Abstract

Yazd province in central Iran is highly prone to dust and sand storms, causing significant environmental, economic, and health impacts. This study investigates the spatiotemporal dynamics of dust storms in Yazd over 2003–2022 using ground-based meteorological station records and satellite-derived aerosol optical depth (AOD) data from MODIS (MYD08_D3 v6.1) at monthly, seasonal, and annual scales. Analysis of ten synoptic stations data revealed an increasing trend of ~0.5 dusty days/year, with the highest frequency in spring and winter, particularly from March to May. MODIS AOD data confirmed these patterns and showed a rising annual aerosol load, peaking in May. Spatial analysis indicated that central and northern regions are most affected, consistent across datasets. The increasing frequency and intensity of dust storms are driven by natural and anthropogenic factors, including regional drought, desertification, drying wetlands, land use changes, and transboundary dust transport (from Iraq, Syria, Saudi Arabia). These findings underscore the value of integrating in situ and remote sensing observations to monitor dust events. To mitigate impacts, policymakers should prioritize long-term environmental monitoring and interventions addressing both natural and human factors influencing dust emissions. This study provides actionable insights for decision-makers to enhance environmental resilience and protect public health in arid regions.

1. Introduction

Aerosols, consisting of minute suspended solid and liquid particles, are introduced into the Earth’s atmosphere from both natural and anthropogenic sources [1]. Natural sources include volcanic eruptions, sea spray, wildfires, and wind-driven soil erosion, whereas anthropogenic emissions primarily arise from industrial activities, biomass burning, transportation, and land use change [1,2]. Human activities, particularly unsustainable agricultural practices, overgrazing, deforestation, and large-scale water management projects (e.g., dam constructions and river diversions), disturb the soil surface, reduce vegetation cover, and intensify land degradation [3]. These disturbances increase soil susceptibility to wind erosion, leading to more frequent and severe dust storms that contribute substantially to regional and global aerosol loads [4]. Among all aerosol types, dust is the most widespread, exerting profound impacts on climate, the water cycle, vegetation, soil stability, and public health [5,6]. Most global dust emissions originate from arid and semi-arid regions with annual precipitation below 200–250 mm, primarily concentrated in the Northern Hemisphere within the so-called “Dust Belt.” This belt extends from the western coast of North Africa to China, with the vast deserts of southwestern Asia—particularly in Saudi Arabia, Syria, Iraq, and Iran—recognized as the primary sources of global dust emission [7,8,9].

Atmospheric dust influences climate and weather both directly and indirectly. It modifies solar radiation fluxes by absorbing and scattering short- and longwave radiation, and alters cloud microphysical processes, affecting precipitation patterns and atmospheric stability [10,11,12]. Dust particles also act as cloud and ice condensation nuclei, influencing cloud properties such as albedo, lifetime, and vertical extent [10]. Large-scale atmospheric circulation patterns play a key role in driving the movement and deposition of dust, thereby influencing regional climates and ecosystem dynamics [13]. Furthermore, dust and other aerosols interact with mesoscale atmospheric processes—such as diurnal tides and near-inertial waves—altering local energy exchanges and weather variability [14]. Long-term satellite data reveal that convective activity and dust transport differ substantially among climate zones, which in turn affects precipitation patterns and atmospheric stability on a regional scale [15]. Dust storms can also reduce visibility and modify the Earth’s radiation balance. On a broader scale, aerosols influence the efficiency of atmospheric water capture, underscoring their importance in shaping hydrological cycles and water availability across regions [16]. Beyond these climatic effects, dust storms pose serious environmental, health, and socio-economic hazards [8,17,18,19]. They are capable of carrying vast amounts of mineral and chemical material over hundreds to thousands of kilometers, leading to soil degradation, diminished crop yields, and disturbances in natural ecosystems. Fine particulate matter (PM10, PM2.5) can penetrate deep into the lungs, aggravating respiratory and cardiovascular conditions and increasing mortality risks. Moreover, dust and particulate matter act as vectors for chemical and biological contaminants, as it was already shown that during haze events ambient particles often contain complex communities of bacteria and fungi, which present additional public health hazards [20]. From an economic perspective, dust storms cause significant disruptions by grounding flights, reducing road visibility, lowering agricultural output, damaging infrastructure, depleting water resources, and hampering power generation. Over time, these processes accelerate soil degradation [21], desertification, and impact ecological imbalance, while also transporting minerals and pollutants across great distances. Furthermore, interactions between industrial by-products—such as red mud particles—and environmental dust can alter the behavior of contaminants in water systems, potentially reducing the efficiency of heavy-metal remediation and degrading water quality in affected regions [22]. Taken together, these diverse environmental, health, and economic consequences highlight the pressing need for comprehensive monitoring systems, advanced predictive modeling, and well-targeted mitigation strategies to minimize the risks associated with dust and particulate pollution [23,24,25,26,27,28].

Historically, analyses of dust storm frequency and long-term variability have depended primarily on observations from meteorological stations. However, this method is often limited by the uneven distribution and sparse density of these stations, especially across arid and desert regions [29,30]. Satellite-based remote sensing has therefore become an invaluable tool, offering broad spatial coverage and the ability to continuously monitor dust activity across regional to global scales [23,31,32]. In recent decades, aerosol optical depth (AOD) derived from satellite measurements has been widely employed to study the spatial and temporal dynamics of dust storms [33,34,35]. Numerous studies have investigated dust storms from different perspectives, including their formation mechanisms [11,36,37], causes and consequences [38,39,40], temporal trends [41,42,43], spatial distribution, and identification of source regions with their transmission pathways [44,45,46]. Globally, dust storms are particularly frequent in North Africa, the Middle East, Mongolia, and northwest China [47,48]. Recent assessments by the World Meteorological Organization (WMO) confirm these regions remain persistent global hotspots, with dust concentrations exceeding long-term averages over southern Mongolia, western Central Asia, and north-central China in 2022–2023 [49]. Further regional studies, for example for East Asia, highlight the Taklamakan Desert in southern Mongolia, and Kazakhstan as primary dust sources for this region, generating storms that travel northwestward, westward, or northward [50], a pattern further supported by recent observational and HYSPLIT model simulations data [51]. In Saudi Arabia, for instance, simulations using the HYSPLIT model in combination with MODIS imagery indicate that most locally generated dust originates from the Rub al-Khali Desert, while regional-scale dust transport primarily occurs from the Sahara and from deserts in Iraq and Syria [52,53]. In addition to these well-known source regions, the Gobi Desert, spanning southern Mongolia and northern China, is another major contributor to East Asian dust events, with aerosols capable of traveling long distances and profoundly influencing both atmospheric conditions and marine ecosystems. For instance, an intense dust event in April 2023 provided a unique opportunity to investigate how dust transport and deposition affect ocean biogeochemistry. By combining satellite observations, ground-based monitoring, and model simulations, the transport pathways, deposition patterns, and subsequent marine phytoplankton responses associated with this event were analyzed [54]. Other regional studies have explored the spatiotemporal dynamics of dust activity to determine the frequency, seasonal variability, and intensity of events. An examination of visibility records from 1973 to 1993 across the Middle East identified four distinct temporal regimes of dust activity. The highest storm frequencies were observed in Sudan, Iraq, Saudi Arabia, and the Persian Gulf region, mainly during spring and summer, with moderate seasonal fluctuations noted in Israel and Egypt [55]. Similarly, in Anhui Province, China, analysis of AOD patterns and their relationship with meteorological conditions revealed that values were lowest in autumn and peaked during spring and summer. Among the influencing factors, wind speed, direction, and relative humidity—particularly recorded at the Fuyang station—were found to exert strong control on AOD variability [24]. Overall, these studies highlight the pronounced regional variability in dust storm frequency, magnitude, and seasonal distribution. Such patterns are closely associated with persistent source regions that act as major emission hotspots. Despite geographical differences, a consistent trend emerges across regions: dust activity typically peaks during warm and dry periods and is strongly regulated by local meteorological conditions, with evidence of increasing spatial and temporal intensity in many parts of the world. These findings emphasize the importance of localized investigations to capture unique environmental drivers and source dynamics, and potential impacts, which are essential for developing effective mitigation and monitoring strategies.

