1. Introduction

Mine dust not only poses a serious occupational risk of pneumoconiosis but also presents a significant explosion hazard [

1,

2]. Once pneumoconiosis develops, lung lesions continue to progress, ultimately leading to impaired pulmonary function and even respiratory failure [

3,

4,

5], with a reported mortality rate of up to 22.04% [

6,

7]. Coal workers’ pneumoconiosis alone accounts for more than 50% of all reported cases. In China, 14 of the 24 major coal mine accidents—each causing more than 100 fatalities—were attributed to dust explosions [

8,

9]. In addition, high dust concentrations in underground coal mines reduce visibility, increasing the likelihood of accidents caused by human operational errors and severely limiting the perception accuracy of unmanned intelligent equipment. Therefore, effective prevention and control of mine dust are essential for ensuring production safety and protecting miners’ health.

The heading face in underground coal mines is among the zones most severely affected by dust pollution. Cutting operations performed by roadheaders on coal and rock generate substantial quantities of dust, with instantaneous concentrations frequently exceeding 1000 mg/m

3 [

10]. With the rapid development of tunneling machinery and increasing demands for higher advance rates, the use of continuous miners equipped with transverse cutting heads has increased. Compared with axial roadheaders, continuous miners have significantly larger cutting heads, which enlarge the cutting zone and intensify cutting activity, thereby further aggravating the difficulty of dust control.

To address dust control at the heading face, several technologies have been developed, including water mist dust suppression, foam dust suppression, dust extraction using a dust extraction fan, and ventilation-based control. Water mist dust suppression primarily relies on two mechanisms: pre-wetting of the cutting zone and capture of suspended dust particles. However, because both water mist and dust exist as dispersed phases, the collision probability between them is relatively low, and on-site dust suppression efficiencies are typically only 40–60% [

9,

11].

Foam dust suppression technology leverages the advantages of gas–liquid two-phase foam, including strong adhesion, excellent wetting ability, extensive coverage, and good continuity. By forming a continuous foam layer over the cutting area via foam jetting, this method effectively reduces dust dispersion at the source. However, during operation, the cutting head is embedded in the coal–rock mass and performs high-intensity cutting, which limits the ability of the foam jet to penetrate and wet the interior of the cutting zone. As a result, coverage is largely restricted to the surface, and overall dust suppression efficiency typically ranges from 60% to 80% [

12,

13,

14,

15]. A dust extraction fan operates by drawing in dust-laden airflow and purifying it using internal filter screens or water mist. The dust removal efficiency of the extracted airflow can exceed 95% [

16,

17,

18]. However, the effective suction range of a dust extraction fan is limited, and its intake flow rate is often lower than the incoming airflow in the roadway, leaving a substantial portion of the dust-laden air unfiltered.

Ventilation-based dust control primarily uses auxiliary facilities such as wall-mounted air ducts and air curtains to regulate wind velocity distribution. This approach reduces airflow speed and turbulence intensity at key dust sources such as cutting, crushing, and loading points, thereby limiting dust diffusion. Moreover, by redirecting airflow, dust-laden air can be guided toward the inlets of the dust extraction fan or into spray zones, which enhances the overall effectiveness of dust suppression.

Previous research and technological developments in heading-face dust control have largely focused on axial roadheader operations. However, compared with roadheader working faces, continuous miner heading faces are characterized by significantly larger cross-sectional areas, higher airflow volumes, deeper cutting depths, higher dust generation rates, and fundamentally different excavation processes. As a result, dust control at continuous miner faces is considerably more challenging, and the performance of existing single dust suppression technologies remains unsatisfactory. Owing to the unique operating conditions at continuous miner working faces, the direct application of technologies that have proven effective for roadheader operations—such as foam dust suppression, airflow regulation, and dust extraction fan systems—is no longer sufficient. Achieving high-efficiency dust suppression under these conditions requires a comprehensive technological upgrade; however, relevant systematic studies remain limited.

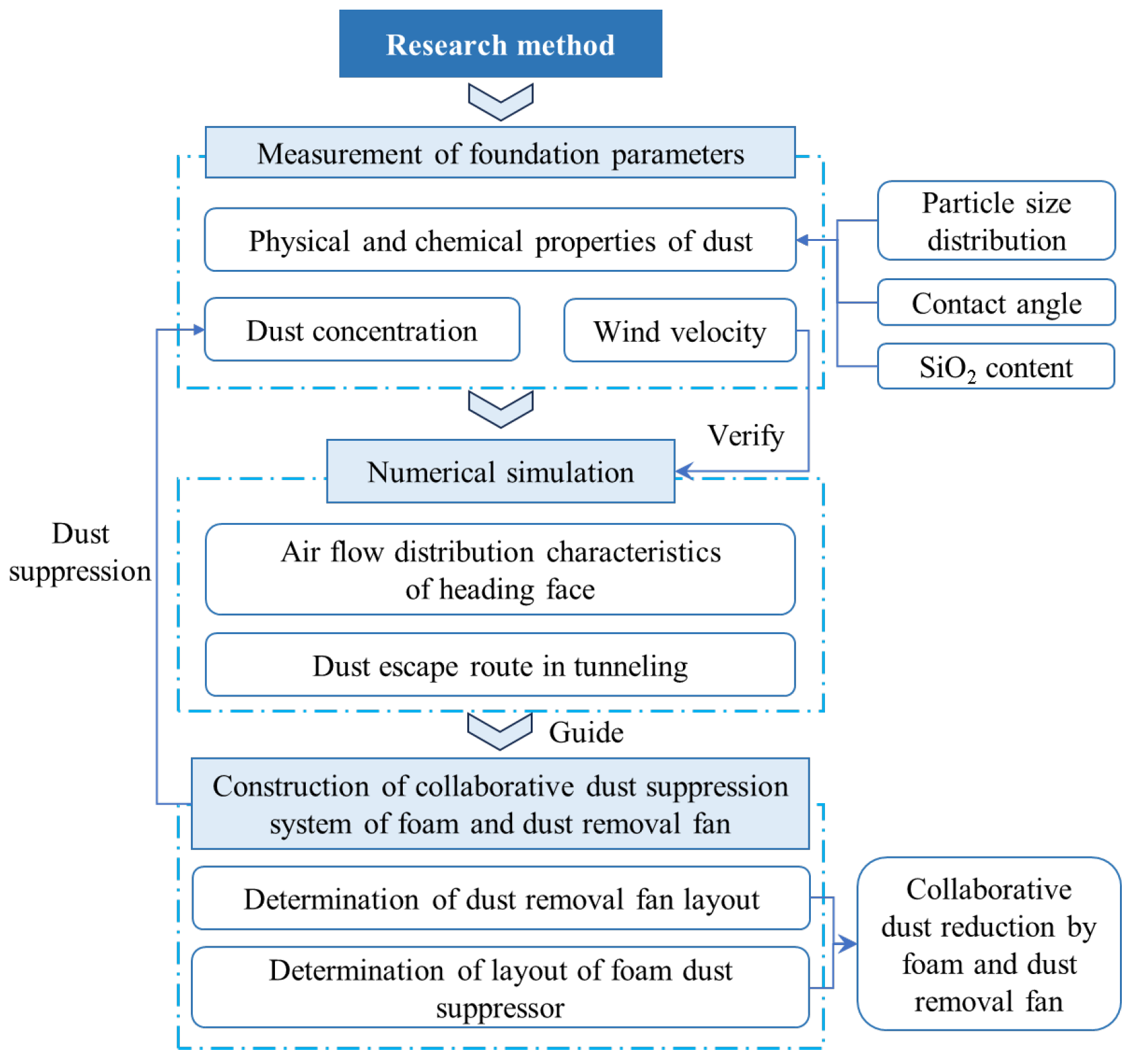

This study addresses the specific characteristics of continuous miner heading faces. It investigates airflow distribution in large-section tunneling environments and analyzes the influence of wall-mounted ventilation duct structures and layout configurations on airflow behavior. It further examines how dust extraction fan type and spatial arrangement affect dust extraction performance and develops a foam dust suppression system tailored to the structural configuration and cutting characteristics of continuous miners. On this basis, a comprehensive dust control system integrating ventilation regulation, foam suppression, and fan-assisted dust extraction is established. Field experiments are then carried out to evaluate the performance of the integrated system, providing practical guidance and theoretical reference for effective dust control at continuous miner tunneling faces.

