerned

- ○

- Not concerned

Air Filter Exchange Research Questions (Spanish):

- Sabes cuando fue la última vez que cambio el filtro de aire de su casa?

- Qué barreras, si hay, experiencia para cambiar su filtro de aire or que le cambien su filtro?

- Qué preocupaciones tiene sobre la calidad del aire exterior?

- Por favor califique su nivel de preocupación de la calidad de aire exterior?

- ○

- Muy precupado(a)

- ○

- Moderadamente preocupado(a)

- ○

- No preocupado

- Que preocupaciones tiene, si las tiene, sobre la calidad del aire interior?

- Por favor califique su nivel de preocupación de la calidad de aire interior?

- ○

- Muy precupado(a)

- ○

- Moderadamente preocupado(a)

- ○

- No preocupado

References

- Utah Department of Environmental Quality. Inversions. Available online: https://deq.utah.gov/air-quality/inversions (accessed on 12 December 2023).

- Jaffe, D.A.; Ninneman, M.; Nguyen, L.; Lee, H.; Hu, L.; Ketcherside, D.; Jin, L.; Cope, E.; Lyman, S.; Jones, C. Key results from the salt lake regional smoke, ozone, and aerosol study (SAMOZA). J. Air Waste Manag. Assoc. 2024, 74, 163–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crosman, E.T.; Horel, J.D. Winter lake breezes near the Great Salt Lake. Bound.-Layer Meteorol. 2016, 159, 439–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beard, J.D.; Beck, C.; Graham, R.; Packham, S.C.; Traphagan, M.; Giles, R.T.; Morgan, J.G. Winter temperature inversions and emergency department visits for asthma in Salt Lake County, Utah, 2003–2008. Environ. Health Perspect. 2012, 120, 1385–1390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horne, B.D.; Joy, E.A.; Hofmann, M.G.; Gesteland, P.H.; Cannon, J.B.; Lefler, J.S.; Blagev, D.P.; Korgenski, E.K.; Torosyan, N.; Hansen, G.I. Short-term elevation of fine particulate matter air pollution and acute lower respiratory infection. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2018, 198, 759–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirozzi, C.S.; Jones, B.E.; VanDerslice, J.A.; Zhang, Y.; Paine, R., III; Dean, N.C. Short-Term Air Pollution and Incident Pneumonia. A Case–Crossover Study. Ann. Am. Thorac. Soc. 2018, 15, 449–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pope, C.A., III; Muhlestein, J.B.; Anderson, J.L.; Cannon, J.B.; Hales, N.M.; Meredith, K.G.; Le, V.; Horne, B.D. Short-term exposure to fine particulate matter air pollution is preferentially associated with the risk of ST-segment elevation acute coronary events. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2015, 4, e002506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mendoza, D.L.; Pirozzi, C.S.; Crosman, E.T.; Liou, T.G.; Zhang, Y.; Cleeves, J.J.; Bannister, S.C.; Anderegg, W.R.; Paine, R., III. Impact of low-level fine particulate matter and ozone exposure on absences in K-12 students and economic consequences. Environ. Res. Lett. 2020, 15, 114052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ransom, M.R.; Pope, C.A. Elementary school absences and PM10 pollution in Utah Valley. Environ. Res. 1992, 58, 204–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullen, C.; Grineski, S.E.; Collins, T.W.; Mendoza, D.L. Effects of PM2.5 on Third Grade Students’ Proficiency in Math and English Language Arts. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 6931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoennagel, T.; Balch, J.K.; Brenkert-Smith, H.; Dennison, P.E.; Harvey, B.J.; Krawchuk, M.A.; Mietkiewicz, N.; Morgan, P.; Moritz, M.A.; Rasker, R.; et al. Adapt to more wildfire in western North American forests as climate changes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, 4582–4590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flavelle, C. As the Great Salt Lake Dries up, Utah faces an “Environmental Nuclear Bomb”. The New York Times, 8 June 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Grineski, S.E.; Mallia, D.V.; Collins, T.W.; Araos, M.; Lin, J.C.; Anderegg, W.R.; Perry, K. Harmful dust from drying lakes: Preserving Great Salt Lake (USA) water levels decreases ambient dust and racial disparities in population exposure. One Earth 2024, 7, 1056–1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawat, N.; Kumar, P. Interventions for improving indoor and outdoor air quality in and around schools. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 858, 159813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, C.A.; Vicente, E.D.; Evtyugina, M.; Vicente, A.M.; Nunes, T.; Lucarelli, F.; Calzolai, G.; Nava, S.; Calvo, A.I.; del Blanco Alegre, C. Indoor and outdoor air quality: A university cafeteria as a case study. Atmos. Pollut. Res. 2020, 11, 531–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadi, M.; Calautit, J. Quantifying the transmission of outdoor pollutants into the indoor environment and vice versa—Review of influencing factors, methods, challenges and future direction. Sustainability 2022, 14, 10880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajagopalan, P.; Goodman, N. Improving the indoor air quality of residential buildings during bushfire smoke events. Climate 2021, 9, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Yuk, H.; Yun, B.Y.; Kim, Y.U.; Wi, S.; Kim, S. Passive PM2.5 control plan of educational buildings by using airtight improvement technologies in South Korea. J. Hazard. Mater. 2022, 423, 126990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, H.-W.; Shen, H.-Y. Indoor and outdoor PM2.5 and PM10 concentrations in the air during a dust storm. Build. Environ. 2010, 45, 610–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalinauskaitė, A.; Davulienė, L.; Pauraite, J.; Minderytė, A.; Byčenkienė, S. New Year Fireworks Influence on Air Quality in Case of Stagnant Foggy Conditions. Urban Sci. 2024, 8, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendoza, D.L.; Benney, T.M.; Boll, S. Long-term analysis of the relationships between indoor and outdoor fine particulate pollution: A case study using research grade sensors. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 776, 145778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albadrani, M. Socioeconomic disparities in mortality from indoor air pollution: A multi-country study. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0317581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullen, C.; Grineski, S.; Collins, T.; Xing, W.; Whitaker, R.; Sayahi, T.; Becnel, T.; Goffin, P.; Gaillardon, P.-E.; Meyer, M. Patterns of distributive environmental inequity under different PM2.5 air pollution scenarios for Salt Lake County public schools. Environ. Res. 2020, 186, 109543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirman, T.; Shirman, E.; Liu, S. Evaluation of filtration efficiency of various filter media in addressing wildfire smoke in indoor environments: Importance of particle size and composition. Atmosphere 2023, 14, 1729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.D.; Kang, K. Experimental Study of Energy Recovery Ventilator for Enhancing Indoor Air Quality in Daycare Centers: A Case Study in South Korea. Buildings 2025, 15, 566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, M.; Castorina, R.; Chen, W.; Moore, D.; Peerless, K.; Hurley, S. Effectiveness of Air Filtration in Reducing PM2.5 Exposures at a School in a Community Heavily Impacted by Air Pollution. Atmosphere 2024, 15, 901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boal, J. Researchers Say Air Pollution Is Getting Inside, Recommend MERV 13 Filter. KSLTV.com. 2022. Available online: https://ksltv.com/local-news/researchers-say-air-pollution-is-getting-inside-recommend-merv-13-filter/501403/ (accessed on 24 October 2024).