Yazd Province in central Iran represents a region where dust storms are both frequent and severe, producing considerable environmental and economic impacts. The occurrence of these storms is driven by the area’s arid climate, characterized by low rainfall, high evaporation rates, strong and frequent winds, and recurrent droughts with short return periods [56]. Several studies have investigated spatial hotspots, seasonal variations, and long-term trends of dust activity in Iran. For example, the relationship between meteorological variables and AOD was studied in desert regions of Iraq-Syria and Saudi Arabia [9], revealing a strong correlation between monthly temperature and AOD, while precipitation was more closely associated with AOD on an annual scale. Similarly, dust storm patterns in Iran were investigated to find that storm frequency peaked during the warm months of May, June, and July, while reaching its lowest levels in the colder months of November, December, and January [57]. Geographically, the highest activity has been recorded for the southern and central regions of the country, with certain areas recording more than 50 events per year. Additionally, observations from monitoring stations indicate a significant upward trend in storm frequency over recent years. Remote sensing analyses further reveal that over 5% of central Iran constitutes high-potential source zones for sand and dust storms (SDS), where severe drought conditions have intensified storm occurrence [58]. A detailed investigation of intense dust storms that struck southwestern Iran in March 2012, performed using multi-sensor satellite observations (MODIS, OMI, CALIPSO), AERONET data, and ground-based measurements from Ahvaz synoptic station, documented substantial increases in aerosol optical depth—up to 5.2 times higher than normal—and extreme PM10 concentrations reaching 2600 μg/m3. These events were accompanied by drastic reductions in visibility (down to 300 m), temperature (by 12 °C), and humidity (by 23%) during peak pollution periods. CALIPSO profiles showed dust plumes extending to altitudes of nearly 6 km, while simulations using the DREAM and HYSPLIT models corresponded closely with satellite observations, confirming both the storms’ source regions and their spatial extent [59]. Focusing more specifically on Yazd Province, two major dust storms from 2014 were analyzed using a combination of WRF model outputs, HYSPLIT trajectory simulations, and MODIS-derived AOD data [60]. The results demonstrated a strong correlation between modeled and observed patterns, validating the capability of these integrated modeling and remote sensing approaches to accurately identify dust storm sources and transport pathways. More recently, Dasht-e Kavir was identified as the most influential source of dust storms affecting Yazd city [61].

Human activities that degrade land, combined with the accelerating impacts of climate change, have intensified both the frequency and severity of dust storms in recent years. These events not only degrade air quality and threaten human health but also damage agriculture, infrastructure, and ecosystems, leading to substantial economic losses. Despite the growing severity of the problem, comprehensive research on the temporal and spatial characteristics of dust storms—particularly at a provincial scale—remains limited in Iran. Yazd Province, one of the most severely affected regions, has yet to be systematically studied to assess dust storm patterns across monthly, seasonal, and annual timescales. Existing studies have primarily focused either on broader national or regional trends, or on isolated events, leaving a gap in understanding how local environmental drivers and changing climatic conditions influence dust storm dynamics over time. Addressing this gap is critical for developing targeted mitigation measures, improving early warning systems, and informing sustainable land management practices. In this context, the present study investigates the spatiotemporal distribution of dust storms in Yazd Province and analyzes their trends using meteorological and remote sensing data spanning the past two decades (2003–2022), providing one of the first comprehensive long-term assessments of dust activity in Yazd Province. By systematically quantifying observed patterns across monthly, seasonal, and annual scales, this research fills a critical knowledge gap at the provincial level, which was previously lacking in Yazd Province. By providing a comprehensive assessment of dust storm activity, this study offers essential insights for policymakers and environmental managers aiming to reduce future risks and impacts, providing a scientific foundation for more effective dust storm management and climate adaptation policies in Yazd Province and similar arid regions.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

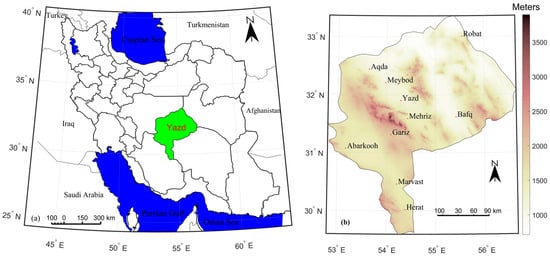

Yazd Province, covering an area of 73,756 km2, is located in central Iran between latitudes 29°36′ and 33°24′ N, and longitudes 45°52′ and 56°42′ E. It accounts for about 5% of Iran’s total area. A large portion of the province consists of barren land and desert areas, representing over 19% of Iran’s desert regions. Mountainous areas are limited, with less than 2% of the province lying above 2500 m in elevation (Figure 1). Moreover, Yazd has the lowest annual rainfall in Iran, with significant spatial and temporal variations in precipitation. Climatically, most of the province is classified as arid or hyper-arid [32,60].

Figure 1.

The geographical location of Yazd province in Iran (a), and digital elevation model (DEM) map of the Yazd province with the synoptical stations’ location marked by red dots (b).

2.2. Data

2.2.1. Synoptic Stations Data

Dust storms primarily reduce atmospheric visibility. To analyze this phenomenon, wind direction, wind speed, and visibility data from 10 synoptic stations across Yazd Province were obtained from the Islamic Republic of Iran Meteorological Organization (IRIMO). Table 1 provides basic information on these stations, which are located in Abarkooh, Aqda, Bafq, Gariz, Herat, Marvast, Mehriz, Meybod, Robat, and Yazd. Their locations are shown in Figure 1. While there are a total of 11 synoptic stations in Yazd Province, the Bahabad station operates automatically and lacks on-site supervision, meaning that visibility measurements are not available. As a result, data from this station were excluded from the visibility analysis. For consistency, the analysis covered a common period for all meteorological stations, from 2003 to 2022.

Table 1.

Specifications of synoptic meteorological stations in Yazd province.

2.2.2. Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) Data

Aerosol optical depth (AOD) is a key parameter for investigating atmospheric pollutants, particularly suspended particles in the atmosphere. It indicates the extent to which aerosols reduce the transmission of light. AOD is a dimensionless measure of the attenuation of solar radiation caused by aerosol scattering and absorption [31,62,63]. Atmospheric Aerosol Optical Depth (AOD) typically falls between 0.1 and 0.15 under clear conditions. Values below 0.3 are generally associated with relatively clean or only slightly polluted air. An AOD of 0.3 suggests moderate pollution, indicating a noticeable presence of aerosols that can reduce visibility and influence air quality, though it does not yet signify heavily polluted conditions often linked to events such as dust storms. Measurements in the 0.3–0.7 range are frequently observed in urban environments or regions with significant human-made emissions. When AOD exceeds 0.5, aerosol loading is considered high, while readings above 0.7 indicate a polluted atmosphere. Levels beyond 1.0 typically correspond to severe pollution, such as episodes of intense dust transport [31,62,63].

The MODIS sensor offers broad spatial and temporal coverage, making its AOD data well-suited for examining the spatiotemporal distribution of dust [24,27,64]. Two MODIS instruments have been in operation: one aboard the Terra satellite since 18 December 1999, and another aboard the Aqua satellite since 4 May 2002, as part of NASA’s Earth Observing System (EOS) program. Terra crosses the equator at approximately 10:30 and 22:30 local time, while Aqua passes at 01:30 and 15:30 local solar time [65,66,67,68].

In this study, we used the Aqua MODIS Level 3 Collection 6.1 Aerosol Product, processed with the Deep Blue (DB) algorithm over land (MYD08_D3 v6.1–Deep Blue, Land Only). The MODIS AOD data at 550 nm, with 1° spatial resolution and daily temporal resolution, were obtained in NetCDF format from https://giovanni.gsfc.nasa.gov/giovanni/ (accessed on 14 March 2025).

2.3. Methods

To determine the frequency of dusty days, hourly visibility (VV) data and current weather condition (WW) reports were analyzed for 10 synoptic stations. According to the World Meteorological Organization (WMO) classification [69], current weather conditions indicating a dust storm are coded as 06–09, 30–35, and 98 (Table 2).

Table 2.

Classification of wet and dry periods according to the standard precipitation index [69].

Visibility serves as both a threshold for defining a dust storm and an indicator of its severity. However, other atmospheric phenomena—such as precipitation, fog, smoke, and mist—can also reduce visibility and are reported accordingly [8,70]. Measurements of visibility and weather conditions are taken every three hours and recorded in SYNOP reports. Dusty days were identified and their frequency analyzed at annual, seasonal, and monthly scales. Additionally, daily aerosol optical depth (AOD) data retrieved from the MODIS Aqua MYD08_D3 product were used to investigate the spatiotemporal distribution of dust storms and their variations in Yazd Province between 2003 and 2022. Due to the differing spatial and temporal resolutions of the two datasets, data consistency was evaluated by assigning the nearest-neighbor MODIS grid cells to each station’s location. Nevertheless, this approach occasionally produced inconsistencies, as the coarse spatial resolution of MODIS imagery limits its ability to represent highly localized dust events. To address this issue, a conceptual and statistical matching method was implemented, focusing on temporal correspondence rather than precise spatial alignment. Specifically, days with elevated regional AOD values observed by MODIS were compared with concurrent ground-based station records showing low visibility and high wind speeds. This cross-validation approach effectively linked satellite-detected dust activity with ground-level observations, capturing both large-scale aerosol patterns from MODIS and localized dust storm occurrences recorded by synoptic stations. The strong agreement between these datasets is consistent with findings reported in previous studies [71].

