Abstract

This study assessed the concentrations and spatial patterns of heavy metals in fine particulate matter with aerodynamic diameter below 2.5 m and coarse particulate matter with aerodynamic diameter below 10 m in Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic, during 2022. Thirty 24 h samples were collected using portable low-volume samplers across representative urban environments. Elemental concentrations of arsenic, cadmium, chromium, copper, iron, manganese, nickel, lead, vanadium, and zinc were quantified by energy-dispersive X-ray fluorescence. To address data below detection limits, regression on order statistics was applied. Copper and zinc exhibited the highest mean concentrations, pointing to strong anthropogenic inputs, while vanadium and iron showed pronounced spatial variability. Principal component analysis identified traffic and industrial activities as dominant sources. These findings provide baseline evidence for heavy metal pollution in Caribbean urban air and emphasize the need for continuous monitoring and effective regulatory strategies to mitigate potential health risks.

1. Introduction

Air pollution is a critical environmental and public health issue, particularly in urban areas where human activities release harmful pollutants [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15]. Among these, particulate matter (PM) is especially concerning for its ability to transport toxic substances such as heavy metals, originating from both natural sources (wildfires, volcanic activity, Saharan dust) and anthropogenic emissions (industry, traffic, combustion) [16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24].

Heavy metals, including both essential elements (e.g., Fe, Cu, Zn, Mn, Co, Ni) and non-essential ones (e.g., Cd, Pb, Hg, V, As), are commonly bound to respirable particulate fractions, PM2.5 and PM10, which can penetrate the respiratory system. At elevated concentrations these elements contribute to respiratory, cardiovascular, genotoxic, and cytotoxic effects [13,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35]. Beyond human health, they can also accumulate in soils and sediments, be absorbed by vegetation, and enter the food chain, with implications for biodiversity and ecosystem functions [36].

Urban areas in developing countries are particularly vulnerable, as rapid urbanization and industrialization often outpace environmental regulations [3,7,8,11,14,15,37,38]. The city of Santo Domingo, located in the National District of the Dominican Republic, exemplifies these challenges. Despite its diverse urban environments, limited research has investigated heavy metals in PM here [39,40,41,42].

This study addresses this gap by analyzing heavy metal concentrations in PM2.5 and PM10 from a 2022 sampling campaign in Santo Domingo. The objectives are (1) to quantify As, Cd, Cr, Cu, Fe, Hg, Mn, Ni, Pb, V, and Zn in PM fractions; (2) to assess imputation methods for left-censored values to characterize concentration variability; and (3) to identify potential sources and environmental implications of metal deposition across sampling sites. By providing baseline evidence, this research contributes to understanding air pollution dynamics in the Caribbean and supports policy actions to mitigate environmental and health risks.

Beyond filling a geographic knowledge gap, this study also provides a methodological contribution. We explicitly integrate regression on order statistics (ROS) to address left-censored observations together with principal component analysis (PCA) to explore multivariate associations among metals. While both techniques have been applied independently in air pollution research, their combined use remains uncommon, particularly in resource-limited contexts and in the Caribbean region where such analyses are virtually absent. This integration allows us to extract meaningful patterns from datasets with high proportions of values below detection limits, thereby strengthening the reliability of the source-apportionment results. By documenting both the baseline concentrations of heavy metals and the application of this analytical framework, the study contributes not only regional evidence but also a transferable approach for urban air quality investigations in other under-monitored areas.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area and Sampling Design

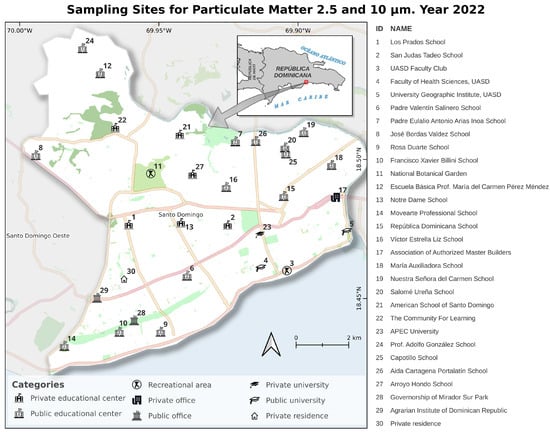

The study was carried out in Santo Domingo, National District, Dominican Republic (approx. 18.49° N, 69.96° W), covering a range of urban environments with different land uses (Figure 1). The sampling locations included public and private schools, a university campus, and a major urban park, following the initial site selection proposed by Caballero-González [40]. A total of 30 air quality samples were collected between May and July 2022 for both PM2.5 and PM10, with one sample per site due to logistical and budgetary constraints. At each location, the two particulate fractions were collected simultaneously using parallel MiniVolTM samplers (AirMetrics Co., Eugene, OR, USA), ensuring temporal comparability between PM2.5 and PM10. Although the measurements of PM mass concentrations (expressed in g/m3) are not presented in this study, they are available in the work of [43].

This single-day-per-site design, adopted for feasibility reasons, inherently restricts the ability to assess intra-site temporal variability or capture seasonal trends, but it offers a practical approach for characterizing the spatial distribution of particulate matter over a broad urban area. Single-day measurements, when distributed systematically across representative sites within a narrow temporal window (May to July), can still provide meaningful spatial comparisons, especially when meteorological conditions remain relatively stable throughout the sampling period [43]. Furthermore, by ensuring that sampling activities occurred on consecutive or near-consecutive days during each week, the resulting dataset supports the computation of time-averaged indicators and minimizes potential biases introduced by sporadic or asynchronous sampling. Although this approach does not replace long-term monitoring, it aligns with widely used methods in resource-constrained settings and has been shown to yield valuable insights into spatial pollution patterns across urban environments [43].

2.2. Sample Collection and Gravimetric Analysis

Particulate matter was collected using MiniVolTM Tactical Air Samplers (TAS, AirMetrics Co., Eugene, OR, USA) [44,45]. These samplers, developed in collaboration with the US EPA, operate at a constant flow to separate PM10 and PM2.5 fractions by inertial impaction. Sampling followed the USEPA 40 CFR Part 50 reference method and was approved by the Dominican Ministry of Environment [46]. PTFE (polytetrafluoroethylene) filters of 47 mm diameter were used, all from the same production lot to ensure consistency. Filters were conditioned in a controlled environment (15–30 °C; 20–45% relative humidity) for at least 24 h, weighed on a calibrated microbalance, and inspected for imperfections. They were handled exclusively with antistatic gloves and smooth-tip tweezers to prevent contamination. Each sampler was installed at 1.5–3 m above ground, operated for 24 h at a nominal flow of 5.0 L/min (), and verified against a reference manometer to check for leaks. After exposure, filters were desiccated again, reweighed under identical conditions, and stored in sealed containers (trip and equipment blanks included) to control for contamination. Gravimetric determinations followed this protocol, with typical uncertainty ranging from 5 to 10% [10,14].

2.3. Chemical Analysis (EDXRF)

Heavy metal concentrations in PM2.5 and PM10 were determined by energy-dispersive X-ray fluorescence spectrometry (EDXRF). Analyses were performed using a Skyray Instruments EDX 3600B spectrometer (Dallas, TX, USA) equipped with a Si(Li) detector positioned at a 45° angle relative to the Ag anode X-ray source. The excitation parameters were set at 40 kV and 600 A. Total concentrations of Fe, Mn, Cr, Cu, Ni, Zn, Pb, and As were quantified based on calibration curves obtained from certified Standard Reference Materials (SRMs). The quality of each calibration was assessed through the coefficient of determination (), which ranged from 0.990 to 0.999. Elemental intensities were processed using the proprietary Skyray Instruments software (Version RoHS4_1.1.47_110524_R, 2009, 20110524_R, Kunshan, China), provided by the manufacturer [47,48].

Although energy-dispersive X-ray fluorescence (EDXRF) has relatively high detection limits compared to more sensitive techniques such as ICP-MS, it was selected for this study due to several practical and scientific advantages. EDXRF is a non-destructive, cost-effective, and rapid analytical method that allows for the simultaneous quantification of multiple elements directly on filter media without the need for complex sample preparation. These features are particularly valuable in resource-constrained settings or large-scale environmental monitoring campaigns, where budget and time limitations must be balanced with data quality. Moreover, EDXRF provides sufficient accuracy and reproducibility for detecting moderate to high concentrations of metals commonly found in urban particulate matter. The dataset includes measurements of arsenic (As), cadmium (Cd), chromium (Cr), copper (Cu), iron (Fe), mercury (Hg), manganese (Mn), nickel (Ni), lead (Pb), vanadium (V), and zinc (Zn), with reported values in parts per million (ppm). Samples with metal concentrations below the instrument’s detection limit were treated as left-censored data. This limitation, which affected elements such as As, Mn, and Hg, was addressed through the application of robust statistical methods for censored data, enabling meaningful interpretation without compromising the integrity of the dataset.

The instrumental detection limits (IDLs) for each analyzed element are summarized in Table A3. For several metals (e.g., As, Mn, Hg, Fe, V), a substantial proportion of observations fell below the instrumental detection limits, resulting in left-censored data. This information was considered explicitly in the statistical treatment of the dataset to ensure transparency in data quality and to guide the interpretation of subsequent analyses.

