Abstract

Generalized frosts have a significant impact on the Pampa Húmeda of Argentina, particularly those without persistence (0DP), defined as events that do not last more than one day, and are the most frequent generalized frosts. This study investigates the dynamical and physical mechanisms that sustain these events, emphasizing the nonlinear interactions represented by the Rossby Wave Source (RWS) equation. Composite analysis of pressure, temperature, wind and geopotential height fields were performed, showing that 0DP events are related to abrupt cold air intrusion linked to the enhancement of upper levels troughs over the eastern Pacific Ocean and transient surface anticyclones over South America. This linear analysis only showed a lack of persistent upper-level maintenance and did not explain the dynamics of the rapid weakening of the circulation. For this reason, a nonlinear analysis based on the decomposition of the RWS equation into its advective and divergent terms is performed. The advective term only acts as an initial trigger, deepening troughs and favoring meridional cold air advection, while the divergent term dominates the events, representing 63–67% of the affected area. This term reinforces ridges, promotes subsidence and favors clear sky conditions that enhance nocturnal radiative cooling and frost formation. Positive anomalies of the divergent RWS term strengthen the ridge and advect cold air over the Pampa Húmeda, whereas subsequent negative anomalies over the southwestern Atlantic act as sinks of wave activity, leading to the rapid dissipation of the synoptic configuration. Consequently, the same mechanism that generates favorable conditions for frost development also determines their lack of persistence. These findings demonstrate that the short-lived nature of 0DP frosts is not due to the absence of dynamical forcing, but rather to nonlinear processes that both enable and constrain frost occurrence. This highlights the importance of incorporating nonlinear diagnostics, such as the RWS, to improve the understanding of short-lived atmospheric extremes.

1. Introduction

Few meteorological phenomena influence human activities as directly as frost. Its socio-economic impact is considerable, affecting agriculture, fruit and horticulture production, forestry, energy generation, and food supply chains. Its occurrence depends on the complex interaction between atmospheric dynamics, radiative exchanges and surface characteristics, which together provide favorable conditions for the development of frost formation. Small variations in the mean atmospheric state can induce substantial changes in frost frequency and intensity, highlighting the need to understand the large-scale processes that control its variability [1].

The Pampa Húmeda, located in east-central Argentina, is the country’s most productive agricultural region. Ref. [2] studied frost events in this region and classified them according to their spatial coverage, the generalized frosts (GF) being those with the greatest spatial extent. These events occur mainly between May and September, peaking in July, when large-scale circulation patterns favor the advection of cold air from higher latitudes [3]. The typical configuration of GFs is characterized by an upper-level (200 hPa) ridge over the southeastern Pacific Ocean, a trough over the continent, and surface anticyclones centered over central Argentina, which favor the northward advection of polar air and the development of frost conditions in Pampa Húmeda region [4,5]. This is the classic pattern described in the literature for cold-air outbreaks, where the amplification of the upper-level wave pattern favors the equatorward penetration of polar air masses and the subsequent establishment of a surface anticyclone over southern South America [6,7,8].

Moreover, the teleconnection patterns and Rossby wave propagation with GFs have been extensively examined [9,10,11,12], showing that these events are linked to large-scale Rossby wave trains originating over the subtropical Pacific or Indian Ocean propagating toward South America. These wave trains interact with both the subtropical and polar jets, modulating the upper-level circulation anomalies that precede frost development. One of the propagation patterns typically linked to GFs is a single Rossby wave train that governs the occurrence of less persistent events over the Pampa Húmeda [13]. A similar pattern is observed in events without persistence but with two Rossby wave trains in opposite phase west of the South American continent. This out-of-phase structure weakens the large-scale anomaly pattern, leading to its rapid eastward propagation and the short-lived cold-air intrusion [3]. These events are driven by transient synoptic systems associated with a meridionally oriented Rossby wave train and a weaker meridional circulation, providing less dynamical support to the surface anticyclone and leading to a faster displacement of the system.

Ref. [14] analyzed GF events with and without persistence over the Pampa Húmeda with respect to the origin of the Rossby wave-train propagation source. For the persistence events, they showed that these frosts are modulated by linear dynamical processes, including intraseasonal variability and tropical-extratropical interactions that sustain quasi-stationary Rossby wave trains and prolonged cold-air advection. In contrast, no influence of intraseasonal variability or tropical forcing was identified for without persistence events, which were primarily associated with short-lived synoptic systems that promote temporary stability but do not provide the dynamical support required for consecutive frost days. This result suggests the possible presence of nonlinear interactions that cannot be represented by traditional linear components. In this context, the Rossby Wave Source (RWS) formulation [15] provides a valuable diagnostic tool to examine the nonlinear interaction between the divergent wind and relative vorticity that governs the generation and modulation of planetary waves.

Several studies have examined the dynamics of and variability in RWS in the Southern Hemisphere, particularly during the austral winter [16,17], showed that during the Southern Hemisphere winter, the RWS forcing tends to be located above the high-latitude descending branch of the local Hadley cell, coinciding with upper-level convergence regions. Over South America, the main RWS centers occur over the subtropical South Atlantic Ocean, the eastern South Pacific Ocean, and central-eastern South America, where the divergent component dominates the total forcing, whereas the advective term exerts a more localized influence associated with subtropical anticyclonic anomalies. In addition, ref. [18] examined the seasonal and spatial variability of RWS and found that the divergent term contributes to the generation of wave sources over parts of South America during all seasons, highlighting its role in maintaining upper-level circulation anomalies related to regional climate variability.

Considering these previous studies, the present study applies the RWS approach to investigate the nonlinear dynamical processes that characterize 0DP events in the Pampa Húmeda. These events occur more frequently and are short-lived but spatially extensive. They play a fundamental role in regional climate variability and provide key insights into the atmospheric mechanisms that drive cold-air incursions without persistence. The RWS is decomposed into its advective and divergent components, and the relative contribution of each term is quantified to assess their influence on the development and decay of short-lived frost episodes. This approach provides a new nonlinear perspective on the dynamics of generalized frosts over southern South America, helping to clarify the mechanisms that distinguish transient from persistent events.

This paper is organized as follows: Section 2 describes the data and methods, including the definition of 0DP events and the composite analysis employed to visualize atmospheric circulation and temperature anomalies. Section 3 presents the results, including the analysis of atmospheric variables and a detailed examination of the RWS and its components. Finally, Section 4 summarizes the main findings and highlights their broader implications for understanding frost variability in southern South America.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Observational Data and Study Region Characteristics

The data used in this study correspond to daily minimum temperature records from 41 conventional meteorological stations operated by the National Meteorological Service of Argentina (SMN) and the National Institute of Agricultural Technology (INTA) of Argentina during the extended winter (May–September, MJJAS) from 1974 to 2020. These stations are distributed across the provinces of Buenos Aires, Santa Fe, Entre Ríos, eastern La Pampa, and Córdoba, covering the region known as the Pampa Húmeda.

