Abstract

Between 1970 and 2023, China’s yearly anthropogenic CO2 emissions increased from 0.96 to 13.58 Pg. Yearly non-CO2 greenhouse gases (GHGs) in China increased from 1133.7 Tg CO2eq in 1970 to 3095.3 Tg CO2eq in 2023. In terms of weight of the global warming potential over a horizon of 100 years, China’s anthropogenic non-CO2 GHG emissions, approximately 56.8%, 13.5%, 10.1%, 10.4%, 5.2%, and 3.9% of which were from methane, nitrous oxide, hydrochlorofluorocarbons, hydrofluorocarbons, perfluorinated compounds, and chlorofluorocarbons, respectively, were equal to 23.3% of its anthropogenic CO2 emissions in 2023. Despite efforts for mitigation, China’s non-CO2 emissions are projected to keep growing in the foreseeable future due to unreported emissions, continuous industrialization, and global warming. This result shows that merely controlling anthropogenic CO2 emissions and achieving carbon neutrality are not enough; non-CO2 GHG emissions also need to be curbed.

1. Introduction

Due to anthropogenic climate change, the number of neonates facing climate extremes (e.g., heatwaves, floods, droughts, wildfires, typhoons, and food insecurity) has remarkably increased [1], showing the existence of intergenerational inequities in experiencing extreme weather events [2]. Equally important, climate change may cause the extinction of as many as a third of the Earth’s species, lowering biodiversity [3]. Sea levels have reached a record high since 1993 and surged at an accelerating speed, imperiling coastal economies [4]. The pH of the global mean ocean surface decreased from 8.11 in 1985 to less than 8.05 in 2023 [5].

Anthropogenic emissions of greenhouse gases (GHGs) are primarily responsible for global warming, and the global average surface temperature between 2011 and 2020 was 1.1 °C above that between 1850 and 1900 [6]. Emitting GHGs has led to an increase in radiative forcing (RF), which has caused a rise in temperature. Between 1990 and 2023, RF increased, which was caused by long-lived GHGs increasing by 51.5% from approximately 2.3 to 3.5 W·m−2, with carbon dioxide (CO2) accounting for 81% of this increase; from the preindustrial era to 2023, the global mean surface CO2 abundance increased from 278.3 to 420.0 ± 0.1 ppm [7].

Between the preindustrial era of 1750 and 2023, anthropogenic emissions of non-CO2 GHGs, including methane (CH4), nitrous oxide (N2O), and halocarbons, accounted for around 34% of the global mean temperature rise [7]. Halocarbons include chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs), hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs), hydrochlorofluorocarbons (HCFCs), fluorinated compounds (e.g., perfluorocarbons (PFCs), fluorinated ethers, perfluoropolyethers, and Halon-1201), and other types of GHGs (e.g., chloroform, carbon tetrachloride, methyl bromide); specifically, from the preindustrial era to 2023, the contributions of CO2, CH4, N2O, CFCs, HCFCs, and HFCs to the increase in global RF were 66%, 16%, 6%, 9%, 2%, and 1%, respectively [7]. CFCs and HCFCs are ozone-depleting substances (ODSs). Between 1960 and 2020, the increase in RF caused by ODS was around 0.3 W·m−2, greater than that caused by CH4 [8]. Stratospheric ozone depletion is a driving force of changes in weather, ocean surface temperature, sea currents, and the frequency of wildfires via altering atmospheric circulations [9].

To curtail climate change, the central Chinese government has crafted a detailed scheme to achieve peak carbon emissions by 2030 and realize carbon neutrality by 2060. China has planned to reduce anthropogenic CO2 emissions per unit of gross domestic product (GDP) by 65% from the 2005 level, enhance non-fossil energy production to more than 25% of total energy consumption, augment forest storage volume by 6 billion cubic meters compared to the 2005 level, and increase total installed capacity of wind and solar power to over 1.2 billion kilowatts by 2030.

In recent years, China has begun to focus on mitigating human-induced emissions of non-CO2 GHGs. China did not sign the global CH4 pledge in 2021 [10], but eleven pivotal departments of the central government, including the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the Ministry of Finance, and the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs, jointly issued China’s first plan to curtail anthropogenic CH4 emissions [11], which was announced by Chinese President Xi and former President Biden of the United States in November 2023 as a watershed event [12]. The climate topic has been raised to a head-of-state level.

In China’s CH4 emission control scheme announced on 7 November 2023, four main objectives and plans are given: (a) To strengthen overall planning and coordination, the Ministry of Ecology and Environment will set up a coordinated working mechanism to organize implementation, and enterprises are urged to consciously fulfill their social responsibilities. (b) To strengthen the fulfillment of responsibilities, key industries and enterprises should fully recognize the importance of CH4 emission control. (c) To strengthen publicity and training, local governments should popularize and publicize the benefits of CH4 emissions control. (d) To improve evaluation and supervision, the Ministry of Ecology and Environment will regularly monitor the progress of the implementation of CH4 reduction plans [11,12].

Moreover, China has implemented the Clean Development Mechanism (CDM) project under the framework of the 1997 Kyoto Protocol to abate CO2 and non-CO2 GHG emissions through saving energy usage. However, as the largest anthropogenic CH4 and N2O emitter around the world in the early 2020s [13,14], China has paid less attention to reducing non-CO2 GHGs than CO2 emissions. In this study, long-term non-CO2 GHG emissions in China are thoroughly reviewed.

This study aims to thoroughly recapitulate human-induced GHG emissions in China, depict their long-term emission trends, and analyze their sources.

2. Materials and Methods

We reviewed the most cited peer-reviewed research articles to holistically analyze China’s GHG emissions. These research articles were found through the most widely used databases around the world, including Web of Science and SCOPUS. We survey China’s official database for Patent Search and Analysis on the China National Intellectual Property Administration’s website (https://www.cnipa.gov.cn/). In the database of Web of Science, when we searched for “China anthropogenic CH4 emission”, a total of 554 documents were displayed; when we searched for “China anthropogenic N2O emission”, a total of 368 items were listed; when we searched for “China CFC emission”, “China HCFC emission”, and “China HFC emission”, a total of 151, 110, and 182 documents were shown, respectively. In the database of SCOPUS, when we searched for “China anthropogenic CH4 emission”, a total of 309 documents were displayed; when we searched for “China anthropogenic N2O emission”, a total of 173 items were listed; when we searched for “China CFC emission”, “China HCFC emission”, and “China HFC emission”, a total of 111, 70, and 89 documents were shown, respectively. By reviewing the literature, we have selected over 100 of the most representative and authoritative ones and summarized them in detail. We covered all emission data for anthropogenic CH4, N2O, and halocarbon sources in China over the last five decades.

Also, we consulted the latest files published by the Chinese government to list the latest emission reduction policies in China. According to the Ministry of Ecology and Environment, China fully, accurately, and comprehensively implements the new development concept; adheres to the people-centered approach; accelerates the formation of a new pattern of building a beautiful China guided by the goal of achieving harmonious coexistence between humans and nature; collaborates to promote carbon reduction, pollution reduction, green expansion, and growth; firmly implements the goal of carbon peak and carbon neutrality; regards green and low-carbon development as the fundamental solution to ecological and environmental problems; and makes new arrangements and requirements for addressing climate change. A systematic deployment has been made around building a green, low-carbon, and high-quality development spatial pattern; accelerating green transformation in key areas, implementing comprehensive conservation strategies; promoting green transformation of consumption patterns; and leveraging the support of technological innovation. Scientists propose establishing and improving policies, systems, and management mechanisms for local carbon assessment, industry carbon control, enterprise carbon management, project carbon evaluation, product carbon footprint, etc., and effectively connecting them with the national carbon emission trading market to build a comprehensive carbon emission dual control system. China will implement a carbon emission dual control system with intensity control as the main focus and total amount control as a supplement after reaching peak carbon emissions. By 2035, China’s net GHG emissions across the entire economy spectrum will decrease by 7% to 10% compared to the peak levels; the proportion of non-fossil energy consumption in total energy consumption will be over 30%; the total installed capacity of wind and solar power combined will reach 3.6 billion kilowatts; the forest storage volume will reach more than 24 billion cubic meters; the national carbon emission trading market will cover all major high emission industries. Thus, a climate-adaptive society will be built by 2035.

3. Results

3.1. Anthropogenic CH4 Emissions

From the preindustrial era of 1750 to 2023, the global average atmospheric mole fraction of CH4 had increased from around 729.2 parts per billion (ppb) to 1934 ± 2 ppb as 153 atmospheric monitoring stations around the world showed, reaching a level unparalleled in the last 800 thousand years [7]. Estimates of global CH4 emissions include the Emissions Database for Global Atmospheric Research (EDGAR) [15], the Greenhouse Gas and Air Pollutant Interactions and Synergies (GAINS) [16], the Global Carbon Project (GCP) [17,18,19], the United States Environmental Protection Agency (USEPA), Netherland’s Environmental Assessment Agency (PBL), and the Community Emissions Data System (CEDS) for the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO). Since the lifetime of CH4 is 9.1 ± 0.9 years in 2010 [20], which was much shorter than that of other GHGs, a reduction in CH4 emissions can effectively curb global warming in the short term.