2.4. Quality Assurance and Quality Control (QA/QC)

Quality assurance and quality control (QA/QC) procedures included pre- and post-sampling calibration of MiniVolTM units, verification of elapsed time using hour meters, and inspection of battery charge. Filters were transported in sterile, airtight bags, and desiccators with silica gel were used to maintain low humidity during conditioning and storage.

Quality control procedures for XRF analysis followed USEPA Method 6200 and ISO/IEC 17025 guidelines [49,50]. Each PTFE filter was divided into five analytical zones (four quadrants plus the center), which were scanned sequentially to account for possible inhomogeneous particle deposition. Elemental concentrations from these five zones were compared, and homogeneity was assessed by calculating the relative standard deviation (RSD). Filters with RSD values ≤ 20% were considered homogeneous and the mean value was reported; filters exceeding this threshold were flagged, re-analyzed, or reported with qualification. Instrument calibration was performed with certified thin-film standards (e.g., NIST SRMs), and performance was verified daily with check standards. Field and laboratory blanks were processed in parallel, and at least 10% of samples were re-analyzed to evaluate analytical precision. All procedures, from filter handling to data processing, were documented in compliance with ISO/IEC 17025 requirements.

2.5. Data Handling and Statistical Methods

All analyses were conducted using R statistical environment (Version 4.4.0; https://www.r-project.org/, accessed on 1 July 2024) [51], using a combination of packages, including tidyverse for data wrangling, gstat and automap for spatial interpolation of metal concentrations, NADA for censored data imputation, pcaMethods for PCA, and ggplot2 for visualization [52,53,54,55,56,57,58]. The complete workflow was implemented in an R Markdown document for reproducibility.

Initial data exploration included calculating summary statistics and correlation analyses among heavy metal concentrations in PM2.5 and PM10 (Table A1 and Table A2). However, due to a high proportion of left-censored values in several metals, correlation analyses were not used for further interpretation.

Summary statistics were computed before and after imputation to assess the central tendency and variability of metal concentrations. Metals with more than 50% left-censored values were excluded from the imputation process, following best practices in environmental data analysis [59].

To visualize the spatial distribution of heavy metals in PM2.5 and PM10, we applied geostatistical interpolation using ordinary kriging [60,61,62,63]. Only those metals with at least 50% valid observations were included in the analysis. The monitoring sites were converted into an sf object in R and reprojected to UTM Zone 19N (EPSG:32619) [64,65]. A regular interpolation grid was created with a resolution of 50 m, extending the bounding box of the monitoring points by 2 km to reduce edge effects.

The automap R package was used to automatically fit variogram models (spherical or exponential) based on the smallest residual sum of squares with respect to the sample variogram, and perform kriging for each metal independently [55,60,61,62,63]. To ensure the robustness of the kriging results, empirical semivariograms were fitted automatically and evaluated using spherical or exponential models depending on the best fit. For PM2.5, most metals were described by exponential models with ranges between ∼1.2 and 1.6 km (e.g., Cu: 1234 m; V: 1650 m; Pb: 1096 m), while As and Cd were fitted with spherical models of comparable ranges (1330–1380 m). Fe showed the largest spatial range (15.4 km), whereas Zn exhibited a very long modeled range (>80 km). For PM10, exponential models were again dominant, with ranges from ∼1.0 to 1.1 km for Pb and Cd, extending to >9 km for Cu, Cr, and Fe, and even >49 km for V. The variance explained by the models was consistent with low residual sum of squares on the order of to , supporting adequate fits across metals. Cross-validation further confirmed the models’ reliability, with predicted concentrations reproducing observed values without systematic bias. These results indicate that the interpolated maps capture meaningful spatial gradients while acknowledging higher uncertainty in areas distant from sampling sites.

Interpolated values were transformed into a raster and then used to generate filled contour levels and smoothed isolines. The individual maps for each metal were assembled into a single panel using the ggplot2 and patchwork R packages [66,67]. The shaded polygon in the background of each map represents the official administrative boundary of the National District of Santo Domingo. It is important to acknowledge that the spatial resolution of this study is limited by the relatively small number of monitoring sites (30 across the National District) and by the single 24 h measurement at each site. This low sampling density increases the uncertainty of geostatistical interpolation, particularly in peripheral areas that are more distant from sampling locations. Moreover, the kriging maps derived from these data should be interpreted as exploratory visualizations rather than definitive representations of long-term spatial distributions. The approach provides a first-order overview of possible concentration gradients across the city but cannot substitute for denser or long-term monitoring networks. While the systematic layout of sites reduces some bias by ensuring coverage across diverse land-use settings, the resulting maps are best viewed as hypothesis-generating tools that highlight where future high-frequency or extended campaigns should be prioritized.

The instrumental detection limits (IDLs) for heavy metals in PM2.5 and PM10 were determined following established protocols for X-ray fluorescence spectrometry [49,68] as well as using empirical laboratory measurements. The IDLs were derived from multiple measurements of certified reference materials (CRMs), specifically SRM-NIST-IAEA samples, analyzed under the same conditions as the field samples. The detection limit for each metal was established based on the lowest concentration that could be reliably distinguished from background noise, considering the variability across multiple replicates [69]. The IDL values for elements such as As, Cd, Cr, Cu, Fe, Mn, Ni, Pb, V and Zn were compiled in an accompanying reference table (see Table A3), ensuring consistency in the reporting of metal concentrations [70,71]. Values below these detection limits were treated as left-censored and were subsequently handled using statistical imputation methods where appropriate [59].

For metals with less than 50% of measurements below detection limits, imputation was performed using regression on order statistics (ROS) implemented in the NADA package in the R statistical environment [57]. The ROS method estimates censored values based on the empirical distribution of detected values, providing a statistically sound approach for handling non-detects while avoiding strong parametric assumptions [59].

Importantly, imputed values were only used for global descriptive statistics and not for multivariate analyses, such as principal component analysis (PCA), where preserving the original data structure was required. For the PCA, left-censored values were explicitly coded as missing and handled directly by the NIPALS algorithm, which estimates principal components without the need for imputation or listwise deletion. PCA was applied separately to PM2.5 and PM10 metal concentrations to explore their distribution across sampling sites and identify potential sources. Only metals with sufficient observations (i.e., limited missing values) were included in the PCA, while elements such as mercury (Hg) and manganese (Mn), with more than 50% censored values, were excluded entirely. The final selection of metals for PCA was therefore based on the presence of complete cases across sites, ensuring the robustness of the analysis. The PCA was performed using the pca function from the pcaMethods package in R, employing the non-linear iterative partial least squares (NIPALS) algorithm [72,73]. This method is particularly suitable for datasets with missing values, as it iteratively estimates principal components while handling incomplete data without requiring listwise deletion. The input dataset was standardized (mean-centered and scaled to unit variance) before PCA computation.

The results were visualized using biplots to examine the relationships between metals and sampling sites. The biplots were generated using ggplot2, with individual observations plotted in the principal component space and metal loadings represented as vectors scaled for interpretability. The explained variance of each principal component was assessed to determine the number of meaningful components. Given the limited number of samples (), the PCA results should be interpreted as exploratory rather than confirmatory. While sample size constraints limit the robustness of the multivariate model, the PCA provided a useful descriptive tool to visualize co-variation among metals and sampling sites [74].

Although detailed external datasets such as traffic counts or land-use inventories were not available for integration in this study, the interpretation of principal components was informed by established metal source profiles and contextual knowledge of the urban environment. Metals such as Cu, Zn, and Pb, which loaded heavily on the first component, are commonly associated with vehicular emissions and mechanical wear, while Fe and V suggest contributions from industrial activities or resuspended soil. Future research will aim to incorporate high-resolution auxiliary data, including traffic density, industrial zoning, and meteorological parameters, to further refine source attribution and strengthen causal inferences.

While the toxicological relevance of heavy metals in particulate matter is well established, this study did not include a formal health risk assessment or estimates of population exposure due to the unavailability of local epidemiological and health outcome data. Our primary objective was to establish a baseline of metal concentrations across urban sites, which is a necessary first step toward future risk-based evaluations. The spatial patterns and concentration levels reported here can serve as input for subsequent studies focused on health impact modeling, particularly those incorporating population vulnerability, exposure duration, and toxicological benchmarks. We recognize the importance of such analyses and recommend them as a critical next step in advancing air quality management in the region.

3. Results

After applying regression on order statistics (ROS) to impute left-censored values, descriptive statistics for metal concentrations in PM2.5 were obtained. Manganese (Mn) and mercury (Hg) were excluded from the imputation process since more than 50% of their values were censored, making reliable estimation unfeasible. The results indicate substantial variability among metals, with mean concentrations ranging from 2.5 ppm for As to 22 ppm for Cu (Table 1). Among the analyzed elements, Cu and Zn exhibited the highest median values (22 ppm and 19.8 ppm, respectively), whereas As and Cd had the lowest medians (2.4 ppm and 2.5 ppm, respectively). The standard deviation values reveal notable dispersion, particularly for V (9.2 ppm) and Fe (6.1 ppm), indicating significant variability across the sampling sites. Additionally, the standard error values, which provide an estimate of uncertainty in the mean concentrations, were lowest for Zn (0.16 ppm) and highest for V (1.7 ppm), suggesting more stable concentration estimates for Zn compared to highly variable metals like V.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics of metal concentrations in PM2.5 (ppm) collected in Santo Domingo during 2022. Values were estimated after imputing censored data using regression on order statistics.