2.3.1. AutoRegressive Integrated Moving Average (ARIMA)

To evaluate trends in the annual number of dusty days from 2003 to 2022, we applied an AutoRegressive Integrated Moving Average (ARIMA) model, a widely used method for timeseries analysis and forecasting introduced by George Box and Gwilyn Jenkins in 1970 [72]. An ARIMA(p, d, q) model is generally represented as follows:

where Yt is the value of the time series at time t, B is the backshift operator , and is the differencing operator of order d to make the series stationary. is the Autoregressive (AR) polynomial of order p, is the Moving Average (MA) polynomial of order q, and is a white noise error term.

Model selection was performed using the auto.arima() function in R (ver. 4.5.0), which determines optimal ARIMA parameters (p, d, q) based on the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC). Model adequacy was verified by testing the residuals for white noise using the Ljung–Box test. The auto.arima() function identified ARIMA(0,0,0) with a non-zero mean as the best-fitting model. This indicates that the time series requires no differencing (d = 0) and contains no autoregressive or moving average components (p = 0, q = 0). Thus, the model simplifies to a constant mean model, where forecasts for each year correspond to the overall average of observed data. The simplified ARIMA(0,0,0) model can be presented as follows:

where the forecast for any year is simply the overall mean (μ) of the observed annual dusty days.

In addition to ARIMA modeling, the statistical significance of temporal trends was evaluated using the non-parametric Mann–Kendall test [73,74]. This test determines whether a monotonic upward or downward trend exists within a time series without assuming any particular data distribution. It produces the Kendall’s Tau coefficient, which reflects both the direction and strength of the trend, along with a corresponding p-value indicating the result’s statistical significance. To verify model adequacy, the Ljung–Box test was also applied to check whether the residuals depict white noise. The Ljung–Box statistical test, developed by Greta M. Ljung and George E.P. Box, assesses whether autocorrelation is present in a time series [75].

2.3.2. Kriging Interpolation

To illustrate the spatial distribution of dust events, a kriging interpolation method was employed. Kriging is a widely used geostatistical technique based on the concept of random functions. It estimates values at unknown locations using a weighted combination of samples from nearby points. The strength of kriging lies in its objectivity and its ability to predict spatial uncertainty [27,76,77,78]. The fundamental kriging estimator is given by the following:

where is the predicted value at an unvisited location s0, Z(si) is the measured value at the i-th known location si, λi is the kriging weight assigned to the measured value at si, and n is the number of measured points used for the estimation.

3. Results

3.1. Spatiotemporal Variations of Dust Events Using Station Data

3.1.1. Temporal Distribution of the Frequency of Dust Days

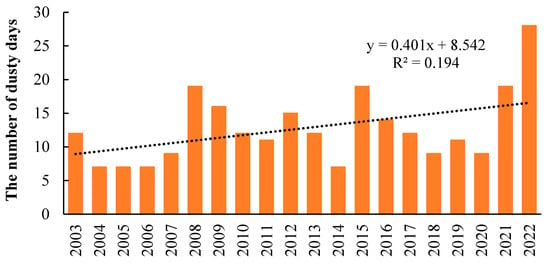

Figure 2 presents the annual number of dusty days in the Yazd province during this period, along with the corresponding trend line. The number of dusty days varied substantially across years. The data reveal notable interannual variability, with the lowest values observed in the mid-2000s and peaks in 2008, 2015, 2021, and particularly 2022, when the number of dusty days reached its maximum at 28. Trend analysis indicates an average annual increase of approximately 0.5 dusty days (Kendall Tau statistic = 0.26; p-value = 0.1119). Although the Kendall Tau statistic suggests a weak-to-moderate positive correlation, the upward trend is not statistically significant. An AutoRegressive Integrated Moving Average (ARIMA) model applied for time-series analysis indicated that estimated mean frequency is 17.1 dusty days per year, with a standard error of 1.6. Model adequacy was confirmed using the Ljung–Box test, which produced a p-value of 0.84, indicating that residuals are consistent with white noise and that the model effectively captures the underlying structure of the data.

Figure 2.

Annual variation in the number of dusty days in Yazd Province from 2003 to 2022.

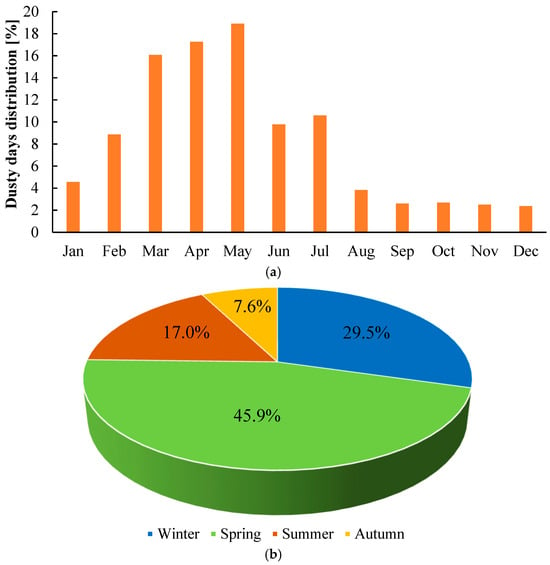

Figure 3 presents the monthly and seasonal distribution of dusty days. The data reveal a distinct seasonal pattern, with dust events occurring most frequently during the spring months. The frequency begins to rise in February (~9%) and reaches its maximum in May (18.9%). March (16.1%) and April (17.3%) also show elevated levels, contributing to the overall springtime peak. In early summer, the frequency of dusty days remains notable, with June and July recording approximately 10% and 11%, respectively. However, a marked decline is observed from August onward. By late summer and autumn, the frequency decreases sharply, with August accounting for about 4% and September for only 2.5%. During winter, dusty days are relatively infrequent, with October through December stabilizing at the lowest levels (~2.5%), while January registers slightly higher value of less than 5%.

Figure 3.

The average monthly (a) and seasonal (b) distribution of dusty days in Yazd province during 2003–2022.

This seasonal pattern is further confirmed by pie chart of Figure 3 (bottom panel), which illustrates the percentage distribution of dusty days across the four seasons. Spring shows the highest frequency, contributing 45.9% of the annual total, followed by winter with 29.5%. Summer accounts for 17.0%, while autumn represents the lowest proportion at 7.6%. This seasonal distribution emphasizes spring as the most active period for dust activity, with winter acting as a secondary peak, while autumn being the season with minimal dust occurrence.

3.1.2. Spatial Distribution of the Frequency of Dust Days

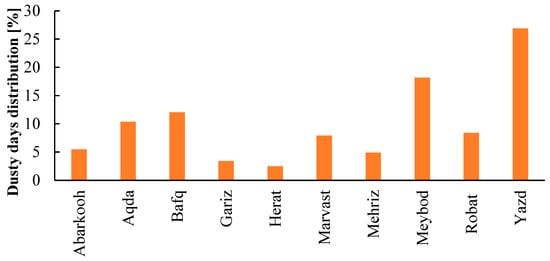

Figure 4 shows the percentage distribution of the number of dusty days across synoptic stations in Yazd Province between 2003 and 2022. Yazd and Meybod stations, located in the northern half of the study area, accounted for over 45% of all dust events during this period. Out of a total of 255 recorded dust events in Yazd Province, 115 were reported at these two stations. Bafq and Aqda also show relatively elevated values, at around 12% and 10%, respectively. Moderate levels are observed in Marvast (~8%) and Robat (~8%), while Abarkoh and Mehriz exhibit lower frequencies, each around 5%. The lowest proportions are recorded in Gariz (~3%) and Herat (~2%), indicating minimal dust activity in these areas. Overall, the results highlight that the climatic conditions around Yazd and Meybod are more favorable for dust storms, and that they are located closer to the primary dust sources.

Figure 4.

The percentage distribution of the number of dusty days across synoptical stations in Yazd province during 2003–2022.