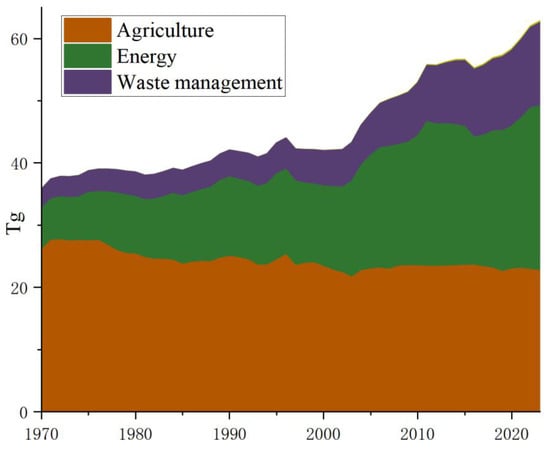

The global warming potential values for the time horizon of 100 years (GWP100) can be used to assess the impact of different kinds of GHG emissions on global warming. According to the GCP (https://www.globalcarbonproject.org/), the results of top-down atmospheric inversions showed that between 2008 and 2017, the annual average global CH4 emissions were 576 Teragram (Tg) (16.1 Picogram (Pg) CO2eq), approximately 62% and 38% of which were attributed to anthropogenic and natural sources, respectively [21]. Agricultural activities, fossil fuel utilization, and waste management accounted for approximately 40%, 35%, and 20% of total global anthropogenic CH4 emissions, respectively [22]. According to EDGARv8.0 (https://edgar.jrc.ec.europa.eu/, accessed on 5 September 2025) [23], between 1970 and 2023, yearly anthropogenic CH4 emissions around the world increased from 233.1 to 349.6 Tg (6.5 to 9.8 Pg CO2eq); China’s annual anthropogenic CH4 emissions increased from 35.8 to 62.8 Tg (1.0 to 1.8 Pg CO2eq), accounting for 15.4% and 18.0% of global emissions in 1970 and 2023, respectively. China’s yearly natural CH4 emissions were estimated to range from 4.0 [24] to 8.0 Tg [25]. Figure 1 illustrates the annual anthropogenic CH4 emissions in China between 1970 and 2023 [14,15,23]. Emission reduction approaches of anthropogenic CH4 emissions have been detailed [26,27,28,29]. Table 1 shows the estimates of China’s anthropogenic CH4 emissions [11,21,23,24,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45].

Figure 1.

Annual anthropogenic CH4 emissions in China between 1970 and 2023 [14,15,23].

Table 1.

Estimates of annual anthropogenic CH4 emissions in China.

3.2. Anthropogenic N2O Emissions

From the preindustrial era of 1750 to 2023, the global average atmospheric mole fraction of N2O had increased from about 270.1 ppb to 336.9 ± 0.1 ppb, as indicated by 112 atmospheric monitoring stations around the world [7]. N2O has been the most prominent ODS throughout this century [46,47]. N2O and CH4 have complex coupling interrelations, which have indirect impacts on climate change and stratospheric ozone. In the atmosphere, an increase in 1 mole fraction of N2O would result in a reduction of 0.36 mole fraction of CH4 through depleting stratospheric ozone, changing solar ultraviolet radiation, altering stratosphere-to-troposphere O3 flux, and elevating tropospheric hydroxyl radical concentrations [48]. In addition, due to the emissions of GHGs, mainly including CO2, CH4, and N2O, global mid and upper stratosphere has cooled at a rate of −0.6 K per decade since the late 1990s [49], leading to an increase in the ratio of N atoms to nitric oxide (NO) and thus a reduction in stratospheric ozone destruction [50].

Top-down atmospheric inversions showed that, in 2020, annual global natural and anthropogenic N2O emissions were 26.7 (26.1–27.3) Tg (7.1 Pg CO2eq) [51]; between 2007 and 2016, yearly average global N2O emissions were estimated to be 26.6 (25.0–27.8) Tg (7.0 Pg CO2eq), approximately 43% and 57% of which were ascribed to anthropogenic and natural sources, respectively [52]; between 2011 and 2020, annually average global N2O emissions were estimated to be 27.0 (26.2–27.8) Tg (7.2 Pg CO2eq), approximately 70% and 30% of which were from the land and ocean, respectively [53].

A bottom-up inventory showed that, between 1970 and 2023, annual global anthropogenic N2O emissions increased by three-fourths from 5.4 to 9.4 Tg (1.4 to 2.5 Pg CO2eq); China’s anthropogenic N2O emissions increased by more than two times from 496.7 to 1581.2 Gigagram (Gg) (131.6 to 419.0 Tg CO2eq) [23], accounting for 9.1% and 16.8% of global emissions in 1970 and 2023, respectively. In 2008, China’s annual anthropogenic N2O emissions were 2150 (1174 to 2787) Gg (596.8 Tg CO2eq), approximately 64%, 17%, 12%, 5%, 2.8%, and 0.2% of which were attributable to agriculture, energy, indirect sources, wastes, the chemical industry, and wildfires [54]. From 1978 to 2015, China’s annual anthropogenic N2O emissions increased by 140% from 1.6 to 3.8 Tg [55]. Figure 2 illustrates the annual anthropogenic N2O emissions in China between 1970 and 2023 [23]. The emission reduction avenues of anthropogenic N2O emissions have been elaborated [28,56].

Figure 2.

Annual anthropogenic N2O emissions in China between 1970 and 2023 [23].

3.3. Halocarbons

The Chinese government terminated the production of all CFCs in 2007, which was completed three years ahead of the 1987 Montreal Protocol’s 2010 phase-out deadline for developing countries. The Montreal Protocol focused on CFC emissions, but it did not cover CFCs from obsolete cooling units. At present, only a small amount of CFCs for medical purposes is allowed to be used. China has implemented a quota license system for the import and export of CFCs, and import or export is not allowed without permission [57]. Estimates of China’s CFC-11 and CFC-12 emissions under strict governmental regulations between 1978 and 2037 [58], indicating that peak CFC-11 emissions occurred in 2004, reaching 17.5 Gg; the peak CFC-12 emissions occurred in 1995, reaching 33.7 Gg; in 2010, CFC-11 and CFC-12 emissions were supposed to be slashed to 14.4 Gg and 2.7 Gg, respectively.

High-precision measurements of atmospheric halogenated compounds can be used to assess emissions using inversion models [59,60]. The rate of decline of atmospheric CFC-11 abundance decreased by 50% during 2012–2016 compared to that during 2002–2012, showing an annual increase of 13 ± 5 Gg with respect to CFC-11 emissions globally [61]. Rogue CFC-11 emissions were found in the Chinese provinces of Shandong and Hebei, indicating new production and use; yearly average CFC-11 emissions from eastern mainland China were 7.0 ± 3.0 Gg during 2014–2017, higher than during 2008–2012, accounting for approximately half of the global increase in CFC-11 emissions [62]. Southwestern and central China and the Pearl River Delta metropolitan region contributed CFC-11 emissions in 2017 [63].

China has crafted a plan to establish a national monitoring network [64] to track rogue CFC-11 emissions and has seized illicit CFC-11 production since 2012 [65]. In carrying this out, an accelerated decline in the global average atmospheric CFC-11 abundance during 2019–2020 was achieved; in 2019, annual global CFC-11 emissions were estimated to be 52 ± 10 Gg, which decreased by 18 ± 6 Gg compared to previous years [66]. The annual mean CFC-11 emissions in eastern China were 19 ± 5 Gg during 2014–2018 [67]; the yearly average CFC-11 emissions in eastern China were estimated to be 7.2 ± 1.5 Gg during 2008–2012 and 5.0 ± 1.0 Gg in 2019 [68], showing that China has successfully curtailed CFC-11 production [69]. The annual mean CFC-11 emissions from southeastern China were estimated to range from 1.23 ± 0.25 to 1.58 ± 0.21 Gg using top-down inversions and 1.50 Gg using the bottom-up inventory during 2022–2023, which returned to the levels prior to 2010 [70].

Atmospheric observations at the top of Mount Tai in Shandong indicated that there were several types of unreported CFC emissions, including not only CFC-11 but also CFC-12, CFC-113, and CFC-114 in China between 2017 and 2018 [71]. Annually average CFC-12 emissions in China from 2010 to 2020 were estimated to be 11.0 ± 0.6 Gg [72]. In 2021, CFC-113 emissions in eastern China were estimated to be 0.88 ± 0.19 Gg [73]. Globally, yearly combined emissions of five CFCs (CFC-13, CFC-112a, CFC-113a, CFC-114a, and CFC-115) were equivalent to 4.2 ± 0.4 Gg CFC-11eq and 47 ± 5 Tg CO2eq in 2020 [74], and emissions of CFC-113, CFC-114, and CFC-115 have not been reduced as expected [75]. However, China’s CFC emissions other than CFC-11 and CFC-12 have not been fully investigated. The interspecies relevance of CFC-11 with CHCl3, CCl4, HCFC-141b, HCFC-142b, CH2Cl2, and HCFC-22 implied the co-location of the emissions [67], showing that CFC-11 may be used as an indicator for estimating the emissions of other types of halocarbons. For more accurate estimations of rogue productions, ground-level observation is of importance [76]. Developing low-cost alternatives is a feasible way to curb rogue productions [77]. Because CFC emissions have not only contributed to stratospheric ozone depletion but also led to global warming, their emission reductions have triggered widespread concerns for decades [78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86].

China’s annual production and usage of HCFCs were estimated to be 29.1 Gg and 18.1 Gg CFC-11eq, respectively, in the early 2020s; the Chinese government plans to cut down 97.5% of baseline production and reserve only 2.5% for meeting the needs of refrigeration and air conditioning maintenance by 2030 [57]. During 2009–2019, among all released ODSs in China, HCFC emissions accounted for 58.6% in terms of CO2eq [87]. China’s HCFC banks in foam products accounted for more than 91% of the national total in 2019 [88]. Like CFCs, unexpected emissions of HCFCs, including HCFC-31, HCFC-132b, and HCFC-133a, which have no known end uses, were detected, and East Asian countries, including China, were identified as the dominant source region for HCFC-132b and HCFC-133a [89].