The proportion of censored values varied across metals, with the highest number observed for V (15 censored values) and Fe (14 censored values), while Cu and Zn had no censored values. This suggests that certain metals frequently fell below the instrumental detection limits, requiring imputation to obtain meaningful statistical summaries. The highest recorded metal concentration was 37 ppm for V, while the lowest detected value was 0.6 ppm for Cd. Table 1 summarizes the mean concentrations along with their standard errors, highlighting the metals with greater measurement uncertainty. The error bars emphasize the variation in concentration levels across sites, with Fe and V showing the most considerable spread, reinforcing their observed variability in the dataset.

The analysis of metal concentrations in PM10 revealed differences in both the magnitude and variability of detected levels. Copper (Cu) and zinc (Zn) exhibited the highest mean concentrations, with values of 21 ppm and 20 ppm, respectively, while cadmium (Cd) and chromium (Cr) showed the lowest means at 3.8 ppm and 3.9 ppm. Vanadium (V), despite having a relatively moderate mean concentration (8.6 ppm), displayed the highest observed value among all metals (44 ppm), suggesting a highly skewed distribution. Similarly, iron (Fe) exhibited substantial variability, with concentrations ranging from 3.4 ppm to 28 ppm. It is important to note that manganese (Mn), mercury (Hg), and arsenic (As) were excluded from imputation due to excessive censoring, as more than 50% of their values were below detection limits, making statistical estimation unreliable. The variability in concentrations is further illustrated in Table 2.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics of metal concentrations in PM10 (ppm) collected in Santo Domingo during 2022. Values were estimated after imputing censored data using regression on order statistics.

When considering the uncertainty associated with these estimations, the standard error values indicate that Zn had the most stable concentration estimates (0.13 ppm), whereas V had the highest level of uncertainty (1.9 ppm), reflecting its large dispersion. The extent of censored values also varied significantly among metals, with Fe (19 censored values) and V (16 censored values) being the most affected. In contrast, Cu, Zn, and Ni had no censored values, implying that their concentrations consistently exceeded the detection limits. Table 2 highlights the differences in concentration variability across metals, emphasizing the higher dispersion in V and Fe, which suggests spatial heterogeneity in their deposition patterns.

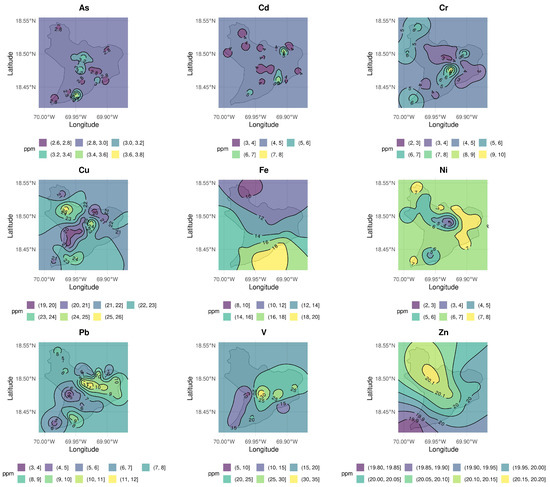

The spatial interpolation of metal concentrations in PM2.5 (Figure 2) provides an overview of how values vary across the National District. The panels show nine individual maps, one for each analyzed element (As, Cd, Cr, Cu, Fe, Ni, Pb, V, Zn). The contour lines and color shading represent the estimated concentration gradients, where darker or lighter tones indicate relatively lower or higher values, respectively. For As and Cd, the concentration ranges are narrow and localized, with only a few zones showing values above the general background. Cr and Ni display moderate variability, with clear differences between central and peripheral parts of the study area. Cu and Zn exhibit higher and more consistent concentrations across multiple sites, with smooth transitions between levels. Fe shows wider spatial dispersion, with values extending across both northern and southern areas of the district. Pb and V present more marked contrasts, with localized areas of elevated concentrations surrounded by lower values. Overall, the PM2.5 maps illustrate a combination of localized hotspots and gradual gradients, reflecting heterogeneity in the measured concentrations across the 30 sampling points.

Figure 2.

Spatial distribution of metal concentrations in PM2.5 (ppm) across the National District of Santo Domingo (2022). Ordinary kriging interpolation was applied to the 30 sampling sites. Each panel corresponds to one metal.

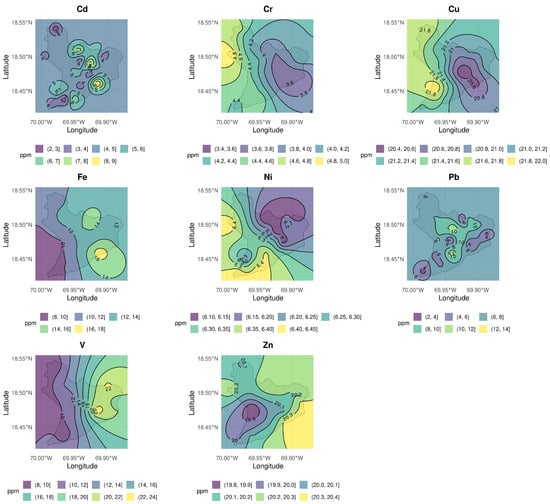

The corresponding spatial interpolation for PM10 (Figure 3) summarizes the distribution of eight metals (Cd, Cr, Cu, Fe, Ni, Pb, V, Zn) across the same 30 sampling sites. As in the case of PM2.5, each panel represents a single element, with filled contours and isolines indicating estimated concentration ranges. Cd and Cr show relatively low concentration ranges, with localized clusters of higher values surrounded by zones of lower intensity. Cu and Zn display higher concentrations overall, with broad areas of elevated values that extend across much of the district. Fe shows a wide range of variability, with large gradients between the lowest and highest concentrations. Ni and Pb exhibit intermediate ranges, with clusters of moderate values interspersed across the area. V presents the greatest variability among the PM10 metals, with a steep gradient from low to very high concentrations over short distances. Taken together, these maps show that the coarse fraction is characterized by a wider range of values and sharper contrasts between sites compared to the fine fraction, while still maintaining distinct patterns for each individual element.

Figure 3.

Spatial distribution of metal concentrations in PM10 (ppm) across the National District of Santo Domingo (2022). Ordinary kriging interpolation was applied to the 30 sampling sites. Each panel corresponds to one metal.

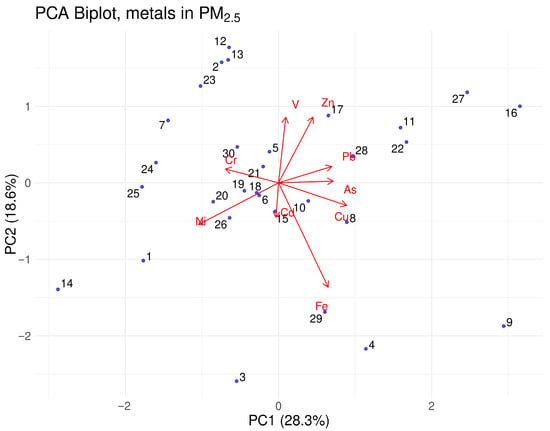

The principal component analysis (PCA) for metal concentrations in PM2.5 (Figure 4) reveals the distribution of sampling sites along the first two principal components, which together explain a substantial proportion of the variance in the dataset. The first component (PC1) accounts for 28.3% of the variance, while the second component (PC2) explains 18.6%. Sampling sites such as the Agrarian Institute of Dominican Republic (29), APEC University (23), and San Judas Tadeo School (2) are positioned at the extremes along PC1, whereas sites like the American School of Santo Domingo (21), Victor Estrella Liz School (16), and Prof. Adolfo González School (24) are located towards the center. The loading plot shows that metals such as Zn, V, and Pb contribute strongly to the first component, while Fe and Cr have a more substantial influence along the second component.

Figure 4.

Principal component analysis (PCA) biplot of metal concentrations in PM2.5 (2022). The first two components explain 28.3% and 18.6% of the variance. Blue points represent sampling sites (numbered as in Figure 1); red vectors indicate metal loadings.