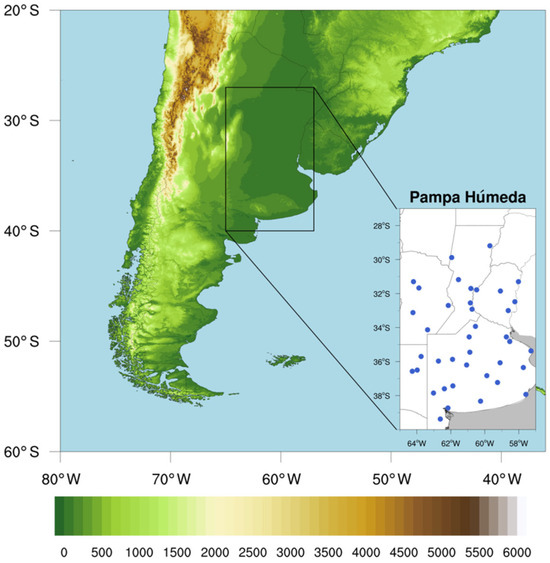

The Pampa Húmeda is an extensive plain located in central-eastern Argentina (27–40° S, 65–57° W; Figure 1), with a surface area exceeding 50 million hectares, characterized by fertile soils and high agricultural productivity.

Figure 1.

South America, including the Pampa Húmeda (black rectangle). Topographical information is shaded, with elevation in meters, obtained from [19]. The smaller map shows the location of the meteorological stations. (Adapted from [20]).

To characterize the regional winter climate, the mean minimum temperature climatology for the extended winter over the 1974–2020 period was calculated, using daily minimum temperature data from all stations within the Pampa Húmeda. On average, winter temperatures reach 5.6 °C across the region.

To better represent typical winter conditions unaffected by frost events, the climatology was computed after removing the days associated with GFs. In this case, the regional mean minimum temperature is 6.0 °C, indicating that GF days are, on average, about 0.4 °C colder than the regional mean computed with GF days. Although modest in magnitude, this difference reflects the strong nocturnal radiative cooling that typically occurs under clear and stable atmospheric conditions conducive to frost formation.

2.2. Without Persistence Generalized Frost

According to the World Meteorological Organization (WMO), frosts are defined when the minimum surface temperature reaches 0 °C or below. Ref. [2] classified the frosts based on its spatial extent. For each day, the ratio between the number of meteorological stations recording frost and the total number of stations with available data is calculated. The result of this ratio defines the classification: isolated frost (IF) when the percentage of stations with frost is less than 25% of the total; partial frost (PF) when this percentage is between 25% and 75%; and generalized frost (GF) when it is greater than or equal to 75%. The 75% threshold was chosen to ensure that generalized frost (GF) events truly represent large-scale cold air outbreaks driven by synoptic systems, rather than localized or mesoscale cooling. In this way, the criterion helps to capture frosts that affect most of the Pampa Húmeda simultaneously, reflecting events of broad regional impact. Ref. [13] grouped GFs according to their persistence, which is defined as the number of consecutive days that follows the first day of the event and comply with the GF condition. Based on this classification, single-day GF events are labeled as 0DP, indicating without persistence, and events with persistence, whereas one-day persistence (1DP) indicates that the GF lasted 2 consecutive days and 2-day persistence (2DP) indicates 3 consecutive days of GF, and so on. According to these criterion, ref. [14] identified 86 0DP generalized frost events in the Pampa Húmeda between May and September from 1974 to 2020, which are the events used in this study.

2.3. Rossby Wave Source Equation

Understanding the RWS equation requires first discussing the theoretical mechanisms behind the generation of these waves [18,21].

Rossby wave forcing can be diagnosed using the barotropic vorticity equation:

where is the absolute vorticity, is the relative vorticity, is the Coriolis parameter, v is the horizontal wind vector, and the horizontal divergence.

The velocity field v can be decomposed into a rotational component , derived from the stream function , and a divergent component , derived from the velocity potential , such that .

This decomposition allows Equation (1) to be written as

Equation (2) separates the Rossby wave propagation terms on the left-hand side, involving only the rotational component, from the forcing terms on the right-hand side, which depend exclusively on the divergent component [15]. Here, divergence refers to the divergence of the horizontal wind field, while divergent wind corresponds to the non-rotational component of the total wind. For simplicity, the term divergence will hereafter be used to refer to the divergence of the horizontal wind. Analysis of this equation indicates that Rossby wave forcing is stronger in regions where divergent wind and the gradient of absolute vorticity are present. These conditions commonly occur poleward of diabatic tropical heating, where upper-level divergence associated with deep convection is enhanced and where strong vorticity gradients linked to jet streams are present. The western Pacific Ocean, east of Australia, exhibits these characteristics, making it a favorable region for Rossby wave train formation. Another region with suitable dynamical conditions for Rossby wave generation is East Asia [22].

The forcing terms can be grouped into a single diagnostic, known as the RWS equation [15]:

This formulation shows that the RWS is not a simple linear response to an external perturbation but arises internally from the coupling of the divergent circulation and the absolute vorticity fields. Expanding the divergence operator makes explicit the two physical contributions:

The first component of Equation (4), usually referred to as the divergent term, represents the modulation of absolute vorticity by the horizontal divergence or convergence of the divergent wind field. It links the rotational flow to vertical motions where upper-level convergence enhances subsidence and favors surface cooling, and where the divergence favors upward motion and facilitates the excitation of wave activity. The second component of Equation (4), known as the advective term, describes the advection of absolute vorticity gradients by divergent wind. This contribution is particularly relevant near the jet stream, where strong vorticity gradients are present, allowing the divergent circulation to project onto these gradients and generate localized vorticity anomalies that act as favorable region for Rossby wave excitation [23].

This configuration captures the nonlinear feedback, in which changes in divergence modify the vorticity distribution, while variations in vorticity alter the divergent circulation, and these two effects combine in a nonlinear way within the source term. Consequently, the RWS represents the intrinsically nonlinear character of Rossby wave excitation. By grouping these two effects into a single divergence operator, Equation (3) highlights that regions where both divergence and pronounced vorticity gradients coexist, they act as efficient generators of RW, while the weakening of this dynamic alignment quickly weakens the forcing. Thus, the RWS can be used as a powerful diagnostic for identifying dynamically active regions of the atmosphere where wave trains can be initiated or reinforced [22].