Annual global HCHC-22 emissions decreased from 17.3 ± 0.8 Gg in 2019 to 14.0 ± 0.9 Gg in 2023; China has been the world’s largest HCFC-22 producer [90], accounting for around 80% of the national total HCFC production [87]. Between 1990 and 2014, China’s annual HCFC-22 emissions increased from 0.2 to 127.2 Gg [91]. Between 2018 and 2021, China’s annual average HCFC-22 emissions were estimated to be 160 ± 33 Gg [92]. The production of HCFC-141b will be completely prohibited by the Chinese government by January 2030 [57]. However, used as a substitute for CFC-11, China’s yearly HCFC-141b emissions increased from 0.8 Gg in 2000 to 15.8 Gg in 2013 [93]. Annual HCFC-141b emissions in eastern China increased from 3.7 Gg in 2008 to 6.8 Gg in 2020 [94]. Yearly HCFC-141b emissions in eastern China increased from 0.4 Gg in 2000 to 7.1 Gg in 2019, with a bank of 253.6 Gg in polyurethane foam products [95]. China’s HCFC-141b emissions were estimated to be 19.4 (17.3–21.6) Gg per year on average from 2018 to 2020 and 15.5 Gg in 2017 [96]. Between 2018 and 2021, China’s annual average HCFC-142b emissions were estimated to be 7.9 ± 1.7 Gg [92]. Except for HCFC-22, HCFC-141b, and HCFC-142b, emissions of other types of HCFCs in China have not been fully investigated. Moreover, using the default emission factors for fluorochemical production recommended by IPCC 2006 to estimate the emissions of HCFCs and HFCs from fluorochemical plants in China may lead to underestimation [97]. Atmospheric concentrations of HCFC-22 and HCFC-142b in China were reported by a previous study [98], indicating China’s high emissions.

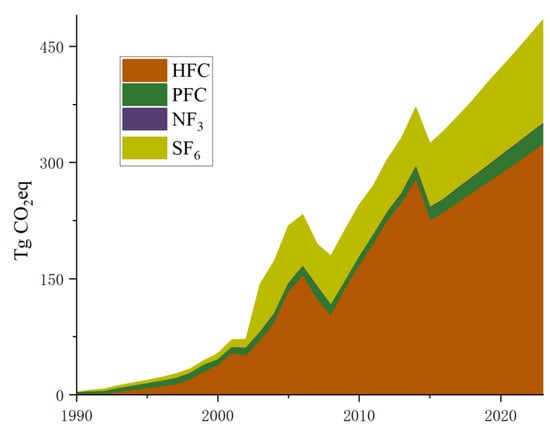

With the gradual phase-out of CFCs and HCFCs, China’s HFC production has tremendously scaled up [97]. HFC-23 is a byproduct of HCFC-22 synthesis [90]. An increase in global HFC-23 emissions was found despite near-total expected reductions [99,100]. According to EDGARv8.0 [23], the annual combined average HFC emissions, including HFC-23, HFC-32, HFC-125, HFC-134a, and HFC-227ea, in China increased more than 64 thousand times from 5.0 Gg CO2eq in 1991 to 322.22 Tg CO2eq in 2023. China’s annual production and usage of HFCs were estimated to be 1853 Tg and 905 Tg CO2eq, respectively, in the early 2020s; the Chinese government plans to cut down 10% of baseline HFC production by 2029 [57]. During 2011–2017, HFC-32, HFC-125, HFC-134a, HFC-227ea, and HFC-245fa emissions increased rapidly, and HFC-143a, HFC-152a, HFC-236fa, and HFC-365mfc emissions remained stable [101]. For 2010–2012, China’s yearly average emissions of HFC-32, HFC-125, HFC-134a, HFC-143a, and HFC-152a were 7.03 (4.92–9.24), 5.72 (4.02–7.73), 12.25 (4.87–20.90), 2.15 (1.33–3.15), and 5.33 (1.64–9.42) Gg, respectively [102]. The economically powerful Chinese provinces such as Jiangsu, Zhejiang, and Guangdong were the major contributors of HFC (HFC-32, HFC-125, HFC-134a, and HFC-143a) emissions [103]. Between 2011 and 2020, China’s yearly HFC-134a emissions increased from 19.5 ± 2.5 Gg to 33.1 ± 7.5 Gg [104]. Over the period of 2018–2020, China’s annual average HFC-152a emissions were estimated to be 9.9 ± 1.7 Gg [105]. Figure 3 shows HFC emissions in China from 1990 to 2023 [14]. Even though HFC emissions have not been regulated yet in China, emission reduction pathways have proven to be feasible [106].

Figure 3.

HFC emissions in China from 1990 to 2023 [14].

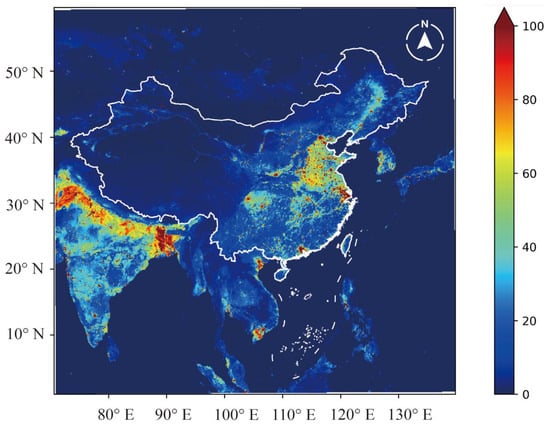

According to EDGARv8.0 [23], annual average perfluorinated compound emissions, including PFCs, sulfur hexafluoride (SF6), and nitrogen trifluoride (NF3), in China increased more than 64 thousand times from 5.1 Tg CO2eq in 1990 to 168.8 Tg CO2eq in 2023. Several types of F-gases emissions, including PFC (CF4, C2F6, C3F8, and c-C4F8), NF3, and SF6 combined, in China increased from 5.5 Tg CO2eq in 1990 to 221 Tg CO2eq in 2019 [107]. China’s yearly PFC-318 (c-C4F8) emissions, a byproduct of the pyrolysis of HCFC-22, increased from 0.65 Gg in 2011 to 1.12 Gg [108]. Yearly NF3 emissions in China increased from 0.93 ± 0.15 Gg in 2015 to 1.53 ± 0.20 Gg in 2021 [109]. Figure 4 shows China’s annual emissions of HFC and perfluorinated compounds from 1990 to 2023 [14]. Figure 5 indicates the distribution of HFC emissions in China in 2023 [14]. Abating perfluorinated compounds in China has proven to be viable [110].

Figure 4.

Emissions of perfluorinated compounds in China between 1990 and 2023 [14].

Figure 5.

Emissions of HFC and perfluorinated compounds from 1990 to 2023 in China in terms of GWP100-weight [14].

HFO-1336mzz(Z) has been produced in China since 2014 [111]. From 2011 to 2019, yearly CH2Cl2 emissions in China increased from 231 (213–245) to 628 (599–658) Gg [112]. During 2010–2015, China’s yearly chloroform emissions increased by 49 Gg [113].

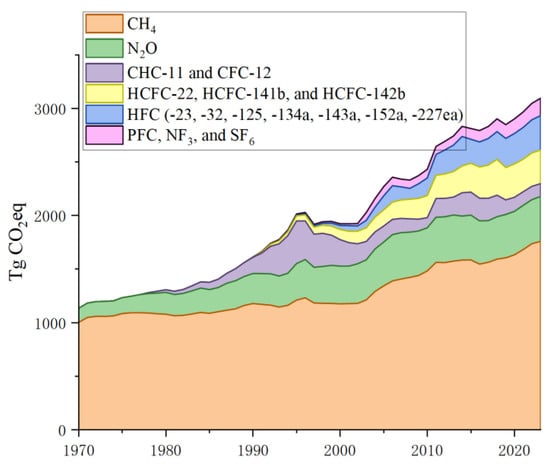

3.4. Emissions of Overall Non-CO2 GHGs

According to EDGARv8.0, between 1970 and 2023, China’s yearly non-CO2 GHG emissions increased from 1.5 to 2.7 Pg CO2eq; in terms of GWP100-weight, the proportion of non-CO2 GHG emissions from China compared to global total emissions increased from 14.6% to 19.3% [23]. According to previous studies [14,15,23,58,62,67,72,91,92,96,104,107], evidently, China’s total anthropogenic non-CO2 GHG emissions increased from 1.1 Pg CO2eq in 1970 to 1.6 Pg CO2eq in 1990 to 3.1 Pg CO2eq in 2023, as shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Emissions of overall anthropogenic non-CO2 GHGs in China [14,15,23,58,62,67,72,91,92,96,104,107].

3.5. Anthropogenic CO2 Emissions

China has become the largest anthropogenic CO2 emitter around the world since 2006, and it exceeded the European Union (EU) with respect to per capita anthropogenic CO2 emission in 2014 [114]. In 2023, global total net CO2 emissions were estimated to be 40.6 ± 3.2 Pg; global fossil CO2 emissions were estimated to be 37.8 ± 1.8 Pg, approximately 31% of which were from fossil fuel utilization in China [115]. As Figure 7 indicates, from 1970 to 2023, China’s yearly anthropogenic CO2 emissions increased from 0.96 to 13.58 Pg [23]. China’s overall GHG emissions by sector from 1990 to 2023 [23]. The Multi-Resolution Emission Inventory Model for Climate and Air Pollution Research (MEIC; http://meicmodel.org.cn) provides detailed anthropogenic CO2 emissions in China [116].