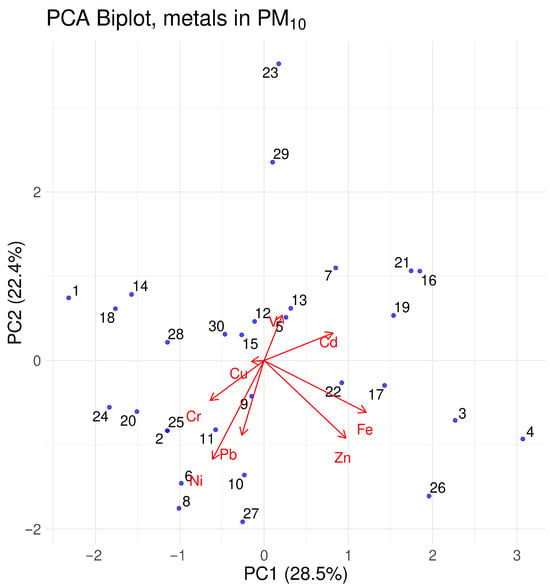

In the case of PM10 (Figure 5), the first two principal components explain 28.5% and 22.4% of the variance, respectively. The PCA plot reveals a clustering pattern where sites such as Aida Cartagena Portalatín School (26) and The Community for Learning (22) are positioned towards the positive extremes of PC1, while Los Prados School (1), María Auxiliadora School (18), and Notre Dame School (13) are situated towards the negative end. The loading vectors indicate that Zn, V, and Fe show a strong correlation with PC1, whereas Pb, Cr, and Ni have more influence along PC2. Compared to PM2.5, the PCA for PM10 shows a slightly different spatial distribution of sites, suggesting variations in the metal concentration patterns.

Figure 5.

Principal component analysis (PCA) biplot of metal concentrations in PM10 (2022). The first two components explain 28.5% and 22.4% of the variance. Blue points represent sampling sites (numbered as in Figure 1); red vectors indicate metal loadings.

Across both analyses, certain sites exhibit distinct positions within the PCA space, indicating differences in their metal concentration profiles. For instance, Capotillo School (25) and Arroyo Hondo School (27) appear centrally located in both analyses, while Salomé Ureña School (20) and República Dominicana School (15) occupy different relative positions between PM2.5 and PM10. The biplots further illustrate the contribution of individual metals, where V, Cr, and Pb consistently appear as key contributors to the variability in both fractions. The separation among sites along PC1 and PC2 suggests underlying differences in metal distributions across urban environments.

4. Discussion

This study aimed to (1) quantify the concentrations of selected heavy metals in PM2.5 and PM10 in Santo Domingo, (2) apply statistical imputation techniques to handle left-censored data, and (3) explore the spatial distribution and potential sources of these metals through principal component analysis. These objectives have been met successfully: the analysis provided detailed concentration profiles for nine metals, robustly addressed censoring through ROS, and identified spatial variability and possible emission sources using PCA. The study contributes new baseline data on airborne metal pollution in the capital city of the Dominican Republic, a context where environmental monitoring efforts remain limited [43]. The findings provide a foundation for both regulatory interventions and future scientific research.

The high concentrations of Cu and Zn across both PM fractions suggest dominant and persistent anthropogenic sources, possibly related to vehicular traffic, brake and tire wear, and mechanical workshops [75,76]. These metals are commonly found in urban PM worldwide and their consistent detection in all sites supports their ubiquity in the city’s atmosphere [77,78]. The presence of Pb and Ni, although at moderate levels, remains concerning due to their toxicity and potential for chronic exposure. Leaded gasoline was phased out in the region decades ago, but legacy pollution from past vehicular emissions and industrial activity may still influence current concentrations [79,80,81].

Vanadium (V) and iron (Fe) exhibited high variability, particularly in PM10, suggesting heterogeneous sources or resuspension processes [82,83]. V is often associated with the combustion of heavy fuels, such as bunker oil used in marine transport and some electricity generation facilities [84,85]. The elevated standard errors and extreme values observed for V may reflect occasional long-range transport or local emission peaks. Similarly, the broad concentration range of Fe may indicate contributions from soil resuspension, construction activities, or industrial dust [82,86].

When contextualizing these concentrations, it is important to compare them with reports from other cities in the Caribbean and Latin America. Studies conducted in urban centers in the region have documented comparable patterns, with Cu and Zn frequently appearing among the dominant metals in both PM2.5 and PM10 [87,88,89]. Reported concentrations of Pb and Ni in several Latin American capitals are generally in the same order of magnitude as those observed here, while Fe and V often display higher variability due to local industrial and combustion sources. The levels detected in Santo Domingo therefore appear broadly consistent with those documented elsewhere in the region, although direct comparisons must be made cautiously given differences in sampling design, analytical techniques, and periods of observation. This regional comparison highlights that the metal concentrations in Santo Domingo are neither unusually high nor negligible, but rather fall within the range of urban exposures observed in other resource-limited settings.

The PCA results revealed patterns of co-occurrence among metals, allowing for tentative source attribution. In PM2.5, PC1 (28%) loads positively on As–Cu–Pb and negatively on Ni–Cr, while PC2 (19%) is dominated by V and Zn on the positive side and opposed by Fe on the negative side (Figure 4). The Cu and Zn signals are consistent with non-exhaust traffic emissions (brake and tire wear) [90], whereas V typically traces residual-oil/industrial combustion and Fe is compatible with crustal/resuspension inputs [24,91]. The negative PC1 loadings of Ni and Cr point to a contribution distinct from the Cu/Zn traffic signature, in line with industrial/metallurgical or resuspended material [91]. Pb on the positive side of PC1 may reflect legacy vehicular emissions and/or industrial residues [91].

In PM10, PC1 (29%) aligns with Zn–Fe–V–Cd on the positive side and with Pb–Ni–Cr on the negative side, whereas PC2 (22%) further separates Cd and V (positive) from Ni/Pb/Cr (negative) (Figure 5). The co-variation of Zn and Fe with PC1 suggests a mixture of non-exhaust traffic and resuspension, with V again indicating oil/industrial combustion [24,90,91]. The opposite signs of V and Ni here imply that heavy-oil markers are not co-emitted uniformly across sites, pointing to spatially heterogeneous combustion sources. Overall, the patterns agree with urban source-apportionment literature in which traffic (exhaust and non-exhaust), industrial/combustion, and resuspended dust are the dominant contributors to particulate metals [85,86,91].

In several cases, the measured concentrations of specific metals in PM2.5 appeared higher than those in PM10 [92,93]. These apparent exceedances can arise from both methodological and environmental factors. On the methodological side, parallel MiniVolTM samplers may introduce slight differences in airflow or particle separation efficiency under variable field conditions. The relatively small sampled air volume (∼7 m3 per filter) increases measurement uncertainty near detection limits, and the imputation of censored values can accentuate variability when a large fraction of observations fall below instrumental thresholds [94]. At the same time, evidence from multiple regions shows that anthropogenic metals can indeed be enriched in the fine fraction. For instance, higher PM2.5/PM10 ratios of toxic elements have been reported at urban sites in Italy [95] and in Hefei, China [93]. Moreover, toxicological studies confirm that metals in PM2.5 are not only more concentrated but also more bioaccessible than in PM10, highlighting the greater health relevance of this fraction. Taken together, these methodological uncertainties and documented enrichment patterns suggest that instances of higher PM2.5 concentrations should be interpreted cautiously, acknowledging both potential artifacts and genuine fine-fraction predominance.

Previous studies have also documented instances where certain elemental concentrations in PM2.5 appeared higher than in PM10, particularly under low-volume sampling conditions. Such anomalies have been attributed to a combination of analytical uncertainty near detection limits, limited sample mass, and the preferential enrichment of anthropogenic metals in the fine mode [94]. These findings underscore that the apparent exceedances observed in our dataset should be interpreted with caution, as they likely reflect methodological artifacts rather than true physical differences in particle composition. Consequently, we emphasize that the results presented here serve as preliminary evidence of spatial patterns, not definitive estimates of absolute concentrations.

This study also has important limitations that must be acknowledged. First, the sampling strategy was constrained to 30 sites with a single 24 h measurement each, which restricts both spatial density and temporal representativeness. The kriging maps, while useful for exploring possible gradients, should be interpreted as first-order approximations rather than definitive spatial patterns. Second, the reliance on one short campaign prevents evaluation of seasonal or diurnal variability, meaning that the observed distribution cannot be assumed to represent long-term averages. Third, several metals (e.g., Mn, Hg, and As in PM10) were excluded from multivariate analysis due to excessive censoring. The absence of mercury and manganese, in particular, represents a significant limitation, as these toxic elements are known to contribute to adverse health effects and their exclusion reduces the completeness of the source attribution [24]. Finally, while EDXRF was chosen for its cost-effectiveness and feasibility in resource-constrained contexts, its relatively high detection limits compared to ICP-MS may have led to underestimation of certain trace elements [70,96]. In addition, the principal component analysis explained less than 50% of the total variance for PM2.5, which means that a substantial proportion of variability remained unexplained; consequently, the identified source patterns should be regarded as preliminary hypotheses rather than definitive conclusions. Together, these limitations emphasize that the present results should be seen as a baseline and a hypothesis-generating effort, underscoring the need for denser and longer-term monitoring campaigns in the future.

These results prompt several new research questions. Future studies should investigate seasonal and diurnal patterns in metal concentrations, assess deposition rates to soil and vegetation, and explore health outcomes associated with chronic exposure in children and sensitive populations. Integrating land-use regression (LUR) models or chemical mass balance (CMB) models would help refine source attribution [97,98]. Moreover, monitoring metals not captured in this study, including those associated with electronic waste and emerging contaminants, could yield insights into evolving pollution sources in urban contexts.

5. Conclusions

This work provides a foundational assessment of heavy metals in atmospheric particulate matter in Santo Domingo. It reveals the presence of persistent pollutants, spatial heterogeneity in exposure, and key indicators of anthropogenic activity. The study underscores the need for expanded air quality monitoring and targeted mitigation strategies to protect public health and environmental quality in the region.