To identify the dominant RWS term, a dominance metric based on relative intensity was applied, in which the modulus of the divergent term and the modulus of the advective term were calculated at each grid point. When the modulus is used, the influence of opposite signs that could introduce uncertainties is eliminated. To construct binary dominance maps and determine which term dominates at each grid point, the following classification was applied:

where the value 1 indicates that the divergent term is predominant and the value 0 that the advective term is predominant. To quantify spatial dominance, the binary field previously generated was integrated over the selected region. Each grid point was weighted by the cosine of latitude to correct the area difference between the cells at different latitudes. Thus, the fraction of the area where the divergent term prevails over the advective term, and vice versa, was obtained. This method allows a direct comparison of the relative importance of each contribution, without introducing the bias that results from the difference in order of magnitude between the terms [24].

The RWS is computed based on wind and vorticity fields at 200 hPa obtained from the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts (ECMWF) ERA5 reanalysis [25], with a horizontal resolution of 0.25° and 137 vertical levels. This level was chosen because it is where the contribution of divergence and the propagation of large-scale waves are most significant.

2.4. Composite Analysis

The composites were made for the 0DP events (86), from day −3 until day 1. To ensure temporal consistency with the frost event analysis, the hourly ERA5 data were converted into daily mean fields by averaging the original hourly records. The variables used include mean sea level pressure, 2 m air temperature, geopotential height at 200 and 850 hPa, meridional wind at 200 and 850 hPa and zonal wind at 200 hPa. Daily anomalies are calculated with respect to the climatological period 1991–2020. Student’s t-test was utilized to test the statistical significance of the composites at a 0.05 level.

ERA5 reanalysis was chosen because it offers a consistent, high-resolution representation of the atmospheric circulation, providing reliable fields for composite and anomaly analyses [25].

3. Results

A general analysis of pressure, temperature, geopotential height, and wind provides the dynamic context needed to interpret the Rossby wave source. These variables describe the large-scale circulation in which vorticity and divergence signals emerge, allowing a clearer distinction between the relative contributions of tropical and extratropical regimes.

3.1. General Analisys

The general characteristics of the circulation associated with GF events respond to the typical patterns that the literature has shown for cold-air-outbreaks in South America (e.g., [7,26,27]); the following analysis is aimed at analyzing the circulation that characterizes the lack of persistence.

Figure 2 shows the 2 m temperature anomaly and the mean sea level pressure. On day −3 (Figure 3a) negative temperature anomalies are observed over southern Argentina, and the pressure field suggests the early organization of a frontal system. On day −2 (Figure 2b) cold air begins to extend northward into the Pampa Húmeda, while a post-frontal anticyclone develops into the continent and starts to advect polar air northward. On day −1 (Figure 2c) the system is already well established, with negative temperature anomalies over the Pampa Húmeda and the anticyclone entering Argentina, increasing the pressure gradient and directing southerly flow. On day 0 (Figure 2d) intense negative temperature anomalies develop over the Pampa Húmeda under the influence of an intense anticyclone. This configuration favors clear skies, dry air, and weak winds, creating ideal conditions for GFs formation. From day 1 the anticyclone shifts into the Atlantic Ocean, and the pressure gradient and the cooling start to weaken.

Figure 2.

The mean sea level pressure and 2 m temperature anomaly from day −3 to day 1 (a–e). The contours are every 5 hPa. Day 0 corresponds to the day of GF.

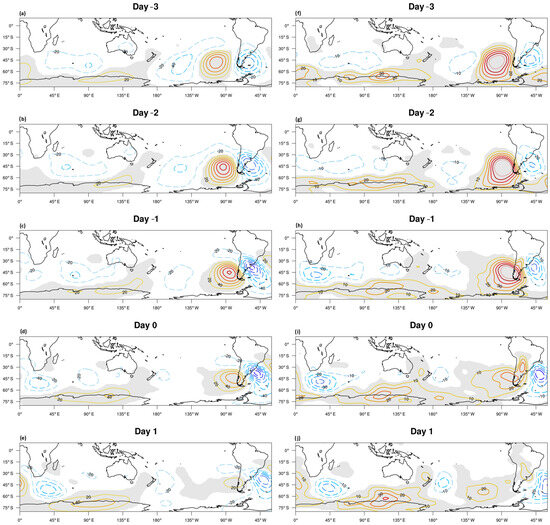

Figure 3.

Anomalies of geopotential height composites from (top to bottom) day −3 to day 1 at (left) 200 hPa (a–e) and (right) 850 hPa (f–j). Positive (negative) contours are in solid (dashed) lines every 20 m. The shaded areas indicate regions with 99% statistical significance according to a Student’s t-test.

The temporal evolution reveals a typical post-frontal configuration over southern South America, in which the rapid progression of cold fronts is followed by the establishment of a transient continental anticyclone. This pattern is consistent with the third principal component of daily surface pressure fields associated with GF events in the Pampa Húmeda, identified by [4]. That component represents a post-frontal anticyclonic circulation with a high-pressure center located north of 40° S that favors the advection of cold and dry air over the continent. This configuration was found by [28] in an analysis of synoptic situations over Argentina related to extreme cold temperatures and by [29] in the composites of the most intense cold surges that produced frosts over subtropical South America (130° W–20° W–80° S–10° S).

A similar synoptic characteristic was described by [3,13], who analyzed the development of persistent and without persistence GF events, respectively. Ref. [13] showed that less persistent GF events are associated with transient post-frontal anticyclones that reinforce surface pressure and enhance nocturnal cooling through subsidence and clear sky conditions. In turn, ref. [3] identified the without persistence GF events, characterized by a transient but intense development on surface high pressure that weakens rapidly and shifts eastward after the cold front passage.

Figure 3 shows the evolution of geopotential height anomalies at 200 hPa (left panels) and 850 hPa (right panels) from day −3 to day 1 of GFs 0DP over the Pampa Húmeda in Argentina. At upper levels (200 hPa), on days −3 (Figure 3a) and −2 (Figure 3b), a trough begins to develop over the southeastern Pacific Ocean, east of South America. These upper-level anomalies are typical of short-wave Rossby disturbances that organize the large-scale circulation and enhance upward motion ahead of the trough. On day −1 (Figure 3c), the trough intensifies and deepens over the southern part of the continent, indicating a marked amplification of the upper-level wave. On day 0, the trough is centered over the southwestern Atlantic Ocean, while a ridge extends over the southeastern Pacific Ocean, west of South America, forming an amplified wave pattern typical of transient baroclinic disturbances. On day 1 (Figure 3e), the trough weakens and shifts eastward into the Atlantic Ocean, indicating the short-lived character of the disturbance and the reestablishment of zonal flow at upper levels.