Figure 7.

Anthropogenic CO2 emissions in China [23].

4. Discussion

4.1. Improving Estimation Accuracy

To limit global warming below 1.5 °C, more than 90% of anthropogenic GHG emissions need to be reduced by 2040 compared to 2015 levels [117]. In January 2024, as a follow-up to China’s first CH4 control plan, the Ministry of Ecology and Environment of China crafted and published an official handbook called “Technical guidelines for compiling integrated emission inventories of atmospheric pollutants and GHGs”. This 123-page guidebook comprises the most detailed report introducing a bottom-up approach, and the methods for calculating anthropogenic CH4 and N2O emissions in each Chinese province are stated [118], showing China’s determination to construct a clean, beautiful, and sustainable world.

This guidebook, to our knowledge, introduces a more comprehensive estimate method for assessing non-CO2 emissions in China than EDGARv8.0 does. However, according to newly discovered climate science, the calculation method for China’s assessment of anthropogenic CH4 and N2O emissions in this guidebook can be improved with respect to certain aspects. First, the guidebook may underestimate soil CH4 and N2O emissions in China. In the guidebook, anthropogenic CH4 and N2O emissions are estimated by multiplying activity-level data with emission factors (EFs), which were based on field observations in 2005, nearly two decades ago. Global warming has regulated soil CH4 and N2O emissions. Climate change has led to the thickening of active layers of methanogens [119], changes in vertical substrate availability [120], and an increase in large-scale inundation that resulted in the enhanced activity of methanogens [121], causing increased global soil CH4 emissions. However, other reports showed that, due to soil drying and enrichment in nutrient supply, global warming has also increased microbial CH4 oxidation by methanotrophs, leading to an increase in CH4 sinks [122,123]. As temperature rises, soil N2O emissions increase [124]; soil N2O emissions also increase as moisture increases when monthly precipitation is less than 79 mm [125]. Some EFs used in the guidebook may be out of date and cannot reflect real emissions in a warming climate. Second, in the guidebook, the relationship between soil N2O emissions and active nitrogen input is assumed to be strictly linear. However, an increasing number of studies have reported the nonlinearity of response between these two [126]. Due to the overuse of chemical fertilizers in Chinese smallholders [127], the guideline may underestimate agricultural N2O emissions. Third, the point sources from energy utilization in the guidebook are omitted. In recent years, super-emitters of CH4 have been found in North America by geostationary satellites [128,129]. However, extreme and transient CH4 emissions from energy utilization were not included in the guideline. Moreover, CH4 emissions from small-scale wildfires were discovered [130,131], which were not included as well. Moreover, the concepts of the social cost of CH4 and N2O emissions (SC-CH4 and SC-N2O) [132,133] are not fully understood and accepted by local technocrats. In a changing climate, personal behavior may lead to loss of social welfare [134]. The benefits of clean development mechanism projects in China were assessed [135].

To fulfill the four goals listed above, formulating a more comprehensive and up-to-date inventory based on newly discovered climate sciences to make the estimation of human-induced sources more accurate is imperative. Process-based models, atmospheric inversions, and data-driven models are needed to validate the accuracy of bottom-up approaches. Also, to fill the gap of the mismatch between nation-level emission reduction plans and emission reduction technologies, thoroughly exploring viable emission reduction technologies presently mastered by each province and the local costs required to implement these technologies is necessary. Finally, climate scientists should guide enterprises, colleges, universities, and scientific research institutions to comprehend the concept of SC-CH4 and SC-N2O. In doing so, policymakers can more persuasively price and manage anthropogenic emissions, and locals would have more forward-looking motivation to follow emission reduction plans.

4.2. Limitations and Recommendations

Out of around 1500 climate policies carried out from 1998 to 2022 in 41 countries across six continents, 63 have been identified as successful policies with an overall reduction of around 1.2 Pg CO2 [136]. Reportedly, to achieve the ambitious goals of the 2016 Paris Agreement, the economic costs may be as much as 3 to 6% of China’s gross domestic product by 2050 [137]. Equally important, different versions of international climate agreements tend to ignore the mismatch between the world’s intention and the ability to reduce non-CO2 GHG emissions. Technologies for mitigating CH4 and N2O have been reported [22,132]. However, for developing countries, both technical capacity and reserve for reducing CH4 and N2O emissions are inadequate [138]; advanced N2O abatement technology [139] has not been used in China yet. The economic cost of reducing one Pg of CO2eq was estimated to be around USD 2.4 trillion [140]. To better implement abatement schemes, an investigation into the economic costs and monetized social benefits of emission reduction is imperative; an authoritative cost–benefit analysis must be formulated and widely accepted. At last, shared socioeconomic pathways [141,142,143] can be used to predict future non-CO2 GHG emissions in China. One limitation is that China does not possess many reduction options. The largest challenge in abating CH4 and N2O emissions is that China has substantially fewer technical options than developed countries. Reportedly, the number of GHG emission reduction inventions was associated with the slowdown of GHG emission growth [138]. To develop feasible reduction schemes, the first two questions are what CH4 and N2O emission reduction technologies China currently possesses and whether they have been applied for formulating realistic emission reduction policies. We find that, presently, China only holds around 100 patents related to CH4 and N2O emission reduction technologies (see Table 2 and Table 3), substantially fewer than developed countries [3]. Approximately seven-tenths of high-quality CH4 emission reduction inventions are possessed by developed countries; however, populous developing countries such as China are playing an increasingly important role in reducing CH4 waste emissions, and the international diffusion rate of these technologies is slow.

Table 2.

The patents related to CH4 emission reductions currently owned by China.

Table 3.

The patents related to N2O emission reductions currently owned by China.

Another limitation is that atmospheric inversions cannot reflect emission hotspots well. Figure 8 and Figure 9 show China’s anthropogenic CH4 and N2O emissions in 2023, respectively, at high resolutions [14,23]. However, the resolution of atmospheric inversions is much lower. The lack of observational data is the main obstacle to accurately assessing China’s non-CO2 GHG emissions.

Figure 8.

The distribution of anthropogenic CH4 emissions in China in 2023 [14].

Figure 9.

The distribution of anthropogenic N2O emissions in China in 2023 [23].

Due to the relatively small number of patented technologies in China [138,144], Chinese scientists develop more technologies with independent intellectual property rights. Equally important, it is imperative to establish more ground-based GHG observation stations to more accurately assess their emissions via atmospheric inversion models.

5. Conclusions

Anthropogenic GHG emissions, including not only CO2 but also potent non-CO2 GHGs, should be cut down to prevent global warming from pushing the ecosystem towards the edge of the precipice. China’s annual non-CO2 GHG emissions increased by more than 1.7 times from 1970 to 2023. With the enforcement of China’s carbon neutrality scheme, non-CO2 GHGs are playing an increasingly critical role in contributing to climate change. However, most non-CO2 GHGs are not under control. We suggest that scientists pay more attention to the management of non-CO2 GHG emissions in China. An across-the-board assessment on future emission trends is also imperative. China has taken a series of targeted measures to control the anthropogenic emissions of non-CO2 GHGs and has made clear progress. In the Action Plan for Methane Emission Control, released by the end of 2023, China has planned to improve the utilization rate of coal mine gas, promote the resource utilization of livestock and poultry manure, and scientifically control CH4 emissions from rice fields. In the Action Plan for Controlling Nitrous Oxide Emissions in the Industrial Sector, released in August 2025, China has planned to continuously decrease industrial N2O emissions per unit of product. China has also crafted detailed policies to reduce the emissions of CFCs, HCFCs, and HFCs. The national voluntary GHG emission reduction trading market was launched, indicating that enterprises can obtain economic gains by developing emission reduction projects and trading verified emission reductions in the market. As of the end of October 2025, the total trading volume of the market has reached 3.25 million tons in CO2eq. China’s control over non-CO2 GHG emissions will continue to deepen and has been incorporated into the national top-level design. For the first time, in China’s announced 2035 Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs), non-CO2 GHGs were explicitly included in the overall economic GHG emission reduction target, which means that future emission reduction schemes will be a systematic project covering all types of GHGs. In the future, China will continuously expand the scope of the voluntary emission reduction market to support and construct a methodological system with high standards in order to encourage more social forces to participate in all kinds of GHG emission reductions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.F.; methodology, R.F. and K.F.; software, S.Y. and Z.Q.; validation, R.F., S.Y. and B.Z.; formal analysis, R.F.; investigation, R.F.; resources, B.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, R.F.; writing—review and editing, R.F.; visualization, R.F.; supervision, B.Z.; project administration, R.F.; funding acquisition, R.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by the Zhejiang Provincial Natural Science Foundation (No. LQN25D050006) and Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities of China (No. 226-2024-00040).

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Grant, L.; Vanderkelen, I.; Gudmundsson, L.; Fischer, E.; Seneviratne, S.I.; Thiery, W. Global emergence of unprecedented lifetime exposure to climate extremes. Nature 2025, 641, 374–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiery, W.; Lange, S.; Rogelj, J.; Schleussner, C.-F.; Gudmundsson, L.; Seneviratne, S.I.; Andrijevic, M.; Frieler, K.; Emanuel, K.; Geiger, T.; et al. Intergenerational inequities in exposure to climate extremes. Science 2021, 374, 158–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Urban, M. Climate change extinctions. Science 2024, 386, 1123–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- UN. United Nations Climate Action. Surging Seas in a Warming World. 2024. Available online: https://www.un.org/en/climatechange/reports/sea-level-rise (accessed on 1 June 2025).