- Elsaid, A.M.; Ahmed, M.S. Indoor air quality strategies for air-conditioning and ventilation systems with the spread of the global coronavirus (COVID-19) epidemic: Improvements and recommendations. Environ. Res. 2021, 199, 111314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glas, B. KSL Investigates If Utah Schools Are Doing Enough to Vent the Virus. KSL.com. 2020. Available online: https://www.ksl.com/article/50007513/ksl-investigates-if-utah-schools-are-doing-enough-to-vent-the-virus (accessed on 20 January 2025).

- Commodore, A.; Wilson, S.; Muhammad, O.; Svendsen, E.; Pearce, J. Community-based participatory research for the study of air pollution: A review of motivations, approaches, and outcomes. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2017, 189, 378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ward, F.; Lowther-Payne, H.J.; Halliday, E.C.; Dooley, K.; Joseph, N.; Livesey, R.; Moran, P.; Kirby, S.; Cloke, J. Engaging communities in addressing air quality: A scoping review. Environ. Health 2022, 21, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sankhyan, S.; Clements, N.; Heckman, A.; Hollo, A.K.; Gonzalez-Beltran, D.; Aumann, J.; Morency, C.; Leiden, L.; Miller, S.L. Optimization of a do-it-yourself air cleaner design to reduce residential air pollution exposure for a community experiencing environmental injustices. Atmosphere 2023, 14, 1734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fogg-Rogers, L.; Sardo, A.M.; Csobod, E.; Boushel, C.; Laggan, S.; Hayes, E. Citizen-led emissions reduction: Enhancing enjoyment and understanding for diverse citizen engagement with air pollution and climate change decision making. Environ. Sci. Policy 2024, 154, 103692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, A.; Schulte, K.; Varaden, D. ‘Incense is the one that keeps the air fresh’: Indoor air quality perceptions and attitudes towards health risk. BMC Public Health 2024, 24, 3178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendoza, D.L.; Benney, T.M.; Ganguli, R.; Pothina, R.; Pirozzi, C.S.; Quackenbush, C.; Baty, S.R.; Crosman, E.T.; Zhang, Y. The Role of Structural Inequality on COVID-19 Incidence Rates at the Neighborhood Scale in Urban Areas. COVID 2021, 1, 186–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United States Environmental Protection Agency. What Is a MERV Rating? Available online: https://www.epa.gov/indoor-air-quality-iaq/what-merv-rating (accessed on 12 December 2023).

- The Community Research Collaborative. In It Together: Community-Based Research Guidelines for Communities and Higher Education; University of Utah: Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- UnitedStatesZipCodes.org. Stats and Demographics for the 84104 ZIP Code. Available online: https://www.unitedstateszipcodes.org/84104/ (accessed on 12 December 2023).