Author Contributions

C.M.-E.: designed and conducted the field experiments, developed the methodology, managed the project administration, secured the resources, analyzed the data, interpreted the results, contributed to the writing, review, and editing of the manuscript; R.D.: assisted with the measurements; A.H.-G. and U.J.-H.: reviewed and provided feedback on the manuscript; J.-R.M.-B.: analyzed the data, interpreted the results, and contributed to the writing, review, and editing of the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors acknowledge the Ministry of Higher Education, Science, and Technology of the Dominican Republic, specifically its National Fund for Scientific Innovation and Technological Development, for funding this research under the project “Air pollution by heavy metals and radionuclides in atmospheric aerosols from urban areas: Contribution to air quality management in the Distrito Nacional”, Fondo Nacional de Innovación y Desarrollo Científico–Tecnológico (CROSSREF funder ID 100016968), grant code No. 2020-2021-2B1-110.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

This work was carried out within the Doctoral Program in Environmental Sciences of the Basic and Environmental Sciences Area at the Technological Institute of Santo Domingo (INTEC). The authors also express their gratitude to the Science Faculty and the Physics Institute of the Autonomous University of Santo Domingo (UASD) for their support. Special thanks are extended to José Antonio Peña and Albert Santiago de la Cruz for their valuable contribution to field sampling and logistics.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| As | Arsenic |

| Cd | Cadmium |

| Cr | Chromium |

| Cu | Copper |

| Fe | Iron |

| Hg | Mercury |

| Mn | Manganese |

| Ni | Nickel |

| Pb | Lead |

| PM | Particulate matter |

| PM10 | Particles with a diameter less than 10 m |

| PM2.5 | Particles with a diameter less than 2.5 m |

| V | Vanadium |

| XRF | X-ray fluorescence |

| Zn | Zinc |

Appendix A

Estimated Concentrations of Metals by X-Ray Fluorescence Spectrometry in PM2.5 and PM10, Including All Metals at All Sampling Sites, Regardless of Whether Values Were Left-Censored (e.g., Below the Calibrated Detection Limits) or Below the Instrument’s Detection Limit.

Table A1.

Estimated concentrations of metals (units in ppm) in PM2.5.

Table A1.

Estimated concentrations of metals (units in ppm) in PM2.5.

| Site ID | Name | As | Cd | Cr | Cu | Fe | Hg | Mn | Ni | Pb | V | Zn | Latitude | Longitude |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Los Prados School | 2.8 | 5.4 | 4.4 | 19.0 | 12.8 | 2.1 | 7.0 | 2.9 | 6.9 | 19.7 | 18.48 | −69.96 | |

| 2 | San Judas Tadeo School | 2.4 | 2.5 | 10.2 | 23.2 | 10.5 | 6.5 | 23.8 | 21.6 | 18.48 | −69.93 | |||

| 3 | UASD Faculty Club | 2.0 | 3.5 | 23.1 | 24.5 | 2.2 | 3.5 | 8.0 | 11.8 | 18.9 | 18.46 | −69.90 | ||

| 4 | Faculty of Health Sciences, UASD | 3.5 | 9.4 | 2.6 | 22.2 | 26.7 | 6.9 | 6.0 | 13.1 | 21.0 | 18.46 | −69.91 | ||

| 5 | University Geographic Institute, UASD | 3.2 | 2.8 | 20.7 | 7.5 | 2.3 | 4.0 | 6.0 | 9.9 | 18.8 | 19.0 | 18.47 | −69.88 | |

| 6 | Padre Valentín Salinero School | 2.4 | 3.3 | 6.1 | 23.2 | 17.6 | 6.8 | 5.5 | 20.9 | 18.46 | −69.94 | |||

| 7 | Padre Eulalio Antonio Arias Inoa School | 2.9 | 3.9 | 19.2 | 5.0 | 6.8 | 5.8 | 19.8 | 18.51 | −69.92 | ||||

| 8 | José Bordas Valdez School | 2.9 | 2.5 | 6.4 | 23.0 | 22.1 | 5.2 | 18.3 | 20.2 | 18.50 | −69.99 | |||

| 9 | Rosa Duarte School | 4.9 | 3.5 | 24.5 | 28.0 | 2.5 | 5.4 | 9.7 | 19.2 | 18.44 | −69.95 | |||

| 10 | Francisco Xavier Billini School | 2.8 | 23.9 | 15.8 | 6.2 | 20.4 | 18.44 | −69.96 | ||||||

| 11 | National Botanical Garden | 3.3 | 3.5 | 23.4 | 13.8 | 4.6 | 7.0 | 21.1 | 18.49 | −69.95 | ||||

| 12 | Escuela Básica Prof. María del Carmen Pérez Méndez | 2.5 | 20.1 | 4.0 | 5.7 | 6.7 | 20.6 | 18.53 | −69.97 | |||||

| 13 | Notre Dame School | 4.0 | 2.2 | 4.5 | 19.2 | 8.0 | 6.4 | 5.8 | 36.9 | 19.5 | 18.48 | −69.94 | ||

| 14 | Movearte Professional School | 2.1 | 4.9 | 7.3 | 20.4 | 11.0 | 7.4 | 3.7 | 12.1 | 17.9 | 18.43 | −69.98 | ||

| 15 | República Dominicana School | 3.1 | 20.9 | 14.6 | 7.4 | 11.3 | 24.0 | 19.2 | 18.49 | −69.91 | ||||

| 16 | Víctor Estrella Liz School | 3.2 | 2.4 | 25.6 | 9.5 | 3.8 | 2.4 | 12.2 | 22.3 | 19.5 | 18.49 | −69.93 | ||

| 17 | Association of Authorized Master Builders | 4.4 | 23.1 | 15.0 | 7.6 | 9.5 | 27.0 | 22.0 | 18.49 | −69.89 | ||||

| 18 | María Auxiliadora School | 5.0 | 3.9 | 21.8 | 10.8 | 7.6 | 10.6 | 19.6 | 18.50 | −69.89 | ||||

| 19 | Nuestra Señora del Carmen School | 2.6 | 2.1 | 4.0 | 21.8 | 13.3 | 4.2 | 6.2 | 5.4 | 19.5 | 18.51 | −69.90 | ||

| 20 | Salomé Ureña School | 2.6 | 10.0 | 5.4 | 22.5 | 8.5 | 4.3 | 3.0 | 7.1 | 22.6 | 19.6 | 18.50 | −69.90 | |

| 21 | American School of Santo Domingo | 3.1 | 23.8 | 11.2 | 7.2 | 5.5 | 20.5 | 18.51 | −69.94 | |||||

| 22 | The Community For Learning | 2.7 | 3.7 | 26.2 | 12.3 | 5.5 | 8.5 | 20.7 | 18.51 | −69.97 | ||||

| 23 | APEC University | 2.3 | 6.3 | 21.1 | 6.5 | 7.2 | 30.6 | 20.5 | 18.47 | −69.91 | ||||

| 24 | Prof. Adolfo González School | 2.4 | 6.9 | 21.2 | 8.8 | 2.7 | 7.8 | 8.6 | 19.8 | 18.54 | −69.98 | |||

| 25 | Capotillo School | 7.9 | 19.5 | 13.0 | 7.5 | 6.9 | 19.8 | 18.50 | −69.90 | |||||

| 26 | Aida Cartagena Portalatín School | 3.7 | 3.8 | 19.6 | 14.3 | 7.8 | 11.4 | 19.2 | 18.51 | −69.92 | ||||

| 27 | Arroyo Hondo School | 4.1 | 3.6 | 2.6 | 19.9 | 16.2 | 4.5 | 3.8 | 11.9 | 21.2 | 18.49 | −69.94 | ||

| 28 | Governorship of Mirador Sur Park | 2.4 | 6.6 | 22.3 | 13.9 | 2.5 | 4.4 | 10.0 | 20.7 | 20.3 | 18.44 | −69.96 | ||

| 29 | Agrarian Institute of Dominican Republic | 3.7 | 23.2 | 20.7 | 6.4 | 12.2 | 19.3 | 18.45 | −69.97 | |||||

| 30 | Private residence | 2.8 | 3.5 | 19.1 | 12.3 | 6.7 | 20.6 | 18.46 | −69.96 |

Table A2.

Estimated concentrations of metals (units in ppm) in PM10.

Table A2.