- WMO-No. 1368; State of the Global Climate 2024. WMO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2025. Available online: https://library.wmo.int/records/item/69455-state-of-the-global-climate-2024 (accessed on 3 June 2025).

- IPCC. Climate Change 2023: Synthesis Report. In Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Core Writing Team, Lee, H., Romero, J., Eds.; IPCC: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023; p. 184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WMO. Greenhouse Gas Bulletin No. 20. The State of Greenhouse Gases in the Atmosphere Based on Global Observations through 2023. In WMO Greenhouse Gas Bulletin; WMO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2024; Available online: https://library.wmo.int/records/item/69057-no-20-28-october-2024 (accessed on 3 June 2025).

- Polvani, L.M.; Previdi, M.; England, M.R.; Chiodo, G.; Smith, K.L. Substantial twentieth-century Arctic warming caused by ozone-depleting substances. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2020, 10, 130–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes, P.W.; Williamson, C.E.; Lucas, R.M.; Robinson, S.A.; Madronich, S.; Paul, N.D.; Bornman, J.F.; Bais, A.F.; Sulzberger, B.; Wilson, S.R.; et al. Ozone depletion, ultraviolet radiation, climate change and prospects for a sustainable future. Nat. Sustain. 2019, 2, 569–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNEP. United Nations Environment Programme/Climate and Clean Air. Coalition. In Global Methane Assessment: 2030 Baseline Report; United Nations Environment Programme: Nairobi, Kenya, 2022; Available online: https://www.unep.org/resources/report/global-methane-assessment-2030-baseline-report. (accessed on 1 June 2025)ISBN 978-92-807-3978-7.

- You, H. China’s plan to control methane emissions. Science 2024, 383, 377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nisbet, E. New hope for methane reduction. Science 2023, 382, 1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, R.; Li, Z.; Qi, Z. China’s anthropogenic N2O emissions with analysis of economic costs and social benefits from reductions in 2022. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 353, 120234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crippa, M.; Guizzardi, D.; Pagani, F.; Schiavina, M.; Melchiorri, M.; Pisoni, E.; Graziosi, F.; Muntean, M.; Maes, J.; Dijkstra, L.; et al. Insights into the spatial distribution of global, national, and subnational greenhouse gas emissions in the Emissions Database for Global Atmospheric Research (EDGAR v8.0). Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2024, 16, 2811–2830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crippa, M.; Solazzo, E.; Huang, G.; Guizzardi, D.; Koffi, E.; Muntean, M.; Schieberle, C.; Friedrich, R.; Janssens-Maenhout, G. High resolution temporal profiles in the Emissions Database for Global Atmospheric Research. Sci. Data 2020, 7, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Höglund-Isaksson, L.; Gómez-Sanabria, A.; Klimont, Z.; Rafaj, P.; Schöpp, W. Technical potentials and costs for reducing global anthropogenic methane emissions in the 2050 timeframe–results from the GAINS model. Environ. Res. Commun. 2020, 2, 025004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, R.B.; Saunois, M.; Martinez, A.; Canadell, J.G.; Yu, X.; Li, M.; Poulter, B.; Raymond, P.A.; Regnier, P.; Ciais, P.; et al. Human activities now fuel two-thirds of global methane emissions. Environ. Res. Lett. 2024, 19, 101002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saunois, M.; Martinez, A.; Poulter, B.; Zhang, Z.; Raymond, P.A.; Regnier, P.; Canadell, J.G.; Jackson, R.B.; Patra, P.K.; Bousquet, P.; et al. Global Methane Budget 2000–2020. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2025, 17, 1873–1958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirschke, S.; Bousquet, P.; Ciais, P.; Saunois, M.; Canadell, J.G.; Dlugokencky, E.J.; Bergamaschi, P.; Bergmann, D.; Blake, D.R.; Bruhwiler, L.; et al. Three decades of global methane sources and sinks. Nat. Geosci. 2013, 6, 813–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prather, M.J.; Holmes, C.D.; Hsu, J. Reactive greenhouse gas scenarios: Systematic exploration of uncertainties and the role of atmospheric chemistry. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2012, 39, L09803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saunois, M.; Stavert, A.R.; Poulter, B.; Bousquet, P.; Canadell, J.G.; Jackson, R.B.; Raymond, P.A.; Dlugokencky, E.J.; Houweling, S.; Patra, P.K.; et al. The Global Methane Budget 2000–2017. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2020, 12, 1561–1623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNEP. United Nations Environment Programme and Climate and Clean Air. Coalition. In Global Methane Assessment: Benefits and Costs of Mitigating Methane Emissions; United Nations Environment Programme: Nairobi, Kenya, 2021; Available online: https://www.unep.org/resources/report/global-methane-assessment-benefits-and-costs-mitigating-methane-emissions. (accessed on 2 June 2025)ISBN 978-92-807-3854-4.

- Crippa, M.; Guizzardi, D.; Pagani, F.; Banja, M.; Muntean, M.; Schaaf, E.; Monforti-Ferrario, F.; Becker, W.E.; Quadrelli, R.; Risquez Martin, A.; et al. GHG Emissions of all World Countries; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, Belgium, 2024; Available online: https://publications.jrc.ec.europa.eu/repository/handle/JRC138862 (accessed on 5 September 2025).

- Zhang, Y.; Fang, S.; Chen, J.; Lin, Y.; Chen, Y.; Liang, R.; Jiang, K.; Parker, R.J.; Boesch, H.; Steinbacher, M.; et al. Observed changes in China’s methane emissions linked to policy drivers. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2022, 119, e2202742119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Shi, Y. High Spatial and Temporal Resolution Methane Emissions Inventory from Terrestrial Ecosystems in China, 2010–2020. Atmosphere 2022, 13, 1966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubin, E.S.; Cooper, R.N.; Frosch, R.A.; Lee, T.H.; Marland, G.; Rosenfeld, A.H.; Stine, D.D. Realistic Mitigation Options for Global Warming. Science 1992, 257, 148–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, Z.; Feng, R. Global natural and anthropogenic methane emissions with approaches, potentials, economic costs, and social benefits of reductions: Review and outlook. J. Environ. Manag. 2025, 373, 123568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, H.; Zhu, X.; Huang, S.; Linquist, B.; Kuzyakov, Y.; Wassmann, R.; Minamikawa, K.; Martinez-Eixarch, M.; Yan, X.; Zhou, F.; et al. Greenhouse gas emissions and mitigation in rice agriculture. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2023, 4, 716–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, S.J.; Lewis, N.S.; Shaner, M.; Aggarwal, S.; Arent, D.; Azevedo, I.L.; Benson, S.M.; Bradley, T.; Brouwer, J.; Chiang, Y.M.; et al. Net-zero emissions energy systems. Science 2018, 360, eaas9793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, S.; Piao, S.; Bousquet, P.; Ciais, P.; Li, B.; Lin, X.; Tao, S.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, F. Inventory of anthropogenic methane emissions in mainland China from 1980 to 2010. Atmospheric Meas. Tech. 2016, 16, 14545–14562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zheng, B. Tracking regional CH4 emissions through collocated air pollution measurement: A pilot application and robustness analysis in China. Npj Clim. Atmos. Sci. 2025, 8, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Jacob, D.J.; Lu, X.; Maasakkers, J.D.; Scarpelli, T.R.; Sheng, J.X.; Shen, L.; Qu, Z.; Sulprizio, M.P.; Chang, J.; et al. Attribution of the accelerating increase in atmospheric methane during 2010–2018 by inverse analysis of GOSAT observations. Atmospheric Meas. Tech. 2021, 21, 3643–3666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stavert, A.R.; Saunois, M.; Canadell, J.G.; Poulter, B.; Jackson, R.B.; Regnier, P.; Lauerwald, R.; Raymond, P.A.; Allen, G.H.; Patra, P.K.; et al. Regional trends and drivers of the global methane budget. Glob. Chang. Biol. 2022, 28, 182–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Maksyutov, S.S.; Janardanan, R.; Tsuruta, A.; Ito, A.; Morino, I.; Yoshida, Y.; Tohjima, Y.; Kaiser, J.W.; Janssens-Maenhout, G.; et al. Interannual variability on methane emissions in monsoon Asia derived from GOSAT and surface observations. Environ. Res. Lett. 2021, 16, 024040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Maksyutov, S.; Tsuruta, A.; Janardanan, R.; Ito, A.; Sasakawa, M.; Machida, T.; Morino, I.; Yoshida, Y.; Kaiser, J.W.; et al. Methane Emission Estimates by the Global High-Resolution Inverse Model Using National Inventories. Remote. Sens. 2019, 11, 2489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, J.; Tunnicliffe, R.; Ganesan, A.L.; Maasakkers, J.D.; Shen, L.; Prinn, R.G.; Song, S.; Zhang, Y.; Scarpelli, T.; Bloom, A.A.; et al. Sustained methane emissions from China after 2012 despite declining coal production and rice-cultivated area. Environ. Res. Lett. 2021, 16, 104018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, Z.; Jacob, D.J.; Shen, L.; Lu, X.; Zhang, Y.; Scarpelli, T.R.; Nesser, H.; Sulprizio, M.P.; Maasakkers, J.D.; Bloom, A.A.; et al. Global distribution of methane emissions: A comparative inverse analysis of observations from the TROPOMI and GOSAT satellite instruments. Atmospheric Meas. Tech. 2021, 21, 14159–14175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X.; Jacob, D.J.; Zhang, Y.; Maasakkers, J.D.; Sulprizio, M.P.; Shen, L.; Qu, Z.; Scarpelli, T.R.; Nesser, H.; Yantosca, R.M.; et al. Global methane budget and trend, 2010–2017: Complementarity of inverse analyses using in situ (GLOBALVIEWplus CH4 ObsPack) and satellite (GOSAT) observations. Atmospheric Meas. Tech. 2021, 21, 4637–4657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janardanan, R.; Maksyutov, S.; Tsuruta, A.; Wang, F.; Tiwari, Y.K.; Valsala, V.; Ito, A.; Yoshida, Y.; Kaiser, J.W.; Janssens-Maenhout, G.; et al. Country-Scale Analysis of Methane Emissions with a High-Resolution Inverse Model Using GOSAT and Surface Observations. Remote. Sens. 2020, 12, 375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, S.M.; Michalak, A.M.; Detmers, R.G.; Hasekamp, O.P.; Bruhwiler, L.M.P.; Schwietzke, S. China’s coal mine methane regulations have not curbed growing emissions. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thompson, R.L.; Stohl, A.; Zhou, L.X.; Dlugokencky, E.; Fukuyama, Y.; Tohjima, Y.; Kim, S.; Lee, H.; Nisbet, E.G.; Fisher, R.E.; et al. Methane emissions in East Asia for 2000–2011 estimated using an atmospheric Bayesian inversion. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2015, 120, 4352–4369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergamaschi, P.; Houweling, S.; Segers, A.; Krol, M.; Frankenberg, C.; Scheepmaker, R.A.; Dlugokencky, E.; Wofsy, S.C.; Kort, E.A.; Sweeney, C.; et al. Atmospheric CH4 in the first decade of the 21st century: Inverse modeling analysis using SCIAMACHY satellite retrievals and NOAA surface measurements. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2013, 118, 7350–7369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, W.; Liang, M.; Gao, Y.; Huang, L.; Dan, L.; Duan, H.; Hong, S.; Jiang, F.; Ju, W.; Li, T.; et al. China’s greenhouse gas budget during 2000–2023. Natl. Sci. Rev. 2025, 12, nwaf069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Tian, X.; Wang, X.; Yuan, W.; Ding, J.; Jiang, F.; Jin, Z.; Ju, W.; Liang, R.; et al. Towards verifying and improving estimations of China’s CO2 and CH4 budgets using atmospheric inversions. Natl. Sci. Rev. 2025, 12, nwaf090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Chen, G. China’s CH4 and CO2 emissions: Bottom-up estimation and comparative analysis. Ecol. Indic. 2014, 47, 112–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravishankara, A.R.; Daniel, J.S.; Portmann, R.W. Nitrous Oxide (N2O): The Dominant Ozone-Depleting Substance Emitted in the 21st Century. Science 2009, 326, 123–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanter, D.; Mauzerall, D.L.; Ravishankara, A.R.; Daniel, J.S.; Portmann, R.W.; Grabiel, P.M.; Moomaw, W.R.; Galloway, J.N. A post-Kyoto partner: Considering the stratospheric ozone regime as a tool to manage nitrous oxide. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 4451–4457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prather, M.J.; Hsu, J. Coupling of Nitrous Oxide and Methane by Global Atmospheric Chemistry. Science 2010, 330, 952–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WMO. Scientific Assessment of Ozone Depletion: 2022, GAW Report No. 278; WMO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022; p. 509. Available online: https://ozone.unep.org/science/assessment/sap (accessed on 31 May 2025)ISBN 978-9914-733-97-6.