- Met One Instruments Inc. ES-642 Dust Monitor Operation Manual; Met One Instruments Inc.: Grants Pass, OR, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Agilent. Agilent 8900 Triple Quadrupole ICP-MS. Available online: https://www.agilent.com/cs/library/technicaloverviews/public/5991-6942EN.pdf (accessed on 18 October 2025).

- Womack, C.C.; Chace, W.S.; Wang, S.; Baasandorj, M.; Fibiger, D.L.; Franchin, A.; Goldberger, L.; Harkins, C.; Jo, D.S.; Lee, B.H. Midlatitude ozone depletion and air quality impacts from industrial halogen emissions in the Great Salt Lake Basin. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2023, 57, 1870–1881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- United States Environmental Protection Agency. Violations at Metal Recycling Facilities Cause Excess Emissions in Nearby Communities. Available online: https://www.epa.gov/system/files/documents/2021-07/metalshredder-enfalert.pdf (accessed on 15 August 2025).

- Green, L.; Daniel, M.; Novick, L. Partnerships and coalitions for community-based research. Public Health Rep. 2001, 116, 20–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakhan, C. Best Practices in Sustainable Communication for Minority Communities. SSRN 4946143. 2024. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=4946143 (accessed on 6 June 2025).

- Tran, V.V.; Park, D.; Lee, Y.-C. Indoor Air Pollution, Related Human Diseases, and Recent Trends in the Control and Improvement of Indoor Air Quality. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 2927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendoza, D.L.; Benney, T.M.; Bares, R.; Fasoli, B.; Anderson, C.; Gonzales, S.A.; Crosman, E.T.; Hoch, S. Investigation of Indoor and Outdoor Fine Particulate Matter Concentrations in Schools in Salt Lake City, Utah. Pollutants 2022, 2, 82–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tofful, L.; Canepari, S.; Sargolini, T.; Perrino, C. Indoor air quality in a domestic environment: Combined contribution of indoor and outdoor PM sources. Build. Environ. 2021, 202, 108050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishihama, Y.; Jung, C.-R.; Nakayama, S.F.; Tamura, K.; Isobe, T.; Michikawa, T.; Iwai-Shimada, M.; Kobayashi, Y.; Sekiyama, M.; Taniguchi, Y. Indoor air quality of 5,000 households and its determinants. Part A: Particulate matter (PM2. 5 and PM10–2.5) concentrations in the Japan Environment and Children’s Study. Environ. Res. 2021, 198, 111196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canha, N.; Teixeira, C.; Figueira, M.; Correia, C. How is indoor air quality during sleep? A review of field studies. Atmosphere 2021, 12, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nassikas, N.J.; Horner, E.; Rice, M.B. Indoor air: Guidelines, policies, and regulation. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2024, 154, 911–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeMarco, A.L.; Hardenbrook, R.; Rose, J.; Mendoza, D.L. Air pollution-related health impacts on individuals experiencing homelessness: Environmental justice and health vulnerability in Salt Lake County, Utah. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 8413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mendoza, D.L.; Crosman, E.T.; Mitchell, L.E.; Jacques, A.; Fasoli, B.; Park, A.M.; Lin, J.C.; Horel, J. The TRAX Light-Rail Train Air Quality Observation Project. Urban Sci. 2019, 3, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorsen, M.L.; Handy, R.G.; Sleeth, D.K.; Thiese, M.S.; Riches, N.O. A comparison study between previous and current shoreline concentrations of heavy metals at the Great Salt Lake using portable X-ray fluorescence analysis. Hum. Ecol. Risk Assess. Int. J. 2017, 23, 1941–1954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wurtsbaugh, W.A.; Leavitt, P.R.; Moser, K.A. Effects of a century of mining and industrial production on metal contamination of a model saline ecosystem, Great Salt Lake, Utah. Environ. Pollut. 2020, 266, 115072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jung, J.; Frantz, C.M.; Fernandez, D.P.; Werner, M.S. Toxic elements in benthic lacustrine sediments of Utah’s Great Salt Lake following a historic low in elevation. Front. Soil Sci. 2024, 4, 1445792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putman, A.L.; Blakowski, M.; DiViesti, D.; Fernandez, D.; McDonnell, M.; Longley, P.; Jones, D.K. Contributions of Great Salt Lake playa-and industrially sourced priority pollutant metals in dust contribute to possible health hazards in the communities of northern Utah. GeoHealth 2025, 9, e2025GH001462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, L.Y.; Kerry, R.; Ingram, B.; Golden, C.S.; LeMonte, J.J. Investigating the Spatial Patterns of Heavy Metals in Topsoil and Asthma in the Western Salt Lake Valley, Utah. Environments 2024, 11, 223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, Y.M.; Chavez, D.; Sousan, S.; Figueroa-Bernal, N.; Alvarez, J.R.; Rocha-Peralta, J. Personal exposure monitoring using GPS-enabled portable air pollution sensors: A strategy to promote citizen awareness and behavioral changes regarding indoor and outdoor air pollution. J. Expo. Sci. Environ. Epidemiol. 2023, 33, 347–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NeighborWorks Salt Lake. Available online: https://www.nwsaltlake.org/ (accessed on 12 December 2023).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).