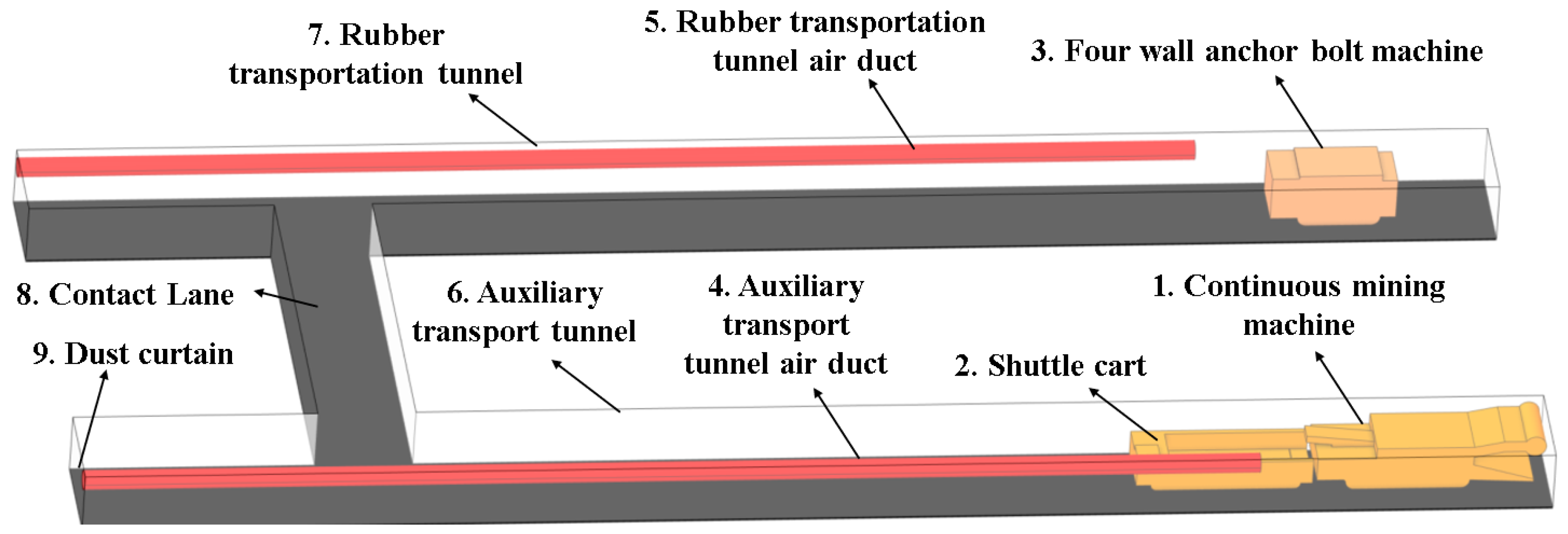

3. Original Airflow and Dust Characteristics at the Heading Face of a Continuous Miner

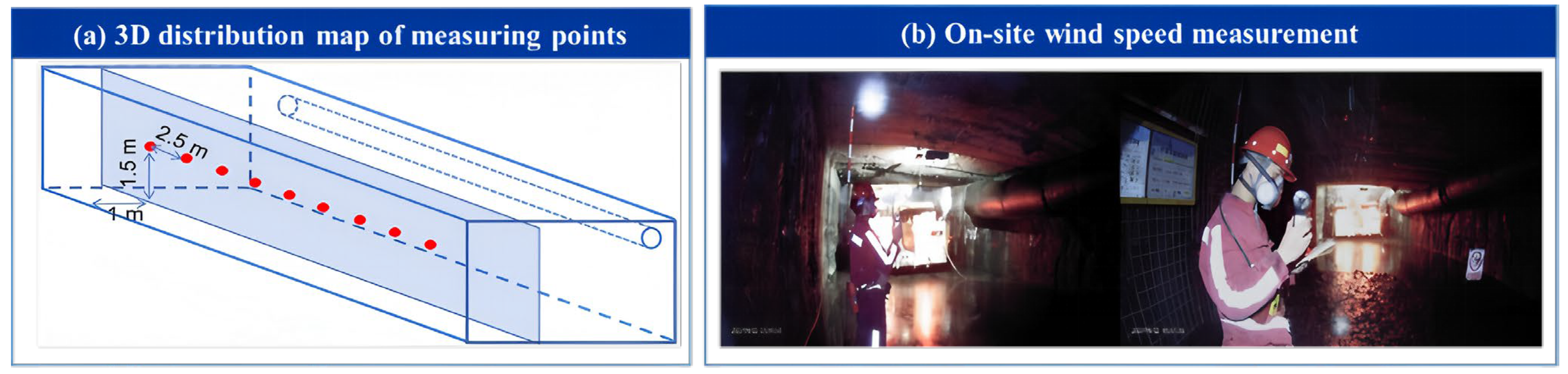

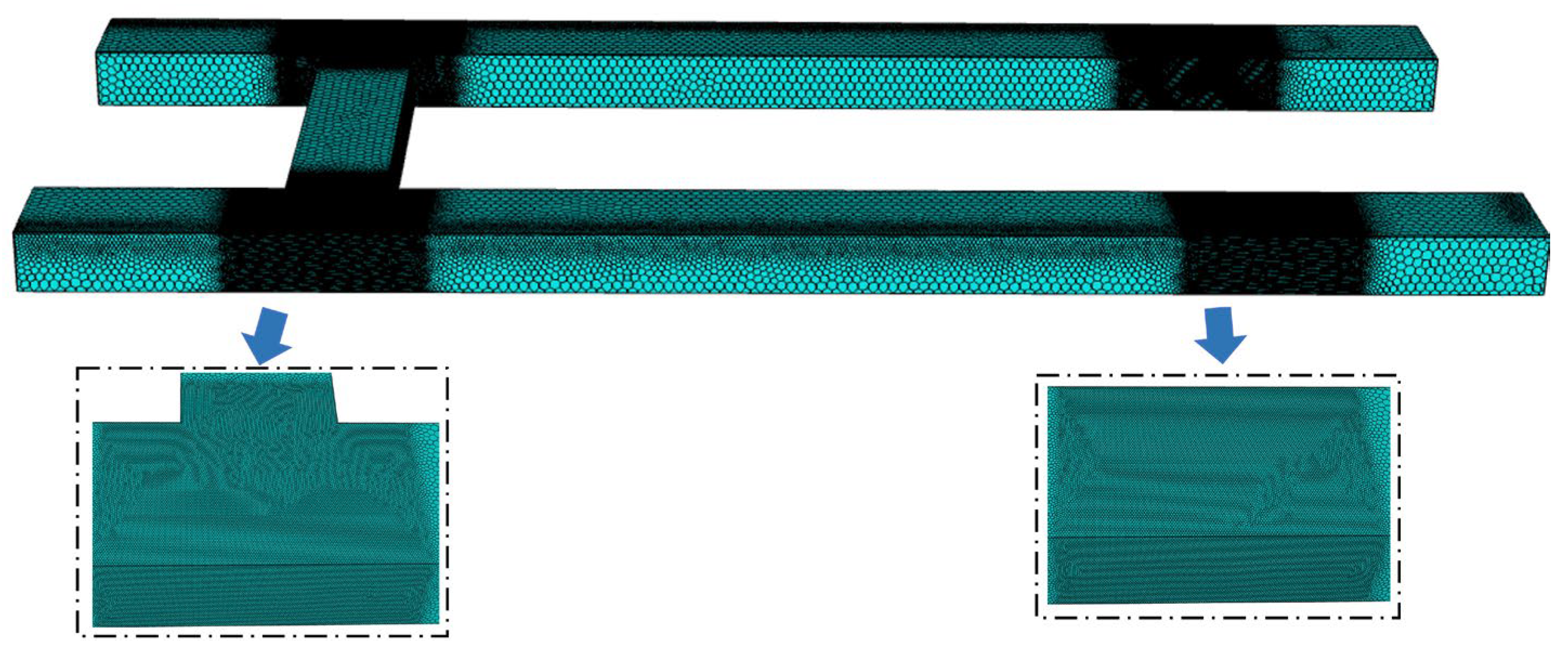

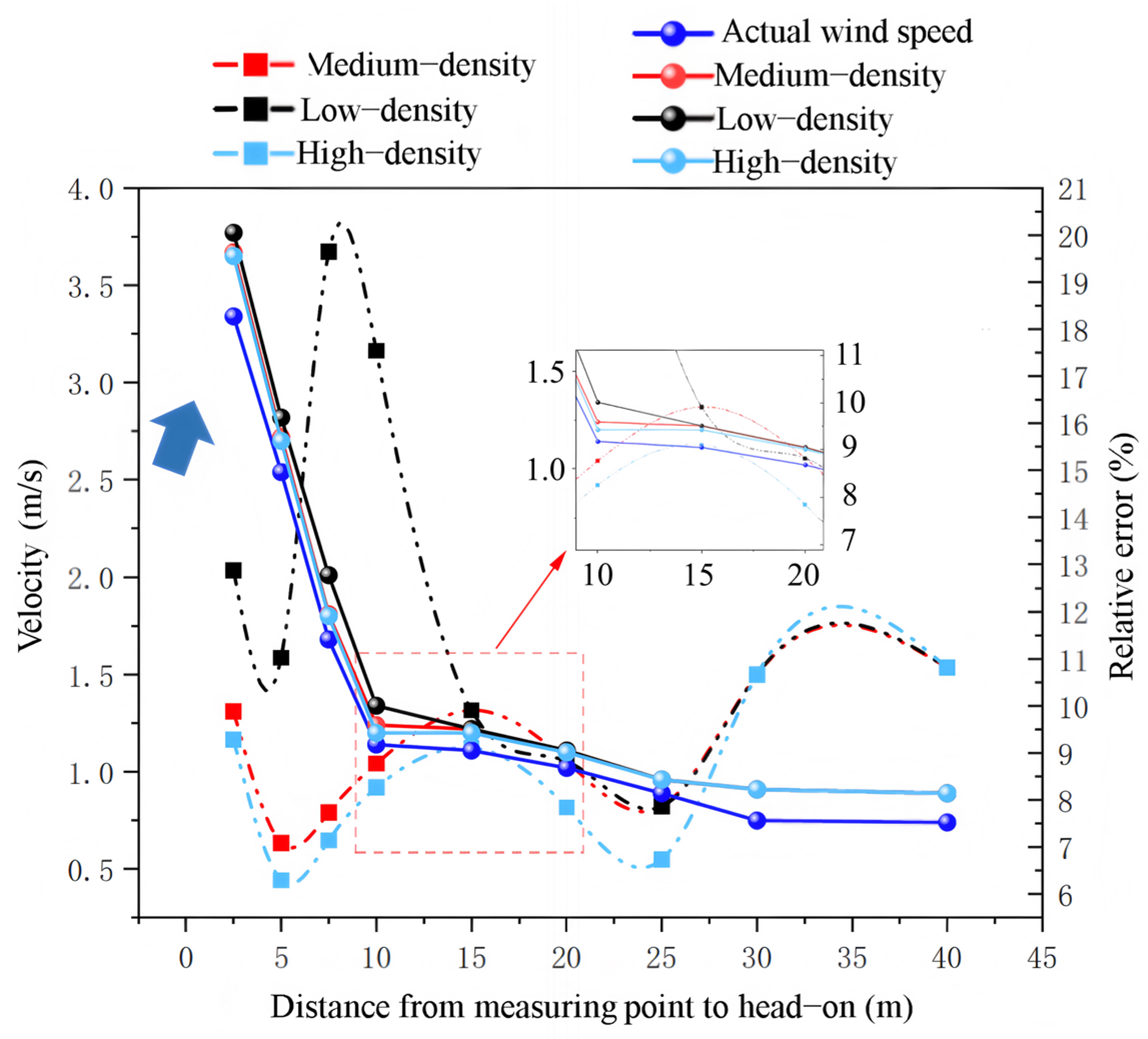

3.1. Wind Velocity Distribution Along the Roadway

As shown in

Table 5, the airflow velocity in the auxiliary transportation roadway decreases rapidly within 2.5–7.5 m of the excavation face. Beyond 10 m, the rate of decrease becomes significantly slower: for every additional 5 m, the velocity drops by no more than 0.3 m/s, with an average reduction of less than 0.15 m/s. In some locations, a slight local increase in velocity is even observed. Beyond 30 m, the airflow velocity approaches a stable state, with the average velocity difference between the 30 m and 