Comparable upper-level patterns were also reported by [3], which identified, on the day previous and on the day of without persistence GF events, the presence of a ridge extending over the south of the continent and the southeastern Pacific Ocean and a trough over South America. However, in their study, the positive anomalies at upper-levels on day 0 are weaker, while the negative anomalies extended over a larger area than in the present results. In addition, these anomalies dissipated on the following day, highlighting the transient nature of the circulation associated with without persistence GF events. In contrast, here, both features remain evident after day 0 (Figure 3d), although weaker.

At lower levels (850 hPa), on days −3 (Figure 3f) and −2 (Figure 3g), the circulation is still weak but begins to show the early development of an anticyclone over the continent, a typical feature preceding cold air advection. From day −1 (Figure 3h) onward, a well-defined anticyclone becomes established over southern South America and extends northward along the eastern side of the Andes. On day 0 (Figure 3i), the anticyclone strengthens and expands from the southeastern Pacific Ocean into central South America, consistent with the descending branch of the upper-level trough. The out-of-phase structure between the upper and lower levels systems indicates a baroclinic coupling, typical of transient synoptic disturbances. On day 1 (Figure 3j), both the anticyclone and the meridional pressure gradient weaken, leading to a rapid decay of cold-air advection and the dissipation of the baroclinic structure over the Pampa Húmeda.

The analyses of the lower-level patterns showed a similar configuration to the synoptic structure described by [3] for without persistence GF events. In both cases, an anticyclonic anomaly develops over the continent, to the east of the Andes, associated with low-level cold-air advection and the post-frontal development characteristic of these episodes. Similarly, an anticyclone is observed over the southern portion of South America and the southeastern Pacific Ocean, accompanied by a downstream cyclone over the Atlantic Ocean. However, Figure 3f–i shows that the continental anticyclone extends farther north and exhibits higher amplitudes over central South America, while the cyclonic circulation over the Atlantic Ocean is more extensive and just a little more intense than that reported by [3].

Figure 4 shows the evolution of meridional wind anomalies at 200 hPa (left panels) and 850 hPa (right panels) of 0DP GF events over the Pampa Húmeda. At upper levels (200 hPa), positive meridional wind anomalies are identified over the southeastern Pacific Ocean and the southern portion of South America on day −3 (Figure 4a), while negative anomalies are located farther east, over the southwestern Atlantic Ocean. On day −2 (Figure 4b), the positive anomaly intensifies and propagates eastward toward the continent, whereas the negative anomaly over the Atlantic Ocean also strengthens, enhancing the meridional gradient across the region. By day −1 (Figure 4c) the positive anomaly center is positioned over southern South America, while the negative center extends over the southeastern portion of the continent and adjacent Atlantic Ocean, forming a well-defined dipole. On day 0 (Figure 4d), both anomalies shift eastward, with the positive center located over the Pampa Húmeda region and the negative one over the South Atlantic Ocean, indicating the eastward propagation of the upper-tropospheric wave. By day 1 (Figure 4e) the anomalies weaken and shift eastward, confirming the decay and downstream progression of the system.

Figure 4.

Anomaly of meridional wind composites from (top to bottom) day −3 to day 1 at (left) 200 hPa (a–e) and (right) 850 hPa (f–j). Positive (negative) contours are shown in solid (dashed) lines every 2 m s−1. The shaded areas indicate regions with 99% statistical significance according to a Student’s t-test.

The spatial configuration of these upper-level anomalies suggests the presence of a single, arc-shaped Rossby wave train propagating from the central-eastern Pacific Ocean toward South America. Its trajectory closely resembles the propagation patterns described in previous studies. Ref. [13] identified, in the less persistent GF events, an arc-shaped Rossby wave train originating in the central-eastern Pacific Ocean and turning northeastward upon reaching South America. Ref. [3] showed that without persistence GF events are characterized by two Rossby wave trains, one that follows the subtropical jet with a more zonal orientation and another along the polar jet, with a more meridional and curved path. The arc-shaped propagation identified in Figure 4b,c is dynamically consistent with the meridional wave path associated with the polar branch showed by [3].

At lower levels (850 hPa), the meridional wind anomalies are initially weak and unorganized on days −3 (Figure 4f) and −2 (Figure 4g), suggesting that the near-surface circulation responds more gradually to the evolving upper-level structure. From day −1 (Figure 4h) onward, positive (southerly) anomalies begin to develop over the Pampa Húmeda and the southwestern Atlantic Ocean, reaching their maximum amplitude on day 0 (Figure 4i). The strengthening of these anomalies near the surface reflects the southerly flow and the advection of cold air from higher latitudes, consistent with the evolution of the upper-level signal. By day 1 (Figure 4j), the anomalies weaken and move eastward, indicating the progressive decay of the low-level disturbance.

The baroclinic coupling between upper-level and lower-level meridional wind anomalies is consistent with the circulation features described by [3], who associated short-lived frost events with transient post-frontal anticyclones and enhanced meridional gradients that favor transient episodes of cold-air advection over the Pampa Húmeda.

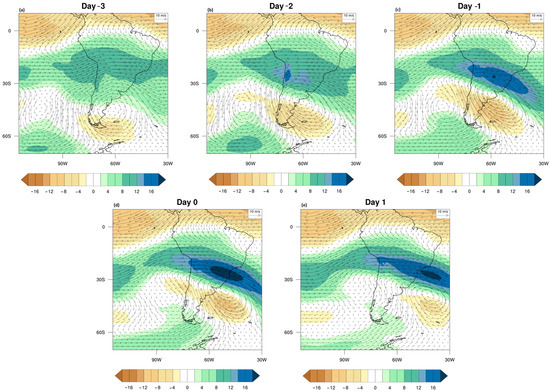

Figure 5 shows the anomaly of zonal wind and wind vector composites at 200 hPa. On days −3 and −2 (Figure 5a,b), the subtropical jet extends from the Pacific Ocean across central South America to the Atlantic Ocean, characterizing a predominantly zonal flow. On day −2 (Figure 5b), the jet begins to intensify, and the deepening of the cyclonic anomaly south of the subtropical jet induces a noticeable curvature in the flow, which starts to exhibit southerly winds over the western part of the continent, indicating the onset of wave amplification (Figure 3b) and the initial organization of the jet structure.

Figure 5.

Anomaly of zonal and vector wind composites at 200 hPa from day −3 to day 1 (a–e).

On day −1 (Figure 5c), the jet axis acquires a more pronounced northwest–southeast orientation, while the cyclone intensifies over the southwestern Atlantic Ocean and an anticyclonic center becomes evident to the west (Figure 3c). In this configuration, the upper-level flow over the jet region is dominated by southwesterly winds, reflecting a stronger baroclinic coupling between the trough (Figure 3c) and the jet core.