- Portmann, R.W.; Daniel, J.S.; Ravishankara, A.R. Stratospheric ozone depletion due to nitrous oxide: Influences of other gases. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2012, 367, 1256–1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, H.; Pan, N.; Thompson, R.L.; Canadell, J.G.; Suntharalingam, P.; Regnier, P.; Davidson, E.A.; Prather, M.; Ciais, P.; Muntean, M.; et al. Global nitrous oxide budget (1980–2020). Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2024, 16, 2543–2604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, H.Q.; Xu, R.T.; Canadell, J.G.; Thompson, R.L.; Winiwarter, W.; Suntharalingam, P.; Davidson, E.A.; Ciais, P.; Jackson, R.B.; Janssens-Maenhout, G.; et al. A comprehensive quantification of global nitrous oxide sources and sinks. Nature 2020, 586, 248–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stell, A.C.; Bertolacci, M.; Zammit-Mangion, A.; Rigby, M.; Fraser, P.J.; Harth, C.M.; Krummel, P.B.; Lan, X.; Manizza, M.; Mühle, J.; et al. Modelling the growth of atmospheric nitrous oxide using a global hierarchical inversion. Atmospheric Meas. Tech. 2022, 22, 12945–12960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, F.; Shang, Z.; Ciais, P.; Tao, S.; Piao, S.; Raymond, P.; He, C.; Li, B.; Wang, R.; Wang, X.; et al. A New High-Resolution N2O Emission Inventory for China in 2008. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2014, 48, 8538–8547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Z.; Lam, S.K.; Fu, H.; Hu, S.; Chen, D. Temporal and spatial evolution of nitrous oxide emissions in China: Assessment, strategy and recommendation. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 223, 360–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, R.; Li, Z. Current investigations on global N2O emissions and reductions: Prospect and outlook. Environ. Pollut. 2023, 338, 122664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MEE. Ministry of Ecology and Environment of People’s Republic of China. 2025. Available online: https://www.mee.gov.cn/xxgk2018/xxgk/xxgk03/202504/t20250423_1117396.html (accessed on 20 June 2025).

- Wang, F.; Zhang, J.; Feng, J.; Liu, D. Estimated historical and future emissions of CFC-11 and CFC-12 in China. Acta Sci. Circumstantiae 2010, 30, 1758–1765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Yao, B.; Vollmer, M.K.; Montzka, S.A.; Mühle, J.; Weiss, R.F.; O’Doherty, S.; Li, Y.; Fang, S.; Reimann, S. Ambient mixing ratios of atmospheric halogenated compounds at five background stations in China. Atmospheric Environ. 2017, 160, 55–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpson, I.J.; Barletta, B.; Meinardi, S.; Aburizaiza, O.S.; DeCarlo, P.F.; Farrukh, M.A.; Khwaja, H.; Kim, J.; Kim, Y.; Panday, A.; et al. CFC-11 measurements in China, Nepal, Pakistan, Saudi Arabia and South Korea (1998–2018): Urban, landfill fire and garbage burning sources. Environ. Chem. 2022, 18, 370–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montzka, S.A.; Dutton, G.S.; Yu, P.; Ray, E.; Portmann, R.W.; Daniel, J.S.; Kuijpers, L.; Hall, B.D.; Mondeel, D.; Siso, C.; et al. An unexpected and persistent increase in global emissions of ozone-depleting CFC-11. Nature 2018, 557, 413–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rigby, M.; Park, S.; Saito, T.; Western, L.M.; Redington, A.L.; Fang, X.; Henne, S.; Manning, A.J.; Prinn, R.G.; Dutton, G.S.; et al. Increase in CFC-11 emissions from eastern China based on atmospheric observations. Nature 2019, 569, 546–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Gong, D.; Lv, S.; Ding, Y.; Wu, G.; Wang, H.; Li, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, L.; Wang, B. Observations of High Levels of Ozone-Depleting CFC-11 at a Remote Mountain-Top Site in Southern China. Environ. Sci. Technol. Lett. 2019, 6, 114–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmer, J. The chemists policing Earth’s atmosphere for rogue pollution. Nature 2020, 577, 464–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cyranoski, D. China feels the heat over rogue CFC emissions. Nature 2019, 571, 309–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montzka, S.A.; Dutton, G.S.; Portmann, R.W.; Chipperfield, M.P.; Davis, S.; Feng, W.; Manning, A.J.; Ray, E.; Rigby, M.; Hall, B.D.; et al. A decline in global CFC-11 emissions during 2018−2019. Nature 2021, 590, 428–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adcock, K.E.; Ashfold, M.J.; Chou, C.C.-K.; Gooch, L.J.; Hanif, N.M.; Laube, J.C.; Oram, D.E.; Ou-Yang, C.-F.; Panagi, M.; Sturges, W.T.; et al. Investigation of East Asian Emissions of CFC-11 Using Atmospheric Observations in Taiwan. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2020, 54, 3814–3822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.; Western, L.M.; Saito, T.; Redington, A.L.; Henne, S.; Fang, X.; Prinn, R.G.; Manning, A.J.; Montzka, S.A.; Fraser, P.J.; et al. A decline in emissions of CFC-11 and related chemicals from eastern China. Nature 2021, 590, 433–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tollefson, J. Illegal CFC emissions have stopped since scientists raised alarm. Nature 2021, 590, 373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Yao, B.; Wu, J.; Yang, H.; Ding, A.; Liu, S.; Li, X.; O’dOherty, S.; Li, J.; Li, Y.; et al. Observations and emission constraints of trichlorofluoromethane (CFC-11) in southeastern China: First-year results from a new AGAGE station. Environ. Res. Lett. 2024, 19, 074043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Yang, F.; Li, H.; Li, T.; Cao, F.; Nie, X.; Zhen, J.; Li, P.; Wang, Y. CFCs measurements at high altitudes in northern China during 2017–2018: Concentrations and potential emission source regions. Sci. Total. Environ. 2021, 754, 142290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, M.; Hu, X.; Yao, B.; Li, B.; An, M.; Fang, X. CFC-12 Emissions in China Inferred from Observation and Inverse Modeling. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2024, 51, e2024GL109541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Li, X.; Li, B.; Hu, X.; Fang, X. Concentrations and emissions of trichlorotrifluoroethane (CFC-113) from eastern china inferred from atmospheric observations. Environ. Res. Commun. 2022, 4, 121003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Western, L.M.; Vollmer, M.K.; Krummel, P.B.; Adcock, K.E.; Crotwell, M.; Fraser, P.J.; Harth, C.M.; Langenfelds, R.L.; Montzka, S.A.; Mühle, J.; et al. Global increase of ozone-depleting chlorofluorocarbons from 2010 to 2020. Nat. Geosci. 2023, 16, 309–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourguet, S.; Lickley, M. Bayesian modeling of HFC production pipeline suggests growth in unreported CFC by-product and feedstock production. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 10883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, R.F.; Ravishankara, A.R.; Newman, P.A. Huge gaps in detection networks plague emissions monitoring. Nature 2021, 595, 491–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Flower, R.J.; Thompson, J.R. Eradicate illicit production of ozone-depleting emissions. Nature 2018, 560, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Normile, D. Rogue Ozone-Destroying Emissions Traced to Northeastern China. Science 2019. News, Asia/Pacific. Available online: https://www.science.org/content/article/rogue-ozone-destroying-emissions-traced-northeastern-china (accessed on 5 September 2025).