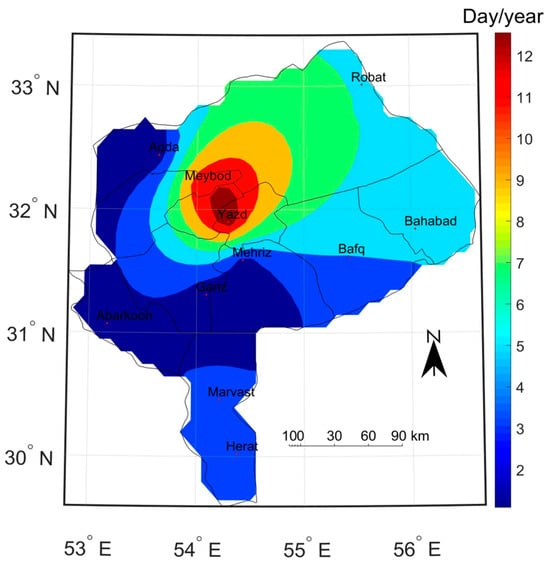

Figure 5 presents the spatial distribution of the mean annual number of dusty days across the Yazd province region, averaged over the study period. The data show a distinct gradient, with the highest frequency of dusty days concentrated in the central part of the province. The central and northern regions, represented by Yazd and Meybod stations, experienced the highest frequency of dust events, with values around 12 days per year, followed by the eastern and northeastern areas of the province (Bahabad and Robat stations vicinity). In contrast, the southern and western parts of the province, such as Abarkouh, Herat, and Marvast, experience fewer dusty days, typically between 3 and 6 days per year. Overall, the figure highlights a clear central hotspot of dust activity, which gradually decreases toward the periphery of the province.

Figure 5.

Spatial distribution of the mean annual number of dusty days (days/year) across Yazd province, averaged over the period 2003–2022.

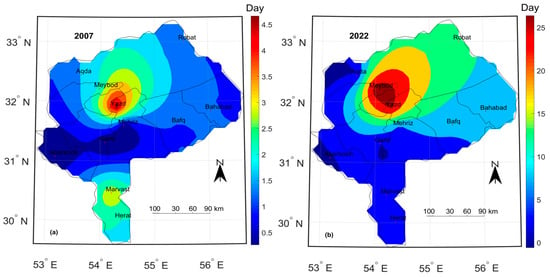

Notably, the number of dusty days varied considerably between years, with the highest and one of the lowest frequencies recorded in 2022 and 2007, respectively (Figure 2). Therefore, the spatial distribution of dusty days in 2007 and 2022 is shown in Figure 6. In 2007, the frequency of dusty days was relatively low, with most areas experiencing fewer than 3 days annually. The central region, particularly around Yazd city and the vicinity of Meybod station, recorded the highest values, reaching up to 4.5 days per year, while the southern and western parts of the province (with Abarkouh, Marvast, and Herat stations) experienced only 1–2 dusty days annually. By contrast, the situation in 2022 shows a substantial intensification in dust activity. The central hotspot around Yazd and Meybod stations expanded significantly, with the number of dusty days exceeding 25 days per year. Surrounding areas, including surroundings of Bahabad, Mehriz, and Robat stations, experienced between 10 and 20 days annually, while the southern and southwestern parts of the province remained relatively less affected, with fewer than 7 dusty days. The spatial patterns for both years largely reflected the long-term mean distribution, although 2007 exhibited a slightly higher frequency of dusty days in the southern regions.

Figure 6.

Spatial distribution of the frequency of dusty days in 2007 (a) and 2022 (b).

3.2. Spatiotemporal Variations of Dust Events Using Aqua MODIS AOD Data

3.2.1. Temporal Variations of Dust Events Using Aqua MODIS AOD Data

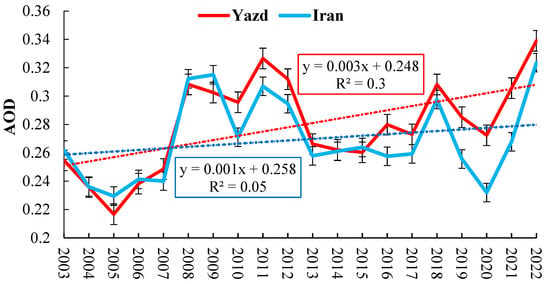

Figure 7 illustrates the temporal variations of the annual mean AOD for Yazd and the whole of Iran over a 20-year period (2003–2022). Both datasets exhibit year-to-year variability, with noticeable peaks around 2008–2011 and 2022. The highest AOD values in Yazd were recorded in 2022 and 2011, with values of 0.34 and 0.33, respectively, while the lowest value occurred in 2005 (0.22). AOD values in Yazd are generally higher than the national average, particularly over the last seven years (2016–2022). Both time series show an increasing trend, but the rate of change in Yazd is nearly three times that of Iran. This suggests that while both regions experienced an overall increase in AOD over the study period, the trend is more pronounced in Yazd, likely reflecting localized environmental and climatic factors influencing aerosol loading. The higher year-to-year fluctuations observed in Iran’s data may be associated with regional-scale variations in dust events, air pollution, and atmospheric circulation patterns. Elevated AOD values in 2008, 2011, 2012, 2018, 2021, and 2022 indicate periods of heightened dust activity in the region.

Figure 7.

Temporal variations of annual mean Aerosol Optical Depth (AOD) over Iran (blue line) and Yazd Province (red line) during 2003–2022.

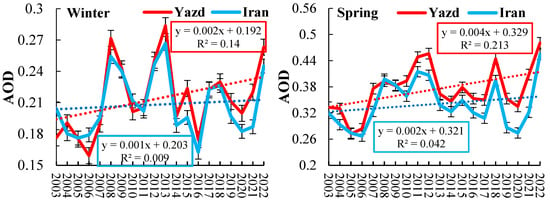

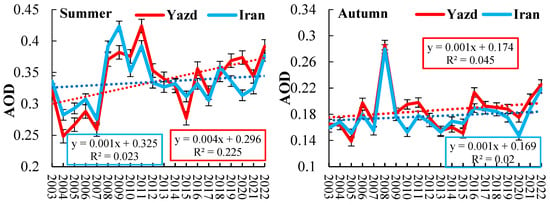

Figure 8 presents the seasonal variability and long-term trends of AOD in Yazd Province (red line) and Iran (blue line) from 2003 to 2022. The highest seasonal mean AOD values occur in spring (0.37) and summer (0.34), while winter and autumn exhibit lower values of 0.21 and 0.19, respectively. Peak spring AOD values in Yazd were observed in 2022 and 2012 (0.48 and 0.46), whereas summer peaks occurred in 2011 and 2022 (0.42 and 0.39). The long-term mean AOD in spring is higher in Yazd (0.37) than in Iran (0.34), while AOD values in other seasons are nearly identical. Trend analysis reveals steeper slopes in spring and summer, indicating a pronounced increase in aerosol loading during these seasons. In particular, Yazd exhibits a 2.4-fold greater slope in spring and a 3.8-fold greater slope in summer compared to the national average. This highlights Yazd’s higher sensitivity to seasonal variations and its greater susceptibility to dust events relative to other regions of the country.

Figure 8.

Seasonal variations of annual mean Aerosol Optical Depth (AOD) over Iran (blue line) and Yazd Province (red line) during 2003–2022.

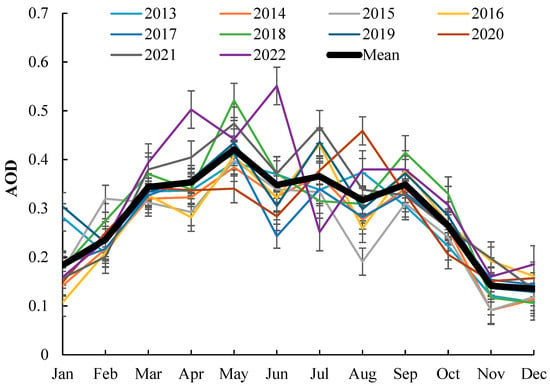

Figure 9 illustrates the monthly variations in aerosol optical depth (AOD) from 2013 to 2022. Except for the years 2016, 2020, and 2022, the highest AOD values were observed in May. For all years except 2022, AOD values decreased in June compared to May. The highest mean monthly AOD during this decade was recorded in June 2022, with a value of 0.55. According to the long-term mean monthly trend (solid black line), AOD values increase from January to May and decrease from September onwards, with the maximum observed in May and the minimum in December.

Figure 9.

The temporal evolution of the monthly mean AOD in Yazd Province during 2003–2022.