40 m measurement points being only 0.01 m/s. These measurements provide reliable input data for both numerical calculation and model validation.

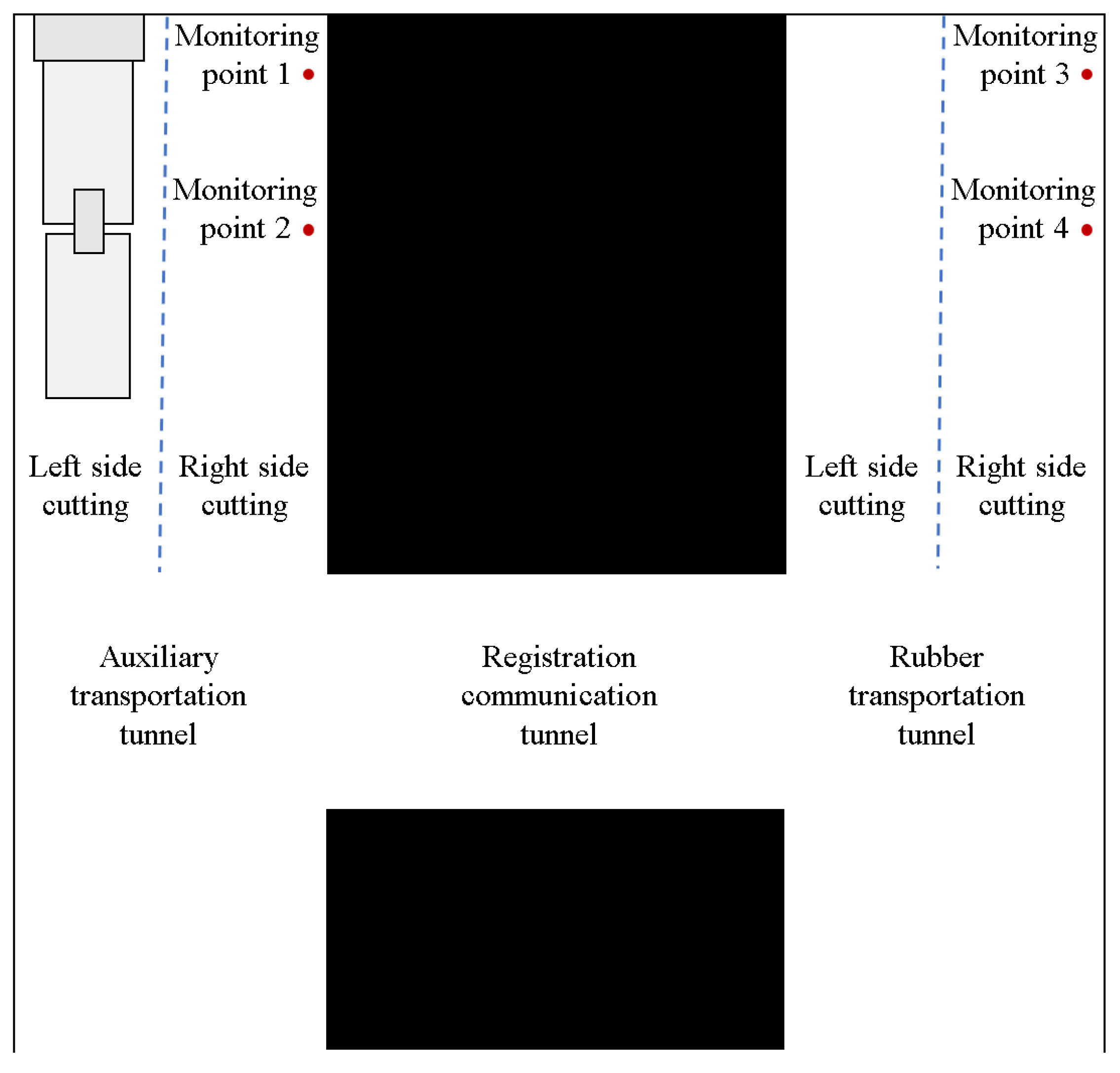

3.2. Original Dust Concentration at the Continuous Miner Heading Face

The dust concentration measurements are summarized in

Table 6 and

Table 7. The average total dust concentration for rock dust was 1044 mg/m

3, compared with 861 mg/m

3 for coal dust, representing a 21% increase for rock dust. The respirable dust concentration for rock dust was 27% higher than that for coal dust. This indicates that, under the same conditions (i.e., using only the original spray dust suppression system), rock cutting produces substantially more total dust and fine particulate matter than coal cutting, thereby posing a greater health risk.