- Rehm, J. Rogue Chemicals Threaten Positive Prognosis for Ozone Hole. Nature. News. 2018. Available online: https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-018-07269-1 (accessed on 5 September 2025).

- Decades-Old Refrigerators and Insulation from Buildings Are Leaking Ozone-Destroying Chemicals: Nations Must Act. Nature, Editorials. Available online: https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-020-00883-y (accessed on 5 September 2025).

- Officials and Scientists Need Help to Track Down Rogue Source of CFCs. Nature, Editorials. Available online: https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-018-05743-4 (accessed on 5 September 2025).

- Tollefson, J. Rogue Emissions of Ozone-Depleting Chemical Pinned to China. Nature 2019. News. Available online: https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-019-01647-z (accessed on 5 September 2025).

- Tollefson, J. Scientists Call out Rogue Emissions from China at Global Ozone Summit. Nature 2023. News. Available online: https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-023-03325-7 (accessed on 5 September 2025).

- Bourzac, K. This Shouldn’t Be Happening’: Levels of Banned CFCs Rising. Nature 2023. News. Available online: https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-023-00940-2 (accessed on 5 September 2025).

- Fraser, P.J.; Prather, M.J. Uncertain road to ozone recovery. Nature 1999, 398, 663–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chipperfield, M.P.; Hossaini, R.; Montzka, S.A.; Reimann, S.; Sherry, D.; Tegtmeier, S. Renewed and emerging concerns over the production and emission of ozone-depleting substances. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2020, 1, 251–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, L.; Wu, J.; An, M.; Xu, W.; Fang, X.; Yao, B.; Li, Y.; Gao, D.; Zhao, X.; Hu, J. The atmospheric concentrations and emissions of major halocarbons in China during 2009–2019. Environ. Pollut. 2021, 284, 117190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Wu, J.; Liu, Z.; Wang, T.; Hu, D.; Peng, L. Changes in HCFC emissions from foam sector in eastern China from 2000’2019. Environ. Res. Commun. 2024, 6, 061001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vollmer, M.K.; Mühle, J.; Henne, S.; Young, D.; Rigby, M.; Mitrevski, B.; Park, S.; Lunder, C.R.; Rhee, T.S.; Harth, C.M.; et al. Unexpected nascent atmospheric emissions of three ozone-depleting hydrochlorofluorocarbons. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2021, 118, e2010914118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adam, B.; Western, L.M.; Mühle, J.; Choi, H.; Krummel, P.B.; O’dOherty, S.; Young, D.; Stanley, K.M.; Fraser, P.J.; Harth, C.M.; et al. Emissions of HFC-23 do not reflect commitments made under the Kigali Amendment. Commun. Earth Environ. 2024, 5, 783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.; Bie, P.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Jiang, H.; Xu, W.; Zhang, J.; Hu, J. Estimated HCFC-22 emissions for 1990–2050 in China and the increasing contribution to global emissions. Atmospheric Environ. 2016, 132, 77–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Yao, B.; Ma, M.; Hu, X.; Ji, M.; Fang, X. Emissions of HCFC-22 and HCFC-142b in China during 2018–2021 Inferred from Inverse Modeling. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2024, 58, 13273–13283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Yan, H.; Fang, X.; Gao, L.; Zhai, Z.; Hu, J.; Zhang, B.; Zhang, J. Past, present, and future emissions of HCFC-141b in China. Atmospheric Environ. 2015, 109, 228–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Western, L.M.; Redington, A.L.; Manning, A.J.; Trudinger, C.M.; Hu, L.; Henne, S.; Fang, X.; Kuijpers, L.J.M.; Theodoridi, C.; Godwin, D.S.; et al. A renewed rise in global HCFC-141b emissions between 2017–2021. Atmospheric Meas. Tech. 2022, 22, 9601–9616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Wu, J.; Liu, Z.; Wang, T.; Zhang, Y.; Hu, D.; Peng, L. HCFC-141b (CH3CCl2F) Emission Estimates for 2000–2050 in Eastern China. Aerosol Air Qual. Res. 2023, 23, 230001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Yao, B.; Hu, X.; Yang, Y.; Li, B.; Ma, M.; Chi, W.; Du, Q.; Hu, J.; Fang, X. Inverse Modeling Revealed Reversed Trends in HCFC-141b Emissions for China during 2018–2020. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2023, 57, 19557–19564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Wu, J.; Ma, T.; An, M.; Ye, T.; Zhao, X.; Li, M.; Wang, F.; Yuan, M.; Hu, D.; et al. Concentration characteristics and emission estimates of major HCFCs and HFCs at three typical fluorochemical plants in China based on a Gaussian diffusion model. Atmospheric Environ. 2024, 334, 120688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, B.; Vollmer, M.K.; Xia, L.; Zhou, L.; Simmonds, P.G.; Stordal, F.; Maione, M.; Reimann, S.; O’doherty, S. A study of four-year HCFC-22 and HCFC-142b in-situ measurements at the Shangdianzi regional background station in China. Atmospheric Environ. 2012, 63, 43–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanley, K.M.; Say, D.; Mühle, J.; Harth, C.M.; Krummel, P.B.; Young, D.; O’dOherty, S.J.; Salameh, P.K.; Simmonds, P.G.; Weiss, R.F.; et al. Increase in global emissions of HFC-23 despite near-total expected reductions. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, H.; Kim, J.; Choi, H.; Geum, S.; Kim, Y.; Thompson, R.L.; Mühle, J.; Salameh, P.K.; Harth, C.M.; Stanley, K.M.; et al. A rise in HFC-23 emissions from eastern Asia since 2015. Atmospheric Meas. Tech. 2023, 23, 9401–9411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, B.; Fang, X.; Vollmer, M.K.; Reimann, S.; Chen, L.; Fang, S.; Prinn, R.G. China’s Hydrofluorocarbon Emissions for 2011–2017 Inferred from Atmospheric Measurements. Environ. Sci. Technol. Lett. 2019, 6, 479–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lunt, M.F.; Rigby, M.; Ganesan, A.L.; Manning, A.J.; Prinn, R.G.; O’doherty, S.; Mühle, J.; Harth, C.M.; Salameh, P.K.; Arnold, T.; et al. Reconciling reported and unreported HFC emissions with atmospheric observations. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112, 5927–5931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Chen, Y.; Li, Y.; Liu, S.; An, M.; Yao, B.; Western, L.M.; Rigby, M.; Ganesan, A.L.; O’dOherty, S.; et al. Hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs) in Southern China: High-Frequency Observations and Emission Estimates. Environ. Sci. Technol. Lett. 2025, 12, 599–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, M.; Yao, B.; Hu, X.; Li, B.; Chi, W.; Chen, D.; Hu, L.; Velders, G.J.M.; Fang, X. Emissions of HFC-134a in China and Reconciliation of Discrepancies between Observation-Based and Inventory-Based Emission Estimates. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2025, 59, 8506–8515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Q.; Li, B.; Ma, M.; Yao, B.; Fang, X. Estimate Gaps of Montreal Protocol-Regulated Potent Greenhouse Gas HFC-152a Emissions in China Have Been Explained. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2024, 58, 5750–5759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rust, D.; Vollmer, M.K.; Henne, S.; Frumau, A.; Bulk, P.v.D.; Hensen, A.; Stanley, K.M.; Zenobi, R.; Emmenegger, L.; Reimann, S. Effective realization of abatement measures can reduce HFC-23 emissions. Nature 2024, 633, 96–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, L.; Yang, Y.; Fraser, P.J.; Velders, G.J.M.; Liu, Z.; Cui, D.; Quan, J.; Cai, Z.; Yao, B.; Hu, J.; et al. Projected increases in emissions of high global warming potential fluorinated gases in China. Commun. Earth Environ. 2023, 4, 205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; An, M.; Western, L.M.; Prinn, R.G.; Hu, J.; Zhao, X.; Rigby, M.; Mühle, J.; Vollmer, M.K.; Weiss, R.F.; et al. Rising Perfluorocyclobutane (PFC-318, c-C4F8) Emissions in China from 2011 to 2020 Inferred from Atmospheric Observations. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2024, 58, 11606–11614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Sheng, J.; Rigby, M.; Ganesan, A.; Kim, J.; Western, L.M.; Mühle, J.; Park, S.; Park, H.; Weiss, R.F.; et al. Increases in Global and East Asian Nitrogen Trifluoride (NF3) Emissions Inferred from Atmospheric Observations. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2024, 58, 13318–13326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, L.; Fang, X. Mitigation of Fully Fluorinated Greenhouse Gas Emissions in China and Implications for Climate Change Mitigation. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2023, 57, 19487–19496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rust, D.; Vollmer, M.K.; Henne, S.; Bühlmann, T.; Frumau, A.; Bulk, P.v.D.; Emmenegger, L.; Zenobi, R.; Reimann, S. First Atmospheric Measurements and Emission Estimates of HFO-1336mzz(Z). Environ. Sci. Technol. 2023, 57, 11903–11912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- An, M.; Western, L.M.; Say, D.; Chen, L.; Claxton, T.; Ganesan, A.L.; Hossaini, R.; Krummel, P.B.; Manning, A.J.; Mühle, J.; et al. Rapid increase in dichloromethane emissions from China inferred through atmospheric observations. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 7279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, X.; Park, S.; Saito, T.; Tunnicliffe, R.; Ganesan, A.L.; Rigby, M.; Li, S.; Yokouchi, Y.; Fraser, P.J.; Harth, C.M.; et al. Rapid increase in ozone-depleting chloroform emissions from China. Nat. Geosci. 2018, 12, 89–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Quéré, C.; Andrew, R.M.; Friedlingstein, P.; Sitch, S.; Pongratz, J.; Manning, A.C.; Korsbakken, J.I.; Peters, G.P.; Canadell, J.G.; Jackson, R.B.; et al. Global Carbon Budget 2017. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2018, 10, 405–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedlingstein, P.; O’SUllivan, M.; Jones, M.W.; Andrew, R.M.; Hauck, J.; Landschützer, P.; Le Quéré, C.; Li, H.; Luijkx, I.T.; Olsen, A.; et al. Global Carbon Budget 2024. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2025, 17, 965–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, R.; Tong, D.; Xiao, Q.; Qin, X.; Chen, C.; Yan, L.; Cheng, J.; Cui, C.; Hu, H.; Liu, W.; et al. MEIC-global-CO2: A new global CO2 emission inventory with highly-resolved source category and sub-country information. Sci. China Earth Sci. 2024, 67, 450–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooijschuur, E.; Elzen, M.G.D.; Dafnomilis, I.; van Vuuren, D.P. Analysis of cost-effective reduction pathways for major emitting countries to achieve the Paris Agreement climate goal. Glob. Environ. Chang. Adv. 2025, 4, 100014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MEE. Ministry of Ecology and Environment of People’s Republic of China. 2024. Available online: https://www.mee.gov.cn/xxgk2018/xxgk/xxgk06/202401/t20240130_1065242.html (accessed on 5 June 2025).