3.2.2. Spatial Variations of Dust Events Using Aqua MODIS AOD Data

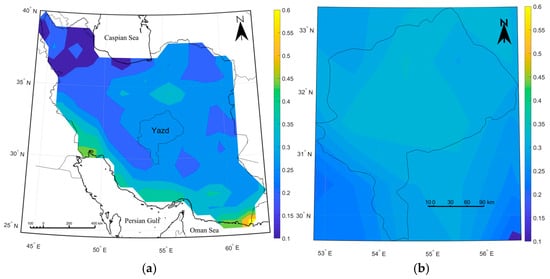

Figure 10 shows the spatial distribution of the long-term mean Aqua MODIS AOD for Yazd Province and Iran from 2003 to 2022. The mean AOD for Yazd Province is 0.28, with minor regional variations between 0.26 and 0.29. For Iran, the mean AOD is 0.27, ranging from 0.16 to 0.51 across different regions. Although the mean AOD in Yazd is slightly higher than the national average, the spatial variations within the province are negligible.

Figure 10.

The spatial distribution of the mean AOD during 2003–2022 for Iran (a) and Yazd province (b).

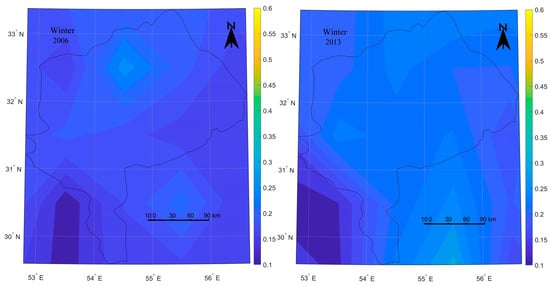

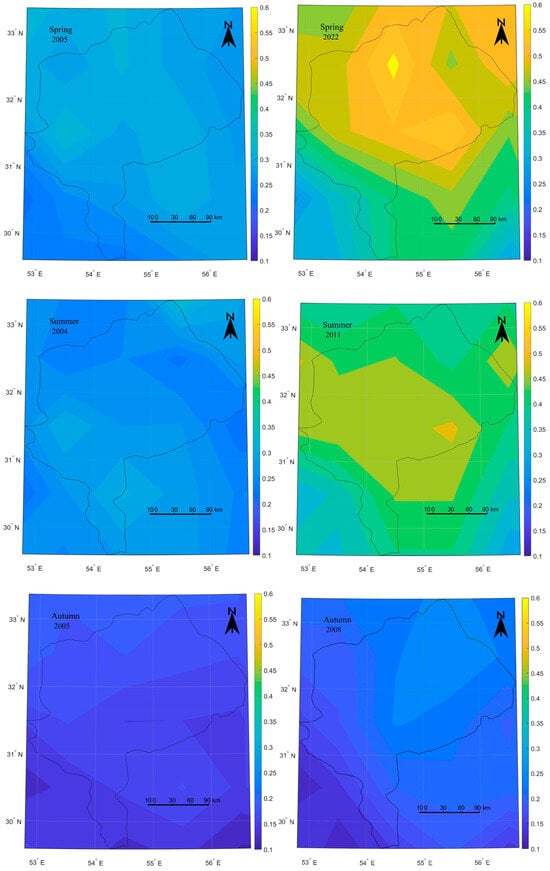

To provide a more comprehensive analysis, the periods with the highest and lowest Aerosol Optical Depth (AOD) values were selected for each season, and spatial distribution maps were generated for the corresponding years (Figure 11). In winter, the lowest and highest AOD values were recorded in 2006 and 2013, respectively, with values of 0.16 and 0.28. For spring, the minimum and maximum AOD values occurred in 2005 and 2022, with values of 0.27 and 0.48. Summer exhibited its lowest and highest AOD values in 2004 and 2022, corresponding to 0.24 and 0.39, respectively. In autumn, the minimum and maximum AOD values were observed in 2005 and 2008, with values of 0.14 and 0.29. The highest AOD values were generally observed during the spring and summer seasons. Notably, the minimum AOD values in these warmer seasons were even higher than the maximum values recorded in winter and autumn. These findings indicate that aerosol impacts on air quality are most pronounced during the warmer months. Further research is therefore needed to better understand the factors driving the seasonal variability of AOD.

Figure 11.

The spatial distribution of mean AOD in the winter of 2006 and 2013, spring of 2005 and 2022, summer of 2004 and 2011, and autumn of 2005 and 2008.

4. Discussion

The analysis of both meteorological station data and MODIS AOD measurements over the 2003–2022 period revealed clear spatiotemporal patterns in dust storm activity across Yazd Province. Our results indicate a general increase in the number of dusty days, with pronounced inter-annual variability ranging from 7 days in the mid-2000s to 28 days in 2022. Dust events were most frequent in the central and northern regions of the province, particularly during spring and winter, with March, April, and May contributing to over half of all observed dusty days. Seasonal analysis of AOD data further confirmed that spring and summer experience the highest aerosol concentrations, while winter and autumn show comparatively lower values. Monthly trends highlighted peak dust activity in May and minimum activity in December. These findings are consistent with previous studies [27,56,57] which reported that dust storms are more intense and frequent during the warmer seasons—particularly spring and summer—across different regions of Iran. The temporal peaks in AOD observed in Yazd—particularly in 2008, 2011, 2012, and 2018—closely align with periods of intense dust storm activity reported across major Middle Eastern dust source regions. The highest AOD values were documented in the Iraq–Syria region during 2008–2009 and in Saudi Arabia during 2012 and 2015, indicating that these regions likely contributed to the elevated dust load over central Iran [9]. Similarly, intensified dust storm events were identified in the UAE in 2011, 2012, and 2018, further supporting the regional nature of dust transport patterns [31]. The correspondence between these periods and Yazd’s AOD peaks suggests strong atmospheric linkages between external dust sources and local air quality degradation.

The increase in the frequency and intensity of dust storms in Yazd Province over the past two decades can be influenced by multiple factors. Therefore, the sources and mechanisms driving dust storms in this region should be carefully investigated. Identifying the sources of dust is a crucial first step in developing effective strategies to control these events and mitigate their destructive impacts [31]. Dust storms in the study area arise from both internal and external sources. Iraq, Saudi Arabia, and Syria are recognized as major external dust sources for Iran [17,79]. It was found that the majority of dust transported to Yazd originates from Dasht-e Kavir [61]. The Gavkhoni Wetland, located in central Iran, has experienced significant drying over the past three decades due to reduced in-flows, rising temperatures, and increased evaporation. Positioned northwest of Yazd Province and aligned with prevailing winds, the dried wetland bed can act as an internal dust source, contributing to dust transport, particularly toward the northwestern regions of the province [80]. Additionally, desertification in regions such as the deserts of Qom and the Meyghan Wetland in Markazi Province—situated along the path of dust transported from western Iran and neighboring countries—has also intensified the frequency and severity of dust events in Yazd Province [81,82,83].

Dust storm activity across the Middle East arises from a complex interaction between natural drivers and human-induced pressures. Natural processes such as climatic variability, prolonged droughts, and desertification are the dominant contributors to dust emissions, particularly in arid and hyper-arid environments. Globally, natural sources are estimated to account for about 81% of total dust emissions, while human activities contribute approximately 19% [84]. Despite this general understanding, the relative influence and combined effects of these factors on dust storm formation remain insufficiently quantified, with substantial uncertainties still present [85]. In the Middle East, climate variability—marked by declining precipitation and rising temperatures—is increasingly intertwined with anthropogenic influences, including deforestation, unsustainable agricultural practices, vegetation loss, water resource mismanagement, and dam construction. Notably, large-scale hydraulic projects such as Turkey’s Southeastern Anatolia Project (GAP) have altered river discharge patterns, accelerated wetland desiccation, and exacerbated soil degradation in downstream regions, collectively intensifying dust emissions [58,79,86]. Drought has also played a crucial role in amplifying dust activity throughout the region. In Iraq, for instance, the number of dusty days per year rose from 75 to nearly 200 between 1960 and 2022, a trend driven by a 2 °C increase in temperature and a marked reduction in rainfall [79]. It has also been revealed that since 2000 regional water bodies have shrunk by more than 50% [58]. Corresponding findings have been reported for Khuzestan Province in southwestern Iran, where strong correlations were observed between meteorological drought severity and dust storm frequency [87]. Similarly, dust events in western Iran have been linked to drought conditions in major source areas across Iraq and Syria [88]. Overall, these observations indicate that while natural climatic processes remain the primary drivers of dust generation in the Middle East, human-induced land use changes and environmental degradation have increasingly amplified both the frequency and intensity of dust storms in recent decades.