On day 0 (Figure 5d), the jet reaches its maximum intensity, with the strongest westerly winds extending over central and southeastern Brazil and the adjacent Atlantic Ocean, while the anticyclone moves eastward (Figure 3d). Over the Pampa Húmeda, the upper-level flow becomes predominantly southeasterly, placing the region on the cyclonic side of the jet exit. This configuration is consistent with upper-level divergence and ascending motion over subtropical latitudes, indicating the onset of a transient baroclinic adjustment. This process favors the reorganization of the circulation and the surface cooling over the region, as shown in Figure 2d.

On day 1 (Figure 5e), the jet weakens, and its core remains over the Atlantic Ocean, with a westerly direction. The wind intensity over the Pampa Húmeda decreases substantially, reflecting the rapid decay of the baroclinic structure.

Comparable upper-level patterns were also reported by [5], which studied the anomalous cold winters in Pampa Húmeda and identified positive zonal-wind anomalies at 250 hPa over the north of Argentina to the beginning of the GF event. In their analysis, the anomalies are predominantly zonal, extending longitudinally along de jet axis. Similarly, the anomalies found here (Figure 5c,d) begin with a flow more zonally and then exhibit a northwest-southeast orientation, indicating a greater curvature of the jet and suggesting a more pronounced wave perturbation during 0DP events.

In addition, ref. [3] analyzed the zonal wind anomalies that occur only for a single-day, i.e., 0DP events, and showed that, on the GF day, a strong zonal-wind anomaly develops over southern South America, while the subtropical jet undergoes a rapid strengthening and subsequent eastward displacement. This configuration is consistent with showed in Figure 5c,d, but the jet was stronger and almost zonal in orientation, with its maximum located to the west of the continent in the day before the event and shifting eastward on the following day. In contrast, in the present composite (Figure 5c,d) the maximum values of the jet are positioned over the eastern part of the continent and the adjacent Atlantic Ocean. Moreover, the jet is comparatively weaker and oriented toward the southeast at day −1 (Figure 5c) and 0 (Figure 5d). This spatial difference suggests that, in the 0DP events analyzed here, the upper-level wave is already in a more advanced stage of eastward propagation, reflecting a more transient system than in the events examined by [3].

The fields showed above indicate that 0DP frost events are associated with the simultaneous action of short-wave disturbances at upper levels and a migratory post-frontal high at the surface. The 200 hPa trough organizes the subtropical jet, strengthening both upper-level divergence and anomalous southerly winds, while at 850 hPa and in the sea-level pressure field a ridge develops that drives polar air into the Pampa Humeda. This vertical configuration provides an intense but transient cold air advection, as the system quickly shifts into the Atlantic Ocean. While these analyses present the synoptic structure, they are still valid only for the linear fields of circulation. For this reason, it is important to examine the nonlinear terms of the RWS equation, since they reveal how the interaction between divergent flow and absolute vorticity acts as a direct forcing for wave propagation. The next section expands the interpretation, changing from the description of circulation patterns to the dynamic mechanisms that sustain or limit the development of these events, offering a more complete view of the transient nature of 0DP frosts.

3.2. Rossby Wave Source

A general assessment of the nonlinear terms of the RWS equation provides deeper insight into the dynamical interactions that modulate frost events. These terms capture the interaction between circulation components that cannot be totally represented by linear diagnostics, highlighting processes that modulate the intensity and persistence of cold-air intrusions.

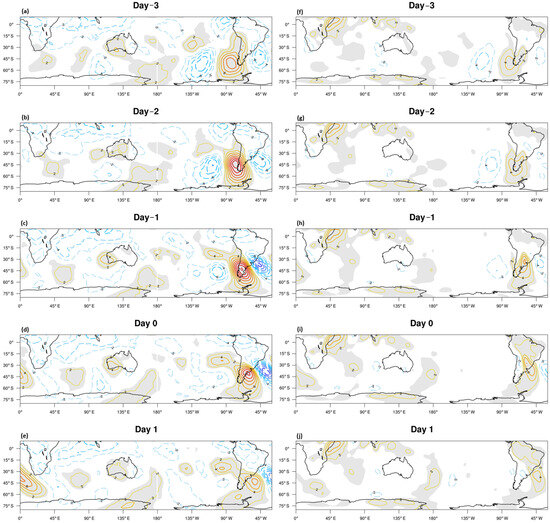

Figure 6 shows the divergence field at 200 hPa for days −3 to 1. In the days before the event (Figure 6a–c), convergence predominates over Argentina, while divergent regions are seen to the east of this region. This pattern is directly related to the divergent term (term 1 of Equation (4)), in which upper-level convergence couples with the prevailing absolute vorticity at midlatitudes to enhance subsidence [15]. Also, it can be identified that the convergence over Argentina, coincides with regions of positive absolute vorticity typical for subtropical and extratropical latitudes [30]. Dynamically, this configuration makes the divergent term positive, where the convergence in a region of positive absolute vorticity intensifies downward motion and reinforces the vertical circulation [15]. Physically, the enhanced subsidence suppresses upward motion, limits cloud formation, and favors clear-sky conditions, which in turn maximize nocturnal radiative cooling at the surface [30]. This combination of processes creates the ideal environment for frost formation. Over the Pacific Ocean, divergence–convergence patterns emerge, indicating that the South American signal is embedded within a larger-scale circulation adjustment. On day 0 (Figure 6d), convergence is still present over the region but begins to weaken and shifts eastward, reducing the persistence of the forcing. On day 1 (Figure 6e), both convergence and divergence centers are displaced into the Atlantic Ocean, and the continental signal has dissipated, confirming the transient character of the event. Similar transient episodes of upper-level convergence linked to midlatitude absolute vorticity have been associated with the modulation of cold-air outbreaks and surface frost occurrence in other regions [22,23].

Figure 6.

Composites of 200 hPa divergence (10−6 s−1) from day −3 to 1 (a–e).

In Figure 7, the fields of absolute vorticity and its gradient are presented for days −3 to 1 (Figure 7a–e), emphasizing the strong role of the subtropical jet. The maxima values of the absolute vorticity follow the midlatitude zonal flow, while strong gradients develop along the jet flanks, indicating areas of shear. These two fields contributed to the divergent term and the advective term (terms 1 and 2 of Equation (4), respectively). Dynamically, large values of absolute vorticity increase the sensitivity of the divergent term, while strong gradients of the latter intensify the advective forcing by allowing the divergent wind to be projected onto shear zones [15,23]. This configuration makes the divergent term positive, where the convergence in a region of positive absolute vorticity intensifies descending motion and reinforces the vertical circulation. Physically, the jet stream provides the driver for Rossby wave excitation, as absolute vorticity maxima intensify the modulation by divergence and marked gradients along the jet flanks favor the redistribution of vorticity by the divergent circulation [30,31]. The enhanced subsidence suppresses upward motion, limits cloud formation, and favors clear-sky conditions, which in turn maximize nocturnal radiative cooling at the surface, creating favorable conditions for frosts [13]. Between day −2 and 0 (Figure 7b–d) it is possible to see over the Pacific Ocean that strong gradients persist along the subtropical jet, indicating an eastward energy flux toward South America. Additionally, in the same period, the jet acts as the primary trigger for the generation of disturbances over the continent and the adjacent Atlantic Ocean. However, the system is not stationary, by day 0 (Figure 7d) the vorticity maxima and their gradients begin to shift eastward, and by day 1 (Figure 7e), they have moved significantly away from South America. This transient behavior explains why the atmospheric response occurs only for a short time, highlighting the temporary character of 0DP events.