We also observed that dust concentrations were generally higher when the continuous miner was cutting on the left side of the roadway than on the right side. During left-side advancement, the cutting zone is confined within the groove, where airflow influence is limited and dust disperses more slowly. In contrast, during right-side advancement, the cutting area is exposed directly to the airflow field, allowing dust to disperse more readily toward the operator position.

In the auxiliary transportation roadway, the increase in dust concentration during right-side advancement was more pronounced than in the belt roadway. In addition, dust concentrations at Sampling Points 3 and 4 in the belt roadway were significantly higher than those at Sampling Points 1 and 2 in the auxiliary transportation roadway—by 40% for rock dust and 26% for coal dust. This difference is primarily attributed to the layout of the ventilation ducts: in the auxiliary transportation roadway, the intake duct is located on the left side of the roadway, whereas in the belt roadway it is located on the right side. Consequently, in the auxiliary transportation roadway, high-concentration dust generated during right-side advancement is more readily transported by the left-sided airflow toward Sampling Points 1 and 2. In contrast, in the belt roadway, the right-sided airflow partially dilutes the dust-laden air.

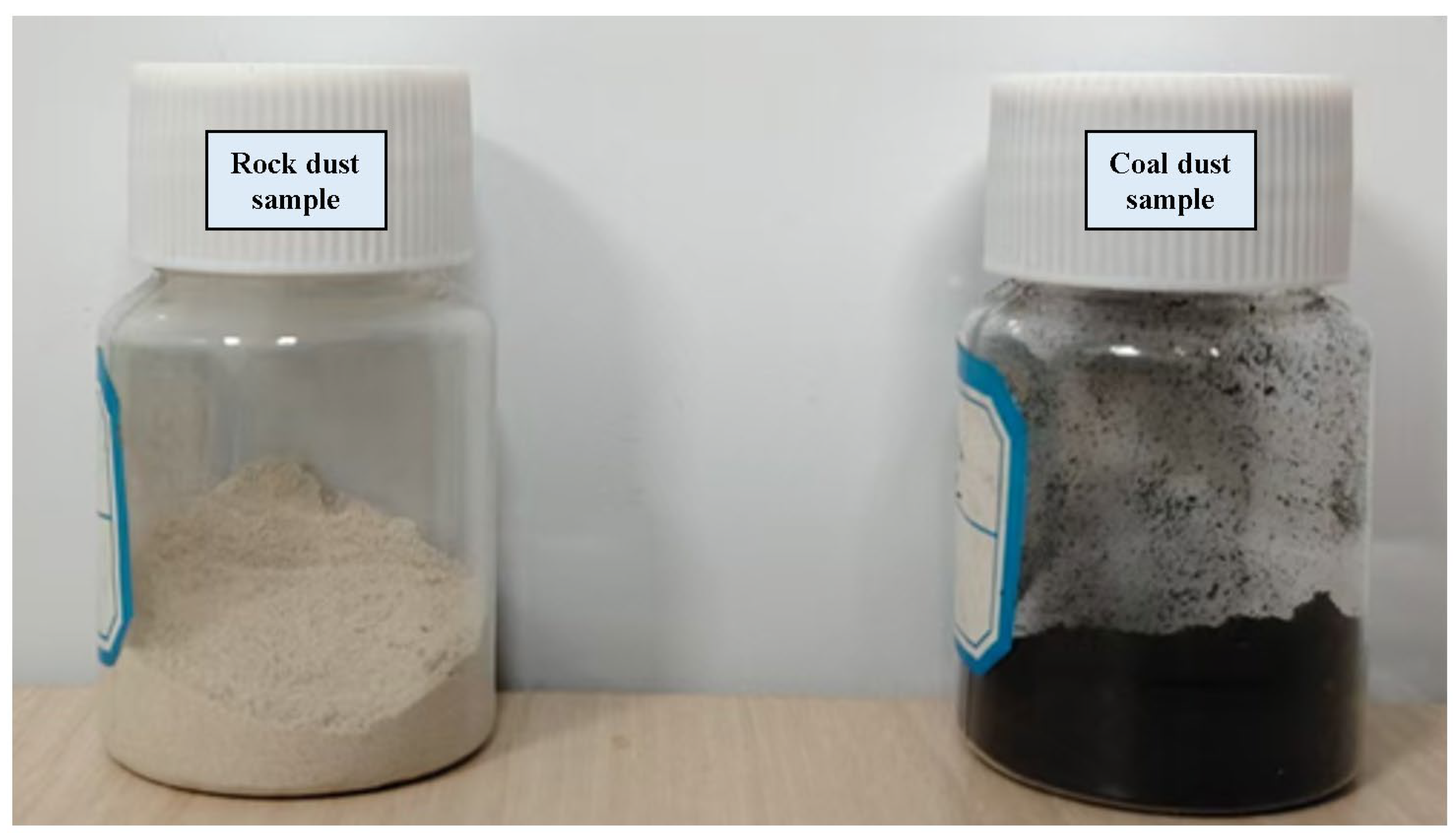

3.3. Physicochemical Properties of Dust

3.3.1. Particle Size Distribution Characteristics of Dust in the Roadway Heading Face

The particle size distribution test results are summarized in

Table 8. For the coal dust sample (M-01), the median particle size D50 is 44.60 μm, with D10 of 11.15 μm, D90 of 112.30 μm, and an average particle size D[4,3] of 35.98 μm. These values indicate that most particles fall within the coarse respiratory-dust range (10–75 μm), which settle relatively quickly but may remain airborne long enough to impair visibility and local air quality. A smaller fraction of <10 μm dust still exists, posing inhalation hazards to the upper respiratory tract [

27,

28,

29].

In contrast, the rock dust sample (R-01) is much finer, with D50 of 7.75 μm, D10 of 1.95 μm, D90 of 18.50 μm, and an average particle size D[4,3] of only 6.83 μm. Such fine particle size leads to a high lung deposition rate and facilitates penetration beyond the protective barriers of the human respiratory system, posing substantial health risks [

29,

30]. In addition, particles in the range of 10–75 μm are also considered to be the most explosive part in the restricted mine environment, and the 50 μm particle size dust explosion is the most severe, which highlights the dual hazards of fine mineral dust in underground operations [

31,

32,

33,

34].

Although large-particle coal dust settles rapidly, it can remain suspended in the work environment for a certain period, impairing air quality and visibility. By comparison, the finer particle size of rock dust makes it more easily inhaled and more likely to deposit in deep regions of the respiratory tract, such as the alveoli. Long-term accumulation can induce severe pathological changes, including pulmonary fibrosis, thereby threatening the health of operators.

Regarding dust mitigation, conventional water-spray and foam systems perform effectively on coarse particles (>20 μm) due to efficient collision and agglomeration. However, their efficiency decreases markedly for ultrafine respirable dust (<10 μm), comprehensive dust control technology integrating dust reduction, dust suppression and dust removal is required.

3.3.2. Free Silica Content in Dust from the Roadway Heading Face

The test results for free silica content are summarized in

Table 9. For the coal dust sample (M-01), the free silica content determined by the infrared method and the XRD method is 6.2% and 5.8%, respectively, which falls within the low-content range. Nevertheless, prolonged exposure to a coal dust environment containing even low concentrations of free silica can still lead to occupational diseases such as coal worker’s pneumoconiosis and therefore cannot be overlooked. In contrast, the free SiO

2 content in the rock dust sample (R-01) is substantially higher. The values measured by the infrared method and the XRD method are 32.7% and 33.1%, respectively, indicating a high level of occupational health risk. Long-term exposure to such dust may result in severe health outcomes, including silicosis [

35,

36].

3.3.3. Hydrophobicity and Hydrophilicity Analysis of Dust in the Roadway Heading Face

The surface wettability of dust is a key factor determining foam film stability and dust capture efficiency during foam dust suppression. In general, the more hydrophobic the coal dust is, the lower the efficiency of foam dust suppression. The contact angle test results are summarized in

Table 10. The coal dust sample (M-01) exhibits a contact angle of 108.7°, indicating strong hydrophobicity. Such dust is not easily wetted by water mist, tends to remain airborne, and readily disperses throughout the roadway, thereby increasing the difficulty of dust control. In wet dust removal processes such as spray dust suppression, ordinary water mist is ineffective at capturing highly hydrophobic coal dust. As a result, dust removal efficiency is low and repeated treatment is required, increasing labor and resource cost. In contrast, the rock dust sample (R-01) has a contact angle of 68.4°, indicating hydrophilicity. This type of dust can be more effectively captured by wet dust removal measures, which helps reduce airborne dust concentrations in the working environment [

37,

38].