Estimated concentrations of metals (units in ppm) in PM10.

| Site ID | Name | As | Cd | Cr | Cu | Fe | Hg | Mn | Ni | Pb | V | Zn | Latitude | Longitude |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Los Prados School | 4.3 | 20.6 | 6.0 | 2.7 | 7.1 | 8.4 | 18.2 | 18.48 | −69.96 | ||||

| 2 | San Judas Tadeo School | 3.2 | 3.5 | 15.5 | 8.0 | 2.9 | 7.4 | 11.2 | 19.9 | 18.48 | −69.93 | |||

| 3 | UASD Faculty Club | 6.7 | 2.8 | 16.5 | 21.4 | 4.1 | 6.7 | 20.3 | 21.1 | 18.46 | −69.90 | |||

| 4 | Faculty of Health Sciences, UASD | 3.5 | 9.4 | 2.6 | 22.2 | 26.7 | 6.9 | 6.0 | 13.1 | 21.0 | 18.46 | −69.91 | ||

| 5 | University Geographic Institute, UASD | 4.6 | 2.4 | 21.2 | 10.0 | 6.2 | 7.1 | 22.6 | 20.3 | 18.47 | −69.88 | |||

| 6 | Padre Valentín Salinero School | 3.3 | 3.7 | 23.1 | 13.8 | 7.6 | 12.9 | 19.8 | 18.46 | −69.94 | ||||

| 7 | Padre Eulalio Antonio Arias Inoa School | 2.8 | 2.3 | 19.6 | 12.6 | 6.6 | 5.9 | 2.8 | 20.3 | 18.51 | −69.92 | |||

| 8 | José Bordas Valdez School | 3.2 | 7.1 | 22.1 | 9.1 | 7.4 | 21.1 | 18.50 | −69.99 | |||||

| 9 | Rosa Duarte School | 6.9 | 6.8 | 18.4 | 9.5 | 2.2 | 6.4 | 6.7 | 20.6 | 18.44 | −69.95 | |||

| 10 | Francisco Xavier Billini School | 2.2 | 4.7 | 21.9 | 12.8 | 6.5 | 8.1 | 5.7 | 21.0 | 18.44 | −69.96 | |||

| 11 | National Botanical Garden | 5.3 | 24.3 | 10.2 | 2.1 | 6.1 | 9.7 | 4.2 | 20.4 | 18.49 | −69.95 | |||

| 12 | Escuela Básica Prof. María del Carmen Pérez Méndez | 2.6 | 21.4 | 8.8 | 7.0 | 6.5 | 6.3 | 20.1 | 18.53 | −69.97 | ||||

| 13 | Notre Dame School | 2.8 | 5.4 | 3.3 | 19.3 | 12.7 | 6.4 | 2.8 | 6.9 | 20.0 | 18.48 | −69.94 | ||

| 14 | Movearte Professional School | 2.9 | 3.5 | 19.2 | 4.1 | 7.5 | 2.2 | 13.9 | 19.6 | 18.43 | −69.98 | |||

| 15 | República Dominicana School | 19.6 | 11.4 | 6.1 | 19.8 | 18.49 | −69.91 | |||||||

| 16 | Víctor Estrella Liz School | 2.6 | 8.9 | 2.1 | 20.5 | 14.8 | 4.6 | 9.6 | 20.2 | 18.49 | −69.93 | |||

| 17 | Association of Authorized Master Builders | 2.3 | 24.1 | 18.7 | 6.2 | 2.5 | 7.4 | 21.2 | 18.49 | −69.89 | ||||

| 18 | María Auxiliadora School | 2.8 | 4.9 | 6.2 | 21.3 | 5.8 | 3.0 | 6.0 | 7.9 | 19.2 | 18.50 | −69.89 | ||

| 19 | Nuestra Señora del Carmen School | 4.9 | 4.0 | 4.1 | 20.9 | 16.9 | 3.9 | 4.6 | 6.4 | 31.6 | 21.0 | 18.51 | −69.90 | |

| 20 | Salomé Ureña School | 2.4 | 4.2 | 25.5 | 6.1 | 7.6 | 8.4 | 19.9 | 18.50 | −69.90 | ||||

| 21 | American School of Santo Domingo | 7.8 | 2.7 | 19.2 | 13.2 | 4.6 | 13.9 | 20.6 | 18.51 | −69.94 | ||||

| 22 | The Community For Learning | 3.1 | 20.0 | 18.9 | 2.2 | 6.3 | 8.2 | 16.9 | 20.2 | 18.51 | −69.97 | |||

| 23 | APEC University | 4.2 | 21.6 | 11.4 | 2.1 | 3.6 | 3.3 | 43.6 | 18.9 | 18.47 | −69.91 | |||

| 24 | Prof. Adolfo González School | 3.6 | 2.0 | 6.6 | 24.1 | 10.9 | 6.1 | 8.3 | 3.1 | 19.6 | 18.54 | −69.98 | ||

| 25 | Capotillo School | 3.2 | 3.5 | 15.5 | 8.0 | 2.9 | 7.4 | 11.2 | 19.9 | 18.50 | −69.90 | |||

| 26 | Aida Cartagena Portalatín School | 5.7 | 5.3 | 23.3 | 28.4 | 6.1 | 9.2 | 20.9 | 18.51 | −69.92 | ||||

| 27 | Arroyo Hondo School | 3.5 | 5.3 | 20.4 | 17.5 | 7.1 | 12.9 | 18.3 | 20.4 | 18.49 | −69.94 | |||

| 28 | Governorship of Mirador Sur Park | 3.8 | 23.9 | 8.3 | 5.8 | 7.3 | 4.6 | 6.0 | 19.5 | 18.44 | −69.96 | |||

| 29 | Agrarian Institute of Dominican Republic | 2.1 | 6.3 | 4.2 | 23.4 | 8.2 | 2.4 | 3.5 | 6.1 | 19.5 | 18.45 | −69.97 | ||

| 30 | Private residence | 2.4 | 5.6 | 26.0 | 10.9 | 5.9 | 5.1 | 20.1 | 18.46 | −69.96 |

Appendix B

Instrumental Detection Limits (DLs) for Elements Quantified by Energy-Dispersive X-Ray Fluorescence (EDXRF), Expressed in Parts Per Million (ppm).

Table A3.

Instrumental detection limits (DL) for the analyzed elements (units in ppm).

Table A3.

Instrumental detection limits (DL) for the analyzed elements (units in ppm).