Figure 7.

Composites of gradient of 200 hPa vorticity (10−11 m −1 s−1, shaded) and absolute vorticity at 200 hPa (10−5 s−1, contours), from day −3 to 1 (a–e).

Figure 8 illustrates the divergent wind (term 1 of Equation (3)) at 200 hPa, showing how the circulation organizes the redistribution of energy in the upper troposphere. From days −3 to −1 (Figure 8a–c), a divergent-convergent dipole becomes evident between the western and eastern Pacific Ocean, suggesting that the circulation anomalies are part of a larger-scale adjustment that extends across the entire region. Consistent with this, it is possible to see convergence over Argentina and divergence over the adjacent Atlantic Ocean, forming a typical upper level-lower-level coupling pattern. Dynamically, this behavior reflects the advective term (term 2 of Equation (4)), in which the divergent wind projects onto regions of strong vorticity gradients and generates localized Rossby wave activity [15,23]. Physically, the divergent branch over the Atlantic Ocean and the dipole over the Pacific Ocean favor upward motion and the downstream dispersion of energy [30]. In contrast, the convergent branch over Argentina enhances subsidence and intensifies surface cooling. On day 0 (Figure 8d), convergence continues to reinforce surface cooling, but the divergent wind vectors are already reorganizing eastward, and at day 1 (Figure 8e) the divergent wind field has shifted entirely into the Atlantic Ocean, and the Pacific Ocean branch becomes dominant. This rapid reorganization indicates that the circulation does not remain established over the continent, suppressing the development of frosts.

Figure 8.

Composites of divergent wind at 200 hPa, from day −3 to 1 (a–e).

Figure 9 represents the RWS (Equation (4)), which summarizes the nonlinear interactions described above. Between days −3 (Figure 9a) and −1 (Figure 9c), localized centers of wave generation appear over Argentina, confirming that the dynamical ingredients, like upper-level convergence, high absolute vorticity, and strong vorticity gradients, are briefly aligned [15].

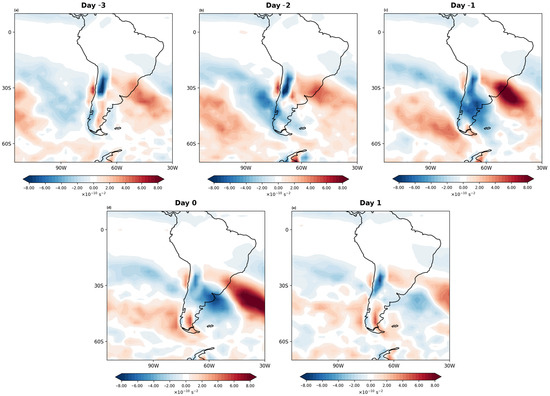

Figure 9.

Composites of Rossby Wave Source (10−11 s−2) at 200 hPa, from day −3 to 1 (a–e).

At the same time, additional RWS anomalies are observed over the Pacific Ocean, indicating that the continent–ocean system is dynamically connected. On day 0 (Figure 9d), the RWS anomalies remain over Argentina but are already weakening and shifting eastward, while the Pacific Ocean anomalies intensify, suggesting that the forcing is being transferred downstream. By day 1 (Figure 9e), the anomalies over South America have almost completely dissipated, with the forcing confined to the Atlantic Ocean and the Pacific Ocean branch dominating the large-scale pattern. Dynamically, this sequence illustrates a transient activation of the RWS over the continent that is quickly overtaken by oceanic anomalies. This explains why generalized frosts without persistence occur in the Pampa Húmeda. The dynamical factors for Rossby wave excitation aligned quickly in the region, but the persistence and large-scale control shift toward the Pacific Ocean. This inhibits the development of a well-defined Rossby wave train, limiting the teleconnection potential of the event [15,22].

The joint analysis of Figure 6, Figure 7, Figure 8 and Figure 9 demonstrates that 0DP events in the Pampa Húmeda originate from a transient configuration of the dynamical ingredients that compose the RWS, including upper-level convergence, high absolute vorticity, strong vorticity gradients, and divergent winds projecting onto those gradients. Over Argentina, this configuration enhances subsidence, reinforces surface cooling, and promotes generalized frost, but the anomalies do not persist. By day 0 they are already shifting eastward, and by day 1 the forcing is confined to the Atlantic Ocean and Pacific Ocean sectors. The migration of these centers toward the ocean demonstrates that continental anomalies are part of a larger-scale circulation adjustment and that the Pacific Ocean plays a central role in redistributing the energy downstream. As a result, the system cannot sustain a well-defined Rossby wave train, limiting the event to a 0DP frost episode without persistent teleconnections [15,22,23].

This evidence highlights the transient character of without persistence frosts. They are dynamically efficient in generating localized RWS anomalies but unable to maintain them long enough to support large-scale wave activity. In the next section, the divergent and advective terms of the RWS are analyzed separately, permitting the identification of the dominant component during 0DP events and offering a clearer understanding of the mechanisms behind their short-lived nature.

3.3. Advective and Divergent Terms

In Figure 10, it is possible to see that the advective term (term 2 of Equation (4)) acts mainly in the early stages of the synoptic evolution, between day −3 and −1, when a NW-SE dipole pattern is observed, with positive values over northwestern South America and negative values over the southwestern Atlantic Ocean, indicating regions of sources and sinks, respectively. This configuration emphasizes the role of the divergent flow that advects absolute vorticity along the subtropical jet, favoring the beginning of wave activity as the development of an extratropical wave train [32]. The intensification on day −1 suggests the intensification of the upper-level trough over South América, that is an important condition for advecting cold air from midlatitudes toward the Pampa Húmeda region, although this configuration does not persist. On day 1 the oceanic sinks intensify while the advective term weakens and disperses, at the same time of the weakening of the anomaly. This transient behavior was also found by [29], who identified upper-level troughs associated with cold-air incursions over southern South America, but without frost occurrence.