- Torn, M.S.; Abramoff, R.Z.; Vaughn, L.J.S.; Chafe, O.E.; Curtis, J.B.; Zhu, B. Large emissions of CO2 and CH4 due to active-layer warming in Arctic tundra. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, M.; Mu, C.; Liu, H.; Lei, P.; Ge, Y.; Zhou, Z.; Peng, X.; Ma, T. Thermokarst lake drainage halves the temperature sensitivity of CH4 release on the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 1992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, Z.; Jacob, D.J.; Bloom, A.A.; Worden, J.R.; Parker, R.J.; Boesch, H. Inverse modeling of 2010–2022 satellite observations shows that inundation of the wet tropics drove the 2020–2022 methane surge. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2024, 121, e2402730121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voigt, C.; Virkkala, A.-M.; Gosselin, G.H.; Bennett, K.A.; Black, T.A.; Detto, M.; Chevrier-Dion, C.; Guggenberger, G.; Hashmi, W.; Kohl, L.; et al. Arctic soil methane sink increases with drier conditions and higher ecosystem respiration. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2023, 13, 1095–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oh, Y.; Zhuang, Q.; Liu, L.; Welp, L.R.; Lau, M.C.Y.; Onstott, T.C.; Medvigy, D.; Bruhwiler, L.; Dlugokencky, E.J.; Hugelius, G.; et al. Reduced net methane emissions due to microbial methane oxidation in a warmer Arctic. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2020, 10, 317–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Chang, L.; Hu, Y.; He, Z.; Wang, W.; Wu, D. Warming reduces soil CO2 emissions but enhances soil N2O emissions: A long-term soil transplantation experiment. Eur. J. Soil Biol. 2024, 121, 103614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Liu, R.; Wang, Q.; Gao, X.; Han, Z.; Gao, J.; Gao, H.; Zhang, S.; Wang, J.; Zhang, L.; et al. Climate factors affect N2O emissions by influencing the migration and transformation of nonpoint source nitrogen in an agricultural watershed. Water Res. 2022, 223, 119028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, R.L.; Lassaletta, L.; Patra, P.K.; Wilson, C.; Wells, K.C.; Gressent, A.; Koffi, E.N.; Chipperfield, M.P.; Winiwarter, W.; Davidson, E.A.; et al. Acceleration of global N2O emissions seen from two decades of atmospheric inversion. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2019, 9, 993–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, C.; Jin, S.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, B.; Kanter, D.; Wu, B.; Xi, X.; Zhang, X.; Chen, D.; Xu, J.; et al. Fertilizer overuse in Chinese smallholders due to lack of fixed inputs. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 293, 112913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duren, R.M.; Thorpe, A.K.; Foster, K.T.; Rafiq, T.; Hopkins, F.M.; Yadav, V.; Bue, B.D.; Thompson, D.R.; Conley, S.; Colombi, N.K.; et al. California’s methane super-emitters. Nature 2019, 575, 180–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watine-Guiu, M.; Varon, D.J.; Irakulis-Loitxate, I.; Balasus, N.; Jacob, D.J. Geostationary satellite observations of extreme and transient methane emissions from oil and gas infrastructure. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2023, 120, e2310797120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, J.; Ciais, P.; Chevallier, F.; Canadell, J.G.; van der Velde, I.R.; Chuvieco, E.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, Q.; He, K.; Zheng, B. Enhanced CH4 emissions from global wildfires likely due to undetected small fires. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daskin, J.H.; Pringle, R.M. Warfare and wildlife declines in Africa’s protected areas. Nature 2018, 553, 328–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNEP. United Nations Environment Programme and Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations; Global Nitrous Oxide Assessment: Nairobi, Kenya, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Errickson, F.C.; Keller, K.; Collins, W.D.; Srikrishnan, V.; Anthoff, D. Equity is more important for the social cost of methane than climate uncertainty. Nature 2021, 592, 564–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan-Soo, J.S.; Qin, P.; Quan, Y.; Li, J.; Wang, X. Using cost–benefit analyses to identify key opportunities in demand-side mitigation. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2024, 14, 1158–1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, P.; Zhang, Z.; Chen, L. Environmental co-benefits of climate mitigation: Evidence from clean development mechanism projects in China. China Econ. Rev. 2024, 85, 102182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stechemesser, A.; Koch, N.; Mark, E.; Dilger, E.; Klösel, P.; Menicacci, L.; Nachtigall, D.; Pretis, F.; Ritter, N.; Schwarz, M.; et al. Climate policies that achieved major emission reductions: Global evidence from two decades. Science 2024, 385, 884–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, H.; Zhou, S.; Jiang, K.; Bertram, C.; Harmsen, M.; Kriegler, E.; van Vuuren, D.P.; Wang, S.; Fujimori, S.; Tavoni, M.; et al. Assessing China’s efforts to pursue the 1.5 °C warming limit. Science 2021, 372, 378–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.; Yin, D.; Sun, Z.; Ye, B.; Zhou, N. Global trend of methane abatement inventions and widening mismatch with methane emissions. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2024, 14, 393–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaub, T. Producing adipic acid without the nitrous oxide. Science 2019, 366, 1447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akpan, J.; Olanrewaju, O. A Novel Evaluation Approach for Emissions Mitigation Budgets and Planning towards 1.5 °C and Alternative Scenarios. Atmosphere 2024, 15, 227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanter, D.R.; Winiwarter, W.; Bodirsky, B.L.; Bouwman, L.; Boyer, E.; Buckle, S.; Compton, J.E.; Dalgaard, T.; de Vries, W.; Leclère, D.; et al. A framework for nitrogen futures in the shared socioeconomic pathways. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2020, 61, 102029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riahi, K.; Van Vuuren, D.P.; Kriegler, E.; Edmonds, J.; O’Neill, B.C.; Fujimori, S.; Bauer, N.; Calvin, K.; Dellink, R.; Fricko, O.; et al. The Shared Socioeconomic Pathways and their energy, land use, and greenhouse gas emissions implications: An overview. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2017, 42, 153–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kc, S.; Lutz, W. The human core of the shared socioeconomic pathways: Population scenarios by age, sex and level of education for all countries to 2100. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2017, 42, 181–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, R.; Fan, K.; Qi, Z. Investigation of China’s Anthropogenic Methane Emissions with Approaches, Potentials, Economic Cost, and Social Benefits of Reductions. Atmosphere 2025, 16, 1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).