| Element | DL Determined (ppm) |

|---|---|

| K | 109.7 |

| Ca | 159.4 |

| Ti | 13.0 |

| V | 3.3 |

| Cr | 1.7 |

| Mn | 3.8 |

| Fe | 12.7 |

| Ni | 0.9 |

| Cu | 5.4 |

| Zn | 5.4 |

| As | 0.0 |

| Br | 0.2 |

| Sr | 0.2 |

| Cd | 0.6 |

| Hg | 0.2 |

| Pb | 0.9 |

References

- Anderson, J.O.; Thundiyil, J.G.; Stolbach, A. Clearing the Air: A Review of the Effects of Particulate Matter Air Pollution on Human Health. J. Med. Toxicol. 2012, 8, 166–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. The World Health Report 2002: Reducing Risks, Promoting Healthy Life; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. WHO Global Air Quality Guidelines: Particulate Matter (PM2.5 and PM10), Ozone, Nitrogen Dioxide, Sulfur Dioxide and Carbon Monoxide; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Goossens, J.; Jonckheere, A.C.; Dupont, L.J.; Bullens, D.M.A. Air Pollution and the Airways: Lessons from a Century of Human Urbanization. Atmosphere 2021, 12, 898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anjum, M.S.; Ali, S.M.; Imad-Ud-Din, M.; Subhani, M.A.; Anwar, M.N.; Nizami, A.S.; Ashraf, U.; Khokhar, M.F. An Emerged Challenge of Air Pollution and Ever-Increasing Particulate Matter in Pakistan; A Critical Review. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 402, 123943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sicard, P.; Agathokleous, E.; Anenberg, S.C.; De Marco, A.; Paoletti, E.; Calatayud, V. Trends in urban air pollution over the last two decades: A global perspective. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 858, 160064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanda, M.; Dunea, D.; Iordache, S.; Predescu, L.; Predescu, M.; Pohoata, A.; Onutu, I. Recent Urban Issues Related to Particulate Matter in Ploiesti City, Romania. Atmosphere 2023, 14, 746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Chen, J.; Zhou, C.; Wang, S.; Li, M. The Impacts of Urban Form on PM2.5 Concentrations: A Regional Analysis of Cities in China from 2000 to 2015. Atmosphere 2022, 13, 963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, K.; Wang, Y.; Wu, G.; Fu, B.; Zhu, Y. Spatiotemporal Characteristics of Air Pollutants (PM10, PM2.5, SO2, NO2, O3, and CO) in the Inland Basin City of Chengdu, Southwest China. Atmosphere 2018, 9, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Integrated Science Assessment (ISA) for Particulate Matter (Final Report, December 2019); Final Report, Technical Report EPA/600/R-19/188; U.S. Environmental Protection Agency: Washington, DC, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, A.J.; Brauer, M.; Burnett, R.; Anderson, H.R.; Frostad, J.; Estep, K.; Balakrishnan, K.; Brunekreef, B.; Dandona, L.; Dandona, R.; et al. Estimates and 25-year trends of the global burden of disease attributable to ambient air pollution: An analysis of data from the Global Burden of Diseases Study 2015. Lancet 2017, 389, 1907–1918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murray, C.J.; Aravkin, A.Y.; Zheng, P.; Abbafati, C.; Abbas, K.M.; Abbasi-Kangevari, M.; Abd-Allah, F.; Abdelalim, A.; Abdollahi, M.; Abdollahpour, I.; et al. Global burden of 87 risk factors in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet 2020, 396, 1223–1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaishankar, M.; Tseten, T.; Anbalagan, N.; Mathew, B.B.; Beeregowda, K.N. Toxicity, mechanism and health effects of some heavy metals. Interdiscip. Toxicol. 2014, 7, 60–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO Regional Office for Europe. Review of Evidence on Health Aspects of Air Pollution—REVIHAAP; Technical Report; WHO Europe: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Silva, R.A.; West, J.J.; Lamarque, J.F.; Shindell, D.T.; Collins, W.J.; Faluvegi, G.; Folberth, G.A.; Horowitz, L.W.; Nagashima, T.; Naik, V.; et al. Future global mortality from changes in air pollution attributable to climate change. Nat. Clim. Change 2017, 7, 647–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asif, M.; Yousuf, S.; Donald, A.N.; Hassan, A.M.M.; Iqbal, A.; Bodlah, M.A.; Sharf, B.; Noshia, N. A review on particulate matter and heavy metal emissions; impacts on the environment, detection techniques and control strategies. MOJ Ecol. Environ. Sci. 2021, 7, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alharbi, H.A.; Rushdi, A.I.; Bazeyad, A.; Al-Mutlaq, K.F. Temporal Variations, Air Quality, Heavy Metal Concentrations, and Environmental and Health Impacts of Atmospheric PM2.5 and PM10 in Riyadh City, Saudi Arabia. Atmosphere 2024, 15, 1448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contini, D.; Cesari, D.; Donateo, A.; Chirizzi, D.; Belosi, F. Characterization of PM10 and PM2.5 and Their Metals Content in Different Typologies of Sites in South-Eastern Italy. Atmosphere 2014, 5, 435–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alwadei, M.; Srivastava, D.; Alam, M.S.; Shi, Z.; Bloss, W.J. Chemical characteristics and source apportionment of particulate matter (PM2.5) in Dammam, Saudi Arabia: Impact of dust storms. Atmos. Environ. X 2022, 14, 100164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Querol, X.; Alastuey, A.; Viana, M.; Rodriguez, S.; Artiñano, B.; Salvador, P.; Garcia do Santos, S.; Fernandez Patier, R.; Ruiz, C.; de la Rosa, J.; et al. Speciation and origin of PM10 and PM2.5 in Spain. J. Aerosol Sci. 2004, 35, 1151–1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buseck, P.R.; Adachi, K. Nanoparticles in the Atmosphere. Elements 2008, 4, 389–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, R.M.; Yin, J. Particulate matter in the atmosphere: Which particle properties are important for its effects on health? Sci. Total Environ. 2000, 249, 85–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Jing, J.; Tao, J.; Hsu, S.C.; Wang, G.; Cao, J.; Lee, C.S.L.; Zhu, L.; Chen, Z.; Zhao, Y.; et al. Chemical characterization and source apportionment of PM2.5 in Beijing: Seasonal perspective. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2013, 13, 7053–7074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pant, P.; Harrison, R.M. Estimation of the contribution of road traffic emissions to particulate matter concentrations from field measurements: A review. Atmos. Environ. 2013, 77, 78–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duffus, J.H. “Heavy metals”—A meaningless term. Chem. Int.-Newsmag. IUPAC 2001, 23, 163–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maret, W. Zinc Biochemistry: From a Single Zinc Enzyme to a Key Element of Life. Adv. Nutr. 2013, 4, 82–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tchounwou, P.B.; Yedjou, C.G.; Patlolla, A.K.; Sutton, D.J. Heavy Metal Toxicity and the Environment. In Molecular, Clinical and Environmental Toxicology: Volume 3: Environmental Toxicology; Springer: Basel, Switzerland, 2012; pp. 133–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pope, C.A., III; Dockery, D.W. Health Effects of Fine Particulate Air Pollution: Lines that Connect. J. Air Waste Manag. Assoc. 2006, 56, 709–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valko, M.; Morris, H.; Cronin, M.T.D. Metals, Toxicity and Oxidative Stress. Curr. Med. Chem. 2005, 12, 1161–1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goudarzi, G.; Shirmardi, M.; Naimabadi, A.; Ghadiri, A.; Sajedifar, J. Chemical and organic characteristics of PM2.5 particles and their in-vitro cytotoxic effects on lung cells: The Middle East dust storms in Ahvaz, Iran. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 655, 434–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galeano-Páez, C.; Brango, H.; Pastor-Sierra, K.; Coneo-Pretelt, A.; Arteaga-Arroyo, G.; Peñata-Taborda, A.; Espitia-Pérez, P.; Ricardo-Caldera, D.; Humanez-Álvarez, A.; Londoño-Velasco, E.; et al. Genotoxicity and Cytotoxicity Induced In Vitro by Airborne Particulate Matter (PM2.5) from an Open-Cast Coal Mining Area. Atmosphere 2024, 15, 1420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Ge, P.; Deng, M.; Liu, X.; Lu, Z.; Yan, Z.; Chen, M.; Wang, J. Toxicological responses of A549 and HCE-T cells exposed to fine particulate matter at the air–liquid interface. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2024, 31, 27375–27387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueiredo, D.; Vicente, E.D.; Vicente, A.; Gonçalves, C.; Lopes, I.; Alves, C.A.; Oliveira, H. Toxicological and Mutagenic Effects of Particulate Matter from Domestic Activities. Toxics 2023, 11, 505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, A.; Li, R.; Chen, G.; Chen, S. Impact of Respiratory Dust on Health: A Comparison Based on the Toxicity of PM2.5, Silica, and Nanosilica. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 7654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabata-Pendias, A. Trace Elements in Soils and Plants; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burger, J. Bioindicators: Types, Development, and Use in Ecological Assessment and Research. Environ. Bioindic. 2006, 1, 22–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riojas-Rodríguez, H.; Da Silva, A.S.; Texcalac-Sangrador, J.L.; Moreno-Banda, G.L. Air pollution management and control in Latin America and the Caribbean: Implications for climate change. Rev. Panam. Salud Pública 2016, 40, 150–159. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Q.Q.; Guo, Y.T.; Yang, J.Y.; Liang, C.S. Review on main sources and impacts of urban ultrafine particles: Traffic emissions, nucleation, and climate modulation. Atmos. Environ. X 2023, 19, 100221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espinal, G.; Nivar, S. Estudio de la contaminación ambiental al interior de las viviendas en tres barrios de la capital dominicana. Cienc. Y Soc. 2004, 29, 167–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caballero-González, C. Calidad del Aire e Infraestructura Verde. Estudio de Caso: Distrito Nacional. Master’s Thesis, Instituto Tecnológico de Santo Domingo (INTEC), Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Gómez Pérez, A.; Guillermo Manzanillo, L.A.; Vázquez Frías, J.; Quintana Pérez, C.E. Contaminación atmosférica en puntos seleccionados de la ciudad de Santo Domingo, República Dominicana. Cienc. Soc. 2014, 39, 533–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinuzzi, S.; Locke, D.H.; Ramos-González, O.; Sanchez, M.; Grove, J.M.; Muñoz-Erickson, T.A.; Arendt, W.J.; Bauer, G. Exploring the relationships between tree canopy cover and socioeconomic characteristics in tropical urban systems: The case of Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic. Urban For. Urban Green. 2021, 62, 127125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matos-Espinosa, C.; Delanoy, R.; Caballero-González, C.; Hernández-Garces, A.; Jauregui-Haza, U.; Bonilla-Duarte, S.; Martínez-Batlle, J.R. Assessment of PM10 and PM2.5 Concentrations in Santo Domingo: A Comparative Study Between 2019 and 2022. Atmosphere 2025, 16, 734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Airmetrics. MiniVol Portable Air Sampler Operation Manual; Airmetrics: Eugene, OR, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Airmetrics. MiniVol TAS Portable Air Sampler; Airmetrics: Eugene, OR, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Part 50—National Primary and Secondary Ambient Air Quality Standards U.S. Government Publishing Office. Available online: https://www.ecfr.gov/current/title-40/part-50 (accessed on 3 March 2025).

- Skyray Instrument Inc. RoHS4 Software, version 1.1.47_110524_R; Skyray Instrument Inc.: Kunshan, China, 2009.

- Skyray Instrument Inc. RoHS4 User Manual; Skyray Instrument Inc.: Kunshan, China, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- United States Environmental Protection Agency (USEPA). Method 6200: Field Portable X-ray Fluorescence Spectrometry for the Determination of Elemental Concentrations in Soil and Sediment. 2007. Available online: https://www.epa.gov/sites/default/files/2015-12/documents/6200.pdf (accessed on 3 March 2025).

- ISO/IEC 17025:2017; General Requirements for the Competence of Testing and Calibration Laboratories. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017.