The comparative analysis of physicochemical properties reveals distinct challenges in controlling coal dust and rock dust at the roadway heading face. Coal dust particles are relatively coarse, with moderate free silica content but strong hydrophobicity. As a result, coal dust remains airborne for a limited period but is difficult to wet using conventional water mist, which reduces the effectiveness of wet suppression techniques. Therefore, coal dust control should focus on improving wetting performance—for example, through surfactant-assisted spraying or foam dust suppression—to overcome hydrophobicity and enhance dust capture efficiency.

In contrast, rock dust is characterized by ultrafine particle sizes, very high free silica content, and hydrophilic behavior. Its fine particle size increases the likelihood of deep pulmonary deposition and raises the risk of severe occupational diseases such as silicosis. Although its hydrophilicity enables effective suppression using conventional wet methods, the high toxicity and persistence of respirable rock dust require more stringent protective measures. Engineering controls such as enhanced ventilation, localized dust extraction, and real-time monitoring of silica concentrations should be implemented in combination with wet suppression to reduce health risks.

3.4. Wind Flow Distribution Under Different Working Conditions

Figure 10a,b shows the overall airflow vector fields for left-side advancement and right-side advancement, respectively. For left-side advancement, when the high-velocity jet from the duct outlet (peak velocity 12 m/s) impinges on the roadway face, intense shear flow is generated. Under the combined influence of the confined roadway geometry and local pressure gradients, the jet undergoes pronounced lateral deflection, gradually attaches to the roadway wall, and rotates. At 3 m above the floor, where the influence of the continuous miner and shuttle car is relatively limited, the airflow from the duct can propagate toward both the return and intake sides with a velocity of approximately 6 m/s. In this region, partial merging with the incoming jet produces vortical structures. At 2 m and 1 m above the floor, the airflow is directed mainly toward the return side. A portion of the stream bypasses the continuous miner through the gap between the machine and the wall, adheres to the return sidewall, and then converges with the return airflow impinging on the face near the shuttle car. This interaction generates several small-scale vortices, which subsequently develop into a larger vortex in front of the shuttle car before gradually diffusing toward the intake side.

For right-side advancement, when the continuous miner shifts from the left side to the right side of the roadway, it obstructs the airflow discharged from the duct. As a result, the high-velocity jet becomes confined within the roadway space at 3 m above the floor. After impinging on and reflecting from the roadway face, the airflow undergoes kinetic energy dissipation and then disperses more uniformly in the space behind the shuttle car. At 2 m and 1 m above the floor, the airflow emerging from the duct interacts with the flow leaking through gaps in the miner and with the recirculating flow in front of the machine. The collision of these streams generates vortices near the shuttle car on the intake side. On the return side, after bypassing the continuous miner, the airflow rapidly diffuses toward the intake side.

After passing through the equipment area, the airflow experiences a sudden expansion of the roadway cross-section. This expansion causes part of the flow to deflect toward the intake side, while most of the airflow remains concentrated near the floor. Beyond 30 m from the working face, the airflow gradually diffuses and becomes relatively uniform across the roadway.

3.5. Dust Migration and Dispersion Patterns Under Different Operating Conditions

Dust particles generated at the excavation face exhibit characteristic migration patterns driven by the airflow field. Initially, fine particles produced by coal and rock breakage are entrained and transported downstream by the primary airflow. Owing to roadway geometry and the presence of mining equipment, local vortex structures form in the flow field. These vortices partially confine and recirculate dust, while the remaining particles continue to disperse along the main airflow direction. The dust migration and dispersion patterns at the working face during left-side advancement and right-side advancement are shown in

Figure 11a,b.

From 10 s to 20 s, dust particles are primarily concentrated around the continuous miner and the shuttle car, with relatively high concentrations near the return sidewall. After passing the shuttle car, most of the dust gradually shifts from the roadway walls toward the roadway center. Notably, during right-side advancement, dust migration in the auxiliary transportation roadway occurs more slowly than during left-side advancement, and dust generated under right-side advancement tends to accumulate above the shuttle car.

From 30 s to 40 s, during left-side advancement, dust is entrained by airflow from the duct into the connecting roadway and is mainly distributed near the roadway center in an approximately conical pattern. In contrast, during right-side advancement, most dust remains near the continuous miner and the shuttle car, with only a small fraction reaching the intersection of the auxiliary transportation roadway and the connecting roadway.

From 50 s to 60 s, under left-side advancement, dust is diverted within the connecting roadway. Due to the presence of the dust curtain at the outlet of the auxiliary transportation roadway, airflow in the rear section of the auxiliary transportation roadway is impeded. As a result, substantially more dust exits through the connecting roadway and the belt roadway than directly through the auxiliary transportation roadway. Under right-side advancement, only a small portion of dust is transported into the connecting roadway and into the rear section of the auxiliary transportation roadway.

From 90 s to 120 s, most dust reaches the roadway intersection. Under right-side advancement, the amount of dust present in the connecting roadway is higher than under left-side advancement. The spatial distribution is similar to that observed at 60 s in the left-side advancement condition, but with fewer particles near the outlet boundary.

The overall dust distribution in the roadway under the two operating conditions is shown in

Figure 11c,d. In both cases, most dust is concentrated in the front section of the auxiliary transportation roadway, with pronounced accumulation along the auxiliary transportation roadway walls and around the shuttle car and the continuous miner. In addition, elevated dust concentrations are observed near the floor in the rear section of the belt roadway near the outlet. Compared with left-side advancement, right-side advancement results in greater dust accumulation at the bottom of the connecting roadway and around the shuttle car and continuous miner.

4. Construction and Effectiveness Verification of the Foam-Dust Extraction Fan Collaborative Dust Reduction System

4.1. Layout Strategy and Airflow Control for Dust Extraction Fans

The key factors governing the dust suppression efficiency of a dust extraction fan are primarily the fan airflow volume and its installation position. Based on the results presented in

Section 3.4 and

Section 3.5, optimal dust reduction is achieved when fans are installed near the continuous miner and positioned radially at either the midpoint or the return-air side of the auxiliary transportation roadway. In addition to the onboard fans mounted on the continuous miner, the placement and airflow capacity of fans in the auxiliary transportation roadway must therefore be determined with precision. To this end, different airflow volumes were evaluated at two installation positions (midpoint and return-air side of the auxiliary transportation roadway) to identify the optimal combination for maximizing dust suppression.

Five airflow volumes were tested: 100 m

3/min, 200 m

3/min, 300 m

3/min, 400 m

3/min, and 500 m

3/min. For intuitive comparison of cross-sectional dust concentration distributions, the fan duct position was defined as X = 0 m, and sampling cross-sections were established every 2 m in the direction extending downstream from the fan. Each sampling plane collected 40,000 data points to obtain the average dust concentration, as summarized in

Table 11. The dust extraction fan achieved the highest dust suppression efficiency at an airflow rate of 500 m

3/min, regardless of whether it was positioned at the midpoint of the roadway or on the return-air side, yielding efficiencies of 70.3% and 69.2%, respectively. When the airflow rate was below 500 m

3/min, the suction capacity was insufficient to effectively capture dust particles. When the airflow rate exceeded 500 m

3/min, the fan size became impractical for deployment at the tunneling face.

At the optimal airflow rate of 500 m

3/min, the spatial distribution of dust concentration across the tunnel cross-section is shown in

Figure 12. When the dust extraction fan is installed in the middle of the tunnel, dust particles are drawn toward the fan duct under negative pressure, forming localized high-concentration dust clouds. Both the spatial distribution patterns and the average concentration measurements indicate that this configuration provides moderate effectiveness in controlling dust in the rear section of the auxiliary transportation roadway. However, apart from coarse particles that have already settled on the floor, areas of elevated dust concentration persist near the tunnel center, indicating that dust capture efficiency is not yet fully optimized. In contrast, when the fan is positioned on the return air side, the relatively higher airflow velocity near the tunnel center promotes dust dispersion after partial extraction by the fan duct. Spatial and statistical analyses show that this arrangement achieves dust suppression performance comparable to that of the central installation, with no significant difference in overall effectiveness.