Figure 10.

The daily evolution of the advective term of the Rossby Wave Source (10−11 s−2) at 200 hPa, from day −3 to 1 (a–e). Positive values (red shading) represent wave sources, while negative values (blue shading) represent wave sinks.

Figure 11 presents the divergent term (term 1 of Equation (4)), which is more intense over the south of South America and persists for a longer period, playing a central role in the development of the event. From day −3 (Figure 11a) positive values are seen over eastern Argentina and Uruguay and negative values over southern Argentina. This configuration is associated with the coupling between upper-level divergence and extratropical cyclone anomalies. On day −1 (Figure 11c), the divergent terms reach their maximum, with positive sources over the Atlantic Ocean reinforcing the formation of the upper-level ridge, while the subsidence over the Pampa Húmeda favors clear skies, enhancing nocturnal radiative cooling and leading to a favorable environment for frosts formation. This result is consistent with [3] that highlighted the role of transient upper-level ridges and clear sky conditions as one of the elements in the 0DP GFs. However, after day 0 (Figure 11d), negative values are seen over the Atlantic Ocean, making the wave activity dissipate by limiting its persistence. A similar configuration was also suggested by [29] noting that the rapid downstream propagation of extratropical wave trains over the southwestern Atlantic Ocean results in unfavorable conditions for frost formation.

Figure 11.

The daily evolution of the divergent term of the Rossby Wave Source (10−10 s−2) at 200 hPa, from day −3 to 1 (a–e). Positive values (red shading) represent wave sources, while negative values (blue shading) represent wave sinks.

While the advective term triggers the deepening of upper-level troughs, the divergent term acts as the modulating factor that sustains the anticyclonic configuration and the subsidence pattern that induces frost formation. To understand which one of these mechanisms is the dominant one for 0DP events, Figure 12 shows the daily percentage of dominance of each term in the selected region. The percentage was calculated according to the spatial quantification explained in Section 2.

Figure 12.

The relative dominance of the divergent (blue) and advective (orange) terms from day −3 to +1. The dashed line indicates the 50% threshold.

The divergent term dominates the region in a consistent way, around 63% and 67%, indicating that the upper-level divergence is the leading mechanism that sustains the synoptic configuration. Conversely, the advective term remains below 40% throughout the period, with only a slight increase on day −2, suggesting a secondary role as an initial trigger rather than the main sustaining factor.

The advection term, even with its smaller contribution, is relevant in the earlier stage of the events. The initial perturbation generated by this term helps to deepen the upper-level trough over South America, enhancing the meridional circulation that advects cold air toward the Pampa Húmeda, making the advective component to act as the trigger of the cold air intrusion. However, without the later dominance of the divergent term, this intrusion alone would not lead the frost occurrence, in contrast, the divergent term acts like a sustaining mechanism. The combination of the positive anomalies over eastern Argentina and Uruguay and the negative anomalies over the south of Argentina, reflect the interaction between upper-level divergence and extratropical cyclonic anomalies. This configuration intensifies an upper-level ridge over the Atlantic Ocean and induces subsidence over the Pampa Húmeda, favoring the most important factors for frost development, i.e., clear sky and strong nocturnal radiative cooling.

In addition to contributing to frost development, the divergent term explains the non-persistence of 0DP events. While positive anomalies strengthen the ridge and favor subsidence and clear sky conditions before and during day 0, negative anomalies over the southwestern Atlantic Ocean become predominant subsequently. These downstream sinks act as absorbers of wave activity, rapidly weakening the ridge and dissipating the synoptic configuration favorable to cooling. In this way, the divergent term not only sustains the environment that enables frost to occur, but also dictates its short-lived character, underscoring its dual role as both the enabler and the limiter of frost events in the Pampa Húmeda. These downstream sinks suppress wave activity, weakening the ridge and dissipating the synoptic configuration favorable to cold air advection. Accordingly, the divergent term not only preserves the environment that favors frost formation but also determines its transient nature, emphasizing its dual role as both a trigger and an inhibitor of frost in the Pampa Húmeda.

4. Conclusions

Without persistence generalized frosts that occur in the Pampa Húmeda of Argentina are short-lived phenomena that involve both physical and dynamical processes. The analysis of pressure, temperature, wind, and geopotential height fields show that these events result from a rapid cold-air intrusion, favored by the intensification of upper-level troughs over the eastern Pacific Ocean and the strengthening of ridges over southern South America. This interpretation refers only to the mean state of the circulation and does not reveal the dynamic mechanisms responsible for the rapid weakening of the pattern. In other words, linear diagnostics demonstrate the lack of upper-level support, but do not explain how atmospheric interactions modulate the evolution and dissipation of the event. Therefore, the nonlinear theory based on the RWS equation was adopted.

The RWS equation can be decomposed into the advective and divergent terms. The first one acts mainly in the early stages of the event, when the divergent circulation projects onto gradients of absolute vorticity along the subtropical jet, deepening upper-level troughs and intensifying the meridional advection of cold air toward the Pampa Húmeda. While this configuration plays an essential role in promoting the establishment of cooling conditions [29,32], its contribution is secondary in terms of duration, since its influence is limited to the initial phase of the synoptic evolution.

Therefore, the divergent term appears to be the most important in without persistence events, dominating approximately 63–67% of the analyzed area. From a dynamical perspective, this term represents the nonlinear interaction between upper-level divergence and absolute vorticity [15], consolidating the circulation by the intensification of ridges and the subsidence over the Pampa Húmeda. From a physical point of view, it favors clear sky and dry air conditions, which together maximize nocturnal radiative cooling and contribute to frost formation [3,13]. In addition, the dominance of the divergent term also explains the short-lived nature of without persistence frosts. Prior to and during the event, positive anomalies enhance the ridge and advect cold air over the Pampa Húmeda. However, negative anomalies soon move toward the southwestern Atlantic Ocean, acting as a sink for wave activity and soon dissipate the favorable synoptic configuration [22,29]. Thus, the same term that creates the environment for frost conditions also determines its lack of persistence.

In summary, this study shows that the without persistence generalized frosts in the Pampa Húmeda occur not due to the absence of dynamical mechanisms, but rather due to nonlinear processes that modulate atmospheric circulation. The advective term is essential for the initiation of cold air intrusions, but the divergent term dominates the process, explaining the rapid organization of the conditions that generate frosts, but cannot sustain them. These findings expand our understanding of the climatology of frosts in the Pampa Húmeda and highlight the importance of adding nonlinear diagnostics to better explain short-lived atmospheric extremes.