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Wickham, H.; Averick, M.; Bryan, J.; Chang, W.; McGowan, L.D.; François, R.; Grolemund, G.; Hayes, A.; Henry, L.; Hester, J.; et al. Welcome to the tidyverse. J. Open Source Softw. 2019, 4, 1686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pebesma, E.J. Multivariable geostatistics in S: The gstat package. Comput. Geosci. 2004, 30, 683–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gräler, B.; Pebesma, E.; Heuvelink, G. Spatio-Temporal Interpolation using gstat. R J. 2016, 8, 204–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiemstra, P.; Pebesma, E.; Twenhöfel, C.; Heuvelink, G. Real-time automatic interpolation of ambient gamma dose rates from the Dutch Radioactivity Monitoring Network. Comput. Geosci. 2009, 35, 1711–1721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neuwirth, E. RColorBrewer: ColorBrewer Palettes; R Package Version 1.1-3; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, L. NADA: Nondetects and Data Analysis for Environmental Data; R Package Version 1.6-1.1; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Stacklies, W.; Redestig, H.; Scholz, M.; Walther, D.; Selbig, J. pcaMethods—A Bioconductor package providing PCA methods for incomplete data. Bioinformatics 2007, 23, 1164–1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoari, N.; Dubé, J.S. Toward improved analysis of concentration data: Embracing nondetects. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2018, 37, 643–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matheron, G. Principles of geostatistics. Econ. Geol. 1963, 58, 1246–1266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cressie, N. Geostatistics. Am. Stat. 1989, 43, 197–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isaaks, E.H.; Srivastava, R.M. Applied Geostatistics; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1989; Volume 561. [Google Scholar]

- Goovaerts, P. Geostatistics for Natural Resources Evaluation; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Pebesma, E.; Bivand, R. Spatial Data Science: With Applications in R; Chapman and Hall/CRC: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pebesma, E. Simple Features for R: Standardized Support for Spatial Vector Data. R J. 2018, 10, 439–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wickham, H. ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen, T.L. patchwork: The Composer of Plots; R Package Version 1.2.0; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Beckhoff, B.; Kanngießer, H.B.; Langhoff, N.; Wedell, R.; Wolff, H. (Eds.) Handbook of Practical X-Ray Fluorescence Analysis; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, S. Inorganic Mass Spectrometry: Principles and Applications; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Niu, J.; Rasmussen, P.E.; Wheeler, A.; Williams, R.; Chénier, M. Evaluation of airborne particulate matter and metals data in personal, indoor and outdoor environments using ED-XRF and ICP-MS and co-located duplicate samples. Atmos. Environ. 2010, 44, 235–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PerkinElmer, Inc. Sensitivity, Background, Noise, and Calibration in Atomic Spectroscopy: Effects on Accuracy and Detection Limits; White Paper; PerkinElmer, Inc.: Waltham, MA, USA, 2018; pp. 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Wold, H. Estimation of principal components and related models by iterative least squares. Multivar. Anal. 1966, 391–420. [Google Scholar]

- Wold, S.; Esbensen, K.; Geladi, P. Principal component analysis. Chemom. Intell. Lab. Syst. 1987, 2, 37–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henry, R.C.; Lewis, C.W.; Hopke, P.K.; Williamson, H.J. Review of receptor model fundamentals. Atmos. Environ. 1984, 18, 1507–1515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celo, V.; Yassine, M.M.; Dabek-Zlotorzynska, E. Insights into Elemental Composition and Sources of Fine and Coarse Particulate Matter in Dense Traffic Areas in Toronto and Vancouver, Canada. Toxics 2021, 9, 264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, H.; Ryu, J.S.; Ra, K. Characteristics of potentially toxic elements and multi-isotope signatures (Cu, Zn, Pb) in non-exhaust traffic emission sources. Environ. Pollut. 2022, 292, 118339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Ma, L.; He, X.; Au, W.C.; Miao, Y.; Wang, W.X.; Nah, T. Measurement report: Abundance and fractional solubilities of aerosol metals in urban Hong Kong—Insights into factors that control aerosol metal dissolution in an urban site in South China. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2023, 23, 1403–1419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasoazanany, E.O.; Andriamahenina, N.N.; Ravoson, H.N.; Andriambololona, R.; Randriamanivo, L.V.; Ramaherison, H.; Ahmed, H.; Harinoely, M. Air pollution studies in terms of PM2.5, PM2.5–10, PM10, lead and black carbon in urban areas of Antananarivo—Madagascar. arXiv 2012, arXiv:1204.1498. [Google Scholar]

- Laidlaw, M.A.; Filippelli, G.M. Resuspension of urban soils as a persistent source of lead poisoning in children: A review and new directions. Appl. Geochem. 2008, 23, 2021–2039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mielke, H.W.; Laidlaw, M.A.; Gonzales, C. Lead (Pb) legacy from vehicle traffic in eight California urbanized areas: Continuing influence of lead dust on children’s health. Sci. Total Environ. 2010, 408, 3965–3975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Resongles, E.; Dietze, V.; Green, D.C.; Harrison, R.M.; Ochoa-Gonzalez, R.; Tremper, A.H.; Weiss, D.J. Strong evidence for the continued contribution of lead deposited during the 20th century to the atmospheric environment in London of today. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2021, 118, e2102791118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Day, P.A.; Pattammattel, A.; Aronstein, P.; Leppert, V.J.; Forman, H.J. Iron Speciation in Respirable Particulate Matter and Implications for Human Health. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2022, 56, 7006–7016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Furutani, H.; Jung, J.; Miura, K.; Takami, A.; Kato, S.; Kajii, Y.; Uematsu, M. Single-particle chemical characterization and source apportionment of iron-containing atmospheric aerosols in Asian outflow. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2011, 116, D18204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spada, N.J.; Cheng, X.; White, W.H.; Hyslop, N.P. Decreasing Vanadium Footprint of Bunker Fuel Emissions. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2018, 52, 11528–11534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tao, L.; Fairley, D.; Kleeman, M.J.; Harley, R.A. Effects of Switching to Lower Sulfur Marine Fuel Oil on Air Quality in the San Francisco Bay Area. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2013, 47, 10171–10178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- González-Romero, A.; González-Flórez, C.; Panta, A.; Yus-Díez, J.; Reche, C.; Córdoba, P.; Moreno, N.; Alastuey, A.; Kandler, K.; Klose, M.; et al. Variability in sediment particle size, mineralogy, and Fe mode of occurrence across dust-source inland drainage basins: The case of the lower Drâa Valley, Morocco. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2023, 23, 15815–15834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morton-Bermea, O.; Hernández-Alvarez, E.; Almorín-Ávila, M.A.; Ordoñez-Godínez, S.; Bermendi-Orosco, L.; Retama, A. Historical trends of metals concentration in PM10 collected in the Mexico City metropolitan area between 2004 and 2014. Environ. Geochem. Health 2021, 43, 2781–2798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, L.F.; Schneider, I.L.; Artaxo, P.; Núñez-Blanco, Y.; Pinto, D.; Flores, É.M.M.; Gómez-Plata, L.; Ramírez, O.; Dotto, G.L. Particulate matter geochemistry of a highly industrialized region in the Caribbean: Basis for future toxicological studies. Geosci. Front. 2022, 13, 101115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Colla, N.S.; Botté, S.E.; Marcovecchio, J.E. Atmospheric particulate pollution in South American megacities. Environ. Rev. 2021, 29, 415–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, R.M.; Jones, A.M.; Lawrence, R.G. Major component composition of PM10 and PM2.5 from roadside and urban background sites. Atmos. Environ. 2004, 38, 4531–4538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karagulian, F.; Belis, C.A.; Dora, C.F.C.; Prüss-Ustün, A.M.; Bonjour, S.; Adair-Rohani, H.; Amann, M. Contributions to cities’ ambient particulate matter (PM): A systematic review of local source contributions at global level. Atmos. Environ. 2015, 120, 475–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, C.S.; Lu, C.C.; Shen, H.Z.; Li, T.C. Metallic characteristics of PM2.5 and PM2.5–10 for clustered Aeolian Dust Episodes occurred in an extensive fluvial basin during rainy season. J. Air Waste Manag. Assoc. 2018, 68, 1085–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, H.; Liu, G.; Zhang, H.; Hu, R.; Wang, X. Similarities and differences in PM10 and PM2.5 concentrations, chemical compositions and sources in Hefei City, China. Chemosphere 2019, 220, 760–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manchanda, C.; Kumar, M.; Singh, V.; Hazarika, N.; Faisal, M.; Lalchandani, V.; Shukla, A.; Dave, J.; Rastogi, N.; Tripathi, S.N. Chemical speciation and source apportionment of ambient PM2.5 in New Delhi before, during, and after the Diwali fireworks. Atmos. Pollut. Res. 2022, 13, 101428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varrica, D.; Alaimo, M.G. Determination of water-soluble trace elements in the PM10 and PM2.5 of Palermo Town (Italy). Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McComb, J.Q.; Rogers, C.; Han, F.X.; Tchounwou, P.B. Rapid Screening of Heavy Metals and Trace Elements in Environmental Samples Using Portable X-Ray Fluorescence Spectrometer, A Comparative Study. Water Air Soil Pollut. 2014, 225, 2169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, J.; Ge, Y.; Li, H.; Yang, C.; Liu, C.; Meng, X.; Wang, W.; Niu, C.; Kan, L.; Schikowski, T.; et al. Application of land use regression to assess exposure and identify potential sources in PM2.5, BC, NO2 concentrations. Atmos. Environ. 2020, 223, 117267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Q.; Cheng, N.; Li, S.; Dong, M.; Wang, X.; Ge, L.; Guo, T.; Li, W.; Gao, X. An Amended Chemical Mass Balance Model for Source Apportionment of PM2.5 in Typical Chinese Eastern Coastal Cities. CLEAN—Soil Air Water 2019, 47, 1800115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).