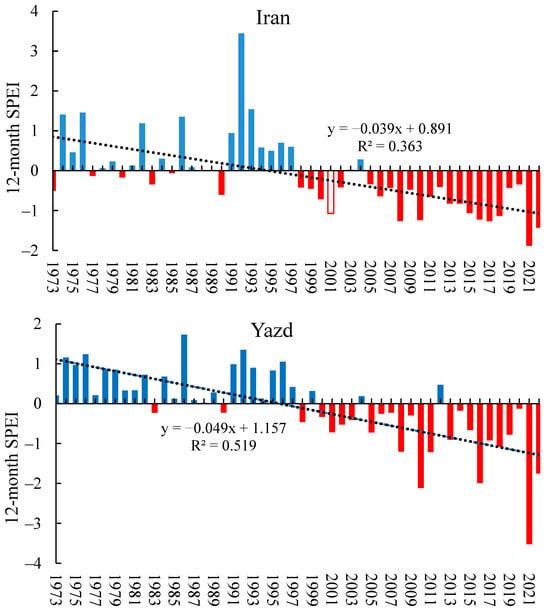

Analysis of the standardized precipitation-evapotranspiration index (SPEI12) over the last 50 years indicates a decreasing trend in both Iran and Yazd Province, reflecting increasing drought severity (Figure 12). Consecutive droughts have dominated Iran over the past 25 years, with the exception of 2003 and 2004, and drought intensity has increased in recent years.

Figure 12.

Time series of 12-month SPEIs in Iran and Yazd Province during 1973–2022.

Additionally, war and insecurity in Iraq and Syria, which have led to population migration into areas with fragile ecosystems and extensive land use changes, are human factors that have reduced the capacity of governments to respond effectively to extreme climate events such as drought and dust storms [58,79]. It is also important to note that the impacts of severe dust storms are not confined to national borders but extend far beyond the regions from which they originate. Therefore, the active participation of neighboring countries is essential to address this issue.

5. Conclusions

The primary goal of this study is to examine the spatiotemporal distribution of dust and its variations in Yazd Province over a 20-year period. While visibility data from meteorological stations provide valuable information on dust events within their coverage areas, the limited number of stations—particularly in desert regions like Yazd—only captures a small portion of the study area. A major limitation, particularly in developing countries, is the lack of continuous and comprehensive monitoring of particulate matter (PM10, PM2.5, and smaller particle fractions). This data gap poses a serious challenge for accurately assessing dust storm intensity, identifying emission sources, and evaluating associated health impacts. Addressing this issue requires expanding the network of air quality monitoring stations to ensure continuous, high-quality particulate matter observations across affected regions. Satellite remote sensing provides an effective complementary tool, offering extensive spatial coverage and enabling the identification of dust-affected areas. Such data are invaluable for mitigating the impacts of dust storms on public health, transportation, and safety. However, satellite observations alone cannot capture fine-scale local variations, highlighting the need to integrate ground-based measurements with remote sensing data for a more comprehensive analysis. The dual-source approach adopted in this study—combining synoptic station records with satellite observations—enabled a more robust spatial and temporal assessment of dust activity, despite the limited number of monitoring stations and the absence of particulate matter data. This integration significantly enhanced the reliability of the detected dust storm trends.

Analysis of weather station data indicates an increasing trend in the number of dusty days from 2003 to 2022, although significant inter-annual variability was observed, ranging from 81 days in 2007 to 371 days in 2022. Over 75% of dust storms occurred in spring and winter, with March, April, and May recording the highest number of dusty days, accounting for approximately 52% of all observations during the study period. Evaluation of aerosol optical depth (AOD) data revealed relatively small inter-annual variations. The maximum and minimum seasonal long-term mean AOD values occurred in spring and autumn, with values of 0.37 and 0.19, respectively. Monthly AOD values increased from January to May and decreased from September onwards, with the highest long-term monthly mean observed in May and the lowest in December. The spatial distribution patterns derived from both station and satellite data were in strong agreement, indicating that the central and northern regions, followed by the eastern areas, were the most affected by dust storms. In addition to confirming well-established seasonal patterns, the findings reveal an increasing frequency and intensity of dust storms over the past two decades. These changes are closely linked to both natural factors (such as drought, desertification, and the drying of wetlands) and human activities (including land use change and cross-border dust transport from neighboring countries). By systematically analyzing dust storm occurrences across monthly, seasonal, and annual scales, this study fills an important knowledge gap at the provincial level—a scale previously underexplored in Iran. Given the accelerating effects of global warming, the frequency of extreme events like dust storms is expected to rise, particularly in arid and semi-arid regions. Therefore, continuous and systematic monitoring is essential for guiding mitigation strategies and evaluating the effectiveness of control measures.

Consequently, future research should focus on long-term simulations of dust activity using regional climate models under varying environmental and socio-economic scenarios to assess changes in dust concentrations and source dynamics. Detailed investigations into the relationships between dust occurrence and influencing factors—such as climatic conditions, vegetation cover, and soil erosion—are also necessary. Furthermore, the development of dust emission and transport simulation models will be critical for distinguishing and quantifying the relative contributions of natural and anthropogenic sources. Identifying the extent of human influence on dust generation, particularly in relation to health risks, is especially important in light of the rapid expansion of industrial and mining activities in Yazd Province. Complementary studies should also analyze the chemical composition, mineralogy, and potential toxicity of dust particles, especially in industrial zones, to better understand their environmental and public health implications.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.S. and I.R.; Data curation, M.S. and I.R.; Formal analysis, M.S. and I.R.; Investigation, M.S., I.R., F.P. and J.K.; Methodology, M.S. and I.R.; Project administration, H.O. and J.K.; Resources, M.S. and I.R.; Software, I.R.; Supervision, H.O., F.P. and J.K.; Validation, M.S., I.R., H.O., F.P. and J.K.; Visualization, I.R.; Writing—original draft, M.S., I.R. and J.K.; Writing—review & editing, H.O., F.P. and J.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by Vedurfelagid, Rannis and Rannsoknastofa i vedurfraedi.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The Aqua MODIS Level 3 Collection 6.1 Aerosol Product data used in this study are available at https://giovanni.gsfc.nasa.gov/giovanni/ (accessed on 14 March2025). Restrictions apply to the availability of synoptic station data. These data were obtained from the Islamic Republic of Iran Meteorological Organization (IRIMO) and are available upon request to the data provider. The original contributions presented in this study are included within the article. Further data-related inquiries can be directed to Iman Rousta at irousta@yazd.ac.ir.