4.2. Optimization of Dust Extraction Fan Selection and Positioning at the Tunneling Face

The configuration and overall layout of the underground dust removal systems are shown in

Figure 13. In the auxiliary transportation roadway, dust control is implemented through an integrated approach that combines on-board foam dust suppression technology with two strategically positioned fans: Fan 1, a ground-installed central extraction unit, and Fan 2, a machine-mounted auxiliary unit. In the belt roadway, dust mitigation is achieved through a coordinated system that couples on-board foam dust suppression technology with the localized extraction capability of Fan 2.

Field measurements indicate that during bolter operation, a 1.5 m lateral clearance is maintained on both sides of the roadway, while the shuttle car requires a 3 m lateral clearance on one side. The dust extraction fan is installed on the floor on the side opposite the supply air duct, adjacent to the rib, thereby ensuring adequate operational safety margins. In the optimized configuration, the dust extraction fan is positioned on the floor opposite the supply duct (near the rib), with its inlet connected to an S-shaped elbow and then to a negative-pressure duct (diameter: 0.8 m; segment length: 5 m) that extends to within 5 m of the tunnel face (

Figure 14).

The installation of the floor-mounted dust extraction fan (Fan 1) is carried out by anchoring 3 m rail segments to the roof mesh using adjustable chains along the rib. Consecutive rail segments are extended toward the excavation face, maintaining a uniform elevation, until they reach within 5 m of the face. Pulleys are engaged with the rail grooves to suspend the negative-pressure ducts (∅0.8 m) using tensioned steel wires, which are then advanced forward so that the duct inlet can be positioned at the face and secured with wire fasteners. To enhance dust capture, a 5 m attached wall duct (∅1 m) is installed at the terminus of the supply duct. In field application, wet cyclonic dust extraction fans are arranged at distances of 5 m, 32 m, and 59 m from the connecting roadway, and are advanced in 27 m increments in coordination with tunneling progress (

Figure 15).

As shown in

Figure 15b, the onboard dust extraction fan (Fan 2) was originally mounted above the conveyor chute of the continuous miner. However, this configuration frequently resulted in impacts from falling rock and vibration-induced structural damage to the chute. To resolve these issues, the collector was relocated to the upper left side of the miner frame, where welded support brackets and protective guardrails were added to improve impact resistance and structural stability. In addition, the control switches and water valves were repositioned near the operator’s cab using custom-mounted brackets, which significantly improved operational accessibility. To enhance dust control performance, a left-oriented elbow was installed at the exhaust outlet to prevent the exhaust jet from re-entraining dust on the conveyor chute. At the air intake, an attached wall duct was added to convert the axial flow into a radial discharge pattern, thereby improving dust capture efficiency near the cutting face. These modifications ensured reliable dust extraction without interfering with normal mining operations while preserving sufficient operating space.

4.3. Layout and Optimization of Foam Dust Suppression System

The foam dust suppression system uses the working face water supply (3 MPa) and compressed air (0.6 MPa) as media sources. The host unit automatically mixes water, foaming agent, and air at predetermined ratios to generate high-performance dust-suppressing foam. The foam is then delivered through high-pressure hoses to foam injection valve blocks and finally sprayed via specialized nozzles onto the continuous miner’s cutting drum, achieving full coverage of the dust source.

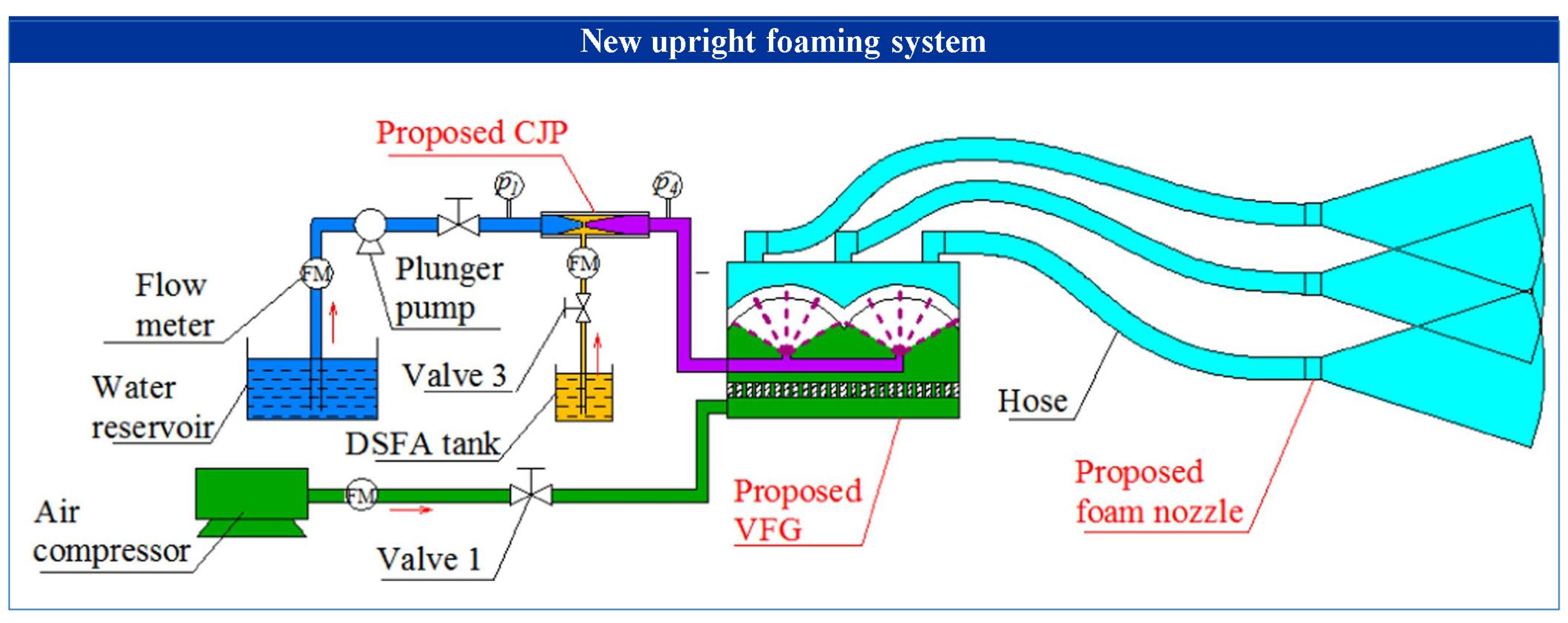

To address spatial constraints at the tunneling face and reduce pressure loss, a shock-resistant integrated foaming system was developed (

Figure 16). A new vertical foam generator (VFG) is integrated into the foam generation chamber, as shown in

Figure 17. Key components of the conventional system—including the traditional jet pump, horizontal foam generator (HFG), and foam nozzle—were replaced with a cavitating jet pump (CJP), the VFG, and a 3D-printed nozzle, respectively. Because the cross-sectional area of the VFG is four times that of the HFG, the pressure loss across the VFG is 22% lower than that across the HFG, as determined from pressure measurements at the inlets and outlets of the foam generators. High-pressure water and compressed air provide the driving energy for the system. As high-pressure water flows through the CJP, a negative pressure is created at the inlet of the DSFA line, which entrains the DSFA into the system. Valve 3 regulates the DSFA flow rate. The DSFA solution mixes with compressed air and is conveyed through a hose to the foam nozzle, where foam is generated and subsequently applied directly to the dust source for suppression. When the supplied water and/or air pressure exceeds the required operating pressure, it can be reduced by partially closing Valves 1 and 2, respectively. Critical dimensional parameters are summarized in

Table 12. The outer shell of the foam generation chamber is constructed from 06Cr19Ni10 stainless steel with an 8 mm wall thickness. The integrated unit has compact overall dimensions of 840 × 540 × 700 mm and delivers a foam output of 85 ± 5 m

3/h at 1.5 MPa water pressure and 0.6 MPa air pressure. The generated foam exhibits an expansion ratio of 35 × (ASTM D1881) [

39] and a half-life greater than 22 min, exceeding the MT/T 240 standard [

40] (

Table 13). The integrated 75° dispersion-angle flat-fan nozzles provide an effective coverage area of 5.2 m

2 at a range of 3 m, ensuring full coverage of the cutting heads.