Author Contributions

The authors contributed to the study conception and design. Data analysis were performed by all authors. The first draft of the manuscript was written by M.d.A.G., and the authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The ERA5 reanalysis data that support this study were obtained from the climate datastore of COPERNICUS/ECMWF (see https://cds.climate.copernicus.eu/cdsapp#!/dataset/reanalysis-era5-pressure-levels?tab=overview (accessed on 28 July 2025)).

Acknowledgments

We thank the Servicio Meteorológico Nacional (SMN) and the Instituto Nacional de Tecnología Agropecuaria (INTA) of Argentina for providing the meteorological data.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| RWS | Rossby Wave Source |

| GFs | Generalized Frosts |

| WMO | World Meteorological Organization |

| RW | Rossby Wave |

| ECMWF | European Centre of Medium-Range Weather Forecast |

References

- Fernandez-Long, M.E.; Müller, G.V. Annual and monthly trends in frost days in the Wet Pampa. In Proceedings of the 8th International Conference on Southern Hemisphere Meteorology and Oceanography, Foz do Iguaçu, Brazil, 24–28 April 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Müller, G.V.; Nuñez, M.N.; Seluchi, M.E. Relationship between ENSO cycles and frost events within the Pampa Húmeda region. Int. J. Climatol. 2000, 20, 1619–1637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, G.V.; Berri, G.J. Atmospheric circulation associated with extreme generalized frost persistence in central–southern South America. Clim. Dyn. 2012, 38, 837–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, G.V.; Compagnucci, R.; Nuñez, M.; Salles, A. Surface circulation associated with frosts in the Wet Pampas. Int. J. Climatol. 2003, 23, 943–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, G.V.; Ambrizzi, T.; Nuñez, M. Mean atmospheric circulation leading to generalized frosts in central–southern South America. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 2005, 82, 95–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinclair, M.R. A climatology of anticyclones and blocking for the Southern Hemisphere. Mon. Weather Rev. 1996, 124, 245–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garreaud, R.D. Cold air incursions over subtropical South America: Mean structure and dynamics. Mon. Weather Rev. 2000, 128, 2544–2559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lupo, A.R.; Nocera, J.J.; Bosart, L.F.; Hoffman, E.G.; Knight, D.J. South American cold surges: Types, composites, and case studies. Mon. Weather Rev. 2001, 129, 1021–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, G.V.; Ambrizzi, T. Teleconnection patterns and Rossby wave propagation associated with generalized frosts over southern South America. Clim. Dyn. 2007, 29, 633–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, G.V.; Ambrizzi, T. Rossby wave propagation tracks in Southern Hemisphere mean basic flows associated with generalized frosts over southern South America. Atmósfera 2010, 23, 25–35. [Google Scholar]

- Müller, G.V.; Ambrizzi, T.; Ferraz, S.E. The role of the observed tropical convection in the generation of frost events in the Southern Cone of South America. Ann. Geophys. 2008, 26, 1379–1390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Müller, G.V. Temperature decrease in the extratropics of South America in response to a tropical forcing during the austral winter. Ann. Geophys. 2010, 28, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Müller, G.V.; Berri, G.J. Atmospheric circulation associated with persistent generalized frosts in central–southern South America. Mon. Weather Rev. 2007, 135, 1268–1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregorio, M.A.; Shimizu, M.H.; Müller, G.V. The role of the intraseasonal variability in the generalized frost persistence over southeastern South America. J. South. Hemisph. Earth Syst. Sci. 2025; in press. [Google Scholar]

- Sardeshmukh, P.D.; Hoskins, B.J. The generation of global rotational flow by steady idealized tropical divergence. J. Atmos. Sci. 1988, 45, 1228–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freitas, A.C.V.; Ambrizzi, T. Changes in the austral winter Hadley circulation and the impact on stationary Rossby waves propagation. Adv. Meteorol. 2012, 2012, 980816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freitas, A.C.; Frederiksen, J.S.; O’Kane, T.J.; Ambrizzi, T. Simulated austral winter response of the Hadley circulation and stationary Rossby wave propagation to a warming climate. Clim. Dyn. 2017, 49, 521–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimizu, M.H.; de Cavalcanti, I.F.A. Variability patterns of Rossby wave source. Clim. Dyn. 2011, 37, 441–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NOAA National Centers for Environmental Information. ETOPO 2022 15 Arc-Second Global Relief Model [Dataset]; NOAA National Centers for Environmental Information: Silver Spring, MD, USA, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Shimizu, M.H.; Gregorio, M.A.; Müller, G.V. MJO modulation of air temperature and associated circulation in years with extreme frequency of generalized frosts over southeastern South America. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 2024, 155, 4391–4406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, I.N. Introduction to Circulating Atmospheres; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Kiladis, G.N.; Wheeler, M.C.; Haertel, P.T.; Straub, K.H.; Roundy, P.E. Convectively coupled equatorial waves. Rev. Geophys. 2009, 47, RG2003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takaya, K.; Nakamura, H. A formulation of a phase-independent wave-activity flux for stationary and migratory quasigeostrophic eddies on a zonally varying basic flow. J. Atmos. Sci. 2001, 58, 608–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, K.-H.; Son, S.-W. The global atmospheric circulation response to tropical heating in the upper troposphere. J. Atmos. Sci. 2012, 69, 3981–3995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hersbach, H.; Bell, B.; Berrisford, P.; Hirahara, S.; Horányi, A.; Muñoz-Sabater, J.; Nicolas, J.; Peubey, C.; Radu, R.; Schepers, D.; et al. The ERA5 global reanalysis. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 2020, 146, 1999–2049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marengo, J.A.; Cornejo, A.; Satyamurty, P.; Nobre, C.; Sea, W. Cold surges in tropical and extratropical South America: The strong event in June 1994. Mon. Weather Rev. 1997, 125, 2759–2786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnamurti, T.N.; Tewari, M.; Chakraborty, D.R.; Marengo, J.A.; Silva Dias, P.L.; Satyamurti, P. Downstream amplification: A possible precursor to major freeze events over southeastern Brazil. Weather Forecast. 1999, 14, 242–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Rusticucci, M.; Vargas, W.V. Synoptic situations related to spells of extreme temperatures over Argentina. Meteorol. Appl. 1995, 2, 291–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vera, C.S.; Vigliarolo, P.K. A diagnostic study of cold-air outbreaks over South America. Mon. Weather Rev. 2000, 128, 3–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holton, J.R.; Hakim, G.J. An Introduction to Dynamic Meteorology, 5th ed.; Academic Press: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Vallis, G.K. Atmospheric and Oceanic Fluid Dynamics: Fundamentals and Large-Scale Circulation, 2nd ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoskins, B.J.; Karoly, D.J. The steady linear responses of a spherical atmosphere to thermal and orographic forcing. J. Atmos. Sci. 1981, 38, 1179–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).