Acknowledgments

Iman Rousta is deeply grateful to his supervisor (Haraldur Olafsson from Atmospheric Sciences, Institute for Atmospheric Sciences-Weather and Climate, and Department of Physics, University of Iceland, and Icelandic Meteorological Office (IMO)), for his great support, kind guidance, and encouragement.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Rap, A.; Scott, C.E.; Spracklen, D.V.; Bellouin, N.; Forster, P.M.; Carslaw, K.S.; Schmidt, A.; Mann, G. Natural aerosol direct and indirect radiative effects. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2013, 40, 3297–3301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zucca, C.; Fleiner, R.; Bonaiuti, E.; Kang, U. Land degradation drivers of anthropogenic sand and dust storms. Catena 2022, 219, 106575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Middleton, N. Rangeland management and climate hazards in drylands: Dust storms, desertification and the overgrazing debate. Nat. Hazards 2018, 92, 57–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Caballero, E.; Belnap, J.; Büdel, B.; Crutzen, P.J.; Andreae, M.O.; Pöschl, U.; Weber, B. Dryland photoautotrophic soil surface communities endangered by global change. Nat. Geosci. 2018, 11, 185–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goudie, A.; Middleton, N. Desert Dust in the Global System; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Attiya, A.A.; Jones, B.G. An extensive dust storm impact on air quality on 22 November 2018 in Sydney, Australia, using satellite remote sensing and ground data. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2022, 194, 432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Graaf, M. Remote Sensing of UV-Absorbing Aerosols Using Space-Borne Spectrometers. Ph.D. Thesis, Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2006; 132p. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, M.; Westphal, D.L.; Wang, S.; Shimizu, A.; Sugimoto, N.; Zhou, J.; Chen, Y. A high-resolution numerical study of the Asian dust storms of April 2001. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2003, 108, 8653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Namdari, S.; Karimi, N.; Sorooshian, A.; Mohammadi, G.; Sehatkashani, S. Impacts of climate and synoptic fluctuations on dust storm activity over the Middle East. Atmos. Environ. 2018, 173, 265–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaufman, Y.J.; Tanré, D.; Boucher, O. A satellite view of aerosols in the climate system. Nature 2002, 419, 215–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Middleton, N.J. Desert dust hazards: A global review. Aeolian Res. 2017, 24, 53–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kok, J.F.; Ward, D.S.; Mahowald, N.M.; Evan, A.T. Global and regional importance of the direct dust-climate feedback. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Y.; Lu, M.; Chen, D.; Zhang, L. Understanding the weakening patterns of inner Tibetan Plateau vortices. Environ. Res. Lett. 2024, 19, 064076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Qiu, C.; Wang, D.; Chen, Z.; Hibiya, T.; Xie, X.; Yu, X. Kinetic energetic exchange between near-inertial waves and mesoscale eddy/diurnal tide during Typhoon Rai. J. Phys. Oceanogr. 2025, 55, 1033–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Wang, J.; Zuo, H.; Fu, Z.; Xiao, W.; Cui, Y.; Zhou, Z. Spatiotemporal distribution and variation characteristics of convective activities in different climate zones in northern China based on 25 years of satellite observations. Int. J. Climatol. 2025, 45, e8908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.F.; Lu, H.L.; Wang, G.Q.; Qiu, J. Long-term capturability of atmospheric water on a global scale. Water Resour. Res. 2024, 60, e2023WR034757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashrafi, K.; Shafiepour-Motlagh, M.; Aslemand, A.; Ghader, S. Dust storm simulation over Iran using HYSPLIT. J. Environ. Health Sci. Eng. 2014, 12, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Middleton, N. Variability and trends in dust storm frequency on decadal timescales: Climatic drivers and human impacts. Geosciences 2019, 9, 261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Middleton, N.; Kashani, S.S.; Attarchi, S.; Rahnama, M.; Mosalman, S.T. Synoptic causes and socio-economic consequences of a severe dust storm in the Middle East. Atmosphere 2021, 12, 1435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.; Yu, C.; You, Y.; Li, C.; Zhang, J.; Xiang, S.; Hao, K.; Chen, J. Bacteriome and mycobiome in ambient PMs during haze episodes and health hazard: A nationwide survey in China. Energy Environ. Sustain. 2025, 1, 100023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarwar, A.; Ali, M.; Israr, M.; Gulzar, S.; Khan, M.I.; Ali, M.A.S.; Majid, A.; Rukh, S. Mapping annual soil loss in the southeast of Peshawar basin, Pakistan, using RUSLE model with geospatial approach. Geol. Ecol. Landsc. 2025, 9, 1102–1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, B.; Bai, F.; Li, X.; Nie, Q.; Jia, X.; Wu, H. The remediation efficiency of heavy metal pollutants in water by industrial red mud particle waste. Environ. Technol. Innov. 2022, 28, 102944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crosbie, E.; Sorooshian, A.; Monfared, N.A.; Shingler, T.; Esmaili, O. A multi-year aerosol characterization for the greater Tehran area using satellite, surface, and modeling data. Atmosphere 2014, 5, 178–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, X.; Shi, C.; Wu, B.; Chen, Z.; Nie, S.; He, D.; Zhang, H. Analysis of aerosol characteristics and their relationships with meteorological parameters over Anhui province in China. Atmos. Res. 2012, 109, 52–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knippertz, P.; Todd, M.C. Mineral dust aerosols over the Sahara: Meteorological controls on emission and transport and implications for modeling. Rev. Geophys. 2012, 50, RG1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Middleton, N.; Kang, U. Sand and dust storms: Impact mitigation. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Namdari, S.; Valizade, K.; Rasuly, A.; Sari Sarraf, B. Spatio-temporal analysis of MODIS AOD over western part of Iran. Arab. J. Geosci. 2016, 9, 191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qor-el-aine, A.; Beres, A.; Geczi, G. Dust storm simulation over the Sahara Desert (Moroccan and Mauritanian regions) using HYSPLIT. Atmos. Sci. Lett. 2022, 23, e1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minder, J.R.; Mote, P.W.; Lundquist, J.D. Surface temperature lapse rates over complex terrain: Lessons from the Cascade Mountains. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2010, 115, D14122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyler, J.W.; Dobrowski, S.Z.; Holden, Z.A.; Running, S.W. Remotely sensed land skin temperature as a spatial predictor of air temperature across the conterminous United States. J. Appl. Meteorol. Climatol. 2016, 55, 1441–1457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhebsi, K. Spatio-Temporal Variability of Aerosol Optical Depth in the UAE Using MODIS Data. Master’s Thesis, George Mason University, Fairfax, VA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirgholami, M.R.; Masoodian, S.A.; Montazeri, M. Investigation of environmental changes in arid and semi-arid regions based on MODIS LST data (case study: Yazd province, central Iran). Arab. J. Geosci. 2023, 16, 514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, Z.; Zhu, C.; Hulugalla, R.; Gu, J.; Di, G. Spatial and temporal characteristics of aerosol optical depth over East Asia and their association with wind fields. Meteorol. Appl. 2008, 15, 455–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butt, M.J.; Assiri, M.E.; Ali, M.A. Assessment of AOD variability over Saudi Arabia using MODIS Deep Blue products. Environ. Pollut. 2017, 231, 143–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, X.; Tang, C.; Wu, X.; Yang, J.; Zhao, F.; Liu, D. The global spatial-temporal distribution and EOF analysis of AOD based on MODIS data during 2003–2021. Atmos. Environ. 2023, 302, 119722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baltaci, H. Meteorological characteristics of dust storm events in Turkey. Aeolian Res. 2021, 50, 100673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Rahn, K.A.; Zhuang, G. A mechanism for the increase of pollution elements in dust storms in Beijing. Atmos. Environ. 2004, 38, 855–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jish Prakash, P.; Stenchikov, G.; Kalenderski, S.; Osipov, S.; Bangalath, H. The impact of dust storms on the Arabian Peninsula and the Red Sea. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2015, 15, 199–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miri, A.; Ahmadi, H.; Ekhtesasi, M.R.; Panjehkeh, N.; Ghanbari, A. Environmental and socio-economic impacts of dust storms in Sistan Region, Iran. Int. J. Environ. Stud. 2009, 66, 343–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashki, A.; Middleton, N.J.; Goudie, A.S. Dust storms in Iran–Distribution, causes, frequencies and impacts. Aeolian Res. 2021, 48, 100655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aili, A.; Oanh, N.T.K.; Abuduwaili, J. Variation trends of dust storms in relation to meteorological conditions and anthropogenic impacts in the northeast edge of the Taklimakan Desert, China. Open J. Air Pollut. 2016, 5, 127–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Indoitu, R.; Orlovsky, L.; Orlovsky, N. Dust storms in Central Asia: Spatial and temporal variations. J. Arid Environ. 2012, 85, 62–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Xu, H.; Lan, J.; Goldsmith, Y.; Torfstein, A.; Zhang, G.; Zhang, J.; Song, Y.; Zhou, K.E.; Tan, L. Dust storms in northern China during the last 500 years. Sci. China Earth Sci. 2021, 64, 813–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, H.; Amiraslani, F.; Liu, J.; Zhou, N. Identification of dust storm source areas in West Asia using multiple environmental datasets. Sci. Total Environ. 2015, 502, 224–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modarres, R.; Sadeghi, S. Spatial and temporal trends of dust storms across desert regions of Iran. Nat. Hazards 2018, 90, 101–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Yang, W.; Wang, X.; Yin, B.; Zhang, X.; Wang, J.; Gu, C.; Ming, J.; Geng, C.; Bai, Z. A seriously sand storm mixed air-polluted area in the margin of Tarim Basin: Temporal-spatial distribution and potential sources. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 676, 436–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Stein, A.F.; Draxler, R.R.; de la Rosa, J.D.; Zhang, X. Global sand and dust storms in 2008: Observation and HYSPLIT model verification. Atmos. Environ. 2011, 45, 6368–6381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.X. Mapping the global dust storm records: Review of dust data sources in supporting modeling/climate study. Curr. Pollut. Rep. 2015, 1, 82–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WMO Bulletin. WMO Bulletin Spotlights Hazards and Impacts of Sand and Dust Storms; Press Release; World Meteorological Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2024; Available online: https://public.wmo.int/news/media-centre/wmo-bulletin-spotlights-hazards-and-impacts-of-sand-and-dust-storms (accessed on 3 April 2025).