The foam tank is mounted on the left side of the operator’s platform (500 × 500 × 400 mm) to avoid obstructing the operator’s view and to prevent collision with falling rock debris. An on-off valve is installed in the cab and connected to the tank via a DN19 high-pressure rubber hose. The tank outlet is connected to the foam distributor through a DN51 elbow and rubber hose, and the distributor outlet is connected to four DN25 × 5 m delivery pipes. These pipelines are routed along the lower part of the continuous miner’s cover plate to the nozzle valve block, which is welded to the front edge of the cover plate to minimize impact from rock debris.

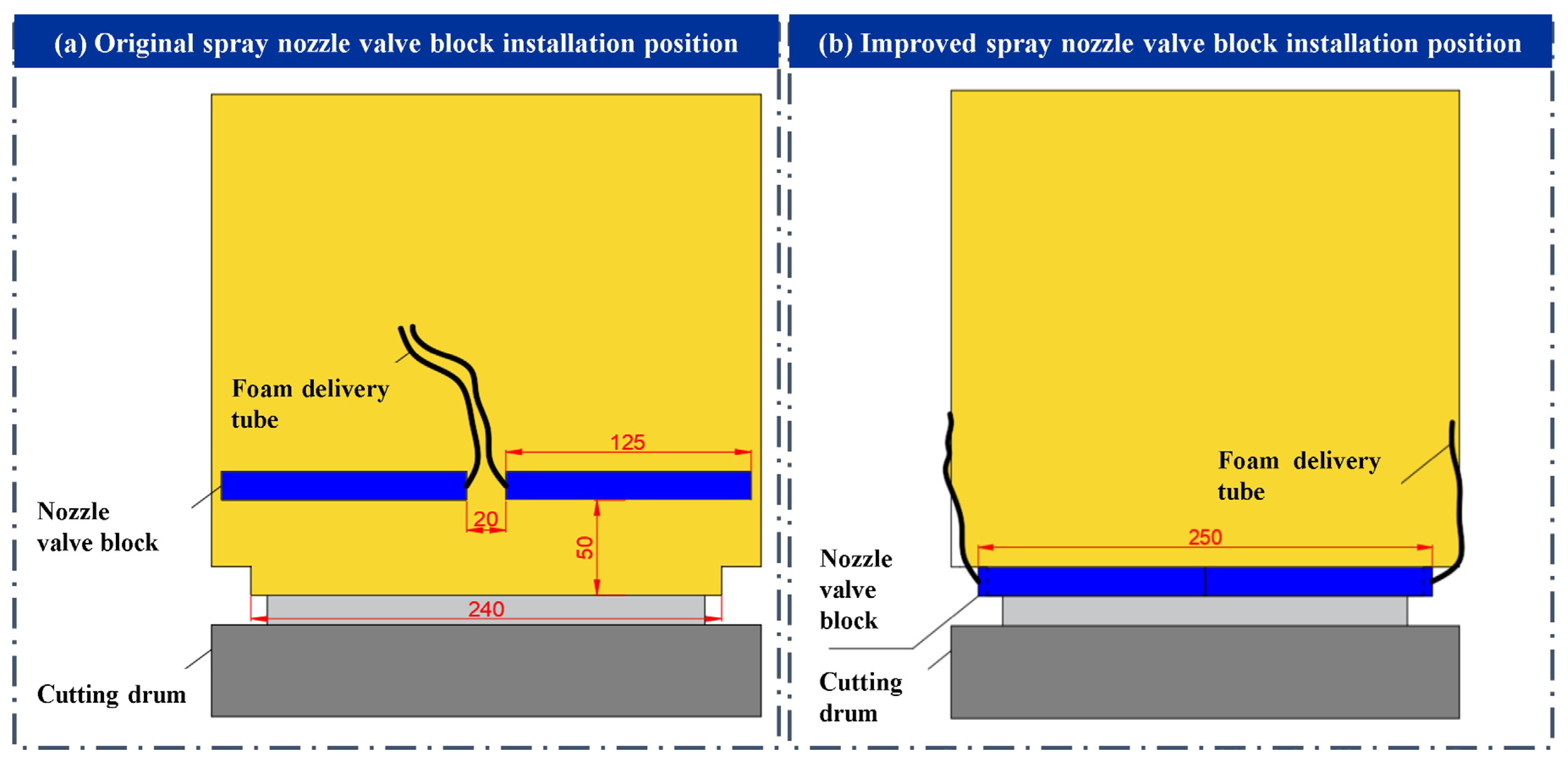

During field verification of the foam dust suppression system, it was observed that broken coal slag and dust readily accumulated on the continuous miner’s cover plate in front of the nozzle valve block, preventing foam from adequately covering the cutting drum. Operational issues included insufficient foam suction flow and discontinuous foam coverage on the drum surface. To address these problems, system performance was improved through structural modifications and parameter adjustments. The specific optimization measures are as follows:

- (1)

Nozzle valve block clogging: The position of the nozzle valve block was adjusted to the front edge of the continuous miner’s cover plate (

Figure 18) to prevent coal slag accumulation from blocking the spray. To quantitatively evaluate the likelihood of nozzle blockage before and after optimization, the foam system was activated at the end of each cutting cycle, and the number of blocked nozzles was recorded. A total of 60 cutting cycles were examined for both the pre-optimization and post-optimization configurations. The blockage rate was calculated as the total number of blocked nozzles divided by the total number of nozzles over 60 cutting cycles (60 × 8 = 480). Before optimization, the nozzle blockage rate was 8.96%. After relocating the nozzle valve block, the blockage rate decreased to 2.92%, representing a 67% reduction. Following optimization, the effective coverage area within a 3 m range remained 5.2 m

2, satisfying the requirement for complete coverage of the cutting head.

- (2)

Insufficient foam continuity: The foam liquid suction flow in the foam tank was adjusted to produce a continuous foam layer on the cutting drum surface, thereby resolving the problem of intermittent spraying.

- (3)

Pipeline connection and protection: Identification markings were added at the valve block connections to prevent misconnection of the air and water lines. High-pressure rubber hoses were standardized to DN specifications to ensure compatibility with the existing piping system in Weiqiang Mine. The tank wall thickness was increased to 8 mm (overall size: 50 cm × 50 cm × 40 cm), and a protective cover was installed over the control valve to reduce the risk of impact damage from falling rock.

- (4)

Component durability improvement: The hex socket screws on the tank cover were replaced with hex bolts to prevent thread stripping. A filter screen was installed at the inlet of the liquid suction pipe, and the foaming agent formulation was modified to reduce sediment-induced clogging.

- (5)

Spray parameter optimization: The nozzles were upgraded to conical diffusion nozzles (dispersion angle 60–90°) with integrated self-cleaning filters (≥200 mesh). The nozzle array was repositioned outward to the front section of the cutting arm (≤0.5 m from the cutting head), and adjustable pressure plates were added to the bracket to enable fine adjustment of the spray direction (angle tolerance ≤±3°).

After optimization, system performance improved significantly: the total dust suppression rate increased from 68% to 78%; cutting tool wetting coverage increased from 70% to 95%; nozzle clogging was eliminated; and the liquid film remaining after foam rupture continuously coated the surface for ≥10 s, achieving both pre-wetting of the cutting tools and sealing of newly generated dust.

4.4. Verification of Cumulative Dust Suppression Effects Between Foam and Dust Extraction Fans

To systematically evaluate the dust suppression performance of different equipment configurations, comparative experiments were conducted under four conditions: (1) baseline dust concentration measurement prior to any treatment; (2) combined application of the foam system and the floor-mounted dust extraction fan; (3) comprehensive deployment of foam, floor-mounted dust extraction fan, and onboard dust extraction fan; and (4) a control condition simulating improper installation of the foam + floor-mounted dust extraction fan combination. The quantified results of these tests are presented in

Table 14, demonstrating the operational advantages of the optimized equipment synergy in underground mining environments.

The data in

Table 15 show that, in the auxiliary transportation roadway, the original system alone achieved dust removal efficiencies of 30% for both total dust and respirable dust. The foam + floor-mounted dust extraction fan configuration increased the removal efficiencies to 90% for total dust and 84% for respirable dust, while the foam + onboard dust extraction fan + floor-mounted dust extraction fan configuration further improved these values to 93% and 86%, respectively. In the belt roadway, the original system achieved removal efficiencies of 34% for total dust and 31% for respirable dust. The foam + floor-mounted dust extraction fan configuration resulted in efficiencies of 84% for total dust and 51% for respirable dust, whereas the foam + onboard + floor-mounted dust extraction fan combination achieved 95% and 87%, respectively. These results demonstrate that the cumulative dust suppression system substantially improves dust reduction performance. However, improper installation of the floor-mounted dust extraction fan can significantly reduce effectiveness: field data indicate that total dust removal efficiency dropped from 90% to approximately 72%, and respirable dust removal from 84% to about 62%. This underscores the critical importance of proper installation (

Table 15).

To further evaluate the technological advancement of the proposed system, its performance was compared with both conventional dust control methods—including spray dust reduction, foam dust removal, and wet dust removal technologies [

41,

42,

43,

44,

45,

46]—and recently developed technologies such as cloud dust removal technology and self-powered induction spray dust removal systems, as summarized in the table. The results show that the dust extraction fan + foam dust suppression combination achieves substantially higher dust removal efficiency than either traditional or emerging technologies. In addition, a comparison of visibility at the heading face before and after applying the dust extraction fan and foam dust suppression, as shown in

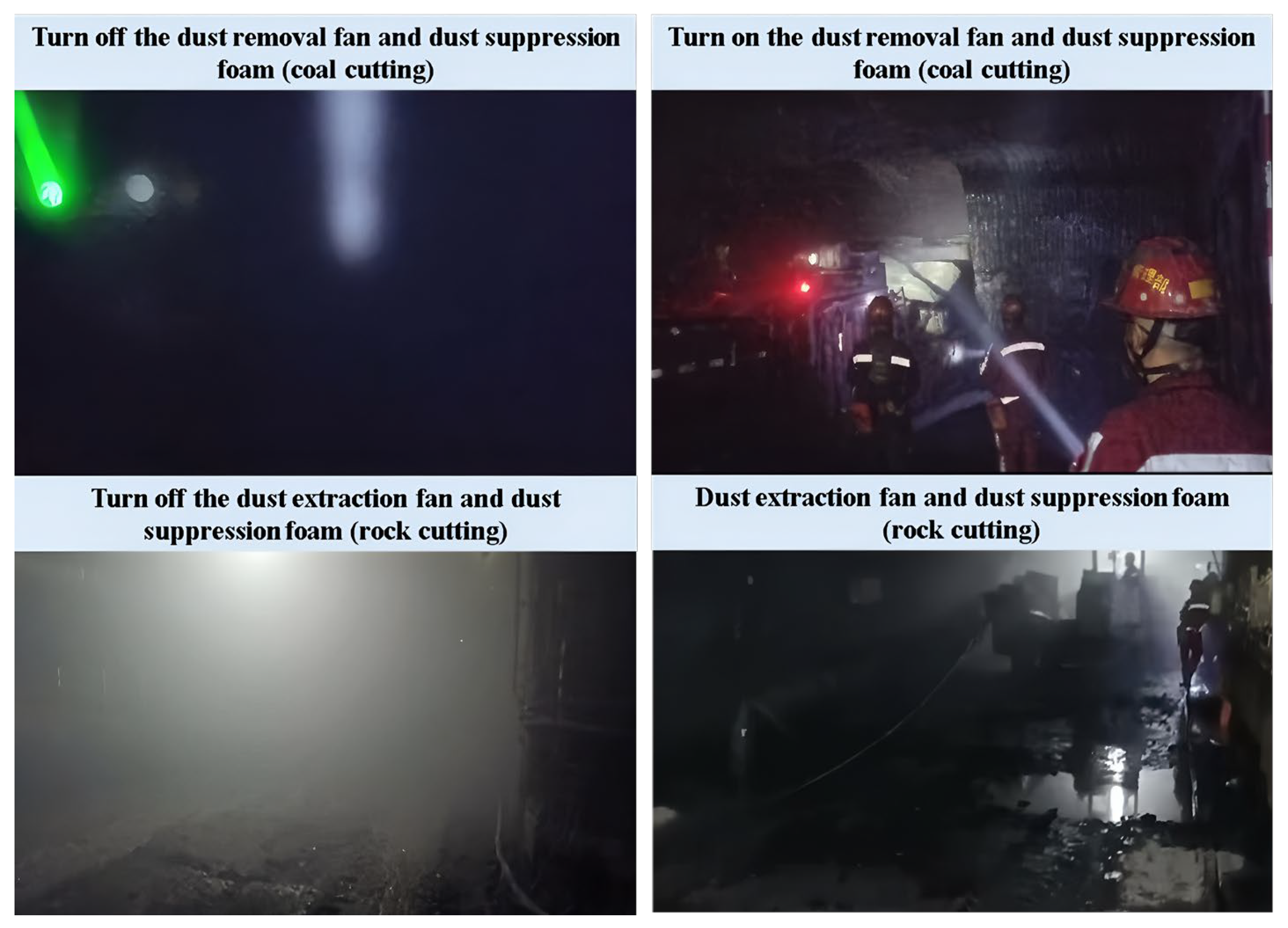

Figure 19, demonstrates a marked improvement in visual clarity around the continuous miner when the proposed system is in use.

All dust concentration data reported in this study represent instantaneous concentrations generated during coal and rock cutting by the continuous miner. In contrast, both domestic and international Occupational Exposure Limits (OELs) for respirable dust are defined in terms of time-weighted average (TWA) concentrations, as summarized in

Table 16.

At the Weiqiang Coal Mine, each 24-h period consists of one maintenance shift (8 h) and two production shifts (8 h each). During each production shift, the continuous miner completes three tunneling cycles, alternating between the belt roadway and the auxiliary transportation roadway, with each cycle lasting approximately 40 min. Because little dust is generated when the miner is idle or not cutting, the time-weighted average (TWA) dust concentration during production shifts was estimated proportionally based on the active cutting duration, as shown in the second column from the right in

Table 16.

When the foam dust suppression system, onboard dust extraction fan, and floor-mounted dust extraction fan operated simultaneously, the respirable dust TWA concentration in the belt roadway and the auxiliary transportation roadway ranged from 2.81 to 3.94 mg/m3. Considering that the rock layer thickness to be cut at the Weiqiang 3305 heading face is less than 1 m, whereas the coal seam thickness ranges from 2.2 to 2.4 m, more than two-thirds of the suspended dust in the roadway is coal dust.

Given that the measured free SiO

2 content in coal dust was 5.8–6.2% and that in rock dust was 32.7–33.1% (

Table 4), the post-treatment dust concentrations comply with the requirements of China (AQ 4203-2008) [

51]. However, they still exceed the permissible exposure limits specified in China (GBZ 2.1-2019) [

47], as well as U.S. NIOSH [

48] and U.S. OSHA standards [

49,

50]. This indicates that further optimization of dust control technologies is required to meet international occupational health benchmarks.

4.5. Limitations of the Proposed Dust Suppression System

Although the combined use of the onboard dust extraction fan, floor-mounted dust extraction fan, foam dust suppression system, and attached air duct significantly reduces dust concentration at the continuous miner working face, the integrated dust suppression system still requires optimization and adaptation under different roadway advancement conditions due to the following limitations:

(1) Mobility of the floor-mounted dust extraction fan

The floor-mounted dust extraction fan must be continuously advanced as the roadway progresses. At present, it is mainly dragged forward by the continuous miner, which is time-consuming and labor-intensive. The development of a self-propelled floor-mounted dust extraction fan would greatly improve operational efficiency and convenience.

(2) Spatial constraints for equipment arrangement

When arranging the floor-mounted dust extraction fan, sufficient space must be reserved for the operation of the continuous miner, shuttle car, and bolter. If the roadway width is insufficient, the fan cannot be properly installed. In such cases, the air-handling capacity of the onboard dust extraction fan should be enhanced to compensate.

(3) Protection under unstable roof conditions

During excavation, large rock fragments may fall from unstable roofs and strike the onboard dust extraction fan, potentially causing structural damage. Therefore, the external dimensions and protective housing of the onboard dust extraction fan should be designed with full consideration of the continuous miner’s geometry and the impact characteristics of falling rock.

(4) Variation in water quality for dust suppression

The concentration and composition of electrolytes in dust suppression water vary among mines. To prevent degradation of foam performance due to dissolved salts, the selected foam suppressant should be evaluated for foaming ability, foam stability, and wettability when mixed with the site-specific dust suppression water.

(5) Limited coverage of foam spraying

Because of space constraints on nozzle placement, the current foam spray system can only cover the upper cutting area of the continuous miner’s cutting head. Close coordination between the foam dust suppression system and the dust extraction fans is therefore essential to achieve effective overall dust control.