- Bao, C.; Yong, M.; Bueh, C.; Bao, Y.; Jin, E.; Bao, Y.; Purevjav, G. Analyses of the dust storm sources, affected areas, and moving paths in Mongolia and China in early spring. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 3661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, T.; Xi, G.; Hao, Y.; Chang, I.-S.; Wu, J.; Xue, Z.; Jin, E.; Zhang, W.; Bao, Y. The Transport Path and Vertical Structure of Dust Storms in East Asia and the Impacts on Cities in Northern China. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 3183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Notaro, M.; Alkolibi, F.; Fadda, E.; Bakhrjy, F. Trajectory analysis of Saudi Arabian dust storms. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2013, 118, 6028–6043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Hemoud, A.; Al-Dashti, H.; Al-Saleh, A.; Petrov, P.; Malek, M.; Elhamoud, E.; Al-Khafaji, S.; Li, J.; Koutrakis, P.; Doronzo, D. Dust storm ‘hot spots’ and transport pathways affecting the Arabian Peninsula. J. Atmos. Sol.-Terr. Phys. 2022, 238, 105932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Wang, W. Long-Range Transport of a Dust Event and Impact on Marine Chlorophyll-a Concentration in April 2023. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 1883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furman, H.K.H. Dust Storms in the Middle East: Sources of Origin and Their Temporal Characteristics. Indoor Built Environ. 2003, 12, 419–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keramat, A.; Marivani, B.; Samsami, M. Climatic change, drought and dust crisis in Iran. Int. J. Geol. Environ. Eng. 2011, 5, 472–475. [Google Scholar]

- Baghbanan, P.; Ghavidel, Y.; Farajzadeh, M. Temporal long-term variations in the occurrence of dust storm days in Iran. Meteorol. Atmos. Phys. 2020, 132, 885–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papi, R.; Kakroodi, A.; Soleimani, M.; Karami, L.; Amiri, F.; Alavipanah, S.K. Identifying sand and dust storm sources using spatial-temporal analysis of remote sensing data in Central Iran. Ecol. Inform. 2022, 70, 101724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javadnia, E.; Zahedi, N. Investigation impact of massive dust storm on aerosol optical, physical, radiative properties over Southwest Iran. Earth Obs. Geomat. Eng. 2022, 6, 135–149. [Google Scholar]

- Iraji, F.; Memarian, M.H.; Joghataei, M.; Malamiri, H.R.G. Determining the source of dust storms with use of coupling WRF and HYSPLIT models: A case study of Yazd province in central desert of Iran. Dyn. Atmos. Ocean. 2021, 93, 101197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseini Dehshiri, S.S.; Firoozabadi, B.; Afshin, H. A multidisciplinary approach to identify dust storm sources based on measurement of alternatives and ranking according to compromise solution (MARCOS): Case of Yazd in Iran. Nat. Hazards 2023, 116, 1663–1688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, K.; Trautmann, T.; Blaschke, T.; Subhan, F. Changes in aerosol optical properties due to dust storms in the Middle East and Southwest Asia. Remote Sens. Environ. 2014, 143, 216–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, Y.; Wu, Z.; Liao, K.; Ren, Y. Handling missing data in large-scale MODIS AOD products using a two-step model. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 3786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caido, N.G.; Ong, P.M.; Rempillo, O.; Galvez, M.C.; Vallar, E. Spatiotemporal analysis of MODIS aerosol optical depth data in the Philippines from 2010 to 2020. Atmosphere 2022, 13, 939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirgholami, M.; Masoodian, S.A. Assessment of spatial and temporal variations of land surface temperature (LST) due to elevation changes in Yazd Province, Iran. Arab. J. Geosci. 2022, 15, 1372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vancutsem, C.; Ceccato, P.; Dinku, T.; Connor, S.J. Evaluation of MODIS land surface temperature data to estimate air temperature in different ecosystems over Africa. Remote Sens. Environ. 2010, 114, 449–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, Z.; Wang, P.; Li, X. Using MODIS land surface temperature and normalized difference vegetation index products for monitoring drought in the southern Great Plains, USA. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2004, 25, 61–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, B.; Mao, K.; Cai, Y.; Shi, J.; Li, Z.; Qin, Z.; Meng, X.; Shen, X.; Guo, Z. A combined Terra and Aqua MODIS land surface temperature and meteorological station data product for China from 2003 to 2017. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2020, 12, 2555–2577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WMO. Manual on Codes—International Codes, Volume I.1, Annex II to the WMO Technical Regulations: Part A—Alphanumeric Codes; World Meteorological Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Baddock, M.C.; Strong, C.L.; Leys, J.; Heidenreich, S.; Tews, E.; McTainsh, G.H. A visibility and total suspended dust relationship. Atmos. Environ. 2014, 89, 329–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirgholami, M.R. Identifying trajectories and sources of dust events in Yazd Province using HYSPLIT model and remote sensing data. J. Arid Biome 2023, 13, 35–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Box, G.; Jenkins, G. Time Series Analysis: Forecasting and Control; Holden-Day: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Mann, H.B. Nonparametric tests against trend. Econometrica 1945, 13, 245–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kendall, M.G. Rank Correlation Methods; Griffin: London, UK, 1948. [Google Scholar]

- Ljung, G.M.; Box, G.E.P. On a measure of a lack of fit in time series models. Biometrika 1978, 65, 297–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Z.; Zhou, S.; Su, Q.; Yi, H.; Wang, J. Comparison study on the estimation of the spatial distribution of regional soil metal(loids) pollution based on kriging interpolation and BP neural network. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitas, L.; Mitasova, H. Spatial interpolation. In Geographical Information Systems: Principles, Techniques, Management and Applications; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1999; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Tewolde, M.G.; Beza, T.A.; Costa, A.C.; Painho, M. Comparison of different interpolation techniques to map temperature in the southern region of Eritrea. In Geospatial Thinking: Proceedings of the 13th AGILE International Conference on Geographic Information Science, Guimarães, Portugal, 11–14 May 2010; Painho, M., Santos, M.Y., Pundt, H., Eds.; Association of Geographic Information Laboratories for Europe: Warsaw, Poland, 2010; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Awadh, S.M. Impact of North African sand and dust storms on the Middle East using Iraq as an example: Causes, sources, and mitigation. Atmosphere 2023, 14, 180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khusfi, Z.; Vali, A.; Khosroshahi, M.; Ghazavi, R. The role of dried bed of Gavkhooni wetland on the production of the internal dust using remote sensing and storm roses (case study: Isfahan province). Iran. J. Range Desert Res. 2017, 24, 152–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansari, A.; Hedayati Aghmashhadi, A. Zoning Map of Dust Phenomenon in Markazi Province. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2018, 20, 17–27. [Google Scholar]

- Ebrahimikhusfi, Z.; Khosroshahi, M.; Naeimi, M.; Zandifar, S. Evaluating and monitoring of moisture variations in Meyghan wetland using the remote sensing technique and the relation to the meteorological drought indices. J. RS GIS Nat. Resour. 2019, 10, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Mirzaei, R.; Zareie, H.; Talaie, M. Impact assessment of Meighan wetland to create dust phenomenon in Arak city. J. Environ. Sci. Stud. 2021, 6, 3434–3440. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, S.; Jiang, N.; Huang, J.; Xu, X.; Zhang, H.; Zang, Z.; Huang, K.; Xu, X.; Wei, Y.; Guan, X.; et al. Quantifying contributions of natural and anthropogenic dust emission from different climatic regions. Atmos. Environ. 2018, 191, 94–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, H.; Fan, Y.; Luo, L.; Liao, J.; Li, Z.; Liu, X.; Liu, X.; Xue, X.; Wang, T. Identification of natural and anthropogenic sources and the effects of climatic fluctuations and land use changes on dust emissions variations in the Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2023, 340, 109628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boloorani, A.D.; Papi, R.; Soleimani, M.; Karami, L.; Amiri, F.; Samany, N.N. Water bodies changes in Tigris and Euphrates basin has impacted dust storms phenomena. Aeolian Res. 2021, 50, 100698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gholami, F.; Mesbahzadeh, T.; Zehtabian, G. Drought investigation using SPEI Index and its relationship with dust (Case Study of Khuzestan Province). Iran. J. Range Desert Res. 2021, 28, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zoljoodi, M.; Didevarasl, A.; Saadatabadi, A.R. Dust events in the western parts of Iran and the relationship with drought expansion over the dust-source areas in Iraq and Syria. Atmos. Clim. Sci. 2013, 3, 321–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).